Abstract

The study of coopetition has been evolving with rapid growth in the number of academic publications in this field. A number of literature reviews have been published focusing on nature, antecedents of coopetition and future perspectives of its implementation. Coopetition is proved to be beneficial for joint investments and Research and development (R&D) projects, and yet competitive games take place in the global markets that may lead to safety hazards. There are few studies that investigate possible perspectives of coopetition strategy for solutions in safety and security, and therefore considering the global tendencies objective, necessity arises for a more detailed study of it. The analysis begins by identifying over 600 published studies where the terms “coopetition”, “safety”, “security” were used. Using rigorous bibliometric tools, established and emergent research clusters were identified, as well as the most influential studies, the most contributing authors and topical areas for further investigations. The systematic combination of quantitative and qualitative analytical tools helps to identify the potential directions for future research. By combining bibliometric analysis and content analysis, the main perspective areas for coopetition implementation towards safety and security were identified.

1. Introduction

At the end of 2018, the production of the main competitors, Airbus and Boeing, increased, which in combination with lower fuel prices and favorable conditions in financial markets should have led to strong aircraft supply in the market. It was expected that production rates of both Boeing and Airbus as they were rising, will bring more jets with lower costs.

But two fatal jet crashes in less than six months (29 October 2018 and 10 March 2019), both Boeing 737 MAX 8, have alarmed aviation and safety experts around the world. As the investigation is still in a process, for now, preliminary evidence named automated system designed to help the plane avoid stalling as one of the possible contributors to the crash [1,2]. The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) [1] was created to avoid of nosediving, and yet precisely with the same system pilots were fighting in their attempts to stabilize the planes before the crashes in both cases [2]. According to Campbell’s report, pilots had problems overcoming a malfunction in the safety software that forced the nose of the planes lower before they crashed [3].

In response, numerous aviation lessors and airlines slowed down and then stopped ordering 737 MAX, and aviation authorities grounded this brand. According to Reuters, Boeing’s earnings fell 21% in the first three months of the 2019 year [4]. As experts said, there could be more than $600 billion in orders at risk of cancellation [5], and according to Reuters, the number of preorders of 737 MAX was zero in April 2019 [6].

The Boeing 737, which was best-selling model in the commercial aviation sector, became a cause of the crisis of all aviation industry. Not only Boeing, but all airlines in a supply chain were damaged. The groundings, delayed deliveries of new Max planes, uncertainty over the ability of the planes to be at service, and demand drop led airlines to reschedule and cancel months of flights, and therefore to profit loss. The airlines around the world are united now in a search for compensations from Boeing for delayed deliveries, order replacement, passengers trust lost and so on [7].

These tragedies and their consequences turned the attention towards the complexity of the navigation systems, safety issues, the interdependence of the players in the market, and the nature of competitive pressure.

The story of Boeing Max can be named as a history of human errors, or the result of underestimated complexity of the software, but we do believe that the nature of competition that created in-market pressure leads to opportunistic behavior of the players, and thus, to mistakes in production, software development, personnel training and deadly combinations of all abovementioned.

These events forced us to search the possible trajectories of the further research in a sphere of safety and security towards human-friendly solutions.

Coopetition as a strategic management theory was first formulated by Brandenburger and Nalebuff [8], then drew the attention of strategists all around the world and was developed and enriched by many researchers. Among all we should mention the studies that were done by Padula, Diguardo and Dagnino [9,10], Czakon [11], Bengtsson and Kock [12,13], Le Roy [14,15] and his colleagues, Chiambaretto and Fernandez [16,17]. We should mention the studies that contribute to understanding of cooperative human interactions [18,19] that may be considered as a part of coopetitive behavior. Studies on coopetition vary depending on the industry or economy brunch, for instance, we should mention the research that determines the factors of coopetitive behavior [20] in oil and gas distribution industry, and a study on critical success factors that was done later for the same industry [21]. In Ukraine, the studies on coopetition are rare and most dynamic sectors, namely, financial institutions development and banking, attract the focus of researchers who found the joint investments [22] and venture networks [23] promising for the collaboration within the network of business entities and institutions.

We may assume that excessive competition in time and resources may lead to erroneous decisions in design and production, and therefore to safety hazards. The mentioned events forced us to investigate if there is a link between research in a sphere of coopetition and safety research that may bring mutual benefits for both areas.

This paper is aimed to prove the necessity of expansion of coopetition into other areas of research, such as R&D in security and safety. This conviction is based on our presumptions about coopetition as a promising emerging trend in research and strategy development. Coopetition became multidisciplinary, continued to expand and reached into the areas of safety and security which, as we believe, are the next generation of the coopetition-related investigations.

The main research question is if coopetition expands, is it visible in the trends of publishing and findings? A sub-question is, if coopetition expands, and offers innovative costs-effective decisions for mutual benefits of partners, is it possible to track the coopetition expansion towards research area related to safety & security?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The assumptions of the link between safety, security and coopetition are presented in Section 2, followed by bibliometric analysis that revealed the research trends in Section 3. Section 4 provides the discussion part of the findings, before concluding the main results in Section 5.

2. Through Coopetition Towards Safety & Security

Coopetition is seen as a situation when firms cooperate and compete simultaneously [24]. Research on coopetition can be classified depending on the motives, likelihood, interaction, process, and outcome of coopetition, as was done by Bengtsson and Kock [13]. Another remarkable overview of coopetition research presented by Dorn and her colleagues classifies the research depending on its phase model, such as antecedents, initiation phase, managing & shaping phase, evaluation phase [25]. Despite the large number of publications on this phenomenon, the nature of coopetition is yet unexplored. Therefore, the conceptualization of coopetition takes place in academic literature that can be described by several streams. Supporters of one of the approaches understand coopetition as a process, or the series of consistent actions taken by competitors to establish rules on how to compete and cooperate in order to achieve current agreements [26,27]. Another stream is a perception of coopetition as a phenomenon, or an event which appeared in the society or economy beyond established rules and norms [8,10]. The third stream is based on the assumption that coopetition is a behavioral pattern formed in response to global hypercompetition [28]. We should mention one more powerful stream that considers coopetition as a paradox, or a set of interrelations that has logical contradiction [17,29,30].

In our research, we assume coopetition as a system of paradoxical (cooperative and competitive simultaneously) multilevel relationships between proactive economic entities, which choose partners consciously in order to create shared value (in the external environment) and new competencies (in the internal environments) regardless of background and time range.

At the same time, there is evidence that coopetition is a more attractive option for the partners who had been involved in some joint activities, have a common history of interactions and positive previous experience [31]. On the other hand, negative previous experience can become a barrier to partnership [32].

With respect to previous interactions, the competition between Boeing and Airbus has deep roots in 90-ties and can be characterized as a duopoly, since these two players own most of the market for narrow-body passenger jets.

The detailed case of Boeing 733 crashes is presented in Campbell [3], but some key points of that study should be mentioned. Both manufacturers compete in the market where cost-effective solutions for airlines, especially in terms of fuel efficiency, are in demand. Until 2010, there were two main competitive products in a race, Boeing 737NG and Airbus A320 (launched in 1997 and 1988, respectively), but in 2010, the situation escalated with the appearance of A320neo, presented by Airbus as “new engine option” [3], which burns 6 per cent less fuel than 737NG. It led to the tremendous sales increase, and in a week, Airbus sold more orders than Being 737s for the entire 2010 year.

In response to this threat, Boeing launched a fourth-generation 737, and completed it in record time. The 737 Max was a “stopgap measure” [3]. Airbus’s actions made Boeing abandon the idea to develop a brand-new design for a jet and modify the 737 instead. That decision was obviously based on saving time and engineering work. That became a source of the forthcoming problems: the engineers were forced to overcome challenges of updating old designs in a very short time. There were limitations of certifications using, or rather, incentives for manufacturers to design aircraft that will use a common type of certifications covering every detail in design development. To beat Airbus, it was decided to shorten the cycle of production to six years, the shortest cycle among all Boeings launched (in comparison: 7 years for Boeing 777, almost 8 years for Boeing 787). In two years, Boeing announced that Max would be 8 per cent more fuel-effective than A320neo, and later after certification, it was stated that pilots with experience flying a 737 can switch to Max after 2.5 h computer-based training.

According to Campbell’s report [3], there were errors that repeatedly appeared in a process of delivering blueprints to software developers, there was no room for innovative decisions while the old analogue should be adjusted to digital format to keep Max within the certificate constraints. New engines that were created to solve the problem of fuel usage but at the same time brought aerodynamic problems. To keep the certificate, and avoid numerous calibrations of new engines, software was created to compensate the regulatory and aerodynamic problems.

The problem was that Boeing did not inform pilots about MCAS, and as it was later reported, the training for pilots was done via IPads, MCAS was absent in FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) review, as well as absent in training guidelines.

Competitive pressure to build such a jet was huge. If Airbus won the contract, Boeing would lose 35$ billon over the next few decades [10], and in a process of series of decisions, MCAS implementation was offered as a cost-effective solution to overcome the competitor in the short term. This solution was adaptive, not innovative, not transparent and led Boeing to crucial safety risks. We will not speculate further what would happen if sensors would have no malfunctions, or software would be designed properly, or pilots would be trained in time and informed well. But what if competitive pressure would not be perceived as huge, and initial decision to design entire new innovative jets would have taken place?

In our view, one of the biggest challenges in global markets is the reduction of competitive pressure in order to provide innovative and human-friendly solutions. Under competitive pressure, the decisions may be made towards short-term benefits, as we may see from the case of Boeing.

We should mention an interesting fact that both Boeing and Airbus have strong connections and partner relations with their numerous suppliers and clients (airlines and lessors). At the same time the coopetitive interactions between these two players are not that obvious. In the light of recent events, the decision-makers should consider coopetition as an optional strategy that may bring safe, cost-effective innovations to the industry.

Besides the abovementioned benefits, coopetition is proved to be helpful in shrinking product life cycles, risk sharing and increasing market power [33], synergy in joint R&D [34] and increasing capacity to innovate [35,36], and improving market performance [37]. Many overviews were done in a sphere of coopetition [13,25,38], but they were mostly concentrated on coopetition itself as a new emerging field. The paradoxical nature of coopetition creates cognitive dissonance among the managers and authorities, but as the positive impact of the coopetition spreads across the fields due to the efforts of the scholars and practitioners, a coopetitive framework will be more and more acceptable. If there are benefits in joint R&D, which are more innovative and more cost-effective under coopetition, there are should be a trend of expansion of coopetition ideas to other areas.

3. Identification of Trends in Research and Perspectives of Coopetition for Safety & Security

The literature review is aimed to identify the interlinks between main terms as markers of core academic investigations, and knowledge gaps as a beacon for further research. The emerging trends can be found through the published statistics and in a process of terms such as cluster analysis. A structured literature review was employed using a five-step methodology to collect data about and comprehensively evaluate: (a) the most influential studies, (b) the most seminal authors and, (c) topical areas of research. This process mirrors similar work by Fahimnia and her co-authors [39] in the sphere of green supply management. This methodology is proven to be helpful for rigorous literature review and was chosen for the current research.

3.1. Defining the Appropriate Search Terms

The keywords used for data collection include “Coopetition”, “Safety”, “Security” and since coopetition can be defined as an integration of cooperation and competition simultaneously, we include a combination of “Competition” and “Cooperation” in a search. We cannot argue that both terms cover the phenomenon completely. At the same time, since coopetition emerged from the union of cooperation & competition, and yet the number of papers differ, it shows that there is a gap in understanding of coopetition phenomenon and its benefits for the industry.

3.2. Initial Search Results

Using the “title, abstract, keywords" field of search in the Scopus database, different outcomes in terms of the number of papers (conference papers, books, chapters and articles in the journals) were identified for search items. The combination of the terms allowed us to gain an understanding of the evolution of the field of study (please see Table 1), to reveal current and predict emerging of the new fields of research.

Table 1.

The search results (SCOPUS Database) for several combinations of keywords, for the whole period that ends in 2018.

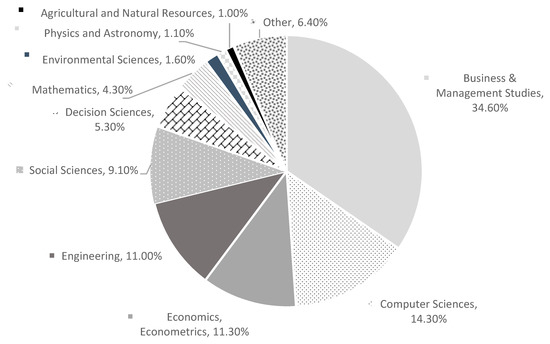

The earliest papers in the coopetition field were done in the 1990s and initially were in a field of digital services. We should mention one of the earliest papers that was devoted to client-server design [40], and seminal work of Branderburger and Nalebuff that was inspired by the rapid development of Silicone Valley [8]. But later, the field was dominated by the researchers from Business and Management Studies (please see the Figure 1) and Computer Sciences were shifted to the second place among other subject areas.

Figure 1.

Papers in the field of “coopetition” classified by field (Scopus Database).

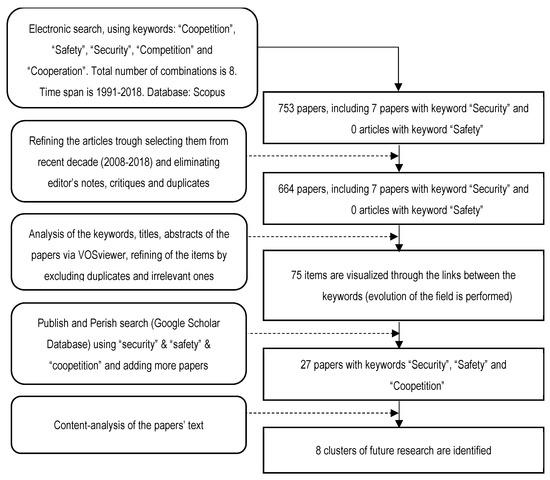

Though the beginning of the debates on coopetition was in 90-ties, the main rapid growth is observed lately, and that is why, considering the increasing publishing trends (see Figure 2) and dominating subject areas, the initial data search was refined to the papers on coopetition in a period of 2008–2018, and limited to the papers, conference materials, and books, excluding editors’ notes, etc. The total number of papers was 664. These search results were stored in RIS format that includes all information needed for further bibliometric analysis (including title, authors names, their affiliations, abstracts, keywords, references and so on). The preliminary results revealed few papers in security and a lack of papers on safety that are related to coopetition in the Scopus Database, and therefore the sample was modified to include the papers from other databases through the Publish & Perish tool. The scheme of the research and review process is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Systematic process of research.

3.3. Data Statistics and Bibliometric Analysis

Considering the essence of bibliometric analysis, in this study several techniques were adopted, for instance used by abovementioned scientists [39], and the methodology of research is designed as follows: (1) the data were structured and analyzed in order to reveal the publishing trends, (2) citation analysis (full and fractional counting) was done to reveal the most contributing authors in the field; (3) network analysis was accomplished to prove the link between coopetition and safety & security areas of research; (4) an advanced search to expand the paper sample was done and (5) qualitative content analysis to verify the interconnections between areas was provided (please see Figure 2).

Among existing software packages used for bibliometric analysis, Publish and Perish, BibExcel, and VOSviewer were selected. Publish and Perish was chosen due to its scale and scope, and ability to provide the search results in other formats. BibExcel was chosen because of usability, adjustment for any format of input data (including Scopus), comparability with other programs, such as VOSviewer, etc. VOSviewer is proven to be an effective visualization tool [41] for performing keywords and terms used for transforming data into a comprehensive model for further analysis. The data on papers (sample is 664) were put into RIS format containing all needed bibliographic information.

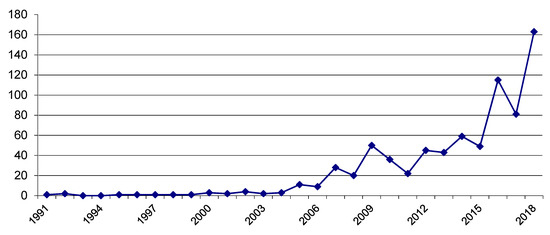

The increasing numbers of papers published, presented in Figure 3, let us assume that the field of research is in an early growth stage, though the first paper was submitted in 1991.

Figure 3.

Publishing trends (number of papers) in the area of “coopetition” (using Scopus Database).

The initial data analysis shows the most contributing authors in this field (please see Table 2).

Table 2.

The top 10 contributing authors in the area of coopetition (Scopus Database), full counting.

The chosen sample of 664 papers was analyzed, and it was found that journals that published more than 12% of all the papers in recent 10 years are Industrial Marketing Management (43 papers), International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business (11), International Journal of Technology Management (11), Review of Managerial Science (11), International Studies of Management and Organization (8).

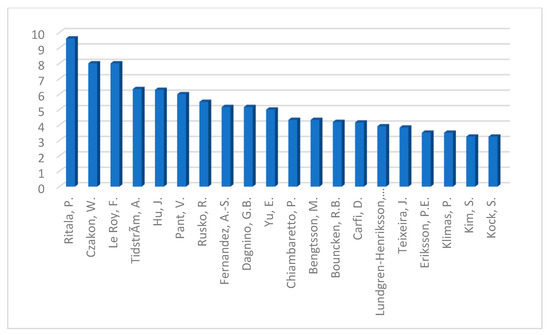

The concept of comparison of paper numbers to understand the input of authors into the field makes sense in the context of the calculation of bibliometric indicators. Full counting means that papers are counted as equal for the number of authors of the publication, as presented in Table 2. Fractional counting means that a co-authored publication is assigned fractionally to each of the coauthors, with the overall weight of the publication being equal to one. This methodology offered by experts in bibliometric analysis proved that fractional counting is more valid comparatively to full counting [42]. The data on fractional counting for each author were extracted via Bibexcel and presented the main contributors in the area of coopetition research as follows (please see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The top 20 contributing authors in the area of coopetition (Scopus Database), fractional counting (constructed via BibExcel), N = 664 papers.

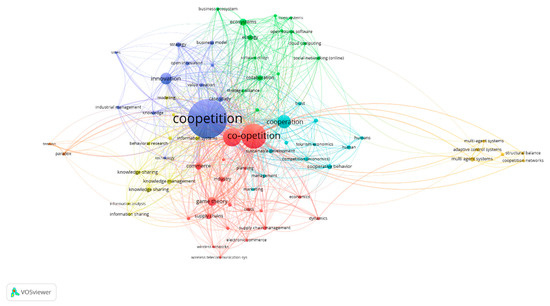

3.4. Network Analysis and its Visualization

Visualization of research network may be accomplished with the help of VOSviewer, the program that has its own clustering technique [43], and due to this, two levels of analysis were performed as in Figure 5—clustering of the publications, and citation relations. As shown (see Figure 5), the distance between the clusters approximately indicates the relatedness of the clusters in terms of citations. As we may see, clusters that are located close to each other tend to be strongly related in terms of citations, and those clusters which are located further away from each other tend to be less strongly related.

Figure 5.

VOSviewer visualization of the TOP-18 most cited authors in the area of coopetition research (1.6.10 version), N = 664 papers, where 5 clusters or scientific schools are identified (the color means the same cluster, where authors cited each other and are strongly related).

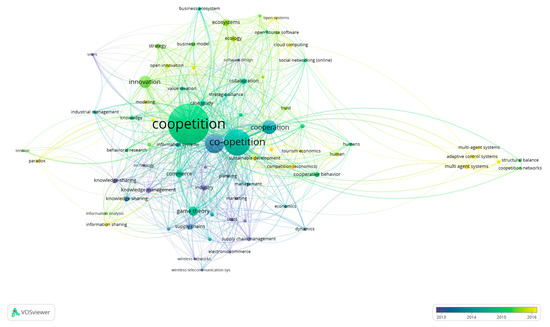

To reveal new trends and tendencies and, most important, further promising directions of the research, it is necessary to construct cluster analysis for the keywords, using the abstracts of papers extracted from the Scopus Database. VOSviewer is proven to be an effective tool for providing keywords visualization [41] which gives the analyst understanding of interconnections between main terms in a field of research. Using the abstracts of the chosen papers, the network of terms was generated by using a unique clustering technique offered via this program [43]. 80 keywords (frequency > 6) was identified which were refined to 75 by excluding duplicates and irrelevant for this analysis (i.e., “research”, “article” etc.). Therefore, 75 items were organized into 7 clusters, as showed below (please, see Figure 5 and Appendix A). It should be noted that the occurrence of the keyword “coopetition” is the highest and equals 323, the term “co-opetition” introduced by Branderburger and Nalebuff [8] is still popular, and its occurrence is 162, “competition” remains a widespread term in chosen papers as well as “cooperation” (100 and 63 accordingly). The top list is concluded by “innovation” (53 times) and “game theory” (33 times). The size of the circles reflects the occurrence of using the terms. Other items appeared in the sample less than 20 and more than 6 times. For chosen terms, network visualization (see Appendix A), overlay visualization (Figure 6) and density visualization were performed via VOSviewer. The overlay visualization is chosen as a more valid tool for verification of the recent trends in the academic field, as soon as it allows us to classify the items using timescale. The items are colored differently based on year of publication (average for the cluster). In our case, those terms that appeared recently (average year of publication is 2016) are more yellow. A color bar shown in the corner has the same explanation; the scores of the items are determined by the time since publication.

Figure 6.

Overlay visualization of most frequent terms (Constructed via VOSViewer v.1.6.10 for the sample N = 664, f (frequency) > 6), where the score of the item is time since publication.

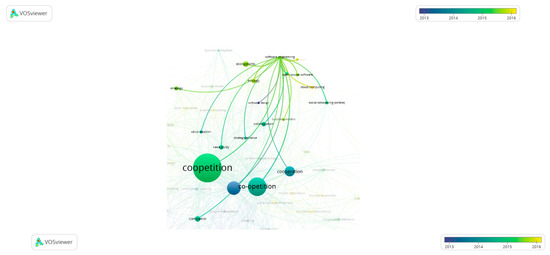

Thus, the results of data performance are fruitful in terms of confirming the promising direction of research. At the beginning of the paper we assumed that security and safety issues can be a new area of coopetition activity. The Boeing case presented a striking example of software development problems. Now the intuitive suggestions are proved by data. From Figure 7 we may see that “software engineering” is closely related to “open systems”, “open source software”, “ecosystems”, “cloud computing”, “social networking (online)”, and which is significant for our research–related to “case study”, “value creation”, “collaboration”, “strategic alliances”, “cooperation, “coopetition” and “commerce”. The same detailed analysis we can do for “information sharing” as one of the key components of security software development, and the recent publications performed the linkage between “information sharing” and such terms as “information analysis”, “knowledge-sharing”, “knowledge management”, “information management”, “behavioral research”, “game theory”, “decision making” and “supply chains”. The phenomenon of information sharing is quite new for coopetition research, and we may say that different components of it are a focus of attention of the researchers. These findings became an insight for the next stage of research–advanced search via Publish and Perish for recent findings using the combination of the mentioned keywords.

Figure 7.

The fragment of overlay visualization for the term “software engineering”.

3.5. Advanced Search and Content Analysis

The initial data of search results using “safety” and “security” as the keywords in coopetition-related studies yielded few papers. To refine the number of papers for the presentable sample for further in-depth screening, an advanced search via Publish and Perish (Google Scholar Database) was performed using the keywords “coopetition”, “safety”, “security”. Among the results (around 1000 sources), relevant papers were selected (not books, conference papers or editors’ notes) according to these main criteria: (1) high citation index, (2) abstract, title and keywords must be in accordance with the relevance of the search. The search results ended with data where papers were different in terms of citation (from 812 citations per paper to 0), which can be divided as follows: the first 13 results had more than 100 citations, the second cohort of 15 papers had a citation index more than 50, and so on. After eliminating books, conference papers, editors’ notes and irrelevant studies (by screening the paper), the decision was made to select papers with a citation number ≥40 per paper. As a result, the outcome was 20 papers (the maximum number of citations is 812 and the minimum is 40 citations per paper), which, is twice as many as initial data results from Scopus database. It made possible to compare papers from Google Scholar and Scopus databases in terms of keywords using, research findings and new areas of research that can be considered as perspective for further investigations in the coopetition field. In total, the final sample is 27 papers, and in our opinion, it is helpful to confirm the idea about the link between coopetition, safety, and security aspects.

Firstly, we should mention that high citation number as a criterion was chosen (instead of the high ranking of authors, for instance) as an indicator of the dissemination of the results and, therefore, the impact of the publications. As it was observed [44], the citation index serves as an incentive for data sharing and encourages researchers to present their results among scholars.

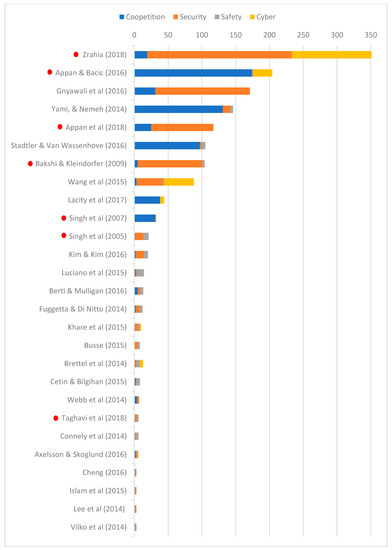

Secondly, in a process of analysis, it was revealed that the keywords “cybersecurity” or just “cyber” appeared many times in several papers. It inspired us to include “cyber” as a keyword for further analysis. The full manual counting of keyword usage resulted in a performance system of papers as follows (see Figure 6). This simple technique enables us to draw conclusions about the relevance of the papers to overlapped areas of the research, to track the appearance of the keywords and intensity of their use over time. Thus, despite the fact that the period of analysis was the last 10 years, the most relevant papers have started to appear since 2014, except for the paper by Singh et al., published in 2007 [45], and its predecessor by Singh and Atrey—in 2005 [46]. The intensity of keywords and awareness of the interests in the mentioned area raised as well. However, we cannot use this approach to prove the importance of certain papers in contrast to others. Moreover, our observations suggest that the intensity of the use of keywords indicates a specific, niche study. Multidisciplinary articles tend to affect many aspects and different areas of research, and therefore the number of keywords in such articles is lower compared with niche ones.

However, the distribution of keywords presented in Figure 8 allows us to say that a snapshot (7 initial papers from the Scopus database, marked with red dots) gives similar results as well as the final sample, which means that few relevant papers are sufficient for making a conclusion about the future challenges in multidisciplinary research.

Figure 8.

Keyword occurrence (full counting) for the chosen papers (N = 27) in a field of research, where red dots mark the papers from the Scopus Database. The ranking of papers is made according to the frequency of usage of keywords “coopetition”, “safety”, “security” and “cyber”.

However, to provide a meaningful contextual study of the papers to verify the interconnections between coopetition, safety, and security issues and their promises for further interdisciplinary research, a qualitative approach was chosen. We revealed that the Google Scholar Database offers papers as relevant if the keywords are presented in the reference list. Only reading the paper, its abstract, main findings, and contributions, and analysis of its content may give an understanding of its value for further study.

“Coopetition” as a keyword was assumed as a leading term for revealing related studies, and content-analysis in detail was performed for papers listed as follows (following the ranking presented in Figure 6).

Thus, starting with [47] we should note in particular the scale and scope of the research, in which authors analyzed 131 records from 57 companies and revealed that there is a positive association between threat sharing relationships and innovation level, and the cybersecurity threat-intelligence sharing relationships are characterized by coopetition between loosely integrated complementary solutions. In other words, coopetition is much easier to be established between partners with complementary resources, and cybersecurity can be an area of implementation of coopetition strategy.

In the study [48] it was proven for publicly listed cyber-security and IT firms that participate in sharing IT security-related information have higher profitability and lower costs than non-participating IT firms (in short and in a long-run term). Later, the same team of researchers argued that there are few studies on how IT security strategy impacts firm performance and more investigations, in particular, theory-based empirical research, are needed, especially when the companies continue to engage in “various forms of cooperation, alliances and coopetition” [49].

The paper published by a research team united several Coopetition Schools [50] on the investigation of the coopetition capability generalized the ideas about security as a driver for knowledge sharing. According to the researchers, a “greater sense of security leads to greater willingness to share knowledge (and) higher creativity” [50] in a process of coopetitive interactions.

It is interesting that not all types of coopetition pursue innovation, as was proved in [51]. The same paper presented new areas of research that need the attention of the scholars, such as security-safety standards development for coopetition alliances. A case study in the mentioned paper revealed that at the competencies level, there is a need to create new services in the sphere of security and media platforms “in order to meet mid-term operator’s need” [51]. Authors presented their view of telecommunication sector development and emphasized that topics related to end-to-end services like e-health, e-security, digital homes, digital enterprises and digital cities are urgent for further implementation of coopetition principles.

An empirical study on the coopetition paradox, which was mentioned earlier [30] presented some aspects of behavioral responses that were related to safety and security issues. During the survey the responders admitted that safety and security are the most important in the process of sharing knowledge in a process of collaboration. Therefore, to engage participants in the innovation process it is necessary to develop a balanced system of knowledge sharing and retention.

In one of the earliest papers, the superiority of coopetition over competition was proved in the context of managing supply chain security [52], which became an area of active investments and R&D for many types of the industries. The joint investments approach performed by supply chain suppliers leads to chain security and resilience, as was argued in the same study [52].

The latest advancements of cyber-physical systems (CBS) in manufacturing and their future potential became a focus in [53]. CBS have been implemented actively in many spheres, such as transportation, smart homes, robotic surgery, aviation, infrastructure and defense, where security is one of the main challenges. Security is closely related to safety, according to the authors [53], and coopetition may be cater for further development for CBS, along with other initiatives like Advanced Manufacturing Partnership 2.0 [54], Industry 4.0 [55], Factory of the Future [56], etc.

An investigation on promising areas for future research for sourcing of business process and information technology services was done in [57] and it was argued that cybersecurity is one of the biggest challenges that organizations and individuals have to face and yet is one of the most unexplored; therefore, authors think that there are at least two aspects that deserve attention [57]: competences loss is the first. For instance, the problem of sharing and losing some critical information can be crucial for business, as a company may lose competencies in value chain development when constantly using outsourced IT-services. One more aspect is important for outsourcing contracts–they should be articulated in terms of ensuring security and compliance. We agree that not every company can afford its own IT service development, and because of the diversity of IT-services in the market, to develop own IT-solutions is not cost-effective. Following offered logic, we may add that is why cybersecurity and information security management coupled with project management can shape the organizational architecture and may influence significantly the choice of the partners for collaboration and coopetitive R&D projects.

The earliest study in the area which combines coopetitive interactions and security in the multi-sensor environment was done by Singh and Atrey [46], and later an in-door experiment in a sphere of security proved the necessity of coopetition between sensors [45]. This revolutionary thought about cooperation and competition between sensors (cameras in this case), not humans or organizations, was clearly identified as a better approach in comparison to ‘only cooperation’ or ‘only competition’. The authors encouraged further investigators to extend the proposed framework for visual and non-visual sensors, which brings us again to the perspective of coopetition for CPS and their applications.

New concepts of value-based supply chain appeared recently. For instance, Berti & Mulligan [58] in their study of the nature of competitiveness of small farms and their organizational strategies concluded that strategic alliances and strategic networks towards shared value creation are one promising direction for further study. They offered “food hubs” as a special form of alliances and as intermediary organizations that have a coordinating function articulated in many tasks serving farmers, food processors, distributors, retailers and consumers and aimed to create “shared value” for mutual economic and social benefits. Further development of this idea is possible with the development of e-commerce platforms that connect small suppliers and enable transactions for consumers. Digital Food Hubs is a very promising disruptive technology that can allow to scale up a business without high capital investments, to overcome time limits, to facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration between participants [58]. This phenomenon, related as to coopetition, similar to the cybersecurity issues, is just one of the examples of emerging trends in technologies and research.

The issues of security and safety are interrelated and diverse, as well as studies in this sphere; for instance, we should mention promising contribution to blockchain-based framework by offering ‘cloudchain’, designed and developed by the research team [59] using the idea of coopetition for benefits of both as cloud providers, as well as users of smart contracts. The model offered in the paper [59] provides the best strategies in terms of transaction costs, time and reputation value. Authors argue that security concerns may be eased through the management of information sharing by a centralized trusted third party. But as we see at that point, the more complicated technology is for value development and deliver, more significant unexpected results could appear, and concerns about security arise more often.

Other studies use the term “coopetition” to a lesser extent but are not least fruitful in terms of findings. It is necessary to mention the study of [60], who developed an Analytic Hierarchy Process model for IoT (Internet of Things) Applications where security was named as one of the critical issues and technical requirements, and still ongoing challenges.

Coopetition is not mentioned in the study of Fuggetta and di Nitto [61], but they mentioned “openness” as the necessary condition of a search for new knowledge in a sphere of software development which is complex and multifaceted. Openness and exit the “zone of comfort” to combine the best solutions of computer science and software engineering research is considered by authors as a possible way for further investigations. We may add to this that this process can be facilitated under coopetitive interactions in R&D between software producers and engineers.

A new emerging trend in knowledge sharing, such as ‘crowdsourcing’ was recognized as a promising incentive in a sphere of biomedicine [62], which led to blurring the boarders of scientists community and changed the role of patient from a research subject to a data provider or even an expert. These emerging themes and new incentives are expected to be coordinated as integrative research, where many participants take part, which in our view is quite close to our understanding of coopetitive interactions.

Busse’s work [63] is mostly concentrated on sustainability-related conditions of supply chain management from the perspective of the buyer, and collaboration between buyer and supplier can be one of the mediating mechanisms to reach new standards in supply. Though Busse offered dyadic relationships to achieve the goals, the author argues that security issues can become a “bottleneck” in a process of interactions.

Separate aspects of coopetition organizational development and ideas related to security and safety were developed in several studies, such as development towards multiteam systems [64], collaborative networks and other forms of cooperation in the manufacturing the security-related products [65], safety-related challenges in a tourism sector [66], entrepreneurship and strategy in the informal economy [67], knowledge sharing at an individual level [68] or at level of multinational corporation [69], quality assurance in software ecosystems through the partnership of the actors [70], or role of financial safety in a process of R&D [37].

Sharing economy is an ideology, a strategy and a stream in the academic literature that offers multiple solutions for decentralized systems, as well as raises questions of safety support in addition to quality according to customers’ needs. Airbnb as one of the sharing economy start-ups was analyzed in [71], where transactions were perceived as a risk, a threat to residential communities and existing business-models at the beginning. Later, this business-model proved its viability, and new start-ups appeared in contrast to traditional firms in the tourism sector. Author [71] assures that coopetition strategy is a promising direction for further development of the industry that will enable to use the opportunities of cooperation inside of the sector at many levels and beyond.

In general, the competitiveness of business entities depends on their ability to identify and mitigate the uncertainties of the environment, which is crucial in supply chain risk management offered by the research team [72]. In their work, Vilko and his co-authors [72] generalized and structured different types of informational uncertainty, and did not mention coopetition at all, but we argue that coopetition can be one of the tools for mitigating the risks in supply and logistics management.

Detailed deductive analysis of the findings in the studies allowed us to structure the main trends in research and publishing as follows (Please see Table 3) by clustering them into 8 groups by content and findings. The general overviews without implementation for certain industry were excluded. As we see, Industry 4.0, cybersecurity, supply chain management and even biomedicine may become an area for successful implementation of coopetition strategy or certain coopetitive interactions.

Table 3.

Cluster analysis of the content for the chosen papers in a field of research: new challenges in safety & security.

The biggest clusters are the most dynamic in terms of the number of papers, age of publications (2014–2018 for Industry 4.0, and 2013–2018 for cybersecurity); other clusters are formed by one-two papers in a field and the most recent publication was in 2016. We should conclude that these two areas of future research in the coopetition field related to security and safety aspects may be identified as the leading clusters.

Comparing the findings from terms evolution analysis (Please see Figure 6) in the coopetition research and insights provided via content-analysis of recent papers on coopetition-related safety and security issues (Please see Table 2), we may assume the existence of several main trends. Cloud computing, information sharing, adaptive control systems are the newest terms in coopetition studies and “software development” unites them. Industry 4.0 and Cybersecurity as two main clusters provide ideas for new combinations of further research. We believe that issues that researchers will deal with in the near future will include:

- Joint software development projects performed via coopetition

- E-services and e-security provided by competitors through joint R&D

- Cyber-physical systems development within the global partnership in the context of Manufacturing Partnership (MP)

- Security challenges & knowledge and threat sharing paradox

- Security & safety standards development for coopetition alliances

- IT-solutions for coopetitive interactions

- Collaboration with agents and cooperation within multiagent systems

- Joint investments and joint start-ups in the context of Industry 4.0.

We believe that including more papers from Google Scholar will leave the results approximately the same. Thus, the results proved the thought about the necessity of concentrating efforts of researchers, and what is more important, of practitioners on security challenges and innovative decisions using the coopetition idea. This proves once again that airlines and aircraft manufacturers should design coopetitive decisions towards safety and security in the near future. We cannot suggest that Boeing and Airbus will be united for joint cybersecurity projects, but we may assume at least that the movement among airlines towards common and alternative safety standards (not FAA) will be started soon if it has not already been done. The joint software development project can be a core for the coopetitive agreements in the market, but to confirm or deny the possibility of the market evolution of that kind, further qualitative studies are needed.

The generalization of the future research trends will allow us to attract the practitioners and unite their efforts, as well as the efforts of the researchers, in a process of decision-making towards a secure and safe future within a coopetition framework.

4. Discussion

In the process of analyzing data, a researcher may intuitively search for data that confirm his/her beliefs [73] leading to bias in research. Despite our strong beliefs in a multidisciplinary of coopetition as a field of practical knowledge, experiments and theoretical research, we removed possible bias by combining the quantitative analysis for pre-selection of keywords and papers with the qualitative analysis for content of selected studies. The results confirmed at least two main tendencies worth of attention. Firstly, the trend in publications in the coopetition field showed sustained growth, and secondly, the areas of implementation of coopetition strategy expanded towards security and safety challenges in Industry 4.0, cybersecurity, supply chain management, biomedicine, tourism and many other fields.

Nevertheless, the study has its limitations. For instance, the papers for analysis were selected from the SCOPUS database, but the Web of Science may provide more papers in the field. It is possible that an analysis of papers from another database will bring new keywords and different understanding for the trends in research; also, it may bring a new understanding of the main contributors into the field and rearrange the rankings among the most influential researchers. However, this research is aimed to reveal the trends, not to give a ready-made prescription.

Another limitation of the research is that all data are secondary, but the analysis of the research trends can be done only using the published results. That is why the data choice is acquitted. However, the surveys among the researchers and R&D teams can bring new insights into understanding the future of safety and security.

The key studies in this sphere proved the benefits of data sharing, but at the same time, the cooperation between competitors in such a vulnerable sphere as software development, which is based on knowledge sharing and IT security information sharing, is still considered as a risky investment. To change this perception is a new challenge for future investigators and interdisciplinary researchers.

5. Conclusions

Coopetition is per se symbiotic relationships that are based on continuous, progressive and sustained decisions agreed between partners, where the cooperative interactions replace competitive and vice versa. Despite the obvious benefits of coopetition, huge competitive races take place in the spheres where safety risks may lead to human deaths.

Tragedies which occurred recently proved the necessity of launching a new era of airline safety which may be possible through coopetitive thinking.

This research aimed to shed light on the nature of coopetition, its perspectives for implementations for safety and security in general, and in a sphere of aircraft design, in particular. Collaboration across public and private sectors is no longer a revolutionary idea, but still, there are some barriers to accept the cooperation between competitors in highly competitive markets with sustained supply chains.

However, the bibliometric analysis revealed the growing tendency in publishing and research on coopetition, as well as the expansion of coopetition into other research fields. The combination of quantitative and qualitative methods of data processing allowed us to avoid bias in paper pre-selection. The citation analysis was done for 664 papers that are in the interdisciplinary research, and then content analysis was accomplished for 27 papers. Publish and Perish, BibExcel and VosViewer proved to be effective tools for revealing emerging trends in research, but at the same time, the intensity of keywords usage, co-citation analysis and visualization of terms evolution is only one of the steps in the study. The content analysis based on the deductive method may be helpful in the contextualization of the research. This hybrid method of verification of the trends in research is more solid in contrast to overviews that were done before.

It was revealed that coopetition ideas are beneficial for research streams in Industry 4.0, cybersecurity, sharing economy, supply chain management, solutions for interactions between sensors in a multi-sensor environment and many others. New areas of implementation of coopetition may include cyber-physical systems manufacturing, software development, blockchain interactions, different types of resource outsourcing, data mining and data sharing, decision-making in decentralized systems and other spheres where benefits of joint investments and R&D may be achieved. There is no evidence of joint cybersecurity or safety projects between main competitors in the aircraft industry yet, but this research was designed to prove the necessity of changing rules in the industry towards human-friendly innovations through coopetitive decisions. The trends that emerged in academic literature and case analysis of the recent events reinforced the conviction that coopetition is a very promising direction for future project development. The next stage of the research may be designed as the semi-structured interviews with the decision-makers in the industry about the possibility of mutual projects emphasized on cybersecurity, software development, IT-solutions and other types of interactions towards a better and safe common future.

Funding

The research was supported through a 2018-2019 Fulbright Scholar Award.

Acknowledgments

Special gratitude is expressed to the colleagues from Purdue University for their comments. We would like to acknowledge the administrative and technical support and especially research guidance provided by Vincent Duffy. We want to extend our appreciation to Shimon Y. Nof, who inspired researchers to investigate new horizons in science. We would like to thank Audrey Reinert for her diligent proofreading of this paper. We thank anonymous reviewers for careful reading of the manuscript and their insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Network visualization of most frequent terms (Constructed via VOSViewer v.1.6.10 for the sample N = 664, f (frequency) > 6).

Table A1.

Results of clustering the papers in the area of coopetition research (VOSviewer clasterization technique).

Table A1.

Results of clustering the papers in the area of coopetition research (VOSviewer clasterization technique).

| Cluster 1 (19 Items) | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (14 Items) | (12 Items) | (12 Items) | (10 Items) | (6 Items) | (2 Items) | |

| co-opetition | business ecosystem | business model | competition | behavioral research | adaptive control system | paradox |

| commerce | business model | business modeling | competitiveness | decision making | bipartite consensus | tension |

| competition | cloud computing | case study | cooperation | design | coopetition networks | |

| costs | collaboration | coopetition | cooperative behavior | information analysis | multi agent systems | |

| dynamics | competitive advantage | industrial management | human | information sharing | multi-agent systems | |

| economics | ecology | innovation | humans | information systems | structural balance | |

| electronic commerce | ecosystems | knowledge | management | knowledge management | ||

| game theory | open source software | open innovation | marketing | knowledge sharing | ||

| industry | open systems | smes | sustainable development | knowledge-sharing | ||

| informational management | open-coopetition | strategy | tourism economics | modeling | ||

| optimization | social networking (online) | technology | tourist destination | |||

| planning | software design | value creation | trust | |||

| profitability | software engineering | |||||

| project management | strategic alliance | |||||

| sales | ||||||

| supply chain management | ||||||

| supply chains | ||||||

| wireless network | ||||||

| wireless telecommunication |

Total: 75 items, 7 clusters.

References

- Ostrower, J. What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System? The Air Current. 17 November 2018. Available online: https://theaircurrent.com/aviation-safety/what-is-the-boeing-737-max-maneuvering-characteristics-augmentation-system-mcas-jt610/ (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Wichter, Z. What You Need to Know After Deadly Boeing 737 Max Crashes. New York Times. 24 May 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/business/boeing-737-crashes.html (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Campbell, D. Redline: The Many Human Errors that Brought down the Boeing 737 Max. The Verge. 9 May 2019. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/2/18518176/boeing-737-max-crash-problems-human-error-mcas-faa (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Isidore, C. Boeing’s Profit Falls 21% on the 737 Max Crisis. CNN Business. 24 April 2019. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2019/04/24/investing/boeing-earnings/index.html (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Genga, B.; Odeh, L. Boeing’s 737 Max Problems Put $600 Billion in Orders at Risk. Bloomberg. 19 March 2019. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-14/boeing-s-600-billion-in-max-orders-at-risk-as-airlines-retreat (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Reuters. Boeing Records Zero New 737 MAX Orders Following Worldwide Groundings. South China Morning Post. 10 April 2019. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/world/united-states-canada/article/3005463/boeing-records-zero-new-737-max-orders-following (accessed on 29 May 2019).

- Baker, S. Qatar Airways is Joining the Growing Number of Airlines Demanding Payback from Boeing for Its 737 Max Disaster—Here’s the Full List. Business Insider. 7 June 2019. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/boeing-737-max-crisis-air-china-calling-for-compensation-2019-5 (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Brandenburger, A.; Nalebuff, B. Co-Opetition, 1st ed.; Broadway Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996; 288p. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnino, G.B.; Di Guardo, M.C.; Padula, G. Coopetition: Nature, Challenges and Implications for Firms’ Strategic Behavior and Managerial Mindset. In Handbook of Research on Competitive Strategy; Dagnino, G.B., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northamptom, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 492–511. [Google Scholar]

- Padula, G.; Dagnino, G.B. Untangling the rise of coopetition: The intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. Int. Stud. Mang. Org. 2007, 37, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czakon, W. Emerging coopetition: An empirical investigation of coopetition as inter-organizational relationship instability. In Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century; Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, G.B., Le Roy, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northamptom, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M.; Kock, S. ”Coopetition” in business Networks—To cooperate and compete simultaneously. Ind. Market. Manag. 2000, 29, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Kock, S. Coopetition—Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Ind. Market. Manag. 2014, 43, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, F. Rivaliser et coopérer avec ses concurrents: Le cas des stratégies collectives «agglomérées». Rev. Française Gest. 2003, 2, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, F.; Sanou, F.H. Does coopetition strategy improve market performance? An empirical study in mobile phone industry. J. Econ. Manag. 2014, 17, 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chiambaretto, P.; Dumez, H. Toward a typology of coopetition: A multilevel approach. Int. Stud. Mang. Org. 2016, 46, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.S.; Chiambaretto, P. Managing tensions related to information in coopetition. Ind. Market. Manag. 2016, 53, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M.; Jordan, J.J.; Rand, D.G.; Wang, Z.; Boccaletti, S.; Szolnoki, A. Statistical physics of human cooperation. Phys. Rep. 2017, 687, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V.; Perc, M. Grand challenges in social physics: In pursuit of moral behavior. Front. Phys. 2018, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceptureanu, E.G.; Ceptureanu, S.I.; Olaru, M.; Bogdan, V.L. An exploratory study on coopetitive behavior in oil and gas distribution. Energies 2018, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceptureanu, E.G.; Ceptureanu, S.I.; Radulescu, V.; Ionescu, S. What makes coopetition successful? An inter-organizational side analysis on Critical Success Factors in oil and gas distribution networks. Energies 2018, 11, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, S.V.; Vasylieva, T.A.; Tsyganyuk, D.L. Formalization of functional limitations in functioning of co-investment funds basing on comparative analysis of financial markets within FM CEEC. Actual Probl. Econ. 2012, 134, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vasylieva, T.A. State and banks interaction in formation of national network of venture funds in Ukraine. Actual Probl. Econ. 2008, 82, 204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M.; Eriksson, J.; Wincent, J. Coopetition: New ideas for a new paradigm. In Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century; Yami, S., Castaldo, S., Dagnino, G.B., Le Roy, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northamptom, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, S.; Schweiger, B.; Albers, S. Levels, phases and themes of coopetition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, J. Conceptualizing coopetition as a process: An outline of change in cooperative and competitive interactions. Ind. Market. Manag. 2014, 43, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Toward coopetition within a multinational enterprise: A perspective from foreign subsidiaries. J. World Bus. 2005, 40, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R.A. Waking up to the new era of hypercompetition. Wash. Q. 1998, 21, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza-Ullah, T.; Bengtsson, M.; Kock, S. The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Ind. Market. Manag. 2014, 43, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtler, L.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Coopetition as a paradox: Integrative approaches in a multi-company, cross-sector partnership. Organ. Stud. 2016, 37, 655–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, D.V.B.; Franco, M. Trust-building mechanisms in a coopetition relationship: A case study design. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 378–394. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.E. Procurement effects on coopetition in client-contractor relationships. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Park, B.J.R. Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osarenkhoe, A. A study of inter-firm dynamics between competition and cooperation—A coopetition strategy. J. Database Mark. Cust. Strategy Manag. 2010, 17, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Clauß, T.; Fredrich, V. Product innovation through coopetition in alliances: Singular or plural governance? Ind. Market. Manag. 2016, 53, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Garcia, C.; Benavides-Velasco, C.A. Cooperation, competition, and innovative capability: A panel data of European dedicated biotechnology firms. Technovation 2004, 24, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-Y.; Wu, H.-L.; Pao, H.-W. How does R&D intensity influence firm explorativeness? Evidence of R&D active firms in four advanced countries. Technovation 2014, 34, 582–593. [Google Scholar]

- Czakon, W.; Mucha-Kuś, K. Coopetition research landscape—A systematic literature review 1997–2010. J. Econ. Manag. 2014, 17, 122–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.A.; Barnes, B.W. Client-server design provides model for ‘coopetition’ alliances. Comput. Healthc. 1992, 13, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual; Univeristeit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.10.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Perianes-Rodriguez, A.; Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J. Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 1178–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-García, N.; Jiménez-Contreras, E.; Torres-Salinas, D. Analyzing data citation practices using the data citation index. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2964–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Atrey, P.K.; Kankanhalli, M.S. Coopetitive multimedia surveillance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimedia Modeling MMM 2007 (Proceedings, Part II), Singapore, 9–12 January 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Atrey, P.K. Coopetitive visual surveillance using model predictive control. In Proceedings of the Third ACM International Workshop on Video Surveillance Sensor Networks, Singapore, 11 November 2005; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zrahia, A. Threat intelligence sharing between cybersecurity vendors: Network, dyadic, and agent views. J. Cybersecur. 2018, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appan, R.; Bacic, D. Impact of Information Technology (IT) Security Information Sharing among Competing IT Firms on Firm’s Financial Performance: An Empirical Investigation. CAIS 2016, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appan, R.; Bacic, D.; Madhavaram, S. Security Related Information Sharing among Firms: Potential Theoretical Explanations. In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–18 August 2018; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1404&context=amcis2018 (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Madhavan, R.; He, J.; Bengtsson, M. The competition–cooperation paradox in inter-firm relationships: A conceptual framework. Ind. Market. Manag. 2016, 53, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yami, S.; Nemeh, A. Organizing coopetition for innovation: The case of wireless telecommunication sector in Europe. Ind. Market. Manag. 2014, 43, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, N.; Kleindorfer, P. Co-opetition and investment for supply-chain resilience. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2009, 18, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Törngren, M.; Onori, M. Current status and advancement of cyber-physical systems in manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2015, 37, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership 2.0. Available online: https://www.manufacturing.gov/programs/mforesight-alliance-manufacturing-foresight (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Xu, L.D.; Xu, E.L.; Li, L. Industry 4.0: State of the art and future trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2941–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, M.; Nof, S.Y. The collaborative factory of the future. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2017, 30, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lacity, M.C.; Khan, S.A.; Yan, A. Review of the Empirical Business Services Sourcing Literature: An Update and Future Directions. J. Inf. Technol. 2016, 31, 269–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of Small Farms and Innovative Food Supply Chains: The Role of Food Hubs in Creating Sustainable Regional and Local Food Systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, M.; Bentahar, J.; Otrok, H.; Bakhtiyari, K. Cloudchain: A Blockchain-Based Coopetition Differential Game Model for Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing (ICSOC), Hangzhou, China, 12–15 November 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 146–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. A multi-criteria approach toward discovering killer IoT application in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 102, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuggetta, A.; Di Nitto, E. Software process. In Proceedings of the on Future of Software Engineering (POSE), Hyderabad, India, 31 May–7 June 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, R.; Good, B.M.; Leaman, R.; Su, A.I.; Lu, Z. Crowdsourcing in biomedicine: Challenges and opportunities. Brief. Bioinform. 2015, 17, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, C. Doing Well by Doing Good? The Self-interest of Buying Firms and Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 52, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, M.M.; DeChurch, L.A.; Mathieu, J.E. Multiteam Systems: A Structural Framework and Meso-Theory of System Functioning. J. Manag. 2015, 44, 1065–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M.; Friederichsen, N.; Keller, M.; Rosenberg, M. How virtualization, decentralization and network building change the manufacturing landscape: An Industry 4.0 Perspective. Int. J. Mech. Sci. Ind. Sci. Eng. 2014, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, G.; Bilgihan, A. Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 19, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.W.; Ireland, R.D.; Ketchen, D.J. Toward a greater understanding of entrepreneurship and strategy in the informal economy. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2014, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Ford, D.P.; Turel, O.; Gallupe, B.; Zweig, D. I’m busy (and competitive)! Antecedents of knowledge sharing under pressure. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2014, 12, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Hasan, I. Organizational culture, structure, technology infrastructure and knowledge sharing: Empirical evidence from MNCs based in Malaysia. Vine 2015, 45, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, J.; Skoglund, M. Quality assurance in software ecosystems: A systematic literature mapping and research agenda. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 114, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilko, J.; Ritala, P.; Edelmann, J. On uncertainty in supply chain risk management. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2014, 25, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Noble, H. Bias in research. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2014, 17, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).