Abstract

Aquaculture monitoring increasingly relies on computer vision to evaluate fish behavior and welfare under farming conditions. This dataset was collected in a commercial recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) integrated with hydroponics in Queretaro, Mexico, to support the development of robust visual models for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). More than ten hours of underwater recordings were curated into 31 clips of 30 s each, a duration selected to balance representativeness of fish activity with a manageable size for annotation and training. Videos were captured using commercial action cameras at multiple resolutions (1920 × 1080 to 5312 × 4648 px), frame rates (24–60 fps), depths, and lighting configurations, reproducing real-world challenges such as turbidity, suspended solids, and variable illumination. For each recording, physicochemical parameters were measured, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen and turbidity, and are provided in a structured CSV file. In addition to the raw videos, the dataset includes 3520 extracted frames annotated using a polygon-based JSON format, enabling direct use for training object detection and behavior recognition models. This dual resource of unprocessed clips and annotated images enhances reproducibility, benchmarking, and comparative studies. By combining synchronized environmental data with annotated underwater imagery, the dataset contributes a non-invasive and versatile resource for advancing aquaculture monitoring through computer vision.

1. Introduction

Aquaculture has become one of the fastest-growing food production sectors worldwide, providing a major source of animal protein for human consumption [1,2]. As production intensifies, ensuring sustainability, efficiency, and fish welfare has emerged as a priority. Traditional monitoring approaches in aquaculture are largely manual, time-consuming, and prone to observer bias, which limits their capacity to detect stress, feeding behavior, or health issues in real time [3,4]. Recent advances in computer vision and machine learning have created new opportunities for automated, non-invasive monitoring of fish populations [5,6,7]. However, the development and validation of such methods are often constrained by the limited availability of datasets that capture the complexity of real-world rearing environments. Most publicly available fish datasets are generated under controlled laboratory conditions, which differ substantially from the turbidity, lighting variability, and suspended particles found in commercial aquaculture systems [8,9,10].

Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is among the most widely cultivated fish species due to its fast growth, resilience, and economic relevance [2]. Despite its global importance, there is a shortage of open datasets representing tilapia behavior under production-scale conditions. Furthermore, annotated datasets remain scarce, hindering progress in training and benchmarking vision models for behavior detection, tracking, and density estimation [8]. To address this gap, we present a dataset of underwater videos and annotated images of tilapia raised in a recirculating aquaponic system. In addition to video clips, the dataset includes synchronized physicochemical water parameters and 3520 annotated frames in LabelMe format. This combination provides a valuable foundation for developing and testing algorithms tailored to the realistic challenges of aquaculture environments.

Recent reviews have synthesized the rapid progress of computer-vision methods for aquaculture, including automatic recognition of fish feeding behavior, tracking, counting, and welfare-oriented monitoring in digital farms [4,7,9]. At the same time, surveys on underwater object detection and datasets emphasize both the growing number of marine benchmarks and the scarcity of resources that cover highly turbid, production-scale environments like those found in intensive recirculating aquaculture systems [8]. Complementary work on AI-based fish behavior recognition, calibration of video-based fish counts, and low-cost stereo camera deployments further illustrates how dataset design, imaging conditions, and sampling protocols directly affect ecological inference and monitoring performance [10,11,12]. Compared with these existing resources, our dataset focuses on Nile tilapia in a commercial aquaponic RAS and combines polygon-annotated underwater images with synchronized water-quality metadata under realistic levels of turbidity, lighting variability, and stocking density.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Site

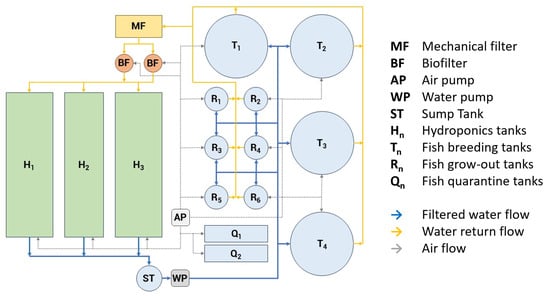

The dataset was collected at Granja la Familia Tilapia, a commercial facility located in Querétaro, Mexico (20.5551° N, 100.2561° W). The facility is located at an altitude of approximately 3360 m above sea level. The farm employs a recirculating aquaponic system that integrates tilapia farming with hydroponics in a semi-controlled environment (Figure 1). The system comprises four large tanks of 80,000 L and six smaller tanks of 8000 L, all hydraulically connected within greenhouse structures to ensure environmental stability. The cylindrical grow-out tanks considered in this study had an approximate water depth of 1.20 m. System components include mechanical filters for solids removal, biofilters for ammonia-to-nitrate conversion, aeration units, water pumps, and hydroponic grow beds. These features reproduce real aquaculture conditions, including organic waste, turbidity, and suspended particles that challenge underwater vision.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the recirculating aquaponic system (RAS) with rearing, solids removal, biofilters, aeration, pumps, and hydroponic grow beds; solid arrows indicate water flow, and dashed arrows indicate air flow.

All recordings were obtained from specific grow-out tanks within the commercial recirculating aquaponic system, containing Nile tilapia from a single production cohort at the grow-out phase (close to harvest size). At the time of video acquisition, fish in the selected tanks had relatively homogeneous body size, with individual body weights typically between 500 and 600 g. Stocking densities in the grow-out tanks were approximately 450–500 fish per tank, reflecting the farm’s routine operating conditions. Fish were clinically healthy, with no visible lesions or abnormal behavior, and were maintained under optimal husbandry conditions with a standard commercial diet. Focusing on this production stage is relevant because it concentrates the period when stocking densities are highest, feed inputs and oxygen demands are substantial, and welfare-related management decisions (e.g., feeding rate, aeration, and biomass estimation) have major economic impact. The relatively uniform morphology and size distribution of the fish also facilitates computer-vision tasks such as segmentation and tracking, reducing confounding effects due to strong ontogenetic changes in body shape.

2.2. Video Recording Protocol

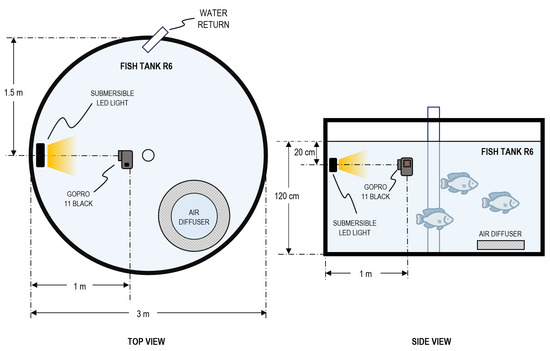

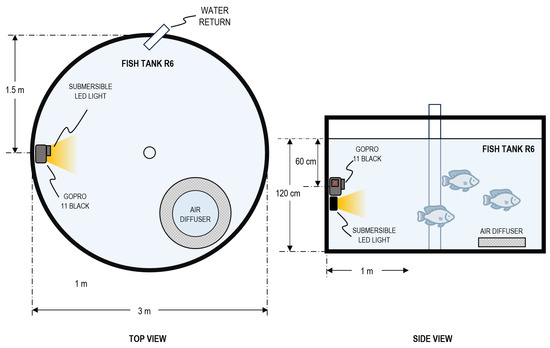

Recordings were conducted from 20 to 23 May 2024 during routine farm operations to minimize disturbance to fish behavior. To leverage natural illumination inside the greenhouse, acquisition took place between 11:00 and 16:00. Two camera deployments were used: center mounted, facing the tank walls (Figure 2), and wall mounted, facing the tank center (Figure 3). Camera depths ranged from 10 cm to 60 cm. Illumination was varied systematically across sessions using three conditions: no artificial light, frontal bar light, and back mounted bar light; the order of deployments and lighting configurations was randomized to evaluate which setup yielded the most reliable underwater imagery with the available resources. Each recording session lasted approximately 30 min, from which curated 30 s clips were extracted based on fish visibility and stocking density.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup of underwater video acquisition showing: center-mounted camera with backlight at 20 cm depth and 1.0 m camera–light distance.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup of underwater video acquisition showing: wall-mounted camera with front-mounted light, 60 cm depth.

Videos were recorded in MP4 container using HEVC/H.265 (high-resolution clips) and, where needed for compatibility, AVC/H.264. The GoPro HERO11 Black (GoPro, Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) supports 5.3K 8:7 (5312 × 4648); our clips span 1920 × 1080 to 5312 × 4648 at 24/30/60 fps. Lighting was configured as no light, frontal bar light, or back-mounted at a fixed camera-to-light distance of 1.0 m.

2.3. Data Acquisition Apparatus

Recordings were made with two GoPro HERO11 Black cameras housed in waterproof cases and mounted on adjustable bases to maintain underwater stability. The GoPro platform was selected for its broad availability, high native resolution, and documented applicability in ecological monitoring [11,12]. To control illumination, we used a submersible bar light with three LEDs, rated at approximately 300 lumens and a correlated color temperature of 5500–6000 K (daylight). The light was deployed in predefined configurations (frontal and back mounted) at a fixed camera-to-light distance of 1.0 m, enabling repeatable acquisition while preserving routine husbandry operations.

For environmental measurements:

- pH and temperature. A Hanna Instruments HI98129 (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) multiparameter tester was used exclusively for pH and temperature, with automatic temperature compensation (ATC) enabled. The pH channel was calibrated before each sampling session using NIST-traceable buffer solutions. The probe was rinsed with deionized water between measurements, and values were recorded immediately before each recording to maintain temporal alignment with the video data.

- Turbidity. Turbidity was measured with an HFBTE benchtop turbidimeter (range 0–200 NTU; minimum indication 0.1 NTU). The instrument was calibrated with manufacturer-supplied formazin standards following the user manual. Before each measurement, the cuvette was rinsed with sample water, filled carefully to avoid bubbles, wiped with a lint-free cloth, and inserted with a consistent orientation. To capture potential drift within a session, turbidity was measured at three time points: before, during, and after the recording session. For analysis and per-clip metadata, the reading closest in time to each 30 s clip (immediately before or immediately after) was used; in each case three replicate readings were taken and the median NTU value was retained.

- Dissolved oxygen. Dissolved oxygen (DO) was measured with a Hanna Instruments HI9147 (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) portable meter equipped with a polarographic probe. According to the farm’s routine practice, DO was taken once daily at approximately 09:00 as a baseline reference for that day’s recordings. The probe was allowed to stabilize per the manufacturer’s instructions, and temperature compensation was applied automatically.

All measurements were conducted following standard handling to minimize contamination and bubble formation. For the per-clip environmental metadata stored in the meta_tilapia_set.csv file, temperature_C and pH correspond to the single measurement taken immediately before the recording of each clip. Turbidity_NTU corresponds to the median of three replicate readings taken at the time point (either pre- or post-session) whose timestamp is closest to the start of the 30 s clip. Dissolved oxygen (DO_mgL) is measured once per day at approximately 09:00, following the farm’s routine practice, and the resulting value is used as a daily baseline assigned to all clips recorded on that date. No temporal interpolation is applied; instead, each clip is linked to the nearest available measurement according to these rules.

2.4. Annotation of Extracted Frames

From the 31 clips, four were randomly selected for frame-by-frame annotation. These clips were drawn from different recording sessions and acquisition settings and include distinct combinations of camera pose (center vs. wall mounted), artificial lighting mode (no light, frontal bar light, and back-mounted light, when applicable), and fish density levels that are typical of the production conditions described in Section 3.2. Their associated water-quality measurements (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity) fall within the ranges observed across the full dataset, ensuring that the annotated subset is representative of the environmental and visibility conditions encountered in the farm.

In each of the four selected 30 s clips, every frame was labeled, yielding 3520 annotated images across the acquired frame-rate range. Detailed polygonal instance masks were created in LabelMe (v5.2.1; wkentaro/labelme, GitHub, San Francisco, CA, USA) JSON format to delineate individual tilapia under varying densities, occlusions, and turbidity; JSON files are directly convertible to COCO and other common formats. Because fine-grained polygon annotation in turbid underwater imagery is labor intensive (requiring several hours of expert work per clip), annotating all 31 clips was not feasible within the scope of this project. Instead, the dataset design prioritizes fully annotated continuous sequences for supervised training and benchmarking, while also releasing all 31 raw clips with synchronized water-quality metadata to support semi-supervised, self-supervised, and future community-driven annotation efforts.

2.5. Data Augmentation

After the annotation process, image-level augmentation was employed to expand the dataset, aiming to enhance sample diversity and improve model generalization. The augmentation strategy involved the synthesis of two common degradations found in underwater imagery: Gaussian blur and mean (box) filtering. For each original annotated frame, two augmented variants were generated.

For each labeled frame, up to two augmented variants were generated by convolving the image with either a Gaussian blur filter or a mean (average) filter. The kernel size was randomly sampled from the set of odd integers i = {3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15}. Gaussian blur reduces high-frequency detail and local contrast, whereas mean filtering produces a local averaging effect; in both cases, edges are smoothed and fine texture is attenuated. These low-pass operations provide a simple, reproducible way to expose learning algorithms to realistic degradations in focus and sharpness that commonly arise in recirculating aquaculture systems due to suspended particles, minor camera defocus, and subtle changes in illumination and water clarity. Similar blurring-based strategies have been used in underwater fish-recognition benchmarks to emulate the impact of variable visibility and reduced image quality on model performance [13,14,15].

To ensure data integrity and traceability, the augmented images were stored in separate, transformation-specific directories. A systematic naming convention was adopted for the output files to indicate the original image, the applied transformation, and a replicate index (e.g., gauss_IMA_0057_1.jpg, prom_IMA_0057_1.jpg). The original polygonal instance annotations, in LabelMe JSON format, were duplicated for each new image.

Crucially, the imagePath field within each new JSON file was updated to match the filename of the corresponding augmented image, thereby maintaining the link between the image and its ground-truth annotation.

2.6. Data Organization and Accessibility

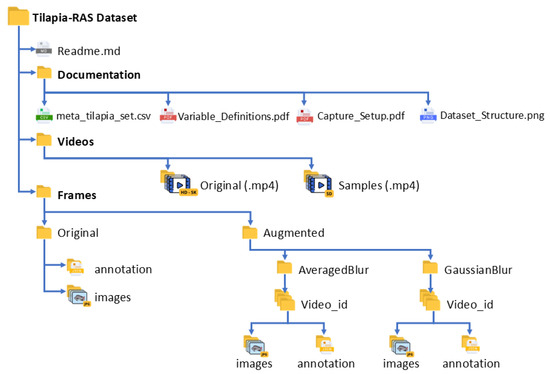

The dataset, Tilapia-RAS Dataset, is organized in a hierarchical folder structure that facilitates reproducibility, annotation management, and selective download.

The root directory contains three top-level folders (videos/, labels/, docs/) and one documentation file (e.g., README.md), as illustrated in Figure 4. The meta_tilapia_set.csv provides per-clip acquisition and water-quality fields (clip_id, date_time_local, camera_pose, depth_cm, lighting_mode, resolution_px, fps, temperature_C, pH, DO_mgL, turbidity_NTU, tank_id).

Figure 4.

Tilapia-RAS repository layout showing top-level folders and documentation files.

The meta_tilapia_set.csv file provides environmental and acquisition parameters for each clip, including turbidity, pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, lighting conditions, and tank identifiers.

Annotated frames are stored in the LabelMe JSON format, one file per image, allowing direct compatibility with conversion tools such as labelme2coco or labelme2yolo. Augmented versions include Gaussian and averaged blur transformations to simulate variations in water turbidity and image sharpness.

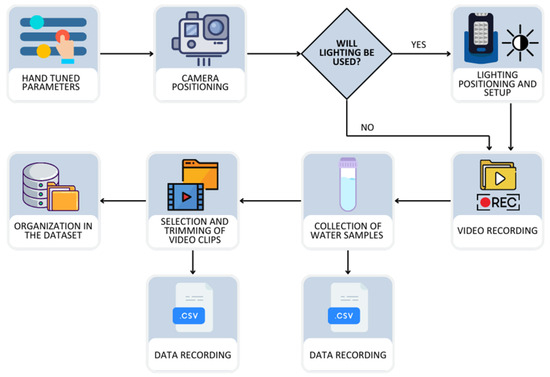

2.7. Workflow Summary

A block diagram summarizes the end-to-end workflow (Figure 5): video recording → environmental measurements → clip curation → annotation → dataset structuring → repository upload. For each recording session, acquisition parameters were randomly assigned from predefined sets: camera position (center vs. wall mount), submersion depth (cm), and artificial lighting mode (off vs. backlight; when applicable, fixed camera–light distance). After capture, physicochemical measurements (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity in NTU) were taken to ensure temporal alignment with the footage.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the data acquisition and dataset creation process.

Short segments with higher fish density and clear behavioral activity were retained as 30 s clips. Frames were then extracted and polygon-based annotations (LabelMe) were created. Files were organized into a reproducible dataset structure while metadata were recorded in parallel into the master CSV (one-to-one with clips). Finally, integrity checks were performed and the dataset was uploaded to the public repository.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Composition

From more than 10 h of raw footage, we curated 31 clips (30 s each; ≈30,752 frames). Video resolutions include 5312 × 4648 (n = 19), 3840 × 3360 (n = 4), 2704 × 2028 (n = 4), and 1920 × 1080 (n = 4), recorded at 24/30/60 fps (exact rates 23.976/30/59.94). Most clips use HEVC/H.265, with a subset encoded in AVC/H.264 for broader compatibility. For each clip, the CSV provides acquisition and environmental fields (camera position, depth, lighting, temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, turbidity).

The dataset comprises ten hours of footage acquired across multiple discontinuous sessions included in Tilapia-RAS correspond to several recording sessions carried out during routine operation of these grow-out tanks, rather than to a continuous long-term monitoring of the full production cycle. As such, the dataset provides a focused, high-resolution snapshot of fish behavior and appearance at a specific, commercially relevant developmental stage under stable husbandry conditions, but does not aim to cover early juvenile stages, harvest operations, or rare events such as acute stress episodes or disease outbreaks.

3.2. Environmental Parameters

Environmental parameters. Across the 31 curated clips, water temperature ranged from 28.1–30.5 °C (median 30.0 °C), pH from 7.43–8.59 (median 8.10), dissolved oxygen from 4.43–5.70 mg/L (median 4.60 mg/L), and turbidity from 4.7–9.2 NTU.

Acquisition settings. Camera depths spanned 10–60 cm. Native frame rates were 23.976, 30.00, and 59.96 fps (reported as 24/30/60 fps in summaries for readability). Video resolutions present in the set were 5312 × 4648 (n = 19), 3840 × 3360 (n = 4), 2704 × 2028 (n = 4), and 1920 × 1080 (n = 4).

Dataset size. With 31 clips × 30 s each and the native frame rates above, the set comprises approximately 30,752 frames (i.e., >30,000).

Notes on labels/augmentation. The accompanying per-clip CSV does not flag annotations or augmented variants for the 31 clips; frame-level labels are provided only for the four fully annotated clips described elsewhere. Exact per-clip counts and metadata are provided in meta_tilapia_set.csv.

These values capture the heterogeneity of commercial aquaponic systems and provide essential context for interpreting fish behavior under varying water quality conditions.

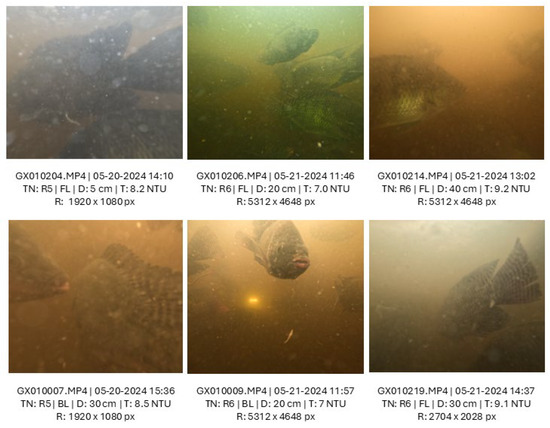

3.3. Representative Samples

To illustrate dataset variability, selected frames demonstrate differences in fish density, turbidity, lighting conditions, and visibility (Figure 6). Annotated examples show the complexity of polygonal segmentation in real aquaculture environments, including occlusions and partial visibility of fish.

Figure 6.

Representative frames from the dataset under varying turbidity, lighting, and fish density conditions.

4. Discussion

Aquaculture is now the primary global source of aquatic animal production (51% in 2022), underscoring the need for scalable monitoring in commercial farms [2].

Beyond this general distinction between laboratory and farm environments, the Tilapia-RAS dataset complements recent video resources obtained in other aquaculture systems. For example, the AV-FFIA dataset for multimodal fish feeding intensity assessment was recorded in a controlled recirculating tank with regulated lighting and filtration to maintain consistent water clarity, thereby minimizing visual noise and background complexity [16]. Similarly, recent underwater image-quality benchmarks, such as TankImage-I, were created in experimental tanks by carefully adjusting water transparency (e.g., clear, medium turbid, and turbid conditions with measured optical transparency) and artificial lighting to generate sequences with gradual, well-controlled degradation of sharpness and color [13]. Datasets focusing on morphometric analysis of grass carp have also been acquired in purpose-built tanks that preserve high water clarity, even when including multiple stocking densities and some turbid conditions [17]. In contrast, our footage was collected in a production-scale recirculating aquaponic system where turbidity ranged from 4.7 to 9.2 NTU and where organic waste, biofloc, feed particles, tank walls, and pipework are routinely visible in the field of view. This combination of commercial stocking densities, moderate turbidity, suspended solids, and variable illumination results in lower image sharpness and more frequent occlusions than in clear-water experimental tanks, making the Tilapia-RAS dataset particularly suitable for benchmarking the robustness of computer-vision models intended for real-world RAS deployments.

Compared with previously published fish datasets [9,10], one of the main advantages of this collection is the inclusion of synchronized physicochemical parameters alongside the video clips. Providing water quality data such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity enhances reproducibility and allows researchers to explore potential correlations between environmental conditions and behavioral patterns. Few available datasets incorporate this dual perspective, making ours a valuable benchmark for integrative approaches.

Another improvement is the inclusion of 3520 annotated frames in LabelMe format, addressing a common limitation noted in prior works where videos were provided without ground-truth labels. These annotations enable immediate use for training and validating object detection and segmentation models, facilitating progress in automated fish monitoring.

Nevertheless, some limitations remain. The dataset covers a relatively short time span (10 h across several days) and does not represent the full growth cycle of tilapia. Clip duration was restricted to 30 s to maximize diversity and facilitate annotation, which may not capture long-term behavioral sequences. Future dataset expansions could include extended monitoring sessions, higher sampling frequency of environmental parameters, and annotations of specific behaviors (e.g., feeding or stress responses).

By combining underwater video, environmental measurements, and annotated images, this dataset provides a foundation for advancing research on aquaculture monitoring, supporting the development of more robust and context-aware computer vision methods for fish welfare assessment.

Furthermore, the visual characteristics of the dataset reflect the specific constraints of intensive aquaculture. The field of view and the number of visible subjects per frame are inherently limited by the turbidity (4.7–9.2 NTU) and suspended solids present in the commercial RAS environment. While these factors challenge the calculation of absolute densities compared to clear-water laboratory datasets, they are essential for developing models robust to real-world occlusions and limited visibility ranges. It is feasible, moreover, to train a model that captures normal behavior of tilapia under specific water conditions, and to use this as a way to detect anomalous behavior that deviates from these patterns, which might be useful in the development of models that can detect stressed behavior.

5. Limitations

This dataset has several limitations that users should consider. First, only four of the thirty-one clips are currently annotated at the frame level with polygonal instance masks, which makes it possible for models trained exclusively on these labels to under-represent rare or extreme situations.

Second, and perhaps more importantly from a behavioral perspective, the dataset does not include episodes of severe stress, disease outbreaks, or harmful husbandry practices. Inducing such adverse states solely for data collection would not be acceptable under current animal-welfare regulations and ethical guidelines. As a consequence, some behaviors that are clinically relevant for early warning of health or welfare problems are not included in recordings.

The remaining unannotated clips are provided together with their physicochemical metadata and are intended to support semi- and weakly supervised learning strategies. A methodological limitation is that the current release includes only a minimal set of baseline augmentations (Gaussian blur and mean filtering) applied to the annotated images, without a comprehensive range of transformations to simulate all possible visibility and imaging conditions. This was a deliberate choice to preserve the original videos and water-quality metadata unchanged and to avoid prescribing a specific augmentation pipeline; however, extending the strategy is straightforward, as the clean annotated frames can be directly used to implement more sophisticated augmentations, including physics-based turbidity models or advanced degradation operators.

Additional limitations concern the environmental and temporal coverage of the data. While temperature, pH, and turbidity were measured for each recording session, dissolved oxygen (DO) was recorded once daily (≈09:00) following farm routines, so DO values should be interpreted as a daily baseline rather than a variable strictly synchronized with each video, especially given potential diurnal fluctuations in intensive RAS. Moreover, the ≈10 h of video were collected from specific grow-out tanks containing fish at a relatively narrow developmental stage under routine feeding and management, providing a coherent and practically relevant snapshot of fish status in an intensive commercial phase but not the full range of behavioral and physiological changes across the entire rearing cycle, nor systematic responses to diverse stressors, disease events, or handling procedures. Ethical and welfare considerations also precluded deliberately inducing severe stress or pathology solely for data collection; future datasets could complement Tilapia-RAS by incorporating additional life stages and opportunistically recorded episodes of naturally occurring stress or disease, under appropriate veterinary supervision and institutional approval.

6. Conclusions

This dataset provides a novel resource for the development of computer vision models applied to aquaculture monitoring. By combining underwater video clips, synchronized physicochemical water parameters, and 3520 annotated frames in LabelMe format, it offers researchers both raw and labeled data for tasks such as detection, segmentation, and behavioral analysis of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus).

The recordings were obtained under realistic production conditions in a recirculating aquaponic system, capturing the challenges of turbidity, variable lighting, and high stocking densities that characterize commercial aquaculture. While limited in temporal scope, this dataset lays the foundation for reproducible and scalable approaches to automated fish monitoring. Future expansions including longer monitoring periods and behavior-specific annotations will further strengthen its applicability. Overall, this work contributes a non-invasive, reproducible, and integrative dataset that supports the advancement of sustainable and welfare-oriented aquaculture technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T. and Y.S.; Methodology, O.A.-B.; Investigation, O.A.-B.; Resources, L.T. and G.J.V.E.B.; Validation, G.J.V.E.B.; Data curation, J.L.A.-V.; Writing—original draft preparation, O.A.-B.; Writing—review and editing, L.T. and Y.S.; Supervision, L.T. and Y.S.; Funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by TecNM (Mexico) project 21802.25-P, CONAHCYT (SECIHTI, Mexico) project CF-2023-I-724.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset described in this Data Descriptor is openly available on Zenodo under the CC BY 4.0 license: Tilapia-RAS Dataset: Underwater Videos and Polygon-Annotated Frames with Physicochemical Metadata. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17518786.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. G.J.V.E.B. is affiliated with the farm where data were collected; this affiliation did not influence study design, data curation, or analysis.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| RAS | Recirculating Aquaculture System |

| NTU | Nephelometric Turbidity Units |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| ATC | Automatic Temperature Compensation |

References

- Dunshea, F.R.; Sutcliffe, M.; Suleria, H.A.R.; Giri, S.S. Global issues in aquaculture. Anim. Front. 2024, 14, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024—Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, B.; Ewell, C.; Jacquet, J. Animal welfare risks of global aquaculture. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg0677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Miao, Z.; Du, L.; Duan, Y. Automatic recognition methods of fish feeding behavior in aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colt, J.; Schuur, A.M.; Weaver, D.; Semmens, K. Engineering design of aquaponics systems. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 30, 33–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadeiro, V.; Rodriguez, A.; Henry, J.; Wlodkowic, D.; Andersson, D. A review of 28 free animal-tracking software applications: Current features and limitations. Lab. Anim. 2021, 50, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Li, W.; Yin, X.; Li, Z.; Ying, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Miao, F.; et al. Abnormal behavior monitoring method of Larimichthys crocea in recirculating aquaculture system based on computer vision. Sensors 2023, 23, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, M.; Yang, N.; Tao, C.; Zhi, H.; Luo, H. Underwater object detection and datasets: A survey. Intell. Mar. Technol. Syst. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Wang, W. Fish tracking, counting, and behaviour analysis in digital aquaculture: A comprehensive survey. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, 13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abangan, A.S.; Kopp, D.; Faillettaz, R. Artificial intelligence for fish behavior recognition may unlock fishing gear selectivity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1010761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacheler, N.M.; Shertzer, K.W.; Schobernd, Z.H.; Coggins, L.G., Jr. Calibration of fish counts in video surveys: A case study from the Southeast Reef Fish Survey. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1183955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letessier, T.B.; Juhel, J.B.; Vigliola, L.; Meeuwig, J.J. Low-cost small action cameras in stereo generate accurate underwater measurements of fish. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2015, 466, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yin, G.; Wang, H.; Dong, J.; Xie, Z.; Zheng, B. A Underwater Sequence Image Dataset for Sharpness and Color Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Tuñón, O.; Jardón, A.; Balaguer, C. Generation and Processing of Simulated Underwater Images for Infrastructure Visual Inspection with UUVs. Sensors 2019, 19, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, A.; Jalal, A.; Shafait, F.; Mian, A.; Shortis, M.; Seager, J.; Harvey, E. Fish species classification in unconstrained underwater environments based on deep learning. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2016, 14, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Du, Z.; Chen, T.; Lian, G.; Li, D.; Wang, W. Multimodal fish feeding intensity assessment in aquaculture. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 9485–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Guo, C.; Shi, M.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. A method for custom measurement of fish dimensions using the improved YOLOv5-keypoint framework with multi-attention mechanisms. Water Biol. Secur. 2024, 3, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).