Abstract

This study examines the mobilization of social and cultural capital among first and second-generation Afro-Caribbeans in Canada, focusing specifically on Jamaican and Haitian populations. Employing an analytical model grounded in resistance and identity multi-positionality, this research utilizes Yosso’s theory of cultural wealth as a theoretical framework. Qualitative data were collected through focus groups and an intake survey aimed at exploring the dual objectives of defining Blackness and constructing an in-group Black identity alongside the establishment and contestation of social capital within these groups. The findings reveal a dynamic interplay between resistance and identity, highlighting how marginalized groups leverage their resilience to build robust social networks that challenge hegemonic norms. Significant generational differences were identified in experiences of racism, discrimination, and cultural preservation among the participants. This study contributes to the broader discourse on immigrant integration, social cohesion, and the role of cultural capital in mitigating systemic inequalities. The results underscore the necessity for intersectional approaches to comprehend the complexities of identity formation and social integration in multicultural societies. Moreover, the research emphasizes the critical importance of cultural heritage, identity, and community support as sources of strength and resilience for Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada.

1. Introduction

Canada is home to over one million individuals of Caribbean descent, a significant portion of whom are of Jamaican and Haitian heritage (Government of Canada, Statistics Canada 2023). Despite this substantial demographic presence, Afro-Caribbean communities often encounter unique challenges in their pursuit of social and cultural integration within Canadian society. These challenges include systemic racism, discrimination, and barriers to employment and social mobility, which complicate their efforts to integrate fully into the broader Canadian society.

Canada’s multicultural framework, while often celebrated as a model of inclusion, operates within a racialized context shaped by historical inequities and enduring structural barriers. Understanding this dual reality is essential for an international readership, as it situates the Afro-Caribbean experience within Canada’s broader political and cultural landscape. The notion of multiculturalism, when examined alongside Cedric J. Robinson’s concept of the racialized world system, reveals how systemic hierarchies persist beneath policies of tolerance and diversity. This framing provides the necessary context for interpreting the intersection of cultural capital, resistance, and identity formation analyzed in this study.

This study investigates the mobilization of social capital within Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada, focusing specifically on Jamaican and Haitian populations. A portion of this research, specifically the findings on polite racism and cultural capital, has been published as a peer-reviewed article (Coen-Sanchez 2025b). Building on my earlier theorization of polite racism (Coen-Sanchez 2025b), this study introduces an expanded model—The Affective Architecture of Polite Racism—to account for how institutional civility functions as a mechanism of racial governance and emotional regulation. This study argues that Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada mobilize social and cultural capital through resistance and identity multi-positionality, redefining Blackness and challenging the presumed neutrality of cultural capital within Canada’s racialized world system. The research introduces a novel analytical model that emphasizes social and cultural capital—concepts that refer to the non-financial social assets that promote social mobility beyond economic means, such as education, intellect, style of speech, and dress—through the lenses of resistance and identity multi-positionality. This model foregrounds how individuals and groups navigate multiple intersecting social identities to exert agency and challenge dominant power structures.

To address these objectives, the author employs Yosso’s (2005) theory of cultural wealth, which underscores the significance of intersecting identities and multi-positionalities. The study primarily investigates how holding multiple social positions simultaneously, such as immigration status and socio-economic class, shapes the experiences and social interactions of these communities in Canada. Additionally, it examines how the cultural capital of first- and second-generation Jamaicans and Haitians living in Canada affects their sense of belonging.

The primary objective of this study is to identify and critically analyze how cultural capital shapes the construction of Blackness among first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican communities in Canada, and to provide new sociological approaches to identity formation and cultural capital. The findings of this study are not only significant for the academic community but also for policymakers and social activists, as they shed light on the unique challenges and strengths of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada.

This study is guided by two central research questions: (1) How do Jamaican and Haitian communities mobilize their social and cultural capital to define Blackness and construct an in-group Black identity in Canada? (2) How are social and cultural capital manifested and contested among first- and second-generation Haitians and Jamaicans in Canada? These questions matter because they illuminate the contradictory experiences of Afro-Caribbean individuals who are navigating institutions that both celebrate diversity and reinforce racial hierarchies. Prior work has examined how these institutional frameworks—particularly immigration, education, and multicultural policy—impact Afro-Caribbean identity formation and belonging in Canada (Coen-Sanchez 2025a). By extending Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital through Yosso’s model of community cultural wealth—and grounding these frameworks in Cedric J. Robinson’s theory of racial capitalism—this research challenges the presumed neutrality of cultural capital and centers the lived realities of racialized communities (Bourdieu 1986). In doing so, it introduces original theoretical concepts such as polite racism, racial ignominy, and duplicity of consciousness, while contributing to a critical gap in Canadian sociological literature.

While there is substantial research on the integration of immigrant communities in Canada, much of the existing literature tends to focus broadly on economic integration and often overlooks the nuanced experiences of specific ethnic groups, particularly those of Afro-Caribbean descent. Previous studies have examined social and cultural capital primarily within homogeneous groups or across broad categories such as ‘immigrants’ or ‘racial minorities,’ failing to account for the distinct experiences of different communities. Additionally, the intersectionality of social identities and its impact on the mobilization of social and cultural capital among Afro-Caribbean communities remain underexplored. This study addresses this gap by focusing specifically on the Jamaican and Haitian communities, offering an in-depth analysis of how these groups navigate their intersecting identities within a racialized Canadian context.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this section, we delve into the key theories that underpin this study, providing detailed explanations and exploring their specific relevance to the Afro-Caribbean context. The primary theoretical concepts employed are Yosso’s theory of cultural wealth, social positionality, intersectionality, and racial consciousness. Each concept is intricately connected, creating a cohesive framework for understanding the social and cultural capital of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada.

While the theoretical foundations of cultural capital and intersectionality have been extensively explored, empirical research focusing specifically on Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada remains comparatively limited. Recent studies such as Gooden and Hackett’s (2020) analysis of Black Canadian women’s experiences in education and the workforce, and James’s (2012) work on systemic anti-Black racism in Ontario’s schools, offer valuable insights into structural barriers faced by Black Canadians. However, few empirical studies to date have provided a sustained examination of how Haitians and Jamaicans in Canada mobilize cultural and social capital to define identity, assert agency, and resist systemic exclusion—particularly from a generational lens. In contrast, U.S.-based scholarship by Rolón-Dow (2011) and U.K.-based studies such as Wallace (2017) have engaged more deeply with the cultural strategies of Black Caribbean youth navigating white-dominant institutional spaces. Drawing on this transnational literature, the current study contributes to a growing body of scholarship on diasporic Black identity by situating the Canadian case within global patterns of racialization, while highlighting distinct features such as Canada’s model of multiculturalism and the operation of polite racism (Coen-Sanchez 2025b). This research builds on prior work that introduced polite racism as a form of institutional racial exclusion masked by civility, tolerance, and multicultural discourse (Coen-Sanchez 2025b). Unlike overt racism or microaggressions, polite racism operates through seemingly inclusive policies and interpersonal politeness while reinforcing structural inequities. For a comprehensive conceptual development, see (Coen-Sanchez 2025b). This research thus bridges a critical empirical gap while expanding conceptual frameworks relevant to racialized communities in both Canadian and international contexts.

Yosso’s (2005) theory of cultural wealth challenges traditional deficit models that portray minority communities as lacking valuable social and cultural resources. Instead, it posits that marginalized communities possess unique forms of capital that contribute to their resilience and success. Yosso identifies six forms of cultural capital:

“Aspirational capital refers to the ability to maintain hopes and dreams for the future, even in the face of real and perceived barriers”.(p. 77)

“Linguistic capital includes the intellectual and social skills attained through communication experiences in more than one language and/or style”.(p. 78)

“Familial capital refers to those cultural knowledges nurtured among familia (kin) that carry a sense of community history, memory and cultural intuition”.(p. 79)

“Social capital can be understood as networks of people and community resources”.(p. 79)

“Navigational capital refers to skills of maneuvering through social institutions”.(p. 80)

“Resistant capital refers to those knowledges and skills fostered through oppositional behavior that challenges inequality”.(p. 80)

In the context of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada, these forms of capital are pivotal. For instance, aspirational capital is evident in the determination of both first and second-generation Jamaicans and Haitians to achieve academic and professional success despite systemic barriers. Linguistic capital is reflected in the bilingual or multilingual abilities of these communities, which enhance their adaptability and communication skills in diverse settings. Familial capital is crucial in maintaining cultural traditions and a strong sense of identity, which fortify the community’s social fabric.

Social capital is particularly significant in forming networks that provide support and resources essential for navigating Canadian society. Navigational capital is evident in the ability of Afro-Caribbean individuals to maneuver through various social systems, including education and employment, often utilizing community-based knowledge and strategies. Resistant capital is highlighted in the collective efforts to resist and challenge systemic racism and discrimination, fostering a sense of empowerment and agency.

Social Positionality The theory of social positionality, rooted in intersectionality, emphasizes the dynamic interplay between an individual’s social identity and their position within larger social structures (Collins 2000; Crenshaw 1989). This framework is essential for understanding how Afro-Caribbean individuals navigate their multiple intersecting identities, such as race, gender, and class, within a racialized Canadian context. Social positionality posits that an individual’s experiences and opportunities are shaped by their unique positioning at the intersections of various social categories. For Afro-Caribbeans in Canada, this means their experiences of belonging, discrimination, and identity construction are influenced not only by their racial identity but also by their immigrant status, socioeconomic background, and cultural heritage. This synthesis of identities reflects the study’s focus on multi-positionality—illustrating how individuals navigate multiple social locations simultaneously.

Intersectionality, a term coined by Crenshaw (1991), provides an analytical framework for understanding how various forms of social stratification, such as race, gender, and class, interact to create unique dynamics and effects. This perspective is critical for examining the experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities as it acknowledges that their social identities are not experienced in isolation but in a complex, intersecting manner. These overlapping experiences exemplify multi-positional identity work, where the interplay between race, gender, and immigrant status produces layered forms of inclusion and exclusion. By applying intersectionality, this study explores how the overlapping identities of first and second-generation Jamaicans and Haitians influence their social interactions and access to resources. For example, the intersection of race and immigrant status can result in compounded forms of discrimination that are distinct from those experienced by non-immigrant Black Canadians or immigrants from other ethnic backgrounds. Such compounded experiences demonstrate how multi-positionality functions as a lived negotiation of structure and identity within the Canadian racialized world system.

Racial Consciousness: Racial consciousness theory, grounded in critical race theory, focuses on developing awareness regarding racial identity and its broader socio-political implications. This framework emphasizes that racial identity is socially constructed and shaped by historical, cultural, and institutional contexts (Crenshaw 1989; Hill et al. 2016). In the context of this study, racial consciousness is crucial for understanding how Afro-Caribbean individuals perceive and navigate their racial identities within a predominantly white Canadian society. This heightened awareness of racial dynamics and systemic inequalities influences their strategies for building social and cultural capital, as well as their efforts to resist and challenge marginalization.

These concepts build upon an intellectual lineage that includes W.E.B. Du Bois’s notion of double consciousness and Frantz Fanon’s analysis of racial alienation (Fanon 1967). The term “duplicity of consciousness” refines Du Boisian double consciousness to capture the psychic bifurcation produced specifically through institutional civility. Similarly, “racial ignominy” resonates with Fanon’s reflections on racialized shame. The concept of Transferable Racial Confluence extends from affect theory (Ahmed 2004) and the scholarship on emotional labor (Hochschild 2012, highlighting how affective residues of exclusion can generate forms of counter-capital in diasporic communities.

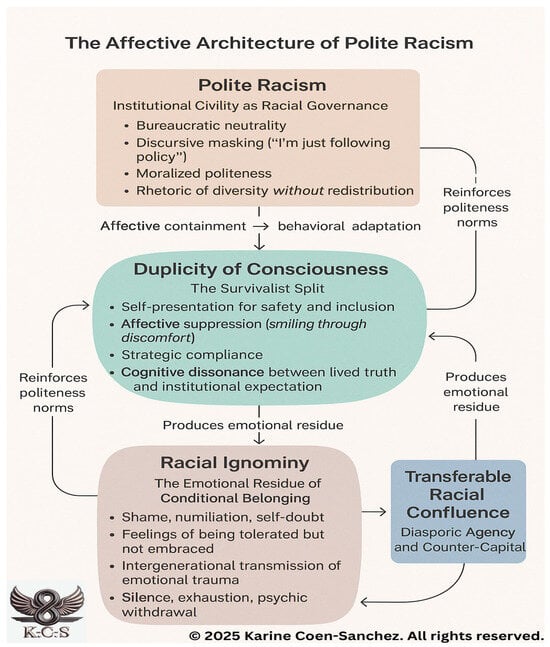

To provide a clear map of the theoretical relationships developed in this study, I introduce Figure 1 below. It outlines how institutional civility, duplicity of consciousness, and emotional containment produce racial ignominy, which can, in turn, be transmuted into Transferable Racial Confluence. This recursive loop constitutes what I theorize as the Affective Architecture of Polite Racism—a model grounded in, but also extending, affect theory and racial capitalism.

Figure 1.

The Affective Architecture of Polite Racism.

In advancing the conceptual terrain of this study, I introduce the framework of The Affective Architecture of Polite Racism (Figure 1). This model expands on the concept of polite racism, previously theorized in my 2025 work, by tracing how institutional civility functions not simply as social decorum, but as a form of racial governance that elicits affective and behavioral responses from racialized subjects. The diagram maps out the recursive relationship between institutional neutrality, emotional containment, and the production of racial ignominy—a psychic residue that both limits and generates diasporic agency. This affective circuitry not only sustains politeness norms but also cultivates what I term Transferable Racial Confluence, wherein the emotional labor of marginalization becomes a source of diasporic counter-capital. The framework deepens our understanding of how civility can mask structural violence, while also showing how emotional residues are not simply debilitating but potentially catalytic.

This framework visualizes the recursive emotional, institutional, and behavioral feedback loops that define polite racism as a form of affective governance. It outlines how institutional civility and discursive masking produce internalized behavioral adaptations and emotional dissonance, resulting in racial ignominy. The model also highlights how this affective residue can be transformed into Transferable Racial Confluence—a site of diasporic resistance and counter-capital. © 2025 Author. Used with permission by the author.

The affective consequences of polite racism, as explored in this study, reveal how institutionalized civility operates as a form of racial governance that produces emotional residue in Afro-Caribbean communities. Figure 1 illustrates this process by mapping the affective architecture of polite racism, highlighting how duplicity of consciousness and emotional containment arise from everyday encounters with systemic exclusion. This recursive interplay not only shapes identity but also informs the strategies of resistance and capital formation explored in the research that follows.

The theoretical frameworks of Yosso’s cultural wealth, social positionality, intersectionality, and racial consciousness are not merely abstract concepts but are directly applicable to this study’s innovative research objectives and methodology. By employing these theories, the research seeks to uncover how first and second-generation Jamaicans and Haitians in Canada leverage their multifaceted identities to resist marginalization and build resilient networks.

Yosso’s theory of cultural wealth provides a comprehensive lens for identifying and valuing the diverse forms of capital that Afro-Caribbean communities possess. Social positionality and intersectionality offer critical insights into how these communities navigate their complex identities within a racialized society. Racial consciousness further contextualizes these experiences within broader socio-political dynamics, highlighting the importance of collective awareness and action.

Through focus groups and qualitative analysis, this study examines how intersecting identities, historical contexts, and cultural practices shape the experiences of Afro-Caribbeans in Canada. The navigation of identity through institutional structures is also shaped by immigration and multicultural policies, which simultaneously offer inclusion and reinforce systemic boundaries (Coen-Sanchez 2025a). This theoretical grounding ensures that the research captures the complexities of identity formation and the dynamic interplay of social forces that influence the lived experiences of these communities.

By seamlessly integrating these theoretical perspectives, the study not only advances academic understanding but also provides practical insights for policymakers and social activists working to foster more inclusive and equitable societies. This comprehensive and interconnected theoretical framework establishes a robust foundation for analyzing the unique experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada and contributes to the broader discourse on social integration and cultural capital.

3. Methodology—Analytical Framing

Through qualitative analysis, the author redefines cultural capital to include the skills, knowledge, and practices that arise from navigating multiple social identities and resisting marginalization. The study, through an intersectional framework, also illustrates how Blackness is constructed and contested within intersecting regimes of power that challenge established norms and exert significant influence over the collective. Furthermore, the author discusses the concept of racial convergence as a process through which different ethnic groups achieve greater equality and integration within society, moving towards diminishing racial disparities and fostering inclusivity and equity. This discussion not only provides a comprehensive understanding of the current social landscape but also offers a hopeful vision for a more inclusive and equitable future.

To clarify the methodological orientation, this study employs a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz 2014; Corbin and Strauss 2015), which emphasizes the co-construction of meaning between researcher and participants while acknowledging the interpretive nature of qualitative inquiry.

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a qualitative research approach to explore the social and cultural capital dynamics within Canada’s Jamaican and Haitian diaspora. The primary data collection methods include focus groups and intake surveys. This multi-method approach allows for an in-depth understanding of the lived experiences and perceptions of first- and second-generation Afro-Caribbeans.

Grounded theory was selected for its ability to generate themes directly from participant narratives rather than imposing a pre-existing model. The analysis followed three stages—open coding, axial coding, and selective coding—to develop core categories such as resistance, identity negotiation, and intergenerational cultural transmission.

3.2. Data Collection

With a steadfast commitment to inclusivity, this study employed a rigorous grounded theory methodology, aiming to generate themes grounded in the data rather than derived from pre-existing models (Brady and Loonam 2010). A total of twelve focus groups were conducted—six with Haitian participants and six with Jamaican participants—each comprising 3 to 5 individuals, resulting in a total sample of 48 participants. Participants were recruited using snowball sampling, a method that facilitated community trust and engagement, but may have introduced selection bias by favoring those with stronger social connections.

All participants were based in the Ottawa-Gatineau region, offering insight into Afro-Caribbean experiences within bilingual and urban Canadian settings. Eligible individuals self-identified as either Haitian or Jamaican, were first- or second-generation immigrants, and were between the ages of 25 and 45. The sample reflected a range of genders, education levels, and socioeconomic backgrounds, including students, professionals, and working-class individuals. These same focus groups and intake surveys formed the empirical basis for a previously published article on polite racism and cultural capital (Coen-Sanchez 2025b).

In addition to participating in focus group discussions, all participants completed a brief intake survey designed to gather demographic information and gauge the relevance of various forms of cultural capital (e.g., language use, social mobility, intercultural skills). These Likert-scale responses were used to support methodological triangulation, inform coding categories, and generate visual summaries later in the analysis.

To support triangulation and contextualize participant narratives, all participants completed a brief intake survey prior to the focus group. A sample of the instrument, including demographic, experiential, and cultural capital questions, is included in Supplementary Materials.

4. Focus Group Procedures

Participants were provided with informed consent forms and were assured of confidentiality. With their permission, the focus group sessions were audio-recorded for transcription. The discussions were designed to elicit detailed insights on topics such as:

- The advantages and disadvantages of identifying as Haitian or Jamaican in Canada.

- Experiences of racism and discrimination.

- The role of cultural heritage in their lives.

- The use of social and cultural capital in navigating Canadian systems.

Specific questions included: “How does identifying with your cultural heritage help you navigate Canadian systems?” and “What role does cultural or social capital play in your daily life?”

While the discussions were conducted primarily in English, participants also used French, Haitian Creole, and Jamaican Patois. These multilingual expressions carried important cultural meaning and were retained in transcripts where relevant. However, linguistic comfort and code-switching may have influenced who expressed themselves most freely.

The researcher is fluent in English, French, and Haitian Creole, and has working comprehension of Jamaican Patois. This linguistic capacity facilitated accurate transcription, culturally grounded interpretation, and the preservation of participant voice.

5. Data Analysis

The data analysis process followed grounded theory principles (Charmaz 2014; Corbin and Strauss 2015), involving open coding, memoing, and theoretical sampling. Transcripts were analyzed line-by-line to identify meaningful units of data, which were initially labeled during the open coding stage with descriptive terms such as accent-based exclusion, cultural retention, or credential mismatch. These preliminary codes were then refined and clustered into higher-order themes during the axial coding phase, which focused on identifying relationships between categories—such as the interplay between institutional gatekeeping and polite racism, or between parental expectations and identity adaptation. In the selective coding phase, central categories like duplicity of consciousness, racial ignominy, and in-group identity formation were integrated into a coherent theoretical framework.

Thematic categories were compared across generational (first- vs. second-generation) and ethnonational (Jamaican vs. Haitian) lines to identify both commonalities and points of divergence in how participants mobilized cultural and social capital. Analysis continued until theoretical saturation was achieved—that is, when new data no longer yielded novel insights or altered the developing themes (Fusch and Ness 2015). Throughout the process, memoing served as a tool for reflexivity and theoretical development, helping to track interpretive decisions and emergent conceptual relationships. A sample coding matrix and brief codebook are included in Supplementary Materials.

5.1. Methodological Rigor

To enhance the trustworthiness of the study’s interpretations, several validation strategies were implemented. Methodological triangulation was employed by integrating data from both focus groups and the intake survey. Peer debriefing sessions were conducted with other researchers to discuss the coding process and emerging themes, bolstering the validity of the analysis. Member checking was also utilized, wherein preliminary findings were shared with a subset of participants to confirm the accuracy and resonance of the interpretations. While a single researcher conducted all coding, these validation strategies helped ensure interpretive consistency and analytical depth.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

This study acknowledges several limitations. The use of snowball sampling may have introduced selection bias by favoring more socially connected individuals. As a result, the findings may not fully reflect the experiences of more isolated community members. All participants were recruited from the Ottawa-Gatineau region, and their insights may not be generalizable to Afro-Caribbean communities in other Canadian provinces.

Group dynamics—such as age, gender, or education level—may have influenced participation during focus group discussions. Despite efforts to promote equitable dialog, some voices may have been more prominent than others. In addition, although English was the primary language of facilitation, several participants used French, Haitian Creole, and Jamaican Patois to express culturally specific ideas. While these were preserved in transcripts, linguistic comfort and fluency may have influenced how freely participants shared their experiences.

In this regard, the use of focus groups and self-reported data may have introduced response biases, including social desirability effects or limitations related to participant recall. Some participants may have framed their experiences in ways they perceived as socially acceptable within group settings or emphasized particular narratives in retrospect. While this study explicitly adopts an intersectional framework, there remains scope for a more systematic and disaggregated analysis of how intersecting identities—such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status—shape the mobilization of social and cultural capital among Afro-Caribbean communities. These dimensions emerged implicitly in participant narratives but were not the primary axes of comparison in the present analysis, pointing to important directions for future research.Additionally, gender emerged as a significant axis of difference, particularly among second-generation women, whose narratives often reflected the compounded effects of racial and gendered expectations. While this study did not undertake a systematic gender-based comparative analysis, these patterns suggest meaningful differences in how cultural capital is mobilized. Future research should explore how Afro-Caribbean women and men navigate distinct cultural expectations and institutional challenges under intersecting pressures of race, class, and gender.

Lastly, the analysis was conducted by a single researcher, which may have introduced interpretive bias. However, this limitation was mitigated through member checking, peer debriefing, and reflective memoing.

6. Detailed Thematic Analysis

6.1. Community and Cultural Identity

The thematic analysis revealed a nuanced interplay of positive and negative aspects of community and cultural identity among Haitian and Jamaican participants. A strong sense of community emerged as a significant advantage, with participants frequently highlighting their communities’ support, cultural continuity, and sense of belonging. This sense of community was described as a source of pride and resilience. One participant remarked, “The sense of community within the Haitian and Jamaican groups in Canada is very strong’ (FGD 2, February 2023, second-gen Haitian woman).” Another shared, “‘Having a close-knit community helps me feel connected to my roots’ (FGD 3, March 2023, first-gen Jamaican male).” These findings align with prior research indicating that immigrant communities often rely on close-knit networks to navigate new environments and maintain cultural continuity (Portes and Rumbaut 2001).

A strong sense of cultural identity was also highlighted as a positive aspect. Participants expressed pride in their cultural heritage, which offered a unique sense of self and belonging maintained through cultural practices, language, and traditions. For example, one respondent stated, “Being able to identify with my cultural heritage gives me a sense of pride and belonging’ (FGD 5, April 2023, second-gen Jamaican female),” and another added, “My cultural identity is a source of strength and resilience’ (FGD 5, April 2023, second-gen Haitian male).” This aligns with studies suggesting that cultural identity serves as a source of strength and resilience for immigrant communities (Phinney et al. 2001). Valuing cultural heritage and traditions is seen as essential for personal and community well-being, encompassing festivals, cuisine, music, and other cultural expressions. Participants underscored the importance of cultural practices, with one stating, “‘Our cultural traditions and practices are important to me and my family’ (FGD 1, January 2023, first-gen Haitian woman),” and another emphasizing, “Celebrating our cultural festivals keeps our heritage alive’ (FGD 6, May 2023, second-gen Jamaican male).”

6.2. Racism and Discrimination

Despite these positive aspects, participants reported significant challenges, particularly experiences of racism and discrimination in various life aspects, notably in the workplace. These experiences contributed to a sense of marginalization and inequality. One participant mentioned, “I’ve faced discrimination in the workplace because of my background” (FGD 4, February 2023, first-gen Haitian male),” while another shared, ““Racism is a persistent issue that affects many aspects of my life” (FGD 4, February 2023, second-gen Jamaican female).” Research has shown that racism and discrimination can have detrimental effects on mental health and socioeconomic outcomes for immigrants (Vang et al. 2019). Participants’ experiences of discrimination, especially in employment, highlight the systemic barriers hindering their professional growth and integration into Canadian society. These narratives are consistent with the concept of polite racism developed in earlier work (Coen-Sanchez 2025b), which frames racism in Canada as often indirect and veiled behind formal multiculturalism. Participants encountered exclusion not only through overt discrimination but also through gatekeeping practices, institutional tone policing, and cultural devaluation—hallmarks of polite racism. These experiences underscore how civility and tolerance can paradoxically be weaponized to sustain racial hierarchies while silencing critique. This is corroborated by studies documenting the difficulties immigrants face in the labor market, often attributed to bias and lack of recognition of foreign qualifications (Reitz 2007).

These acts of subtle exclusion, though often framed as misunderstandings or personality clashes, produced a lingering psychological effect. As one participant explained, “Sometimes I have to smile and shrink just to make people comfortable—it’s like being two people at work and at home.” This performance of emotional labor under the guise of professionalism underscores what I theorize as duplicity of consciousness—a psychic fragmentation rooted in institutional expectations of civility. Similarly, another participant described a “need to smile through being ignored” (FGD 4, February 2023, second-gen Jamaican female), reflecting how performative politeness operates as both a coping strategy and a site of internalized exclusion.

6.3. Employment and Support

Challenges in finding employment due to cultural background were also noted. Participants observed that their cultural background was sometimes undervalued, leading to fewer job opportunities and limited professional growth. For example, one respondent pointed out, “‘It can be challenging to find employment that values my cultural background’ (FGD 3, March 2023, second-gen Haitian female),” and another expressed, “‘I feel that my qualifications are often overlooked because of my ethnicity’ (FGD 6, May 2023, first-gen Jamaican female).” The need for better support systems was a recurring theme, with participants emphasizing the necessity for improved educational, professional, and social support to help individuals from Haitian and Jamaican communities navigate and succeed in Canadian society. This sentiment was echoed by statements such as, “‘There needs to be more support for Haitian and Jamaican communities in Canada’ (FGD 5, April 2023, second-gen Haitian male),” and “‘Access to resources and support is crucial for our community’s success’ (FGD 2, February 2023, first-gen Jamaican male).” This issue is well-documented, with evidence showing that immigrants often encounter employment discrimination and underemployment (Oreopoulos 2011). Enhanced support mechanisms are crucial for improving the social and economic integration of immigrants, as suggested by policy recommendations in existing literature (Li 2003).

These findings underscore the complex interplay between cultural capital factors and the lived experiences of first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican communities in Canada. Despite facing significant challenges, these communities continue to place high value on cultural heritage, identity, and supportive community networks. The thematic analysis highlights both positive and negative aspects of identifying as Haitian or Jamaican in Canada, emphasizing the need for better support systems to improve the social and economic integration of these communities.

6.4. Social and Cultural Capital

Resistance serves as a driving force that fosters alliances and shapes cultural practices. Identity multi-positionality, referring to the intersection of multiple social identities such as race and class, enhances and enriches both social and cultural capital. Social capital is formed through networks and connections, particularly those strengthened by resistance and the diverse identities within these networks. Cultural capital encompasses the skills, knowledge, and cultural practices that emerge and are enriched through resistance and the intersection of multiple identities.

Table 1 synthesizes these dynamics by illustrating generational and community-level differences in the mobilization of cultural capital and the construction of Blackness among Haitian and Jamaican participants.

Table 1.

Generational differences in cultural capital and constructions of Blackness among Haitian and Jamaican participants in Canada. The table summarizes how first- and second-generation participants from Haitian and Jamaican communities mobilize cultural capital and articulate Blackness in relation to national identity, cultural preservation, and experiences of racialization.

The relationships among these concepts include:

Resistance forming alliances that enhance social networks (social capital) and shape cultural practices (cultural capital);

Identity multi-positionality driving and sustaining resistance movements;

The intersection of multiple identities broadening and deepening social networks (social capital);

Diverse identities enriching cultural expressions and practices (cultural capital).

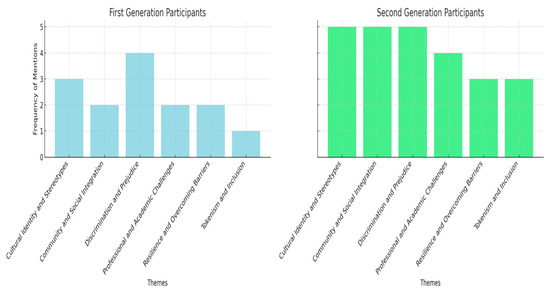

6.4.1. Comparison of Generational Differences

A comparison of the experiences between first- and second-generation participants revealed nuanced differences. First-generation participants focused more on the direct impact of discrimination and the challenges of preserving their cultural identity in a new environment. In contrast, second-generation participants emphasized the ongoing struggle with stereotypes and the importance of community while navigating Canadian society. Despite these differences, both groups highly valued cultural heritage, identity, and supportive community networks.

6.4.2. Illustrative Quotes

Community: “The sense of community within the Haitian and Jamaican groups in Canada is very strong.”

Identity: “Being able to identify with my cultural heritage gives me a sense of pride and belonging (FGD 5, April 2023, second-gen Jamaican female).”

Support: “There needs to be more support for Haitian and Jamaican communities in Canada (FGD 5, April 2023, second-gen Haitian male).”

Culture: “Our cultural traditions and practices are important to me and my family (FGD 1, January 2023, first-gen Haitian woman).”

Racism and Discrimination: “I’ve faced discrimination in the workplace because of my background, (FGD 4, February 2023, first-gen Haitian male).”

Employment: “It can be challenging to find employment that values my cultural background (FGD 3, March 2023, second-gen Haitian female).”

These findings highlight the duality of the immigrant experience, where strong community ties and cultural pride coexist with challenges such as discrimination and the need for enhanced support systems. This analysis underscores the importance of recognizing and addressing these challenges to foster better integration and well-being for Haitian and Jamaican communities in Canada.

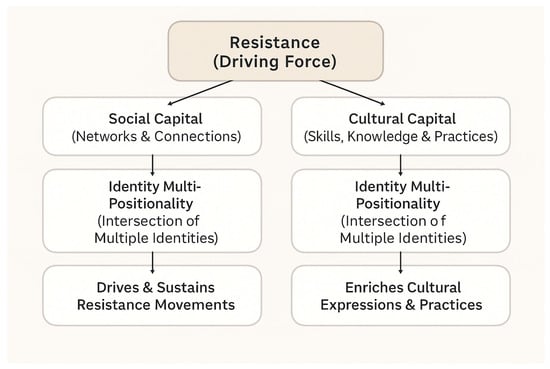

Building upon Yosso’s (2005) theory of community cultural wealth and informed by Black diasporic and intersectional thought, I propose a conceptual framework that centers identity multi-positionality as a generative site of resistance. As shown in Figure 2, this model theorizes how Afro-Caribbean individuals—particularly across generational lines—deploy resistance as an intentional and strategic force that drives the formation of both social and cultural capital. By foregrounding resistance as not only reactive but productive, this framework captures the interlocking emotional, social, and political mechanisms through which diasporic communities transform marginalization into empowerment. This figure represents an original contribution and forms the backbone of my theoretical intervention into how racialized identity operates within settler institutions.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model of Resistance as a Driving Force in the Formation of Social and Cultural Capital through Identity Multi-Positionality.

Resistance is a central element that likely interacts with social capital and cultural capital. Social capital refers to the networks, connections, and social interactions that individuals or groups can leverage for various benefits. Cultural capital encompasses the knowledge, skills, education, and other cultural assets that individuals possess. The diagram suggests that resistance can be a response to or a product of social and cultural capital. For example, individuals might use their social networks and cultural knowledge to resist societal norms or to assert their identities.

Identity multi-positionality, another key concept in the diagram, reflects the idea that individuals hold multiple identities simultaneously, which can intersect and interact in complex ways. This concept is shown to be influenced by both social and cultural capital, as well as by acts of resistance. The arrows in the diagram likely show how a strong sense of identity multi-positionality can enhance one’s social and cultural capital, creating a feedback loop where these elements continually interact and evolve. This interconnectedness highlights the fluid nature of identity and the powerful role of resistance in shaping social and cultural dynamics.

These findings underscore the complex interplay between cultural capital factors and the lived experiences of first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican communities in Canada.

The bar chart below illustrates the average relevance scores for various cultural capital factors between first and second-generation participants. Each factor is rated on a scale from 1 (Not relevant) to 4 (Very relevant).

Key findings reveal that both first and second-generation participants find spoken languages quite relevant, with second-generation participants rating it slightly higher. Intercultural skills, particularly in conflict resolution, are deemed highly relevant by both groups, showing similar ratings. Social mobility, another crucial factor, is rated similarly by both groups, with a slight inclination towards higher relevance among first-generation participants. Social relationships also receive high relevance scores from both groups, with first-generation participants giving marginally higher ratings. When it comes to cultural financial knowledge, both groups rate it similarly, though first-generation participants find it slightly more relevant. Finally, cultural skills, encompassing beliefs, customs, and traditions, are highly relevant to both groups, with second-generation participants rating them slightly higher.

As shown in Figure 3, second-generation participants attribute higher value to linguistic and cultural knowledge than their first-generation counterparts, suggesting a shift in how cultural capital is operationalized. This generational variation points to a redefinition of which forms of knowledge are considered empowering, reflecting the adaptive strategies of younger Afro-Caribbean Canadians as they navigate contemporary Canadian institutions.

Figure 3.

Comparative Illustration of Cultural Capital among First- and Second-Generation Afro-Caribbean Communities in Canada. This figure compares the perceived relevance of distinct forms of cultural capital between first- and second-generation Afro-Caribbean participants.

Another factor in the research explores the construction of Blackness and cultural capital among first-generation and second-generation Haitians and Jamaicans in Canada. The chart highlights several key themes related to cultural identity and the construction of blackness among first-generation and second-generation Haitians and Jamaicans in Canada. Both first-generation Haitians and Jamaicans place a strong emphasis on preserving their respective cultural heritages, with Haitians focusing on cultural practices and history, and Jamaicans on music and cuisine. Second-generation individuals from both communities develop hybrid identities, blending their parents’ cultural backgrounds with Canadian norms, and navigating the challenges of balancing dual identities. Blackness is constructed differently across these groups; for first-generation Jamaicans, it is closely linked to national identity and the celebration of cultural icons and traditions, while for Haitians, it is tied to preserving a unique cultural heritage and resisting assimilation. Second-generation Haitians and Jamaicans face the additional complexity of integrating their cultural elements with Canadian culture, dealing with racism, and forging a fusion of influences in a multicultural society.

Overall, there are minor differences in how first and second-generation participants perceive the relevance of various cultural capital factors. Nonetheless, the general trends indicate that both groups consider these factors important for navigating Canadian systems.

While the study distinguishes between Haitian and Jamaican experiences where appropriate, the analytic decision to combine data reflects the shared processes of racialization and collective resistance experienced across Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada. Several participants described a growing sense of pan-Caribbean belonging, expressed through cultural collaboration, intercommunity networks, and mutual recognition within the broader Black diaspora. This emergent identity points to a fluid re-articulation of cultural capital and belonging that aligns with theories of transnational identity formation. Collectively, these findings suggest that beyond national distinctions, Haitian and Jamaican participants increasingly situate their sense of self within a wider Afro-Caribbean framework shaped by shared histories of migration, resilience, and adaptation. These insights set the stage for the subsequent discussion on how intersecting forms of social and cultural capital operate across Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada.

7. Discussion

Intersectionality of Social and Cultural Capital This study addresses a notable gap in the literature by examining the intersectionality of social and cultural capital and its nuanced effects on the acquisition and utilization of these forms of capital among Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada. While prior research has predominantly explored the individual impacts of social and cultural capital, there has been limited systematic investigation into how multiple social categories—such as race, gender, class, and ethnicity—intersect to shape individuals’ access to and use of these resources. Understanding these intersections is critical for developing a comprehensive and inclusive understanding of social and cultural capital, particularly for marginalized and underrepresented groups who navigate complex intersecting identities.

Existing studies have largely focused on Western contexts, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of how social and cultural capital operate in diverse cultural settings. Furthermore, these findings extend the discussion of intergenerational identity formation and belonging beyond the Afro-Caribbean context, aligning with global diasporic scholarship. In particular, this study contributes to the growing transnational conversation on second-generation identity and cultural capital explored by Chattoraj and Basu (2025), who examine parallel negotiations of belonging and resistance within South Asian diasporic communities. Cultural contexts profoundly influence the ways in which individuals accumulate and deploy social and cultural capital. For Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada, cultural heritage plays a crucial role in maintaining a strong sense of identity and community cohesion. For example, cultural practices, traditions, and linguistic skills contribute significantly to the community’s social fabric and resilience. Thus, it is imperative to explore these dynamics in various cultural, social, and economic contexts to provide a globally informed perspective. By addressing this gap, we can enhance our comprehension of the universality or context-specific nature of social and cultural capital, shedding light on how these concepts manifest and function across different cultural landscapes.

Implications for Policy: The insights gained from this study have significant policy implications that can inform the development of more inclusive and practical strategies to support Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada.

- Cultural Preservation: Recognizing the transformative potential of celebrating Afro-Caribbean cultural practices is essential. Policies should be designed to preserve and promote these practices through funding for cultural festivals, support for community organizations, and educational programs that include Afro-Caribbean histories and contributions. This approach not only enriches the cultural landscape of Canada but also fosters a sense of belonging and pride within Afro-Caribbean communities.

- Employment Equity: The study urgently highlights the need for targeted interventions to address systemic racism and discrimination, particularly in employment. Policies should focus on creating equitable hiring practices, recognizing foreign qualifications, and providing career support services tailored to the needs of Afro-Caribbean immigrants. Such measures can help reduce employment barriers and promote professional growth and integration into Canadian society.

- Community Support: The findings underscore the crucial role of social networks and community support. Policymakers should consider funding initiatives that strengthen community ties, such as mentorship programs, community centers, and peer support groups that can help individuals navigate Canadian society. These support systems are vital for enhancing the social and economic integration of Afro-Caribbean communities.

By implementing these policy measures, we can work towards a more inclusive and equitable society that recognizes and values the contributions of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada.

8. Summary of Findings

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the mobilization of social and cultural capital among first and second-generation Afro-Caribbeans in Canada, focusing on the Jamaican and Haitian communities. The findings reveal a dynamic interplay between resistance and identity multi-positionality, highlighting how marginalized groups leverage their resilience to build robust social networks that challenge hegemonic norms. Significant generational differences were identified, with first-generation participants emphasizing cultural preservation and second-generation participants focusing on community integration and navigating stereotypes. Both groups highly value cultural heritage, identity, and supportive community networks, which are essential in navigating Canadian society and overcoming systemic barriers.

9. Contributions to Literature

The research contributes to broader discussions on immigrant integration, social cohesion, and the role of cultural capital in addressing systemic inequalities. It highlights the importance of considering multiple intersecting identities in understanding the experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities. By employing Yosso’s theory of cultural wealth and an analytical model emphasizing resistance and identity multi-positionality, the study provides a nuanced understanding of how these communities navigate and contest their social capital. This research fills a critical gap in the literature by offering an in-depth analysis of the unique experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities, which are often overlooked in existing studies on immigrant integration.

10. Policy Implications

Firstly, the study underscores the transformative potential of celebrating Afro-Caribbean cultural practices. Recognizing the critical role of cultural heritage and identity in the lives of Afro-Caribbean individuals suggests that policies should be designed to preserve and promote these practices. This can be achieved through funding for cultural festivals, support for community organizations, and educational programs that include Afro-Caribbean histories and contributions.

Secondly, the study urgently highlights the need for targeted interventions to address systemic racism and discrimination, particularly in employment. Policies should focus on creating equitable hiring practices, recognizing foreign qualifications, and providing career support services tailored to the needs of Afro-Caribbean immigrants.

Additionally, the findings underscore the crucial role of social networks and community support. Policymakers should consider funding initiatives that strengthen community ties, such as mentorship programs, community centers, and peer support groups that can help individuals navigate Canadian society.

Lastly, the concept of identity multi-positionality and its impact on social and cultural capital underscores the need for intersectional policy approaches. Policies must consider the overlapping identities of race, gender, class, and immigration status to effectively address the unique challenges faced by Afro-Caribbean communities.

Future Research: Future research should continue to explore the intersections of multiple social identities and their impact on the mobilization of social and cultural capital. As shown in previous work on Afro-Caribbean policy navigation, institutions often fail to fully account for the intersecting cultural and racial identities of Caribbean-origin Canadians, requiring more inclusive frameworks (Coen-Sanchez 2025a). Examining these dynamics in diverse cultural and geographical contexts will provide a more globally informed perspective on the experiences of marginalized and underrepresented groups. Further studies could also investigate the long-term effects of systemic inequalities on the social and economic outcomes of Afro-Caribbean communities and other immigrant groups. By advancing our understanding of these complex interactions, future research can inform more effective policies and practices to support the integration and well-being of immigrant communities.

11. Implications for Policy and Practice

The findings emphasize the critical role of cultural heritage and identity within Afro-Caribbean communities. Policy development could focus on supporting cultural preservation and celebration by funding cultural festivals and implementing educational programs incorporating Afro-Caribbean histories and contributions.

Addressing Racism and Discrimination: The study identifies pervasive experiences of racism and discrimination, particularly in the employment sector. This underscores the need for policies that promote equitable hiring practices, acknowledge foreign qualifications, and provide tailored career support services for Afro-Caribbean immigrants.

Enhancing Community Support: The research highlights the significance of social networks and community support. Policymakers might consider initiatives to strengthen community bonds, such as mentorship programs, establishing community centers, and developing peer support groups.

Intersectional Policy Approaches: The study underscores the necessity of intersectional policy frameworks that account for overlapping identities, including race, gender, class, and immigration status. Such approaches could address the unique challenges faced by Afro-Caribbean communities.

Educational Implications: The study’s findings could inform educational practices, particularly in developing curricula that recognize and value the experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities. This could contribute to fostering a more inclusive and respectful learning environment.

Despite its limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada. These insights carry significant implications for policy and practice, suggesting the necessity of more inclusive and supportive strategies to enhance these communities’ social and economic integration.

The interaction between resistance and identity multi-positionality is central to how Afro-Caribbean individuals mobilize social and cultural capital in Canada. Resistance, in this context, is not solely oppositional—it is a generative force that allows individuals to construct new meanings of Blackness and belonging by negotiating multiple social positions simultaneously. Identity multi-positionality—holding intersecting identities such as immigrant status, racialized subjectivity, generational cohort, and linguistic background—creates both constraints and possibilities. For example, second-generation participants often drew on their insider-outsider status to resist dominant norms in educational or professional spaces, asserting hybrid cultural expressions that were neither entirely Canadian nor entirely Haitian or Jamaican. These acts of resistance, rooted in multi-positional identity work, produce resistant capital (Yosso 2005), but also foster new forms of navigational and social capital by building networks and strategies to access institutions while maintaining cultural authenticity. In this way, resistance and identity multi-positionality do not merely coexist; they operate dialectically, with identity fluidity acting as a resource to transform marginalization into cultural leverage.

Although generational status offers a useful lens for examining how cultural capital is negotiated, it cannot be analyzed in isolation from gender and class. Gender, in particular, plays a critical role in shaping both the forms and expressions of capital. For Afro-Caribbean women in the study, cultural and social capital are often shaped through gendered roles, including expectations of emotional labor, respectability, and family caretaking. Several participants described navigating a dual burden—maintaining cultural traditions at home while facing gendered racial stereotyping in public institutions. For instance, second-generation Haitian and Jamaican women reported feeling pressured to perform professionalism in ways that minimized both their ethnic and gender expression. This aligns with broader research on Black women’s experiences in education and the workplace, where gender and race intersect to produce distinct challenges and modes of resistance (Gooden and Hackett 2020; Collins 2000). These patterns suggest that navigational capital among women is often marked by continuous self-regulation and code-switching, especially in predominantly white professional environments. For example, Haitian and Jamaican women across both generations often described a dual burden: navigating racialized expectations while also confronting gendered assumptions about their intellect, dress, or parenting style. This suggests that their navigational capital is highly gendered—shaped by expectations of respectability, emotional labor, and visibility. Similarly, class background—particularly parental occupation, income, and access to formal education—shaped how cultural capital was accumulated and transmitted intergenerationally. For second-generation participants, middle-class upbringing sometimes provided greater access to formal resources but also heightened the pressure to assimilate and “perform” professionalism in predominantly white spaces. Gender and class therefore do not simply modify generational experiences—they constitute the very terms through which cultural capital is interpreted, contested, and valued. This layered analysis aligns with Crenshaw’s (1989) theory of intersectionality and deepens our understanding of how Afro-Caribbean identity is navigated within Canada’s racialized world system (Robinson 1983).

12. Conclusions

This study has provided an in-depth examination of the dual identity and the complex interplay of social and cultural capital within first- and second-generation Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada, particularly focusing on the Jamaican and Haitian populations. The findings reveal that these communities leverage their cultural heritage and social networks to navigate systemic challenges, including racism and discrimination, while simultaneously preserving and adapting their cultural identities in a multicultural Canadian context.

Through the lens of Yosso’s theory of cultural wealth and the concepts of identity multi-positionality and resistance, the study highlights how Afro-Caribbean individuals and groups actively contest and redefine their social capital. This is done through the preservation of cultural practices, the creation of resilient social networks, and the assertion of a hybrid identity that bridges their Caribbean roots with their Canadian experiences.

The research underscores significant generational differences, with first-generation Afro-Caribbeans placing a stronger emphasis on cultural preservation and the direct impacts of discrimination, while second-generation participants focus on community integration and navigating stereotypes within Canadian society. Despite these differences, both generations highly value cultural heritage and community support as critical tools for overcoming systemic barriers and fostering a sense of belonging.

The study’s contributions extend to the broader discourse on immigrant integration, highlighting the importance of considering multiple intersecting identities in understanding the experiences of marginalized communities. By addressing the specific challenges faced by Afro-Caribbeans in Canada, this research provides valuable insights that can inform policies aimed at promoting social cohesion, cultural preservation, and equity within multicultural societies.

Future research should continue to explore the evolving dynamics of social and cultural capital among diverse immigrant groups, particularly through longitudinal studies that can capture the long-term impacts of these factors on identity formation and social integration. Additionally, expanding the focus to include other Afro-Caribbean communities in different geographical contexts would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the global immigrant experience.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genealogy10010006/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the The University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (protocol code S-10-22-8465 and 14 October 2022 date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, Malcolm, and John Loonam. 2010. Exploring the use of entity-relationship diagramming as a technique to support grounded theory inquiry. Paper presented at the European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, Madrid, Spain, June 24–25; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chattoraj, Diotima, and Anindya Basu. 2025. In search of identity: Perspectives from second generation South Asian diaspora. South Asian Diaspora 17: 191–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen-Sanchez, Karine. 2025a. Navigating Identity and Policy: The Afro-Caribbean Experience in Canada. Social Sciences 14: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen-Sanchez, Karine. 2025b. Polite Racism and Cultural Capital: Afro-Caribbean Negotiations of Blackness in Canada. Social Sciences 14: 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1967. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles L. Markmann. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, Patricia I., and Lawrence R. Ness. 2015. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 20: 1408–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, A., and V. C. R. Hackett. 2020. Race, Racialization and Systemic Racism in Canada: A Historical and Contemporary Perspective. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. 2023. Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population. November 15. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Hill, L. D., T. L. Mann, and S. R. Fitzsimmons. 2016. Racial identity and the politics of Blackness. In Cultural Diversity and Education: Foundations, Curriculum, and Teaching, 6th ed. Edited by James A. Banks. New York: Routledge, pp. 159–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2012. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pn9bk (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- James, Carl E. 2012. Students “at risk”: Stereotyping and the Ontario Safe Schools Policy. Canadian Journal of Education Administration and Policy 128: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Peter S. 2003. Deconstructing Canada’s discourse of immigrant integration. Journal of International Migration and Integration 4: 315–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreopoulos, Philip. 2011. Why do skilled immigrants struggle in the labor market? A field experiment with six thousand résumés. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3: 148–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, Jean S., Gabriel Horenczyk, Karmela Liebkind, and Paul Vedder. 2001. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues 57: 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Rubén G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reitz, Jeffrey G. 2007. Immigrant employment success in Canada: Part I: Individual and contextual causes. Journal of International Migration and Integration 8: 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Cedric J. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rolón-Dow, Rosalie. 2011. Race(ing) to class: Confronting the social and educational implications of Latino/a immigration and assimilation. Multicultural Perspectives 13: 193–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, Zoua M., Jennifer Sigouin, Astrid Flenon, and Alain Gagnon. 2019. The impact of population structure on socioeconomic inequality in health among immigrant groups. Population Research and Policy Review 38: 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Derron. 2017. Cultural capital as whiteness? Rethinking resources for academic achievement in U.K. Black Caribbean and Pakistani communities. Sociology 51: 247–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosso, Tara J. 2005. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education 8: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.