Abstract

This study probabilistically assesses magma ascent by modeling dike propagation as a fully coupled fluid-flow, thermo-mechanical problem, explicitly accounting for the stochastic heterogeneity of the crustal host rock. We study felsic (rhyolite) lava flow and two distinct basaltic feeding regimes that correspond to the conditions necessary to produce the contrasting pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā surface morphologies. Basaltic dikes demonstrate high propagation efficiency to the surface (pāhoehoe-feeding regime 99.5%; ʻaʻā-feeding regime 97.5%), whereas rhyolite dikes have an 89% failure rate, attributed to significant friction. Both regimes represent distinct constructal approaches aimed at maximizing flow persistence. The pāhoehoe-feeding regime is a thermally regulated, stable design characterized by low-velocity, cooling-dominated dynamics. Its slow, persistent flow allows for significant conductive heating of the surrounding rock wall, creating an efficient, pre-heated thermal conduit. In contrast, the ʻaʻā-feeding regime is a mechanically dominated design governed by high-velocity, stochastic dynamics. This morphology is driven by forceful flow, and its thermal budget is supplemented by intense viscous dissipation (internal friction). Rhyolite magma flow fails upon losing constructal viability, driven by a coupled mechanical–thermal cascade. The sequence begins when a mechanical barrier halts the magma velocity, which triggers a freezing event and leads to permanent arrest.

1. Introduction

Magma transport is fundamental because it governs the efficient transfer of heat and mass from the planetary interior to the surface, a process essential for volcanism, crustal accretion, and long-term lithospheric evolution [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Thus, the flow of magma from its source to the surface is a fundamental process in planetary geodynamics. This transport is dominated by the propagation of dikes, which are magma-filled fractures that must navigate the complex thermal and mechanical environment of the lithosphere [3,4,5,6,7]. Modeling this process is exceptionally challenging, as it requires coupling the physics of solid mechanics, fluid dynamics, and thermodynamics [5,6]. Models for dike propagation treated these components in isolation. The mechanical problem was treated using linear elastic fracture mechanics, defining propagation as a competition between magma-driving pressure and the host rock’s fracture toughness [5,6]. This process is critically influenced by the in situ ambient stress field, which dictates dike orientation and arrest potential [7]. In parallel, fluid models calculated the viscous pressure gradient required for flow [4,5,6,8], while thermal models addressed the conductive cooling and freezing [2]. The primary limitation of these models is their failure to predict arrest outcome for a magmatic dike. Dikes fail because these systems are intimately coupled.

Magma transport is governed by the multi-phase equation of state of the magma itself. Magma is not a simple liquid but a three-phase mixture whose properties, including viscosity, are emergent functions of pressure, temperature, and composition [3,8,9,10,11,12]. Viscosity is fundamentally controlled by the silicate liquid structure, the rheological impact of suspended crystals, and the complex behavior of exsolved gas bubbles [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Volatile exsolution, in particular, acts as the engine of explosive eruptions. This coupled system creates a self-accelerating process (viscosity catastrophe) where initial cooling increases magma viscosity, which in turn increases friction, slows the flow, and thus accelerates further conductive cooling, leading inevitably to permanent dike arrest [5,6]. This thermo-fluid coupling is compounded by mechano-fluid coupling, as the dike’s width is not fixed but is an evolved property of the balance between magma pressure and host rock rigidity [5,6].

The magma types analyzed in this study (basalt and rhyolite) represent end-members of volcanic behavior. Basaltic magmas are typically low-viscosity, high-temperature flows, leading to effusive eruptions [3]. It is critical to note that the terms pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā lava morphologies specifically refer to the macro-scale surface texture or final morphology of the solidified lava flow. Crucially, these surface morphologies are the frozen manifestation of two distinct, transient rheological flow regimes that existed during the active emplacement of the lava. The pāhoehoe-feeding regime is a thermally regulated, stable design characterized by low-velocity, cooling-dominated dynamics, creating an efficient, pre-heated thermal conduit. The ʻaʻā-feeding regime, conversely, is a mechanically dominated design governed by high-velocity, stochastic dynamics, supplementing its thermal budget via intense viscous dissipation. Rhyolite is a high-viscosity, lower-temperature felsic magma, inherently prone to freezing and responsible for the most explosive eruptions due to its high silica content and ability to trap volatiles [11,12].

This study presents a stochastic approach to model magma flow, utilizing a Monte Carlo simulation framework to solve the problem of dike propagation as a fully coupled system of fluid-flow and thermo-mechanical equations. By treating key crustal parameters, such as fracture toughness, rigidity, and stress, as spatially correlated random fields, the model explicitly accounts for the stochastic heterogeneity of the host rock. The probabilistic assessment is performed on three distinct lava typologies: basaltic (specifically pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā morphology regimes) and felsic (rhyolite). The aim is to advance beyond deterministic, binary outcomes by quantifying the eruption probability distributions and flow dynamics associated with these different magma types.

2. Materials and Methods

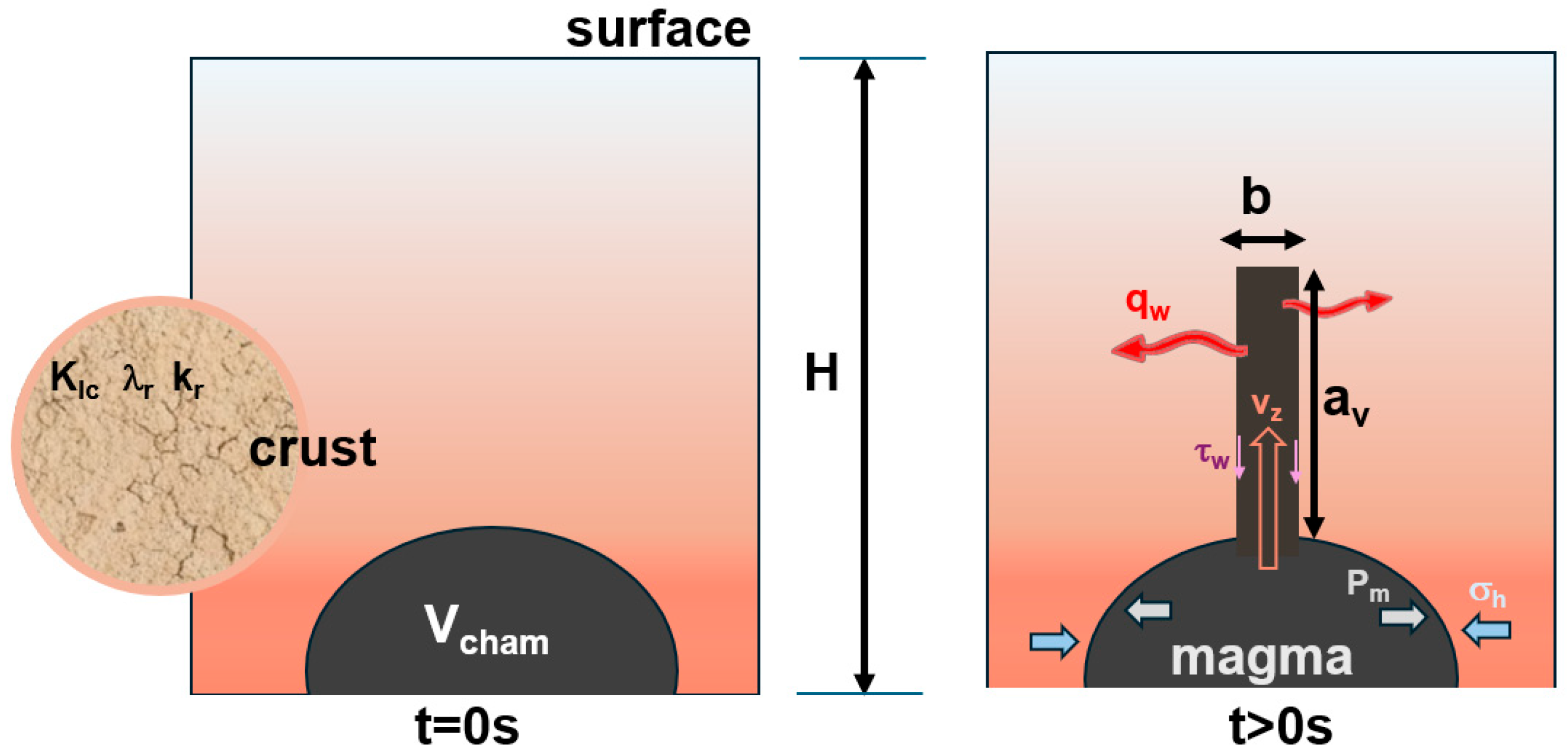

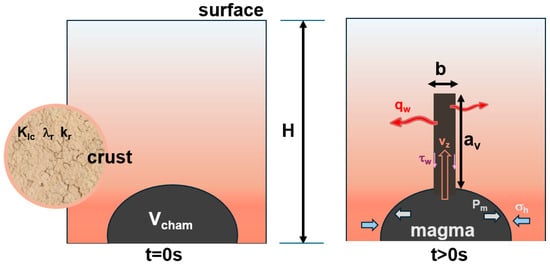

Consider the problem of magma ascending from a chamber to a bifurcation point, where it can follow two principal paths: the vertical path toward an eruption (dike propagation) or the horizontal path to form an intrusion (specifically, a sill). The magma that does not reach the surface is emplaced into the crust as an intrusion. Intrusions occur in various forms, including dikes (magma-filled fractures that cut across existing layers) and sills (horizontal magma bodies emplaced parallel to rock layering) [1,2,5,6]. Our approach is described by three components, the solid (rock), the fluid (magma and gas), and the interface between them, and is specifically formulated to analyze the flows along the vertical path. This path is aided by the magma, and to succeed, the magma must overcome gravity and continuously fracture the rock at its tip (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the dike propagation model: the initial state (t = 0 s), showing a magma chamber (Vcham), and the crust as a heterogeneous medium (fracture toughness (KIc), rigidity (λr), thermal conductivity (kr)), and the propagation state (t > 0 s) where magma ascends from the chamber, and at this junction, it can follow a horizontal path (intrusion, dotted line), and a vertical path (eruption).

Our model assumes that the crust is a heterogeneous medium, where mechanical properties are not constant but spatially random fields. This stochastic nature is the critical mechanism that allows the model to simulate vertical arrest for any lava type. Arrest occurs when the dike tip randomly encounters a rock barrier that is stronger than the magma-driving pressure, causing the propagation velocity to drop to zero.

- -

- Continuity Equation

The change in mass within the dike is due to inflow/outflow and the opening/closing of its walls:

where ρm is the mixture density (liquid and bubbles), b is the dike width at height (obtained from Equation (5)), z is the vertical spatial coordinate along the direction of magma ascent, vz is the magma ascent velocity, t is time, and w is the horizontal depth.

- -

- Momentum Equation

The pressure and flow balance is [14]

where Pm is the pressure, g is the acceleration of gravity, and τm is the shear stress at the wall (friction).

- -

- Energy Equation

Assuming that magma temperature changes due to advection, wall heat loss, friction, and crystallization,

where Tm is the magma temperature, CP is the magma heat capacity, Φvisc is the frictional heating, Slat is the latent heat from crystallization, and qw is the heat flux from magma to wall (coupling term).

- -

- Rock Heat Balance

The heat loss qw is governed by how fast the surrounding rock absorbs heat. Assuming a heat conduction outward from the dike,

where Tr is the rock temperature, ρr is the rock density, Cr is the rock heat capacity, and kr is the rock thermal conductivity.

- -

- Elastic Fracture Mechanics

The dike width b is dictated by magma pressure, which forces the rock with stiffness λr to open against the confining stress σh of the rock [1,7]:

where av is the total height of the dike tip (Equation (7)), and ν is the Poisson ratio.

- -

- Chamber drainage (source equation)

The pressure at the dike base, which is the source of magma flow, decreases as the magma chamber empties and

where Km is the bulk modulus of the magma, Vcham is the volume of the magma chamber, and Qtotal is the total flow rate of the magma that is ascending from the chamber and arriving at the bifurcation point. The pressure at the dike base, Psour, is the source of magma flow, which decreases as the chamber empties.

- -

- Propagation equation

The ascent velocity of the dike tip depends on the force balance at the tip. According to fracture mechanics [5,6],

where Cv is a propagation constant, σh is the lithostatic stress, Kl is the magma force calculated from pressure along the dike, and KIc is the rock toughness, which decreases as the tip heats up (Equation (4)).

- -

- State equations

According to the model of Giordano et al. [8], the viscosity of magma is given by

where ηm is the magma viscosity, ηl is the liquid viscosity, and ηr,θ and ηr,ϕ are the contributions of the effects of crystal fraction and bubble fraction, respectively. The density of magma is given by

where ρm is the magma density, ρli is the liquid density, ρg is the gas density obtained from the Redlich–Kwong equation [15], and ϕ is the bubble fraction obtained based on the Gonnermann and Manga [16] model.

Stochastic models offer a significant advantage over their deterministic counterparts by fundamentally incorporating the inherent heterogeneity and uncertainty present in natural geophysical systems [17]. While the previous approach relies on averaged, homogeneous material properties, a stochastic framework is required for a realistic model. This analysis, therefore, transitions to a stochastic view that acknowledges that crucial parameters, such as rock rigidity, local stress fields, and thermal conductivity, are spatially variable fields. Within this framework, the governing equations are modified to capture the crust’s micro-heterogeneity; specifically, Equations (4) and (5) are altered by treating the rock’s thermal properties (kr, Cr) and mechanical properties (λr, σh) as spatial random fields.

where εk and εC account for the non-uniformity of rock structure, and ελ and εσ account for variations in rock stiffness and the heterogeneity of local stress, respectively.

Equation (6) is transformed into a stochastic differential equation by incorporating a noise term (ξP) to represent unstable pressure fluctuations in the magma chamber

Equation (7) redefines the rock’s fracture toughness (KIc) as a random field.

where εK is a random field representing the distribution of faults and weaknesses in the rock.

Equation (8) introduces stochasticity directly into the bubble nucleation controlling the gas fraction (εϕ(z,t)), which is now a random field.

The remaining equations retain their fundamental forms as conservation laws. However, they become stochastic because their input variables are now random fields determined by the aforementioned stochastic equations. Next, Equations (1)–(8) will be rewritten in a dimensionless form, fully incorporating the stochastic character outlined above. To non-dimensionalize, a set of reference scales to normalize each variable is selected, and new variables are defined as

where H is the total depth of the crust, and the subscript 0 means quantity at the source.

Substitution of Equation (10) into Equations (1)–(8a,b) yields

- -

- Continuity Equation

- -

- Momentum Equationwith

- -

- Energy Equationwithwhere Br is the Brinkman number, is a heat loss number, is a friction number that represents the ratio between viscous friction forces and gravitation forces (the weight of the magma). It is worth noting that the friction number determines the significance of stochastic fluctuations. When the friction number is much greater than 1, the pressure gradient is dominated by the friction term. In this regime, stochastic variations in viscosity or channel width can have a substantial impact on pressure. Conversely, when the friction number is much less than 1, the pressure gradient is primarily governed by gravity. In this case, fluctuations in viscosity are nearly negligible.

Regarding the Brinkman number, if it is much greater than 1, friction heats the magma faster than it cools, resulting in acceleration. It is important to note that stochastic fluctuations in ηm* (from εη*) are scaled by this number, making them highly impactful. Regarding the heat loss number, when it is much greater than 1, the magma cools and solidifies rapidly. Stochastic fluctuations in kr (from εk*) are captured in qw* and amplified by this number.

- -

- Rock Heat Balancewithwhere is a diffusion number that represents the ratio between the advective time scale and the diffusion time scale.

- -

- Elastic Fracture Mechanicswithwhere is a dimensionless number that represents the ratio between the pressure forces and the elastic forces. Note that a very stiff rock zone (λr* > 1) will induce a constriction, leading to a reduction in b*. Conversely, a region subjected to high compressive stress (σh* > Pm*) may cause b* to collapse entirely.

- -

- Chamber drainage (source equation)with

- -

- Propagation equationwithwhere Np is the dimensionless number of propagation defined by the ratio between the velocity of fracture and the magma velocity, and dav*/dt* is non-negative as the dike cannot retreat.

- -

- State equationswhere densities are non-dimensionalized relative to ρliq.

The model specifically analyzes a felsic (rhyolite) lava, and two distinct basaltic flow regimes corresponding to the initial conditions required to generate pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā surface morphologies upon eruption (i.e., two regimes defined by distinct driving mechanisms: the pāhoehoe-feeding regime, characterized by a low initial source pressure and a low reference velocity, and the ʻaʻā-feeding regime, characterized by a high initial source pressure and a high reference velocity). These distinctions in initial flow regimes and driving conditions are crucial for modeling the subsequent coupled thermal and mechanical feedback within the dike.

Solving the system of non-linear stochastic differential equations (Equations (11)–(18)) necessitated the adoption of a Monte Carlo framework, which is used to propagate the input uncertainties through the model to quantify the uncertainty in the final results, in order to account for the inherent heterogeneity and uncertainty of the system. This approach was essential because critical parameters, such as rock toughness, rigidity, and thermal conductivity, were implemented as spatially correlated random fields. The computational implementation was carried out in Python (version 3.14.0). To establish a statistically robust ensemble, the simulation was executed 200 times, with each run using an independent realization of the random fields. The implementation leveraged the parallel processing capabilities of a workstation (Intel Core Ultra 7 165H vPro processor with 32 GB RAM) to execute these 200 independent realizations concurrently.

To solve the coupled systems equations (Equations (11)–(18)), the initial conditions and boundary conditions along the dike and in the host rock must be defined. Regarding the initial conditions, the entire host rock is assumed to be in thermal equilibrium, the magma chamber is at initial pressure Psour, and magma within the source is at the initial magma temperature. Regarding the magma domain boundary conditions, the Dirichlet condition is applied for pressure (i.e., the pressure at the dike is due to the time-dependent pressure in the magma chamber) and temperature (i.e., magma entering the dike is assumed to have the constant temperature of the chamber). For fracture, the tip is considered a free boundary whose velocity is not prescribed but solved for using the fracture propagation (Equation (17)). Regarding the thermal domain, for the dike–rock interface, a Neumann condition is applied to the heat flux

and a Dirichlet condition is applied to far-field rock for temperature (i.e., the rock remains unperturbed by the magmatic heat and is fixed at the initial geothermal temperature for that depth).

3. Results

Next, we present the results of the simulation of the ascent of magma through a crust and evaluate whether it leads to a volcanic eruption or results in the arrest or solidification of the propagating dike. Basaltic and felsic lavas are considered in the simulations: two basaltic lava regimes [2,8,9,10,16,18], pāhoehoe (T0 = 1200 °C, ρ0 = 2700 kg/m3, η0 = 102 Pa s, Cp0 = 1300 J/kg K, Km = 15 GPa, average total gas 1.25%, v0 = 0.1 m/s, Psour* = 1.5) and ʻaʻā (T0 = 1200 °C, ρ0 = 2700 kg/m3, η0 = 102 Pa s, Cp0 = 1300 J/kg K, Km = 15 GPa, average total gas 1.25%, v0 = 0.5 m/s, Psour* = 3.0), and as the felsic lava, the rhyolite (T0 = 850 °C, ρ0 = 2300 kg/m3, η0 = 107 Pa s, Cp0 = 1450 J/kg K, Km = 3 GPa, average total gas 6.0%, v0 = 0.02 m/s, Psour* = 5.0). The chamber volume is 10 km3, external surface temperature is 15 °C, and geothermal gradient (ambient) is 0.025 K/m [2]. The choice of these initial conditions, particularly the contrasting viscosities and initial chamber pressures, is derived from standard petrological models and field constraints consistent with the literature. Specifically, the viscosity model and the crystal fraction contribution, which strongly govern magma rheology, are key to establishing these initial conditions. The deterministic crustal properties and the stochastic field parameters are detailed, along with their primary references, in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Deterministic parameters for geometry and crust properties.

Table 2.

Stochastic parameters for geometry and crust properties.

3.1. Probabilistic Assessment of Eruption Hazard

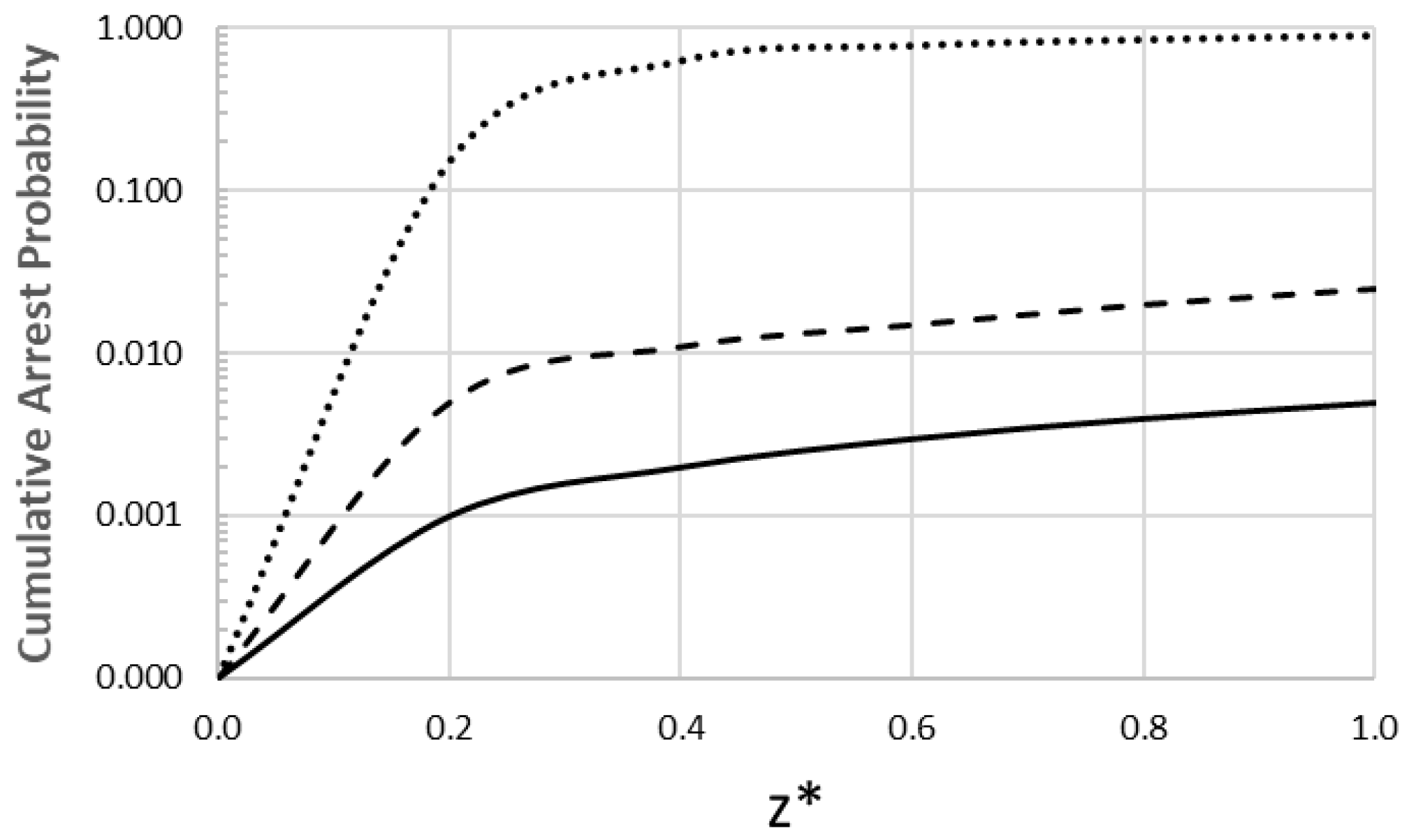

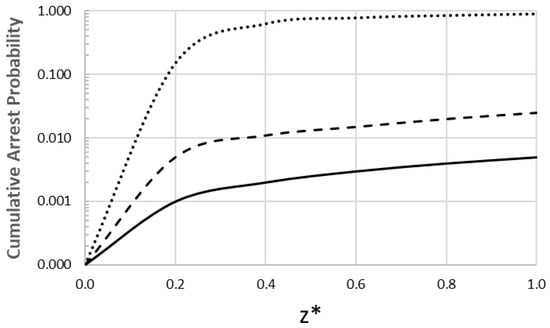

Figure 2 shows the statistical result of 200 runs of Monte Carlo simulations for the pāhoehoe, ʻaʻā, and rhyolite regime scenarios, showing the cumulative probability that a propagating dike will arrest (stop) as it ascends from its source (z* = 0.0) to the surface (z* = 1.0).

Figure 2.

Cumulative arrest probability versus the dimensionless height (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava).

Figure 2 shows an important contrast in eruption probability, clearly separating the highly efficient basaltic lavas from the rhyolitic magma. Notice that both the pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā basaltic feeding regimes begin with the same low initial viscosity. Their driving conditions are different, where the pāhoehoe-feeding dike represents a stable, low-pressure, and low-velocity system, whereas the ʻaʻā-feeding dike is a high-effusion-rate event, transforming the magma into the characteristic, higher-viscosity ʻaʻā-feeding regime. This difference directly impacts their success. The pāhoehoe-feeding regime is nearly immune to stochastic noise, and random rock barriers are too weak to stop the flow. The total failure probability is 0.5%, resulting in a 99.5% probability of eruption success. The ʻaʻā-feeding regime has a very low failure probability of 2.5%. While still highly likely to erupt, this failure rate is noticeably higher than the near-guaranteed success of the pahoehoe-feeding scenario (0.5%). On the other hand, the high-viscosity rhyolite lava demonstrates an extremely high failure probability of 89%. This magma is fighting extreme friction. It is remarkable to notice that most rhyolitic dikes (~65%) fail to even pass the z* = 0.6 level, failing mechanically or freezing in a thermal death spiral before they can reach the surface. This leaves only an 11% chance of a successful eruption.

To complement the spatial arrest probability (Figure 2), the probability distribution of the time-to-eruption (PDTE) is used. This quantity allows us to obtain the required insight about when the eruption arrives in the case of an eruption that does happen. The results are obtained from the sub-population of simulations that successfully erupted (i.e., av = 1) from the 200-run Monte Carlo ensemble. The results are presented in terms of mean PDTE that represents the average waiting time for the eruption (i.e., in the simulations, some would erupt quickly and some slowly), and the standard deviation of PDTE (i.e., measuring the variability of the arrival time; a low standard deviation means the arrival time is highly predictable, while a high standard deviation means the travel time is difficult to forecast). For pahoehoe-feeding regime simulations, 199 (out of 200) resulted in a successful eruption (99.5% probability of success). For this group, the arrival time was highly predictable, with a mean PDTE of 3.6 and a low standard deviation of PDTE of 0.2. This means a stable and efficient low-viscosity flow. The stochastic noise from rock barriers has almost no impact on its reliable travel time. In the case of the ʻaʻā-feeding regime, there are 195 successful runs (97.5% eruption probability). The eruption was, on average, faster than the pahoehoe-feeding regime, with a mean PDTE of 2.0, but it is less predictable, with a standard deviation of PDTE of 0.8. Some runs are slowed by random barriers, while others arrive very quickly, making the exact timing highly uncertain. For the rhyolite lava scenario, the system is critical because only 18 (out of 200) simulations resulted in an eruption. For these few successful runs, the arrival time was exceptionally long and extremely variable, with a mean PDTE of 11.5 and a very high standard deviation of 3.5. This means that the final arrival time of the few eruptions is entirely dependent on the specific random path the dike happens to find.

3.2. Transient System Dynamics

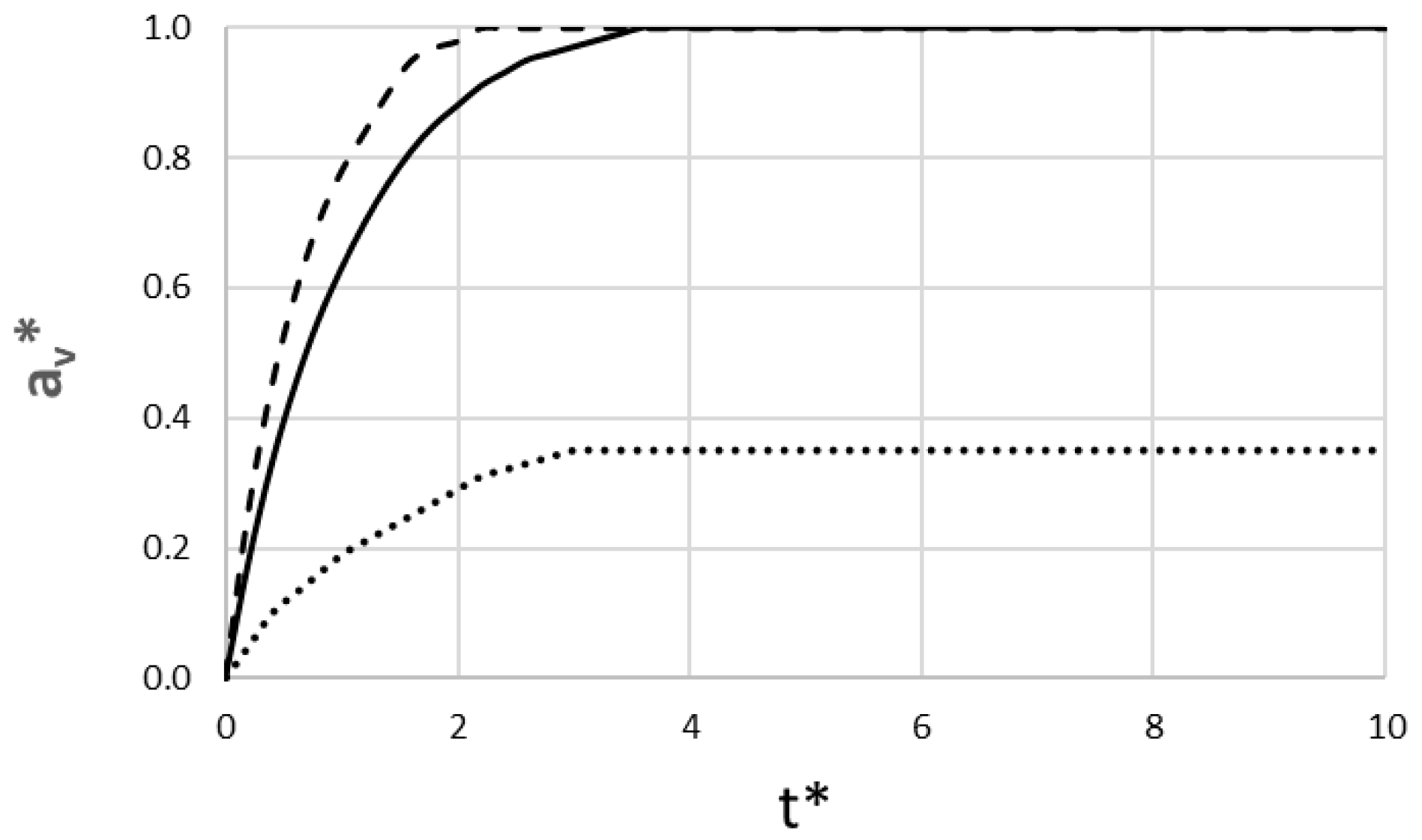

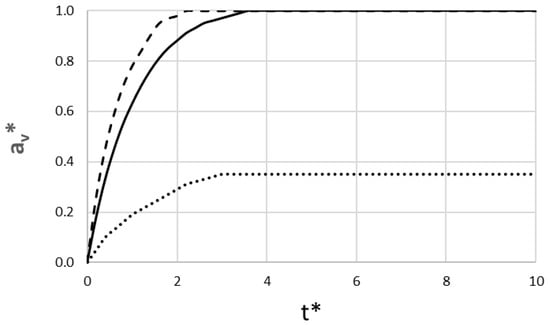

Figure 3 shows the non-dimensional dike tip position as a function of non-dimensional time. A successful eruption is recorded when the tip reaches the surface (av* = 1).

Figure 3.

Non-dimensional dike tip position versus dimensionless time (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava). The dimensional time corresponding to t* is highly dependent on the lava type’s reference velocity (v0).

The results in Figure 3 show a clear distinction between the basaltic and rhyolitic scenarios. Both basaltic runs are highly successful, reaching the surface, but their dynamics differ significantly. The ʻaʻā-feeding regime scenario is much faster, erupting at t*~1.8, which corresponds to a dimensional time of approximately 10 h. In contrast, the pāhoehoe-feeding regime scenario takes twice as long, erupting at t*~3.6, equivalent to approximately 4.2 days. The rhyolite ensemble, in contrast, illustrates the critical bifurcation outcome that is central to the stochastic model. This run represents a failed eruption that freezes to become an intrusion, which represents the statistically common outcome. The dike tip advances slowly until t*~3.0 (approximately 17.4 days), at which point it hits a stochastic barrier and stalls permanently at a dimensionless height of ~0.35.

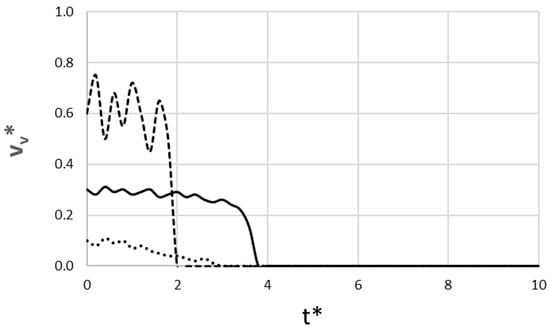

The non-dimensional instantaneous velocity at which the dike tip fractures the rock is depicted in Figure 4. It directly explains the dynamics seen in Figure 3. The basaltic lava shows two distinct successful behaviors. It is important to clarify that our analysis focuses on the dike propagation velocity and source effusion rate, not the velocity of the final surface flow. While pāhoehoe surface flows are typically observed to be faster than ʻaʻā flows [21], our results demonstrate that the high-pressure, high-velocity ʻaʻā-feeding dike fractures the crust faster, resulting in a quicker eruption time.

Figure 4.

Non-dimensional dike tip velocity versus dimensionless time (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava).

The pāhoehoe-feeding run is characterized by a stable velocity, fluctuating gently around an average of ~0.28. This represents a steady, low-noise flow that is not strongly perturbed by the stochastic rock properties. In contrast, the ʻaʻā-feeding run has a higher average velocity (~0.6) with significant fluctuation (e.g., from 0.75 down to 0.50). This behavior means the dike forcefully breaks through stochastic barriers, allowing it to erupt much faster. For the rhyolite run, the statistically common outcome shows an extremely low and fluctuating velocity that slows over time. At t*~3.0, it hits an insurmountable barrier, causing the velocity to drop permanently to 0 and the dike to stop.

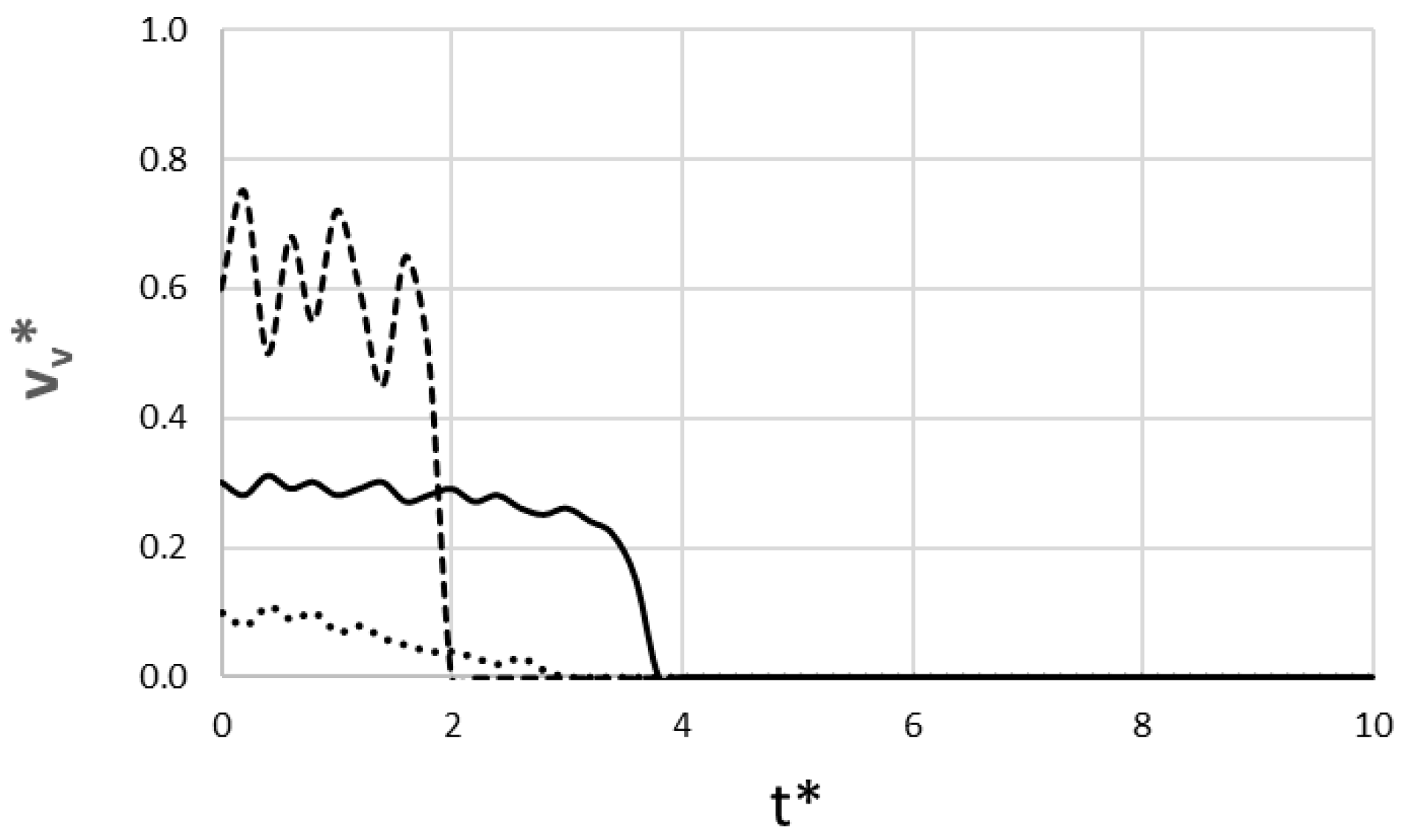

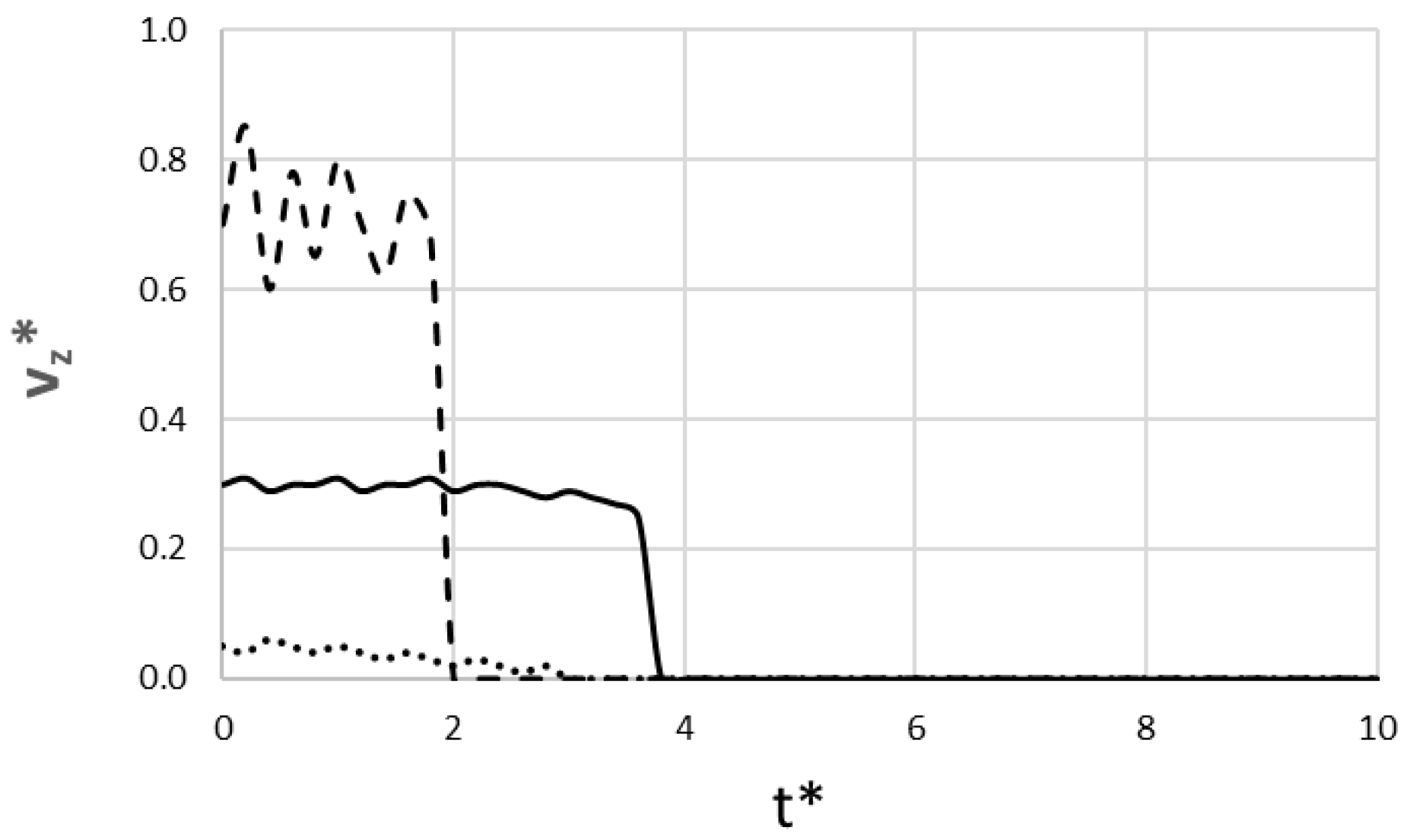

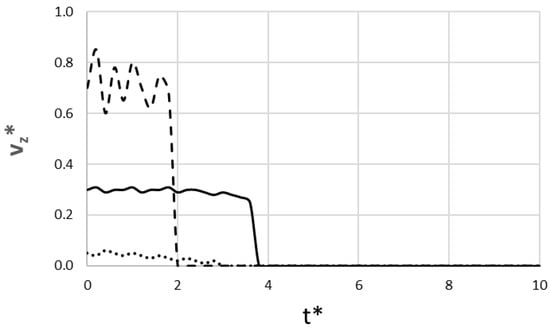

Figure 5 shows the change in non-dimensional magma velocity at the source, which represents the so-called effusion rate or how fast magma is being drawn from the chamber. The pahoehoe-feeding scenario shows a low (~0.3) and very stable source velocity, reflecting a steady, low-noise flow. In contrast, the ʻaʻā-feeding scenario is characterized by a high average velocity (~0.7) with high fluctuations, representing a forceful, chaotic surge from the chamber. Both basaltic runs drop to zero only after their respective eruptions are complete. The rhyolite scenario shows a very low source velocity and drops permanently to zero at t* = 3.0. Notice that magma velocity drives the dike tip velocity shown in Figure 4. For the basaltic lavas, this behavior is coupled; the stable source flow of the pāhoehoe-feeding scenario causes its stable tip velocity, while the erratic source flow of the ʻaʻā-feeding scenario causes its forceful tip velocity. Regarding the rhyolite, it shows the opposite. The dike tip velocity drops to zero first (t*~3.0) because it hits a mechanical rock barrier. This blocks the tip and then causes the magma velocity to drop to zero as the entire flow system stops.

Figure 5.

Non-dimensional magma velocity at source versus dimensionless time (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava).

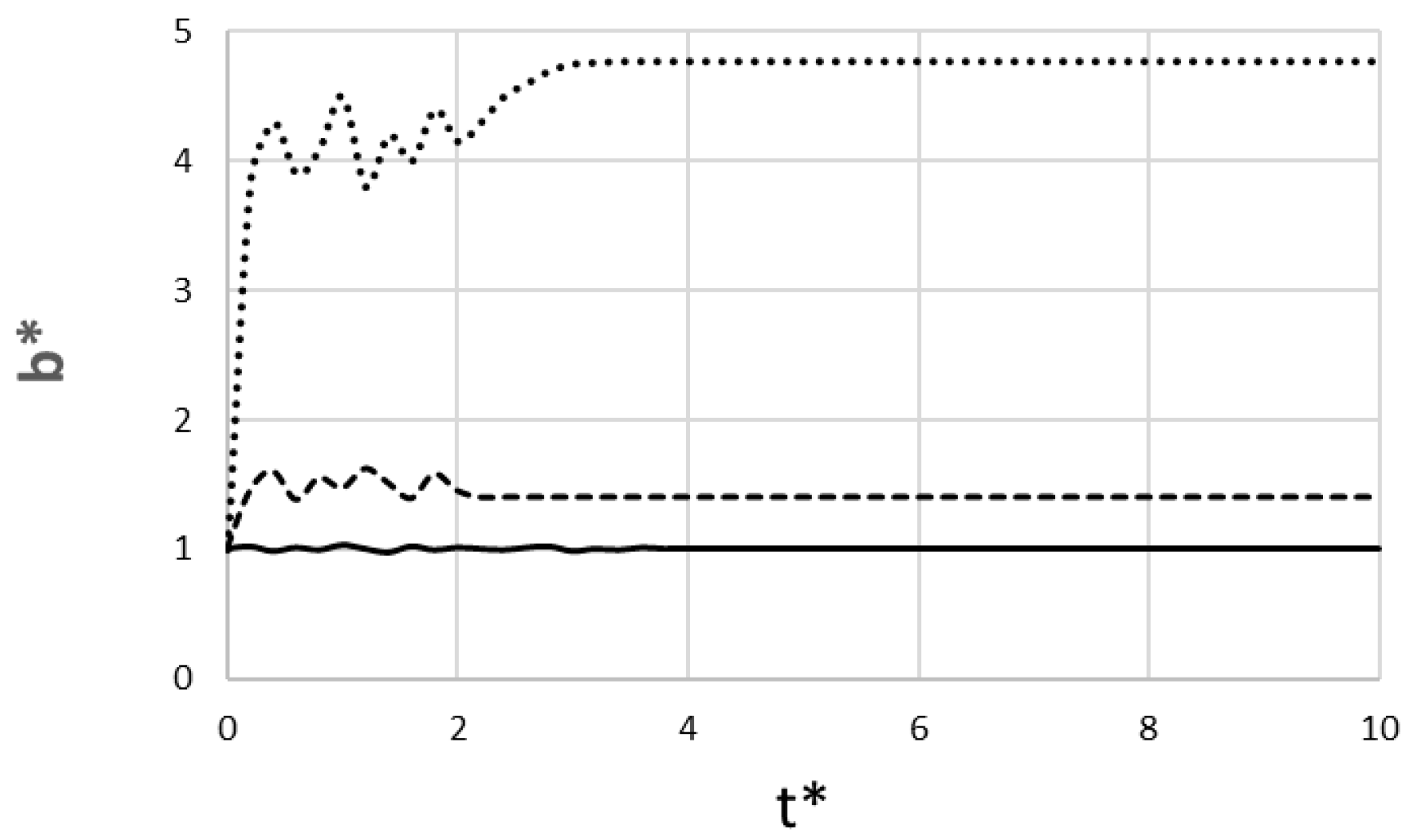

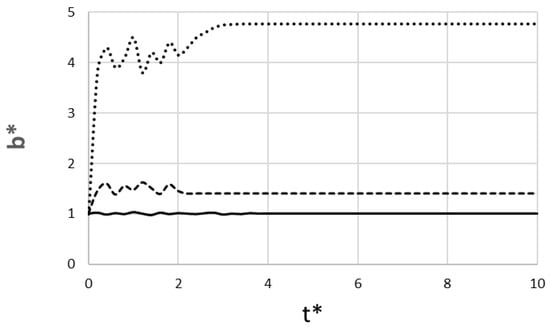

Figure 6 shows the non-dimensional dike width at the source, which is linked to the magma pressure required at the dike’s inlet (i.e., a wider dike implies a higher pressure is needed to overcome the friction and the rock’s random rigidity). According to this figure, the pāhoehoe-feeding scenario shows a width that is very stable, fluctuating gently around the baseline of b*~1.0. This reflects a low, steady driving pressure that is insensitive to the random stochastic properties of the rock. In stark contrast, the ʻaʻā-feeding scenario requires a higher average pressure to maintain its forceful flow, resulting in a wider average dike (b*~1.5). Its width fluctuates very much up to t*~2), showing a high sensitivity to the random rock properties before it erupts and stabilizes. The rhyolite scenario demonstrates the extreme pressures needed to fight enormous friction. It also shows a very wide and highly fluctuating profile, reflecting extreme sensitivity to random rock rigidity.

Figure 6.

Non-dimensional dike width at the source versus dimensionless time (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava).

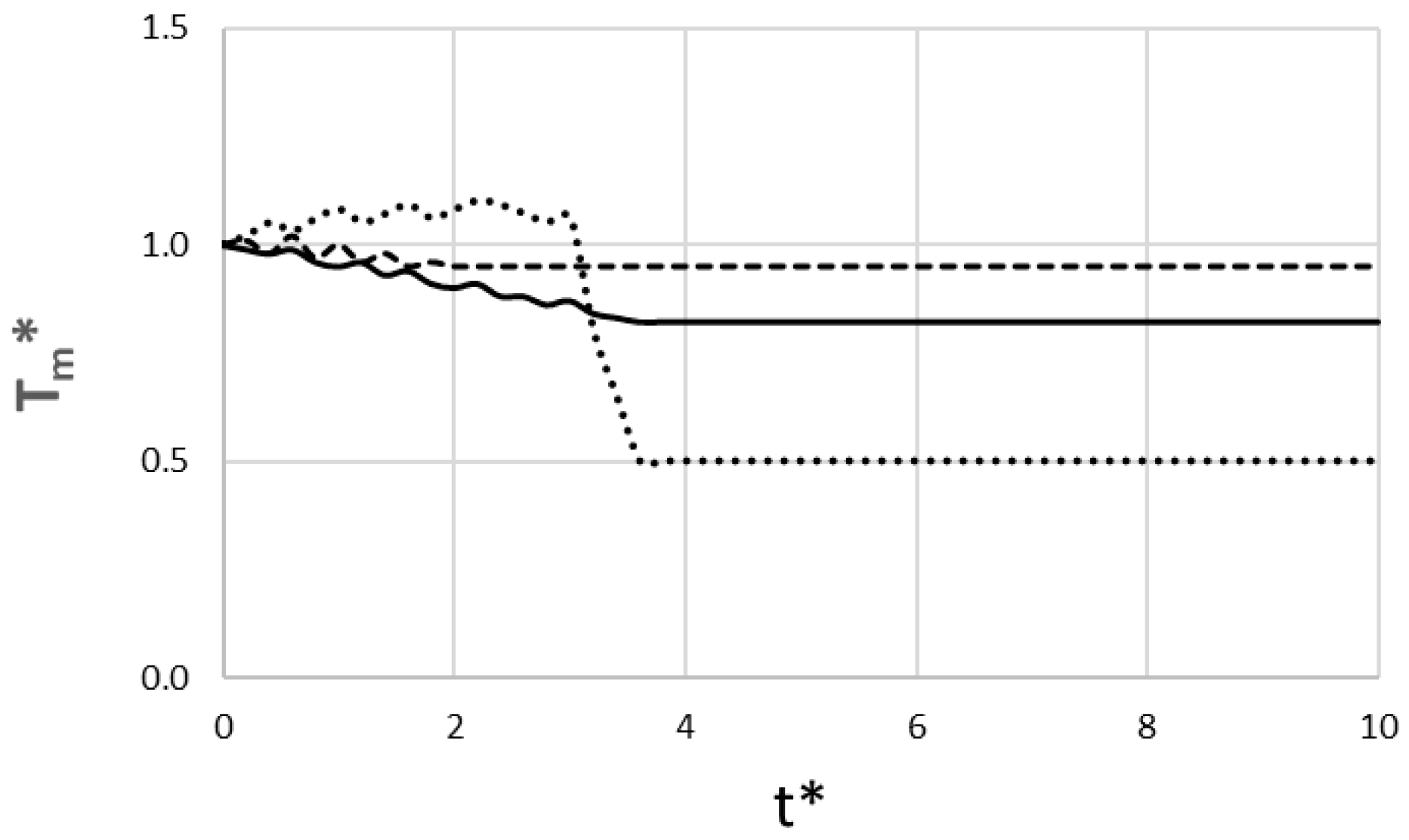

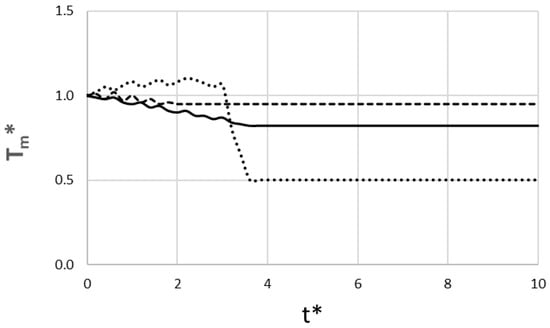

Figure 7 presents the non-dimensional magma temperature at the propagating front of the dike. This figure provides a view of the dike’s thermal health as it ascends. This value, representing the temperature at the propagating front, begins at a normalized value of 1.0 at the source and evolves based on the complex interplay of heat loss and frictional heating. For the pāhoehoe-feeding dike, the cooling is the dominant behavior. The heat loss significantly outweighs any frictional heating, and the result is a steady decline in tip temperature, which drops from 1.00 at t* = 0 to 0.82 at t*~3.6. This cooling is moderate, allowing the dike to erupt well above freezing. For the ʻaʻā-feeding dike, both frictional heating and heat loss are significant. The result is that the magma temperature fluctuates due to localized hot spots of intense frictional heating. Despite this, the dike’s high velocity allows it to erupt very quickly (t*~1.8) before significant net cooling can occur, arriving at the surface hot (Tm*~0.95). For the rhyolite scenario, which is highly viscous, frictional heating dominates heat loss while the dike is moving, and the dike heats up as it ascends, reaching values greater than 1.0. But, at t*~3.0, the dike stalls and immediately stops all frictional heating. Heat loss instantly becomes predominant, resulting in a huge decrease in temperature. This rapid cooling represents the rapid freezing and solidification that permanently arrests the dike.

Figure 7.

Non-dimensional magma temperature at the propagating front versus dimensionless time (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava).

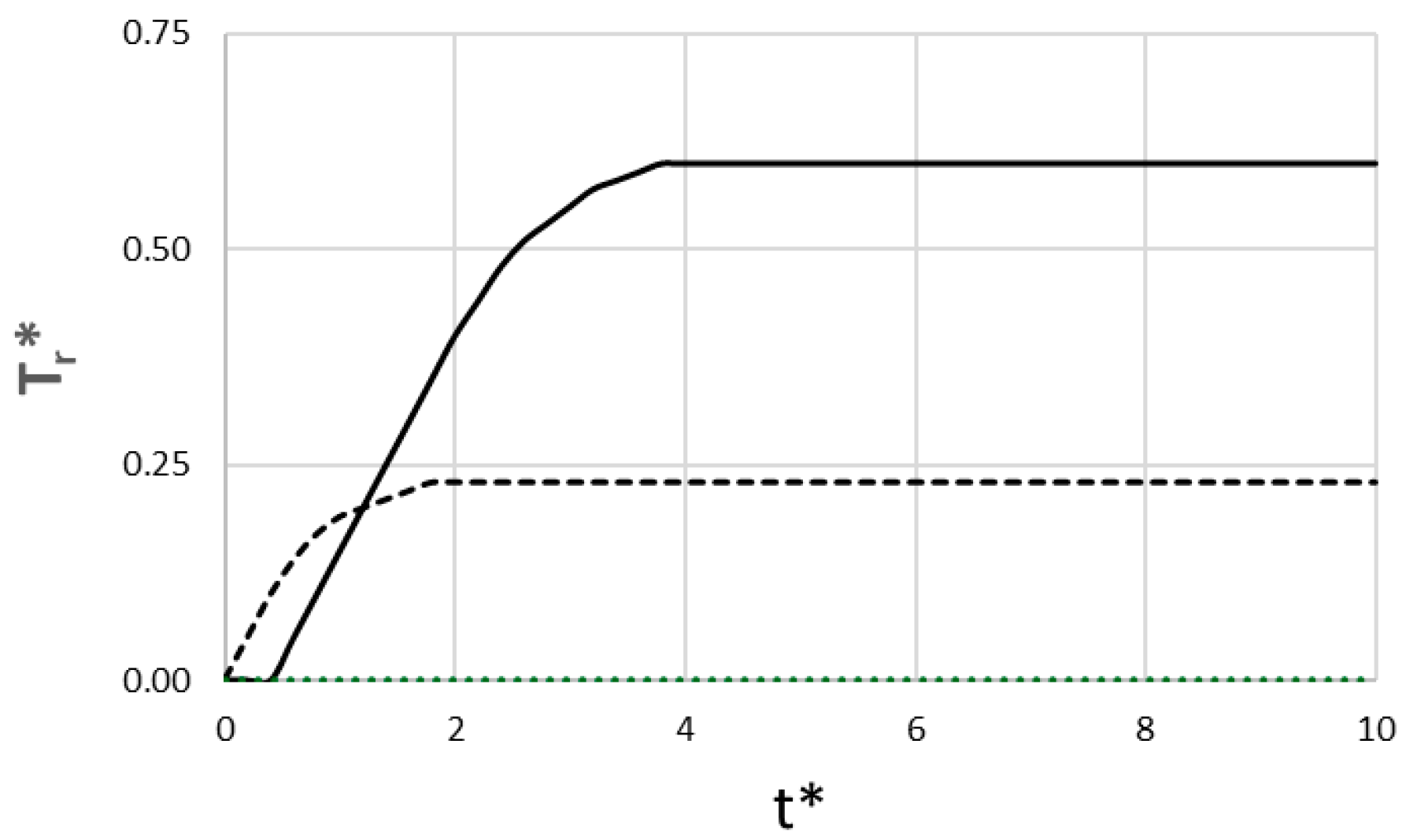

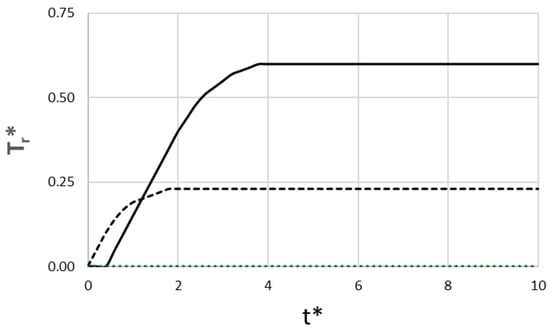

Figure 8 shows the rock wall temperature at a fixed halfway point in the crust. This quantity represents the cumulative thermal damage inflicted on the host rock by the dike’s passage. So, this temperature starts at an ambient value of Tr* = 0.0 and evolves as the dike passes. For the pāhoehoe-feeding dike, the rock temperature at this point only begins to rise around t* = 0.6, consistent with the dike tip arriving at this depth around t* = 0.7. Because the magma flows past this point slowly and steadily until approximately t* = 3.8, heat takes a long time to diffuse into the rock. Thus, there is a smooth and stable temperature increase that reaches a high final temperature of Tr*~0.60, where it stabilizes after the flow stops. For the ʻaʻā-feeding scenario, the dike tip arrives at z* = 0.5 very quickly (around t*~0.45), and the rock wall temperature begins to rise much earlier (t*~0.2). This temperature rise shows a fluctuating profile. Because the dike flows past this point very rapidly and stops heating it at t*~2.0, the total heating duration is very short, and the temperature stabilizes at Tr*~0.23. The arrested rhyolite dike provides a null result at this depth. This is because the dike in this situation stalls at a lower position (av*~0.35) and never reaches z* = 0.5.

Figure 8.

Non-dimensional rock wall temperature at a fixed halfway point in the crust (z* = 0.5) versus dimensionless time (____ pāhoehoe-feeding regime; __ __ ʻaʻā-feeding regime; ….. rhyolite lava).

3.3. Constructal View of Morphing Systems

The constructal law [20] says that for a flow system to “live,” or persist in time, it must evolve a design that provides easier access for the currents flowing through it. This easier access is achieved by minimizing the total opposition, which in this model is a combination of rock fracture, viscous friction, and thermal loss. This evolution involves the system having the “freedom to morph” its own design to minimize these sources of opposition.

The pāhoehoe-feeding run provides the easiest access for the magma, demonstrated by its stability and precision, not by its speed. The magma source velocity is low (~0.3) but very stable. There is not a struggle for change but a smooth, controlled, and precise change. This smooth input, in turn, allows the dike tip velocity to be stable, fluctuating gently around ~0.28. The system’s freedom to design change has already been used to find an optimal path. The resulting dike width (b*~1.0) is very stable, fluctuating gently, provided it is insensitive to the random stochastic properties of the rock. The system’s greatest threat, given its slow speed, is freezing, but its design is thermally precise. The magma tip temperature shows a steady decline to 0.82, which allows it to erupt well above freezing. It does not just survive, it uses its long persistence (t*~3.8) to morph its environment. By slowly and steadily flowing, it induces the rock wall to a high temperature (Tr*~0.6), creating an easier, pre-heated path for future flows. This is the ultimate expression of an evolved design.

The ʻaʻā-feeding run represents a kind of chaotic process of evolution. It is a forceful, chaotic flow that persists (erupts fast at t*~1.8) not through efficiency, but by using its freedom to design change in a struggling, high-energy way to follow a low-opposition path. This flow is not easy, because the source velocity is a flow with high fluctuations. This fluctuating source flow causes a struggling change at the tip, which has a high average velocity but is significantly fluctuating. The dike design change is expressed as a reaction, and the width (b*~1.5) fluctuates very much, not making smooth changes, but struggling to create a path. The magma temperature is erratic, characterized by stochastic fluctuations generated by intense viscous dissipation (friction) in random constrictions. This has a cost, but it is also an adaptation to fight freezing, allowing it to erupt.

Regarding the arrested rhyolite scenario, the system tries to evolve and fights the high friction by having a very wide and highly fluctuating profile (b*). It successfully morphs its temperature (Tm* > 1.0), using friction to heat up as it ascends. But at t*~3.0, the dike loses the freedom to morph design and its tip velocity drops permanently to 0. Thus, opposition to flow became so high that it lost its freedom to evolve, leading to a rapid cooling. The successful rhyolite dike represents the statistically rare (11%) lucky path. By chance, it finds a route of consistently low rock toughness that allows it to maintain a non-zero tip velocity. This non-zero flow is the key to its survival because it allows the dike to maintain its freedom to morph thermally.

4. Discussion

This probabilistic assessment of dike propagation provides important insights into volcanic system dynamics, moving beyond deterministic outcomes to quantify uncertainty. The findings demonstrate that eruption is controlled by a coupled thermo-mechanical–stochastic process. A critical finding is the divergence in eruption probability: basaltic systems are overwhelmingly successful (99.5% for the pāhoehoe-feeding regime and 97.5% for the ʻaʻā-feeding regime), while rhyolitic systems are critically subjected to failure (89% arrest probability). This high failure rate for rhyolite provides crucial validation for geophysical estimates of high-intrusion-to-extrusion ratios in the crust [1,22]. Our results confirm that for high-viscosity magmas, arrest is the norm, and eruption is a rare, low-probability event [1,23]. Furthermore, the distinct flow dynamics observed for basalt (stable pāhoehoe- vs. forceful ʻaʻā-feeding regimes) agree with field observations of lava morphology [3,6,21]. This alignment between our stochastic model and field data strengthens the reliability of our probabilistic framework.

The simulations also reveal two distinct living configurations for basalt, and the pāhoehoe-feeding regime represents a constructally evolved design. It provides the easiest access by flowing with smooth, controlled, and precise change. Its design is insensitive to the random stochastic properties of the rock, allowing it to erupt well above freezing. Its most advanced evolutionary trait is its freedom to morph its environment; i.e., by flowing slowly and steadily, it breaks the rock wall, creating an easier, pre-heated path for flows. The ʻaʻā-feeding regime represents the struggling process of evolution. It uses its freedom to design change in a forceful manner to develop a low-opposition path. This struggling change is seen in its high fluctuations in source velocity and its tip velocity. This high-shear-rate system even morphs its own fluid properties, using intense, localized frictional heating as an adaptation to fight freezing. Both results are supported by field observations [21]. Finally, the rhyolite failure exemplifies a system that ceases its constructal viability at a critical point in its path. The model shows that the cause is a coupled mechanical–thermal cascade. The dike first loses its freedom to flow when it hits a mechanical rock barrier, causing the tip velocity to stop. This stall immediately halts all magma flow, which in turn removes the dike’s freedom to change its thermal design (i.e., frictional heating stops). Heat loss instantly wins, leading to the rapid cooling and solidification that permanently arrests the dike. The few successful rhyolite eruptions can become highly dangerous, a consequence rooted in the same physics that impedes their ascent. When these rhyolite dikes approach the surface, the pressure drops, causing their high gas content to exsolve greatly. In basalt lava, these bubbles would simply escape, leading to an effusive eruption. In rhyolite, however, the magma’s extreme viscosity acts like a bottle cap, trapping the gas and leading to a catastrophic pressure buildup. When this trapped gas fraction exceeds the fragmentation limit, the viscous magma disintegrates violently, leading to an explosive eruption, producing ash and pumice stone [24].

5. Conclusions

Our study concludes that magma dike propagation is a critically coupled, stochastic process where eruption success is fundamentally dictated by magma type. Basaltic systems (pāhoehoe- and ʻaʻā-feeding regimes) are highly robust, with near-certain eruption probabilities (99.5% and 97.5%, respectively). Felsic systems represented by rhyolitic lava, conversely, are critically balanced and inherently prone to failure. They face an 89% probability of arrest, making intrusion the statistically common outcome and eruption a rare event. The dynamics of basaltic eruption illustrate the constructal law, revealing two distinct modes of living (persisting) systems. The pāhoehoe-feeding regime represents the ideal evolved design. It provides easier access by flowing with smooth, controlled, and precise change. Its design is insensitive to the random stochastic properties of the rock. This stable system uses its long persistence to morph its environment, significantly heating the rock wall to create an easier, pre-heated path for future flows. The ʻaʻā-feeding regime represents the process of evolution, a struggling, chaotic system. It uses its freedom to design change in a forceful manner, resulting in a fast but highly unpredictable ascent. Its fluctuating profile and fluctuation in velocity are the signatures of a system actively fighting for a low-opposition path. Rhyolite failure exemplifies the opposite of constructal design, defined by a coupled mechanical–thermal cascade. The system ceases to be viable when it loses its freedom to morph. Once the system’s capacity for flow and thermal evolution is lost, it is overcome by intense heat loss, leading to rapid cooling and irreversible solidification. This fundamental divergence in magma viscosity dictates the final eruption style; effusive (diffusive) eruptions result from the free gas escape in low-viscosity basalt, whereas explosive (fragmenting) eruptions result from a kind of bottle cap effect, where extreme viscosity traps gas, leading to catastrophic pressure buildup in rhyolite.

Future applications of this probabilistic framework include the following: (i) volcanic hazard assessment, where quantifying eruption probability distributions enhances the reliability of forecasting models and informs real-time risk management; and (ii) intrusive resource targeting, where the high failure rate of felsic dikes suggests that these arrested intrusions are the primary mechanism for crustal thickening and mineralization, guiding exploration efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.M.; methodology, A.F.M.; formal analysis, A.F.M., V.R.P. and L.A.O.R.; investigation, A.F.M., V.R.P. and L.A.O.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.M.; writing—review and editing, A.F.M., V.R.P. and L.A.O.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

L.A.O.R. is a grant holder PQ CNPq (307791/2019-0). This research was funded by FCT-Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation, through the ICT multi-annual funding agreement, under the project UID/04683.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study is part of an ongoing project. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to José Francisco for his support in bringing the simulations to completion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gudmundsson, A. Rock Fractures in Geological Processes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte, D.L.; Schubert, G. Geodynamics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.W. The dynamics of lava flow. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2000, 32, 477–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, A.F. Fractal complexity and symmetry in lava flow emplacement. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivalta, E.; Taisne, B.; Bunger, A.P.; Katz, R.F. A review of mechanical models of dike propagation: Schools of thought, key results, and future directions. Tectonophysics 2015, 638, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M. Propagation of magma-filled cracks. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1995, 23, 287–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoback, M.D. Reservoir Geomechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, D.; Russell, J.K.; Dingwell, D.B. Viscosity of magmatic liquids: A model. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 271, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, K.U.; Dingwell, D.B. Viscosities of hydrous leucogranitic melts: A non-Arrhenian model. Am. Mineral. 1996, 81, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, B.D. On the crystallinity, probability of occurrence, and rheology of lava and magma. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1981, 78, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, M.; Castro, J.; Cashman, K.V.; Loewenberg, M. Rheology of bubble-bearing magmas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 87, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Lowenstern, J.B. VolatileCalc: A silicate melt-H2O-CO2 solution model written in Visual Basic for Excel. Comput. Geosci. 2002, 28, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, P.J.; Edmonds, M. The sulfur budget in magmas: Evidence from melt inclusions, submarine glasses, and volcanic gas emissions. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2011, 73, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.M. Fluid Mechanics, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Janecek, J.; Paricaud, P.; Dicko, M.; Coquelet, C. A generalized Kiselev crossover approach applied to Soave–Redlich–Kwong equation of state. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2015, 401, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gonnermann, H.M.; Manga, M. The fluid mechanics inside a volcano. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2007, 39, 321–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaaks, E.H.; Srivastava, R.M. An Introduction to Applied Geostatistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson, H.; Houghton, B.; McNutt, S.; Rymer, H.; Stix, J. (Eds.) The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, T.J. (Ed.) Rock Physics & Phase Relations: A Handbook of Physical Constants; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan, A. Shape and Structure, from Engineering to Nature; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D.W.; Tilling, R.I. Transition of basaltic lava from pahoehoe to aa, Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii: Field observations and key factors. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1980, 7, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, O.; Bergantz, G.W. Rhyolites and their source mushes across tectonic settings. J. Petrol. 2008, 49, 2277–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annen, C.; Blundy, J.D.; Sparks, R.S.J. The genesis of intermediate and silicic magmas in deep crustal hot zones. J. Petrol. 2006, 47, 505–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonnermann, H.M. Magma fragmentation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 43, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).