Abstract

The present study examines the well-being of workers in an Italian manufacturing plant, focusing on work engagement, emotional exhaustion and work ability. These dimensions have received relatively little attention in manufacturing contexts. Utilising a person-centred approach, the objective is to identify distinct subjective well-being profiles among Italian manufacturing workers and to examine how work-related psychosocial characteristics differentiate these profiles. The research, which collected data from 340 workers (predominantly male at 62.1%) between July and September 2023, focused on work engagement, emotional exhaustion, and work ability—factors that have been previously understudied in manufacturing environments. Through cluster analysis, researchers were able to identify three worker profiles. The largest group, designated “Motivated & Healthy” (45.3%), exhibited the most favourable characteristics: strong work engagement, minimal emotional exhaustion, and adequate work ability. These workers reported experiencing reduced physical demands, greater autonomy in decision-making, and superior rewards compared to their colleagues. The second-largest group, “Motivated & Stressed” (32.5%), demonstrated a mixed profile. While maintaining average work engagement, these workers experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and diminished work ability. The smallest group, termed “Disillusioned” (22.2%), consisted entirely of blue-collar workers and exhibited the most concerning pattern: low engagement, high exhaustion, and mediocre work ability. This group also reported the most challenging working conditions, including the highest physical and cognitive demands, least decision-making authority, and lowest rewards. The study corroborates earlier research findings by identifying significant relationships between work engagement and work ability (positive correlation) and emotional exhaustion (negative correlation). These results suggest that manufacturing facilities might benefit from tailoring their support strategies to address the specific needs of each worker profile, rather than applying one-size-fits-all solutions.

1. Introduction

The Italian manufacturing environment is distinguished by a number of distinctive characteristics in comparison to other industrialised countries. This sector is highly diversified and advanced, contributing significantly to the national economy. It encompasses a range of industries, including mechanical engineering, automotive, textiles, food, chemicals and fashion, with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) playing a pivotal role [1]. The manufacturing sector in Italy accounts for approximately 16% of GDP and employs over 4 million workers, representing a critical component of the national economy [2]. Italian manufacturing is characterized by a prevalence of family-owned SMEs, with 95% of manufacturing firms employing fewer than 250 workers, creating unique organizational dynamics and workplace cultures [1].

In addition to the challenges of globalisation, international competition and environmental sustainability, a growing number of businesses are directing attention towards the psychological and physical wellbeing of their employees. It is a fundamental tenet of occupational psychology that all jobs entail a certain degree of occupational stress [3]. In contrast, excessive occupational stress has been identified as a detrimental factor in the workplace, with a strong correlation between this phenomenon and both physical and mental health outcomes. The results of research studies indicate that working under conditions of stress increases the likelihood of burnout [4], poor health [5], and cardiovascular problems [6].

The majority of research investigating the relationship between occupational stress and mental health has focused on three key professional groups: medical professionals, educators and information technology workers [7]. Meanwhile, research on the psychological well-being of factory workers has been overlooked in favour of studies on the health concerns associated with occupational exposure [8]. Recent systematic reviews have identified this significant gap, noting that while manufacturing represents one of the largest employment sectors globally, empirical research on worker well-being in this context remains limited [9,10]. Existing studies on manufacturing workers have primarily focused on physical health outcomes, safety incidents, and ergonomic factors [11], with considerably less attention paid to psychological well-being constructs such as work engagement and emotional exhaustion [12].

Where studies do exist examining psychological well-being in manufacturing settings, they have predominantly been conducted in Northern European or North American contexts [13,14], with limited research addressing the specific characteristics of Mediterranean manufacturing environments. The few studies conducted in Italian manufacturing contexts have typically focused on specific hazards or single dimensions of well-being rather than adopting an integrative, person-centered approach [15]. Furthermore, previous research has rarely examined the intersection of work engagement, emotional exhaustion, and work ability simultaneously within manufacturing populations, despite theoretical arguments for their interconnectedness [16,17].

This study addresses a gap in the existing literature on work engagement and work ability by examining these constructs in a sample of Italian workers employed in a manufacturing context. Specifically, this research contributes to the literature by: (1) providing empirical data on psychological well-being in an underresearched population (Italian manufacturing workers); (2) employing a person-centered analytical approach that identifies naturally occurring profiles rather than examining variable relationships in isolation; and (3) integrating multiple well-being indicators (engagement, exhaustion, work ability) to provide a holistic understanding of worker experiences.

1.1. Work Engagement and Burnout

According to Schaufeli and Bakker [18], burnout and work engagement are the primary markers of psychological well-being for employees and act as mediators in health impairment and motivational processes. Schaufeli and Enzmann [19] define burnout as “a persistent, negative, work-related state of mind in ‘normal’ individuals, primarily characterised by exhaustion, accompanied by distress, a sense of diminished efficacy, diminished motivation, and the development of dysfunctional attitudes and behaviours at work”(p. 36). Exhaustion, defined as personal tension and fatigue brought about by the depletion of emotional and psychological reserves, and cynicism, defined as a sour or unfavourable attitude towards one’s work as a result of being unable to cope with the demands of the job, are the two main components of burnout.

The concept of work engagement has emerged as a positive feature of work in burnout research, coinciding with the introduction of positive psychology. Schaufeli et al. [20] proposed that work engagement should be defined and assessed independently. Some individuals thrive under work-related pressures, in contrast to those who experience burnout, and demonstrate high levels of work engagement.

According to Schaufeli and Bakker [21], work engagement is a multifaceted construct that may be conceptualized as a positive, rewarding state of mind relating to one’s work that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption. High levels of energy, mental fortitude, and perseverance in work are examples of vigor. Having a sense of importance, excitement, and pride in one’s work is referred to as commitment. When one is completely absorbed in their task, time flies by and it is challenging to step away. This is referred to as absorption [22,23].

Maslach et al. [24] argue that work engagement represents the positive end of the spectrum and is the antithesis of burnout. Furthermore, Schaufeli et al. [15,25] propose that vitality and devotion are the exact opposites of emotional fatigue and cynicism, respectively.

1.2. Work Ability in Manufacturing Sector

According to Ilmarinen et al. [26], work ability is the ability of workers (including both manual and non-manual workers) to perform their jobs in accordance with the demands of their jobs and their physical and mental resources. Therefore, it is assumed that a mismatch between an individual’s resources and the demands of his or her job leads to reduced work ability. As a result, job-related factors such as demands and working conditions play an important role in determining work ability. Individual resources are also related to work ability, including health and functional capacity, knowledge and skills, values, attitudes and motivation [27]. In the health care sector [28,29], among municipal workers [30,31], among blue-collar workers [32], and among representative samples of the working population [26], factors such as age, alcohol consumption, obesity, job demands and physical workload have all been empirically associated with reduced work capacity.

In the manufacturing, construction and maintenance industries, workers perform physically demanding tasks that require considerable strength and expertise. The manufacturing sector presents unique occupational challenges characterized by repetitive manual tasks, exposure to physical hazards, shift work patterns, and high production demands [33,34]. These working conditions have been consistently associated with elevated rates of musculoskeletal disorders, fatigue, and reduced work ability across international studies [11,35]. For instance, employees involved in the moulding and polishing of seal rings for heavy transportation vehicles, such as trucks and lorries, handle, polish and machine these components in a labour-intensive environment where production demands are high. While such work demands physical capability, it also requires specific skills, knowledge and careful judgement to be performed safely. The repetitive nature of these manual tasks can lead to various health issues, including respiratory problems and musculoskeletal disorders. Given these occupational challenges, it becomes crucial to assess workers’ ability to perform their jobs effectively and safely. The Work Ability Index (WAI), developed by Ilmarinen et al. in 1997 [26], serves this purpose by evaluating three key components: an individual’s current health status, their job’s specific demands, and the workplace support systems available to them. The utilisation of this instrument facilitates the identification of individuals necessitating interventions to enhance their work capacity, while concurrently enabling the prediction of those susceptible to incapacitation due to health-related concerns. The WAI comprises a questionnaire that can be completed by the workers themselves or by designated professionals, including vocational rehabilitation counsellors and healthcare providers. The assessment gathers comprehensive information about the person’s current health condition, their ability to perform various work-related tasks, and the level of social support they receive in their work environment [32].

In the workplace, job dissatisfaction, high work demands and repetitive tasks are strongly associated with the development and progression of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) [36]. This is particularly evident among blue-collar workers, whose main occupation is manual labour [11,37]. The higher prevalence of MSDs in this group is partly due to the nature of their work [33,34,37]. On average, blue-collar workers tend to have less healthy lifestyles, poorer general health and shorter life expectancy than white-collar workers [38]. There is increasing recognition of the need to prevent MSDs in the workplace, particularly among blue-collar workers [39,40].

2. Objective

The main objective of this study is to identify different subjective well-being (i.e., work engagement, emotional exhaustion, work ability) profiles within a population of workers in an Italian manufacturing company using a person-centered cluster analysis approach. Specifically, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- RQ1: What distinct well-being profiles can be identified among Italian manufacturing workers based on their levels of work engagement, emotional exhaustion, and work ability?

- RQ2: How do these well-being profiles differ in terms of psychosocial work characteristics (job demands, decision latitude, rewards)?

- RQ3: What are the demographic and occupational characteristics associated with membership in each profile?

We carried out this study on this type of population because it is rarely subjected to studies characterised by a person-centred approach. Despite the critical working conditions [15] in the Italian firms, the study of these phenomena within the manufacturing context in Italy has not been particularly thorough. This study fills an important gap in the existing literature on work engagement and work ability by: (1) examining these constructs simultaneously in a sample of Italian manufacturing workers; (2) employing person-centered methods to identify naturally occurring profiles rather than examining variables in isolation; and (3) providing practical insights for organizational interventions tailored to specific worker profiles rather than one-size-fits-all approaches.

3. Material and Methods

Data Collection Participant

The objective of the study was to formulate a unified methodology for conducting the research. The facility under consideration is a medium-sized manufacturing plant (with approximately 550 workers) located in Northwest Italy. It specialises in the production of mechanical sealing components for heavy transportation vehicles. The selection of this plant was made on the basis of its representativeness of the Italian manufacturing sector, as well as the management’s demonstrated commitment to participating in occupational health research. The facility operates continuous production cycles with shift work patterns, which are characteristic of the Italian manufacturing industry.

Of the 550 employees, 379 questionnaires were distributed, and 340 of these were found to be usable for the research, resulting in a response rate of 89.7%.

The sample size was determined based on recommendations for cluster analysis, which suggest a minimum of 2^k cases (where k is the number of clustering variables) to ensure stable solutions [41]. With three clustering variables (work engagement, emotional exhaustion, work ability), this required a minimum of 8 cases, which was substantially exceeded. Additionally, considering the facility employed approximately 380 workers, a sample of 340 provides adequate representation with a margin of error of ±2.5% at 95% confidence level for population-level estimates.

Data collection was conducted through a survey administered between July and September 2023, targeting all employees at a manufacturing plant in northern Italy. Participants completed a self-report questionnaire using a paper-and-pencil format. Surveys were conducted during working hours on designated days, with a researcher from the University of Turin available to assist employees as needed. Anonymity and voluntary participation were guaranteed throughout the study.

The survey was conducted in accordance with the principles of scientific rigor and privacy. The research protocol complied with Italian Law 101/2018 on workplace privacy protection and adhered to the ethical guidelines of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in Fortaleza in 2013. All research standards for studies involving human subjects were upheld. A cover letter accompanied the questionnaire, outlining the study’s purpose and ensuring participants of the anonymity of data collection and processing. The participants were informed that their involvement was entirely voluntary, and their consent was formalised by their signature on a dedicated form. To ensure the security of personal data, the research project was registered with the professional association of psychologists and conducted in accordance with relevant Italian legislation. Furthermore, all responses were processed exclusively in aggregate form.

One way to compare a person-centered method is with regularly used variable-centered approaches, like structural equation modeling or regression analysis. Typically, variable-centered techniques divide the complicated reality into discrete variables. Their objective is to ascertain the correlations between independent and dependent variables and evaluate the degree of these correlations on a collective scale. Because they emphasize the experiences of individuals, person-centered techniques may be a good complement to this variable-centered approach [42].

Person-centered approaches, such as cluster analysis, are particularly valuable when the research goal is to identify qualitatively distinct subgroups within a population rather than examining linear relationships between variables [43]. This approach aligns with contemporary organizational psychology perspectives that recognize workers as holistic individuals exhibiting unique configurations of characteristics rather than uniform populations varying only in degree [44]. In the context of occupational well-being, person-centered methods enable the identification of risk groups and resilient groups, facilitating targeted interventions [45].

In particular, cluster analysis allows the identification and the comparison of naturally occurring groups characterised by specific profiles. In the context of work motivation, this approach enables the investigation of the quantity and quality of motivation exhibited by individuals within a given group. Consequently, cluster analysis facilitates the formulation of inferences at the group level, which may inform the prediction of work-related success or the potential for negative outcomes such as burnout.

4. Measures

4.1. Background Variables

The survey commenced with a section designed to elicit socio-demographic information from participants. The section included questions about gender (male or female) and age, which were later categorised into four groups: 19–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–65 years. Furthermore, respondents were invited to disclose the duration of their professional tenure, which was then categorised into four distinct groupings: 0–10, 11–20, 21–30, and 31–40 years. The questionnaire also incorporated a series of binary questions covering key topics, such as the presence of children under 16, the care of other dependents, the utilisation of Act 104 relief [46], and the performance of shift work, including night shifts. Italian Law 104/1992 provides statutory benefits for individuals with disabilities and their family caregivers, including paid leave and workplace accommodations. In the manufacturing context, these provisions are particularly relevant as workers may need to balance demanding physical work with caregiving responsibilities. Statutory benefits for personal health issues or caregiving responsibilities were introduced 30 years ago, primarily to support individuals with severe disabilities. At that time, assistance for elderly care was less common due to a declining elderly population and a reduced retirement age, which meant that caregiving was largely managed by families, particularly retired women [32]. Today, with an aging population and changing family structures, Law 104 benefits have become increasingly important for manufacturing workers who often face the dual burden of physically demanding work and family care responsibilities [46].

4.2. Work Ability

The Work Ability Index (WAI) [47] was utilised to assess work ability, with the index comprising seven sections, each contributing to the overall WA score (ranging from 7 to 49). These sections evaluate: Firstly, the current work ability is evaluated in comparison to the participant’s lifetime best. Secondly, work ability is evaluated in relation to physical and mental job demands. Thirdly, the number of doctor-diagnosed medical conditions is recorded. Fourthly, perceived work impairment due to illness is documented. Fifthly, sick leave taken in the past 12 months is recorded. Sixthly, self-predicted work ability over the next two years is documented. Seventhly, psychological resources are evaluated. The scale demonstrates strong reliability (α = 0.745, M = 37.92, SD = 6.37).

4.3. Work Engagement

Work engagement (WE) was analysed through the utilisation of the 9-item Italian adaptation of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (U-WES9) [48,49], which is regarded as a one-dimensional scale (9 items, α = 0.940, M = 42.64, SD = 15.7) (e.g., I am enthusiastic about my job.).

4.4. Emotional Exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion (EE) was measured with a five-item subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI, e.g., ‘I feel emotionally drained from my work’) [50]. The scale has good reliability (α = 0.883, M = 18.55, SD = 8.34).

In order to ascertain the responses to both emotional exhaustion and work engagement measures, subjects were invited to allocate a score on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day).

4.5. Psychosocial Work-Related Characteristics

4.5.1. Job Demands

The physical demands of the job were assessed using a subscale derived from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [51]. This subscale comprises five items (e.g., “My job requires lots of physical effort”) and demonstrates strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.84). The assessment of cognitive demands was facilitated by a separate JCQ subscale comprising six items (e.g., ‘I have such a heavy workload that I cannot complete it on time’), also demonstrating strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

The responses to each scale were evaluated on a 4-point scale, with the range of possible responses from 1 (‘never/not at all’) to 4 (‘always/very often’).

4.5.2. Decision Latitude: Discretionary Skills and Decision Authority

Decision latitude, otherwise referred to as job control, is a pivotal concept in comprehending job design and its repercussions on employee well-being and performance [51]. It is composed of two primary components: Skill Discretion and Decision Authority. These components facilitate the evaluation of the level of control and autonomy an employee has over their work.

Discretionary skills are assessed using a set of questions from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [51], comprising six items (e.g., “My job requires a high level of skill”). Reliability analysis confirms the measure’s consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.75).

Decision authority refers to an employee’s ability to control their work tasks and methods. This aspect evaluates the extent to which individuals can make job-related decisions and influence how their tasks are performed. It includes three items (e.g., “I have a lot of say in what happens in my work”), with reliability analysis confirming its consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

To establish the responses to the measures of skills discretion and decision authority, the responses to this subscale were on a 4-point scale with a range from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

4.5.3. Reward

The effort-reward imbalance (ERI) questionnaire developed by Siegrist [52] was employed, comprising a four-item reward subscale (for example, “My current occupational position adequately reflects my education and training”). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” to “completely.” The scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.82).

4.5.4. Presence of Pathologies

The medical records pertaining to the company health surveillance programme enabled us to ascertain the prevalence of pathologies within the sample. In particular, we focused on musculoskeletal pathologies, which are the most common in this occupational context. The health surveillance data provided by the company’s occupational health service documented diagnosed conditions based on medical examinations conducted as part of routine workplace health monitoring. This information was particularly valuable given the high physical demands of manufacturing work and the known prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in this sector.

Participants

The final sample comprised 340 questionnaires, representing a response rate of 89.7%, out of 379 distributed. Table 1 details the sample’s sociodemographic and occupational profile.

Table 1.

Description of the sample.

The gender distribution revealed a male majority of 62.1% (211 participants) and a female minority of 37.6% (128 participants), with one participant who did not specify their gender. The age range of the participants was from 21 to 64 years, with a mean of 45.3 years (SD = 9.62). The age distribution was as follows: 21.1% of the sample were between the ages of 19 and 30, 23.5% between 31 and 40, 41.9% between 41 and 50, and 13.6% between 51 and 64.

With regard to benefits under Law No. 104/1992 [46], 8.7% of respondents (29 participants) reported receiving personal benefits. Amongst these benefit recipients, 14.2% reported having dependent family members, such as non-self-sufficient parents. Most participants (58.3%) had children aged 16 or older [32].

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Cluster analysis is a statistical method utilised for the purpose of grouping individuals exhibiting similar responses based on a given set of variables [53]. In this study, cluster analysis was conducted using SPSS 28 to identify homogeneous subgroups of workers based on selected variables. The identification of worker profiles followed a two-step process. Initially, hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method [54] was applied to factor scores in order to ascertain the number of profiles. The optimal number of clusters was identified by analysing the agglomeration plot, which tracks changes in cluster distances, and the dendrogram, which indicates the best fit index. In the second step, k-means cluster analysis was performed to refine and optimise the classification.

The validity of the cluster solution was assessed through multiple criteria: (1) interpretability of the cluster profiles based on theoretical frameworks; (2) adequate cluster sizes with no cluster containing fewer than 5% of the sample; (3) significant between-cluster differences on clustering variables verified through ANOVA; and (4) examination of cluster stability through split-sample validation procedures. Furthermore, the cluster solution was evaluated for its practical utility in identifying distinct groups that could inform targeted organizational interventions [55].

To further examine the characteristics of each cluster, the researchers used contingency tables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess differences between the identified profiles.

5. Results

Table 2 shows the results of the correlation analysis between all the variables considered for this study. A significant and positive correlation was found between work engagement and work ability, while significant and negative correlations were found between emotional exhaustion and work engagement and between emotional exhaustion and work ability. This is in line with Maslach et al.’s [56] thesis that work engagement can be seen as the antithesis of burnout, as high levels of work engagement are associated with low levels of exhaustion. Similarly, when employees perceive themselves to be more engaged in their work, they show better work ability.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations among study variables.

Identification of Clusters

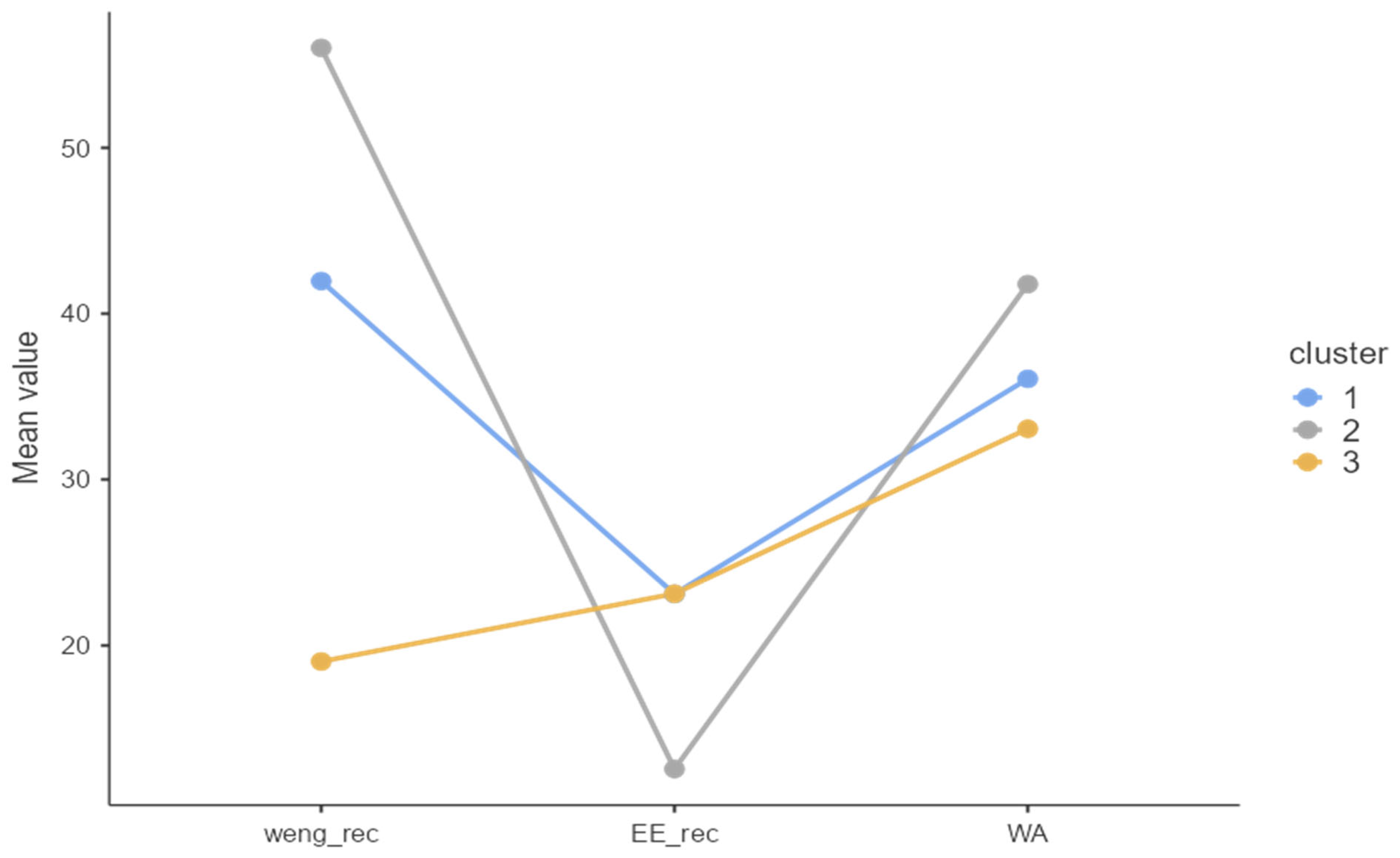

Figure 1 illustrates the cluster solution, showing the three different profiles based on the scores of the different dimensions considered. Cluster 1 (Disillusioned) is represented by the solid line, Cluster 2 (Motivated & Healthy) by the dashed line, and Cluster 3 (Motivated & Stressed) by the dotted line. Table 3 shows the mean (M) for each outcome in the different clusters.

Figure 1.

Plot of means across clusters. [Note: Cluster labels should be added directly to the figure: Cluster 1 = Disillusioned; Cluster 2 = Motivated & Healthy; Cluster 3 = Motivated & Stressed].

Table 3.

Cluster Final Centres.

The clusters were labelled as follows:

Disillusioned. Cluster 1 comprises 69 participants, representing 22.2% of the total sample. The first cluster is represented by very low work engagement scores (M = 19.04), high emotional exhaustion scores (M = 23.12) and the presence of mediocre work ability (M = 33).

Motivated & Healthy. Cluster 2 is the largest, with 141 participants, accounting for 45.3% of the total. The second cluster shows the highest levels of work engagement (M = 55.95) and the lowest levels of emotional exhaustion (M = 12.6). These are followed by levels of work ability that are considered to be good (M = 42).

Motivated & Stressed. Cluster 3 includes 32.5% of the workers, with a total of 101 participants. The third cluster shows average work engagement scores (M = 41.92), but high levels of emotional exhaustion (M = 23.19), slightly higher than those in cluster 1, and consequently lower levels of work ability (m = 36), which is considered mediocre.

Characteristics of clusters and Psychosocial Work-Related Characteristics

Regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of first cluster, it is worth highlighting that it is characterised by the presence of only blue-collar workers, with an average of 19.7 years of work in the company (SD = 8.5) and an average age of 46 years (SD = 9.1). In terms of the psychosocial work-related characteristics examined, this cluster presents the higher levels of physical (M = 12.04; SD = 3.58) and cognitive demands (M = 13.58; SD = 4.06). With regard to decision latitude, this cluster exhibits the lowest level of the construct (M = 4.0; SD = 1.33), as do its two components: discretionary skills (M = 10.32; SD = 2.8) and decision authority (M = 13.14; SD = 3.96). Additionally, the disillusioned group demonstrates the lowest level of reward at work (M = 8.74; SD = 2.75). As mentioned above, we also checked for the presence or absence of pathologies, with particular reference to musculoskeletal disorders. In this cluster, 42 subjects had pathologies, 22 of which were musculoskeletal.

In the Cluster 2, Motivated & Healthy, it is worth noting that there are also 35 white-collar workers in addition to 106 blue collars; the average length of service is the lowest compared to the other two clusters (M = 15.3, SD = 8.66), as is age (M = 43.5, SD = 10.0). The physical and cognitive demands within this cluster were the lowest of all the clusters analysed (M = 8.33; SD = 3.2 and M = 12.14; SD = 3.54, respectively). In contrast to the first cluster, the dimensions of decision latitude are the highest overall (M = 5.54; SD = 1.02). This is followed by discretionary skills (M = 14.08; SD = 2.98) and decision authority (M = 17.5; SD = 3.23). Furthermore, the highest level of reward was observed (M = 11.95; SD = 1.77). Regarding the prevalence of pathologies, 78 participants exhibited pathologies, of which 51 were musculoskeletal.

The final cluster, Motivated & Stressed, in terms of socio-demographic characteristics, appears to be the oldest of all (M = 46.5; SD = 9.18), yet with a comparable tenure in employment to cluster 1 (M = 19.7; SD = 8.4). Similarly, Cluster 2 also comprises a small number of individuals in white-collar roles (n = 10). With respect to physical demands and cognitive questions, this group demonstrates average scores in comparison to the other two clusters (physical demands: M = 10.3, SD = 3.22; cognitive questions: M = 12.86; SD = 0.75). The two dimensions of decision latitude (M = 4.96; SD = 1.28) exhibit a similar pattern to the previous variables, occupying an intermediate position (discretionary skill: M = 12.3; SD = 2.55; decision authority: M = 15.55; SD = 3.17). This is also the case with regard to recognition (M = 10.47; SD = 2.28). With regard to the pathologies present, 58 workers were found to have one or more pathologies, 29 of which were musculoskeletal.

The validity of the partition and its correlates was evaluated through the application of F-tests, the results of which, as illustrated in Table 4, were all statistically significant, with the exception of the cognitive questions.

Table 4.

Validity of partition.

The cluster analysis successfully identified three distinct and theoretically meaningful profiles of workers. The F-test results validate the distinctiveness of these clusters across key psychosocial work characteristics. Physical demands (F = 51.41, p < 0.001), discretionary skills (F = 42.95, p < 0.001), decision authority (F = 38.82, p < 0.001), and reward (F = 44.43, p < 0.001) all showed highly significant differences between clusters. While cognitive demands showed substantial variation (F = 30.58), this did not reach statistical significance at the p < 0.001 level, suggesting that cognitive load may be more uniformly distributed across the workforce than physical demands or decision-making autonomy. These findings support the validity of the three-cluster solution and demonstrate that the identified profiles differ meaningfully on theoretically relevant work characteristics.

6. Discussion

The results of this study provide a detailed examination of the relationships between key work-related variables, including work engagement, emotional exhaustion and work ability, and how they cluster into different employee profiles. The correlation analysis (Table 2) shows that work engagement is positively correlated with work ability and negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion, supporting the theory that higher engagement leads to greater work ability and less burnout. However, an examination of the data within our clusters reveals that in two of the clusters (1 Disillusioned; 3 Motivated & Stressed), despite equivalent levels of emotional exhaustion, work engagement is observed to be low (M = 19.04) in the first cluster and medium–high (M = 41.92) in the third cluster. In addition, those with higher levels of engagement tend to have better job performance, highlighting the importance of fostering an engaged workforce to prevent burnout and maintain productivity.

The cluster analysis (Figure 1 and Table 3) provides a more detailed view of employee profiles by grouping participants according to their levels of work engagement, emotional exhaustion and work ability. The three clusters, Disillusioned, Motivated & Healthy and Motivated & Stressed, reveal different combinations of these variables and provide insight into the psychosocial characteristics of employees within these profiles:

The Disillusioned cluster (Cluster 1), comprising 22.2% of the sample, shows very low work engagement, high emotional exhaustion and mediocre work ability. These individuals are predominantly blue-collar workers with high physical and cognitive demands and low levels of decision latitude and rewards. The high emotional exhaustion may be a consequence of these demands, coupled with limited control over their work. This group also reports a significant number of musculoskeletal disorders, which may further reduce work capacity and exacerbate emotional exhaustion.

This profile aligns with research on the Job Demand-Control-Support model [57], which posits that high job demands combined with low decision latitude create “high-strain” jobs associated with adverse health outcomes. Studies in manufacturing contexts have similarly identified subgroups of workers experiencing this problematic combination of high demands and low resources [13]. The exclusively blue-collar composition of this cluster is particularly concerning, as it suggests systematic differences in working conditions between occupational groups within the same organization. Research on occupational health inequalities has documented similar patterns, with manual workers experiencing disproportionate exposure to physical hazards and limited access to job resources compared to non-manual workers [36,38].

The high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in this group is consistent with international evidence linking job strain to MSD development [35]. The combination of physical demands, repetitive tasks, and limited control over work methods creates biomechanical stress while simultaneously reducing workers’ ability to modify their work practices to prevent injury [34]. Furthermore, the low reward levels in this cluster may reflect limited opportunities for skill development, career advancement, or recognition, which are known protective factors against burnout in blue-collar populations [52].

In Cluster 2, Motivated & Healthy, the largest cluster (45.3%), these participants have high work engagement, low emotional exhaustion and good work ability. This group is characterised by lower physical and cognitive demands and the highest levels of decision latitude and rewards. They also have fewer musculoskeletal disorders than Cluster 1. The combination of lower job demands, greater decision-making autonomy and greater rewards is likely to contribute to the high engagement and overall well-being of this group.

This profile exemplifies the “active job” configuration described in the Job Demand-Control model, where adequate demands are paired with high control, fostering learning, motivation, and well-being [57]. The presence of both blue-collar and white-collar workers in this cluster suggests that positive well-being outcomes are achievable across occupational categories when favorable working conditions exist. Research on work engagement has consistently demonstrated that job resources (such as autonomy, rewards, and manageable demands) are primary antecedents of engagement [12,16].

The lower prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in this cluster, despite the presence of manufacturing workers, suggests that moderate physical demands combined with autonomy may be less injurious than high demands with low control. This finding aligns with research showing that job control can moderate the relationship between physical demands and health outcomes [58]. Additionally, the younger average age and shorter tenure of this group may contribute to better work ability, though the favorable working conditions likely play a substantial protective role [26].

The final cluster, Motivated & Stressed, which represents 32.5% of the sample, shows moderate work engagement, high emotional exhaustion and mediocre work ability. Their emotional exhaustion levels are similar to those of the Disillusioned cluster, but they maintain a higher level of engagement. Physical and cognitive demands and decision latitude are intermediate compared to the other clusters. This group also reports a significant number of musculoskeletal disorders, suggesting that although they are still somewhat engaged, the stress may be taking a toll on their physical health and ability to work.

This paradoxical profile, characterized by both engagement and exhaustion, has been identified in previous research as a “burning bright” or “overextended” pattern [59,60]. Workers in this configuration may be highly motivated and committed to their work, yet simultaneously experiencing chronic stress and resource depletion. This pattern is particularly concerning as it may represent a transitional state toward burnout if working conditions do not improve [22].

The intermediate levels of job resources and demands in this cluster suggest that these workers may be operating at the limits of their capacity. While they possess sufficient motivation and some degree of autonomy to maintain engagement, the accumulated stress may be gradually eroding their work ability. The older average age of this cluster, combined with long tenure, may indicate that years of exposure to moderate-to-high demands are taking a cumulative toll on health, particularly manifested in musculoskeletal problems [32]. This aligns with life-course perspectives on occupational health, which emphasize the cumulative effects of working conditions over time [58].

Moreover, the high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among the clusters, particularly in the ‘Disillusioned’ group, highlights the necessity for targeted interventions in the manufacturing sector. The relationship between job dissatisfaction, high work demands and the development of MSDs is well documented, indicating the urgent need for organisations to address ergonomic and psychosocial factors to improve worker health [41]. The present study’s focus on these issues is timely, given the growing recognition of the importance of employee well-being in sustaining productivity and reducing absenteeism.

From an industrial safety perspective, these findings have important implications beyond traditional safety management approaches. While conventional occupational safety programs in manufacturing focus primarily on hazard elimination and personal protective equipment, this study demonstrates that psychosocial factors play a crucial role in worker health outcomes [61]. The cluster profiles suggest that safety interventions should be differentiated: the Disillusioned group requires immediate attention to reduce physical demands and increase job control, while the Motivated & Stressed group may benefit from workload management and stress reduction programs despite maintaining productivity.

Regarding international generalizability, several factors should be considered. The Italian manufacturing context is characterized by specific features—predominance of SMEs, family ownership structures, strong labor protections, and Mediterranean work cultures—that may influence the manifestation of well-being profiles [1]. However, the fundamental mechanisms linking job demands, resources, engagement, and health appear to operate similarly across international contexts, as evidenced by research in Nordic [13], North American [17], and Asian manufacturing settings [4].

The three-cluster structure identified in this study resembles patterns observed in other national contexts, suggesting some degree of universality in well-being profiles [60]. Nevertheless, the specific thresholds, prevalence rates, and demographic characteristics of each cluster may vary across countries due to differences in labor regulations, workplace cultures, economic conditions, and social safety nets. Future cross-national research could illuminate which aspects of these profiles are universal versus culturally specific.

An important finding emerging from this study concerns the differential distribution of blue-collar and white-collar workers across clusters. The Disillusioned cluster consisted exclusively of blue-collar workers, while both the Motivated & Healthy and Motivated & Stressed clusters included mixtures of blue-collar and white-collar employees. This pattern suggests systematic occupational inequalities in working conditions and well-being outcomes within the manufacturing context.

Research on occupational health inequalities has consistently documented that manual workers face greater exposure to physical hazards, lower job control, and fewer advancement opportunities compared to non-manual workers [38]. These structural differences in work organization may explain why no white-collar workers were classified in the most disadvantaged profile. However, the presence of blue-collar workers in the Motivated & Healthy cluster demonstrates that positive outcomes are achievable for manual workers when favorable working conditions exist—particularly adequate decision latitude, fair rewards, and manageable physical demands.

These findings align with social determinants of health frameworks, which emphasize that health inequalities often reflect unequal distribution of resources and opportunities across occupational categories [36]. From an organizational justice perspective, the concentration of blue-collar workers in the Disillusioned cluster raises questions about equity in how job demands and resources are distributed within the organization. Interventions aimed at improving well-being should address these structural inequalities rather than focusing solely on individual-level factors.

The F-test results (Table 4) validate the cluster distinctions and confirm that the clusters differ significantly on several key variables, such as physical demands, decision latitude and rewards, all of which are related to work engagement and emotional exhaustion. However, cognitive demands did not differ significantly between clusters, suggesting that cognitive aspects of work may not be as influential in determining cluster membership as physical demands, decision autonomy or reward systems.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several notable strengths. First, it employs a person-centered analytical approach that identifies naturally occurring profiles rather than examining variables in isolation, providing a more holistic understanding of worker well-being [43]. Second, the study achieved a high response rate (89.7%), minimizing potential selection bias and enhancing generalizability to the target population. Third, the integration of multiple well-being indicators (engagement, exhaustion, work ability) alongside comprehensive psychosocial work characteristics provides a rich, multidimensional assessment. Fourth, the focus on an understudied population—Italian manufacturing workers—addresses an important gap in the occupational health literature.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the relationships between working conditions and well-being outcomes. Longitudinal research is needed to establish temporal precedence and examine whether cluster membership changes over time in response to workplace interventions or life transitions. Second, the study relied on a single manufacturing facility in northern Italy, which may limit generalizability to other manufacturing sectors, organizational sizes, or geographic regions. The specific characteristics of seal ring production may not fully represent the broader manufacturing industry.

Third, all measures except pathology data were based on self-report, introducing potential common method bias. Future research could incorporate objective measures of working conditions, observational data, or supervisor ratings to complement self-reports. Fourth, while the sample size was adequate for cluster analysis, the relatively small numbers in some subgroups (e.g., white-collar workers in Cluster 3) limit the precision of some comparisons. Finally, the study did not examine all potentially relevant factors, such as leadership quality, social support from colleagues, or work–family balance, which might further differentiate cluster profiles.

7. Conclusions

This study reveals the importance of fostering work engagement to improve employee well-being and performance. It found that higher levels of work engagement are linked to better work ability and less emotional exhaustion. Employees who are more engaged are more likely to maintain high work ability, which protects against exhaustion and reduced productivity.

Cluster analysis reveals different profiles of employees based on variables like engagement, exhaustion, and ability. These profiles are shaped by specific work characteristics that significantly influence work experiences and health outcomes. The disillusioned group is vulnerable due to high demands, low autonomy and rewards.

The Motivated & Healthy group benefits from high engagement, low exhaustion and good work ability. The Motivated & Stressed group is moderately engaged but highly exhausted. The Disillusioned group is particularly vulnerable due to high demands and low rewards.

The study shows that work factors influence employee engagement, exhaustion and work ability. Interventions reducing job demands, increasing decision-making autonomy and improving rewards may help employees at risk of burnout. These findings can inform organisational strategies to improve workforce health and productivity.

The research findings indicate that organisations should prioritise the enhancement of work resources, such as decision latitude and support systems, to promote engagement and mitigate the negative effects of work demands.

From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that organizational interventions should move beyond one-size-fits-all approaches and instead be tailored to the specific needs of different worker profiles. In particular, workers in the Disillusioned profile require urgent action to reduce excessive physical demands and increase job control, while those in the Motivated & Stressed profile may benefit from targeted stress management and workload optimization to prevent further deterioration. The overrepresentation of blue-collar workers in the most disadvantaged profile also points to the need for greater organizational attention to occupational inequalities, ensuring a more equitable distribution of job demands and resources.

Although this study was conducted in a single Italian manufacturing plant, the identified well-being profiles and their associations with psychosocial working conditions are likely to extend beyond this specific context. Core mechanisms linking job demands, control, rewards, engagement, and health have been consistently documented across sectors and countries [12,16]. Nevertheless, the prevalence of each profile and the most effective intervention strategies may vary according to industrial sector, organizational characteristics, and national and cultural contexts.

Future research should build on these findings by examining manufacturing and other under-researched sectors using longitudinal and cross-national designs, in order to clarify causal pathways and assess intervention effectiveness. Particular attention should be paid to identifying protective factors that allow some blue-collar workers to maintain high levels of well-being despite demanding working conditions.

Overall, this study underscores the value of person-centered approaches in occupational health research and highlights the importance of designing targeted, context-sensitive interventions to promote sustainable well-being and work ability in manufacturing populations.

It is recommended that future research should continue to explore these dynamics, particularly in under-researched areas, in order to develop comprehensive strategies to promote employee well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization D.C., S.V. and G.B.; Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology: S.V. and G.B.; Project administration: D.C. and S.V.; Writing—original draft: G.B.; Writing—review and editing: G.B., S.V., G.G., I.S. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Scientific principles and privacy were strictly observed when conducting the survey. The research protocol was developed in accordance with Italian Law 101/2018 on the protection of privacy at work, in compliance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the University of Turin (protocol no. 0432977, approved 21 July 2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets associated with the present study are available upon request of interested researchers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ISTAT. Censimento Permanente Delle Imprese 2023: Primi Risultati. 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/censimento-permanente-delle-imprese-2023-primi-risultati/ (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- European Commission. Annual Report on European SMEs 2022/2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023.

- Schaufeli, W.B. The future of occupational health psychology. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 53, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ramos, A.; Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Relationship between occupational stress and burnout among Chinese teachers: A cross-sectional survey in Liaoning, China. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2015, 88, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsbergis, P.A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Fujishiro, K.; Baron, S.; Kaufman, J.D.; Meyer, J.D.; Koutsouras, G.; Shimbo, D.; Shrager, S.M.; Stukovsky, K.H.; et al. Job strain, occupational category, systolic blood pressure, and hypertension prevalence. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, E.; Bourgault, P.; Lavoie, S. Association between job strain, mental health and empathy among intensive care nurses. Nurs. Crit. Care 2016, 21, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, V.; Turnell, A.; Butow, P.; Juraskova, I.; Kirsten, L.; Wiener, L.; Patetnaude, A.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.; Grassi, L.; on behalf of the IPOS Research Committee. Burnout among psychosocial oncologists: An application and extension of the effort–reward imbalance model. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, D.E.; Boice, J.D., Jr.; Fryzek, J.P.; Morrison, J.A.; Sadler, C.J.; McLaughlin, J.K. Exposure assessment for a large epidemiological study of aircraft manufacturing workers. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2000, 15, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 2017, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, J.M.; Montesa, D.; Soriano, A.; Kozusznik, M.W.; Villajos, E.; Magdaleno, J.; Djourova, N.P.; Ayala, Y. Revisiting the Happy-Productive Worker Thesis from a Eudaimonic Perspective: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaerts, R.; Tassignon, B.; Ghillebert, J.; Serrien, B.; De Bock, S.; Ampe, T.; Makrini, I.E.; Vanderborght, B.; Meeusen, R.; Pauw, K.D. Prevalence and incidence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in secondary industries of 21st century Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work Stress 2008, 22, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 2009, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, N.; Giorgi, G.; Cupelli, V.; Gioffrè, P.A.; Rosati, M.V.; Tomei, F.; Tomei, G.; Breso-Esteve, E.; Arcangeli, G. Work-related stress assessment in a population of Italian workers: The Stress Questionnaire. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cadiz, D.M.; Brady, G.; Rineer, J.R.; Truxillo, D.M. A review and synthesis of the work ability literature. Work. Aging Retire. 2019, 5, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Enzmann, D. The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice: A Critical Analysis; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Werk en welbevinden: Naar een positieve benadering in de Arbeids-en Gezondheidspsychologie. Gedrag Organ. 2001, 14, 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- González-Romá, V.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Lloret, S. Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.J.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Den Ouden, M. Work-home interference among newspaper managers: Its relationship with burnout and engagement. Anxiety Stress Coping 2003, 16, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 2nd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martinez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, J.; Tuomi, K.; Klockars, M. Changes in the work ability of active employees over an 11-year period. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1997, 23, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, K.; Huuhtanen, P.; Nykyri, E.; Ilmarinen, J. Promotion of work ability, the quality of work and retirement. Occup. Med. 2001, 51, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.M.; Borges, F.N.d.S.; Rotenberg, L.; Latorre, M.D.R.D.d.O.; Soares, N.S.; Rosa, P.L.F.S.; Teixeira, L.R.; Nagai, R.; Steluti, J.; Landsbergis, P. Work ability of health care shift workers: What matters? Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjonen, T. Perceived work ability of home care workers in relation to individual and work-related factors in different age groups. Occup. Med. 2001, 51, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, K.; Eskelinen, L.; Toikkanen, J.; Järvinen, E.; Ilmarinen, J.; Klockars, M. Work load and individual factors affecting work ability among aging municipal employees. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1991, 17, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tuomi, K.; Toikkanen, J.; Eskelinen, L.; Backman, A.L.; Ilmarinen, J.; Järvinen, E.; Klockars, M. Mortality, disability and changes in occupation among aging municipal employees. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1991, 17, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bacci, G.; Viotti, S.; Guidetti, G.; Sottimano, I.; Simondi, G.; Caligaris, M.; Converso, D. Work ability and ageing among blue-collar workers: The role of work and individual characteristics. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 10–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Das, D.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, M. A systematic review of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among handicraft workers engaged in hand-intensive tasks. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2020, 26, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Vasanthan, L.; Standen, M.; Kuisma, R.; Paungmali, A.; Pirunsan, U.; Sitilertpisan, P. Musculoskeletal disorders and psychosocial risk factors among professional drivers: A systematic review. Hum. Factors 2023, 65, 62–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, S.M.; Smit, D.J.; Hutting, N.; van Lankveld, W.; Engels, J.; Reneman, M.; Pelgrim, T.; Staal, J.B. Facilitators and barriers for implementing interventions to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2024, 34, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karran, E.L.; Grant, A.R.; Moseley, G.L. Low back pain and the social determinants of health: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Pain 2020, 161, 2476–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, A.; Wirth, T.; Verhamme, M.; Nienhaus, A. Musculoskeletal health, work-related risk factors and preventive measures in hairdressing: A scoping review. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieker, A.C.; IJzelenberg, W.; Proper, K.I.; Burdorf, A.; Ket, J.C.; van der Beek, A.J.; Hulsegge, G. The contribution of work and lifestyle factors to socioeconomic inequalities in self-rated health: A systematic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2019, 45, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vilsteren, M.; van Oostrom, S.H.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Franche, R.L.; Boot, C.R.L.; Anema, J.R. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD006955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gulden, J. Handboek arbeid & gezondheid: Een rijke bron van informatie. TBV Tijdschr. Bedr. Verzekeringsgeneeskd. 2019, 27, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Formann, A.K. Die Latent-Class-Analyse: Einführung in Theorie und Anwendung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy, J.; Buick, D.; Hankins, M.; Weinman, J.; Horne, R. The use and reporting of cluster analysis in health psychology: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.J.S.; Bujacz, A.; Gagné, M. Person-centered methodologies in the organizational sciences: Introduction to the feature topic. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 21, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Morin, A.J.S. A person-centered approach to commitment research: Theory, research, and methodology. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 584–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hanges, P.J. Latent class procedures: Applications to organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 2011, 14, 24–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrica, R.; Marsella, L. Legge 5 febbraio 1992 n. 104: Legge quadro per l’assistenza, l’integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate. In Medicina Legale; Minerva Medica: Torino, Italy, 2005; pp. 765–769. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, K.; Ilmarinen, J.; Jahkola, A.; Katajarinne, L.; Tulkki, A. Work Ability Index, 19th ed.; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health: Helsinki, Finland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9): A cross-cultural analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R.; Brisson, C.; Kawakami, N.; Houtman, I.; Bongers, P.; Amick, B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Starke, D.; Chandola, T.; Godin, I.; Marmot, M.; Niedhammer, I.; Peter, R. The measurement of effort--reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooi, E.; Sarstedt, M. A Concise Guide to Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarström, A.; Aronsson, G.; Träskman Bendz, L.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, J.; Ivcevic, Z.; White, A.E.; Menges, J.I.; Brackett, M.A. Highly engaged but burned out: Intra-individual profiles in the US workforce. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Feldt, T.; Kinnunen, U.; Mauno, S. The longitudinal development of employee well-being: A systematic review. Work Stress 2013, 27, 46–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Fernández-Cano, M.; Feijoo-Cid, M.; Serrano, C.; Navarro, A. Psychosocial health outcomes among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.