Abstract

Questioning motherhood as a social mandate has been one of the main objectives of feminism. Motherhood has traditionally been linked to the idea of femininity and the reproductive function, which has led to women being thought of as “compulsory mothers”. However, this idea is currently changing, despite the fact that judgment is exercised on non-mothers. This research is part of a cross-sectional descriptive study, whose objective is to analyze the barriers and incentives to childbearing in the female population. A questionnaire was designed and administered to a representative sample of 318 women who were selected for our analysis, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. Results: Economic motives correlate positively with other variables, as well as work motives, the couple’s decision to not want to have children, and not having a stable partner, which suggests that these women have different motives for choosing not to have children. The main conclusions are that social and family pressures appear to have a limited impact on the decision not to have children, suggesting a change in social norms and expectations about the role of women in society, as women continue to gain autonomy and control over their reproductive decisions.

1. Introduction

Motherhood has been a central theme in feminist theory since its origin; an example of this is the following phrase: “the most important thing in a woman’s life is her status as a mother. Expressions such as ‘infertile’ or ‘childless’ have been used to annul any other possible identity” (Rich, 2019, 56) [1]. The issue of motherhood has been explored from multiple perspectives, which have analyzed its significance and the pressures imposed by the patriarchal society, where men have historically held power and women have been relegated to a subordinate role. Feminist authors have insisted on the need for women to be able to make their own decisions regarding their own body, the area of sexuality, and motherhood. Feminism in general, particularly liberal and radical feminism, has fought for the possibility of being a mother to be a free choice and not an imposition, and has also demanded access to methods such as assisted reproduction or the right to be single mothers [2].

To contextualize our study, it is important to clarify that it is focused on the female population of Andalusia (Spain), whose national birth rate has been consistently declining. Currently, the birth rate stands at 6.61 (births per thousand inhabitants) [3], which translates to 1.12 children per woman [4]. In our country, we are witnessing a decline in birth rates and an increase in the average age of motherhood (currently 32.6 years) [5], meaning that women are having fewer children and having them at older ages. It is precisely in this context that the study of the reasons why women choose not to have children becomes relevant, as this is a growing reality. The negative vegetative growth rate indicates that more people are dying than being born.

In this regard, and concerning public policies related to motherhood, it is important to highlight that, within the Spanish context, beyond existing measures aimed at promoting work–life balance—such as maternity and paternity leave, or reduced working hours, which are currently being revised and improved [6,7]—the legislation also acknowledges the diversity of family structures, including the recognition of single-parent families. In this regard, Law 14/2006 of 26 May [8] offers and guarantees women access to assisted reproduction techniques free of charge, regardless of their marital status or sexual orientation. Within the Andalusian context, it is important to highlight the existence of specific tax deductions available to families with dependent minors, which vary according to the age of the child. Additional deductions are also provided for single-parent households and large families [9]. Moreover, a range of support measures are offered, including financial assistance for young mothers, reduced working hours for childcare, and aid for multiple births, among others [10].

Continuing with the theoretical review, feminism has always tried to raise the voice of women, which is well defined by Kate Millet [11] with her motto “the personal is political”, referring to the need to make public matters that have always been considered part of the domestic sphere. This motto encapsulates a fundamental feminist principle: personal experiences, particularly those lived by women in the private sphere—such as domestic violence, the unequal distribution of care work, or restrictions on bodily autonomy—are inherently political and must be addressed collectively. Historically, the relegation of women to the private domain has silenced their voices in the public arena. By asserting that the personal is political, Millet underscores the need to recognize these individual experiences as systemic issues that demand visibility, social recognition, and legislative intervention. In this way, feminism repositions the private sphere as a site of political significance, reinforcing its commitment to making women’s realities central to public discourse and policy-making [11].

The questioning of motherhood as a social mandate has been one of the main objectives of feminism. Motherhood has traditionally been associated with the idea of femininity and the reproductive function, which has led to women being thought of as “potential mothers” [12]. The feminist criticism has insisted that motherhood is not inherent to the female condition, and must be an option, not an obligation. In this sense, Simone de Beauvoir challenged the notion that motherhood is a natural destiny for women, arguing that this imposition is a type of slavery that has contributed to the oppression of women [3]. More specifically, she compares other animal species with the human species, underlining that it is society that needs births and places the burden on women, as human females are not subjected to the heat cycle which occurs in other animal species. De Beauvoir affirms that the relationship between motherhood and individual life is regulated in animals by the heat cycle and seasons; in women, it is undefined; only society can decide upon it, depending on whether humanity requires more or less births. Thus individual “possibilities” depend on the economic and social situation [12].

The concept of motherhood has been deeply influenced by social and patriarchal constructs that have relegated women to domestic roles. Adrienne Rich, in her work “Of woman born”, clearly distinguished between the biological ability to be a mother and the institution of motherhood, which has historically controlled women [1]. Rich pointed out that motherhood as an institution has been used to subjugate women, limiting their personal development and their participation in the public sphere: “motherhood as institution has ghettoized and degraded female potentialities” (Rich, 2019, 57) [1]. This has resulted in many women feeling that their identity and value as individuals are dependent on their ability to be mothers [1], given that, as Ana María Fernández suggests, this is due to the symbolism of motherhood and its practices, as feminism has been constructed throughout history. That is, there is a historical feedback loop between the construction of the feminine ideal and the motherhood ideal, giving way to it becoming an imposition to all women [13].

In this context, motherhood has been conceived as a “social mandate” that is imposed on women from multiple fronts: cultural, legal, and psychological. The patriarchal society has insisted that women must feel fulfilled through motherhood, which has created a significant pressure on those who opt not to have children. As Elisabeth Badinter explains, women who decide not to be mothers face considerable social stigmatization, being viewed as egotistical or abnormal. Badinter points out that as opposed to men, whose identity is not necessarily linked to paternity, women who do not have children are constantly questioned, and demands are made to justify their decision [14,15].

Despite the advances on women’s rights, such as sexual freedom or reproductive control [9,16,17], social conditioning still plays a decisive role in reproductive rights. Motherhood, or its absence, is still a central axis in the construction of the gender identity in many modern societies, and advances are needed on the conception of motherhood by desire or choice in order to overcome the idea that “being a mother is the biological destiny of women” [18]. The social pressure with regard to maternity can generate internal conflicts in women, especially when the expectations from the environment, with respect to them, do not coincide with their personal desires. As for social conditioning, the position of Orna Donath [19] is interesting, as it considers that society assumes that women who have resorted to abortion will feel regret, since the desire to be a mother is intrinsic to them and it is in their nature, without understanding that this feeling can, however, be produced by having social morality so internalized that they can even feel like criminals for having an abortion, leading to internal conflicts. She points out that the feelings that arise from social stigmatization after an abortion—among other similar experiences—are often overlooked or dismissed [19].

The pressure to conform to social expectations on motherhood can create internal conflicts in women, especially when these expectations do not coincide with their personal desires. In this sense, the feminist criticism has pointed to the importance of recognizing the diversity of women’s experiences and choices, and of creating a space in which they are able to make reproductive decisions free of social pressures [2,20]. In accordance with prevailing societal expectations surrounding motherhood, it is essential to distinguish between motherhood as a social institution and the lived experience of mothering, as emphasized by O’Reilly in her articulation of matricentric feminism [21]. This perspective calls for the inclusion of mothers’ own voices in academic discourse, the increased presence of academic mothers, and the study of motherhood from women’s lived experiences. Such an approach is crucial to fully understanding that being a mother, much like being racialized or identifying as a lesbian, can entail a form of “double oppression”. She points out that the subject of motherhood must be dealt with from intersectionality, just as with sexual orientation, social class, or ethnicity. In this way, the author points to the existence of specific problems that mothers must face, since aside from being women, they are mothers, which implies specific characteristics in their position in the world and in gender inequality. In fact, for them, the concept of maternity from a patriarchal perspective of “motherhood as an institution” entails a denial of motherhood, and therefore, its “forgetting or denial” within feminism, thus preventing it from becoming an object of the feminist struggle and having an impact on the empowerment of women mothers [21].

The debate on the decisions of women has gained relevance in the last few decades with the increase in the number of women who decide not to have children. For some feminists, this decision represents a type of resistance against the patriarchal expectations that insist that women must comply with their “biological destiny”. However, the decision to not become a mother is not always simple, as it implies facing a set of social, family, and, in many cases, couple-related pressures. Sanchez Teruel points out that in many couple relationships, women succumb to the pressure of having children, even when they do not desire it. This can generate profound and long-lasting conflicts, as well as feelings of guilt and resentment towards the partner [19,22,23].

Feminist criticism has also questioned the value given to motherhood in relation with paid work and personal development. Silva Federici has argued that reproductive work, which includes motherhood, has historically been devalued and unpaid, which has contributed to job insecurity in women. Federici sustains that the capitalist system has benefited from the exploitation of the unpaid work of women in the home, which has limited their opportunities to participate in the labor market and the public sphere [2].

In this context, motherhood is presented as a challenge for women who wish to develop a professional career or to have an identity that is independent from their role as mothers. The social pressure for women to assume the main responsibility of childcare and the home is still strong, which reinforces gender inequalities both at home and in the workplace. As Rich points out, motherhood as an institution has served to maintain women in a subordinate position, relegating them to the private sphere and excluding them from their full participation in public life [1].

However, feminism has not only questioned the imposition of motherhood, but also the conditions on which many women exert it. Feminists have advocated for the creation of public policies that support mothers, such as access to childcare facilities, maternity and paternity leave, and equality at work. These demands seek to alleviate the disproportionate loads that women face in the care of their children and to promote a more equal distribution of family responsibilities [14].

One of the most recent studies conducted on the decision not to have children, carried out in the United States [24], revealed that 57% of adults under 50 consider it “unlikely” that they will have children at any point. Some of the reasons they provide for making this decision include not wanting to have children, wanting to focus on other things, concerns about the state of the world, and not having found the ideal partner, among others. In terms of gender differences, women more frequently cite having had negative experiences during their childhood with their own families, and also simply not wanting children. Therefore, we are faced with the trend of voluntary childlessness, where individuals choose not to have children voluntarily, a phenomenon that remains understudied in Spain. For our country, we can refer to data from the Spanish Survey on Fertility and Values [25], where only 5% of the surveyed women identified with this trend. Among them, women who are not married stand out (81%); however, 42% of the total still have a partner, though they are not married, and this includes those whose partner does not wish to have descendants (51%). Later, some of these variables will be analyzed, such as having or not having a partner and the partner’s desire for children, which are key factors in our study.

In this regard, the present study seeks to delve deeper into the issue of voluntary childlessness, as it remains insufficiently explored in Spain. Understanding the motivations behind women’s decisions not to become mothers is therefore essential. Within the existing literature on the subject, authors such as Helen Peterson and Kristina Engwall [26] have conducted qualitative studies aiming to identify the reasons why some women choose not to have children. Among the motivations reported are fear of motherhood—particularly of childbirth—and the absence of maternal instinct, among others. In a separate qualitative study conducted in Sweden, Peterson [27] found that childless women often define non-motherhood in terms of liberation. The author also examined other factors related to childlessness in her national context, such as the extent to which gender inequality may or may not influence reproductive decisions [28]. Overall, Peterson’s work recalls that of Betty Friedan [29], who focused her analysis on the dissatisfaction experienced by housewives and challenged the notion that motherhood is the only path to female fulfillment. Furthermore, in connection with the potential social pressures experienced by women who are not mothers—which will be further addressed later in this article—Gayle Letherby and Catherine Williams [30] explore the ways in which these women may be excluded from certain social spaces or feel discomfort in conversations where motherhood is portrayed as central or essential.

Given the above, the main objective of the present study is to assess social, economic, personal, biological, and sociodemographic factors that women who consider themselves feminists think can influence the decision to be a mother or not.

The hypotheses derived are as follows:

Hypothesis 1:

If women perceive social pressure from family, partners, friends, the workplace, acquaintances, and society at large—shaped by traditional gender norms that associate women’s fulfillment with motherhood—then this will be a significant factor influencing their decision to become mothers or not. This aligns with feminist theory, which critiques motherhood as a social mandate.

Hypothesis 2:

If age and employment status are factors deeply affected by structural gender inequalities that impact women’s economic autonomy, then these factors will be considered important by both mothers and non-mothers in their decision to become a mother. According to feminist theory, the full exercise of reproductive rights requires equitable material conditions.

Hypothesis 3:

If personal factors related to one’s partner—such as having a stable relationship, the partner’s desire (or lack thereof) to have children, and marital status—influence a woman’s decision, then these factors will play a decisive role in the decision to become a mother or not. From a feminist perspective, the influence of these factors is interpreted within a broader context in which affective and/or conjugal relationships are also shaped by power dynamics that can constrain women’s reproductive autonomy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

The present study is framed within a cross-sectional descriptive study, whose objective is to analyze the reasons that lead feminist women to decide not to be mothers or not to have more children.

The database comes from the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE), specifically a 2019 poll on the barriers and incentives to childbearing [31]. In that study, a total of 9,636,200 women (mean age 42.2 years; SD = 11.69) were polled at the national level, of which 3,396,213 did not have children, and 6,239,988 were mothers. Our research was centered on the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, where 1,784,724 women were polled (604,744 without children, and 1,179,980 with children). Working with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, a representative sample of 318 women was determined, who were selected for our analysis. The cross-sectional design of the present study allowed us to determine the characteristics of the sample at a single point in time, providing a detailed analysis of the factors that have an influence on the decision to be a mother or not, considering sociodemographic and personal variables.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee from the University of Almeria (Ref.: UALBIO2022/020), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [32], which establishes ethical principles for research on human beings, guaranteeing the respect and protection of the participants. Likewise, the study adhered to the guidelines from the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) [33], and to current regulations on data protection.

All the participants signed their informed consent at the start of the questionnaire, which clearly explained the objectives of the study, as well as their right to abandon the research at any point in time without it affecting their situation. This practice ensured that the participants were fully informed about their participation and able to freely decide on their involvement in the study, in compliance with the ethical standards of research.

2.2. Participants

The analysis population was obtained through stratified sampling. First, according to a screening question about whether one considers oneself a feminist or not; second, by dividing the sample of interest into mothers and non-mothers; and third, by separating the non-mothers into three groups: (1) those that do not want to, (2) those that cannot, and (3) those who are not mothers and have expressed a clear intention not to have (or adopt) children in the future, considering that motherhood is not part of their life project. This group was identified based on responses to the question: “Do you see yourself having children in the future?”, using the answer: “No, I do not wish to become a mother” as the inclusion criterion.

The inclusion criteria in the program were as follows: women residing in Andalusia; aged between 18 and 50 years old; with or without children; self-considered feminists; and expressing willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: women with medical conditions that impeded motherhood; those not residing in Andalusia; and being younger than 18 years old or older than 50 years old.

The original sample consisted of 1500 women who completed the initial screening survey. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and based on their availability and willingness to participate in the in-depth phase of the study, a final sample of 318 participants was selected.

This final sample was composed of the following: (1) 172 mothers (44.8%) and (2) 146 non-mothers who explicitly stated that they did not want to have children (38%). Participants from the other two identified non-mother subgroups—those who could not have children and those who already had children but did not wish to have more—were not included in the final sample for the analysis, due to insufficient representation or lack of consent to continue in the study. Therefore, the three theoretical subgroups were used to classify the broader population during initial screening, but only two (mothers and voluntary non-mothers) were represented in the final analytic sample.

All women included in the final analysis were residents in Andalusia and between 19 and 50 years old (M = 42; SD = 12.74).

Table 1 shows the comparative sociodemographic variables between women with children (“Children”) and without children (“No children”). The women with children had a significantly higher mean age (M = 47.49, SD = 10.71) than the women without children (M = 36.91, SD = 12.60). As for the marital status, the women with children also tended to have a more stable marital status as compared to non-mothers. In terms of level of education, the non-mothers had a slightly higher level as compared to the mothers. As for the employment and economic situation, no significant differences were observed.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics segmented by cases (mothers and non-mothers).

2.3. Instrument

To conduct the present study, the survey method was utilized through the use of the Limesurvey platform [34] in an online format. This selection was based on the difficulty of finding women who were not mothers and who were willing to share their experiences about a very personal matter [35]. The administration of the online questionnaire offered the participants a greater feeling of intimacy to address such an important subject as motherhood or non-motherhood.

The survey was composed of two main blocks. The first block focused on sociodemographic aspects, allowing for the establishment of respondents’ profiles. This section included variables such as age, marital status, whether the respondent was a mother (yes/no), their partner’s sex, level of education, employment status, and economic situation. The second block included questions extracted from the INE survey published in 2019, which analyzed the motives of women who did not have the intention to have children in the next 3 years [31]: (1) Do not have a partner, partner is not adequate, or partner does not want to; (2) limitations to having biological children in a natural way (tubal ligation, vasectomy, menopause, hysterectomy); (3) economic motives; and (4) work motives or conciliation between family and work life. However, in the present study, these items were adapted by modifying the verb tenses to express these reasons as general ideas or perceptions, rather than as personal circumstances. The aim was not to explore participants’ individual reproductive decisions, but to examine their perceptions and thoughts regarding the relevance of these factors in the general decision to become a mother. Thus, the questions were phrased in a way that asked participants to what extent they believed each factor influenced the decision to have children, regardless of their own maternal status.

In addition, new questions developed by the research team were included, based on bibliographical references and the work conducted in four previous focus groups (two with mothers and two with non-mothers) that provided the basis for formulating the hypotheses: In general terms, speaking of society as a whole, do you consider that there is social pressure for women to have offspring?: (1) a lot, (2) quite a lot, (3) a little, and (4) none; how much pressure do you think is faced from the following groups in terms of the decision to become a mother or not?: (1) family, (2) partner, (3) friends, (4) work environment, (5) acquaintances, and (6) population in general.

It is important to clarify that this second block of questions was answered by both mothers and non-mothers, as the objective was to compare how women with different maternal statuses perceived the same social and structural factors related to the decision to become a mother.

Regarding the focus groups, it should be noted that the women selected to participate were recruited through the snowball sampling technique. Initial participants referred other potential participants who met the criteria required to be included in the study. Once these potential participants expressed their willingness to take part, the initial participants provided their contact information so that we could reach out to them and arrange the focus group sessions. The focus group sessions were conducted online via a video conferencing application, and a voice recorder was used to facilitate the subsequent transcription of the discussions. A total of four focus groups were conducted, each consisting of four women. Two of the groups were composed of mothers and the other two of voluntary non-mothers, all aged between 30 and 50 years. As in the case of the survey, all participants signed an informed consent form prior to their involvement. It is important to note that these focus groups were part of the same research project presented in this article. Regarding the questions used, those developed by the National Statistics Institute (INE) [31] served as the basis; however, they were reformulated as open-ended questions for this phase. This format encouraged discussion among the participants and, through these interactions, some of the new questions later included in the survey were developed. All the output variables related to the motives for becoming a mother or not used a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4 (1 = not important; 4 = very important). The decision to employ a four-point Likert scale was made because, by not including a neutral option, respondents were compelled to adopt a more defined position [36]. The omission of a midpoint category may have reduced the tendency of participants to select the central option without a genuine preference, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the data [37]. Furthermore, scales with fewer response options are generally easier for respondents to understand and complete, which can increase response rates and reduce the time required to complete the questionnaire [38].

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated from the output variables (mean and standard deviation), and an analysis of independent samples (Student’s t test) and a correlation test were performed between them. The normality tests allowed us to perform parametric analyses.

To assess the factors most highlighted by the respondent regarding the probability of not being a mother (dependent variable), an initial stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to select the optimum subset of predictive variables that better explained or predicted the dependent variable, to identify which variables truly contributed to the model in a significant manner, and to avoid including those that did not provide valuable information. The dependent variable was dichotomous, coded as (0) for being a mother and (1) for not being a mother. The independent variables included a set of factors related to social pressure (family, partner, friends, work environment, acquaintances, social sphere), as well as economic (economic motives and work situation—employed/unemployed) and personal (having a stable partner, if the partner wants/does not want to have children, and marital status) factors, biological motives, and sociodemographic variables (age and level of education) that could have an influence on the decision to become a mother.

Following this, a binary logistic regression analysis was carried out with the independent variables selected in the stepwise regression model (age, marital status, if the partner wants to/does not want to have children, having a stable partner, and biological motives). The logistic regression analysis allowed for an estimation of the odds ratio of not being a mother as a function of each of these factors, controlling for the other variables included in the model. The coefficients of the independent variables were interpreted in terms of the probability of not being a mother (Y = 1), as compared to being a mother (Y = 0).

Multicollinearity was analyzed between the predictive variables through the calculation of the index of tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF). The interactions between some of the key factors were also tested to assess if the impact of a single factor, such as employment, varied as a function of marital status or age.

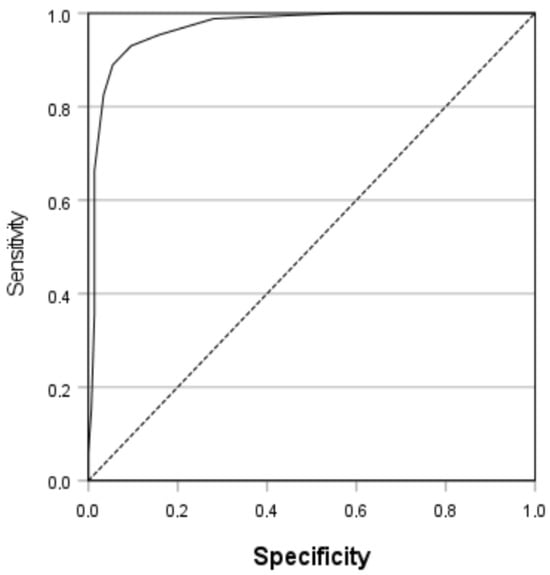

The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed through the Pseudo R2 by McFadden and an ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve, with the calculation of the area under the curve (AUC) and Kohen’s Kappa [39] to measure the predictive capacity of the model. The p-values associated with the coefficients were calculated to determine the statistical significance of each predictive variable, considering a level of significance of p < 0.05.

Lastly, additional residual fitting tests were performed to verify the robustness of the model and the influence of atypical values. The results from this analysis allowed for the identification of factors that significantly contributed to the decision of motherhood in the population studied.

3. Results

Table 2 shows the significant differences between women with children and women without children in the key variables, with all the comparisons that obtained p-values lower than 0.001. With respect to the economic and work motives, women with children obtained higher scores (M = 3.12 and 3.16, respectively) than women without children (M = 2.08 and 2.11), which suggests that these factors had a weaker influence on women who were already mothers. In contrast, the women without children reported more pressure in all the social and family dimensions analyzed. For example, family pressure and social pressure were significantly higher in women without children, with means of 1.24 and 1.47, as compared to 1.05 and 1.09 for women with children.

Table 2.

Differences between women with children and women without children in the key variables.

The asymmetries and kurtosis of the women without children showed more extreme distributions, especially in the variable pressure from one’s partner (asymmetry of 4.288, and kurtosis of 20.078, which suggests that these women experienced these pressures in a more intense and variable manner).

Table 3 shows that the different variables analyzed are correlated. The economic motives were positively correlated with other variables, such as work motives (0.88; p < 0.001), the decision of the couple to not want children (0.53; p < 0.001), and not having a stable partner (0.53, p < 0.001), which suggests that these women had different motives when opting for non-motherhood. On the other hand, the economic and work motives had negative correlations with social (−0.44; p < 0.001 and −0.44; p < 0.001, respectively), family (−0.35; p < 0.001 and −0.35; p < 0.001, respectively), and work pressures (−0.26; p < 0.001 and −0.26; p < 0.001, respectively), which indicates that the women who prioritized these motives felt less social pressure to have children.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between variables of non-mothers.

Family and social pressures were more interrelated between themselves, but they did not seem to have a significant influence on the decision to not be a mother, which could indicate a change in the perception of motherhood in modern society. These results suggest that the decision to not have children is becoming increasingly associated with personal and professional motives, while social pressures must be decreasing in relevance in this context.

The stepwise regression analysis provided us with a model composed of the variables of age, marital status, if the partner wants/does not want children, having a stable partner, and biological motives. The data provided demonstrated that the test was not significant, and the test fit well with the data (Hosmer and Lemeshow test [40]: X2 = 3.809; gl = 8; sig = 0.874).

The regression analysis with the use of the variables provided by the stepwise analysis confirmed that the model presented was significant with respect to the variable observed (Omnibus test: X2 = 332.573; gl = 8; sig < 0.001). The results showed that 64.9% of the variability of not being a mother was explained by the five variables present in the model.

As shown in Table 4, in order of significance, the following are observed:

Table 4.

Variables in the equation. Binary regression model.

Table 5.

Area under the curve. Regression model obtained.

Figure 1.

ROC curve. Regression model obtained.

- Marital status (single): X2 = 34.163 (gl = 4); p = <0.00. Considering the effect of age, the decision of the couple to not become parents, not having a stable partner, and biological motives, being single is associated with non-motherhood.

- Not having a stable partner: X2 = 21.466 (gl = 1); p = 0.001. Considering the effect of age, being single, the decision of the couple to not become parents, and biological motives, not having a stable partner is associated with non-motherhood.

- Decision of the couple: X2 = 16.148 (gl = 1); p < 0.001. Considering the effect of age, being single, not having a stable partner, and biological motives, the decision of the couple to not become parents is associated with non-motherhood.

- Biological motives: X2 = 9.865 (gl = 1); p = 0.002. Considering the effect of age, being single, the decision of the couple to not become parents, and not having a stable partner, the biological motives are associated with non-motherhood.

- Age: X2 = 5.687 (gl = 1); p = 0.017. Considering the effect of being single, the decision of the couple to not become parents, not having a stable partner, and biological motives, being younger (closer to 18 years old) is associated with non-motherhood.

The OR (odds ratio) estimation shows that women who indicate, as an important factor, that their partner does not want to have children have a 0.372 greater probability of not being a mother; not having a stable partner has a strength of 0.276 in the decision to not be a mother; and the biological motives have a strength of association of 0.492.

4. Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to assess social, economic, personal, biological, and sociodemographic factors that women who consider themselves feminists think can influence the decision to be a mother or not.

This study did not aim to directly measure or predict the definitive decision to never become a mother, as such a decision is complex, evolving, and not always explicitly declared. Rather, the objective was to explore how both mothers and non-mothers perceive and evaluate the social, economic, and personal factors that influence the decision not to have (or to stop having) children. The survey items—some adapted from the INE questionnaire [31] and others developed specifically for this research—were designed to capture general perceptions and discourses surrounding motherhood, rather than concrete life plans or future reproductive trajectories. In this sense, the comparison between women who are currently mothers and those who are not allowed us to reflect on how maternal status shapes ideas and values related to the possibility or rejection of motherhood. The focus, therefore, was on perceived influences rather than biographical decisions, which provided a broader understanding of the cultural and structural dimensions that frame reproductive intentions today.

The selection of the sample of women who consider themselves feminists was not random, but deliberate, because, as stated in the Introduction, feminism has studied maternity from different perspectives, trying to demystify it and bringing forward the difficulties, limitations, prejudices, sacrifices, etc., entailed by choosing motherhood. On the other hand, it recognizes that the mature option of not becoming a mother, which has recently become widespread, also brings with it a series of judgements about women who choose this path. The above, together with the struggle for women’s freedom of choice carried out by feminists, makes it so that choosing women who consider themselves to be feminists for our sample grants it with a certain richness in the perception of the participants.

One of the most important findings from this analysis was the high predictive capacity of our model, which explained 88% of the variability in the decision to not have children. This result underlines the importance of the variables included in the model (age, marital status, couple’s decision, stability in the relationship, and biological motives), and reinforces the idea that non-motherhood is influenced by a complex combination of personal and social factors (thus supporting what was proposed in H1 and H2).

The results also suggest that women who decide not to have children do not do so for a single reason, but the interaction of multiple factors that include personal relations, their professional priorities, and their perception of social expectations. In this sense, non-motherhood can be seen as an informed and deliberate decision that reflects the changes in social norms and gender expectations [41].

It was verified that if a woman considered herself a feminist, she was aware of the possible prejudice that she may face due to this, and had made the decision to become a mother (or not) not only based on biological and cultural factors imposed upon her, but also taking into account socioeconomic, individual, and personal satisfaction factors. In fact, for non-motherhood to become a conceivable option for women, feminism has been essential. Without it, the possibility of choosing not to have children would not have been acknowledged. Motherhood has long been regarded as the norm, as something “natural,” and has often been imposed. Even the capacity to give life has been framed as the only privilege women possess simply by virtue of being women.

4.1. Partner

The results show that being single is strongly associated with non-motherhood (X2 = 34.163, p < 0.001). This finding coincides with studies that suggest that single women, as they are not associated with relationships with stable partners, face less pressure to have children, and have more freedom when making reproductive decisions without the influence of a partner [42]. In fact, the lack of a stable partner is also significantly associated with non-motherhood (X2 = 21.466, p = 0.001), which reinforces the notion that stability in a relationship is a crucial factor for reproductive decisions [43].

In addition, we must recall that Spanish law [19] offers women the possibility of accessing assisted reproduction methods free of charge, independently of their marital status or sexual orientation, which means that not having a partner is not a limiting factor when making the decision to not become a mother, as these women could opt for assisted reproduction if they truly desire to become mothers, but instead, they do not. The same is observed with heterosexual women, who decide not to become mothers independently of the possibility of accessing these types of resources.

Likewise, recent studies have pointed out that single women and women without a stable partner can opt for other life objectives, such as personal or professional development, instead of prioritizing motherhood [41]. This could also be related to a change in the social perception of women without children, who no longer face the same stigma as in the past, as it is becoming common for women to decide not to be mothers for personal and professional motives [44].

The couple’s decision to not have children is another factor that has an influence on non-motherhood (X2 = 16.148, p < 0.001). Women whose partner does not want children are significantly more prone to not become mothers, which highlights the role of negotiation within a couple in the making of productive decisions. Previous studies have indicated that couples very often make joint decisions about having children, and when one of the members in a relationship decides not to procreate, the other tends to respect that decision [42,43].

In fact, with respect to consensus in a couple, we must stop to think about the importance of the topic of descendants for a couple, and due to this, it is not strange for this topic to be discussed even before a relationship becomes formal. That is, we find feminist women whose position with respect to maternity is forceful, thoughtful, and almost always immovable, so that aside from the existence of negotiation within a couple and reaching an agreement being important, we cannot discard the idea that in many cases, couples stabilize precisely because both members agree on such an important topic as descendants. That is, not only does the fact that the couple do not want children significantly correlate with the woman ultimately not becoming a mother, but women who do not want children are more likely to choose a partner who does not want children. Furthermore, these types of couples normally do not have the historical concept that children are what lead to a full and happy marriage, but prioritize maintaining a good relationship with their partner without the need for descendants [45,46].

This finding is especially relevant in the context of modern relationships, where women have a greater power of decision and autonomy in their personal relationships, which could explain why women without children do not have to face social or family pressure to procreate. As traditional gender expectations weaken, women feel more able to make decisions that do not align with imposed social norms [47].

4.2. Biological Desire

The biological motives are also significantly associated with non-motherhood (X2 = 9.865, p = 0.002). Women who report not feeling a “biological need” to become mothers are more prone to decide not to have children, which is coherent with studies that suggest that many women do not perceive motherhood as a biological obligation, but a personal choice [18]. This finding supports the idea that voluntary non-motherhood is an option that is becoming increasingly more common among women who prefer to focus on other aspects of their lives, such as a professional career, personal growth, or the search for other forms of personal realization [48].

In fact, according to diverse studies, there is a higher probability of having a higher income among women who do not have children, and these women also tend to have a higher level of education with respect to the mean [49,50]. Without a doubt, there is a direct correlation between these two aspects, because naturally, the higher the level of education, the more probabilities women have to access a job with higher pay. This is the reason why, with respect to the biological desire towards motherhood, it must be taken into account that the incorporation of women into the world of education and work makes them consider a life beyond child-rearing, reinforcing personal fulfillment not only from the perspective of motherhood, but also other aspects of their lives.

Therefore, it is important to have in mind that the decision to not become a mother is not determined by the lack of a partner, or the partner agreeing with the decision, but rather appears to be more related to the personal aspirations of the women surveyed.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that on some occasions, the wish not to be a mother is related to women who “do not like children”. In this context, it is interesting to stress that although this may occur [50,51], it has also been found that some women do like children, and have nephews, cousins, etc., who fulfill their need to have contact with children. Furthermore, we must not consider being a mother the same as playing the role of a mother, as there are grandmothers, aunts, and cousins who take care of children, and due to different circumstances, become their role models, without being their mothers. In fact, the ability to give birth is not always synonymous to being a mother, i.e., cases of abandonment or child abuse, so it is necessary to separate the biological ability of women to create life from their ability to take care of children or be a “good mother”; to separate motherhood as a social institution and motherhood as a personal experience [52]. On the other hand, as noted by the women who participated in the discussion groups, it may be the case that experiencing a childhood where one had the obligation of taking care of small children may lead to not wanting this responsibility once maturity has been reached, due to having experienced a forced premature understanding of what it means to “mother”. That is, the desire to not want to become a mother is not directly related to having an affinity towards children, but also with not having this biological desire (which is taken for granted because of being a woman); nor is having a child something that every woman can do because it is presumed that she will be a good mother, even knowing that giving birth is not necessary for being a good mother.

4.3. Age

As for age, the analysis shows that younger women are more prone to not have children (X2 = 5.687, p = 0.017), which could reflect a tendency to postpone motherhood until they are older, or in some cases, to not have children at all. Recent studies have documented a generalized postponement of motherhood, promoted by the search for economic and work stability, as well as the desire to reach personal goals before starting a family [53].

4.4. Social, Family, and Work Pressure

One of the most notable observations of the present study was the apparent lack of importance attributed to social, family, and work pressures on the decision to not have children (thus rejecting H1). In our regression analysis, it was observed that the pressure received by the non-mothers by these groups was not significant. In fact, these women seemed to resist the traditional expectations that drive them towards motherhood [44].

These results suggest that what could be occurring is a change in the social perception of non-motherhood. As opposed to previous periods in time, when women without children were seen with a certain stigma, today, not having children seems to be a more accepted option, and in some contexts, even valued. This change in thinking could be related to the growing participation of women in the labor market, and their desire to achieve professional goals before assuming family responsibilities [47]. In fact, Andalusia has some of the highest rates of risk and/or social exclusion (AROPE) [54] in Spain (37.5%), which increases when dealing with underage children households (44.7%); it is therefore not surprising that on many occasions, young people decide to go to other communities to find work, or dedicate more time to study, thus delaying the age of motherhood, to the point of not even considering it. This specific circumstance of the Andalusian region serves to illustrate, to a certain extent, that there is a lower perception of social pressure among those surveyed.

More specifically, in the workplace, women without children can be perceived in a more positive manner, as they are not “tied” to family responsibilities that could interfere with their professional performance. This has been documented in some studies that point out that in specific professional sectors, women without children have more opportunities for promotion and are viewed as more committed to their careers [53].

4.5. Limitations

The present study has limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. The first limitation is related to the size and representativeness of the sample. Although an adequate size was used for the analysis, it is possible that it may not have completely reflected the diversity of the population of women who have decided not to have children. The lack of representativeness of certain groups, such as women from different economic, cultural, or geographical contexts, may have restricted the ability to generalize the findings. To address this limitation, the research team is currently performing a more diverse and stratified recruitment effort, ensuring that women from diverse backgrounds are included in future research studies.

The second limitation is related to the omission of some variables that could have an influence on the decision to not become a mother. Although important factors were considered, such as age, marital status, and the partner’s decision, it is possible that other elements exist, such as education, religious beliefs, or the influence of communication media that may have a significant impact on this decision. To mitigate this limitation, the team is broadening the framework of research to include a more exhaustive analysis of these variables in future surveys.

The third limitation of this study concerns the variable of sexual orientation. A significant portion of the sample (43.1%) identified as lesbian, which may have influenced the overall results. This imbalance will be addressed in future research by aiming for a more proportionate representation of both heterosexual and homosexual women. We acknowledge that the current composition of the sample limits the generalizability of our findings to the broader population of women. However, we also recognize this as an opportunity to open a new line of inquiry. It raises an important question about whether sexual orientation—or more broadly, the choice or availability of a partner, as previously discussed—plays a causal role in the decision not to pursue motherhood. Rather than treating sexual orientation as a coincidental demographic factor, future studies could explore how different sexual identities intersect with values, expectations, and barriers related to motherhood. This could deepen our understanding of the diverse reasons behind non-motherhood and the social and personal factors that shape such decisions.

The fourth limitation is associated with the cross-sectional nature of the study, which impedes establishing causal relationships between the variables. Although some associations were observed between certain factors, such as marital status and the decision to not have children, it was not possible to determine if these variables were direct causes of non-motherhood. To address this problem, the research team is considering the design of longitudinal studies that allow for the evaluation of these relationships in the long term, and providing a more clear understanding of the causality.

The fifth limitation of this study concerns the measurement of feminist identity. Although the screening question regarding whether participants identified as feminists served as an initial filter, it did not allow for a nuanced understanding of the degree, type, or consistency of that identification. Feminism, as a complex and multifaceted ideology, can be experienced and interpreted in diverse ways, and a binary response may oversimplify this reality. Future studies could benefit from incorporating validated scales that measure feminist identification along multiple dimensions, providing a more accurate and in-depth profile of the participants. Additionally, the use of four-point Likert scales in the survey may have introduced certain limitations. While these scales were chosen to encourage respondents to take a clear position, the lack of a neutral midpoint and the absence of extreme polarizations may have restricted the ability to capture more subtle or ambivalent attitudes. Some participants may have felt forced to lean toward agreement or disagreement, even when their actual opinion was more moderate or undecided. Future research could explore alternative scaling options that allow for a broader range of response, including midpoint or bipolar items, to enhance measurement precision.

Lastly, the social perception of motherhood and the associated pressures can vary with time and between different cultures. This study was conducted in a specific cultural context, which limits the generalization of the results to other settings. To address this limitation, the research team plans to conduct studies in different geographical and period-of-time contexts, which could enrich our understanding of the non-motherhood dynamics in diverse cultures and periods, as previous studies have suggested [53].

4.6. Future Implications and Reflections

The results of this study provide several implications for future research. First, it would be interesting to explore how women who identify as feminists make reproductive decisions compared to those who do not consider themselves feminists. Since feminism advocates for women’s self-determination and their right to freely choose what to do with their bodies, there may be significant differences in the reasons for choosing not to become mothers between these two groups [44].

Secondly, while our results suggest that non-motherhood is losing its social stigma in some contexts, they also show that, in certain cases, it is still perceived negatively. This reflects a partial transformation of expectations about motherhood, but not a complete acceptance across all social spheres. As women gain more space in the workplace and greater control over their lives, it is possible that traditional expectations regarding motherhood will continue to change. However, this also raises the need to revise social and labor policies to adapt to these new realities [47].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study reveals that women who decide not to have children consider their marital status, the lack of a stable partner, the decision of their partner to not have children, not feeling the “call of nature”, and age to be important factors. These factors reflect increasing personal autonomy and a greater capacity to make decisions that are more centered on individual and relationship aspects than external pressures. More specifically, the absence of a stable partner and the decision of the partner to not have children are key determinant factors, which suggests that the relationship of the couple is still a crucial factor in the reproductive decisions of women, so that more research is needed along the lines of chance or causality in establishing relationships with partners who do not want to become fathers, voluntary singlehood, or even the selection of a female partner.

On the other hand, family and social pressures do not seem to be considered significant factors for this group, which could reflect a change in social and family norms and the expectations on the role of women in society. Women, in general, seem to have better control of their reproductive lives, which could be related to a better access to education, work, and their more active participation in the making of decisions, which tend to be mainly dependent on social expectations.

This shift in perspective could also be interpreted as a reflection of a deeper transformation of traditional roles and values, in which women can now more freely decide if they want to be mothers or not, more based on personal factors and less on external pressures. However, interesting factors are notable, such as the relevance of “biological desire” and age, which still play important roles in the decision process, which could reflect the persistence of certain biological aspects and expectations that still have an influence on the decision to become a mother.

Finally, we would like to stress the need for a type of feminism that takes into account the desires, opinions, and experiences of women who do not wish to be mothers, just as O’Reilly claims from the perspective of matricentric feminism [21] for those who exercise motherhood. Only by listening to these women will it be possible to understand the motivations that lead women to make this decision, beyond the stereotype of women that rules them out for biological or economic reasons, which, as we have seen, are not mentioned by those who really do not wish to be mothers. It would also be necessary to create a specific word that defines women who do not wish to exercise motherhood, a word that does not only define them by the denial of their motherhood.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.M.M. and M.M.H.; methodology, M.M.H.; software, R.M.M.M.; validation, R.M.M.M., M.M.H. and Á.A.G.; formal analysis R.M.M.M. and Á.A.G.; investigation, R.M.M.M.; resources, R.M.M.M.; data curation, M.M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.M.M., M.M.H. and Á.A.G.; writing—review and editing, R.M.M.M., M.M.H. and Á.A.G.; visualization, R.M.M.M.; supervision, Á.A.G.; project administration, Á.A.G.; funding acquisition, Á.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by P_LANZ_G_2023/001: “Call for Launchpad Research Projects on Women and Gender Studies of the University Research and Transfer Plan 2023, Program FEDER Andalucía 2021–2027”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was also was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Almeria (UALBIO 2022/038 and 20 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study and written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

This study is part of a broader national research project. As such, the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, in accordance with the data sharing policies of the larger project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rich, A. Nacemos de mujer. La Maternidad Como Experiencia e Institución; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-849-491-477-5. [Google Scholar]

- Federici, S. El Patriarcado del Salario. Críticas Feministas al Marxismo; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-849-480-683-4. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Tasa de Natalidad por Comunidad Autónoma, Según Nacionalidad (Española/Extranjera) de la Madre. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=1433 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Indicador Coyuntural de Fecundidad por Comunidad Autónoma, Según Orden del Nacimiento y Nacionalidad (Española/Extranjera) de la Madre. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=1441&L=0 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Edad Media a la Maternidad por Orden del Nacimiento Según Nacionalidad (Española/Extranjera) de la Madre. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=1579 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley 39/1999, de 5 de Noviembre, Para Promover la Conciliación de la Vida Familiar y Laboral de las Personas Trabajadoras; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 6 November 1999; Number 266; Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1999/11/05/39 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Real Decreto-Ley 2/2024, de 21 de Mayo; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 22 May 2024; Number 124; Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rdl/2024/05/21/2 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley 14/2006, de 26 de Mayo, Sobre Técnicas de Reproducción Humana Asistida; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 27 May 2006; Number 126; Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2006/05/26/14/con (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (BOJA). Decreto Legislativo 1/2009, de Consejería de Economía y Hacienda, de 1 de septiembre. Aprueba el Texto Refundido de las Disposiciones Dictadas por la Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía en Material de Tributos Cedidos, Versión Consolidada; Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (BOJA): Seville, Spain, 27 June 2018; Number 123; Available online: https://ws040.juntadeandalucia.es/sedeboja/web/textos-consolidados/resumen-ficha?p_p_id=resumenrecursolegal_WAR_sedebojatextoconsolidadoportlet&p_p_lifecycle=0&_resumenrecursolegal_WAR_sedebojatextoconsolidadoportlet_recursoLegalAbstractoId=21331 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Consejería de Salud y Consumo, Junta de Andalucía. Derechos, Ayudas, Beneficios y Prestaciones Públicas al Embarazo, Parto, Post-parto, Nacimiento, Cuidados y Atención de los Hijos e Hijas en Andalucía; Consejería de Salud y Consumo, Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2010; Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/saludyconsumo/areas/salud-vida/adulta/paginas/ive-maternidad.html#toc--derechos-ayudas-beneficios-y-prestaciones-p-blicas-al-embarazo-parto-post-parto-nacimiento-cuidados-y-atenci-n-de-los-hijos-e-hijas-en-andaluc-a (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Millet, K. Política Sexual; Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1995; ISBN 84-376-1399-X. [Google Scholar]

- de Beauvoir, S. El Segundo Sexo; Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-843-763-736-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A.M. La Mujer de La Ilusión. Pactos y Contratos Entre Hombres y Mujeres; Ediciones Paidós Ibérica: Madrid, Spain, 1995; ISBN 978-9501270242. [Google Scholar]

- Badinter, E. La Mujer y La Madre. Un libro Polémico Sobre la Maternidad Como Nueva Forma de Esclavitud; La Esfera de los Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-849-164-084-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila González, Y. Mujeres frente a los espejos de la maternidad: Las que eligen no ser madres. Desacatos 2005, 17, 107–126. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1607-050X2005000100007&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley Orgánica 10/2022, de 6 de Septiembre, de Garantía Integral de la Libertad Sexual; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 7 September 2022; Number 215; Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2022/09/06/10/con (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Ley Orgánica 1/2023, de 28 de Febrero, por la Que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2010, de 3 de Marzo, de Salud Sexual y Reproductiva y de la Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 1 March 2023; Number 51; Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2023/02/28/1 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Reid, G.B. Mujeres, deseo de hijo/a y ejercicio de la maternidad. Conclusiones. In Proceedings of the VII Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XXII Jornadas de Investigación XI Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR 2019, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–28 November 2015; pp. 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Donath, O. Madres Arrepentidas. Una Mirada Radical a la Maternidad y Sus Falacias Sociales; Reservoir Books: Madrid, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-8416709052. [Google Scholar]

- Zicavo, E. Dilemas de la maternidad en la actualidad: Antiguos y nuevos mandatos en mujeres profesionales de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. La ventana. Rev. Estud. Género 2013, 4, 50–87. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-94362013000200004&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- O’Reilly, A. Matricentric Feminism: A Feminism for Mothers. J. Mother. Initiat. 2019, 10, 16–26. Available online: https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/view/40551 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Agudo, A. No Soy Madre Porque No Quiero. Persiste La Presión Social a Favor de La Maternidad, Pero no de La Paternidad. La Mujer sin Hijos Suele ser Calificada Como Egoísta; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2013/09/20/actualidad/1379705104_604726.html (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Vázquez, C. La Libertad de no ser Madre: Tras Siglos de Convenciones y Prejuicios, Muchas Españolas Obvian la Presión Social y las Encuestas de Natalidad y Renuncian a Tener Hijos por Decisión Propia; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2018/12/21/actualidad/1545409859_592398.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Pew Research Center. The Experiences of U.S. Adults Who Don’t Have Children. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/07/PST_2024.7.26_adults-without-children_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. Encuesta de Fecundidad, Familia y Valores, 1st ed.; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-84-7476-448-2.

- Peterson, H.; Engwall, K. Silent bodies: Childfree women’s gendered and embodied experiences. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2013, 20, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, H. Fifty shades of freedom. Voluntary childlessness as women’s ultimate liberation. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2015, 53, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, H. “I Will Certainly Never Become Some Kind of Housewife.” Voluntary Childlessness and Work/family Balance in Sweden. Trav. Genre Sociétés 2017, 37, 71–89. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/journal-travail-genre-et-societes-2017-1-page-71?lang=en (accessed on 6 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Friedan, B. La Mística de La Feminidad; Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-376-3604-7. [Google Scholar]

- Letherby, G.; Williams, C. Non-motherhood: Ambivalent autobiographies. Fem. Stud. 1999, 25, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Mujeres Que no Tienen Intención de Tener Hijos en los Próximos 3 Años Según el Motivo más Importante de Esta Decisión y Edad. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?tpx=31778&L=0 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM—Principios Éticos Para las Investigaciones Médicas en Seres Humanos. Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud y Consejo de Organizaciones Internacionales de las Ciencias Médica. Pautas Éticas Internacionales Para la Investigación Relacionada con la Salud con Seres Humanos; Consejo de Organizaciones Internacionales de las Ciencias Médicas (CIOMS): Ginebra, Suiza, 2016; ISBN 978-92-9036088-9. [Google Scholar]

- LimeSurvey. Herramienta de Encuestas Gratuita. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/es (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Park, K. Stigma Management Among the Voluntarily Childless. Sociol. Perspect. 2002, 45, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. A Psychometric Evaluation of 4-Point and 6-Point Likert-Type Scales in Relation to Reliability and Validity. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 18, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rezende, N.A.; de Medeiros, D.D. How rating scales influence responses’ reliability, extreme points, middle point and respondent’s preferences. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, K.; Berry, P.; Harrington, M.; Crescioni, M.; Patel, M.; Rudell, K.; Safikhani, S.; Pease, S.; Vernon, M. Literature review to assemble the evidence for response scales used in patient-reported outcome measures. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2018, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-047-058-247-3. [Google Scholar]

- Berrington, A. Childlessness in the UK. Popul. Stud. 2017, 71, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P. Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2000, 26, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davia, M.A.; Legazpe, N. Factores determinantes en la decisión de tener el primer hijo en las mujeres españolas. Papeles Población 2013, 75, 1–30. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-74252013000100008&lng=es&nrm=iso> (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Gillespie, R. Childfree and feminine: Understanding the gender identity of voluntarily childless women. Gend. Soc. 2003, 17, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseknecht, S.K. Voluntary childlessness. Altern. Lifestyles 1978, 1, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colledge, H.E.; Runacres, J. “But why isn’t it an accomplishment not to have children?”: A Qualitative Investigation into Millennial Perceptions of Voluntarily Childless Women. Society 2023, 60, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.; Rindfuss, R.R.; McDonald, P.; Velde, E. Why do people postpone parenthood? Motives and social policy incentives. Hum. Reprod. Update 2011, 17, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.P.; Taylor, M.G. Low fertility at the turn of the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2006, 32, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waren, W.; Pals, H. Comparing characteristics of voluntarily childless men and women. J. Pop. Res. 2013, 30, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bram, S. Voluntarily childless women: Traditional or nontraditional? Sex Roles 1984, 10, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.E.; Cope, D.R. Some characteristics of intentionally childless wives in Britain. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1980, 3, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporale, S. Discursos Teóricos en Torno a Las Maternidades: Una Vision Integradora; Cyan Proyectos Editoriales: Madrid, Spain, 2005; ISBN 9788481985672. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.S. The parenthood effect on gender inequality: Explaining the change in paid and domestic work when British couples become parents. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 29, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano Ortiz, J.C.; Sanz Angulo, A. El Estado de la Pobreza en las Comunidades Autónomas. Pobreza y Territorio. Comunidades Autónomas y Unión Europea; European Anti Poverty Network (EAPN España): Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.eapn.es/ARCHIVO/documentos/documentos/1728917980_informe_arope_ccaa_europa_2024_.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).