Abstract

Cinnamomum burmannii, renowned for its high essential oil content in leaves, is a pivotal species utilized for aromatic medicinal and industrial materials. This study focused on the functional identification of key regulatory enzyme 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) for terpenoid biosynthesis in the leaves of C. burmannii. A comprehensive approach, integrating terpenoid profiling assay and synthesis pathway construction, correlation analysis of terpenoid content and gene expression, and genome-wide analysis of DXS family across four developmental stages of leaves in three accessions of C. burmannii, led to the identification of CbDXS1 as a candidate regulatory gene for terpenoid biosynthesis. Overexpressing CbDXS1 in Arabidopsis enhanced plant growth, DXS enzyme activity, and chlorophyll content, and elevated transcriptional levels of terpenoid biosynthesis-related genes, leading to significant increases in terpenoid metabolites in transgenic leaves. Additionally, alterations in metabolite contents in the pathways of glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, oxidative pentose phosphate, the Calvin cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, amino acid metabolism, and phytohormone biosynthesis suggested a potential redirection of carbon flux from primary metabolism to terpenoid biosynthesis and changes in endogenous phytohormone contents, the diterpene biosynthesis pathway, and amino acid metabolism, which may collectively contribute to terpenoid accumulation and phenotypic improvement in transgenic Arabidopsis. Our findings elucidated the multifaceted roles of CbDXS1 in modulating carbon flux and phytohormone biosynthesis for terpenoid production and plant development, offering potential strategies for engineering essential oil accumulation in the leaves of C. burmannii.

1. Introduction

Currently, plant essential oils have attracted considerable attention owing to the exceptional safety, natural origin, and potential applications for antibacterial, anticancer, and antiviral activities, thereby finding extensive applications in areas such as food, cosmetics, medicine, and fragrances [1,2,3,4]. Numerous species of the Lauraceae family, such as Lindera glauca, Cinnamomum cassia, and Cinnamomum camphora, contain abundant essential oils that exhibit diverse biological effects encompassing anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antitumor effects [5,6,7], and they can serve as natural food preservatives, flavorings, antimicrobials, or antioxidants [8,9,10,11], thereby possessing exceptionally high application value.

Cinnamomum burmannii, an evergreen tree from the family Lauraceae, is widely distributed in southeastern China [12]. Given the rich content and the existence of specific terpenoid components (including D-borneol, eucalyptol, α-pinene, and α-terpineol), C. burmannii leaf essential oil (CBLEO) exhibits remarkable medicinal and antioxidant properties [8,13,14]. Consequently, it has emerged as a promising botanical species with significant practical implications and diverse applications in industries of pharmaceutical, food, and health products.

On the basis of the predominant chemical components present in the essential oils, the C. burmannii population is generally classified into four distinct chemotypes, i.e., the borneol type, eucalyptol type, cymene/eucalyptol type, and eucalyptol/borneol type [15]. D-borneol is a pivotal component of essential oil extracted from borneol-type C. burmannii. Pharmacological studies demonstrate that D-borneol has multifaceted therapeutic potential for conditions like asthma [16], cancer [17,18], and inflammation [19,20]. Furthermore, it acts as a penetration enhancer, facilitating the transmission of other drugs across the blood–brain barrier and skin mucosa, thereby enhancing their bioavailability [21]. These characteristics leads to a substantial market demand for D-borneol. However, the scarcity of tree species rich in D-borneol results in a severe shortage of D-borneol supply, leading to its high prices in markets. To enhance D-borneol production, researchers have primarily focused on screening high-yielding C. burmannii individuals and improving extraction techniques for D-borneol; yet, these efforts still fail to meet the demands. Molecular-oriented cultivation for high-D-borneol-producing C. burmannii varieties represents a crucial future approach to addressing the insufficient yield of D-borneol. However, it requires a comprehension of the D-borneol synthetic pathway and characterization of critical functional regulators for essential oil accumulation in C. burmannii leaves.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and its isomer isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), which act as C5-unit in terpenoid biosynthesis in plants, are mainly produced via two pathways, including the plastidic methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway and the cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) pathway [22]. Although the two pathways operate independently, they exhibit metabolite interchangeability [23,24,25,26]. The combination of DMAPP and IPP leads to the synthesis of geranyl diphosphate (GPP), geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), and farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), which can be used as essential precursors for terpenoid biosynthesis. Subsequently, various terpene synthases regulate the generation of corresponding terpenoids. Notably, the MVA pathway predominantly contributes to sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid production, while the MEP pathway primarily oversees the monoterpenoid and diterpenoid synthesis [27,28]. Given that D-borneol belongs to bicyclic monoterpenoid, its synthesis primarily occurs through the MEP pathway. Recently, the advancement of various high-throughput omics technologies has enabled the utilization of transcriptome and metabolome analyses to explore the regulatory mechanisms that governed terpenoid biosynthesis. The biosynthetic pathways and enzyme functions involved in monoterpenoid production have been investigated in various species, such as Artemisia annua [29], Arabidopsis thaliana [30], Cinnamomum osmophloeum [31], Cinnamomum tenuipilum [32], Lavandula angustifolia [33,34], and Mentha × piperita [35]. Yet, in C. burmannii, the specific biosynthetic pathway of D-borneol remains elusive. A comprehensive exploration for the critical genes associated with D-borneol biosynthesis and their functional characterization will facilitate molecular breeding and genetic improvement for C. burmannii.

In this study, the leaves at four developmental stages from three accessions of C. burmannii with significant differences in D-borneol content were utilized to identify the major terpenoids and their dynamic accumulation pattern. Subsequently, a correlation analysis between the content of major terpenoids and the expression levels of genes participating in terpenoid biosynthesis in developing leaves were conducted to identify a candidate key regulatory gene, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase 1 (CbDXS1), in the leaves of C. burmannii, which was shown to be closely associated with biosynthesis and the accumulation of several major terpenoids. Then, the CbDXS1 was cloned and ectopically overexpressed in Arabidopsis thaliana to conduct phenotypic and metabolomic analyses, aiming to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which CbDXS1 expression influences the biosynthesis of terpenoid metabolites. These findings offered a scientific foundation for the breeding of superior C. burmannii varieties by means of precise molecular improvement techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Three accessions of C. burmannii with varying D-borneol content in leaf essential oils were selected in our previous study. These accessions were propagated by cuttings and then maintained at the Plantation of Guangdong Academy of Forestry Sciences (115°50′1″ E, 24°28′28″ N), China. Among them, the accession exhibiting the highest D-borneol content in essential oil was designated as Cb-H, followed by Cb-M (middle D-borneol content) and Cb-L (low D-borneol content). The leaves at four key developmental stages [36], i.e., S1 (7 days post germination), S2 (14 days post germination), S3 (21 days post germination), and S4 (28 days post germination), as well as the roots and stems, were collected from the three accessions. After being washed with sterile water, the samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C until use for gene cloning, transcriptome sequencing, and qRT-PCR and GC-MS analysis.

The seeds of wild-type (WT) Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) and the vectors employed for gene cloning and ectopic expression were all preserved in our laboratory.

2.2. Extraction of C. burmannii Leaf Essential Oil and Analysis by GC-MS

To extract the C. burmannii leaf essential oil (CBLEO) for the identification of major terpenoid components, about 3.0 g leaves were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into powder by a mill. The obtained powder was transferred into 10 mL centrifuge tube and mixed with 4 mL of n-hexane to perform ultrasonication for 30 min using a frequency of 40.0 kHz and a power setting of 120 W. The mixture was subsequently incubated at 56 °C for 60 min, and centrifugated at 10,000 r/min for 5 min. After diluting the supernatant with n-hexane in a 1:10 ratio, the samples were moved to vials for subsequent gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis.

The constituents of essential oils were analyzed using GC-MS equipped with an SH-Rxi-5Sil mass spectrometry column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm). The temperature program began at 70 °C, which was increased gradually at a rate of 2 °C/min until reaching 160 °C, where it remained stable for 2 min. Then, the temperature was raised by 10 °C/min until it reached 220 °C and was maintained for 5 min. Helium supplemented with nitrogen was used as the carrier gas, flowing at a steady rate of 1.19 mL/min. The gas chromatography injection port was configured to operate with a split ratio of 1:20, with the temperature set at 230 °C and an injected sample volume of 1.0 μL. Mass spectrometry conditions included an ion source temperature set at 200 °C, with a scanning mass range spanning from 45 to 450 m/z.

2.3. RNA Sequencing and Functional Annotation

Total RNA was isolated from C. burmannii leaves at four developmental stages (S1–S4) across three accessions (Cb-H, Cb-M, and Cb-L) using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and the residual DNA was eliminated using RNase-free DNase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After quality assessment by NanoDrop (ThermoFisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), 1.0 μg RNA was employed for preparation of cDNA library [37]. Finally, the obtained cDNA library was introduced into FLO-MIN109 cells for full-length transcriptome sequencing using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) on PromethION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) at BioMarker Inc., in Beijing, China.

After removing the low-quality reads (length < 500 bp, Q score < 6) and ribosomal RNA sequences, the full-length sequences were refined to generate consensus sequences for elimination of redundant sequences by aligning with the reference genome of C. burmannii. The NR, GO, COG, KEGG, Pfam, and Swiss-Prot databases were employed to perform comprehensive gene annotation. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined using counts per million (CPM) with a threshold of ≥2-fold change and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, where the accuracy of DEG identification was assessed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

2.4. Identification of CbDXS Genes for In Silico Analyses

To detect all members of the CbDXS gene family in C. burmannii, candidate DXS sequences were screened from our previous genomic data of C. burmannii using HMMER and BLAST in TBtools (version 2.136). These candidates were further validated using SMART (https://smart.embl.de/smart/change_mode.cgi, accessed on 19 June 2024) and NCBI CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi, accessed on 19 June 2024) to confirm the typical DXS domain in their encoded proteins.

The ORFfinder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/, accessed on 19 June 2024) and CD-search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/, accessed on 19 June 2024) tools were employed to predict the open reading frame of CbDXS genes and conserved domain of encode proteins, respectively. Online websites of ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/, accessed on 19 June 2024), WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 19 June 2024), and MEME (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 19 June 2024) were used to analyze physicochemical properties, subcellular localizations, and conserved motifs, respectively. The analysis results of gene structure, conserved motif, collinearity relationship, and expression pattern were visualized using TBtools (version 2.136). Multiple sequence alignments of CbDXSs and homologous proteins from various species were conducted using the ClustalW2 program (version 2.1). The refinement of alignments was performed using Trimal (version 1.4.1). The phylogenetic relationship was established using the neighbor-joining method, with the application of 1000 bootstrap replicates, as conducted in software MEGA 7.0.

2.5. Molecular Docking of CbDXS1 Protein Complex and Substrates

According to prior research indicating that DXS utilizes Mn2+ and thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) cofactors to catalyze the condensation of pyruvate (PYR) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) for 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) biosynthesis [38], the molecular model of CbDXS1 protein complex with Mn2+ and TPP was constructed using AlphaFold3 (https://alphafoldserver.com/, accessed on 30 April 2025). The structures of PYR and GAP were optimized using obminimize software (version 3.1.1) with a forcefield of MMFF94. The CbDXS1 protein complex and substrates (PYR and GAP) were preprocessed using the Auto Dock Tools software (version 1.5.7), and the potential docking sites were selected to export the configuration files for molecular docking. Then, the software QuickVina 2 was used to continuously conduct local searches and repetitive iterations to find the best molecular docking conformation. The visualization and result analyses were carried out with PyMOL software (version 3.0.3).

2.6. Ectopic Overexpression of CbDXS1 in Arabidopsis thaliana

To explore the CbDXS1 function in regulating essential oil accumulation and terpenoid biosynthesis in the leaves of C. burmannii, the CbDXS1 coding sequence was amplified and subcloned into plant expression vector pGBO to construct pGBO/Pro35S::CbDXS1. The vector was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 via freeze–thaw method and transferred into wild-type Arabidopsis. Transgenic lines were screened on half-strength MS medium added to 25 mg/L kanamycin and verified by PCR amplification and sequencing analysis until T3 generation seeds were obtained. All the primers used for DNA amplification and vector construction are detailed in Table S1. Finally, homozygous transgenic lines of Pro35S::CbDXS1 were obtained by chi-square (χ2) test (Table S2). Three independent T4 transgenic lines with high transcript levels of CbDXS1 were used for further assays.

2.7. Analyses of Plant Phenotypic and Biochemical Index

To investigate the impact of CbDXS1 ectopic expression on phenotypes of transgenic Arabidopsis, the morphological characteristics (including plant height, root length, and rosette leaf number and area) were performed on both WT and T3 transgenic lines. The 10-day-old seedlings germinated on half-strength MS medium were used to detect root length, and then transferred to pots and grown in the same incubators. The plant height as well as the area and number of rosette leaves were measured at 48 d post transplantation. Subsequently, the leaf samples were collected to assay the enzymatic activity of DXS and chlorophyll content. The enzymatic activity of DXS in the same leaf samples was measured using an ELISA kit (Huding Biotechnology Inc., Shanghai, China) according to manufacturer’s protocol. About 0.1 g of leaves was immersed in 10 milliliters of 95% ethanol and left in darkness until tissues were bleached completely. Following the dilution of the resulting supernatant to a final volume of 15 mL, absorbance measurements were taken at wavelengths of 470 nm, 649 nm, and 665 nm to calculated the chlorophyll content.

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

The expression pattern of CbDXS in C. burmannii roots, stems, and leaves at four development stages (S1–S4) was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), which was carried out using fluorescent quantitative SYBR reagent (BMKGENE Biotechnology Inc., Beijing, China) using a CFX96 PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The genes encoding ribosomal protein S15 (RPS15) and Actin7 (ACT7) were used as inner references [12] to calculate the transcription abundance of CbDXS1 using the 2−ΔΔCt method, in which its transcription level in leaves at S1 stage was set to 1.00 for standardization. To analyze the expression profiling of terpenoid biosynthesis-related genes in Arabidopsis, the AtACT2 gene was used as the internal reference, and the expression level of target gene in leaves of WT was standardized to 1.00. The qRT-PCR assays were conducted with three biological replicates, and each sample was repeated with three technical repetitions.

2.9. Comprehensive Metabolomic Analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana Leaves

The metabolite components in leaves of the WT and transgenic Arabidopsis were detected by combined analyses of UPLC-MS and GC-MS. To prepare the samples for UPLC-MS, leaves from the WT and transgenic line Pro35S::CbDXS1 (L2, exhibiting the highest expression level of CbDXS1) were harvested after 4 weeks of normal growth. The samples were collected in centrifuge tubes containing 600 μL of methanol supplemented with 2-chloro-L-phenylalanine (4 mg/L) and mixed for 30 s. Subsequently, the samples underwent grinding by a tissue homogenizer set at a frequency of 55.0 kHz for 60 s, followed by sonication at 25 °C for 15 min. Afterward, the mixtures were centrifugated at 4 °C and 12,000 r/min for 10 min. The supernatants were filtered through 0.22 μm membrane filter and transferred to vials for UPLC-MS assay using Thermo Ultimate 3000 ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system (ThermoFisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC® HSS T3 column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The column was operated at 40 °C, with a flow rate set to 0.25 mL per minute and an injection volume of 2.0 μL. For the mobile phases, in positive ion mode, phase (C) comprised acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, while phase (D) consisted of water with 0.1% formic acid. In negative ion mode, phase (A) was acetonitrile, and phase (B) was water containing 5 mmol/L ammonium formate. The gradient elution program for positive ion modes was as follows: starting at 0–1 min with 2% (C), then increasing linearly to 50% (C) from 1 to 9 min, followed by a further increase to 98% (C) from 9 to 12 min, which was maintained up to 13.5 min and decreasing back to 2% (C) at 14 min. For negative ion mode, the gradient elution program began with 2% (A) from 0 to 1 min, increased linearly to 50% (A) from 1 to 9 min, and then to 98% (A) from 9 to 12 min [39]. The Thermo Q Exactive mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization source was used for data acquisition in negative ion (spray voltages −2.50 kV) and positive ion (spray voltages 3.50 kV) modes. The pressures of sheath gas and auxiliary gas were adjusted to 30 and 10 arb, respectively. The capillary temperature was 325 °C throughout the assay. A comprehensive scan ranging from m/z 100 to 1000 with a resolution of 70,000 was performed using first-level full scanning methodology. A higher-energy collisional dissociation technique was employed for secondary fragmentation, with a collision energy of 30% and a resolution of 17,500. Before signal collection, the first 10 ions were fragmented and unnecessary MS/MS information was eliminated using the dynamic exclusion method [40].

For GC-MS analysis, the leaves of Arabidopsis mentioned above were sampled in a centrifuge tube containing 1 mL of a solvent mixture (comprising acetonitrile:isopropanol:water = 3:3:2) to vortex for 30 s, and subsequently subjected to ultrasonication at 25 °C for 5 min. Following this, the sample underwent centrifugation at 12,000 r/min for 2 min. A total of 500 μL of resulting supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube to vacuum concentrate for 10 h, and re-dissolved in 80 μL of methoxyamine pyridine solution (20 mg/mL), followed by vortex for 30 s and incubation at 60 °C for 1 h. Next, 100 μL BSTFA-TMCS (in a ratio of 99:1) was added to the mixture, which was vortexed for 30 s and kept at 70 °C for 90 min. After centrifugation at 14,000 r/min for 3 min, 100 μL of supernatant was transferred into a vial for GC-MS analysis with a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm). The temperature program started at 50 °C for an initial hold of 30 s, then increased at a rate of 15 °C/min until reaching 320 °C and maintained for 9 min. Subsequently, the temperature was decreased at a rate of 10 °C/min to 220 °C and held for 5 min. The carrier gas was nitrogen and the constant flow rate was 1 mL/min. The injection port was operated in a split ratio of 1:10, and 1.0 μL of sample was injected at a temperature of 280 °C. Mass spectrometry conditions were set to full scan mode with a scanning rate of up to 10 spec/s.

The R XCMS v3.12.0 software package was utilized for peak recognition, filtering, and alignment [41]. Support vector regression correction was employed to eliminate systematic errors and filter out substances with RSD > 30% in the QC samples for subsequent data analysis. The identification of substances was performed using public databases, including KEGG [42], LipidMaps [43], HMDB [44], massbank [45], and mzcloud [46], with parameter settings of ppm < 30. Differential accumulated metabolites (DAMs) were identified based on the criteria of p value < 0.05 and VIP > 1.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The experiments involved in assays of leaf essential oil components and gene expression levels in different accessions of C. burmannii were conducted with three individual plants per accession, resulting in a total of nine plants across the three accessions. From each plant, three separate leaf samples were collected and analyzed independently. There were six biological replicates in the phenotypic analyses and three biological replicates in the metabolome and quantitative analysis of gene expression levels in the WT and transgenic Arabidopsis. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot software (version 12.0). Normality and variance homogeneity were assessed using Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Data that met both assumptions (normality, p > 0.05; variance homogeneity, p > 0.05) were subjected to ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple comparison test. Results are presented as mean ± SD. The significance level was set at 0.05 and the significant differences were denoted by different letters.

3. Results

3.1. Variability of Essential Oil Components in Developing Leaves Across Different Accessions of C. burmannii

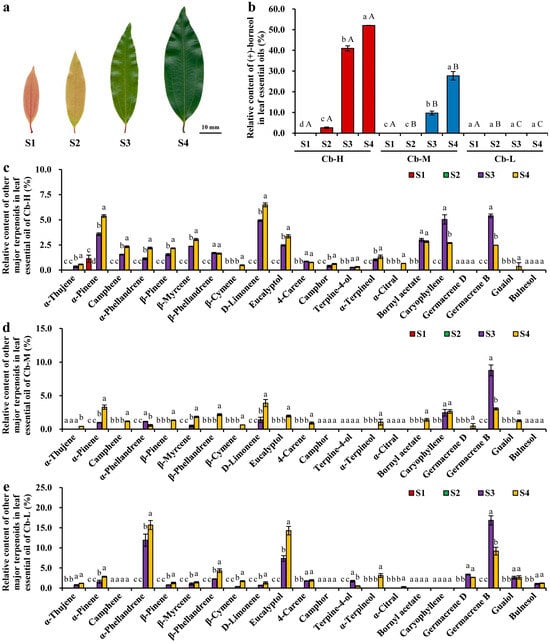

Given the notable variation in D-borneol content among leaf essential oils of different C. burmannii accessions [13], it was crucial to explore the accumulation patterns of essential oil components in developing leaves of C. burmannii, which could offer valuable insights into the regulatory mechanism governing leaf essential oil production. To address this, essential oils were extracted from leaves at four distinct developmental stages (from S1 to S4) across three accessions of C. burmannii characterized by high (Cb-H), medium (Cb-M), and low (Cb-L) D-borneol content for GC-MS analysis (Figure 1a). A two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of accession and developmental stage, as well as a significant interaction between these two factors, on the content of D-borneol in leaf essential oils. Specifically, the D-borneol content was significantly higher in Cb-H than in Cb-M, while trace amounts of D-borneol were detected in Cb-L (Figure 1b). Furthermore, accumulation patterns differed notably between accessions. In Cb-H, the accumulation of D-borneol initiated at the S2 stage, increasing rapidly from S2 to S3 until it reached the peak at S4. However, D-borneol biosynthesis commenced at S3 in Cb-M, showing a lower level and later accumulation compared to Cb-H.

Figure 1.

The relative content of terpenoid metabolites in essential oils extracted from four leaf developmental stages across three C. burmannii accessions. (a) Photographs of C. burmannii leaves at four development stages (S1–S4) according to our previous study. (b) Relative borneol contents in essential oils of three C. burmannii accessions across four developmental stages. The data are presented as mean ± SD. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among developmental stages within the same accession, while different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among accessions at the same developmental stage (p < 0.05). (c) Relative contents of major terpenoids in essential oils from developing leaves of Cb-H. (d) Relative contents of major terpenoids in essential oils from developing leaves of Cb-M. (e) Relative contents of major terpenoids in essential oils from developing leaves of Cb-L. The results are presented as mean ± SD, and the different letters indicate statistically significant differences at p < 0.05.

Besides D-borneol, significant variabilities in the content and accumulation pattern of other major terpenoids were observed in developing leaves among the tested accessions. A total of 21 major terpenoid metabolites were identified in CBLEOs, including 16 monoterpenoids and 5 sesquiterpenoids. Specifically, 19, 17, and 17 terpenoids were, respectively, detected in the leaf essential oils of Cb-H, Cb-M, and Cb-L. The predominant terpenoids in essential oils of Cb-H included α-pinene, D-limonene, eucalyptol, bornyl acetate, caryophyllene, and germacrene B. Except for α-pinene, the majority of terpenoids were predominantly accumulated in Cb-H leaves from the S3 to S4 stage (Figure 1c). In the leaf essential oils of Cb-M, the main terpenoids were α-pinene, D-limonene, caryophyllene, and germacrene B, with their contents progressively increasing during leaf maturation. However, the proportion of germacrene B was higher at the S3 stage than at the S4 stage, indicating a distinct accumulation pattern compared to other terpenoids (Figure 1d). Interestingly, the main components in essential oils of Cb-L leaves were α-phellandrene, eucalyptol, and germacrene B (Figure 1e), exhibiting significant differences in terpenoid composition compared to Cb-H and Cb-M. Notably, camphor, as a dehydrogenation product of D-borneol, was detected in leaf essential oils of Cb-H and Cb-M but was absent in Cb-L (Figure 1c,d), which was consistent with the D-borneol content among the test accessions. In summary, these results emphasized that the main period for terpenoid accumulation in C. burmannii leaves occurred during the S3 to S4 stages.

3.2. Identification of Critical Genes Potentially Involved in Terpenoid Accumulation of C. burmannii Leaves

The significant variation in terpenoid profiling during the leaf development of C. burmannii (Figure 1) indicated the presence of a complex regulatory mechanism underlying terpene biosynthesis. To elucidate this mechanism, full-length transcriptome sequencing was performed to identify potentially key genes associated with essential oil accumulation in developing leaves across the tested accessions of C. burmannii. Compared with S1, the number of DEGs increased from stage S2 to S4 in all three tested accessions as leaf development progressed (Figure S1). Notably, the number of DEG was higher in Cb-H than those in Cb-M and Cb-L at the same development stage, which may serve as the molecular foundation for the detected disparities in the content and composition of terpenoids in CBLEOs. In order to screen the potential genes associated with the terpene accumulation, the up-regulated DEGs were enriched in metabolic pathways using the KEGG database. The results indicated that the DEGs were remarkably enriched in the synthetic pathways of terpene backbone (ath00900) and monoterpene (ath00902) in developing leaves of Cb-H and Cb-M accessions. Specifically, the DEGs associated with terpene backbone biosynthesis were enriched in the groups of S1 vs. S2, S1 vs. S3, S1 vs. S4, and S2 vs. S4 in Cb-H, as well as the groups of S1 vs. S4, S2 vs. S3, and S2 vs. S4 in Cb-M. Meanwhile, the DEGs response for monoterpenoid biosynthesis were enriched in the groups of S1 vs. S4, S2 vs. S4, and S3 vs. S4 in Cb-H, and the groups of S1 vs. S3 and S1 vs. S4 in Cb-M (Figures S2 and S3), indicating a progressively up-regulated expression of genes involved in terpenoid accumulation with the leaf development of C. burmannii. Additionally, the DEGs among tested accessions of C. burmannii significantly enriched in monoterpenoid synthesis pathway in groups of Cb-H-S3 vs. Cb-M-S3 and Cb-H-S3 vs. Cb-L-S3 (Figure S4), implying that the elevated D-borneol content in essential oils of Cb-H maybe attributed to the up-regulated transcript levels of critical genes in the monoterpenoid biosynthesis pathway.

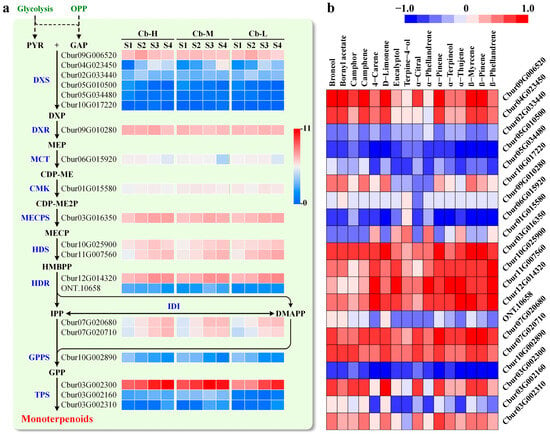

Given the fact of monoterpenoid as the predominant component in CBLEO (Figure 1), it was critical to identify the DEGs that were highly related to monoterpenoid biosynthesis from the transcriptome data to elucidate the regulatory mechanism that governed essential oil accumulation in leaves of C. burmannii. A total of 20 DEGs encoding for homologies of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS), 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR), 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidyltransferase (MCT), 4-(cytidine 5′-phospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erithritol kinase (CMK), 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MECPS), 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate synthase (HDS), 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (HDR), isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (IDI), geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), and terpenoid synthase (TPS) were identified specifically in response to monoterpenoid biosynthesis in C. burmannii leaves (Figure 2a). Of note were nine DEGs, which were highly transcribed and specifically up-regulated in C. burmannii leaves at stages S3 and S4, including DXS (Cbur09G006520), DXR (Cbur09G010280), MECPS (Cbur03G016350), HDS (Cbur10G025900 and Cbur11G007560), HDR (Cbur12G014320), IDI (Cbur07G020680 and Cbur07G020710), and TPS (Cbur03G002300), implying their potential contribution to monoterpenoid accumulation in developing leaves of C. burmannii.

Figure 2.

Identification of DEGs responding to monoterpene biosynthesis in C. burmannii leaves. (a) Construction of monoterpenoid biosynthesis pathway in C. burmannii leaves. The heat map shows the expression levels of DEGs implicated in MEP pathway for monoterpene biosynthesis in three C. burmannii accessions at four leaf developmental stages. The enzymes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis are highlighted in blue. The abbreviations for enzymes are as follows: DXS, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) synthase; DXR, DXP reductoisomerase; MCT, methylerythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; CMK, 4-diphosphocytidyl-methyerythritol kinase; MECPS, methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; HDS, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate (HD) synthase; HDR, HD reductase; IDI, isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase; GPPS, geranyl diphosphate synthase; TPS, terpenoid synthases. (b) Correlation analysis between the content of main monoterpenoids and transcript level of associated DEGs using the Pearson correlation coefficient method. The colors of red and blue are indicative of strong positive and negative correlation, respectively.

To further identify candidate genes potentially involved in monoterpenoid accumulation in C. burmannii leaves, we analyzed the association between the transcript levels of DEGs and the contents of major monoterpenoids using the Pearson correlation coefficient assay (Figure 2b). The expression level of DXS (Cbur09G006520) was significantly and positively correlated with the contents of eight monoterpenoids, including D-borneol (r = 0.845), bornyl acetate (0.756), camphor (0.732), camphene (0.813), α-pinene (0.880), β-pinene (0.848), β-myrcene (0.895), and D-limonene (0.895). Additionally, the expression levels of TPS (Cbur03G002300) and MECPS (Cbur03G016350) exhibited relatively high correlations with the D-borneol accumulation, with the coefficients of 0.710 and 0.673, respectively. Considering the strongest correlation between DXS expression and monoterpenoid accumulation, we propose that high transcript levels of DXS (Cbur09G006520) likely play a prominent role in essential oil accumulation in C. burmannii leaves.

3.3. CbDXS1 as the Predominant DXS Family Member Mediating Terpenoid Accumulation of C. burmannii Leaves

To explore the potential role of DXS in regulating the terpenoid biosynthesis of C. burmannii leaves, bioinformatics analyses were conducted on the above-identified six DXS gene family members (designated from CbDXS1 to CbDXS6) (Table 1). The results revealed that CbDXS proteins exhibited amino acid lengths ranging from 709 to 775 residues, with corresponding molecular masses spanning from 76.30 to 83.94 kDa. The theoretical isoelectric points varied from 6.52 to 7.67, among which the CbDXS1/3/6 were classified as acidic proteins, whereas the remaining proteins were basic. The instability indices ranged from 39.21 to 43.07, with CbDXS2/6 showing relatively higher stability. All CbDXS proteins exhibited hydrophilic characteristics and were localized in chloroplasts.

Table 1.

Analysis of physicochemical properties for CbDXS proteins.

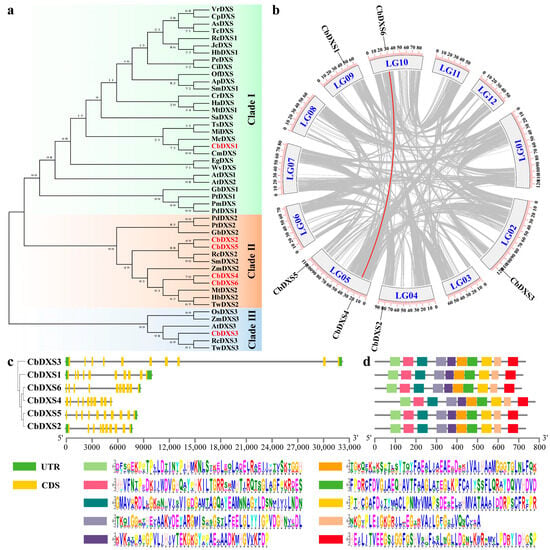

The phylogenetic tree revealed that the CbDXS proteins could be divided into three clades with other DXS homologues from higher plants. Among them, the CbDXS1 was assigned to clade I and was closely related to CmDXS from Cinnamomum micranthum. CbDXS2 and CbDXS4, respectively, clustered with CbDXS5 and CbDXS6, which were classified into clade II, showing that it is clearly distinguished from the CbDXS3 protein, which belonged to clade III (Figure 3a). Furthermore, the collinearity analysis results indicated that CbDXS genes were distributed on five chromosomes, but only CbDXS4 and CbDXS6 had a collinearity relationship, implying their similar biological functions (Figure 3b). Gene structural analysis indicated significant variation in gene length (5320~32,216 bp) and the number of exons and introns among CbDXS family members, with CbDXS3 having the fewest introns (10) and the remaining five members possessing 11 introns each (Figure 3c). Motif analysis demonstrated that CbDXS proteins shared 10 motifs, typically spanning from 35 to 50 amino acid residues (Figure 3d), revealing relatively conserved motifs of CbDXS proteins throughout evolution. Furthermore, a conserved DXS domain (PLN02582, located at residues of 46~716), a TPP binding domain (cd02007, residues of 109~364), and a transketolase pyrimidine binding domain (smart00861, residues of 440~559) were marked in the CbDXS1 with the CD-search website (Figure S5). All these results indicated that CbDXS1 exhibited typical characteristics of the orthologs of DXS1, which might play a role associated with terpenoid accumulation in the leaves of C. burmannii.

Figure 3.

In silico analyses of CbDXSs in leaves of C. burmannii. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of CbDXSs and homologous proteins from various species using neighbor-joining method. Accession numbers for DXS proteins are listed: C. burmannii (CbDXS1, CbDXS2, CbDXS3, CbDXS4, CbDXS5, CbDXS6); Andrographis paniculata (ApDXS, XP_051127991.1); Aquilaria sinensis (AsDXS1, AFU75321.1); Arabidopsis thaliana (AtDXS1, AT4G15560.1; AtDXS2, AT3G21500.3; AtDXS3, AT5G11380.1); Carica papaya (CpDXS, XP_021904955.1); Carya illinoinensis (CiDXS, XP_042939057.1); Catharanthus roseus (CrDXS, AGL40532.1); Cinnamomum micranthum (CmDXS, RWR93643.1); Elaeis guineensis (EgDXS, NP_001290502.1); Ginkgo biloba (GbDXS1, AAR95699.1; GbDXS2, AAS89341.1); Helianthus annuus (HaDXS, KAJ0593846.1); Hevea brasiliensis (HbDXS1, AAS94123.1; HbDXS2, ABF18929.1); Jatropha curcas (JcDXS, NP_001295666.1); Macadamia integrifolia (MiDXS, XP_042491426.1); Magnolia champaca (McDXS, ART66978.1); Medicago truncatula (MtDXS1, CAD22530.1; MtDXS2, CAN89181.1); Oryza sativa (OsDXS3, EEE65067.1); Osmanthus fragrans (OfDXS1, AOT86855.1); Pinus densiflora (PdDXS1, ACC54557.1; PdDXS2, ACC54554.1); Pinus massoniana (PmDXS, UIB01902.1); Pinus taeda (PtDXS1, ACJ67021.1; PtDXS2, ACJ67020.1); Populus euphratica (PeDXS, XP_011014224.1); Ricinus communis (RcDXS1, XP_002514364.1; RcDXS2, XP_002533688.1; RcDXS3, XP_002514364.1); Salvia miltiorrhiza (SmDXS1, ACF21004.1; SmDXS2, ACQ66107.1); Santalum album (SaDXS, QBZ39613.1); Telopea speciosissima (TsDXS, XP_043721725.1); Theobroma cacao (TcDXS, EOY06359.1); Tripterygium wilfordii (TwDXS1, KM879185; TwDXS2, KM879186; TwDXS3, KM879187); Vitis riparia (VrDXS, XP_034686383.1); Wurfbainia villosa (WvDXS, ACR02668.1); Zea mays (ZmDXS1, NP_001157805; ZmDXS2, ABP88135; ZmDXS3, HQ113384.1). (b) Collinearity analysis of CbDXS genes. The grey lines represent the collinearity regions; the red line represents the collinearity genes. (c) Structure of CbDXS genes. (d) Conserved motifs of CbDXS1 proteins. The colored boxes represent distinct conserved motifs.

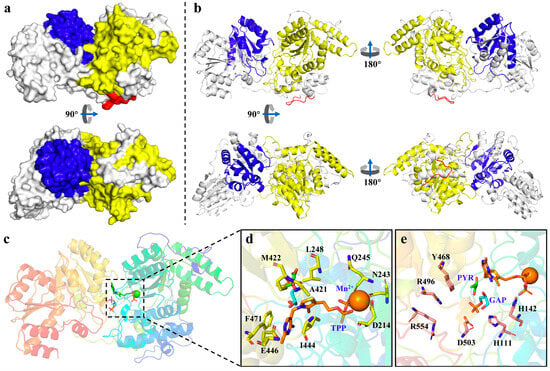

3.4. CbDXS1 Exhibits Conserved 3D Protein Structure Essential for Condensation of DXP

To predict the potential function of CbDXS1 in catalyzing PYR and GAP for the formation of DXP, an intermolecular complex containing CbDXS1 protein and two ligands (Mn2+ and TPP) was generated to perform molecular docking with PYR and GAP (Figure 4). Herein, the TPP binding domain (residues of 109~364, shown in yellow) and the transketolase pyrimidine binding domain (residues of 440~559, shown in blue) together composed the active site of the CbDXS1 protein (Figure 4a,b). Additionally, a cleavage site (EYHSQRPPTP, highlighted in red) for the chloroplast transit peptide was found at the N-terminus of CbDXS1 (Figure 4a,b), which aligns with the prediction of its chloroplast localization (Table 1). The molecular docking analysis revealed a credible TPP binding site and active site of the CbDXS1 protein (Figure 4c). The TPP binding pocket in CbDXS1 is characterized by conserved structural interactions (Figure 4d). Two conserved residues, F471 and E446, which are known to interact with TPP in DXS enzymes, were found to engage with the pyrimidine ring of TPP through spatial proximity. The diphosphate group of TPP coordinated with Mn2+ via interactions with D214, N243, and Q245. Furthermore, the cofactor could establish multiple hydrophobic contacts with conserved residues L248, A421, M422, and I444. Finally, within the active site of CbDXS1, a cluster of critical residues involved in catalytic activity (H142 and D503) and GAP binding (H111, Y468, R496, and R554) was identified as these residues were positioned in proximity to the substrates PYR and GAP (Figure 4e), suggesting a functionally active conformation for DXS biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

The three-dimensional model and the TPP binding site and active site of CbDXS1. (a) The molecular model of CbDXS1 protein constructed using AlphaFold3 is represented in surface style. (b) The structure of CbDXS1 is represented in ribbon style from different angles. The TPP binding domain (residues of 109~364) is shown in yellow; the transketolase pyrimidine binding domain (residues of 440~559) is shown in blue; and the chloroplast transit peptide cleavage site (residues of 62~71) is shown in red. (c) The TPP binding site and active site of CbDXS1 are represented in ribbon style. (d) The TPP binding site. TPP and Mn2+ are depicted as orange sticks and balls, respectively. The residues that make interactions with TPP and Mn2+ are highlighted as yellow sticks. (e) Active site of CbDXS1. PYR and GAP are shown as green and cyan sticks, respectively. The residues that were recognized to be crucial for the catalytic activity of DXS are marked as pink sticks.

3.5. CbDXS1 Is Specifically Expressed in Developing Leaves of C. burmannii

To elucidate the contribution of CbDXS1 to the essential oil accumulation of C. burmannii leaves, it was imperative to confirm whether the expression of CbDXS1 was specifically associated with leaf development in C. burmannii. Therefore, the full-length cDNA of CbDXS1 (Figure 5a) was cloned to conduct the spatial- and temporal-specific expression analysis of CbDXS1 in different organs (roots, stems, and leaves) of C. burmannii via qRT-PCR (Figure 5b). During leaf development, the relative expression of CbDXS1 showed a significant increase, with notably higher levels in Cb-H compared to Cb-M and Cb-L. This finding was consistent with transcriptome sequencing results, suggesting a strong correlation between CbDXS1 expression and terpenoid accumulation in C. burmannii leaves. Additionally, CbDXS1 exhibited a distinct expression pattern across various tissues, with notably higher transcript levels in leaves compared to stems and roots (Figure 5c). These findings indicated that CbDXS1 was predominantly expressed in leaves of C. burmannii and exhibited temporal expression characteristics in response to leaf development.

Figure 5.

Cloning and expression profile analyses of CbDXS1 in C. burmannii. (a) Cloning of CbDXS1 gene from C. burmannii leaves by PCR. M signifies 2000 DNA marker and 1 signifies CbDXS1 gene fragment. (b) Expression levels of CbDXS1 in developing leaves (S1–S4 stages) of different borneol accessions. The results are presented as mean ± SD, and the capital and lowercase letters indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05) as detected by qRT-PCR and ONT sequencing, respectively. (c) Expression levels of CbDXS1 in roots, stems, and leaves (S4 stage) of Cb-H. The results are presented as mean ± SD, and the different letters indicate significant differences between groups at p < 0.05.

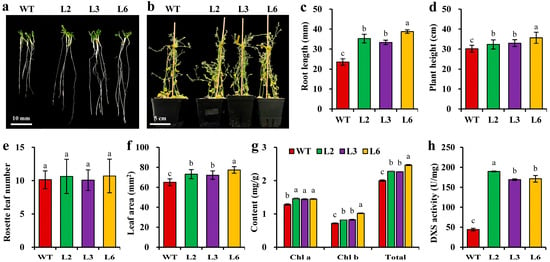

3.6. Overexpressing CbDXS1 Enhances Plant Growth with Increased DXS Activity and Chlorophyll Level of Transgenic Lines

To explore the phenotypic effects of CbDXS1 ectopic overexpression in Arabidopsis, three homozygous lines (L2, L3, and L6) exhibiting the highest expression levels of CbDXS1 were selected from eight transgenic Arabidopsis lines (Figure S6 and Table S2) to assess the changes in morphological features (including root length, plant height, rosette leaf number, and leaf area) on the seedlings of T4-generation transgenic lines and WT control (Figure 6). After 10 days of germination, the root length of seedlings from Pro35S::CbDXS1 lines (ranging from 33.38 ± 1.13 mm to 38.76 ± 0.85 mm) was significantly longer than that from the WT (23.52 ± 1.63 mm) (Figure 6a,c), as was the case for both plant height and leaf area (Figure 6b,d,f). However, rosette leaf number was comparable between the WT and transgenic lines (Figure 6e). The results revealed that ectopic expression of CbDXS1 facilitated vegetative growth and plant development of transgenic lines, but had no influence on the initiation of leaves.

Figure 6.

Effect of CbDXS1 overexpression on phenotypes of transgenic Arabidopsis. (a) The growth status of root systems in WT and CbDXS1 transgenic seedlings at 10 days post germination. (b) The plant status of WT and CbDXS1 transgenic seedlings at 48 days post transplantation. (c) Root length of WT and transgenic Arabidopsis at 10 d after germination. (d) Plant height of Arabidopsis lines at 48 d after transplantation. (e) Rosette leaf number of Arabidopsis lines. (f) Leaf area of Arabidopsis lines. (g) Chlorophyll (Chl) content in mature leaves of Arabidopsis lines. (h) DXS enzyme activity in leaves of WT and transgenic Arabidopsis. The WT was used as the control, and all the assays were conducted on six biological replicates. The results are presented as mean ± SD, and the different letters above columns indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Chlorophylls, the primary pigments influencing the photosynthetic capacity of leaves, are also terpenoid derivatives in higher plants. Herein, the levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were significantly elevated in CbDXS1 transgenic leaves (Figure 6g), and the DXS enzyme activity in transgenic plants was observed to increase from 3.82- to 4.29-fold compared to that in the WT (Figure 6h). These findings demonstrated that ectopic expression of CbDXS1 elevated the DXS activity and promoted the chlorophyll biosynthesis in transgenic leaves.

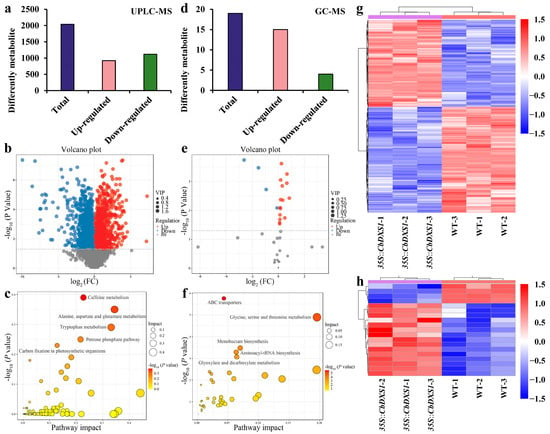

3.7. CbDXS1 Expression Causes Notable Variation in Content of Terpenoid-Related Metabolites in Transgenic Leaves

To comprehensively explore the impact of the ectopic overexpression of CbDXS1 on terpenoid accumulation in transgenic leaves, we analyzed metabolite profiling in leaves of both the WT and CbDXS1 transgenic lines using a combined approach of UPLC-MS and GC-MS. As a result, 7889 and 42 metabolites were identified, respectively. Of these, 2039 differential accumulated metabolites (DAMs) were marked in transgenic leaves with 921 up-regulated and 1118 down-regulated metabolites by UPLC-MS compared with the WT (Figure 7a–c,g). Additionally, GC-MS analysis revealed 19 DAMs, including 15 up-regulated and 4 down-regulated compounds in the leaves of transgenic lines (Figure 7d–f,h).

Figure 7.

Identification of DAMs in the leaves of WT and CbDXS1 transgenic lines by an integrated analysis of UPLC-MS and GC-MS. (a) The number of DAMs in groups of Pro35S::CbDXS1 vs. WT based on UPLC-MS. (b) Volcano plot of DAMs identified by UPLC-MS. Red and blue dots represent the up-regulation and down-regulation of DAMs, respectively. (c) Bubble diagram by UPLC-MS. (d) The number of DAMs in groups of Pro35S::CbDXS1 vs. WT based on GC-MS. (e) Volcano plot of DAMs identified by GC-MS. Red and blue dots indicate up- and down-regulated DAMs, respectively. (f) Bubble diagram by GC-MS. (g) Cluster analysis of DAMs based on UPLC-MS. (h) Cluster analysis of DAMs based on GC-MS.

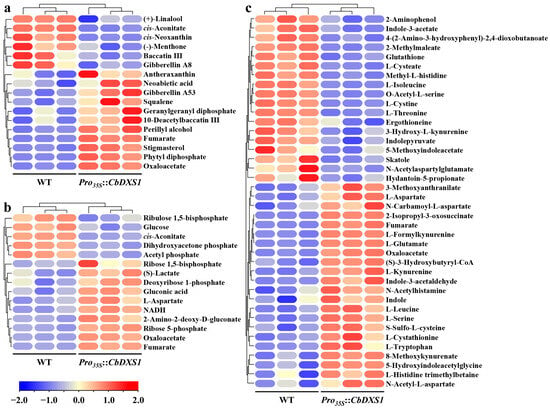

There were 78 metabolites enriched to eight pathways associated with terpenoid accumulation by KEGG enrichment analysis (Table S3), in which 17 metabolites were DAMs (Figure 8a). Notably, the contents of phytyl diphosphate (phytyl-PP) and its precursor geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) in leaves of CbDXS1 transgenic lines reached between 9.27- and 1.31-fold compared to those in WT, respectively. In the monoterpenoid and diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway, the accumulations of three low-content terpenoids, i.e., (+)-linalool, (−)-menthone, and baccatin III, were found to be suppressed in transgenic leaves, whereas the contents of three high-level terpenoids of perillyl alcohol, neoabietic acid, and 10-deacetylbaccatin III increased obviously (Figure 8a and Table S3), showing the destined metabolic products accumulated via the MEP pathway in transgenic leaves. In addition, eight GAs (GA3/4/7/8/9/24/36/53) were detected in the diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway (Table S3). Of note was the content of GA53, which increased significantly, while that of GA8 decreased. Furthermore, along with an increase in squalene, the content of its downstream metabolite stigmasterol rose to 7.20-fold in transgenic leaves. The biosynthesis of carotenoids and apocarotenoids is another important metabolic pathway of terpenoids. Herein, an inverse relationship between the levels of cis-neoxanthin and antheraxanthin was observed, which impedes ABA accumulation in leaves of transgenic lines. Collectively, these results suggested that the ectopic expression of CbDXS1 widely influenced the accumulation of terpenoid metabolites in transgenic leaves.

Figure 8.

Analyses of differential accumulated metabolites in leaves of WT and CbDXS1 transgenic lines. (a) The DAMs enriched in terpenoid biosynthesis pathways in leaves of Arabidopsis. (b) The DAMs involved in pathways related to carbon flux and energy generation in leaves of Arabidopsis. (c) The DAMs related to amino acid metabolic pathways in leaves of Arabidopsis. The color of frames indicated the content of metabolites, with red indicating a higher concentration and blue indicating a lower concentration.

3.8. CbDXS1 Expression Effects Carbon Flux and Energy Source for Terpenoid Biosynthesis in Transgenic Leaves

The enrichment analysis for terpenoid biosynthesis pathways revealed significant alterations in the contents of three key tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, i.e., cis-aconitate, fumarate, and oxaloacetate (Figure 8b and Table S3), implying that ectopic expression of CbDXS1 may also influence intracellular carbon flux and energy source. Expectedly, the KEGG enrichment assay revealed that the DAMs were enriched in the oxidative pentose phosphate (OPP) pathway, the TCA cycle, PYR metabolism, the Calvin cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and amino acid metabolism (Figure S7), revealing that the overexpression of CbDXS1 led to multiple alterations in carbon flux and energy source in transgenic leaves.

PYR and GAP are known as the substrates of DXS for DXP biosynthesis in the MEP pathway, which promoted the exploration of metabolic pathways (glycolysis, TCA cycle, OPP pathway, Calvin cycle, or PYR metabolism) potentially involved in the formations of PYR and GAP. Among the 39 metabolites detected by metabolomics in this work (Table S4), the levels of glucose, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), cis-aconitate, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP), and acetyl phosphate were reduced significantly, whereas oxaloacetate, fumarate, lactate, gluconic acid, ribose 5-phosphate (R5P), ribose 1,5-bisphosphate (R1,5P), deoxyribose 1-phosphate, 2-amino-2-deoxy-D-gluconate, and L-aspartate showed obvious accumulations in transgenic leaves (Figure 8b). Specifically, the reduction levels of DHAP in the glycolysis pathway could be attribute to the increased conversion from DHAP to GAP, which was a result of heightened GAP consumption due to enhanced DXS enzyme activity (Figure 6h). Meanwhile, the decrease in glucose content indicated an enhanced glycolytic flux as a compensatory mechanism for the depletion of PYR and GAP. Furthermore, the decrease in cis-aconitate and the accumulation of fumarate and oxaloacetate implied the inhibition of the TCA cycle due to the consumption of PYR in the MEP pathway impacting the available acetyl-CoA pool and consequently impeding the condensation of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate for citrate production. The elevated contents of R5P and R1,5P in the oxidative phase of the OPP pathway indicated an obstruction of the non-oxidation stage; simultaneously, the decrease in RuBP level could be attributed to the inhibition of the Calvin cycle due to GAP depletion. In summary, although metabolite pools do not directly reflect flux, these results demonstrated that ectopic expression of CbDXS1 led to significant alterations in the contents of key metabolites in associated biochemical pathways. The observed changes are likely consistent with a model in which carbon flux was redirected toward the glycolysis pathway and the MEP pathway, potentially at the expense of the TCA cycle, the OPP pathway, and the Calvin cycle. Also of note was the fact that the NADH contents in transgenic lines were five times those in the WT, suggesting that the expression of CbDXS1 promoted the production of NADH and eventually contributed to providing adequate energy for the biosynthesis of metabolites in leaves of transgenic lines.

Given the intricate interplay between carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism, another concern is the significant enrichment of DAMs in amino acid metabolic pathways (Figure S7). Here, 108 metabolites were enriched in six amino acid metabolic pathways (Table S5). Among these, the cumulative levels of 21 metabolites significantly increased, while those of 18 metabolites decreased in CbDXS1 transgenic plants (Figure 8c). Of note was the L-tryptophan content, increasing by 2.88-fold in transgenic lines compared to WT, which promoted the production of indole, indole-3-acetaldehyde, and 5-hydroxyindoleacetylglycine but suppressed the accumulation of indole-3-acetate (IAA), indolepyruvate, and 5-methoxyindoleacetate in the tryptophan metabolism pathway, suggesting a significant alteration in the synthesis and metabolism of IAA. On the other hand, the altered levels of L-formylkynurenine, L-kynurenine, 4-(2-amino-3-hydroxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxobutanoate, and 3-hydroxy-L-kynurenine ultimately led to the elevation of 8-methoxykynurenate. In the alanine/aspartate/glutamate metabolism pathway, the levels of L-glutamate and L-aspartate and their derivatives (N-acetyl-L-aspartate and N-carbamoyl-L-aspartate) increased, whereas N-acetylaspartylglutamate content decreased markedly. Additionally, significant alterations were observed in derivatives of L-histidine. Specifically, the contents of methyl-L-histidine, ergothioneine, and hydantoin-5-propionate were down-regulated, whereas those of N-acetylhistamine and L-histidine trimethylbetaine were up-regulated. Furthermore, the levels of L-serine and L-cystathionine increased by 1.58- and 1.83-fold in transgenic leaves compared to the WT. Conversely, levels of L-cystine, L-cysteate, and glutathione in transgenic lines decreased by 0.40-, 0.63-, and 0.51-fold, respectively. These findings suggested that overexpression of CbDXS1 also modulated amino acid metabolic pathways, thereby exerting multiple effects on the metabolome of transgenic Arabidopsis leaves.

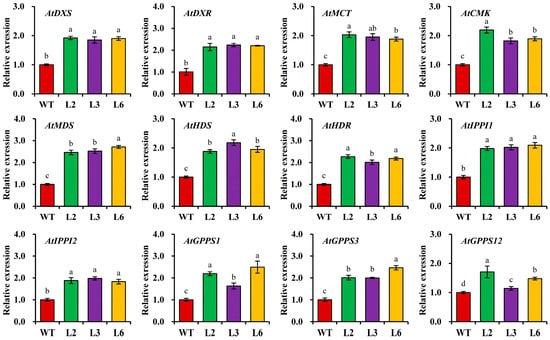

3.9. Ectopic Expression of CbDXS1 Enhances Transcription of Terpenoid Biosynthesis-Related Genes in Transgenic Leaves

To gain a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underlie the contribution of CbDXS1 expression to terpenoid biosynthesis in transgenic leaves, we investigated how CbDXS1 abundance influenced the transcript profiling of 12 endogenous genes related to the MEP pathway in transgenic leaves of Arabidopsis using qRT-PCR. Our findings revealed a significant up-regulation in transcript levels of these genes in transgenic leaves compared to WT (Figure 9). This result indicated that overexpression of CbDXS1, which regulated the initial reaction of the MEP pathway, promoted the transcriptions of downstream genes, thereby enhancing terpenoid biosynthesis and contributing to essential oil accumulation in the leaves of transgenic lines.

Figure 9.

Expression analysis of terpenoid biosynthesis-related genes in the leaves of WT and transgenic Arabidopsis. The detected genes were AtDXS (At4g15560), AtDXR (At5g62790), AtMCT (At2g02500), AtCMK (At2g26930), AtMDS (At1g633970), AtHDS (At5g60600), AtHDR (At4g34350), AtIPPI1/2 (At3g02780 and At5g16440), and AtGPPS1/3/12 (At1g49530, At2g18640, and At4g38460). The relative expression levels were counted using the 2−ΔΔCt method, and the expression level of each target gene from the leaves of WT was set to 1.00 for standardization. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

4.1. Construction of Terpenoid Biosynthetic Pathway and Identification of Key Regulator CbDXS1 for CBLEO Accumulation

In higher plants, terpenoids display a diverse array of types, structures, and functions, which are essential for regulating growth and development processes, and for responding to both abiotic and biotic stresses [25,47]. Previous research shows that the precursors DMAPP and IPP for terpenoid biosynthesis are mainly produced via the MEP and MVA pathways [23,24,25,26,48]. Between them, the backbones of monoterpenoids are biosynthesized from GPP mainly through the MEP pathway and subsequently undergo enzymatic modifications to generate diverse monoterpenoids with distinct structures and functions [23]. In this study, D-borneol, along with other monoterpenoid compounds, constituted the main components of CBLEOs (Figure 1b,c). This suggested that monoterpenoid biosynthesis, which was closely associated with the MEP pathway, played a crucial role in determining the content and quality of the CBLEOs. Consequently, the comprehensive analysis of full-length transcriptome sequencing, gene functional annotation, and KEGG pathway enrichment was performed to construct the MEP pathway in leaves of C. burmannii (Figure 2a). Our findings revealed that the DEGs were notably enriched in pathways of terpenoid backbone and monoterpene biosynthesis in developing leaves of different C. burmannii accessions (Figures S2 and S3), suggesting that the dynamic expression patterns of these DEGs likely contributed to both continuous accumulation of terpenoids during leaf development and terpenoid diversity across different CBLEOs. Based on gene functional annotation, 20 DEGs responding to monoterpenoid biosynthesis were identified (Figure 2), providing a foundation for the effective identification of vital regulatory genes for CBLEO accumulation.

The correlation analysis between transcription abundance of DEGs and terpenoid contents in developing leaves across various C. burmannii accessions provided valuable insights into identifying key regulators of terpenoid biosynthesis and essential oil accumulation, thereby facilitating further functional validation studies. Herein, the transcript levels of three DEGs (DXS, TPS, and MECPS) exhibited high positive correlations with D-borneol content (Figure 2b), suggesting their potential roles in regulating D-borneol accumulation, which aligned with the results from previous studies [13,49,50]. Notably, the DXS gene had been identified as encoding the vital enzyme that limits the reaction rate in the MEP pathway, thereby regulating metabolic flux into the MEP pathway in higher plants [51]. For instance, the up-regulation of DXS expression significantly enhanced isoprenoid levels in Arabidopsis [52], and overexpressing DXS resulted in increased accumulation of essential oils in Withania somnifera and rose-scented geranium [53]. Herein, the expression levels of CbDXS1 demonstrated strong correlations with the contents of major terpenoids in CBLEOs (Figure 2b), suggesting that CbDXS1 not only regulated the biosynthesis of D-borneol, but also exerted a comprehensive influence on accumulation of important terpenoids in CBLEOs. Additionally, CbDXS1 was specifically transcribed in C. burmannii leaves (Figure 5c), exhibited the highest expression levels compared to the other five DXS family members in developing leaves across tested accessions (Figure 5b), and possessed a functionally active conformation for DXS biosynthesis (Figure 4). All of these findings implied the critical function of CbDXS1 in modulating the synthesis of main terpenoids in developing leaves of C. burmannii, particularly the high essential oil accumulation in Cb-H leaves, as evidenced by similar observations in Lycopersicon esculentum, Andrographis paniculata, and Salvia sclarea [38,52,54,55].

Moreover, it is worth noting that the transcription abundance of CbDXS2 and its correlation coefficient with terpenoid contents was lower than that of CbDXS1 (Figure 2) but was obviously higher than other members in the CbDXS gene family, implying that CbDXS2 could have a relatively minor function in modulating the biosynthesis of terpenoids and their derivatives. This distinction likely arises from the functional diversification of members within the DXS gene family during species evolution [56,57], highlighting the need for further experimental investigations to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

4.2. Functions of CbDXS1 in Regulating Terpenoid Accumulation in Transgenic Leaves of Arabidopsis

Available evidence supports the functional diversification of plant DXS into three specialized groups: synthesizing particular isoprenoids as secondary metabolites in non-photosynthetic plastids, generating essential isoprenoids like chlorophyll in chloroplasts, and producing essential isoprenoids that are needed in small amounts, such as phytohormones [56,57]. Indeed, homologous or heterologous expression of DXS exhibited diverse effects on the accumulation of secondary metabolites in various species. For example, ectopic-expressing AtDXS and AcDXS1 significantly enhanced monoterpenoid biosynthesis in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana and Lavandula latifolia, respectively [58,59], and homologous transformation with SmDXS5 enhanced the tanshinone accumulation in hairy roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza [60]. In this work, the overexpression of CbDXS1 increased the transcript levels of vital genes relevant for terpenoid biosynthesis associated with the MEP pathway (Figure 9) and led to a significant accumulation of GGPP and phytyl-PP (Figure 8a), which could provide substrates for the monoterpenoid and diterpenoid biosynthesis, leading to a substantial rise in the contents of perillyl alcohol, neoabietic acid, and 10-deacetylbaccatin III in leaves of transgenic Arabidopsis (Figure 8a and Table S3). These results revealed a conserved function of CbDXS1 in modulating the biosynthesis of monoterpenoids and diterpenoids via enhancement of the MEP pathway, as is the case with DXS homologous genes in A. thaliana, Actinidia chinensis, Paeonia suffruticosa, and Solanum tuberosum [52,59,61,62]. Also noteworthy was the increased levels of squalene and stigmasterol in transgenic leaves (Table S3), which indicated that overexpression of CbDXS1 could also promote the biosynthesis of triterpenoids and their derivatives in the downstream of the MVA pathway. This phenomenon could be associated with the IPP transport from the plastidic MEP to the cytosolic MVA pathway for FPP generation, which has been evidenced by previous research in L. glauca, Solanum habrochaites, Stevia rebaudiana, and Vitis vinifera [22,63,64,65]. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that overexpression of certain DXS homologs results in enhanced contents of plastidic isoprenoids, including chlorophylls and carotenoids [52,58,66,67,68]. Herein, the observed increases in levels of chlorophylls and carotenoids in leaves of CbDXS1 transgenic lines (Figure 6g and Figure 8a) were consistent with these reports, revealing that CbDXS1 also played a role in photosynthetic pigment biosynthesis. Taken together, these findings highlighted the dual function of CbDXS1 in biosynthesis of both secondary metabolites and photosynthetic pigments, which is distinct from the DXS homologs in other plant species.

4.3. Overexpression of CbDXS1 Modulates Plant Growth by Synergistic Effects of Metabolic and Regulatory Networks

In addition to enhancing terpenoid accumulation, overexpression of CbDXS1 concurrently induced significant alterations in intracellular metabolite levels associated with biochemical and energetic metabolism. These changes generally correlated with an enhanced glycolysis pathway but suppressed TCA cycle, OPP pathway, and Calvin cycle (Figure 8b). Consequently, it was hypothesized that the enhancement of glycolysis led to increased NADH generation; meanwhile, the suppression of the TCA cycle impaired mitochondrial NADH transport and consumption, resulting in the high levels of NADH in transgenic leaves (Figure 8b). Together with the significant up-regulation in the transcription of endogenous genes in the MEP pathway (Figure 9), these observations suggested that ectopic expression of CbDXS1 coordinated the transcription of downstream genes to jointly enhance the MEP pathway and may have redirected carbon allocation from primary biochemical pathways (including glycolysis, TCA cycle, OPP pathway, and Calvin cycle) toward the MEP pathway for eventual terpene biosynthesis in transgenic lines. However, it should be noted that these inferences are based on steady-state metabolite levels and gene expression data; direct evidence from flux analysis (e.g., enzyme activity assays or isotopic labeling) would be required confirmation of the proposed shifts in metabolic flux. Furthermore, research related to the influence of DXS expression on the redirection of carbon flux is extremely limited [60]; thus, the molecular regulatory mechanism warrants further investigation.

Also of note were the alterations in phytohormone levels in CbDXS1-overexpressing lines. Within the tryptophan metabolic pathway, the observed increase in indole level, coupled with decreases in indolepyruvate and IAA contents (Figure 8c and Table S5), indicated that IAA biosynthesis was inhibited in transgenic leaves. Additionally, the modest reduction in major bioactive GA levels (GA3, GA4, and GA7), alongside the significant rise in their inactive precursor (GA53) (Figure 8a and Table S3), suggested suppressed GA activity in transgenic lines [69,70]. On the contrary, ABA levels showed a slight stimulation following CbDXS1 overexpression (Table S3). Collectively, these changes in phytohormonal levels mirrored those observed in plants under moderate stress conditions [71,72], likely contributed to the altered phenotypic characteristics in transgenic lines (Figure 6). However, it was crucial to emphasize that the effects of expressing DXS genes on GA and ABA levels were inconsistent across different studies. For instance, homologous expression of DXS in poplar and Arabidopsis resulted in increased levels of GA and ABA [52,73], but overexpression of StDXS1 in Arabidopsis led to reduced levels of both hormones [61]. Additionally, CtDXS1 transgenic Arabidopsis exhibited lower levels of GA3 [74], while MnDXS1 transgenic Arabidopsis showed increased GA content but decreased ABA content [75]. Given the fact that the levels of GA and ABA were influenced both by the increased biosynthesis pathway due to DXS expression and by the negative feedback mechanism from accumulated metabolites [52,74], the divergent trends of GA and ABA levels observed in CbDXS1 transgenic Arabidopsis could be attributed to the interplay between the opposing effects, which requires further analysis.

Derived from these results, ectopic expression of CbDXS1 appears to redirect intracellular carbon flux from primary metabolism to terpenoid biosynthesis, which simultaneously modulates endogenous phytohormone levels through the diterpene biosynthesis pathway and amino acid metabolism, ultimately contributing to the phenotypic changes in the growth and development of transgenic lines. It should be acknowledged that the metabolomic analyses in this study were conducted using the WT and a single overexpression line (L2). Therefore, while this line represents a strong overexpression phenotype, potential insertion site effects or line-specific effects cannot be ruled out. Additionally, given that the identification of DAMs was conducted without FDR (false discovery rate) correction, the pathway enrichment results and associated biological interpretations should be regarded as exploratory. In future studies, performing analogous metabolomic profiling across multiple independent transgenic lines with FDR correction would help establish a more robust molecular basis for the phenotypic effects caused by CbDXS1 overexpression and could enable more precise strategies for the application of DXS genes in plant metabolic engineering.

5. Conclusions

In this work, the analysis results of dynamic accumulation patterns for major terpenoids in developing leaves of different C. burmannii accessions indicated that the biosynthesis of D-borneol and other primary terpenoids mainly occurred during the S3~S4 stages of leaf development. The application of full-length transcriptome sequencing facilitated the construction of the monoterpenoid biosynthesis pathway regulating CBLEO accumulation. The comprehensive analyses of the dynamic expression profiling of candidate DEGs, the correlation between terpenoid contents and DEG expression levels, and the CbDXS gene family analysis resulted in the identification of CbDXS1 as the key regulatory gene for the high accumulation of essential oils in developing leaves of C. burmannii. Notably, transgenic experiments demonstrated that ectopic expression of CbDXS1 increased DXS enzyme activity, chlorophyll content, and transcription abundances of MEP-pathway-related genes in Arabidopsis leaves. These changes were consistent with a model of redirected intracellular carbon flux from primary metabolism to terpenoid biosynthesis and altered endogenous phytohormone contents, which may underlie the observed terpenoid accumulation and phenotypic changes in transgenic Arabidopsis. Our findings elucidated the multifaceted biological functions of CbDXS1 in modulating terpenoid biosynthesis and plant development through the synergistic regulation of metabolic and regulatory networks, thereby providing scientific strategies for breeding ideal varieties of C. burmannii with high yield and high-quality essential oil.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010036/s1, Table S1: The sequence and information of primers used in this study; Table S2. Genetic analysis of transgenic A. thaliana in T3 generation; Figure S1: Analysis of the DEGs in leaves of three C. burmannii accessions at four development stages; Figure S2: KEGG analysis of up-regulated DEGs in different developmental stages of Cb-H leaves; Figure S3: KEGG analysis of up-regulated DEGs in different developmental stages of Cb-M leaves; Figure S4: KEGG analysis of up-regulated DEGs in leaves at the same developmental stages in different accessions; Figure S5: Amino acid sequence alignment for conserved domains in DXS homologs from C. burmannii (CbDXS1), Catharanthus roseus (CrDXS1, AGL40532.1), Elaeis guineensis (EgDXS, NP_001290502.1), Osmanthus fragrans (OfDXS1, AOT86855.1), Zea mays (ZmDXS1, AQK85915.1), Amborella trichopoda (AtDXS, XP_011627386.1), and Aquilaria sinensis (AsDXS1, AFU75321.1). The regions with blue underlines exhibit the conserved DXS domains, and the orange underlines indicate TPP binding sites; Figure S6: Construction of overexpression vector and identification of transgenic Arabidopsis. (a) Diagrammatic drawing of CbDXS1 overexpression vector. (b) PCR identification for transgenic Arabidopsis. M: 2000 bp DNA marker; NC: negative control, WT: wild-type Arabidopsis, L1~L8: PCR products using genome DNA of CbDXS1 transgenic lines. (c) The relative expression of CbDXS1 in Arabidopsis seedlings; the CbDXS1 expression level in line L1 was set to 1.00. (d) Relative expression of CbDXS1 in roots of transgenic Arabidopsis grown for 4 weeks. (e) Relative expression of CbDXS1 in stems of transgenic Arabidopsis grown for 4 weeks. (f) Relative expression of CbDXS1 in leaves of transgenic Arabidopsis grown for 4 weeks. The expression level of CbDXS1 in roots, stems, and leaves of line L3 was independently set to 1.00. WT: wild-type Arabidopsis; L2, L3, and L6: CbDXS1 transgenic lines. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05; Table S3: All the metabolites enriched in pathways of terpenoid biosynthesis in leaves of A. thaliana; Figure S7: DA score plots of KEGG enrichment analysis based on differential metabolites. (a) DA score plot by UPLC-MS. (b) DA score plot by GC-MS; Table S4: The metabolites involved in pathways related to carbon flux and energy generation in leaves of A. thaliana; Table S5: The metabolites related to amino acid metabolic pathways in leaves of A. thaliana.

Author Contributions

Software, Y.C., L.S., F.C. and J.Y.; validation, Y.X. and C.L.; formal analysis, Y.X.; investigation, Y.C., L.S., F.C., Q.Z. and J.Y.; resources, Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.X., C.L. and S.L.; supervision, S.L.; funding acquisition, Y.X. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32572090) and the Specific Programs in Forestry Science and Technology Innovation of Guangdong (Grant No. 2020KJCX001).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oliveira, R.C.; Carvajal-Moreno, M.; Mercado-Ruaro, P.; Rojo-Callejas, F.; Correa, B. Essential oils trigger an antifungal and anti-aflatoxigenic effect on Aspergillus flavus via the induction of apoptosis-like cell death and gene regulation. Food Control 2020, 110, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Moura, W.; de Souza, S.R.; Campos, F.S.; Sander Rodrigues Cangussu, A.; Macedo Sobrinho Santos, E.; Silva Andrade, B.; Borges Gomes, C.H.; Fernandes Viana, K.; Haddi, K.; Oliveira, E.E.; et al. Antibacterial activity of Siparuna guianensis essential oil mediated by impairment of membrane permeability and replication of pathogenic bacteria. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 146, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zhong, S.; Schwarz, P.; Chen, B.; Rao, J. Mechanisms of antifungal and mycotoxin inhibitory properties of Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil and their major chemical constituents in emulsion-based delivery system. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 197, 116575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Kang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, C.; Du, L.; Liu, F. Mechanism of antifungal activity of Perilla frutescens essential oil against Aspergillus flavus by transcriptomic analysis. Food Control 2021, 123, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Santos, R.; Andrade, M.; Madella, D.; Martinazzo, A.P.; de Aquino Garcia Moura, L.; de Melo, N.R.; Sanches-Silva, A. Revisiting an ancient spice with medicinal purposes: Cinnamon. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, N.G.; Croda, J.; Simionatto, S. Antibacterial mechanisms of cinnamon and its constituents: A review. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 120, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Zou, Y.; Luo, S.; Wei, Q. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of three isomeric terpineols of Cinnamomum longepaniculatum leaf oil. Folia Microbiol. 2020, 66, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D.R.A.; Lemarcq, V.; Alderweireldt, E.; Vanoverberghe, P.; Praseptiangga, D.; Juvinal, J.G.; Dewettinck, K. Antioxidant activity and quality attributes of white chocolate incorporated with Cinnamomum burmannii Blume essential oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, A.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Pecio, L. Coffee with cinnamon-impact of phytochemicals interactions on antioxidant and anti-inflammatory in vitro activity. Food Chem. 2014, 162, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D.R.A.; Tuenter, E.; Patria, G.D.; Foubert, K.; Dewettinck, K. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of Cinnamomum burmannii Blume extracts and their potential application in white chocolate. Food Chem. 2020, 340, 127983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dhubiab, B.E. Pharmaceutical applications and phytochemical profile of Cinnamomum burmannii. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2012, 6, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Cai, Y.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, B.; Lin, S. Reference genes selection and validation for Cinnamomum burmanni by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; An, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, X. Mining of candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of dextrorotatory borneol in Cinnamomum burmannii by transcriptomic analysis on three chemotypes. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Su, P.; Guo, J.; Jin, B.; Huang, L. Bornyl diphosphate synthase from Cinnamomum burmanni and its application for (+)-borneol biosynthesis in yeast. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 631863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y. A study on infraspecific types of cheracter of Cinnamomum burmanni. Acta Bot. Sin. 1992, 34, 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Dong, X.; Yu, Z.; Ge, L.; Lu, L.; Ding, L.; Gan, W. Borneol inhibits CD4+T cells proliferation by down-regulating miR-26a and miR-142-3p to attenuate asthma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 90, 107223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Lai, H.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Wong, Y.S.; Chen, T.; Li, X. Natural borneol, a monoterpenoid compound, potentiates selenocystine-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by enhancement of cellular uptake and activation of ROS-mediated DNA mamage. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, L.; Su, J.; Li, B.; Chen, T.; Wong, Y.S. Synergistic apoptosis-inducing effects on A375 human melanoma cells of natural borneol and curcumin. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, F.; Liu, L.; Feng, L.; Wu, X.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, Q. (+)-Borneol improves the efficacy of edaravone against DSS-induced colitis by promoting M2 macrophages polarization via JAK2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansod, S.; Chilvery, S.; Saifi, M.A.; Das, T.J.; Tag, H.; Godugu, C. Borneol protects against cerulein-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in acute pancreatitis mice model. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Xu, Q.Q.; Shan, C.S.; Shi, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; Chang, C.C.; Zheng, G.Q. Borneol for regulating the permeability of the blood-brain barrier in experimental ischemic stroke: Preclinical evidence and possible mechanism. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 2936737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Shi, L.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Xiu, Y.; He, B.; Lin, S.; Liang, D. Revelation of enzyme/transporter-mediated metabolic regulatory model for high-quality terpene accumulation in developing fruits of Lindera glauca. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, S.S.; Croteau, R.B. Strategies for transgenic manipulation of monoterpene biosynthesis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Hou, F.; Wu, T.; Jiang, X.; Li, F.; Liu, H.; Xian, M.; Zhang, H. Recent advances of metabolic engineering strategies in natural isoprenoid production using cell factories. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]