Abstract

This study investigates safety management and risk prevention on Mount Olympus, Greece, focusing on challenges having an impact on visitors and professionals operating in the area. The research is grounded in theories of safety, risk management, and sustainable tourism in mountain environments. A mixed qualitative methodology was applied, including a review of secondary literature, ten semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, and data triangulation. Results show that, although major trails are well-marked, deficiencies persist in permanent rescue infrastructure, technological support, visitor education, and coordinated communication. Stakeholder collaboration remains fragmented, and the implementation of innovative technologies is limited. The study recommends enhancing inter-agency cooperation, adopting technological tools such as navigation and early warning systems, and promoting active community participation. Overall, the findings highlight the necessity of an integrated safety framework that combines prevention, preparedness, and education to ensure the sustainable development of Mount Olympus as a safe and high-quality outdoor tourism destination.

1. Introduction

The concept of safety has gained increasing significance within the field of mountain tourism, where the interaction between humans and natural environments inherently involves multiple risks [1]. Effective risk management in such contexts requires multidimensional interventions—organizational, technological, and educational [2]. Mount Olympus, one of Greece’s most iconic national parks, attracts many a visitor annually but faces diverse risks related to weather conditions, accessibility, infrastructure, and the adequacy of rescue mechanisms [3]. Understanding the parameters influencing safety in this sensitive environment is therefore essential for designing efficient prevention and management strategies.

In this study, mountain tourism is understood as organized and non-organized recreational and leisure activities conducted in mountain environments, including hiking, mountaineering, climbing, and nature-based visitation, undertaken by both amateur visitors and trained professionals within a tourism system [1,4]. Risk refers to the probability and potential severity of adverse events resulting from the interaction of natural risks, human behavior, and organizational conditions, whereas hazard denotes the physical or environmental source of potential harm [5]. Safety management is defined as the coordinated set of preventive, preparedness, response, and recovery measures implemented by institutions and stakeholders to reduce risk exposure and consequences [2]. Within this framework, sustainability refers specifically to the long-term capacity of the mountain system to support visitor use while maintaining ecological integrity, institutional effectiveness, and acceptable safety standards.

This study offers significant scientific value by combining theoretical analysis with empirical findings to assess and improve safety management and risk prevention practices on Mount Olympus. It extends existing literature through a systematic comparison between local practices and international standards, aiming to identify weaknesses that heighten exposure to risks [4]. The interdisciplinary approach adopted in this study reflects the systemic nature of safety in mountain tourism, where environmental risks, visitor behavior, institutional governance, and technological systems interact. By integrating perspectives from environmental sciences, tourism studies, governance, and safety management, the analysis captures the multi-layered processes through which risk is produced and managed in the Mount Olympus context. The study’s contribution also lies in the development of a model for revising and upgrading current practices by identifying both weaknesses and strengths that could inform future improvements [6].

Moreover, the research contributes new empirical insights regarding the implementation of international safety standards and underscores the importance of continuous education and adaptation in the context of sustainable mountain tourism [7]. The purpose is to provide an integrated theoretical and empirical foundation that can inform policy-making and practical interventions for safeguarding both natural ecosystems and human activity in high-risk mountain environments such as Mount Olympus.

The study focuses on safety management and risk prevention in the Mount Olympus area within the context of mountain tourism rather than solely mountaineering or individual recreation. This framing is adopted because Mount Olympus functions as a complex tourism destination that integrates protected natural landscapes, organized infrastructure (trails, refuges), institutional governance, and diverse user groups with varying levels of experience. As such, safety outcomes are shaped not only by individual behavior but also by tourism planning, visitor flows, institutional coordination, and information systems. Examining Olympus through a tourism lens allows the analysis to address systemic risk-management mechanisms rather than isolated accident causes. In this context, visitors refer to non-professional users of the mountain (e.g., hikers, recreational climbers, tourists), while professionals include mountain guides, rescue personnel, refuge operators, park managers, and other stakeholders whose roles directly influence safety management and emergency response.

Given the dual exposure of visitors and professionals to mountain risks—and the interdependence between user behavior and institutional response—effective safety management requires understanding both experiential and organizational dimensions of risk. Accordingly, this study adopts a dual focus on visitors and professionals in order to capture how risk is perceived, managed, and mitigated across multiple levels of the Mount Olympus tourism system. As this study follows a qualitative and exploratory design, the following hypotheses are treated as analytical propositions intended to guide comparative interpretation rather than as statistically testable statements.

1.1. Research Questions and Analytical Propositions

1.1.1. Research Purpose

The overarching purpose of this study is to examine how safety management and risk prevention are organized, perceived, and implemented in the Mount Olympus mountain tourism system, and to assess how international best practices can inform context-sensitive improvements. Specifically, the study aims

- To identify and categorize the main types of risks faced by visitors and professionals on Mount Olympus and to situate these risks in a comparative European mountain context.

- To analyze and evaluate existing safety management and risk prevention practices on Mount Olympus in relation to international standards and governance models.

- To assess the potential for improving current infrastructures and institutional arrangements through the selective adaptation of safety management frameworks applied in other mountain regions, such as the Alps, Pyrenees, and Carpathians.

- To examine the feasibility of transferring international best practices and technological innovations to the Greek context, taking into account local environmental, institutional, and socio-cultural constraints.

- To contribute to the development of an integrated safety management framework that combines prevention, preparedness, and education in support of sustainable mountain tourism.

1.1.2. Research Questions

In line with the exploratory and qualitative design of the study, the following research questions guide the analysis:

- RQ1.

- What types of natural, human-induced, and organizational risks are encountered by visitors and professionals on Mount Olympus, and how do these risks compare with those documented in other European mountain regions?

- RQ2.

- How are safety management and risk prevention currently organized and implemented on Mount Olympus, and to what extent do these practices align with international standards and models?

- RQ3.

- What structural, institutional, and operational gaps can be identified in the existing safety management system on Mount Olympus?

- RQ4.

- Which elements of international safety management and risk prevention frameworks are perceived by stakeholders as transferable and relevant to the Mount Olympus context?

1.1.3. Analytical Propositions

Rather than statistically testable hypotheses, this qualitative study advances the following analytical propositions, which structure the comparative interpretation of findings:

- AP1.

- The risk profile of Mount Olympus reflects a distinctive combination of high natural hazard exposure, seasonal overcrowding, and infrastructural limitations, differentiating it from other European mountain regions.

- AP2.

- Existing safety management and risk prevention practices on Mount Olympus exhibit partial misalignment with international standards, primarily due to fragmented institutional coordination and limited systematic communication among stakeholders.

- AP3.

- The selective adaptation of international safety management components—such as permanent rescue capacity, interoperable communication systems, and real-time risk information platforms—has the potential to significantly enhance functional coordination and overall safety performance on Mount Olympus.

- AP4.

- International best practices and technological innovations can be effectively adapted to the Greek context when implementation strategies are tailored to local environmental conditions, governance structures, and social acceptability constraints.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Risk in Mountain Tourism

This section incorporates how risk is conceptualized in mountain tourism research, emphasizing the interaction between environmental risks, human factors, and institutional capacity. Risk is a critical parameter of outdoor activities, particularly in mountain tourism, where natural, technical, and human factors interact dynamically [1]. On Mount Olympus and similar settings, safety challenges extend beyond physical risks—such as rapid weather shifts or accidents on difficult trails—to organizational deficits, including the absence of permanent rescue services and limited access to timely, accurate information [8]. International literature emphasizes on preventive risk management grounded in technological innovation, strengthened partnerships, and preparedness planning [2,9]. In mountain regions specifically, incorporating local knowledge and fostering cross-sector collaboration are core components of effective prevention [4,10]. This review incorporates theoretical and applied models of safety, prevention, and sustainable management to establish a comparative baseline for the Olympus case.

Understanding mountain massifs is foundational for evaluating physical characteristics, ecosystems, and socio-political factors. Classic definitions describe mountains as landform assemblages with steep relief, pronounced geomorphology, and often extreme climates. Ref. [11] frames mountain regions as high-biodiversity spaces where geomorphological and natural factors co-exist with human activity, requiring specialized management of natural resources and recreation. Cultural-geographic work adds that mountains are not merely physical entities but also cultural sites shaping community identities [12]. Health-oriented perspectives highlight benefits for physical and mental well-being in high-elevation environments while acknowledging the operational safety constraints posed by harsh conditions [13]. Ecologically, [14] details biodiversity patterns and adaptations to elevation-related stressors (temperature, moisture, insolation), underscoring implications for conservation and visitor management. A symbolic strand views mountains as metaphoric terrains of spiritual and philosophical quest [15]. Together, these perspectives are complementary rather than exclusive, arguing for multidimensional analyses that merge geomorphological, ecological, cultural, social, and psychological dimensions [11,12,13,14,15]. This plural framing supports cross-region comparison within Europe and links local parameters—hypsometry, climatic zones, ecological conditions—to management choices [11,12]. It also integrates the impacts of human use and tourism, including overtourism pressures and socio-economic change [13], reinforcing the need for flexible, dynamic approaches to sustain mountain systems.

2.2. Core Concepts in Safety Management, Risk Prevention, and Best Practice

This section reviews foundational concepts in safety management and risk prevention, highlighting international best practices applicable to mountain tourism systems. Safety management and risk prevention underpin sustainable operation of mountain areas characterized by extreme and unpredictable conditions. A first step is capacity assessment and the setting of operational thresholds for protected landscapes, combining quantitative and qualitative indicators that align visitor use with ecosystem limits [16]. Theoretical foundations of prevention focus on identifying critical points in mountain safety systems and on principles of early warning, rapid response, and holistic cycles linking prevention with recovery [10]. Multi-dimensional risk analysis integrates natural data (geomorphology, climate variability) with human and organizational dimensions [5], arguing for context-sensitive strategies that adapt to local infrastructures and technological opportunities. Contemporary training and simulation—e.g., virtual reality and advanced imaging—can build competence and inter-agency communication without exposing personnel to real danger [17]. Tosum up, effective frameworks are integrative, data-driven, and iterative, institutionalizing continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation while embedding new tools into routine practice [2,9]. This aligns with broader sustainability imperatives, where carrying capacity, ecosystem thresholds, and community needs guide access, infrastructure, and emergency planning [16].

2.3. Mount Olympus

This subsection contextualizes Mount Olympus as a tourism destination by outlining its environmental conditions, visitor use, and safety-related challenges. Mount Olympus is a flagship Greek massif with high visitation, iconic cultural value, and environmental sensitivity. Risks include rapid meteorological change, access constraints, infrastructure limits, and the adequacy of rescue mechanisms [11]. Human physiological responses to cold and hypoxia add a critical layer of risk, underscoring the need for visitor education, preparation, and targeted communication [18]. Risk management must incorporate biodiversity protection and ecosystem integrity into decision-making [8] while leveraging digital tools—monitoring systems, communication applications—to support early warning and coordinated response [18,19]. This positions Olympus as a testbed for integrating conservation goals with visitor safety and multi-agency operations.

The Mont Blanc region illustrates high-consequence hazards (rockfall, glacier instability) and the role of fine-scale monitoring for prevention [20,21]. Climate change reshapes route stability and geomorphic processes, accelerating erosion and rockfall and requiring updated, adaptive strategies that mainstream climate data into infrastructure planning and route management [21]. Holistic risk governance emphasizes on inter-agency coordination, shared standards, preventive infrastructure (e.g., marked safe corridors), and professionalized rescue networks operating across jurisdictions [22].

At the Pyrenees, steep relief, deep valleys, and hazardous passes produce frequent rockfalls and slope instabilities, exacerbated by abrupt weather changes [23]. Socio-organizational stressors—rising visitation, limited infrastructure in remote areas, and communication gaps among agencies—heighten vulnerability [24]. Blended approaches that combine local knowledge with digital tools (real-time monitoring, mobile applications) and early-warning systems improve emergency response, while continuous training strengthens professional capacity [24,25].

Although generally lower than the Alps or Pyrenees, the Apennines’ complex tectono-geomorphic transitions produce distinctive risk profiles [26]. Land use pressures from agriculture and pastoralism contribute to degradation and erosion, calling for integrated restoration and protective policies. Traditional resource management practices, combined with modern technologies and real-time information systems, inform context-appropriate prevention and adaptive management [26,27].

The Carpathians pronounced tectonics, sharp relief, and altitudinal zonation underpin avalanche and slope failure risks [28]. Effective management combines early warning, preventive planning, and infrastructure retrofits with community-based knowledge and institutional capacity building [28,29]. Sustainable strategies couple technical upgrades with the empowerment of local management bodies to reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience [29].

Scandinavia has cold climate, long winters, and glacial process necessitate advanced monitoring, standardized protocols, and technology-enabled emergency management [30]. GPS, satellite imagery, and sensor networks support situational awareness and risk response, while specialized training programs integrate theoretical instruction with realistic exercises [31,32]. Coordinated governance—linking national agencies, local communities, and international bodies—facilitates knowledge exchange and adoption of proven best practices [30].

2.4. Cross-Cutting Themes, Gaps, and Relevance to Olympus

Across regions, five themes recur: (1) a shift from reactive to preventive systems built on continuous monitoring, early warning, and scenario-based training [10,17]; (2) multi-scalar governance and coordinated communication among park authorities, rescue services, municipalities, and tourism actors [4,22]; (3) contextual adaptation of best practices to local geomorphology, climate, visitation, and institutions [5,9]; (4) integration of local knowledge with technological innovation [25]; and (5) safety strategies aligned with conservation and carrying capacity [8,16]. Noted gaps include limited longitudinal assessments of interventions, interoperability challenges across data and communication platforms, underrepresentation of cultural/psychological dimensions in operational models despite their importance [12,13,15], and insufficient mainstreaming of climate projections into route and infrastructure planning [21,33].

For Mount Olympus, these insights motivate: (1) carrying-capacity-based visitor management and targeted education [16,18,34,35]; (2) sensor- and app-enabled early warning, standardized inter-agency protocols, and continuous drills inspired by Alpine and Scandinavian practice [12,30,32]; and (3) adaptive governance that blends conservation priorities with stakeholder coordination and community engagement [4,6,36].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area: Mount Olympus

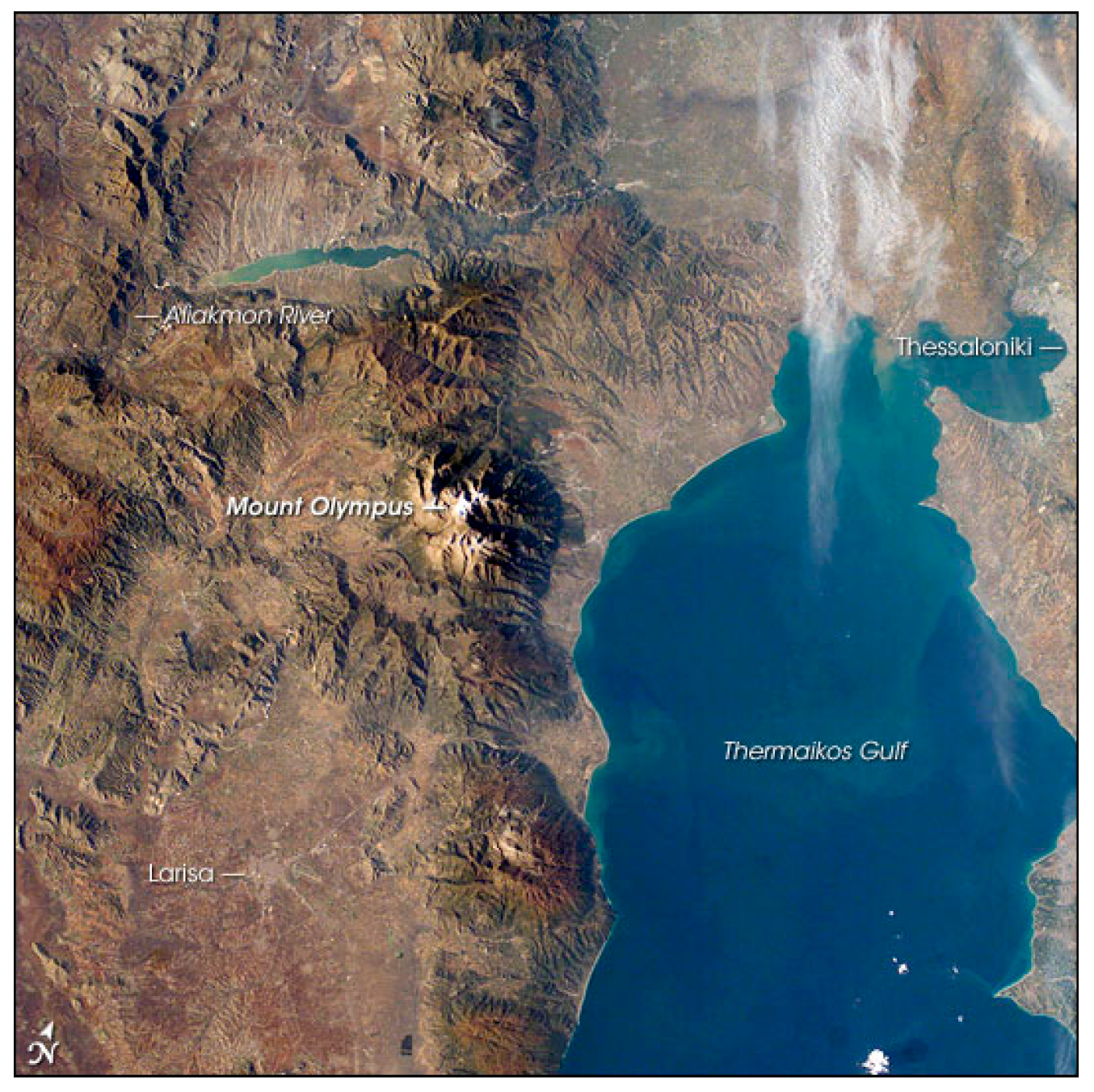

Mount Olympus is located in northern Greece, forming a natural boundary between the regions of Thessaly and Central Macedonia. Rising to 2918 m at Mytikas peak, it is characterized by steep relief, rapid altitudinal variation, and pronounced climatic instability (40.087891690243424, 22.36313835147463) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The mountain is designated as a National Park and Biosphere Reserve, hosting high biodiversity and strong cultural symbolism. Tourism use of Mount Olympus includes hiking, mountaineering, climbing, and nature-based recreation, with strong seasonal variation and peak visitation during summer months. Infrastructure consists of marked trail networks, mountain refuges, and access points concentrated around settlements such as Litochoro. However, the absence of permanent on-site rescue services, variable mobile network coverage, and fragmented institutional responsibilities contribute to heightened safety challenges, particularly during periods of overcrowding or extreme weather. These physical, environmental, and organizational characteristics make Mount Olympus a representative case for examining safety management and risk prevention in mountain tourism destinations.

Figure 1.

Mount Olympus (this file is in the public domain in the United States because it was solely created by NASA. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olympus_NASA.jpg (accessed on 18 January 2026)).

Figure 2.

Map of Greece and spot of Olympus mountain (this file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greece_relief_location_map.jpg (accessed on 18 January 2026)).

3.2. Research Design and Analytical Logic

First, the systematic literature review has been expanded to include explicit reporting of search strings (keywords and Boolean operators), the databases consulted, the time span covered (1990–2024), and clearly operationalized inclusion and exclusion criteria. We now report the number of records retrieved, screened, and included, and we provide a PRISMA-style narrative summary of the review process, along with a brief description of the quality appraisal logic applied to the selected studies (Section 3.3).

Second, the interview methodology has been clarified by specifying recruitment channels, participant role distribution, and interview duration. We explicitly describe the purposive sampling strategy and explain how thematic saturation was assessed. To strengthen credibility and reduce potential bias, we now report reflexive practices adopted during data collection and analysis, including the maintenance of analytic memos and iterative comparison across data sources (Section 3.4).

Third, the field observation protocol has been expanded to specify the observation period, locations (main trails, access routes, and mountain refuges), and the structured recording procedures used, including observation checklists and detailed field notes (Section 3.5).

Fourth, triangulation by the thematic analysis procedure has been substantially elaborated. We now describe the development of an initial codebook informed by the literature, the three-stage coding process (open, axial, and interpretive synthesis), and the validation logic applied through iterative comparison and triangulation across interviews, observations, and literature. While coding was conducted by a single researcher, analytic rigor was enhanced through systematic documentation and transparent category refinement (Section 3.6).

3.3. Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review was conducted to establish the comparative and theoretical foundation of the study. Searches were performed in the Scopus and Web of Science databases, covering peer-reviewed publications from 1990 to 2024. The search strategy combined keywords related to mountain tourism and safety, including “mountain tourism,” “risk management,” “safety management,” “mountain rescue,” “natural risks,” and “sustainable mountain tourism,” using Boolean operators (AND/OR).

Inclusion criteria were (a) peer-reviewed journal articles and academic books, (b) focus on mountain or high-risk natural environments, and (c) explicit relevance to safety, risk prevention, governance, or rescue systems. Exclusion criteria included non-scholarly sources, purely technical engineering studies without tourism relevance, and publications lacking empirical or conceptual contribution.

The review emphasized studies from major European mountain regions (Alps, Pyrenees, Apennines, Carpathians, Scandinavia) to support cross-regional comparison. Findings from the literature were synthesized thematically and used to (1) define analytical categories, (2) benchmark Mount Olympus practices, and (3) inform the interpretation of primary data.

3.4. Semi-Structured Interviews

The semi-structured interview guide was designed to elicit in-depth qualitative insights into safety management, risk perception, and governance on Mount Olympus. It combined optional demographic questions with thematic, open-ended prompts aligned with the study’s research questions and analytical propositions. Demographic items captured participants’ professional background, relationship with Mount Olympus, and length of experience, providing contextual information without compromising anonymity (Table 1). The qualitative questions were organized into six thematic sections. The first explored perceptions of risk, focusing on the types of risks faced by visitors and professionals, seasonal variations in risk exposure, and perceived deficiencies in current safety management. The second addressed infrastructure and risk management practices, examining the adequacy of trails, signage, shelters, rescue facilities, visitor information, and the existence of emergency and prevention plans. The third section investigated the role of local authorities and stakeholder cooperation, with particular emphasis on institutional responsibilities, inter-agency coordination, and community participation in prevention and response. A fourth thematic block examined awareness of international safety management practices and their potential transferability to the Mount Olympus context. The fifth section focused on tourism development and sustainability, probing perceptions of tourism pressure, strategies for balancing visitor use with environmental protection, and the acceptability of access regulation mechanisms such as ticketing or controlled entry systems. Finally, the interviews concluded with reflective questions inviting participants to propose priority measures for improving safety and to articulate their personal vision for the future management, protection, and sustainable development of Mount Olympus. Interviews were audio-recorded with consent, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was reached, meaning no substantively new themes emerged.

Table 1.

Interview participants and professional roles.

3.5. Non-Participant Observation

Non-participant field observation was conducted to document on-site safety conditions and organizational practices during the peak tourist season. Observations took place along main access routes, popular trails, mountain refuges, and visitor entry points on Mount Olympus.

The observation protocol focused on: trail signage and maintenance, availability of safety information, visitor behavior, emergency infrastructure, and visible coordination mechanisms among actors. Field notes were systematically recorded using a structured checklist and reflective memos.

Observation data were not treated as independent evidence but as contextual validation of interview claims and policy statements, supporting the triangulation of findings.

3.6. Data Analysis and Triangulation

Data analysis followed a thematic analysis approach. Interview transcripts and observation notes were coded iteratively using both deductive categories derived from the literature (e.g., risks, infrastructure, coordination, technology) and inductive codes emerging from the data. Coding proceeded in three stages: initial open coding, thematic clustering, and interpretive synthesis.

Triangulation was operationalized by systematically comparing patterns across literature findings, interview data, and observational evidence (Table 2). Convergences strengthened analytical confidence, while divergences were treated as analytically meaningful rather than as inconsistencies. The final themes (T1–T6) reflect this integrative process and directly inform the analytical propositions.

Table 2.

Triangulation of empirical themes and data sources.

As this study follows a qualitative and exploratory design, AP1–AP4 are analytical propositions rather than statistically testable statements. Their purpose is to guide interpretation and to structure the integration of evidence derived from the literature review, semi-structured interviews, and non-participant observation. To enhance analytical transparency, each hypothesis is assessed through systematic triangulation, examining convergence and divergence across data sources. Support for a hypothesis is therefore evaluated qualitatively, based on the consistency, recurrence, and coherence of patterns identified across empirical themes (T1–T6) and international benchmarks drawn from the literature. Table 3 provides a concise mapping of each AP to the corresponding empirical themes, data sources, and evaluative logic used in the analysis.

Table 3.

Analytical Propositions-to-evidence mapping and analytical assessment framework.

4. Results

The results are presented thematically, based on the analysis of interview data and supported by non-participant observations and secondary literature. Six core themes (T1–T6) emerged through the triangulation process, each reflecting a critical dimension of safety management and risk prevention on Mount Olympus. For each theme, empirical findings are illustrated with representative interview excerpts and corroborated, where applicable, by observational evidence.

4.1. Overview

The analysis of ten semi-structured interviews was conducted using a thematic approach to identify the dominant perceptions, experiences, and recommendations of stakeholders involved in risk management on Mount Olympus. Participants included site managers, mountain guides, members of mountaineering associations, local government officials, environmental organization representatives, and researchers. The thematic analysis revealed six central themes (T1–T6), corresponding to the main dimensions of the research questions (Table 4):

Table 4.

Table of the summary of thematic findings (created by authors).

- Geomorphological Features and Natural Hazards;

- Typology of Incidents and Safety Needs;

- Infrastructure and Rescue Mechanisms;

- Cooperation and Institutional Organization;

- Technology and Innovative Tools;

- Improvement Proposals and Adaptation of Good Practices.

Together, these themes provide an integrated understanding of the current challenges, structural gaps, and potential strategies for improving safety and risk prevention in the Olympus region.

4.2. Thematic Analysis of Primary Data

- T1.

- Geomorphological Features and Natural Hazards

All participants identified geomorphological and meteorological conditions as the primary source of risk on Mount Olympus, indicating strong convergence between experiential knowledge and documented hazard profiles. Participants consistently identified the physical and environmental characteristics of Mount Olympus as a primary source of risk. The mountain’s steep relief, unstable rock formations, and sudden weather shifts were described as persistent threats, exacerbated by climate change and heavy rainfall that degrade trails.

“The immediate dangers are natural—rockfalls, lightning strikes, sudden weather changes.” (Participant 3, mountain guide). These perceptions were consistently confirmed during field observation, particularly along high-altitude trails where unstable rock formations, erosion, and limited shelter options were evident during periods of rapid weather change.

Several respondents also noted the seasonal variability of hazards: overcrowding in summer increases exposure, while in winter, severe weather renders many routes inaccessible. These insights highlight the need for seasonal risk mapping and preventive communication systems tailored to visitor patterns.

- T2.

- Typology of Incidents and Safety Needs

The data indicate a clear evolution in the frequency and type of incidents, linked to rising visitation, insufficient visitor education, and accessibility issues. Participants emphasized that unprepared or inexperienced climbers often underestimate terrain difficulty, leading to avoidable emergencies.

“During summer, the risks increase because of overcrowding; in winter, entire routes become impassable due to bad weather.” (Participant 7, environmental scientist). This seasonal differentiation was also evident during observation, where overcrowding on popular summer routes contrasted sharply with restricted access and limited monitoring during winter conditions.

This pattern underscores the importance of graded safety protocols according to difficulty levels, as well as visitor education initiatives and early-warning mechanisms during peak periods. Participants’ accounts suggest that risk exposure on Mount Olympus is not static but fluctuates significantly according to season, visitor density, and preparedness levels, underscoring the need for differentiated, time-sensitive safety protocols rather than uniform preventive measures.

- T3.

- Infrastructure and Rescue Mechanisms

All respondents stressed deficiencies in permanent rescue infrastructure and communication coverage as the most critical weaknesses in Olympus’s safety management framework. Although main trails are generally well-marked, maintenance is inconsistent and first-aid facilities are lacking. There was complete agreement among participants regarding the absence of permanent rescue infrastructure as the most critical operational gap in the current safety system.

“There is no permanent rescue team, nor adequate mobile coverage.” (Participant 3, mountain guide). Observational data corroborated these claims, revealing limited emergency equipment at refuges and inconsistent mobile network coverage along frequently used routes.

Interviewees highlighted the absence of on-site emergency readiness and the decline in volunteer participation. Proposals included a permanent rescue base, an improving interagency coordination during wildfires, and developing operational readiness protocols modeled after international systems such as Air Zermatt.

- T4.

- Cooperation and Institutional Organization

Institutional coordination emerged as a systemic concern across all stakeholder categories, with participants independently describing similar patterns of fragmented responsibility and informal communication. The fragmentation of institutional cooperation emerged as a key systemic issue. Collaboration between stakeholders was described as “informal and episodic,” without a unified risk management body or clear allocation of responsibilities.

“Collaboration exists but it is occasional. We need institutionalized mechanisms and greater community involvement—trail maintenance, training, patrols.” (Participant 4, local government official). No formal coordination mechanism or unified risk-management structure was observed during field visits, reinforcing interviewees’ descriptions of episodic and ad hoc collaboration.

Respondents emphasized on overlapping competencies, limited access to public data, and lack of consistent engagement with NGOs. Several advocated for the creation of a formal risk-management authority or a participatory coordination platform involving local actors and rescue professionals.

- T5.

- Technology and Innovative Tools

Participants consistently framed technology not as a supplementary enhancement but as a missing structural component of preventive safety management on Mount Olympus. Suggested innovations included

- Ground sensors for flood and landslide monitoring;

- Drones for locating missing persons in inaccessible areas;

- Web-based risk platforms providing real-time data;

- Mobile navigation applications with integrated trail maps and QR-coded signage;

- Virtual training programs for rescue personnel.

Notably, none of the proposed tools were observed to be systematically implemented at the time of data collection, indicating a gap between recognized needs and operational adoption.

“An information station in Litochoro and a digital platform with real-time data would make a real difference.” (Participant 4, local government official).

Stakeholders stressed the need for interoperability between digital systems and emergency services, ensuring rapid response and continuous data exchange across agencies.

- T6.

- Improvement Proposals and Adaptation of Good Practices

Improvement proposals emerged inductively from stakeholder narratives rather than being imposed a priori by the researchers. Many referred to successful European models such as Mont Blanc’s crowd-control protocols, the Swiss “Réseau d’Observatoires”, the Air Zermatt professional rescue system, and citizen-based prevention programs (e.g., Norway’s “Mountain Rangers”).

“Air Zermatt or PGHM are examples of professional rescue structures. We need something similar—professional, not just volunteer-based.” (Participant 3, mountain guide). These references indicate that stakeholders draw on comparative knowledge of international models to articulate locally grounded expectations for professionalization and institutional reliability.

Interviewees also called for compulsory visitor registration, mandatory climber education, and the introduction of visitor insurance linked to entrance permits. A recurring vision across interviews was an “intelligent management” model for Olympus—a smart mountain park integrating real-time monitoring, visitor tracking, and continuous evaluation of safety indicators.

“I envision an Olympus with sustainable visitation, technological support, and active community involvement.” (Participant 7, environmental scientist).

The triangulated evidence (literature, interviews, observation) reveals a structurally fragmented safety system on Mount Olympus—marked by adequate physical signage but limited operational integration. Stakeholders converge on the urgency of establishing permanent rescue capacity, digitalized coordination tools, and formal interagency frameworks.

Comparatively, practices from Alpine and Scandinavian contexts highlight the feasibility of integrating technology-driven early warning systems, professional rescue structures, and community engagement models. The findings therefore point to the necessity of transitioning from a reactive to a preventive model, embedding innovation, coordination, and local participation within a sustainable management strategy for Mount Olympus.

Overall, the triangulated findings reveal a structurally fragmented safety management system on Mount Olympus, characterized by adequate physical signage but limited operational integration. Convergence across data sources highlights permanent rescue capacity, coordinated governance, and real-time information systems as the most critical gaps. These empirical patterns form the basis for the comparative interpretation and framework development presented in the Discussion section.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings in Relation to Analytical Propositions

This study set out to examine safety management and risk prevention on Mount Olympus through a qualitative, triangulated approach guided by four analytical propositions (AP1–AP4). The discussion interprets the empirical findings in direct relation to these propositions, drawing on comparative insights from international mountain regions to contextualize the results. Across the European ranges reviewed (Alps, Pyrenees, Apennines, Carpathians, Scandinavia), the literature converges on three pillars of effective mountain-risk governance: (1) prevention-first systems anchored in continuous monitoring and early warning, (2) multi-actor coordination with clear mandates and shared protocols, and (3) adaptive management that internalizes climate variability and local socio-cultural conditions [11,12,13,21,22,30,32]. The Mont Blanc/Alpine model illustrates strong sensor- and data-driven surveillance, integration of climate-change signals into route and infrastructure decisions, and professional rescue capacity [20,21,33]. The Pyrenees literature highlights communication/alerting interoperability for rapidly changing weather in complex terrain [23,24]. The Carpathians emphasize blending local knowledge with modern tools [28,37]. Scandinavian cases demonstrate the dividends of standardized procedures, training ecosystems, and advanced telemetry under harsh climates [30,31].

The findings strongly support Distinctive Risk Profile—AP1, indicating that the risk profile of Mount Olympus reflects a distinctive convergence of natural hazard exposure, seasonal overcrowding, and infrastructural constraints [8,18,19]. While risks such as rockfall, lightning, and rapid weather change are common across European mountain regions, their impacts on Olympus are amplified by fluctuating visitor density, uneven preparedness levels, and limited on-site emergency capacity. This combination differentiates Olympus from more intensively managed mountain systems, such as those in the Alps or Scandinavia, where permanent rescue infrastructure and continuous monitoring moderate similar risks [4,6,16].

Analytical Proposition 2 (Institutional Misalignment) is also strongly supported by the empirical evidence. Both interviews and observation reveal that existing safety management and prevention practices on Mount Olympus remain only partially aligned with international standards. Fragmented institutional responsibilities, informal coordination mechanisms, and limited systematic communication were consistently identified as structural weaknesses. These findings echo international research emphasizing that governance and coordination, rather than hazard presence alone, often determine safety outcomes in mountain environments.

The empirical evidence provides strong support for Potential of Selective Adaptation—AP3, demonstrating that stakeholders perceive the selective adaptation of international safety management components as both necessary and desirable. Participants frequently referenced professional rescue systems, standardized operating procedures, and real-time risk information platforms as missing elements rather than unrealistic ideals. Importantly, these expectations align with documented best practices in Alpine and Scandinavian contexts, suggesting that functional improvement on Olympus does not require novel solutions but rather context-sensitive integration of proven models.

Finally, the findings refine Conditional Transferability—AP4 by underscoring that the transferability of international practices is conditional rather than automatic. While technological tools and organizational models are widely regarded as transferable, their effectiveness depends on alignment with local environmental conditions, legal frameworks, funding structures, and social acceptability. Stakeholder concerns regarding access regulation and visitor fees highlight that technical feasibility alone is insufficient; legitimacy and community engagement are equally critical determinants of successful implementation.

5.2. Mount Olympus in Comparative Perspective

When situated within the broader European mountain context, Mount Olympus exhibits both similarities and critical divergences from other well-studied regions such as the Alps, Pyrenees, Carpathians, and Scandinavian ranges. As in these regions, Olympus is exposed to natural risks including rapid weather changes, rockfall, and seasonal accessibility constraints. However, the findings of this study indicate that the consequences of these risks on Olympus are amplified by structural and organizational limitations rather than by hazard intensity alone.

In contrast to Alpine and Scandinavian mountain systems, where permanent rescue services, standardized operating procedures, and real-time monitoring are integral components of safety governance, Mount Olympus relies predominantly on episodic coordination and volunteer-based response mechanisms. This distinction helps explain why similar hazard profiles translate into higher uncertainty and slower response times in the Olympus context.

Furthermore, while regions such as the Pyrenees and Carpathians face comparable challenges related to remoteness and geomorphological instability, international practice increasingly emphasizes integrated governance and data-driven prevention. The absence of such institutionalized frameworks on Mount Olympus highlights a governance gap rather than a lack of technical knowledge or available models.

Overall, the comparative analysis suggests that Mount Olympus does not represent an exceptional case in terms of environmental risk, but rather a case where internationally recognized safety practices have not yet been systematically embedded into tourism governance structures. This positions Olympus as a highly relevant case for examining how contextual adaptation—rather than direct replication—of international models can enhance safety and sustainability in mountain tourism destinations.

In relation to geomorphology and natural hazards, stakeholders consistently highlighted rockfalls, lightning, sudden weather shifts, and marked seasonal variations as key threats on Mount Olympus. These findings closely reflect international research, which recognizes that the assessment of natural hazard regimes forms the essential foundation of any comprehensive mountain safety strategy [13,14,18].

Regarding incident typologies and safety needs, participants described a clear pattern of seasonal fluctuation—overcrowding and increased accidents during the summer months, and reduced accessibility coupled with heightened risk during winter. Such observations align with previous studies that advocate for dynamic, seasonally adjusted risk mapping, differentiated safety protocols, and structured visitor flow management systems [10,16,36].

When addressing infrastructure and rescue capacity, the interviewees repeatedly emphasized the absence of a permanent rescue team, inconsistent trail maintenance, inadequate first-aid facilities, and gaps in mobile network coverage. These limitations mirror global warnings that operational readiness—encompassing personnel, logistics, and rapid response systems—often determines the difference between minor incidents and major disasters [34,35].

The theme of coordination and governance revealed similar challenges. Stakeholders noted that collaboration among authorities tends to be episodic, with overlapping mandates and restricted data sharing. These findings echo the international literature’s call for institutionalized incident command structures, standardized operating procedures, and recurring joint training exercises among relevant agencies [4,6].

The discussion around technology and innovation underscored the growing interest in applying sensors, drones, real-time monitoring platforms, QR or GIS-linked trail systems, and virtual-reality training tools. Stakeholders’ proposals correspond with global evidence showing that technological interventions can significantly reduce uncertainty—provided they are properly integrated into everyday operations, supported by sufficient training and stable funding [17,38].

Finally, the theme of improvement and best-practice transfer reflected a strong appetite for adopting proven international models while adapting them to local realities. Many participants referred to the Alpine-style professional rescue services such as Air Zermatt or the French PGHM, as well as citizen-based initiatives like the Mountain Rangers or the California Conservation Corps. Their comments confirm the literature’s view that selective and context-sensitive adaptation of best practices is more effective than the wholesale importation of foreign systems [4,16].

Where divergences between theory and practice appear, they are primarily socially grounded. Several stakeholders expressed resistance to the introduction of entry fees or controlled access gates, which they perceived as “taxes” without clear returns to the community. Others pointed out structural limitations—such as insufficient staffing and ambiguous mandates—that could undermine the implementation of otherwise well-designed safety measures. This nuanced feedback underscores the relevance of analyzing the findings through the Suitability–Acceptability–Feasibility (SAF) framework: while many proposals are ecologically suitable and technically feasible, their success ultimately depends on social acceptability, which is shaped by perceptions of fairness, transparency in revenue reinvestment, and genuine community participation in the design of safety policies [39].

5.3. From Fragmentation to Integration: An Olympus-Specific Safety Framework

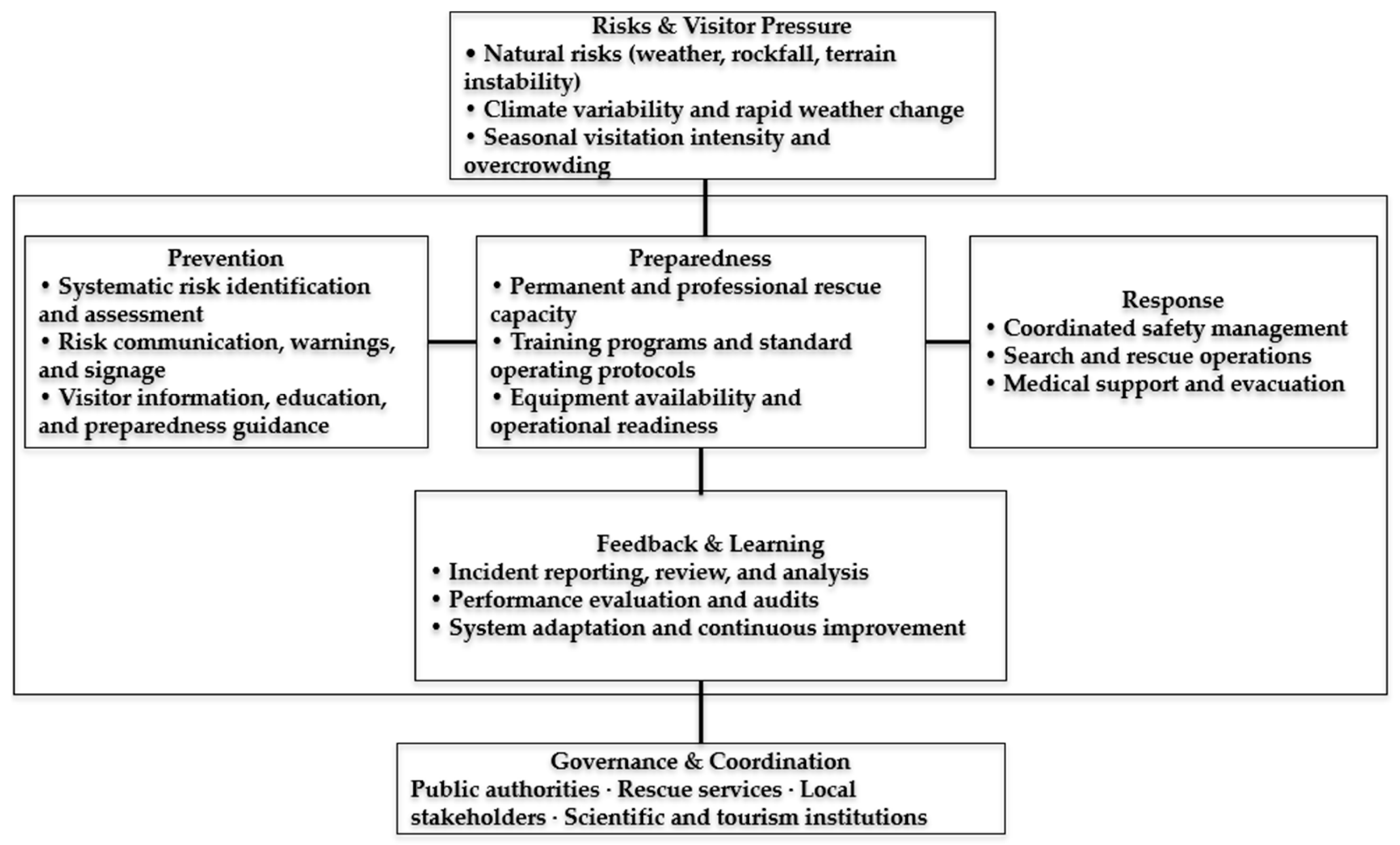

Synthesizing the empirical findings and comparative insights, this study proposes an integrated safety management framework tailored to the Mount Olympus context (Figure 3). The framework conceptualizes safety as a dynamic system structured around three interdependent pillars: prevention, preparedness, and response, embedded within participatory governance.

Figure 3.

Integrated Safety Management Framework for Mount Olympus (created by authors).

Prevention includes continuous hazard monitoring, seasonal risk mapping, visitor education, and real-time information dissemination. Preparedness encompasses permanent rescue capacity, trained personnel, interoperable communication systems, and standardized operating procedures. Response refers to coordinated emergency action supported by clear command structures and technological tools.

These operational components are sustained by cross-sector governance involving park authorities, municipalities, rescue services, tourism actors, and local communities. Feedback loops—through incident analysis, monitoring data, and stakeholder evaluation—enable continuous adaptation and learning. Rather than a static model, the framework represents a flexible structure capable of evolving alongside environmental change and tourism dynamics.

6. Conclusions

This article examined safety management and risk prevention on Mount Olympus through an integrated design that combined theory with primary evidence from ten semi-structured interviews and questionnaires. The synthesis of these strands yielded a multi-faceted picture of current challenges and realistic opportunities for improvement.

Natural hazards remain the dominant risk drivers on Olympus—rockfall, rapid weather shifts, lightning, and difficult terrain—corroborating established work on the biophysical and cultural specificity of mountain environments (e.g., [11,12,13]). Equally critical, however, are time to response and operational readiness: stakeholders repeatedly highlighted the absence of a permanent rescue unit and the insufficiency of visitor information, echoing concerns in [34,40].

Infrastructure analysis showed that, although main trails are generally well signposted, gaps at mountain huts, first-aid capacity, communications coverage, and emergency procedures amplify exposure to natural hazards—consistent with [18,35]. Stakeholders converged on the need for a centralized information hub (physical station in Litochoro plus a digital platform with live updates on weather, trail status, and risk levels), aligning with [4,38].

On governance, interviewees stressed that effective risk response depends on stable, institutionalized collaboration among local authorities, rescue services, clubs, NGOs, and the scientific community—an agenda also advanced by [16,36]. Finally, the transfer of international good practices (e.g., Alpine professional rescue, crowd management, visitor registration/insurance, community ranger programs) is both desirable and feasible, provided those models are adapted to Olympus’s legal, social, and geomorphological context [6,41].

The study underscores a consistent message: Olympus’s risk profile is shaped by high natural hazard exposure compounded by organizational fragmentation, information gaps, and limited permanent response capacity—patterns mirrored in the literature [11,12,18]. Progress therefore hinges on three mutually reinforcing levers: (a) Capabilities (permanent rescue readiness, interoperable communications, equipped huts, trained personnel); (b) Information (real-time, user-centered risk communication and decision support); (c) Coordination (institutionalized, transparent, and participatory governance).

Equally, social acceptance matters: measures such as registration or fees will succeed only if co-designed with communities and clearly reciprocal—that is, visibly financing safety, maintenance, and access improvements. When paired with adapted international practice and modern technology, these conditions can shift Olympus from a reactive to a preventive, learning system.

To sum up, Olympus presents distinctive challenges that demand a multi-disciplinary, adaptive approach. By weaving together theoretical models and empirical insights, this article offers an integrated action framework to enhance safety and risk prevention while safeguarding ecological and cultural assets. The core prescription is not a one-off plan but a continuous cycle of monitoring, co-design, implementation, and review, ensuring strategies keep pace with climatic variability, visitation dynamics, and institutional capacity. Implemented in this spirit, Olympus can evolve into a smart, safe, and sustainable mountain destination—and a transferable reference model for other high-value mountain ecosystems.

7. Implications for Policy and Management

The findings of this study carry direct implications for policy and management in mountain tourism destinations characterized by high symbolic value, environmental sensitivity, and complex governance structures. In the case of Mount Olympus, the results indicate that meaningful improvements in safety and risk prevention require coordinated interventions across operational capacity, information systems, governance arrangements, and social legitimacy. The following recommendations translate the empirical findings into actionable policy and management directions.

A primary implication concerns the strengthening of rescue readiness and emergency infrastructure. The findings highlight the absence of permanent on-site rescue capacity as a critical vulnerability. Addressing this gap requires securing stable funding and personnel for a permanent, professionally staffed rescue unit, ideally co-located with a central risk-monitoring and coordination hub.

In parallel, essential life-saving infrastructure should be systematically upgraded through the placement of automated external defibrillators (AEDs), trauma kits, and first-aid equipment in mountain huts and high-use trail nodes. Clear response time benchmarks should be established for different operational zones to ensure timely intervention during emergencies. Together, these measures would shift the current system from ad hoc response toward institutionalized preparedness.

The study also underscores the central role of information and technology in preventive safety management. A comprehensive monitoring and alert system should be developed using a tiered network of environmental sensors, including rain and stream gauges and rockfall detection devices in critical corridors. When integrated with national meteorological data, these systems could support real-time, color-coded risk levels that enhance situational awareness for both authorities and visitors. Rescue capacity and infrastructure must be strengthened through the establishment of a permanent, professionally staffed rescue base equipped with interoperable communication systems. This facility should be complemented by the systematic placement of first-aid and trauma kits, as well as automated external defibrillators (AEDs), across mountain huts and key trail junctions. The rehabilitation of degraded or erosion-prone trail segments, alongside the deployment of drones and GPS-enabled tools for rapid search and situational awareness, would significantly enhance response efficiency and reduce casualty rates [9,19].

Building on this infrastructure, a unified digital platform (e.g., Olympus SafeTrails) could function as the technological backbone of the safety framework. Such a platform would provide live trail maps, temporary closures, SOS location sharing, offline navigation, and push alerts, while interfacing with QR-coded signage and beacon devices at mountain huts. These tools would reduce informational asymmetries and support informed decision-making before and during mountain activities. The creation of a robust information architecture supports risk awareness and informed decision-making before and during mountain visits. The proposed Olympus Safety Information Station in Litochoro—operating in tandem with a real-time digital platform—would provide continuous updates on weather conditions, trail accessibility, temporary closures, and color-coded risk levels. Incorporating features such as push notifications and offline maps would ensure that visitors receive critical information even in low-connectivity environments, thereby strengthening proactive risk management and individual preparedness [17,42].

From a governance perspective, the findings point to the need for institutionalized coordination mechanisms that move beyond episodic collaboration. Continuous training and inter-agency exercises are essential to sustain operational competence and shared situational awareness. Annual tabletop simulations and field drills—supported by virtual-reality modules simulating scenarios such as rockfall, lightning, or mass-casualty incidents—would strengthen interoperability among rescue services, park authorities, and local actors.

In addition, clear standard operating procedures and defined roles across institutions are necessary to reduce ambiguity during crises. Certifying hut wardens and frontline personnel in enhanced first-response techniques would further extend safety coverage and improve initial response capacity across the mountain.

Finally, the study highlights that the effectiveness of safety interventions depends strongly on social acceptability and perceived legitimacy. Measures such as visitor registration or access regulation should therefore be introduced gradually, beginning with opt-in pilot schemes that offer feedback and tangible incentives. If effective, such systems could evolve into timed or windowed access during peak periods, with any revenues transparently reinvested in trail maintenance, rescue services, and safety infrastructure.

Community engagement is equally critical. Initiatives such as an Olympus Rangers volunteer program could support visitor education, safety patrols, and trail reporting, while youth conservation teams—modeled on international examples—could contribute to maintenance and ecosystem restoration. Citizen-science programs focused on trail erosion and environmental monitoring would further strengthen local stewardship and shared responsibility.

To ensure accountability and learning, these measures should be embedded within a recurring Safety Audit Cycle. Regular dashboards and public reports tracking incident patterns, response times, infrastructure conditions, and visitor satisfaction would support adaptive management and continuous improvement. Through this integrated approach, Mount Olympus can progressively evolve into a model of smart, safe, and socially supported mountain tourism governance. Governance should be formalized through a multi-actor network comprising park services, municipal authorities, fire and forest agencies, rescue organizations, mountaineering clubs, environmental NGOs, and academic institutions. Establishing shared standard operating procedures (SOPs), joint training exercises, and open data-sharing channels would accelerate detection–response loops and promote institutional learning across agencies [4,16].

Moreover, the research underscores the value of adapted international models. Professionalizing the rescue service following the examples of Air Zermatt or the French PGHM—while tailoring these frameworks to Greek legal and financial realities—could elevate operational effectiveness and public confidence. Similarly, the introduction of community stewardship programs and conservation crews modeled on the California Conservation Corps would combine environmental protection with civic engagement. The integration of visitor insurance or registration systems, where socially acceptable, could further enhance accountability and provide sustainable funding mechanisms [21,43].

Finally, promoting sustainable visitation requires careful calibration between accessibility and conservation. Any form of access control or visitor fee must be transparently linked to tangible reinvestments—such as trail maintenance, shuttle services, or first-aid facilities—to ensure public acceptance. By aligning environmental protection with local economic benefits, Olympus can evolve into a model of balanced, community-supported mountain governance [10,16].

Taken together, these implications translate the research findings into a coherent policy agenda for transforming Mount Olympus into a “smart mountain”—one that combines technological innovation, institutional collaboration, and social legitimacy to achieve safety, sustainability, and resilience.

8. Limitations and Future Research

This study’s qualitative design, based on a purposive sample of ten participants, prioritized depth and contextual understanding over statistical generalization. While this approach generated rich insights into stakeholder perceptions and the systemic dynamics shaping safety management on Mount Olympus, the relatively small sample size inevitably limits the representativeness and transferability of the findings. Furthermore, several proposed interventions such as the establishment of a permanent rescue infrastructure, the deployment of digital monitoring systems, and the introduction of structured visitor-management mechanisms—require additional feasibility assessments. These should include cost–benefit analyses, legal and institutional reviews, and controlled pilot testing under real operational conditions to determine their practicality and sustainability.

Building on these findings, future research should adopt multi-method and longitudinal designs capable of evaluating both process and outcome dimensions of risk management initiatives. A key priority is to examine the effectiveness of international models, by implementing and assessing pilot adaptations of Alpine and Pyrenean risk management frameworks within the Greek context. Before-and-after evaluations could provide empirical evidence on their impact and scalability [39,44]. Another crucial avenue involves technology integration, focusing on the performance, reliability, and user adoption of digital tools such as environmental sensors, telemetry networks, VR/AR-based rescue training systems, and decision-support dashboards that enhance both prevention and real-time response capabilities [42,45].

Equally significant is the need to explore social acceptability and governance, particularly how local communities and visitors perceive management interventions such as timed access, registration systems, or dynamic pricing. Future studies should test participatory co-design frameworks aimed at increasing the legitimacy and public trust of such measures, ensuring they are aligned with local cultural norms and expectations [10,21]. In parallel, research on tourism pressure and carrying capacity should quantitatively investigate the interrelationships between visitor density, trail degradation, incident frequency, and ecological integrity. These analyses could support the development of adaptive indicators and management thresholds that balance visitor experience with environmental preservation [16,46].

Finally, forthcoming studies would benefit from integrating climate change projections into trail and infrastructure lifecycle planning, while applying ecological–safety trade-off models that explicitly account for biodiversity protection, visitor access, and rescue efficiency. Such an integrated approach would not only refine theoretical models of mountain risk governance but also produce actionable insights for policy, planning, and long-term sustainability on Mount Olympus and comparable mountain systems.

In conclusion, Mount Olympus’s safety challenges are not unique but structurally solvable through a contextually adapted application of proven international frameworks—combining professional preparedness, interoperable data systems, participatory governance, and visitor flow management tools. Evidence from this study indicates that coupling these measures with visible community reciprocity can simultaneously enhance their suitability, acceptability, and feasibility, moving Olympus toward a resilient, smart, safe, and sustainable mountain destination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and G.Y.; methodology, A.K. and G.Y.; formal analysis, A.K. and G.Y.; investigation, A.K. and G.Y.; resources, A.K., I.T., and O.K.; data curation, A.K. and C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., and G.Y.; writing—review and editing, O.K., and G.Y.; visualization, I.T. and G.Y.; supervision, G.Y.; project administration, G.Y., C.K., and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Democritus University of Thrace (protocol code 31132-202/26 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beedie, P.; Hudson, S. Emergence of mountain-based adventure tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.; Page, S.J. (Eds.) Managing Tourist Health and Safety in the New Millennium; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Botetzagias, I.; Kostopoulos, G. A national park for tourists or mountaineers?: Debating Mount Olympus in inter-war Greece. J. Tour. Hist. 2025, 17, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollo, M.; Wengel, Y. Mountaineering Tourism: A Critical Perspective; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Keiler, M.; Fuchs, S. Vulnerability and exposure to geomorphic hazards: Some insights from the European Alps. In Geomorphology and Society; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Götz, F.M.; Wilson, C.; Volsa, S.; Rentfrow, P.J. A tale of peaks and valleys: Sinusoid relationship patterns between mountainousness and basic human values. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 13, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Choi, H.C.; Jeong, C. Trails of Transformation: Balancing Sustainability, Security, and Culture in DMZ Walking Tourism. Land 2025, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramitsoglou, K.M.; Koudoumakis, P.; Akrivopoulou, S.; Papaevaggelou, R.; Protopapas, A.L. Biodiversity as an outstanding universal value for integrated management of natural and cultural heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacnet, J.M.; Carladous, S.; Sassus, F.; Ripert, E.; Lagleize, P.; Stephan, A.; Calmet, C.; Gil, V. Practical Risk and Resilience Assessment: A Methodology for Implementation of Mountain Risk Management and Prevention Strategy (STePRiM). 2022. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03739844/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Soule, B.; Corneloup, J. Risk management in mountain sports areas: The case of a French ski resort (Val Thorens). J. Sport Tour. 2004, 9, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakrou, A.C. A Study on the Economic Valuation and Management of Recreation at Mount Olympus National Park, Greece. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Della Dora, V. Mountain: Nature and Culture; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N. In the Mountains: The Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Spending Time at Altitude; Hachette: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, C. Mountain biodiversity, its causes and function: An overview. In Mountain Biodiversity; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Evola, J. Meditations on the Peaks: Mountain Climbing as Metaphor for the Spiritual Quest; Simon and Schuster: Rochester, VT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulou, S.; Kyritsis, I. A tourism carrying capacity indicator for protected areas. Anatolia 2006, 17, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harknett, J.; Whitworth, M.; Rust, D.; Krokos, M.; Kearl, M.; Tibaldi, A.; Bonali, F.L.; De Vries, B.V.W.; Antoniou, V.; Nomikou, P.; et al. The use of immersive virtual reality for teaching fieldwork skills in complex structural terrains. J. Struct. Geol. 2022, 163, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsianos, G.I. Human Responses to Cold and Hypoxia: Implications for Mountaineers. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rescue, O.M. Olympic Mountains: A Climbing Guide; The Mountaineers Books: Seattle, WA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Deline, P.; Gardent, M.; Magnin, F.; Ravanel, L. The morphodynamics of the Mont Blanc massif in a changing cryosphere: A comprehensive review. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2012, 94, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, J.; Marcuzzi, M.; Ravanel, L.; Pallandre, F. Effects of climate change on high Alpine mountain environments: Evolution of mountaineering routes in the Mont Blanc massif (Western Alps) over half a century. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2019, 51, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strapazzon, G.; Reisten, O.; Argenone, F.; Zafren, K.; Zen-Ruffinen, G.; Larsen, G.L.; Soteras, I. International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine Consensus Guidelines for on-site management and transport of patients in canyoning incidents. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2018, 29, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, R.; Callado, A. Mountain accidents associated with winter northern flows in the Mediterranean Pyrenees. Tethys 2010, 7, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerín, M.A.; Soteras, I.; Sanz, I.; Egea, P. The “medicalization” of mountain rescue teams: A social and economic approach based on mortality evolution in the central Pyrenees. Arch. Med. Deporte 2019, 35, 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, R.; Moreno, A.; Luetscher, M.; Ezquerro, L.; Delgado-Huertas, A.; Benito, G.; Bartolomé, M. Mitigating flood risk and environmental change in show caves: Key challenges in the management of the Las Güixas cave (Pyrenees, Spain). J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotiadis, A. The Role of Tourism in Rural Development Through a Comparative Analysis of a Greek and a Hungarian Rural Tourism Area. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morata, F.; Roca, D.; Cots Serra, F. A Sustainable Development Strategy for the Pyrenees-Mediterranean Euroregion: Basic Guidelines; Institut Universitari d’Estudis Europeus & Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu, M. Snow avalanche hazards in the Făgăraş massif (Southern Carpathians): Romanian Carpathians—Management and perspectives. Nat. Hazards 2009, 51, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, Z. Evaluating landslide remediation methods used in the Carpathian Mountains, Poland. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2019, 25, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson-Sköld, Y.; Bergman, R.; Johansson, M.; Persson, E.; Nyberg, L. Landslide risk management—A brief overview and example from Sweden of current situation and climate change. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2013, 3, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, T. Information on Recreation and Tourism in Spatial Planning in the Swedish Mountains: Methods and need for Knowledge. Doctoral Dissertation, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch, U.; Knapp, J.; Kreuzer, O.; Ney, L.; Strapazzon, G.; Lischke, V.; Albrecht, R.; Phillips, P.; Rauch, S. Advanced airway management in hoist and longline operations in mountain HEMS—Considerations in austere environments: A narrative review. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2018, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, J.; Lacroix, P.; Duvillard, P.A.; Marsy, G.; Marcer, M.; Malet, E.; Ravanel, L. Multi-method monitoring of rockfall activity along the classic route up Mont Blanc (4809 m a.s.l.) to encourage adaptation by mountaineers. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimakamis, D. Predictions for activity involvement via PERMA well-being model in mountain climbing-hiking participants on Mt. Olympus. Int. J. Recreat. Sports Sci. 2022, 6, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Solomou, A.D.; Martinos, K.; Skoufogianni, E.; Danalatos, N.G. Medicinal and aromatic plants diversity in Greece and their future prospects: A review. Agric. Sci. 2016, 4, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, B.G.D.S.; Savi, M.; Santos, J.F.L.D.; Tetto, A.F.; Paula, E.V.D.; Steiner, P.J. Social and environmental parameters for public use management in mountain ecosystems. Rev. Árvore 2023, 47, e4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, M.; Popescu, F. Management of snow avalanche risk in the ski areas of the Southern Carpathians—Romanian Carpathians: Case study: The Bâlea (Făgăraş Massif) and Sinaia (Bucegi Mountains) ski areas. In Sustainable Development in Mountain Regions: Southeastern Europe; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Doytchev, B. The impact of mountaineering and climbing on the environment. Trakia J. Sci. 2021, 19, 540–545. [Google Scholar]

- Poulaki, P.; Bouzis, S.; Vasilakis, N.; Valeri, M. Hiking tourism in Greece. In Sport and Tourism; Emerald Publishing Ltd.: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimakamis, D.; Komsis, S. Prediction of involvement in activity based on the dimensions of participation in mountaineering and hiking on Mount Olympus. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 22, 2089–2097. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis, D.L. Re-Thinking Mountains: Ascents, Aesthetics, and Environment in Early Modern Europe. Doctoral Dissertation, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Afsharipour, M.; Maghoul, P. Towards education 4.0 in geotechnical engineering using a virtual reality/augmented reality visualization platform. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 2657–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiler, M.; Fuchs, S. Challenges for natural hazard and risk management in mountain regions of Europe. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mourey, J.; Lacroix, P.; Duvillard, P.A.; Marsy, G.; Marcer, M.; Ravanel, L.; Malet, E. Rockfall and vulnerability of mountaineers on the west face of the Aiguille du Goûter (classic route up Mont Blanc, France): An interdisciplinary study. Nat. Hazards Risks Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Havenith, H.B.; Cerfontaine, P.; Mreyen, A.S. How virtual reality can help visualise and assess geohazards. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2019, 12, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, A.; Machín, J.; Soto, J. Assessing soil erosion in a Pyrenean mountain catchment using GIS and fallout 137Cs. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.