Abstract

The modern financial world has seen a significant rise in the use of cryptocurrencies in recent years, partly due to the convincing lure of anonymity promised by these schemes. Bitcoin, despite being considered as the most widespread among all, is claimed to have significant lapses in relation to its anonymity. Unfortunately, studies have shown that many cryptocurrency transactions can be traced back to their corresponding participants through the analysis of publicly available data, to which the cryptographic community has responded by proposing new constructions with improved anonymity claims. Nevertheless, the absence of a common metric for evaluating the level of anonymity achieved by these schemes has led to numerous disparate ad hoc anonymity definitions, making comparisons difficult. The multitude of these notions also hints at the surprising complexity of the overall anonymity landscape. In this study, we introduce such a common framework to evaluate the nature and extent of anonymity in (crypto) currencies and distributed transaction systems, thereby enabling one to make meaningful comparisons irrespective of their implementation. Accordingly, our work lays the foundation for formalizing security models and terminology across a wide range of anonymity notions referenced in the literature, while showing how “anonymity” itself is a surprisingly nuanced concept, as opposed to existing claims that are drawn upon at a higher level, thus missing out on the elemental factors underpinning anonymity.

1. Introduction

Cryptocurrencies are undeniably one of the most attention-grabbing developments in security research of the last decade. They continue to open up new classes of inquiries for the crypto and distributed systems communities, while also arguably offering tangible financial benefits to the common man and woman. Consequently, their emergence as alternatives to traditional fiat currencies is reaching new heights [1,2].

Thanks to the blockchain technology, trust, the grease of financial transactions, can now be inferential rather than axiomatic. The decentralized nature, ease of conducting cross-border transactions, resistance to censure, and promises (or hopes) of privacy and anonymity are factors that have contributed towards this popularity. Bitcoin is the first and by far the most widely used true (By which we mean permissionless, fully decentralized, with democratic governance, and transparently operated—in other words, conducive to trust from first principles.) cryptocurrency at the time of this writing, and has attracted much attention with respect to its privacy and anonymity aspects.

Anonymity, from a broad perspective, means that with respect to a given group of entities, it is not possible to uniquely identify one entity from the rest in that group. This concept of anonymity has been widely discussed in the context of anonymous communication and also in anonymous information sharing. Consequently, many theoretical models have been developed to model anonymity, such as k-Anonymity [3] and approaches based on modal logic [4]. Some such studies present formalized terminologies to capture different aspects of anonymity [5], while some propose metrics that could be used to measure a quantitative notion thereof, e.g., as a degree of anonymity [6]. For better or for worse, these available theoretical frameworks have been borrowed for discussing anonymity in cryptocurrencies.

The absence of an acceptable level of anonymity and privacy could hinder the effectiveness of any currency scheme. Many traditional currency schemes are centralized systems where customers depend on another party to preserve the privacy of related information. For example, in a banking model, banks are bound by regulation to preserve the confidentiality of customer information. If the transaction history of a particular individual or entity was exposed to an outsider, it could result in many undesirable consequences, from a subjective sense of betrayal, to more concrete abuses such as misuse of that information to gain undue advantages in contract bidding. Even worse, if currency units came attached with transaction histories, it could lead to the blacklisting of specific units based on their use in unlawful activities in the past, or their involvement in boycotted operations, even though the units may have had only uncontroversial uses afterwards. As such, it is paramount to have a tolerable level of anonymity in a currency scheme in order to ensure its fungibility.

In relation to the anonymity of Bitcoin, it has been argued that the current Bitcoin framework only provides a level of “pseudonymity”, in place of anonymity, as transactions are linked to payment addresses in a big graph that is visible to all [7,8]. Detailed analyses of public bitcoin transaction data have shown that it is possible to uncover behavior patterns of Bitcoin users and trace their identities in real life [9,10,11].

As a consequence of this tension between the need for, and the lack of, effective anonymity in cryptocurrencies, a lot of energy has been expended with the primary focus of fulfilling that demand. Some solutions are centered around improving the anonymity of the Bitcoin framework (e.g., Zcash), whereas other approaches have sought to revisit the blockchain machinery in the design of new cryptocurrency schemes (e.g., Monero). In spite of many such solutions making claims of “anonymity”, further studies have shown that a majority of them could still be subject to deanonymization [12,13].

As rationalized in [14], despite a large number of studies around the topic of cryptocurrency anonymity, no standardized means are available to evaluate the actual level of privacy achieved by different cryptocurrencies. Many studies have been conducted in isolation using different metrics, with the consequence that it is not feasible to compare and benchmark the anonymity landscape in a reliable manner across various constructions. To make matters worse, it turns out that the very notion of anonymity itself, in such complex multi-party systems as decentralized cryptocurrencies, has been until now very poorly understood, and is anything but clear-cut. It is replete with nooks and crannies of special cases and limitations that could turn into so many vulnerabilities.

1.1. Our Contribution

The present study was initially motivated by the works in [7,8,14,15], which lifted the veil on the multiplicity of anonymity notions for cryptocurrencies, but stopped short of actually providing a crisp formalism for defining and using those notions.

Over the course of this study, we identified a very fine-grained structure for the intuitive notion of payment anonymity, parameterized through qualitative distinct definitions, which can be shown to be sensible and justifiable in appropriate scenarios. Moreover, our definitions follow patterns that make them amenable to being brought to order according to a logical taxonomy.

Our purpose in this work, therefore, is to initiate a comprehensive formal study of fine-grained notions of anonymity in payment systems. While the multiplicity of notions is truly a by-product of the diversity and complexity of cryptographic cash systems (both existing or envisioned), our framework is general enough to capture familiar instances such as intermediated banking transactions and interpersonal physical payments. Note that we do not intend to address the anonymity of the underlying implementation of currency schemes in this work, i.e., consensus or communication mechanisms.

Our main contribution in this context is the formulation of a theoretical framework that can be used to provide a systematic categorization of terminology related to anonymity of (crypto) currencies and to model anonymity across different instances of such currency schemes.

Before we even start discoursing of anonymity, we create a flexible framework to abstract the generic functionality of nearly arbitrary payment systems, as long as certain basic consistency, security, and financial soundness properties that we define are satisfied. We model notions of spendability, balance, and indemnification, among others, considered either in an absolute universal sense for all inputs, or with respect to adversaries granted access to helper oracles.

On this foundation, we then analyze the multiple precise ways in which a broad notion of anonymity can be envisaged, and we provide a common game-based security template that consolidates a massive group of explicit attacker scenarios. Our framework is based around the fundamental notion of distinguishability, leading to a security concept of indistinguishability, likely familiar to readers from other security definitions, and a weaker notion of unlinkability. These notions are further particularized to certain subjects such as transaction value, sender, recipient and metadata, and parameterized across multiple dimensions based on which information and capabilities are given to the adversary, including (or not) the ability to see or set the initial state, to access or choose ancillary public/private keys, to query and/or manipulate the system as it runs, and to access or choose other transaction data.

Throughout this rather expansive exercise, we strive to identify similarities between related notions, which allows us in certain instances to “compress” or abstract them according to a common template, cutting size, and tedium while boosting descriptive power. Some of the resulting definitions are not distinct, others are mere tweaks in a common template, and yet others will require individual treatment. In order to encapsulate these dispersed scenarios, we present a set of theorems, underpinning the relationships among them.

The take-away message from our effort is that (financial) anonymity is not an all-or-nothing binary property; it is far more subtle. We fully intend that our framework be used to clearly spell out what aspects of privacy a certain coin does or does not satisfy, across diverse implementations. Of course, one could be content with asking for absolute fungibility (think: isotopically pure melted gold), but that is likely not to lead us anywhere, as no cryptocurrency in existence comes close to reaching that goal. This only makes the need for a (much) more refined model, all the more pressing.

1.2. Other Related Work

As mentioned at the outset, many early studies have focused on quantitative analysis of publicly available Bitcoin transaction data such as payment addresses and values as the Bitcoin blockchain records all transaction details publicly.

One of the early studies conducted by Reid et al. [16] on the anonymity of Bitcoin, presents a passive analysis on publicly available transaction data by constructing two topological structures based on the connectivity of users and transactions showing how these data can be analyzed in many different ways compromising the anonymity of users. Some have attempted to quantify such data as in [11], where behavioral patterns and transaction flows are studied at the user level. Meiklejohn et al. [17] present a different characterization of Bitcoin transaction data by clustering user accounts in terms of several heuristics, thereby highlighting the gap between expected vs. actual level of anonymity in the Bitcoin network. A similar work done by Spagnuolo et al. [18] proposes a framework (named BitIodine) to extract Bitcoin user information, mainly aiming for forensic purposes. These studies evidently place more emphasis on the quantitative analysis while we follow a qualitative approach.

On a different note, some have attempted to formalize the anonymity concepts in a theoretical manner. In this regard, a majority of the work conducted in the Bitcoin system evaluates the level of anonymity based on the notion of so-called linkability, yet with different interpretations. Androulaki et al. [10] conducted an analysis of Bitcoin privacy based on activity unlinkability and profile indistinguishability. In this work, unlinkability is defined in relation to addresses and transactions (independently) with respective users, whereas profile indistinguishability refers to clustering of users based on addresses or transactions. This interpretation of unlinkability has been applied in several subsequent studies related to the anonymity of Bitcoin [19,20,21]. From these studies, it is apparent that Bitcoin anonymity cannot be defined at the transaction layer as addresses and transactions are linkable by the construction itself.

As Bitcoin receives much criticism to that effect, new currency schemes have emerged more promising anonymity expectations, which has led to the need for more concrete formalization of anonymity concepts. Zcash is one such scheme which supports two types of transactions: “shielded” and “unshielded”. Shielded transactions are encrypted, and therefore conceal the addresses and values involved, thereby claiming to acquire improved levels of anonymity. However, users have the option to choose the transaction type, and thus they end up creating unshielded transactions at some point, where they work similar to Bitcoin transactions. Several experimental studies have shown that it is prone to linkability [22,23]. Linkability in this context is defined as the ability to link transactions and the corresponding payment addresses, and they claim that shielded transactions eventually end up in transparent addresses [23].

Cryptonote is one of the protocols based on which several currency systems have been constructed with improved anonymity claims. Saberhagen [24], in the original Cryptonote paper, states that a fully anonymous currency scheme should satisfy two properties with respect to anonymity: unlinkability and untraceability. Unlinkability in this work refers to the property that given two transactions, it is not possible to identify whether both transactions were intended to the same party, whereas untraceability is defined as the inability to identify the corresponding sender among a set of possible senders for a given transaction. Monero, which originated from the Cryptonote protocol, then claimed to provide untraceable transactions and untraceable payments. However, these two properties have fallen to deanonymization attacks in many subsequent studies through the analysis of Monero transaction data [13,25,26].

Fungibility, which is the property of every currency unit being identical, is regarded by many as an elementary requirement of any currency scheme, but it is a tall order. It is well accepted that Bitcoin is not fungible [8,27]. Although it has been claimed in [23] that Zcash achieves fungibility through its use of zk-SNARK (zero-knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge) proofs, the survey study in [8] makes the countermanding claim that Mimblewimble is the only cryptocurrency scheme to do so. Even so, the original Mimblewimble is insecure, and the fix proposed in [28], by making it preserve a lot more data, reintroduces the coin history removed in the original fungibility claim [29].

A recent work by Biryukov et al. [30] presents an experimental analysis on deanonymization of sample transactions in several cryptocurrencies based on network analysis. The outcomes are presented in terms of anonymity degree, which provides an information-theoretic notion of anonymity as a metric external to the scheme being studied. The study, however, stresses the need for a common mechanism that could be used to measure the effectiveness of various techniques used by different currency schemes in their search of anonymity.

Cachin et al. [31] proposed a formal model for blockchain systems by modeling the transactions in terms of a graphical structure called Transaction Graphs, focusing on three different blockchain systems: Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Hyperledger Fabric. While this work focuses on the semantics of a blockchain, our model deviates from this as our emphasis is on modeling anonymity based on the functionality of a currency scheme, as opposed to the underlying construction.

With this background, many have attempted to evaluate and compare the level of anonymity achieved by different cryptocurrencies through diverse means. Among the academic literature, the survey conducted by Khalilov et al. [7] presents a comprehensive categorization on a wide range of cryptocurrencies. They attempted to group the underlying constructions of these schemes around three aspects of anonymity: untraceability, hidden values, and hidden IP addresses. A similar study was carried out by Conti et al. [8], which discusses the privacy aspects of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as a comparison of advantages and disadvantages in terms of privacy and anonymity with respect to unlinkability, untraceability, deniability, and fungibility, yet without providing formal definitions. Further, the work in [14] presented a survey of several cryptocurrencies with respect to a set of qualitative anonymity properties such as fungibility, unlinkability, untraceability, hidden values, and unlinkability of IP addresses. Without formally defining those properties, they used them to compare cryptocurrencies over multiple dimensions. In a more recent survey paper, Alsalami et al. [15] presented a systematic grouping of a chosen set of cryptocurrencies in terms of four privacy tiers: pseudonymity, set anonymity, full anonymity, and confidential transactions, based on two characteristics: the ability to break links between transactions and hiding user identities. However, this categorization also, similar to the work in [7], provides a very high level picture of the anonymity levels based on the techniques used by the schemes, which is orthogonal to our work.

Nevertheless, these studies, mostly based on experimental analyses or specific constructions, do not necessarily facilitate the assessment and comparison of cryptocurrencies in terms of a common, fine-grained, formal qualitative model of anonymity. Table 1 compares the terminology used to model anonymity in above studies with our work.

Table 1.

Comparison with similar work.

1.3. Research Question

As evident from the above, there is no existing means for modeling anonymity uniformly across diverse constructions. Further, the presence of a wide range of notions suggests that anonymity depends on a number of factors. As a result, current claims of anonymity cannot be apprehended in a qualitative manner. Accordingly, we formulate our research question as follows.

How can we achieve a fine-grained systematization of anonymity modeling suitable for massively decentralized systems such as modern cryptocurrencies?

As such, we follow the research methodology below to devise a suitable means to achieve the above.

1.3.1. Research Methodology

Our research methodology is focused around constructing a common unifying mathematical framework, which is able to capture all the multiple security nuances in all existing and future schemes, following the accepted approach in cryptography which is to define security properties in terms of “games” or conceptual experiments. We choose game-based definitions over the Universal Composability (UC) framework because the former are intuitive and can be agreed upon by non-specialists (much less non-cryptographers). This is essential as a bridge between theory and applications. Further, UC is a very nice theoretical methodology which is best suited for small primitives whose ideal functionalities may still have a clean description, which is certainly not the case in the context of cryptocurrencies.

The first step in this process is to define a generic cryptocurrency scheme which depicts the functionality of a typical decentralized currency scheme, while ensuring its correct and secure functionality. We do not consider the particulars of the underlying communication network or the consensus mechanism here as they may be unique to each scheme. Instead, we focus on the functionality which enables us to define a universal framework irrespective of the implementation-specific elements.

Based on this currency scheme, we then construct a comprehensive adversarial model, which encapsulates a wide range of attacker scenarios by investigating different security aspects. This lays the foundation for our conceptual framework, which is the essence of this work. Thereafter, we devise a game to model various settings affecting anonymity of a currency scheme, leading to a set of granular anonymity notions that are unique and precise, and are able to provide a unified framework for modeling anonymity.

1.3.2. Conceptual Framework

As already stated, this framework is formulated using game-based security modeling. It is a commonly accepted method in cryptography, which makes it easy to capture adversarial goals under well-defined adversarial capabilities. Each capability defines a unique attacker scenario, which is usually represented by a unique game (or a conceptual experiment). As in our case there are so many to consider, we came up with a methodology which involves defining a parametric experiment, which allows us to parameterize in terms of adversarial capabilities along multiple dimensions, each of which on a rising scale from no access to informational to manipulative to full control. Further details of this conceptual framework are discussed in Section 3 under Security.

1.4. Implication of the Research

As summarized in Table 1, the diversity of existing anonymity modeling methods highlights the inability to compare anonymity achieved by decentralized currency schemes. Conversely, our work uncovers the granularity of anonymity through a plethora of distinct definitions, each representing a different aspect of anonymity. While a multitude of separate definitions may seem absurdly excessive, we emphasize that these definitions arise naturally from considering the possible interactions between the adversary and the cryptocurrency. Indeed, our notions generalize many security notions familiar to cryptographers such as known vs. chosen plaintext, forward security, indistinguishability, active vs. passive adversaries, and so on. The fact that we consider all of these security dimensions simultaneously multiplies the number of definitions, but also allows us to meaningfully understand and compare the anonymity of systems that differ along multiple dimensions. As a consequence, this work provides a means for modeling anonymity in a precise and qualitative manner.

2. Proposed Model

We start by constructing a model for a cryptocurrency scheme in terms of a set of algorithms which depicts the overall functionality of a generic cryptocurrency scheme.

A currency scheme is defined in terms of a security parameter and the initial state of the system, is called the genesis state. The scheme consists of a set of payment addresses, each consisting of a private key and a public address or identity. A transaction takes place between multiple senders and recipients, and consists of a private and a public part. A minting operation collects unminted transactions at any given point in time and generates a new state. New currency units are generated as a result of the minting process, as per the underlying implementation of the scheme. The adjudicate operation selects the rightful new state of the system. A system state p is defined by the implementation and will typically record all payment addresses and transactions that are valid in that instance. In Bitcoin, for example, the blockchain is the state. Every valid state descends from a valid checkpoint state, which descends from another checkpoint state or the genesis state. Accordingly, consecutive states of the scheme form a partial ordering with respect to the internal system specifications. We use the notation given in Table 2 throughout the document in order to represent the scheme and its operations mathematically.

Table 2.

Notation.

2.1. A Generic Cryptocurrency Scheme

We define a generic cryptocurrency scheme as follows.

Definition 1.

A cryptocurrency scheme Π, is defined in terms of security parameter λ and with the functionality prescribed by means of a set of algorithms; {Init, CreateAddr, IsValidPubAddr, IsValidSecAddr, GetBalance, CreateTxn, IsValidPubTxn, IsValidSecTxn, ExtractSenderPubAddr, ExtractRecipientPubAddr, ExtractInputVal, ExtractOutputVal, IsMintable, Mint, Adjudicate, IsValidState, IsGenesisState, CreateCheckpointState, RetrieveCheckpointState}.

Functionality

Table 3 summarizes the structure of the algorithms of the scheme. The initial setup of the scheme is defined by the algorithm in terms of a security parameter , and this process generates the genesis state. The payment address creation process, , takes an identity and some randomness, and generates a public–private key pair () and a transaction, which can be minted to register the addresses. Public and private keys can be validated with respect to a given state, p. A transaction is created with unspent funds from one or more senders () and corresponding funds for recipients (), together with transaction related metadata m such as corresponding IP addresses or other system-specific data. The validity of a transaction can be defined with respect to its public part as well as both public and private parts taken together. The difference between the total input value and the total output value is considered as transaction fees. Further, transaction-related data (input–output values and public keys of senders and recipients) can be extracted from a given transaction, if both public and private parts of the transaction are known.

Table 3.

Functions.

A minting operation takes place on a set of public parts of transactions and new currency units may be generated through this process, whose value is decided by the implementation specifications, internally. These minted currency units and respective transaction fees, collectively termed as excess value (), are collected by the miners. The preferred state out of a set of candidate states is chosen to be the subsequent state of the system through the operation by preserving the precedence of states. The algorithm checks the validity of a given state with respect to a given security parameter. A given state can be designated as a checkpoint state through the function based on the particulars of the state, which can be retrieved later through the operation. The genesis state is considered as the first checkpoint and the algorithm can be used to identify the genesis state corresponding to a given security parameter.

Note that we model only the generic functionality of a cryptocurrency scheme in this scheme. Therefore, we do not consider the specifics of the underlying consensus mechanism or the network in this work. However, there may be additional functionality associated with real world cryptocurrency systems, e.g., Smart contracts with Ethereum. In order to capture such additional features, we define a supplementary function . This enables us to realize the security implications of functionality of a scheme that may be outside our base model.

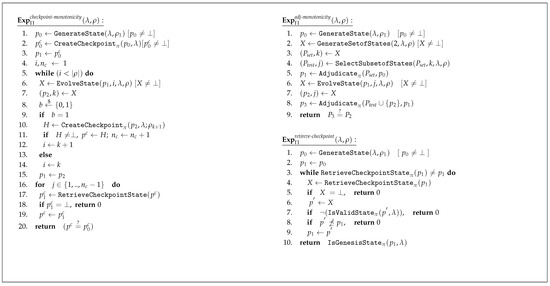

3. Correctness

The correctness of our model is established in terms of a set of experiments, which collectively ensure the expected functionality of the currency scheme.

Correctness Properties

We define several experiments in order to ensure the correctness of the currency scheme for all valid parameter values of and (Table 4). Experiments corresponding to these properties are listed in Appendix A. Accordingly, the correctness of the proposed scheme is defined as follows.

Table 4.

List of experiments for correctness.

Definition 2 (Correctness of the Cryptocurrency Scheme).

A currency scheme Π is correct if, for all security parameters , for all sufficiently long bit strings , and for all {init, create-addr, create-txn, extract-txn-data, mint, adjudicate, adj-monotinicty, create-checkpoint, retrieve-checkpoint, genesis-state, checkpoint-monotinicity}, returns 1.

4. Security

We establish the security requirements for the proposed framework through a game-based approach. For this purpose, we define a comprehensive adversarial model to accommodate a wide range of capabilities on the part of the adversary. Then, we define security requirements for the functionality of the proposed currency scheme. Anonymity aspects, although related to security, are discussed in a separate section as it is the main focus of this paper.

4.1. Adversarial Model

In game-based security modeling, the first task is to establish the adversarial objective corresponding to each security property. Then, we identify the factors affecting the adversary’s actions, which we term as adversarial capabilities. Both objectives and capabilities together form the variables in this model and are independent in their own right. Further, adversarial capabilities can be grouped in terms of what information the adversary knows (adversarial knowledge) and what actions the adversary can execute (adversarial power). Combining the objective and capabilities of the adversary, we formulate a conceptual game, which mimics an instance of a given system between the adversary and a challenger, specifying the conditions on which the adversary can win the game. The adversary’s advantage of winning the game (or its success probability) is the factor that decides whether the system under study facing an adversary with the specific capabilities and objectives is secure. In this case, we can consider this advantage as the dependent variable in this framework. If the advantage is non-negligible, then we say that the system is not secure against that adversary.

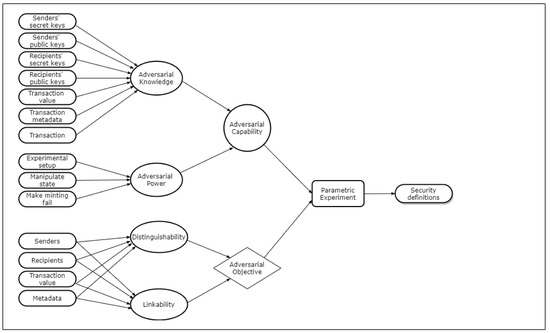

In the context of cryptocurrencies, adversarial capabilities depend on a number of factors, which collectively results in a series of unique attacker scenarios. The adversary’s knowledge of public/secret keys of senders and recipients, value and metadata of a given transaction, and other transaction data correspond to adversarial knowledge. The ability to setup the initial state, to manipulate the state, and to cause minting to fail are the variables corresponding to adversarial power. Further, the adversarial objective can also be manifold, and we consider indistinguishability and unlinkability with respect to anonymity of senders, recipients, transactions etc. (we discuss these notions in detail in subsequent sections). Each adversarial goal, when combined with different capabilities, results in a large number of attacker scenarios. We construct a single parametric experiment to capture all possible adversarial capabilities, with each parameter combination resulting in a distinct security definition. This conceptualization is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of the adversarial model.

We introduce a set of parameters to represent the above-stated variables. Adversary’s access to knowledge is parameterized by , where access to specific information is represented by a subscript corresponding to entities, sender (), recipient (), value (), and metadata (). With regards to the adversarial power, parameter represents how the state initialization in the experimental setup is handled. The parameter represents the ability to manipulate the state. In addition, the parameter denotes whether the adversary has the ability to cause minting to fail. Further, we introduce additional parameters later to represent adversarial goals to study anonymity considerations.

The adversary’s access to knowledge is modeled in terms of different levels of access to information, ranging from no access to informational, manipulative, and full access, respectively. These parameter values start from 0, and increasing values represent increasing level of access. When any knowledge parameter has a value of 0, corresponding entity of that parameter is considered to be hidden from the adversary. We assume that the adversary has oracle access through opaque handles to those hidden entities using which desired activities can be initiated through relevant oracles. A value of 1 in these parameters represents the situation where the adversary learns the corresponding entity at the end of the game, just before he makes his choice. Beyond that point, the adversary is not allowed to create or mint any transactions involving those entities. With the parameter on the other hand, the public part of the transaction is revealed to the adversary when . When , the secret part of the transaction is revealed and with , the randomness of the actual coins is revealed. Further, when , the adversary gets to choose the randomness for the transaction and finally the adversary gets to create the transactions when . For other parameters, with a value of 2, relevant information is known to the adversary throughout the game in real time via appropriate oracle access. However, for all those cases, the adversary does not have control over the entities. Conversely, for any value higher than 2, the adversary has some form of control over the relevant entity as explained in Table 5.

Table 5.

Parameters of the adversarial model.

In the case where , the state initialization is performed honestly with hidden randomness. A value of 1 represents a scenario where an honest state initialization takes place with public randomness. For values , the adversary has some control over the state initialization as listed in Table 5. With , the system state is hidden from the adversary. Similar to the state initialization, the adversary has control over the state when . The parameter on the other hand, only takes two values 0 and 1 to say whether the adversary can cause minting to fail.

With this parameterization, we can capture a wide range of adversaries ranging from passive (with all parameters equal to zero) to static (with , ) and adaptive adversaries (with parameter values greater than 1).

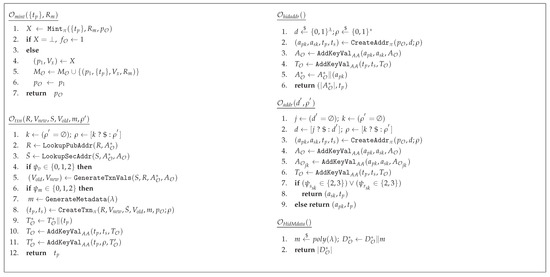

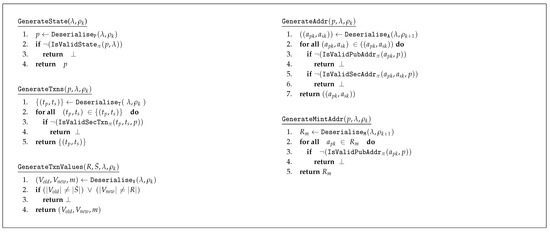

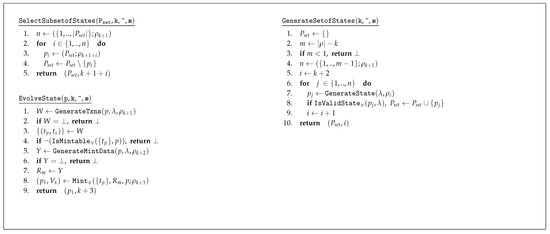

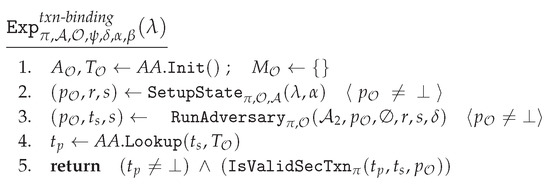

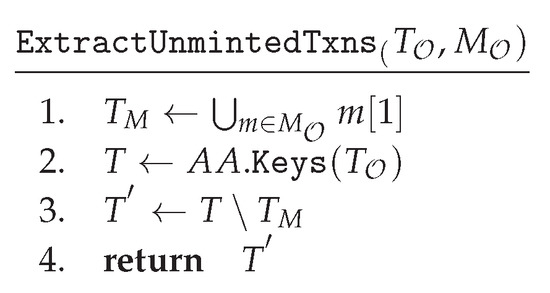

4.2. Helper Functions

We define a group of oracle functions to provide the adversary with access to honest functionality during the execution of the game (Figure 2). These include for creating addresses, for creating hidden addresses, for creating transactions, and for minting. Another oracle is defined to generate hidden metadata (). The history of the activities of the oracles are maintained globally within the games, i.e., as associative arrays and as a set to store all addresses, transactions, and minting history, respectively. In addition, , and are maintained as sets to store hidden addresses, transactions, and metadata, whereas stores the randomness of the coins spent in transactions. In order to cater for the addresses created with different adversarial inputs, the oracle keeps track of different groups of addresses in with binary values j and k, and a value of 0 representing adversarial identity and adversarial randomness, respectively. sets the flag globally, if a minting operation fails, in which case the adversary loses the game, unless = 1. The adversary has access to all available oracles, unless specifically mentioned with a specific subscript in the games. Table 6 summarizes the variables used by the oracles.

Figure 2.

Oracle functions.

Table 6.

A summary of oracle variables.

Further, the current state of the system is denoted by for these games. It is assumed that is updated as the state evolves within the game (e.g., through oracle calls with side effects, which is what the subscript tries to convey), except where a new state is generated through a mint operation, in which case the new state is denoted with a different subscript, e.g., .

Additionally, we also define a set of helper functions to be used in the security games as given in Figure 3 to improve the clarity of the games. The function performs the state initialization based on INIT, whereas the function executes an instance of the adversary denoted by different subscripts based on ACT. and functions are used to obtain public keys and private keys from hidden addresses, respectively. In addition, outputs the corresponding to a hidden transaction when . function is used when , to generate required input and output transaction values, based on the the maximum transaction value given by the adversary. Further, function generates metadata values required for a transaction when while is used to obtain hidden metadata when .

Figure 3.

Helper functions.

4.3. Security Properties

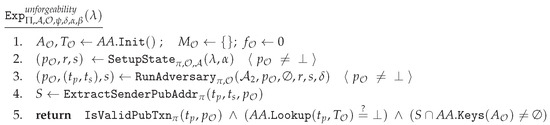

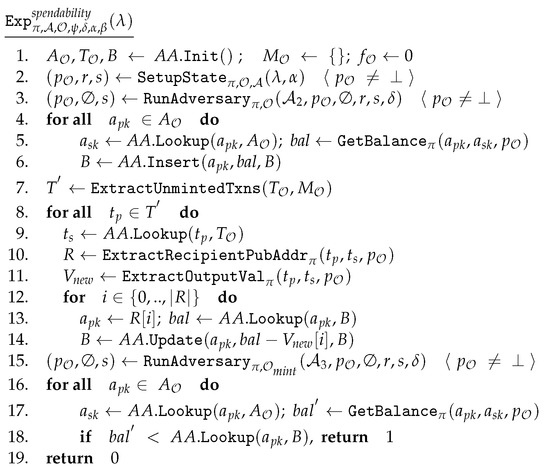

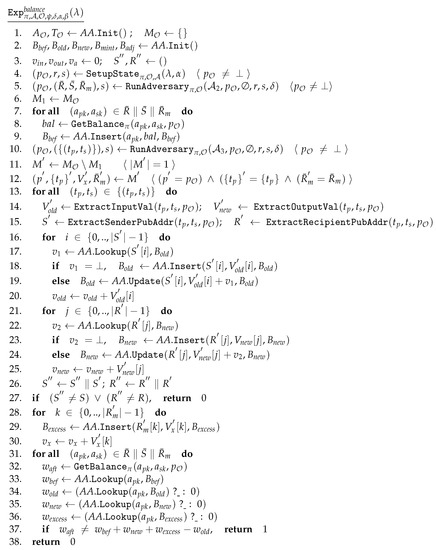

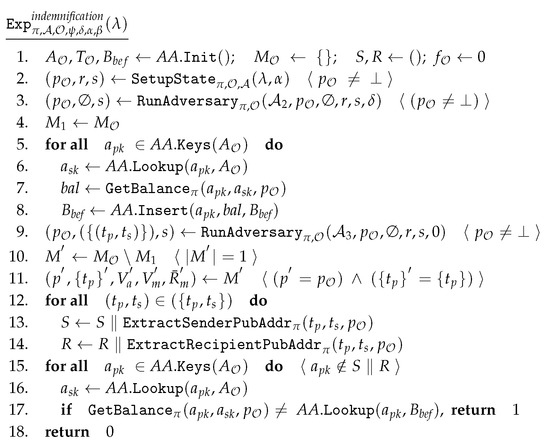

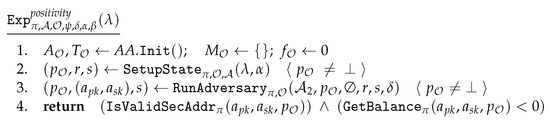

First, we define a set of properties to ensure the functional security of the proposed scheme. These are defined by means of game-based experiments around several attributes: Unforgeability, Transaction binding property, Spendability, Balance property, Descendency, and Anonymity. Each property is demonstrated with respect to attacker’s goals and we construct appropriate games to model adversarial behavior explained earlier.

The unforgeability property ensures that it is not possible to spend the funds associated with a payment address without the knowledge of the secret key corresponding to that payment address. The transaction binding property establishes the requirement that the secret part of a transaction cannot be tampered with and ensures that binds with a unique , i.e., a given cannot correspond to two different s. Spendability guarantees that the funds associated with a payment address (a) cannot decrease unless the corresponding secret keys are known, i.e., only if secret key of a is known . The property of Indemnification requires that fund balances associated with the payment addresses that are not involved in a transaction should remain unchanged.

The balance property requires that the fund balances of participants in a transaction are updated correctly. Further, the balances of miners’ addresses should also be updated correctly with relevant transaction fees and mint values (). These goals can be summarized for a set of transactions involved in one minting operation as follows:

A single experiment is defined to capture all three goals, so that the balances cannot be manipulated by an adversary.

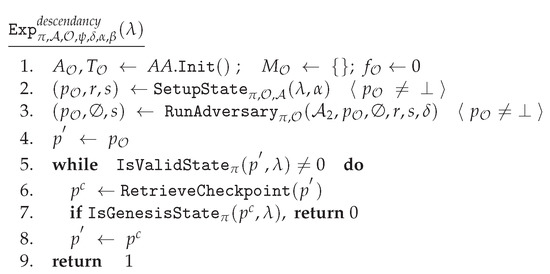

Positivity ensures that the fund balance corresponding to each payment address in the system is non-negative at all times. The descendancy property requires that an adversary should not be able to produce a valid system state, which does not descend from the genesis state.

We construct individual games (i.e., conceptual experiments) to represent all the above properties, and relevant details are included in Appendix B. Accordingly, we formally define the security of a currency scheme constructed as per Definition 1 in terms of those experiments as follows.

Definition 3 (Security of the currency scheme).

For {unforgeability, txn-binding, spendability, balance, indemnification, positivity, descendancy}, a currency scheme Π is said to be -secure with respect to Y if for every PPT adversary and for all possible values of and β, the advantage of winning the security experiment is negligible in , i.e.,

where ε is a negligible function () in λ, , , , and .

5. Anonymity

In this section, we demonstrate how we can model different aspects of anonymity of a currency scheme, in terms of the proposed framework. First, we formulate a parametric game to capture different attacker scenarios, each of which represents a different aspect of anonymity. Then, we provide a group of definitions for several anonymity properties stemming from the fundamental concept of indistinguishability. The term indistinguishability means that it is not possible to distinguish between two known entities in a given situation, e.g., inability to distinguish the sender of a transaction from two possible sender addresses.

We also define a weaker notion of anonymity, unlinkability, which is similar to indistinguishability, except the two entities to choose between are not known to the attacker explicitly, but rather by their history in previous transactions. For example, value unlinkability refers to the inability to decide which of two transactions has the same value as a transaction of interest.

We define these anonymity notions around a set of entities in a typical currency scheme. These entities can be categorized as topological and non-topological where topological entities directly correspond to entities in the transaction graph of the scheme. Senders and recipients form the topological category whereas value and other relevant metadata are categorized as non-topological entities, without having a direct relationship to the transaction graph. We parameterize different scenarios where an attacker can manipulate these entities at various levels.

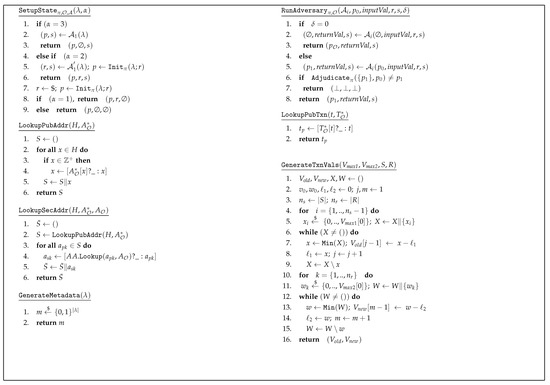

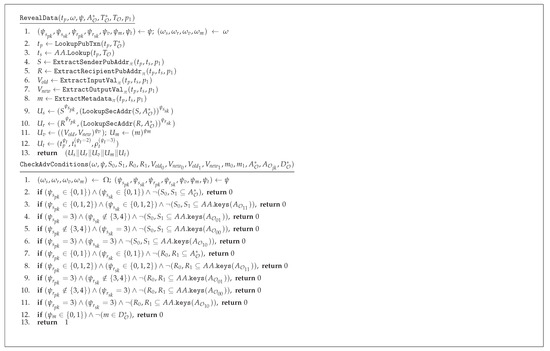

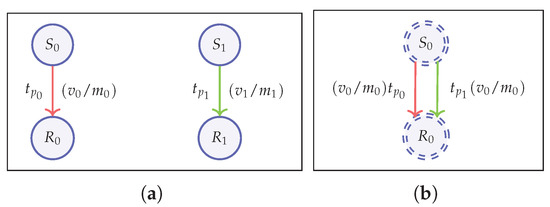

5.1. Anonymity Game

In order to facilitate the execution of the Anonymity game in a more transparent manner, we define a few additional helper functions to check the adversarial conditions of inputs at the start of the game () and to reveal data to the adversary at the end () based on the parameter (Figure 4). Note that for a particular security notion, is constant. Moreover, we also introduce another variable, , to represent test variable/s. We define with each to indicate which entity (sender/recipient/value/metadata) is being tested in a given instance of the game, based on which the transaction data are varied. The adversarial inputs to the game are crafted based on . We now define a common game to capture all possible attacker scenarios in this setting. Figure 5 illustrates the game.

Figure 4.

Additional helper functions for the Anonymity game.

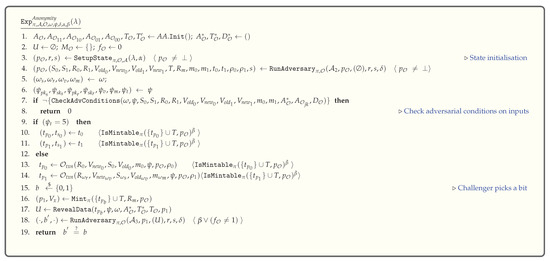

Figure 5.

Anonymity game.

Execution of the Game

The game is executed as follows. The state initialization takes place at the beginning of the execution of the game based on (line 3). The game continues if the returned state is valid. Here, we use ‘’ notation to check this condition. In this notation, if the condition inside the brackets is false, then the game terminates and the adversary loses the game. In this case, if the state is valid, the adversary provides a set of data (to be used in creating transactions, minting, etc.) to the challenger, based on the values of parameters with respect to senders, recipients, values, and metadata. These data include two sets of senders , , recipients , , input/output values , , miners’ addresses , metadata , , a set of transactions T (to be minted), two additional transactions , , two sets of randomness of coins , , together with the current state (line 4). If sender/recipient addresses are hidden, respective outputs should be handles to those hidden addresses created by the oracle, i.e., , , , . The adversary can make corresponding oracle calls to create hidden addresses, and opaque handles to those addresses are given in return. In addition, if transaction values are hidden (i.e., ), then the adversary provides maximum values for respective input and output values (through , ), and the oracle chooses appropriate transaction values accordingly. If , then adversary returns a handle for hidden metadata. The transactions and represent two transactions created by the adversary when . For other values of , these will remain null. The inputs and provide the randomness (of coins) required to create the transactions when , or will be empty, otherwise. According to the values of , the challenger checks whether the values returned by the adversary meet the expected criteria (through the function) and terminates the game if any of the inputs are invalid (line 7). Upon submission of valid inputs, the adversary continues to evolve the current state through appropriate oracle queries.

Next, the challenger checks whether , in which case the adversary produces the required transactions (which will be considered as and ). Otherwise, the challenger creates a transaction , using the input values through the oracle as given in step 13. Based on the entity/entities being tested as defined by , a second transaction is also created as appropriate (line 14). If the transactions are not mintable and the parameter (i.e., failed mint operations are not allowed), then the game is terminated and the adversary loses the game. We use the notation “” to represent this condition. In this case, when , , and the game continues if . When , , and thus always and hence the game proceeds.

Subsequently, the challenger picks a bit b and chooses to mint together with the list of transactions T returned by the adversary (line 15). Next, the challenger calls the function to prepare the information that needs to be revealed to the adversary based on , and this information is then passed to the adversary. At this point, the adversary is not allowed to create any further transactions involving the revealed addresses. Then, he/she makes a guess () for the bit b, based on the revealed data U, minted state , and the adversarial state s. The challenger checks whether the guess is correct, subject to the condition . The adversary wins the game if his/her guess is correct.

Unsurprisingly, there are over 600,000 different combinations of , , , and alone, resulting in different attacker scenarios, which reveal the atomicity of anonymity in a currency system. This game helps one to assess which combinations are satisfied by a given currency scheme, by proving that the attacker has negligible advantage of winning the game. In order to simplify this task, in the next section, we come up with a set of anonymity notions which can be linked to the terminology discussed in the literature.

5.2. Notions of Anonymity

As previously mentioned, different combinations of the parameters in the Anonymity Game yields a large number of unique scenarios with respect to anonymity. While some notions may not result in apprehensible real-world scenarios, others may assist in assessing different levels in achievable anonymity. In this section, we identify a set of some useful anonymity notions with respect to indistinguishability (IND) and unlinkability (ULK) of entities, senders (S), recipients (R), value (V), and metadata (M) in a currency scheme.

We define each notion in terms of a unique adversary, based on the adversary’s goal, knowledge and power as GOAL-KNOWL-POWER, which is also represented as a unique parameter vector − − . The strongest adversary is modeled with the highest power (to manipulate the state initialization and the state, and to make minting to fail) and the maximum knowledge (full knowledge of secret keys of senders/recipients, values, and metadata), which we name as a FULL-FULL adversary. The weakest adversary has no power and no knowledge of transaction data, hence we name as a NIL-NIL adversary. Other intermediate adversaries are named accordingly to emphasize the capabilities in power and knowledge specific to a given setting. Therefore, the highest level of anonymity modeled by the game is the notion ALL-IND-FULL-FULL and the weakest is the notion of NIL-IND-NIL-NIL. Accordingly, Table 7 lists some useful anonymity notions and their corresponding parameter vectors.

Table 7.

Some useful anonymity notions.

5.2.1. Topological Entities

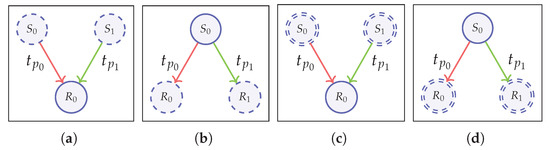

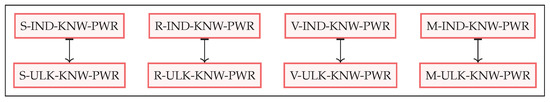

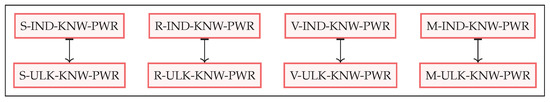

As already mentioned, the identification of topological entities such as senders and recipients participating in a transaction can directly contribute towards constructing the corresponding relationships among those entities. As a result, one can trace the flow of transactions of a particular entity, affecting the level of anonymity. Several studies have been conducted in this regard, especially in the case of Bitcoin, where a transaction graph could be built using publicly available data related to senders and recipients [20]. As such, topological entities play a vital role in the achievable level of anonymity of a currency scheme. Therein, we define a set of useful anonymity properties around these entities in this section (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Topological anonymity notions. (Dashed outline: addresses with hidden secret keys, double-dashed outline: addresses with hidden public/private keys, Solid outline: both keys known). (a) Sender Indistinguishability (S-IND); (b) Recipient Indistinguishability (R-IND); (c) Sender Unlinkability (S-ULK); (d) Recipient Unlinkability (R-ULK).

Sender Indistinguishability (S-IND)

We define this property to represent a case where given two possible senders and a transaction, it is not possible to distinguish the correct sender. Figure 6a illustrates this scenario. In the anonymity game, only the public keys of the senders will be known to the adversary with and (PUBS knowledge) with same transaction values and other metadata, and the challenger will create two transactions and with same value and metadata if (otherwise, the adversary provides the transactions). Based on the chosen bit b, the challenger mints the transaction and the adversary gets to see the data related to the minted transaction, based on , and has to guess the challenger’s choice. The knowledge of recipient addresses can vary based on and .

We can see that the game represents the strongest attacker scenario when the recipient addresses are fully controlled by the adversary in a setting with an adversarial hidden state initialization and the ability to manipulate the state, as well as with the highest knowledge of the transaction (i.e., ). However, having = 1 enables the adversary to craft messages in a manner so that failed mint operations can be used to learn about account balances, etc., thus revealing the transaction graph, which will be trivial and thus we consider an adversary with ACTIVE power (i.e., ). Accordingly, the strongest notion of this property is S-IND-PUBS-ACTIVE, which is represented by “ − − ()” in the Anonymity game with the following formal definition.

Definition 4 (S-IND-PUBS-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion S-IND-PUBS-ACTIVE with respect to Sender Indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameter vector − − () is negligible, i.e.,

Sender Unlinkability (S-ULK)

The notion of sender unlinkability is defined to be the property that it is not possible to link a transaction with its corresponding sender in a given setting. As Figure 6c illustrates, the adversary has to guess the correct transaction as with S-IND scenario, but without knowing both public/private keys of the senders, i.e., Senders in this case are hidden with . The strongest notion in this sense is given by S-ULK-NILS-ACTIVE with the parameter vector “ − − ()” and the corresponding formal definition is as follows.

Definition 5 (S-ULK-NILS-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion S-ULK-NILS-ACTIVE with respect to Sender Unlinkability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible, i.e.,

Recipient Indistinguishability (R-IND)

This notion is similar to sender indistinguishability, except with recipient addresses. Therefore, it is defined to be one’s inability to distinguish the correct recipient out of two given recipients in a given situation. As shown in the Figure 6b, public keys of the recipients () are known and the senders could be hidden or known as per the parameters and . The two transactions and both carry the same sender, values, and metadata, yet have two different recipients. The adversary needs to guess which transaction out of and was minted. The strongest adversarial scenario in this case is R-IND-PUBR-ACTIVE, denoted as “ − − ()”. We define the notion formally as below.

Definition 6 (R-IND-PUBR-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion R-IND-PUBR-ACTIVE with respect to Recipient Indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − − () is negligible, i.e.,

Recipient Unlinkability (R-ULK)

This property is referred to as the inability to link a transaction to the correct recipient. Figure 6d shows the basic setup for this game where the adversary needs to guess the correct transaction out of the two options and , without any knowledge about the corresponding recipients, i.e., ,. The strongest notion in this setting is represented as R-ULK-NILR-ACTIVE given by the vector “ − − ()” and the formal definition is given below.

Definition 7 (R-ULK-NILR-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion R-ULK-NILR-ACTIVE with respect to Recipient Unlinkability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible.

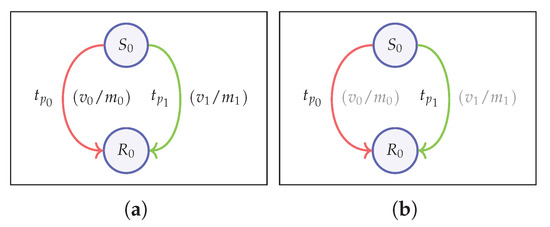

5.2.2. Non-Topological Entities

As opposed to topological entities, non-topological entities such as value and metadata in a currency scheme do not directly affect the structure of the transaction graph. However, if made public, these entities could also hinder the privacy of users. Therefore, these entities can also be regarded as equally important in determining the level of anonymity in a currency scheme. In this section, we provide formal definitions for major anonymity notions involving non-topological entities: value and metadata (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Non-topological Anonymity notions. (a) Value/Metadata indistinguishability. (b) Value/Metadata unlinkability (hidden values/metadata).

Value Indistinguishability (V-IND)

The notion of indistinguishability with respect to transaction values refers to the fact that it is impossible to distinguish the correct value from two given values for a given transaction. In the game, the challenger creates two transactions, and , with two different values, and , while having other entities the same (Figure 7a). In this case, the adversary knows what the two values are and other entities can vary according to their values. The challenger then picks a bit b and mints the transaction and the adversary has to guess which transaction it is. We represent the strongest adversary as PUBSR-ACTIVE as the knowledge of secret keys would leak information about the value. Therefore, the strongest notion in this scenario is given by V-IND-PUBSR-ACTIVE, which is represented by the vector “ − − ()” with the following formal definition.

Definition 8 (V-IND-PUBSR-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy V-IND-PUBSR-ACTIVE with respect to Value Indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible, i.e.,

Value Unlinkability (V-ULK)

We define the property of unlinkability related to transaction value as the inability to correctly identify value of the minted transaction from two possible hidden values. In order to realize this scenario, failed minting operations have to be allowed in the game with the parameter set to 1, as it would be impossible for the adversary to win the game otherwise. As , the adversary gives maximum values for and values from which the challenger generates corresponding values required for the transaction using the helper function (Figure 3). Further, as in the case of V-IND, we restrict the knowledge of secret keys of senders/recipients as otherwise the transaction is trivial. As shown in Figure 7b, in this context the challenger creates two transactions and with hidden transaction values and , respectively. The challenger then picks a bit b and mints the transaction and the adversary makes a guess to identify the correct scenario. Accordingly, we have “ − − (” as the combination of parameters required to achieve the strongest level of anonymity notion V-ULK-PUBSR-NILV-FULL in this sense and the corresponding definition is as follows.

Definition 9 (V-ULK-PUBSR-NILV-FULL).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion V-ULK-PUBSR-NILV-FULL with respect to Value Unlinkability against an adversary under a hidden adversarial initialisation, if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − − () is negligible, i.e.,

Metadata Indistinguishability (M-IND)

Other transaction-related data such as scripts, IP addresses, etc. also pose a risk to anonymity as they can be linked to addresses or transactions in many different ways. Although such metadata can be specific to a given implementation, it might be useful in modeling the effects imposed by the other layers of implementations such as the consensus scheme. Therefore, in this case, we discuss metadata in general without linking to any specific data, for the completeness of this work.

In this context, we define Metadata Indistinguishability to represent the scenario where it is not possible to correctly identify the metadata corresponding to a given transaction, between two given possibilities. Similar to the value indistinguishability scenario, the challenger creates two transactions with different metadata values (already known to the adversary) and mints only one transaction leaving the adversary make a guess as to what it is. The following vector represents the strongest scenario as “ − − ()” as per the notion M-IND-PUBM-ACTIVE and it is formally defined below.

Definition 10 (M-IND-PUB-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion M-IND-PUB-ACTIVE with respect to Metadata Indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − − () is negligible, i.e.,

Metadata Unlinkability (M-ULK)

We define the property of unlinkability of metadata with a close analogy to value unlinkability, i.e., given a transaction, it is not possible to correctly identify the metadata from two given hidden metadata values. Here, we use the helper function to generate the data required for the game (Figure 3). Accordingly, we have the corresponding notion M-ULK-NILM-ACTIVE parameterized by, “ − − ()” representing the strongest case in this sense. The formal definition follows.

Definition 11 (M-ULK-NILM-ACTIVE).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion M-ULK-NILM-ACTIVE with respect to Metadata Unlinkability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible, i.e.,

5.2.3. Other Useful Anonymity Notions

Further to above notions, we also formally define the strongest and weakest anonymity notions modeled in this framework as they are useful in benchmarking the anonymity landscape.

Strongest Anonymity (ALL-IND)

In this setting, the game models two senders and two recipients. The challenger creates two transactions and as before, but each transaction is created using distinct set of data, i.e., different sender, recipient, value, and metadata (Figure 8a). The strongest adversary in this scenario has the FULL knowledge and FULL power given by ALL-IND-FULL-FULL notion and parameterized by the vector − , − (). This setting models the highest level of anonymity achievable by a currency scheme and can be considered as “absolute fungibility”. We provide the following formal definition in this connection.

Figure 8.

Strongest and weakest anonymity games. (a) ALL-IND game; (b) NILL-IND game.

Definition 12 (ALL-IND-FULL-FULL).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion ALL-IND-FULL-FULL with respect to indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible, i.e.,

Weakest Anonymity (NIL-IND)

Here, we consider the weakest adversary that can be modeled in our game. In this case, the game produces two identical transactions as opposed to the strongest scenario above (Figure 8b). These transactions differ only in their randomness and the adversary has to identify the correct transaction. Therefore, the weakest adversary in this case is a NIL-NIL adversary with no knowledge nor power, which is a passive adversary. This means that even = 0, meaning that the scheme has a hidden private state, which however may not be the case for most cryptocurrency schemes. Yet, we provide the following formalization for comparison.

Definition 13 (NIL-IND-NIL-NIL).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion NIL-IND-NIL-NIL with respect to indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible, i.e.,

As many cryptocurrency schemes have public states, we can see that at the very least, the adversary can view the state, meaning that we can set = 1 in our model for most schemes. This will model an adversary with VIEW power with other parameters being zero. Therefore, we define a slightly less weaker notion in this sense, which can be useful to model anonymity in some real world constructions.

Definition 14 (NIL-IND-NIL-VIEW).

A currency scheme Π is said to satisfy the anonymity notion NIL-IND-NIL-VIEW with respect to indistinguishability against an adversary , if ’s advantage of winning the Anonymity game defined by the parameters − , − () is negligible, i.e.,

5.2.4. Representation of Anonymity Notions

In order to clearly represent above anonymity notions, we construct graphical illustrations as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10. These diagrams are useful in comparing anonymity landscape across different implementations while illustrating the complex multidimensional diversity of adversarial parameters.

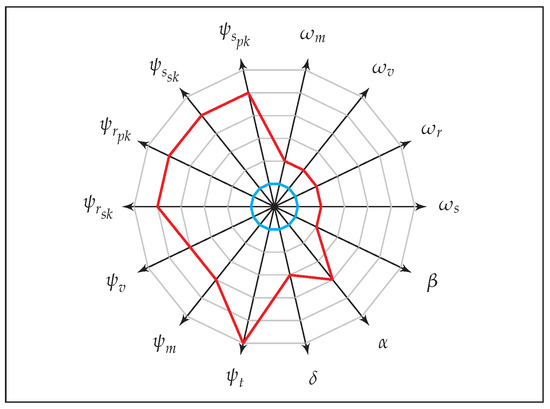

Figure 9.

Strongest anonymity notion: ALL-IND-FULL-FULL (red). Weakest notion: NIL-IND-NIL-NIL (cyan).

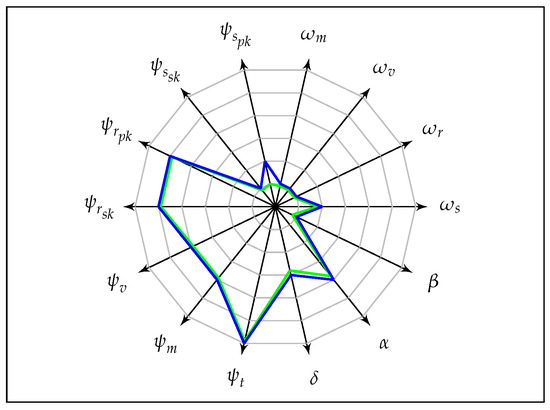

Figure 10.

Anonymity notions S-IND-PUBS-ACTIVE (green) and S-ULK-NILS-ACTIVE (blue).

Figure 9 represents a comparison between the strongest anonymity notion ALL-IND-FULL-FULL against the weakest notion NIL-IND-NIL-NIL in our anonymity game. All other notions lay within the area bounded by these two notions. The larger the area covered by the graph of a given notion, the stronger is the level of anonymity. This is evident from the Figure 10, which represents two more anonymity notions related to S-IND and S-ULK corresponding to Definitions 4 and 5, and shows that S-IND is stronger than S-ULK.

5.3. Theorems

As is apparent from the definitions presented in the previous section, we can utilize the Anonymity game to realize a multitude of potential different attacker scenarios. Identifying the relationships among these is a worthwhile exercise in order to discern the meaningful aspects of anonymity captured by them.

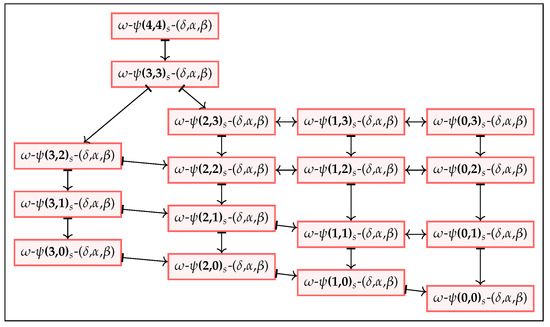

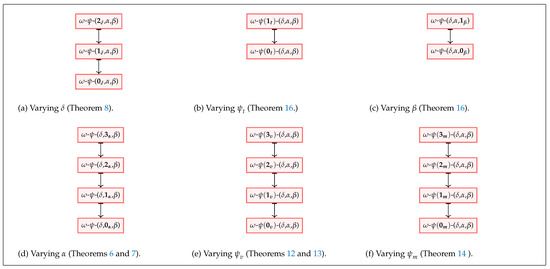

Note that as we vary different security parameters in our model, their correlations result in a non-trivial lattice form as depicted in Figure 11 and Figure 12. These relations are interpreted as implications, equivalences, and separations. The arrow “↦” represents an implication in the direction of the arrow and a separation in the opposite direction, whereas the double arrow “↔” shows an equivalence relation. In order to formalize these relationships, we define a set of theorems that will simplify the process of assessing the anonymity of a currency scheme and we present the same below. Relevant proofs of these theorems are available in Appendix C.

Figure 11.

Relationship of anonymity notions for different sender addresses .

Figure 12.

Relationships among notions based on , , , , , and .

Theorem 1.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , , , and β, the notion resulting from increasing the value of while holding others is strictly stronger than the former for the following scenarios.

- i.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in , and ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in and ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- iv.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- v.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 11).

Theorem 2.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , , , and β, the notion resulting from increasing the value of while holding others is strictly stronger than the former for the following scenarios:

- i.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in , and ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in and ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in , and ,i.e.,

- iv.

- given that Π is secure in , Π is also secure in , and ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 11).

Theorem 3.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , , and β, the resulting notion from increasing the value of while holding others fixed, is equivalent to the former when under the following scenarios:

- i.

- given that Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in , and vice versa.,i.e.,

- ii.

- given that Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in and , and vice versa,i.e.,

- iii.

- given that Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in and , and vice versa,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 11).

Theorem 4.

For a currency scheme Π for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , , and β (with ), the notion resulting from decreasing the value of while holding others is not necessarily stronger than the former for the following scenarios:

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

- iv.

- v.

where , , and (Figure 11).

Theorem 5.

For a currency scheme Π for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , , and β (with ), the notion resulting from decreasing the value of while holding others is not necessarily stronger than the former for the following scenarios:

- i.

- ii.

- iii.

where , , and (Figure 11).

Note that the Theorems 1–4 also hold for recipient addresses in the same manner.

Theorem 6.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, ψ, and β, if α is decreased while holding the others, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion for the following scenarios:

- i.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 12d).

Theorem 7.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, ψ, and β (with ), if α is increased while holding the others, the system is necessarily secure in the resulting notion for the following scenarios:

- i.

- Given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- Given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- iii.

- Given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 12d).

Theorem 8.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, α, ψ, and β, if δ is decreased while holding the others, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion for the following scenarios:

- i.

- given Π is secure in then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given Π is secure in then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 12a).

Theorem 9.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, α, ψ, and β (with ), if δ is increased while holding the others, the resulting notion is not necessarily stronger than the former notion for the following scenarios:

- i.

- given that two currency schemes and exists such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given that two currency schemes and exists such that is secure in and is not secure in , there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 12a).

Theorem 10.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, α, and ψ, if β is decreased while holding the others, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion for the following scenarios:

- i.

- given Π is secure in then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

where , , and (Figure 12a).

Theorem 11.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, α, and ψ, if β is decreased while holding the others, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion for the following scenarios:

- i.

- given that Π is secure in then Π is not necessarily secure in ,i.e.,

where , , and (Figure 12a).

Theorem 12.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , and β, when the value of is decreased while holding others fixed, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion under the following scenarios:

- i.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e., →

- ii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e., →

- iii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e., →

where , and (Figure 12e).

Theorem 13.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , and β (with ), the resulting notion from increasing the value of while holding others fixed, the scheme is not necessarily secure in the resulting notion under the following scenarios:

- i.

- given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

where , , and (Figure 12e).

Theorem 14.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , and β, when the value of is decreased while holding others fixed, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion under the following scenarios:

- i.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

where , and (Figure 12f).

Theorem 15.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , and β (with ), the resulting notion from increasing the value of while holding others fixed, the scheme is not necessarily secure in the resulting notion under the following scenarios:

- i.

- given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given that two currency schemes and exist such that is secure in and is not secure in , then there exists a currency scheme Π which is secure in but not secure in ,i.e.,

where , , and (Figure 12f).

Theorem 16.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , and β, when the value of is decreased while holding others fixed, the former notion is strictly stronger than the resulting notion under the following scenarios:

- i.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- ii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- iii.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- iv.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

- v.

- given Π is secure in , then Π is also secure in ,i.e.,

where , , and (Figure 12b).

Theorem 17.

For a currency scheme Π and for a given combination of ω, δ, α, , , , and β the resulting notion from increasing the value of while holding others fixed, the scheme is not necessarily secure in the resulting notion under the following scenarios:

- i.

- Given that there exists a currency scheme which is secure in , it does not necessarily imply that is secure in ,i.e., is secure in .

- ii.

- Given that there exists a currency scheme which is secure in , it does not necessarily imply that is secure in ,i.e., is secure in .

- iii.

- Given that there exists a currency scheme which is secure in , it does not necessarily imply that is secure in ,i.e., is secure in .

- iv.

- Given that there exists a currency scheme which is secure in , it does not necessarily imply that is secure in ,i.e., is secure in

- v.

- Given that there exists a currency scheme which is secure in , it does not necessarily imply that is secure in ,i.e., is secure in

where , , , and (Figure 12c).

Note that in some cases, the separations are not known to hold for all values of the unspecified parameters. Based on the above theorems, we also define the following corollaries.

Corollary 1

(Absolute Fungibility (ALL-IND-FULL-FULL)).Given that a currency scheme Π is secure in the strongest anonymity notion (i.e., secure against the strongest possible adversary), then Π is also secure in any other notion (any other adversary), i.e., where , and (Figure 11).

Proof.

Corollary 2

(IND → ULK).For a currency scheme Π,

- i.

- given Π is secure in S-IND-KNW-PWR for a given adversarial knowledge KNW of recipients, value and metadata, and given adversarial power PWR, then Π is also secure in S-ULK-KNW-PWR,i.e., S-IND-KNW-PWR → S-ULK-KNW-PWR;

- ii.

- given Π is secure in R-IND-KNW-PWR for a given adversarial knowledge KNW of senders, value and metadata, and given adversarial power PWR, then Π is also secure in R-ULK-KNW-PWR,i.e., R-IND-KNW-PWR → R-ULK-KNW-PWR;

- iii.

- given Π is secure in V-IND-KNW-PWR for a given adversarial knowledge KNW of senders, recipients and metadata, and given adversarial power PWR, then Π is also secure in V-ULK-KNW-PWR,i.e., V-IND-KNW-PWR → V-ULK-KNW-PWR; and

- iv.

- given Π is secure in M-IND-KNW-PWR for a given adversarial knowledge KNW of senders, recipients and value, and given adversarial power PWR, then Π is also secure in M-ULK-KNW-PWR,i.e., M-IND-KNW-PWR → M-ULK-KNW-PWR

Proof.

(sketch) (Part i) From the definitions of S-IND (Definition 4) and S-ULK (Definition 5), the difference between the two notions is that in S-IND and it is in S-ULK. Then, from Theorem 1, it follows that and hence the implication follows (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Relations between indistinguishability and unlinkability (Corollary 2).

(Part ii) Similarly, it follows from Theorem 1 with respect to recipients.

(Part iii) Follows from Theorem 12.

(Part iv) Follows from Theorem 14. □

Conversely, the weakest adversary is represented by the notion NIL-IND-NIL-NIL represented by the vector − − with all entities hidden (Definition 13). Note that this notion is trivial in that no adversary can ever win the corresponding game as the transactions and are, aside from randomness, identical.

6. Discussion

Our objective in this work was to find a solution to our research question, i.e., to formulate a method to achieve a fine-grained systematization of anonymity modeling suitable for decentralized systems such as modern cryptocurrencies. To this effect, we have developed a comprehensive framework which depicts the generic functionality of a cryptocurrency scheme, irrespective of the underlying implementation. We have established the soundness of our model while ensuring the functional correctness and security against a wide range of adversaries. Through this model, we have constructed a unified means of analyzing the true level of anonymity achieved by any fully decentralized cryptocurrency system in a qualitative manner.

Our proposed anonymity model is centered around the idea of indistinguishability and it is elaborated around a group of entities related to cryptocurrency transactions, e.g., senders, recipients, values, and metadata. To this effect, we defined a comprehensive adversarial model encompassing a wide range of capabilities including knowledge and power. Adversarial knowledge is determined based on a range of access levels to the knowledge of secret/public keys of senders/recipients, transaction values, metadata, and transaction records. Power is defined based on different combinations of state initialization methods, ability to manipulate the state, and to cause minting to fail. These capabilities collectively represent an exhaustive adversarial model, which is capable of modeling anonymity at a much granular level, resulting in a vast number of different notions per each test case (defined by ). While some notions may not carry a meaningful realization in a real currency scheme, a majority leads to a multitude of attacker scenarios, which may not have been thought possible otherwise. One may wonder why we need such granularity in modeling anonymity in the context of cryptocurrencies, yet our model shows how a minute change such as varying one value in a single variable in the Anonymity game, could drastically affect the level of anonymity of a cryptocurrency. Thus, we have been able to achieve a fine-grained model as expected.

Building upon this model, we have provided formal definitions for a subset of anonymity notions that demonstrate baseline anonymity notions in indistinguishability, which is the fundamental property of anonymity. Inability to distinguish between two probable (known) entities related to a minted transaction under various adversarial settings was considered as the basis for these notions. Moreover, we also defined unlinkability, a weaker notion of indistinguishability, in order to define an intermediary level of anonymity. In this case, we considered the indistinguishability between two entities that are unknown to the adversary in a given scenario. However, even without formal definitions, other notions also play a significant role in performing a rigorous analysis of anonymity aspects of cryptocurrencies. As such, the anonymity notions resulting from this framework provide a universal systematization of anonymity across different implementations.