Abstract

Prunus serotina (black cherry) is native to America and has five subspecies: serotina, eximia, hirsuta, virens, and capuli. P. serotina subsp. capuli is found in Central and South America with superior fruits found in Ecuador. These have large, juicy, and tasty fruits used for human consumption. They are available in produce markets and have important nutraceutical properties. However, no commercial cultivars of capuli are currently available. The main goal of this research was to understand if different morphological characters can differentiate unique populations of P. serotina subsp. capuli present in Ecuador. Morphological traits (tree, leaf, and flower) of plants grown from the OP seeds of 44 capuli accessions collected from three provinces of Ecuador (Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, and Tungurahua) were characterized in 2019 and 2020. Tree measurements included the number of primary branches and growth habit. Leaf measurements included petiole length, leaf area, leaf height, leaf width, leaf apex angle, and leaf basal angle. Flower measurements included pedicel length, flower width, and flower length. Raceme length, number of racemes per branch, and number of flowers per raceme were also characterized. ANOVA were performed with significant differences observed among capuli accessions for all variables measured. No clear differences were observed across regions with PCA and cluster analysis that may support the presence of different populations.

1. Introduction

Prunus serotina Ehrh. is the largest native cherry tree in the United States. It belongs to the family Rosaceae, subfamily Spiraeoideae, and tribe Amygdaleae [1]. The tree can grow to be 30.48 m in height and 1.5 m in diameter. It can grow 6.35 cm in diameter per decade between 13 and 33 years of age [2]. Multiple taxonomic treatments have been proposed throughout the decades for P. serotina and its subspecies/varieties [3]. Among those, McVaugh [3] reported that the basic differences among the different subspecies of P. serotina are due to the morphological differences in leaves, inflorescences, and flower size. In this taxonomic treatment, Prunus serotina is constituted by five subspecies: P. serotina subsp. serotina, P. serotina subsp. hirsuta (Elliot) McVaugh, P. serotina subsp. virens (Woot. and Standl.) McVaugh, P. serotina subsp. eximia (Small) McVaugh, and P. serotina subsp. capuli (Cav. Ex Spreng.) McVaugh [3]. McVaugh [3] made a thoughtful description and overview of the different proposed relationships at the time and the geographical differences within P. serotina subspecies/varieties. McVaugh [3] states that all the morphological information of any species will provide a taxonomist with the basic idea of what a species is really like. Hereafter, we used the McVaugh [3] taxonomic treatment for P. serotina as the basis of the subspecies relationships in our study.

Prunus serotina subsp. capuli is commonly found growing in Mexico, Perú, Colombia, Guatemala, and Ecuador, with its best fruit forms growing in the Ecuadorian Andes region [4]. It has been used from olden times for the treatment of diseases such as diarrhea and cough [5]. The essential oils from leaves have vasorelaxant properties [6]. Other benefits of the capuli tree include its use within an agroforestry system to prevent erosion and as a wind barrier [7].

The capuli tree in Ecuador can reach up to 15 m in height. Capuli leaves have a dark green upper surface and pale green lower surface. They are mostly oblong lanceolate in shape with fine serrations. They can be 7 to 14 cm long. Its flowers are white, held on racemes. The racemes can be 10 to 25 cm long [4]. The flowers are 35 mm in length and its petals are around 3.5 mm in length and width. The anthers and style are around 0.8 mm and 1.7 mm in length, respectively [3]. Capuli fruit are round and glossy and are abundantly available in Andean markets [7].

The morphological characterization of different plant parts (trunk, branches, leaves, flowers, fruit, etc.) of a representative group of individuals within and across species constitute an important technique to understand the diversity of horticultural crops [8]. Diverse germplasm can be characterized due to such morphological differences [9]. The data obtained through phenotyping can be then analyzed using data reduction techniques such as PCA (Principal component analysis). PCA helps in identifying patterns in data by regrouping correlated variables into the small sets of original variables [10].

The main objective of this research was to understand if different morphological characters can differentiate unique populations of P. serotina subsp. capuli present in Ecuador. Our goal was to characterize the morphological variation present in OP (open pollinated) seedlings from 44 P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions collected from three different provinces of Ecuador (Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, and Tungurahua) growing in Griffin, GA, USA. The information obtained in this study will aid the preservation and conservation of these species. In addition, it will provide basic morphological data for future capuli breeding programs in Ecuador and the U.S.

2. Materials and Methods

Plant material: Fruit from 44 genotypes of P. serotina subsp. capuli growing in 3 provinces (Chimborazo, Cotopaxi, and Tungurahua) in the Andes region of Ecuador were collected in 2016. Each genotype was given a unique ID based on their collection site. Plant collection permit MAE-DNB-CM-2019-0107 from the Minister of Environment of Ecuador was used for access and use of these genetic resources. Genotypes were selected to represent a broad geographical range (~5–10 km separation between collection sites) in the region. At least 100 ripe fruits per plant were collected in plastic bags and stored in a cooler with ice after collection. Endocarps were washed and left to dry for 48 h in paper towels. Seed lots of 50 seed per accession then were transported to the Peach Research and Extension program at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA following procedures from the USDA seed importation permit P37-16-00098. Leftover seed per accession were kept by collaborators at the Escuela Politécnica del Chimborazo (ESPOCH) and currently are grown in a germplasm collection on-site. Additional information about accessions can be found in Pathania et al. [11].

Seeds were imbibed in water for 4 d, with water being replaced every 24 h. Seeds then were transferred to a Captan 4 L solution (7.5 mL of Captan per 1 L of water) for 24 h to treat the seeds against molds and other rots. For stratification and germination, seeds were placed in perlite moistened with Captan in a refrigerator at 4 °C. Once the seeds started to germinate, they were planted in 50 cell trays (A.M. Leonard, Piqua, OH, USA) filled with a 3:1 germination mix media and perlite. Osmocote slow-release fertilizer (15-9-12) 5–6 month was added to the media prior to planting (approximately ½ cup per 4 gallons of media). Seedlings were grown and maintained in a greenhouse until being transplanted in the 2017 season. The seedlings were labeled throughout the process and seedling lots/accessions were given the same ID as their mother plants (Table 1). Accessions were transplanted directly to the field at the Dempsey Research Farm, Griffin, GA, USA. They were planted in a high-density nursery.

Table 1.

List of Prunus serotina subsp. capuli accessions collected in the Andes region of Ecuador growing in University of Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA.

Morphological characters: Leaves, racemes, and flowers were collected and characterized in summer 2019 and 2020. A total of 44 accessions (seedling lots) and five genotypes per accession were used throughout the study. Table 2 lists all the studied variables.

Table 2.

List of variables and their units used for the morphological characterization of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown in Griffin, GA, USA.

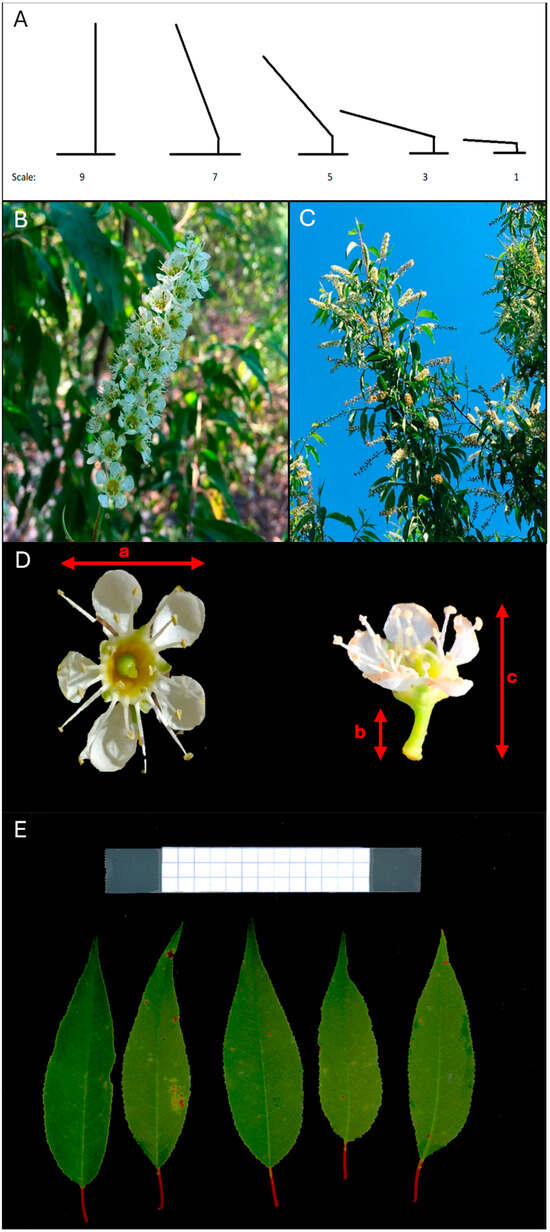

The number of 1st order branches was measured for each genotype within each accession. The measurements were taken in December 2019 and December 2020. The number of 1st order branches was counted from the base of the plant to the top. Plant growth habit was evaluated using a subjective scale of 1 (leaning) to 9 (upright) in December 2019 and December 2020 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Prunus serotina subsp. capuli plant attributes used for morphological characterization of different accession. (A) Graphical representation of the plant growth habit scale. (B) A raceme with flowers. (C) Racemes on the branch of a capuli tree. (D) Open flower with flower measurements taken for (a) Flower width, (b) Flower pedicel length, and (c) Flower length (mm). (E) Leaves with measurements taken using ImageJ software. A graph paper was used as a scale reference—5 mm.

Capuli flowers are borne on a raceme (Figure 1B,C). The total number of racemes per branch for three different branches within each genotype per accession were counted. Racemes and flowers open early April, and they were collected in the first and second week of April for both years 2019 and 2020. The first genotypes to bloom were observed in 2018, with most of genotypes blooming in 2019. For flower and raceme measurements, three racemes were randomly collected per genotype per accession. Raceme length (mm) was measured for all collected samples. The number of leaves and flowers on each raceme were counted. Further, three flowers from each raceme were used to measure flower length (mm), flower width (mm), and pedicel length (mm) (Figure 1D). A digital caliper was used for all these measurements. Fruit set was not present in both years.

For leaves, a total of 5 leaves per accession were phenotyped. Samples were collected and stored in a cooler with ice until transported to UGA Griffin campus, Griffin, GA, USA. Samples were then stored in a fridge at 4 °C for 24 h before processing. A flat bed scan brand Epson Perfection V600 with Epson Scan software v3.9.3.1 (Epson America Inc., Los Alamitos, CA, USA) was used to scan leaves. Image Scanner settings were 48-bit color with an 800 dpi resolution. ImageJ software v1.52p (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to process and to measure the scanned images for leaf area (mm2), leaf width (mm), leaf height (mm), petiole length (mm), apex angle (°), and basal angle (°) (Figure 1E). A graph paper reference scale of 5 mm was used for scanning. Data were taken from the same plants of each accession when possible every year but due to high density planting, some trees were weak or could not survive and died at the end of the second year of data collection.

Accession PserTU57/53 either belongs to accession PserTU57 or PserTU53 but due to uncertainty at the time of planting, it was planted separately at the end of the last row in the nursery. To avoid any data loss, we measured this accession for all variables and the data were included in the mean separation as well. However, this accession was not included in the multivariate, Principal component analysis (PCA), and cluster analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of variance were performed on all measurements with accession, year, and accession × year as main effects in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA) using PROC GLIMMIX. Means were separated using LSD test with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Multivariate, Principal component analysis (PCA), and cluster analysis were performed with all the variables in JMP v.14 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

Prunus serotina is classified into five subspecies with unique leaf, flower, and fruit morphological characteristics [12]. McVaugh [3] reported these unique characteristics per subspecies to better differentiate these subspecies as follows: (1) Leaves of P. serotina subsp. serotina are 4 cm wide and 9 cm long. Its flowers have a 4.5 mm long pedicel with approx. 35 flowers per raceme. The flowering branch in (2) Prunus serotina subsp. hirsuta has around 45 flowers per raceme with a 2.5–5 mm long pedicel. Its leaves are 4.5 cm wide and 8.5 cm long. (3) Prunus serotina subsp. virens has leaves 2–3 cm wide and 4.5–7 cm long with a 5–7 mm long petiole. The flower pedicels are 3.5 mm long with approx. 30 flowers per raceme. (4) Prunus serotina subsp. eximia leaves are 3–4.5 cm in width and 7–9 cm in length. Its petiole is 1.5–2 cm in length. The flowering branch of subspecies eximia is about 12 cm long and has 40 flowers. (5) Prunus serotina subsp. capuli has a 15 cm flowering branch with approx. 35 flowers. Its pedicel is 4 mm long. The second floral leaf in capuli is about 6 cm long and 2.2 cm in width [3].

Diverse morphological characteristics have been used to differentiate the subspecies of P. serotina. The main objective of this research was to better characterize the morphological variation in P. serotina subsp. capuli using accessions collected from Ecuador in 2016 and currently growing at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA. Our hypothesis was that no leaf, flower, and plant morphological variation was present within the accessions collected in Ecuador that could differentiate unique populations of P. serotina subsp. capuli.

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 represent the ANOVA tables for the different morphological characters analyzed (plant, leaf, and flower) in this research. Statistical differences were observed among all accessions for all variables analyzed (p ≤ 0.05). A year effect was significant for all the studied variables except for leaf basal angle. Interaction of accession and year effects were significantly different for all variables except for number of 1st order branches, growth habit, leaf apex angle, and leaf basal angle. Hereafter, to keep a uniformity in analyses and for easy data representation, within year mean comparisons across all the variables will be presented.

Table 3.

ANOVA for branching and tree growth variables for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

Table 4.

ANOVA for raceme and flower variables for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli from Ecuador grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

Table 5.

ANOVA for leaf variables for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli from Ecuador grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

3.1. Plant Measurements

Table 6 reports the data collected for tree growth habit and branching variables. The number of 1st order branches was found to be the largest for PserCH113 with 67.4 in 2019 and 41.8 in 2020. The least number of 1st order branches was found in PserCH86 (21.6) for 2019 and PserCO21(15.8) for 2020 (Table 6). PserCO16 and PserTU53 had the highest score for plant growth habit, which represents upright growth for 2019 and 2020, respectively. On the other hand, accessions PserTU48 were found to be more leaning/less upright in their growth for 2019. PserCO09, PserCO31, and PserCO21 were less upright for 2020.

Table 6.

Branching and tree growth characteristics for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

Capuli is an important tree used for timber and agroforestry purposes [13]. The trees that are upright and with a reduced number of 1st order branches would be more desirable for use as timber species. This would ease their use for making furniture. PserCH99 and PserCH153 are accessions that have a mixture of these characteristics, which can be further used as selections for timber purpose.

Marquis [14] also mentioned black cherry to be extremely sensitive to shade and competition. He mentioned the need of an open canopy space during the initial years of growth, otherwise they start to have reduced growth and even die. The reason for the reduced number of primary branches could be due to the error in the counting or increased competition for the plants or both. Most of the primary branches in the accessions were located only at the very top of the tree in the second year. This was also observed in Impatiens pallida where most of the primary branches in the crowded population stand was located at the top of the tree [15].

3.2. Flower and Raceme Measurements

Table 7 presents the results of the flower measurements for the years 2019 and 2020. The flower length varied from 11.2 mm to 5.7 mm in 2019 and 9.1 mm to 5.2 mm in 2020. PserCH112 and PserCH127 had the highest flower length in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The flower width varied from 5.0 mm to 2.9 mm in 2019 and 4.3 mm to 2.2 mm in 2020. PserCO31 and PserTU81 had the highest flower width in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Pedicel length varied from 5.6 mm to 2.0 mm in 2019 and 4.1 mm to 2.0 mm in 2020. PserCH112 and PserCO22 had the highest pedicel length in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Table 7.

Flower variables for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

Results of the raceme measurements for the year 2019 and 2020 are reported in Table 8. The number of racemes per branch in 2019 varied from 0.7 to 18.5 and 3.4 to 11.4 in 2020. PserCO13 and PserCO31 had the highest number of racemes per branch in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The range of numbers of flowers per raceme varied from 12.9 to 30.7 in 2019 and 12.0 to 23.2 in 2020. PserTU75 and PserCO16 had the highest number of flowers per raceme in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The maximum number of basal leaves per raceme were 6.4 and 6 in 2019 and 2020, respectively. PserCO16 and PserTU41 had the highest number of leaves per raceme in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The raceme length ranged from 8.1 cm to 20.8 cm in 2019 and 9.7 cm to 17.8 cm in 2020. PserTU41 had the highest raceme length in 2019 and 2020. McVaugh [3] reported that branch bearing flowers on a capuli tree are usually 15 cm long with 35 flowers, somewhat consistent with the data range for this research. Also, he stated that racemes bear usually 1–4 leaves on their lower end and 30–36 flowers on the distal end. Avendaño-Gómez et al. [16] reported around average 30 flowers on the inflorescence and raceme length 9.66 ± 2.36 cm in cultivated forms of capuli in Tlaxcala, Mexico. The raceme length and number of flowers on raceme reported in our data are comparable to those found by McVaugh [3] and Avendaño-Gómez, Lira-Saade, Madrigal-Calle, García-Moya, Soto-Hernández, and Romo de Vivar-Romo [16].

Table 8.

Raceme variables for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

Fruit count and yield is related to the number of flowers and flowering buds in the sour cherry [17]. PserCO13, PserCO16, and PserCO31 are some of the accessions with higher flower count on a raceme and racemes on a branch. With the proper spacing and growth environment, the potential of these accessions could be further evaluated in regard to high yield and fruit count for the capuli fruits in the Southeastern US.

McVaugh [3] used flower and inflorescence sizes along with leaf characters as the main descriptors to classify individual subspecies of Prunus serotina. Subspecies capuli were reported to have a 15 cm long raceme with approx. 35 flowers. Its flower pedicel was reported to be around 4 mm long. The leaves were 2.5–4 cm wide and 8–12 cm long with a petiole of 1–2 cm long. The second floral leaf in capuli was about 6 cm long and 2.2 cm wide. Our observations are consistent with McVaugh’s (1951) report. In other species, similar studies have been used for morphological characterization. For example, Rodrigues et al. [18] reported flower diameter in sweet cherries ranging from 2.9 to 3.7 cm and in sour cherries from 2.5 to 3 cm, all from Portugal.

3.3. Leaf Measurements

Results of the leaf measurements are listed in Table 9. The leaf width ranged from 19.4 mm to 30.4 mm (2019) and 16.1 mm to 28.1 mm (2020). The leaf height ranged from 78.6 mm to 112.9 mm (2019) and 51.2 mm to 100.4 mm (2020). Leaf area ranged from 931.6 mm2 to 2022.7 mm2 (2019) and 460.3 mm2 to 1569.7 mm2 (2020). The largest leaf area, width, and height in 2019 was reported for PserTU41 and in 2020 for PserCO31. Petiole length ranged from 6.1 mm to 14.3 mm (2019) and 4.7 mm to 10.4 mm (2020). Leaf apex angle ranged from 17.5° to 32.2° in 2019 and 19° to 56.5° in 2020. Leaf basal angle ranged from 75.6° to 110.3° in 2019 and 72.7° to 109.7° in 2020. PserCO13 and PserCH132 had the highest leaf apex angle in 2019 and 2020. PserCH138 and PserCO31 had the highest leaf basal angle in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Table 9.

Leaf variables for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA in seasons 2019 and 2020.

McVaugh [3] reported the second floral leaf in capuli to be 10–36 mm in width and 25–95 mm in length with petioles 5–20 mm long. This report was consistent with our data. Similar studies have been conducted with other Prunus species. Khadivi-Khub and Anjam [19] observed that the leaf length in wild P. scoparia species from Iran varied from 55.2 mm to 15.10 mm while leaf width varied from 1.60 to 9.2 mm. Similarly, in almonds from Iran, the leaf length varied from 8.56 to 3.90 cm and width from 2.88 cm to 1.38 cm. Also, petiole length varied from 0.91 to 3.39 cm [20].

Other studies have also shown variation in leaf characteristics. For example, leaf width varied from 43.20 to 62.20 mm (sweet cherries), 22.08 to 46.16 mm (sour cherries), and 34.50 to 51.90 mm (duke cherries) from Iran [21]. In the same study, leaf length varied from 99 to 130.30 mm (sweet cherries), 39.07 to 81.03 mm (sour cherries), and 80.50 to 104.80 mm (duke cherries). For petiole length, sweet cherries ranged from 21.90 to 39.50 mm, sour cherries 6.56 to 17.93 mm and 10.60 to 17.80 mm in duke cherries [21]. Rodrigues, Morales, Fernandes and Ortiz [18] studied the morphological characterization of nine sweet and eight sour cherry cultivars in a germplasm bank in Portugal. The apical angle in the study ranged from 60° to 72° and basal angle ranged from 62° to 106.24°. The sweet cherries leaf length varied from 12 to 16 cm and width from 6 to 7 cm. In the case of sour cherries, the length varied from 7 to 12 cm and width from 4 to 6 cm.

PserCO31 and PserTU41 were the accessions with high leaf area, width, and height. The capuli leaves have vasorelaxant effects [6]. The leaves of the capuli are also used in the form of tea and syrups for treatment of diseases like hypertension, diarrhea, and malaria from earlier times [22]. Also, capuli leaves plays a role in the cure of tonsillitis [13]. Although, further scientific research is required for the nutritional analysis of the capuli leaves. Still, selecting trees with larger leaf parameter values will be a foundational base for breeding programs with nutrition objective in mind.

3.4. Multivariate Analysis

The results of the multivariate analysis are reported in Table 10. Accession PserTU57/53, which either belongs to PserTU57 or PserTU53, was not included. Raceme characteristics were positively and significantly correlated to each other (rFCvs.BLN = 0.40, rRLvs.FC = 0.68, p ≤ 0.05). Flower width and pedicel length were positively correlated with flower length (rFWvs.FL = 0.65, rFPLvs.FL = 0.81, p ≤ 0.05). Flower length and pedicel length were weakly positively correlated with raceme length (rFLvs.Rl = 0.45, rFPLvs.RL = 0.45; p ≤ 0.05). Leaf measurements such as petiole length, leaf width, height, and area were positively correlated with each other (rLAvs. LPL = 0.44, rLAvs.LW = 0.84, rLHvs.LW = 0.55; p ≤ 0.05). Similar results were detected for leaf variables by other authors in other Prunus species [21,23,24]. Leaf apex angle was weakly negatively correlated with leaf petiole length (rLAAvs.LPL = −0.31, p ≤ 0.05) and leaf height (rLAAvs.LH = −0.48; p ≤ 0.05). Growth habit and number of primary branches were not related significantly with any other variable. Overall, there were significant positive correlations observed within variables of same phenotypic category (flower, leaf, or raceme characteristics), but not across the phenotypic variables of different category.

Table 10.

Multivariate analysis of all flower, leaf, and plant growth characteristics averaged across seasons 2019 and 2020 for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia, Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA.

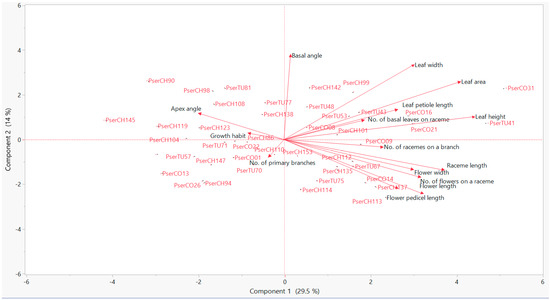

Principal Component Analysis and Dendrogram: Figure 2 and Table 11 show the result of Principal component analysis. Accession PserTU57/53 was not included. The first principal component (PC1) explains only 29.5% of the total variation and the second principal component (PC2) explains only 14%. The variables raceme length, flower length, leaf area, and leaf height were related to PC1. A scatter plot was prepared for PC1 and PC2 showing the relationships between the accessions based on studied morphological variables (Figure 2). An increase in the value for raceme length, flower length, leaf area, and leaf height were seen in the accessions from left to right on the PC1. The decrease in the value of the number of primary branches was observed in the accessions along with the negative to positive line of PC2. Also, the increase in the leaf area, leaf width, and basal angle was seen along with the negative to the positive slope of PC2. Khadivi, Mohammadi and Asgari [21] also reported similar results while studying morphological characteristics of sweet cherry, sour cherry, and duke cherry from Iran where PC1 was related with leaf height and PC2 with tree growth vigor and branching.

Figure 2.

Principal component analyses for plant, leaf, and flower morphological characters of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions grown at the University of Georgia Dempsey Farm, Griffin, GA, USA.

Table 11.

Eigenvectors for first 6 PCs for OP seedlings of P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions morphological characters grown at the Dempsey Farm in Griffin Campus, Griffin, GA, USA.

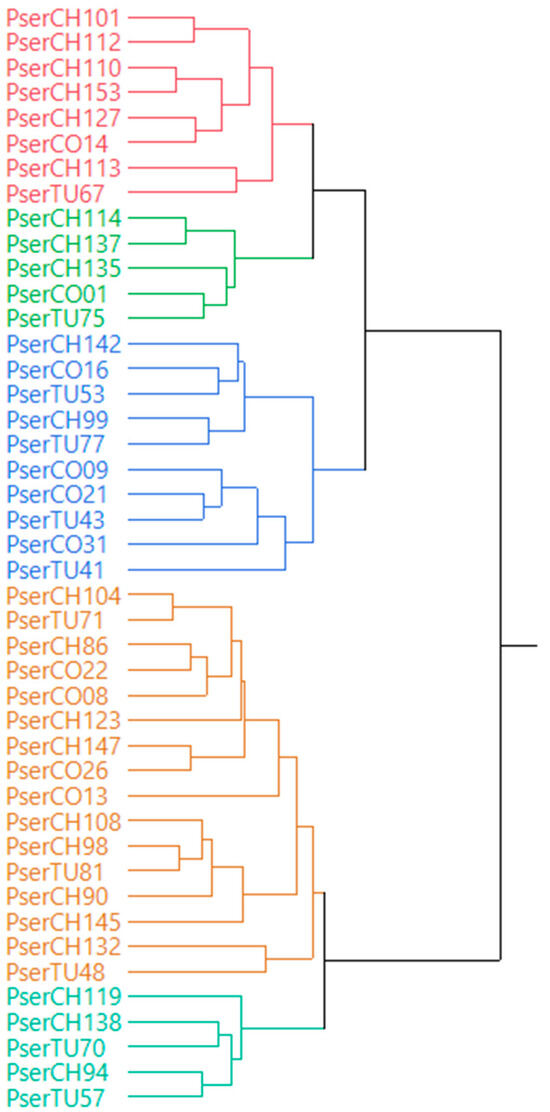

A dendrogram was made based on Ward’s minimum variance method using the studied morphological traits (Figure 3). The dendrogram classified the accessions according to the groups which are most similar. The accessions were differentiated into five main clusters (Figure 3). The first cluster included accessions, such as PserCH101, PserCH112, PserCO14, and PserTU67, which are associated with higher flower measurement values. The second cluster included accessions related to higher raceme measurement values such as PserCH114, PserCH137, PserCH135, PserCO01, and PserTU75. The third cluster includes accessions such as PserCO31, PserCO16, and PserTU41. This cluster was related with the accessions having higher values of leaf measurements and basal angle. The four and fifth cluster included accessions such as PserCH104, PserCH119, PserCO22, PserCO08, PserTU71, and PserTU81. They were clustered mainly based on variables like apex angle, growth habit, and number of primary branches. The clusters identified were not consistent with the provinces of origin for the accessions used in this study. The results from our study could be due to the self-incompatibility and outcrossing nature of these species. Rakonjac, Mratinić, Jovković, and Fotirić Akšić [24] also found similar results while studying morphological variability in wild cherry from Central Serbia.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram based on the Ward’s minimum variance method for the studied P. serotina subsp. capuli accessions based on morphological characters. Colors represent sub-clades within the overall study.

4. Conclusions

Characterization and variability of the morphological data are important for selection of the desired accessions in any new breeding program. Significant variability for the different characteristics studied were found among the different capuli accessions. The results of this study can be useful for future capuli breeding programs. The capuli as a tree is useful in several ways and has numerous benefits. Apart from growing capuli for its high-quality fruit, the use of its timber and its other medicinal are known [6]. Our study confirmed a diverse morphological variation present for leaf, flower, and plant characteristics within the accessions collected in Ecuador. No unique populations of P. serotina subsp. capuli could be differentiated using these morphological characteristics. Capuli holds a commercial potential in Ecuador, and it is an interesting species to be evaluated in the U.S. The proper use of scientific information and our preliminary data generated supports capuli as an interesting species that could be used locally and internationally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J.C.; formal analysis, S.P. and D.J.C.; investigation, S.P., D.J.C., R.A.I., L.F.L., C.R.C., V.L.C. and J.C.C.; resources, D.J.C. and R.A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and D.J.C.; writing—review and editing, S.P., R.A.I., and D.J.C.; supervision, D.J.C.; funding acquisition, D.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research in U.S. was funded by the Georgia Research Foundation, Hatch Project GEO00766, Department of Horticulture, and the University of Georgia. The research in Ecuador was funded by ESPOCH in accordance with our collaborative research agreement between institutions.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our collaborators at ESPOCH as well as the technical help of the Department of Horticulture.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Potter, D.; Eriksson, T.; Evans, R.C.; Oh, S.; Smedmark, J.E.E.; Morgan, D.R.; Kerr, M.; Robertson, K.R.; Arsenault, M.; Dickinson, T.A.; et al. Phylogeny and classification of Rosaceae. Plant Syst. Evol. 2007, 266, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, A.F. Silvical characteristics of black cherry (Prunus serotina). In Station Paper NE-139. Upper Darby; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station: Upper Darby, PA, USA, 1960; Volume 139, 26p. [Google Scholar]

- McVaugh, R. A revision of the North American black cherries (Prunus serotina ehrh., and relatives). Brittonia 1951, 7, 279–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popenoe, W.; Pachano, A. The Capulin Cherry. Bull. Pan Am. Union 1923, 56, 152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Villamar, A.A. Atlas de las plantas de la medicina tradicional Mexicana; Instituto Nacional Indigenista, INI: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Alvarado, C.; Rojas, A.; Luna, F.; Rojas, J.I.; Rivero-Cruz, B.; Rivero-Cruz, J.F. Vasorelaxant constituents of the leaves of Prunus serotina “capulin”. Rev. Latinoamer. Quím. 2009, 37, 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; Volume 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazek, J. A survey of the genetic resources used in plum breeding. In Proceedings of the VIII International Symposium on Plum and Prune Genetics, Breeding and Pomology, Lofthus, Norway, 5–9 September 2024; Volume 734, pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ganopoulos, I.; Moysiadis, T.; Xanthopoulou, A.; Ganopoulou, M.; Avramidou, E.; Aravanopoulos, F.A.; Tani, E.; Madesis, P.; Tsaftaris, A.; Kazantzis, K. Diversity of morpho-physiological traits in worldwide sweet cherry cultivars of GeneBank collection using multivariate analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzoni, A.F.; Pritts, M.P. Applications of Principal Component Analysis to Horticultural Research. HortScience 1991, 26, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, S.; Itle, R.A.; Chávez, C.R.; Lema, L.F.; Caballero-Serrano, V.; Carrasco, J.C.; Chavez, D.J. Fruit Characterization of Prunus serotina subsp. capuli. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresnedo-Ramírez, J.; Segura, S.; Muratalla-Lúa, A. Morphovariability of capulín (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) in the central-western region of Mexico from a plant genetic resources perspective. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011, 58, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.; Davenport, T.L. Underutilized fruits of the Andes. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, D.A. Prunus serotina Ehrh. Black Cherry. Silv. N. Am. 1990, 2, 594–604. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, J.; Berntson, G.M.; Thomas, S.C. Competition and growth form in a woodland annual. J. Ecol. 1990, 78, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Gómez, A.; Lira-Saade, R.; Madrigal-Calle, B.; García-Moya, E.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Romo de Vivar-Romo, A. Management and domestication syndromes of capulin (Prunus serotina Ehrh ssp. capuli (Cav.) McVaugh) in communities of the state of Tlaxcala. Agrociencia 2015, 49, 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni, A.F.; Mulinix, C.A. Yield components among sour cherry seedlings. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1992, 117, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.C.; Morales, M.R.; Fernandes, A.J.B.; Ortiz, J.M. Morphological characterization of sweet and sour cherry cultivars in a germplasm bank at Portugal. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2007, 55, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadivi-Khub, A.; Anjam, K. Morphological characterization of Prunus scoparia using multivariate analysis. Plant Syst. Evol. 2014, 300, 1361–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadivi-Khub, A.; Etemadi-Khah, A. Phenotypic diversity and relationships between morphological traits in selected almond (Prunus amygdalus) germplasm. Agroforest. Syst. 2014, 89, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadivi, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Asgari, K. Morphological and pomological characterizations of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.), sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) and duke cherry (Prunus × gondouinii Rehd.) to choose the promising selections. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M. Plantas Útiles de la Flora Mexicana; Ediciones Botas: Mexico City, Mexico, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Rakonjac, V.; Akšić, M.F.; Nikolić, D.; Milatović, D.; Čolić, S. Morphological characterization of ‘Oblačinska’ sour cherry by multivariate analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 125, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakonjac, V.; Mratinić, E.; Jovković, R.; Fotirić Akšić, M. Analysis of Morphological Variability in Wild Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Genetic Resources from Central Serbia. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2014, 16, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).