Abstract

TikTok is the fastest growing short video application and immensely popular with younger generations to express their thoughts, ideas, and most relevant to this issue, their identities including mixed-race identity. This paper asks: How did young mixed-race people choose to express their identity on TikTok in the #wasian trend and how does the app shape these mixed-race identity expressions? The answer lies in how the emotional affordances of TikTok app itself shape how it is used by creators in mimicking and mimetic ways and how people respond, through video and text. The article argues that the #wasian trends reinforce the racial and genealogical legacy of mixedness, often through showing parents or blood relatives, which is in creative tension with simultaneously remixing and asserting racial multiplicity. The claim to wasianess moves the private sphere (bedroom culture, family and notions of race) into the public and in so doing creates new potentialities for the creation of a global #wasian community on TikTok.

1. Introduction

This paper examines how young mixed-race Asian people are using digital social media, such as TikTok to trace their cultural and racialized roots in order to create, challenge and transform transconnected meanings of mixed-race. The paper specifically focuses on Asian + White mixed-race people by analyzing the trend of ‘#WasianCheck’ on TikTok to create cosmopolitan and communal notions of what it means to be an Asian mixed-race person across the globe. #Wasian (typically understood as East Asian + white) has recently been reimagined as #blasian #Wexican #indoasian, etc. and applied usually to first generation Asian+other mixes. While the term is now being used in transnational ways on TikTok, it interestingly both removes people from their immediate local settings (unless they hashtag their location) and reinforces geographic location as the algorithm in the app directs geographically ‘local’ as well as international content to your ‘For You Page’ (FYP—like a home page) blending local and international content during consumption. The digital presence of mixed-race content is not new on digital platforms. YouTube has long been a place where mixed-race/hapa expression has happened (Lopez 2019, p. 277) but what is interesting is that the word ‘hapa’ has declined in use on social media and on TikTok the term #wasian has gained in popularity across the app. Usually #wasian is also used alongside #mixed #mixed-race and #Asian; all used together to signal the salience of mixed-race Asian identity. #Wasian is a new expression of mixed-race Asian identity which has emerged relatively quickly largely spread and institutionalised through social media interactions on digital platforms like TikTok. This paper asks: How did young mixed-race people choose to express their identity on TikTok in the #wasian check trend and how does the app shape these mixed-race identity expressions?

During the Coronavirus pandemic, the growth in the use of social media skyrocketed and this has brought new forms of entertainment and expression (often used by young people). This ‘very online’ generation has created memes, sounds, dances and trends that have gone viral and moved quickly and widely across the globe via social media such as TikTok. While memes and videos on TikTok may seem trivial, they provide key data on how young people across the world (including the Transpacific between Asia and the West) present, challenge and negotiate mixed-race identity. This paper examines the #wasian trend on the TikTok platform that creates new expressions of mixed-race Asian identity across the world, through an analysis of two of the most popular ‘sounds’ on TikTok: (1) “Hey Yo! Wasian Check” and (2) “Can we switch the language?” sound creation and trends. It illustrates how these two sounds within the #wasian check trend on TikTok create and reinscribe identities using racial concepts and term and as possibly taking the lead as a new term to refer to Asian + Other mixes.

Sounds, considered the backbone of TikTok, are recorded audio tracks which run behind the short videos that can easily be made, edited and uploaded via TikTok. Sounds can be combined with new and original video content and reused giving rise to ‘trending’ sounds which go viral or are copied over and over. New sounds can also be recorded by creators. The two sounds analyzed here are original sounds and are in English when people actually speak on them. For many sounds on TikTok there is no actual speaking by those starring in the videos who are reusing a pre-recorded sound made by other content creators, instead they reuse the ‘sounds’ of these 2 trends and use actions, objects, and people to prove their point about being #wasian. In this sense, TikTok is quite interesting because there is often no real spoken language by the content creators and/or reusers but instead they tend to use pre-recorded sounds with English being spoken usually over background music, which is usually contemporary, upbeat (often hip/hop or rap) music with a good beat. In part, TikTok’s global success can be attributed to its use all over the world because you can use English sounds without actually being able to speak English and the focus is primarily on bodies/faces, bodily movement, video transitions, and visual appearance.

Interactive communicative technologies have given rise to increased digital social interactivity and have intensified mediated emotional interaction and relationships. The socio-emotional organization of on-line interaction orders invites us to reimagine the emotional forms of expression and the social assessment of their authenticity (King-O’Riain 2021). These interaction orders on these new digital media platforms take many forms. One common type is that of the parasocial relationship, which is typically a one-way emotional relationship between a celebrity (e.g., a popular music star) and their fans (Yan and Yang 2021). These unidirectional relationships contain imagined connections that fans feel towards their favourite stars. For social media influencers and content creators (micro-celebrities on a smaller scale) can also work to cultivate ‘keeping it raw’ or curating authentic emotional performances on social media to encourage parasocial relationships with their followers (Reade 2021). A second type of interaction order on digital media is used more in the private sphere between non-celebrities such as in synchronous emotional streaming where digital technology (Zoom, Facebook, Skype) is used to stream emotions across transnational spaces in real time (live) and is a form of two-way communication, unlike the parasocial interaction order (King-O’Riain 2015, p. 271). A third type of interaction order also seems to be emerging on apps like TikTok where the act of mimetic copying of content or duetting content (where the original video is viewed on a split screen alongside a response video) and commenting in dialogue with it in a two-way communication across geographic and cultural boundaries is a form of considered asynchronous transconnective digital practice. It is transconnective across transnational boundaries in part through the discussion of what it means to be wasian and how that is mediated through frequent use of digital media technology to create a sense of belonging through tele-intimacy not in real time but asynchronously through pre-recorded short video copying, exchange, and commentary. Often a sense of #wasian community was gained from watching or duetting or liking videos and commenting at length on them or copying them with original content from reusers’ own lives across transnational spaces.

This paper argues that the salience of these #wasian trends are largely based on 3 processes associated with TikTok and shaped by the particular emotional affordances of the app, which have grown in importance as the platform has expanded its reach. In particular, three elements facilitated the rapid emergence of these new mixed-race identities: (1) the move of private ‘bedroom’ culture into the public sphere; (2) the shift in the TikTok app from provision of mass entertainment to emotional connections within user interactions; and (3) the shift from mimicry/memes into community creation through tranconnective digital media practices, where users were able to discover, test, confirm and re-combine identities through playful cultural interactions.

Performances and practices of mixed-race identity on social digital media, like film and TV, have transformative potential to reinvent social understandings of racial categories through an examination of the ‘cultural codes that shape racial understandings’ of mixed-race bodies (Nishime 2020) in this instance, on TikTok. These trends trace the genealogical legacy of mixedness, often through showing parents or blood relatives, which is in creative tension with also simultaneously asserting mixedness. They also crucially grow the online identity narratives and mixed-race community of Asians through likes, shares, and comments creating both symbolic representations of self, but also a form of significant global mixed-race sociality, which combines a confirming of genealogy (tracing parentage, discussion of blood lines, etc.) with a creative re-mixing of mixed-race Asian identity. It is almost a necessary move to show your parentage (or actual Asian parent/s) in order to claim remixed wasian authenticity.

2. Origins and Popularity of TikTok

TikTok was the world’s largest short video (15–180 s long videos) digital media platform in 2021. TikTok’s meteoric rise in number of users and visibility during the COVID pandemic across the world went from 381 million users in 2019 to 1 billion users in 2021. TikTok started out as Musical.ly in 2014 by making short lip-syncing videos available to people. Musical.ly transitioned to TikTok outside of China in 2018 and within China known as Douyin (both owned by ByteDance) as a new short video sharing social media platform. It went from 2014’s obscure app, mostly used by preteens, to 2020’s most downloaded app” (Savic 2021, p. 3188). The app’s popularity was based in part on the fact that it integrated the app creators, the users (mainly young people) and nonuser (parents) as active contributors to the social construction of TikTok… (Savic 2021, p. 3189).

Chinese owned, TikTok is also part of the de-westernizing of platforms across the world (Davis and Xiao 2021) and is often touted as leading the way in internationalising the internet. TikTok is the largest Chinese platform to move into the western markets. Before 2020, TikTok was primarily seen as a business miracle, but in 2020 this shifted and became framed as a political issue. Since 2020, TikTok has been increasingly embedded in the escalating geo-political tensions between China, the US and India” (Miao et al. 2021, p. 1). The Chinese ownership of TikTok also attracted controversy when in August 2020 President Donald Trump threatened to ‘ban’ TikTok in the USA declaring it a threat to national security and personal privacy amidst rumours that TikTok were collecting face scans from the users of the app. While never proven, this ban was later overturned by President Biden in June 2021.

While TikTok itself has been the object of political controversy, it can also be used for political organization and has been a key tool to organize nascent social movements building on the success of the #MeToo, #occupy #BLM movements, which often began and depended heavily on digital spaces (data activism) or #hashtagactivism (Wonneberger et al. 2021) to spread their message and to mobilize social action. Despite the political controversy, TikTok has thrived and is used particularly by younger demographics across the world (Zeng et al. 2021) and is having a powerful influence on the emergence of new identities within this transcultural, and specifically Transpacific, space.

2.1. TikTok and the Public Sphere

Kennedy (2020) argues that TikTok’s success is in large part because it was a:

…celebration of girlhood in the face of the pandemic, and can be seen to contribute to the transformation of girls’ ‘bedroom culture’…from a space pre-viously conceptualised as private and safe from judgement, to one of public visibility, surveillance and evaluation(Kennedy 2020, p. 1069).

The move of bedroom culture from private to public brings with it increasing visibility at a rapid pace to a potentially large audience (public) on social media. Abidin (2020) points out that success “…on TikTok, is focused on how attention economy and visibility labour practices have emerged as a result of the app’s features” (Abidin 2020, p. 77). One of the main reasons that TikTok is so popular is that it is a form of ‘visibility labour’ (Abidin 2016) where “Visibility Labour is the work that social media users perform to be noticed by their intended audiences, comprising self-posturing and the curation of self-presentations to be ‘noticeable and positively prominent’ among viewers” (Abidin 2020, p. 85). Key to this increasing visibility in public is that, “…the TikToker does not merely partake in a popular trend, but also participates, self-expresses, and identifies with a network of like-minded others who share their multiple interest affiliations (Vizcaino-Verdu and Abidin 2022, p. 903). It is this creation of collective identity together which brings private (family, bedroom, etc) culture, in this case mixed-race culture and identity, out into the open by being visible to the public (many others) on TikTok. Within visibility, it is about “cultivating approachability, intimacy and ordinariness in the short video context” (Zeng et al. 2021, p. 3186) in order to increase the number of followers (clout). Wang and Wu (2021) argue that the local context of content production links to local community building using TikTok. They argue that rapid economic and social change along with fast moving technological change shifts the role new digital technologies play in negotiating identities across the world. This has led to an increase in young people externalizing their identities through social media such as TikTok. Saraswati (2021) analyzing the comment boxes under pornography of Asian women argues that, “…the comment boxes that “record” as one externalizes their experience, become a container for the affective excess of the viewers. This container is a “safe” space for the viewers to express, externalize, and experience their feelings—they can do so while remaining within the safety and comfort of their own homes…”(Saraswati 2021, p. 11). Mixed-race identity is also externalized on TikTok and in so doing, makes visible, in public, #wasian identities across the world.

While mixed-race identities across the world have been seen to be context driven, the lived experience and viewing of mixed-race bodies has also moved from film and television platforms to social media video platforms like TikTok and YouTube (Lopez 2019). Within this move, the mixed-race identity, often seen as being about interracial couples and families (DaCosta 2007), has transitioned what may have been a private, personal or family racial identity in the past into the public sphere and opened it up to finding those with common experiences, but also opened it up to public racism and criticism in comments, dueted/stitched (where the original video is viewed alongside a response video) and repeated videos.

In addition, TikTok has created a virtual space that easily reaches across most national boundaries not by replacing the local and national contexts that shape racial and ethnic identities but connecting them through a new, online space with its own conventions, expectations and interaction orders. One effect of the TikTok algorithm observed in this study is that it seems to flatten the geographic locations of users. Content that is thematic (#wasian) can easily flow across national boundaries from Europe, the US or Asia (but not China) without any geographic or local contextual markers unless added by the content creator in the form of geographically specific hashtags (#Irish) or by showing flags of countries at the bottom of the video. For the most part, creators tend to use pre-recorded sounds (except for ‘storytime’ videos), filters and effects on their videos so the accents spoken or place markers may not be geographically or culturally obvious, which led to many followers of the wasian hashtag on TikTok to not really be aware where the video creator resided or which languages or cultures they were immersed in. This may be different than past mixed-race experiences. Lopez (2019) analyzes the mixed-race Japanese American experience online and she writes, “From the networks and affinities we see developing in digital spaces, we can more clearly reposition mixed-race Japanese Americans within a diasporic framework of mixed-race Nikkei, rather than relying solely upon frameworks of nation as sites of belonging, identification and the construction of ethnic community” (Lopez 2019, p. 271). The ability of digital media to cross national boundaries is an example of how these diasporic mixed-race sites of belonging can develop across national and ethnic boundaries within the identification with the #wasian trend on TikTok.

2.1.1. Why Wasian?

The terminology about being mixed-race and part Asian has been shaped by local context and has often been socially constructed and dependent upon the geographic location and social context of where the mixing is happening and what/how individuals are perceived by others within that context. Often this constitutes a social interaction between how mixed-race people saw themselves, how they externalized that identity by making themselves visible and then how those around them (publics) either affirmed, challenged or denied those identity claims. For example, Vietnamese Amerasians (after the Vietnam War) were often seen as ‘War Babies’ who had fathers who were American GIs and Vietnamese mothers who were sexually permissive or prostitutes (Valverde 1992). Mixed-race children in Korea and Japan also bore a stigma of being part of the remnants of war (regardless of the marital status of their parents) and there were many Amerasian and Eurasian children left in orphanages across these Asian countries after their wars were over leaving the stereotype of mixed Asian children in this context as a ‘war baby or a love child’ (Kina and Dariotis 2013). Tracing the genealogy of mixed-race experiences and terminology, reveals much about the diversity of the global mixed-race Asian experiences across time and space (King-O’Riain et al. 2014). Williams-Leon and Nakashima (2001) analyzed important narratives about the mixed-race Asian American experience while Ahn (2015) explored what it means to be mixed-race between Korea and the USA. Being Eurasian in Singapore is explored by Rocha and Yeoh (2021) where they found that, “Mixed identities and identification are crucial, with inclusion and exclusion being strategic and positional, and identities increasingly recognized as complex and multiple, rather than simple and singular” (Rocha and Yeoh 2021, p. 15). Within this, the meanings of mixedness and the borders (both state and cultural/racial) which that they cross are revealed through the lived experiences and social interactions of mixed-race Asians both in Asia (Rocha and Fozdar 2019; Törngren and Sato 2021; Kimura 2020) and in the west (Williams-Leon and Nakashima 2001).

In this research, within the comments under the #wasian check trend, there was debate about the term wasian itself such as: ‘What is wasian?’ “Isn’t it Eurasian?” “are my friends and I the only ones who say hapa instead of wasian?” This is telling about the local context in which viewers are trying to make sense of their mixed-race identity. Niko Katsuyoshi, the creator of the first #wasian check sound, is an American college student now on the east coast of the USA, but those in Hawaii might be more prone to use the term Hapa (coming from the Hawaiian language term ‘Hapa Haole’ meaning part white in a predominantly Asian and Hawaiian context of Hawaii). The term is not without controversy as those of native Hawaiian descent feel the term should not be used by non-Hawaiians or outside of a Hawaiian context. The term hapa is in use both in California and further afield in Japan (See Williams (2017) Hapa Japan book and project for more information). Eurasian (Rocha and Yeoh 2021) is another term that popped up in the discussion in the comments section of the video, which is more commonly used in Singapore, Malaysia and other parts of Asia.

These various mixed-race Asian experiences have been analysed in terms of nomenclature but also mixed-race Asian people are analyzed within the videos based on their phenotypical appearance. Mixed-race Asian representations within popular culture, particularly in film and television, draw attention to the social interaction between the mixed-race body and the viewers and interpreters of that body (Nishime 2020). Nishime writes.

Since race is a social fiction, however, it does not simply exist in specific bodies waiting to be read. Instead, the ambiguity of mixed-race Asian representations resides in the exchange between the viewer and the viewed… While the visual apprehension of race may appear to bypass culture, the study of representations of mixed-race Asians makes apparent the ways in which the visual is constantly mediated by cultural codes. Race appears to exist on the surface of the body for the viewer to scan. On the contrary, the features that signal racial difference are socially determined, and people are trained to prioritize those features as they enter into culture.(Nishime 2020, https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-854#acrefore-9780190201098-e-854-div1-3, accessed on 6 June 2022).

Answering Nishime’s call to try to understand the cultural codes that “inform the readings of racial categories” (Nishime 2020) including those of mixed-race people to de-naturalize race and draw attention to race’s social construction, we see how mixed-race bodies within cultural context can drive the meaning of mixed-race identity not just in film, but on social media such as TikTok when mixed-race bodies are read by and commented on by others.

2.1.2. Emotional Affordances the TikTok Algorithm

Despite the distances and the occasional lack of geographically transparent identities of the users, these new spaces on TikTok are highly emotionally charged and these emotions sometimes form the base of tightly knit communities. TikTok encourages sharing moments and stories from daily life in a way that people “located outside one’s social circle can relate to, (including) the sense of publicness and intimacy simultaneously” (Schellewald 2021, p. 1451) (italics added by author for clarity). Saraswati (2021) asserts that the potentiality of social media does not always have to be within a neoliberal context, but that

Instead, we should consider social media as poetry, when it works as a site to excavate deeper layer of truths through languages that have the capacity to make us feel more and to expand the repertoire of our emotions, and as something that allows us to experiment and experience new, previously inexpressible, never-before felt emotions. Social media as poetry also means that social media, like poetry, should function as a site where we can work through the difficult and impossible emotions and questions we have in and about our lives. Rather than sharing emotions on social media as a form of “investment” in ourselves and others (which is what neoliberalism teaches us), we should approach it as a form of loving interest in each other and in the ecology as a whole(Saraswati 2021, p. 101).

We do see elements of the #wasian trend on TikTok as potential social media poetry (working through emotions, questioning and affirming identities, creating loving interest in others) but it is also important to be clear how the trend is shaped by the neoliberal capitalistic aspects of the app itself as well as how its users understand their content and connections to each other. For example, TikTok networks users together through the algorithm in TikTok’s ability to send content that will evoke emotional response (pressing the heart/like button) based on past use to your ‘For You Page (FYP)’. However, users of TikTok know about the algorithm and strategically curate content and certain hashtags to gain more viewers and to target a certain audience in this case #wasian to target mixed-race Asian viewers and those interested in this issue. This involves presenting the private self in public via TikTok, but as Saraswati (2021) notes, “I refer not to the “private” self as the ultimate true self of the author/Instagram user/trickster/…as if there is such an essentialized self to begin with—but, rather, to the private/privatized neoliberal self(ie) whose performativity needs to be protected to remain entertaining and appealing for it to have any currency and value in the phantasmagoric world of social media” (Saraswati 2021, pp. 95–96).

This curation of mixed-race identity enhances TikTok’s entertainment value but more importantly intensifies the emotional engagement with the platform and other users. In this sense, TikTok is a “representation of reality mediated through the ‘For You’ page, the algorithmic content feed connecting a single user with the broader cultural dynamics unfolding on TikTok” (Schellewald 2021, p. 1451).

Becker (2021) found that ‘performed authenticity’ and intimacy of the Twitter feed bled onto TikTok and created multisocial, engaged relationships with followers to promote collective action (Becker 2021). There were also examples of ‘corroborated authenticity’, which is when a “…corroboration of internal interactions in a particular platform comes from two sources: (1) the presence of related and similar material on the other technological platforms and (2) the connection of the apparently ‘placeless’ digital platforms to a particular…” community (King-O’Riain 2021, p. 2822). In this instance, the repeated streaming, duetting, and reusing of the #wasian sounds and videos on TikTok reinforces the feelings of “…the authenticity or genuineness of the interactions they viewed on-line, which were corroborated by cross-platform viewing…but also by the legitimation of the broader community…” (King-O’Riain 2021, p. 2836). It is through the strength of ‘emotion work’ that collective identities are created (Treré 2020). TikTok in particular is an interesting place to examine this as Barta and Andalibi (2021) find that, “ the affordances, in combination with a ‘just be you’ attitude, inform user perception of both goofy content and ‘raw’ emotionality as authentic. This range of acceptable emotionality (i.e., from goofy to difficult) suggests that normative authenticity on TikTok may make the platform conducive to both the expression of difficult emotions and experiences leading to social support exchange” (Barta and Andalibi 2021, p. 25). It is with this in mind that I examine the social process through which tracing confirmatory racial genealogy and creative re-mixing are reconciled through the particular emotional affordances of TikTok.

2.1.3. Community and the Discovery and Creation of Identities

The social context of use is crucial for TikTok and it is increasingly being used for political commentary, event commentary and political performances. Sánchez-Querubín et al., (forthcoming) argue that many users of TikTok copy and then remix content to suit their needs for expression. They write, “TikTok users practice remix as ambivalent critique. That means they use the app to re-edit, modify, and juxtapose clips from the news and popular culture…” (Sánchez-Querubín et al., forthcoming, p. 2). Most often, the re-working of existing cultural narratives about race and mixed-race were done through mimicking/mimetic appreciation or by duetting or remixing the content. The mimetic/mimicking pattern on TikTok here is ultimately shown to be confirmatory or seeking commonality across various users and their local social and cultural contexts around the #wasian. It is precisely the context of use and the social groups who use TikTok and their co-construction of cultural meanings in reference to mixed-race users around the #wasian trend that created emotional responses shaped by the affordance of the app. Across great geographic and cultural distances there was also a high level of mimicry/memes and the homogenization of practices, emotions, and experiences in TikTok videos, but this also created a mixed-race digital community of sorts through these tranconnective practices.

Young people watch TikTok because they want to see one another and because they want to know that they’re not the only ones who feel a certain way, live a certain way, and experience love and friendship a certain way. They can scroll through the silly dances and personal confessions and think, ‘I have a kitchen like that, a bedroom like that, a hoodie like that, and a mom like that. I guess I am normal. I guess other kids are feeling the same way.’ TikTok isn’t entertainment, it’s community (Long 2020, https://www.commentary.org/articles/rob-long/the-soft-power-of-TikTok/, accessed on 6 June 2022).

For many mixed-race Asian people, they may live in a place where there are few people with similar mixed backgrounds. In this sense, TikTok can provide connective means into the sense of community via social and digital media and confirm feelings like “I have an Asian mom like that and a white dad like that” but maybe I live in Sweden or rural Thailand. In this sense, it offers confirmation of their wasian identity and comfort in the fact that they are not alone. Most of the comments left by people under the videos are complimentary and most are other mixed-race Asian people offering their own backgrounds or supportive comments on the videos. For many of the users, they comment that they have not heard or used the term wasian before, but like it and want to join the #wasian band wagon. It is through this discussion, duetting the video and reusing the sound that they go on to discover, name, confirm, re-mix etc. identities their white/Asian identities on TikTok. This has also led to discussions of gender (where are all my Asian dad/white mom kids at?) and other racial mixing combinations (where are all the blasians at? Where are all the Filipino/Mexicans at?) on the app.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper is based on qualitative content analysis methodology. A sample was taken from TikTok videos posted from November 2019 - November 2021 with a specific focus on two hashtags: #wasiancheck and #wasian and the sounds that accompanied them. I also analyzed the top 10 compilation reels on YouTube made up of TikTok videos stitched together.

The two trends that are analysed here are: (1): Hey Yo. Wasian check… and I was like, yo… (Sound: ‘Wasian Check…but different’ by Niko Katsuyoshi), which by November 2021 had 9919 videos remade with the sound and; (2) the Sound labelled ‘wasian check’ by avaxwilkinson within TikTok (containing music from It’s Everyday Bro by Jake Paul) which had 3326 videos made using this bespoke sound as of 5 November 2021.

These two trends are interesting because while they both ride on the wasian hashtag, they prompt differently curated displays of mixed-race identity and they present quite different affordances for representation and interaction. The first, the ‘Hey yo, wasian check’ sound, is based, with no spoken language except for the pre-recorded language on the sound, on a face reveal, while the second, the ‘wasian check’ sound, encourages not only facial/body revelations but also scenes within the home setting with family members, which ‘signal’ Asianess and Whiteness.

Ethical approval was not needed for this project as the content analyzed was deemed to be available in the public sphere. However, I followed the best practice of guidelines for ethical research from the Association of Internet Researchers (2019) and have blurred user names to protect individual users identities where the identity of the user is not expressed in the name (ethnicity, gender, etc.), except in the case where the identity of the content creator, in terms of being the original creator, was crucial to the point being made and I felt that attribution should be given to that content creator (both are over 18 years of age) for being the originator of that particular trend. All of the content viewed from TikTok for this paper was posted publicly and made available to be shared by the content creators, and I have only presented examples where the poster is clearly above the age of maturity set by the app (13 is the minimum age according to TikTok’s terms and conditions). Often parents themselves appeared in the videos and I took this as a sign that parents knew of and approved of the post. In most cases, comments are anonymized even though the usernames often do not reveal personal or locational information. In all cases, the content scraped was analyzed first to insure that ‘no harm’ could come to posters or commenters within this representation of their content and that the content is presented in its intended form. In the next section, I analyze these two trends on TikTok and the responses they elicited from viewers from across the world.

4. Discussion

I now examine how each of the two trends identified above are shaped by the processes discussed above of the move from private to public, the emotional affordances around each and the building of various forms of community through interaction around them.

4.1. Hey Yo, Wasian Check… and I Was Like, Yo…

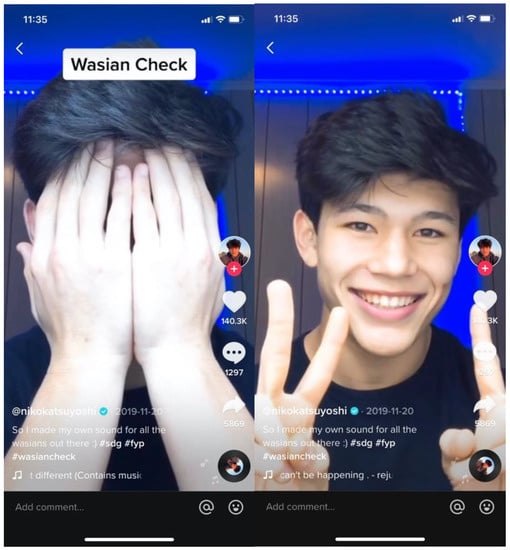

The first trend I analyze on TikTok was started by Niko Katsuyoshi which ran under the hashtag ‘wasian check’ meaning white + Asian. Niko begins with background music of the ‘Grape soda’ song by Rook1e used as the background sound in the video with Niko’s own voice over it. He begins with his hands covering his face while he says “Yo. Wasian check” (See Figure 1)—hiding his face for about 5 seconds and then when he says, “and I was like…” revealing his face (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

#wasian check face reveal.

This basic peek-a-boo type movement is not unusual on TikTok and is used with other sounds and within other dances and trends such as ‘look at my unusual eye color’, ‘before and after makeover’ videos, etc., but in this instance, one reason the trend was popular was that people were curious to see ‘how Asian’ or ‘how White’ mixed wasian people appeared. This is a longstanding trend within the mixed-race experience of being asked ‘what are you?’ or you ‘you don’t look X!’ (see Fulbeck 2006 100% Hapa for examples of this). The trend also encouraged users to reuse the sound (Niko’s voice on the audio saying “yo! Wasian check and I was like… (music)” and to list the parts of their heritage such as #wasian “that’s me!” “I’m Thai and Swedish. What about you?” Nishime (2017) argues that this long-standing fascination with how Asian mixed-race people appear phenotypically has meant that mixed-race people have long been “objects of visual fascination” as people, but also as larger symbols of the nation and globalization (Nishime 2017, p. 139). This has included the exoticization and objectification of mixed-race people as ‘beautiful’ or ‘unusual’. What is different about this trend on TikTok is that it is being created by mixed-race Asian people themselves as a form of performing a visible identity to a large audience (public), across many cultural and national contexts, primarily to confirm the existence of mixed-race Asian identity across the world. There were so many of these videos made that several compilation videos were made and transferred to other platforms such as YouTube (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

#Wasian Check Compilation Videos (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAei7WFbzhs, accessed on 6 June 2022).

4.1.1. From Private to Public

One way that #wasian content creators transform their private family and mixed racial identity into a public identity is by revealing their families through photos of the parents, or by pulling their siblings and parents into the video. When they do this they are making the private domain of the home, family, and racial identity public, which opens it up for positive affirmation or criticism on TikTok.

By tagging these types of videos with the #Wasiancheck, the trend also focuses on the visuality of TikTok (and larger social media landscape) that is described by Abidin (2016) as, “…the work individuals do when they self-posture and curate their self-presentations so as to be noticeable and positively prominent…”(Abidin 2016). On TikTok this can be measured by how many followers that the account creator has or how many times the sound they create has been used, otherwise known as ‘clout’ on TikTok. Both of the trends here are used and added to by mostly young (most are under 30), physically attractive, mixed-race Asian people who are just making themselves ‘seen’ on TikTok. But it is more than just making themselves seen and externalizing their mixed identities and families, they are making the identity of mixed-race Asians or wasians publicly seen as well and creating what it means to be ‘wasian’ through the mimetic reproduction of the videos.

By revealing the face as the self, this trend, focuses on literally making wasianess ‘seen’ on the app. In the face reveal, most comments were directed at the racial phenotype of the person making the video using this sound ‘I didn’t know Asians had green eyes.’ If someone posted using the #wasian but doesn’t appear to be part Asian, some of the comments challenge that identity with comments like: ‘you don’t look Asian’ ‘Looks totally white to me’ etc. Response claims, and duets/stiches (video responses), often responded by having Asian parents or grandparents appear in the response video cited as ‘racial proof’ of being part Asian again moving racialized family members onto TikTok. In this sense, the racial genealogy (parents and grandparents) of the content creator, was used as racial evidence of the claim to being part Asian. The phenotypical appearance in and of itself was not enough, but further proof was needed to make the claim to wasianess ‘authentic’. Given that the app is visually driven, Asian parents and grandparents often appeared in the videos without speaking, and their visual presence seemed to be enough to make the point and confirm the right to identify and be seen on the app as part Asian. This act ironically, centered ‘race’ and genealogy as a way to claim a mixed identity, while at the same time trying to remix what it means to be wasian.

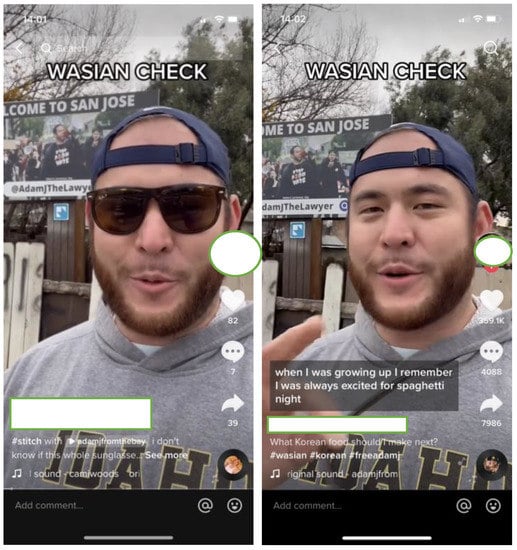

This sound and the trend of the face reveal for mixed-race Asians on TikTok is an example of the intense curiosity in particular about what mixed-race people look like how Asian, how white they look? The opposite is also found on TikTok with the sound ‘looks like cracker to me…’ i.e., looks really white or more Caucasian or looks totally Asian different combination, but all are young, nice looking, and phenotypically mixed looking. It also builds on the interest in how mixed-race people appear phenotypically often differently between siblings who have the same parents with a constant measure of ‘how Asian’ people really look. The #wasian sunglasses reveal trend was another riff on the face reveal. In Figure 3, the video begins with a young, white appearing man wearing a backward baseball cap, sunglasses and a hoodie with a billboard behind him signaling he is in San Jose, California. Because of the sunglasses, you can’t see his eyes, but he has ‘wasian check’ in large letters over his head and he begins to tell a story about how he looked forward to ‘spaghetti night’ each month (at which point he removes his sunglasses to reveal his ‘Asian’ looking eyes) in his house because all the other nights he ate Korean food.

Figure 3.

The Sunglasses Reveal.

Many of the responses, duets and stitches (video response) to this video, were people saying, “wasian what?” And then after the face reveal, “oh, now I get it!” or a look of disbelief followed by thumbs up after the reveal if they were wasian themselves. This type of post increases the visibility of people who identify as wasian by posting stories of family in the public sphere on TikTok (Abidin 2016) and increases the ‘attention economy,’ which increases the number of likes (hearts), comments, forwards/shares of the video making it viral. Niko Katsuyoshi ends his original #wasian check (face reveal) video with the original sound by making the peace sign with both hands something the comment makers and others easily identify as an ‘Asian’ photo bodily action. Many of the comments underneath 1294 comments (and 140,000 hearts/likes) are simple comments on Niko’s appearance “you are so cute” but others draw specific attention to his ‘racial’ Asianess by commenting: “you look full Asian” or refer to him as Asian acting for example, by commenting: “peace signs, very Asian bro!” I argue that all this curated to do ‘race work’ to prove Asianess through phenotypical revelation. By making racial identity public on TikTok, it exposes that same identity to public comment, discussion, and affirmation.

Many of the videos in this trend increasingly bring the background, often a kitchen, living room, or bedroom (from inside a private home), as well as the mixed-race identity connected to it (in the sunglasses video discussion of family dinners cooked by a Korean mother) into the public sphere. While moving from private to a public identity reveal, it also normalizes the sense that mixed-race is an ordinary, approachable and intimate feeling in the videos. It is precisely because it could be any mixed-race person, in any private home in terms of how they imagine themselves, that the videos are popular.

4.1.2. Emotional Affordances

However, the same ability to comment and the support the post, leaves it open to racist comments and trolling. Surprisingly, there were very few racist comments under the #wasiancheck trend as TikTok has lately been trying to crack down on racism, but it still happens from time to time.

Most of the comments on the original video though were affirming in content and nature either through text or emoji emotional expressions (See Figure 4). Text comments were very affirming in tone such as:

Figure 4.

Emoji Comments.

“we should do this bc like white + Asian = me and you”

“Where is my wasian gang at?”

“I’ve been waiting for this for years bro”

“British Indonesian here”

“We Wasian buddies should do this”(use this sound)

“Yes, thank you for making this!! Gotta represent us wasians”

Wasian seems to have been increasing in popularity in the 2020s as a term on TikTok interestingly reverting back to racial terms to describe mixed-race Asians, in the USA and across the world. This is where the algorithm of TikTok is interesting as the GPS functionality knows where you are looking at TikTok and it will send local content to your FYP that is similar to the content you have looked at, liked, or commented on. In this sense, TikTok uses the combinations of hashtags and your location to drive similar content to your FYP. It also means that the default assumption of many viewers around the world was that because Niko in located in the US that most of the comments and reuses of the sound would also be by Americans in the USA. The appeal of #wasian over terms like hapa or Eurasian is in part that it combines white + asian in English, which is less driven by local or regional context, but the term moves more easily across the world on TikTok. Being combined with a video with little to no language, it uses music, phenotypical appearance and body language (the face reveal) to communicate across many cultures, languages and nationalities via social media technology. However the term wasian itself, seems to require the ‘race work’ of proving Asianess through showing Asian parent/s or physical appearance.

4.1.3. Creation of Community

One of the main social outcomes of the #wasiancheck trend on TikTok has been the virtual formation of a wasian community via the app. While affirming publicly a wasian identity, there was also discussion of forming a community and solidifying social ties through following each other (and reciprocal following back) on the app, watching more content from ‘mutuals’ (friends on TT), and liking the content of mutuals. Mutuality is both following each other (and seeing each other’s content and often liking/hearting it) but also there seems to be a second sense of mutuality, which is something that is done or felt by both/all people within a group. In this sense, the emotional affordances of TikTok allow mutuality both in terms of social networks (increasing the density of the mixed-race Asian community across the world) but also the emotional network and depth of feeling amongst mutuals where users and content creators can meet both on the app and in some cases actual meet in person. Commentators said:

“There’s a whole community for us? I’m—I don’t feel alone anymore omg!”(ryumihere)

“sounds cool to finally be represented as our own group”

“so uh—is there a sign-up sheet cause I’m down sir”

“Oh my god the peace signs at the end were SO Asian”

“Look at all the ones with this sound—why r wasians too bootiful?”(sic)

“Ok, I’m sorry but why is every wasian perfect?”

“He looks just Asian”

“am I the only one who doesn’t look Asian?”

“Wasian=melange entre white et Asian (asiatique) de rien les amis (enzoviiic_83) mix between asian and white(my friends) (translated by author)

There were also comments in Russian, Spanish, Dutch, Turkish, Tagalog, Arabic, Indonesian, but many of the #wasiancheck videos had very similar poses using ‘TikTok’ gestures such as sticking the tongue out, squinching the nose up and shaking head or making the peace sign or ‘love heart’ sign with their fingers or putting their thumb and forefinger under their chin or both hands under their chin a common aegyo (or cuteness) motion that you often see in K-pop celebrity/idol poses.

In a study of YouTube use by LGBTQ individuals, Bond and Miller (2021) found while entertainment and social connection were the main reasons why LGBTQ individuals viewed LGBTQ content on YouTube that this could serve as an important space for “community building among LGBTQ audiences, and that social connectedness is correlated with both self-esteem and collective self-esteem…” (Bond and Miller 2021, p. 1). This could also be happening on TikTok when mixed-race Asian viewers, who don’t have a local mixed-race community, friends or family members, can join others in cyberspace to form a socially connected collective identity based on similar experiences and thoughts. This serves to legitimate mixed-race Asian or wasian identities and confirms them as ‘being seen’ (visibility) within the sphere of social digital media. However, there were other tactics, than just revealing one’s face, to make claims to authentic mixed-race Asian identity involving the revealing of family members, their phenotypical appearances, proof of cultural connection (primarily with the Asian cultural side) and connections to Asian languages.

4.2. Sound “Wasian Check” by Avaxwilkinson

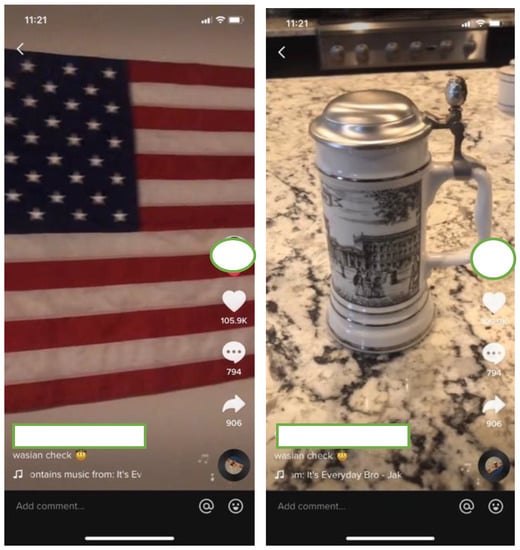

The second trend that I analyze on TikTok relating to the wasian hashtag was a sound created by avaxwilkinson which is the sound of Asian traditional, high pitched, almost nasal, singing/chanting followed by “can we switch the language?” and then a blast of the song “Sweet Caroline” (originally released in 1969, but seemingly to have never gone away, by Neil Diamond) often identified in the #wasian videos on TikTok as ‘white’ music. The videos begin often by showing the Asian parent (mothers mainly), Asian Foods, objects or places within the private home (during the Asian music) and then white dads, western objects and/or western foods/drinks during the Sweet Caroline refrain. While the trend is dominated by the American context associating whiteness with Americaness (like the American Flag, there were other countries, ethnicities and cultures associated with whiteness presented such as the German beer stein see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Objects denoting nationality.

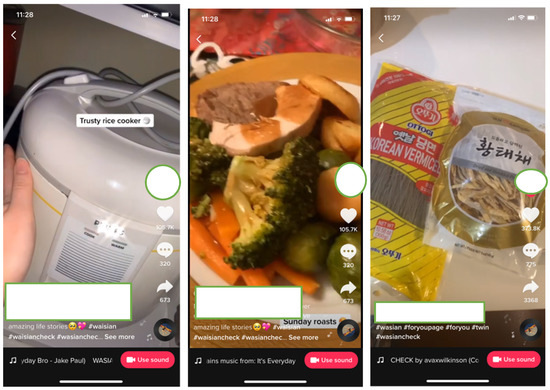

The way that wasians think of themselves and how others perceive them may not be the same. The process of defining what it means to be ‘wasian’ and how we might identify that both interpersonally but also publicly (even on social media) involves a negotiation that goes on within the gap between those notions (Törngren and Sato 2021). In the first half of the sound ‘wasian check’ during the Asian ‘traditional’ sounding music, the focus is clearly on the Asian side of the family, culture and symbols that can convey just how authentically ‘Asian’ the wasian content creator actually is. Typical shots on the video include food, people and objects such as rice cookers, Asian food packages or food (usually unprepared and in cupboards) (see Figure 6) to imply that they are a part of everyday life.

Figure 6.

Asian and white food and food related objects.

When the sound gets to the ‘can we switch the language?’ before transitioning into ‘Sweet Caroline’ the focus shifts to ‘white’ objects or white ethnic objects (again with a focus on food/drink - see Figure 6 ‘roast dinner’) so if the wasian dad is Irish objects like, Guinness or the Irish flag appear; or if the wasian ‘white’ parent is German they might represent this with a stein of beer (see Figure 5). If it is a less ‘ethnic’ whiteness being portrayed objects in the videos were shots of golf, Starbucks, Cheetos, hydro flasks or other objects associated with generic whiteness particularly in an American context. Interestingly most videos using the sound also used hashtags such as: #mexican #irish #asian #mixed #wasian but very rarely do they hashtag white or whiteness perhaps for fear of being associated with white supremacist videos that crop up from time to time on the app.

4.2.1. From Private to Public

Most of the videos were shot inside homes or bedrooms (during the pandemic especially) and thus continued to bring the everyday, formerly private space, out into the public sphere by showing kitchens, bedrooms, Asian and white parents, other mixed siblings, and food pantries, etc. in the videos.

Art and languages (particularly Asian languages) were another way to illustrate the bi-cultural and bi-racial nature of being wasian. In the first part of the sound, using or showing Asian art (see Figure 7), Asian parent, or Asian language within their private home sphere (scrolls/screens on the wall).

Figure 7.

Asian Art Objects.

One popular object to show was also books in Asian languages (see Figure 8) or speaking first in an Asian language (over the music) and then in English (or German or Swedish or French) or a ‘western associated’ language i.e., the language associated with the white parent.

Figure 8.

Asian Language Books.

Family photos were also a common way to ‘show’ or illustrate the racial mixing that made the content creator wasian. Often creators would show a photo of Asian family members (during the Asian music of the sound) and then showing photos of white family members (during sweet Caroline) and finish with a photo of themselves as clearly a mixed-race child (see Figure 9) such as wearing hanbok (traditional Korean dress), yukata/Kimono (Japanese), or Qipao/Cheongsam (Chinese dress) but clearly showing their faces (as mixed people) or showing photographs of their parents (particularly when they were younger) as a way of illustrating the genealogy of their mixedness thus making them wasian. This trend presents and interesting tension between the need to claim ‘racial genealogy’ through tracing parents’ race or racialized appearance and the desire to re-mix that as #wasian.

Figure 9.

An Example of Wearing ‘Asian’ Dress.

4.2.2. TikTok Emotional Affordances

The visual nature of TikTok means that the presence of objects, food, and people in photos or concepts that you can ‘show’ your audience rather than tell them is the currency of the app. The background sounds are key to drawing viewers’ attention to the visual content, much more so than the voice overs or textual language since most of the videos in this trend to do not use or depend upon written text. Written comments underneath the video are where textual responses are recorded (as above in trend 1) and the emotional responses tend to come by ‘liking’, giving a heart, or video responding to a video or by following the content creator.

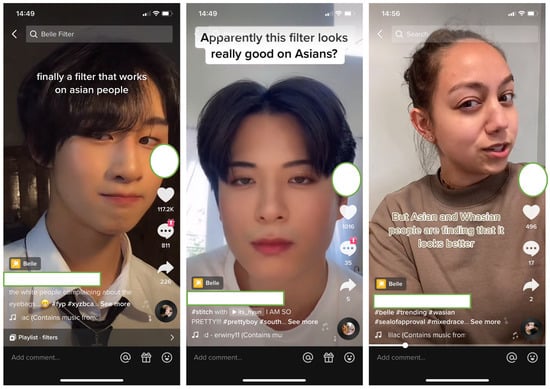

The emoticons available and used in the comments (again shaped uniquely by being as Asian designed and developed app) meant that there were more Asian type emojis available (peace sign fingers or finger heart emoticons). This shaped the types of emotional expression available to users in the comments sections but as you can see in Figure 4, users were creative about using the emojis/emoticons in creative ways to express nationality (flags) and phenotypical appearances (brown eyes) to express solidarity and social connectedness to other wasian viewers on TikTok.

A second way that emotions were shaped by the affordances of the app itself were in the use of editing features (transitions, effects and filters) in the app itself. In particular, there was discussion on TikTok on the #wasian videos of the fact that the app was Asian designed so therefore filters such as the Belle filter, made everyone who used it on their videos or photos look like a K-pop star. That the filter gave you paler skin (ideal in Asia, but not in the US perhaps), a more defined jaw line, and bigger eyes air brushing out freckles, wrinkles, chubby chins etc. to make you look more Asian and that it did not have the same, or any effect, on Caucasian faces in the same manner. Commenters wrote “it doesn’t work on you because you are white” “doesn’t work for white people”, but wasian commenters were pleased with the results because they felt that the filter was made for them (part Asians). In most video responses about the filter being better for Asians, it was again, focused on physical features with people commenting:

In particular, Wasian and Asian posters who thought that the ‘Belle’ filter was better for Asians and mixed-race Asian people, there were several comments about the addition of a small bag or puffy under eye often referred to in the comments as the addition of the ‘Aegyo Sal’ (2020) in Korea known as the “pocket of fat found directly under the eye. And in Korean this can be translated as “charming fat. Because many Koreans think that having a little pocket of fat under your eyes makes you appear younger and more cheerful” (https://seoulcosmeticsurgery.com/aegyo-sal/#:~:text=Specifically%2C%20the%20aegyo%20sal%20is,sal%20when%20they%20are%20smiling, accessed on 6 June 2022).

This reference to Asian rather than western beauty standards, made many commenters express emotions of recognition, pleasure and relief (see text in Figure 10). These brief examples, are just scratching the surface of how the app itself, structures the expression of emotion, identity and race as it shapes them and the responses to them in how they can be expressed on the app due to its technical features. Future research could explore this in more detail.

Figure 10.

Examples of responses to the ‘Belle’ filter.

4.2.3. Mimicry and Transconnective Practice the Building of the #Wasian Community across the World

Throughout these #wasian trends on TikTok, there was some consistency in how users expressed their emotions and mimicked and reused these sounds to create new videos. The reuse of sounds though made many of the posts similar or homogenous as seen above in the posting of objects, people, and food to show Asianess or whiteness ethnically or culturally. However, by doing this it also reinforced the permissible ways to prove ethnic and racial identity and background through markers like race (phenotypical appearance), food, and embodied cultural practices like wearing the hanbok etc.

The iterative nature of repeating the content over and over again, reinforces the claim to Asianess (as race) at the same time, it serves to reinforce being a part of the wasian mixed-race Asian community on TikTok. Another effect is that the emotional affordances of TikTok flatten the Wasian (white + Asian) or mixed-race experience to blood lines, food, art, culture and showable physical facial and bodily features on short videos and away from more complex notions of mixed-race identity.

In particular, by focusing on the private home, and in particular the domestic sphere, by focusing on food and kitchens, there is a gendered notion of domesticity in the video clips. The community is then built not only on reifying some notions of race and Asian ‘culture’ but also on gendered notions (where in most videos, but not all, the mother and one providing the food is Asian). Asian language was also often linked in this sound again to Asian mothers and not white fathers of the #wasian generation. In fact, one of the most popular sounds duetted that appeared after the virality of the #wasian check trend, was a video that called out ‘hey where are all the wasians with Asian dads at?’

5. Conclusions

This paper illustrates how new expressions of mixed-race identity are shifting and being created on digital social media platforms such as TikTok through an analysis of 2 trends under the #wasian category on TikTok.

First, the paper argues that transconnective cultural practices on digital social media are not just one-way transactions from fans to celebrities/influencers (parasocial), but are now much more multidirectional and include TikTok microcelebrities such as Niko Katsuyoshi the creator of the #wasian check sound and trend. The posts are liked and the sound reused across the world by a nationally and linguistically diverse wasian population and in the use and reuse of the sound they are not just entertaining but creating and building the wasian community within digital space. In addition, the more interactive nature of TikTok, as it is not limited to just textual but now video and audio ‘responses’ (by duetting videos), moves it beyond limited textual response as in YouTube or Instagram.

Secondly, one of the main reasons that this trend has grown is linked to notions of visibility and visibility labor in two senses. The use of the private, usually domestic space of the bedroom or kitchen pantry, both bring the private family and domestic, but also notions of race into public view and bring with it confirmation for many wasian users that can say ‘hey, I have a kitchen with a rice cooker too! I am not alone.’ In another sense, the facial and bodily presence, and the importance of visually appearing in the video (both of wasian users/creators and their Asian family members) is a particularly strong strategy to make visible phenotypical claims to mixedness and to affirm what one user claimed was “the power of being seen” on youth oriented digital media. But all of these videos are carefully created and curated through visibility labour (which creators try to make look effortless, but are time consuming in terms of creating, filming and editing). All of these strategies are aimed at increasing view, likes, comments, and duets/stitches (clout) and increasing warm feelings of commonality around #wasian identity across the world.

Thirdly, TikTok is a particular, Asian created, social media application with its own unique emotional affordances. I argue that the combination of the emphasis on the visual mixed-race face and body and the lack of spoken language and text, make the trend particularly easy to follow and disperse in many countries, languages and cultural contexts in part because of its format. The fact that it is also based on mimicry and mimetic means that it is easy to use the sound or create your own video as a mixed-race person. For many users who live in a space where there are not many mixed-race people, they spoke of the instant feeling of recognition and connection to the content of the videos and sound.

Finally, the social connection that the #wasian trend provides for others, virally connects mixed-race Asian users across the world and increases the density of their mixed-race social networks. In this sense, TikTok truly isn’t just entertainment, it’s community and that community can be mobilized in many ways into social and political action if needed. In the end, while many come to TikTok for entertainment purposes and end up addicted to scrolling through its videos, they stay on the app because they feel emotional satisfaction and collective belonging through video consumption and creation of trends like the #wasian check.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No IRB as paper is based on content in the public sphere.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In the public sphere–available to all on TikTok.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abidin, Crystal. 2016. Visibility Labour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and #OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia 161: 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Crystal. 2020. Mapping Internet Celebrity on TikTok: Exploring Attention Economies and Visibility Labours. Cultural Science Journal 12: 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aegyo Sal. 2020. Available online: https://seoulcosmeticsurgery.com/aegyo-sal/#:~:text=Specifically%2C%20the%20aegyo%20sal%20is,sal%20when%20they%20are%20smiling (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Ahn, Ji-Hyun. 2015. Desiring biracial whites: Cultural consumption of white mixed-race celebrities in South Korean popular media. Media Culture & Society 37: 937–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Internet Researchers. 2019. Ethical Guidelines 3.0. Available online: https://aoir.org/ethics/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Barta, Kristen, and Nazanin Andalibi. 2021. Constructing Authenticity on TikTok: Social Norms and Social Support on the “Fun” Platform. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Amy Bree. 2021. Getting out the Vote on Twitter with Mandy Patinkin: Celebrity Authenticity, TikTok, and the Couple You Actually Want at Thanksgiving Dinner… or Your Passover Seder. International Journal of Communication 15: 3580–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, Bradley J., and Brandon Miller. 2021. YouTube as My Space: The Relationships between YouTube, Social Connectedness, and (Collective) Self-Esteem among LGBTQ Individuals. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaCosta, Kimberly McClain. 2007. Making Multiracials: State, Family and Market in the Redrawing of the Colorline. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mark, and Jian Xiao. 2021. De-Westernizing Platform Studies: History and Logics of Chinese and U.S. Platforms. International Journal of Communication 15: 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fulbeck, Kip. 2006. Part Asian, 100% Hapa. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Melanie. 2020. If the rise of TikTok dance and e-girl aesthetic has taught us anything, it’s that teenage girls rule the internet right now: TikTok Celebrity, girls and the Coronavirus crisis. European Journal of Cultural Studies 23: 1069–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Keisuke. 2020. Voices of In/Visible Minority: Homogenizing Discourse of Japaneseness. In Hafu: The Mixed-Race Experience in Japan. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 50: 254–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kina, Laura, and Wei Ming Dariotis. 2013. War Baby/Love Child: Mixed Race Asian American Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- King-O’Riain, Rebecca Chiyoko. 2015. Emotional Streaming and Transconnectivity: Skype and Emotion Practices in Transnational Families in Ireland. Global Networks 15: 256–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King-O’Riain, Rebecca Chiyoko. 2021. “They were having so much fun, so genuinely…”: K-pop online affect and corroborated authenticity. New Media and Society 23: 2820–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-O’Riain, Rebecca Chiyoko, Stephen Small, Minelle Mahtani, Paul Spickard, and Miri Song. 2014. Global Mixed Race. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Rob. 2020. The Soft Power of TikTok. Commentary 150: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Lori. 2019. Uniting Hapas: The Global Communities of Mixed Race Nikkei on YouTube. In Japanese American Millennials: Rethinking Generation, Community, and Diversity. Edited by Michael Omi, Dana Y. Nakano and Jeffrey T. Yamashita. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Weishan, Dianlin Huang, and Ying Huang. 2021. More than business: The de-politicisation and re-politicisation of TikTok in the media discourses of China, America and India (2017–2020). Media International Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishime, Leilani. 2017. Stunning: Digital Portraits of Mixed Race Families from Slate to Tumblr. In The Routledge Companion to Asian American Media. Edited by Lori Kido Lopez. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nishime, Leilani. 2020. Mixed-Race Asian Americans and Contemporary Media and Culture. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-854#acrefore-9780190201098-e-854-div1-3 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Reade, Josie. 2021. Keeping it raw on the ‘gram: Authenticity, relatability and digital intimacy in fitness cultures on Instagram. New Media & Society 23: 535–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Zarine L., and Farida Fozdar. 2019. Mixed Race in Asia: Past, Present and Future. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, Zarine L., and Brenda S. A. Yeoh. 2021. Tracing Genealogies of Mixedness: Social Representations and Definitions of ‘Eurasian’ in Singapore. Genealogy 5: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Querubín, Natalia, Shuaishuai Wang, Briar Dickey, and Andrea Benedetti. Forthcoming. Political TikTok: Playful Performance, Ambivalent Critique and Event-Commentary. In Mainstreaming the Fringe: How Misinformation Propagates on Social Media. Edited by Richard Rogers. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, forthcoming.

- Saraswati, L. Ayu. 2021. Pain Generation: Social Media, Feminist Activism and the Neoliberal Selfie. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savic, Milovan. 2021. From Musically to TikTok: Social Construction of 2020’s Most Downloaded Short-Video App. International Journal of Communication 15: 3173–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schellewald, Andreas. 2021. Communicative Forms on TikTok: Perspectives from Digital Ethnography. International Journal of Communication 15: 1437–57. [Google Scholar]

- Treré, Emiliano. 2020. The banality of WhatsApp: On the everyday politics of backstage activism in Mexico and Spain. First Monday 25: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törngren, Sayaka Osanami, and Yuna Sato. 2021. Beyond being either-or: Identification of multiracial and multiethnic Japanese. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47: 802–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valverde, Caroline Kieu Linh. 1992. From Dust to Gold: The Vietnamese Amerasian Experience. In Racially Mixed People in America. Edited by Maria P. P. Root. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino-Verdu, Arantxa, and Crystal Abidin. 2022. Music Challenge Memes on TikTok: Understanding In-Group Storytelling Videos. International Journal of Communication 16: 883–908. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Wei, and Jiena Wu. 2021. Short Video Platforms and Local Community Building in China. International Journal of Communication 15: 3269–91. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Duncan Ryuken. 2017. Hapa Japan. Los Angeles: Kaya Press/Ito Center Editions, vols. 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Leon, Teresa, and Cynthia L. Nakashima. 2001. The Sum of Our Parts: Mixed-Heritage Asian Americans. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wonneberger, Anke, Iina R. Hellsten, and Sandra H. J. Jacobs. 2021. Hashtag activism and the configuration of counterpublics: Dutch animal welfare debates on Twitter, Information. Communication & Society 24: 1694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, Qing, and Fan Yang. 2021. From Parasocial to Parakin: Co-creating idols on Social Media. New Media and Society 23: 2593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Jing, Crystal Abidin, and Mike S. Schafer. 2021. Research Perspectives on TikTok and Its Legacy Apps. International Journal of Communication 15: 3161–72. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).