Abstract

Velopharyngeal insufficiency may occur as a result of an anatomical or structural defect and may be present in patients with cleft lip and palate. The treatment options presented in the literature are varied, covering invasive and non-invasive methods. However, although these approaches have been employed and their outcomes reviewed, no conclusions have been made about which approach is the gold-standard. This umbrella review aimed to synthesize the current literature regarding velopharyngeal insufficiency treatments in cleft lip and palate patients, evaluating their effectiveness based on systematic reviews. A standardized search was carried out in several electronic databases, namely PubMed via Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Embase. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using AMSTAR2 and degree of overlap was analyzed using Corrected Covered Area. Thirteen articles were included in the qualitative review, with only 1 in the non-invasive method category, and 12 in the invasive method category. All reviewed articles were judged to be of low quality. In symptomatic patients, treatment did not solely comprise speech therapy, as surgical intervention was often necessary. Although there was no surgical technique considered to be the gold standard for the correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency, the Furlow Z-plasty technique and minimal incision palatopharyngoplasty were the best among reported techniques.

1. Introduction

Cleft lip and palate (CLP) are one of the most common congenital anomalies with a global prevalence of 1:700 [1]. This condition is characterized by the lack of fusion in facial structures, which usually occurs between the 5th and 10th weeks of pregnancy [2]. There is no single cause for this congenital anomaly, and it is thought to have multifactorial etiology [2,3]. Some risky behaviors during pregnancy are known to predispose the fetus to this condition, such as alcohol and tobacco consumption, anti-epileptic drugs or corticosteroids, and inadequate nutrition [2,3]. Additionally, people of low socioeconomic status have been reported to have a higher prevalence of orofacial clefts [2].

After primary bone graft surgery, around 20 to 50% of patients develop velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) [4]. Some factors are considered to increase risk for VPI, such as being of the male sex and having a shorter palate length or a wider cleft [5].

VPI can be described as the insufficient closure between the soft palate and the posterior wall of the pharynx [6,7,8]. This condition occurs in open cleft palates, submucosa, or CLPs that were surgically closed, but remained low or immobile due to the remaining scar tissue or irregular palate muscle positioning [6,9]. The main methods used to diagnose VPI are through auditory-perceptive evaluations and video naso-endoscopies [8].

In regular circumstances, the velopharyngeal valve is made up of lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls and the soft palate. When this valve closes, it divides the oral cavity and the nasal cavity. This can be observed in many instances, such as when an individual is swallowing, speaking, or breathing [9]. However, in CLP patients that present palatal muscle debilitation, there is no velopharyngeal closure during phonation, which leads to air and acoustic energy being emitted by the nasal cavity [5,10]. This results in a hypernasal speech pattern, nasal air emission, compensatory articulation, and nasal regurgitation [5,7,8,9,10].

The initial approach for VPI treatment involves speech therapy. Nonetheless, open surgery may be required in certain cases, such as cases with structural issues, a subpar speech therapy response, serious VPI, a low palate, or inadequate mobility [7,9,10]. Speech therapy can be used in both pre- and post-surgical stages. However, when it comes to VPI surgery, there is no predetermined timing nor a standardized surgical protocol [9,10]. The most common surgical procedures for VPI treatment include a pharyngeal graft or sphincter pharyngoplasty, which can reach a normal resonance of 76 and 61%, respectively [3,4,9]. Although both of these techniques are highly effective, they also present a risk of developing obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which ranges from 19 to 93% [3,4,11]. Taking this into account, palatoplasty has emerged as an alternative with a lower risk for developing OSA [3,4]. This procedure is performed with a straight incision into the palatal mucosa or a double-opposing Z-plasty, also known as a Furlow palatoplasty [4]. Despite having an 82% success rate and not compromising the upper airway, this technique is not broadly used [3,4]. In patients with moderate VPI, autologous or synthetic implantable materials, such as cartilage, fat, or silicone, have been used to augment the posterior pharynx wall [9,10,11]. Besides the conventional surgical treatments for VPI in patients with CLP, there are also prosthetic options, such as speech bulbs or palatal lifts, that can aid in velopharyngeal closure [12].

The current literature comprises several systematic reviews that attempt to homogenize results (which remain fickle), especially when it concerns the best surgical techniques and most appropriate timing for intervention. However, no conclusions have been made about which treatment is the gold-standard. Notwithstanding, the fundamental goal of any treatment is to restore patient loss of function and form. VPI may lead to functional problems in swallowing, speaking, and breathing. Biomimetics aim to study the phenomena and processes of nature in order to understand them, and then use and modify these mechanisms; nothing is more biomimetic than the materials and techniques used to restore normal tissue function to the patient. This umbrella review aimed to access the clinical effectiveness of VPI treatments that restore the loss of structure and function by mimicking the normal appearance, form, and function of healthy human tissue using Bioinspired, biomedical, and biomolecular tissue engineering strategies and materials. Therefore, this umbrella review aims to answer the following research question: “What are the most effective treatments for velopharyngeal insufficiency in cleft palate patients?”

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

This review was registered with the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) under the ID number: CRD42022287414. This review was carried out in accordance with the guidelines recommended by Cochrane and PRISMA for systematic reviews.

2.2. PICO Question

The research question aimed to answer the clinical question: What is the most effective methodology to resolve velopharyngeal dysfunction in cleft palate patients?

The question was formulated according to the PICO principles, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICO question.

2.3. Search Strategy

A standardized search was carried out in June 2022 in several electronic databases, such as PubMed via Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Embase. The search keys are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Search keys in various databases.

A search of articles in the grey literature was also carried out using the websites ProQuest (https://www.proquest.com, accessed on 20 June 2022) and OpenGrey Europe (https://opengrey.eu, accessed on 20 June 2022). Other relevant cross-references were also considered.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were established according to the PICO question above. All systematic reviews with and without meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials, non-randomized clinical trials, and case-control studies that analyzed the resolution of velopharyngeal dysfunction through various invasive and non-invasive methods were included. Only studies that evaluated the resolution of velopharyngeal dysfunction through the assessment of hypernasality were included. Studies that included literature reviews, case reports, or case series were excluded.

2.5. Study Selection and Data Collection

The search and studies selection were performed by two investigators (R.T. and C.N.). The studies were all selected by title or abstract according to the defined eligibility criteria, by the two researchers. In the event of disagreement, a third investigator (I.F.) assessed and resolved eligibility. After being selected for full reading and inclusion in the umbrella review, the authors extracted the following data: author and year, registration in Prospero, type of studies included in the systematic reviews, analysis of their bias and quality of evidence, age of participants, type of intervention performed, comparison group, primary outcome, and main and significant results. These results were summarized.

2.6. Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the AMSTAR2 tool (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews Checklists, accessed on 6 July 2022). This checklist contains several questions about the systematic reviews being evaluated to assess the quality of each one. This quality assessment was performed by two investigators (F.M. and A.P.) independently and in duplicate. Another three investigators (M.R., F.P., and C.M.M.) independently assessed the quality of the studies, and in case of disagreement with the initial evaluation, this point was discussed, and an agreement was reached by the five evaluators. The studies were classified as: high quality, in the case of zero to one weak parameters; moderate quality, in case of more than one weak parameter; and low quality, in cases where several parameters were weak.

2.7. Analysis of the Degree of Overlap in Studies

The analysis of the degree of overlap of selected studies between systematic reviews was performed through “Corrected Covered Area” (CCA). The overall overlap was categorized as slight (CCA = 0–5), moderate (CCA = 6–10), high (CCA = 11–15), and very high (CCA > 15).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

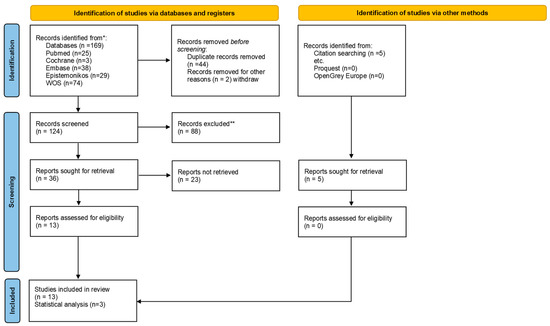

The selection scheme (flow chart) for this umbrella review is shown in Figure 1. The initial search in the different databases resulted in 169 articles, without additional documents from the grey literature, but with 5 articles included by manual searching. After removing duplicates, 124 articles were left for screening. Reading by title and abstract resulted in 36 articles for full reading because they met the eligibility criteria. Thirteen articles were included in the final qualitative review, with only 1 in the non-invasive category and 12 in the invasive method category.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of umbrella review.

3.2. Description of the Included Reviews

Of the articles included in the qualitative analysis, 1 had a non-invasive method (Table 3), whereas the remaining 12 had invasive methods (Table 4). The non-invasive method was nasopharyngoscopy biofeedback, and it was evaluated in 1 systematic review. The primary evaluated outcomes were activation of lateral pharyngeal wall, velopharyngeal closure in articulation, reduction of hypernasality, nasal emission or nasal turbulence, and improvement of articulation or intelligibility in connected speech. This systematic review showed that there were no studies measuring the effectiveness of nasopharyngoscopy biofeedback without additional treatments like secondary surgery or speech-language therapy; therefore, this non-invasive method was shown to be effective only in combination with conventional speech therapy.

Table 3.

Non-invasive methods.

Table 4.

Invasive methods.

Invasive methods were evaluated in 9 systematic reviews and 3 systematic reviews with meta-analyses. These articles compared various interventions, namely, minimal palatopharyngoplasty with or without additional individualized velopharyngeal surgery, cleft palate repair surgical techniques, injection pharyngoplasty, pharyngeal flap surgery, and adenoidectomy. Cleft palate repair surgical techniques included Furlow double-opposing Z-plasty, straight-line intravelar veloplasty, and radical intravelar veloplasty alone or in combination with mucosal lengthening. The injection pharyngoplasty was made with autologous fat, GAX collagen, calcium hydroxyapatite, dextranomer, hyaluronic acid, and acellular dermal matrix. The resolution of velopharyngeal dysfunction was assessed in most articles through speech and hypernasality evaluation and assessing velopharyngeal gap size at rest and closure using videofluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and nasometry.

3.3. Quantitative Synthesis of the Results

Quantitative synthesis of the results was not possible due to heterogeneity in design and methodologies of the selected studies as well as a distinct comparison of treatments.

3.4. Quality of Included Reviews

Table 5 presents the quality assessments of the selected systematic reviews. Only two reviews clearly described the PICO question because most studies failed to name a comparator group. Successful registration was carried out by one review and partially in five others. Most of the included studies, except one, failed to explain their selection process. The search was not fully explained in any review. Three studies did not perform data selection and extraction of duplicates. The list of excluded studies wasn’t presented in any review. A description of selected studies was given in adequate detail in only one study, and partially done in eight other reviews. Assessing risk of bias was not performed in six reviews. No reviews reported the funding of included studies. Ten systematic reviews did not present a meta-analysis. Most reviews discuss the heterogeneity observed in the results, except for three. No studies included an assessment of publication bias. Half of the reviews reported potential conflicts of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review. Overall, according to the AMSTAR 2 tool criteria, all reviews were considered to be of low quality.

Table 5.

Quality assessment of the included reviews, using the AMSTAR2 tool.

3.5. Analysis of the Degree of Overlap in Studies

The 13 systematic reviews included 270 studies, of which 43 overlapped in two or more systematic reviews (Table 6). The CCA was 0.0158 (1.58% overlap). This signifies a slight overlap, meaning that a small number of studies are cited several times across the included reviews. Notwithstanding, only three of the included systematic reviews did not have overlap. Although it was expected that the most recent reviews would present a higher number of overlaps, we did not find a relationship between the year of publication and overlap number.

Table 6.

Citation matrix for duplicate primary studies.

4. Discussion

This umbrella review aimed to synthesize the current literature regarding velopharyngeal insufficiency in cleft patients, evaluating their effectiveness based on systematic reviews with and without meta-analyses.

Velopharyngeal insufficiency may occur because of an anatomical or structural defect that results from incomplete closure between the soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall, resulting in an opening between the oral and nasal cavities [17]. This pathology may be present in patients with cleft lip and palate, and is characterized by difficulty swallowing, hypernasality, and difficulty in speech articulation, which ultimately results in a lower quality of life [7,11]. In these cases, the main goal of treatment is to restore nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal function, allowing for improved speech articulation [12]. The treatment options presented in the literature are varied, including invasive and non-invasive methods depending on the severity of the insufficiency. These include speech and swallowing therapy, prosthesis placement, palatoplasty, pharyngoplasty, muscle repositioning, and posterior pharyngeal wall enlargement procedures, such as injection augmentation pharyngoplasty (IPA) [7,12,13]. Regarding non-invasive methods, speech therapy is the most referenced method. This treatment entails long and continuous follow-up, which may contribute to exhaustion and decreased collaboration. This may explain why only one systematic review included in this study addressed speech therapy.

In symptomatic patients, treatment does not solely comprised speech therapy, as surgical intervention is often necessary [7]. Although there is no surgical technique considered to be the gold standard for the correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency, the Furlow Z-plasty technique, minimal incision palatopharyngoplasty (MIPP), and other modified versions of these procedures were the best techniques reported [12]. Nevertheless, the clinician should recognize the risks associated with these interventions, such as the development of obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hemorrhage and infection [4,7,12]. Teblick et al. also concluded that this surgical technique was associated with a lower prevalence of otitis media with effusion and lower number of ear tubes needed [19]. In the included systematic reviews, the Furlow Z-plasty technique was the most referenced form of treatment in 8 of the 13 publications evaluating invasive methods [3,4,9,14,15,17,19,20]. However, only one study was found to report statistically significant differences between the Furlow Z-plasty technique and the straight-line intravelar veloplasty closure approach, with a lower re-intervention rate of 0–11.4% vs. 0–6.7%, respectively [14]. These results should be interpreted with caution as this study was of overall low quality, namely due to the lack of independently collected data, an adequate protocol, and any considerations of the risk of bias. The remaining reviews did not present differences between several surgical techniques, but these conclusions may also have some bias, because the included studies had high clinical and methodological heterogeneity, specifically in sample size, cleft phenotype, methods used to assess speech and velopharyngeal incompetence, surgeon experience, and inclusion of syndromic patients. This heterogeneity may also affect the results of the present umbrella review and made it impossible for some SR results to be used for the meta-analysis. Overall, there appears to be no surgical technique considered to be the gold standard.

This umbrella review provides an overview of the available systematic reviews. The methodological quality of the included studies was later assessed, allowing readers to interpret the results with caution, as most studies were of low quality and did not follow a registered protocol with transparent methodology. However, this umbrella review had some limitations, such as the overall low quality of the included studies. These low-quality articles presented similar characteristics, including: lacking a clear PICO question, no list of excluded studies, no description of funding of included studies, and no assessment of the ROB effect on the statistical combination and publication bias. Additionally, most of the included studies did not include a protocol record, which may increase the occurrence of methodological flaws as well as bias. Six of the included reviews did not assess the quality of the included studies, which may also be associated with an increase in bias, as this parameter could not be used in the interpretation of the results. Furthermore, nine of the included studies did not perform a meta-analysis, which may also increase the risk of bias. Finally, the difficulties faced by investigators in conducting blind trials in the surgical field may lead to an overestimation of the treatment effects, because knowledge of the outcome may have affected the clinicians’ experiences.

Future studies should be conducted using a blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) protocol to control sources of possible bias, namely through a randomization procedure and standardization of the intervention, use of control groups, intervention timing, measurement tools, and follow-up timing. In future RCTs, authors should look to the Medical Research Council guidance for developing and evaluating surgical interventions. This guide states that the trial team must recognize all the constituent components and steps of each intervention. In this sense, it may be convenient to carry out a pilot study before the RCT study to ensure that the clinical team can systematically identify all the steps of the intervention. Despite the steep learning curve that could affect the outcome, there are some strategies that could be adopted in future studies to minimize this factor, including randomizing patients according to surgeon rather than by intervention and performing statistical tests to assess the interference of the learning curve. The aim is to improve treatment efficacy and patient quality of life whilst reducing the need for retreatments and associated costs.

5. Conclusions

Velopharyngeal insufficiency treatment usually comprised speech therapy and surgical intervention. Although there is no surgical technique considered to be the gold standard, the Furlow Z-plasty technique and minimal incision palatopharyngoplasty were among the best reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.V. and I.F.; methodology, C.M.M. and A.B.P.; software, F.M. and M.P.R.; formal analysis, A.B.P., F.P., and F.P.; resources, C.M.M.; data curation, R.T., F.P., and C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T., C.N., and M.P.R.; writing—review and editing, I.F. and A.B.P.; visualization, E.C.; supervision, F.V.; funding acquisition, F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Crockett, D.J.; Goudy, S.L. Cleft lip and palate. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 22, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloukos, D.; Fudalej, P.; Sequeira-Byron, P.; Katsaros, C. Maxillary distraction osteogenesis versus orthognathic surgery for cleft lip and palate patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 9, CD010403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilleard, O.; Sell, D.; Ghanem, A.M.; Tavsanoglu, Y.; Birch, M.; Sommerlad, B. Submucous cleft palate: A systematic review of surgical management based on perceptual and instrumental analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2014, 51, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurnik, N.M.; Weidler, E.M.; Lien, K.M.; Cordero, K.N.; Williams, J.L.; Temkit, M.H.; Beals, S.P.; Singh, D.J.; Sitzman, T.J. The Effectiveness of Palate Re-Repair for Treating Velopharyngeal Insufficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2020, 57, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainsbury, D.; Williams, C.; de Blacam, C.; Mullen, J.; Chadha, A.; Wren, Y.; Hodgkinson, P. Non-Interventional Factors Influencing Velopharyngeal Function for Speech in Initial Cleft Palate Repair: A Systematic Review Protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, P.H.H.; Costa, F.W.G.; Cetira Filho, E.L.; Silva, P.G.B.; Albuquerque, A.F.M.; Leão, J.C. Effect of maxillary advancement on speech and velopharyngeal function of patients with cleft palate: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.; Cowan, K.; Marston, A.P. Metanalysis of alloplastic materials versus autologous fat for injection augmentation pharyngoplasty treatment of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 146, 10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paniagua, L.M.; Signorini, A.V.; da Costa, S.S.; Martins Collares, M.V.; Dornelles, S. Velopharyngeal dysfunction: A systematic review of major instrumental and auditory-perceptual assessments. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 17, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Blacam, C.; Smith, S.; Orr, D. Surgery for velopharyngeal dysfunction: A systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2018, 55, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, J.O.; Kilpatrick, N.; Morgan, A.T. Speech and language characteristics in individuals with nonsyndromic submucous cleft palate—A systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigh, E.; Rubio, G.A.; Hillam, J.; Armstrong, M.; Debs, L.; Thaller, S.R. Autologous fat injection for treatment of velopharyngeal insufficiency. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, M.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Newton, T.; Nouri, M. Interventions for the management of submucous cleft palate. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 1, CD006703. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, S.; Romonath, R. Effectiveness of nasopharyngoscopic biofeedback in clients with cleft palate speech: A systematic review. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2012, 37, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timbang, M.R.; Gharb, B.B.; Rampazzo, A.; Papay, F.; Zins, J.; Doumit, G. A systematic review comparing furlow double-opposing Z-plasty and straight-line intravelar veloplasty methods of Cleft palate repair. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 134, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossell-Perry, P.; Romero-Narvaez, C.; Olivencia-Flores, C.; Marca-Ticona, R.; Anaya, M.H.; Cordova, J.P.; Luque-Tipula, M. Effect of Nonradical Intravelar Veloplasty in Patients with Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate: A Comparative Study and Systematic Review. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 1999–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenssler, A.; Perry, J. The Effectiveness of the Buccal Myomucosal Flap on Speech and Surgical Outcomes in Cleft Palate: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 2020, 8, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Salna, I.; Jervis-Bardy, J.; Wabnitz, D.; Rees, G.; Psaltis, A.; Johnson, A. Partial adenoidectomy in patients with palatal abnormalities. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, E454–E460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.; Cheung, K.; Farrokhyar, F.; Strumas, N. Pharyngeal flap versus sphincter pharyngoplasty for the treatment of velopharyngeal insufficiency: A meta-analysis. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2012, 65, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téblick, S.; Ruymaekers, M.; van de Casteele, E.; Nadjmi, N. Effect of Cleft Palate Closure Technique on Speech and Middle Ear Outcome: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 77, 405.e1–405.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruijt, N.E.; ReijmanHinze, J.; Hens, G.; Poorten, V.V.; Van Der Molen, A.B.M. In search of the optimal surgical treatment for velopharyngeal dysfunction in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).