Abstract

Background: Fire emergency management in healthcare facilities represents a complex challenge, particularly in historic buildings subject to architectural preservation constraints, where progressive horizontal evacuation is objectively difficult. This study analyzes the effectiveness of an evacuation sheet employed by Hospital Policlinico San Martino to improve the speed of evacuating non-self-sufficient patients in these buildings. Methods: This study involved evacuation simulations in wards previously selected based on structural characteristics. Healthcare personnel (male and female, aged between 30 and 55 years) conducted both horizontal and vertical patient evacuation drills, comparing the performance of the S-CAPEPOD® Evacuation Sheet (Standard Model) with the conventional method (hospital bed plus and rescue sheet). This study focused on the night shift to evaluate the most critical scenario in terms of human resources. Results: The use of the evacuation sheet proved more efficient than the conventional method throughout the entire evacuation route, especially during the first 15 min of the emergency (the most critical period). Indeed, with an equal number of available personnel, the evacuation sheet enabled an average improvement of 50% in the number of patients evacuated. Conclusions: The data support the effectiveness of the device, confirming the theoretical premise that the introduction of the evacuation sheet—also due to its ease of use—can be an improvement measure for the evacuation performance of non-self-sufficient patients, despite limitations related to structural variability and the simulated nature of the trials.

1. Introduction

Hospitals are not exempt from the destructive and catastrophic consequences to which all structures are subjected in the event of a fire. On the contrary, due to the vulnerability of hospitalized individuals, they are environments that must strive for the highest efficiency in activities aimed at mitigating the effects of a fire [1].

The issues associated with a fire occurring in a hospital are manifold and are rarely encountered, or only to a minimal extent, in other public buildings.

Firstly, the people involved: the primary users of the service are patients who, in the most critical conditions, may be non-self-sufficient, bedridden, or connected to life-support machines.

Furthermore, time plays a decisive role: the presence of patients and additional individuals (visitors) who are unfamiliar with evacuation routes and the structural layout of the building means that the time required to evacuate a specific area can be particularly prolonged, thereby compromising the safety of the occupants [2,3].

A recent study conducted in New Zealand [4] demonstrated that hospital evacuations are strongly influenced by alarm recognition times, decision-making processes, and patient preparation. The authors highlighted that these pre-evacuation times may exceed actual movement times, particularly when staff must mobilize bedridden patients, prepare evacuation devices, or coordinate actions with other personnel. Such delays are highly variable and dependent on the quality of training, familiarity with equipment, and the clinical complexity of the patients.

Similarly, another study [5] analyzed several evacuation drills conducted at North Shore Hospital (2018–2020), producing accurate quantitative data on both pre-evacuation and movement phases. Their findings confirm that the evacuation of non-ambulatory patients is the determining factor and that variability in staff responses—especially during night shifts—can generate substantial delays. In particular, patient preparation, transfer from bed to evacuation devices, and movement along narrow corridors or stairways were identified as the most critical steps.

Other studies have further examined the technical and behavioral aspects of assisted evacuation. One study [6] documented the considerable challenges associated with vertical evacuations, primarily linked to the physical effort required of staff and to constraints imposed by stairway characteristics (width, slope, and inadequacy of intermediate landings). Additional work [7], through numerical simulations and experimental trials, demonstrated that some movement devices can improve evacuation performance, but only if they are selected according to building characteristics and if staff receive specific training.

Overall, the literature indicates that the evacuation of dependent patients remains an underexplored area from an empirical standpoint and is characterized by significant operational constraints. The main recurring critical issues identified in international studies include:

A high incidence of initial time components, particularly those relating to patient preparation and safety procedures.

Architectural constraints, such as narrow corridors, non-standard stairways, and insufficient or missing compartmentation.

Reduced staff availability during night shifts, resulting in lower simultaneous evacuation capacity.

Limited availability or suitability of evacuation devices, particularly for vertical movement or for bariatric patients.

These elements align significantly with the Italian context. Many Italian hospitals are located in historical buildings dating back to before 1900, with an additional 35% constructed in the 1950s. Consequently, room layouts and circulation pathways reflect outdated design knowledge and functional requirements; moreover, heritage protection constraints often prevent significant structural modifications. Under these conditions, progressive horizontal evacuation—required by Italian regulations—is not always feasible due to inadequate internal compartmentation.

The Hospital Policlinico San Martino, established in 1923, is a major healthcare facility in Northern Italy. To understand the importance of fire prevention within its healthcare structures, the Occupational Health and Safety Office analyzed data relating to fires and fire incidents over the past 12 years.

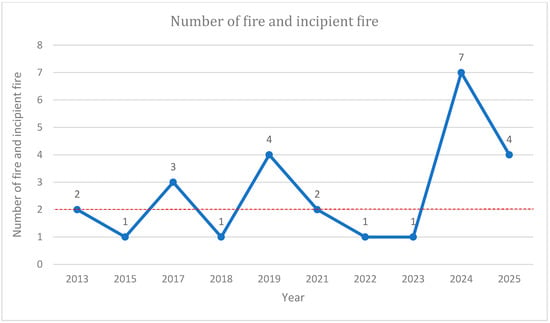

During this period, events occurring between 2013 and 2025 were reviewed, recording a total of 26 events, including 14 fires and 12 fire incidents (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Fires and incipient fires in Hospital Policlinico San Martino.

The year 2024 recorded the highest number of events, with a total of seven, whereas no events were reported in 2014, 2016, and 2020 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in fire incidents and incipient fire at Hospital Policlinico San Martino. The dashed line corresponds to the average of the events.

For improved representation, the graph highlights the trend of events over the period considered (2013–2025). An analysis of the data reveals an average of approximately two fires per year—a significant number given the potential consequences for patients and staff, as well as for the facility and equipment, that could result from an event of such magnitude.

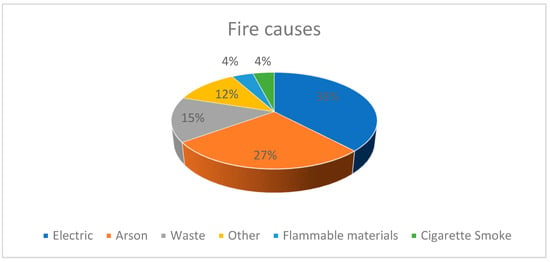

Following the analysis of individual fires and fire outbreaks, it can be concluded that electrical faults represent one of the primary causes (see Figure 2) [3,8].

Figure 2.

Main cause of fires and incipient fire at Hospital Policlinico San Martino.

The analysis revealed a significant probability that fires may originate within such healthcare facilities. Consequently, hospital staff must be adequately trained on patient evacuation procedures within hospital wards.

The Occupational Health and Safety Office, after analyzing fire safety challenges in selected hospital buildings and considering the type of occupants involved, set a goal to improve the efficiency of the evacuation process. This aim was pursued by introducing a new evacuation aid without increasing human resources: S-CAPEPOD® Evacuation Sheet (Standard Model) [9].

Before being distributed to the wards, the evacuation sheet was tested and evaluated by the Occupational Health and Safety Office, demonstrating its effectiveness due to the following features:

- Good patient tolerance;

- Ease of use;

- Increased number of patients that can be evacuated during the initial 15 min of an emergency;

- Minimal number of personnel required for its use;

- Greater operational support for healthcare workers compared to other devices currently in use.

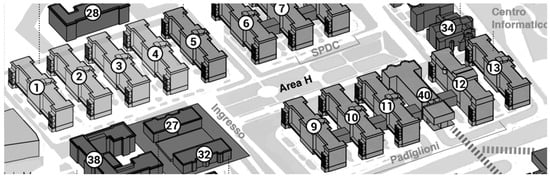

Hospital Policlinico San Martino consists of 42 pavilions (see Figure 3). The pavilions selected for this study were chosen based on the following criteria:

Figure 3.

Representation of halls 1, 5, 10 and 12 under study.

- Wards with a high number of non-self-sufficient patients.

- Awaiting completion of fire safety compliance measures in accordance with Italian legislation (Ministerial Decree of 19 March 2015), scheduled for completion by 2028.

- Low number of healthcare workers.

- Based on these criteria, four pavilions (1, 5, 10, and 12) were included in this study.

In these cases, the only viable solution for evacuation is vertical egress using the building’s internal stairwell with the support of the evacuation sheet.

2. Methods

2.1. Emergency and Evacuation Plan

In compliance with current regulations (Ministerial Decree of 2 September 2021) [10], Hospital Policlinico San Martino has implemented an Emergency and Evacuation plan. This document defines the responsibilities and roles of personnel to ensure safe, effective, and efficient responses in the event of a fire emergency and outlines procedures for managing various emergency scenarios.

Moreover, each ward adopts an Internal Emergency Plan, which provides all the necessary guidelines for the ward and the Fire Department for effective emergency management.

Among the emergencies with the greatest impact on the safety of both patients and healthcare workers is fire. As a result, annual evacuation drills are conducted in each ward [6].

2.2. The Organization of Evacuation Drills at Hospital Policlinico San Martino

In Italy, Ministerial Decree of 1 September 2021 [10] establishes the criteria for the assessment of fire risks in workplaces and defines the fire prevention and protection measures to be adopted in order to reduce the likelihood of a fire and to mitigate its consequences should one occur.

Legislative Decree No. 81 of 2008 [11] requires that, for emergency management, designated workers be appointed to implement fire prevention and firefighting measures. In all hospital unit, fire safety officers are present as required by current legislation.

The hospital’s emergency management system provides, in the event of a fire alarm, the activation of two emergency response teams. The first is defined by Ministerial Decree of 19 March 2015 [12] and consists of the compartment team, made up of healthcare personnel on duty in the ward (the workers), who must carry out the initial intervention by attempting to extinguish the fire using equipment located within the ward (such as fire extinguishers). The second team is composed of two dedicated fire emergency response teams, available 24/7, which intervene to support the initial efforts, attempt to extinguish any remaining fire, secure medical gas and electrical systems, and remain available for possible evacuation procedures.

At the Hospital Policlinico San Martino, annual training courses are held for ward staff in accordance with the above-mentioned Ministerial Decree of 1 September 2021, for activities classified as high fire risk.

Since this is a hospital, the evacuation strategy adopted is progressive horizontal evacuation. Patients are transferred from one fire compartment to an adjacent one, which is appropriately dimensioned in terms of space and support systems to accommodate them. Visitors and non-essential staff proceed to the external assembly point.

The emergency plan must be properly activated and, in order to assess its efficiency and functionality, it is tested several times a year. It is also supported by internal emergency plans tailored to each specific context. However, certain issues arise due to the particular type of building occupants and the unique nature of the activities carried out within the facility. Conducting evacuation drills under conditions that realistically simulate an actual emergency is extremely challenging. A full and indiscriminate evacuation of all occupants is not practically feasible, nor is the interruption of surgical and care procedures for the sake of an exercise. The primary objective remains ensuring the highest possible quality of care for the patient [13].

How, then, can staff be involved in emergency drills if they cannot suspend patient care, and if patients cannot be moved due to their critical condition?

A feasible solution is to carry out drills during shift changes, thereby ensuring a minimum level of staff presence to maintain continuity of care.

These exercises naturally do not involve patients and do not simulate a simultaneous evacuation of the entire building, but rather of a single ward or hospital unit.

At the end of each drill, a report is drafted identifying any critical issues encountered and proposing corrective or improvement actions.

The introduction of evacuation sheets in some pavilion has led to the organization of specific evacuation drills, following staff training, using this new aid (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Evacuation drill in pavilion 12.

It should be noted that the evacuation drills conducted for the present study were carried out exclusively in specific pavilions which, as will be detailed in the following chapters, share common structural characteristics. In particular, these buildings are not yet equipped with the compartmentalization required for the implementation of progressive horizontal evacuation and are therefore awaiting the fire safety upgrades mandated by current Italian regulations. For this reason, such pavilions constitute a significant operational context also from a scientific perspective regarding the adoption of the evacuation sheet.

2.3. Selection of Healthcare Staff and Patients

This study involved healthcare workers from various hospital units (M/F, aged between 30 and 55 years), making this study as realistic and representative as possible. Actors weighing between 50 kg and 100 kg were selected to play the role of patients, representing the most common weight range encountered in real-life settings.

The simulated work shift was the night shift, as it involves a reduced number of staff and therefore represents the most critical scenario in which workers may be required to manage an emergency [2,12,13,14].

In the simulations, with actors playing the role of patients and healthcare workers acting in their actual roles, an emergency situation was simulated involving the evacuation of a patient using the evacuation device from the patient room to the main entrance of the ward building.

2.4. Tetcon Global B.V. Evacuation Sheet

The evacuation sheet (see Figure 5) is a device made of 100% polyester, coated with an antibacterial film, washable and sanitizable, and classified as M1 (fire-retardant) with a maximum load capacity of 150 kg [9].

Figure 5.

Evacuation Sheet [9].

It is permanently positioned underneath the mattress, making it easily accessible to healthcare personnel. It does not require transferring the patient out of bed and eliminates the need for dedicated storage space.

Proper use of the device depends on correct placement on the bed, as improper positioning may compromise its effectiveness. For this reason, a comprehensive training, information, and instruction program was carried out by the Hospital’s Occupational Health and Safety Service.

2.5. Rescue Sheet

The conventional method involves the use of the hospital bed for horizontal transport and the rescue sheet (see Figure 6 and Figure 7) for vertical patient evacuation, with a maximum load capacity of 150 kg [15].

Figure 6.

Evacuation Sheet [9].

Figure 7.

Rescue sheet [15].

The use of the evacuation sheet requires at least two operators [16] to transport the patient.

During vertical movement, an additional two operators may be required to assist in lifting the device, in order to facilitate transport and reduce operator fatigue.

2.6. Training, Information, and Instruction for Workers on the Use of the Device

Training sessions were organized for healthcare personnel working in inpatient wards designated to use the evacuation sheet, with the aim of illustrating and sharing the rationale behind the selection of the device, its operational characteristics, and the procedures for preparing the evacuation sheet and evacuating the patient during both horizontal and vertical egress.

The Evacuation Sheet was supplied to the inpatient units of the buildings selected for this study.

Prior to the training, an instructional video and informational documents were produced and made available in order to provide the necessary knowledge for the proper use of the device. The video was recorded in teaching classrooms with the participation of two nursing students acting as a patient and a healthcare operator. It simulated the two main phases: the preparation phase of the evacuation sheet and the evacuation phase. The video demonstrated key considerations during sheet positioning, patient transfer from the bed, exiting the room, and transporting the patient down the stairs. The video was subsequently uploaded to the Hospital’s Intranet to allow staff to consult it over time, enabling self-retraining as needed.

The training was organized in such a way as to ensure the availability of the majority of nurses, physicians, and healthcare assistants. Accordingly, at least two training days were scheduled to allow all staff members the opportunity to participate. The sessions were held within the involved Operational Units to ensure testing under real usage conditions.

The training consisted of a theoretical component, during which the purpose of the evacuation sheet and its technical properties were explained, and a practical component—which was essential—in which the correct positioning of the device on the bed was demonstrated (see Figure 8). Common errors typically made during initial uses were highlighted. In addition, the correct method for patient transport was shown, with an emphasis on the use of the sheet strictly in emergency situations and not for routine patient transport.

Figure 8.

Training of personnel in the Hospital Policlinico San Martino.

Part of the training was dedicated to addressing questions and concerns raised by the staff, in order to clarify doubts related to the new device and to adjust subsequent training sessions accordingly.

During the training, healthcare personnel had the opportunity to simulate both the role of the patient and that of the rescuer.

The training sessions were also conducted in specific hospital wards where air-pressure-based anti-decubitus mattresses are in use. Since these include an integrated motor for inflation, special attention was given to checking the valve to prevent deflation during transport, which would otherwise make the evacuation procedure unfeasible.

Multiple evacuation drills were carried out using the evacuation sheet to simulate various possible scenarios during a fire. Given the diverse types of patients admitted to hospital wards, specific training was conducted for the evacuation of bariatric patients using the Evacuation Sheet, which supports a maximum load of 300 kg [9].

In this simulation, patient preparation and transport were carried out by two operators. It was observed that while two operators could perform the patient transfer from the bed, to exit the room they both needed to position themselves at the head of the bed, lifting the mattress as much as possible to reduce friction, until the sheet was correctly aligned with the evacuation route. Depending on the patient’s body structure and staff characteristics, assistance from a third operator—positioned at the head—may be required.

In the event that vertical evacuation becomes necessary, operators are instructed to position one person at the head and two at the feet, following the standard procedure for evacuating normoweight patients.

All training sessions held in the wards were recorded using dedicated documentation. It was noted that, on average, 10 healthcare professionals were trained per hour.

2.7. Wards of the Hospital Policlinico San Martino

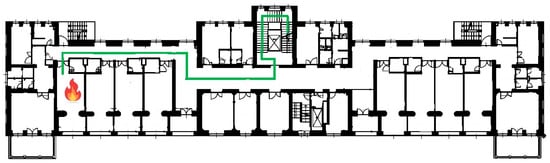

The wards in which this study was conducted share a similar layout to the floor plan shown below, consisting of 16 patient rooms and accommodating 30 non-self-sufficient patients [2,17,18], with no internal fire compartmentation (See Figure 9 and Figure 10). Moreover, the external emergency staircases can be used exclusively by ambulatory individuals and, consequently, are not included within the scope of the present study. During the night shift, the healthcare staff includes 2 nurses and 1 healthcare Assistant, with a maximum of 4 healthcare professionals available under optimal conditions.

Figure 9.

Ward floor plan.

Figure 10.

Egress path analyzed in the simulation for hall 1, 5, 10 and 12.

In the simulations, the fire ignition room was designated as the patient room farthest from the first fire compartmentation door. The predefined evacuation route (highlighted in green on the floor plan), followed during the drills, consisted of a horizontal egress along a corridor approximately 30 m in length, leading to the compartmentation door that provides access to the internal stairwell. This was followed by a vertical evacuation (18 m) to the main entrance of the building (lower floor), which was identified as a safe area where patients could remain while awaiting ambulance transport to another ward capable of ensuring continuity of care [8].

It must be highlighted that the routes employed in the simulations exhibit comparable lengths. In all the halls under study, evacuation was carried out by reaching the nearest internal staircase, which corresponds to the first compartmentalized area required for triage activities and the subsequent transfer of evacuated patients. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that not all the structures are equipped with a staircase specifically dedicated to evacuation.

The green line represents the evacuation route followed by non-self-sufficient patients, and the red symbol indicates where the fire started.

Following the selection of the hospital wards in which to conduct this study using both the Evacuation Sheet and the conventional evacuation method, a comparative analysis was carried out, focusing on evacuation times. The simulations considered multiple scenarios, which differed based on the type of patient and the composition of the healthcare personnel involved.

3. Results

Comparison Between Two Evacuation Methods

In the pavilions selected for the case study (1, 5, 10, and 12), following staff training and preparation, two evacuation drills were conducted (one in 2023 and one in 2024): one using the Evacuation Sheet and one using the conventional method, in order to compare the actual evacuation times of the two methods:

- Horizontal and vertical evacuation using the evacuation Sheet;

- Horizontal evacuation using the hospital bed, followed by vertical evacuation with a rescue sheet.

The comparison showed that the evacuation sheet outperformed the conventional method. This conclusion is supported by the recorded times, which demonstrate that the evacuation sheet allows for faster patient evacuation to a safe area, resulting in a significant overall time saving for the complete evacuation of the ward.

In addition to improving evacuation performance in terms of time—especially during the critical first 15 min of the emergency—the device also facilitates the task for healthcare personnel. It requires only a dragging motion for both horizontal and vertical evacuation, whereas the conventional rescue sheet necessitates lifting.

Another notable advantage is the reduced number of personnel required, enabling multiple patients to be evacuated simultaneously in emergency situations.

The following tables (see Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) summarize the evacuation times recorded during the simulations in the case study pavilions, as well as the time differences between the two evacuation methods.

Table 2.

Evacuation times and comparison between two evacuation methods.

The second simulation in each pavilion, conducted a year after the introduction of the new device, often showed improved times due to staff having become more familiar with the use of the evacuation sheet.

Simulation results clearly indicate that the use of the evacuation sheet leads to a significant time saving, which is critical, particularly during the initial phases of an emergency.

The evacuation times for individual patients in pavilions 1, 5, 10, and 12 are reported in the following tables. These results confirm the positive impact of the device on overall evacuation performance, supporting healthcare staff in its use.

The total evacuation time calculations consider the assistance of four operators in the first scenario (hospital bed and rescue sheet) and only two operators in the second scenario (evacuation sheet). This further supports the advantages of the evacuation sheet method, as it potentially doubles the efficiency of patient transfer to a safe zone.

In both scenarios, external emergency response teams—who typically arrive approximately 15 min after the event begins—were not considered in the simulations.

The tables summarize the results of the simulations:

Table 3.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 1.

Table 3.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 1.

| Pavillon 1 | Evacuation Times | Total Time for the First Attempt | Total Time for the Second Attempt | Evacuation Path Length (Horizontal/Vertical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital bed and rescue sheet | 3 min for bed preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 4 min for the transfer from the bed to the evacuation sheet and subsequent placement in the ambulance. | 7′ | // | 30 m/ 18 m |

| Evacuation Sheet | 1 min and 50 s for preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 41 s for the vertical evacuation. | 2′31″ | 2′48″ | 30 m/ 18 m |

Table 4.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 5.

Table 4.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 5.

| Pavillon 5 | Evacuation Times | Total Time for the First Attempt | Total Time for the Second Attempt | Evacuation Path Length (Horizontal/Vertical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital bed and rescue sheet | 2 min for bed preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 3 min for the transfer from the bed to the evacuation sheet and subsequent placement in the ambulance. | 5′ | // | 30 m/ 18 m |

| Evacuation Sheet | 1 min and 45 s for preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 50 s for the vertical evacuation. | 2′35″ | 2′44″ | 30 m/ 18 m |

Table 5.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 10.

Table 5.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 10.

| Pavillon 10 | Evacuation Times | Total Time for the First Attempt | Total Time for the Second Attempt | Evacuation Path Length (Horizontal/Vertical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital bed and rescue sheet | 2 min for bed preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 3 min and 15 s for the transfer from the bed to the evacuation sheet and subsequent placement in the ambulance. | 5′15″ | // | 30 m/ 18 m |

| Evacuation Sheet | 1 min and 50 s for preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 55 s for the vertical evacuation | 2′45″ | 2′04″ | 30 m/ 18 m |

Table 6.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 12.

Table 6.

Evacuation times per individual patient in pavilion 12.

| Pavillon 12 | Evacuation Times | Total Time for the First Attempt | Total Time for the Second Attempt | Evacuation Path Length (Horizontal/Vertical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital bed and rescue sheet | 2 min for bed preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 3 min e 30 s for the transfer from the bed to the evacuation sheet and subsequent placement in the ambulance. | 5′30″ | // | 30 m/ 18 m |

| Evacuation Sheet | 1 min 03 s for preparation and transport to the lobby in front of the stairs + 58 s for the vertical evacuation. | 2′01″ | 2′07″ | 30 m/ 18 m |

The second evacuation attempt employing the hospital bed in combination with the rescue sheet was not conducted, as subsequent simulations at the Hospital Policlinico San Martino were carried out exclusively using the evacuation sheet method. The simulation allowed for the assessment of average timings, calculated from the initiation of the evacuation drill.

Assuming a standard hospital ward with 30 patients, the corresponding table (see Table 7) provides an estimated number of patients that can be evacuated within the first 15 min of an emergency using the two methods under consideration.

Table 7.

Estimated number of patients evacuated within the first 15 min using the two evacuation methods.

For analytical consistency, the comparison was made using the best recorded evacuation time obtained with the evacuation sheet.

The findings from the simulations clearly indicate that the evacuation sheet method is the most time-efficient and allows for the highest number of patients to be evacuated within a limited timeframe.

The table (See Table 8) below summarizes the main results and differences identified in this study between the two evacuation methods:

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of the two evacuation procedures.

Although the use of the evacuation sheet has demonstrated time-saving benefits in other settings, its implementation in additional facilities will be assessed based on the specific characteristics of each pavilion. If deemed appropriate, the device will be deployed immediately. Alternatively, a hybrid evacuation strategy may be adopted, involving the use of the hospital bed for horizontal evacuation to the nearest safe area, followed by vertical evacuation using the evacuation sheet.

Currently, the scientific literature lacks data on evacuation aids specifically designed for the evacuation of non-self-sufficient patients. In the absence of such references, it was not possible to conduct a theoretical comparison between the various evacuation devices and the one adopted by the healthcare facility in this study.

4. Discussion

As demonstrated in the previous section, the measurements consistently revealed a significant advantage in using the Evacuation Sheet across all simulation scenarios.

Our findings indicate that the intervention implemented by the Policlinico—specifically, the provision of 300 evacuation sheets to the wards included in this study—significantly improved evacuation performance in the event of a fire emergency.

The results applied in real-world care settings highlight the critical importance of ensuring the highest possible effectiveness and efficiency, particularly during the first 15 min of the emergency. These initial minutes are commonly recognized as the decisive phase that directs the event toward a favorable outcome rather than a tragic one.

These results support the hypothesis outlined in the introduction, which proposed an alternative solution to the challenges of evacuating patients from architecturally constrained and structurally complex buildings. Specifically, this solution consists of replacing the conventional method (hospital bed + evacuation rescue sheet) with the use of an evacuation sheet. The superior performance of Evacuation Sheet is likely attributable to a combination of factors: its ease of use, its excellent sliding performance due to low surface friction, its suitability for both horizontal and vertical evacuation without the need to switch devices, and its positioning directly beneath the patient’s mattress, making it immediately accessible.

Comparison with the existing literature proved to be highly challenging. There is limited published data on evacuation times for non-self-sufficient patients in inpatient care settings, and, at the time of writing, no studies have been identified that evaluate the use of the Evacuation Sheet.

Although our study encompassed a total of 150 hospital beds across five buildings and involved 75% of the healthcare staff, the sample remains relatively limited in both spatial (five buildings) and temporal (four weeks) scope. We propose to expand and deepen this research in the near future, particularly through the inclusion of newly developed assistive devices specifically designed for the evacuation of non-self-sufficient patients (e.g., transport chairs).

Based on the simulation analysis, the evacuation sheet consistently yielded the best results—not only in terms of evacuation times but also due to a key advantage: the ability to place multiple individuals in the designated safe area while keeping escape routes clear for emergency personnel.

5. Conclusions

This study included a series of evacuation simulations to compare two evacuation methods for non-self-sufficient patients: the Evacuation Sheet versus the conventional method.

Simulations were carried out during the most critical work shift (night time), characterized by a reduced number of available personnel.

The time-based comparison focused on a 30-bed ward. Within the first 15 min of the emergency, the Evacuation Sheet—showing an average evacuation time of 2 min and 35 s (we considered the maximum recorded times)—proved to be 130% more effective in terms of the number of patients evacuated compared to the conventional method.

An additional factor considered was the number of operators required to handle each device. The evacuation sheet was found to be the most efficient aid, requiring only two staff members for both horizontal and vertical evacuation, unlike the conventional method, which required four operators—who were not always available during the simulations.

The data allow for an estimated evacuation time of the entire ward using both methods. Results show that, in the first 15 min, the evacuation sheet enables the evacuation of 7 patients, while the conventional method allows for the evacuation of only 3 patients—representing an efficiency gain of over 50%.

A purely theoretical arithmetic projection, based on the maximum recorded times, suggests a complete ward evacuation in 1 h and 09 min using the evacuation sheet, compared to 2 h and 58 min with the conventional method. However, this estimate does not account for the additional personnel foreseen in the hospital’s Fire Emergency Plan, and thus should be considered conservative.

Given the advantages observed, Hospital Policlinico San Martino has officially adopted the evacuation sheet in wards that have not yet been upgraded to meet fire safety regulations. The device will remain in use while awaiting compliance with the regulatory deadline established by Ministerial Decree 19 March 2015 (effective by 24 April 2028).

Data collected from the pavilions involved in this study indicate a reduction in evacuation time per patient by approximately 50%, which translates into the ability to evacuate twice as many patients within the same time frame.

The device was also positively received by the healthcare personnel involved, leading to spontaneous requests from units not originally included in the trial—due to existing fire compartmentation measures—to be equipped with the evacuation sheet. This demonstrates that Hospital Policlinico San Martino has successfully promoted a shift in emergency evacuation practices as a proactive improvement measure.

The Occupational Health and Safety Office is planning to expand this study to include additional pavilions with similar characteristics, and to introduce new evacuation devices—such as evacuation chairs—in order to reinforce and build upon the findings of the current study.

Author Contributions

S.A., F.O., A.F. and D.S. contributed to the design and implementation of the research and contributed to the analysis of the results, and S.A., F.O. and A.F. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Comitato Etico Territoriale—Liguria (protocol: Rich.Pubb. ACCORSI_09.25, 22 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sahebi, A.; Jahangiri, K.; Alibabaei, A.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D. Factor influencing hospital emergency evacuation during fire: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rahouti, A.; Datoussaïd, S.; Lovreglio, R. A sensitivity analysis of a hospital evacuation in case of fire. In Proceedings of the Fire and Evacuation Modelling Technical Conference, Malaga, Spain, 16–18 November 2016; Semantic Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Viannello, C.; De Cet, G.; Mancin, F. Drafting of Guidelines for the Proper Execution of Emergency and Evacuation Simulation in a Hospital Environment. Master’s Thesis, University of Padua, Padova, Italy, Academic year. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Geoerg, P.; de Schot, L.; Lovreglio, R. Decoding Hospital Evacuation Drills: Pre-movement and Movement Analysis in New Zealand. Fire Technol. 2025, 61, 4303–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahouti, A.; Lovreglio, R.; Jackson, P.; Datoussaid, S. Evacuation Data from a Hospital Outpatient Drill the Case Study of North Shore Hospital. Collect. Dyn. 2020, 5, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salway, R.J.; Adler, Z.; Williams, T.; Nwoke, F.; Roblin, P.; Arquilla, B. The Challenges of a Vertical Evacuation Drill. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2019, 34, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, A. Simulating Hospital Evacuation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Greenwich, London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abir, I.M.; Mohd Ibrahim, A.; Toha, F.S.; Shafie, A.A. A review on the hospital evacuation simulation models. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetcon Techinical Textile Concepts (Eindhoven NL). Available online: https://tetcon-ge.com/en/about-tetcon/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Ministerial Decree of September 1st, 2nd and 3rd 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.vigilfuoco.it/sites/default/files/Teramo/formazione/D.M.%2002_09_2021.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Legislative Decree No. 81/2008. 2008. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/2008_0081.htm (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Ministerial Decree of March 19th, 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.vigilfuoco.it/sites/default/files/2022-10/COORD_DM_03_08_2015_Codice_Prevenzione_Incendi.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Catovic, L.; Alniemi, C.; Ronchi, E. A survey on the factors affecting horizontal assisted evacuation in hospitals. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1107, 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, A.; Grossi, L.; Ursetta, D.; Carbotti, G.; Poggi, L. Egress from a hospital ward during fire emergency. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, A.; Jahangiri, K.; Alibabaei, A.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D. Factors affecting emergency evacuation of Iranian hospitals in fire: A qualitative study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ONFARMA. Available online: https://www.onfarma.it/products/telo-portaferiti?srsltid=AfmBOopINwUwzuYjvFA3RerQqgD2UuCtEybDUo5_7H7EJRL0Ckgkv56B (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Hunt, A.; Galea, E.R.; Lawrence, P.J. An analysis and numerical simulation of the performance of trained hospital staff using movement assist devices to evacuate people with reduced mobility. Fire Mater. 2015, 39, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncıtürk, N. An evaluation of hospital evacuation strategies with an example. Int. J. Appl. 2015, 5, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.