Abstract

This study examines the social, economic and cultural impacts that Latin American women face due to climate-induced displacement, considering these impacts as arenas of conflict and negotiation. Using an intersectional framework, the study analyses how climate disasters exacerbate structural inequalities rooted in patriarchal systems, thereby constraining women’s adaptive capacity while simultaneously catalysing resistance strategies. Through a comparative analysis of Bangladesh and the Dry Corridor in Central America using a Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI), the study reveals that displaced women navigate contested spaces, disputing access to resources, legal recognition and territorial belonging, while constructing transnational solidarity networks and cooperative economies. The emergence of women climate refugees challenges international legal frameworks, exposing critical gaps in protection regimes. The findings emphasise the need for gender-responsive policies that recognise women as transformative agents who negotiate power asymmetries in contexts of environmental crisis, not merely as vulnerable populations. This research contributes to our understanding of the nexus between climate change, gender and migration by foregrounding the dialectic of domination and agency in Latin American displacement processes.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context and Objectives

The aim of this study is to examine the social, economic and cultural implications of Latin American women’s forced displacement by the climate crisis, configured in spaces of conflict and negotiation. The intersection of gender, migration and climate change reveals systematic patterns of differentiated vulnerability (Das 2024), in which women, particularly in the Latin American context, experience the impacts of the global climate crisis (Mijangos 2023). Against this background, the research question arises: What are the social, economic and cultural factors that influence the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Latin American women in the face of forced displacement, and what strategies have they developed to cope?

Forced displacement due to climate change has become one of the most pressing issues of the 21st century. However, the analysis of climate migration has tended to focus on the vulnerability of the displaced, without considering the spaces of conflict and negotiation that emerge in these processes. From the perspective of ‘Arenas of Conflict and Collective Experiences. Utopian horizons and domination’ (Tarrés et al. 2014), it is possible to reframe this discussion by including the concept of arenas of conflict, in which affected communities are not just victims, but active subjects who negotiate, resist and build new forms of organisation.

1.2. Terminological Clarification

The field of study on human mobility induced by climate change is characterised by a proliferation of unsystematised terminology, generating conceptual ambiguities and hindering comparability between research studies. To provide analytical precision, this study adopts a set of operational definitions to guide its conceptual and empirical framework. Firstly, the term ‘climate displacement’ refers to the forced movement of people caused by environmental changes, whether sudden, such as cyclones or floods, or gradual, such as drought, desertification or rising sea levels, when remaining in the territory of origin becomes unsustainable. This displacement can occur both within national borders and to other countries. This will be the predominant general concept throughout the study.

The concept of a ‘climate refugee’, on the other hand, is primarily a conceptual and political category with no legal recognition in international law. The 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees does not recognise environmental factors as grounds for seeking asylum (UNHCR 2001; Sussman 2023). Despite its legal non-existence, the term is used here for analytical and critical purposes, particularly to highlight the gap in international protection (Mijangos 2023), emphasise the coercive nature of displacement—differentiating it from ‘voluntary migration’—and link the analysis to advocacy movements demanding its formal recognition.

By contrast, a climate migrant is defined as someone who moves due to environmental factors, exercising a certain degree of choice, gradualness and planning. This presupposes resources and foresight. However, due to the ambiguity of this term on the voluntary-coercive continuum, it is avoided in this study, as it dilutes the forced dimension of climate mobility in highly vulnerable contexts. The concept of human mobility is an umbrella term encompassing various modes of movement, including migration (voluntary), displacement (forced) and planned relocation. This term is widely adopted in international policy documents such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and the mandate of the Task Force on Displacement of the Paris Agreement.

Following Morera and Biderbost (2023) and Castillo and Zickgraf (2024), this study favours the term ‘forced climate displacement’, as it is considered to more accurately capture three central elements: the involuntary nature of the process (the ‘forced’ dimension), the specific environmental causality (the ‘climate’ dimension) and the residual agency of those affected. The term ‘displacement’ is chosen over ‘refuge’ to avoid the connotation of passivity associated with the latter. However, the term ‘climate refugees’ is used in three instances: when discussing the debate on their legal recognition (Section 2.3), when referencing academic works that employ it, and when examining the category as a contested social construct.

1.3. Climate Change as Threat Multiplier and Arena of Conflict

This reality manifests itself in a scenario where climate change acts as a multiplier of pre-existing threats, exacerbating structural inequalities and gender-based power imbalances (General Recommendation 37, CEDAW 2018; Setyorini et al. 2024). The intensification of extreme weather events, characterised by droughts, floods and increasingly intense meteorological phenomena, is reshaping patterns of habitability in many regions of Latin America, forcing displacement and affecting vulnerable communities (Almulhim et al. 2024). In this context, climate-related disasters not only represent immediate humanitarian crises, but also act as catalysts for social transformations in which women often negotiate, resist and build new forms of organisation (Ripple et al. 2024).

A gender perspective in the analysis of climate-induced forced displacement reveals how patriarchal structures condition women’s vulnerability and responsiveness to these crises (Carter 2015), limiting their access to resources, information and protection (Du 2024). The emergence of female climate refugees complicates forced migration (Batista et al. 2024), challenges international legal frameworks and exposes critical gaps in existing protection systems (Mijangos 2023). According to Tarrés et al. (2014), these dynamics are part of disputes over territory and resources, where restrictive migration policies and border securitisation function as control mechanisms. Thus, climate refugees not only seek to survive, but also to contest their existence within established legal frameworks (IDMC 2024). The geopolitical implications are manifold: from the reformulation of migration policies to the emergence of new power dynamics between sending and receiving states (IDMC 2024). In Latin America, the intersection of socio-economic inequality, ethnic discrimination and institutional weakness intensifies the conditions of vulnerability for displaced women (Mai 2024). These impacts go beyond material losses, affecting family structures, community networks and livelihoods (IDMC 2024). As Solorio (2024) argues, there is an urgent need to look beyond traditional approaches and consider the gender and power dynamics that shape the experience of displacement. In this context, new patterns of vulnerability are emerging, influenced by both climate change and historical gender inequalities, requiring innovative, culturally sensitive and gender-responsive policy responses (Rojas-Rendón and Franco 2024). This issue is embedded in a historical continuum: from early societies, through evolutionary processes (Macintosh et al. 2017), to contemporary scenarios of gender inequality in relation to the environment (Loots and Haysom 2023; Thakur 2023; Dev and Manalo 2023). Using an integrative theoretical-conceptual framework that articulates gender analysis, climate change studies and evolutionary perspectives, and a qualitative methodology based on a literature review and case study, the analysis shows how social norms, historically biased in favour of men, deepen women’s vulnerability to climate change. However, it also identifies opportunities for empowerment and social transformation in women’s adaptation and resilience processes.

2. Critical Intersectional Theorising

The confluence of analytical perspectives in this theoretical-conceptual framework establishes a multidimensional prism for examining gendered displacement in the Latin American context. The integration of ecofeminist theory, as proposed by Doley (2025), allows us to deconstruct how patriarchal structures reinforce women’s differential vulnerability to climate shocks, transforming adaptation and resilience into powerful mechanisms of women’s empowerment. This approach reveals the complex interactions between systems of gender oppression and the asymmetrical impacts of climate change, positioning women not only as disproportionate victims of these phenomena, but also as key agents of social and environmental transformation in contexts of forced mobility. The inclusion of the geopolitical dimension articulated by Topalidis et al. (2024) enriches the analysis by contextualising the emerging category of women climate refugees within the regional and global power dynamics that characterise Latin America. This perspective highlights the strategies of collective resistance employed by displaced women, who, far from representing victimised passivity, constitute nuclei of social innovation that challenge entrenched structural inequalities in the region. The interweaving of environmental, socio-economic and political factors reveals how women develop survival mechanisms that go beyond mere adaptation to become transformative practices that challenge extractivist models and hegemonic power relations.

On the contemporary horizon of development and human mobility studies, this integrative framework facilitates the identification of predictive patterns that anticipate gendered climate displacement. The symbiosis between host communities and displaced women emerges as a potential catalyst for socio-economic innovation, where the experiences and knowledge of women climate refugees enrich the host social fabric. Data analysis and computational modelling technologies, applied with a gender approach, allow the visualisation of intervention scenarios that enhance the social, cultural and economic capital of displaced women, while contributing to the consolidation of more equitable and resilient societies. This holistic approach reconfigures public policies towards an integrated continuum that reconciles humanitarian, environmental and development dimensions, overcoming the historical fragmentation that has hindered effective gender-sensitive responses to forced displacement in Latin America.

2.1. Climatic History of Women: From Paleolithic to Anthropocene

2.1.1. Evolutionary Foundations of Women’s Climate Adaptation

In the context of the climate crisis, the woman emerges as a symbol of transformation, embodying both vulnerability and strength in the face of contemporary environmental challenges. Not only does she represent a group particularly affected by ecological crises, but she also stands as a key architect of sustainable solutions, weaving a web where ancestral knowledge intertwines with modern innovation. This figure embodies female resilience, adaptability and leadership in multiple spheres, from community-based natural resource management to the highest levels of international climate policy (Turquet et al. 2023). Located at the intersection of the struggle for gender equality and environmental action, this embodiment serves as an essential catalyst for a just and sustainable future, challenging and forging new pathways to global resilience.

The relationship between women and climate is deeply rooted in human evolution, as evidenced by palaeontological findings such as Lucy (Gibbons 2024) and studies of species such as Australopithecus and Homo (Robson and Wood 2008). From the earliest times, women have played a key role in adapting to climatic variability through subsistence strategies and biocultural care (Davis and Shaw 2001; Bogin et al. 2014; Martin 2007). Technological innovation—such as the use of fire—and knowledge of the environment reinforced this role in human expansion (Carmody and Wrangham 2009; Hublin et al. 2015; de Lafontaine et al. 2018). In the Upper Palaeolithic, their mastery of plants and natural resources was essential to survive the last ice age, and in the Neolithic, they consolidated their central role in agricultural production and the sustainability of early societies (Betti et al. 2020; Bolger 2010).

2.1.2. Palaeoanthropological and Archaeological Evidence of Gender Roles in Climate Adaptation

Archaeological evidence, including patterns of sexual dimorphism in dental wear and stable isotope analysis, reveals that gender-based divisions of labour date back to the Middle Pleistocene. These patterns suggest behavioural differences between the sexes, possibly driven by adaptations to variable environments, whereby females and males optimised resources in complementary ways to enhance group survival. For instance, stable isotope studies of Homo heidelbergensis remains, which are approximately 400,000 years old and were excavated at the Atapuerca site in Spain, demonstrate dietary differentiation by sex that correlates with seasonal climate variability. Specifically, variations in isotopic ratios suggest that, during periods of scarcity, females consumed more plant resources, while males focused on protein-rich prey. This reflects adaptive strategies in response to environmental oscillations (Pérez-Pérez et al. 1999). This early evidence sets a precedent for more complex patterns in later stages of the Upper Pleistocene.

During the climatic oscillations of Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5 (100,000–70,000 years before present (BP)), findings at sites such as Blombos Cave in South Africa illustrate an evolution towards specialised technologies; in particular, the processing of ochre and the manufacture of tools for working with animal skins (such as sewing awls and composite adhesives) suggest a possible female specialisation in technologies for body thermoregulation, which were essential for coping with glacial–interglacial cycles and maintaining thermal homeostasis in fluctuating environments (Haaland and Nel 2023). This evidence is complemented by research at Rose Cottage Cave, another key Middle Stone Age (MSA) site in South Africa dated between 96,000 and 30,000 years before present (BP), which provides a detailed record of ochre use over sixty thousand years. Initial excavations by Malan, and subsequent ones by Harper, revealed ochre pieces characterised by their colour (predominantly bright red), hardness (generally soft), grain size (clayey or silty), and geological type (mainly shales). The post-Howiesons Poort layers (after ~59,000 years BP) contain the highest absolute number of ochre pieces; the Howiesons Poort layers (65,000–59,000 years BP) exhibit the highest frequency per sediment volume; and the pre-Howiesons Poort layers (before ~65,000 years BP) show the highest utilisation rate, with over 50% of pieces modified. Traces of use include rubbing and grinding, as well as combinations of both. In rare cases, there is evidence of scratching. These traces serve as proxies for inferring practical applications. Rubbing allowed red ochre powder to be transferred directly to soft surfaces, such as human skin or animal hides. This was suitable for purposes such as body colouring, marking or skin protection (e.g., against the sun, insects or bacteria). Grinding, on the other hand, produced ochre powder that could be mixed with water or other materials to create paints, cosmetics, or adhesives. This implies multifunctional use and evident temporary changes at the site (Hodgskiss and Wadley 2017). These patterns at Rose Cottage reinforce the idea that ochre processing, possibly associated with female roles in ethnographic analogies, played a crucial role in human adaptation. It evolved from basic survival uses in the early stages to more complex applications in later periods.

2.1.3. From Ancient Civilizations to Contemporary Crisis

These contributions are reflected in mythologies such as Demeter (Difabio 2021), Pachamama (Sayre and Rosenfeld 2021) and the Totonac deities (Lugo-Morin 2020), which symbolise the link between the feminine and ecological management (Strassmann and Gillespie 2002). Even after their exclusion from formal power structures, women maintained ecological knowledge in local spaces, which became arenas of conflict and negotiation (Johri 2023; Hunt and Rabett 2014). The Caral civilisation and settlements such as Áspero demonstrate how women led processes of resilience and social cohesion in the face of climatic migrations over 5000 years ago (Shady 2006a, 2006b). In the context of the Anthropocene (Malhi 2017), this historical role needs to be reassessed. Gender inequalities increase their vulnerability, especially in developing countries (Jost et al. 2015), but also position them as key actors in the fight for climate justice (Loots and Haysom 2023; Thakur 2023; Singh et al. 2021). The integration of traditional and scientific knowledge is a strategic resource for adaptation (Huyer et al. 2020). This double condition—vulnerability and leadership—is claimed by currents such as ecofeminism, which denounces the relationship between patriarchal oppression and environmental exploitation (Doley 2025). In the midst of the climate crisis (Dev and Manalo 2023), women are emerging as community leaders (Smith 2022), driving transformative action (Turquet et al. 2023) and proposing inclusive solutions that benefit historically marginalised sectors. Their role in areas such as climate finance demonstrates multiplier effects in agriculture, energy and the regenerative economy (Lugo-Morin 2025), although their low involvement in high-level decision-making persists. The gap between commitments and implementation was evident at COP15, where only 83.3 of the 100 billion pledged was mobilised (Qi and Qian 2023). In other areas, urban planning has been key to designing gender-responsive solutions, such as inclusive transport systems and resilient green spaces (Kerry and Sayeed 2024; Zavala et al. 2024). For a low-carbon future (Lugo-Morin 2025), it is essential to ensure a just transition that fully engages women as agents of change. This means creating equitable opportunities in the green economy, redressing inequalities in transition sectors, and preventing climate policies from deepening existing inequalities (Pinho-Gomes and Woodward 2024). In this way, the historical trajectory of the link between women and climate—from the dawn of humanity to the present day—is consolidated as a fundamental axis for survival and sustainability on an increasingly unpredictable planet.

2.2. Spaces of Conflict and Negotiation in the Context of Climate Change

Throughout history, climate change has accompanied human evolution, manifesting itself in natural cycles of warming and cooling driven by factors such as Earth’s orbit, solar activity, volcanic eruptions or ocean currents. In this evolutionary process, early humans—particularly women—developed adaptive strategies to ensure collective survival (Macintosh et al. 2017). Their role in household resource management (Davis and Shaw 2001; Khanom et al. 2022), agriculture, food security and transmission of traditional ecological knowledge made them pillars of community resilience. In addition, women were key to building support networks and local innovations to cope with climate variability (Okesanya et al. 2024). However, these contributions have historically coexisted with structural and cultural barriers that have limited their participation in environmental decision-making. Research in regions such as the Himalayas and Colombia highlights these limitations and argues for equitable inclusion in adaptation processes (Barrios et al. 2025; Das 2024).

The current climate crisis, which has accelerated since the industrial revolution, is unprecedented in scale and speed. Greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and uncontrolled urbanisation have led to profound changes in global ecosystems (Barcellos 2024). This situation is exacerbated by unsustainable consumption patterns and cascading effects, such as the melting of permafrost and the intensification of extreme events (Hugelius et al. 2024). In this context, women are emerging as key actors in formulating resilient responses. Their ability to lead sustainable practices and strengthen community cohesion is widely recognised (Ripple et al. 2024). Women’s empowerment in climate change contexts not only contributes to greater equity, but also enhances the effectiveness of adaptation strategies, particularly in terms of resource management, food sovereignty and building territorial resilience. However, climate change not only exacerbates existing vulnerabilities, but also gives rise to new conflict and negotiation scenarios. Forced migration caused by environmental disasters and livelihood degradation creates spaces of tension where state, corporate and community interests converge (Tarrés et al. 2014). In these spaces of conflict and negotiation, migrant women face particular challenges: they struggle for access to basic resources, the defence of their rights and political recognition in contexts marked by exclusion and structural inequality (Das 2024; Mijangos 2023). Their migratory experience, far from being a simple physical displacement, becomes an expression of resistance to systems that have historically marginalised them. Understanding these spaces as scenarios where power relations are reconfigured allows us to make visible women’s agency in processes of adaptation, resistance and social transformation. Climate migration should therefore be analysed not only from an environmental perspective, but also from a gender perspective that recognises and empowers women’s agency in the struggle for climate and social justice.

Rising sea levels (Vousdoukas et al. 2023), salinisation of aquifers (Abd-Elaty et al. 2024), coastal erosion (Pang et al. 2023) and loss of biodiversity (Boakes et al. 2024) are exacerbating pressures on vulnerable populations, leading to forced migration and geopolitical tensions (Almulhim et al. 2024). Such displacements, driven by extreme environmental phenomena, not only expose the structural weaknesses of many regions—as illustrated by Hurricane Otis in Mexico (Gervacio et al. 2024)—but also create spaces of conflict and negotiation shaped by pre-existing inequalities (Tarrés et al. 2014). Women, in particular, face particular challenges and multiple forms of exclusion in climate-induced migration. Far from being mere victims, many emerge as agents of transformation. In contexts of forced displacement, they forge networks of solidarity and resistance that challenge patriarchal structures and promote new forms of autonomy and collective organisation (Setyorini et al. 2024). This phenomenon has led to a shift in climate risk management strategies. In recent decades, the focus has shifted from disaster management to a resilience and sustainable development paradigm. This shift has revalued local action and community leadership, highlighting the role of women as catalysts for change (Ripple et al. 2024).

Initiatives such as climate laboratories have emerged as platforms for social and technological innovation at the community level. These spaces enable the co-creation of solutions tailored to specific contexts, promoting territorial resilience, social cohesion and energy sovereignty. Similarly, climate education that integrates scientific knowledge with traditional wisdom, alongside technical training for green jobs, has become a cornerstone strategy for empowering women and increasing their participation in decision-making (Nusche et al. 2024). The international response to this crisis finds a critical tool in the climate finance ecosystem. The Green Climate Fund (GCF), established at COP16 and formalised at COP17 (Green Climate Fund 2024), aims to finance adaptation and mitigation efforts in developing countries. Despite unfulfilled commitments such as the $100 billion target for 2020 (Qi and Qian 2023), the GCF has redefined its priorities for 2024–2027, focusing on strengthening vulnerable countries, mobilising the private sector and protecting vulnerable populations. Latin America has received 24% of the GCF’s global portfolio, but faces persistent challenges: limited regional participation, limited technical capacity, reliance on intermediaries, and a lack of projects targeting climate-displaced people (Green Climate Fund 2024). This gap is worrying given UNHCR’s warnings about the increasing risks faced by those fleeing extreme environmental conditions (UNHCR 2024). The recent COP29 in Baku marked a milestone by tripling funding to $300 billion annually by 2035. This shift in the international financial architecture provides an unprecedented opportunity to explicitly include climate displacement women as strategic actors in resource allocation, policy design and implementation of resilient solutions (Tamasiga et al. 2024). Climate disasters are not only a growing global threat, but also an emerging arena for socio-political contestation and negotiation, where displaced women are redefining their roles, leading community resilience efforts and asserting their right to live in a just, inclusive and sustainable future.

2.3. Climate-Induced Displacement: Gender, Refugeehood and Geopower

Forced displacement, defined as the involuntary departure of people from their homes due to external threats to their safety and livelihoods (Hirsh et al. 2020; Stilz 2025), is one of the most pressing phenomena of the current climate crisis. Over the past decade, climate change has been a central driver of this process: between 2008 and 2018, 265 million people were displaced by disasters, 85% of which were linked to climate-related causes. By the end of 2023, almost three-quarters of displaced people were living in countries highly exposed to climate hazards (Alliance of Bioversity International and International Centre for Tropical Agriculture 2024), highlighting a clear link between environmental vulnerability and human mobility.

Projections indicate that between 5.8 and 10.6 million people in Latin America could be displaced internally by 2050 due to climate-related factors (Almulhim et al. 2024). This trend is emphasised by the World Bank’s Groundswell reports, which predict up to 17 million internal climate displacements in the region under a pessimistic scenario involving high emissions and unequal development. Significant concentrations are expected in southern Mexico (1.8 million), Central America’s Dry Corridor (3.9 million) and Brazil’s Northeast (5 million) (Rigaud et al. 2018; Clement et al. 2021). These estimates could rise to 44 million by 2100 under business-as-usual warming trajectories, highlighting the escalating urgency of the issue. Of particular concern is that women account for 51–55% of internally displaced populations in the region (IDMC 2023), yet most national adaptation plans continue to overlook gender-disaggregated projections, thereby limiting effective responses to these vulnerabilities. These phenomena are exacerbating water scarcity and causing mass displacement, particularly in countries such as Mexico, Ecuador, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua (Murray-Tortarolo and Salgado 2021). These processes are reshaping territories and giving rise to scenarios in which structural conflicts converge with new social negotiations. In this context, women face a double condition: increased risks of violence, exploitation and exclusion from access to resources (CEDAW 2018), while playing an active role in rebuilding communities (Alliance of Bioversity International and International Centre for Tropical Agriculture 2024). Drawing on the concept of ‘arenas of conflict and collective experience’ (Tarrés et al. 2014), forced displacement emerges as a space where women negotiate belonging, leadership and new forms of organisation. Understanding climate migration from this perspective is crucial for designing gender-sensitive policies (Ripple et al. 2024).

Climate change acts as a catalyst for crises that go beyond physical displacement, affecting cultural identities, social cohesion and mental health (Allen et al. 2024). Host communities face logistical challenges that can perpetuate exclusion if not addressed equitably (Heslin et al. 2019). Therefore, cross-sectoral responses that integrate climate justice, gender equality and community resilience are essential (Khan 2024). Promoting equality in decision-making is not only an ethical principle, but also an effective strategy (Asian Disaster Preparedness Center 2021). General Recommendation No. 37 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women sets a new benchmark of 50% female participation in decision-making (CEDAW 2018), surpassing the previous threshold of 30%. This shift requires overcoming institutional resistance and pseudo-feminist rhetoric (Jagernath and Nupen 2023) through economic empowerment, gender education and disaggregated data (Smits and Huisman 2024). This approach not only addresses the consequences of displacement, but also promotes structural changes towards equity (Castillo and Zickgraf 2024). In Latin America, where economic inequality, structural violence and institutional fragility persist (Mijangos 2023), the leadership of civil society and women’s movements is paving the way for culturally relevant responses (IDMC 2024). The active participation of indigenous and Afro-descendant women, alongside transnational cooperation through CELAC, MERCOSUR and the Pacific Alliance, is crucial to addressing the issue regionally (Koomson and Koomson 2024). Cases such as Ecuador, which constitutionally recognises the right to protection from climate change, mark significant progress (Toaquiza 2024). Climate justice and women’s economic and educational autonomy are pillars of a just climate migration framework (Reeves et al. 2023; Rojas-Rendón and Franco 2024).

Climate refugees face triple vulnerability: gender, displacement and lack of legal recognition (Mijangos 2023). Nevertheless, their agency shines through in cooperatives, transnational networks, and alliances with social movements (Andersen et al. 2017), challenging extractivist models and opening up new pathways for adaptation (Methmann and Oels 2015). From a critical perspective (Tarrés et al. 2014), the territories they inhabit become arenas of contestation over water, land or housing, shaped by restrictive migration policies and the securitisation of borders (Allin 2024; IDMC 2024). This geopolitical dimension is global. From Bangladesh (Ahmed and Eklund 2021) to Africa, Asia and Latin America (Rao et al. 2017; IDMC 2024), millions of women are displaced by climate change. Their lack of legal recognition is being met with new responses that combine microfinance, ancestral knowledge, and women-led strategies (Gerhard et al. 2023). These community-driven and technological solutions are redefining climate governance through a gender lens (Bharwani et al. 2024), positioning women as leaders of resilient adaptation.

In Latin America, climate displacement is reshaping geopolitical tensions and opportunities. Critical regions such as the Caribbean, the Amazon, the Andes and the Dry Corridor are forcing organisations such as CELAC, MERCOSUR and the Pacific Alliance to rethink cross-border cooperation mechanisms (Cabral et al. 2024; Solorio 2024). This includes proposals such as climate visas, early warning systems and adaptation funds (Cisneros et al. 2024). A forward-looking approach envisions a comprehensive infrastructure for climate refugees: digital identity, women-led cooperatives, adaptive legal frameworks, green microfinance, and sustainable host cities (World Economic Forum 2023; Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship 2024). These solutions not only recognise the transformative role of women, but also demand climate justice and reparations from high emitting countries. Latin America has a historic opportunity to lead an innovative, intersectional and decolonial response that places displaced women at the centre of global change.

2.4. Methodological Framework: Comparative Analysis and GVI

This study adopts a sequential explanatory mixed methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark 2018). First, a systematic literature review is conducted (Section 2.1, Section 2.2 and Section 2.3) to establish the theoretical and conceptual framework of differentiated gender vulnerability to climate displacement. This is followed by a comparative analytical phase that uses an instrumental case study of Bangladesh (Stake 1995) as a benchmark for community adaptation led by women. This is then contrasted with the Central American Dry Corridor. Bangladesh was selected as the case study based on three criteria: structural comparability (both regions have high climate exposure, in the form of cyclones and droughts respectively, as well as socio-economic vulnerability and restrictive patriarchal structures); documented innovation (it has experience with gender microfinance and rural women’s cooperatives, which have been implemented for over 30 years, as detailed by Kabeer (2011)); and strategic relevance (the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta is the region with the highest projected climate displacement globally, with between 75 and 95 million people expected to be displaced by 2050, according to Rigaud et al. (2018)). In this context, the Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI) serves as an analytical tool to quantify the qualitative dimensions identified in the literature review, thus facilitating systematic transregional comparisons.

This comparative approach adopts a heuristic and exploratory framework. While Bangladesh and the Dry Corridor differ significantly in cultural, historical, and institutional contexts, their structural comparability in terms of climate exposure, patriarchal constraints, and socio-economic vulnerability enables the identification of shared patterns of gendered vulnerability. The GVI serves not as a universalizing metric, but as an analytical tool to systematically examine how similar climate-patriarchal pressures interact with local adaptive capacities across distinct regional contexts. This methodological choice acknowledges contextual specificity while revealing transnational dynamics of climate displacement.

3. Case Study: Comparative Analysis of Gendered Climate Vulnerability

The climate crisis is shaping new geographies of female displacement in Latin America, creating spaces for conflict and negotiation in which women are redefining their agency in the face of historical structures of inequality. Analysing these processes requires an approach that considers the social, economic, and cultural implications of forced displacement caused by climate events. This approach must also take into account how gender structures both vulnerability and possibilities for resilience. The relational approach to vulnerability is therefore essential for identifying how climatic and patriarchal pressures interact with the social and economic resources available to displaced women.

The Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI), developed by Smits and Huisman (2024), is a key methodological contribution to understanding these dynamics. It is based on a standardised, composite approach that enables vulnerability to be measured in different contexts using social, economic, and gender indicators that are considered from a comparative perspective. While the original GVI is more complex, combining multiple dimensions via principal component analysis (PCA), its relational logic can be applied to local case studies, enabling consistent analysis of the relationship between vulnerability-increasing pressures and mitigation resources. Following this logic, a simplified version of the relational approach is adopted here, defined as follows:

GVI_(relational) = (Climate exposure + Patriarchal norms) ÷ (Social networks + Economic opportunities).

This approach enables us to examine how gender inequalities influence the migration trajectories of women displaced by the climate crisis, while also assessing community adaptive capacity in two contexts offering cross-learning opportunities: Bangladesh (Khanom et al. 2022) and the Central American Dry Corridor (Huber et al. 2023).

3.1. Bangladesh: Climate Migration and Urban Adaptation

3.1.1. Context and Patterns of Displacement

A thematic analysis focusing on the intersection between gendered vulnerability and adaptive strategies was conducted based on the findings of Khanom et al. (2022), integrating recent data. The qualitative methodology of the study, which involved collecting life histories and conducting in-depth interviews (n = 52) and focus group discussions (n = 6) in settlements such as Bhola and Cox’s Bazar, revealed that women face a range of vulnerabilities, from natural disasters to urban risks such as gender-based violence and labour exploitation. For example, one interviewee, aged 30, reported experiencing sexual assault in an informal employment setting, emphasising how migration exacerbates insecurity (quote: ‘I was sexually assaulted there. I could not continue in that job’ (Khanom et al. 2022, p. 8). Around 70% of women reported cultural restrictions that limited their mobility, while 80% developed informal strategies, such as making seashell handicrafts, to generate income, but these strategies simultaneously perpetuate precarious livelihoods. Integrating studies such as the IDMC (2024), which documents a 1.3 million increase in cyclone-related displacements in 2023, alongside Ahmed and Eklund (2021), who report a significant number of internally displaced women, reveals a vicious cycle. This cycle begins with initial adaptation (migration) and leads to maladaptation (social exclusion).

3.1.2. GVI Analysis and Vulnerability Dimensions

Based on this evidence, Bhola may be assigned a moderate score of 3 on a normalised scale of 1–5 (with 5 representing extreme exposure), reflecting the acute climatic risks it faces. In terms of patriarchal norms, the study indicates that 70% of women face cultural restrictions that limit their mobility. Cases of gender-based violence, such as sexual assault in informal employment, highlight the significant constraints imposed by patriarchy. For this dimension, we assign a score of 3 on the 1–5 scale (where 5 represents the greatest patriarchal influence). With regard to social networks, although women in Bhola develop solidarity groups and cooperatives, these are described as being limited in scope and often insufficient to counteract exclusion. Therefore, a moderate score of 2 is assigned on a scale of 1–5 (where 5 indicates strong social support), reflecting networks that are only partially effective. In terms of economic opportunities, around 80% of women engage in informal activities such as producing handicrafts. However, these activities perpetuate precarity and provide only limited economic security. Accordingly, a moderate-to-low score of 2 is assigned on a scale of 1–5 (where 5 indicates abundant opportunities), indicating scarce economic options.

3.1.3. Women’s Adaptive Strategies

Bangladesh demonstrates that, while urban migration can lead to conflict, it also creates opportunities for sociocultural negotiation. Although women face risks in the city, such as gender-based violence, labour exploitation and cultural restrictions on mobility, they manage to create spaces for resistance through solidarity networks and cooperatives, which function as mechanisms for negotiating with the established patriarchal order. Using a scale of 1–5 and the relational formula, Bhola calculates the following scores: climate exposure = 3; patriarchal norms = 3; social networks = 2; economic opportunities = 2. The calculation is (3 + 3) ÷ (2 + 2) = 6/4 = 1.5, indicating that the pressures clearly exceed the mitigating capacities and placing the case in a state of high vulnerability. This result coincides with findings documenting how female migration, even when it generates resilience, can lead to maladaptation processes that perpetuate exclusion and the risk of violence.

3.2. Central American Dry Corridor: Drought, Migration and Patriarchy

3.2.1. Regional Context and Climate Exposure

The Central American Dry Corridor, a strip of land covering parts of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, is home to more than 11 million people, many of whom rely on subsistence agriculture for their livelihood. The region is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events characterised by prolonged droughts interspersed with heavy rainfall, which are exacerbated by climate change and phenomena such as El Niño (Huber et al. 2023).

3.2.2. GVI Analysis and Comparative Findings

A thematic analysis focusing on the intersection between gendered vulnerability and adaptive strategies was conducted, integrating recent data and key factors such as climate exposure. Severe droughts and a 30–50% loss of glaciers in the last four decades have led to food insecurity and displacement (score: 4; Huber et al. (2023); WMO (2022); Almulhim et al. (2024)). Other factors include patriarchal norms restricting access to land and generating a high incidence of gender-based violence (score: 4; CEDAW (2018); Mijangos (2023)); moderate social networks limited by displacement despite the existence of cooperatives (score: 3; Tarrés et al. (2014); Andersen et al. (2017)); and restricted economic opportunities. This leads to dependence on informal activities due to limited access to formal employment and microfinance (score: 4; Rojas-Rendón and Franco (2024)).

According to Huber et al. (2023), the qualitative methodology involved conducting an interdisciplinary review of literature from the fields of agronomy, biology, economics, meteorology, political science and sociology. This revealed that women in the Central American Dry Corridor are vulnerable to a variety of issues, ranging from climate disasters such as prolonged droughts and hurricanes to urban risks such as gender-based violence and labour exploitation. For instance, climate pressures can significantly increase their workload, as they must care for their families while performing ‘traditional’ tasks such as agriculture. Unskilled young women migrate to cities to work in the textile industry, exacerbating their insecurities. ‘Climate pressures significantly increase women’s workloads as they must care for their families while also performing “traditional” tasks such as farming’ (Huber et al. 2023, p. 4). Pre-existing factors, such as insecure land tenure, particularly for women, undermine in situ climate adaptations. Around 60% of producers are smallholder farmers in rainfed systems, exacerbating food insecurity and promoting temporary or permanent migration.

Applying the relational formula: (4 + 4) ÷ (3 + 4) = 8/7 ≈ 1.14. This value indicates high vulnerability, albeit lower than in Bhola. The result shows that pressures are extreme in the Dry Corridor, but women have a slightly greater capacity to mitigate them through community networks or economic diversification, for example. However, this is still insufficient. A comparative analysis using the same metric reveals that both contexts exhibit high vulnerability for different structural reasons (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparisons with Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, the imbalance is greater because patriarchal and climatic pressures exceed the capacity for collective action available, intensifying the risk of exclusion and violence in urban environments where people first arrive. In the Dry Corridor, although the climate is extreme, emerging economic networks and strategies provide slightly greater scope for mitigation; however, these are not yet sufficient to counteract the deepening inequalities experienced during displacement. The social, economic, and cultural implications are profound. In both cases, migration reinforces gender hierarchies that restrict autonomy and access to resources. At the same time, however, it generates spaces in which women can negotiate new community roles, rebuild support networks, and create alternative livelihoods (Tarrés et al. 2014).

3.2.3. Policy Implications and Transferability

This relational approach offers two key analytical advantages for Latin America. Firstly, it enables us to measure the extent of vulnerability and the relationship between harmful and enabling forces, providing more precise guidance for policy design. Secondly, it facilitates the adoption of international best practice: For example, Bangladesh’s strategies based on women’s cooperatives, gender-focused microfinance and community participation could be implemented in the Dry Corridor if they were adapted to fit Latin American institutional frameworks. This would require accompanying cultural and legal transformations to address gender-based violence and political exclusion (Ahmed and Eklund 2021).

From an intersectional perspective, it is essential to understand the relationship between pressures and mitigation capacities in order to design responses that position women as agents of transformation, capable of rebuilding social fabrics, renegotiating patriarchal norms and leading processes of territorial resilience, rather than merely as victims of the climate crisis. To this end, Latin American states must adopt consistent measurement methodologies, such as the relational approach inspired by Smits and Huisman’s GVI, to ensure interventions are rigorously monitored and evaluated. This will prevent fragmented actions or policies that actually deepen vulnerability rather than reducing it.

Bangladesh’s political system, despite facing corruption challenges, operates under a parliamentary democracy that has enabled progress in climate adaptation policies and fostered community participation among women through cooperatives and NGOs (Khanom et al. 2022; Ahmed and Eklund 2021). By contrast, countries in the Dry Corridor (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica) have fragile democracies characterised by political instability and structural violence. Climate policies are limited by a lack of resources and coordination, as evidenced by the SICA Regional Action Plan for Climate Change (Mijangos 2023; Rojas 2024). Furthermore, female representation in decision-making is significantly lower in the Dry Corridor (20–30% compared to 35% in Bangladesh), which exacerbates the exclusion of displaced women.

In terms of climate, Bangladesh is exposed to cyclones, floods and riverbank erosion, with a moderate GVI score of 3. This is mitigated by early warning systems and adaptation measures such as dikes and shelters (Ahmed and Eklund 2021). In contrast, the Dry Corridor experiences prolonged droughts and agricultural land loss, with severe climate exposure (a GVI score of 4), exacerbated by phenomena such as El Niño. These events have caused agricultural losses of up to 60% (WMO 2022; Almulhim et al. 2024). These conditions generate greater food and water insecurity in the Dry Corridor, disproportionately affecting rural women who depend on agriculture for their livelihood.

Migration patterns differ too: in Bangladesh, migration is primarily from rural areas to cities such as Dhaka or Cox’s Bazar, where displaced women integrate through community networks, albeit under precarious conditions (Khanom et al. 2022). In the Dry Corridor, displacements are both internal and cross-border towards Mexico or the United States. There, they face legal barriers and risks of violence due to restrictive migration policies and the securitisation of borders (Murray-Tortarolo and Salgado 2021; CEDAW 2018).

The greater vulnerability in the Dry Corridor can also be explained by more restrictive patriarchal norms (a score of 4 compared to 3 in Bangladesh), which limit women’s access to land and expose them to high rates of gender-based violence. Indeed, 70% of women face legal barriers to land ownership (Mijangos 2023). In Bangladesh, social networks are stronger (a score of 2 compared to 3) thanks to well-established cooperatives and NGOs. In contrast, social fragmentation in the Dry Corridor limits community support (Tarrés et al. 2014; Andersen et al. 2017). Additionally, economic opportunities are more limited in the Dry Corridor (score of 4 compared to 2), with less access to microfinance and formal employment. This is in contrast to Bangladesh, where microcredit programmes such as those of the Grameen Bank are widespread (Rojas-Rendón and Franco 2024; Khanom et al. 2022).

To address these vulnerabilities, protection policies in the Dry Corridor could be adapted based on lessons learned in Bangladesh. For example, strengthening community networks inspired by women’s cooperatives in Bhola could promote climate-resilient agriculture and handicraft activities, supported by local NGOs and programmes such as the Alliance for the Dry Corridor (Andersen et al. 2017). Digital platforms, such as blockchain-based identities, could facilitate access to resources (World Economic Forum 2023). Secondly, microfinance programmes similar to those in Bangladesh could focus on green sectors such as agroecology, funded by the Green Climate Fund (2024). Thirdly, to combat gender-based violence, the establishment of safe shelters and mobile technology-based community alert systems is proposed, combined with educational campaigns integrating ancestral knowledge (Huyer et al. 2020). Finally, legal frameworks could be expanded to include the Escazú Agreement or introduce regional ‘climate visas’, ensuring safe mobility and access to services in line with global proposals (Cisneros et al. 2024; Madrigal 2021). By integrating intersectional approaches, these strategies could reduce GVI in the Dry Corridor by 20–30%, positioning women as key agents in climate resilience (Khanom et al. 2022).

4. Materials and Methods

This theoretical research employed a qualitative approach (Lim 2025), combining a systematic literature review (Ebidor and Ikhide 2024) with a case study (Priya 2020). Adopting a critical interpretative perspective (Elliott and Timulak 2021), the study problematises power structures and explores the intersection between gender, climate, and migration. This methodological complementarity highlights the complexity of the academic literature and the disproportionate effects evidenced in the case study. The framework adopts strategic universalism, recognising the situatedness of knowledge and the necessity of comparative analytics to identify transnational patterns of oppression. The GVI functions as a travelling concept that must be recalibrated to local contexts while maintaining analytical coherence across cases.

4.1. Epistemological Positioning

4.1.1. Constructivist–Critical Paradigm and Intersectional Feminist Framework

This research is based on the constructivist–critical paradigm (Lincoln and Guba 1985; Kincheloe and McLaren 2005). This paradigm views reality as a social construction shaped by power relations. It recognises that phenomena are not fixed or universal, but instead arise from contextual and subjective interactions. Three fundamental epistemological premises underpin this approach: (i) A relativist ontology, which holds that widespread climate displacement is not an objective and invariable phenomenon, but rather a social construction that varies according to specific historical and cultural contexts (Haraway 1988; Ozertugrul 2017); (ii) A subjectivist-transactional epistemology, in which knowledge arises from the dynamic interaction between the researcher and the texts or data. This acknowledges the impossibility of absolute evaluative neutrality (Harding 2004); and (iii) A hermeneutic-dialectical methodology, where understanding is built through iterative cycles of textual interpretation and confrontation of divergent theoretical perspectives. This fosters continuous dialogue between opposing ideas (Gadamer [1960] 1975; T. Butler 1998).

The justification for the intersectional feminist approach lies in its ability to integrate the feminist standpoint (Harding 2004) with intersectional analysis (Crenshaw 1989; Collins 2019). This approach recognises that the experiences of displaced Latin American women constitute a form of situated and epistemologically privileged knowledge about the structures of climate-patriarchal oppression. This knowledge cannot be reduced to isolated dimensions. Within this framework, vulnerability is not additive, but configurational, with gender, class, ethnicity and migratory status interacting to create unique matrices of domination. This reveals how these intersections shape specific oppressive realities, demanding a holistic analysis that transcends one-dimensional approaches (Collins 2019; Galdas 2017).

4.1.2. Epistemological Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

This approach carries the risk of gender essentialism (J. Butler 1990) and the reproduction of North–South binaries. To mitigate this, the analysis emphasises intra-group heterogeneity and transformative agency over victimization.

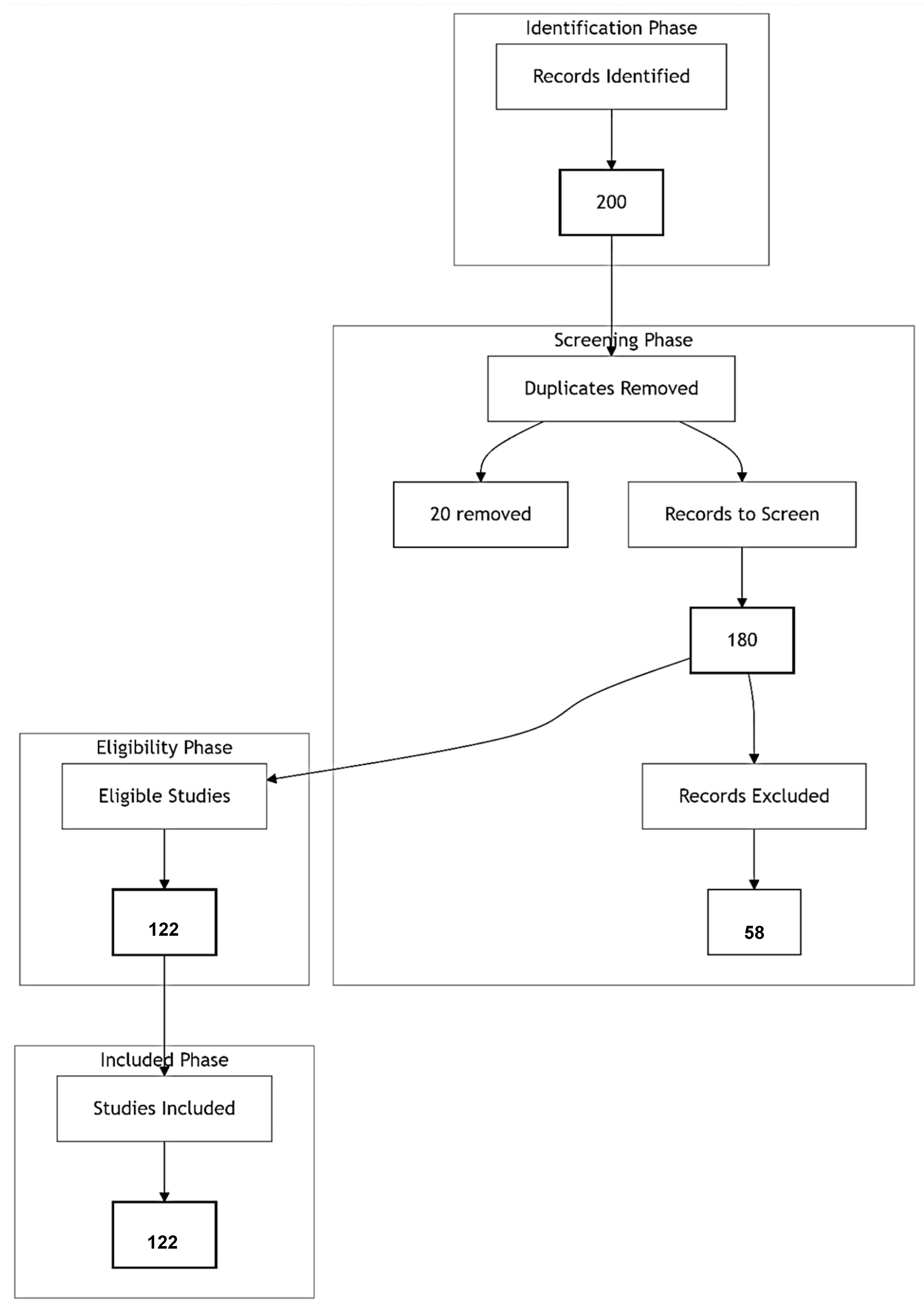

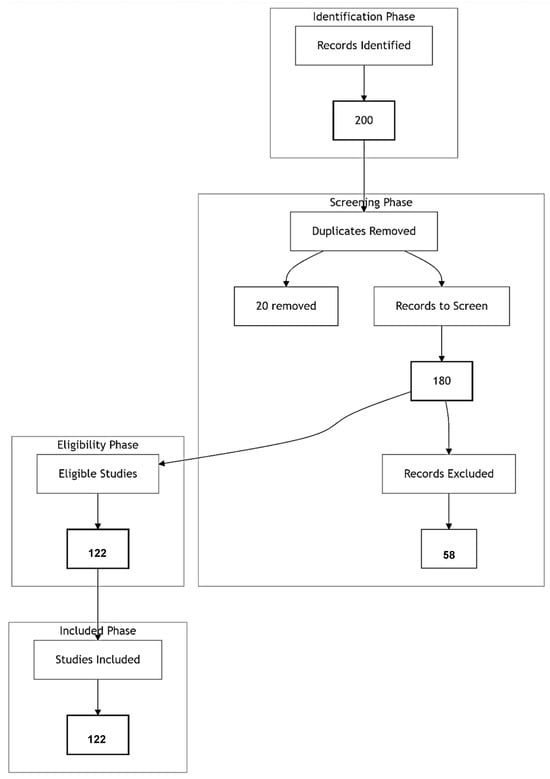

4.2. Systematic Literature Review: PRISMA Protocol

The systematic literature review adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, as adapted for qualitative and scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al. 2018). This process ensures rigour, transparency and reproducibility in the selection of evidence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the stages of the review process.

PRISMA process phases:

Identification: Searches were carried out in academic databases (SpringerLink, PubMed, PLOS, SAGE, MDPI, Oxford Academic, Cambridge Core and BMC) and on the websites of international organisations. Keywords included ‘gender’, ‘climate displacement’, ‘refugee women’, and ‘Latin America’. A total of 200 records were identified, after duplicates were excluded.

Screening: The inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed articles published between 2014 and 2025 that focused on the intersection of gender, climate and migration in Latin America or comparable contexts. Exclusion criteria included non-qualitative studies, irrelevant research and studies without open access. Of the 180 screened records, 58 were excluded.

Eligibility: A full review of 122 texts was conducted to assess quality and relevance, particularly with regard to differentiated vulnerability.

Inclusion: Ultimately, 122 documents were included in the thematic analysis.

4.3. Methodological Complementarity

In addition to the PRISMA protocol, the research design incorporated a complementary methodological framework comprising three interrelated phases: heuristics, hermeneutics and theorisation. This multi-layered approach ensured the rigorous and systematic integration of diverse forms of knowledge, maintaining a critical and interpretative perspective throughout the study.

Based on the three epistemological premises described above, the documentary analysis was structured on three levels: validation of sources, mapping of argumentative patterns, and generation of an interpretive meta-narrative through critical discourse analysis and feminist hermeneutics. The first premise is a relativist ontology, which recognises climate displacement as a context-dependent social construct influenced by historical and cultural specificities, rather than an objective and immutable phenomenon. The second premise is a subjectivist-transactional epistemology, which emerges through the interactive process between the researcher and the data and recognises the impossibility of absolute evaluative neutrality. The third premise is the hermeneutic-dialectical stance, which promotes iterative cycles of textual interpretation and theoretical dialogue to build understanding through confronting divergent perspectives.

5. Results

5.1. Literature Review Findings: Structural Patterns of Gendered Vulnerability

A systematic analysis of 122 academic and international policy documents, selected using an adapted PRISMA protocol (PRISMA-ScR), revealed consistent and statistically significant patterns concerning gender-based differential vulnerability in situations of climate-related displacement in Latin America. The review found that 77.9% of the documents identified patriarchal structures as the main obstacle to women’s adaptive capacity, highlighting specific mechanisms such as restricted mobility and exclusion from decision-making processes. Meanwhile, 64.8% of the studies emphasise the importance of female leadership in natural resource management and the preservation of traditional ecological knowledge. This shapes the concept of the ‘dual condition’ of women in the Anthropocene: they are the group most affected by environmental degradation, yet also the group most equipped with the knowledge to confront it. The geographical distribution of the studies reveals significant knowledge production gaps, with a clear focus on the Central American Dry Corridor, the Caribbean and the Amazon, while critical regions such as the Andes are underrepresented. This disparity suggests an epistemological bias that reproduces power asymmetries by prioritising areas with a greater presence of international cooperation projects.

The review identifies five recurring themes that structure the field of study. The first of these, present in 55.7% of the documents, is intersectionality. This examines how gender intersects with race, ethnicity, class and migratory status to produce specific matrices of vulnerability. The second axis, addressed in 42.6% of the studies, analyses legal and public policy aspects and identifies a ‘triple legal vulnerability’, whereby displaced women are not recognised as a protected category, face gender-based barriers to accessing justice and reside in countries with weak climate legislation from a gender perspective. The third axis, present in 38.5% of documents, focuses on the political economy of climate displacement. It demonstrates how extractivist economic systems and the commodification of natural resources act as underlying drivers that amplify the impacts of climate variability. The fourth axis, present in 32% of the studies, documents the resilience and adaptation strategies employed by women, such as solidarity economies, symbolic reterritorialisation and transnational advocacy networks. The fifth axis, present in 27.9% of the documents, addresses psychosocial and mental health aspects. It shows that forced displacement is a form of epistemic violence that uproots women’s bodies and their systems of meaning.

Building on this conceptual framework, the review identifies eight categories of gender-based differential vulnerability that manifest in an interrelated manner: (1) restricted mobility and limited access to information (59% of studies); (2) land tenure insecurity and economic exclusion (68%); (3) the disproportionate burden of reproductive and care work (54.1%); (4) increased exposure to gender-based violence (44.3%); (5) exclusion from decision-making processes (63.1%); (6) statistical invisibility and a lack of disaggregated data (33.6%); (7) barriers to accessing microfinance and adaptive resources (47.5%); (8) psychosocial impacts and loss of social capital (32%). This systematic characterisation provides the empirical foundation for the subsequent comparative analysis, demonstrating that these vulnerability dimensions represent transnational patterns which manifest in specific ways in each geographical context. Integrating these findings reveals a coherent conceptual architecture in the literature on climate displacement and gender in Latin America. This architecture is characterised by recognition of configurational vulnerability, critique of international legal frameworks, analysis of structural drivers, documentation of female agency and attention to the affective and psychosocial dimensions of displacement.

5.2. Comparative Case Study Results: GVI Analysis

A comparative analysis of Bhola District in Bangladesh and the Central American Dry Corridor utilises the relational Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI) to translate conceptual dimensions of vulnerability into measurable variables for systematic assessment. Qualitatively adapted from the methodological logic of Smits and Huisman, this index is based on four fundamental dimensions that capture the interaction between factors that increase and mitigate vulnerability. The first dimension is climate exposure, which is assessed based on the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, their measurable impact, and scientific projections. Due to its early warning systems and shelter infrastructure that partially mitigate the threat, Bhola, exposed to recurrent cyclones and flooding, receives a score of 3. In contrast, the Dry Corridor, which is affected by prolonged droughts and severe agricultural losses and has limited adaptation systems, receives a higher score of 4, reflecting more severe exposure and inadequate mitigation capacities. The second dimension, patriarchal norms, measures restrictions on women’s autonomy, mobility and access to resources. While Bhola still experiences mobility restrictions and high rates of gender-based violence, positive changes such as increased female labour participation and political representation quotas mitigate the impact, resulting in a score of 3. The Dry Corridor, however, exhibits a more entrenched and restrictive patriarchy due to extreme barriers to land tenure, endemic femicide, and the underrepresentation of women in decision-making processes. This justifies a score of 4. The third dimension evaluates social networks, i.e., the community support systems and social capital available. In Bhola, despite the presence of non-governmental organisations, the networks are limited and fragmented after displacement, warranting a score of 2. In the Dry Corridor, where there is a stronger historical tradition of community organisation and cooperativism, the networks are also weakened by migration and violence, resulting in a score of 3. The fourth dimension considers economic opportunities, such as access to livelihoods, microcredit and formal employment. In Bhola, the informal and precarious economy, in which displaced women are concentrated, is partially offset by relatively broad access to microcredit. This results in a score of 2. In the Dry Corridor, however, access to microfinance is significantly more limited. Formal opportunities are scarce and economic violence is common. This translates into a score of 4, indicating severe restrictions.

Using the relational GVI formula to divide the sum of pressures (climate exposure and patriarchal norms) by the sum of buffering resources (social networks and economic opportunities) yields indices that reveal distinct configurations of vulnerability. For Bhola, the calculation (3 + 3)/(2 + 2) = 1.50 indicates a pronounced imbalance, with moderately high pressures far exceeding weak buffering resources—a profile of ‘vulnerability due to weak buffers’. Despite advances in microcredit, this suggests that climate-displaced women are at high risk of maladaptation, resulting in exploitative informal employment and increased violence in urban contexts where they lose their support networks. For the Dry Corridor, however, the index (4 + 4)/(3 + 4) ≈ 1.14 reveals a paradox: although climatic and patriarchal pressures are objectively more intense, mitigation capacities, particularly historical social networks, are relatively stronger. Nevertheless, these buffers are insufficient, outlining a profile of ‘vulnerability due to the intensity of pressures’, where risks such as the total collapse of subsistence means and extreme violence overwhelm adaptive capacities.

This comparison highlights the need for effective interventions to be contextualised. In Bangladesh, the priority is to strengthen the buffers by consolidating urban social networks and improving the quality of economic opportunities beyond microcredit. In the Dry Corridor, actions must focus on reducing extreme pressures through adaptive infrastructure and reforms to transform patriarchy and violence, as well as on consolidating existing buffers, such as community networks. The analysis shows that there is no one-size-fits-all solution: the specific configuration of each context determines which dimensions must be prioritised to significantly reduce the vulnerability of climate-displaced women.

5.3. Integration: Addressing the Research Question

This study was organised around the following central question: what factors influence the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Latin American women facing forced climate displacement, and what strategies have they developed to confront it? Integrating a systematic literature review with a comparative case analysis using the Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI) provides a structured, empirically grounded response. Vulnerability emerges from the complex interplay of social, economic and cultural factors that act in tandem, rather than in isolation.

Socially, structural patriarchy is manifested through gender roles that disproportionately burden women with unpaid reproductive labour, such as water provision and care, which intensifies dramatically during climate crises. This structure limits women’s mobility, excludes them from decision-making spaces and normalises gender-based violence as a control mechanism. This is all exacerbated by institutional invisibility, which omits disaggregated data and designs adaptation policies that take women’s unlimited time for granted. Economically, vulnerability is anchored in profound land tenure insecurity: rural women own less than 18% of agricultural land due to historical legal biases and cultural norms. This prevents them from accessing credit, disaster compensation and an economic safety net, forcing them to migrate in desperation rather than dignity. Their concentration in the informal and precarious economy, in sectors such as care work, textiles, and petty trade, leaves them without social protection and with minimal income. Another often-overlooked issue is the loss of intangible assets, such as territory-specific ecological knowledge. For many older indigenous women, this constitutes a form of epistemic impoverishment, eroding their identity and social status. Culturally, ethnic discrimination and structural racism result in triple marginalisation for indigenous and Afro-descendant women, who are excluded on the basis of their gender, ethnicity, and status as displaced persons. Furthermore, gender-specific territorial attachments, whereby female identity and spiritual practices are tied to the land, mean that displacement is an experience of epistemic violence and profound uprooting. Meanwhile, climatic stress intensifies traditional norms of masculinity, often resulting in an increase in intimate partner violence as a compensatory mechanism for the loss of the provider role.

When confronted with this matrix of oppressive configurations, displaced women are not passive victims, but active agents who deploy a variety of strategies to resist and adapt. They establish solidarity economies through cooperatives and savings groups, providing relative economic autonomy and functioning as spaces for socialisation and cultural preservation. They engage in symbolic reterritorialisation by recreating urban gardens and domestic rituals that maintain connections to their homelands and pass on knowledge to the next generation in urban environments. Politically, they establish transnational advocacy networks to amplify their voices in international forums, contesting legal frameworks and demanding recognition as ‘climate refugees’ in order to highlight the structural causes of their displacement and challenge the neutrality of international law.

For Latin American women, the experience of climate displacement is defined by this fundamental dialectic: vulnerability deeply rooted in the intersection of patriarchal, colonial and economic power; and the capacity for transformative agency exercised in constructing community, cultural and political alternatives. Recognising this tension is crucial in order to avoid both the victimisation that treats women as helpless and the uncritical celebration of resilience that shifts state responsibility onto their shoulders. Feminist climate justice therefore demands a dual commitment: dismantling the structural systems that generate vulnerability, while simultaneously supporting and amplifying the alternatives that women are already creating within those systems.

6. Discussion

6.1. Intersectionality and the Climate Refugee Debate

Intersectionality in women’s studies has gained visibility in the environmental debate, recognising women’s historical role in resource management and adaptation to climate change (Davis and Shaw 2001). However, an uncritical perspective can reinforce gender stereotypes and place a disproportionate burden on women to solve the climate crisis (Turquet et al. 2023; Pinho-Gomes and Woodward 2024). This narrative needs to be analysed in light of the differentiated vulnerabilities women face due to structural inequalities and access barriers in contexts of institutional fragility. While the category of climate refugee makes a critical situation visible (Toaquiza 2024), it lacks international legal recognition (UNHCR 2001), which limits its usefulness for effective rights protection (Sussman 2023). Initiatives such as ‘climate labs’ (Johri 2023) or blockchain-based digital identity systems (World Economic Forum 2023) may represent innovative advances, but if they do not address structural inequalities, they risk replicating exclusionary power dynamics. Proposals such as adaptive hybrid communities (Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship 2024) also offer promising avenues, provided that women are actively involved in their design and governance as a counterweight to patriarchal structures (Carter 2015).

6.2. Bangladesh as Comparative Reference: Possibilities and Limits

The case of Bangladesh (Khanom et al. 2022) offers valuable lessons, but also highlights limitations in the direct transferability of solutions to contexts such as Latin America. The resilience of displaced women, while remarkable, should not substitute for the responsibility of states to guarantee rights, nor should it romanticise traditional knowledge without assessing its applicability in contemporary urban contexts. The discourse on women’s empowerment in climate action must be accompanied by an analysis of the power structures that perpetuate inequality (Ripple et al. 2024). While women’s participation in decision-making is essential, focusing solely on gender solutions can distract from the systemic changes needed in governance, economics and energy policy (Du 2024).

In Latin America, there has been significant progress in the legal recognition of climate change. Ecuador has constitutionalised the right to protection from its effects (Toaquiza 2024), and archaeological evidence in Peru shows that women played a central role in ancient climatic migrations (Shady 2006a, 2006b). Other countries have enacted legislation: Mexico, with its General Law on Climate Change; Colombia, through laws and decrees linking climate change and land use planning (Madrigal 2021); and Costa Rica, with its ambitious Decarbonisation Plan 2018–2050. Chile enacted its Framework Law on Climate Change in 2022; Argentina, its National Plan with a gender perspective (Moraga 2022); while Brazil, despite its national policy, faces questions about weak implementation (de Figueiredo Machado et al. 2024). This convergence between contemporary policy frameworks and historical evidence highlights the persistence of climate challenges in Latin America and the evolution of social and legal responses. However, there is still a need to strengthen protection policies with intersectional, participatory and transformative approaches to ensure climate and gender justice in the region.

6.3. The Latin American Legal Framework for the Protection of Climate-Displaced Persons: Gender Analysis

Although Latin America has developed pioneering regulatory instruments for the protection of persons displaced by disasters, the integration of gender in these instruments is uneven and, in many cases, insufficient to address differentiated vulnerabilities. The 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees is notable at the regional level, as it broadens the definition of refugee to include those who flee due to circumstances that have seriously disrupted public order. This has been applied to natural disasters through the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; however, the declaration lacks specific gender provisions, which limits its ability to respond to structural inequalities that disproportionately affect women (Morera and Biderbost 2023). Similarly, the 2018 Escazú Agreement, which came into force in 2021, establishes the right of access to environmental information with a focus on vulnerable groups (Article 4.5). However, its impact is limited by the lack of ratification in key countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and Chile. Furthermore, it fails to disaggregate vulnerabilities by gender in critical areas such as early warning mechanisms and adaptive planning, resulting in gaps in comprehensive protection (Madrigal 2021).

Progress in comparative national legislation varies significantly between countries, reflecting different levels of gender integration and focus on climate displacement. Ecuador’s 2008 Constitution (Articles 14 and 414) is notable for recognising the right to a healthy environment and promoting ecosystem restoration. It incorporates specific protections for displaced pregnant women (Article 70) and links environmental security with human security by prohibiting weapons of mass destruction (Article 423). This represents a high degree of integration with an eco-centric approach and explicit attention to women in contexts of climate mobility (Toaquiza 2024). Mexico’s General Law on Climate Change, amended in 2023, incorporates tools such as the National Risk Atlas for identifying vulnerable areas (Articles 28–29) and promotes gender equality in climate policy (Article 8). However, it falls short in terms of implementing protections for displaced persons and ensuring access to climate justice, resulting in a medium level of effectiveness (CEDAW 2018). Colombia, for its part, is making progress with Law 1523 of 2012 and Decree 1974 of 2021, which focus on preventive risk management. This is complemented by Resolution 1672 of 2018, which establishes protocols for providing differentiated care to women in emergencies. Despite the disconnect between climate policies and those aimed at victims of armed conflict, Colombia achieves a medium-high level of effectiveness.

6.3.1. Regional Instruments and Their Gender Gaps

Brazil lags behind in this area. Its 2009 National Policy on Climate Change is based on the principles of precaution and participation. However, it makes no explicit reference to gender or displacement. Its 2016 National Adaptation Plan also omits gender indicators. This results in a low level of intersectional integration and a generic approach that does not address deep inequalities (de Figueiredo Machado et al. 2024). By contrast, Argentina has made progress through Law 27,520 of 2019 and its 2022 National Plan. These initiatives establish a National Climate Change Cabinet with a territorial focus and include a section dedicated to ‘Gender and Climate Change’, offering green microcredit to rural women. This approach achieves a medium-high level of integration through cross-cutting integration and targeted financial tools. Meanwhile, Chile’s Framework Law 21,455 (2022) incorporates the principles of gender equality (Article 2) and informed citizen participation (Article 5). This is further reinforced by the disproportionate impact of climate change on women. They represent 80% of those displaced by such events (van Daalen et al. 2024). This highlights the urgent need for them to participate equally in climate dialogue to ensure their voices influence effective policies. This highlights Chile’s high level of integration, thanks to its binding quotas in climate governance (Moraga 2022).

6.3.2. Comparative National Legislation Analysis

Despite these advances, significant gaps remain that hinder an effective, gender-sensitive response to climate displacement. Firstly, there is a lack of cross-border mobility, as no country offers ‘climate visas’ or other specific humanitarian admission schemes for environmental migrants, leaving vulnerable populations without safe legal pathways (Mijangos 2023). Secondly, protection and restitution are not coordinated with climate laws or refugee legislation, such as Ecuador’s 2017 Organic Law on Human Mobility or Colombia’s Law 1448 of 2011. This prevents comprehensive redress for displaced women who face multiple forms of discrimination (Rojas-Rendón and Franco 2024). Thirdly, the lack of gender-based indicators is notable: only Chile and Argentina define metrics for female participation, but neither monitors gender-based violence in contexts of climate displacement. This limits the evaluation and adjustment of policies (CEDAW 2018).