Abstract

Citizenship is not only a legal status but also a form of recognition. Every state defines who belongs by tracing lines of descent, yet the way ancestry is proven differs widely. This study compares nationality laws in Europe, Africa, and North America to show how evidence shapes access to citizenship. It asks what kinds of proof states require and what happens when those forms of proof are missing. The analysis draws on nationality laws, constitutional texts, case decisions, and administrative practice. The findings show that Europe relies on documents and registration systems that treat records as truth, while African states face gaps in documentation that leave many citizens unrecognised. In North America, technology and DNA testing have made biology a new measure of belonging. Across these regions, the law of descent has become a law of evidence. Documents and DNA dominate, while oral and community genealogy have lost authority. These evidentiary habits travel across borders, shaping how migrants and diasporas prove identity in a world that equates paperwork with legitimacy. The study concludes that certainty and fairness can exist together if states accept multiple paths to proof. When documents, sworn statements, and community testimony are combined, the law can recognise descent without excluding those who lack official records. Belonging should rest not only on what is written or tested but also on what is known and trusted.

1. Introduction

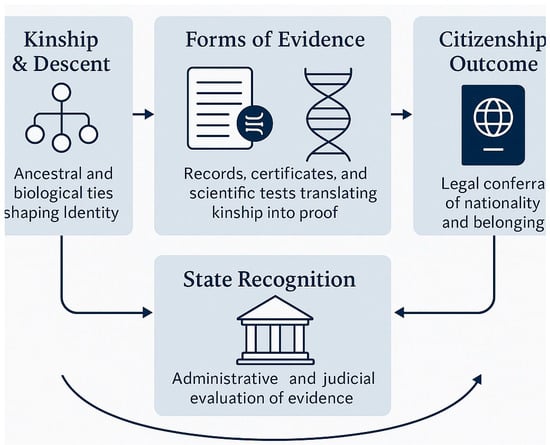

Nationality has never been only a matter of law. It is also a form of collective storytelling where descent, belonging, and recognition intersect. Every state must decide who inherits its membership, yet almost all depend in some way on genealogy. The assumption that citizenship flows through family ties remains deeply rooted in modern legal systems. What differs across jurisdictions is the kind of proof that states demand and the hierarchies of evidence they construct to translate kinship into legal identity. The relationship between genealogy, proof, and recognition illustrated in Figure 1 captures this continuum from family memory to legal membership. Understanding genealogy as an evidentiary practice rather than a simple record of ancestry helps illuminate how states decide who belongs and why proof of descent has become central to nationality law.

Figure 1.

From genealogy to citizenship: the relationship between kinship, evidence, and legal recognition.

This article begins from the idea that genealogy is not only a biological or historical claim but a form of evidence that must be interpreted by the state. This provides a theoretical basis for examining nationality law as a system that transforms social relationships into legal facts. By approaching genealogy in this way, the analysis moves beyond descriptive surveys and offers a conceptual frame for understanding how descent becomes credible in law.

In Europe, the relationship between genealogy and citizenship has been shaped by the long history of civil registration. Lineage is treated as something that can be verified through official archives. Common law countries such as the United Kingdom have added scientific testing to this documentary tradition, turning DNA into a secondary source of verification when records are incomplete (Wautelet 2011). Yet as Pallaver and Denicolò (2021) show in their study of Italy, confidence in documents often hides new forms of exclusion. Consular authorities have developed a near forensic standard of verification for diaspora descendants, creating uneven outcomes that depend on the survival of archival material. The comparative patterns summarised in Table 1 show how documentary systems dominate across European jurisdictions. Examining the legal rules together with the evidentiary thresholds reveals how these regimes rely not only on descent as a principle but on the kinds of proof applicants are realistically able to produce.

Table 1.

Overview of selected jurisdictions by legal tradition, descent rule, and dominant evidentiary form.

Across Africa, the legal picture appears inclusive, but the administrative reality is uneven. Most constitutions recognise citizenship by descent, but the procedures for proving it depend on documents many citizens never possessed (Manby 2016; Kapianga 2020). Oral genealogy, once central to how communities traced ancestry, carries little weight in modern nationality administration. Manby (2019) notes that even in states where customary systems of kinship verification remain strong, the evidentiary rules inherited from colonial bureaucracy now determine who is officially visible. The result is a paradox in which descent is affirmed in law but inaccessible in practice. The contrast between community-based genealogical authority and the documentary expectations introduced during the colonial period highlights the social and historical forces that shape the credibility of different forms of lineage.

In North America and parts of Asia, the challenge takes a different form. Genetic testing and digital databases have turned parentage into a question of biological fact. These technologies promise accuracy, yet as Seng (2001) shows in Cambodian repatriation cases, they can leave individuals trapped between incompatible bureaucracies when neither state accepts the available evidence. Kaneko-Iwase (2021) reaches a similar conclusion in her study of foundlings, where the search for absolute verification has weakened the protective legal presumptions once used to prevent statelessness. The growing use of DNA in citizenship cases reflects a shift toward biological certainty and raises deeper questions about how far legal systems should go in treating kinship as a measurable fact rather than a social relationship.

What connects these regions is the global movement of evidentiary expectations. States borrow one another’s standards through migration control, consular practice, and international cooperation. Documentary and genetic evidence now travel as if they were neutral tools, yet they carry the assumptions of the systems that produced them (Dumbrava 2014; Manby 2019, pp. 22–26). The cumulative effect is the emergence of a transnational evidentiary order in which documents and DNA are treated as the most authoritative forms of proof, while oral and community-based genealogies are increasingly displaced. This shared vocabulary of verification shapes nationality decisions across diverse legal traditions.

The contribution of this article is to show that citizenship by descent cannot be understood solely by examining statutory rules. It must also be analysed through the evidentiary practices that make those rules operational. By bringing together Europe, Africa, and North America, the study offers a comparative account of how states construct credibility and how these constructions circulate across borders. This responds directly to the need for a deeper theoretical explanation of genealogy as a legal practice rather than a symbolic reference to bloodline.

This article therefore examines how evidentiary hierarchies govern descent, how states evaluate second-generation claims abroad, and how the standards of proof developed in one region influence others. Using statutory texts, selected cases, and comparative country reports, it argues that citizenship today is sustained not only by ideas of blood or place but by a global genealogy of evidence that defines belonging through the language of verification.

By framing genealogy as both a social narrative and an evidentiary requirement, the article aims to clarify how nationality law distributes rights and recognition. It shows that the mechanisms used to establish descent shape access to citizenship as much as the substantive content of legal rules themselves.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

This study approaches nationality determination as an evidentiary project. Law does more than acknowledge kinship; it translates it into forms of proof that institutions can process. Genealogy becomes legally meaningful only when it is presented in ways that the administrative system recognises as credible. The framework developed here builds on four ideas: the hierarchy of acceptable evidence, the movement of evidentiary standards across borders, the relationship between certainty and access, and the genealogical logic that shapes contemporary citizenship systems. Together, these ideas explain why the verification of descent is now central to nationality law.

2.1. Evidentiary Hierarchies

Every state ranks the types of evidence it is willing to accept when determining descent. Documents sit at the top. Birth certificates, civil registers, parental marriage records, and official transcripts have become the primary markers of genealogical truth in legal systems built around stable record-keeping traditions, including those governed by the British Nationality Act, the German Basic Law, and Italy’s Citizenship Act Law 91 of 1992 (Wautelet 2011; Pallaver and Denicolò 2021). Their authority rests not on inherent accuracy but on the administrative belief that the archive reflects biological and social facts.

Where these documents are missing or contradictory, many states introduce biological evidence. DNA is presented as scientific confirmation of parentage, yet it still operates within state assumptions about which family relationships matter for nationality and which do not (Kaneko-Iwase 2021). These assumptions often exclude adoptive families, informal care arrangements, or kinship structures that are socially recognised but not inscribed in law.

Below these forms of evidence lies oral or community genealogy. It remains essential in social and cultural life, especially in regions where ancestry is preserved through collective memory rather than civil registration, but it rarely carries decisive legal weight without documentary or biological corroboration (Manby 2016; Kapianga 2020). These hierarchies are not natural. They reflect historical patterns of administration that elevate written or scientific records while marginalising traditional forms of genealogical knowledge.

2.2. The Circulation of Standards

Evidentiary rules do not remain confined within states. They move through migration procedures, consular decisions, and international cooperation. The Italian regime illustrates this movement clearly. Although Law 91 of 1992 allows broad transmission of citizenship by descent, consular officers routinely impose stringent evidentiary requirements that depend on original records from the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century archives. Even minor inconsistencies in names or dates can block an application entirely (Pallaver and Denicolò 2021). This shows how administrative practice can constrain entry into the national community even when statutory rules appear inclusive.

African systems reveal a different but related pattern. Constitutions such as those of Nigeria and Kenya guarantee citizenship by descent, yet applicants must produce documents rooted in colonial and early postcolonial registration practices that many families never accessed (Manby 2016, 2019, pp. 22–26). The right of descent and the ability to demonstrate it therefore come apart in practice. Repatriation and removal disputes show similar problems from another angle. Seng’s study of Cambodian nationality cases describes individuals caught between two states that each demands documentary proof that the other will not recognise (Seng 2001).

Evidence, therefore, circulates informally through institutional contact. As states borrow one another’s evidentiary expectations, they create a transnational template for acceptable proof. This template influences nationality decisions even in jurisdictions that have never harmonised their citizenship laws.

2.3. Certainty and Access

Debates about proof often frame certainty and fairness as opposing goals. The comparative record suggests that they can coexist. Foundling rules make this clear. When parentage is unknown, many systems presume citizenship at birth to prevent statelessness, as reflected in the British Nationality Act, the United States Immigration and Nationality Act Section 301, and protections found in African constitutions (Kaneko-Iwase 2021). These presumptions safeguard the register without relying on strict documentation.

European jurisprudence on restoration of citizenship shows how rights-based reasoning can moderate strict evidentiary demands in cases where displacement or historical trauma disrupted the archival record (Dumbrava 2014, pp. 101–5). African country reports reveal additional methods for balancing certainty and access. Layered affidavits, retrospective registration campaigns, community attestations that carry legal consequences if falsified, and the selective use of DNA testing can all strengthen the credibility of claims without excluding those whose ancestors lived outside formal registration systems (Manby 2016; Kapianga 2020; Bauböck 2021).

Certainty is not tied to a single form of evidence. What matters is a coherent process that allows multiple sources of genealogical truth to be considered without compromising legal reliability.

2.4. Operational Concepts

The comparative analysis uses four categories that appear consistently in both the literature and administrative practice.

Documentary proof refers to civil registers and certified records issued under laws such as the British Nationality Act, the German Basic Law Article 116, Italy’s Law 91 of 1992, the Constitution of Nigeria Section 25, and the Constitution of Kenya Article 14 (Wautelet 2011).

Biological proof refers to the use of DNA or specialised parentage tests in cases governed by the United States Immigration and Nationality Act and the Canadian Citizenship Act when documents are unavailable or contested (Kaneko-Iwase 2021).

Testimonial and community proof includes sworn statements, local authority attestations, and traditional lineage confirmations. These forms of evidence are authoritative in social life but rarely decisive without corroboration (Manby 2016; Kapianga 2020).

Legal presumptions and safeguards include protections for foundlings, rebuttable presumptions of parentage, and restoration measures designed to address historical erasure, as seen in German postwar restitution processes (Dumbrava 2014, pp. 101–5).

These categories make it possible to compare legal systems that rely on different genealogical traditions without forcing them into a single evidentiary model.

2.5. Why Genealogy Matters for Citizenship Law

Citizenship debates often present descent and birth on the territory as opposing principles. The comparative record shows that the decisive issue is not which principle dominates but how those principles are verified. European systems rely on extensive archival infrastructures (Wautelet 2011). African systems rely on constitutional commitments that are undermined by uneven administrative capacity (Manby 2016, 2019, pp. 22–26; Kapianga 2020). North American systems increasingly rely on biological verification under the Immigration and Nationality Act and the Canadian Citizenship Act (Seng 2001; Kaneko-Iwase 2021).

Genealogy matters because it is the channel through which the state transforms family relationships into legal identity (Ziegler 2021). The structure of proof is therefore as important as the substantive rule of descent itself.

2.6. What Follows from the Framework

The regional sections that follow apply this framework to assess where documentary primacy prevails, when DNA enters the file, where oral genealogy still influences decision making, and how legal presumptions close evidentiary gaps. The framework also explains how evidentiary expectations travel through consular decisions and migration governance, creating a global vocabulary of proof that shapes nationality adjudication across diverse legal traditions. By treating genealogy as evidence, the framework provides a coherent analytical lens through which the comparative findings gain depth and interpretive clarity.

3. Methodology

This study uses a comparative legal approach to understand how different states construct and verify descent in nationality law, and how those methods of proof circulate across borders. Comparison is essential because the idea of descent is universal, but the systems that define and test it are shaped by each country’s history, bureaucracy, and sense of belonging. This approach places genealogy at the centre of the inquiry by treating descent not simply as a legal category but as a form of inherited social identity that becomes authoritative only when translated into state-recognised evidence. The method follows a problem-centred logic: states everywhere must determine who inherits membership, and examining how they evaluate evidence of lineage reveals the deeper structure of their citizenship regimes.

3.1. Research Design

The work combines legal interpretation with contextual analysis. It begins with the reading of nationality laws, constitutional clauses, and citizenship regulations in selected countries across Europe, Africa, and North America. These legal texts are then considered alongside case law, administrative practice, and scholarly commentary. The approach follows the functional comparison described by Wautelet (2011) and Manby (2016), which highlights how systems solve equivalent problems under different institutional conditions. This combination allows genealogical concepts such as lineage, filiation, and parental recognition to be examined as both legal constructs and lived social facts, thereby grounding the comparative exercise in a coherent theoretical frame.

Primary legal materials include the British Nationality Act 1981, the German Basic Law Article 116, the Italian Citizenship Act (Law 91/1992), the Constitution of Nigeria 1999 Section 25, the Kenya Constitution 2010 Article 14, the United States Immigration and Nationality Act Section 301, and the Canada Citizenship Act Section 3. Judicial decisions that interpret evidentiary rules were also incorporated, including Attorney General v Unity Dow (Botswana Court of Appeal 1992), the Italian Consiglio di Stato Decision No. 4462 (2017), and INS v Pangilinan (US Supreme Court 1988). These materials provide the genealogical anchors of each legal system by showing how states legally define parentage, affiliation, and transmission of identity.

This design allows statutory provisions, judicial rulings, and administrative instructions to be treated as parallel evidence sources, making it possible to analyse not only what the law says but how it is operationalised through institutional practice.

3.2. Jurisdiction Selection

Ten countries were chosen because they represent distinct legal traditions and regional experiences (see Table 1). In Europe, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy show how well-established bureaucratic states manage descent through documentation, registries, and, increasingly, genetic testing (Wautelet 2011; Pallaver and Denicolò 2021). These jurisdictions also provide access to authoritative primary materials, including nationality acts such as the British Nationality Act 1981, the German Nationality Act, and Italy’s Law 91 of 1992, allowing close textual comparison. This mix of systems captures how genealogy becomes credible through documents and archives in mature registration states.

Although Africa contains several colonial legal traditions, this study focused on former British-administered jurisdictions for a deliberate methodological reason. These states share a similar documentary and administrative inheritance based on common law practice, local government attestation, and the use of sworn affidavits. They also have comparable post-independence reforms in birth registration, national identity systems, and constitutional definitions of descent. Focusing on one legal family made it possible to compare evidentiary expectations without introducing variation created by different civil registration philosophies.

Former French, Portuguese, Spanish and Belgian colonies often rely on a different evidentiary tradition influenced by the possession d’état doctrine, which links civil status to social recognition and long-term appearance in a family relationship. This creates a distinct genealogy of proof that deserves its own focused treatment. Including both legal families in the same frame would have widened the scope but reduced analytical depth. A separate comparative study could examine how the possession d’état tradition interacts with documentary and biological evidence in citizenship by descent.

Restricting the African sample to the British-influenced group, therefore, provided a coherent evidentiary field while still revealing the structural tensions between documentary requirements, oral genealogy and administrative capacity.

In Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Zambia, and Kenya demonstrate how constitutional rights to citizenship by descent operate in environments where documentary records are uneven (Manby 2016; Kapianga 2020). Each of these states offers a different configuration of statutory entitlement and administrative challenge, from Nigeria’s constitutional definition of citizenship by parentage to Zambia’s detailed statutory provisions on proof of nationality. Their inclusion highlights settings where genealogy is socially robust but legally under-documented, revealing how states reconcile ancestral knowledge with bureaucratic verification.

In North America, the United States and Canada illustrate how advanced technologies and migration histories reshape verification of parentage (Kaneko-Iwase 2021; Seng 2001). These cases also provide rich primary materials, including the United States Immigration and Nationality Act and Canadian legislative rules governing proof of parentage for foreign-born children. These jurisdictions reveal a contrasting evidentiary model in which genealogy is increasingly read through biological and digital markers.

3.3. Data Sources

The analysis draws on both primary and secondary material. Primary sources include nationality statutes, administrative regulations, and judicial decisions obtained through official gazettes, HeinOnline, and national legal databases. These are supported by comparative reports such as the Report on Citizenship Law: Zambia (Kapianga 2020, pp. 13–17), Manby’s Citizenship Law in Africa (2016), and regional studies published by UNHCR and GLOBALCIT. Secondary materials include theoretical and policy analyses by scholars who have examined the evolution of evidentiary standards of citizenship law (Dumbrava 2014; Kaneko-Iwase 2021). Using both codified rules and published judgments enables the study to identify not only what states require on paper but also how those requirements are interpreted by decision-making bodies. This layered sourcing ensures that the study evaluates descent as both a doctrinal construct and a genealogical practice mediated through the evidentiary expectations of the state.

3.4. Analytical Process

All data were organised around four types of evidence identified earlier in the conceptual framework: documentary, biological, testimonial or community-based, and legal presumptions. Within each category, the analysis examined the legal status of the evidence, its accessibility, its weight in decision-making, and the level of discretion allowed to administrative or judicial officers. This procedure made it possible to compare jurisdictions that differ in language, legal tradition, and administrative strength while preserving coherence across the dataset. The findings were synthesised in a comparative evidentiary matrix that will appear later in this paper. This structured approach allows the analysis to capture convergences in evidentiary practice even where substantive nationality rules diverge widely. It also exposes how different states assign legal authority to genealogical knowledge, illustrating the pathways through which ancestry becomes a matter of proof.

3.5. Ensuring Reliability

Comparative studies risk uneven data and interpretive bias. To address this, legislative texts were cross-checked with country reports and judicial commentary. Where legal documents were silent on evidentiary hierarchies, administrative practice was reconstructed from reports by the United Nations and independent legal experts. This triangulation of statutory sources, practice, and academic review provides a consistent and verifiable basis for comparison. The inclusion of multiple data layers—law, practice, and interpretation—ensures that findings do not rely on any single source or jurisdictional assumption. This safeguards analytical coherence across regions with radically different genealogical traditions and administrative capacities.

3.6. Ethical and Interpretive Stance

Citizenship touches personal identity and family history. The analysis therefore focuses on institutional processes rather than individual cases. Examples are drawn only from published materials or official rulings. Following Dumbrava (2014) and Kaneko-Iwase (2021), the study treats nationality law as both a legal framework and a social practice that reflects deeper hierarchies of belonging. No confidential or identifiable information is used, and all examples derive from publicly accessible records, ensuring compliance with standard research ethics for legal scholarship. This approach also respects the cultural sensitivity of genealogical claims, which often carry social meaning beyond their legal expression.

3.7. Limitations

The study does not claim to represent every global system. Other regions, such as Latin America and East Asia, follow different descent traditions that deserve separate treatment. It also recognises that law on paper does not always match practice, which may be shaped by local politics or administrative discretion. Still, by aligning data from three continents within one evidentiary structure, the analysis captures the broader global movement toward documentation and biological verification as dominant modes of proving descent. The limitations of scope therefore do not undermine the analysis; they highlight the distinct evidentiary patterns that recur across diverse legal settings. These limitations emphasise that genealogical analysis is context-dependent and that evidentiary practices evolve in ways shaped by each state’s administrative history.

4. Europe: Genealogical Proof in Civil and Common Law Contexts

Genealogy in Europe is not simply a record of parentage. It is the foundation of a bureaucratic tradition that treats lineage as something that can be verified through state archives. European citizenship regimes assume that family history becomes legally meaningful only once it enters the civil register. This makes Europe an important starting point for understanding how genealogy becomes evidence. The European model shows how states transform ancestry into a documentary trail and how this documentary trail becomes the legal truth through which descent is recognised.

Europe offers perhaps the clearest example of how genealogy becomes legal only when it is translated into documents. Centuries of civil registration have created the illusion that lineage can be proven with certainty, yet that certainty depends on an administrative faith in paperwork rather than an inherent truth about ancestry. Both civil and common law traditions share this reliance on the written record, though they manage it in slightly different ways. Underlying this is a distinct European genealogy culture in which kinship becomes authoritative only when stabilised through formal registration, a practice that has shaped how states imagine and police descent across generations.

This dependence on documentation reflects the long historical development of European state institutions, which equated bureaucratic order with social truth and gradually embedded written lineage into the legal imagination. The archival model treats ancestry as something fixed and traceable, privileging records over narrative and requiring families to articulate their genealogy through state-managed documents rather than inherited memory (Trucco 2023).

In civil law countries such as France, Germany, and Italy, descent is recognised automatically once it appears in official registers. The civil code treats the record itself as the proof. Birth certificates, marriage entries, and family books are presumed accurate unless challenged in court. The assumption is that the state’s documentation system mirrors biological and social reality. Wautelet (2011) describes this as a “documentary presumption of truth,” a form of evidentiary logic that leaves little room for alternative proofs such as witness statements or oral genealogy. This approach works well for citizens born and recorded within national borders but becomes fragile when applied to migration, diaspora, or naturalisation cases. Here, genealogical identity is forced into the structure of the archive, which can validate some lineages and erase others simply through the presence or absence of paperwork (Voutira 2011).

The strength of the system, therefore, becomes its weakness: absolute reliance on documents makes the framework precise for those with complete records and inaccessible for those whose family histories fall outside state archives. This creates what some scholars describe as “archival asymmetry,” where established families appear genealogically coherent because they are well documented, while mobile or marginalised groups seem genealogically uncertain solely because the state did not record them.

Italy demonstrates the tension most visibly. The law recognises citizenship by descent without generational limit, meaning that children and grandchildren of Italian emigrants can reclaim citizenship if they can prove an unbroken line to an Italian ancestor. In theory, the provision is inclusive; in practice, it is a bureaucratic marathon. Consulates require original civil records, translations, and apostilles that trace back to the nineteenth century. Pallaver and Denicolò (2021) note that consular officers often reject applications over minor discrepancies in dates or spellings, effectively transforming genealogy into an audit of archival precision. This system elevates clerical accuracy over lived kinship, making tiny variations in record-keeping more determinative than the underlying genealogical truth.

This dynamic reveals how evidentiary scrutiny can quietly narrow access even when statutory language appears broad and generous. It also shows how genealogy, when filtered through paperwork, becomes vulnerable to historical gaps, name changes, inconsistent registries, and the unequal preservation of records across regions and social classes.

Germany presents a related but distinct history. After the Second World War, the Aussiedler programme granted citizenship to ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe based on descent and cultural affiliation. Galen-Murray and Schmidtke (2016) show how this process used genealogy to rebuild the nation while simultaneously enforcing ethnic boundaries. Proof of Germanness rested on birth records, church registers, and linguistic tests rather than self-identification (Joppke et al. 2001). The case reveals how descent, evidence, and national identity converge within legal structures that claim neutrality but carry historical and cultural weight. The programme illustrates how states use genealogy to shape national narratives by deciding which lineages qualify as authentic and which fall outside what Benedict Anderson describes as the imagined community of the nation, a form of belonging constructed through shared historical narratives, institutions, and legal recognition rather than direct social ties (Anderson [1983] 2006; Zambon 2021). The German example demonstrates that documents can function as instruments of both inclusion and exclusion by embedding ethnic narratives within legal proof. It also highlights how states interpret genealogy through the lens of national history, turning archives into tools that stabilise certain ancestral claims while filtering out others that do not align with state identity projects.

France occupies a middle ground between jus sanguinis and jus soli. Descent remains a valid route to nationality, yet the state’s secular tradition and bureaucratic exactness make documentation the only acceptable form of proof. Affidavits and family testimonies are rarely considered sufficient. For migrants and refugees, this rigidity often leads to exclusion, as personal history collides with administrative proof. This creates a system in which legal entitlement is overshadowed by evidentiary capacity: those unable to reconstruct documented lineage struggle to activate the rights the law formally grants them. The French case thus illustrates how genealogical belonging can be legally acknowledged while practically constrained by the evidentiary form required to demonstrate it.

In the United Kingdom, which follows a common law tradition, the same documentary culture prevails but with more judicial discretion. The British Nationality Act of 1981 curtailed automatic transmission of citizenship and placed greater emphasis on registration and parental status. Wautelet (2011) and Thwaites (2022) both note that courts in deprivation and registration cases evaluate “proof of foreign nationality” or “proof of descent” through a mix of documents and DNA evidence. Biological testing is used as a last resort when documents are disputed or unavailable. While this appears pragmatic, it still frames belonging as a matter of verification rather than community or identity. Judicial discretion therefore softens but does not fundamentally alter the centrality of records, reinforcing the larger European pattern in which genealogy gains validity only when translated into administrative form. This demonstrates how common law systems retain narrative flexibility yet ultimately reaffirm the evidentiary hierarchy that privileges written and biological proof.

Across these jurisdictions, one pattern stands out. The European state imagines citizenship as something that can be archived. Lineage is credible only when it passes through documents that the bureaucracy can read and authenticate. Oral histories, family memory, or local recognition hold no legal value, even when they capture truths the record omits. This evidentiary culture elevates written and biological proof above all other genealogical forms, producing a model of citizenship that privileges archival continuity over lived or communal histories. Genealogy becomes valid only when it conforms to the state’s evidentiary imagination, turning descent into a bureaucratised narrative rather than a relational or cultural one.

This has broader implications for how Europe exports its standards abroad through consular practice and migration regulation, creating global ripple effects that define how descent is judged elsewhere. The evidentiary logic developed in Europe now influences international documentation programmes, humanitarian registration systems, and migration vetting procedures, effectively globalising the archival model of genealogy.

The following section turns to Africa, where descent remains central to nationality law but operates in a very different evidentiary environment, one where documentation is scarce, oral genealogy still carries social authority, and state recognition often depends on negotiation rather than proof.

5. Africa: Oral Lineage, Documentary Gaps, and the Politics of Recognition

Genealogy across Africa follows a different logic. Family history is preserved through memory, community testimony, and collective recognition. These forms of knowledge operate outside state archives yet hold deep authority within social life. When nationality law tries to translate these genealogical traditions into administrative evidence, tensions emerge. The African context therefore reveals how states handle lineage in environments where ancestral knowledge is strong but documentary systems are fragile or incomplete.

If Europe built its citizenship system on documents, Africa inherited a more complex mix of memory, law, and bureaucracy. Descent is central to almost every African nationality regime, yet proving it often depends on institutions that are only partly bureaucratic and partly social. The region’s legal frameworks appear generous on paper, but their evidentiary structures remain shaped by colonial administrative legacies and uneven recordkeeping. These structures shape not only how ancestry is verified but also whose genealogies the state is prepared to acknowledge as credible.

Across many African countries, the right to nationality by descent is written directly into constitutional or statutory law (Manby 2020). Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Zambia all recognise citizenship through parentage, typically from either parent at birth. The challenge lies not in the principle but in the proof. Manby (2016) notes that post-independence legal reforms retained the colonial assumption that belonging can be established through documents issued by the state, an expectation that many citizens have never been able to meet. Birth certificates, identity cards, and passports exist in law but are often inaccessible in rural areas, where births are registered late or not at all. This gap between lived kinship and bureaucratic lineage demonstrates the central genealogical issue across the region. The state asks for a form of ancestry that reflects its own administrative history rather than the ways families actually preserve and transmit knowledge of descent.

In Nigeria, citizenship by descent is constitutionally guaranteed, yet the requirement to show official proof of parentage has turned many legitimate claims into legal disputes. Local governments issue affidavits and letters of attestation, but these are rarely accepted as final evidence by federal authorities (Chukwu 2016; Manby 2016). The result is a dual system of recognition, one grounded in community knowledge and the other in bureaucratic formality. The same tension appears in Ghana, where registration is central to confirmation of descent. Those born abroad to Ghanaian parents must produce both a birth certificate and a certificate of citizenship registration. In practice, even minor discrepancies can delay or invalidate an application (Manby 2019, pp. 22–26). These examples show how rigid evidentiary frameworks can flatten the texture of African genealogical knowledge by treating local and clan-based histories as auxiliary rather than foundational sources of identity.

Zambia’s two thousand sixteen constitutional reforms were intended to modernise citizenship law and permit dual nationality, but the evidentiary barriers remain high. Kapianga (2020) reports that applicants must still produce birth records, national registration cards, or parental passports. For many Zambians living abroad or born before systematic registration, these records are missing. The result is that the law appears inclusive, yet its enforcement narrows who can qualify. Legal belonging depends less on ancestry and more on documentation inherited from colonial administrative structures (Yapo 2020). This highlights a deeper genealogical point. The state recognises lineage only when it appears in formats that mirror colonial bureaucratic habits, even though these formats were never designed to reflect African kinship systems.

Kenya shows a more progressive trend. The two thousand ten Constitution explicitly recognises equal transmission of citizenship through either parent, correcting earlier gender disparities. Yet even here, the administrative procedures require documentary confirmation, often from registries established only in the late twentieth century (Flaim 2015; Manby 2016). When a person’s ancestry predates those registries, they must rely on affidavits or local testimonials that carry little formal weight. This demonstrates the disjuncture between state-centred genealogy and community-centred genealogy, where the former privileges written evidence while the latter relies on oral succession, clan affiliation, and collective memory.

Oral genealogy remains an important social institution across Africa, but it occupies a marginal place in formal law. Families, clans, and traditional authorities can trace descent across generations with remarkable precision, yet their testimony is treated as informal knowledge rather than admissible evidence. Manby (2019) observes that the shift from communal recognition to state paperwork has created a class of paperless citizens, people whose belonging is unquestioned locally but invisible legally. This invisibility has serious consequences, as individuals without documentary proof of descent may be denied passports, voting rights, or access to education. From a genealogical perspective, the state effectively redefines heritage by validating only those lineages that pass through documentary filters, thereby silencing histories preserved through narrative, ritual, and collective memory (Rafiei 2012).

The African cases in this study focus on jurisdictions shaped by common law and British administrative legacies, reflecting the availability of detailed statutory materials and comparative reports. This does not imply that other African regions follow identical evidentiary logics. Former French, Belgian, Portuguese and Spanish territories often rely on the civil law doctrine of possession d’état, a form of inferred civil status that treats long-standing social recognition of parentage as a legally relevant fact. These systems incorporate community recognition in ways that differ from the British-inspired registries examined here. A full treatment of these civil law-based approaches lies beyond the scope of this article, but acknowledging their distinct evidentiary practices helps situate the chosen cases within Africa’s wider genealogical landscape.

The broader implication is that African nationality regimes reproduce a colonial paradox. They celebrate descent as the foundation of citizenship but rely on administrative tools that privilege those with access to documentation (Manby 2016, pp. 45–47; Kapianga 2020, pp. 13–17). Both argue that this gap can be narrowed through flexible evidentiary procedures. Affidavits, layered witness statements, and retrospective registration have been used successfully to validate ancestry without compromising state integrity. These practices show how genealogical truth can emerge from multiple forms of verification when the law is willing to treat lineage as a lived reality rather than a purely archival one.

The African experience reveals the deeper politics of recognition in nationality law. Proof of descent is not only a legal exercise but also a negotiation over which histories the state is prepared to believe. The line between citizen and outsider is often drawn not by lineage itself but by the format in which that lineage is recorded. This underscores the central argument of the article. Genealogy matters not simply as a legal principle of descent but as a mode of knowing family history (Oucho 2017). Citizenship systems that elevate documents above lived genealogies risk misrecognising the very communities they seek to regulate.

The next section turns to North America, where the documentary state meets the biological state. There, DNA testing and digital verification systems have reshaped the meaning of evidence, raising new ethical and legal questions about how ancestry becomes citizenship.

6. North America: Diaspora, DNA, and the Biological Turn in Proof of Citizenship

In North America, genealogy is increasingly measured rather than narrated. Documentation still matters, but biological testing and digital identity systems redefine how the state evaluates parentage. This region shows how genealogy becomes intertwined with science and technology, turning descent into a matter of biological verification. North America, therefore, adds a new dimension to the comparative picture by demonstrating how modern states seek certainty in ancestry through scientific proof.

In North America, the story of descent and citizenship has entered a new phase, one defined not by paperwork alone but by biology and data. The region’s long-standing emphasis on birthright citizenship coexists with an increasingly technical approach to proving descent for those born abroad. Here, the state’s trust in documents has been reinforced, not replaced, by a growing faith in genetic evidence and digital verification. This shift shows how the state now treats identity as something that must be scientifically demonstrated rather than socially recognised. This evidentiary perspective reflects a deeper genealogical logic in which ancestry is understood as a biological fact that can be extracted, measured, and authenticated, rather than a family narrative that is socially remembered or affirmed within communities (Mohamed and Mohsen 2025).

In the United States, the transmission of citizenship by descent is governed by the Immigration and Nationality Act, which allows children born abroad to acquire citizenship if at least one parent is a citizen and certain residence requirements are met. In principle, the law acknowledges descent as a legitimate path to membership. In practice, the process depends on a dense network of documents such as passports, consular birth reports, marriage certificates, and proof of the parents’ physical presence in the country before the child’s birth. When any of these elements are missing or disputed, applicants are increasingly asked to provide DNA results to confirm biological ties (Kaneko-Iwase 2021; Seng 2001). The growing demand for genetic evidence reveals an administrative preference for measurable certainty even when the legal rule itself does not require biological verification. This preference illustrates how the state reads genealogy through evidentiary formats that privilege biological parentage above other genealogical relations, such as caregiving or customary kinship, shaping legal recognition through a particular understanding of family lineage.

The rise of genetic testing reflects both technological confidence and administrative caution. It allows consular officers to resolve cases that would otherwise depend on uncertain or forged documents, but it also introduces a narrow definition of kinship. Families formed through adoption, assisted reproduction, or informal care arrangements often fall outside these biological parameters. Seng shows how this logic plays out in Cambodian repatriation cases, where United States and Cambodian authorities both demanded biological proof that neither system could fully provide (Seng 2001). The individuals involved were left stateless, not because they lacked ancestry but because their ancestry could not be verified in the approved form. These cases demonstrate how the absence of scientific evidence becomes a barrier that overrides both community recognition and lived family relationships. Such episodes reveal how the state’s evidentiary logic limits the genealogical imagination to biological descent, marginalising familial bonds that arise from social practice or cultural norms.

Canada follows a similar pattern with its own variations. The two thousand nine amendments to the Citizenship Act limited citizenship by descent to the first generation born abroad. Children of Canadian citizens born outside the country after that point must apply for naturalisation. This rule was introduced to address what policymakers perceived as citizenship without connection. Although efficient administratively, it reflects a deeper shift. Citizenship by descent is no longer an automatic inheritance but a claim that must be proven and confirmed through state procedures (Kaneko-Iwase 2021). Proof depends heavily on documentary evidence, with DNA used only when necessary to resolve disputes. This emphasis on verification shows how Canadian citizenship law treats descent not as a social bond but as an evidentiary burden that must be satisfied through precise and authoritative records. The rule also redefines genealogical continuity by placing weight on generational proximity, effectively drawing a legal boundary around which family histories count as sufficiently connected to the nation.

Both countries show how the language of evidence has changed. Where earlier systems relied on testimony and documents, the twenty-first century has introduced molecular biology as an arbiter of truth. DNA testing now sits at the intersection of technology, law, and ethics. It is treated as neutral, yet its application raises questions about privacy, family rights, and the limits of legal imagination. Kaneko Iwase argues that the overreliance on biological verification risks replacing the presumption of belonging with the presumption of doubt (Kaneko-Iwase 2021). This represents a profound shift in the relationship between the individual and the state, as citizenship becomes contingent on passing an evidentiary test. This transformation illustrates how the genealogical lens in North America aligns more closely with biological science than with cultural or familial understandings of kinship, narrowing the range of identities that the legal system can recognise.

Another defining feature of North American practice is the digitisation of identity. Birth records, immigration files, and family registries are increasingly stored and cross-checked through digital databases. This makes verification faster but also more exclusionary for those without access to digital infrastructure or historical records. For diasporic families, especially those from regions with weak documentation systems, the evidentiary expectations of North American authorities can become insurmountable. As Dumbrava notes, these systems create global hierarchies of evidence where the standards of the Global North determine the credibility of genealogies elsewhere (Dumbrava 2014, pp. 101–5). Digitisation therefore multiplies the advantages of families with stable archival histories while deepening the disadvantages of those whose genealogies were never recorded within a bureaucratic tradition. The spread of digital verification tools also extends this evidentiary hierarchy beyond North America, as international cooperation initiatives encourage other states to adopt the same documentation and biometric protocols.

What emerges across North America is a model of descent that treats citizenship as a question of measurable fact. Proof has become procedural rather than relational, scientific rather than narrative. This model is now exported through immigration vetting, bilateral agreements, and development programmes that promote biometric registration worldwide. The region’s commitment to certainty, however, comes at a cost. It narrows the meaning of kinship and leaves little space for cultural or communal understandings of lineage. This evidentiary logic influences other regions through legal cooperation and policy transfer, reinforcing a global expectation that identity must be documented, scanned, and biologically verified. This export of evidentiary norms demonstrates how genealogical practices developed in one region can reshape the recognition of ancestry far beyond its borders, creating a shared global expectation of what credible lineage looks like.

The North American experience completes the comparative picture. Europe built the evidentiary state through documents. Africa negotiates it through oral and hybrid forms. North America refines it through biology and data. Together, they show that citizenship by descent is not only about who one’s parents are but about how states decide to believe that relationship. The next section examines how these evidentiary expectations move across borders and shape the experience of migrants and diasporas navigating multiple systems of proof.

7. Comparative Analysis: The Circulation of Evidentiary Regimes

The comparison across regions reveals a quiet but powerful truth about modern nationality law: the way states define proof of descent is no longer purely domestic. Standards of evidence travel. They move through migration systems, consular practice, and international agreements, reshaping how belonging is recognised around the world. What began as national administrative routines has evolved into a global evidentiary order. This circulation reflects a deeper genealogical dynamic in which states project their own assumptions about lineage, identity, and verification beyond their borders, creating shared expectations about what credible ancestry looks like.

This circulation of standards shows how citizenship law is increasingly shaped by transnational expectations rather than the internal logic of any single jurisdiction. Consulates, immigration officers, and judicial bodies routinely rely on evidentiary norms shaped elsewhere, harmonising their practices even when their legal traditions differ.

In Europe, the bureaucratic confidence in documents reflects a long tradition of civil registration and record keeping. Citizenship is presumed to exist within the archive. Once a birth certificate or family register confirms parentage, the state’s work is considered complete. Even DNA testing, when used, reinforces this documentary faith. The European model assumes that certainty flows from the archive and from the bureaucratic expertise required to maintain it. This approach now informs the evidentiary logic of many international organisations and development programmes that promote civil registration as a global priority (Wautelet 2011; Pallaver and Denicolò 2021). The export of this model means that the European understanding of documentary certainty increasingly frames what international institutions treat as credible proof of ancestry. This influence is visible in initiatives supported by the European Union and the United Nations that encourage states to modernise civil registers, adopt centralised databases, and link nationality determination to standardised documents.

Africa’s experience exposes the limits of that model. Postcolonial states inherited the machinery of registration without the administrative reach required to make it universal. Manby and Kapianga show that while most African constitutions promise descent-based citizenship, these promises remain dependent on record systems that many citizens cannot access. The persistence of oral genealogy and local attestation reflects a parallel evidentiary tradition rooted in social recognition rather than formal documentation. Yet, when African citizens or diasporas engage with foreign authorities, especially European or North American ones, their claims are filtered through external evidentiary expectations. What counts as valid proof at home carries little weight abroad, even when it is credible within local social structures (Manby 2016; Kapianga 2020). This mismatch reveals how global documentary hierarchies can override local forms of legitimacy, producing new forms of exclusion that are not inherent in domestic law but imported through transnational interactions. The evidentiary gap widens further when foreign authorities require documents that never existed historically, overlooking the genealogical systems through which African communities have long validated lineage.

In North America, the biological turn adds a distinct layer to this global movement. DNA testing and digital identity verification have become symbols of modern certainty. These technologies migrate through policy exchange, technical assistance, and bilateral cooperation, shaping what many states now view as necessary tools for credible citizenship administration. Dumbrava describes this as the standardisation of certainty, a process through which Western evidentiary preferences are exported as universal benchmarks (Dumbrava 2014, pp. 101–5). This technological influence introduces an additional layer of hierarchy, where scientific verification is presented as globally authoritative even in regions where genealogical knowledge is traditionally preserved through collective memory and community testimony. The prominence of the United States Immigration and Nationality Act and Canadian parentage rules reinforces this shift, as both legal systems rely on biological verification for disputed claims, thereby associating genealogy with measurable scientific truth.

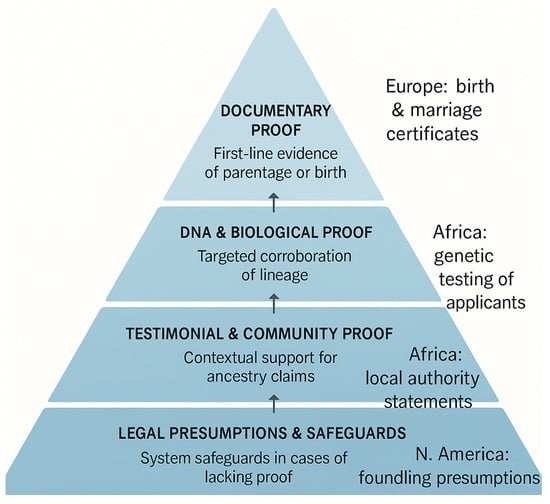

Taken together, these patterns produce a shared evidentiary hierarchy. At the top stand documents such as civil records and official registries, treated as first-line proof. Biological evidence occupies the next tier, deployed for corroboration when documents are absent or contested. Below these are testimonial and community-based forms of proof, which provide context but rarely carry decisive legal weight. At the base are legal presumptions such as foundling rules and restoration clauses, which act as safeguards when other evidence is unavailable. This hierarchy, reflected visually in Figure 2, demonstrates how global citizenship systems increasingly speak a common evidentiary language even when their historical and cultural foundations differ. The structure also reveals how genealogical knowledge becomes legally relevant only when translated into formats compatible with this hierarchy, limiting recognition of lineage forms that fall outside documentary or biological norms.

Figure 2.

A hierarchy of evidence for proving descent.

The global circulation of these regimes has profound consequences. It creates a world where access to nationality depends on proximity to documentation, technology, and administrative infrastructure. Migrants and diasporas who move from low-documentation environments to high-documentation systems often find themselves caught between incompatible standards. A Ghanaian-born child recognised locally through oral lineage may struggle to prove the same ancestry at a European consulate. An American-born child of parents with incomplete records may face delays when registering citizenship abroad. These scenarios are not anomalies but predictable outcomes of an evidentiary order that equates legitimacy with documentable truth. The people most affected are those whose family histories cannot be reduced to documents or DNA, revealing how the evidentiary hierarchy reproduces inequalities that have little to do with the substance of descent and everything to do with the form of its presentation.

The resulting inequalities show that citizenship by descent does not simply reflect family connections but the availability of evidence that meets transnational expectations. This makes the evidentiary burden a central determinant of access, often more decisive than the underlying genealogical fact.

What this comparison makes clear is that the law of nationality has evolved into a law of proof. It governs not only who belongs but how belonging must be demonstrated. Documents and DNA have become the lingua franca of credibility, while oral and communal genealogies persist only at the edges of legal recognition. The challenge for reform is to recognise that certainty does not require a single evidentiary form. Multiple credible pathways can coexist without undermining the integrity of nationality systems. Such reforms would reflect a broader understanding of genealogy, acknowledging that lineage is a social and historical relationship as well as a biological connection, and that legal systems can validate ancestry through diverse evidentiary strategies.

The next section develops this idea further by mapping the evidentiary hierarchy in a comparative matrix. It outlines practical options that states could adopt to widen access to nationality while maintaining legal certainty.

8. Comparative Evidentiary Matrix and Discussion

The comparative findings can be organised into an evidentiary matrix that highlights how each region balances certainty, accessibility, and fairness. The matrix builds on the hierarchy introduced in Figure 2 and shows that while the types of evidence appear similar across systems, their legal weight and accessibility differ significantly. The purpose is not to rank jurisdictions but to expose the logic through which citizenship by descent is verified and the consequences this logic produces for individuals navigating multiple legal environments. This matrix provides a structured way to compare how documentary, biological, testimonial, and presumptive forms of evidence function within different administrative and historical contexts, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative evidentiary matrix for descent-based nationality.

This matrix shows that all regions recognise similar kinds of evidence, but the strength of each type depends on institutional culture and the level of administrative development. Europe gives documentary evidence an almost sacred authority. Africa works with the same formal categories but within a setting where paperwork is uneven and oral knowledge remains central. North America moves further toward scientific certainty by combining documents with genetic and digital verification. These differences also demonstrate how each region expresses genealogy in a distinct way. Europe treats ancestry as something that becomes real when the archive records it. Africa treats ancestry as lived and remembered through family and community. North America treats ancestry as something that can be measured through science and digital records. This makes it possible to connect the analysis directly to genealogy rather than simply describing regional procedures.

These contrasts show that evidentiary hierarchies are shaped not only by the written law but also by administrative conditions that determine which forms of proof are viewed as trustworthy. Across the regions, one theme recurs. Certainty is created through legal procedure rather than found in nature. States decide which forms of proof count, and this decision becomes the foundation for recognising descent. When the administrative system is strong, the state trusts documents. When the administrative system is weaker, the state relies on external models. Manby (2019) explains that this is why many African states adopt European documentation standards, often following pressure from migration agreements and international partners. Dumbrava (2014) shows that North American practices influence biometric and genetic projects in other parts of the world. This movement of evidentiary ideas across borders shows that genealogy is increasingly filtered through global administrative expectations rather than local social understandings.

At the same time, the matrix shows that inclusion and certainty do not have to conflict. Kaneko-Iwase (2021) and Dumbrava (2014) argue that presumptions and layered verification can maintain legal reliability while widening access. Examples include retrospective registration programmes, acceptance of several supporting affidavits, and the selective use of DNA testing in complex cases. Manby (2016) proposes combining documentary evidence with community validation to capture genealogical knowledge that formal archives cannot preserve. These approaches offer flexibility without weakening the evidentiary structure. They recognise that descent is lived and remembered before it becomes a legal fact and that the evidentiary system should reflect this reality.

The discussion leads to an important insight. Nationality law is not only about descent. It is also about the ideas that states hold about evidence. Each region imagines belonging through its preferred form of proof, whether archival, scientific, or testimonial. When these evidentiary models travel across borders, they reshape not only legal decisions but also how people understand kinship. In this sense, the global spread of evidentiary standards turns citizenship into something that must be demonstrated through concrete proof. This clarifies that the evolution in nationality law is located in the practical systems that govern proof rather than in the legal meaning of citizenship itself.

The next section brings these ideas together. It presents the main findings, restates the comparative argument, and offers practical reforms that respect the need for credible evidence and the right to belong.

9. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study set out to understand how states define belonging through descent and how their ways of proving ancestry travel across borders. The comparison of Europe, Africa, and North America shows that nationality by descent is shaped not only by law but by the kinds of evidence a state chooses to believe. Citizenship is no longer just a political or legal question. It has become an evidentiary one. This shift reveals how modern nationality systems construct identity through the forms of proof they privilege, and how these forms determine which genealogies become legally visible.

In Europe, descent is embedded in bureaucracy. The written record remains the ultimate proof. Birth certificates, registers, and official translations stand as symbols of certainty. Even when DNA testing appears, it confirms rather than challenges the state’s faith in documentation. In this system, citizenship exists once it is written down and verified. Belonging becomes inseparable from the archive, and the archive becomes the guardian of national membership. This creates a model in which genealogy is legally recognised only when it passes through administrative instruments that translate family history into documentary form.

In Africa, the situation is more layered. Descent is often clear within communities but difficult to prove through the state. People know who belongs, yet the law asks them to show papers that may never have existed. Many citizens are therefore visible to their neighbours but invisible to their governments. The law of descent, which should be inclusive, becomes exclusive when it demands proof shaped by foreign administrative traditions. This exposes a deeper genealogical tension, where ancestral knowledge held in oral tradition does not align with the evidentiary expectations inherited from colonial systems.

Yet, the region also shows that the gap between community genealogy and state genealogy can be narrowed when authorities recognise layered affidavits, community attestations, and retrospective registration as credible components of proof.

North America adds another dimension. Here, the search for certainty has shifted from archives to biology. DNA testing and digital databases have become part of citizenship administration. They resolve disputes that once depended on documents or testimony, but they also narrow the meaning of family by equating kinship with genetics. This biological turn promises precision but risks reducing belonging to a measurable fact, leaving little room for the social and relational dimensions of ancestry. It also shows how legal systems can redefine genealogy by privileging biological evidence over the narratives through which families understand themselves.

Across the regions, one pattern is clear. Modern nationality law has turned evidence into the foundation of belonging. Documents and DNA have become global markers of legitimacy, while oral and communal proofs have been pushed to the margins. The standards of the most bureaucratic states now influence how the rest of the world understands credibility. Migrants and diasporas must therefore learn to navigate an evidentiary landscape shaped by systems far from their own histories (Zetter 2015). The result is a transnational hierarchy of proof, where the ability to demonstrate identity depends on proximity to archives, technology, and administrative continuity. This confirms that the evolution is not in the law itself, but in the practices through which states construct credibility and authenticate lineage.

The lessons that emerge from this comparison are practical. States can preserve legal certainty without producing unjust exclusion if they rethink how proof functions. Evidence should not take the form of a single gateway but of a spectrum. When several modest proofs such as documents, sworn statements, and community attestations point in the same direction, they can together meet the threshold of credibility. Retrospective registration can help document older generations and prevent exclusion that arises from historical gaps in record-keeping. This includes the national birth registration catch-up campaigns carried out in Ghana and Kenya with support from UNICEF, the civil documentation drives used in South Africa to regularise long-standing residents, and local government exercises in Nigeria where authorities reconstruct parentage and age through combined administrative investigation and community testimony. These initiatives show that states can expand documentary coverage responsibly when procedures are monitored, and evidentiary safeguards remain in place. International organisations can support this effort by promoting flexible verification models rather than exporting one narrow template of documentation. In practical terms, these flexible models refer to procedures that allow authorities to combine several modest forms of proof when a single definitive document is missing. They are already used in birth registration initiatives supported by UNICEF, UNHCR, and the European Union, where layered affidavits, corroborated witness statements, retrospective registration, and community validation are accepted as part of the evidentiary package. The Council of Europe’s current work on civil status documentation also promotes similar approaches, encouraging member states to adopt verification pathways that recognise both formal records and alternative sources of reliable information. These models are designed to improve access without weakening evidentiary standards, especially in contexts where gaps in archival history make strict documentation impossible. These measures show that accuracy and fairness are compatible when states recognise that genealogical truth is often dispersed across multiple forms of evidence and not contained in a single archival record.

The deeper message is that nationality law should rest on trust as much as verification. Citizenship by descent is not simply an inheritance of blood. It is a relationship of recognition. In this context, recognition refers specifically to the state’s acceptance of a parent–child link or of a civil status that establishes the legal basis for transmitting nationality. The point is that descent becomes legally effective only when the state acknowledges the relationship through an evidentiary process, whether through documents, testimony, or biological proof.

When the law treats evidence as living knowledge rather than a fixed object, it can remain certain without becoming rigid. To belong should not depend solely on what is written or tested but also on what is known and remembered. Recognition gains legitimacy when it reflects the lived realities of families as well as the administrative needs of the state. In this sense, the future of nationality law depends on the willingness of states to engage with genealogy as both historical memory and legal fact.

Future research should examine closely how digital identity systems and artificial intelligence will shape the next generation of citizenship procedures. These tools may deepen exclusion, or they may broaden recognition. The outcome will depend on whether states remember that every certificate, every record, and every genetic report tells a human story. The challenge is to ensure that in the pursuit of certainty, the law does not lose sight of humanity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B.A.; methodology, O.B.A.; formal analysis, O.B.A.; investigation, O.B.A.; resources, O.B.A.; data curation, O.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B.A., O.M.O. and O.T.O.; writ-ing—review and editing, O.B.A., O.M.O. and O.T.O.; visualization, O.M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Rev. ed. London: Verso. First published 1983. Available online: https://nationalismstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Imagined-Communities-Reflections-on-the-Origin-and-Spread-of-Nationalism-by-Benedict-Anderson-z-lib.org_.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Bauböck, Rainer. 2021. Dual Citizenship and Naturalisation: Global, Comparative and Normative Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu, O. J. 2016. Citizenship in Nigeria: Examination of the Procedure of Acquiring Citizenship. Benin City: Benson Idahosa University Law Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Dumbrava, Costica. 2014. Nationality, Citizenship and Belonging: The Boundaries of Political Membership. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Flaim, Amanda. 2015. No Land’s Man: Sovereignty, Legal Status, and the Production of Statelessness Among Highlanders in Northern Thailand. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galen-Murray, B. A., and O. Schmidtke. 2016. Still German: The Case of Aussiedler and the Framing of German National Identity Through Citizenship Law. Victoria: University of Victoria Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joppke, Christian., and Roshenhek Zeev. 2001. Ethnic-priority immigration in Israel and Germany: Resilience versus demise. Comparative Political Studies 34: 387–416. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko-Iwase, Mai. 2021. Nationality, Statelessness, Family Relationships, Documentation and Foundlings. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kapianga, Kelly. 2020. Report on Citizenship Law: Zambia. Florence: GLOBALCIT, European University Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Manby, Bronwen. 2016. Citizenship Law in Africa: A Comparative Study, 3rd ed. New York: Open Society Foundations. [Google Scholar]

- Manby, Bronwen. 2019. Citizenship Law as the Foundation for Political Participation in Africa. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manby, Bronwen. 2020. Nationality and Statelessness in Africa. Nairobi: UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, Samah Hadi, and Ahlam Jabbar Mohsen. 2025. Legal effects of proving lineage on nationality: A comparative study. Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review 5: e05566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oucho, John O. 2017. Migration and Citizenship in Sub-Saharan Africa: Regional Trends and Legal Responses. Nairobi: African Migration Centre Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pallaver, Günther, and Guido Denicolò. 2021. Dual Citizenship in Italy: An Ambivalent and Contradictory Issue. Trento: University of Trento Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiei, Mohammad Taqi. 2012. A legal jurisprudential deliberation on lineage and descent in Islamic law. International Journal of Family Studies 5: 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Seng, Jana M. 2001. Cambodian nationality law and the repatriation of convicted aliens under the illegal immigration act. Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal 10: 485–526. [Google Scholar]

- Thwaites, Rayner. 2022. Proof of foreign nationality and citizenship deprivation: The British courts’ approach. The Modern Law Review 85: 801–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucco, Daniela. 2023. Making Italians without Italy: Sociology of non-state citizenship claims. Revue d’Études Comparatives Est-Ouest 54: 203–24. [Google Scholar]

- Voutira, Eftihia. 2011. The right to return and the meaning of home: A post-Soviet Greek diaspora becoming European. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 18: 393–416. [Google Scholar]

- Wautelet, Patrick. 2011. Comparative Aspects of Nationality Law: Selected Questions. Liège: Université de Liège. [Google Scholar]

- Yapo, S. 2020. Dual Citizenship in the Mirror: Reflections on Post-Colonial Identity and Legal Belonging. Paris: Sorbonne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zambon, Kate. 2021. Integration and the cultural politics of migration in the new German public. European Journal of Cultural Studies 24: 995–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Zetter, Roger. 2015. Protection in Crisis: Understanding the Legal and Political Roots of Statelessness. Geneva: UNHCR Policy Series. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, R. 2021. Constitutionalising Citizenship: Identity, Rights and Belonging in Comparative Perspective. Oxford: Hart Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zincone, G., and T. Caponio. 2021. Migrants and Their Children in Europe: Inclusion, Exclusion, and Evidence. Milano: FrancoAngeli. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.