Abstract

In this study, thirty yeast strains isolated from the gut of coprophagous “Gymnopleurus sturmi” and twenty-four from the dung of ruminants were shown to be producers of cellulases. Cellulolytic yeast isolates could also produce other hydrolytic enzymes such as pectinase, lipase, β-glucosidase, catalase, inulinase, urease, gelatinase, and protease. The oroduction of amylase was present in only one isolate of dung of ruminants. On the other hand, the production of tannase was absent in these isolates. All the yeasts isolated from two sources could utilize various carbon sources, including sorbitol, sucrose, and raffinose, and withstand high concentrations of glucose (300 g/L), salt (100 g/L), and exogenous ethanol. They could grow in a wide pH range of 3 to 11. The growth was stable up to a temperature of 40 °C for isolates from the gut of coprophage and 37 °C for the yeast from the dung of ruminants. These activities and growing conditions were similar to the diet of coprophagous insects and the composition of ruminant manure, likely because the adaptation and distribution of these microorganisms depend on the phenology and trophic preferences of these insects.

1. Introduction

Yeasts are unicellular eukaryotic microorganisms with the ability to multiply rapidly because they are less demanding in nutrients. They are easily implemented in several farms, research, and industrial applications [1,2]. Indeed, they represent the largest group of exploited microorganisms compared to prokaryotes [3]. Yeasts play an essential role in recycling organic matter by drawing their energy from external carbon sources [4]. They can also cohabit in various environments where the living conditions are specific, such as acidic environments, tree bark, digestive tract, and insect dung [1,5,6,7,8]. Yeasts are widely used in food fermentation industry and making more progress in other industries [2,9]. They represent an important source to be exploited to develop new and very extensive biotechnological processes as they have a highly developed enzymatic system [10]. Indeed, yeasts can produce enzymes such as cellulases, ligninase, xylanase, pectinase, amylase, glucoamylase, and lipase (Table 1) [11] for applications in various industrial processes, which require the use of specific thermostable enzymes [12]. Several types of research have been reported on the ability of yeast strains to hydrolyze plant-derived substrates to provide an alternative to chemical hydrolysis for bioenergy production.

In this context, we have established a collection of yeasts isolated from various ecological niches; the digestive tract of a coprophagous beetle “G. sturmi” and ruminant dung, a food source for this insect. The choice of these sources is based on the fact that coprophagous beetles constitute a group of beetles well-adapted to grazed ecosystems [13], as they derive their food resources from the dung of large mammals [14]. This dung could be of carbohydrate origins, or lipid- or phenolic-dominant. The degradation of these compounds can be done through a system of enzymes secreted by the microorganisms colonizing the digestive tract of the animals or the microorganisms specific to the dung, in particular the cellulases to degrade the cellulose not transformed by the animals. These cellulases could be used for industrial applications due to their great biotechnological potential, and recycling of cellulosic biomass [15,16]. This research is focused on the isolation and screening of various yeast isolates from the gut and dung of coprophagous insect Gymnopleurus sturmi for biotechnological applications.

Table 1.

Technological applications of yeast isolates.

Table 1.

Technological applications of yeast isolates.

| Enzymes | Yeasts | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulases | Aureobasidium pullulans 98 | Food, chemical, textile, paper, and biofuel industries | [17,18] |

| Pectinase | Kluveromyces marxianus Metschnikowia pulcherrima | Wine, cider, and fruit juice industries | [19,20] |

| Lipase | Aureobasidium pullulans HN2.3 | Food, wastewater treatment, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, leather processing, and biofuel industries | [21] |

| ß-glucosidase | Guehomyces pullulans 17-1 | Food industry | [22] |

| Catalase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Food industry | [23] |

| Inulinase | Pichia guilliermondii | Food, beverage, and biofuel industries | [24] |

| Urease | Cryptococcus gattii | Diagnostic kits, beverages, and animal feed | [25] |

| Gelatinase | Trichosporon pullulans | Food, chemical, and medical industries | [26] |

| Protease | Rhodotorula mucilaginosa L7 | Clinical applications, food, beverage, and leather processing industries | [27] |

| Amylase | Aureobasidium pullulans N13dSaccharomyces cerevisiae | Food, textile, paper, detergent industry, medical, and pharmaceutical industries | [28,29] |

| Tannase | Kluyveromyces marxianus | Feed, food, beverages, brewing, pharmaceutical, chemical, cosmetic, and leather industries | [30] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

The coprophagous organisms and ruminant dung used for this study were collected in June 2015 and 2016 from two different regions of Fez, Morocco; Fez sais (33°54′14′′ N, 4°59′55′′ W), at 609 m of altitude, Ain Aicha (34°29′59′′ N, 4°42′01′′ W), at 246 m of altitude, Ain Aicha (34°29′59′′ N, 4°42′01′′ W), at 246 m of altitude, and Ain Beda (33°57′07.5′′ N, 4°53′59.9′′ W), at 579 m of altitude.

The isolation of the yeasts was carried out from the gastrointestinal tract of the coprophagous “Gymnopleurus sturmi” and the ruminate dung on Yeast Pepton Glucose (YPG) culture medium, comprised of Peptone (20 g/L), yeast extract (10 g/L), glucose (20 g/L), agar (20 g/L), and with two antibiotics, ampicillin (60 μg/mL) and kanamycin (60 μg/mL), used to prevent bacterial growth.

2.2. Qualitative Screening of Isolates for Hydrolytic Enzymes

The different yeast isolates were tested for their ability to produce hydrolytic enzymes.

2.2.1. Oxidation of Phenolic Substrates

The determination of the capacity of all the isolates to utilize and degrade phenolic substrates was carried out on the M9 culture medium, comprising of (g/L) Na2HPO4 (6 g), KH2PO4 (3 g), NH4Cl (1 g), and NaCl (0.5 g) with 0.1% of catechol or pyrogallol. The positive result was visualized by a black coloration around the isolate, indicating assimilation of these substrates.

2.2.2. Cellulase Activity

This activity was determined using carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) agar medium as a source of carbon. The M9 buffer consists of (g/L) Na2HPO4 (6 g), KH2PO4 (3 g), NH4Cl (1 g), and NaCl (0.5 g). The medium was autoclaved for 15 min at 120 °C. Then, 1 mL of 0.1 M CaCl2 and 1 mL of MgSO4 at 1 M were added. The cellulase medium was composed of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) or cellulose fiber (10 g), yeast extract (0.2 g), agar (20 g), and the M9 buffer. The final medium was autoclaved for 15 min at 110 °C [31]. The yeast was incubated on the prepared medium for 72 h at 30 °C. After that 1%, Congo red was flooded, which selectively binds to the polymers of cellulose. After 15 to 20 min, the dishes were washed several times with NaCl (1 M). The presence of a light halo around the colonies indicates the degradation of the CMC in the medium by the cellulase secreted from the isolates that were called “cellulase +” [32].

2.2.3. Amylase Activity

Yeast isolates with amylase activity were detected by cultivation on a starch agar medium. This culture media was comprised (g/L) of peptone (2 g), MgSO47H2O (0.5 g), CaCl2 (0.2 g) NaCl (0.5 g), and starch (1 g). Isolates possessing the amylase enzyme were able to degrade the starch present in the agar, thus developing a clear zone around the colonies. The evidence of starch degradation by the secreted enzyme was confirmed after adding Lugol and rinsing with distilled water [33].

2.2.4. Inulinase Activity

Inulinase production by the isolated yeasts was detected on a medium containing inulin (2 g), yeast extract (0.5 g), KH2PO4 (3 g), agar (20 g), and distilled water (1 L). Inulin was used as the only carbon source in this medium; yeast growth after 4 days of incubation at 30 °C showed the presence of inulinase activity [34].

2.2.5. β-Glucosidase Activity

The β-glucosidase activity was carried out in a medium containing (g/L) yeast extract (1 g), peptone (1 g), ferric ammonium citrate (0.01 g), esculin (0.3 g), and agar (20 g). The Petri dishes inoculated with yeast cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 24 to 48 h. The presence of enzymatic activity was visualized as a dark halo surrounding yeast growth [35].

2.2.6. Pectinase Activity

To check the pectinase activity of the isolates, yeast cultures were grown on a medium based on (g/L) pectin (2.5 g), yeast extract (5 g), (NH4)2SO4 at 10% (5 mL), 1 M MgSO4 (0.5 mL), 50% glycerol (5 mL), and agar (20 g). The pH of the culture medium was adjusted to 8.0. The medium was autoclaved at 120 °C for 15 min [36]. The pectinase secretion was detected by adding lugol (selectively binding to the pectin polymers) and a successive rinsing of the dishes with distilled water after 10–15 min. “The pectinase +” isolates were characterized by the presence of a clear halo around colonies [12].

2.2.7. Lipase Activity

Lipase activity was carried out on a culture medium based on olive oil and rhodamine B. This method was based on the emission of fluorescence by the colonies, which was due to the interaction of rhodamine B with the fatty acids released during the enzymatic hydrolysis of the olive oil. The medium consisted of (g/L) NaHPO4 (12 g), KH2PO4 (2 g), MgSO4 7H2O (0.3 g), CaCl2 (0.25 g), (NH4) SO4 (2 g), and pH was adjusted to 7.0. After sterilization, the medium was mixed with olive oil (31.25 mL) and rhodamine B 10 mL (1 mg/mL). Colonies with lipase activity develop a fluorescence after exposure of the Petri dishes to UV radiation (350 nm) [37].

2.2.8. Gelatinase Activity

The detection of gelatinase activity was carried out on a gelatin-based culture medium: (g/L) gelatin (15 g), peptone (4 g), yeast extract (1 g), meat extract (1 g), agar (15 g). While the medium showed an opaque appearance on the proteinaceous substrate, having a clear zone around the colonies indicates the hydrolysis of gelatin substrate [38].

2.2.9. Urease Activity

The medium Christensen was used to reveal urease activity in the yeasts studied. This enzyme converts urea to ammonia, which increases the pH that changes the color indicator. After 2 days of incubation at 30 °C, a pink to violet coloration in the culture media indicated positive results [39].

2.2.10. Protease Activity

Protease production was determined according to the method of Strauss et al. [40] by plating yeast colonies on a medium containing (g/L) yeast extract (0.5 g), NaNO3 (1 g), K2HPO4 (2 g), KCl (1 g), MgSO4 (0.5 g), agar (20 g), and milk powder (10 g). Incubation was carried out at 30 °C for 7 days. The proteolytic activity was revealed by the presence of a clear zone around the colony.

2.2.11. Catalase Activity

The catalase activity was evaluated using the method described by Whittenbury [41] by directly adding 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide to a 48 h yeast culture. Catalase activity was evidenced by the presence of oxygen bubbles.

2.2.12. Tannase Activity

The tannase activity in the different yeast isolates was detected on YPG media supplemented with 10 mL of a tannic acid (20%) solution. The yeasts that have a Tannase activity showed a clear halo, reflecting the decomposition of tannic acid, gallic acid, and glucose.

2.3. Study of Physiological Characteristics of Cellulolytic Isolates

2.3.1. Thermotolerance

The thermotolerance of the isolate temperatures was evaluated on YPG agar and M9-CMC medium, after incubation for 48 h at different temperatures: 30, 37, 40, 42, 44, 46, and 48 °C.

2.3.2. pH Tolerance

The pH tolerance of the isolates was carried out on a YPG agar medium at different pH values: 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h.

2.3.3. Utilization of Carbon Sources

The digestion of carbon sources by these isolates was carried out on a minimal medium of M9 agar supplemented with 1% of each source, CMC [42], cellobiose, cellulose, sorbitol, sucrose, raffinose, maltose, ribose, xylose, galactose, arabinose, fructose, casein, mannitol, lactose, dextrin, glycine, and glycerol. The growth of isolates was noted after incubation at 30 °C for 48 h.

2.3.4. Glucose Tolerance of Yeasts

The growth of the isolates at different glucose concentrations—50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 (g/L)—was evaluated to investigate the yeast’s tolerance. The isolates were incubated on a YPG agar medium, properly supplemented with different concentrations of glucose. Next, the culture plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h.

2.3.5. Tolerance to Ethanol

We tested the isolate’s tolerance for exogenous ethanol on YPG agar medium that was supplemented with different concentrations of ethanol: 1, 5, 6, 8, 10, and 12%. Then, the plate was incubated at 30 °C for 48 h.

2.4. Molecular Identification

Cellulolytic isolates were cultured in test tubes containing 5 mL of YPG medium. Incubation was carried out at 30 °C for 24 h. DNA extraction from yeast isolates was carried out by the classic method [43]. 1.5 mL of yeast suspension were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm, and the pellet was suspended in 200 µL of lysis buffer (2% Triton X-100, 1% SDS, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8). The mixture was placed at −20 °C for 2 min and then at 95 °C for 1 min. This step was repeated twice to create a thermal shock and promote cell bursting. Next, the DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform. The amplification by PCR of the sequence ITS1 (TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG) ITS4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) was carried out according to the method of White et al. [44]. The reaction was carried out in a final volume of 25 µL, containing primers (final concentration 10 pm, each), dNTPs (200 µM final concentration), MgCl2 (1.5 mM final concentration), 10 µL 1× PCR buffer, Taq polymerase (0.5 U), pure H2O, and extracted DNA. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min and 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 45 s, primer annealing at 55 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. A final extension was completed at 72 °C for 10 min. Sanger sequencing was performed at the pastor institute (Casablanca-Morocco) using an ABI PRISM 3130XL Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems. Preliminary identifications were performed based on sequence assembly and by searching in the NCBI ITS RefSeq Fungi database using command line interface.

2.5. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree

ITS sequences from all the isolates were used to perform BLASTN, and the top 5 hits were retrieved to find close relatives to the isolates. Sequences from all isolates were subjected to multiple sequence alignment using MUSCLE v3.8.31 with default parameters. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree v2.1.10 with –nt –gtr parameters. The phylogenetic tree was visualized with ggtree v3.4.0 in RStudio and R v4.2.0.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Distribution of Isolated Yeasts

The yeasts isolated from the gut of coprophagous “Gymnopleurus sturmi” revealed a large load of 79 × 108 CFU/g and 65.24 × 108 CFU/g in June 2015 and 2016, respectively. The ruminant manure contained 16.8 × 106 CFU/g and 11 × 106 CFU /g in 2015 and 2016, respectively (Table 2). In addition, yeast biodiversity was different among the four samples. The collection consists of 96 isolates, of which 57.29% were isolated from gut Gymnopleurus sturmi (GGS) and 42.71% were isolated from the dung of ruminants (DR).

Table 2.

Percentage of isolates screened for cellulase activity.

3.2. Oxidation of Phenolic Substrates

The isolated yeasts were tested to demonstrate their degradation potential of phenolic lignin by-product compounds (pyrogallol and catechol), essential components of the plant cell wall. Results showed (Table 3) that 40% of the isolates from GGS and 41.5% of the isolates from DR were able to degrade these compounds. These yeasts were isolated from media with a high concentration of phenolic products after the degradation of plants rich in ligninolytic products by the mammals and the assimilation of these products by the clean microflora of the dung and the microflora of the coprophages feeding this dung [45]. Indeed, the phenolic compounds are always liable to be degraded by the enzymes produced by microorganisms [46,47,48,49]. Other studies have shown that fungi such as Aspergillus terreus [49] and yeasts such as Candida tropicalis [50] have a great ability to degrade phenolic products.

Table 3.

Percentage of isolates capable of degrading lignin by-products.

3.3. Screening of Cellulolytic Isolates

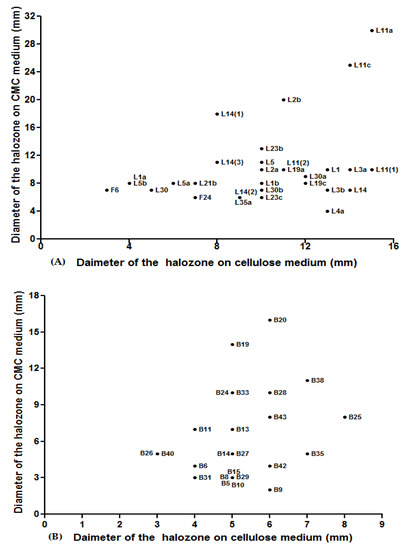

One of the main objectives of this study was to determine the ability of isolated yeasts to produce cellulase enzymes. Therefore, two different substrates (CMC and cellulose fiber) were used for the screening of cellulolytic isolates. Only isolates that showed a positive result in both substrates were considered cellulolytic. This has enabled us to build a library of isolates capable of producing our enzyme of interest from which 30 isolates (54.54%) were collected from GGS and 24 isolates (58.54%) from DR. The degradation time of two substrates varies between isolates (Figure 1A,B). For the GGS isolates, the hydrolysis zone of CMC varied between 6 to 25 mm, and the hydrolysis of the cellulose fiber varied between 3 to 15 mm (Figure 1A). For the DR isolates, the zone of hydrolysis for CMC was noted from 2 to 16 mm and 3 to 7 mm for cellulose fiber (Figure 1B). Thongekkaew and Kongsanthia [18] showed that 45 yeast isolates, obtained from various samples (soil, tree bark, and insect excrement), can hydrolyze cellulose.

Figure 1.

Screening of cellulase activities carried out for the strains isolated (A) from the gut of Gymnopleurus Sturmi (GGS), (B) and from the dung of ruminants (DR).

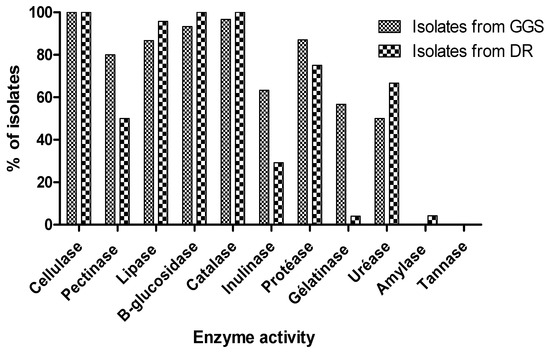

3.4. Hydrolytic Enzymes

Yeasts have the potential to contribute to the development of biotechnological processes with specific applications [51,52]. To characterize the different isolates biochemically, different substrates were tested. The choice of these substrates was related to the composition of the dung [45] and the food requirement of the insect studied [53], which contains a large number of complex substrates. The qualitative tests revealing the production of hydrolytic enzymes in the cellulosic isolates tested made it possible to select efficient isolates. Figure 2 shows that all DR isolates were capable of producing the β-glucosidase and catalase. For GGS, 93.33% of isolates were β-glucosidase-positive and 96.67% were catalase-positive. In addition, the hydrolysis of olive oil by the lipase was noted in 86, 67% of the GGS isolates and 95.83% of the DR isolates. On the other hand, the considerable production of pectinase was detected in 80% GGS isolates and 50% DR isolates. Protease was also more prevalent in 87% of GGS and 75% of DR isolates. In addition, 63.33% of GGS, and 29.17% of DR isolates were positive for Inulinase. Gelatinase synthesis was detected for many of the 56.67% GGS and 4% DR isolates. Most isolates had urease activity, of which 50% were isolated from GGS and 66.67% from DR. Tannase activity was absent in all isolates considered in this study. The amylase activity was present only in one isolate of DR out of a total of 24 isolates, which was 4% (Figure 2). In previous studies, (Table 4) [11,27,40,41,54], the isolated various strains exhibited the ability to produce interesting enzymes, with interesting technological applications (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Qualitative tests of enzymatic activities of yeasts isolated from GGS and DR.

Table 4.

Enzymatic activity of isolated yeast a: Isolates from GGS, b: Isolates from DR, 1: Bautista-G et al. [54], 2: Strauss et al. [40], 3: Lilao et al. [27], 4: Romo-Sánchez et al. [11], 5: Hernandez et al. [41].

3.5. Study of Physiological Characteristics

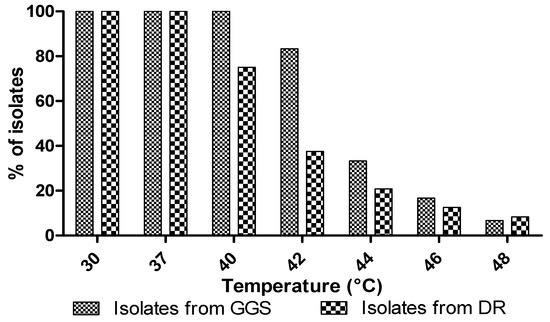

3.5.1. Temperature

The effect of temperature on the yeast growth showed that the growth was stable up to a temperature of 40 °C in GGS isolates and 37 °C for the DR isolates (Figure 3). The percentage of isolates capable of tolerating these temperatures decrease with increasing temperature (Figure 3). Aissam et al. [55] reported an optimum temperature of 37 °C for yeast strains. Babavalian et al. [56] showed that most yeasts isolated from soil cannot withstand a temperature above 37 °C, while complete inhibition of their growth is observed at 45 °C.

Figure 3.

Effect of temperature on the growth of yeast isolates.

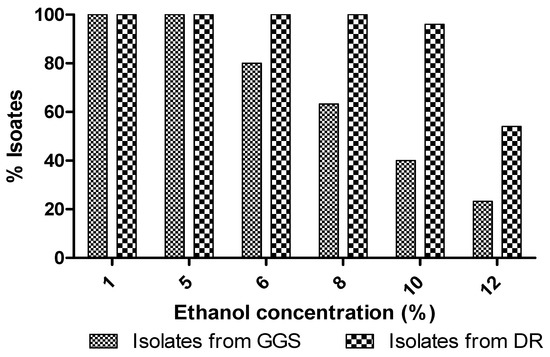

3.5.2. Exogenous Ethanol

All cellulosic isolates from DR were able to support up to 8% of ethanol and 52% of isolates were able to grow in a 12% ethanol culture medium. However, isolates from the GGS only supported a 5% concentration of exogenous ethanol. While increasing the concentration of ethanol, the percentage of these isolates, which grow in the medium, decreases (Figure 4). Arguably, the DR isolates support a higher concentration of ethanol than GGS isolates. This type of behavior has also been observed in strains S. cerevisiae C2 and TA, Saccharomyces cerevisiae K2, Saccharomyces rosinii S1 and S2, Rhodotorula minuta S3, and Saccharomyces exiguus K1 [57].

Figure 4.

Effect of ethanol on the growth of yeast isolates.

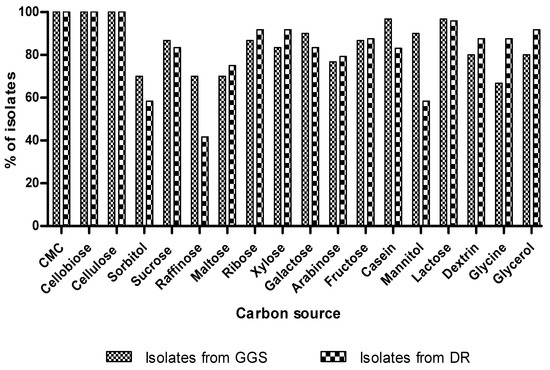

3.5.3. Utilization of Carbon Sources

Figure 5 shows that the yeast isolates (GGS and DR) had a great ability to assimilate several types of carbon sources. These results corroborate with those of Gao et al. [34], who showed that isolated yeasts of marine origin could grow on several sources of carbon.

Figure 5.

The assimilation of different kinds of carbon sources by yeast strains.

3.5.4. Osmotolerance

The osmotolerance test showed that all the isolates of the digestive tract and ruminant dung were osmotolerant and could survive a culture medium with 30% glucose and 10% NaCl (Table 5). In 2005, Milala et al. [58] reported that the sugar tolerance was 20% for the two strains of S. cerevisiae TA and C, 15% for S. cerevisiae MTCC 170, and 10% for the two strains Saccharomyces rosinii S1 and S2, as well as the strain Rhodotorula minuta S3.

Table 5.

Osmotolerance of isolates for glucose and NaCl.

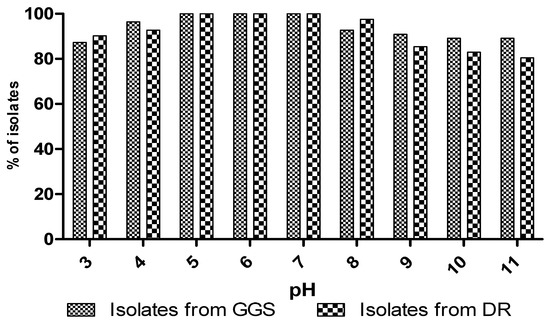

3.5.5. Effect of pH

The effect of pH shows that all isolates were able to grow over a wide range from pH = 5 to pH = 8 (Figure 6), but from a pH equalling 9, the percentage of isolates that could endure the medium decreased. The results showed that cellulosic isolates have interesting technological properties for their application in the course. This species was well-adapted to the environmental conditions that govern fermentations, such as low pH and high concentrations of NaCl [59]. However, in other studies on volcanic yeasts, the optimum pH for growth for all isolates was between 3.5 and 5.5 [60].

Figure 6.

Effect of pH on growth of yeast isolates.

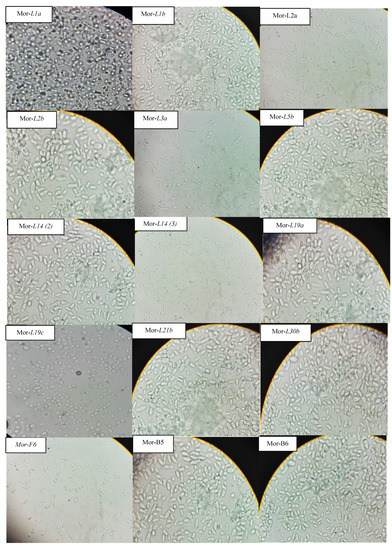

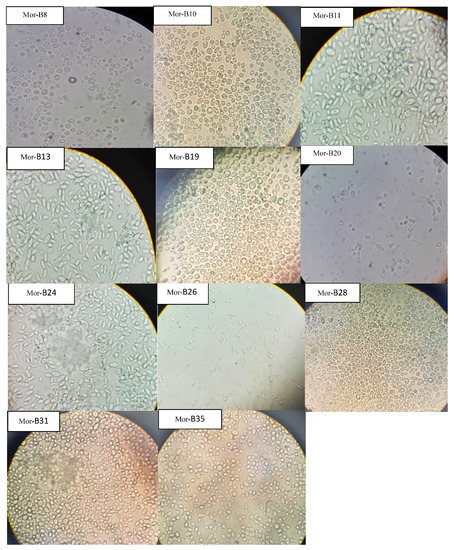

3.6. Molecular Identification

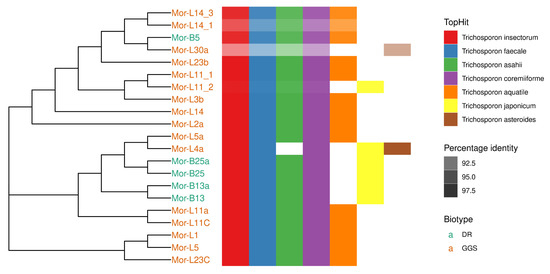

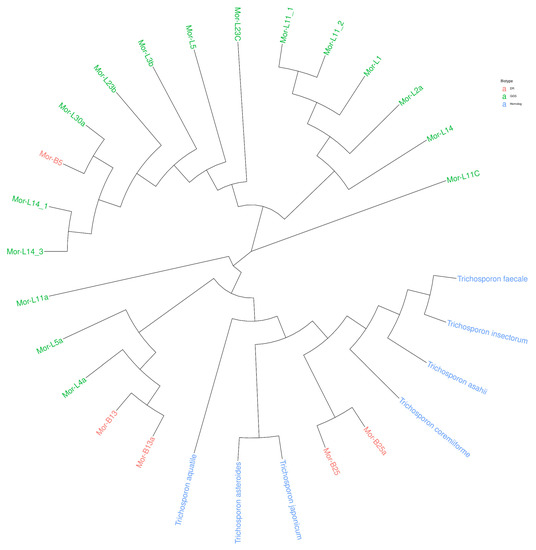

Taxonomic characterization of the 21 cellulosic isolates was carried out after morphological examination under a microscope (Figure 7). The sequence homology search was carried out using the BLASTN algorithm on the command line using ITS RefSeq Fungi database. The latter confirmed that the isolates studied belong to the genus Trichosporon (Table 6). All the identified sequences of strains showed high similarity with Trichosporon insectorum, Trichosporon faecale, and Trichosporon coremiiforme. All except L4a showed a high similarity with Trichosporon asahii. Many of the strains showed high similarity to Trichosporon aquatile. However, biotype DR also had high similarity with Trichosporon japonicum. The top hit of L30a was with Trichosporon coremiiforme with only 90.6% sequence identity. Details of the top 5 hits are shown in Figure 8, along with a phylogenetic tree. In order to understand the phylogenetic relationship of the strains, the sequences of the top hits were combined with the ITS sequences of the strains to build a phylogenetic tree. It is evident that the strains from the biotype DR are more closely related to Trichosporon sp. (top hits of the BLAST) as compared to biotype GGS, except B5, which shares a clade with GGS strains. All the strains were split into 4 clades, while L11C and L11a were different from other clades (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Morphology of different yeast isolates.

Table 6.

Results of yeast identification by rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS).

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic tree and top 5 BLAST hits of all the strains. Darkness of the color increases as the percentage identity increases.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of all the strains with their top BLAST hits.

4. Conclusions

Microbial resources represent natural and real assets. Their exploitation was conducted under rigorous environmental conditions, and the exploitation of their potential was oriented towards targeted biotechnological applications. The gut of coprophagous insects and the dung of ruminants are abundant and culminate an important richness of the yeasts. Purified isolates show interesting enzymatic activities. They are therefore highly desirable biomolecules in the enzyme market, and their quantification and various biotechnological applications are by far the most promising and could be explored in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.H. and M.I.; methodology, T.H.; software, S.A.R.B.; validation, T.H., B.H. and M.I.; formal analysis, B.N.; investigation, T.H.; resources, H.S. and J.I.A.; data curation, B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H. and M.I.; visualization, T.H.; supervision, B.H. and M.I.; project administration, B.H.; funding acquisition, B.H., L.C. and I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by National Center for Scientific and Technical Research, project PPR 2015 Morocco. Scientific Research deanship at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia for their financial support through the Large Research Group Project under grant number (RGP.02-186-43) and National Key R & D Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFD1001002) and the Discipline Construction of Professional Degree (Grant No. 880220039). The role of the funding body in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in the writing the manuscript is management and supervision.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Madden, A.A.; Epps, M.J.; Fukami, T.; Irwin, R.E.; Sheppard, J.; Sorger, D.M.; Dunn, R. The ecology of insect–yeast relationships and its relevance to human industry. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20172733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willaert, R.G. Yeast Biotechnology 4.0. Fermentation 2021, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, T.; Kunze, G. Yeast Biotechnology: Diversity and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chabasse, P.; Bouchara, D.; de Gentile, J.P.; Brun, L.; Cimon, S.; Penn, B. Les Moisissures D’Intérêt Médical. Bioforma 2002, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.-R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, J.-T.; Shim, J.-H.; Park, K.-H.; Kim, J.-W. Screening Wild Yeast Strains for Alcohol Fermentation from Various Fruits Screening Wild Yeast Strains for Alcohol Fermentation from Various Fruits. Mycobiology 2018, 39, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanini, I. Yeast-insect associations: It takes guts Irene. Yeast 2018, 35, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi, R.; Velu, G.; Devi, P.; Dananjeyan, B. Isolation and Screening of Soil Yeasts for Plant Growth Promoting Traits. Madras Agric. J. 2019, 106, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, A.S.; Eisen, B.M. The Ecology of the Drosophila-Yeast Mutualism in Wineries. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Cliff, M.A.; Van Vuuren, H.J.J. Impact of Mixed S. Cerevisiae Strains on the Production of Volatiles and Estimated Sensory pro Fi Les of Chardonnay Wines. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, R.; Nishikawa, R.; Yamada, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Ogino, H. Construction of yeast producing patchoulol by global metabolic engineering strategy. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-sánchez, S.; Alves-baf, M.; Arévalo-villena, M.; Úbeda-iranzo, J.; Briones-pérez, A. Yeast Biodiversity from Oleic Ecosystems: Study of Their Biotechnological Properties. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.K. Cellulases and related enzymes in biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 355–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumaret, J.-P.; Kirk, A. Ecology of dung beetles in the French Mediterranean region (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae). Acta Zool. Mex. 1987, 24, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.-H.; Roh, S.W.; Tae, W.W.; Jung, M.-J.; Kim, M.-S.; Park, D.-S.; Yoon, C.; Nam, Y.-D.; Kim, Y.-J.; Choi, J.-H.; et al. Insect Gut Bacterial Diversity Determined by Environmental Habitat, Diet, Developmental Stage, and Phylogeny of Host. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5254–5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwesh, O.M.; El-Maraghy, S.H.; Abdel-Rahman, H.M.; Zaghloul, R.A. Improvement of paper wastes conversion to bioethanol using novel cellulose degrading fungal isolate. Fuel 2020, 262, 116518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosyidaa, V.T.; Indrianingsiha, W.; Maryanaa, R.; Wahono, S.K. Effect of Temperature and Fermentation Time of Crude Cellulase Production by Trichoderma reesei on Straw Substrate. Energy Procedia 2015, 65, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chi, Z.; Wang, X. A Carboxymethyl Cellulase from a Marine Yeast (Aureobasidium Pullulans 98): Its Purification, Characterization, Gene Cloning and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Digestion. J. Ocean Univ. China 2015, 14, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongekkaew, J.; Kongsanthia, J. Screening and Identification of Cellulase Producing Yeast from Rongkho Forest, Ubon Ratchathani University. Bioeng. Biosci. 2016, 4, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.G.; Borges, M.D.F.; Medina, C.; Hilsdorf Piccoli, R.; Freitas Schwan, R. Pectinolytic Enzymes Secreted by Yeasts from Tropical Fruits. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005, 5, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Conchillo, L.B.; Ruiz, J.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A. Selection and Use of Pectinolytic Yeasts for Improving Clarification and Phenolic Extraction in Winemaking. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 223, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chi, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Production, Purification and Characterization of an Extracellular Lipase from Aureobasidium Pullulans HN2.3 with Potential Application for the Hydrolysis of Edible Oils. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 40, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, G.L.; Xu, J.L.; Chi, Z.M. Purification and Characterization of Extracellular β-Galactosidase from the Psychrotolerant Yeast Guehomyces Pullulans 17-1 Isolated from Sea Sediment in Antarctica. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, S.F.; Nadkarni, G.B. Immobilized catalase-containing yeast cells: Preparation and enzymatic properties. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1980, 22, 2191–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, F.; Zhang, T.; Chi, Z.; Sheng, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Purification and Characterization of Extracellular Inulinase from a Marine Yeast Pichia Guilliermondii and Inulin Hydrolysis by the Purified Inulinase. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2008, 13, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, V.; Kmetzsch, L.; Christian Staats, C.; Vidal-Figueiredo, N.; Ligabue-Braun, R.; Carlini, C.R.; Vainstein, M.H. Cryptococcus gattii urease as a virulence factor and the relevance of enzymatic activity in cryptococcosis pathogenesis. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 1406–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loperena, L.; Soria, V.; Varela, H.; Lupo, S.; Bergalli, A.; Guigou, M.; Pellegrino, A.; Bernardo, A.; Calvino, A.; Rivas, F.; et al. Extracellular Enzymes Produced by Microorganisms Isolated from Maritime Antarctica. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilao, J.; Mateo, J.J.; Maicas, S. Biotechnological Activities from Yeasts Isolated from Olive Oil Mills. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 240, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chi, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, C. Amylase Production by the Marine Yeast Aureobasidium Pullulans N13d. J. Ocean Univ. China 2007, 6, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripwell, R.A.; Rose, S.H.; Viljoen-Bloom, M.; Van Zyl, W.H. Improved Raw Starch Amylase Production by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Using Codon Optimisation Strategies. FEMS Yeast Res. 2019, 19, foy127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.E.; Fathy, S.A.; Rashad, M.M.; Ezz, M.K.; Mohammed, A.T. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Tannase Produced by Kluyveromyces Marxianus Using Olive Pomace as Solid Support, and Its Promising Role in Gallic Acid Production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.A.; Ou, M.S.; Harbrucker, R.; Aldrich, H.C.; Buszko, M.L.; Ingram, L.O.; Shanmugam, K.T. Isolation and Characterization of Acid-Tolerant, Thermophilic Bacteria for Effective Fermentation of Biomass-Derived Sugars to Lactic Acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3228–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, H.R.; Contractor, C.N.; Ghosh, S.K.; Braganza, V.J.A. Comparative Study of Various Staining Techniques for Determination of Extra Cellular Cellulase Activity on Carboxy Methyl Cellulose (CMC) Agar Plates. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Behera, N. Amylase Activity of a Starch Degrading Bacteria Isolated from Soil Receiving Kitchen Wastes. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 3326–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Chi, Z.; Sheng, J.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Gong, F. Inulinase-Producing Marine Yeasts: Evaluation of Their Diversity and Inulin Hydrolysis by Their Crude Enzymes. Microb. Ecol. 2007, 54, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villena, M.A.; Úbeda Iranzo, J.F.; Briones Pérez, A.I. β-Glucosidase Activity in Wine Yeasts: Application in Enology. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2007, 40, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, L.; Zucker, M.; Sands, D.C. Improved Solid Medium for the Detection and Enumeration of Pectolytic Bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. 1971, 22, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Chapadgaonkar, S. Optimization of Lipase Production Medium for a Bacterial Isolate. Int. J. Chem. Technol. Res. 2013, 5, 2837–2843. [Google Scholar]

- Balan, S.S.; Nethaji, R.; Sankar, S.; Jayalakshmi, S. Production of Gelatinase Enzyme from Bacillus Spp Isolated from the Sediment Sample of Porto Novo Coastal Sites. Asia Pacif. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, S1811–S1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geweely, N.S.I. Purification and characterization of intracellular urease enzyme isolated from Rhizopus oryzae. Biotechnology 2006, 5, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Strauss, M.L.A.; Jolly, N.P.; Lambrechts, M.G.; Van Rensburg, P. Screening for the Production of Extracellular Hydrolytic Enzymes by Non-Saccharomyces Wine Yeasts. J. Appl. Microb. 2001, 91, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.; Martin, A.; Aranda, E.; Perez-Nevado, F.; Cordoba, M.G. Identification and characterization of yeast isolated from the elaboration of seasoned green table olives. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanin, M.S.; Mostafa, A.M.; Mwafy, E.A.; Darwesh, O.M. Eco-friendly Cellulose Nano Fibers via First Reported Egyptian Humicola Fuscoatra Egyptia X4: Isolation and Characterization. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2018, 10, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongekkaew, J.; Ikeda, H.; Masaki, K.; Iefuji, H. An acidic and thermostable carboxymethyl cellulase from the yeast Cryptococcus sp. S-2: Purification, characterization and improvement of its recombinant enzyme production by high cell-density fermentation of Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2008, 60, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanin, M.S.; Darwesh, O.M.; Matter, I.A.; El-Saied, H. Isolation and characterization of non-cellulolytic Aspergillus flavus EGYPTA5 exhibiting selective ligninolytic potential. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Scholtz, C.H.; Janeau, J.L.; Grellier, S.; Podwojewski, P. Dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) can improve soil hydrological properties. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 46, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo, G.; Colpa, D.I.; Habib, M.H.M.; Fraaijeb, M.W. Bacterial enzymes involved in lignin degradation. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 236, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínkova, L.; Kotik, M.; Markova, E.; Homolka, L. Biodegradation of phenolic compounds by Basidiomycota and its phenol oxidases: A review. Chemosphere 2016, 149, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsioulpas, A.; Dimou, D.; Iconomou, D.; Aggelis, G. Phenolic removal in olive oil mill wastewater by strains of Pleurotus spp. in respect to their phenol oxidase (laccase) activity. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 84, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido Hoyos, S.E.; Martinez Nieto, L.; Camacho Rubio, F.; Ramos Cormenzana, A. Kinetics of aerobic treatment of olive-mill wastewater (OMW) with Aspergillus terreus. Process Biochem. 2002, 37, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadil, K.; Chahlaoui, A.; Ouahbi, A.; Zaid, A.; Borja, R. Aerobic biodegradation and detoxification of wastewaters from the olive oil industry. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2003, 51, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Liu, G.-l.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Chi, Z.-M. Bio-Products Produced by Marine Yeasts and Their Potential Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 202, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Kumari, R.; Sanjukta, S.; Sahoo, D. Production of Bioactive Protein Hydrolysate Using the Yeasts Isolated from Soft Chhurpi. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 219, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jay-Robert, P.; Errouissi, F.; Lumaret, J.P. Temporal Coexistence of Dung-Dweller and Soil-Digger Dung Beetles (Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidea) in Contrasting Mediterranean Habitats. Bull. Èntomol. Res. 2008, 98, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-gallego, J.; Rodríguez-gómez, F.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A. International Journal of Food Microbiology Exploring the Yeast Biodiversity of Green Table Olive Industrial Fermentations for Technological Applications. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 147, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissam, H.; Errachidi, F.; Merzouki, M.; Benlemlih, M. Identification of the yeasts isolated from the Olive Mill Wastewater and study of catalase activity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2002, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babavalian, H.; Ali Amoozegar, M.; Zahraei, S.; Rohban, R.; Shakeri, F.; Mehrdad Moosazadeh, M. Comparison of Bacterial Biodiversity and Enzyme Production in Three Hypersaline Lakes; Urmia, Howz-Soltan and Aran-Bidgol. Indian J. Microbiol. 2014, 54, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.N.; Khan, M.M. Screening, Identification and Characterization of Alcohol Tolerant Potential Bioethanol Producing yeasts. Curr. Res. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 2, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Milala, M.; Shugaba, A.; Gidado, A.; Ene, A.; Wafar, J. Studies on the Use of Agricultural Wastes for Cellulase Enzyme Production by Aspegillus Niger. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2005, 1, 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo, F.N.; Durán-Quintana, M.C.; Garrido-Fernández, A. Evaluation of primary models to describe the growth of Pichia anomala and study by response surface methodology of the effects of temperature, NaCl and pH on its biological parameters. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, G.; Libkind, D.; Sampaio, J.P.; Van Broock, M.R. Yeast Diversity in the Acidic Rio Agrio-Lake Caviahue Volcanic Environment (Patagonia, Argentina). FEMS Microb. Ecol. 2008, 65, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).