The Prudential Rationality of Risking Traumatic Brain Injury in Dangerous Sport: A Parfitian Defense

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Parfit’s Argument and Its Application to Dangerous Sport

- Psychological connectedness and continuity are the grounds for caring about one’s future selves.

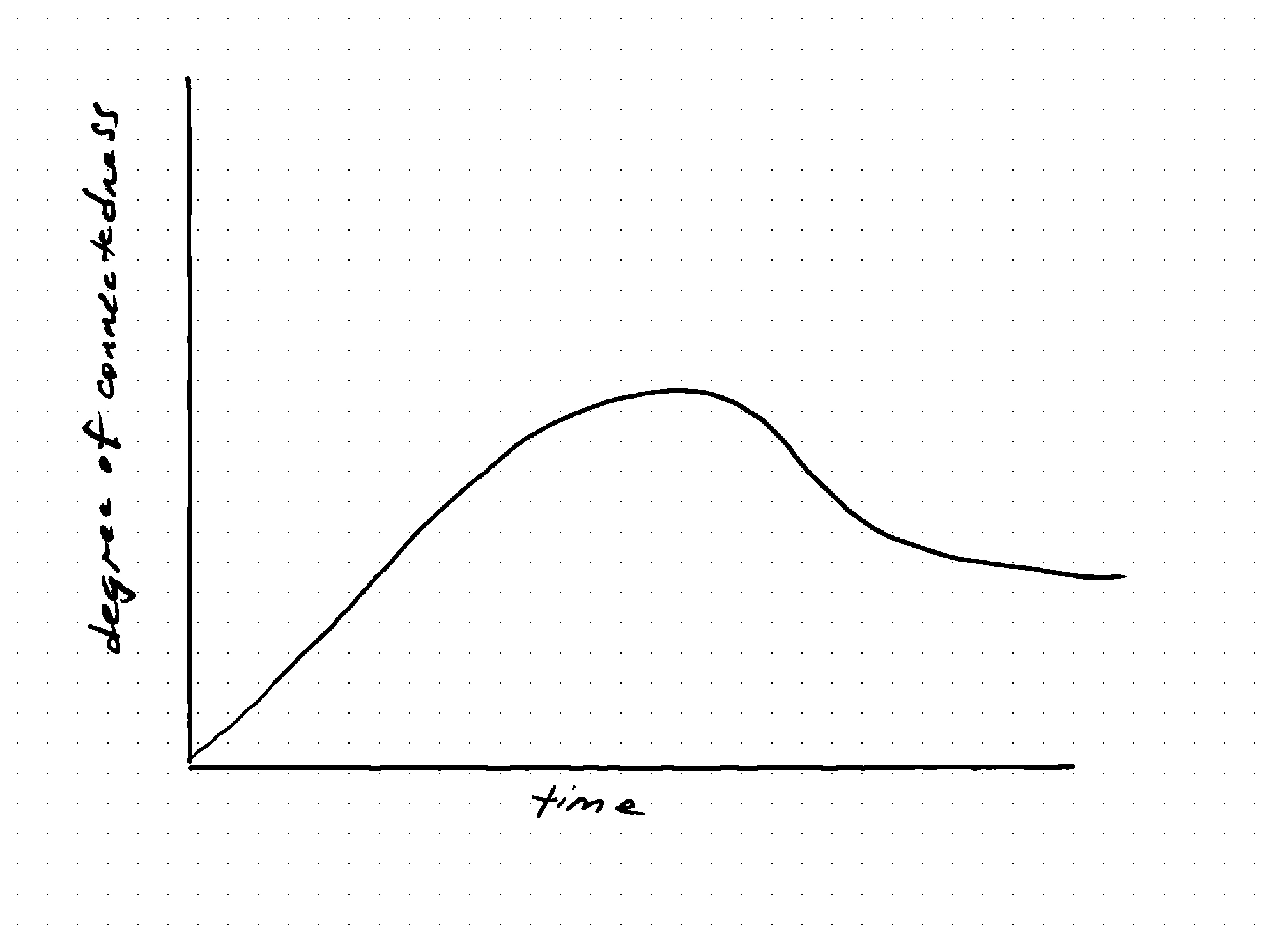

- Psychological connectedness is a matter of degree, and connectedness to one’s present self diminishes over time (distant future selves are connected to one’s present self to a much lower degree than near future selves).

- One’s grounds for caring about one’s distant future selves are comparatively weak, and therefore it is rationally permissible to care less about them than one’s near future selves.

- P1

- Because it is rationally permissible for an athlete to discount her distant-future well-being, it is rationally permissible for her to take certain risks that may diminish that well-being—provided the level of risk is (inversely) proportional to the degree of connectedness between present and future selves.7

- P2

- The risk of TBI in DS is, for many athletes, within the range of acceptable risk.

- P3

- Risking TBI in DS can be rational.8 (from P1 and P2)

3. Is Future Discounting Sufficient to Rationalize DS?

3.1. “Arc of a Life” Considerations

3.2. Deference to Individuals’ Risk Attitudes

[T]here are actually three psychological components in preference-formation and decision-making: how much an individual values consequences (utilities), how likely an individual thinks various states of the world are to obtain (probabilities), and the extent to which an individual is willing to trade off value in the worst-case scenarios against value in the best-case scenarios (the risk function). There are two different ways to think about the risk function: as a measure of distributive justice among one’s “future possible selves”—how to trade off the interests of the best-off possible self against the interests of the worst-off possible self—and as a measure of how one trades off the virtue of prudence against the virtue of venturesomeness.12 ([14], 91)

3.3. Duties to Future Selves

3.3.1. Schofield’s Theory of Self-Directed Duty and Hypothetical Retrospection

[I]n order to be decision-guiding, hypothetical retrospection has to refer to the decision that one should have made given the information (actually) available at the time of the decision, not the information (hypothetically) available at the time of the retrospection. The decision-relevant moral argument is not of the form “Given what I now know I should then have….”, but rather “Given what I then knew, I should then have…”. The purpose of hypothetical retrospection is to ensure serious consideration of possible future developments and what can be learnt from them, not to counterfactually reduce the uncertainty under which the decision must be taken.…

Hypothetical retrospection aims at ensuring that whatever happens, the decision one makes will be morally acceptable (permissible) from the perspective of actual retrospection. To accomplish this, the decision has to be acceptable from each viewpoint of hypothetical retrospection. ([20], 148–149)

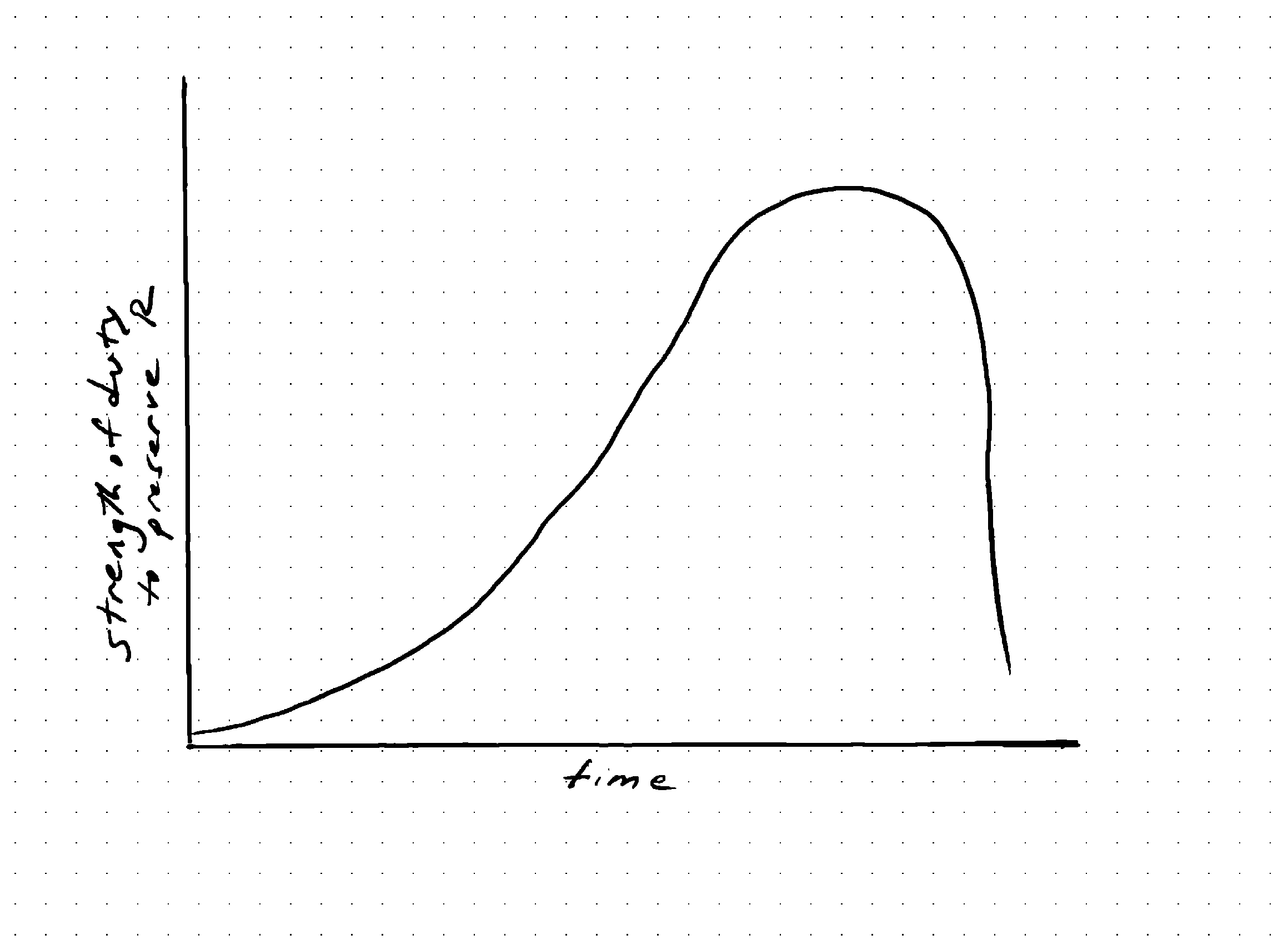

3.3.2. Against Duties to Distant Future Selves: Diminishing Bonds of Concern

3.3.3. Against Duties to Distant Future Selves: The Nonidentity Problem

3.4. The Duty to Protect One’s Autonomy

3.4.1. Synchronic vs. Diachronic Duties to Self

3.4.2. Consensual Domination and Risk to Future Autonomy

Given what we know, and are learning, about CTE, choosing to play football is analogous to choosing to be sold into slavery, since choosing football means choosing the likely brain damage that makes later autonomous choice equally impossible. ([39], 271)

3.4.3. Autonomy as Demand

4. Does the Parfitian Defense Prove Too Much?

4.1. On Rationalizing Generally Reckless Behavior

Good-Value Link: for any object, event, state, etc., and agent x, is good for x only if and (at least in part) because is valued, under conditions c, by x. ([23], 80)

4.2. Exploitability and Discounting

[Non-stationarity] makes [Al’s] present evaluation of a future delay depend not only on the futurity and length of that delay but also on what date it is now. More specifically, her rate of time-preference at any time is a function of the date t—typically a declining function, so that the longer she lives the more patient she gets. But why should her past longevity have normative bearing on her present concern for her future self? Why should it be a demand of rationality that (for instance) Alice on 1 January 2016 cares less about her consumption on 10 January than Alice on 1 June 2017 cares about her consumption on 10 June 2017? ([7], 253)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | I focus on dangerous sports that involve a significant risk of loss of, or serious impairment to, one’s rational capacities, but not necessarily a high risk of loss of one’s life. |

| 2 | Note this is only one way to justify the claim that it is rational to pursue DS. Another way, which does not appeal to discounting, is suggested by Lopez Frias & McNamee ([5], 270–271): It may be rational for athletes to risk giving up the possibility of employing some future rational capabilities (due to the prospect of brain injury) in order to enjoy more pleasurable and more fulfilling lives in the present, if this is judged to be the best chance of realizing the most good in life. Lopez Frias & McNamee note, referencing [6], that this is not a pure time preference, but rather “a rational estimation of pains and pleasure from the present point of view with a proper regard for the future insofar as one may estimate it.” ([5], 272). |

| 3 | Although it is worth noting that uncertainty about the extent of the risks associated with TBI is clearly relevant to the issue, and that the available empirical evidence of a causal relationship between TBI in DS and later-in-life health conditions is far from conclusive—in large part due to the presence of a range of confounding factors (lifestyle, genetics, medical conditions, drug and alcohol use, etc.). See [8]. |

| 4 | Even if athletes lack knowledge of this proposition, it is very likely that they will have strong justification for believing it, and whatever provides such justification will make it rational, in the absence of countervailing reasons, for them to discount their distant futures. |

| 5 | Parfit acknowledges that there are “many ways to count” the number of direct connections, and that some kinds of connection are more important for psychological continuity than others ([3], Ch. 10, n.6). He does not offer a criterion for determining what makes certain direct connections more important than others. |

| 6 | Note that this quote makes it clear that Parfit means it is rationally permissible to care less, not that this is rationally required. More precisely, I will follow Frederick et al. [9] in reading Parfit as endorsing the claim that you are not rationally required to care about your future welfare to a degree that exceeds the degree of connectedness that obtains between present and future selves. The conclusion of the Parfitian defense should be understood accordingly. |

| 7 | I will not attempt to spell out the relevant proportionality principle that’s applied here, except to say that it implies that there is a certain range of risky behavior that is rationally permissible. |

| 8 | A note about the scope of the Parfitian defense. It is not intended to apply to all classes of athletes but only those who understand well enough the risks involved and how their values bear on those risks. (See §3.2 for discussion of risk functions. It may also be helpful to compare the notions of informed consent and decisional capacity in bioethics.) What constitutes understanding “well enough” is open to debate, but I will assume that there are clear cases anyway that all parties in the debate can agree on. In particular, the argument does not apply to athletes with substantial cognitive limitations, including young children, where such limitations render them incapable of making an informed choice of whether to participate in DS. These cases are important and worthy of consideration, but I must set them aside here. (Thanks to a reviewer for noting this limitation of the main argument.) |

| 9 | As we will eventually see (§4.1), one of these objections (“reckless behavior”) shows that there is a further “prudential value” condition on rational risky choices, which is needed to rule out certain cases of risk-taking as prudentially irrational. §4.1 shows that such a condition is plausible, hence that this proviso to P1 is warranted. |

| 10 | For an account of which preferences are relevant to well-being, see [13]. |

| 11 | —provided their risk attitudes are reasonable, that is. Buchak acknowledges that there are some constraints on the risk function, including that it must not be decreasing in probability (one must not prefer a worse chance at a good consequence over a better one). |

| 12 | I do not interpret Buchak as suggesting that it is imprudent to make such tradeoffs. The fact that X is less prudent than Y does not imply that X is not prudentially rational. |

| 13 | Of course, the presence of such a threat is a matter of degree, and both what constitutes a significant threat and what constitutes severely diminished connectedness is vague, and so subject to dispute. |

| 14 | Note that this is not to say that the amoralist is necessarily prudentially irrational. As David Shoemaker notes ([16]), the amoralist might be motivated to act in accordance with many of the moral judgments he makes, not because he is concerned to do the right thing but because he seeks to justify his actions to his future selves. |

| 15 | Schofield does acknowledge that there’s an important disanalogy between the interpersonal and interpersonal cases (Ch. 3, §6). In the case of duties to self, the second-personal posture (from which demands are made) is taken between two distinct temporal perspectives, whereas in the case of duties to others, it is taken between perspectives of metaphysically distinct persons. Nonetheless, he argues, these are both ways of responding to the moral value of a person. It is worth noting that, in Parfit’s view, this disanalogy does not hold—or not to the extent that Schofield suggests—since according to Parfit the occupants of P1 and P2 are not numerically identical persons. |

| 16 | Although, as Kumar ([19], 246) notes, in the interpersonal case, it does not seem unreasonable to regard an action that imposed serious risk on another as having wronged her, regardless of whether anything bad actually happened. I return to this worry below (§3.3.2). |

| 17 | It is fallible, of course, given its reliance on judgments of what is reasonable in hypothetical cases. In some such cases, there may be rational disagreement about whether a demand would be reasonable, and it is possible that in some cases there may simply be no fact of the matter about what would be reasonable. |

| 18 | —and also despite Kant’s view that such duties are paramount. As Schofield notes, Kant writes in his Lectures on Ethics that “So far from [duties to self] being the lowest, they actually take first place, and are the most important of all…. He who violates duties toward himself, throws away his humanity, and is no longer in a position to perform duties to others”. ([21], 22–23) |

| 19 | Dorsey identifies friendship and parent-child relations as examples of such bonds, but he suggests that they obtain in the intrapersonal case as well. Moreover, he notes ([22], 464) that, at least for some individuals, such bonds will be near-term biased (plausibly, because they have a stronger set of interactions and relationships with near-term future selves than far-term future selves). Note in addition that the presence of a connection between selves is not sufficient for there being such a bond; a bond between X and Y requires that there be connectedness of a certain degree. |

| 20 | I do not suggest that there is a sharp line separating positive and negative rights, or that the fulfillment of one is necessarily independent of fulfillment of the other. We should acknowledge that the distinction between positive and negative rights, and duties, is not exhaustive; that neither positive nor negative rights can be adequately protected only by positive duties or only by negative duties; and, moreover, that in some cases the justification for fulfilling a positive right may be as strong, or stronger than, the justification for fulfilling a negative right (cf. [24], Ch. 7). |

| 21 | This may apply to other sorts of psychological connections as well, such as character traits. Consider for instance the trait of compassion. It may be that, as one ages and other psychological connections (as well as physical abilities) begin to erode, there is a point at which preserving this trait becomes much less important than it once was. Indeed, this seems especially plausible in light of recent empirical work in social psychology which casts doubt on the existence of stable, consistent traits that play an important role in causing human behavior (See [25,26,27]). If, contrary to what our standard attributions suggest, people do not generally have “robust” character traits (i.e., traits that are stable and consistent such that they can explain behavior in a wide range of situations. ([26]))—if their behavior is typically due to features of the particular situation in which they find themselves, and is explained by narrower traits and dispositions—then the value of preserving these narrower traits may diminish as one’s agency and one’s opportunities for expressing and being guided by them also diminish. For example, someone might regularly behave kindly and respectfully toward his colleagues, thus meriting the ’local’ evaluation, “good colleague”, and although such behavior is reliable and predictable, his behavior in situations that do not involve routine interactions (e.g., a rare type of emergency situation) may not be. Hence, a “wider” evaluation, e.g., “good friend” or “good person” may not be warranted. However, as the range of situations one regularly finds oneself in narrows, there will be less justification for even local character evaluations. |

| 22 | For instance: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/05/sport/head-injury-suicide-female-athletes-intl-spt-cmd/index.html (accessed on 8 May 2025). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Iverson (2014) notes that the causes of suicide are “complex, multifactorial, and difficult to predict in individual cases”, which warrants caution in interpreting the evidence regarding CTE and suicide. He emphasizes that at the time of publication “there are no cross-sectional, epidemiological or prospective studies showing a relation between concussions or subconcussive blows in contact sports and completed suicide”. ([28], 164) |

| 25 | Maroon et al. report that that in a study of 150 CTE cases, the rate of suicide was much higher than in the general population (11.7% and 4.8%, respectively). However, it is not clear that the presence of CTE is what explains this difference. For one, suicide has been reported more often in less advanced stages of CTE (thus suggesting that it may not be due to progression of CTE). In addition, individuals and families of players who have died by suicide have been disproportionally more likely to participate in CTE brain donation programs ([29]). For further discussion of the empirical evidence and the limitations of various studies, see e.g., [30]. |

| 26 | |

| 27 | In general, the following principle is plausible: if you cannot be aware that by ing you will cause E, and you do not intend to cause E, then you are not, by ing, directly responsible for E. Moreover, if you are not aware (nor should you have been aware) that the likely consequence of your ing is E, then it seems you are not derivatively responsible for E. ([37], 76 (although Sartorio suggests that only a weaker principle of derivative responsibility is plausible, which states a sufficient but not necessary condition for moral responsibility)) The reader might worry how likely it must be that ing brings about E (via a chain of events) in order for the agent to be derivatively responsible for E. While I cannot defend it here, my suggestion is that it must at least be likely enough that E, or E-type events, are reasonably foreseeable, such that the agent conceivably could rationally intend to bring about E. I claim this condition does not obtain in the present case. |

| 28 | Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pressing me on this important issue and helping me to clarify my argument in this section. |

| 29 | Note that the arguments I offer in §3.4 do not depend on the assumption that Parfitian discounting is rational. |

| 30 | Of course, such a duty need not be understood as independent of duties to future selves. It might be held that your duty to protect your rational capacities obtains in virtue of your duties to future selves whose well-being depends on their being protected. However, if you have a duty to protect your rational capacities which is independent of any duties to future selves, then such a duty would seem to hold at any moment at which you possess those capacities. |

| 31 | Sailors and other critics of DS may argue that it is in effect foreseeable, given the number of athletes and former athletes the examination of whose brain tissue has shown evidence of CTE, and that any athlete who thinks otherwise is naive or simply deluded. Sailors points out that there appears to be more certainty regarding occurrence of CTE in football players than previously assumed. In response, Lopez Frias and McNamee ([5], 275–276) note that, according to a recent systemic review of the available evidence, there remains significant uncertainty about the incidence of CTE among athletes, and about the relationship between CTE and sport-related concussion. Addressing the question of how likely one’s participation in DS is to lead to CTE requires further empirical investigation. Arguably, there is currently enough uncertainty about the conditions in which TBI occurs in DS, and about whether it increases the occurrence of certain later-in-life health conditions, that it is not unreasonable for an athlete to withhold judgment about how likely it is that she will eventually suffer such an injury. As such, she need not, in pursuing DS voluntarily, consent to such outcomes. (For relevant empirical studies, see e.g., [43,44,45,46].) |

| 32 | Cf. Dorsey, Ch. 5: “[T]o value some object, one must treat the fact that one values it as having some sort of normative significance—a fact that should not simply be ignored in prudential deliberation”. |

| 33 | Recognition respect, in Darwall’s sense, is “a disposition to regulate conduct toward something by constraints deriving from its nature.” ([49], 43) While such regulation of conduct might be understood to involve behavior that is viewed as “protective”, I take duties corresponding to recognition respect to be primarily duties of non-interference; whereas duties to protect I understand to be duties of a more positive nature. |

| 34 | Cf. [50], who argues that dignity, for Kant, is not a type of value, but rather a type of deontological status. |

| 35 | One way of cashing this out is in terms of “intrinsic good-making factors”—i.e., features of the bearers of intrinsic value that tell in favor of its value. Such factors may include facts about a person’s pro-attitudes, e.g., the fact that a person desires a certain state; but they may also include factors that do not have to do with pro-attitudes, such as that a certain state is an instance of achievement (cf. [23], 82). Note that this idea is compatible with either acceptance or rejection of an objective list theory of well-being. It is compatible with an objective list theory because it might be held that what makes a life good for its bearer does not consist either in pleasurable experience or desire-satisfaction (even if it consists in part in what the agent values). It is compatible with rejection of objective list theories, because it is compatible with taking pleasure or desire-satisfaction to be a good-making factor. |

| 36 | |

| 37 | The discount value of a delay between days in the future and days in the future, V(, ), relative to Al, is the r such that Al is indifferent between r units of well-being days from now and one unit of well-being days from now. |

| 38 | See Figure 2. Ahmed offers an analogy involving radioactivity. Suppose S is a composite body consisting of an equal number of both atoms of polonium-212, which decays quickly, and uranium-235, which decays slowly. At first, the decay of polonium makes a big difference to the proportion of original atoms that remain. However, as time goes on, the decay of uranium makes an increasing contribution. |

| 39 | The argument is straightforward. (See [7], §2.) Suppose that the discount value, for Al, of a delay of 1 day is 0.2 if the delay begins 1 day in the future, but 0.8 if the delay is 2 days in the future. Stationarity implies Al retains this pattern of preference. Thus, for any N, the following holds: (1) On Monday, Al is indifferent between N units on Thursday and 0.8N units on Wednesday. (2) On Tuesday, Al is indifferent between N units on Thursday and 0.2N units on Wednesday. Suppose that on Monday Al’s well-being schedule is as follows: (3) 60 units on Wednesday, and 60 on Thursday. On Monday we offer Al the chance to give up 20 of the Wednesday units for 30 additional units on Thursday. (1) implies he will accept. So Al then faces the following schedule: (4) 40 units on Wednesday, 90 units on Thursday. On Tuesday, we offer All the chance to give up 40 units on Thursday in exchange for 10 additional units on Wednesday. (2) implies he will accept this too. So, by Wednesday Al is facing the following: (5) 50 units on Wednesday, and 50 on Thursday. Thus, Al’s preferences have led him voluntarily to accept trades that make him worse off on some days and better off on none. |

| 40 | Future bias is the preference for positive experiences or states of affairs to be located in the future, all else being equal. |

| 41 | See [55] for a recent defense of future bias. |

References

- Westman, A.; Rosen, M.; Bjornstig, U. Parachuting from fixed objects: Descriptive study of 106 fatal events in BASE jumping 1981–2006. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2008, 42, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soreide, K.; Ellingsen, C.; Knutson, V. How dangerous is BASE jumping? An analysis of adverse events in 20,850 jumps from the Kjerag Massif, Norway. J. Trauma 2007, 62, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfit, D. Reasons and Persons; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Parfit, D. Personal Identity. Philos. Rev. 1971, 80, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Frias, J.; McNamee, M. Ethics, Brain Injuries, and Sports: Prohibition, Reform, and Prudence. Sport Ethics Philos. 2017, 11, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, D. Prudence and authenticity: Intrapersonal conflicts of value. Philos. Rev. 2014, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Rationality and Future Discounting. Topoi 2020, 39, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, G.; Castellani, R.; Cassidy, J.; Schneider, G.M.; Schneider, K.J.; Echemendia, R.J.; Dvorak, J. Examining later-in-life health risks associated with sport-related concussion and repetitive head impacts: A systematic review of case-control and cohort studies. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2023, 57, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O’Donoghue, T. Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slote, M. Goods and Virtues; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kamm, F. Rescuing Ivan Ilych: How We Live and How We Die. Ethics 2003, 113, 202–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodworth, A. Prudence, Well-Being and Sport. Sport. Ethics Philos. 2014, 8, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathwood, C. Which Desires Are Relevant to Well-Being? Noûs 2019, 53, 664–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchak, L. Why high-risk, non-expected-utility-maximising gambles can be rational and beneficial: The case of HIV cure studies. J. Med. Ethics 2017, 43, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchak, L. Risk and Rationality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, D. Reductionist Contractualism: Moral Motivation and the Expanding Self. Can. J. Philos. 2000, 30, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P. Duty to Self: Moral, Political, and Legal Self-Relation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Darwall, S. The Value of Autonomy and Autonomy of the Will. Ethics 2006, 116, 263–284s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Risking Future Generations. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2018, 21, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S.O. Hypothetical Retrospection. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2007, 10, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. Lectures on Ethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, D. A Near-Term Bias Reconsidered. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 2019, 99, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, D. A Theory of Prudence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shue, H. Basic Rights: Subsistence, Affluence, and U.S. Foreign Policy: 40th Anniversary Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vranas, P. The indeterminacy paradox: Character evaluations and human psychology. Nous 2005, 39, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doris, J.M. Lack of Character: Personality and Moral Behavior; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, G. The nonexistence of character traits. In Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; Volume 100, pp. 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, G. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy and risk of suicide in former athletes. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2014, 48, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroon, J.C.; Winkelman, R.; Bost, J.; Amos, A.; Mathyssek, C.; Miele, V. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Contact Sports: A Systematic Review of All Reported Pathological Cases. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117338. [Google Scholar]

- Manley, G.; Gardner, A.J.; Schneider, K.J.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Bailes, J.; Cantu, R.C.; Iverson, G.L. A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2017, 51, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, E. Harming as Causing Harm. In Harming Future Persons: Ethics, Genetics, and the Nonidentity Problem; Roberts, M., Wasserman, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock, B. Wrongful Life and Procreative Decisions. In Harming Future Persons: Ethics, Genetics, and the Nonidentity Problem; Roberts, M., Wasserman, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Velleman, J.D. Persons in Prospect. Philos. Public Aff. 2008, 36, 221–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.I. Compensation for Historic Injustices: Completing the Boxill and Sher Argument. Philos. Public Aff. 2009, 37, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J. The Non-Identity Problem. Ethics 1986, 96, 804–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, I. Rights and the Asymmetry Between Creating Good and Bad Lives. In Harming Future Persons: Ethics, Genetics, and the Nonidentity Problem; Roberts, M., Wasserman, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Chapter 2; pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sartorio, C. Causation and Free Will; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Korsgaard, C. The Sources of Normativity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sailors, P.R. Personal foul: An evaluation of the moral status of football. J. Philos. Sport 2015, 42, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, N. Sport, parental autonomy, and children’s right to an open future. J. Philos. Sport 2007, 34, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, J. On Liberty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, G. Paternalism: Some second thoughts. In Paternalism: Theory and Practice; Sartorius, R., Ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1983; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- De Beaumont, L.; Théoret, H.; Mongeon, D.; Messier, J.; Leclerc, S.; Tremblay, S.; Lassonde, M. Brain function decline in healthy retired athletes who sustained their last sports concussion in early adulthood. Brain A J. Neurol. 2009, 132, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, L.D.; Lassonde, M.; Leclerc, S.; Théret, H. Long-term and cumulative effects of sports concussion on motor cortex inhibition. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskiewicz, K.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Bailes, J.; McCrea, M.; Cantu, R.C.; Randolph, C.; Jordan, B.D. Association between recurrent concussion and late-life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players. Nuerosurgery 2005, 57, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskiewicz, K.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Bailes, J.; McCrea, M.; Harding, H.P.; Matthews, A.; Cantu, R.C. Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2007, 39, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.S. The Value of Dangerous Sport. J. Philos. Sport 2005, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.S. Children and Dangerous Sport. J. Philos. Sport 2007, 34, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwall, S. Respect and the Second-Person Standpoint. Proc. Addresses Am. Philos. Assoc. 2004, 78, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R. The Dignity of Humanity. In Rethinking the Value of Humanity; Buss, S., Theunissen, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; Chapter 6; pp. 153–180. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, R. A Theory of the Good and the Right; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Railton, P. Facts and Values. Philos. Top. 1986, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Dispositional Theories of Value. In Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, T. On Whether to Prefer Pain to Pass. Ethics 2011, 121, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddon-Mitchell, D.; Latham, A.J.; Miller, K. Can we turn people into pain pumps?: On the Rationality of Future Bias and Strong Risk Aversion. J. Moral Philos. 2023, 1, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, R. Choosing for Changing Selves; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilbertson, E. The Prudential Rationality of Risking Traumatic Brain Injury in Dangerous Sport: A Parfitian Defense. Philosophies 2025, 10, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10030059

Gilbertson E. The Prudential Rationality of Risking Traumatic Brain Injury in Dangerous Sport: A Parfitian Defense. Philosophies. 2025; 10(3):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10030059

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilbertson, Eric. 2025. "The Prudential Rationality of Risking Traumatic Brain Injury in Dangerous Sport: A Parfitian Defense" Philosophies 10, no. 3: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10030059

APA StyleGilbertson, E. (2025). The Prudential Rationality of Risking Traumatic Brain Injury in Dangerous Sport: A Parfitian Defense. Philosophies, 10(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10030059