Abstract

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a systemic mycosis that is endemic in geographical regions of Central and South America. Cases that occur in nonendemic regions of the world are imported through migration and travel. Due to the limited number of cases in Europe, most physicians are not familiar with paracoccidioidomycosis and its close clinical and histopathological resemblance to other infectious and noninfectious disease. To increase awareness of this insidious mycosis, we conducted a systematic review to summarize the evidence on cases diagnosed and reported in Europe. We searched PubMed and Embase to identify cases of paracoccidioidomycosis diagnosed in European countries. In addition, we used Scopus for citation tracking and manually screened bibliographies of relevant articles. We conducted dual abstract and full-text screening of references yielded by our searches. To identify publications published prior to 1985, we used the previously published review by Ajello et al. Overall, we identified 83 cases of paracoccidioidomycosis diagnosed in 11 European countries, published in 68 articles. Age of patients ranged from 24 to 77 years; the majority were male. Time from leaving the endemic region and first occurrence of symptoms considerably varied. Our review illustrates the challenges of considering systemic mycosis in the differential diagnosis of people returning or immigrating to Europe from endemic areas. Travel history is important for diagnostic-workup, though it might be difficult to obtain due to possible long latency period of the disease.

1. Introduction

Paracoccidioidomycosis, also known as South American blastomycosis, is a systemic fungal infection [1] caused by the thermally dimorphic fungi of the species Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and the related species P. americana, P. restrepiensis, P. venezuelensis, and P. lutzii [2,3]. These fungi are endemic to certain geographic regions of Central and South America [4]. Most of the cases of paracoccidioidomycosis are reported in Brazil, followed by Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Argentina [5]. Based on estimates from epidemiological data, the number of cases of paracoccidioidomycosis in Brazil ranges from 3360 to 5600 per year [5]. The incidence of cases considerably varies among regions with low, moderate or high endemicity [5]. According to estimates, in regions with a stable endemic situation, the annual incidence of paracoccidioidomycosis ranges from 1 to 4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [5].

People living in rural areas and working in agriculture are particularly at risk for this mycosis [1]. The risk of infection is higher for men than women [6]. The chronic form (adult type) accounts for the majority of cases [4]. This form of paracoccidioidomycosis is progressive over months or years and can be unifocal, if only one site is affected, or multifocal, in case of dissemination [7]. The organ most frequently affected is the lung [7]. Skin, oral mucosa, pharynx, larynx, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, central nervous system, bones, or joints may also be affected [8]. Symptoms of the disease can be systemic (e.g., weight loss, general weakness) or related to specific organ affection (e.g., cough, shortness of breath) [8]. In particular, pulmonary affection, lymphadenopathy, and B symptoms often lead to clinical signs similar to tuberculosis [8,9].

Paracoccidioidomycosis differential diagnosis is particularly challenging, because clinical signs and symptoms, as well as histopathological findings, resemble numerous other infections (e.g., tuberculosis) and noninfectious diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis) [8]. In addition, a long latency period [7] between exposure and manifestation of symptoms, as well as limited clinical experience, make adequate diagnosis difficult. In nonendemic areas, the history of travel and residency in endemic regions is a key to consider paracoccidioidomycosis for differential diagnosis.

Most physicians in nonendemic areas are unfamiliar with the clinical picture of endemic systemic mycoses because they are rarely presented to them. This in turn increases the risk that patients with paracoccidioidomycosis end up with misdiagnosis or remain undiagnosed. Subsequently, this results in no or inappropriate therapy. Therefore, it is important to provide information about the disease presentations in nonendemic regions.

A previously published review by Ajello et al. 1985 [10] comprehensively summarized internationally published cases of paracoccidioidomycosis from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, North America, and Europe [10]. However, this review is now 35 years old and needs to be updated.

The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the evidence of paracoccidioidomycosis imported to nonendemic European countries. Thereby, we aim to increase awareness for this fungal infection and provide important information regarding its challenging diagnosis.

2. Materials and Methods

For reporting of this systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) [11].

2.1. Information Sources and Literature Search

An experienced information specialist searched PubMed and Embase (Embase.com ((accessed on 16 December 2020))) from inception to June 15 and 16, 2020 to identify relevant publications. We used a combination of subject headings and title and abstract free-text terms. We restricted our search to adults and humans. We have provided the detailed search strategy in Appendix A (Table A1 and Table A2). In addition to database searches, we used Scopus (Elsevier) on 16 June 2020 to perform forward and backward citation tracking of included publications and reviews. We also manually screened reference lists of these records, in case the reference lists available via Scopus were incomplete. To identify publications published prior to 1985, we used the previous review published by Ajello et al. [10]. We used references found by our search to identify relevant publications published in 1985 or later.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Our population of interest was adults of any age and origin diagnosed with paracoccidioidomycosis (South American blastomycosis) in geographic Europe. We considered any case description of an acute or chronic form of paracoccidioidomycosis as eligible for this review if authors provided sufficient clinical information on number of cases, country of exposure, and diagnosis. Publications were included regardless of language and type of publication. We included case series and case reports, observational studies, reviews providing information mentioned above and published as abstracts, full-articles, letters, and editorials. Table 1 provides a summary of eligibility criteria.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

After a pilot round, two reviewers independently screened each title and abstract. Eligible publications subsequently underwent independent dual full-text assessment. We solved disagreements by consensus or involvement of a senior reviewer. Throughout the whole study selection process, we used the web-based software Covidence [12]. We organized search and screening results in an EndNote® X9 bibliographic database (Clarivate, PA, USA).

2.3. Data Collection Process and Evidence Synthesis

We extracted the following relevant information from each article into pilot-tested evidence tables: author, year, study design, language, country of diagnosis, country of exposure, number of cases, patient characteristics (age, gender, occupation, affected organ(s), systemic antimycotic therapy, and treatment response), and latency period. If the publication language was not English, we asked native speakers to translate or used the online tool DeepL (http://www.deepl.com (accessed on 15 January 2021)) for translations into German. We synthesized data of identified articles narratively.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

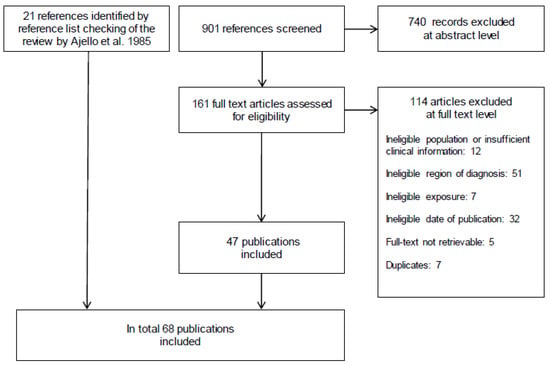

Overall, we identified 83 case reports from 11 European countries, published in 68 articles. Figure 1 shows details of the study selection process.

Figure 1.

Modified Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [11].

Table 2 summarizes the number of publications and reported cases by country. Spain reported most of the cases, followed by Italy and Germany. The majority of articles were written in English or Spanish. Other publication languages were German, Portuguese, Italian, Norwegian and French.

Table 2.

Number of identified publications and reported cases of paracoccidioidomycosis by country of diagnosis.

3.2. Clinical Patient Characteristics

The age of the patients ranged from 24 to 77 years. The infection mainly affected men. In most cases, exposure to Paracoccidioides took place in Venezuela, followed by Brazil and Ecuador. The most common occupations were field and construction workers. Latency period, defined as the period from leaving the endemic region until occurrence of first symptoms or medical contact, ranged from six days to 50 years. Table 3 shows patient characteristics, country of exposure, latency period, affected organ(s), systemic antimycotic therapy and response to treatment grouped by countries in which the diagnosis was made.

Table 3.

Imported cases of paracoccidioidomycosis from Central and South America diagnosed in Europe.

3.3. Differential Diagnosis

Table A3 of Appendix A shows infectious and non-infectious diseases that were considered for differential diagnosis of cases in the included articles.

3.4. Diagnostic Work-up

The diagnostic workup varied across publications. Usually, Paracoccidioides spp. was identified from clinical specimens through microscopic visualization and/or culture. In addition, some of the authors reported results from serological tests and/or molecular biological techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Table A3 provides information on diagnostic workup in individual cases of paracoccidioidomycosis.

In general, direct examination, using 10% potassium hydroxide applied to different samples, is effective and inexpensive. A histologic examination of tissue specimens using silver methenamine or periodic acid-Schiff stain is common and practical when patients present with oral or other skin lesions. In a clinical sample, Paracoccidioides spp. appear as globose yeast cells with multiple buds and a thick refractile wall [81].

4. Discussion

Our systematic review summarizes the evidence on published case reports of imported paracoccidioidomycosis diagnosed in Europe. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most recent and comprehensive review of published cases of this systematic mycosis endemic to geographical regions of Central and South America. While narrative reviews on patients with this disease often included a nonsystematic search, we followed a systematic approach with a much broader scope to identify all published cases of paracoccidioidomycosis imported to Europe. In addition, the last systematic assessment of case reports on paracoccidioidomycosis was published in 1985, almost four decades ago [10]. A more recent narrative review focused only on cases diagnosed in Spain [82].

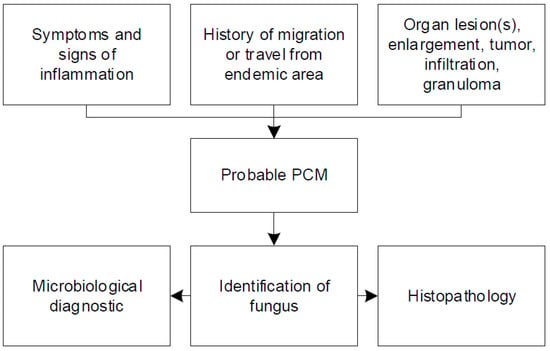

Our systematic review of case reports and case series emphasizes the clinical challenges and pitfalls of paracoccidioidomycosis. Most of the physicians in non-endemic regions such as Europe are unfamiliar with systemic mycosis. They struggle with the diagnostic work-up and management due to several reasons. In general, depending on the type, clinical presentation of patients with paracoccidioidomycosis is variable [4]. A major issue is the clinical similarity to several other infectious and non-infectious diseases [81]. Paracoccidioidomycosis is commonly misdiagnosed as tuberculosis [83]. The clinical picture of tuberculosis resembles the chronic progressive form of paracoccidioidomycosis [9]. The differential diagnosis of chronic paracoccidioidomycosis with lung involvement also includes coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, pneumoconiosis, interstitial pneumonia, and malignancy [84]. Inappropriate treatment could have harmful consequences for the patient, without any prognostic impact on systemic mycosis. In addition, the latency period from pathogen exposure to development of symptoms is highly variable and might comprise several decades when patients might already have left the endemic region [7]. Therefore, clinicians must inquire about any short- and long-term stay (travel and residency) in endemic areas and even time abroad many years preceding presentation. Figure 2 summarizes important aspects that have to be considered for diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis, including signs and symptoms, travel history, and imaging.

Figure 2.

Summary of important aspects for the diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis.

If paracoccidioidomycosis is considered for differential diagnosis, clinicians should provide this information to the microbiologist, pathologist and other laboratory personnel to ensure that adequate methods for direct and indirect identification of the pathogen are applied. In addition, laboratory personnel need to apply safety precautions when collected specimens are handled.

The strengths of our work are the systematic literature search and screening. However, this systematic review has several limitations. First, we have not included cases that may have been diagnosed but never published. Second, because translation methods varied, we might have missed relevant information in the articles. A native speaker translated Spanish texts into German but online electronic translation tools provided translations for all other languages (11 publications) except texts published in English and German. Third, our findings rely on not uniformly structured case reports and cases series that are considered as low-level evidence. Finally, although we conducted comprehensive additional literature searches, we might have missed studies not cited in previous reviews and not indexed in electronic databases due to very early publication dates or non-indexed journals.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review highlights the importance of considering systemic mycosis in the differential diagnosis of people with symptoms of tuberculosis who have either returned to Europe from endemic areas or were natives of endemic countries who immigrated to Europe. In light of systemic mycosis’s potentially long latency period, extensive evaluation of travel history is an essential key for a quick and correct diagnosis of systematic endemic mycosis such as paracoccidioidomycosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and G.W.; methodology, G.W., A.G. and G.G.; literature search, I.K.; literature screening, A.G., V.M, C.Z., and G.W.; data extraction, A.G., V.M., M.V.d.N., C.Z. and G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.W.; writing—review and editing, A.G, B.W., D.M., V.M., I.K., M.V.d.N., C.Z., and G.G.; supervision, B.W., D.M. and G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by internal funds from the Department of Evidence-based Medicine and Evaluation, Danube University Krems, Austria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Edith Kertesz from Danube University for administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PCM | paracoccidioidomycosis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search Strategy Pubmed 15 June 2020.

Table A1.

Search Strategy Pubmed 15 June 2020.

| Search Number | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Paracoccidioidomycosis” [Mesh] | 1833 |

| 2 | Paracoccidioidomycos* [tiab] | 1782 |

| 3 | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis [tiab] | 1611 |

| 4 | paracoccidioidal granuloma [tiab] | 9 |

| 5 | south american blastomycosis [tiab] | 272 |

| 6 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 | 2858 |

| 7 | “Europe” [Mesh] | 1,408,827 |

| 8 | “Emigrants and Immigrants” [Mesh] | 12,277 |

| 9 | “Travel” [Mesh:NoExp] | 24,916 |

| 10 | (Albania* [tiab] OR Andorra* [tiab] OR Armenia* [tiab] OR Austria* [tiab] OR Azerbaijan* [tiab] OR Belarus* [tiab] OR Belgi* [tiab] OR Bosnia* [tiab] OR Herzegov* [tiab] OR Bulgaria* [tiab] OR Croatia* [tiab] OR Cypr* [tiab] OR Czech [tiab] OR Denmark [tiab] OR danish [tiab] OR Estonia* [tiab] OR Finland [tiab] OR finnish [tiab] OR France [tiab] OR french [tiab] OR Georgia* [tiab] OR German* [tiab] OR Greece [tiab] OR greek [tiab] OR Hungar* [tiab] OR Iceland* [tiab] OR Ireland [tiab] OR irish [tiab] OR Italy [tiab] OR italian [tiab] OR Kazak* [tiab] OR Kosov* [tiab] OR Latvia* [tiab] OR Liechtenstein* [tiab] OR Lithuania* [tiab] OR Luxembourg* [tiab] OR Macedonia* [tiab] OR Malta [tiab] OR maltese [tiab] OR Moldov* [tiab] OR Monac* [tiab] OR Montenegr* [tiab] OR Netherlands [tiab] OR dutch [tiab] OR Norway [tiab] OR norwegian [tiab] OR Poland [tiab] OR polish [tiab] OR Portug* [tiab] OR Romania* [tiab] OR Russia* [tiab] OR San Marino [tiab] OR Serbia* [tiab] OR Slovakia* [tiab] OR Slovenia* [tiab] OR Spain [tiab] OR spanish [tiab] OR Sweden [tiab] OR swedish [tiab] OR Switzerland [tiab] OR swiss [tiab] OR Turkey [tiab] OR turkish [tiab] OR Ukrain* [tiab] OR United Kingdom [tiab] OR britain [tiab] OR british [tiab]) | 1,082,126 |

| 11 | (Albania* [ad] OR Andorra* [ad] OR Armenia* [ad] OR Austria* [ad] OR Azerbaijan* [ad] OR Belarus* [ad] OR Belgi* [ad] OR Bosnia* [ad] OR Herzegov* [ad] OR Bulgaria* [ad] OR Croatia* [ad] OR Cypr* [ad] OR Czech [ad] OR Denmark [ad] OR danish [ad] OR Estonia* [ad] OR Finland [ad] OR finnish [ad] OR France [ad] OR french [ad] OR Georgia* [ad] OR German* [ad] OR Greece [ad] OR greek [ad] OR Hungar* [ad] OR Iceland* [ad] OR Ireland [ad] OR irish [ad] OR Italy [ad] OR italian [ad] OR Kazak* [ad] OR Kosov* [ad] OR Latvia* [ad] OR Liechtenstein* [ad] OR Lithuania* [ad] OR Luxembourg* [ad] OR Macedonia* [ad] OR Malta [ad] OR maltese [ad] OR Moldov* [ad] OR Monac* [ad] OR Montenegr* [ad] OR Netherlands [ad] OR dutch [ad] OR Norway [ad] OR norwegian [ad] OR Poland [ad] OR polish [ad] OR Portug* [ad] OR Romania* [ad] OR Russia* [ad] OR San Marino [ad] OR Serbia* [ad] OR Slovakia* [ad] OR Slovenia* [ad] OR Spain [ad] OR spanish [ad] OR Sweden [ad] OR swedish [ad] OR Switzerland [ad] OR swiss [ad] OR Turkey [ad] OR turkish [ad] OR Ukrain* [ad] OR United Kingdom [ad] OR britain [ad] OR british [ad]) | 5,875,438 |

| 12 | europ* [tiab] OR immigrant* [tiab] OR travel* [tiab] | 383,712 |

| 13 | non endemic [tiab] OR nonendemic [tiab] | 4492 |

| 14 | #13 OR #12 OR #11 OR #10 OR #9 OR #8 OR #7 | 7,173,281 |

| 15 | #6 AND #14 | 204 |

| 16 | (“Animals” [Mesh] NOT “Humans” [Mesh]) | 4,707,502 |

| 17 | #15 NOT #16 | 175 |

Table A2.

Search Strategy Embase 16 June 2020.

Table A2.

Search Strategy Embase 16 June 2020.

| No. | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | ‘south american blastomycosis’/exp OR ‘paracoccidioides brasiliensis’/exp | 3026 |

| #2 | paracoccidioidomycos*:ab,ti OR ‘paracoccidioides brasiliensis’:ab,ti OR ‘paracoccidioidal granuloma’:ab,ti OR ‘south american blastomycosis’:ab,ti | 3075 |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 | 3620 |

| #4 | ‘europe’/exp OR ‘immigrant’/exp OR ‘travel’/exp | 1,695,885 |

| #5 | albania*:ca,ab,ti OR andorra*:ca,ab,ti OR armenia*:ca,ab,ti OR austria*:ca,ab,ti OR azerbaijan*:ca,ab,ti OR belarus*:ca,ab,ti OR belgi*:ca,ab,ti OR bosnia*:ca,ab,ti OR herzegov*:ca,ab,ti OR bulgaria*:ca,ab,ti OR croatia*:ca,ab,ti OR cypr*:ca,ab,ti OR czech:ca,ab,ti OR denmark:ca,ab,ti OR danish:ca,ab,ti OR estonia*:ca,ab,ti OR finland:ca,ab,ti OR finnish:ca,ab,ti OR france:ca,ab,ti OR french:ca,ab,ti OR georgia*:ca,ab,ti OR german*:ca,ab,ti OR greece:ca,ab,ti OR greek:ca,ab,ti OR hungar*:ca,ab,ti OR iceland*:ca,ab,ti OR ireland:ca,ab,ti OR irish:ca,ab,ti OR italy:ca,ab,ti OR italian:ca,ab,ti OR kazak*:ca,ab,ti OR kosov*:ca,ab,ti OR latvia*:ca,ab,ti OR liechtenstein*:ca,ab,ti OR lithuania*:ca,ab,ti OR luxembourg*:ca,ab,ti OR macedonia*:ca,ab,ti OR malta:ca,ab,ti OR maltese:ca,ab,ti OR moldov*:ca,ab,ti OR monac*:ca,ab,ti OR montenegr*:ca,ab,ti OR netherlands:ca,ab,ti OR dutch:ca,ab,ti OR norway:ca,ab,ti OR norwegian:ca,ab,ti OR poland:ca,ab,ti OR polish:ca,ab,ti OR portug*:ca,ab,ti OR romania*:ca,ab,ti OR russia*:ca,ab,ti OR ‘san marino’:ca,ab,ti OR serbia*:ca,ab,ti OR slovakia*:ca,ab,ti OR slovenia*:ca,ab,ti OR spain:ca,ab,ti OR spanish:ca,ab,ti OR sweden:ca,ab,ti OR swedish:ca,ab,ti OR switzerland:ca,ab,ti OR swiss:ca,ab,ti OR turkey:ca,ab,ti OR turkish:ca,ab,ti OR ukrain*:ca,ab,ti OR ‘united kingdom’:ca,ab,ti OR britain:ca,ab,ti OR british:ca,ab,ti | 10,276,132 |

| #6 | europ* OR ‘non endemic’ OR nonendemic OR travel*:ab,ti OR imported:ti | 2,203,591 |

| #7 | immigrant* | 34,244 |

| #8 | #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 | 11,651,119 |

| #9 | #3 AND #8 | 457 |

| #10 | ‘animal’/exp NOT ‘human’/exp | 5,449,241 |

| #11 | #9 NOT #10 | 405 |

| #12 | ‘groups by age’/exp NOT ‘adult’/exp | 2,775,185 |

| #13 | #11 NOT #12 | 397 |

| #14 | ‘case report’/exp OR ‘case study’/exp OR ‘letter’/exp | 3,471,553 |

| #15 | case:ab,ti OR cases:ab,ti | 4,628,697 |

| #16 | ‘review’/exp OR ‘evidence based medicine’/exp | 3,575,830 |

| #17 | review:ab,ti OR systematic:ab,ti OR search*:ab,ti OR ‘meta analy*’:ab,ti OR metaanaly*:ab,ti | 2,588,995 |

| #18 | #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 | 10,847,515 |

| #19 | #13 AND #18 | 256 |

Table A3.

Signs and symptoms, differential diagnosis and diagnostic work-up.

Table A3.

Signs and symptoms, differential diagnosis and diagnostic work-up.

| Author, Year | Symptoms and Signs | Differential Diagnosis | Specimen for Histopathology | Histo-Logy 1 | Micro-Biology 2 | Sero-Logy | PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUSTRIA | |||||||

| Wagner et al. 2016 [21] | Chest and abdominal pain, weight loss, night sweats, cough | Tuberculosis | Left adrenal gland biopsy, extirpation of a right cervical lymph node | + | + | NR | + |

| Mayr et al. 2004 [22] | Cough, lymphadenopathy, weight loss | Tuberculosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, mycosis | Lung biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| BULGARIA | |||||||

| Balabanov et al. 1964 [23] | Ulcerous oral and cutaneous lesions, lymphadenopathy | Tuberculosis | Peribuccal lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| GERMANY | |||||||

| Kayser et al. 2019 [24] | Cough, dyspnea | Sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis | Lung biopsy | + | + | + | + |

| Slevogt et al. 2004 [25] | Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy, weight loss | Tuberculosis | Cervical lymph node biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Horré et al. 2002 [26] | Erythematous and swollen lips, mucocutaneous pustules and ulcerations, oral nodules, occasional night sweats | Leishmaniosis, tropical pulmonary mycosis, gammopathy | Oral lesion biopsy | + | + | + | + |

| Köhler et al. 1988 [27] | Cheilitis, erosive stomatitis, loss of teeth, dysphagia, aphonia, cough, night sweats, weight loss | Tropical disease | NR | NR | + | + | NR |

| Neveling 1988 [28] | Flue like symptoms, dry cough | Coccidiosis, histoplasmosis, North American blastomycosis | NR | NR | NR | + | NR |

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | ||

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | ||

| Braeuninger et al. 1985 [29], Hastra et al. 1985 [30] | Flue like symptoms, cervical lymphadenopathy, skin lesions, cough, dyspnea, pain in the left leg | Tuberculosis, sarcoidosis | Lymph node biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Altmeyer 1976 [31] | Respiratory insufficiency, cervical lymphadenopathy, painful infiltrations of the soft palate, hypersalivation, ulcerations of the feet, weight loss, dysphagia, dysphonia | Tuberculosis, Wegner’s granulomatosis | Lung and skin lesion biopsy | + | − | NR | NR |

| PORTUGAL | |||||||

| Ferreira et al. 2017 [32] | Labial lesion, dry cough, inguinal and axillary lymphadenopathy, weight loss | Cryptococcosis | Lip lesion and lung biopsy, inguinal lymph node resection | + | − | NR | + |

| Coelho et al. 2013 [33] | Odynophagia, dysphagia, irregular and ulcerated oral mucosa | NR | Oropharyngeal mucosa biopsy | + | NR | NR | NR |

| Alves et al. 2013 [34] | Skin lesion, oral mucosal ulcerations | Coccidioidomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis | Skin lesion and oral mucosa biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Armas et al. 2012 [35] | Ulcerated skin and nasal mucosa lesion | NR | Skin lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Carvalho et al. 2009 [36] | Fever, epigastric pain, anorexia, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, skin lesions | Skin biopsy and lymph node | + | NR | NR | NR | |

| Villar et al. 1963 [37] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Oliveira et al. 1960 [38] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| SPAIN | |||||||

| Chamorro-Tojeiro et al. 2020 [20] | Fever, arthralgia, myalgia, dyspnea, dry cough, sweating, general cutaneous rash | Bacterial respiratory infection | NR | NR | − | + | NR |

| Agirre et al. 2019 [19] | Fever, productive cough, exertional dyspnea | Bacterial respiratory infection | NR | NR | − | + | NR |

| Fever, myalgia, asthenia | NR | NR | NR | − | + | NR | |

| Molina-Morant et al. 2018 [18] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Navascués et al. 2013 [39] | Productive cough, weight loss, asthenia, lymphadenopathy, skin lesions | NR | Lung biopsy | + | − | + | + |

| Buitrago et al. 2011 [40] 3 | Fever, asthenia, ulcerated pustular skin lesions, extremities | NR | Skin biopsy | + | NR | + | + |

| Productive cough | NR | NR | + | NR | + | + | |

| NR | NR | Cerebral biopsy | + | NR | + | + | |

| NR | NR | NR | + | NR | + | + | |

| NR | NR | Lung biopsy | NR | + | NR | + | |

| NR | NR | Oral mucosa biopsy | + | NR | + | + | |

| Pujol-Riqué et al. 2011 [41] | Productive cough, hemoptysis, night sweats, skin lesions | Sarcoidosis | Lung and skin biopsy | − | + | NR | NR |

| Ramírez-Olivencia et al. 2010 [42] | Fever, dyspnea, productive cough, hemoptysis, night sweats, loss of appetite, weight loss | NR | Lung biopsy | NR | − | + | + |

| Botas-Velasco et al. 2010 [43] | Cough, fever, weight loss, retromolar mass | Sarcoidosis | Retromolar mass and laryngeal biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Mayayo et al. 2007 [44] | Skin lesions | Blastomycosis | Skin lesion biopsy | + | NR | NR | NR |

| López Castro et al. 2005 [45] | Dyspnea, dry cough, fever, weight loss, skin lesions | Sarcoidosis | Lung and skin biopsy | + | NR | − | NR |

| Ginarte et al. 2003 [46] | Ulcerative lesions from upper left jaw to labial mucosa and nasal grave | Squamous cell carcinoma | Lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Ulcerative lesions left cheek mucosa, periodontitis with loss of several teeth | Tuberculosis, squamous cell carcinoma | Lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR | |

| Mass and ulcerative lesions in cheek mucosa | Squamous cell carcinoma | Lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR | |

| Garcia Bustínduy et al. 2000 [47] | Ulcerative skin lesion | NR | Skin lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Del Pozo et al. 1998 [48] | Lesions upper labial mucosa and nasal fossa | NR | Lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Garcia et al. 1997 [49] | Lesions of labial and palatal mucosa | NR | Lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Pereiro et al. 1996 [50] | Tumoral mass of the upper jaw, ulcerated lesion in the upper left jaw, extended to the lip mucosa and the nasal grave | Epidermoid carcinoma | Lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Miguélez et al. 1995 [17] | Fever, weight loss, dyspnea, ulcerated mass right tonsil, lymphadenopathy | Pulmonary fibrosis | Ulcerated mass biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Palatal mass, cervical lymphadenopathy | NR | Palatal mass biopsy | + | + | NR | NR | |

| Pereiro Miguens et al. 1987 [16] | Oral mucosal lesions, gingivitis | Tuberculosis | Mucosa biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Simon Merchán et al. 1970 [15] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Pereiro Miguens et al. 1974 [14], Pereiro Miguens et al. 1972 [51] | Epididymitis, gingivitis, oral ulcerative lesion | Tuberculosis | Epididymis and oral lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Asthenia, ulcerative oral lesions, labial edema | NR | Oral lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR | |

| Vivancos et al. 1969 [13] | Oral mucosal lesions | Pseudoneoplasia | Oral lesion biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| GREAT BRITAIN | |||||||

| De Cordova et al. 2012 [52] | Submandibular mass, oral ulcerative lesions | NR | Oral lesion and submandibular mass biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Sierra et al. 2011 [53] | Dyspnea, lip lesion, ulcer on tonsil and uvula | Malignancy, sarcoidosis, squamous cell carcinoma | Lip lesion excision, ulcer biopsy | + | NR | + | NR |

| Walker et al. 2008 [54] | Cough, dyspnea, plantar pruritus, painful skin lesions on his legs, face and feet, hepatomegaly, weight loss | NR | Skin biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Bowler et al. 1986 [55] | Cough, dyspnea, and wheeze on exertion | Lymphangitis carcinomatosa | Lung biopsy | + | NR | + | NR |

| Symmers 1966 [56] | Asymptomatic | NR | Spleen (autopsy) | + | NR | NR | NR |

| Skin ulceration | NR | Skin lesion excision | + | NR | NR | NR | |

| ITALY | |||||||

| Borgia et al. 2000 [57] | Fever, pain, and inflammation of left knee | Malignancy | Left femur biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Pecoraro et al. 1998 [58] | Weight loss, night sweat, pain left knee | NR | Left femur biopsy | + | NR | NR | NR |

| Solaroli et al. 1998 [59] | Skin lesion, asthenia, fever, loss of vision | NR | Skin lesion excision | + | + | NR | NR |

| Fulciniti et al. 1996 [60] | Weight loss, night, sweats, pain in left knee | Metastatic lung cancer | Left femur biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Cuomo et al. 1985 [61] | Productive cough, weight loss, asthenia, skin lesions | Tuberculosis, lupus vulgaris | Lung and skin lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Benoldi et al. 1985 [62] | Ulcerative skin lesions, cough, fatigue, malaise, weight loss | Tuberculosis, lupus vulgaris | Skin lesion biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Finzi et al. 1980 [63] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Velluti et al. 1979 [64] | Cough, dyspnea | Bronchitis, tuberculosis | Lung biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| Lasagni et al. 1979 [65] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Scarpa et al. 1965 [66] | Cough, asthenia, weight loss, night sweats, lymphadenitis, ulcerative oral lesions | Tuberculosis | Lymph node and lung biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| Schiraldi et al. 1963 [67] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Molese et al. 1956 [68] | Oral mucosa lesions, cervical lymphadenopathy, fever, cough | Tuberculosis, leishmaniosis, pneumoconiosis, lues, malignancy | Oral mucosa and tonsillar biopsy | + | NR | NR | NR |

| Farris 1955 [69] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Bertaccini 1934 [70] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| Dalla Favera 1914 [71] | Full-text not available | ||||||

| FRANCE | |||||||

| Heleine et al. 2020 [72] | Skin lesions, ulcero-nodular lesions lips and mouth, cough, fever, inguinal lymphadenopathy, asthenia, weight loss | HIV, tuberculosis | Skin biopsy | − | + | NR | NR |

| Dang et al. 2017 [73] | Nodular slightly painful, nonulcerated lesion of the tongue, cervical lymphadenopathy | NR | Lingual lesion biopsy | + | NR | NR | + |

| Sambourg et al. 2014 [74] | Partially ulcerous and crusted erythematous lesion left auricle extending to the pre-auricular region | Leishmaniosis | Skin lesion biopsy | + | + | − | + |

| Laccourreye et al. 2010 [75] | Dysphonia, laryngitis | Chronic laryngitis | Laryngeal biopsy, removed mucosa | + | + | NR | NR |

| Poisson et al. 2007 [76] | Seizures | Brain tumor | Single cerebral lesion surgically excised | + | + | + | NR |

| NETHERLANDS | |||||||

| Van Damme et al. 2006 [77] | Dyspnea, cough, wheezing, weight loss, tiredness, fever, night sweats, periodontitis, oral ulceration, macrohematuria | Sarcoidosis, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, oral carcinoma | Lung and oral mucosa biopsy | + | + | + | NR |

| NORWAY | |||||||

| Maehlen et al. 2001 [78] | Dizziness, nausea, headache, hearing loss, hemiplegia | Cerebral tuberculosis | Brain biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

| SWITZERLAND | |||||||

| Stanisic et al. 1979 [79], Wegmann et al. 1959 [80] | Submandibular and cervical lymphadenopathy, oral ulceration | Tuberculosis, Morbus Wegener, lues, bartonellosis, Morbus Hodgkin, neoplasma, blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, cryptococcosis | Oral mucosa and cervical lymph node biopsy | + | + | NR | NR |

Abbreviations: NR, not reported or not performed; +, positive for Paracoccidioides spp.; −, negative for Paracoccidioides spp.; 1 Fungal structures were identified in at least one of the biopsy/excision specimen; 2 Microbiology includes microscopy and/or culture; 3 Signs and symptoms obtained for case 1 and case 2 obtained from Buitrago et al. 2009 [85].

References

- Bocca, A.L.; Amaral, A.C.; Teixeira, M.M.; Sato, P.; Yasuda, S.M.A.; Felipe, S.M.S. Paracoccidioidomycosis: Eco-epidemiology, taxonomy and clinical and therapeutic issues. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrycyk, M.F.; Garces, G.H.; Bosco, S.D.M.G.; de Oliveira, S.L.; Marques, S.A.; Bagagli, E. Ecology of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, P. lutzii and related species: Infection in armadillos, soil occurrence and mycological aspects. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turissini, D.A.; Gomez, O.M.; Teixeira, M.M.; McEwen, J.G.; Matute, D.R. Species boundaries in the human pathogen Paracoccidioides. Fungal Genet. Biol. FG B 2017, 106, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.; Talhari, C.; Talhari, S. Advances in paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 35, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R. New trends in paracoccidioidomycosis epidemiology. J. Fungi 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, J.; Restrepo, A.; Clemons, K.V.; Stevens, D.A. Hormones and the Resistance of Women to Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, E.; Castaneda, E.; Restrepo, A. Paracoccidioidomycosis: An update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 6, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanke, B.; Aidé, M.A. Chapter 6-paracoccidioidomycosis. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2009, 35, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Salzer, H.J.F.; Burchard, G.; Cornely, O.A.; Lange, C.; Rolling, T.; Schmiedel, S.; Libman, M.; Capone, D.; Le, T.; Dalcolmo, M.P.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Systemic Endemic Mycoses Causing Pulmonary Disease. Respiration 2018, 96, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajello, L.; Polonelli, L. Imported paracoccidioidomycosis: A public health problem in non-endemic areas. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 1, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innovation, V.H. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Vivancos, G.; Marrero, B.; Hernández, B.; Padrón, G. La blastomicosis sudamericana en España. Primera observación en las Islas Canarias. In Proceedings of the VV. AA. Actas VII Congreso Hispano-Portugués de Dermatología Médico Quirúrgica, Granada, Spain, 22–25 October 1969; pp. 330–335. [Google Scholar]

- Pereiro, M.M. Two cases of South American blastomycosis observed in Spain. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. 1974, 65, 509–522. [Google Scholar]

- Merchán, S.A.; Escudero, R.; Lavin, R. Un caso de blastomicosis sudamericana observado en España. Med. Cutan. Iber. Lat. Am. 1970, 5, 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- Miguens, P.M.; Ferreiros, P.M.M. A propósito de un nuevo caso de paracoccidioidomicosis observado en España. Ver. Iber. Micol. 1987, 4, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Miguélez, M.; Amerigo, M.J.; Perera, A.; Rosquete, J. Imported paracoccidioidomycosis. Apropos of 2 cases. Med. Clin. (Barc) 1995, 105, 756. [Google Scholar]

- Morant, M.D.; Montalvá, S.A.; Salvador, F.; Avilés, S.A.; Molina, I. Imported endemic mycoses in Spain: Evolution of hospitalized cases, clinical characteristics and correlation with migratory movements, 1997–2014. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirre, E.; Osorio, A.; de Tejerina, C.F.J.M.; Arrondo, R.F.; Bermejo, S.Y. Bilateral interstitial pneumonia after recent trip to Peru. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2019, 37, 609–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tojeiro, C.S.; Sarria, G.A.; Pedrosa, E.G.G.; Buitrago, M.J.; Vélez, L.R. Acute Pulmonary Paracoccidioidomycosis in a Traveler to Mexico. J. Travel. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.; Moertl, D.; Eckhardt, A.; Sagel, U.; Wrba, F.; Dam, K.; Willinger, B. Chronic Paracoccidioidomycosis with adrenal involvement mimicking tuberculosis—A case report from Austria. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2016, 14, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, A.; Kirchmair, M.; Rainer, J.; Rossi, R.; Kreczy, A.; Tintelnot, K.; Dierich, M.P.; Flörl, L.C. Chronic paracoccidioidomycosis in a female patient in Austria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004, 23, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanov, K.; Balabanoff, V.A.; Angelov, N. South American Blastomycosis in a Bulgarian Laborer Returning after 30 Years in Brazil. Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 1964, 24, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, M.; Rickerts, V.; Drick, N.; Gerkrath, J.; Kreipe, H.; Soudah, B.; Welte, T.; Suhling, H. Chronic progressive pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis in a female immigrant from Venezuela. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2019, 13, 4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevogt, H.; Tintelnot, K.; Seybold, J.; Suttorp, N. Lymphadenopathy in a pregnant woman from Brazil. Lancet 2004, 363, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horré, R.; Schumacher, G.; Alpers, K.; Seitz, H.M.; Adler, S.; Lemmer, K.; De Hoog, G.S.; Schaal, K.P.; Tintelnot, K. A case of imported paracoccidioidomycosis in a German legionnaire. Med. Mycol. 2002, 40, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kohler, C.; Klotz, M.; Daus, H.; Schwarze, G.; Dette, S. Visceral paracoccidioidomycosis in a gold-digger from Brasil. Mycoses 1988, 31, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveling, F. Paracoccidioidomycosis infections caused by an adventure vacation in the Amazon. Prax. Klin. Pneumol. 1988, 42, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brauninger, W.; Hastra, K.; Rubin, R. Paracoccidioidomycosis, an imported tropical disease. Hautarzt 1985, 36, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hastra, K.; Schulz, V.; Brauninger, A. South American blastomycosis in the Federal Republic of Germany. Prax. Klin. Pneumol. 1985, 39, 905. [Google Scholar]

- Altmeyer, P. A contribution to South American blastomycosis Blastomyces brasiliensis. Mykosen 1976, 19, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Silva, A.; Cruz, M.; Sabino, R.; Veríssimo, C. Labial lesion in a Portuguese man returned from Brazil-The role of molecular diagnosis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 22, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, H.; Vaz De Castro, J.; Brito, D.; Oliveira Neta, J.; Aleixo, M.J.; André, C.; Antunes, L.; Brito, M.J. A case of imported paracoccidioidomycosis. Virchows Arch. 2013, 463, 170–171. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, R.; Marote, J.; Armas, M.; Freitas, C.; Almeida, L.S.; Sequeira, H.; Gomes, M.A.; Verissimo, C.; Rosado, M.L.; Faria, A. Paracoccidioidiomycosis: Case report. Med. Cutanea Ibero Lat. Am. 2013, 41, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Armas, M.; Ruivo, C.; Alves, R.; Gonçalves, M.; Teixeira, L. Pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis: A case report with high-resolution computed tomography findings. Rev. Port. Pneumol. 2012, 18, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.; Branquinho, F.; Theias, R.; Perloiro, M. Paracoccidiodomicose Brasiliensis: A propósito de um caso clínico. Rev. Soc. Port. Med. Int. 2009, 16, 170–172. [Google Scholar]

- Villar, T.; Neves, H.; Soares, N.; Duarte, S. Blastomicose sul-americana. Forma mista, cutâneo-mucosa e pulmonar. J. Médico 1963, 51, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveria, H.; Baptista, A. Um caso de blastomicosis Sudamericana (23 anos in Cubacao. A cao de sulfametoxipiridoxina). Coimbra Med. 1960, 7, 661. [Google Scholar]

- Navascués, A.; Rubio, M.T.; Monzón, F.J. Paracoccidioidomycosis in an Ecuadorian immigrant. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2013, 31, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, M.J.; Martínez, B.L.; Castelli, M.V.; Tudela, R.J.L.; Estrella, C.M. Histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis in a non-endemic area: A review of cases and diagnosis. J. Travel Med. 2011, 18, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riqué, P.M.; Ruiz, S.; Tarrés, A.C.; Cañete, C. Pulmonary mycosis caused by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: Dangerous confusion with sarcoidosis. Radiologia 2011, 53, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivencia, R.G.; Rubio, R.O.; González, R.P.; Herrero, D.M.; Puente, P.S. Paracoccidioidomycosis in a Spanish missionary. J. Travel Med. 2010, 17, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Velasco, B.M.; Diaz, J.F.; de la Duccase, O.T.V.; García, M.C. Imported paracoccidioidomycosis in Spain. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2010, 28, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayayo, E.; Aracil, G.V.; Torres, F.B.; Mayayo, R.; Domínguez, M. Report of an imported cutaneous disseminated case of paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2007, 24, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.J.; Perez, B.J.J.; Quintairos, S.C.; Pestonit, C.M. Infection by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in an immigrant from Venezuela. Med. Clin. (Barc) 2005, 125, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginarte, M.; Pereiro, M., Jr.; Toribio, J. Imported paracoccidioidomycosis in Spain. Mycoses 2003, 46, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustínduy, G.M.; Guimerá, F.; Arévalo, P.; Castro, C.; Sáez, M.; Alom, D.S.; Noda, A.; Flores, D.L.; Montelongo, G.R. Cutaneous primary paracoccidioidomycosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2000, 14, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, J.; Almagro, M.; Pereiro, M.; Martinez, W.; Arnal, F.; Silva, G.J.; Fonseca, E. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Report of a case imported into spain. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. 1998, 89, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- García, A.; Suárez, M.M.; Gándara, J.M.; Pereiro, M., Jr.; Pardo, F.; Diz, P. Importación de paracoccidioidomicosis a España por un emigrante gallego en Venezuela. Med. Oral 1997, 2, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pereiro, M., Jr.; Pereiro, M.; Garcia, A.G.; Toribio, J. Immunological features of chronic adult paracoccidioidomycosis: Report of a case treated with fluconazole. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1996, 76, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miguens, P.M.; Nunez, V.R.; Nunez, S.J.M. Blastomicosis sudamericana. Rev. Med. Galicia 1972, 10, 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- De Cordova, J.; Richards, O.; Southall, P.; Muscat, I.; Siodlak, M. First reported case of Paracoccidiodomicosis in Great Britain. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2012, 37, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, R.; Houston, A.; Appleton, M.; Lucas, S.; Legg, J. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, an undeclared import. J. Infect. 2011, 63, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.L.; Pembroke, A.C.; Lucas, S.B.; Lopez, V.F. Paracoccidioidomycosis presenting in the U.K. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, S.; Woodcock, A.; Da Costa, P.; Warwick, T.M. Chronic pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis masquerading as lymphangitis carcinomatosa. Thorax 1986, 41, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Symmers, W.S. Deep-seated fungal infections currently seen in the histopathologic service of a medical school laboratory in Britain. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 46, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgia, G.; Reynaud, L.; Cerini, R.; Ciampi, R.; Schioppa, O.; Dello Russo, M.; Gentile, I.; Piazza, M. A case of paracoccidioidomycosis: Experience with long-term therapy. Infection 2000, 28, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Solaroli, C.; Alol, F.; Becchis, G.; Zina, A.; Pippione, M. Paracoceidioidomycosis. Description of a case. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 1998, 133, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fulciniti, F.; Troncone, G.; Fazioli, F.; Vetrani, A.; Zeppa, P.; Manco, A.; Palombini, L. Osteomyelitis by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (south american blastomycosis): Cytologic diagnosis on fine-needle aspiration biopsy smears: A case report. Diagn. Cytopathol. 1996, 15, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A.; Capra, R.; Di Gregorio, A.; Garavaldi, G. On one case of South American Blastomycosis with peculiar evolution. Riv. Patol. Clin. Tuberc. Pneumol. 1985, 56, 453–472. [Google Scholar]

- Benoldi, D.; Alinovi, A.; Pezzarossa, E. Paracoccidioidomycosis (South American blastomycosis): A report of an imported case previously diagnosed as tuberculosis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 1, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finzi, F.F.; Bubola, D.; Lasagni, A. Blastomicosi sudamericana. Ann. Ital. Dermatol. Clin. Sper. 1980, 34, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Velluti, G.; Mazzoni, A.; Kaufman, L.; Covi, M. Physiopathological, clinical and therapeutical notes on a case of paracoccidioidomycosis. Gazz. Med. Ital. 1979, 138, 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lasagni, A.; Innocenti, M. Su un caso di blastomicosi sud americana. Chemioter. Antimicrob. 1979, 2, 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa, C.; Nini, G.; Gualdi, G. Clinico-radiological contribution to the study of paracoccidioidomycosis. Minerva Dermatol. 1965, 40, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schiraldi, O.; Grimaldi, N. Granulomatosi paracoccidioide. Policlinico 1963, 70, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Molese, A.; Pagano, A.; Pane, A.; Vingiani, A. Case of paracoccidioidal granulomatosis; Lutz-Splendore-Almeida disease. Riforma Med. 1956, 70, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Farris, G. Report on a case of paracoccidioidomycosis (so-called Brazilian blastomycosis). Atti della Società italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia e delle sezioni interprovinciali. Soc. Ital. Dermatol. Sifilogr. 1955, 96, 321–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaccini, G. Contributo allo studio della cosi detta ≪blastomicosa sud-americana≫. Giorn. Ital. Dermatol. Sifil. 1934, 75, 783–828. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Favera, G.B. Per la conoscenza della cosidetta blastomicosi cutanea (con un’osservazione personale di oidiomicosi (Gilchrist, Bushke) zimonematosi (de Beurmann et Gougerot). Giorn. Ital. Mal. Ven. Pelle 1914, 55, 650–729. [Google Scholar]

- Heleine, M.; Blaizot, R.; Cissé, H.; Labaudinière, A.; Guerin, M.; Demar, M.; Blanchet, D.; Couppie, P. A case of disseminated paracoccidioidomycosis associated with cutaneous lobomycosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e18–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, J.; Chanson, N.; Charlier, C.; Bonnal, C.; Jouvion, G.; Goulenok, T.; Papo, T.; Sacre, K. A 54-Year-Old Man with Lingual Granuloma and Multiple Pulmonary Excavated Nodules. Chest 2017, 151, e13–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sambourg, E.; Demar, M.; Simon, S.; Blanchet, D.; Dufour, J.; Marie, S.D.; Fior, A.; Carme, B.; Aznar, C.; Couppie, P. Paracoccidioidomycosis of the external ear. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 141, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laccourreye, O.; Mirghani, H.; Brasnu, D.; Badoual, C. Imported acute and isolated glottic paracoccidioidomycosis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2010, 119, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, D.M.; Heitzmann, A.; Mille, C.; Muckensturm, B.; Dromer, F.; Dupont, B.; Hocqueloux, L. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in a brain abscess: First French case. J. Mycol. Med. 2007, 17, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, P.A.; Bierenbroodspot, F.; Telgt, D.S.C.; Kwakman, J.M.; De Wilde, P.C.M.; Meis, J.F.G.M. A case of imported paracoccidioidomycosis: An awkward infection in the Netherlands. Med. Mycol. 2006, 44, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maehlen, J.; Strøm, E.H.; Gerlyng, P.; Heger, B.H.; Orderud, W.J.; Syversen, G.; Solgaard, T. South American blastomycosis--a differential diagnosis to tuberculous meningitis. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforening 2001, 121, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stanisic, M.; Wegmann, T.; Kuhn, E. South American blastomycosis (paracoccidioidomycosis) in Switzerland. Clinical course and morphological findings in a case following long-term therapy. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1979, 109, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wegmann, T.; Zollinger, H.U. Tuberkuloide Granulome in Mundschleimhaut und Halslymphknoten: Sudamerikanische Blastomykose. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1959, 89, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifaz, A.; González, V.D.; Ortiz, P.A.M. Endemic systemic mycoses: Coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. 2011, 9, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitrago, M.J.; Estrella, C.M. Current epidemiology and laboratory diagnosis of endemic mycoses in Spain. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, Q.R.; Tde, G.A.; Massucio, R.A.; De Capitani, E.M.; Sde, R.M.; Balthazar, A.B. Association between paracoccidioidomycosis and tuberculosis: Reality and misdiagnosis. J. Bras. Pneumol. Publicacao Soc. Bras. Pneumol. Tisilogia 2007, 33, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, Q.F.V.; Pietrobom, P.P.M.; Júnior, R.M.; Baptista, R.M.; Peçanha, P.M. New Insights on Pulmonary Paracoccidioidomycosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, C.; Pinto, A.; Tortora, G.; Ginolfi, F. South American blastomycosis of the lung and bone: A case report. Radiol. Med. 1998, 95, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buitrago, M.J.; Merino, P.; Puente, S.; Lopez, G.A.; Arribi, A.; Oliveira, Z.R.M.; Gutierrez, M.C.; Tudela, R.J.L.; Estrella, C.M. Utility of Real-time PCR for the detection of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis DNA in the diagnosis of imported paracoccidioidomycosis. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).