Population Genetics to Population Genomics: Revisiting Multispecies Connectivity of the Hawaiian Archipelago †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Species

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Benchwork

2.4. Bioinformatics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| PLD | Pelagic larval duration |

| IBD | Isolation-by-distance |

| RAD | Restriction-enzyme assisted digest |

| MHI | Main Hawaiian Islands |

| NWHI | Northwestern Hawaiian Islands |

References

- Jablonski, D. Background and Mass Extinctions: The Alternation of Macroevolutionary Regimes. New Ser. 1986, 231, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohonak, A.J. Dispersal, Gene Flow, and Population Structure. Source Q. Rev. Biol. 1999, 74, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinlan, B.P.; Gaines, S.D. Propagule Dispersal in Marine and Terrestrial Environments: A Community Perspective. Ecology 2003, 84, 2007–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, W.F. Connectivity, Fragmentation, and Extinction Risk in Dendritic Metapopulations. Ecology 2002, 83, 3243–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blowes, S.A.; Connolly, S.R. Risk Spreading, Connectivity, and Optimal Reserve Spacing. Ecol. Appl. 2012, 22, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, F.W.; Byrne, M.; Luikart, G.; Aitken, S.N.; Funk, W.C. Conservation and the Genomics of Populations, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, J.M.; Fagan, W.F. Connectivity Metrics. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.R.; Sanjayan, M. (Eds.) Connectivity Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 113946020X/9781139460200. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen, R.K.; Gawarkiewicz, G.; Pineda, J.; Thorrold, S.R.; Werner, F.E. Population Connectivity in Marine Systems: An Overview. Oceanography 2007, 20, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beger, M.; Grantham, H.S.; Pressey, R.L.; Wilson, K.A.; Peterson, E.L.; Dorfman, D.; Mumby, P.J.; Lourival, R.; Brumbaugh, D.R.; Possingham, H.P. Conservation Planning for Connectivity across Marine, Freshwater, and Terrestrial Realms. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinlan, B.P.; Gaines, S.D.; Lester, S.E. Propagule Dispersal and the Scales of Marine Community Process. Divers. Distrib. 2005, 11, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.E.; Ruttenberg, B.I.; Gaines, S.D.; Kinlan, B.P. The Relationship between Dispersal Ability and Geographic Range Size. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatkin, M. Gene Flow in Natural Populations. Source Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1985, 16, 393–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puritz, J.B.; Toonen, R.J. Coastal Pollution Limits Pelagic Larval Dispersal. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, A.; Mohammed, A. Why Are Early Life Stages of Aquatic Organisms More Sensitive to Toxicants than Adults? In New Insights into Toxicity and Drug Testing; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, B.; Bruns, E. The Evolution of Juvenile Susceptibility to Infectious Disease. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20180844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.; Selkoe, K.A.; Watson, J.; Siegel, D.A.; Zacherl, D.C.; Toonen, R.J. Ocean Currents Help Explain Population Genetic Structure. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Watson, J.R.; White, C.; Horin, T.B.; Iacchei, M.; Mitarai, S.; Siegel, D.A.; Gaines, S.D.; Toonen, R.J. Taking the Chaos out of Genetic Patchiness: Seascape Genetics Reveals Ecological and Oceanographic Drivers of Genetic Patterns in Three Temperate Reef Species. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 3708–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Toonen, R.J. Marine Connectivity: A New Look at Pelagic Larval Duration and Genetic Metrics of Dispersal. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 436, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buston, P.M.; D’Aloia, C.C. Marine Ecology: Reaping the Benefits of Local Dispersal. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R351–R353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y.K.; Sewell, M.A.; Byrne, M.; Watson, J. Revisiting the Larval Dispersal Black Box in the Anthropocene. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 75, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counsell, C.; Coleman, R.; Lal, S.; Bowen, B.; Franklin, E.; Neuheimer, A.; Powell, B.; Toonen, R.; Donahue, M.; Hixon, M.; et al. Interdisciplinary Analysis of Larval Dispersal for a Coral Reef Fish: Opening the Black Box. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2022, 684, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austerlitz, F.; Dick, C.W.; Dutech, C.; Klein, E.K.; Oddou-Muratorio, S.; Smouse, P.E.; Sork, V.L. Using Genetic Markers to Estimate the Pollen Dispersal Curve. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 937–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weersing, K.; Toonen, R.J. Population Genetics, Larval Dispersal, and Connectivity in Marine Systems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 393, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Gaggiotti, O.E.; Treml, E.A.; Wren, J.L.K.K.; Donovan, M.K.; Toonen, R.J. The DNA of Coral Reef Biodiversity: Predicting and Protecting Genetic Diversity of Reef Assemblages. Proc. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20160354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, L. GST and Its Relatives Do Not Measure Differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 4015–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, C.E.; Karl, S.A.; Smouse, P.E.; Toonen, R.J. Detecting and Measuring Genetic Differentiation. In Phylogeography and Population Genetics in Crustacea; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans, P.G.; Hedrick, P.W. Assessing Population Structure: FST and Related Measures. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011, 11, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurby, S.; Barber, P.H. Theoretical Limits to the Correlation between Pelagic Larval Duration and Population Genetic Structure. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 3419–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, E.D.; Toonen, R.J.; Selkoe, K.A. A Coalescent Sampler Successfully Detects Biologically Meaningful Population Structure Overlooked by F-statistics. Evol. Appl. 2019, 12, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.W.; Marko, P.B. It’s About Time: Divergence, Demography, and the Evolution of Developmental Modes in Marine Invertebrates. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2010, 50, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, P.B.; Hoffman, J.M.; Emme, S.A.; Mcgovern, T.M.; Keever, C.C.; Nicole Cox, L. The ‘Expansion-Contraction’ Model of Pleistocene Biogeography: Rocky Shores Suffer a Sea Change? Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

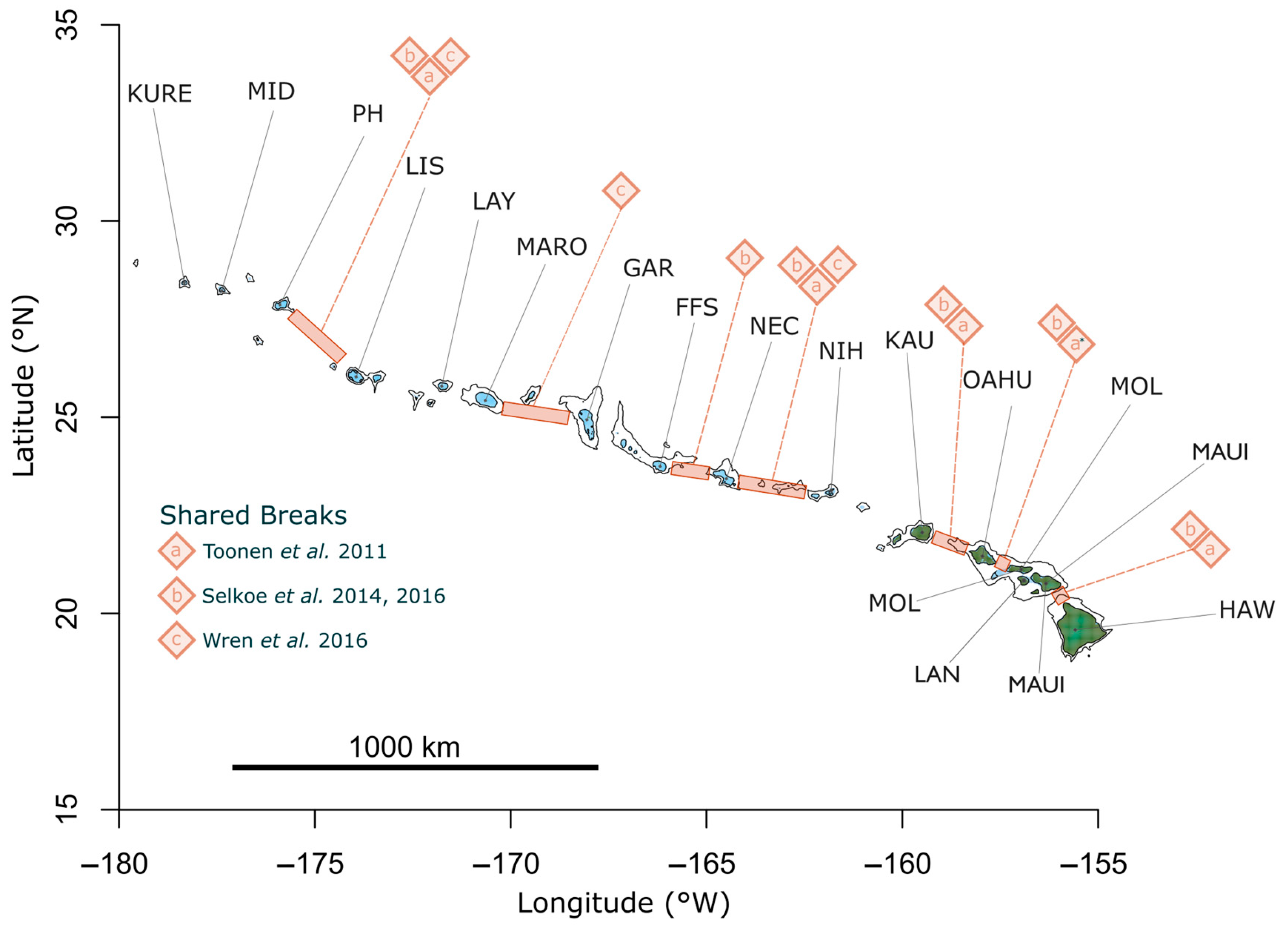

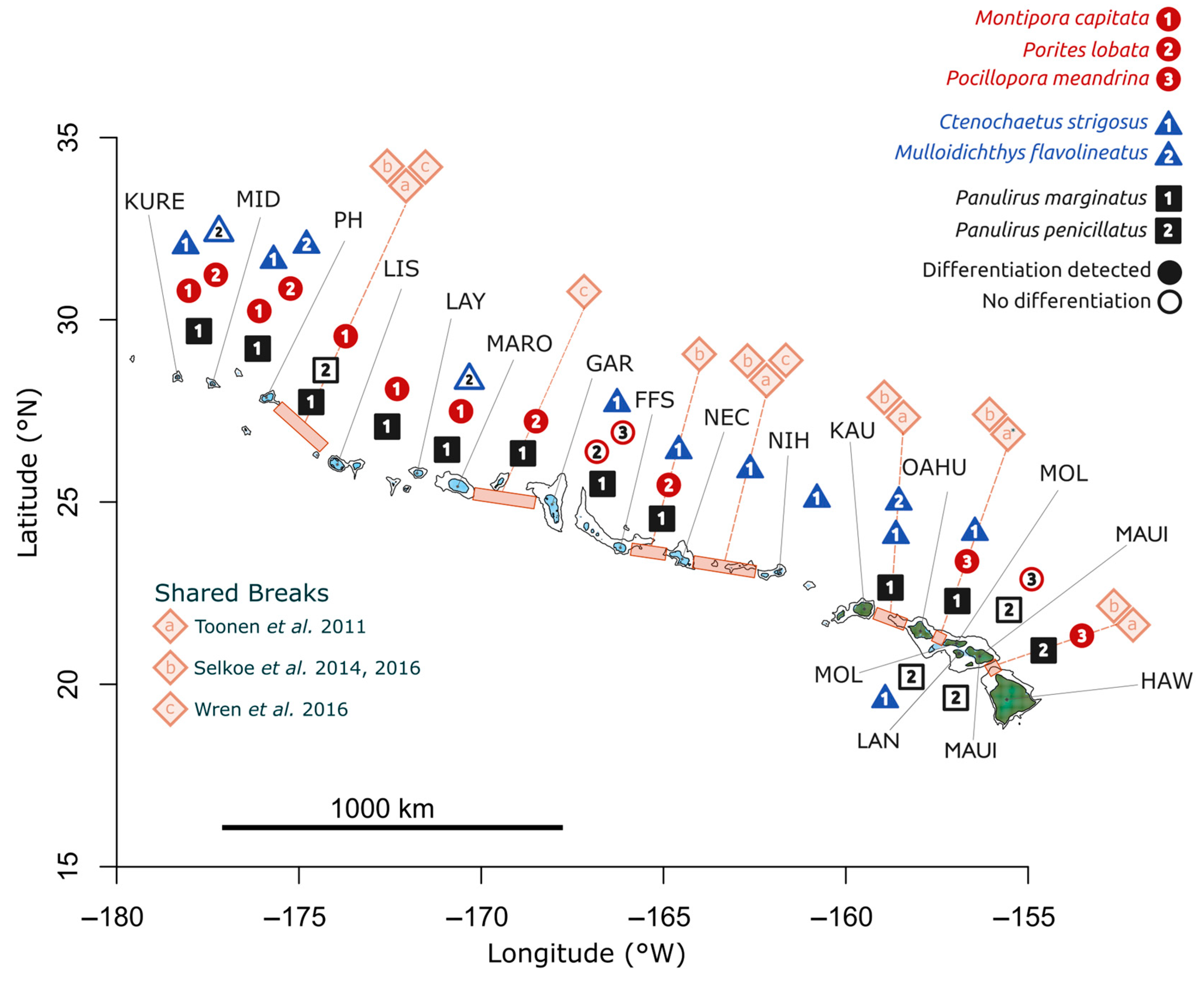

- Toonen, R.J.; Andrews, K.R.; Baums, I.B.; Bird, C.E.; Concepcion, G.T.; Daly-Engel, T.S.; Eble, J.A.; Faucci, A.; Gaither, M.R.; Iacchei, M.; et al. Defining Boundaries for Ecosystem-Based Management: A Multispecies Case Study of Marine Connectivity across the Hawaiian Archipelago. J. Mar. Biol. 2011, 2011, 460173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, A.M.; Donovan, M.K.; DeMartini, E.E.; Bowen, B.W. Dominance of Endemics in the Reef Fish Assemblages of the Hawaiian Archipelago. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 2584–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, J.L.K.; Kobayashi, D.R. Exploration of the “Larval Pool”: Development and Ground-Truthing of a Larval Transport Model off Leeward Hawai‘I. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Gaggiotti, O.E.; Bowen, B.W.; Toonen, R.J. Emergent Patterns of Population Genetic Structure for a Coral Reef Community. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 3064–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conklin, E.E.; Neuheimer, A.B.; Toonen, R.J. Modeled Larval Connectivity of a Multi-Species Reef Fish and Invertebrate Assemblage off the Coast of Moloka‘i, Hawai‘I. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, J.W.; Blaxter, M.L. RADSeq: Next-Generation Population Genetics. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2010, 9, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.R.; Good, J.M.; Miller, M.R.; Luikart, G.; Hohenlohe, P.A. Harnessing the Power of RADseq for Ecological and Evolutionary Genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, P.W. Conservation Genetics: Where Are We Now? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luikart, G.; England, P.R.; Tallmon, D.; Jordan, S.; Taberlet, P. The Power and Promise of Population Genomics: From Genotyping to Genome Typing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardis, E.R. The Impact of Next-Generation Sequencing Technology on Genetics. Trends Genet. 2008, 24, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, B.W.; Shanker, K.; Yasuda, N.; Celia, M.; Malay, M.C.D.; von der Heyden, S.; Paulay, G.; Rocha, L.A.; Selkoe, K.A.; Barber, P.H.; et al. Phylogeography Unplugged: Comparative Surveys in the Genomic Era. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2014, 90, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlötterer, C.; Tobler, R.; Kofler, R.; Nolte, V. Sequencing Pools of Individuals—Mining Genome-Wide Polymorphism Data without Big Funding. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futschik, A.; Schlötterer, C. The next Generation of Molecular Markers from Massively Parallel Sequencing of Pooled DNA Samples. Genetics 2010, 186, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, R.; Betancourt, A.J.; Schlötterer, C. Sequencing of Pooled DNA Samples (Pool-Seq) Uncovers Complex Dynamics of Transposable Element Insertions in Drosophila Melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luiz, O.J.; Allen, A.P.; Robertson, D.R.; Floeter, S.R.; Kulbicki, M.; Vigliola, L.; Becheler, R.; Madin, J.S. Adult and Larval Traits as Determinants of Geographic Range Size among Tropical Reef Fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16498–16502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.T.; McCormick, M.I. Microstructure of Settlement-Marks in the Otoliths of Tropical Reef Fishes. Mar. Biol. 1999, 134, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D.C. Growth in Juvenile Scarus Rivulatus and Ctenochaetus Binotatus: A Comparison of Families Scaridae and Acanthuridae. J. Fish Biol. 1993, 42, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, C.D. Recruitment of the Puerulus of the Spiny Lobster, Panulirus Marginatus, in Hawaii. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1986, 43, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polovina, J.J.; Moffitt, R.B. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of the Phyllosoma of the Spiny Lobster, Panulirus Marginatus, in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Bull. Mar. Sceince 1995, 56, 406–417. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B.; Booth, J.; Cobb, J.; Jeffs, A.; McWilliam, P. Larval and Postlarval Ecology. In Lobsters: Biology, Management, Aquaculture and Fisheries; Phillips, B., Ed.; Blackwell Scientific Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.W. Palinurid Phyllosoma Larvae from the Hawaiian Archipelago (Palinuridea). Crustaceana 1968, (Suppl. 2), 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.W. The Palinurid and Scyllarid Lobster Larvae of the Tropical Eastern Pacific and Their Distribution as Related to the Prevailing Hydrography. Bull. Scripps Inst. Ocean. 1971, 19, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H.; Takenouchi, T.; Goldstein, J.S. The Complete Larval Development of the Pronghorn Spiny Lobster Panulirus Penicillatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) in Culture. J. Crustac. Biol. 2006, 26, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, R.H. Energetics, Competency, and Long-Distance Dispersal of Planula Larvae of the Coral Pocillopora Damicornis. Mar. Biol. 1987, 93, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaither, M.R.; Szabó, Z.; Crepeau, M.W.; Bird, C.E.; Toonen, R.J. Preservation of Corals in Salt-Saturated DMSO Buffer Is Superior to Ethanol for PCR Experiments. Coral Reefs 2011, 30, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacchei, M.; Toonen, R.J. Caverns, Compressed Air, and Crustacean Connectivity: Insights into Hawaiian Spiny Lobster Populations. In Proceedings of the 29th American Academy of Underwater Sciences Symposium, Dauphin Island, AL, USA, 22–27 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Skillings, D.J.; Toonen, R.J. It’s Just a Flesh Wound: Non-Lethal Sampling for Conservation Genetics Studies. In Proceedings of the the 29th American Academy of Underwater Sciences Symposium, Seattle, Washington, 24–29 March 2025; pp. 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, I.S.S.; Puritz, J.B.; Bird, C.E.; Whitney, J.L.; Sudek, M.; Forsman, Z.H.; Toonen, R.J. EzRAD—An Accessible next-Generation RAD Sequencing Protocol Suitable for Non-Model Organisms_v3.2. protocols.io. Preprint 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polato, N.R.; Concepcion, G.T.; Toonen, R.J.; Baums, I.B. Isolation by Distance across the Hawaiian Archipelago in the Reef-building Coral Porites Lobata. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 4661–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concepcion, G.; Baums, I.; Toonen, R. Regional Population Structure of Montipora Capitata across the Hawaiian Archipelago. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2014, 90, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toonen, R.J.; Puritz, J.B.; Forsman, Z.H.; Whitney, J.L.; Fernandez-Silva, I.; Andrews, K.R.; Bird, C.E. EzRAD: A Simplified Method for Genomic Genotyping in Non-Model Organisms. PeerJ 2013, 1, e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F.; James, F.; Ewels, P.; Afyounian, E.; Weinstein, M.; Schuster-Boeckler, B.; Hulselmans, G.; sclamons. FelixKrueger/TrimGalore: Version 0.6.8 (0.6.8). Zenodo. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7579519 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, E.; Marth, G. Haplotype-Based Variant Detection from Short-Read Sequencing. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1207.3907. [Google Scholar]

- Puritz, J.B.; Hollenbeck, C.M.; Gold, J.R. DDocent: A RADseq, Variant-Calling Pipeline Designed for Population Genomics of Non-Model Organisms. PeerJ 2014, 2, e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The Variant Call Format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, E.; Kronenberg, Z.N.; Dawson, E.T.; Pedersen, B.S.; Prins, P. A spectrum of free software tools for processing the VCF variant call format: Vcflib, bio-vcf, cyvcf2, hts-nim and slivar. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, R.; Pandey, R.V.; Schlötterer, C. PoPoolation2: Identifying Differentiation between Populations Using Sequencing of Pooled DNA Samples (Pool-Seq). Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 3435–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautier, M.; Vitalis, R.; Flori, L.; Estoup, A. F-Statistics Estimation and Admixture Graph Construction with Pool-Seq or Allele Count Data Using the R Package Poolfstat. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022, 22, 1394–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, C. Interactive Web-Based Data Visualization with R, Plotly, and Shiny; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781138331457. [Google Scholar]

- Knaus, B.J.; Grünwald, N.J. VcfR: A Package to Manipulate and Visualize Variant Call Format Data in R. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T. Adegenet: A R Package for the Multivariate Analysis of Genetic Markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T.; Devillard, S.; Balloux, F. Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components: A New Method for the Analysis of Genetically Structured Populations. BMC Genet. 2010, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.-B. The Ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamvar, Z.N.; Tabima, J.F.; Grünwald, N.J. Poppr: An R Package for Genetic Analysis of Populations with Clonal, Partially Clonal, and/or Sexual Reproduction. PeerJ 2014, 2, e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of Molecular Variance Inferred from Metric Distances among DNA Haplotypes: Application to Human Mitochondrial DNA Restriction Data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijmans, R.J. Geosphere: Spherical Trigonometry, R package version 1.5-20; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rellstab, C.; Zoller, S.; Tedder, A.; Gugerli, F.; Fischer, M.C. Validation of SNP Allele Frequencies Determined by Pooled Next-Generation Sequencing in Natural Populations of a Non-Model Plant Species. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurland, S.; Wheat, C.W.; Paz Celorio Mancera, M.; Kutschera, V.E.; Hill, J.; Andersson, A.; Rubin, C.; Andersson, L.; Ryman, N.; Laikre, L. Exploring a Pool-seq-only Approach for Gaining Population Genomic Insights in Nonmodel Species. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 11448–11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Silva, I.; Randall, J.E.; Coleman, R.R.; Dibattista, J.D.; Rocha, L.A.; Reimer, J.D.; Meyer, C.G.; Bowen, B.W. Yellow Tails in the Red Sea: Phylogeography of the Indo-Pacific Goatfish Mulloidichthys Flavolineatus Reveals Isolation in Peripheral Provinces and Cryptic Evolutionary Lineages. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 2402–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.C.; Skaug, H.J.; Barshis, D.J. Next-Generation Sequencing for Molecular Ecology: A Caveat Regarding Pooled Samples; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 23, pp. 502–512. [Google Scholar]

- Marrotte, R.R.; Bowman, J.; Brown, M.G.C.; Cordes, C.; Morris, K.Y.; Prentice, M.B.; Wilson, P.J. Multi-Species Genetic Connectivity in a Terrestrial Habitat Network. Mov. Ecol. 2017, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Heyden, S.; Beger, M.; Toonen, R.J.; van Herwerden, L.; Juinio-Meñez, M.A.; Ravago-Gotanco, R.; Fauvelot, C.; Bernardi, G. The Application of Genetics to Marine Management and Conservation: Examples from the Indo-Pacific. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2014, 90, 123–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, E.D.; Riginos, C.; Bird, C.E.; Liggins, L.; Treml, E.; Beger, M.; Barber, P.H.; Connolly, S.R.; Cowman, P.F.; DiBattista, J.D.; et al. The Molecular Biogeography of the Indo-Pacific: Testing Hypotheses with Multispecies Genetic Patterns. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.E.; Holland, B.S.; Bowen, B.W.; Toonen, R.J. Contrasting Phylogeography in Three Endemic Hawaiian Limpets (Cellana spp.) with Similar Life Histories. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 3173–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, S.A.; Landguth, E.L.; Flather, C.H. Evaluating Population Connectivity for Species of Conservation Concern in the American Great Plains. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 2583–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L.R.; Martins, K.T.; Dumais-Lalonde, V.; Tanguy, O.; Maure, F.; St-Denis, A.; Rayfield, B.; Martin, A.E.; Gonzalez, A. Missing Interactions: The Current State of Multispecies Connectivity Analysis. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 830822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.P.; Palumbi, S.R. Genetic Structure Among 50 Species of the Northeastern Pacific Rocky Intertidal Community. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.R.; Luikart, G. Recent Novel Approaches for Population Genomics Data Analysis. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenlohe, P.A.; Funk, W.C.; Rajora, O.P. Population Genomics for Wildlife Conservation and Management. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, S.P.; Jones, A.G. The Future of Parentage Analysis: From Microsatellites to SNPs and Beyond. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, M.; Rao, I.A. SNP Testing in Forensic Science. In Forensic DNA Typing: Principles, Applications and Advancements; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Morgil, H.; Gercek, Y.C.; Tulum, I.; Morgil, H.; Gercek, Y.C.; Tulum, I. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in Plant Genetics and Breeding. In The Recent Topics in Genetic Polymorphisms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, P.W. Perspective: Highly Variable Loci and Their Interpretation in Evolution and Conservation. Evolution 1999, 53, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedrick, P.W. A Standardized Genetic Differentiation Measure. Evolution 2005, 59, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirmans, P.G. Using the AMOVA Framework to Estimate a Standardized Genetic Differentiation Measure. Evolution 2006, 60, 2399–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.S. The Relative Power of SNPs and Haplotype as Genetic Markers for Association Tests. Pharmacogenomics 2001, 2, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman, N.; Jorde, P.E. Statistical Power When Testing for Genetic Differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 2001, 10, 2361–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman, N.; Palm, S.; André, C.; Carvalho, G.R.; Dahlgren, T.G.; Jorde, P.E.; Laikre, L.; Larsson, L.C.; Palmé, A.; Ruzzante, D.E. Power for Detecting Genetic Divergence: Differences between Statistical Methods and Marker Loci. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 2031–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, P.A.; Martien, K.K.; Taylor, B.L. Assessing Statistical Power of SNPs for Population Structure and Conservation Studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hivert, V.; Leblois, R.; Petit, E.J.; Gautier, M.; Vitalis, R. Measuring Genetic Differentiation from Pool-Seq Data. Genetics 2018, 210, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, D.W.; Conklin, E.E.; Barba, E.W.; Hutchinson, M.; Toonen, R.J.; Forsman, Z.H.; Bowen, B.W. Genomics versus MtDNA for Resolving Stock Structure in the Silky Shark (Carcharhinus Falciformis). PeerJ 2020, 8, e10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conklin, E.E. Source To Sink: Modeling Marine Population Connectivity Acrossscales in The Main Hawaiian Islands. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hawai’i, Mānoa, HI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Keyse, J.; Crandall, E.D.; Toonen, R.J.; Meyer, C.P.; Treml, E.A.; Riginos, C. The Scope of Published Population Genetic Data for Indo-Pacific Marine Fauna and Future Research Opportunities in the Region. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2014, 90, 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacchei, M.; O’Malley, J.M.; Toonen, R.J. After the Gold Rush: Population Structure of Spiny Lobsters in Hawaii Following a Fishery Closure and the Implications for Contemporary Spatial Management. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2014, 90, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisthammer, K.H.; Forsman, Z.H.; Toonen, R.J.; Richmond, R.H. Genetic Structure Is Stronger across Human-Impacted Habitats than among Islands in the Coral Porites Lobata. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.R.; Kraft, D.W.; Hoban, M.L.; Toonen, R.J.; Bowen, B.W. Genomic Assessment of Larval Odyssey: Self-Recruitment and Biased Settlement in the Hawaiian Surgeonfish Acanthurus Triostegus Sandvicensis. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 102, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.R.; Tissot, B.N.; Albins, M.A.; Beets, J.P.; Jia, Y.; Ortiz, D.M.; Thompson, S.E.; Hixon, M.A. Larval Connectivity in an Effective Network of Marine Protected Areas. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, M.C.; McCauley, D.E. Indirect Measures of Gene Flow and Migration: FST≠1/(4Nm+1). Heredity 1999, 82, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wares, J.P. Community Genetics in the Northwestern Atlantic Intertidal. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, W.H.; Allendorf, F.W. What Can Genetics Tell Us about Population Connectivity? Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 3038–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waples, R.S. Separating the Wheat from the Chaff: Patterns of Genetic Differentiation in High Gene Flow Species. J. Hered. 1998, 89, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R. Effective Population Size/Adult Population Size Ratios in Wildlife: A Review. Genet. Res. 1995, 66, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.F.; Wares, J.P.; Gold, J.R. Genetic Effective Size Is Three Orders of Magnitude Smaller Than Adult Census Size in an Abundant, Estuarine-Dependent Marine Fish (Sciaenops Ocellatus). Genetics 2002, 162, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, M.P.; Nunney, L.; Schwartz, M.K.; Ruzzante, D.E.; Burford, M.; Waples, R.S.; Ruegg, K.; Palstra, F. Understanding and Estimating Effective Population Size for Practical Application in Marine Species Management. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organism | Life History Trait | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Name | Common Name | Geographic Range | PLD | Spawn Type |

| Ctenochaetus strigosus | Kole | HI endemic/ Johnston Atoll | 31–58.5 * [47,48,49] | Broadcast [47,48,49] |

| (Goldeneye surgeonfish) | ||||

| Mulloidichthys flavolineatus | Weke ʻaʻa | Indo-Pacific | 60.1 [47] | Broadcast [47] |

| (Yellowstripe goatfish) | ||||

| Panulirus marginatus | ʻUla poni | HI endemic | 6–11 mo (wild) [50,51,52] | Benthic [52] |

| (Hawaiian Spiny Lobster) | ||||

| Panulirus penicillatus | ʻUla | Indo-Pacific | 7–8 mo (wild) [52,53,54] | Benthic [52] |

| (Green Spiny Lobster) | 8.3–9.4 mo (lab) [54,55] | |||

| Montipora capitata | Koʻa | Pacific | 3 [36] | Broadcast [36] |

| (Rice Coral) | ||||

| Pocillopora meandrina | Koʻa | Indo-Pacific | 5–90 * [56] | Broadcast [56] |

| (Cauliflower Coral) | ||||

| Porites lobata | Pōhaku puna | Indo-Pacific | 3 [36] | Broadcast [36] |

| (Lobe Coral) | ||||

| Sampling Location | Site Code | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kure Atoll|° Mokupāpapa|* Hōlanikū | KURE | 28.3925 | −178.2936 |

| Midway Island|° Pihemanu|* Kuaihelani | MID | 28.2072 | −177.3735 |

| Pearl and Hermes Atoll|° Holoikauaua|* Manawai | PH | 27.8333 | −175.8333 |

| Lisianksi Island|° Papaʻāpoho|* Kapou | LIS | 26.0662 | −173.9665 |

| Laysan Island|° Kauō|* Kamole | LAY | 25.7679 | −171.7322 |

| Maro Reef|° Koʻanakoʻa|* Kamokuokamohoaliʻi | MARO | 25.415 | −170.59 |

| Gardner Pinnacles|° Pūhāhonu|* ʻŌnūnui, * ʻŌnūiki | GAR | 24.9988 | −167.9988 |

| French Frigate Shoals|° Kānemilohaʻi|* Lalo | FFS | 23.7489 | −166.1461 |

| Necker Island|°* Mokumanamana | NEC | 23.5749 | −164.7003 |

| °* Nihoa | NIH | 23.0605 | −161.9218 |

| °* Kauaʻi | KAU | 22.0964 | −159.5261 |

| °* Oʻahu | OAHU | 21.4389 | −158.0001 |

| °* Molokaʻi | MOL | 21.1444 | −157.0226 |

| °* Lānaʻi | LAN | 20.8166 | −156.9273 |

| °* Maui | MAUI | 20.7984 | 156.3319 |

| °* Hawaiʻi | HAW | 19.5429 | 155.6659 |

| Location | Species | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cstr | Mcap | Mfla | Pmar | Ppen | Pmea | Plob | Site Total | |

| Kure | 38 | 51 | 27 | 51 | — | — | 49 | 216 |

| Midway | 32 | 40 | 31 | 41 | — | — | 69 | 213 |

| Pearl and Hermes | 33 | 44 | 44 | 49 | 26 | — | 73 | 269 |

| Lisianski | — | 50 | — | 47 | 21 | — | — | 118 |

| Laysan | 30 | 46 | 10 | 57 | — | 25 | — | 168 |

| Maro Reef | — | 47 | 8 | 56 | — | — | 51 | 162 |

| Gardner Pinnacles | 29 | — | — | 58 | — | 25 | 47 | 159 |

| French Frigate Shoals | 37 | — | 28 | 47 | 47 | 23 | 39 | 221 |

| Necker | — | — | — | 58 | — | — | 35 | 93 |

| Nihoa | 29 | 24 | — | — | — | 23 | — | 76 |

| Kauaʻi | 28 | — | 60 | 50 | 53 | 25 | — | 216 |

| Oʻahu | 40 | 57*(2) | 57 | 54 | — | 96*(4) | 53 | 357 |

| Molokaʻi | 25 | — | — | — | 21 | 250*(7) | — | 296 |

| Lānaʻi | 38 | — | — | — | 38 | — | — | 76 |

| Maui | — | 47 | 25 | 34 | 25 | 25 | — | 156 |

| Hawaiʻi | 102 | — | — | — | 50 | 25 | 56 | 233 |

| Species Total | 461 | 406 | 290 | 602 | 281 | 517 | 472 | 3029 |

| Assembly | Species | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cstr | Mcap | Mfla | Plob | Pmar | Pmea | Ppen | |

| Contigs (>kbp) | 62,561 | 95,400 | 43,139 | 76,769 | 199,186 | 116,459 | 62,312 |

| Contigs (>5 kbp) | 5 | 1950 | 8 | 217 | 219 | 16,900 | 303 |

| Total length (>1 kbp) | 86,419,269 | 180,076,159 | 56,199,729 | 116,992,871 | 287,573,493 | 361,961,856 | 83,887,656 |

| Total length (>kbp) | 32,937 | 12,845,954 | 63,455 | 1,364,810 | 1,382,369 | 156,903,027 | 2,056,972 |

| Contigs | 498,704 | 426,901 | 460,296 | 539,291 | 1,464,336 | 613,555 | 1,057,498 |

| Largest contig | 10,392 | 23,892 | 11,369 | 17,063 | 12,510 | 116,710 | 20,773 |

| Total length | 315,209,420 | 370,567,895 | 299,344,044 | 377,542,905 | 965,778,094 | 599,711,333 | 644,510,677 |

| GC (%) | 41 | 40 | 45 | 40 | 43 | 39 | 43 |

| N50 | 679 | 958 | 635 | 691 | 702 | 1687 | 581 |

| N75 | 505 | 560 | 507 | 507 | 510 | 593 | 485 |

| L50 | 150,025 | 100,724 | 164,067 | 164,535 | 435,477 | 68,220 | 393,421 |

| L75 | 286,906 | 232,813 | 297,063 | 326,836 | 844,717 | 234,790 | 699,183 |

| N’s per 100 kbp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Species | Loci Scored | SNPs > 30x | Mean FST (Stderr) | Mean Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctenochaetus strigosus | 139,016 | 22,503 | 0.0586 (2.5 × 10−4) | 51.01 |

| Montipora capitata | 327,575 | 152,750 | 0.0275 (6.5 × 10−5) | 63.2 |

| Mulloidichthys flavolineatus | 84,314 | 25,180 | 0.0066 (2.4 × 10−4) | 44.21 |

| Panulirus marginatus | 127,447 | 43,842 | 0.0202 (9.8 × 10−5) | 57.37 |

| Panulirus penicillatus | 120,875 | 61,819 | 0.0084 (1.9 × 10−4) | 61.88 |

| Pocillopora meandrina | 262,600 | 86,391 | 0.0010 (1.3 × 10−4) | 57.54 |

| Porites lobata | 373,879 | 232,730 | 0.0133 (5.7 × 10−5) | 57.53 |

| 1,435,706 | 625,215 | 0.0194 | 56.11 |

| Species (Pool #) | Clustering Method | Degrees of Freedom | Between Variation | Within Variation | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| region | 1 | 0.79% | 99.21% | 0.158 | |

| C. strigosus | subregion | 5 | −2.34% | 102.34% | 0.716 |

| (n = 12) | goodfit k = 10 | 9 | 24.36% | 75.64% | 0.0001 |

| diffN k = 11 | 10 | 26.05 | 73.95% | 0.016 | |

| region | 1 | 2.72% | 97.28% | 0.105 | |

| P. meandrina | subregion | 3 | 5.37% | 94.62% | 0.003 |

| (n = 16) | goodfit k = 14 | 13 | 21.74% | 78.26% | 0.0001 |

| diffN k = 15 | 14 | 22.55% | 77.45% | 0.01 | |

| region | 1 | 5.16% | 94.84% | 0.06 | |

| M. capitata | subregion | 3 | 8.90% | 91.10% | 0.003 |

| (n = 10) | goodfit k = 8 | 7 | 12.31% | 87.69% | 0.006 |

| diffN k = 9 | 8 | 15.14% | 84.86% | 0.0001 | |

| region | 1 | 0.35% | 99.65% | 0.236 | |

| P. marginatus | subregion | 4 | 1.81% | 98.19% | 0.159 |

| (n = 12) | goodfit k = 10 | 9 | 7.42% | 92.58% | 0.003 |

| diffN k = 11 | 10 | 8.59% | 91.41% | 0.016 | |

| region | 1 | 0.32% | 99.68% | 0.162 | |

| P. penicillatus | subregion | 4 | 1.29% | 98.71% | 0.054 |

| (n = 8) | goodfit k = 6 | 5 | 1.86% | 98.14% | 0.0001 |

| diffN k = 7 | 6 | 2.09% | 97.90% | 0.0001 | |

| region | 1 | 0.55% | 99.45% | 0.214 | |

| P. lobata | subregion | 3 | 1.04% | 98.96% | 0.327 |

| (n = 9) | goodfit k = 7 | 6 | 11.54% | 88.46% | 0.0001 |

| diffN k = 8 | 7 | 11.40% | 88.61% | 0.03 | |

| region | 1 | 0.05% | 99.96% | 0.439 | |

| M. flavolineatus | subregion | 4 | 2.19% | 97.81% | 0.309 |

| (n = 9) | goodfit k = 7 | 6 | 18.14% | 81.86% | 0.01 |

| diffN k = 8 | 7 | 20.72% | 79.28% | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freel, E.B.; Conklin, E.E.; Knapp, I.S.S.; Kraft, D.W.; Johnston, E.C.; Forsman, Z.H.; Coleman, R.R.; Whitney, J.L.; Iacchei, M.J.; Bowen, B.W.; et al. Population Genetics to Population Genomics: Revisiting Multispecies Connectivity of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Fishes 2025, 10, 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120623

Freel EB, Conklin EE, Knapp ISS, Kraft DW, Johnston EC, Forsman ZH, Coleman RR, Whitney JL, Iacchei MJ, Bowen BW, et al. Population Genetics to Population Genomics: Revisiting Multispecies Connectivity of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):623. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120623

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreel, Evan B., Emily E. Conklin, Ingrid S. S. Knapp, Derek W. Kraft, Erika C. Johnston, Zac H. Forsman, Richard R. Coleman, Jonathan L. Whitney, Matthew J. Iacchei, Brian W. Bowen, and et al. 2025. "Population Genetics to Population Genomics: Revisiting Multispecies Connectivity of the Hawaiian Archipelago" Fishes 10, no. 12: 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120623

APA StyleFreel, E. B., Conklin, E. E., Knapp, I. S. S., Kraft, D. W., Johnston, E. C., Forsman, Z. H., Coleman, R. R., Whitney, J. L., Iacchei, M. J., Bowen, B. W., & Toonen, R. J. (2025). Population Genetics to Population Genomics: Revisiting Multispecies Connectivity of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Fishes, 10(12), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120623