Abstract

A swarm intelligence optimization algorithm called white shark optimizer (WSO) has been proposed and successfully applied in regard to many aspects. In this paper, the location problem of sports facilities is regarded as a multi-objective problem, and the number of residents covered by sports facilities and the Weber problem are introduced as objective functions. A multi-objective white shark optimizer (MOWSO) is proposed, and MOWSO introduced an archived mechanism to store the non-dominated solutions obtained by the algorithm. When the Pareto solutions in the archive overflow, the solutions are removed by calculating the true distance of the Pareto optimal solution. The performance of the MOWSO is verified on CEC 2020 benchmark functions, and the results show that the proposed MOWSO is better than other algorithms in the diversity and distribution of solutions. The MOWSO is applied to solve the rural sports facilities location problem, and a variety of different sports facilities location schemes are obtained. It can provide a variety of options for the location of rural sports facilities, and promote the intelligent design of sports facilities.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates that humans can promote physical health and develop a healthy lifestyle through appropriate physical exercise, but progress is slow at present [1]. With rapid urbanization, China faces problems of obesity and a lack of physical exercise. Therefore, how sports are promoted in China is gaining people’s attention more and more [2]. One of the core aspects of China’s sports policy is to build a viable environment to promote people’s participation in sports activities in a way that is consistent with the health-promotion strategy advocated by the World Health Organization [3]. Compared with developed countries, the average level of sports facilities in China is relatively backward. Compared with the city, the average level of rural sports facilities has an obvious lag, and the number is small, unable to meet the needs of the majority of residents for physical exercise, which has become one of the factors restricting the physical fitness training of villagers. The above situation can be improved by promoting the process of rural sports development, and the construction of rural sports facilities is the key to promoting the development of rural sports. The state promotes the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy by increasing the capital investment in the construction of rural sports facilities. In the process of the construction of rural sports facilities, how to choose the right location for the construction of rural sports facilities is one of the key problems in the construction of rural sports facilities. The construction of sports facilities can promote the physical exercise of rural residents, improve the physical fitness of residents, contribute to the sustainable development of rural areas, and promote the implementation of rural revitalization strategies. Based on the classical continuous location model, this paper constructs a multi-objective location model of rural sports facilities from the perspectives of fairness and efficiency.

Over the past few decades, different meta-heuristic algorithms have been developed to handle these complex optimization problems, such as differential evolution (DE) [4,5,6,7], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [8,9,10,11], flower pollination algorithm (FA) [12], ant colony optimization (ACO) [13,14], sine cosine algorithm (SCA) [15,16], gray wolf optimization (GWO) [17,18,19], Tianji’s horse racing optimization (THRO) [20], the Divine Religions Algorithm (DRA) [21], and Stellar oscillation optimizer (SOO) [22], etc. It is proven that the metaheuristic algorithm has important application value. In academia and industry, these algorithms are widely used to solve various types of optimization problems. Because of their simple principle and easy implementation, these algorithms have attracted more and more attention. Unlike traditional methods to solve optimization problems, metaheuristic algorithms do not need to analyze objective functions and constraints, which is the most significant advantage of metaheuristic algorithms. In general, a metaheuristic algorithm starts with a random set and then searches globally for the best solution according to the set rules. These rules often mimic the laws of natural evolution, the laws of human behavior [23], the social behavior of birds, insects, and other organisms [24,25], the laws of plant growth [26], mathematical planning [27], and the laws of physics [28,29], etc. The literature review is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature review of metaheuristic algorithms.

Multi-objective optimization is a common problem in all fields. In multi-objective problems, each objective will not reach the optimal solution at the same time. It is important to find multiple sets of solutions for multi-objective problems because different solutions can be applied to decision-makers with different needs. In recent years, many meta-heuristic algorithms have been successfully applied to multi-objective optimization problems. One of the very classic and popular multi-objective algorithms is multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) [30]. In MOPSO, the optimal Pareto solution is selected by external archiving and the adaptive grid mechanism. K. Deb improved NSGA by introducing fast elite non-dominated sorting to obtain NSGA-II [31,32]. The algorithm proposes a fast non-dominated ranking to improve the population level. In addition, crowding ranking and elite selection strategies are introduced. There are other classical multi-objective algorithms, such as SPEA2 [33] and Omni-optimizer [34], etc. In addition, there are some excellent multi-objective algorithms, such as DN-NSGAII, MO_Ring_ MO_Ring_PSO_SCD, MOHHO, MOFOA, MaODA, DPDCA, and so on [35,36,37,38,39]. These multi-objective algorithms can solve multi-objective optimization problems well. A new swarm intelligence optimization algorithm called white shark optimizer (WSO) was proposed by Malik B. et al. in 2022 [40]. Inspired by the great white shark’s search for food and tracking of prey in the deep sea, it combines the great white shark’s keen hearing and smell abilities with fish behavior. Based on the mathematical modeling of great-white-shark hunting behavior, the great-white-shark population can search through random search, locate the behavior of prey and fish, and search in the search space, so as to update position and finally achieve the purpose of searching for the best. At present, the white shark optimizer algorithm has been applied to some optimization problems and has achieved good results [41,42,43,44,45,46]. In this paper, the white shark optimizer is improved to the multi-objective white shark optimizer (MOWSO) to solve the multi-objective problem.

The following is a summary of the principal achievements:

- (1)

- A novel multi-objective white shark optimizer (MOWSO) is proposed;

- (2)

- The archived mechanism is introduced in MOWSO to store the current Pareto optimal solution, and it is screened by calculating the true distance of the Pareto optimal solution;

- (3)

- The performance is tested and compared to MOWSO on CEC2020 benchmark functions;

- (4)

- A novel rural sports-facilities location problem model is proposed;

- (5)

- We used MOWSO to solve the rural sports-facilities location problem and obtained the best result.

The rest of this article is divided into four parts. Section 2 is the introduction of the white shark optimizer algorithm and location problem. In Section 3, the multi-objective problem is introduced, and the multi-objective white shark optimizer algorithm is designed. Section 4 evaluates the performance of the multi-objective white shark optimizer algorithm on the test set. Section 5 introduces the rural sports-facility location model and uses the white shark algorithm to solve it. Section 6 is the summary of this paper and future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. White Shark Optimizer

The white shark is one of the most ferocious and dangerous predators in the ocean. It has powerful muscles, keen eyesight, and a keen sense of smell. When searching for prey, great white sharks first use their hearing to scout large spaces. Second, they can find prey by using their keen sense of smell. These features help them explore nearby areas. Great white sharks can use two lines on their sides to detect changes in water pressure and thus find the direction of prey movement. Great white sharks sense changes in pressure in the ocean and move toward prey. They can also sense the weak electromagnetic field generated by the movement of prey. When locating prey, the great white shark moves toward it in a fluctuating motion. The algorithm is divided into three parts: speed of movement towards prey, movement towards optimal prey, and clustering behavior of fish.

2.1.1. Movement Speed Towards Prey

White sharks spend most of their time hunting and tracking prey. They track their prey in a variety of ways, using their superior sensory abilities like hearing, sight, and smell. When white sharks sense the location of their prey based on the hesitation of the waves they hear as the prey moves, they move toward the prey in an undulating manner. This mode of motion can be defined as shown in Equation (1).

where represents the speed of the -th white shark to step in the white-shark population. represent the contraction factor, which is used to analyze the convergence behavior of great white sharks, and its definition is shown in Equation (5). is the -th indicator vector when the white shark searches for the best prey, and its definition is shown in Equation (2). and are used to control the influence coefficients of and on , and their calculation methods are shown in Equations (3) and (4), respectively. is the global optimal position obtained by the white shark in the first k searches so far in the search process, is the optimal position corresponding to the -th white shark in the population in the k iterations, and is the position of the -th white shark in the population at the k searches. and are randomly generated numbers between 0 and 1. represents the -th white shark in the white-shark population.

where is a uniformly distributed random number generated in the range of 0 to 1.

where k and K, respectively, represent the number of iterations and the maximum number of iterations of the white-shark population so far. and are two fixed values set empirically, 0.5 and 1.5, respectively, in order to control the and values in combination with the number of iterations.

where represents the coefficient of acceleration, thorough analysis results in a value of 4.125.

2.1.2. Movement Towards Optimal Prey

White sharks are constantly shifting their position, and when they hear waves from prey movement or smell prey, they move closer to their prey. The location of the prey changes as it searches for food or the white shark moves towards it. However, the prey will leave some scent in the previous location. In this case, white sharks can search for prey based on the scent they left behind. This behavior of the white shark can be described in Equation (6).

where represent the latest position of the -th white shark in the population after the (k + 1) iteration, indicates a logical non-operation, and are binary vectors whose formulas are Equations (7) and (8), and and represent the upper and lower bounds of the entire search space, respectively. represents a logical vector calculated by Equation (9), and represents the frequency of the wave motion of the white shark, and the formula is represented by Equation (10). represents a random number between 0 and 1, and represents the motion force of a white shark approaching prey, which increases with the number of iterations and which is calculated by Equation (11).

where stands for the XOR operation.

where and represent the maximum and minimum frequency of the great white shark’s fluctuating movement, respectively. By conducting a large number of experimental tests, and were finally selected as 0.75 and 0.07, respectively.

where and are constants used to manage exploration and exploitation capabilities. Typically, the values are 6.25 and 100.

2.1.3. The Swarming Behavior of White Sharks

When great white sharks hunt, they cooperate and move toward the white shark closest to their prey. This behavior is represented by Equation (12).

The is the -th update of the position of the white shark relative to prey. The value is 1 or −1, indicating the search direction. , , and represent random numbers between 0 and 1. is the distance between the white shark and its prey, calculated by Equation (13). represents the olfactory- and visual-intensity parameters of a great white shark following other great whites approaching prey, as calculated by Equation (14).

where is a random number between 0 and 1.

where is a constant, and through extensive experimental analysis, the value has been taken as 0.0005.

White sharks are highly social animals that prefer to hunt in groups. The fish behavior of white sharks is represented by Equation (15)

where is a random number between 0 and 1. White sharks can update their location based on the nearest white shark to their prey.

2.2. Continuous Facility Location

There are many kinds of location problems, which exist in different disciplines, and different disciplines have different descriptions of location problems. However, according to the description of a location problem from different disciplines, the most essential definition of a location problem is given a metric space and the location of demand points in the space, and the location of new facilities in the space, a certain goal between facility points and demand points (generally called customers) can be optimized. This problem has an important position in real life. For more than half a century, with the development of mathematical tools, such as the introduction of optimization techniques to the problem of facility location, the field has entered a period of flourishing. People have conducted in-depth research into and analysis of facility-location problems in different fields, established optimization models and studied theoretical properties, proposed effective numerical algorithms to solve the models, and used the research results to solve practical problems.

The study of location problems spans numerous research fields such as management, engineering, geography, economics, computer science, and mathematics, etc. Its typical application is the location of factories, warehouses, hospitals, retail stores, and in addition, it is also used in fire centers, fire stations, gas stations, exploration oil wells, missile warehouses, and so on. From the perspective of decision makers, site selection is of great significance. Facility location has been accompanied by the development of human history; it has an important and profound impact on human life and production activities.

The rural location problem can be classified in different ways. According to the topology of the metric space, the location problem can be divided into discrete location, continuous location, and network location. Discrete location is the location of a given series of discrete points in the metric space. Continuous siting has a long history. New facilities in continuous siting can be located in a continuous region of the metric space. Continuous optimization, such as linear and nonlinear programming, can be used to solve the continuous siting problem. Network location is the location of the vertex or edge of a given graph or network, which is solved by combinatorial optimization and integer programming. Discrete location, continuous location, and network location have important applications in real life, which can be used to solve practical problems in different situations. The following are several key elements in continuous facility siting: the number of new facilities, the distance metric function, and the objective function, etc.

2.2.1. Number of Facilities

In the facility-location problem, the number of new facilities can be one facility point or multiple facility points. According to the different number of facility points, the problem of facility location can be divided into single-facility location and multi-facility location. In general, the need to locate multiple facilities is more difficult than the need to locate only one facility. This is because in the multi-facility location problem, it is necessary to consider to which facility point the customer goes to obtain the service, or the fact that, in some cases, a particular amount of service is required by the customer, but the amount of service provided by the facility cannot meet the conditions.

2.2.2. Distance Metric Function

There are various distance measurement functions in the field of location selection. One of the important distance measurement functions is the norm. It satisfies positive definiteness, homogeneity, and subadditivity, and its measured distance reflects the actual distance more truly. The LP-norm is a distance metric commonly used in continuous siting. When p = 1, this norm measures the L1-distance, which is often used to represent the distance between two points in a city. When p = 2, this norm measures the Euclidean distance, which represents the straight-line distance between two points. The distance measured by this norm when p = ∞ is often referred to as the Chebyshev distance. Some generalized LP-norms are also commonly used to measure the distance between a facility and a customer. When customers in the location of continuous facilities occupy a large range in the metric space, they should not be simply regarded as points but as regions. The distance between the facility and the customer becomes the distance between the point and the area.

2.2.3. Correlation Function of Location Problem

According to different objectives, the functions of facility location can be roughly divided into pull objectives, push objectives, and push-and-pull objectives [42,43]. When the facility is of the type desired by the demand point (such as a supermarket, bank, fire station, etc.), the demand point always wants the facility as close to it as possible. Therefore, pull goals are often used, such as minimizing the distance between the demand point and the facility and maximizing market share. When the facility belongs to the type that is excluded by the demand point (such as polluting factories, garbage disposal stations, etc.), the demand point wants the facility to be as far away from itself as possible. Push goals are often used, such as maximizing the sum of distances between customers and facility points, minimizing the number of customers covered by the facility, and so on. In some cases, the type of facilities is between expectation and exclusion, and there will be two contradictory or opposite factors in the problem of attraction and exclusion. This kind of location problem often adopts push–pull goals.

The minisum function is a commonly used pull target to minimize the distance between the facility and the customer. The corresponding location problem is called the minisum problem. The Weber problem is the minisum problem, where the number of facilities is one. The problem with more than one facility is called the multi-facility minisum problem, which includes two kinds of important problems: the multi-facility Weber problem and the multi-source Weber problem. The minimax function is another commonly used pull goal that minimizes the maximum distance between the client and the setup, and the corresponding model is called the minimax problem. Because the model focuses on the farthest customers, it reflects fairness to some extent. The coverage problem is also an important problem in the use of pull targets, and the coverage problem includes two types of problems: maximum coverage and minimum coverage. The former is to make facilities cover as many customers as possible when the number of facilities is given, while the latter is to cover all customers with the least facilities when the number of facilities is variable. Problems such as locating a point on the network to maximize its weighted distance to the node are called maxisum problems [47]. Like pull targets, the maxisum and maximin functions are two important types of push targets. The maxisum problem seeks to maximize the distance between the customer and the facility, while maximin seeks to maximize the closest distance between the customer and the facility. When the number of facilities is more than one, the multi-facility model of the push target can be divided into max–min–min, max–min–sum, max–sum–min, and max–sum–sum, etc., in which min/sum of the third layer represents the minimum distance or distance sum between a given customer and all facilities. Because of the attraction and repulsion of push–pull targets, the location problem of push–pull targets can be modeled as two-objective optimization. Therefore, the method and technology of double objective optimization can be effectively used to solve the location problem of push–pull targets.

3. Multi-Objective White Shark Optimizer

3.1. Multi-Objective Optimization Problems

Multi-objective optimization is a common problem in real life, which refers to the realization of multiple objectives under certain circumstances. However, in a multi-objective problem, each object contradicts each other, and when one object tends to the optimal value, the value of the other object may be weakened. That is, all the objects in the multi-objective problem cannot obtain the optimal solution at the same time. Solving this problem usually involves finding a balance between multiple goals, making compromises, and making each goal as relatively optimal as possible. The multi-objective optimization problem can be expressed by the following formula [48].

where represents the number of objective functions, and represent the number of inequality constraints and equality constraints, respectively, and represents the number of independent variables. are the upper and lower bounds of the -th variable.

The concept of Pareto optimality is widely used in the search of multi-objective optimization algorithms. Pareto optimality is an ideal situation for resource allocation. Pareto improvement is a change from one allocation state to another, assuming that there are fixed units and resources that can be allocated, without reducing the resources allocated to any unit, so that the resources allocated to another unit are increased. Pareto optimality means that there are no more Pareto improvements. Here are some concepts and terms about Pareto optimality.

Pareto domination: If and are two solutions to a multi-objective optimization problem, performs no worse than on any objective function, and performs better than on some objective function, is said to be Pareto superior to .

Pareto optimal solution: When there is no solution that dominates , the solution to is a Pareto optimal solution.

Pareto optimal solution set: The set of all Pareto solutions is called the Pareto solution set, to wit,

Pareto optimal frontier: The Pareto frontier is formed when all the Pareto optimal solutions are mapped by the objective function.

3.2. The Proposed Method

The white shark optimizer algorithm can be improved by introducing two components into the multi-objective white shark optimizer algorithm. The first component is the Pareto archive, which holds the best Pareto solutions found so far [30]. The archive has rules for storing and deleting Pareto solutions, and compares the newly generated Pareto solutions with those existing in the archive to determine whether the newly generated solutions are better than the ones in the archive. When the new solution is superior to the existing solution in the archive, the new solution is not dominated by other solutions, and the new solution is stored in the archive; otherwise the new solution is discarded.

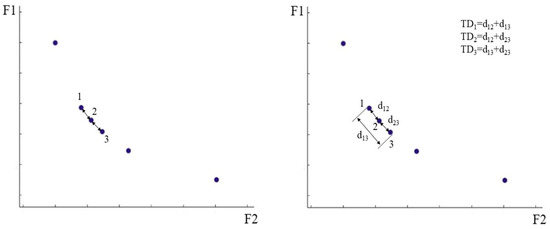

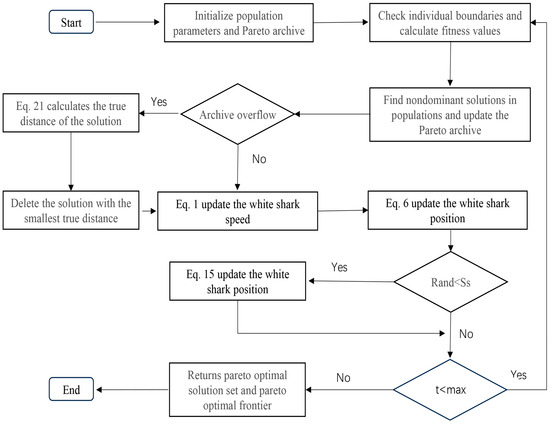

When the number of solutions in the archive reaches the maximum capacity of the archive, some solutions in the archive need to be deleted to make the solution set distributed more evenly. The second component is introduced at this point. The component deletes the solution according to the true distance between the solution sets. Since the solutions in the archive are all Pareto optimal solutions, it is necessary to delete some densely distributed solutions to make the distribution of solutions more uniform. In this case, the distance of each solution to its nearest solution is calculated, and then the solution with the smaller distance is preferentially deleted, but there will be cases where the minimum distance of several solutions is equal. At this point we calculate the distance between these solutions and the other closest solutions, and add these distances until we can identify the solution that needs to be specifically deleted, which we call the true distance (TD). As shown in Figure 1, when the minimum distance of solution 1, solution 2 and solution 3 is almost equal, we can calculate the true distance of each solution and delete the solution more conveniently. The calculation formulas are shown in Equations (21) and (22). As the algorithm runs, solutions with smaller true distances are removed in turn according to the second component. In addition, MOWSO guides other individuals towards the individual by selecting the one with the greatest true distance in the current archive. This method can lead the search for the optimal Pareto solution of the population, and can ensure the convergence and diversity of understanding. The flow chart of MOWSO is shown in Figure 2.

where represents the number of objective functions and N represents the number of Pareto solutions. represents the value of one set of solutions, and represents the value of the -th set of solutions. represents the index of the smaller value in .

Figure 1.

The true distance of the solution.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the MOWSO.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

All algorithms in this experiment were programmed in MATLAB R2021b and numerical experiments were performed on an AMD Ryzen 7 6800H processor with 32 GB of memory. The proposed MOWSO algorithm is compared with other classical multi-objective algorithms to evaluate its effectiveness. It includes popular multi-objective optimization algorithms NSGAII [31] and SPEA2 [33], the multi-objective particle swarm algorithm (MOPSO) [30], the generic evolutionary algorithm (Omni-optimizer) [34], and the decision space base niching NSGAII (DN-NSGAII) [32]. MOPSO was proposed by Coello C. et al. The algorithm mainly uses the archive controller and adaptive grid mechanism. DN-NSGAII is modified from NSGAII. It embeds niche techniques in mating and environmental selection schemes. Omni-optimizer is designed to solve different types of optimization problems including single-objective, multi-objective, single-modal and multimodal problems. Unlike these multi-objective algorithms, MOWSO selects the Pareto solution set based on the true distance of the solution set. When archive files overflow, the solution with the smallest true distance in the solution set is deleted. These strategies can improve the performance of the MOWSO algorithm, and can solve multi-objective problems well.

4.2. Evaluation Index

In this paper, the performance of MOWSO and other comparison algorithms is evaluated by using four different evaluation indexes from decision space and target space. In the decision space, Pareto Sets Proximity (PSP) [49] and Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) [50] are used, respectively. In objective space, Hypervolume (HV) is used [51], and IGD is used in objective space (IGDF) [52]. The larger the PSP and HV, the better the algorithm performance; the smaller the IGDX and IGDF, the better the algorithm performance. In order to unify, 1/PSP and 1/HV are used to evaluate the performance of the algorithm. The smaller the value of 1/PSP and 1/HV, the better the performance of the algorithm.

Pareto Sets Proximity (PSP) reflects the similarity between the true Pareto solution set (PSs) and the PSs obtained by the algorithm.

where CR represents the coverage rate of the optimal solution set obtained by the solution to the reference solution set. The calculation formula is as follows.

where is the dimension of the decision space, and where and are the maximum and minimum values of the PSs obtained by the algorithm on the variable. and are, respectively, the maximum and minimum values of the true PSs obtained by the algorithm in the variable.

The index IGDX is used to judge the diversity and convergence distribution of the solution obtained by the algorithm [53]. IGDX is calculated according to the Euclidean distance between the solution obtained by the algorithm and the reference solution, which is publicized as follows:

where is the true PSs and represents the solution obtained by the algorithm. represents the solution to the minimum Euclidean distance between the set and . The IGD index can also be found using the Pareto front (PF), so that the convergence distribution of the solution in the target space can be obtained. The calculation formula of IGDF is the same as that of IGDX, except that the space is different.

In the objective space, the reciprocal of the hyper volume is also an important index, and its calculation formula is as follows:

HV can measure and evaluate the convergence and diversity of the resulting solutions.

4.3. Experimental Result

In this paper, the performance of MOWSO was tested used CEC 2020 multi-modal multi-objective optimization benchmark functions. CEC 2020 contains 24 test functions, including different types of Pareto optimal frontiers, such as convex, concave, linear, non-linear, and disconnected. For each function, all algorithms were run independently 20 times, and the results were counted, choosing the mean and standard deviation to compare the algorithms. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 shows the comparison between MOWSO and other multi-objective algorithms for the mean and standard deviation of the four indicators. Table 2 shows the 1/PSP index of different algorithms, from which it can be seen that MOWSO can find the optimal value in 14 functions, whether it is mean or standard deviation, and outperforms other algorithms. And in the other five functions, the optimal value of the mean can be found. This suggests that the Photoshop obtained by MOWSO is more like real Photoshop. For IGDX indicators, it can be seen from Table 3 that MOWSO can find the optimal value of the mean value in all 19 functions, and the performance is better than other algorithms. For the IGDF index, it can be seen from Table 4 that MOWSO can find the optimal value in 10 functions, no matter the mean value or standard deviation, and it performs better than other algorithms. And in the other eight functions, the optimal value of the mean can be found. For the index of 1/HV, MOWSO performs poorly. As can be seen from Table 5, MOWSO only finds the optimal value of mean or standard deviation in seven functions, and performs worse than several of them. In summary, the MOWSO algorithm performs better than the other five algorithms.

Table 2.

The mean and standard deviation of 1/PSP obtained by running the algorithm 20 times.

Table 3.

The mean and standard deviation of IGDX obtained by running the algorithm 20 times.

Table 4.

The mean and standard deviation of IGDF obtained by running the algorithm 20 times.

Table 5.

The mean and standard deviation of 1/HV obtained by running the algorithm 20 times.

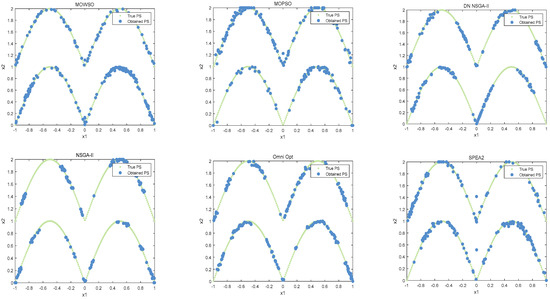

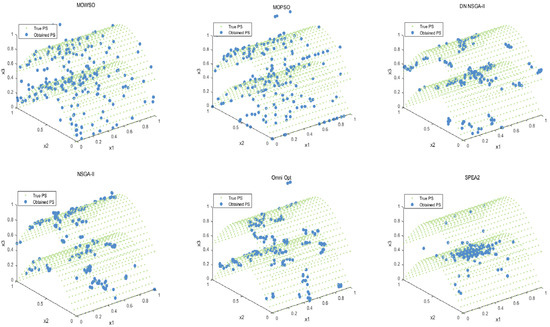

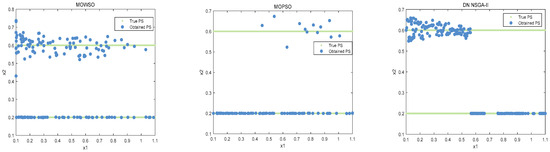

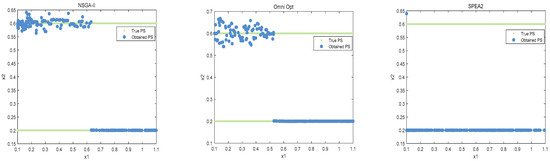

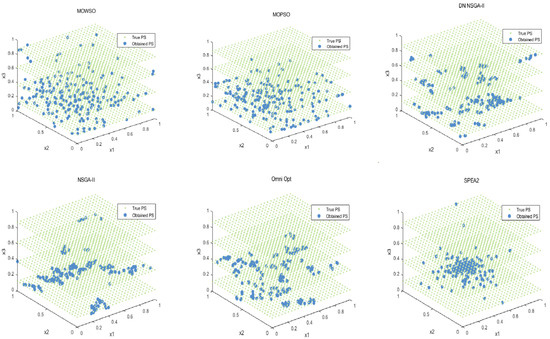

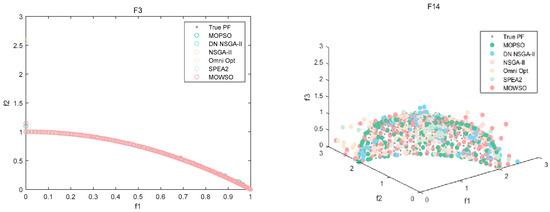

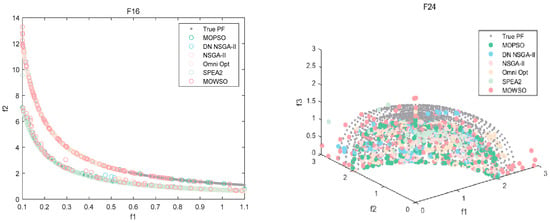

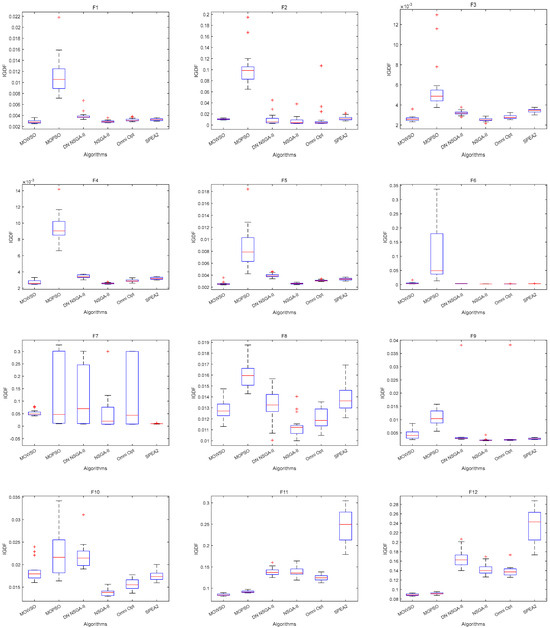

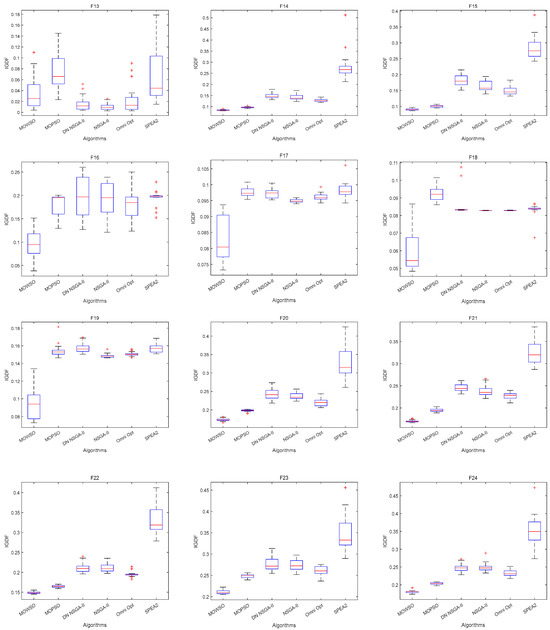

The best results of PSs and PF were obtained by running each algorithm 20 times in functions F3, F14, F16 and F24. This is shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. The number of dimensions and objective functions of the functions F3 and F16 is two, and the number of dimensions and objective functions of F14 and F24 is three [54]. As can be seen from Figure 3, the solution-set distribution obtained by the MOWSO algorithm on function F3 is more uniform; among the six functions, the solution set distribution of NSGA-II is more disorderly and the number of solutions obtained is less. As can be seen from Figure 4, on function F14, the MOWSO algorithm performs well, while SPEA2 obtains a poor distribution of solution sets. Figure 5 shows that on function F16, the solution set obtained by MOWSO is significantly better than the other five algorithms, and the solution-set distribution is more uniform than that obtained by the other five algorithms. As you can see from Figure 6, MOWSO also performs well on function F24. In Figure 7, it can be seen that the Pareto front obtained by MOWSO algorithm is widely distributed and uniform, indicating that the MOWSO algorithm is not easily trapped in local optimization when searching for solutions in the global. This paper presents drawings of the boxplot of IGDF on each function of different algorithms. The boxplot can display the distribution of data obtained by different algorithms intuitively. The box plot of the algorithm on the IGDF index is shown in Figure 8. It can be seen from the figure that MOWSO has the smallest upper and lower edges, upper and lower quartiles, and median on most functions compared with the other five algorithms. These results show that MOWSO performs stably and with minimal fluctuations on CEC 2020, and can reach optimal values compared to other algorithms.

Figure 3.

The Pareto set obtained by all algorithms on F3 (MMF4).

Figure 4.

The Pareto set obtained by all algorithms on F14 (MMF14_a).

Figure 5.

The Pareto set obtained by all algorithms on F16 (MMF10_l).

Figure 6.

The Pareto set obtained by all algorithms on F24 (MMF16_l3).

Figure 7.

Pareto front of all algorithms on four functions.

Figure 8.

Comparison results (IGDF) of the box plot on CEC 2020 test functions.

Friedman rank can be used to compare the overall performance of different algorithms on data sets. In this paper, the performance of six algorithms on CEC 2020 was evaluated through a Friedman rank test experiment. The Friedman test obtains the average score and average ranking of each algorithm, thereby ranking the performance of the algorithm. Table 6 shows the results of the Friedman rank test for each algorithm. MOWSO’s overall ranking is No. 1. This proves the performance benefits of MOWSO.

Table 6.

Friedman rank test.

5. Rural Sports-Facility Location Problem

5.1. The Objective Function of Sports-Facilities Location

In the location of traditional sports facilities, designers analyze various constraints, and constantly optimize and adjust the location scheme. Using the algorithm to solve this problem not only improves work efficiency and saves human resources, but also provides a new idea and method for the location and layout of sports facilities. When solving the location problem of sports facilities in real life, since sports facilities and villages occupy a relatively small area in the whole space, sports facilities (hereinafter referred to as facility points) and villages (hereinafter referred to as customers) are regarded as a point in the plane. According to the concept of a 15 min living circle, customers are required to walk 15 min to reach the location of the facility point. With the normal speed of 1.5 m/s as the standard, the effective service radius of the facility point is set to 1350 m. For the customer, the facility point is somewhere between expectation and exclusion. Customers not only want to be able to reach the facility point in a short time, but also because the facility point will bring certain congestion or other unfavorable factors, so customers do not want the facility point to be too close to them. Considering the maximum utilization of the facility point, it is hoped that there will be large number of customers within the effective coverage area of the facility point. This section introduces three objective functions in the continuous location of sports facilities. These objective functions are based on the classical model of a continuous facility location, and on this basis, is combined with practical problems to improve the objective functions.

The purpose of the classic multi-source Weber problem (MSWP) is to find the location of new facilities and minimize the sum of transportation costs between these new facilities and all customers. According to the customer’s hope to reach the service point in a short time, MSWP is selected as the first objective function. The mathematical model of this problem is as follows:

where is the number of new facilities that need to be located. represents the position coordinate of the -th facility point in the sought facility point. represents the number of customers in the space. represents the location coordinates of the -th customer. indicates the weight between and . is to calculate the Euclidean distance between two points.

In this model, each facility can provide enough services to customers in the target space, so that each customer can choose the nearest facility point to obtain services, thus minimizing the cost of the system. To avoid resource waste caused by too close a distance between sites’ selected points, constraints are added to the model, that is, the distance between two facility points should be greater than the minimum distance . The model was adopted as the first objective function F1 of the sports-facility location problem. Finally, MSWP is equivalent to

In order to avoid the waste of resources, more customers should exist within the effective coverage area of the facility, so that the facility can serve more customers. When there is a facility point within 1350 m from the customer, that is, the customer can reach the facility point within 15 min, it means that the customer is covered by the facility point. To enable more customers to be covered, the second objective function F2 uses a mathematical model as follows:

Here, indicates that the customer has a facility point within a range of , which ensures that the customer can walk to the facility point within 15 min. is the number of customers.

Because the facilities will bring certain congestion or other adverse factors, customers want to be relatively far away from the facilities. Based on this, the distance of all customers to their nearest facility point is calculated. The customer closest to the facility point among all customers is expected to have the greatest distance from the facility point. Therefore, the third objective function F3 uses the Maximin model, as shown below:

where represents the number of facility and represents the location of the -th facility point. is the number of customers and is the location of the -th customer. is the Euclidean distance. represents the minimum distance between two facility points.

5.2. Simulation Experiment Results

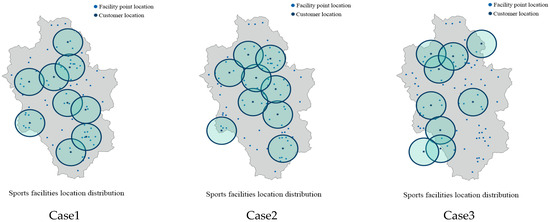

This experiment uses a real case study, which is located in a township in Guangxi Province, China. ArcGIS was used to extract the village point coordinates of the township and it regarded them as customers, as shown in Figure 9. The number of customers involved in this case is 76, and the area of customers is about 120 square kilometers. A single sports facility has a service radius of 1350 m and covers an area of about 5.7 square kilometers. Considering the scattered distribution of customers, the number of experimental facilities in this experiment is nine facilities, and the number of facilities can be changed according to the actual situation. The problem is a multi-objective problem where F1 is the sum of the distances between all customers and the facility (SDCF), as shown in Equation (30). F2 is the number of customers covered by the sports facilities (NCCF), as shown in Equation (31). F3 is the distance between the nearest customer and the sports facility (DCCF), as shown in Equation (32).

Figure 9.

Case location and village distribution map.

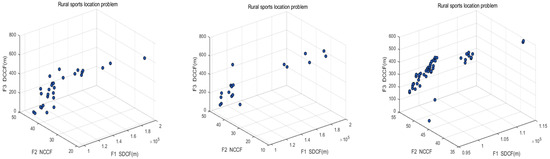

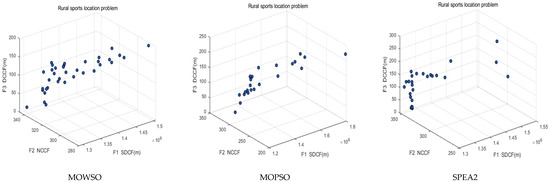

The initial population of the MOWSO algorithm was set to 50 and the number of iterations to 100. Other MOWSO parameters are shown in Table 7. According to the three objective function models, MOWSO was used to solve the problem, and MOPSO and SPEA2 were compared. Finally, the location information of the facility point was obtained. The specific information of the results obtained by the three algorithms in each objective function is shown in Table 8. The Pareto frontier obtained by the solution is shown in Figure 10. From the Pareto front of the algorithm, it can be seen that the function values obtained by MOWSO are evenly distributed, which indicates that the MOWSO algorithm can provide more comprehensive and extensive reference information for the location problem of sports facilities and also proves the effectiveness of MOWSO algorithm.

Table 7.

Setting of algorithm parameters.

Table 8.

Partial Pareto optimal solution.

Figure 10.

Location of sports facilities on the Pareto front.

The specific information when MOWSO solves the location problem of sports facilities and obtains the best value in each objective function is shown in Table 9, and the specific location is shown in Figure 11. In the first case in the figure, the sum of the distances that all customers need to walk to reach the facility point is the minimum. At this time, the number of customers within the effective coverage of the facility is 42, and the distance between the customers closest to the sports facility and the facility is 84 m. In the second case, the number of customers within the effective coverage of the facility is the largest. At this time, all customers need to walk 112,556 m to reach the facility point, and the distance between the customers who are closest to the sports facility and the facility is 43 m. The third case is that the distance between the customers closest to the sports facilities and the facilities reaches the maximum. At this time, all customers need to walk 184,416 m to reach the facilities, and the number of customers within the effective coverage of the facilities is 19.

Table 9.

Pareto optimal solution obtained by MOWSO.

Figure 11.

MOWSO obtained the distribution of sports facilities.

In order to verify the effectiveness of MOWSO in the location of sports facilities on a larger scale, 800 customer points were randomly generated in an area of 1225 square kilometers. The service radius of a single sports facility is 1350 m, covering an area of about 5.7 square kilometers, and the number of sports facilities is 100 to conduct experiments. According to the three objective function models, MOWSO was used to solve the problem, and MOPSO and SPEA2 were compared. The three algorithms were run separately ten times. Table 10 shows the average value of the optimal value obtained by the algorithm after ten times running on the three objective functions. F1 represents the sum of the distance that all customers need to travel to reach the facility point, in kilometers. F2 represents the number of customers within the effective coverage area of the facility. F3 is the distance between the nearest customer and the facility, in meters.

Table 10.

The algorithm obtains the value of the objective function.

The distribution of the solution was evaluated using the indices SP and UD, which are the diversity indices proposed by Schott and Tan et al. to measure the distribution of solutions [53,55]. The smaller the values of SP and UD, the better the distribution of the algorithm. The minimum value and average value of each algorithm running ten times were calculated, respectively, and the information is shown in Table 11. It can be seen from the table that MOWSO was run ten times on SP and UD indexes to obtain the smallest average value, indicating that the solution set obtained by the MOWSO algorithm has the best distribution. Figure 12 shows the Pareto front when each algorithm ran ten times to obtain the minimum value on UD. It can also be seen from the figure that the Pareto front of MOWSO is more evenly distributed.

Table 11.

The average of 10 runs of the algorithm on SP and UD.

Figure 12.

Pareto front of MOWSO, MOPSO, and SPEA2 algorithms.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we improve the white shark optimizer algorithm by adding two mechanisms. The first mechanism is to introduce the non-dominated Pareto solution obtained by archiving. The second mechanism is to calculate the true distance between Pareto solutions to filter the best Pareto solutions in the archive. The algorithm is tested on CEC2020 benchmark test function and compared with other classical multi-objective algorithms to verify the performance of MOWSO. The experimental results show that the Pareto solution obtained by MOWSO algorithm is closer to the real Pareto solution and has certain reliability. Then, MOWSO was applied to solve the location problem of rural sports facilities. Through the experiment, it was found that MOWSO can obtain multiple sets of solutions, corresponding to different layouts of sports facilities, and can provide reference for the location problem of rural sports facilities. In real life, there are many similar problems, such as the location of health stations, market sites, and so on. Although these problems have different constraints, similar ideas can be used to solve them. In this paper, the location of sports facilities is taken as a variable, and the location of sports facilities under different target conditions is studied carefully, but the terrain limitation is not considered. If the obtained sports facilities are located on non-construction land, such as paddy fields and agricultural land, etc., it is necessary to avoid these addresses manually. In real life, faced with these complex conditions, the constraints on the location of sports facilities will increase. Due to the high complexity of the specific problem, this experiment may not be considered enough. Therefore, it is very important to propose a new model and improve MOWSO to solve problems in this field under the condition of considering many factors comprehensively.

Author Contributions

Y.Z. (Yan Zheng): experimental results analysis. B.G.: methodology, writing—original draft. Y.Z. (Yongquan Zhou): writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. U21A20464.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Highlights High Cost of Physical Inactivity in First-Ever Global Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Day, K. Built environmental correlates of physical activity in China: A review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Division of Health Promotion, Education & Communication. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1986; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution—A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonen, J.; Kamarainen, J.K.; Lampinen, J. Differential evolution training algorithm for feed-forward neural networks. Neural Process. Lett. 2003, 17, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lin, Z.; Huang, G.B. Composite function wavelet neural networks with differential evolution and extreme learning machine. Neural Process. Lett. 2011, 33, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Zaheer, H.; Garcia-Hernandez, L.; Abraham, A. Differential Evolution: A review of more than two decades of research. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 90, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xi, L.; Wang, S. An improved particle swarm optimization for evolving feedforward artificial neural networks. Neural Process. Lett. 2007, 26, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.K.S.; Zahara, E. A hybrid simplex search and particle swarm optimization for unconstrained optimization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 181, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.M.B. Unsupervised clustering based an adaptive particle swarm optimization algorithm. Neural Process. Lett. 2016, 44, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, T. Particle swarm optimizer with crossover operation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 70, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, Q.; Zhou, Y. Hybrid metaheuristic algorithm using butterfly and flower pollination base on mutualism mechanism for global optimization problem. Eng. Comput. 2022, 37, 3665–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Di Caro, G. Ant colony optimization: A new meta-heuristic. In Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation-CEC99, Washington, WA, USA, 6–9 July 1999; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1470–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Q.; Han, C.; Niu, Y.; Lei, M. Complex-valued encoding metaheuristic optimization algorithm: A comprehensive survey. Neurocomputing 2020, 407, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: A sine cosine algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Deep, K.; Engelbrecht, A.P. A memory guided sine cosine algorithm for global optimization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 93, 103718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liu, Z. Novel grey wolf optimization based on modified differential evolution for numerical function optimization. Appl. Intell. 2020, 50, 468–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Huang, H.; Fan, Q.; Wei, J.; Du, Y.; Gao, W. Grey wolf optimizer based on Aquila exploration method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 205, 117629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, G.; Mirjalili, S.; Khodadadi, N.; Hussien, A.G.; Liao, Y.; Zhao, W. Tianji’s horse racing optimization (THRO): A new metaheuristic inspired by ancient wisdom and its engineering optimization applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozhdehi, A.T.; Khodadadi, N.; Aboutalebi, M.; El-kenawy, E.-S.M.; Hussien, A.G.; Zhao, W.; Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H.; Mirjalil, S. Divine Religions Algorithm: A novel social-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for engineering and continuous optimization problems. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, A.; Al-Tamimi, A.-K.; Al-Alnemer, L.; Mirjalili, S. Stellar oscillation optimizer: A nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Savsani, V.J.; Vakharia, D.P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: An optimization method for continuous non-linear large scale problems. Inf. Sci. 2012, 183, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Zhou, G.; Deng, W.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Q. MOMPA: Multi-objective marine predator algorithm. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 385, 114029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Miao, F.; Luo, Q. Symbiotic organisms search algorithm for optimal evolutionary controller tuning of fractional fuzzy controllers. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 77, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Mirjalili, S.; Elaziz, M.A.; Gandomi, A.H. The arithmetic optimization algorithm. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 376, 113609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Hussain, K.; Houssein, E.H.; Mabrouk, M.S.; AI-Atabany, W. Archimedes optimization algorithm: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, A.; Heidarinejad, M.; Stephens, B.; Mirjalili, S. Equilibrium optimizer: A novel optimization algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 191, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.A.C.; Pulido, G.T.; Lechuga, M.S. Handling multiple objectives with particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2004, 8, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Agrawal, S.; Pratap, A.; Meyarivan, T. A fast elitist non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm for multi-objective optimization: NSGA-II. In Proceedings of the Parallel Problem Solving from Nature PPSN VI: 6th International Conference, Paris, France, 18–20 September 2000; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 849–858. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas, N.; Deb, K. Muilti-objective optimization using non-dominated sorting in genetic algorithms. Evol. Comput. 1994, 2, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Laumanns, M.; Thiele, L. SPEA2: Improving the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm for Multi-Objective Optimization. In Evolutionary Methods for Design, Optimization and Control with Applications to Industrial Problems, Proceedings of the EUROGEN’2001, Athens, Greece, 19–21 September 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Tiwari, S. Omni-optimizer: A generic evolutionary algorithm for single and multi-objective optimization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 185, 1062–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Yue, C.T.; Qu, B.Y. Multimodal multi-objective optimization: A preliminary study. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2454–2461. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, C.; Qu, B.; Liang, J. A multi-objective particle swarm optimizer using ring topology for solving multimodal multi-objective problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2017, 22, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, B.; Gharehchopogh, F.S. A multi-objective optimization algorithm for feature selection problems. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 1845–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, K.; Jangir, P.; Pandya, S.B.; Shanmugasundar, G.; Abualigah, L. Unveiling the Many-Objective Dragonfly Algorithm’s (MaODA) efficacy in complex optimization. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 3505–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liao, B. Dual population multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for dynamic co-transformations. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 3269–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braik, M.; Hammouri, A.; Atwan, J.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Awadallah, M.A. White Shark Optimizer: A novel bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 243, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, M.; Kumar, C.; Jasper, J.S. Optimal parameter characterization of an enhanced mathematical model of solar photovoltaic cell/module using an improved white shark optimization algorithm. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2023, 44, 2374–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supreeth, S.; Bhargavi, S.; Margam, R.; Annaiah, H.; Nandalike, R. Virtual Machine Placement Using Adam White Shark Optimization Algorithm in Cloud Computing. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.; Kamel, S.; Elseify, M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y. A modified white shark optimizer for optimal power flow considering uncertainty of renewable energy sources. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.H.; Kamel, S.; Selim, A.; Shaheen, A.; Yu, J.; El-Sehiemy, R. Efficient economic operation based on load dispatch of power systems using a leader white shark optimization algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 10613–10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, E. Facility location: A survey of applications and methods. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1996, 47, 1421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farahani, R.Z.; Hekmatfar, M. Facility Location: Concepts, Models, Algorithms and Case Studies; Farahani, R.Z., Hekmatfar, M., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Church, R.L.; Garfinkel, R.S. Locating an obnoxious facility on a network. Transp. Sci. 1978, 12, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justesen, P.D. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; University of Aarhus: Aarhus, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, H.; Deng, W.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H. Multi-strategy particle swarm and ant colony hybrid optimization for airport taxiway planning problem. Inf. Sci. 2022, 612, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, A.; Jin, Y. RM-MEDA: A regularity model-based multi-objective estimation of distribution algorithm. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2008, 12, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L.; Laumanns, M.; Fonseca, C.M.; Da Fonseca, V.G. Performance assessment of multi-objective optimizers: An analysis and review. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2003, 7, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Y. Approximating the set of Pareto-optimal solutions in both the decision and objective spaces by an estimation of distribution algorithm. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 13, 1167–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.; Lee, T.H.; Khor, E.F. Evolutionary algorithms for multi-objective optimization: Performance assessments and comparisons. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2002, 17, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, J.R. Fault Tolerant Design Using Single and Multi-Criteria Genetic Algorithm Optimization. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Suganthan, P.N.; Qu, B.Y.; Gong, D.W. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC 2020 special session on multimodal multiobjective optimization. Comput. Intell. Lab. Zhengzhou Univ. 2019, 10, 353–370. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).