Abstract

(1) Background: Although culturally grounded health interventions (CGHI) have shown efficacy in improving Indigenous health, few CGHI for Queer and Transgender Pacific Islander (QTPI) communities exist to address their health promotion. This study explores QTPI experiences of health for cultural mechanisms to develop CGHI for QTPI health promotion. (2) Methods: Using Indigenist community-engaged research methodologies, we collaborated with the United Territories of Pacific Islanders Alliance of Washington and Guma’ Gela’ to conduct 11 exploratory semi-structured interviews with QTPI community members living in the Puget Sound area of Washington state. These interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis. (3) Results: QTPI well-being was greatly influenced by how settler colonialism impacted their connectedness to their families, communities, and cultures. We also found that inágofli’e’ and alofa, relational values in CHamoru and Sāmoan culture, played essential roles in facilitating QTPI health. Many participants fostered these values through chosen family, community care, and Indigenous mobilities. (4) Conclusions: Our findings indicate a need for CGHI that facilitate inágofli’e’ and alofa for QTPI to combat settler colonialism’s impacts on QTPI well-being. Finally, we present a community-centered conceptual model for culturally grounded health promotion in QTPI communities.

1. Introduction

Indigenous Queer and Transgender Pacific Islanders (QTPI)—Gela’, Fa‘afafine, Māhū, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (Trans), Queer, and Intersex Pacific Islanders (PI) who embody intimacies and genders outside of Western cisheteronormative binaries (see Table 1)—exhibit a multitude of health disparities compared to straight and cisgender PIs. A report completed by the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law using data from the Gallup Sharecare Well-Being Index Survey found QTPI had significant social, physical, and mental health disparities compared to straight and cisgender PIs (Choi et al. 2021). For example, 55% of QTPI adults were living below the 200% federal poverty level compared to 42% of straight and cisgender PIs, and QTPI reported significantly higher rates of depression (26% vs. 13%), asthma (26% vs. 14%), cancer (26% vs. 14%), and hypertension (26% vs. 14%) compared to straight and cisgender PIs. Culturally grounded health interventions (CGHI) have the potential to alleviate these health disparities. CGHI, specifically from Indigenous traditions, cultural knowledge, practices, and protocols, have shown promise in improving PI and other Indigenous community health outcomes (Kaholokula et al. 2018; Uchima et al. 2021; Walters et al. 2020). Despite recognition of health disparities experienced by QTPI, few CGHI center the knowledge and experiences of QTPI for health promotion and prevention. This paper seeks to understand QTPI perceptions of individual and community health and identify cultural mechanisms to develop CGHI for QTPI.

Table 1.

Terms for Queer and Trans Pacific Islander gender and intimacy.

1.1. Settler Colonial Roots of QTPI Health Disparities

The colonization of Pacific Islander nations has greatly contributed to the health and social disparities experienced by QTPI communities. Prior to colonial contact, PIs (e.g. CHamorus, Sāmoans, and Kānaka Maoli) created complex self-governing societies with cultural, spiritual, technological, and healing practices grounded in their worldviews (Diaz 2011b; Hau’ofa 1994; Lizama 2014; Osorio 2021b; Teaiwa 1994; Trask 1999). QTPI have held culturally significant roles as cultural practitioners, knowledge bearers, healers, and warriors (Brown-Acton 2020; Camacho 2015; Hamer and Wong-Kalu 2022; Manoa et al. 2019; Young 2020). CHamorus have also relied on QTPI family and community members—those who are Gela’, Manmalao’an, Manmalalahi, Tinalao’an, Machom, Mamflorita, Queer, and Trans—to poksai (to take cultural responsibility for nurturing and caregiving another’s child) children in their extended kin when their given parents are no longer able to care for them (Camacho 2015). Although oral, historical, and genealogical records of QTPI exist, many QTPI are heavily scrutinized by their own community members that interrogate the validity of their Indigeneity (Osorio 2020; Teves 2018; Camacho 2015). This scrutiny is rooted in the settler colonial imposition of Western values, morality, familial structures, intimacy, and gender roles into the cultural practices and values of Indigenous communities (Camacho 2015; Kanemasu and Liki 2021; Osorio 2021b; Teves 2014; Williams 2019).

Through settler colonialism, QTPI and other Indigenous people experience oppression and are erased through structural, sociocultural, interpersonal, and psychological processes that perpetuate and uphold a newly established settler nation-state (Arvin 2019; Arvin et al. 2013; Kauanui 2016; Tuck and Yang 2012; Veracini 2011; Wolfe 2006). Settler colonialism seeks to establish White, cisgender, heterosexual, Christian male dominance over Indigenous peoples, particularly those who are femme, Trans, and Queer (Arvin et al. 2013; Grosfoguel 2013; Naputi 2019; Souder-Jaffery 1992; TallBear 2018). Through the introduction and normalization of Western gender and intimacy ideologies, settler colonialism disrupts and destroys PI cultural knowledge that holds the stories, histories, and genealogical records of their existence in a process called epistemicide (Grosfoguel 2013; Hall and Tandon 2017). Specifically, these processes occur through the settler colonial establishment of cisheteropatriarchy and cisheteronormativity in PI cultures, communities, and societies through Christianization, militarism, and tourism.

Indoctrination of Christianity and Western ideologies has altered PI cultural perceptions and practices of intimacy and gender (Arvin 2019; Camacho 2015; DeLisle 2019; Diaz 2010, 2011a; Goodyear-Ka’opua 2014; Osorio 2021b; Souder-Jaffery 1992; Tapu 2020; Teves 2018). As a result of indoctrination, power and land distribution were consolidated under cisgender men and heterosexual couples. In essence, policies and systems are formed to assimilate QTPI cultural identity and Indigeneity into state-imposed categories of Indigeneity, giving colonial states power to determine eligibility for social welfare, citizenship, and land (Teves 2018). During Spanish colonial governance in Guåhan, matrilineal and feminine control of land distribution, which previously allowed land to be passed down through women, became reconsolidated under cisgender male control by the institution of holy matrimony and the restructuring of CHamoru familial structures into nuclear units (Cunningham 1992; Diaz 2010; Naputi 2019). In Hawai‘i, the imposition of a blood quantum in land tenure laws forced Kānaka Maoli women to create nuclear families with Kānaka Maoli men to produce children eligible to maintain claims to land (Goodyear-Ka’opua 2014; Osorio 2021b). These structural inequities have reshaped the cultural memory of QTPI, reducing their sense of belonging and rights within their homelands (Arvin 2019; Camacho 2015; Fieland et al. 2007; Kerekere 2017; Osorio 2021b; Teves 2018; Wolfe 2006). Christian ideologies continue to pervade PI sociocultural structures enforcing and normalizing Western familial structures—nuclear families, rigid gender binaries, and procreative heterosexual intimacy between cisgender men and women—over Indigenous ways of being.

The Christianization of PI sociocultural structures normalizes Western gender binaries, cisheterosexual intimacy, and patriarchal power. This normalization privileges cisheterosexual nuclear families through the erasure and demonization of QTPI, Two-Spirit, and other Indigenous Queer and Trans people (Camacho 2015; DeLisle 2019; Diaz 2011a; Fieland et al. 2007; Naputi 2019; Osorio 2021b; TallBear 2018; Teves 2014, 2018). Prior to Spanish colonialism, gender roles were less defined in CHamoru spaces on Guåhan. During Spanish colonialism, spaces where sacred sexual knowledge and sexual intimacy were practiced like Guma’ Ulitao—a CHamoru cultural space where CHamoru men learned sacred cultural protocols and skills—were viewed as morally repugnant by Catholic missionaries and were outlawed to align with Catholic moral ideologies (DeLisle 2019; Diaz 2010; Naputi 2019). In the early 1900s, after Guåhan was acquired by the US after the Spanish–American War, the US Naval Government established penal codes that criminalized Queer intimacy and cohabitation, which aligned with US colonial laws to impose Judeo-Chrisitan moral control in their colonies (Camacho 2015; Eaklor 2008; Naputi 2019; Tapu 2020). In Guåhan, Christian ideologies are reflected in rhetoric historically utilized by Catholic and politically conservative CHamorus who have framed Queer intimacies and Trans identity as morally reprehensible (Camacho 2015).

In parallel with Christianization, US militarism and tourism in PI societies have also contributed to the disruption of Indigenous worldviews by generating a hyper-polarized construction of binary gender that reinforces masculine dominance over femininity (Arvin 2019; Camacho 2015; K. L. Camacho and Monnig 2010; DeLisle 2019; Goodyear-Ka’opua 2014; Osorio 2020, 2021b; Teaiwa 1994, 1999; Teves 2018; Trask 2001). Militourism, with its complex synergistic and gendered relationship, establishes a military presence on Indigenous lands to create a land base that provides access and exploits culture and resources for tourism (DeLisle 2016; Teaiwa 1994, 1999). After a tourist economy is established, tourism masks the existence of the colonial violence that militarization perpetuates (Camacho 2015; Teaiwa 1994). Through these systems, PI lands are racialized, sexualized, and gendered as inherently feminine, exotic, fertile, and helpless to justify safeguarding settler economies and governance structures under the guise of protecting and assimilating PI peoples and land through colonial imposition and White saviorism (Arvin 2019; Tamaira 2010; Teaiwa 1994, 1999; Teves 2018).

Militourism is a determinant of health that exacerbates disparities in poverty, homelessness, migration, chronic illnesses, and mental health outcomes for PIs (Bevacqua 2017; Camacho 2015; Diaz et al. 2020; Goodyear-Ka’opua 2019; Hau’ofa 1994; Na’puti and Bevacqua 2015; Natividad and Kirk 2010; Spencer et al. 2020; Teaiwa 1999; Trask 1999, 2001). For QTPI, PI women, and PI femmes, militarism increases exposure to gender-based and state-sanctioned violence. For example, during the Vietnam War era in the 1960s and 1970s, to accommodate an influx of US military personnel who were stationed in Honolulu for redeployment and recreation, a public ordinance was passed that outlawed “deception” leading to surveillance and policing of māhū wāhine gender expression through police, physical, and sexual violence (Young 2020). Today, QTPI, PI women, and PI femmes face an increased risk and exposure to violence perpetuated through militourism, Christianization, and their reproductions of cisheteropatriarchy within PI communities (Camacho 2015; Cristobal 2022; Diaz 2011a; Frain 2017; Kanuha 2002; Sailiata and Teves 2022; Young 2015, 2020).

Though some social progress and civil rights have been extended to QTPI in their Indigenous homelands, unincorporated territorial status sometimes complicates these protections for QTPI living in American Sāmoa and Guåhan. In American Sāmoa, though the Obergefell vs. Hodges ruling extended marriage equality rights to US territories, legally they are functionally unenforceable in American Sāmoa because they lack a federal district court to appeal to. In essence, while the ruling may appear to promote marriage equality, it remains toothless, with no true means of enforcing marriage equality rights for Sāmoans that this laws seek to create (Tapu 2020). Territorial political status for American Sāmoa, Guåhan, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands serves to further the structural inequities that QTPI experience in their Indigenous homelands.

Despite social progress made in their Indigenous homelands, QTPI continue to be impacted by the historical and ongoing traumas produced by settler colonialism. Though marriage equality and civil rights are seen as markers of progress and are important for securing the health and well-being of QTPI, the framework of legal rights fails to address the violence and settler colonial movements that harm and erase QTPI (Camacho 2015; Puar 2015). Homonationalism and settler trans-nationalism—ideologies of Queer and Trans settler citizenship—uplift the provision of liberalist marriage equality and Trans civil rights while undermining and perpetuating QTPI experiences of colonial and state-sanctioned violence, land displacement, and epistemicide (Camacho 2015; Jesperson 2022; Young 2015, 2020). In fact, these ideologies only seek to assimilate and extend privileges, civil rights and protections to QTPI and Indigenous Queer and Trans people who conform to settler ideologies of cisheteronormativity.

As settler colonialism underlies and perpetuates the health disparities for QTPI, creating CGHI for QTPI that address settler colonialism may support reductions in health disparities for QTPI. Though there is a need for the development of these CGHI to address the unique experiences of settler colonialism, few studies document such interventions and their efficacy.

1.2. Culturally Rooted Health Promotion for QTPI

The Indigenist stress-coping model frames settler colonialism as a form of historical and ongoing trauma, ecosocial stressor, and cause of the physical and mental health disparities experienced by Indigenous Queer and Trans people (Fieland et al. 2007; Walters and Simoni 2002). Notably, this model suggests that cultural determinants of well-being—identity, enculturation, spirituality, and traditional health practices—offer pathways for alleviating health disparities for Queer and Trans Indigenous communities (Fieland et al. 2007). However, little is known about how QTPI conceptualize well-being, which poses challenges to assessing QTPI health generally. Having an accurate framework to understand Queer and Trans Indigenous health that includes well-being measures like spirituality, historical trauma, discrimination, culturally specific coping tools, and cultural taboo is critical to understanding pathways to improve health disparities (Alvarez et al. 2020; Fieland et al. 2007; Lehavot et al. 2009; McGrath and Ka’ili 2010; Thomas et al. 2021; Walters et al. 2011).

CGHI facilitate positive health outcomes for Indigenous communities by utilizing cultural knowledge, practices, and protocols as health intervention (Ho-Lastimosa et al. 2019; Kaholokula et al. 2018, 2019; Rasmus et al. 2019; Spencer et al. 2023; Walters et al. 2020). An example of how CGHI can promote positive health outcomes is found in Ke Kula O Waimānalo’s implementation of the Mini Ahupua‘a for Lifestyle and Mea‘ai (MALAMA) project, a Native Hawaiian family-based cultural intervention that supports creating mini ahupua‘a (land management system) for families living in food-scarce rural areas. By integrating traditional land stewardship practices and values with modern backyard aquaponics systems, the MALAMA project increases food sovereignty for Kānaka Maoli families, improves their access to healthy foods, and strengthens familial relationships and community connectedness (Beebe et al. 2020; Chung-Do et al. 2019; Ho-Lastimosa et al. 2019). Though Kānaka Maoli are not included in our study’s sample, CGHI in Sāmoan and CHamoru communities are not well documented in existing academic literature. CGHI center holistic health approaches drawing from Indigenous knowledge, integrating cultural practices, restoring relational ways of being, and transforming embodied narratives of victimization and colonization into those of hope and well-being (Walters et al. 2020). For example, Project Talanoa, a pilot intervention using Talanoa to address risky health behaviors among Sāmoan and Tongan youth, was found to be culturally appropriate and impactful for these communities due to its integration of Sāmoan and Tongan cultural practices (McGrath and Ka’ili 2010). Despite strong evidence of their efficacy, (Walters et al. 2020), few CGHI exist that directly address QTPI health. Furthermore, the policing of QTPI Indigeneity, intimacy, and gender within PI families and communities poses unique barriers to accessing cultural knowledge and resources needed to promote Indigenous well-being.

Understanding mechanisms to promote healing through cultural means like CGHI is essential to effectively address QTPI health disparities. Centering QTPI desires and futurisms in the process of their development is equally critical. The current research explores how QTPI conceptualizes health and well-being and identifies mechanisms for culturally grounded health promotion to better health outcomes for QTPI communities. Additionally, few conceptual models exist that address well-being and health promotion for QTPI that address cultural determinants of health. From our findings, we developed a conceptual model for culturally grounded health promotion in QTPI communities.

2. Materials and Methods

Thematic analysis was used to analyze 11 semi-structured interviews conducted with English-speaking QTPI adults (18 years of age or older) living in Seattle and the Greater Puget Sound area of Washington State. The study centers Indigenist collaborative research principles (Walters et al. 2009), which combine Indigenist and decolonizing methodologies with a community-based participatory research methodology in its design and protocols. In practice, we applied this methodology by centering Pacific Islander relational ethics and values (Tisnado et al. 2010; Anae 2016; Aikau 2019) in our research protocols and engagement with WA Pacific Islander communities in the research process for this project. To honor these relational values in our research practice, we centered community resilience in project development and integrated indigenous epistemologies and community sovereignty into the research process through the co-development of the project from conceptualization to dissemination with a QTPI community advisory committee (CAC).

Our CAC was composed of four QTPI community leaders working with two community organizations serving QTPI communities in Seattle and the Greater Puget Sound area: the United Territories Of Pacific Islands Alliance of WA (UTOPIA WA) and the Guma’ Gela’ Trans and Queer CHamoru Art Collective. The CAC was created to support and ensure that relational ethics and Indigenous values were practiced within our research protocols and that the epistemologies of QTPI communities were honored, valued, and respected in the collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of our data. Members were selected based on their roles in community leadership, service provision, technical skills, and lived experiences as QTPI. To make our work more accessible for QTPI communities, a table defining relevant cultural and technical terms is included in Appendix A (see Table A1). Despite changes in CAC membership due to COVID-19 and organizational shifts, the findings and interpretations were reviewed by one new and two original members. Additionally, our research team consisted of a Gela’ CHamoru principal investigator, a Kānaka Maoli co-investigator, and three undergraduate research assistants identified as PI, Indigenous, Queer and/or Trans. Additional authors, who held one of the aforementioned identities, contributed to the production of this manuscript and interpretation of the data.

2.1. Sampling and Recruitment

Study participants were recruited with a combination of purposive and snowball sampling through social media posts and emails to listservs managed by UTOPIA WA, Guma’ Gela’, and the Associated Students of the University of Washington’s Pacific Islander Student Commission. Participants were recruited on a rolling basis and selected to represent a variety of sexual orientations, gender identities, and ethnic backgrounds. Interested individuals were asked to fill out a recruitment form that included place of residence, age, ethnic background, gender, and sexuality. Only participants who were QTPI and living within Seattle and the Greater Puget Sound were selected. Individuals who were interested in the study were contacted via email. Out of the 23 individuals who expressed interest, 21 were eligible and were contacted to participate in the study. Of those eligible, 12 participants responded and then completed the interview. Each participant was compensated with a $20 Visa gift card for their participation. Participants who completed the study were also asked to share the study flier with other QTPI community members. Unfortunately, we did not track what proportion of our sample was recruited through snowballing. Human-subjects exemption was granted by the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board before research activities began.

2.2. Demographics

The final sample of 12 study participants self-identified racially as PI and ethnically as CHamoru (n = 5), Sāmoan (n = 5), Sāmoan-Tongan (n =1), and Filipino (n = 1) aged 22–42 years old (see Table 2). As a collective decision with our CAC, a single Filipino participant was excluded from the analysis. We included this participant in the overall sample but excluded them from analysis to honor their self-identification as PI and focus our study on Micronesian, Melanesian, and Polynesian communities, aligning with current data disaggregation practices for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities (Morey et al. 2020). One participant’s demographics were recategorized into CHamoru and Not Quantifiable Sexuality and Gender categories, in place of an “other” category, to protect their confidentiality. All participants identified as Queer, Trans, and/or with a culturally specific, non-heteronormative intimacy practice or gender (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant demographics.

2.3. Data Collection

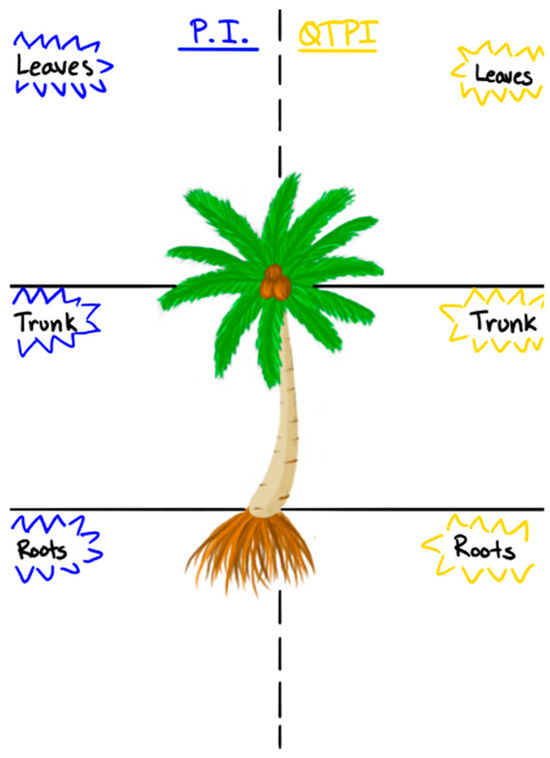

Data collection consisted of one-hour semi-structured interviews both in person (n = 6) and virtually (n = 6) utilizing Zoom video conferencing software version 4.6 for macOS. Initially, the first six interviews were conducted in person at the University of Washington Seattle and the UTOPIA WA office in Kent, WA. However, due to COVID-19 social distancing guidelines, six of the interviews were completed via Zoom. Our interview guide, co-designed with our CAC, included questions on QTPI perceptions and experiences of their health and well-being, experiences with healthcare providers, and an interactive mapping activity to facilitate conversation on cultural facets that QTPI identified to potentially improve their overall health. The interview guide encouraged the use of storytelling from participants’ lived experiences, while the mapping activity utilized a coconut tree as a metaphor to facilitate conversation on root causes and determinants for QTPI health (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mapping exercise used in interviews.

2.4. Data Analysis

All interviews were conducted by the first author and one undergraduate research assistant. Once completed, each interview was transcribed verbatim using Trint (Trint Ltd. 2020), an online automated speech-to-text transcription software, which was then edited and formatted by our research team. These transcripts were uploaded onto and analyzed on Dedoose online software for collaborative coding and qualitative analysis (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC 2016).

Thematic analysis—an approach that utilizes inductive and deductive coding schema to search across qualitative data for common and unique themes—was utilized to analyze the data. Deductive codes were created from the existing literature and the Indigenist stress-coping model. The first author and research assistants utilized these deductive codes and independently generated inductive codes, utilizing participants’ experiences (Braun and Clarke 2006; Kiger and Varpio 2020). Two data-rich interviews were selected to generate an initial set of codes by the first author. These codes were then compared between two coders and a third non-coding researcher and consolidated into larger axial codes. A draft codebook with exemplar quotes was reviewed by the CAC.

The CAC discussed discrepancies and validated the final iteration of the codebook. The finalized codebook was then used to code all 11 transcripts. Two coders and one non-coding researcher were assigned to each transcript to establish inter-coder relatability. Code co-occurrence charts and the code frequency tables produced by Dedoose were used to organize the data. Finally, the research team examined the codes and their corresponding excerpts to develop themes that were then reviewed, adjusted, and approved by the CAC.

3. Results

To illustrate our 10 emerging themes, we utilize an in vivo narrative framing—each subsection uses a participant’s quote as a title representing its theme. In addition, as part of our Indigenist collaborative methodology, we refused to share specific details from certain participants ‘stories that may have caused harm by way of their inclusion in this publication. Instead, we list common QTPI community experiences identified by our CAC to, as Eve Tuck notes, suspend damage (Tuck 2009). This refusal to share suffering and pain for the purpose of research and instead summarize their experiences when there is already general acknowledgment of these experiences by the community honors the fullness of our participants’ experiences without compromising their well-being and safety (Tuck and Yang 2014). Each participant was given a “drag name” or pseudonym that honors their connection to their ancestors in various CHamoru and Sāmoan legends. These include names of deities and heroic, elemental, and non-elemental beings. The drag names are intended to help readers better connect with and remember our participants’ stories. We later present a conceptual framework built from our findings to understand the relationship between settler colonialism and QTPI well-being and to identify cultural mechanisms to promote QTPI well-being.

3.1. When I Think of a Typical Chamorro Breakfast, I Think, You Know, SPAM, Eggs, and Rice

QTPI identified several health issues experienced by their communities, such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, cancer, respiratory illnesses, sexually transmitted infections, HIV, depression, anxiety, suicide, physical and emotional violence, gender-based violence, sexual violence, and access to gender-affirming care. With the exception of gender-affirming care, most of the health issues QTPI experienced were identified as health issues for all PIs, as described by Ko’ko’, a CHamoru Gela’. For example, most participants identified that diabetes and heart disease were prevalent issues for all PI communities. These diseases were attributed to systemic issues related to colonization. When asked about specific historical causes of health issues for QTPI, Hilitai, a gay CHamoru man, attributed his type 2 diabetes to the colonial introduction of processed foods, like SPAM, into the CHamoru diet:

I’m type 2 diabetic and that has a lot to do with my relationship with food and the foods I ate growing up. I think that the food habits that my people have in the modern day kind of come from... like for example, SPAM. SPAM’s not … from the island, you know, that’s, like, shipped there. And I think that has a lot to do with our island’s history of occupation and colonization, and other foods that were introduced into our diet that’s not...um, you know, from the land or from the sea. In the area… When I think of a typical Chamorro breakfast, I think, you know, SPAM, eggs, and rice. And that’s… you know, that probably wasn’t... the way centuries ago with Indigenous folk…my relationship with food has a lot do with, like, my culture.

Several QTPI noted that colonization generated an over-reliance on imported foods, many of which they identified as unhealthy—including processed and imported foods with saturated fats like SPAM and “turkey tails”. Note that Hilitai says that his relationship with food is intertwined with his relationship with culture. Gathering around food, and food itself, were centered as a culturally specific practice related to PI and QTPI health. Hilitai’s reflection demonstrates how PI traditions synchronously operate with colonization’s disruption of PI food systems to produce unbalanced well-being for QTPI. Though QTPI did not distinguish this as a distinctly QTPI health issue, broader PI experiences are intrinsically intertwined with QTPI experiences and other health issues described in our results rooted in colonialism. Throughout QTPI stories, we found that colonization had a profound impact on QTPI health and well-being, particularly for experiences of mental health challenges and violence.

3.2. What Was Once a Resource to Our Community… Is Now an Excuse for Disconnection and Violence

Throughout the study, many of the QTPI articulated how colonization impacted how fellow straight, cisgender PI community members perceive and maintain relationships with them as QTPI. When Gadao, a CHamoru participant, was asked to identify the root causes of negative health outcomes for QTPI, they explicitly linked colonization to heterosexism, transmisogyny, transphobia, and other forms of oppression in PI communities. Gadao discussed how colonization severed the connection of QTPI to their communities through the erasure of spiritually significant societal roles rooted in Indigenous PI worldviews:

I think about colonization as being the root of heterosexism and transmisogyny and transphobia. So like I would add those things to that side because I think that they need to be named. But I also think that they’re rooted in other forms of oppression, right. Like in our Indigenous worldviews… and many Indigenous worldviews and including many Pacific Islander worldviews, people who we call Trans or Queer, you know, often hold and have held spiritually significant and important roles in the community. And I think that the erasure of that through colonization endangers our lives. But it also endangers the health of the entire community because …you know, what was once a resource to our community… is now an excuse for disconnection and violence.

Gadao traces health issues in PI communities to colonization through the erasure of PI worldviews, cultural practices, and beliefs, and the forced adoption of colonial beliefs related to gender that manifests as heterosexism, transmisogyny, and transphobia. The colonial disruption of PI cultural mores simultaneously perpetuates the erasure of culturally significant roles for QTPI and enables their oppression. As Gadao articulates, the roles of QTPI were mutually beneficial for all members of their respective communities. QTPI were accepted within their respective communities, and their roles allowed them to support the health and well-being of the greater community while tending to their personal spirituality and well-being. The erasure of PI worldviews via colonization endangers the lives of QTPI and their communities. This bars QTPI’ ability to fulfill the vital roles they once held and subjects them to disconnection and violence.

3.3. We Have Transitioned to a Society Where Being Tender, Being Feminine Is Not a Strength Anymore

Epistemicide and colonial disruption of PI gender roles and intimacies were discussed by several QTPI when asked how their peoples’ histories impacted their health as QTPI. Taema, a Fa‘afafine woman, described the impacts of disruption to gender and femininity, specifically through shifts in Sāmoan values related to Christianization and the introduction of cisheteropatriarchy. She notes that this has led to greater internalized Fa‘afafine-phobia:

From the stories that I’ve been told over and over again is that women were... for lack of a better term… the breadwinner and like it’s also like very capitalist to say that but like they were… the heads of families. They led with a lot of love, but also a lot of strength. We’ve transitioned to a society where being tender, being feminine isn’t a strength anymore… And it doesn’t just affect me, as you know, it also affects any person who is femme, right?... There’s never any space for people to explore... especially for men to explore what femininity is and also explore what healthy masculinity is. Which has a lot of the love and tenderness that is often associated with femininity… You know, a lot of internalized Fa‘afafine-phobia that you carry with you… into adulthood.

Taema’s descriptions of colonial disruptions to gender and intimacy share similarities with how other study participants described it throughout the study. However, her description above dives deeply into how epistemicide has disrupted cultural roles, significance, and ideologies of gender and intimacy and its connections to internalized oppression among QTPI, specifically fa‘afafine. Though she does not specifically indicate culturally specific roles of QTPI as Gadao did, she notes that disruptions to broader cultural ways of embodying gender and intimacy exacerbate internalized oppression within QTPI. She also noted that “fa’afafine were fa’atosagas” or Sāmoan birth navigators. Though she did not state that this was a role culturally specific to Fa’afafine, she noted how there was a need to decolonize the history of Fa’afafines’ participation in cultural roles like these so that “They’re honored and that their legacy will carry on for future generations….like coming back into the fold for a lot of queer and trans people or, you know, non-cis people in our culture”. In this, she acknowledges the impact the suppression of Fa’afafine knowledge and cultural histories has on Fa’afafine cultural belonging. In this discussion, she also described its impact on PI communities and kin police QTPI expression and Indigeneity.

3.4. I Was Policed for Being Femme, for Being Fa‘afafine, for Being Trans

Some participants noted that colonization resulted in the policing of QTPI identities by their PI communities, sometimes with violence. This drove the disconnection between their families, communities, and ultimately their cultures. Taema notes the establishment of patriarchy as a result of colonization and shifts in how Sāmoan communities police Fa‘afafine gender and devalue Sāmoan femininity:

[Femininity] is silenced, right? And that affected my health in a few ways where I was policed for being femme, for being Fa‘afafine, for being Trans and… a lot of young Fa‘afafine, you know, including myself, that had a lot of… internalized hate because I, you know, I wanted to be the good Christian child. I wanted to make my parents happy… And, there was a lot of self-harm, but also there was a lot of internalized transphobia there… That affects your mental health for sure. And… it affects you in the long run, right. Where you’re not seen as worthy… not worthy of love or not worthy of existing.

Taema explains the tensions between her cultural obligations to care for her Sāmoan kin with the identity policing she experienced growing up from loved ones in her community that contributed to the trajectory of her health outcomes over time. She upholds her obligations to her family from the time she is “able to make [a] pot of rice”. However, her ability to love herself with equal sacredness is complicated by the violence she encounters when her Sāmoan kin police her QTPI identity. The sustained policing of femmes and Fa‘afafine for being Trans has ultimately led to internalized transphobia among Fa‘afafine, which negatively impacts their self-worth and mental well-being. Furthermore, disconnections from families that result from this policing further expose QTPI to violence as they search for what is missing from their relationships with family and community.

3.5. You Go Searching for What Is Missing… Sometimes … You Are Met with More Violence

When prompted, Taema expanded upon the shifts of gender roles in Sāmoan society and illustrated the impacts of cisheteropatriarchy on values around Indigenous femininity. Taema specifically notes that worldviews of love and tenderness related to femininity are no longer practiced by her community, which, she implies, is due to Christian colonization:

And for me, I sought approval from and validation and felt affirmed by men. And in some ways, it was, you know, like being fetishized… but it helped me with my self-esteem and my confidence. You go searching for what’s missing from your own family. Sometimes it’s been in the wrong places where you [are] met with more violence.

Taema noted that historical accounts shared by her elders held women in higher positions of power within Sāmoan society and families that allowed femininity to be viewed as a source of strength. The restructuring of gender roles and power around patriarchy led to a disconnection with femininity as a source of love and tenderness for her community. Disconnection grew from the policing of QTPI and femme identity described not only by her but by several other CHamoru and Sāmoan participants. Taema describes the violence she experienced through relationships as being rooted in the disconnection she had from her family and a devaluation of Sāmoan femininity. Several participants pointed to the violence (primarily sexual and physical) QTPI face throughout their lifetimes. Identity policing is a consequence of colonial disruptions to cultural ways of being and worldviews. These disruptions posed challenges for QTPI in our study to maintain their health and well-being.

3.6. Honoring Inágofli’e’ and Alofa: Indigenous Pacific Worldviews of Relationality

QTPI noted different aspects of their cultures were important to facilitate better health and overall well-being for the QTPI community. These included traditional medicine, language, storytelling, art, dance, food, ways of being, and community, for example, Sāmoan to‘ona‘i—traditional Sunday gatherings around food and family—and CHamoru inafa’maolek—a way of being that centers on creating collective good through respect, reciprocity, relationality, familial kinship, forgiveness, and kindness. Our CAC identified the specific embodiments of inágofli’e’, a CHamoru relational way of sharing love that “deeply” sees and validates a person for who they are, and alofa, a core tenant of fa‘asamoa that underlies how Sāmoans practice kinship, relationality, and love, deeply embedded in our participants’ stories as common cultural ways of being that facilitated health and well-being. In analyzing how QTPI centered these worldviews in their health, we found that the disruption of inágofli’e’ and alofa within their respective communities and families—both PI and non-PI—had a notable influence on their health and well-being.

3.7. You Are Not Allowed to Be a Whole Person….Just [Exist] as a Person, Period

We found that QTPI identity was policed and diminished in community spaces, leading to negative health consequences for participants. Ko’ko’, a CHamoru Gela’, expressed the lack of examples of their QTPI identity, outside of stereotypical representation, in different community spaces—CHamoru, Western, and Queer spaces. They connected the inability to recognize and understand CHamoru QTPI in each space to restricted resources that prevent violence and mental health issues for QTPI. Ko’ko’ stated that a QTPI is unable to “be a whole person” unless they conform to stereotypical representations of themselves:

We are not very much represented…there’s a lack of discussion around [CHamoru QTPI] experiences... that leads to… a lack of resources in the sense of how can you recognize a healthy, intimate relationship? Can you build one… contribute to one? And so I think that definitely leads into things like the domestic violence, the sexual violence. Going into the mental health, I think again, not having much… representation, or feeling like you have a voice in your community, oftentimes being disregarded. I think that definitely takes a toll on yourself and how… you see yourself and how the world at large sees you… And so if you’re oftentimes being stereotyped or being pushed down and the only time you’re held of any reverence is if you’re performing or exuding these tropes, you’re not allowed to be a whole person….just [exist] as a person, period.

Ko’ko’ experienced a lack of inágofli’e’ in multiple spaces they must navigate as a QTPI. The experience of not “having a voice” or “being seen” in their cultural communities and in Western and Queer spaces was common among several participants. They also describe a tension between having to conform to stereotypes of QTPI in order to be “allowed to be a whole person”. In another interview Sina, a Fa‘afafine woman, described some of these QTPI “tropes”:

They still see [Fa‘afafine] as caretakers of families and without rights to express ourselves and to love who we want to love and to be who we want to be and to be accepted just for that. I think over the years and for Lord knows how—some Fa‘afafine they were just seen for caretakers for families, caretakers of children… And that’s how basically they see us. And other than entertainers, it’s just we’re caretakers.

Challenges to navigating cultural spaces, compounded with the scarce representation of QTPI identities, and the invisibilization of experiences outside the roles of caregivers and entertainers create tension that harms the well-being of QTPI. As Ko’ko’ states:

There’s a lack of [CHamoru QTPI] examples, so I think a lot of people are really trying to figure out ways to articulate themselves and, oftentimes, outside of their own personal cultural contexts. And therefore, I think there’s always something that’s a little lost in translation.

Ko’ko’ shares that there is a clear dearth of representation of QTPI experiences, which, when coupled with limited cultural articulations of QTPI identity, perpetuate an absence of inágofli’e’ and alofa for QTPI among their communities. Ultimately, limited representation of QTPI experiences and ways for QTPI to articulate themselves culturally contributed to how Ko’ko’ and Sina did not feel “whole”. Ultimately, Ko’ko’ and Sina’s stories show us that mental health and physical safety challenges to QTPI, including suicide and relationship violence, are driven by an absence of inágofli’e’ perpetuated by missing cultural representations of QTPI.

3.8. When a Fa‘afafine Transitions … It Becomes a Harder Conversation Culturally

When QTPI attempted to express their identities beyond cultural boundaries, they experienced familial disconnection. Tilafaiga, another Fa‘afafine woman, discussed her experience undergoing gender-affirming care and the tensions it caused with her cultural responsibilities to her family. She wanted to live her life authentically but did not receive alofa from her Sāmoan kin during her medical transition and, in turn, experienced trouble managing her health:

…being disowned from my family for trying to go through this transition and living authentically, where my parents,… well, they’re very religious Christians and that was against their beliefs. And so going through that change and then culturally impacting my family…I have to deal with, trying to rebuild that relationship with my mom and… reconnect with my family, even after I started living full time as a woman, not necessarily as a Fa‘afafine individual. Because in our culture, that was normal. You know, … everybody has a Fa‘afafine child. But … when a Fa‘afafine transitions to live their life as a woman and starts [gender affirming care] it becomes a harder conversation culturally… being able to find peace with family and then at the same time still trying to be able to live healthy because I have to take my hormones…to be able to be feminine…

We refuse to share Tilafaiga’s story beyond this quote and instead list common QTPI community experiences from her story identified by our CAC. This includes experiences of homelessness, suicidality, alcoholism, and emotional dysregulation tied to experiences of lacking alofa from family, due to familial disconnection and rejection when QTPI begin “living authentically,” whether it be through undergoing gender transition or being out about their gender and sexuality. For Sāmoans and CHamorus, family is central to their ways of being, specifically fa‘asāmoa and inafa’maolek. Disruption to QTPI relationships with their families was acknowledged as a source of challenges to QTPI well-being. Although Tilafaiga shared challenges she met throughout her life, she acknowledged that later in her life, she reconciled with her family, received counseling for her behavioral health, and nurtured alofa with her chosen family. Chosen family was one space where many participants nurtured inágofli’e’ and alofa for themselves, which in turn restored balance and promoted healing in their health and well-being.

3.9. They Love Me Dearly, but They Would Have Never Understood That Because They Are Not Fa‘afafine

Chosen families were repeatedly cited across the study as pertinent to maintaining and improving the health of QTPI. Several of them described their chosen family as a space where the inágofli’e’ and alofa they did not receive from their given families were provided and nurtured. Nafanua, a Fa‘afafine woman, spoke of the profound sense of support provided by her chosen family, who are also Fa‘afafine. She noted that her given family wanted to provide more alofa to support her, but they do not understand her experience as a Fa‘afafine and are not able to provide the relevant support she needed. As a result, Nafanua highlights how her chosen family of other Fa‘afafine provided her guidance to grow into a strong and confident Trans woman:

…the kind of moral support that … it took for me to be strong and confident as a trans woman that I am today, I would have never received in my family. And I know they love me dearly, but they would have never understood that because…they’re not Fa‘afafine, and none of them are. And as much as they want to understand and want to support me, they will never truly do. And because I have… chosen family with other people that [I] truly identify with… I get to bring in the support that I never had in my given family… for me, that’s grand. Emotionally and mentally… it’s therapeutic… as a Fa‘afafine, I know that [conversations had in chosen family] are important and necessary for a family that has… a Fa‘afafine [or trans person], living in their family, but would never happen because no one knows how to navigate it except for maybe the trans person in the family.

Despite having good relations with her given family, Nafanua’s chosen family afforded her space to have conversations about being Fa‘afafine and Trans that she would not have received otherwise from her given family. She described her chosen family as emotionally and mentally therapeutic because they provided culturally grounded support and resources that aligned with her identity as Fa‘afafine. This was a common experience among participants when asked about how their chosen families contributed to their health. Generally, chosen families contributed to participants’ well-being as chosen families provided a place to share experiences, find refuge from familial rejection, and practice ceremony among QTPI. Chosen family was one of several ways in which inágofli’e’ and alofa were nurtured by QTPI that promoted their health and overall well-being.

3.10. We Need to Be Careful and Have People Who Have Our Backs and Support Us

Some QTPI were also able to nurture and find inágofli’e’ and alofa in community spaces. Puntan, a non-binary and Tinalao’an participant, shared how QTPI experienced oppression from other PI causing disconnection from the larger PI community and prompting personal questions of belonging. When asked what cultural practices they felt could improve QTPI health, Puntan noted community care as an important practice:

… being Queer and Trans PI, you do get secluded or...pushed away in a box from PIs who are straight and cisgender. So that’s why I would put… an emphasis on community care because our community has been shamed, has been oppressed a lot…I would say more because of our gender identities and sexual identities… we’ve had to search harder for people who identify similarly and accept us because we’re not accepted by PIs as a whole…there’s still homophobia, transphobia, phobias are still very prominent within Pacific Islanders… Being excluded from your people because of your gender identity and sexual identity definitely adds a lot more strain on the mental, like, “oh, aren’t these my people, this is my culture too,” you know? That’s why I would put more of an emphasis because we need to be careful and have people who have our backs and support us.

Puntan notes a lack of inágofli’e’ from PI communities for QTPI that causes greater mental stress. They see “community care” as a way to create spaces to “have people who have our backs and support [QTPI]” that counteract the policing and oppression of QTPI within the broader PI community. Ultimately, Puntan shares that QTPI create community through spaces and relationships in which they are celebrated, appreciated, and seen, and that allow QTPI to give and receive care by other Trans and Queer people. It is through this reciprocity of care between QTPI and fellow Queer and Trans community members that inágofli’e’ and alofa are facilitated and nurtured. Many participants were able to find and nurture inágofli’e’ and alofa through chosen family and community they met in diaspora. Some participants who discussed diaspora felt tensions between the resources and community found in diaspora and a desire to return to their Indigenous homelands.

3.11. Being out Here, It Was the First Time I Felt Liberated to Be Myself…

Though diaspora was a place where many participants nurtured inágofli’e’ and alofa within community, chosen family, and socially accepting spaces, some participants also felt tension between having needs met in diaspora and a longing for their ancestral homes. Sirena, a Gela’ woman, described the reassurance and validation she experienced residing in Washington state. Sirena described the power of living in diaspora—that being in Washington affords her liberation, the ability to publicly express her QTPI identity and intimacy with her partner, and a supportive chosen family and environments that signal LGBT belonging. She notes the tension she feels between longing to return home to Guåhan and the inágofli’e’ she has found in Washington state:

I feel like a lot of the community out here has been my chosen family… you have the freedom to choose… who listens to you and who just supports you… Being out here, it was the first time I felt liberated to be myself… it was the first time, my partner and I actually got to hold hands on the street,… Going to Capitol Hill and seeing… the [pride] flag is everywhere. You just don’t see that back home … It’s such a big thing for me and my partner to, like, think about when…we have a longing to go home and to be with our family.... But oftentimes our relationship and our health is our number one priority. And this is what we think about.

Sirena found community and social spaces in diaspora that allowed her to express intimacy with her partner publicly. Through both chosen family and belongingness signaled through built and social environments in Washington, such as pride flags around the city, Sirena found the liberation to express intimacy with her partner freely in public. The liberation experienced through the inágofli’e’ they felt in diaspora promoted their well-being and relationship’s health. Though this story was unique to Sirena, several other participants discussed being able to access gender-affirming care and an ability to “live authentically” in diaspora. Several participants described their Indigenous homelands with tension because of how restraining their spaces and communities could be. Sirena discussed the sources of this tension and what she would lose if she moved back to Guåhan:

How much will we be losing? …That sense of…quiet acceptance …saying it’s OK to be who you are and to be with the person that you choose to be with… that has contributed so much to my mental health, my emotional health, my spiritual health… It has freed me from having all this negative energy in my mind…where I could now allow for more beautiful things in my life… That’s like the biggest thing that I’ll lose…I’ll lose people genuinely asking me questions like…When are you going to get married?...start a family? … Whereas back home, you know, granted, my family and my partner’s family have definitely come to terms a lot with our relationship… at times it’s still really hard. They’re very focused on… like son and a daughter in law…grandkids… they have only been exposed to that one view in life… I just felt it was gonna go back to being hush hush…

Through supportive environments and communities in Washington, Sirena found inágofli’e’ for her QTPI identity, which provided mental relief that liberated her to share intimacy with her partner. This liberated feeling was contrasted with the restrictive feelings from social pressures she experienced in Guåhan, particularly those imposed by her family. For Sirena, living in diaspora improved her mental, emotional, and spiritual health because of the inágofli’e’ she was able to nurture through the “quiet acceptance” she experienced in WA. She connected the uneasiness she felt when thinking of moving home to the heteronormative expectations from her family and community in Guåhan. In diaspora, she feels her community validates the futurity of her and her partner’s relationship and their desire for a family. In Sirena’s reading of the invalidation of their relationship, this rejection by her family and some CHamoru people who also espouse colonial Christian values that center heteropatriarchy is due to their perceived inability to provide descendants or “extension[s] of [their] lineage”. Her family and fellow PI community invalidate their relationship through a heteronormative consciousness where heterosexual intimacies are viewed as the only viable way to provide descendants. In these ways, Sirena and her partner worry they will lose the inágofli’e’ they nurtured in diaspora when they return to Guåhan. Sentiments about losing inágofli’e’ and alofa were described by several participants discussing tensions in relation to living in their Indigenous homelands. The resources and community QTPI find in diaspora allow them to foster inágofli’e’ and alofa to restore connectedness to the parts of their QTPI identities needed to maintain and promote their health and well-being.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to examine cultural components for health promotion in QTPI communities. Our findings offer insight into the pathways by which colonization drives dis-ease—imbalance caused by disruptions to one’s Indigenous ways of being (Walters et al. 2010)—that generates ill well-being for QTPI. Specifically, we illustrate how dis-ease limits QTPI’ connectedness to their families, communities, and cultural knowledge that drives experiences of ill well-being. This holistic approach to indigenous wellness that centers balance and harmony between oneself and their culture, family, and community has been identified by Indigenous scholars as fundamental to Indigenous health promotion as it is common among Indigenous epistemologies of well-being (Pihama et al. 2020; Spencer et al. 2023; Thomas et al. 2021; Ullrich 2019; Walters et al. 2010, 2020). We also found that QTPI who fostered inágofli’e’ and alofa in their lives had better well-being and the ability to combat the dis-ease they experienced. The long-term survival and resilience of Indigenous peoples requires the continuous growth and development of Indigenous knowledge systems, which facilitates the colonial resistance that prompts anti-colonial recovery (Diaz 2011b). Inágofli’e’ and alofa are examples of cultural ways of being that promote anti-colonial recovery as QTPI have found ways to navigate, nurture, and center these Indigenous ways of being to facilitate healing of their historical and embodied traumas. For QTPI participants, the promotion of health and wellness for many grew from their embodiment, practices, and experiences of inágofli’e’ and alofa. These findings have profound and positive implications for QTPI health promotion and offer opportunities to provide successful clinical, community, and policy interventions that address colonization as a root cause of ill well-being for QTPI.

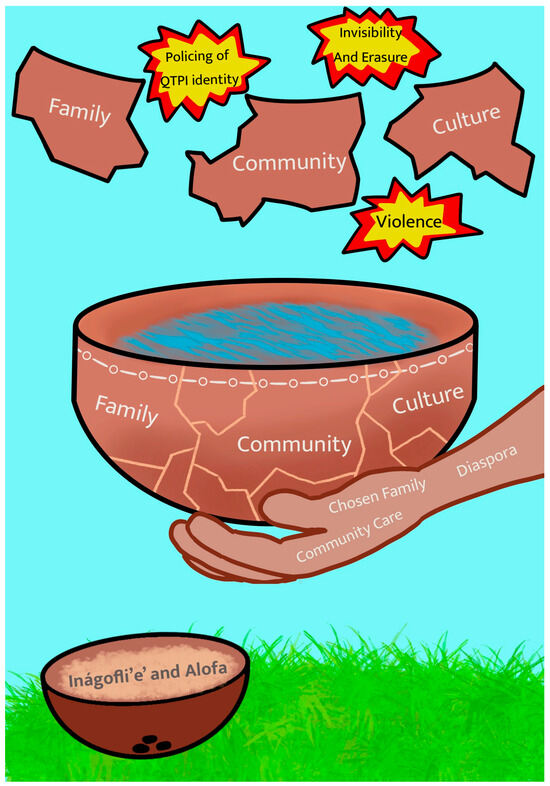

4.1. Developing a Model for QTPI Health and Well-Being through Inágofli’e’ and Alofa

There is a scarcity of conceptual models that center Indigenous knowledge and determinants of health for PI communities, especially those who identify as Gela’, Tinalao’an, Manmalalahi, Manmalao’an, Mamflorita, Machom, Fa‘afafine, Fa‘atane/Fa‘atama, and QTPI. To address this gap, we have generated a community-centered conceptual model using CHamoru pottery as a metaphor for QTPI health (see Figure 2). Historically, CHamoru clay pots were used to carry food and water, to cook, and for ceremonies and were adorned with clan symbols and motifs from the environment etched onto their surface (Moore 2022; The Guam Museum 2023). Across the Pacific, PIs find connections to their ancestors through physical artifacts, including tools and art which comprised everyday life for their ancestors. It is through these cultural items that PIs establish cultural and ancestral connections while also learning about the values and activities which informed the lives of their ancestors.

Figure 2.

A community-centered culturally grounded QTPI health promotion model.

Our model utilizes the metaphor of repairing a clay pot by joining its shattered fragments to represent relationships to components we have found that detract and contribute to QTPI health. In this metaphor, QTPI connections to their culture, their families, and their communities are the clay pot pieces that have been broken by dis-ease, specifically colonial disruptions to inágofli’e’ and alofa. The resin in the bowl next to the pot represents the mechanism we have identified that restores the pot or QTPI connectedness with these sources of health and well-being for QTPI, inágofli’e and alofa. Through the joining of these fragmented pieces, the clay pot can be whole once more, and while the clay pot may not hold the same shape or appearance, it takes on a new life and meaning through the reunion of its shattered pieces. It is through Indigenous connectedness and nurturing inágofli’e’ and alofa that the clay pot’s fragmented pieces can be whole once more.

The Indigenous Connectedness Framework suggests that Indigenous people’s connectedness—the strength and quality of Indigenous people’s relationships—to their environments, communities, families, ancestors, and cultural ways of being are essential to promoting Indigenous health and well-being, beginning in childhood (Ullrich 2019). Connectedness to these sources of Indigenous well-being are interconnected and determine the extent to which Indigenous peoples experience dis-ease in their lives. Though not identified as specific to QTPI, Hilitai describes the dis-ease that contributes to diabetes through imbalance in the diet and the disruption of food traditions. Disruption to food sovereignty—Indigenous rights to healthy and nutritious foods and agency over the determination of their food systems (Blue Bird Jernigan et al. 2021; Chung-Do et al. 2019)—can alter the health-promotive power of PI cultural practices and traditions around food. This disruption generates disconnection from traditional foods and food systems as medicine via land displacement and the introduction of and over-reliance on imported and processed foods (Beebe et al. 2020; Chung-Do et al. 2019; Ho-Lastimosa et al. 2019; Spencer et al. 2020). The dis-ease caused by the disruption of food sovereignty is further exacerbated through intersectional oppression that contributes to the displacement of QTPI from their Indigenous homelands.

Through intersectional oppression (Crenshaw 1990), QTPI must face challenges to displacement from militourism and lateral oppression. As we learned from Sirena’s story, QTPI experiences of lateral oppression from their families and communities within their Indigenous homelands pressure them to find support and belonging elsewhere. Like other PIs, QTPI face land displacement caused by settler land annexation and economic stress perpetuated by militourism (Young 2020; Trask 2001; Camacho 2015; Spencer et al. 2020; Camacho et al. 2022). This displacement disconnects PIs from their lands and disrupts indigenous food systems and traditions that are needed to maintain their well-being (Chung-Do et al. 2019; Beebe et al. 2020; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2020). In culmination for QTPI, militourism and lateral oppression operate synergistically to displace and disconnect QTPI from their land and the food it provides. Thus the dis-ease that disrupts QTPI’ relationship to their land contributes to the disruption to their food traditions and agency over their food systems that perpetuate physical health challenges QTPI experience, like diabetes.

In our study, colonial disruptions caused dis-ease for QTPI with their families, communities, and cultures. In our metaphor, colonization is represented by the shattering of the pot through the policing of QTPI identity, invisibility, and erasure achieved through epistemicide and violence. Our participants discussed how they were often not viewed as part of their Indigenous communities because of how their kin or communities perceived their QTPI identities. These colonial disruptions to gender and intimacy through epistemicide were noted by Gadao. The destruction of cultural knowledge, coupled with social and systemic control of gender and intimacy through institutionalized and systemic colonialism described by study participants, have been well documented and discussed by many QTPI community leaders, Indigenous health science scholars, critical Indigenous studies scholars, and Indigenous feminist scholars both within PI communities and other Indigenous communities (DeLisle 2019; Diaz 2010; Fieland et al. 2007; Hamer et al. 2014; Kasee 1995; Osorio 2021a; Pihama et al. 2020; Teves 2018; Walters et al. 2006). For QTPI, dis-ease is rooted in the epistemicide and suppression of their culturally significant roles and space in their respective communities.

The erasure and epistemicide of QTPI roles operate synergistically with lateral oppression to generate dis-ease for QTPI. The lateral oppression experienced by QTPI from family and community—specifically in the forms of identity policing and violence—is rooted in the disruption of QTPI cultural roles and histories. This is similar to the occurrence of lateral oppression of Two-Spirit communities’ genders and intimacies (Fieland et al. 2007). Many participants expressed how their genders or intimacies were policed either by family, kin, or Indigenous community through violence or rejection. Violence and physical safety threats impacted several participants and have been observed as a health disparity among PIs and other Indigenous communities who identify as Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit (Choi et al. 2021; Dykhuizen et al. 2022; Lehavot et al. 2009; Price et al. 2021). For example, in a national mental health survey conducted in 2021 by the Trevor Project of LGBT Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) youth, 22% of PI and Native Hawaiian respondents reported having experienced physical harm or threats related to their gender or sexuality, the highest proportion reported among all AAPI groups presented in the study (Price et al. 2021). In addition, compared to all AAPI groups, PIs and Native Hawaiian respondents experienced the highest proportion of discrimination based on gender identity (77% ) and sexual orientation (65%) (Price et al. 2021). Thus, with these survey findings, a growth in violence and political attacks against Queer and Trans communities in the US, growing accounts of missing and murdered Two-Spirit people, and the commonality of violence noted and experienced by our participants, violence prevention must be prioritized as a health research and policy issue for QTPI communities (Park et al. 2021; Balsam et al. 2004; Satter et al. 2021).

As we observe in the contrasts between Tilafaiga’s and Nafanua’s stories, experiences of familial connectedness vary between QTPI and confirm previous studies’ findings on family connectedness as a determinant of dis-ease and driver of well-being among Indigenous communities (Fieland et al. 2007; Handy and Pukui 1953; Kanuha 2005; Pukui et al. 1972; Ullrich 2019). As identified by the authors and CAC members for this paper, family is at the center of Sāmoan and CHamoru cultural ways of being and in turn is essential to CHamoru and Sāmoan QTPI well-being. Though many QTPI recounted stories of hardship in relation to their QTPI identities, many also discussed ways they survived and practiced resilience in the face of disconnection.

4.2. Facilitating Indigenous Connectedness through Inágofli’e’, and Alofa

QTPI discussed the importance of inágofli’e’ and alofa in facilitating Indigenous connectedness to family, community, and culture. In our metaphor, inágofli’e’ and alofa represent the resin that re-joins the shattered fragments of pottery. In their absence, QTPI, like the fragmented pieces, remain disconnected from their families, communities, and cultures. Inágofli’e’ and alofa are relational ways of being that are rooted in Indigenous worldviews of intimacy and love that have the power to restore Indigenous connectedness. Relational ways of being have been identified previously as a primary mechanism by which CGHI promote health for Indigenous populations (Walters et al. 2020). QTPI in our study nurtured these ways of being through chosen family, community care, and indigenous mobilities to mold, mend, and repair their connectivity with family, community, and culture. In returning to our model, like the hands that embrace and join the pot fragments together with the resin, these modes facilitate greater connectedness by providing sources of inágofli’e’ and alofa.

Chosen families have been identified as an important determinant of health for Queer and Trans communities across their life course (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2014, 2015; Huynh 2022; Jackson Levin et al. 2020). The Trevor Project also found that among PI and Native Hawaiian youth, 34% and 57% were not out to at least one parent about their sexual orientation and gender identity, respectively (Price et al. 2021). In addition, only 30% of PI and Native Hawaiian youth in their survey reported that their family were LGBTQ-affirming (Price et al. 2021). AAPI youth who participated in the study and who lived in an LGBTQ-affirming household had a lower proportion of suicide attempts in the past year compared to those who did not (Price et al. 2021). For Indigenous communities however, family connectedness can extend beyond one’s given family to non-blood relations with whom they share deep cultural and spiritual connections (Ullrich 2019). In our study, participants identified that their chosen families facilitated greater familial connectedness by nurturing inágofli’e’ and alofa that provided supportive and safe spaces for QTPI identity development, cultural practice, and cultural knowledge and resource sharing. Nafanua’s story shows that even in supportive given families, QTPI still need chosen family to receive inágofli’e’ and alofa that their given families are unable to provide because of their lack of QTPI-specific lived experience and knowledge. To address the mental well-being disparities and familial disconnectedness for QTPI youth, CGHI should provide opportunities to build and nurture chosen families with other QTPI.

In addition to chosen family, our study identified community care as a significant facilitator of Indigenous connectedness. Puntan described community care as an act of resistance to oppressive forces in the larger PI community by providing mutual support for QTPI. Community care is a critical survival strategy among PI, Indigenous, and marginalized communities. These communities, outside of hierarchical structures of state recognition, care for and nurture each other when existing systems fail to meet their needs (Hobart and Kneese 2020; Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018; Young 2020). For QTPI, community care takes seriously the negative implications of when community connectedness and support are withheld for QTPI from the larger PI community (Young 2020). Community care nurtures inágofli’e’ and alofa and fosters counter-narratives that resist the violent and hegemonic rhetoric of homophobia and transphobia, which limit QTPI cultural belonging and generate feelings of cultural disconnectedness as described by Puntan. Community care also has the potential to promote connectedness in the realm of intimate and affective labor, recalling Sina’s desire for Fa‘afafine to be seen beyond the existing stereotypes of Fa‘afafine as caretakers or entertainers. Sina’s desire poignantly acknowledges the racialized and gendered hierarchy of care among PIs, where care work is rendered undervalued, feminized, and disproportionately reliant on femme and Queer labor (Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018). Sina’s story reminds us that community care must be more than a transactional service to community but a radical act of solidarity and relationality that requires a reckoning with current existing structures of care and its inequities.

Community and social support are known to promote the well-being of other Indigenous Queer and Trans communities, specifically Two-Spirit communities (Elm et al. 2016; Walters et al. 2006), and in the broader LGBTQIA+ community (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2014, 2015). Like chosen families, QTPI found community care repairs Indigenous connectedness because it provided safe and supportive spaces for QTPI to nurture inágofli’e’ and alofa for each other through collective care. Community spaces nurture QTPI well-being by not exclusively providing inclusive spaces to practice cultural ways of being and imagine futures of liberation. For example, Guma’ Gela’ provides nurturing community spaces for Queer CHamorus to foster the connection and expression of CHamoru Queer and Trans experiences through interdisciplinary artistic expressions drawing from their connection to culture and ancestors (Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum 2020). Guma’ Gela’ hosts workshops, exhibits, and inclusive spaces for Queer and Trans CHamorus to learn weaving, language, and cultural practices. Through collective artistic expression, like through their exhibit at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum Guma’ Gela’: Part Land, Part Sea, All Ancestry, Guma’ Gela’ provides opportunities to heal historical trauma and imagine futures rooted in Indigenous values, body sovereignty, and self-determination for Queer and Trans CHamorus (Goh 2023). During COVID-19, Guma’ Gela’ created virtual spaces for Queer and Trans CHamorus to gather, create, share stories, participate in ceremony, be in community with each other, and connect with Queer CHamoru elders. In a time when intimacy was challenging for the community to access due to social distancing policies, Guma Gela’ created a community zine about CHamoru love, sex, and intimacy that fostered Indigenous connectedness among Queer and Trans CHamoru people (Velasco 2020). By creating, gathering, and sharing art pieces and stories of Queer and Trans CHamorus, Guma’ Gela’ demonstrates how collective creative community spaces for care nurture inágofli’e’ and restore cultural and community connectedness and promote QTPI well-being.

UTOPIA WA’s Sex Worker Empowerment Initiative (SWEI) recognizes the lack of infrastructure and resources supporting QTPI sex workers in Washington. UTOPIA WA in turn provides safe sex and personal safety kits and hosts the TransAction Support Group, a support group for Trans, gender-diverse folks, and sex workers (UTOPIA WA n.d.). Regardless of state or federal support, SWEI is a powerful example of community care. This is particularly relevant as SWEI served as a crucial resource during the COVID-19 pandemic when in-person sex work was limited due to the pandemic and online sex work was threatened by federal legislation proposing to criminalize sex work. Federal legislation, such as the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (FOSTA-SESTA), shut down platforms where online sex workers were able to find and meet clients, consequently restricting the ability of sex workers to earn income to provide for themselves (Blunt and Wolf 2020; Tripp 2019). In fact, evidence supports that FOSTA-SESTA, counter to their intent, worsened online sex trafficking and caused substantial harm to online sex workers by removing valuable safety and virtual communication tools shut down by federal policies (Blunt and Wolf 2020). Incorporating community care and harm-reduction principles, SWEI provided community care to de-stigmatize and advocate for the decriminalization of sex work through the centering of sex workers’ autonomy and well-being (Abel and Healy 2021; Yandall et al. 2021; UTOPIA WA n.d.). The spaces that Guma’ Gela’ UTOPIA WA create allow QTPI to access community care to promote their health through promoting inágofli’e’ and alofa as cultural ways of being and restoring connectedness to culture and community. CGHI should learn from our community partners’ existing practices and continue to provide and foster community care among QTPI within their communities.

Finally, participants identified living in diaspora as promotive to QTPI health. However, the ways that living in diaspora facilitated Indigenous connectedness were complex. Several participants pointed to ease in healthcare access and medical procedures, such as gender-affirming care, while living in diaspora that improved their well-being as opposed to their respective homelands in Guåhan or Sāmoa, where the same access is not available or limited. Gender-affirming care, community, and social environments in diaspora allowed QTPI to “live authentically” or experience “liberation” in ways that validated their QTPI identities in their entirety. Specifically, they were able to nurture inágofli’e’ and alofa in these spaces that honored their QTPI identities by centering the interconnectedness of the ways they embodied their Indigeneity, gender, and sexuality. Statements such as those by Sirena articulate the inequities in access to affirming communities, environments, and resources between the continental US and Oceania, facilitated by settler colonialism. Though physical distance from one’s Indigenous homelands generated a source of tension for many participants, living in diaspora afforded participants well-being that they were unable to experience in their homelands.

Oceanic voyaging traditions of Pacific peoples point to the ways in which Indigeneity and Indigenous connectedness can be fostered in diasporic and mobile PI communities (Diaz 2011b, 2015). For QTPI and other Indigenous Queer and Trans communities, Indigenous connectedness is facilitated through diaspora because it allows safe and nurturing spaces for Queer and Trans Indigenous people to strengthen connectivity between their sense of Indigeneity and the ways they practice and embody intimacy and gender (Teves 2018). The power of Indigenous mobilities in promoting Queer and Trans Indigenous communities’ well-being has been shown in Two-Spirit communities (Ristock et al. 2010). In a qualitative study completed by Rainbow Health Ontario, Two-Spirit communities living in diaspora found greater access to healthcare, community, and cultural resources that promoted their well-being that were not accessible in their Indigenous homelands. It also offered an escape from social circumstances that took away from their well-being (Ristock et al. 2010). Honoring the historical traditions of QTPI voyaging may help to facilitate better connectedness through CGHI.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is limited by the parameters of its sampling scope. Our study only samples QTPI communities living in Washington state. Though this local specificity aligns with Indigenist collaborative research and community-based participatory research’s principles (Belone et al. 2016; Wallerstein and Duran 2010; Walters et al. 2009), this limits the generalizability of our findings. Future studies could explore PI individuals living in their Indigenous homelands and other spaces where QTPI gather in diaspora. Furthermore, our study only examined the experiences of CHamoru and Sāmoan QTPI. Future studies should also explore other QTPI communities as PI experiences vary greatly along dimensions of citizenship, political status, and racialization (Arvin 2019; Diaz et al. 2020; McElfish et al. 2016; Morey et al. 2020, 2022; Na’puti and Bevacqua 2015). We hope that this study is transferable to the experiences of QTPI more broadly and encourage other QTPI communities to draw from this model and build upon it from their epistemologies.

Though our study findings were validated through collaborative efforts with our CAC, our research team acknowledges how our identities as Queer, Trans, Indigenous, and PI contribute to our interpretation of our findings. We do not see this as a disadvantage in relation to bias but rather a privilege that allows us to share and interpret the stories bestowed upon us by our community members more intimately. It is our responsibility to care for and steward these stories ethically for the benefit of QTPI communities (Smith 2021; Wilson 2008). Despite these limitations, this study is one of the first of its kind—one that explores the health experiences and culturally rooted health promotion within QTPI communities. Though our primary research question did not explore violence specifically, the prevalence of violence amidst our participants’ stories was alarming. We suggest future studies focus on violence as a health outcome for QTPI communities and violence prevention for QTPI communities.

5. Conclusions