Abstract

In an effort to protect intellectual property beyond patent and plant breeders’ rights and as a marketing tool to increase and maintain sales, the creation and trademarking of brand names for fruit is growing and gaining importance in the fruit industry. New fruit varietals, especially from long-lived tree fruits and vines, take many years of research to develop and bring to market. Differentiating what is essentially a commodity product is difficult, especially given bulk sales and packaging limitations. A distinctive brand name can be a powerful method of differentiating a new fruit from its competitors. To the best of our knowledge there has not been any study examining the process of brand name creation for fruits. This English language literature review examines the brand name creation process overall. A step-by-step process is discussed and situated in the context of fruits. Research on the overall process is dated: We propose a new preliminary research step to improve the process and discuss the need for future research on the role of the Internet and social media in the naming process. An overview of trademark considerations is provided. Knowledge of this process will assist breeders and marketers with brand name creation whether achieved internally or through an external agency or combination thereof.

1. Introduction

The development and commercialization of new varietals of long-lived fruit perennials, such as tree fruits and vines is an expensive, long, up to 20 years process. The creation of trademarked (TM) brand names for such fruit is growing as a method to promote a new varietal, creating valuable brand equity, and as a method to protect the long-term investment made in breeding and marketing new varietals [1]. In general, varietal developers and managers also consider branding fruit if a new varietal will be marketed for many years, out-living its 20-year plant breeders right (PBR) protection, and if it will be in the marketplace long enough (weeks, months) to enable consumers to recognize it, want it, and actually be able to buy it [2]. Cotton Candy® grapes, Cuties® mandarins, Zespri® kiwis, Sweet Sensation® pears, Staccato® cherries, and Salish® apples are a few examples of fruit brands.

A brand name is a short-form method, a means of coding, by which consumers can identify and differentiate the origin of specific products and services [3]. Beyond these functional properties, a brand name is also a symbolic method of generating images and meanings, including unconscious meanings, and it is “the most common medium through which consumers will relate to a product” [3,4] (p. 25). The brand name decision is the first step of creating a brand, the most important defining element, and is at the foundation of all subsequent marketing efforts [5,6].

Brands make consumer choices easier by decreasing perceived purchase risk, especially for low involvement habitually bought dietary staples, such as fruit, when there is little impetus to seek other information [7,8,9,10]. Brand names are an extrinsic cue used to evaluate a product, unlike inherent product attributes or intrinsic cues which cannot easily be evaluated without trial [11,12,13,14]. In the absence of a brand name fruit varietals could be perceived as undifferentiated commodities, identical and substitutable. Consumers may then use prior experience within a product category to interpret new information and make inferences about a new, untried product [15,16,17,18]. General product knowledge may provide default values, or the assumption of average values, about specific product attributes if information is missing [19], and in the absence of perceived differences, consumers appear to be less brand loyal, more price sensitive, and less open to marketplace information [20].

Even though several varieties of a fruit may taste similar and look similar, branding can be used to infer strong differentiation [5,21]. Consumer preferences are not formed by just product experience alone, consumers have been ‘taught’ to expect differences across brands [20]. Brand names and marketing engender familiarity, influence consumers and their perceptions, and leads to preferences [4,5,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Although fruit varietal names may sometimes act like brand names (apples, for example) [25], we distinguish between them and focus on brand names for two reasons: 1. For many fruits, consumers traditionally do not know and are not informed of varietal names (nectarines, for example); and, 2. A varietal name does not enjoy the same long-term legal protection as a registered TM name and is fundamentally different. A varietal name is the generic name for a particular cultivar of cultivated plant (fruit), regardless of the commercial source, and must enable the variety to be identified: it is its name. Generic names may be used by all, in reference to the plant so-named. In contrast, a TM brand name indicates the commercial source, the grower of a fruit varietal or a company or corporation involved in fruit breeding, production, and commercialization. Certain rights and restrictions of use are attached to TMs: only the TM owner and licensees have exclusive rights to use that TM. A registered TM also acts as a valuable signal to the consumer that the product meets specific quality standards [27].

The literature on the process of creating new brand names has become dated, with the bulk of the research published in the 1980s and 1990s. To the best of our knowledge the last published paper specific to the process of creating new brand names was published in 2007 [28]. The topic has evolved, with the Internet and social media having a large impact on marketing and branding. Due to the Internet, information is instantly global now. The fruit industry has also evolved, moving from being a supply driven, commodity-based market to one focused on consumers and the development of new, unique, fruit varietals to meet consumer preferences and quality expectations [1]. It is an industry increasingly becoming greater in scale, global, and involving restricted grower access and control via ‘Clubs’ or grower cooperatives [1].

Food industries other than fruit and vegetable industries (e.g., processed foods and beverages) are more familiar with the consumers of their products, often simply due to their industry structure, with a shorter supply chain from the manufacturer to the consumer. These industries also benefit from a possibly faster development schedule of a new food product, and years of consumer-focused product development experience in highly competitive markets. In the tree fruit and vine industries, the development process of a new varietal is very long, with many different players involved before any new fruit is available for sale at the retail level. The history of developing brands for fruits is much more recent. Competition is increasing, and the necessity of paying attention to the brand naming process and having it done right are now highly important.

Several researchers have examined in detail the process by which new brand names are created by companies [29,30,31,32,33]. More recently, Kollmann and Suckow [28] examined the process of creating new corporate names for entrepreneurial firms in the net economy. Other studies have been more discussion-oriented, suggesting best practices [5,34,35] or presenting a case study [36]. The procedures for creating a new brand name may differ somewhat between articles, but essentially all articles reported a multi-step process.

Despite the importance of brand names, it appears that taking short-cuts in terms of time, effort, and financial resources for name creation is not unusual and there is a need for a more comprehensive professional approach [33,37]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study of the brand name creation process specifically for fruit and no practical guideline available for fruit commercialization departments to familiarize themselves with the process of creating a brand name. As a result, the objectives of this study are to (i) review the brand name creation process literature; (ii) determine any gaps in the literature and provid suggested updates; and, (iii) integrate the relevant knowledge, and prepare a practical brand name creation instruction aimed at the fruit industry, including a summary of plant variety denominations and TMing.

This research is for the benefit of people and organizations commercializing new fruit varietals, whether they create a brand name in-house, engage external specialists, or both. It will also interest breeders, scientists, multidisciplinary researchers to retail marketers, and others along the supply chain, who can learn of the important role and impact of branding and brand names in today’s market.

2. Research Methods

A traditional descriptive (qualitative), semi-systematic, English language literature review was conducted [38]. Our research questions included how the brand name creation process has developed over time, which steps are considered in different papers, and what gaps in the literature can be identified. Key search terms included: Brand names, brand name development, brand name process, and brand name steps. Databases, searched between December 2019 and October 2022, included: Business Source Corporate Plus, Business Source Ultimate, ABI/Inform, Cambridge Core, JSTOR, Emerald Insight, ProQuest and Scopus, Wiley, Sage, Web of Science (by Clarivate), and Google Scholar.

The focus of this review is on the process—the structure—used to create a new brand name, primarily for consumer products which are of higher relevance to the fruit industry. Pharmaceutical industry papers were excluded from our search as we consider it a specialized branding sector. Prior research that centered on the overall process of creating new brand names qualified for inclusion. With the exception of one early paper that includes some name creation steps, non-process focused papers were excluded. For example, research centered on specific brand name elements, such as their meaningfulness, how well they were recalled, or their linguistic qualities such as sound symbolism, were excluded. Papers relating to an aspect of one step of the process, rather than the full process, were excluded from the review, as each step could be worthy of its own review. This paper is not intended to be a definitive review of the brand naming process inclusive of all business sectors, such as business to business, the service sector, or various industries.

More than 200 papers were scrutinized for inclusion or exclusion. Of those, 150 concentrated on aspects of the brand name within branding or marketing such as brand identity, brand strategy, and brand name effects on consumer perceptions, for example, or the evaluation of brand names or brand name types. In addition, over 41 papers about sound symbolism and brand naming were excluded. All of the papers that did not focus on the brand name creation process were excluded from the review section of this paper. Some were cited in the brand naming steps section of our paper and the rest were eliminated. In the end, a total of ten papers fit our inclusion criteria, the last one published in 2007. We hypothesize that this is likely due to the monetization of the process by professional marketing and branding agencies whose research on, or development of, the process is often proprietary and private. Our search indicates that academic research on the subject has stalled and research appears to have shifted to more detailed research on specific aspects of branding and marketing, such as brand image, visual marketing, brand equity, and the characteristics of, or influence of, the brand name itself, for example, rather than on the overall name creation process.

Gaps in the literature were investigated. One of those gaps, preliminary name research, is further discussed. We then provide an overview of each step, relating them to the fruit industry. Finally, areas for future research are identified and discussed.

3. Review: Brand Name Creation Research

Brand name creation research has focused on two aspects: 1. The actual process used to create a new brand name; and, 2. The recommended or prescriptive process to create a new brand name [33]. The literature emphasizes a step-by-step process for creating a new brand name. Table 1 provides a comparison of different methods and steps reported for brand name creation in the published literature.

Table 1.

Previous research of the brand name development process.

Collins [34] discussed the naming of new brands from a psycholinguist perspective. His focus was not on an overall step-by-step name creation process, but specifically on the linguistic aspects of how to create a good new brand name. Nevertheless, Collins did summarize 4 steps (see Table 1), and is included in our review as an early example of discussion of the brand name creation process. Collins’ paper uses examples mostly from the UK or Europe involving the brand names of consumer products. TMing was not addressed.

McNeal and Zeren [29] were the first to study the actual brand name development processes used by large American consumer product manufacturers. Their survey provided evidence of a six-step process (although there were variations, including the use of packaging design concepts in the evaluation phase) and the first evidence of a TM search step, but was criticized for not distinguishing brand objectives from overall marketing objectives, omitting brand strategy decisions, confusing brand objectives with brand name criteria, and lacking or missing detail due to the use of open-ended questions [30,31]. Only very large companies, highly experienced in creating and selecting brand names, were surveyed, and their results could not be generalized [29].

Opatow [35] situates her paper mostly in the American consumer products and services markets, emphasizing the need for structure and discipline to avoid introducing personal biases and prejudices to the process. Unlike McNeal and Zeren [29], Opatow [35] did include a step to detail required name criteria and emphasized the need for a light initial cull of names, followed by iterative rounds of elimination backed by adhering to the objectives and name criteria. It is unknown how closely companies follow her prescribed process. Lefkowith and Moldenhauer [36] presented a case study detailing the steps followed by a regional American bank to create a brand name for a new consumer account-type. Their eight-step process included a unique initial step of preliminary background research, and the creation of initial design concepts for the evaluation of final candidate names. Results could not be generalized.

Shipley et al. [30,31] furthered McNeal and Zeren’s [29] research via a survey of British consumer goods and food manufacturers. Shipley et al. [30,31] developed a brand name creation model based on extensive qualitative research with consumer goods marketing executives, created and pilot tested a survey, revised it, then ‘validated’ the model via asking survey respondents to rate the importance of each step provided. Detailed, closed-end questions were asked about brand objectives, strategy, and name criteria. The survey did not ask what brand name creation tasks were actually performed, but assumed the information from marketing executives was comprehensive, thus some information may have been missed and the actual process followed was unknown [33]. Unlike McNeal and Zeren [29], a range of company sizes were included in the results.

Shipley and Howard [32] investigated the brand name creation process for industrial companies in Britain, using much the same methodology as in Shipley et al. [30,31]. The same six steps were again confirmed. The criticism by Kohli and LaBahn [33] still applied.

Kohli and LaBahn [33] surveyed American consumers and industrial goods manufacturers about the actual process followed. The authors compared and contrasted the process used by consumer versus industrial respondents. They identified a five-step brand name creation process: objectives, generation of names, evaluation, selection, and TM registration. Kohli and Labahn [33] found that the respondents did not distinguish marketing and brand objectives from brand name criteria, and the name criteria made an appearance only at the name evaluation stage. An average of 46 candidate names were created by respondents. Like Shipley et al. [30,31,32], they found that existing names are sources for generating new names, providing evidence of the ‘banking’ of names. Based on Kohli and LaBahn’s research [33], in a prescriptive article Kohli and Thakor [5] discussed the suggested steps, but prefaced the steps by suggesting that the general type of name per TM definition (see Section 4.7) be selected first. Generic names need to be avoided, of course, but this step is questionable as it may unnecessarily limit the creative scope of new name generation as ultimately what matters is the effectiveness of a name [36]. Some names generated may not initially be ideal for TMing, but with modification may be TMed [35].

Kollmann and Suckow [28], after preliminary interviews, formulated a questionnaire and surveyed e-entrepreneurs about the process they used to create their new corporate name. The availability of a domain name was most important, before TM availability, and two new steps of checking domain availability and domain registration were added before TM registration. All respondents set objectives for the new name as the first step, but it was found that one of two processes were then followed: the classical step-by-step approach of Kohli and LaBahn [33], or a new, iterative, approach in which a name is chosen (for example through brainstorming), quickly checked for domain availability, discarded if not suitably available, go back to generate and choose another name, check domain availability, if available, continue with evaluation against objectives, and if it meets the objectives, proceed with domain registration and TM registration.

Kollman’s and Suckow’s [28] results are valuable for the light they shed on the influence of the Internet in brand naming decisions and their results have implications beyond the subject of e-entrepreneurs’ corporate name creation. Their paper outlines the additional burden of requiring both domain registration and TM registration for a new name, as well as the influence of the international scope of the Internet, with no traditional boundaries. They suggested that more ‘coined’ (made-up) names may arise in response. Their research has not been extended to examine if this new, iterative process is used beyond the realm of e-enterprises, or for the naming of new products or services rather than just company names. Their results cannot be generalized.

Academic research progress on the brand name creation process appears to have since stalled. Much detail remains unknown of the current processes and techniques that private sector, branding specialists now use to create new brand names. More research is required to understand the influence and role of the Internet and the use of domain names. The Internet globalizes information. Is a dedicated registered domain name considered a necessity for a new brand name? Is the consideration different if a fruit brand is to be sold globally or regionally? At which step of the brand name creation process is domain name availability considered? The brand name creation process is also silent on the use of social media accounts that require the availability of a unique account name, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, Pinterest, and Snapchat. Are social media accounts taken into consideration in the naming process and at what stage?

The use of Internet domains and social media accounts, with their particular emphasis on visual marketing, is a marketing decision and must be considered at some point in the name creation process, likely as part of the objectives and name criteria stages, and during the name evaluation stage at the very least. Other gaps in the literature include the role of, and impact on, brand name decisions of: Online grocery shopping, chat bots, digital assistant and voice searches (Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant, for example), ‘smart’ refrigerators, and the world of virtual or augmented reality. For example, can the brand name be easily recognized and understood by the voice search: ‘Alexa, please add Staccato cherries to the grocery list’?

Within the fruit industry, there is an additional brand name creation challenge: a TM for a fruit varietal must be different from the varietal (generic) name (or the names of any other closely related fruit varietals). The varietal name is called a plant variety denomination (PVD) (see Section 4.7). This need for a double search (TM search and varietal name search) can make achieving uniqueness highly challenging, even when excluding any domain name and social media account name considerations.

The research reviewed gives the broad steps of the name creation process and the need for research into the impact of the Internet, social media, and other technologies on the brand name development process. It is our contention that another gap in the literature exists, hinted at by Lefkowith and Moldenhauer [36]: Preliminary research. It is unknown the extent to which preliminary research is conducted during the brand name creation process. In prior research, it has been implied that there is already thorough knowledge of the consumer market in which the new brand name will compete, including other brand names. However, in today’s competitive marketplace, general knowledge needs to be made explicit to assist with name creation.

In the next section, we provide details of the classical step-by-step brand name creation process, situating it in the context of fruit branding.

4. Step-by-Step Instructions for Creating a Brand Name to Market a New Fruit Varietal

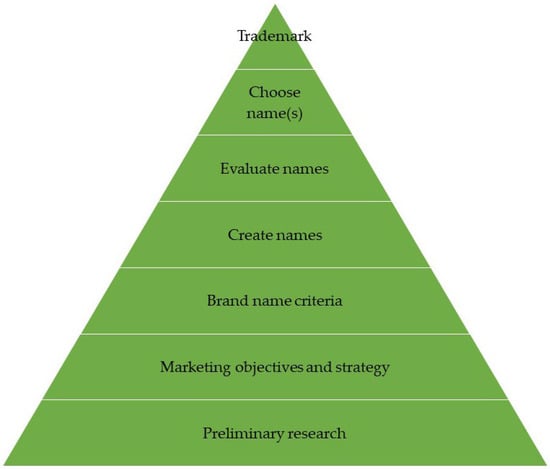

Figure 1 outlines the classical steps to create a new brand name, with the addition of a preliminary research step. It is in the shape of a pyramid to emphasize the importance of the early steps in building a strong foundation upon which the later steps can then rest securely.

Figure 1.

A step-by-step process proposed for the creation of brand names for fruit varieties (Source: Pyramid structure, authors’ own; content of pyramid [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]).

In general, the process begins with preliminary research, then setting the broad marketing objectives, followed by specific brand name objectives and strategy for the new product, then by the selection of the brand name criteria, the creation of candidate names, internal and external evaluations, and ending with final candidate selections and TMing as discussed in the subsections listed below.

4.1. Preliminary Research

Expanding on the suggestion that background research provides key information about what is important to consider for a new brand name [36], it is our contention that an explicit preliminary research step is necessary at the very beginning, before starting the brand name development process as proposed by others. Here, we propose specific consumer research and the creation of a formal lexicon. Context is important: Conduct research in the markets/cultures that are the intended targets.

4.1.1. Conducting Consumer Research

The language used by consumers can provide clues of how they think and feel about the type of fruit in question. Thoughts and emotions, the cultural context of foods—extrinsic factors—may provide fodder for the creation of a new brand name.

Humans eat not just to directly meet physiological needs. Eating is also influenced by the foods themselves and the context of consumption, both social and physical, and is affected by and associated with emotions [39]. Desmet and Schifferstein [39] suggested five sources of food emotions, both direct and indirect: sensory attributes, experience consequences, anticipated consequences, personal or cultural meanings, and actions of associated agents (an associated agent could be a restaurant chef, for example). Exploring these sources of food emotions may yield meaningful information for brand name creation and provide a deeper frame of reference for a particular fruit.

Understanding how consumers buy, prepare, and eat a fruit helps provide a foundation of knowledge about it and the context in which consumers use it. What is the subtext when consumers talk about oranges? Are oranges eaten for utility or pleasure or both? Are certain fruits eaten out of necessity or choice? This research may provide information on behaviour (always buying whichever pear is cheapest, for example) or infer the emotional aspects of product purchase and consumption (loving the crisp snap of biting into an apple; a peach cobbler that reminds someone of their grandmother, for example). Additionally, what are the perceived negative attributes of a particular fruit and its consumption? Negatives can also provide insights. One small study indicated that eating an apple did not increase any feelings of joy, but did increase mood, compared to pre-consumption, and in contrast eating chocolate did increase feelings of joy, but some participants also felt an increase in feelings of guilt [40].

What are the words, emotions, images, symbolisms, and values, etc., associated with a fruit? Emotional valence is a major semantic dimension [41] and can be utilized to create a new brand name to differentiate a new varietal. Given that intrinsic attributes of different fruit varietals may be very similar, emotional and symbolic values may be even more important in creating a new brand name.

4.1.2. Creating a Formal Lexicon

Results of the previously recommended consumer research can now be used to help create a formal lexicon for a fruit. See “Developing Lexicons: A Review” by Lawless and Civille [42] in context of sensory research, but note that not just a traditional sensory research lexicon needs to be created. Which and how many emotions can be investigated via food-specific emotion and feeling lexicons [43]. These lexicons can be consumer-led approaches, linguistics-based ‘expert’ approaches, or a combination thereof [44]. See also King and Meiselman [45] and Prescot [46] for further information on emotional lexicons for food or drinks.

Language is a strategic tool in brand communications and brand management [47]. Morais and Lerman [47] advocate for a brand language audit of a product category and a subsequent creation of a brand language brief, specific to the product in question. The brand language audit examines and inventories the language and linguistic devices used by competitors in their marketing communications, also encompassing their brand names. This inventory can reveal how and to what extent competitors are using language to differentiate themselves and where opportunities may lie. They recommend that the audit also covers the message being communicated. Then, a strategic brand language brief can be developed, based on marketing and communication objectives specific to a brand that details the language to be used when communicating about a product, including the brand name.

It is helpful to review not just the brand names, but the types of brand names currently in the marketplace, not just for elimination, but to understand the types of names that are usually used, which creates a quick understanding for consumers, a familiarity, but also possible opportunities for distinction in lesser used name categories. Rickard et al. [25], for example, categorized most apple names into three category types or combinations thereof: namesake, sensory, and appearance. Not all apple brand names fit these categories: See Arora et al. [48] for a more comprehensive framework for brand name classification.

In general, the effectiveness of different brand name types and categories has been somewhat explored [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. However, research is required to identify the impact, if any, of different brand name categories on consumer perceptions of fruit quality and their purchase decisions [25].

A formal lexicon and brand language brief provides context for the types of words to choose, words that imply a particular ‘tone’ or emotion, for example, without necessarily providing exact words to use. A brand language brief is a living document that will need occasional updating [47], but it can be used repeatedly to assist new name creation and subsequent marketing communications.

4.2. Marketing Objectives: Brand Name Objectives and Brand Name Strategy

The main questions that should be considered at the earliest stage of creating a new brand name are listed below:

- What are the broad objectives of the new product? [5,30,31,32,33,34,35]

- What is the market position of the new product and can the name assist in positioning (the most important objective per Kohli and LaBahn [33]?

- What market segment (new or otherwise) is it expected to compete within? (Red grapes, black grapes, green grapes? Specific disease resistance? Early maturing, late maturing? Drought resistant? A particular flavour segment? A particular consumption segment (snack, cooking, for example)

- Does it need a distinctive image, and if so, what should that image be? [30,31,32,33,34,35]

- Where will the product be marketed: locally, regionally, globally?

- Who will it be marketed to? This may include nurseries, growers, wholesalers, retailers, as well as consumers. All? One? Two?

These considerations impact the brand name decision, including TMing. Specific brand objectives, brand name strategies, product attributes and market positioning topics related to this section are discussed in more detail below.

4.2.1. What Are the Specific Brand Objectives?

Food manufacturing executives rated the following objectives for a brand name, in decreasing order of importance: establish product acceptance, establish consumers’ brand loyalty, establish a particular image, establish marketing position, establish brand reputation, establish product differentiation, and establish market segmentation [30,31]. Kohli and LaBahn [33] found companies emphasized the following in declining order of importance: (1) convey intended positioning, (2) establish differentiation, (3) establish a distinct segment, (4) establish a distinct image, (5) identification only, and (6) ease of TM registration.

Specific objectives for a new brand name will be unique to the product and its market. Establishing these objectives is important for eventual evaluation of candidate names. It is unlikely a name will meet all objectives, or all objectives well, so key objectives need to be formed versus lesser ones, and the name must be eligible for TM registration [35].

4.2.2. What Is the Brand Name Strategy?

The brand strategy is the methods selected to achieve the brand objectives. The strategy may impact the choice of names. For example, a descriptive or suggestive name usually allows consumers to infer product attributes, but an arbitrary or a made-up name does not immediately provide consumers with information about the product and may require higher marketing expenditures to establish the new brand [5,57,58].

Traditional food manufacturers may need to decide if the product will carry the manufacturer’s name (Kraft), the retailer’s name (Tesco) or other private label name (President’s Choice), or a generic name [30,31]. Fruits are different than manufactured foods. Particularly with apples, varietals partially took the place of brands in the past [25]. Will the varietal name be provided to consumers or not? Should the product be named individually, use a primary brand ‘family’ or ‘umbrella’ name (e.g., Melinda®), or a combination thereof (e.g., Melinda® + apple brand name) [30,31]. Is the new varietal part of a brand line extension? Will other names, such as the fruit packer’s or growers’ names, be present or not on labelling and packaging?

How will the new product be introduced? Is there a large marketing budget or not? Where will the marketing be focused? Fully on consumers or also back down the supply chain? Will the name be formally registered as a TM (assumed these days)? Will there be a logo created to go with the name? Will marketing and promotion include the Internet and social media?

4.2.3. Product Attributes

What attributes does the varietal contain? Which attributes are strongest and which are weakest? What attributes are lacking? Are there “new” attributes that the varietal brings to the market that are desired by consumers (or that consumers can learn that they desire) or others along the supply chain? How does it compare to competitors’ attributes? Are the attributes extrinsic or intrinsic (e.g., organic or flavour)? Attributes are important to consider in the naming process as many names strive to infer or refer explicitly to beneficial varietal attributes.

4.2.4. Market Positioning/Market Niche

Based upon the varietal’s characteristics, what is its intended position in the marketplace? Product mapping using consumer mapping techniques is one method to see where it fits in key dimensions that are important to consumers vis a vis competitive products. What is the new varietal’s position on intrinsic attribute scales, identified using descriptive sensory analysis, compared to other varietals? Where is its position compared to competitors on its consumer acceptance, determined using consumer research methods? See Cliff et al. [59] for an example of this type of research. Identification of market segments, based on intrinsic and extrinsic quality attributes of a fruit variety, is also important for the proper positioning of new fruit varietals in a competitive market [60]. Beyond sensory attributes, there may be other intrinsic properties that may be important to market position, such as oxidation/browning properties, and ‘shelf life’ (how long the fruit stays fresh and edible). For example, the attributes of juiciness and crispness may be prioritized by consumers and a number of apple varieties may score closely on those attributes, but a distinct advantage in non-browning properties may give one varietal an advantage.

Market positioning is important as an aid to help consumers understand a product. Consumers use categorization to group products with similar features [21]. Some research has suggested that a category label may have greater influence than attribute similarity in consumer categorization and inference tasks [61] and that the category label applied to a product may also influence how that product is evaluated [62,63]. Furthermore, category beliefs may be transferred to a new product and that product’s actual attributes could be overlooked if they do not fit with the category [64].

For example, any new apple varietal introduced to the marketplace is automatically categorized by consumers as an “apple” and depending on skin colour, may be further categorized. With the dominance of the Granny Smith varietal in the green apple category, any new green apple introduced may automatically be expected to be similar in attributes to the Granny Smith [65], even if it is much sweeter and less tart. Moreau et al. [62], using a non-food product, also found evidence of an order effect: the first plausible category label provided for a new product significantly influenced consumers’ categorizations, expectations, and preferences. The first plausible category was evaluated as the most appropriate and results suggested it is somewhat resistant to change. Thus the brand name for a new, sweet, green apple would need to be carefully crafted to help overcome any automatic categorization of green apples as tart.

4.2.5. Brand Image

Another part of market positioning is deciding on a brand image. What ‘character’, tone or ‘personality’ do you want to project and what do you want to communicate with the name [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]? Examples of brand names that help create a brand image and support brand positioning and marketing are Sunkist® oranges [57], Honeycrisp apples, and Cuties® mandarins.

4.3. Selection of Brand Name Criteria

What are the desirable characteristics of a brand name that will help achieve the brand objectives? After surveying British consumer goods and foods manufacturers, Shipley et al. [30,31] identified four main groups of brand name characteristics: (1) those concerning communicability (e.g., memorability), (2) those concerning consumer needs (e.g., positive connotations), (3) those concerning image (e.g., compatibility with product image), and, (4) those concerning versatility (e.g., versatile among advertising and promotion media). Separately, TM availability also ranked highly in Shipley’s studies.

Respondents to the Kohli and LaBahn [33] survey, who included US consumers and industrial goods manufactures, indicated in declining order of importance the following 13 criteria: (1) relevance to product categories, (2) positive connotations, (3) overall liking, (4) ease of recognition, (5) distinctiveness, (6) ease of recall, (7) consistency with the company image, (8) ease of TM registration, (9) ease of pronunciation, (10) consistency with existing product lines, (11) avoidance of profane or negative connotations, (12) versatility for use with other products, and, (13) carrying over well to other languages. In their survey, respondents did not specifically preselect brand name criteria before the name generation, but considered them during the evaluation stage. There were no significant differences in brand name criteria between consumer and industrial goods manufacturers.

In the e-commerce/Internet sector, survey respondents, who were e-entrepreneurs creating new corporate names, identified domain name availability as the third most important criteria after ease of recall and ease of recognition, respectively [28]. Ease of TM registration was rated the least important criteria out of twelve [28].

More recently, Hsu and Lin [66], who were developing a decision model for naming, suggested four overall categories of brand name criteria: emotional appeal, linguistics appeal, marketing appeal, and legal appeal.

4.4. Creating Names

Kohli and LaBahn [33] found that 46 names were created on average during the name generation process. That number is clearly insufficient. In the 100s, up to 500, should be initially generated [35,36], especially given the burden of meeting TM eligibility and avoiding PVDs.

Generating new brand names is a creative task, and despite the consumer and language research that can provide clues and prompts, the creative process should not be restrained in any manner [35]. Candidate names and naming ideas can come from brainstorming group discussions, individual efforts, ‘eureka’ moments, word association, reference books, names held in reserve, consumer research (focus groups), computer generation, input from all employees or departments, writers, linguists, advertising agencies and name specialist agencies, market researchers, wholesalers, retailers and customers, existing company product names, and purchased from other companies [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Kollmann and Suckow [28] indicated that many entrepreneurial respondents used an ad hoc, brainstorming process, often with family and friends to generate names for their new company. Kohli and LaBahn [33] survey results indicated that brainstorming and individual creative thinking were ranked as the most useful approaches.

One suggestion if employing external writers: Provide them with a framework that summarizes the product benefits and target market, but do so blindly by not providing any company or confidential information [35]. Linguists, regularly employed by specialist naming agencies, can create names or contribute to the creation of a name by proposing words, roots, stems, metaphors, rhythm, and sound symbolism, for example [34,67].

4.5. Evaluation

For a successful evaluation of proposed brand names, names should not be eliminated too quickly and personal and other biases must be kept out of the process [35]. Sticking to the brand name objectives, strategy, and name criteria is necessary [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Evaluation must include screening for profanity and negative associations, especially in multiple languages if the target market(s) is multi-lingual or may expand internationally.

In practice Kohli and LaBahn [33] found that most companies conducted very little brand name testing against their stated criteria: Only 45% evaluated names using qualitative methods and only 35% used surveys with an average sample size of only 74. Companies stated that objective evaluation was often curtailed due to time pressures. This should be avoided.

Kollman and Suckow [28] detailed an alternative, fast, iterative, short-cut name availability technique (see Table 1) before evaluating names. We detail the iterative step-by-step evaluation processes proposed by Opatow [35] and Hsu and Lin [66].

4.5.1. Initial Elimination of Names Clearly Unsuitable

One person or a small team can perform this step. The initial list of names needs to be pre-checked against a list of PVDs and brand names (whether TMed or not). Names should be eliminated conservatively, only if already in full use or clearly do not meet a key objective, and names similar to current names should remain as they may end up acceptable or modifiable [35]. A brief analysis of each name, with rationale, pros and cons, root words, ideas and inferences is recommended [35].

4.5.2. Internal Evaluation against criteria and objectives

Shipley et al. [30,31] suggested that internal staff from various departments initially verify that candidate names meet objectives and criteria before turning to marketing and advertising agencies that then screen the candidates against packaging, advertising, market impact, etc., considerations. Opatow [35] suggested an iterative, group approach at this stage: All people involved in the naming process meet to evaluate names, individually crossing off names they absolutely cannot accept, but avoiding quick decisions. Crossed off names are discussed before any permanent removal, followed by a discussion, based on objectives and criteria, of the remaining names. It can take multiple rounds to agree on a shorter list of candidate names [35].

In a more formalized iterative procedure, Hsu and Lin [66] developed a decision model for brand naming using the Delphi method [68] and the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) [69] to evaluate and select appropriate brand names for a Taiwanese beverage company’s new product. They used the Delphi method to identify suitable criteria for brand name evaluation, then AHP was applied to determine the relative weights of the evaluation criteria, rank the alternatives, and select the optimum name.

4.5.3. Preliminary TM and PVD Review

A preliminary legal review before going to external testing is appropriate at this step to eliminate names that ultimately cannot be used (keeping in mind that some names may be modifiable to meet legal requirements), and to avoid further, needless, expensive testing [35]. The TM legal review may need to cover a number of different countries or jurisdictions. The review must also encompass existing PVDs for closely related varieties (e.g., within the same genera)—whether on official lists of varietal names or not—since they cannot be registered as a TM within Nice Class 31 for fresh fruit. Domain names may also be reviewed at this stage [28], as well as potential social media account names, if part of the branding and marketing plan.

After this stage, a short list of candidate names proceeds to the external review stage. The number of names to undergo external evaluations may be limited by budget considerations, and the number of, and quality of, names initially generated.

4.5.4. External Review: Consumers, Retailers, Distributors, Growers

External testing includes qualitative and quantitative research, ideally with consumers who buy a fruit, such as grapes, frequently as well as those that do not (presuming budget allows). Frequent buyers, with their greater experience with purchasing and eating grapes, will likely have different beliefs, including inferential beliefs, versus infrequent buyers. For example, a low frequency buyer may not hold strong beliefs about typical and atypical brand names (or have less inferential beliefs), whereas frequent buyers, with their high interest in grapes, are more likely to have a favourable attitude to a new, yet typical brand name [19]. One caveat is that Zinkhan and Martin [19] assumed high involvement information processing, which consumers are less likely to use when buying fruit, but are highly likely to use when purchasing a new computer, for example.

Names need to be tested on their own, visually and aurally. Then, with the product available to view (either in person or via photo), then via taste, with and without the skin (if appropriate). Names should also be tested with their initial concept designs (such as logos, tag lines, packaging) as “it places the final candidate names in a realistic context that provides a more valid basis for consumer research or management evaluation” [36], (p. 76).

Overall, the preference is for congruency between expectations and inferences created by the brand name of a new product and what the product actually delivers [7,53]. If expectations and beliefs are contradicted in the grocery store or upon eating, an unfavourable reaction may wipe out any initial advantage bestowed by a name. The name, alone, may not lead to an increase in the probability of purchase and repurchase. Other factors must also be congruent, such as logos, packaging and price. Intrinsic factors, such as texture and flavour, must also meet or exceed consumer expectations.

An external review should at the very least test recognition of the name, recall of the name, overall liking of the name, ease of pronunciation, and inferential beliefs based upon the name. Is there confusion about the name or unfavourable connotations? In particular, how well does it match the objectives and criteria set forth?

Quantitative word association tests, measurement of relative interest (involvement) [70], or a quantitative survey to uncover inferential attitudes and beliefs [19], are a few examples of methods that could be used for external evaluations.

4.6. Choosing a Name(s)

After testing, a further iterative process of elimination takes place, again adhering to the naming objectives and criteria [35]. This can be a panel process again or the previously mentioned modified Delphi method with AHP could be considered [66]. A final hierarchy of names is selected, with the top name(s) going forward for full TM review and registration and the remaining names kept in reserve, if appropriate for future use.

Surprisingly, Kohli and LaBahn [33] found that when it came to choosing a final brand name, only 79% of respondents explicitly applied their stated objectives, suggesting that brand naming did not receive appropriate attention given its high importance to the success of a product. They also noted, “the costs of shortcutting the process are unknown and extremely difficult to estimate” (p. 73), but found that companies that had followed the process more often were more satisfied with the outcome and their products were more successful.

4.7. Creating TM-Able Brand Names for Fruits

A TM can include any word, phrase, symbol, or design, or combination thereof, to identify and distinguish goods (and services) from those manufactured (or grown) or sold by others [71]. In some cases, non-traditional marks, such as a sound, scent, colour, flavour, texture, motion, multimedia format, or hologram may be registered [72]. The European Union defines the following types of TMs: A word mark, a figurative mark, a figurative mark containing word elements, a shape mark, a shape mark including word elements, a position mark, a pattern mark, a colour (single) mark, a colour (combination) mark, a sound mark, a motion mark, a multimedia mark, and a hologram mark [73].

The ™ symbol refers to an unregistered, common law, claim of a TM. The ® symbol refers to only officially registered TMs. Both symbols signify ownership, the source, of the mark in question. The use of the ™ symbol, although widely used in Canada, the USA, and the UK for example, is not universal. The ™ symbol should only be used if the proposed TM meets the requirements set out by the applicable country’s intellectual property office requirements, even if there is no intention to formally register it as a TM. Registration of a TM provides a higher level of protection than unregistered TMs. A comprehensive TM search encompasses unregistered common-law TMs, not just registered marks. Note that, in jurisdictions where the ™ symbol is allowed to be used, registered TM owners can always choose to use the ™ symbol instead of the ® symbol, but an unregistered TM owner may never use the ® symbol. Depending on budget, a TM may be registered in some countries, but the mark’s owner may rely on using the ™ symbol in other countries in which they have yet to register or cannot afford to register.

The TM application and registration may be done on a national (country), regional (Benelux, European Union), or international (Madrid System) basis. Where a product will be marketed is a key consideration to choosing where to file for a brand name TM. Different names may be necessary for different countries because it is rare for a new brand name to have desirable characteristics in every language, or to be available in all desired countries.

4.7.1. TMs versus PVDs

TMed names are not the same as, and cannot be the same as, the names of agricultural seeds, live plants, fresh fruits, and fresh vegetables for closely related varieties (e.g., usually in the same genera). The PVD is the generic name of the seed or plant and is used to describe to the public a plant or seed of a particular sort, not a plant or seed from a particular source [74]. TMs must be distinctive and unique, by definition not generic.

Under the rules of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), a new plant variety is given a unique PVD. It is the name that should be used in a plant patent or plant breeder’s right, serving an identification function (See Martinez Lopez [27] for a good overview of the roles of PVDs versus TMs). One plant, one name worldwide, and the avoidance of synonyms and homonyms, are the goals of the UPOV and PVDs. Even after a plant patent or plant breeder’s right expires, the PVD still remains attached to that plant variety permanently, as its generic name. It outlives the patent or rights, and may not be used as a TM name (except in some extremely limited circumstances) [27]. An unregistered, common generic name for a plant also may not be TMed.

In the EU, it is mandatory to use the PVD when breeders, growers, nurseries, etc., offer or sell propagating materials, but it is not mandatory when selling the harvest of the said plant to consumers (e.g., fruits or flowers) [27].

4.7.2. TM Considerations in the Creation of New Fruit Brand Names

Brand names need to be sufficiently distinctive to be considered for TM registration. Registration may be denied on the basis of likelihood of confusion, mistake, or deception as to the source of a good [57,75]. Identical marks for goods that are not related nor marketed in a similar manner, may be permitted if confusion as to source is unlikely.

There are five levels of intrinsic TM strength, based on a continuum of distinctiveness, from weakest to strongest: generic, descriptive, suggestive, arbitrary, and coined or ‘fanciful’ [5,57,76]. Suggestive, arbitrary, and coined marks are referred to as inherently distinctive and are registrable without proof of acquired distinctiveness [76].

Generic words cannot be TMed. A generic word can refer to a fruit category (blueberry, cherry, orange) or specific varietal of a fruit (the PVD). They are incapable of denoting a distinct source. However, when teamed with another word(s) that makes the overall name more unique and distinctive, there is a possibility they may be accepted for TM registration [57]. Kordes’ Rose Monique® has been granted TM status for roses in the EU even though ‘Monique’ is the PVD for the rose [27].

Descriptive words are considered a weak category for TM because they lack inherent distinctiveness that can indicate a particular source (rather than a product or category) [57]. A mark is considered merely descriptive if it describes an ingredient, quality, characteristic, function, feature, purpose, or use of the specified goods [76]. Descriptive words are often denied TM on the grounds that they do not have acquired distinctiveness and/or secondary meaning (‘sweet’ and ‘juicy’, for example, on their own cannot be TMed). Descriptive marks are often not protected to prevent the inhibition of competition in the sale of particular goods and to maintain the freedom of the public to use the language involved [76].

Due to the poor protection inherent in descriptive TMs, the same descriptive words may, in combination with other words, be accepted for similar products [57]. For example, the descriptive word ‘sweet’ is often paired or blended with another word in TMed fruit brands. Consumers may not confuse the source, in legal terms, but in marketing terms these names may not be ideal as their semantic meaning is identical and consumers may treat them as substitutable.

Suggestive words are words that suggest attributes of the product or service without saying it explicitly. Suggestive TMs “require imagination, thought, or perception to reach a conclusion as to the nature of those goods or services.” [76] (Section 1209.01(a) paragraph 3). They can be difficult to distinguish from descriptive words. Incongruity, where at least one term is not quite in harmony with the others, is considered an indication that a mark is suggestive rather than just descriptive [76]. An example of a suggestive brand name is Microsoft® or the tuna brand Chicken of the Sea®.

Arbitrary TMs use word(s) that have meaning, but no association to the product. Staccato® cherries and Rugby™ grapes are examples of arbitrary brand names. An arbitrary mark can provide strong distinctiveness, but with no natural association with a product, greater marketing efforts may be required to familiarize it to the public [49,57].

Coined or fanciful names, consisting of made-up words and/or numbers that have no prior meaning, make the strongest TMs [57,76]. Words that are completely out of common usage or are unknown in the language are also considered fanciful. Similar to arbitrary names, coined names may require higher expenditures to establish the brand name with consumers. Examples of coined brand names are Kodak®, and Pepsi®. An advantage of a coined name is that it has no prior meaning and is more likely to be usable in multiple languages and countries.

Different national TM regulations may have different interpretations of which words and names fall into which categories, and they may also use different criteria to categorize names. TM registration is nuanced and not as simple as it may appear.

4.7.3. Avoiding TM Genericide in the Use of Fruit Brand Names

TM genericide occurs when a mark through improper usage becomes identified as the product itself, its generic name, rather than the unique source of the product, thereby invalidating the mark. Examples of genericide include the former TMs ‘escalator’ and ‘flip phone’ (previously held by Otis Elevator and Motorola, respectively). Brand name dominance can be a double-edged sword: If consumers and/or the trade confuse a TM as a fruit varietal name, TM rights can be cancelled [27].

Consumers that have known some fruits, such as apples and pears, by their varietal names may confuse a TMed brand name with a varietal name, especially if no varietal name is also provided at the point of sale, or on labels or packaging. The apple brand Pink Lady® has been refused TM registration as a plain word mark in Australia as it is viewed as descriptive of the apple itself, widely known by the public, rather than by its various PVDs [27]. In Australia, the solution was to create a moat or deterrent around the Pink Lady name by registering it as a plain word mark for fruits other than apples [27]. Industry practice can also lead to genericide: The TM Scarlet Spur, an apple brand, was deemed generic and cancelled in the United States because, in part, it had become known to growers as the name of the cultivar [77].

Creeping misuse along supply chains of a TMed brand to refer to a varietal itself can easily happen when the TMed brand name becomes better known within the industry than the varietal name; when varietal names are not always clearly provided on fruit wholesaler order forms and websites; and when varietal names are hidden from consumers.

The careful and appropriate use of TMs and PVDs may help prevent genericide. It is up to the TM rights holders to ensure proper use of their mark, but the fruit industry as a whole can help ensure proper usage. Table 2 outlines some common methods to distinguish PVDs from TMs. These methods do not guarantee avoidance of genericide in and of themselves, but assist in preventing confusion that may otherwise lead towards genericide.

Table 2.

Methods to distinguish PVDs from TMs.

Advertising, websites, labels, social media, nursery catalogues, and other marketing materials and communications, in-house or external, should be scrutinized to avoid and correct improper use [78]. TM rights holders can create and make easily available, clear brand name guideline documents to encourage proper TM usage.

Using a strategy of a ‘family’ brand name (e.g., Zespri®) or a primary TMed ‘umbrella’ brand name with brand line extensions (the series of Redlove® and Lucy® brand red-flesh apples) that indicates the source of a number of different varieties may help prevent problems because the brand name is more clearly a source of fruit, not a sort.

If a fruit cultivar becomes primarily known by its brand name, none of the above methods can guarantee the prevention of genericide. If a TM is cancelled, exclusive use ceases, and the brand name may be used by anyone, which can then lead to the destruction of the brand equity built through the TMed brand.

Meaningless generic names, consisting of nonsensical code letters and numbers [79], contribute to incorrect use within the fruit industry of inherently more memorable TMs as the easiest way to remember and identify varieties [27]. If codes must be used for PVDs, instilling some meaning and keeping them short might help, such as found in PVDs using a letter code for the region or breeder of origin (for example) plus a short number (‘WA38’, ‘Scifresh’, ‘Scilate’). See Martinez Lopez [27] and Spencer and Cross [80] for a discussion of plant labelling systems and the need to avoid the confusion surrounding botanical, PVD, and trade names.

5. Conclusions and Future Considerations

Our review of the brand name creation process indicates a lack of recent research on the topic. We hypothesize that this is likely due to the monetization of the process by professional marketing and branding agencies whose research on, or development of, the process is often proprietary and private. Although directly relevant research on the brand name creation process for new fruit varietals is not available, this review shows that the process is highly adaptable to branding new varietals and lays out a clear, step-by-step progressive method for creating a new brand name.

We proposed an extra step in the process to detail some of the preliminary research that is important in the brand name creation process. Further research is required to discover if and to what extent such research is actually conducted and which preliminary research methods are utilized.

A study specifically on the brand name creation process in the fruit industry would be most relevant, current, and helpful. Does the industry follow the steps we’ve described, or not? How might the process differ? In addition, the globalization of information makes branding more difficult: Research is required to understand the role and impact of the Internet, social media, and other technological advances on the naming process. Future studies are needed on these topics. Finally, this paper reviews the English language literature studying brand name creation and it cannot be assumed the process is similar globally.

Conducting preliminary research, adopting specific objectives and criteria for a new brand name, and evaluating candidate names against such, can help to reduce the risk of brand name ‘misses’ and ‘errors’, or an indifferent name. This review indicates that it is a challenging process taking considerable time and effort.

A unique challenge in creating TM-able brand names for a new fruit varietal compared to other consumer foods or products is the need for two names: the generic, PVD which must be unique from other varietals, and the TM brand name, which must be different than the PVD or any other PVDs of similar fruit. Given the growing importance of TMs in fruit varietal branding (and possibly increasingly of domain names), the steps outlined allow for a balance of name-generation creativity against the need to register a TM or domain name.

Finally, even after a new brand name has been successfully TMed, continual effort is required to protect the TM rights, including from genericide. Readers are advised to consult with TM agents, attorneys and specialists for more comprehensive information and assistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and J.A.; methodology, J.A. and M.B.; formal analysis, J.A.; writing—original draft, J.A.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and J.A.; supervision, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Agricultural Partnership Fund in collaboration with the British Columbia Fruit Growers’ Association (CAP; ASP-005 BCFGA Activity #5).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Erin Wallich for critically reviewing earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the result.

References

- Canavari, M. Marketing Research on Fruit Branding: The Case of the Pear Club Variety “Angelys”. In Case Studies in the Traditional Food Sector, 1st ed.; Cavicchi, A., Santini, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallich, E. Personal Communication; Summerland Varieties Corporation: Summerland, BC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Danesi, M. What’s in a Brand Name? A Note on the Onomastics of Brand Naming. Names 2011, 59, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, P.; Zhang, S. The Mental Representation of Brand Names: Are Brand Names a Class by Themselves? In Psycholinguistic Phenomena in Marketing Communications, 1st ed.; Lowrey, T.M., Ed.; Psychology Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, C.; Thakor, M. Branding Consumer Goods: Insights from Theory and Practice. J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelis, V.; Rigopoulou, I. The Influence of Brand Name to Brand’s Success. Eur. Res. Stud. 2003, 6, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L.; Vipat, P. Inferences from Brand Names. In E-European Advances in Consumer Research; Van Raaij, W.F., Bamossy, G.J., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 534–540. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/11631/volumes/e01/E-01 (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Richards, T.J. A Discrete/Continuous Model of Fruit Promotion, Advertising, and Response Segmentation. Agribusiness 2000, 16, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.M.; Richards, T.J. Newspaper Advertisement Characteristics and Consumer Preferences for Apples: A MIMIC Model Approach. Agribusiness 2000, 16, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, F.R.; Gunson, F.A.; Jaeger, S.R. The Case for Fruit Quality: An Interpretive Review of Consumer Attitudes, and Preferences for Apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2003, 28, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.C.; Jacoby, J. Cue Utilization in the Quality Perception Process. In SV—Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research; Venkatesan, M., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; pp. 167–179. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/11997 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-end Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enneking, U.; Neumann, C.; Henneberg, S. How Important Intrinsic and Extrinsic Product Attributes Affect Purchase Decision. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symmank, C. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Food Product Attributes in Consumer and Sensory research: Literature Review and Quantification of the Findings. Manag. Rev. Q. 2019, 69, 39–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.C. Encoding Processes: Levels of Processing and Existing Knowledge Structures1. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Olson, J.C., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Ann Abor, MI, USA, 1980; Volume 7, pp. 154–160. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/9667/volumes/v07/NA (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are Product Attribute Beliefs the Only Mediator of Advertising Effects on Brand Attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivetz, R.; Simonson, I. The Effects of Incomplete Information on Consumer Choice. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.L.; Ross, B.H. Uncertainty in Category-Based Induction: When Do People Integrate Across Categories? J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2010, 36, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkhan, G.M.; Martin, C.R., Jr. New Brand Names and Inferential Beliefs: Some Insights on Naming New Products. J. Bus. Res. 1987, 15, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncy, J.A. Measuring Perceived Brand Parity. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Corfman, K.P., Lynch, J.G., Jr., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1996; Volume 23, pp. 411–417. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/7869/volumes/v23 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Hoegg, J.; Alba, J.W. Linguistic Framing of Sensory Experience: There is Some Accounting for Taste. In Psycholinguistic Phenomena in Marketing Communications, 1st ed.; Lowrey, T.M., Ed.; Psychology Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Joubert, J.P.R.; Poalses, J. What’s in a Name? The Effect of a Brand Name on Consumers’ Evaluation of Fresh Milk. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Brown, S.P. Effects of Brand Awareness on Choice for a Common, Repeat-purchase Product. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.K.; Sharp, B.M. Brand Awareness Effects on Consumer Decision Making for a Common, Repeat Purchase Product: A Replication. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 48, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, B.; Schmit, T.; Gomez, M.; Hao, L. Developing Brands for Patented Fruit: Does the Name Matter? Agribusiness 2013, 29, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wänke, M.; Herrmann, A.; Schaffner, D. Brand Name Influence on Brand Perception. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Lopez, A.H. The Interface between Trade Marks and Plant Variety Denominations (PVDs): Towards Clearer Coexistence at the International and EU Level. 2021. Available online: https://cpvo.europa.eu/en/news-and-events/articles/interface-between-trade-marks-plant-variety-denominations-towards-clearer-coexistence-international-and-eu-level (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Kollmann, T.; Suckow, C. The Corporate Brand Naming Process in the New Economy. Qual. Mark. Res. 2007, 10, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeal, J.U.; Zeren, L.M. Brand Name Selection for Consumer Products. MSU Bus. Topics 1981, 29, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, G.J.; Hooley, J.; Wallace, S. The Brand Name Development Process. Int. J. Advert. 1988, 7, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, G.J.; Hooley, J.; Wallace, S. The Selection of Food Brand Names. Br. Food J. 1988, 90, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, D.; Howard, P. Brand-naming Industrial Products. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1993, 22, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, C.; LaBahn, D. Creating Effective Brand Names: A Study of the Naming Process. J. Ad. Res. 1997, 37, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L. A Name to Compare With: A Discussion of the Naming of New Brands. Eur. J. Mark. 1977, 11, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatow, L. Creating Brand Names that Work. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1985, 2, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowith, E.F.; Moldenhauer, C.A. Recent Cross-currents in Brand Name Development—and How to Cope with Them. J. Consum. Mark. 1985, 2, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexicon Branding. CMO Survey. 2019. Available online: https://www.lexiconbranding.com/media-1/cmo-survey-the-increasing-challenge-of-brand-naming (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Synder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.; Schifferstein, H.N. Sources of Positive and Negative Emotions in Food Experience. Appetite 2008, 50, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, M.; Dettmer, D. Everyday Mood and Emotions After Eating a Chocolate Bar or an Apple. Appetite 2006, 46, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, J.S.; Estes, Z.; Cossu, M. Emotional Sound Symbolism: Languages Rapidly Signal Valence via Phonemes. Cognition 2018, 175, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, L.J.R.; Civille, G.V. Developing Lexicons: A Review. J. Sens. Stud. 2013, 28, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmeur, A.; Guth, J.N.; Runte, M.; Siegrist, M. From Emotion to Language: Application of a Systematic, Linguistic-based Approach to Design a Food-associated Emotion Lexicon. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.; de Matos, A.D.; Fernandez-Ruiz, V.; Briz, T.; Chaya, C. Comparison of Methods to Develop an Emotional Lexicon of Wine: Conventional vs Rapid-method Approach. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.C.; Meiselman, H.L. Development of a Method to Measure Consumer Emotions Associated with Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J. Some Considerations in the Measurement of Emotions in Sensory and Consumer Research. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, R.J.; Lerman, D. The Brand Language Brief: A Pillar of Sound Brand Strategy. J. Brand Strategy 2019, 8, 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Kalro, A.D.; Sharma, D. A Comprehensive Framework of Brand Name Classification. J. Brand Manag. 2015, 22, 79–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, C.; Suri, R. Brand Names that Work: A Study of the Effectiveness of Different Types of Brand Names. Mark. Manag. J. 2000, 10, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Papp-Vary, A.F.; Lukacs, R. The Acronym as a Brand Name: Why Choose It for the Naming of the Brand and Why Not Choose It in Any Case? In Economic and Social Development (Book of Proceedings), Proceedings of the 83rd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development “Green Marketing”, Varazdin, Croatia, 2–3 June 2022; Luic, L.M., Martincevic, I., Sesar, V., Eds.; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2022; p. 17. Available online: https://esd-conference.com/past-conferences (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Lerman, D.; Garbarino, E. Recall and Recognition of Brand Names: A Comparison of Word and Nonword Name Types. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, R.R. Creating Meaningful New Brand Names: A Study of Semantics and Sound Symbolism. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2001, 9, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Heckler, S.E.; Houston, M.J. The Effects of Brand Name Suggestiveness on Advertising Recall. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, C.S.; Harich, K.R.; Leuthesser, L. Creating Brand Identity: A Study of Evaluation of New Brand Names. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Zhou, J.; Yu, J.; Soykoth, M.W. The Effect of Fancy Brand Names on Brand Perception and Brand Attitude of Young Consumers. J. Manag. Policy Prac. 2022, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.; Estes, Z.; Gibbert, M.; Mazursky, D. Brand Suicide? Memory and the Liking of Negative Brand Names. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, R.D. Naming Names: Trademark Strategy and Beyond: Part One—Selecting a Brand Name. J. Brand Manag. 2008, 15, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaei, M. Canadian Apple Retailer Survey. A Confidential Report Submitted to Summerland Varieties Corporation (Summerland, BC, Canada) and BC Fruit Growers’ Association; Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; pp. 1–125.

- Cliff, M.A.; Stanich, K.; Lu, R.; Hampson, C.R. Use of Descriptive Analysis and Preference Mapping for Early Stage Assessment of New and Established Apples. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2170–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejaei, M.; Cliff, M.A.; Singh, A. Multiple Correspondence and Hierarchical Cluster Analyses for the Profiling of Fresh Apple Customers using Data from Two Marketplaces. Foods 2020, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Markman, A.B. Inference Using Categories. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2000, 26, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.P.; Lehmann, D.R.; Markman, A.B. Entrenched Knowledge Structures and Consumer Response to New Products. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregan-Paxton, J.; Hoeffler, S.; Zhao, M. When Categorization is Ambiguous: Factors that Facilitate the Use of a Multiple Category Inference Strategy. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.L.; Ross, B.H. Predictions from Uncertain Categorizations. Cogn. Psychol. 1994, 27, 148–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, A.; Grygorczyk, A. Consumer Eating Habits and Perceptions of Fresh Produce Quality. In Postharvest Handling: A Systems Approach, 4th ed.; Florkowski, W., Banks, N., Shewfelt, R., Prussia, S., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 487–515. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.F.; Melewar, T.C.; Lin, F.L. Developing a Decision Model for Brand Naming using Delphi Method and Analytic Hierarchy Process. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2013, 25, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexicon Branding Creating a Brand Name. Available online: https://www.lexiconbranding.com/creating-a-brand-name (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Modern Science of Multicriteria Decision Making and Its Practical Applications: The AHP/ANP Approach. Oper. Res. 2013, 61, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.I. How Interest in the Product Affects Recall: Print Ads vs. Commercials. J. Adv. Res. 1964, 4, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- United States Patent and Trademark Office: What is a Trademark? Available online: https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/basics/what-trademark (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- USPTO. TMEP, Sections 1202.13–1202.15. July 2022. Available online: https://tmep.uspto.gov/RDMS/TMEP/current#/current/TMEP-1200d1e718.html (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- European Union Intellectual Property Office. Trademark Definition. Available online: https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/trade-mark-definition (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- USPTO. TMEP, Section 1202.12. July 2022. Available online: https://tmep.uspto.gov/RDMS/TMEP/Oct2012#/current/TMEP-1200d1e2820.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- USPTO. TMEP, Section 1207. July 2022. Available online: https://tmep.uspto.gov/RDMS/TMEP/Oct2012#/Oct2012/TMEP-1200d1e5036.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- USPTO. TMEP, Section 1209 and 1209.01. July 2022. Available online: https://tmep.uspto.gov/RDMS/TMEP/current#/current/TMEP-1200d1e6980.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Good Fruit Grower. Judge Orders Cancellation of Scarlet Trademark. 15 April 2006. Available online: https://www.goodfruit.com/judge-orders-cancellation-of-scarlet-trademark/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Yen, B. How Morphosyntactic Markedness Can Contribute to the Prevention of Trademark Genericide. Master’s Thesis, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0br9b9x3 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Avent, T. Name that Plant: The Misuse of Trademarks in Horticulture. In The Azalean; The Azalea Society of America: Herndon, VA, USA, 2013; p. 35. Available online: https://www.azaleas.org/articles/ (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Spencer, R.; Cross, R. Devising a Plant Labelling System that Satisfies Everyone! Acta Hortic. 2004, 634, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).