Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and hyperspectral imaging (HSI) provide complementary information for image-guided neurosurgery, combining high-resolution anatomical detail with tissue-specific optical characterization. This work presents a novel multimodal phantom dataset specifically designed for MRI–HSI integration. The phantoms reproduce a three-layer tissue structure comprising white matter, gray matter, tumor, and superficial blood vessels, using agar-based compositions that mimic MRI contrasts of the rat brain while providing consistent hyperspectral signatures. The dataset includes two designs of phantoms with MRI, HSI, RGB-D, and tracking acquisitions, along with pixel-wise labels and corresponding 3D models, comprising 13 phantoms in total. The dataset facilitates the evaluation of registration, segmentation, and classification algorithms, as well as depth estimation, multimodal fusion, and tracking-to-camera calibration procedures. By providing reproducible, labeled multimodal data, these phantoms reduce the need for animal experiments in preclinical imaging research and serve as a versatile benchmark for MRI–HSI integration and other multimodal imaging studies.

DataSet License: CC-BY 4.0

1. Summary

In neurosurgery, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a well-known standard for image guidance; however, it only provides basic structural information. Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) can provide complementary insights [1,2,3,4,5,6], offering detailed anatomical information along with tissue-specific material properties. The integration of HSI can improve tumor localization and intraoperative guidance, but progress is limited by the lack of publicly available datasets with both modalities acquired from the same specimen with precise spatial correspondence. Acquiring such paired data in clinical settings is challenging due to tissue deformation, inter-subject variability, and practical or ethical constraints. Phantoms offer a controlled, reproducible solution, enabling the generation of multimodal data with known geometry and facilitating the evaluation of registration, segmentation, and classification algorithms [7,8,9,10]. However, most existing multimodal brain phantoms focus on MRI, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound (US) and positron emission tomography (PET) acquisition [11,12]. Furthermore, synthetic phantoms adhere to the 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement), reducing the need for animal experiments in preclinical research.

In this work, a novel multimodal phantom dataset specifically designed for MRI–HSI integration is presented. The phantoms reproduce a three-layer structure containing white matter, gray matter, tumor tissue, and superficial blood vessels, using agar-based compositions chosen to achieve similar MRI contrasts comparable to those of the rat brain [13] and stable hyperspectral signatures. Two phantom designs were developed to enable precise multimodal registration through fiducial markers and controlled geometry. The dataset includes MRI, HSI, RGB-D, and tracking acquisitions, together with pixel-wise labels and corresponding 3D models. In total, 13 phantoms were created, distributed across two versions (Phantom v1 and Phantom v2) that emulate different brain tissue characteristics. Both datasets share several key characteristics:

- Extended registration methodology. Each phantom design provides at least one complete pipeline for registering all imaging modalities. In Phantom v1, registration relies exclusively on the tracking system, using camera calibrations and fiducial landmarks to align the MRI, HSI, RGB-D data, and the 3D model. In Phantom v2, the workflow is extended by enabling direct MRI-to-tracking registration through points sampled on the phantom and by adding ArUco markers that allow direct registration between the HSI camera and the 3D model. These complementary pathways reduce cumulative error and allow benchmarking of different multimodal registration strategies.

- Diversity of the data. The phantoms incorporate several agar concentrations, each fully characterized by MRI relaxation times and hyperspectral signatures. This variability mimics inter-patient differences in tissue composition and optical response. Furthermore, the arrangement of tissue layers is intentionally alternated between phantoms (normal and inverted configurations) to prevent learning-based methods from relying solely on fixed structural patterns, thus encouraging more robust segmentation and classification models.

- Usability across research domains. Beyond the core MRI and HSI modalities, the dataset includes multi-camera RGB and depth acquisitions from different sensor technologies (stereo, time-of-flight), extending its applicability to several research directions, including depth estimation from stereo image pairs; MRI segmentation benchmarking with HSI-based validation; standalone HSI classification tasks; multimodal fusion experiments; registration between MRI volumes and 3D container phantom models using surface geometry; and evaluation of tracking-to-camera calibration procedures. This makes the dataset a versatile benchmark for a wide range of multimodal imaging and registration challenges, not limited to MRI–HSI fusion.

The remainder of the manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data included in the dataset and the acquisition equipment. Section 3 details the design, fabrication, and acquisition procedures of the phantoms, as well as the labeling strategy and the MRI/HSI validation. Finally, Section 4 presents a description of the provided code for loading and handling the dataset, followed by an example of multimodal registration on one of the phantoms, and a discussion of potential research applications.

2. Data Description

The proposed dataset is composed of 13 phantoms that mimic the behavior of different tissues in the brain, divided into two versions, hereafter referred to as Phantom v1 and Phantom v2. These phantoms were built from scratch and captured using two different medical acquisition systems: an MRI system and an HSI camera. In addition, the dataset includes information to test different registration approaches between images modalities.

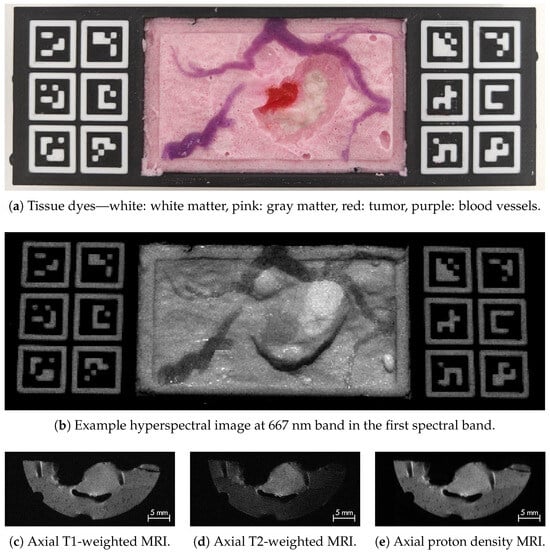

Each phantom consists of four tissue types: gray matter, white matter, tumor, and blood vessels, created with varying agar concentrations for distinct MRI contrasts and different dyes for spectral differentiation in HSI. Figure 1 shows an overview across modalities. An example RGB image is shown in Figure 1a (top row), where gray matter is tinted white and pink, white matter white, tumor red, and blood vessels purple. The resulting HSI appearance is in Figure 1b (middle row), with clear contrast differences at 667 nm in the first spectral band. MRI acquisitions include T1-, T2-weighted, and proton density sequences (Figure 1c–e in the bottom row). To simulate tumor resection, phantoms were modified to expose the tumor and underlying tissue layers; Phantom v1 was acquired before and after resection, whereas Phantom v2 includes only post-resection data.

Figure 1.

Overview of Phantom v2 (phantom 1) imaging modalities. Top row (a): RGB photography of the phantom showing clearly identifiable tissue types. Middle row (b): hyperspectral image example at the first spectral band highlighting contrast between tissues. Bottom row: MRI examples for (c) T1, (d) T2, and (e) DP sequences where the tumor appears as the central high-contrast region.

The dataset was acquired using a Ximea Snapshot V2 hyperspectral camera [14] capturing 24 spectral bands (665–950 nm) and a 9.4T preclinical MRI system [15]. RGB and depth images, as well as tracking data from an OptiTrack system [16], were also collected to enable cross-modality registration. While some equipment varied between phantom versions, MRI and hyperspectral imaging were consistently included. Table 1 summarizes the acquisitions for each phantom version.

Table 1.

Summary of the dataset modalities, acquisition systems, resolutions, and number of images per phantom. For Phantom v1, each of the five phantoms was imaged before and after simulated tumor resection, while in the eight for Phantom v2, only the resected phantoms were acquired. The table details RGB/Depth, HSI, MRI, and tracking data for each version.

Dataset Organization

The dataset includes five phantoms from the Phantom v1 setup and eight phantoms from the Phantom v2 setup. Each phantom contains the following folder hierarchy:

- 3D_models: 3D models used to build the phantom.

- Depth: Data captured by the RGB and depth cameras used for each phantom. Each camera has its own subfolder with the following structure:

- –

- captures: Includes the images acquired by the camera in .bin format. Depending on the camera type, the files may include color.bin, depth.bin, left.bin, right.bin (for stereo cameras), and color.bin, depth.bin, ir.bin (for time-of-flight cameras).

- *

- captures_metadata.json: Provides interpretability information about each image, including shape, data size, and number of channels.

- *

- optitrack_metadata.json: Contains tracking system information for the camera, including the last quaternion (q), position (t), rotation–translation matrix (RT), and a buffer with the last 15 RT matrices (RT_buffer).

- –

- cam_params.json: Contains the optical parameters of each sensor, including the intrinsic matrix (k), distortion coefficients (dist), homography matrices relating sensors (H), rotation matrix (R), and translation vector (t) composing H, as well as the resolution at which the calibration was performed using the DLR CalLab framework (German Aerospace Center) [17].

- –

- optitrack_calibration.json: Calibration matrix (E) relating the RGB camera optical center with the tracking system, and matrix G, which relates the chessboard with the tracking system. These matrices are required for the calibration process detailed in [18].

- HSI: Contains the hyperspectral acquisitions. To ensure robust tissue characterization, each scene was captured with eight different exposure times.

- –

- captures: Includes the raw hyperspectral images in .bin format with the naming convention raw_[t_exp]_ms.bin, where exposure times (t_exp) are 20, 40, 70, 90, 100, 120, 150, and 200 ms. This folder also includes captures_metadata.json and optitrack_metadata.json.

- –

- wb: Contains the white-balance images of a homogeneous surface, used to compute reflectance. Files follow the same naming convention as the captures.

- –

- hypercubes: Contains the reflectance hypercubes obtained after preprocessing the raw data [19]. Files follow the format hypercube_[t_exp]_ms.bin. This folder also contains the corresponding ground-truth labels in labelled_cube.png.

- –

- cam_params.json and optitrack_calibration.json: Provide the same information as in the Depth folder.

- MRI: MRI slices for different modalities and orientations.

- –

- T1w, T2w and PD:

- *

- Axial: Axial MRI slices in DICOM format.

- *

- Coronal: Coronal MRI slices in DICOM format.

- –

- labels: Contains the ground-truth for the labeled slices.

- Register: Contains information from the digitizing probe of the tracking system used to record the fiducial markers of the phantom.

- –

- optitrack_points_[n].json: Stores the positions of the landmarks embedded in the phantom 3D models. The index n corresponds to repeated registrations of the same markers.

- –

- optitrack_points_mri.json: Contains the positions of points manually touched on the phantom surface to register the MRI directly with the tracking system. This file is only available in the Phantom v2 dataset.

3. Methods

3.1. Phantom Design

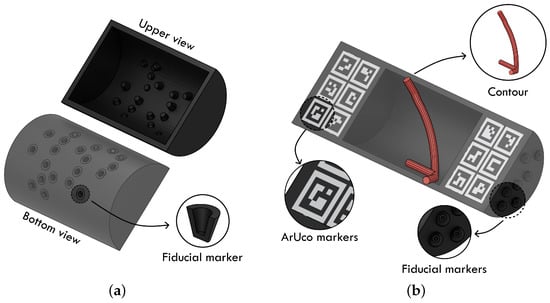

The construction of the phantoms begins with the design of the container. These containers must not only fit within the dimensions of the MRI coil to allow for image acquisition, but must also incorporate fiducial markers that enable registration between the MRI data and the other modalities, particularly the HSI images. The Phantom v1 and v2 setups employ different container designs tailored to their respective registration techniques.

In Phantom v1, registration relies exclusively on the optical tracking system through fiducial markers located on the outer surface of the container. These fiducial markers are cones distributed along the bottom part of the container. These cavities appear as empty regions in the MRI, allowing the tracking probe to reach them from behind. These cones, therefore, serve a dual purpose: they act as fiducial markers for registering the 3D model with the tracking system, and they enable alignment between the MRI and the 3D model. This design is illustrated in Figure 2a.

Figure 2.

Phantom containers design for the two versions of the phantom. (a) Phantom v1 container design; (b) Phantom v2 container design.

In contrast, Phantom v2 separates these tasks to reduce cumulative registration errors. In this design, ArUco markers are directly printed on the container surface to enable the camera to model registration, while the contour of the inner cavity of the container, intentionally designed with a non-symmetrical shape, provides a reliable geometric feature for registering the MRI volume with the 3D model (Figure 2b). The fiducial markers of the 3D model are placed along the lateral surface of the phantom, making them easier to access with the tracking probe during acquisition, unlike Phantom v1, where they were positioned at the back of the container.

The containers were filled with agar of different concentrations to simulate different tissue types. The use of agar as a base material for brain phantom tissue is well established in the literature [11,12]. The selection of the agar concentration for each tissue type was based on the typical T1 and T2 relaxation times of brain tissues acquired at 9.4 T. To approximate these values, several agar concentrations were tested to mimic the corresponding MRI signal behavior. Reference relaxation times were obtained from [8,13] where values are reported at 4.0 T, 9.4 T, and 11.7 T, showing higher signal and contrast at lower fields but maintaining the differences of relaxation times among tissues. The values measured at 9.4 T from the phantoms are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

T1 and T2 relaxation times for the different phantom tissues.

To keep the phantoms easy to manufacture and cost-effective, only agar was used as the base material. This constraint makes it difficult to reproduce the exact T1 and T2 times reported in the literature. For the tumor tissue, the goal was to ensure a clear visual distinction in MRI, simulating the effect of a contrast-enhanced image. Thus, its agar concentration was selected to strongly differentiate it from the surrounding tissue, specifically in T2-weighted images. For the blood vessels, a high agar concentration was used to minimize their visibility in MRI. However, concentrations above 6% were avoided because the material dries too quickly and becomes impractical to work with.

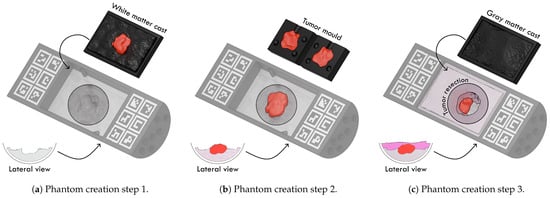

3.2. Phantom Creation

To create each phantom, the container is filled with the corresponding agar concentration and colorants. Each layer is allowed to solidify using a 3D-printed mold that prevents the surface from becoming completely smooth. The process of building the phantoms is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Phantom creation steps. (a) The process begins by pouring the liquid agar solution into the container and covering it with the white-matter cast, which includes a negative imprint of the tumor to allocate space for it in the next step. (b) The tumor layer is then created by pouring agar into a dedicated mold with the tumor shape; once solidified, this tumor piece is placed into the reserved cavity of the first layer. (c) After fixing the tumor in place, the final agar solution is poured and covered with the gray-matter cast to form the outer layer. Once all layers have solidified, a simulated tumor resection is performed to expose internal structures for camera acquisition and the blood vessels are deposited on the surface.

The tissues are arranged sequentially: the process begins with the white-matter layer, followed by the gray-matter layer poured on top to enclose it. The tumor is embedded between both layers. To increase variability, the positions of the white-matter and gray-matter layers were alternated, while the tumor remained consistently at the center and the blood vessels on the top layer. These two configurations are referred to as normal and inverted phantoms, respectively. The Phantom v1 setup includes five normal phantoms, whereas the Phantom v2 setup includes three normal and five inverted phantoms.

3.3. Data Acquisition

Before data acquisition, several calibration steps must be performed: (i) intrinsic calibration, (ii) extrinsic calibration, and (iii) camera-tracking-system calibration. First, intrinsic calibration is required for each image sensor of every camera. If a camera contains more than one sensor, the extrinsic parameters between them must also be estimated to determine their relative poses, which was performed using the DLR CalLab framework (German Aerospace Center) [17]. Once all intrinsic and extrinsic parameters are known, each camera must be integrated into the tracking system through a dedicated calibration procedure [18]. For the RGBD cameras, the RGB sensor was used as the reference to integrate the camera into the tracking system, while the depth information was incorporated via the extrinsic parameters between the RGB and depth sensors.

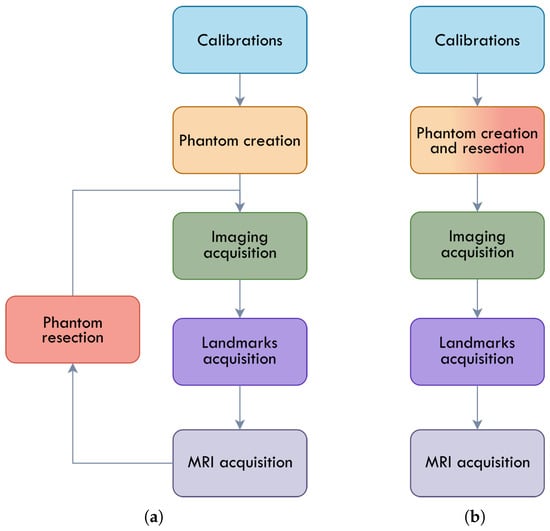

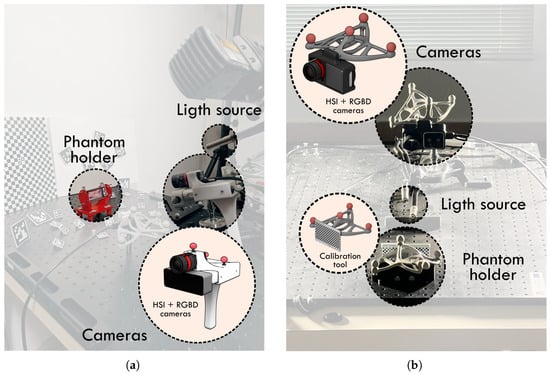

In Phantom v1, the hyperspectral camera was introduced into the tracking system through the Azure Kinect RGB camera, using the extrinsic parameters between the two devices, which remained stable due to the rigid, 3D-printed mounting structure. In Phantom v2, the calibration workflow was modified to allow for the direct integration of the hyperspectral camera into the tracking system, eliminating any dependency on other cameras. The methodology used to acquire the data also differs among the phantom versions as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Phantom acquisition flowcharts. (a) Phantom v1 acquisition flowchart; (b) Phantom v2 acquisition flowchart.

In the Phantom v1 setup, once each phantom was created, the first step consisted of fixing it onto a dedicated acquisition support designed to rigidly hold the phantom and prevent any displacement during data collection (Figure 5a, red structure). After securing the phantom, the acquisition procedure began with hyperspectral imaging using the specific illumination required for this modality, which was provided by a halogen lamp. Once all exposure times were captured, the illumination was switched to LED spotlights to enable the acquisition of RGB and depth images (imaging acquisition step in Figure 4a).

Figure 5.

Phantom acquisition setups. (a) Phantom v1 setup; (b) Phantom v2 setup.

After all camera data was collected, a manual registration procedure was performed (landmarks acquisition step in Figure 4a). This involved recording the position of the tracking system probe each time a fiducial marker on the container was touched; this process was repeated three times for robustness. With the optical and hyperspectral data acquired, the phantom was then moved to the MRI system (MRI acquisition stage in Figure 4a), where the different MRI modalities were collected using the configuration depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

MRI sequences configuration employed for the different image modalities.

After the MRI acquisition, a simulated tumor resection was carried out on the agar phantom to expose the tumor and white-matter layers, allowing them to be visible to the cameras. The complete acquisition procedure, including all camera modalities and manual registration, was then repeated for the resected phantom as represented in Figure 4a.

In the Phantom v2 setup, the procedure was streamlined to reduce total acquisition time and minimize the drying of the agar, which could otherwise alter the MRI and HSI signal characteristics. In this version, a resection was performed immediately after the phantom was completed (fused step in Figure 4b), and the resected phantom was then fixed onto the acquisition setup (Figure 5b). HSI images and RGBD images from the Intel D405 were acquired following the same illumination change protocol as in v1.

Next, as in Phantom v1, the fiducial markers were touched three times with the tracking system probe. Additionally, in Phantom v2, the volume of the phantom itself was sampled at random locations with the probe, enabling direct registration of the MRI with the tracking system and avoiding the need for registration through the 3D-model contour (landmarks acquisition step in Figure 4b). Once all optical and tracking data were collected, the phantom was scanned in the MRI system to obtain the different MRI sequences (MRI acquisition stage in Figure 4a).

3.4. Data Labeling

All phantoms included in the dataset are labeled in both MRI and HSI modalities to enable the training of algorithms using the provided data. The MRI annotations were generated using Label Studio [20] in combination with the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [21] to streamline the initial labeling process. The first four phantoms from the Phantom v1 setup (only the non resected phantoms) were labeled using this framework, providing a base dataset for training a neural network to assist in labeling the remaining samples.

A ConvNeXt model [22] was trained on these initial annotations and was subsequently used to generate preliminary labels for the rest of the Phantom v1 and v2 datasets. To enable the use of this network with MRI data, a three-channel image was constructed for each slice by stacking the T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and PD images. This strategy not only allows the network to operate on non-RGB data but also reduces the number of images requiring manual labeling while ensuring perfect alignment between MRI modalities.

Using the automatically generated labels as an initial approximation, and with the support of a custom web-based annotation interface (provided as a Docker package within the dataset), the remaining segmentations were iteratively refined. After incorporating these refined annotations, the network was retrained and used again to relabel the full v2 dataset. This iterative, human-in-the-loop process was repeated until the majority of predictions were satisfactory. Once convergence was achieved, all segmentations were reviewed, and any incorrectly classified regions were manually corrected. The final MRI labels include white matter, gray matter, tumor, and background, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Illustrated example of labels of Phantom v2 (Phantom 1), axial slice number 21, overlaid on the combined T1, T2, and PD images. Tissue classes are overlapped with color coded as follows: dark gray for background, light gray for gray matter, blue for white matter, and red for tumor tissue.

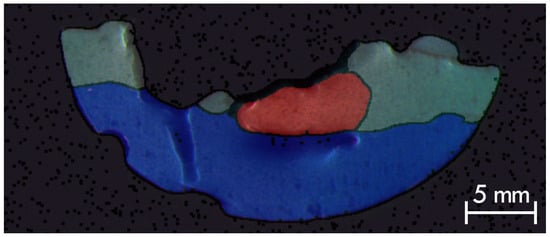

For the HSI images, a fully manual labeling procedure was adopted. The annotation process relied on both spatial and spectral information. A reference pixel was first selected using the first spectral band for visual guidance. The spectral signature of this pixel was then used to search for similar pixels within the hypercube, using the L2 distance metric. A threshold was adapted for each class to ensure that only pixels with similar spectral behavior were selected. After selecting the appropriate threshold, a region of interest was manually defined to avoid contamination from other classes. This procedure was repeated for each of the following classes: healthy tissue (including both white and gray matter), tumor, and blood vessels, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

HSI image of Phantom v2 (Phantom 1) with overlaid labels indicating tissue classes: green represents healthy tissue, blue represents blood vessels, and red represents tumor tissue.

Additionally, Table 4 provides a summary of the labels for each image modality. While the labels shown are those directly provided in the dataset, users can combine or reinterpret them depending on the specific task. For instance, in a classification task, white and gray matter in HSI images or MRI slices could be merged as a single “healthy” class when the primary objective is to identify tumoral tissue, as indicated in Table 4. Similarly, blood vessels can also be considered part of the healthy class in a binary classification scenario where only the tumor is the target.

Table 4.

Labels for the different image modalities and combination suggestion.

It is important to note that, although care was taken to minimize bias, the labeling procedure was performed or supervised manually, so some natural variability in the labels may remain.

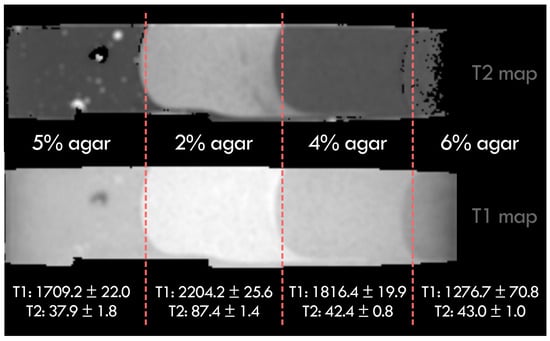

3.5. Data Validation

In order to validate the MRI data obtained for the different agar concentrations used in the phantoms, a small portion of the agar employed in the construction of several phantoms was set aside to extract the T1 and T2 relaxation times. This allowed the characterization of each concentration, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Measured T1 and T2 relaxation times for the different agar concentrations used in the phantoms.

The tumor-mimicking tissue (2% agar) exhibits high contrast relative to the other concentrations, facilitating its localization and enabling the evaluation of multimodal registration across the dataset. The 4% and 5% agar concentrations yield relaxation times close to those reported in the literature for gray and white matter, respectively [13].

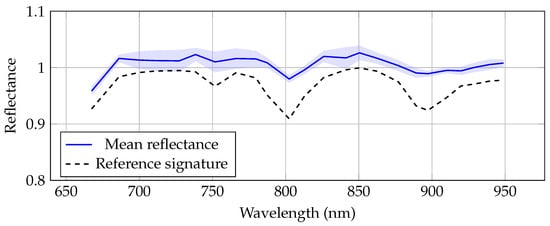

For the validation of hyperspectral imaging, a reference polymer with a known and well-characterized spectral signature was used to assess the quality and consistency of the measurements. Figure 9 shows the resulting spectral signatures, with the reference polymer depicted in black and the manufacturer-provided reference shown as a gray dotted line. The measured signature closely matches the reference, with a correlation of 87%. The observed variations may be caused by slight misalignment between the polymer sample and the white reference due to differences in shape and thickness.

Figure 9.

Mean spectral signature of the reference polymer obtained with the hyperspectral camera across different exposure times (solid blue line), with the shaded area representing the standard deviation. The dotted line shows the reference spectrum provided by the manufacturer.

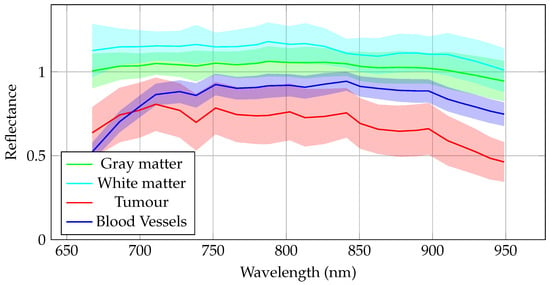

Furthermore, using the labeled hyperspectral images, the mean and standard deviation for each tissue class were computed across different exposure times in Phantom v2, as illustrated in Figure 10. The results show that the spectral signatures of the different tissues are distinct, making them suitable for use in classification algorithms. Since the primary application of hyperspectral images of these phantoms is tumor detection, the similarity between the white and gray matter signatures is intentional, allowing these tissues to be combined into a single healthy class for classification purposes, as done in the phantom labels.

Figure 10.

Mean spectral signatures for each class labeled in Phantom v2 across different exposure times. The solid line represents the mean value, and the shaded area indicates the standard deviation. Colors correspond to tissue types: gray matter (green), white matter (light blue), tumor (red), and blood vessels (blue).

4. Usage Notes

4.1. Code Availability

The dataset repository includes some scripts to facilitate the use of phantom data. The three main scripts are dataclass.py, loaders.py and utils.py. These scripts allow all dataset information to be easily accessed without manually parsing the .bin and .json files. In dataclass.py, different classes are defined for each image modality and for each type of capture. The main object is the Phantom, which contains as attributes other objects such as depth, mri, hsi, models, and register_points, along with metadata like names and file paths.

- For the depth data, each camera is represented as a Camera object that stores intrinsic and extrinsic parameters (the parsed information of the cam_params.json file), tracking information (position, rotation, and calibration), and the captured frames parsed from .bin files to NumPy arrays.

- The HSI data follow a similar structure, with the HSI object containing camera parameters, tracking information, and hyperspectral captures as NumPy arrays.

- MRI data are organized by orientation (axial and coronal) and by sequence (T1, T2, and PD), with each slice stored as a NumPy array. The slices are reconstructed into volumes using the DICOM metadata, including voxel spacing and origin.

- The 3D models are loaded from .stl or .ply files, enabling direct use in analysis or visualization. Finally, the register_points attribute provides access to the fiducial landmark positions collected using the tracking probe on the phantom containers or directly on the MRI volume.

All this information is loaded and processed using the loaders.py and utils.py scripts, which populate the classes and their attributes for easy and consistent access via NumPy arrays or Python 3.11 native objects (e.g., lists and dictionaries). By running loaders.py and specifying the path to a given phantom, a summary of the data contained in that phantom is automatically displayed in the terminal.

Additionally, a Docker image is provided containing the MRI labeling tool, which allows users to load MRI slices along with their labels, review them, and make corrections as needed in a web-based tool.

4.2. Usage Example

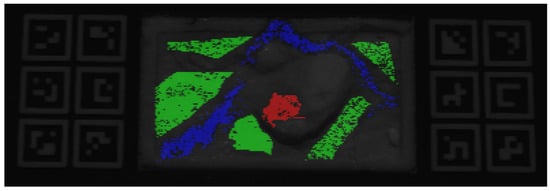

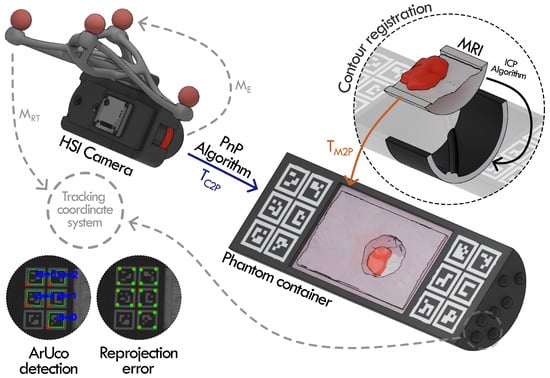

To register the multimodal information provided in the dataset, one of the approaches is to use only the HSI camera, the MRI, and the 3D model of the phantom container. A schematic representation of this process is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Registration procedure of Phantom v2 (Phantom 1). ArUco markers detected in the HSI image are matched with their known 3D positions in the phantom model to estimate the camera-phantom pose using PnP, illustrated by the reprojection error (green: detected points; red: reprojected points). The MRI is then aligned to the 3D model using contour-based registration of the container’s inner surfaces. Additional registration steps involved in the remaining methods are indicated by gray arrows.

The registration process begins by detecting the ArUco markers in the HSI image as shown in Figure 11. Since the 3D coordinates of the ArUco marker corners are known in the phantom container model, the relative pose between the HSI camera and the phantom can be estimated using the perspective-n-point (PnP) algorithm [23]. This transformation registers the phantom’s 3D model and the HSI capture in the same coordinate system ( transform in Figure 11).

Using this approach on Phantom v2 (Phantom 1), a mean reprojection error of 1.11 px is obtained between the detected ArUco marker corners in the HSI image and their corresponding coordinates in the 3D phantom model. When compared against the phantom container pose estimated from fiducial landmarks acquired with the tracking probe, the overall registration accuracy of this ArUco marker-based approach is mm.

To incorporate MRI information, the contour of the phantom visible in the MRI is matched with the corresponding contour of the 3D container model. These two contours are aligned using the iterative closest points (ICPs) algorithm [24], which is feasible because the container geometry is sufficiently distinctive (obtaining the transformation that relates the MRI volume to the phantom container, as shown in Figure 11). Once this alignment is achieved, the resulting multimodal registration is shown in Figure 12. The resulting mean fiducial registration error (FRE) after aligning the MRI volume contours to the 3D container model is 1.11 mm.

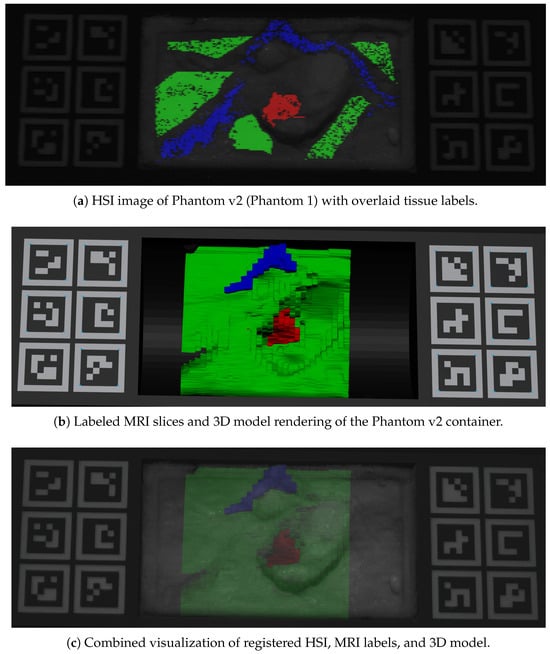

Figure 12.

Registration of Phantom v2 (Phantom 1) across imaging modalities. Panel (a) shows the hyperspectral image with tissue labels, where red denotes tumor, green healthy tissue, and blue blood vessels; (b) presents the MRI slices together with the phantom’s 3D container model; and (c) illustrates the multimodal fusion obtained after registration.

For reference, Figure 11 also indicates how the hyperspectral camera and the phantom container can be incorporated into the tracking coordinate system. The camera is integrated using the rigid transformation matrix provided by the tracking system ( matrix in Figure 11) and the E matrix included in the optitrack_calibration.json file in the camera folder, while the phantom container is registered using landmark points acquired with the tracked probe, which are provided in the dataset as optitrack_points_[n].json files.

As illustrated in the figure, the core element that enables multimodal registration is the 3D geometry of the phantom container. The HSI data (or any other camera modality) are registered to the 3D model using the ArUco markers. The MRI, whose voxelized labels follow the same color scheme as the HSI, is aligned with the model through the container contour, as shown in Figure 12b. Once these transformations are applied, the fused visualization of HSI, MRI, and the 3D container model is obtained, as depicted in Figure 12c. To qualitatively assess the accuracy of the registration, the tumor region and some blood vessels are highlighted, showing consistent overlap across modalities.

4.3. Potential Research Applications

Given the growing interest in multimodal imaging for brain tumor detection and the scarcity of publicly available datasets combining HSI and MRI in a controlled and precisely aligned manner, this dataset could provide a controlled scenario using phantoms for exploring the mutual benefits of both modalities. Potential applications include

- Evaluation of registration methodologies, including clinically inspired approaches using soft landmarks (e.g., patient face points), rigid fiducial landmarks (e.g., bone-based markers) and image-based approaches (e.g., skin-attached ArUco markers).

- Benchmarking data fusion strategies, for example, integrating HSI spectral information with MRI structural context to improve detection or classification.

- Investigation of non-rigid and deformable multimodal registration methods beyond the rigid baselines reported in this work, with performance quantitatively assessed using the provided annotations through segmentation overlap (e.g., DICE) and boundary-based metrics (e.g., ASD).

- Assessment of depth-sensing cameras in confined or small-incision scenarios, using the different depth acquisition systems incorporated in this study.

- Monte Carlo simulations of tissue optical properties, leveraging MRI volumetric information and HSI spectral data.

- Spectral unmixing and analysis, based on the known dyes and agar concentrations used to create the phantom tissues.

- Analysis of tracking system performance and accuracy, comparing different setups across the two dataset versions.

- Characterization of the optical properties of MRI phantom components other than agar using HSI data, following the construction and registration methodologies described in this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.; methodology, M.V., J.S., G.R.-O. and A.E.; software, M.V., G.R.-O., S.M.; validation, M.V., G.R.-O. and J.S.; resources, E.J. and S.M.; data curation, M.V., J.S. and A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V., J.S. and A.E.; writing—review and editing, M.V., J.S., A.E., G.R.-O., S.M. and E.J.; visualization, M.V.; supervision, E.J., J.S. and S.M.; project administration, E.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European project STRATUM under grant agreement no. 101137416.

Data Availability Statement

Data is public available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17830111.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the GAMMA research group at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Madrid, Spain) for providing access to the OptiTrack PrimeX 22 equipment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wołk, K.; Wołk, A. Hyperspectral Imaging System Applications in Healthcare. Electronics 2025, 14, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabelo, H.; Ortega, S.; Szolna, A.; Bulters, D.; Piñeiro, J.F.; Kabwama, S.; J-O’Shanahan, A.; Bulstrode, H.; Bisshopp, S.; Kiran, B.R.; et al. In-Vivo Hyperspectral Human Brain Image Database for Brain Cancer Detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 39098–39116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pérez, A.; Villa, M.; Rosa Olmeda, G.; Sancho, J.; Vazquez, G.; Urbanos, G.; Martinez de Ternero, A.; Chavarrías, M.; Jimenez-Roldan, L.; Perez-Nuñez, A.; et al. SLIMBRAIN database: A multimodal image database of in vivo human brains for tumour detection. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndu, H.; Sheikh-Akbari, A.; Deng, J.; Mporas, I. HyperVein: A Hyperspectral Image Dataset for Human Vein Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Fei, B. Medical hyperspectral imaging: A review. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 010901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studier-Fischer, A.; Seidlitz, S.; Sellner, J.; Bressan, M.; Özdemir, B.; Ayala, L.; Odenthal, J.; Knoedler, S.; Kowalewski, K.F.; Haney, C.M.; et al. HeiPorSPECTRAL - the Heidelberg Porcine HyperSPECTRAL Imaging Dataset of 20 Physiological Organs. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuff, H.; Chatelin, S.; Dillenseger, J.P. Narrative review of tissue-mimicking materials for MRI phantoms: Composition, fabrication, and relaxation properties. Radiography 2024, 30, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, A.; Georgiou, L.; Christodoulou, T.; Panayiotou, N.; Ioannides, C.; Zamboglou, N.; Damianou, C. MR relaxation times of agar-based tissue-mimicking phantoms. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2022, 23, e13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.J.; Gillies, G.T.; Broaddus, W.C.; Prabhu, S.S.; Fillmore, H.; Mitchell, R.M.; Corwin, F.D.; Fatouros, P.P. A realistic brain tissue phantom for intraparenchymal infusion studies. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 101, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntombela, L.; Adeleye, B.; Chetty, N. Low-cost fabrication of optical tissue phantoms for use in biomedical imaging. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crasto, N.; Kirubarajan, A.; Sussman, D. Anthropomorphic brain phantoms for use in MRI systems: A systematic review. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2022, 35, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Wu, T.; Wu, F.; Xiong, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, Q.; Liao, Y. Anthropomorphic Head MRI Phantoms: Technical Development, Brain Imaging Applications, and Future Prospects. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2025, 62, 1579–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, R.A.; Brown, P.B.; McIntyre, S.; Nixon, T.W.; Behar, K.L.; Rothman, D.L. High magnetic field water and metabolite proton T1 and T2 relaxation in rat brain in vivo. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 56, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ximea. IMEC SM Range 600–1000 USB3 Hyperspectral Camera. 2025. Available online: https://www.ximea.com/products/hyperspectral-imaging/xispec-hyperspectral-miniature-cameras/imec-sm-range-600-1000-usb3-hyperspectral-camera (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- MR-Solutions. MRS*PET/MR 9.4T Cryogen-Free Preclinical PET/MR Scanner. 2025. Available online: https://www.mrsolutions.com/molecular-imaging/molecular-imaging/pet-mr-cryogen-free/petmr-94t/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- NaturalPoint. Optitrack System. 2025. Available online: https://optitrack.com/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Strobl, K.H.; Hirzinger, G. More accurate pinhole camera calibration with imperfect planar target. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCV Workshops), Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Sancho, J.; Rosa-Olmeda, G.; Chavarrias, M.; Juarez, E.; Sanz, C. Benchmarking commercial depth sensors for intraoperative markerless registration in neurosurgery applications. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2025, 20, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Sancho, J.; Vazquez, G.; Rosa, G.; Urbanos, G.; Martin-Perez, A.; Sutradhar, P.; Salvador, R.; Chavarrías, M.; Lagares, A.; et al. Data-Type Assessment for Real-Time Hyperspectral Classification in Medical Imaging. In Proceedings of the Design and Architecture for Signal and Image Processing; Desnos, K., Pertuz, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko, M.; Malyuk, M.; Holmanyuk, A.; Liubimov, N. Label Studio: Data Labeling Software, 2020–2025. Open Source Software. Available online: https://github.com/HumanSignal/label-studio (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment Anything. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.02643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Terzakis, G.; Lourakis, M. A Consistently Fast and Globally Optimal Solution to the Perspective-n-Point Problem. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part I. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.V.; Haehnel, D.; Thrun, S. Generalized-ICP. In Robotics; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.