Abstract

The integration of artificial intelligence into daily life significantly enhances the autonomy and quality of life of visually impaired individuals. This paper introduces the Visual Impairment Spatial Awareness (VISA) system, designed to holistically assist visually impaired users in indoor activities through a structured, multi-level approach. At the foundational level, the system employs augmented reality (AR) markers for indoor positioning, neural networks for advanced object detection and tracking, and depth information for precise object localization. At the intermediate level, it integrates data from these technologies to aid in complex navigational tasks such as obstacle avoidance and pathfinding. The advanced level synthesizes these capabilities to enhance spatial awareness, enabling users to navigate complex environments and locate specific items. The VISA system exhibits an efficient human–machine interface (HMI), incorporating text-to-speech and speech-to-text technologies for natural and intuitive communication. Evaluations in simulated real-world environments demonstrate that the system allows users to interact naturally and with minimal effort. Our experimental results confirm that the VISA system efficiently assists visually impaired users in indoor navigation, object detection and localization, and label and text recognition, thereby significantly enhancing their spatial awareness and independence.

1. Introduction

According to the Global Vision Database 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators, the year 2020 saw approximately 43.3 million people living with blindness, and another 295 million people experiencing moderate to severe vision impairments. Projections suggest a significant increase by 2050, with the blind population expected to rise to 61.0 million, and those with moderate to severe vision impairments expanding to 474 million individuals [1]. In the United States alone, there were more than one million blind people in the year 2015, and that number is projected to double in the year 2050 [2]. These statistics highlight an escalating global health concern that necessitates immediate attention and action. There can be no overstatement about the importance of vision. It is a fundamental sensory modality that underpins a myriad of daily activities, including but not limited to navigation, fetching objects, reading, and engaging in other complex tasks, all of which are integral to personal independence and quality of life [3,4,5].

While there is no single most important task above all others, navigating indoor spaces poses a unique set of challenges for visually impaired individuals, often complicating what many would consider routine activities [6]. Addressing this task, both individually and collectively, is central to empowering visually impaired individuals to complete not only basic but also complex tasks with greater confidence and autonomy. Even before the advent of computer vision, many methods, tools, and systems were developed to assist the visually impaired in navigation. Some common examples include white canes, guide dogs, and braille. However, without machine vision and AI technologies, these methods were inherently limited. A white cane, for instance, while invaluable for immediate spatial detection, offers a limited range and no identification capabilities [6]. Guide dogs, often considered the best alternative to sighted assistance, offer companionship, increased mobility, and sometimes even higher social status [7,8]. Yet, they come with high training and acquisition costs, making them mostly unavailable for low-income individuals [9]. Also, despite their ability to navigate complex environments, guide dogs cannot communicate specific facility information to their handlers [10]. Braille has revolutionized access to written information for the visually impaired, but it is confined to touching and needs to be printed beforehand, limiting its capacity to deliver immediate and dynamic content [11].

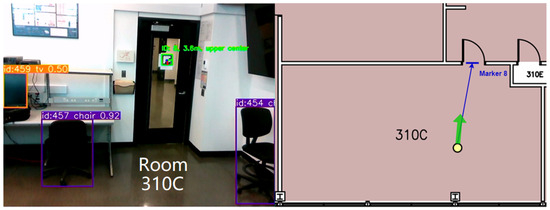

With the rapid advancements in the field of computer and machine vision, the landscape of technologies to assist the visually impaired is undergoing a transformation. The advent of text-to-speech (TTS) and speech-to-text (STT) technologies can greatly improve the interfacing options for the visually impaired [12]. Coupled with the emergence of deep learning algorithms, tasks such as object recognition, which were once challenging, are now attainable and can be integrated into practical applications. Moreover, the progress in embedded systems and system-on-chip (SoC) technologies heralds the advent of portable and wearable smart devices tailored to the needs of the visually impaired [13]. However, many existing systems, including AI-based ones, only specialize in a single aspect of assistance, with the majority of the systems reviewed aiming to solve only one of three tasks: object recognition, obstacle avoidance, and navigation [14,15]. As a result, a holistic system that can seamlessly integrate various functionalities—from navigation assistance to object and text recognition—can be greatly beneficial for visually impaired users. Our proposed VISA system utilizes cutting-edge AI technologies, including advanced object detection and spatial navigation algorithms, alongside user-friendly interfaces to assist visually impaired users in overcoming the challenges associated with indoor activities. By focusing on this area, the proposed VISA system aims to provide a comprehensive solution that can be adapted and expanded to meet a wide range of needs and activities, ultimately facilitating a more accessible and navigable environment for visually impaired individuals. The integration of the tasks is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Layered approach to holistic assistance for visually impaired individuals.

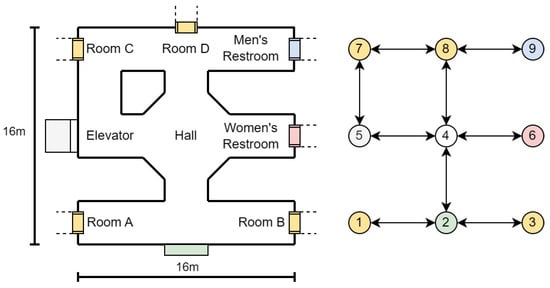

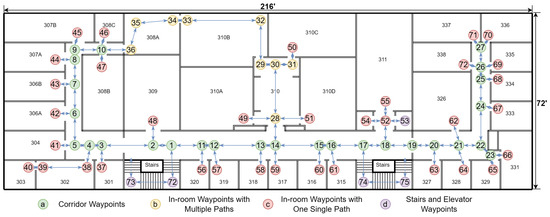

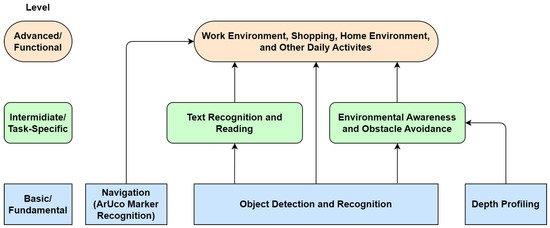

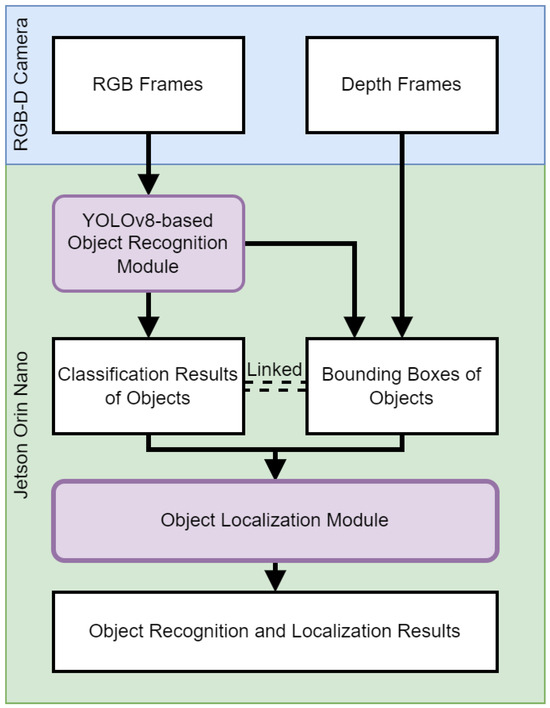

A system diagram of our Visual Impairment Spatial Awareness (VISA) system is shown in Figure 2. We selected the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano as the core of the VISA system due to its optimal balance of power efficiency, compact size, and good computing performance. We chose an Intel RealSense D435 RGB-D camera since its specifications suit indoor navigational use and it has a compact size. While the Internet connection is shown on the diagram, all essential functionalities are completed locally. More detailed discussions regarding hardware selection and configuration are given in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5.

Figure 2.

VISA system diagram.

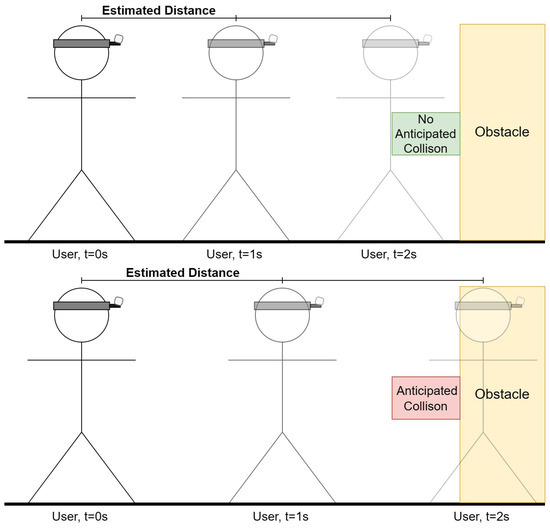

3. Object Recognition and Localization

This section discusses the object recognition and localization module in our VISA system, pivotal in assisting visually impaired users by enabling them to identify and pinpoint the location of everyday objects in their vicinity. At the heart of this exploration is the deployment of a sophisticated RGB-D camera system, paired with the cutting-edge capabilities of YOLOv8—a state-of-the-art neural network model renowned for its accuracy and speed in object recognition tasks. This section aims to dissect the technical underpinnings of the object recognition and localization module, providing a comprehensive overview of the module’s architecture, and the integration of depth sensing to augment spatial awareness. A flowchart of the object recognition and localization processes is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of object recognition and localization.

3.1. Vision-Based Real-Time Object Recognition

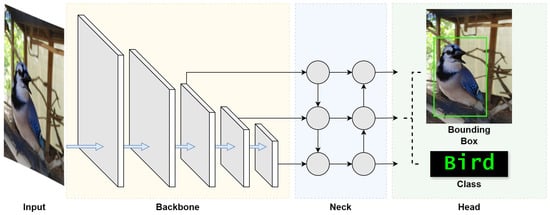

The object recognition module is the linchpin of our VISA system, endowed with the advanced capabilities of the YOLOv8 algorithm. This incarnation of the YOLO series [58] is a state-of-the-art object detection model that has been trained on the COCO (common objects in context) dataset, which encompasses an array of 80 object classes ranging from everyday household items to complex environmental elements [59]. The model structure of YOLOv8 is shown in Figure 4. This is drawn on the basis of [60].

Figure 4.

YOLOv8 model structure [60].

To optimize real-time object recognition for visually impaired users, ensuring swift and precise assistance in diverse environments, it is important to understand YOLOv8’s architecture. To begin, we look into the three fundamental blocks of the architecture, namely the backbone, neck, and head, which together facilitate the entire object recognition process.

The backbone block works as the feature extractor of the YOLOv8 model, and is the first to perform operations on the input image. This block is tasked with identifying and extracting meaningful features from the input image. Starting with the detection of simple patterns in its first few layers, the backbone progressively captures features at various levels, enabling the model to construct a layered representation of the input with sufficient extracted features. Such detailed feature extraction is crucial for the understanding required in object detection.

The neck block follows the backbone block, which acts as an intermediary between the feature-rich output of the backbone block and the head block that generates the final outputs. The neck block enhances the detection capabilities of the model by combining features and taking contextual information into account. It takes feature extractions from different layers of the backbone block, effectively creating layered feature storage. This process allows the model to detect objects large and small. This section of the network also works to streamline the extracted features for efficient processing, striking a balance between speed and the accuracy of the model’s output.

The final block, the head, is where the results of the object detection process are generated. Utilizing the layered features prepared by the neck block, the head block is responsible for categorizing, producing bounding boxes, and assigning confidence levels for each detected object. This part of the network encapsulates the model’s ability to not only locate but also identify objects within an image, making it a vital block in the YOLO architecture. Through the coordinated functioning of these three blocks, YOLO achieves its objective of fast and accurate object detection.

In addition, the convolutional nature of YOLOv8 should be examined. The YOLO architecture performs feature analysis on a local level, focusing on specific regions of an image rather than analyzing it in its entirety. The method relies heavily on the repeated application of convolutions throughout the algorithm to generate feature maps, useful in enabling efficient real-time operation.

YOLOv8 provides a total of five models with different numbers of model parameters: YOLOv8n (Nano), YOLOv8s (Small), YOLOv8m (Medium), YOLOv8l (Large), and YOLOv8x (eXtreme). Their corresponding model parameters are shown in Table 3. Based on the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, we chose YOLOv8s as the model to be used in our VISA system. It has the second-fewest parameters at 11.2 million [58]. YOLOv8s represents an option in the YOLO lineage that is suitable for embedded systems and edge computing, providing a model that is optimized for operational efficiency but still sufficiently accurate. This balance is crucial for real-time applications such as our VISA system, which runs on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano—a platform known for its balance of power and performance in edge computing scenarios. According to the research carried out in [58] and our test result in Table 3, we conclude that YOLOv8s’ position is at the sweet spot of the trade-off between inference time and performance. In other words, a simpler network model like YOLOv8n leads to an unacceptable accuracy drop with no applicable increase in FPS (frames per second), while a more complex model like YOLOv8m reduces FPS noticeably with little improvement in accuracy. Such equilibrium ensures that our VISA system can deliver the real-time object recognition necessary for the navigation and interaction of visually impaired users, while not sacrificing recognition accuracy.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of YOLOv8 variants running on Jetson Orin Nano.

The COCO dataset, the training ground for YOLOv8s, is instrumental in the model’s ability to discern a diverse set of objects. This large-scale dataset facilitates the model’s learning and generalization capabilities, making it robust against the varied visual scenes encountered in indoor environments. The training process involves exposing the model to numerous annotated images, allowing it to learn the features and characteristics of different objects, which leads to the reliable performance of our VISA system.

Implementing YOLOv8s within our assistive technology involved leveraging the pre-trained model and adapting it to the system’s requirements. By integrating the model with the RealSense camera, we crafted a real-time feedback loop that processes visual data to inform and guide users. The module, thus, interprets the class information of recognized objects, to be used for the object localization module and other modules in the VISA system.

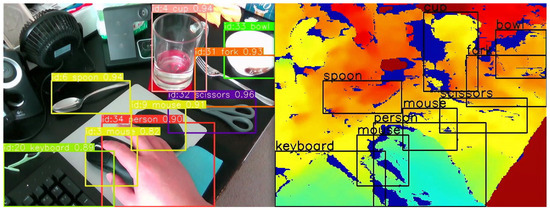

Our empirical tests have demonstrated that YOLOv8s maintains its robust performance in real-world scenarios pertinent to our VISA system. The tests involved running the model through a series of indoor environments, capturing its detection capabilities, and measuring the latency and accuracy of its responses. These tests confirmed the model’s aptness for the intended use-case, ensuring that visually impaired users receive timely and precise information about their surroundings. A comparison of different YOLOv8 models running on the Jetson Orin Nano platform is given in Table 3. The test confirms our statement of the sweet spot for YOLOv8s, as it achieved great average FPS and low power consumption, while not suffering from low accuracy. The object recognition results are shown in Figure 5, which indicates accurate recognition of everyday objects indoors.

Figure 5.

Object recognition results (left) and overlay on the depth image (right).

The YOLOv8s object recognition module is a testament to the advancements in machine learning and its applications in assistive technologies. By leveraging the cutting-edge capabilities of YOLOv8s, our VISA system represents a significant step forward in providing visually impaired individuals with greater autonomy and a more profound interaction with their environment. The module’s ability to process complex visual data in real time opens new avenues for research and development in assistive technology, promising a future where such systems are not just aids but integral parts of how individuals with visual impairments engage with the world around them. Also, the information obtained by the YOLOv8s object recognition system will be utilized by the object localization module, namely recognized object classes and bounding boxes. An example is shown in Figure 5, where we overlay the object classes and bounding boxes onto the depth image. We shall discuss the localization module in the next section.

3.2. Object Localization and 3D Visualization

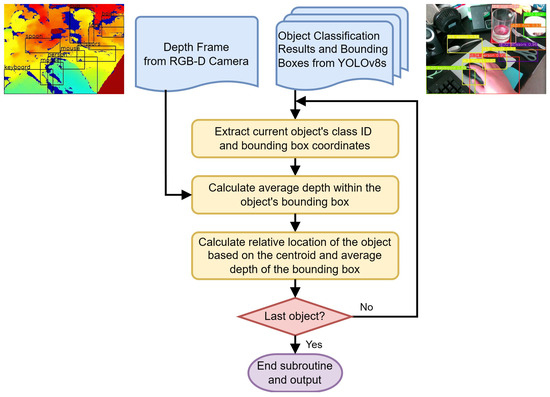

The object localization and 3D visualization module is a pivotal component of our VISA system, designed to translate the object classification results and depth data into locations of the objects in a three-dimensional space. This module uses the bounding boxes and class names provided by the object detection module to generate spatial awareness, enabling visually impaired users to engage with their environment more effectively. A flowchart of the object localization module is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the object localization module.

The object localization module, as depicted in Figure 6, performs a series of steps to identify the location of objects for visually impaired individuals within a 3D environment, on a frame-by-frame basis. The inputs to this module include a depth frame from the RGB-D camera and the corresponding object classification results, which include bounding boxes around detected objects. The classification results act as a backdrop for correlating additional information for other modules, such as the navigation module and the text-to-speech module.

To begin processing, the module extracts the class ID and the bounding box coordinates for each detected object. The class ID indicates the type of object, while the bounding box coordinates define its location in the camera’s field of view.

A key step in this module is the accurate calculation of the average depth within the bounding boxes. The RealSense D435 RGB-D camera utilizes the left image sensor as the reference for the stereo-matching algorithm to generate depth data, resulting in a non-overlapped region in the camera’s depth frames. This non-overlapped region (at the left edge of the frame and objects) contains no depth data (all zeros). Examples of the non-overlapped regions can be seen in the right part of Figure 5, shown as regions in deep blue. The module masks out all such values within the depth frame that fall inside the object’s bounding box. By doing this, we ensure that the average depth represents the true distance to the object.

The average depth within the masked bounding box is then calculated, which provides an estimation of how far the object is from the camera. This step is essential in determining the distance to the object, which is necessary information for a number of different modules, including but not limited to navigation, obstacle avoidance, and the human–machine interface. It can be used to inform the user of the proximity of objects, enhancing their spatial awareness and aiding in safe navigation.

After calculating the average depth, the module computes the object’s relative location based on the centroid of the bounding box and the previously determined average depth. This step ascertains the object’s position in three-dimensional space relative to the camera, providing spatial orientation in the form of the azimuth, the elevation, and the depth of the object. A detailed description of the calculation for azimuth and elevation is given in Section 3.2.1. Finally, a decision step checks if the current object is the last one in the list for this frame. If not, the process loops back to handle the next object. If it is the last object, the subroutine ends.

Upon completion, the module outputs the processed data, which include the distance and relative location of all detected objects within the camera’s field of view. This output can then be used to inform visually impaired users about their immediate surroundings or to guide navigation systems in real time. It also serves as a foundation for translating the results into other sensory modalities, such as audio feedback.

This entire process is optimized for real-time operation, acknowledging the necessity for immediate feedback in an assistive context. The module is fine-tuned to work in concert with the object detection module, ensuring that the visualizations it produces are both current and relevant to the user’s immediate surroundings.

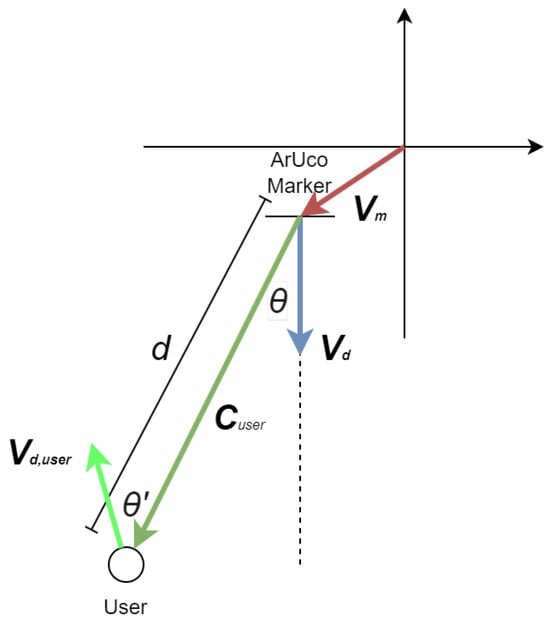

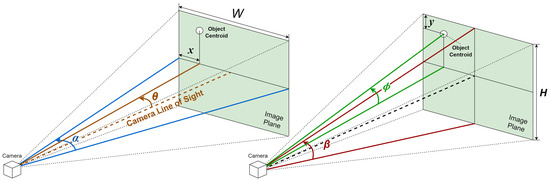

3.2.1. Azimuth and Elevation Calculations

For precise object localization and to obtain data for preventing collisions, it is essential to compute the azimuth and elevation of objects identified within the field of view of an RGB-D camera. This calculation necessitates knowledge of the camera’s field of view and its resolution, specifications that depend on the camera model and can typically be found in its data sheet. The equation to ascertain an object’s azimuth, or its relative horizontal positioning, employs the following parameters: . Here, x is the horizontal position of the geometric center of the region, in terms of the number of pixels from the left edge of the image; is the horizontal field of view of the depth camera in degrees; W is the resolution of the image along the horizontal axis; and is the azimuth of the obstacle in degrees, with 0 indicating dead ahead, a negative value indicating to the left, and a positive value indicating to the right.

Similarly, the following equation can be used to determine the relative vertical position (elevation) of an object: . Here, y is the vertical position of the geometric center of the region, in terms of the number of pixels from the top edge of the image; is the vertical field of view of the depth camera in degrees; H is the resolution of the image along the vertical axis; and is the elevation of the obstacle in degrees, with 0 indicating dead ahead, a negative value indicating below the horizon, and a positive value indicating above the horizon.

A graphical representation of the equations, illustrating the different variables, is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of azimuth and elevation calculation.

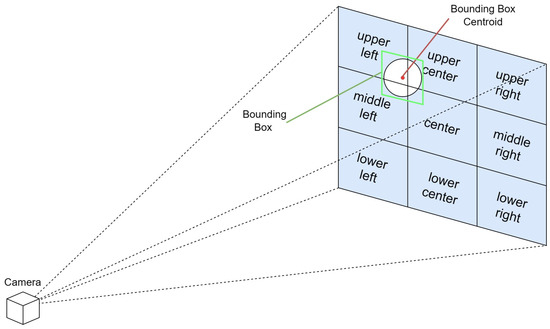

To enable easier understanding and a faster response, we use the rule of thirds to divide the image plane into nine regions, and provide the location of the object in relation to the visually impaired user in terms of the region it resides in. The rule of thirds is a principle in photography and visual arts that divides the image plane into nine equal parts to help compose visual elements in a balanced and aesthetically pleasing manner. This is achieved by overlaying two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines on the image. The intersections of these lines and the areas they define create natural points of interest and divide the space into distinct regions: upper left, upper center, upper right, middle left, center, middle right, lower left, lower center, and lower right.

In the context of assisting visually impaired users through a real-time spatial awareness system, this rule can be adapted to simplify the field of view into these nine manageable regions. By doing so, the VISA system can communicate the location of an object more intuitively. The location within the field of view is determined by the centroid of the bounding box that identifies the object in the camera’s image plane. For example, if the centroid falls within the upper left section of the grid, the VISA system would convey “upper left” to the user. Similarly, if it is in the center, the user would be informed that the object is “center”, and if in the lower right, the information provided would be “lower right”. This method allows for a straightforward and effective way of conveying spatial information, enabling visually impaired users to understand the whereabouts of objects in their immediate environment with greater ease. A graphical representation is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of region separation for intuitive object location.

3.2.2. 3D Visualization

The 3D visualization module embodies the synergy between advanced computer vision techniques and user-centric design. By providing a dynamic, intuitive representation of the environment, the module plays a critical role in empowering visually impaired users to navigate and interact with their surroundings with unprecedented independence. This module not only represents a technical achievement in the field of assistive technology but also marks a significant step towards inclusive design that accommodates the needs and preferences of all users.

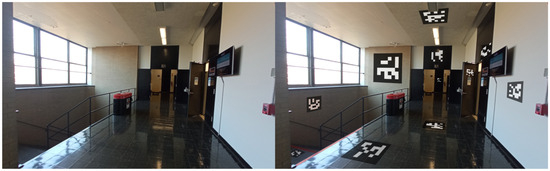

To begin with 3D visualization, it is necessary to understand the location of the RGB-D camera, relative to the visually impaired user wearing it. We chose to wear the RGB-D camera like a headlamp, as shown in Figure 9. An assisting device to be carried by the visually impaired individual an be worn on different parts of the body, and it is important to pick the most suitable spot for the best efficiency and ease of usage. According to the review in [61], for nearly half of the assistant systems for the visually impaired they reviewed, the camera/detector was worn on the forehead or the eyes of the user. As we will show in the discussion below, this is not a coincidence.

Figure 9.

Testing configuration of the RGB-D camera worn like a headlamp.

Mounting an RGB-D camera on the forehead of a user, akin to a headlamp, offers distinct advantages for assisting visually impaired individuals in interacting with their environment. This configuration ensures the camera is positioned at a similar height and orientation to the user’s eyes, providing a field of view that closely mimics that of a sighted person. This natural alignment means the camera can capture a perspective of the world that is intuitively aligned with the user’s direction of interest, enhancing the relevance and accuracy of the information it gathers.

The placement of the camera on the forehead enables users to effortlessly scan a wide arc—up to 270 degrees—in front of them without the need to physically turn their body. This capability is particularly beneficial in crowded or confined spaces where maneuverability is limited. Users can navigate through these environments more efficiently, ensuring a smoother and safer passage.

Additionally, the intuitive ability to look up and down with the camera simplifies the process of bringing objects into the camera’s field of view for recognition. Whether it is identifying products on shelves of different heights in a grocery store or reading signage above eye level, the head-mounted camera adjusts seamlessly to the user’s natural movements, ensuring that relevant objects are easily and quickly identified without requiring manual adjustment of the device.

Turning the head to focus on a desired object or a fiducial marker centers it in the camera’s field of view, significantly simplifying the process of orientation toward a destination or item of interest. This head movement-based control mechanism allows for rapid and precise targeting, which is especially useful for detailed tasks like scanning fiducial markers for navigation within indoor spaces or selecting specific products for closer examination.

By aligning the camera’s perspective with the user’s head movements, the VISA system enhances spatial awareness and facilitates more effective interaction with the environment. This approach not only empowers visually impaired users with greater autonomy and confidence but also streamlines the process of acquiring crucial information about their surroundings, making activities like shopping, navigating complex indoor spaces, and interacting with dynamic environments more accessible and engaging.

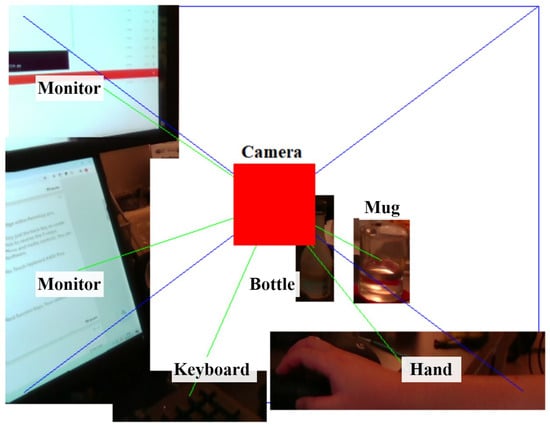

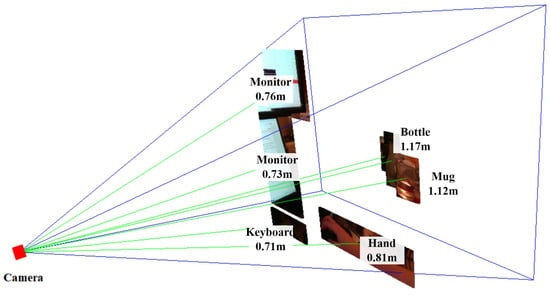

With the information on the setup of our camera, we can come up with a 3D visualization of the objects within the field of view of the RGB-D camera. Starting from the object localization results, the average depths corresponding to the recognized objects are then mapped to the detected bounding boxes. Using the linked depth and bounding box information, a thin 3D box perpendicular to the line of sight of the camera can be created in 3D space, representing the specific physical location of the object.

The final step involves reconstructing the object in 3D using the color information to provide a comprehensive visualization. The pixels within the bounding box in the RGB frame are overlaid on top of the 3D box model. In this visualization, the 3D models of the objects can be interacted with by rotating the view or zooming in for more detail. Such rotation is shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. In Figure 10, we can see the view of the RGB-D camera and the recognized objects on an image plane. However, without annotations of the distances of objects, we cannot understand the depth relationships among the objects. In Figure 11, the entire view is rotated, and we can see the different distances of the objects from the side of the camera. The rectangular pyramid with blue outlines in the two figures indicates the field of view of the RGB-D camera, with the bottom of the pyramid indicating the image plane exactly one meter away from the camera. The green lines connecting the objects and the camera indicate the azimuth, elevation, and distance of each object.

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional visualization of environment, head-on perspective.

Figure 11.

3D visualization of environment, sideways perspective.

In the context of assisting visually impaired individuals, this 3D visualization could be translated into auditory feedback, providing users with an understanding of the environment around them and enhancing their spatial awareness. For instance, the VISA system could describe the size, shape, and relative position of objects, or use audio cues to indicate the direction and distance of items in a store.

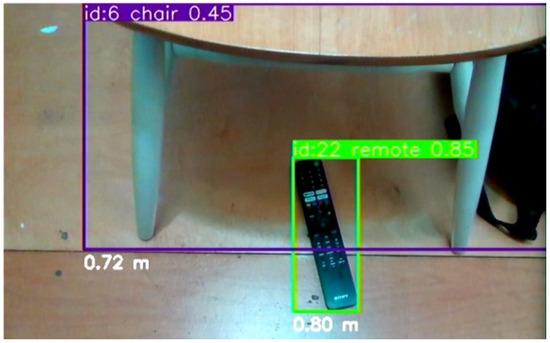

The VISA system was tested in an indoor environment, simulating the task of finding a specific item (a remote) on the floor. Starting with the remote within the field of view but not in the center, blindfolded users could orient their heads toward the remote within two to three seconds upon hearing the information about recognized items. Then, with the distance information provided, it was easy for the users to touch the remote in another two to three seconds. The VISA system ran at no fewer than 10 FPS for the entire duration. The setup is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The testing setup of a TV remote on the floor next to a chair for the user to retrieve.

5. Human–Machine Interface for Visually Impaired Users

In the realm of assistive technologies for the visually impaired, effective HMI is paramount. The need for intuitive, responsive, and accessible communication channels cannot be overstated, as they directly impact the user’s ability to interact with the environment, perform tasks, and engage in different activities. Thus, we provide a detailed description in this section, dissecting the various components that constitute the VISA system’s human–machine interface, focusing on both input and output mechanisms that cater to the specific needs of visually impaired users.

We commence with an in-depth analysis of the text-to-speech module, which serves as the auditory channel for conveying essential information and feedback to the user. Following this, we examine the speech-to-text module, highlighting its role in interpreting user commands and enabling a natural, voice-driven interaction with the VISA system. The discourse then extends to character and object recognition using Google Lens, illustrating how advanced visual recognition technologies can empower users to understand and interact with their surroundings more effectively.

Through the exploration of these key areas, this section aims to underscore the importance of a robust, user-centered human–machine interface in the development of assistive technologies. In the last part of this section, we compare our VISA system with existing items and systems to assist the visually impaired, in terms of practicality and functionality.

5.1. Text-to-Speech Module

The text-to-speech (TTS) module represents a cornerstone of the interactive system designed to empower visually impaired individuals by facilitating the translation of textual information into audible speech. This module plays a pivotal role in enhancing the autonomy and navigational capabilities of the user, by providing real-time, audible feedback about their immediate environment, recognized objects, and navigation cues. The implementation of the TTS module leverages the pyttsx3 library, a cross-platform tool that interfaces with native TTS engines on Windows, macOS, and Linux, offering a high degree of compatibility and customization.

The pyttsx3 library was chosen for its robustness, its ease of integration, and the quality of its speech output. The initialization of the TTS engine is straightforward, facilitating rapid deployment and real-time interaction with the user. The engine is configured to operate in a separate threading model to avoid blocking the main execution thread, thus ensuring that speech output does not interfere with the continuous processing of sensory data and object recognition tasks.

The TTS module is used for multiple tasks of the VISA system, including:

- Announcing detected objects and their locations relative to the user.

- Reading ArUco markers identified in the environment, providing contextual information and navigation assistance.

- Issuing warnings for obstacle avoidance.

- Reading text from the recognition results of Google Lens.

- Interacting with user voice commands or reciting them for confirmation.

To optimize the user experience, the TTS module was customized in several key aspects. The speech rate and volume were adjusted to ensure clarity and audibility, considering the diverse environments in which the VISA system may be used. Furthermore, the selection of voices was tailored to cater to user preferences and accessibility requirements, enhancing the naturalness and engagement of the interaction.

The integration of the TTS module within the broader system architecture is seamless, with APIs facilitating the dynamic generation of speech output based on real-time data from the object recognition and localization modules, as well as user inputs processed through the speech-to-text module. This integration underscores the modular design of the VISA system, where the TTS module functions as an essential interface for human–machine communication.

To summarize, the text-to-speech module serves as a must-have component of the VISA system, embodying the commitment to providing visually impaired users with a comprehensive, intuitive, and accessible navigational aid. Through careful selection of technologies, customization to meet user needs, and seamless integration with the VISA system’s architecture, the TTS module significantly contributes to the overarching goal of enhancing the autonomy and quality of life of visually impaired individuals.

Threading in the Text-to-Speech Module

In the implementation of the text-to-speech (TTS) module within our VISA system, threading is a key technique to enhance the VISA system’s responsiveness and usability, particularly for visually impaired users requiring real-time auditory feedback. The utilization of the threading library in Python facilitates the execution of multiple operations concurrently, thereby ensuring that the VISA system’s main computational processes remain uninterrupted by TTS operations.

The primary motivation behind employing threading for the TTS module stems from the necessity to maintain seamless system performance while executing potentially blocking operations such as speech synthesis. Given the VISA system’s objective to provide instant feedback based on real-time environmental data and user interactions, it is imperative that these feedback mechanisms do not hinder the VISA system’s core functionalities, including object detection, navigation, and user command processing.

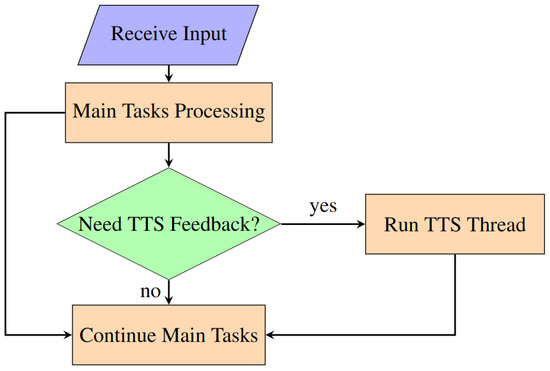

In the system code, threading is utilized to initiate speech synthesis tasks in parallel with the main application processes. This is achieved by encapsulating the TTS functionality within a separate thread, effectively isolating it from the primary execution flow. The specific implementation involves the creation of a speak text thread, which serves as the entry point for the TTS operations. Upon the need for a TTS module, the thread is dedicated to executing the speech synthesis task, thereby allowing the VISA system to continue its operation without waiting for the speech output to complete. The use of the speech thread-running flag ensures that only one instance of speech synthesis is active at any given time, preventing overlapping speech outputs and managing the queue of speech requests effectively. A flowchart for threading in our VISA system is shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Flowchart for threading in VISA system program.

The adoption of threading in the TTS module introduces several benefits:

Non-blocking Operations: By offloading speech synthesis to a separate thread, the VISA system can continue to process sensory inputs, detect objects, and respond to user commands without delay, ensuring a fluid user experience.

Improved Responsiveness: The VISA system can provide immediate auditory feedback to user actions or environmental changes, a crucial aspect for navigation and interaction in real-time scenarios.

Enhanced System Stability: Isolating the TTS operations in a separate thread reduces the risk of system slowdowns or crashes that could result from the synchronous execution of resource-intensive tasks.

The strategic use of threading in the TTS module significantly contributes to the overall performance and user experience of the VISA system. By enabling the concurrent execution of speech synthesis alongside critical system processes, threading ensures that the VISA system remains responsive and effective in providing real-time assistance to visually impaired users.

5.2. Speech-to-Text Module

The speech-to-text (STT) module constitutes an essential component of the human–machine interface within our VISA system designed for visually impaired individuals. This module facilitates an intuitive and efficient means for users to interact with the VISA system through voice commands, significantly enhancing the VISA system’s accessibility and usability. Leveraging advanced speech recognition technologies, the STT module converts spoken language into text, enabling the VISA system to understand and act upon user commands in real time.

The STT functionality is implemented using the speech recognition library, known for its versatility and support for multiple speech recognition services, including Google Speech Recognition. This choice aligns with the VISA system’s need for reliable and accurate speech-to-text conversion, ensuring that user commands are interpreted correctly under various conditions.

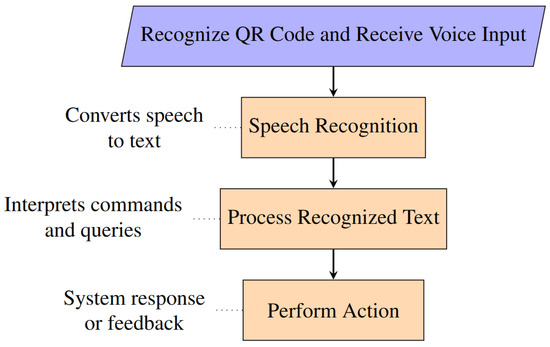

The STT module can be invoked upon recognizing a QR code in the field of view of the camera. The user just needs to place the QR code close to the RGB-D camera to issue commands, with no need for other I/O devices. Upon the start of STT service, the audio is captured and forwarded to the speech recognition service, which processes the audio and returns the corresponding textual representation. This process is encapsulated within the STT function, illustrating the module’s operation, as shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Flowchart for speech-to-text module.

The STT module is seamlessly integrated into the broader system architecture, enabling users to issue voice commands that control various system functionalities, such as navigation commands, requests for information about nearby objects, or commands to repeat the last spoken feedback. The VISA system’s ability to interpret these commands accurately and provide the appropriate feedback or action is paramount to its effectiveness as an assistive tool.

The following commands related to object recognition can be issued by the user:

- List: The VISA system lists all recognized objects in the field of view. Example: “Detected objects are: chair, remote”.

- Look for [Object Class]: The VISA system looks for a specific class of the item in the field of view, and announces its location upon recognition. A [Looking] flag is set, indicating the VISA system is now in item search mode. Reset all other flags. Example: “Remote center, zero point eight meters”.

- Locate: The VISA system looks for ArUco markers in the field of view and announces its corresponding place upon recognition. Example: “Entrance, middle center, zero point six meters”.

- Go to [Node Name]: The VISA system uses Dijkstra’s Algorithm to determine the path to the place announced by the user, and provides instructions based on results from the positioning module. A [Navigating] flag is set, indicating the VISA system is now in navigation mode. The system now automatically announces AruCo markers it recognizes, providing the user with positional information. Reset all other flags. Example: “Turn left ninety degrees for SPAM shelf, one meters”.

- Stop: Reset all flags, exiting from looking mode or navigation mode.

- Upload: Upload the current color frame to Google Lens and read the results.

- Upload Recognized [Object Class]: The VISA system will upload the images within bounding boxes corresponding to the said object class. Read the results.

Implementing an effective STT module within the VISA system presented several challenges, primarily related to achieving high accuracy and responsiveness under varying acoustic environments. Background noise and variations in speech patterns can significantly affect the module’s performance. To mitigate these issues, the VISA system employs noise reduction techniques to enhance recognition accuracy.

Moreover, the reliance on external speech recognition services introduces concerns regarding latency and availability. The VISA system addresses these by optimizing the audio capture and transmission process, and by incorporating fallback mechanisms to ensure continued functionality even when the primary service is unavailable. For example, a timeout is implemented in our VISA system, preventing constant waiting for speech in case of erroneous invoking of the STT module.

To summarize, the speech-to-text module provides a natural and accessible interface for visually impaired users to interact with our VISA system. Through the careful selection of speech recognition technologies, the module contributes to the VISA system’s overall goal of enhancing the autonomy and mobility of visually impaired individuals.

6. Case Study: Grocery Shopping

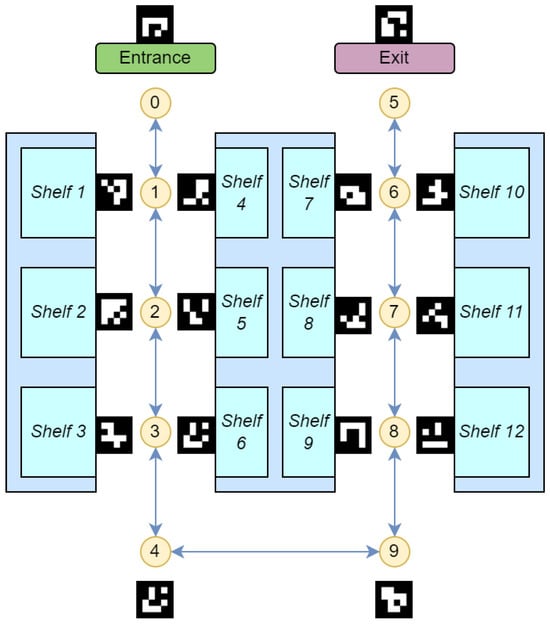

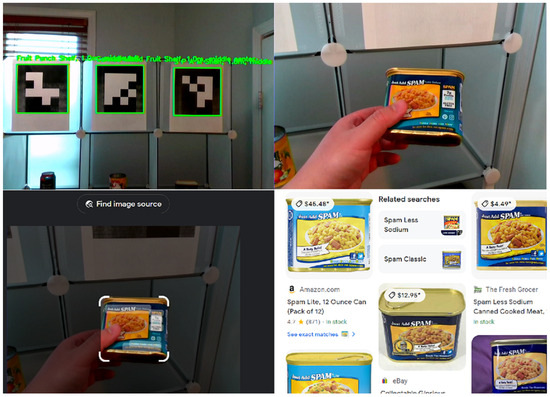

A comprehensive test in a simulated grocery store was conducted with satisfactory results. In the test, the individual can utilize the vocal cues provided by the VISA system, navigate in the simulated environment, pick up the desired items from the correct shelf, confirm selection, and proceed to the checkout/exit. An example layout of part of a grocery store is shown in Figure 21. An example of shelf recognition using ArUco markers, picking up merchandise, and using Google Lens to recognize the merchandise in this store is shown in Figure 22. A list is provided below, looking into the different aspects of using the VISA system to assist in grocery shopping.

Figure 21.

Grocery store simulation environment for navigation and product fetching. The nodes and the shelves are numbered in a sequence.

Figure 22.

Example of shelf recognition using ArUco markers, picking up merchandise, and using Google Lens to recognize the merchandise.

- Challenges in Grocery ShoppingVisually impaired individuals face significant challenges in grocery shopping, such as navigating store layouts, identifying products, and accessing product details. Existing solutions often focus narrowly on either navigation or product identification, requiring costly infrastructure like RFID tags. Few systems address both functionalities comprehensively [64].

- ArUco Markers for NavigationArUco markers provide a cost-effective and flexible solution for store navigation. Placed strategically throughout the store, they enable the creation of a node map that integrates with the VISA system. These markers guide users dynamically, offering positional updates and optimized route calculations.

- Object Recognition and LocalizationThe VISA system leverages YOLOv8 for real-time object recognition, enabling users to identify products and obstacles within their environment. Depth data enhance this capability by providing spatial localization of objects. For detailed product identification, Google Lens delivers specific insights, such as nutritional information and pricing.

- Obstacle Avoidance and Shelf RecognitionThe VISA system employs depth-based algorithms for dynamic obstacle avoidance, ensuring safe navigation in crowded environments. By recognizing shelves and their contents through ArUco markers and YOLOv8, the system facilitates efficient product retrieval. Google Lens enhances the user experience by reading detailed product labels and logos.

- Human–Machine Interface (HMI)The system’s HMI incorporates speech-to-text (STT) and text-to-speech (TTS) technologies. Users can issue voice commands to navigate, identify products, and interact with the system. TTS provides real-time feedback, confirming user actions and delivering navigational guidance. This seamless interaction reduces cognitive load, making the shopping experience intuitive and accessible.

- System Integration and TestingThe VISA system integrates its modules—navigation, object recognition, obstacle avoidance, and HMI—into a cohesive framework. Testing in a simulated grocery store demonstrated the system’s effectiveness. Users successfully navigated aisles, identified products using ArUco markers and Google Lens, and completed shopping tasks independently.

- ConclusionsThe VISA system redefines accessibility for visually impaired individuals in grocery shopping. By addressing navigation, product identification, and human–machine interaction holistically, it promotes independence, inclusivity, and convenience, making daily tasks more achievable.

7. System Comparisons

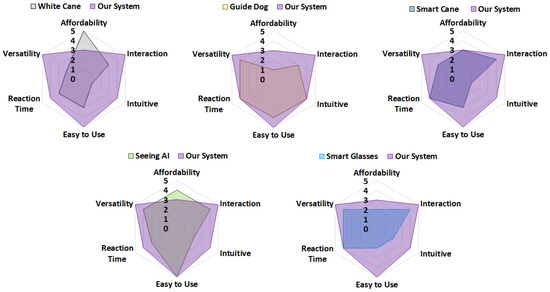

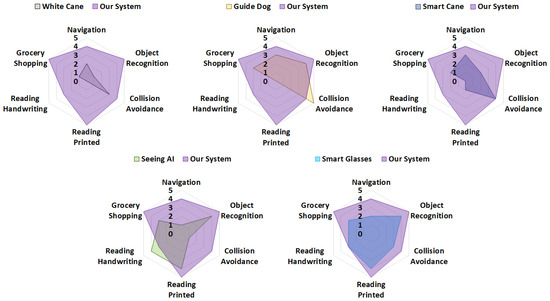

In this section, we perform a conceptual comparison of the practicality and functionality of the VISA system with other techniques. The compared techniques include white canes, guide dogs, typical smart canes with ultrasonic or other forms of collision avoidance [65,66,67], the Seeing AI smartphone app developed by Microsoft [68], and typical smart glasses with object recognition [69,70,71]. The Seeing AI’s app’s counterpart, Lookout—Assisted Vision developed by Google, has similar performance [72,73]. The results are shown in Figure 23 for a practicality comparison and in Figure 24 for a functionality comparison.

Figure 23.

Radar chart comparing the VISA system’s practicality with that of other techniques.

Figure 24.

Radar chart comparing the VISA system’s functionality with that of other techniques.

For the practicality comparison, we scored each system or technique from 0 to 5 based on six attributes, namely affordability, interaction, intuitiveness, ease of use, reaction time, and versatility. Similarly, for the functionality comparison, we scored each system or technique from 0 to 5 based on six attributes, namely navigation, object recognition, collision avoidance, reading printed texts, reading handwriting, and grocery shopping. A higher score indicates better performance in the specific attribute. For instance, white canes receive an affordability score of 5, owing to their simple construction and low cost, whereas guide dogs are assigned an affordability score of 1, reflecting their accessibility to only a small group of individuals due to their high cost.

The proposed VISA system offers a balanced and practical solution for visually impaired individuals, addressing the limitations of conventional techniques across both practicality and functionality metrics. As can be seen in the figures, for practicality, our VISA system sits behind white canes and APPs only in terms of affordability; for functionality, our VISA system is superior to all other techniques, with only guide dogs being equal in terms of collision avoidance, and APPs in terms of reading texts.

In terms of practicality, the VISA system demonstrates a well-rounded balance when compared to conventional solutions such as white canes, guide dogs, smart canes, Seeing AI, and smart glasses. As shown in the radar charts, VISA excels in interaction, ease of use, and versatility, making it more accessible and user-friendly than many other alternatives. Traditional tools like white canes are affordable but lack versatility and intuitiveness, while guide dogs offer strong interaction and intuitiveness but are expensive and require significant training resources. Advanced electronics like smart canes and glasses often provide better interaction and versatility, but neither is intuitive to use. Smart glasses have the added disadvantage of a high price tag. To summarize, the VISA system strikes a strong balance, offering top performance in all five of the other fields while remaining affordable for daily use.

From a functionality perspective, the VISA system competes effectively with conventional solutions, particularly in grocery shopping, navigation, and object recognition. It outperforms all other systems in these areas, and only trails slightly behind AI-powered systems such as Seeing AI in tasks requiring handwriting recognition or complex scene interpretation. Also, for collision avoidance, which is one of the key tasks in assisting the visually impaired and has been extensively researched, our VISA system still outperforms all the other systems except for guide dogs. To summarize, the VISA system effectively bridges the gap in conventional single-task systems by providing robust functionality for common daily tasks like grocery shopping, navigating indoor spaces, and reading printed text.

8. Conclusions

This paper introduces the VISA system, a holistic solution designed to assist visually impaired users with various indoor activities using a multi-level approach. Most existing systems and tools in this domain are single-task-focused and unable to address the diverse tasks faced by visually impaired individuals in complex indoor environments. Consequently, a holistic solution capable of handling multiple tasks can significantly enhance the independence of visually impaired users in such settings. By leveraging recent advancements in computer vision, deep learning, embedded systems, and edge computing, we have successfully developed the VISA system to fulfill the key objectives of a holistic solution.

In summary, the VISA system serves as a comprehensive aid for visually impaired users, providing a suite of functionalities to assist them in their daily activities. By detecting and recognizing common objects within the field of view of the RGB-D camera, the VISA system provides users with a list of nearby objects without requiring physical contact. By conveying direction and distance information of recognized objects, our VISA system enables the user to locate and retrieve items efficiently. By providing navigational cues and auditory warnings, our VISA system helps users reach their indoor destination and avoid obstacles with minimal effort. Moreover, using Google Lens allows users to accurately identify items and read a variety of textual media, such as product labels, handwritten notes, and printed documents. Integrating all the aforementioned functionalities and utilizing their generated information, we deliver holistic assistance that empowers visually impaired users to accomplish a broader scope of tasks with increased efficiency and safety. With experimental results from tests in different environments simulating real-world scenarios, we conclude that our VISA system is easy to use and can assist visually impaired users in nearly all aspects of their daily life, particularly in finding objects, navigating indoor spaces while avoiding obstacles, discerning items of interest, and reading both handwritten and printed text. These findings underscore the potential of our VISA system as an essential aid for the visually impaired. Comparing with existing systems and solutions, our VISA system stands out in terms of all-round effectiveness, versatility, ease of interaction, and vision-related tasks such as object recognition and reading texts.

Throughout this paper, we have demonstrated the effectiveness of the VISA system in indoor environments for everyday activities. However, this system can be expanded and integrated with further advancements in AI. One potential expansion for the VISA system is to provide contextual information about the surrounding environment. While this task is challenging for object recognition algorithms, ongoing advancements in AI technology will enable the VISA system to deliver increasingly refined and intuitive assistance to visually impaired users. For instance, the integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) for picture-to-text translation could allow users to access richer and more detailed information. Additionally, improvements in algorithms and software are possible for the VISA system. Notable examples include a more optimized source code adapted to the Jetson Orin Nano architecture, and an improved depth estimation algorithm based on histogram clustering. Lastly, while the current VISA system may be limited in assisting with outdoor activities, integrating a GPS- and roadmap-based outdoor navigation subsystem could further expand the range of tasks that the VISA system can handle.

Author Contributions

J.S. and X.Y. conceived the concept for this paper. X.Y. served as the primary researcher, responsible for implementing its goals and objectives, while J.S. oversaw and guided the overall direction of this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VISA | Visually impaired spatial awareness |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| HMI | Human–machine interface |

| TTS | Text-to-speech |

| STT | Speech-to-text |

| SoC | System-on-chip |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

| LoS | Line of sight |

| nLoS | Non-line of sight |

| RFID | Radio frequency identification |

| NFC | Near-field communication |

| UWB | Ultra-wideband |

| BLE | Bluetooth low energy |

| RGB-D | Red–green–blue-depth |

| QR | Quick response |

| ArUco | Augmented Reality University of Cordoba |

| COCO | Common objects in context |

| FPS | Frames per second |

| LLM | Large language model |

References

- Bourne, R.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Flaxman, S.; Briant, P.S.; Taylor, H.R.; Resnikoff, S.; Casson, R.J.; Abdoli, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Afshin, A.; et al. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e130–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, R.; Vajaranant, T.S.; Burkemper, B.; Wu, S.; Torres, M.; Hsu, C.; Choudhury, F.; McKean-Cowdin, R. Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, N.A.; Legge, G.E. Blind navigation and the role of technology. In The Engineering Handbook of Smart Technology for Aging, Disability, and Independence; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, J.L. Vision should not be overlooked as an important sensory modality for finding host plants. Environ. Entomol. 2011, 40, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M.; Klatzky, R.L.; Giudice, N.A. Sensory substitution of vision: Importance of perceptual and cognitive processing. In Assistive Technology for Blindness and Low Vision; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, A.D.P.; Medola, F.O.; Cinelli, M.J.; Garcia Ramirez, A.R.; Sandnes, F.E. Are electronic white canes better than traditional canes? A comparative study with blind and blindfolded participants. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. The benefits of guide dog ownership. Vis. Impair. Res. 2005, 7, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refson, K.; Jackson, A.; Dusoir, A.; Archer, D. The health and social status of guide dog owners and other visually impaired adults in Scotland. Vis. Impair. Res. 1999, 1, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refson, K.; Jackson, A.; Dusoir, A.; Archer, D. Ophthalmic and visual profile of guide dog owners in Scotland. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 83, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P. Precious Eyes. The New York Times. 7 November 2013. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/08/giving/precious-eyes.html (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Nahar, L.; Jaafar, A.; Ahamed, E.; Kaish, A. Design of a Braille learning application for visually impaired students in Bangladesh. Assist. Technol. 2015, 27, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.H.; Arovi, M.A.H.; Mahmud, H.; Hasan, M.K.; Rubaiyeat, H.A. Speech based text correction tool for the visually impaired. In Proceedings of the 2015 18th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 21–23 December 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Patra, R.; Mahadevappa, M.; Mukhopadhyay, J.; Majumdar, A. An embedded system for aiding navigation of visually impaired persons. Curr. Sci. 2013, 104, 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Sheikh Sadi, M.; Zamli, K.Z.; Ahmed, M.M. Developing Walking Assistants for Visually Impaired People: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 2814–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, R.; Yang, K.; Zhang, J.; Peng, K.; Stiefelhagen, R. HIDA: Towards Holistic Indoor Understanding for the Visually Impaired via Semantic Instance Segmentation with a Wearable Solid-State LiDAR Sensor. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plikynas, D.; Žvironas, A.; Gudauskis, M.; Budrionis, A.; Daniušis, P.; Sliesoraitytė, I. Research advances of indoor navigation for blind people: A brief review of technological instrumentation. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2020, 23, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalan, R.N.; Namuduri, K. Techniques for Constructing Indoor Navigation Systems for the Visually Impaired: A Review. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2020, 50, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Nazir, S.; Khan, H.U. Analysis of Navigation Assistants for Blind and Visually Impaired People: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 26712–26734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, M.D.; Menelas, B.A.J.; Mcheick, H. Review of Navigation Assistive Tools and Technologies for the Visually Impaired. Sensors 2022, 22, 7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Watabe, M.; Nojiri, T.; Nagaya, T.; Uchiyama, Y. Optically Readable Two-Dimensional Code and Method and Apparatus Using the Same. U.S. Patent 5,726,435, 10 March 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Jurado, S.; Muñoz-Salinas, R.; Madrid-Cuevas, F.J.; Marín-Jiménez, M.J. Automatic generation and detection of highly reliable fiducial markers under occlusion. Pattern Recognit. 2014, 47, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.; van Schyndel, R.; Khalil, I. Accurate positioning using long range active RFID technology to assist visually impaired people. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2014, 41, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, G.A.M.; Boncolmo, M.L.M.; Delos Santos, M.J.C.; Ortiz, S.M.G.; Santos, F.O.; Venezuela, D.L.; Velasco, J. Voice Controlled Navigational Aid with RFID-based Indoor Positioning System for the Visually Impaired. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 10th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), Baguio City, Philippines, 29 November–2 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZuhair, M.S.; Najjar, A.B.; Kanjo, E. NFC based applications for visually impaired people—A review. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Chengdu, China, 14–18 July 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sala, A.S.; Losilla, F.; Sánchez-Aarnoutse, J.C.; García-Haro, J. Design, implementation and evaluation of an indoor navigation system for visually impaired people. Sensors 2015, 15, 32168–32187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, S.A.; Namboodiri, V.; Walker, L. GuideBeacon: Beacon-based indoor wayfinding for the blind, visually impaired, and disoriented. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications (PerCom), Kona, HI, USA, 13–17 March 2017; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.I.; Raj, M.M.H.; Nath, S.; Rahman, M.F.; Hossen, S.; Imam, M.H. An Indoor Navigation System for Visually Impaired People Using a Path Finding Algorithm and a Wearable Cap. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Pune, India, 6–8 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautz, R. Indoor Positioning Technologies; Sudwestdeutscher Verlag Fur Hochschulschriften AG: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davanthapuram, S.; Yu, X.; Saniie, J. Visually Impaired Indoor Navigation using YOLO Based Object Recognition, Monocular Depth Estimation and Binaural Sounds. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT), Mt. Pleasant, MI, USA, 14–15 May 2021; pp. 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Ishfaq, M. An efficient indoor navigation technique to find optimal route for blinds using QR codes. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 10th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Auckland, New Zealand, 15–17 June 2015; pp. 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhalfi, M.L.; Melgani, F.; Zeggada, A.; De Natale, F.G.; Salem, M.A.M.; Khamis, A. Recovering the sight to blind people in indoor environments with smart technologies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 46, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Fujikura, D.; Ozawa, Y.; Tadakuma, K.; Ohno, K.; Tadokoro, S. HueCode: A Meta-marker Exposing Relative Pose and Additional Information in Different Colored Layers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 5928–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Saniie, J. Indoor navigation for visually impaired using AR markers. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT), Lincoln, NE, USA, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlises, C.; Yumang, A.; Marcelo, M.; Adriano, A.; Reyes, J. Indoor navigation system based on computer vision using CAMShift and D* algorithm for visually impaired. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), Penang, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2016; pp. 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, J.; Farrajota, M.; Rodrigues, J.M.; du Buf, J.H. The SmartVision Local Navigation Aid for Blind and Visually Impaired Persons. Int. J. Digit. Content Technol. Its Appl. 2011, 5, 362–375. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, B.K.; Schunck, B.G. Determining optical flow. Artif. Intell. 1981, 17, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, S.S.; Barron, J.L. The computation of optical flow. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 1995, 27, 433–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, K.U.; Khara, D.C.; Gari, T.J.; Chavan, V. Companion: Easy Navigation App for Visually Impaired Persons. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT), Hubli, India, 25–27 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul; Nair, B.B. Camera-Based Object Detection, Identification and Distance Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Micro-Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering (ICMETE), Ghaziabad, India, 20–21 September 2018; pp. 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meers, S.; Ward, K. A vision system for providing 3D perception of the environment via transcutaneous electro-neural stimulation. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Information Visualisation, 2004. IV 2004, London, UK, 14–16 July 2004; pp. 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmannai, W.M.; Elleithy, K.M. A Highly Accurate and Reliable Data Fusion Framework for Guiding the Visually Impaired. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 33029–33054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takefuji, H.; Shima, R.; Sarakon, P.; Kawano, H. A proposal of walking support system for visually impaired people using stereo camera. ICIC Exp. Lett. B Appl. 2020, 11, 691–696. [Google Scholar]

- Owayjan, M.; Hayek, A.; Nassrallah, H.; Eldor, M. Smart Assistive Navigation System for Blind and Visually Impaired Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advances in Biomedical Engineering (ICABME), Beirut, Lebanon, 16–18 September 2015; pp. 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ali, M.A. Blind navigation system for visually impaired using windowing-based mean on Microsoft Kinect camera. In Proceedings of the 2017 Fourth International Conference on Advances in Biomedical Engineering (ICABME), Beirut, Lebanon, 19–21 October 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zereen, A.N.; Corraya, S. Detecting real time object along with the moving direction for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the 2016 2nd International Conference on Electrical, Computer & Telecommunication Engineering (ICECTE), Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 8–10 December 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelamarthi, K.; Laubhan, K. Navigation assistive system for the blind using a portable depth sensor. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology (EIT), Dekalb, IL, USA, 21–23 May 2015; pp. 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yang, G.; Jones, S.; Saniie, J. AR marker aided obstacle localization system for assisting visually impaired. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology (EIT), Rochester, MI, USA, 3–5 May 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 0271–0276. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Muñoz, J.P.; Rong, X.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, J.; Tian, Y.; Arditi, A.; Yousuf, M. Vision-Based Mobile Indoor Assistive Navigation Aid for Blind People. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2019, 18, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, K.; Yi, W.; Lian, S. Deep Learning Based Wearable Assistive System for Visually Impaired People. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 2549–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barontini, F.; Catalano, M.G.; Pallottino, L.; Leporini, B.; Bianchi, M. Integrating Wearable Haptics and Obstacle Avoidance for the Visually Impaired in Indoor Navigation: A User-Centered Approach. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2021, 14, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, L.; Ye, C. An RGB-D Camera Based Visual Positioning System for Assistive Navigation by a Robotic Navigation Aid. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchid, S.; Mennesson, J.; Djéraba, C. Review on Indoor RGB-D Semantic Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Content-Based Multimedia Indexing (CBMI), Lille, France, 28–30 June 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Kretzschmar, H.; Dotiwalla, X.; Chouard, A.; Patnaik, V.; Tsui, P.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chai, Y.; Caine, B.; et al. Scalability in Perception for Autonomous Driving: Waymo Open Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Sun, B.; Wu, G.; Zhao, S.; Ma, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J. Lidar-based sensor fusion slam and localization for autonomous driving vehicles in complex scenarios. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Patel, W. Review on lidar-based navigation systems for the visually impaired. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Seals, C. Design of Mobile Augmented Reality Assistant application via Deep Learning and LIDAR for Visually Impaired. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 January 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofflich, B.; Lee, I.; Lunardhi, A.; Sunku, N.; Tsujimoto, J.; Cauwenberghs, G.; Paul, A. Audio Mapping Using LiDAR to Assist the Visually Impaired. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Taipei, Taiwan, 13–15 October 2022; pp. 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8. 2023. Available online: https://ultralytics.com (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Contributors, M. MMYOLO: OpenMMLab YOLO Series Toolbox and Benchmark. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/open-mmlab/mmyolo (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Xu, P.; Kennedy, G.A.; Zhao, F.Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Van Schyndel, R. Wearable Obstacle Avoidance Electronic Travel Aids for Blind and Visually Impaired Individuals: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 66587–66613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. QR Code Minimum Size: Calculate Ideal Size for Your Use Case. 2020. Available online: https://scanova.io/blog/qr-code-minimum-size/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, M.; Sik-Lanyi, C.; Kelemen, A. Making shopping easy for people with visual impairment using mobile assistive technologies. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, A.A.; Fakhr, M.A.; Seddik, A.F. Assistive infrared sensor based smart stick for blind people. In Proceedings of the 2015 Science and Information Conference (SAI), London, UK, 28–30 July 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1149–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, M.; Mattoccia, S. A wearable mobility aid for the visually impaired based on embedded 3D vision and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication (ISCC), Messina, Italy, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Andò, B.; Baglio, S.; Marletta, V.; Valastro, A. A haptic solution to assist visually impaired in mobility tasks. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2015, 45, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Seeing AI|Talking Camera App for Those with a Visual Impairment. 2019. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/seeing-ai (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Bai, J.; Lian, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Liu, D. Smart guiding glasses for visually impaired people in indoor environment. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2017, 63, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.J.; Chen, L.B.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, J.H.; Yang, T.C.; Lin, C.P. MedGlasses: A wearable smart-glasses-based drug pill recognition system using deep learning for visually impaired chronic patients. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 17013–17024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.J.; Chen, L.B.; Chen, M.C.; Su, J.P.; Sie, C.Y.; Yang, C.H. Design and implementation of an intelligent assistive system for visually impaired people for aerial obstacle avoidance and fall detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 10199–10210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. Lookout—Assisted Vision—Apps on Google Play. 2024. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details-id=com.google.android.apps.accessibility.reveal (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Clary, P. Lookout: An App to Help Blind and Visually Impaired People Learn About Their Surroundings. 2018. Available online: https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/accessibility/lookout-app-help-blind-and-visually-impaired-people-learn-about-their-surroundings/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).