Abstract

GaMo4Se8, is a lacunar spinel where skyrmions have been recently reported. This compound belongs to the Ga family, where M is a transition metal (V or Mo) and X is a chalcogenide (S or Se). In this work, we have obtained pure GaMo4Se8 in polycrystalline form through an innovative two-step synthetic route. Phase purity and chemical composition were confirmed through the Rietveld refinement of the powder XRD pattern, the sample characterisation having been complemented

with SEM analysis. The magnetic phase diagram was investigated using DC (VSM) and AC

magnetometry, which disclosed the presence of cycloidal, skyrmionic and ferromagnetic phases in

polycrystalline GaMo4Se8.

1. Introduction

The lacunar spinels belonging to the Ga family (M = V, Mo; X = S, Se), crystallise, at room temperature, in the cubic F3m (216) space group. At low temperatures, a polar Jahn–Teller (JT) distortion occurs, which consists of a geometrical distortion of atomic positions departing from cubic into rhombohedral symmetry [1]. This distortion, seeking

a lower energy state, takes place via vibronic coupling between the ground and excited

states, if the coupling is sufficiently strong [2]. In this case, by the action of the crystal field,

it is favourable to split the triply degenerate t2 orbitals into two sets of orbitals, a1 and

e [3,4,5]. Such splitting results from the distortion of the structure along the cubic ⟨111⟩

axis, transforming the structure from F3m to rhombohedral R3m. According to the

idealised ionic formula, only seven electrons are available for metal–metal bonding in V

lacunar spinels, but eleven are available in Mo lacunar spinels. Therefore, the three-fold

degenerated highest orbital contains one electron in the V lacunar spinels and five in the

Mo lacunar spinels [6].

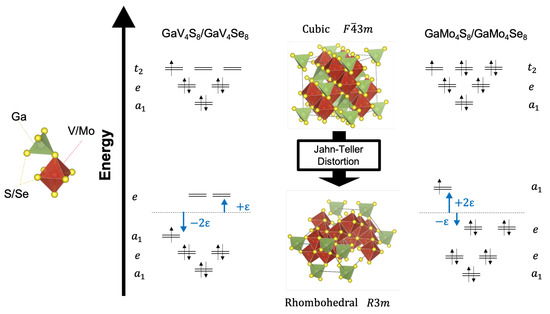

Figure 1 shows the valence molecular orbital diagrams of both and metal clusters, as well as the structure distortion from the cubic to the rhombohedral space group. In the crystal structure, the V/Mo and S/Se atoms form a heterocubane arrangement (in red in Figure 1), while Ga-S/Se bonds group these atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement (in green in Figure 1) [6,7,8]. The rhombohedral angle in the distorted phase is smaller than in the V lacunar spinels and larger than in the Mo lacunar spinels, which inverts the order of the and e orbitals resulting from the orbital splitting by the crystal field [6]. This means that when the orbital energy decreases by , the two e orbitals increase energy by , and vice-versa. By occupying the molecular orbitals with seven electrons in V lacunar spinels, a stabilisation of occurs for , and for . The reverse effect is observed for Mo lacunar spinels, with 11 electrons, for which the stabilisation energy is for and for [6,9,10].

Figure 1.

Effect of the Jahn–Teller transition on the molecular orbital diagrams of the and clusters of atoms.

In the high-temperature phase, the space group of these lacunar spinels, , is non-centrosymmetric and non-polar. The and clusters have a () point symmetry that yields a zero DM interaction in the lowest order [11,12,13]. The JT distortion lowers the () point symmetry to that of the polar point group, allowing the emergence of skyrmions, as in the distorted, polar phase the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction is non-vanishing at the lowest order of the moments, i.e., the bilinear, two-spin coupling. The low-temperature polar structure can host both ferroelectricity and chiral magnetic structures, including skyrmionic magnetic phases [4]. Skyrmions are mesoscopic swirling spin textures, mostly found in chiral magnets. They are usually stabilised by competition between isotropic Heisenberg ferromagnetic exchange and DM interactions in non-centrosymmetric structures [14,15,16], but other mechanisms have been disclosed that may also stabilise these spin arrangements [17]. Skyrmionic compounds are attracting much interest as they may find application in high-density data storage systems. In fact, skyrmions can be manipulated via small magnetic fields and even voltages and currents and so may be used to encode binary digits that can both be read and written [18,19,20]. Thus, provided that they can be stabilised at room temperature, skyrmions may provide efficient digital magnetic recording, due to their small size, high stability and also ease of manipulation, as well as resistive-based memories [21]. Recently, there has been growing interest in 2D topological superconductivity in skyrmionic systems, which may also find a way into interesting applications [22].

The distorted, low-temperature structure of these spinels can host similar spin configurations to those of chiral magnets [23], and indeed it allows the stabilisation of Neél-type skyrmions below the magnetic ordering temperature in these compounds. As result of the symmetry lowering from the parent cubic structure, the low-temperature rhombohedral phase is microtwinned, with four distinct domains. By applying a magnetic field, these domains become non-equivalent if the magnetic anisotropy axes produce different angles to the applied magnetic field. As a result, a complex magnetic behaviour arises and more than one magnetic phase may be stabilised depending on the direction of the applied magnetic field [24].

GaV4S8 is the most well-known lacunar spinel for which the presence of Néel-type magnetic skyrmions has been confirmed by a variety of experimental techniques [25,26]. GaV4S8 is a Mott insulator [27], depicting semiconductor behaviour due to the strong electron–electron interaction. The Jahn–Teller transition occurs at , and presents a complex magnetic phase diagram below , where cycloidal and ferromagnetic spin-ordered phases are found, and also a small region where skyrmions can be observed [28]. A similar skyrmionic phase was found in GaV4Se8, with an extended region of stability compared to GaV4S8 [24,29].

In Mo lacunar spinels, the existence of skyrmions was first suggested to occur in Ga through theoretical studies, namely Monte-Carlo simulations [5]. The experimental evidence of skyrmions was only revealed very recently in such compounds [5,30,31,32]. is also a Mott insulator, with ferromagnetic and cycloidal spin ordering below [4,32,33]. Our previous work proved the existence of a cluster spin-glass phase close to in pollycristalline [34]. In the case of , it orders at and the Jahn–Teller distortion occurs at at 51 K. Recent synchrotron powder diffraction studies on polycrystalline disclosed that below the rhombohedral phase coexists with a metastable orthorhombic phase [30,31]. Such metastable orthorhombic phases can only be detected through Neutron Scattering Techniques at low temperatures, below , and all the related studies are very recent.

In this work, we conducted a thorough study of the compound, covering a novel synthetic route and structural and magnetic characterisation, to investigate its magnetic properties that provide evidence for the existence of a skyrmionic magnetic phase.

2. Materials and Methods

was synthesised in polycrystalline form by a simple two-step method, similar to that used in our previous work for [34]. In the first step, the precursor was synthesised by reacting stoichiometric amounts of molybdenum (foil, thickness 0.1 mm, 99.9%, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and selenium (pellets, <5 mm, 99.99%, Sigma Aldrich) with a molar proportion of 1:2 in evacuated sealed quartz tubes. The tube was placed into a vertical furnace and the temperature was slowly increased from room temperature up to at and kept at that value for 3 days. After this period, the temperature was slowly decreased at the same rate down to room temperature. The second step consisted of reacting the obtained precursor with pure amounts of Ga (99.999%, Sigma Aldrich). Then, the obtained and pure amounts of Ga were both sealed in evacuated quartz tubes under 0.2 atm of argon in a molar proportion of 4:1. These were placed in the furnace for a heating cycle with temperature increasing and decreasing rates identical to those of the first step, but the temperature was held at for one week.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation

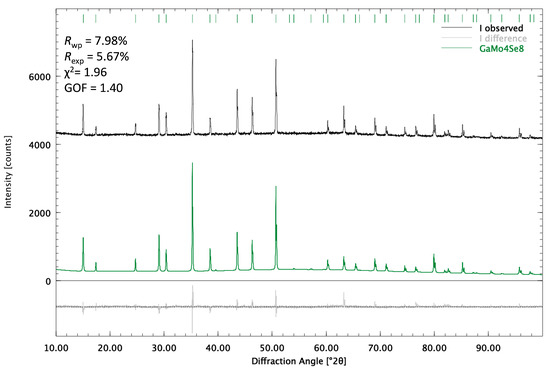

To check the purity of the obtained sample, powder X-ray diffraction data were measured on a Bruker AXS D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with a Cu tube (K = 1.5418 Å) in Bragg–Brentano geometry. The data were obtained from finely ground powder deposited on a low-background, monocrystalline and off-cut Si sample holder. The presence of pure without extraneous phases was confirmed by a search/match procedure against the PDF4+ ICDD database, further corroborated by a Rietveld refinement using the Profex software [35]. During refinement, only cell parameters and those related to the assumed Lorentzian size distribution of grain size were allowed to vary, atomic positions and thermal parameters were fixed at the published values obtained from single-crystal XRD, with the stoichiometry kept at nominal values for . Figure 2 shows the measured and calculated X-ray diffractograms. No residual unindexed peaks remained in the difference pattern, and the refinement converged to the final quality factors , , and . The mean crystallite size refined to the large value of 303(4) nm, close to the upper resolution limit of the diffractometer, showing that the sample was well crystallised. Table 1 shows the crystallographic data from the Rietveld refinement.

Figure 2.

XRD pattern for polycrystalline .

Table 1.

Crystallographic data (from the Rietveld refinement of powder X-ray data) for . Space group , Å. The site occupancy for Ga was fixed to the nominal value during refinement.

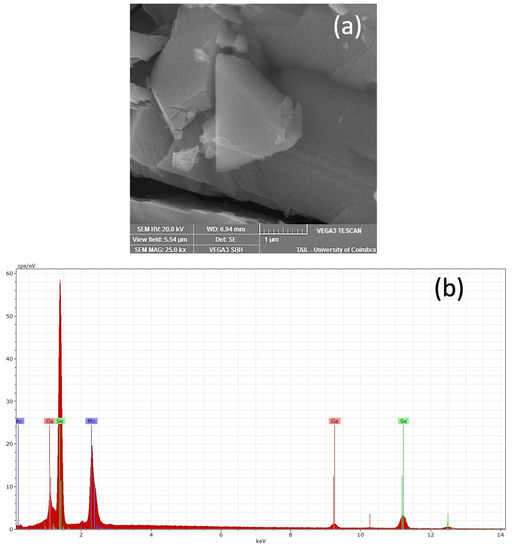

The presented data prove that was obtained with no extraneous phases using the present two-step synthetic method, contrasting with other synthetic routes described in the literature where small amounts of the impurity were always detected [30,31]. A satisfactory Rietveld refinement was obtained ( < 10%), and the residual differences between the observed and calculated intensities occurring in the strongest peaks can be ascribed to texture effects and the large particle size in the obtained powder. The impurity tends to be formed when we react directly stoichiometric amounts of Ga, Mo and Se by the conventional flux method [30,31,36]. Thus, our synthetic route consisting of reacting Ga with the intermediate by avoiding the formation of such impurities affords higher-purity samples of molybdenum lacunar spinels. To investigate in detail the grain size distribution, the morphology of the obtained sample was examined by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and the composition by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The images were obtained with a 5 keV electron beam using a detector of secondary electrons at a working distance of 8 mm (Figure 3a). The obtained EDS spectra and the average composition are depicted in Figure 3b and Table 2, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM image and (b) EDS spectra for polycristalline .

Table 2.

Average composition of determined by EDS.

The examined polycrystalline samples had a grain size in the range 300 nm–1 μm, confirming the large value already found in the Rietveld refinement of the powder XRD data. Only Ga, Mo and Se elements can be detected in the EDS spectra. The average composition, obtained from the EDS analysis, is close to that expected for . No further purification or heat treatment were applied to this sample, which was used as-synthesized for the subsequent magnetisation studies.

3.2. Magnetisation Studies

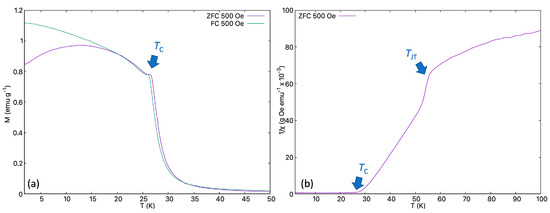

The thermomagnetic measurements were performed on a Quantum Design Dynacool PPMS system equipped with a VSM option. The sample, weighing 3.8 mg, was packed in a clean teflon sample holder. The ZFC (zero-field-cooled) and FC (field-cooled) thermomagnetic curves, measured under an applied magnetic field of 500 Oe, are depicted in Figure 4a, where the anomaly related with can be observed at 27.5 K. A plot of the inverse magnetic susceptibility of the ZFC curve, , as a function of temperature is seen in Figure 4b, showing a clear signature of the Jahn–Teller transition, , occuring at 51 K.

Figure 4.

(a) Magnetisation curves in ZFC (zero-field cooling) and FC (field cooling) for polycrystalline measured with and (b) inverse magnetic susceptibility curves calculated from the ZFC measurement for polycrystalline , measured with an applied magnetic field of 500 Oe. The arrows point to the magnetic ordering temperature, and the Jahn–Teller transition, .

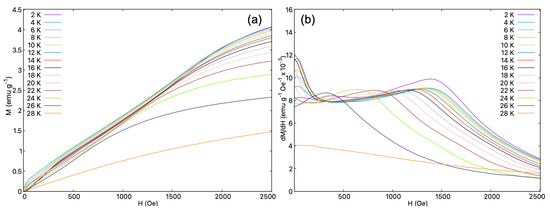

The skyrmionic magnetic phase found in these type of compounds occurs close to , stabilised under the action of an applied magnetic field. It is known that a signature of the skyrmion phase in can be found in M(H) measurements, better depicted as a change in the derivative of the curve when the phase boundary of the region where skyrmions exist is crossed. Thus, and in order to unveil the presence of the skyrmionic phase, accurate M(H) measurements with a small H step of 5 Oe and long VSM integration times were performed, covering the temperature between 2 K and 28 K, where skyrmions are expected to exist in .

The obtained curves are presented in detail in Figure 5a. The derivative of the data, dM(H)/dH, was calculated by a standard centred three-point numerical method followed by a smoothing filter of the type acsplines to reduce numerical noise [37] and it is presented in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

(a) and (b) dM/dH curves obtained for .

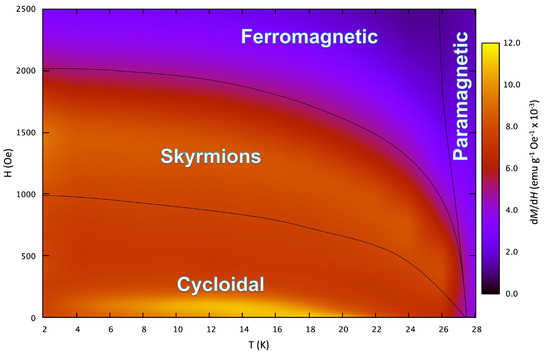

From the extensive set of curves covering the temperature range between 2 and 28 K, it is possible to plot the magnetic phase diagram based on the dM(H)/dH curves. The anomalies representing the transition between cycloidal, skyrmionic and ferromagnetic phases can be detected in such curves. For a better representation of the magnetic phase diagram of , the dM/dH data are represented in a coloured pseudo 3-D plot, shown in Figure 6. This plot was produced using the pm3d interpolation algorithm implemented in gnuplot [37].

Figure 6.

Magnetic phase diagram obtained from the numerative dM/dH curves for .

3.3. AC Susceptibility Measurements

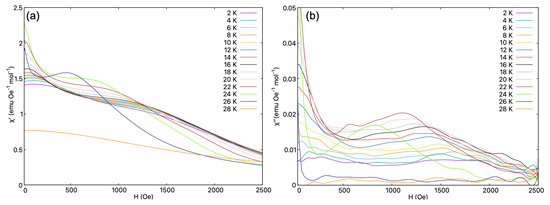

To complement the data obtained from the d/dH curves, AC susceptibility measurements were performed using the ACMS II option of the PPMS system. The data were collected on a small pellet of (obtained by pressing 10 mg of fine powder) that was glued with a thin layer of GE cryogenic varnish onto a low-background quartz sample holder. The measurements were performed with an AC magnetic field of 5 Oe amplitude in the temperature range 2–28 K, as a function of the applied DC magnetic field up to 2500 Oe. The real () and imaginary () AC susceptibility components as a function of magnetic field are shown in Figure 7a,b, respectively.

Figure 7.

(a) and (b) components of the AC magnetic susceptibility as function of the DC magnetic field, up to 2500 Oe, for temperatures between 2 K and 28 K. = 5 Oe, f = 1000 Hz.

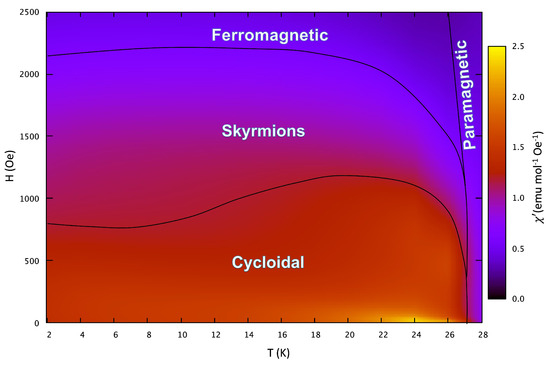

Both the and components of the AC susceptibility curves are similar to the obtained dM/dH curves presented in Figure 5. The anomalies related to the magnetic phase transitions can be observed in such curves. The results of the measured curves are depicted in graphical form in Figure 8, obtained from the component of AC susceptibility, with the different magnetic phases represented, using the pm3d interpolation algorithm implemented in gnuplot [37]. The boundaries were determined from the component, superimposed on the colour map representing the values of .

Figure 8.

Magnetic phase diagram obtained from the component of AC susceptibility measurements for .

Similar to the dM/dH map, presented in Figure 6, the magnetic phases can be depicted in the map of the AC susceptibility component and the phase boundaries determined from the component. From both the VSM and AC susceptibility measurements, the skyrmion phase was found to be present in a large temperature range, from to 2 K up to 27.5 K, where the ferromagnetic/paramagnetic transition occurs. From these data, we can conclude that in the cycloidal and skyrmion regions span more extended temperature regions compared to those observed in other lacunar spinels.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we have accomplished the synthesis of high-purity though a two-step chemical route similar to that used for the synthesis of . From both VSM and AC susceptibility measurements, we have shown that the skyrmionic magnetic phase is stabilised under an applied magnetic field in a large temperature range, from 2 K up to , in a polycrystalline sample. These measurements do not show any anomaly that could be associated with the onset of a metastable orthorhombic phase, which has been suggested by synchrotron radiation studies to co-exist with the main, low-temperature, rhombohedral phase. This point, and the details of the magnetic structures and their evolution with the applied magnetic field, deserve to be further investigated by microscopic techniques such as neutron scattering.

Author Contributions

J.F.M.: synthesis, characterisation, physical property measurements, analysis of the results, investigation and writing. M.S.C.H.: physical property measurements, investigation and writing. J.A.P.: physical property measurements, analysis of the results, investigation, writing and funding. A.P.G.: investigation and writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

José F. Malta’s PhD grant was supported by FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through the ChemMat PhD programme. Access to the TAIL-UC facility supported by the QREN-Mais Centro programme ICT_2009_02_012_1890 is gratefully acknowledged. This work was partially supported by funds from FEDER (Programa Operacional Factores de Competitividade COMPETE) and from FCT under the projects UIDB/FIS/04564/2020, UIDP/FIS/04564/2020 and PTDC/FIS-MAC/32229/2017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reinen, D. The Jahn-Teller Effect in Solid State Chemistry of Transition Metal Compounds. J. Solid State Chem. 1979, 27, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, P.; Yamauchi, K.; Picozzi, S. Jahn-Teller distortions as a novel source of multiferroicity. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 014116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, S.A.; Solovyev, I.V. Skyrmionic order and magnetically induced polarization change in lacunar spinel compounds GaV4S8 and GaMo4S8: A comparative theoretical study. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 014414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Puggioni, D.; Rondinelli, J.M. Assessing exchange-correlation functional performance in the chalcogenide lacunar spinels GaM4Q8 (M = Mo, V, Nb, Q = S, Se). Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 115149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Chen, J.; Barone, P.; Yamauchi, K.; Dong, S.; Picozzi, S. Possible emergence of a skyrmion phase in ferroelectric GaMo4S8. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 214427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocha, R.; Johrendt, D.; Pottgen, R. Electronic and Structural Instabilities in GaV4S8 and GaMo4S8. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 2882–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.V.; McDowall, A.; Szkoda, I.S.; Knight, K.; Kennedy, B.J.; Vogt, T. Cation Substitution in Defect Thiospinels: Structural and Magnetic Properties of GaV4xMoxS8. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 5035–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, D.; Slavik, H.; Johrendt, D. Low Temperature Crystal Structures and Magnetic Properties of the V4 Cluster Compounds. Z. Naturforsch. 2009, 64, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geirhos, K.; Krohns, S.; Nakamura, H.; Waki, T.; Tabata, Y.; Kézsmárki, I.; Lunkenheimer, P. Orbital-order driven ferroelectricity and dipolar relaxation dynamics in multiferroic GaMo4S8. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 224306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Im, J.; Han, M.J.; Jin, H. Spin-orbital entangled molecular jeff states in lacunar spinel compounds. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, I.A.; Qaiumzadeh, A.; Brataas, A.; Titov, M. Chiral ferromagnetism beyond Lifshitz invariants. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 161403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, I.A.; Tchernyshyov, O.; Titov, M. Noncollinear Ground State from a Four-Spin Chiral Exchange in a Tetrahedral Magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 127204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T.; Prodan, L.; Geirhos, K.; Nakamura, H.; Kézsmárki, I.; Hozoi, L. Dressed jeff-1/2 objects in mixed-valence lacunar spinel molybdates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.W.; Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: A magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versteeg, R.B.; Vergara, I.; Schäfer, S.D.; Bischoff, D.; Aqeel, A.; Palstra, T.T.M.; Grüninger, M.; Van Loosdrecht, P.H. Optically probed symmetry breaking in the chiral magnet Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 094409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimuth, F.; Bamler, R.; Mokrousov, Y.; Rosch, A. Phase-space Berry phases in chiral magnets: Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction and the charge of skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 214409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, N.D.; Nakajima, T.; Yu, X.; Gao, S.; Shibata, K.; Hirschberger, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Peng, L.; et al. Nanometric square skyrmion lattice in a centrosymmetric tetragonal magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romming, N.; Hanneken, C.; Menzel, M.; Bickel, J.E.; Wolter, B.; von Bergmann, K.; Kubetzka, A.; Wiesendanger, R. Writing and Deleting Single Magnetic Skyrmions. Science 2013, 341, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagemeister, J.; Romming, N.; von Bergmann, K.; Vedmedenko, E.Y.; Wiesendanger, R. Stability of single skyrmionic bits. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchio, G.; Büttner, F.; Tomasello, R.; Carpentieri, M.; Kläui, M. Magnetic skyrmions: From fundamental to applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2016, 49, 423001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, F.; Lemesh, I.; Beach, G.S.D. Theory of isolated magnetic skyrmions: From fundamentals to room temperature applications. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascot, E.; Bedow, J.; Graham, M.; Rachel, S.; Morr, D.K. Topological superconductivity in skyrmion lattices. npj Quantum Mater. 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Kanazawa, N. Magnetic Skyrmion Materials. Chem. Rev. 2020, 121, 2857–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordács, S.; Butykai, A.; Szigeti, B.G.; White, J.S.; Cubitt, R.; Leonov, A.O.; Widmann, S.; Ehlers, D.; von Nidda, H.A.K.; Tsurkan, V.; et al. Equilibrium Skyrmion Lattice Ground State in a Polar Easy-plane Magnet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, E.; Widmann, S.; Lunkenheimer, P.; Tsurkan, V.; Bordács, S.; Kézsmárki, I.; Loidl, A. Multiferroicity and skyrmions carrying electric polarization in GaV4S8. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e150091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butykai, Á.; Bordács, S.; Kézsmárki, I.; Tsurkan, V.; Loidl, A.; Döring, J.; Neuber, E.; Milde, P.; Kehr, S.C.; Eng, L.M. Characteristics of ferroelectric-ferroelastic domains in Néel-type skyrmion host GaV4S8. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadava, C.; Nigamb, A.K.; Rastogia, A.K. Thermodynamic properties of ferromagnetic Mott-insulator GaV4S8. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2008, 403, 1474–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kézsmárki, I.; Bordács, S.; Milde, P.; Neuber, E.; Eng, L.M.; White, J.S.; Rønnow, H.M.; Dewhurst, C.D.; Mochizuki, M.; Yanai, K.; et al. Néel-type skyrmion lattice with confined orientation in the polar magnetic semiconductor GaV4S8. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, B.; Philipp, S.; Geirhos, K.; Mehlin, A.; Bordács, S.; Tsurkan, V.; Leonov, A.; Kézsmárki, I.; Poggio, M. Stability of Néel-type skyrmion lattice against oblique magnetic fields in GaV4S8 and GaV4Se8. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueller, E.C.; Kitchaev, D.A.; Zuo, J.L.; Bocarsly, J.D.; Cooley, J.A.; der Ven, A.V.; Wilson, S.D.; Seshadri, R. Structural evolution and skyrmionic phase diagram of the lacunar spinel GaMo4Se8. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 064402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, K.; Vir, P.; Cook, N.; Murgatroyd, P.A.E.; Ahmed, S.J.; Savvin, S.N.; Claridge, J.B.; Alaria, J. Mode Crystallography Analysis through the Structural Phase Transition and Magnetic Critical Behavior of the Lacunar Spinel GaMo4Se8. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 5718–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butykai, Á.; Geirhos, K.; Szaller, D.; Kiss, L.; Balogh, L.; Azhar, M.; Garst, M.; DeBeer-Schmitt, L.; Waki, T.; Tabata, Y.; et al. Squeezing the periodicity of Néel-type magnetic modulations by enhanced Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction of 4d electrons. npj Quantum Mater. 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.K.; Berton, A.; Chaussy, J.; Tournier, R. Itinerant Electron Magnetism in the Mo4 Tetrahedral Cluster Compounds GaMo4S8, GaMo4Se8, and GaMo4Se4Te4. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1983, 52, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, J.F.; C. Henriques, M.S.; Paixão, J.A.; P. Gonçalves, A. Evidence of a cluster spin-glass phase in the skyrmion-hosting GaMo4S8 compound. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 12043–12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebelin, N.; Kleeberg, R. Profex: A graphical user interface for the Rietveld refinement program BGMN. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querré, M.; Corraze, B.; Janod, E.; Besland, M.P.; Tranchant, J.; Potel, M.; Cordier, S.; Bouquet, V.; Guilloux-Viry, M.; Cario, L. Electric pulse induced resistive switching in the narrow gap Mott insulator GaMo4S8. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 617, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnuplot 5.2: An Interactive Plotting Program. 2019. Available online: http://gnuplot.sourceforge.net/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).