Abstract

This literature review examined the relationship between energy drink consumption and cardiovascular health in young people. Following PRISMA 2020, we searched Scopus for articles published from 2020 to 2025 and included 33 original studies after screening 133 records. Evidence from observational, clinical, and experimental research was synthesized into six themes: youth consumption; direct cardiovascular outcomes; composition and toxicity; animal or cellular experiments; perceptions and habits; and occupational or sociodemographic factors. Across studies, habitual intake was linked to acute blood-pressure rises, arrhythmias, endothelial dysfunction, and metabolic disturbances, sometimes within 24 h of a single can. Risks were amplified by high caffeine and taurine doses and by co-use with alcohol or intense exercise. Adolescents and young adults were most vulnerable, due to heightened sympathetic responses, frequent use under academic or work stress, and limited risk perception. Authors highlighted five actions: longitudinal research; tighter ingredient monitoring and transparent labeling; consumer education; protection of vulnerable groups; and clinical guidance for responsible use. These results were observed across regions and study designs. Overall, the findings indicate that unregulated energy-drink consumption is a preventable cardiovascular risk in youth, justifying the use of coordinated public-health measures, including curriculum-based education, marketing restrictions, ingredient oversight, and clinical screening to mitigate harm.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the consumption of energy drinks has grown exponentially worldwide, particularly among adolescents and young adults [1]. This trend raises concerns within the healthcare community, as many consumers are unaware of the physiological effects these beverages exert on the body, particularly on the cardiovascular system [2]. A large proportion of the population does not associate caffeine intake with its health effects [2,3], fostering unregulated consumption patterns due to the gap in perceived cardiovascular risk [4].

In this context, it is relevant to provide concrete evidence that illustrates the global scope of the phenomenon. Therefore, Table 1 presents quantitative and qualitative data on energy drink consumption by region and age group in various representative countries (United States, Spain, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa), along with their key observations. These data show that, regardless of geographic context, a high percentage of young people regularly consume these beverages, often with limited risk perception and under insufficient regulatory frameworks. This information complements the previous arguments, reinforcing the concerns raised and contextualizing the global relevance of the issue before delving into its associated effects and mechanisms.

Table 1.

Quantitative and qualitative data on energy drink consumption.

At the international level, various studies have documented the potential effects of energy drinks on cardiovascular health [11,12,13], mainly due to their components such as caffeine and taurine, among others. In many European countries, coffee and tea are major dietary sources of caffeine, with average intakes that in some populations approach the upper limits of 300–400 mg per day recommended for adults and older adolescents [14,15]. Similarly, in several Latin American countries, high per capita consumption of coffee and yerba mate contributes substantial amounts of caffeine to the daily diet [14,16]. In these settings, the addition of even a single energy drink serving may cause total daily caffeine intake to exceed levels considered safe for young consumers [15,17]. From a pathophysiological perspective, caffeine increases the release of catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), which intensifies sympathetic activity [13,18], leading to elevated heart rate and blood pressure [19]. Such hyperstimulation can induce endothelial dysfunction, increased arterial stiffness [13], oxidative stress, and sympathetic overactivity [2]. Cardiovascular risk models, such as those developed by [19], emphasize that these effects are exacerbated in the adolescent population. Even in healthy adolescents, the consumption of energy drinks (EDs) causes a significant increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure 24 h after ingestion [20]. More recently, a cross-sectional study in German adolescents with chronic high energy drink consumption did not detect significant differences in routine cardiological parameters compared with non-consumers, although about half of the high consumers reported palpitations or chest pain after energy drink intake and they showed higher prevalence of alcohol use, smoking and short sleep duration [21].

Likewise, high consumption of caffeine and other stimulants present in these beverages entails additional risks for cardiovascular health. Excessive intake of methylxanthines (such as caffeine and theobromine) may induce tachyarrhythmias and atrial or ventricular fibrillation [22]; this alters cardiac conduction by reducing atrial refractoriness, leading to severe cardiovascular complications [23], including myocardial infarction due to coronary vasospasm [13].

This issue is particularly relevant in Latin America, where the popularity of energy drinks has increased considerably in recent years. In countries such as Peru, this rise has occurred in an environment of weak regulation, limited nutritional education, and minimal oversight of sales to minors. Although moderate caffeine consumption may provide transient benefits, such as improved alertness and physical performance, these potential advantages are largely theoretical. In real-world settings with weak regulation and limited health education, they are overshadowed by excessive and poorly supervised intake among young people [24]. This exposes a large proportion of the young population to potentially severe cardiovascular consequences. However, scientific studies addressing this issue from a regional perspective remain scarce, revealing a gap in the literature on the impact of energy drink consumption [13].

In response to these gaps, this review integrates the current evidence into six thematic categories that collectively describe the cardiovascular risks of energy drinks, patterns of consumption, physiological mechanisms, and population vulnerabilities. In addition, it systematizes five groups of proposals and contributions reported in the included studies, encompassing preventive, regulatory, educational, monitoring, and clinical actions. This combined analytical approach offers a comprehensive perspective that has not been reported in previous reviews, particularly regarding implications for Latin America, where empirical studies remain limited despite the rapid expansion of energy drink consumption.

Given these findings, it is essential to develop comprehensive educational programs in schools to warn about the cardiovascular risks of excessive caffeine consumption [25,26], as well as to promote health literacy, particularly regarding caffeine [2], limit access for minors [1], and implement market surveillance, intersectoral collaboration, and coherent regulatory frameworks that prioritize public health over commercial interests [27].

In this scenario, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) should be considered, particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. This includes target 3.4, which seeks to reduce premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases (including cardiovascular diseases) by one third through prevention and treatment. Likewise, SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) seeks to ensure sustainable consumption patterns and includes target 12.8, which highlights the importance of ensuring that people have relevant information to adopt healthy lifestyles. Evidence from other adolescent health domains shows that coherent policy frameworks aligned with SDG 3 can effectively reduce preventable risks, such as adolescent pregnancy and related maternal morbidity in Latin American settings [28]. The absence of specific regulations and public awareness campaigns on energy drink consumption undermines both objectives, exposing adolescents to preventable risks without adequate guidance. In this context, scientific research plays a fundamental role in providing evidence, raising public awareness, and supporting the design of public policies aimed at mitigating the negative impact of these practices on cardiovascular health.

Therefore, this article aimed to analyze the relationship between energy drink consumption and the onset of cardiovascular diseases in adolescents. Through a review of the recent scientific literature, it seeks to provide evidence to understand the effects that regular consumption of these products exerts on cardiovascular health. Previous investigations, most of them conducted before 2020 and summarized in the preceding paragraphs and in Table 1, have mainly described the physiological mechanisms, acute hemodynamic responses and isolated clinical reports of cardiovascular complications associated with energy drink intake, but an integrated synthesis of recent empirical findings in adolescents and young adults is still lacking.

Consequently, the following research question was posed: What are the most frequent mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and regulatory gaps associated with energy drink consumption in relation to cardiovascular diseases in young people, according to the scientific evidence between 2020 and 2025? We specifically focused on the critical gap, namely the lack of age-stratified analysis.

2. Methodology

The research was designed as a review of the scientific literature, conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. This approach allowed for a clear and structured synthesis of the current evidence on the adverse effects of energy drink consumption on health, with special emphasis on its impact on the cardiovascular system. To ensure rigor, transparency, and reproducibility of the process, explicit methodological criteria were defined for each stage of the study.

First, the literature search was conducted in the Scopus database, selected for its broad multidisciplinary coverage, the rigor of its peer-review processes, and the high scientific quality of its indexed publications. These features ensured the inclusion of relevant and reliable studies within the field of health sciences. The search strategy combined the English terms “energy drinks” and “diseases,” applied through Scopus’s TITLE-ABS-KEY function to the title, abstract, and keywords fields. Additionally, the search was limited exclusively to open-access original articles published between 2020 and 2025. The 2020 to 2025 time window was chosen to concentrate the analysis on the most recent evidence on the cardiovascular effects of energy drinks and to provide an updated synthesis, while earlier research is summarized narratively in the Introduction. This restriction was adopted to ensure that all studies included in the review were available in full text for readers, researchers and decision makers, which facilitates verification of the findings and replication of the search process in settings with limited institutional access to subscription-based journals. Prioritizing open-access evidence is also consistent with current open science practices that promote transparency and equitable access to health research.

Moreover, before performing the search, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to adequately select the studies. Only original articles reporting research conducted on humans or animals and evaluating adverse effects associated with energy drink consumption were included, without imposing any geographical restrictions. Conversely, literature reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, and all studies not available in open access were excluded. The final search string applied in Scopus was: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“energy drinks”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (diseases)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) AND LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”).

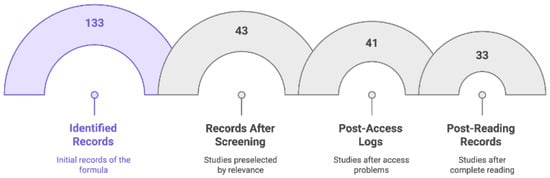

Application of this initial search formula identified a total of 133 bibliographic records. Subsequently, the screening process was carried out through a preliminary review of the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles, after which 90 studies that did not directly address the relationship between energy drink consumption and its health effects were excluded. Of the remaining 43 preselected articles, 2 could not be retrieved due to access issues, while another 8 were discarded after full-text reading due to lack of thematic or methodological relevance. Consequently, a final sample of 33 relevant studies was obtained, all of which fully met the defined criteria and were subjected to an in-depth analysis for the present work (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bibliographic records on energy drinks: Identified records (133), records after screening (43), post-access logs (41), and post-reading records (33).

To facilitate the extraction and organization of data from these studies, a standardized matrix was designed in Microsoft Excel. This tool systematically recorded the key data from each included study (author, year of publication, country of origin, and main thematic category), enabling comparison, identification of common patterns, and overall analysis of the reported findings Supplementary File S1—Thematic Categories).

Complementarily, and with the aim of assessing the quality and academic impact of the reviewed sources, the articles were classified according to the CiteScore quartile corresponding to their year of publication. This metric, widely used for the evaluation of scientific journals, places publications within percentile ranges that reflect their visibility and influence in the academic community. As shown in Table 2, most of the analyzed studies were published in high-impact journals, with a predominance of Q1 quartile (37.5%), followed by Q4 (25%), and, to a lesser extent, Q2 and Q3 (18.75% each). This distribution indicates that more than half of the articles (62.5%) were published in Q1 and Q2 journals, supporting the robustness and relevance of the reviewed literature. Moreover, the presence of publications in all years of the 2020–2025 period reflects a sustained interest of the scientific community in the topic addressed.

Table 2.

Distribution of reviewed sources according to CiteScore quartile and year.

Together, these indicators summarize the quality and temporal distribution of the scientific production included in this review.

3. Results

This review analyzed 33 scientific articles published between 2020 and 2025 that address the association between energy drink consumption and various alterations related to cardiovascular health. These studies presented a broad methodological spectrum, including observational and experimental research, clinical reviews, case reports, and analyses on perception and behavior.

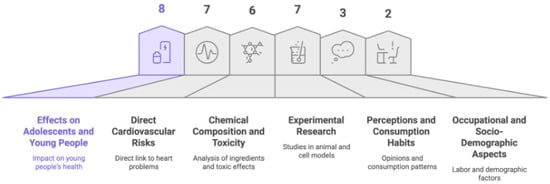

To organize and present the findings in a clear and coherent manner, two main analytical dimensions were established. The first dimension consisted of identifying thematic categories based on the specific topics addressed by the reviewed studies (see Figure 2; Supplementary File S1—Thematic Categories). From this perspective, six categories were identified: consumption and effects in adolescents and young adults (8 studies), direct cardiovascular risks (7 studies), chemical composition and toxicity of components (6 studies), experimental research in animal or cell models (7 studies), perceptions and consumption habits (3 studies), and occupational and sociodemographic aspects (2 studies). Therefore, Figure 2 shows the distribution of studies in each identified thematic category, thus facilitating a visual understanding of the topics addressed in the reviewed literature.

Figure 2.

Category of topics addressed by the articles.

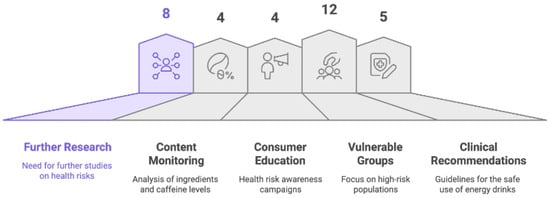

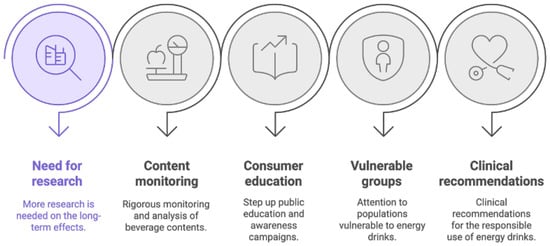

The second dimension involved identifying categories related to the proposals and contributions made by the authors (see Figure 3; Supplementary File S2—Categories of Proposals and Contributions). In this dimension, five main categories were observed: need for further research (8 studies), monitoring of beverage content (4 studies), consumer education and awareness (4 studies), attention to vulnerable groups (12 studies), and clinical recommendations for responsible use (5 studies). Figure 3 presents the graphical distribution of these categories, clearly illustrating the main contributions and recommendations suggested in the reviewed scientific literature.

Figure 3.

Contributions identified in the literature on energy drinks and cardiovascular risk.

3.1. Thematic Categories

3.1.1. Consumption and Effects in Adolescents and Young Adults

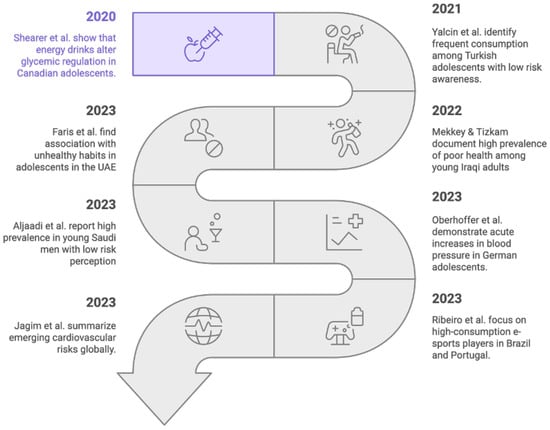

The young population, considered particularly vulnerable, was the focus of eight studies that examined the magnitude of energy drink consumption and its effects. The general aim of these works was to assess consumption patterns, associated factors, and the potential implications for the physical and mental health of young consumers, providing direct information to understand the cardiovascular risks linked to this habit (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Emerging cardiovascular risks of energy drink consumption [20,24,29,30,31,32,33,34].

First, a study conducted in the United Arab Emirates investigated the association between energy drink consumption and health behaviors among adolescents [29]. They found that such consumption was significantly associated with multiple unhealthy habits, found that such consumption was significantly associated with multiple unhealthy habits as well as with alterations in physical and mental well-being. These effects may act as an indirect factor predisposing to cardiovascular diseases through the accumulation of risk factors. Second, in the Iraqi context, a high prevalence of consumption among young adults and its relationship with poorer health status has been documented, highlighting the cardiovascular risk linked to continuous exposure to high doses of caffeine and taurine [30]. Third, a study conducted in Turkey identified a very frequent consumption pattern among adolescents, associated with limited knowledge of adverse cardiovascular effects [31]. Fourth, in Saudi Arabia, sociodemographic factors related to consumption were examined and a high prevalence of energy drink use among young males was reported, along with a low perception of the associated cardiovascular risk [32].

Fifth, a randomized clinical trial conducted in Germany evaluated the acute effects of energy drink consumption on the hemodynamic profile of adolescents, demonstrating significant increases in blood pressure following acute intake and evidencing immediate cardiovascular effects [20]. Sixth, evidence from Canada showed that the consumption of caffeine-containing “energy shots” among adolescents alters acute glycemic regulation; this effect could represent an additional metabolic risk factor for the later development of cardiovascular diseases [33]. Seventh, a study carried out in Brazil and Portugal focusing on e-sports players identified high rates of energy drink consumption in a context of “competitive sedentarism,” a pattern that may amplify metabolic and cardiovascular risks in this population [24]. Finally, with an international approach, a broad review summarized emerging cardiovascular risks associated with energy drink consumption, highlighting the occurrence of arrhythmias, hypertension, and acute adverse events when intake is excessive or combined with alcohol and exercise [34].

3.1.2. Cardiovascular Risks

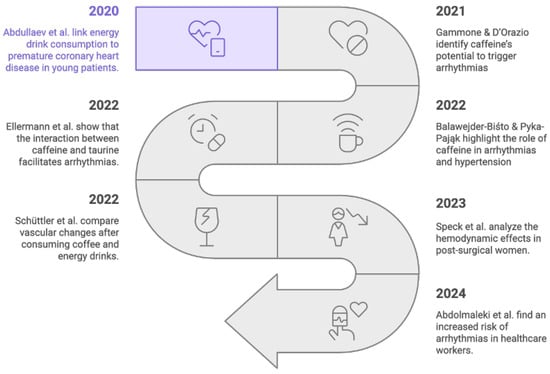

Recent scientific evidence has extensively documented the cardiovascular effects associated with energy drink consumption. This literature review included seven studies that specifically examined these risks, assessing outcomes ranging from acute hemodynamic alterations to arrhythmogenic potential and even the premature development of coronary artery disease linked to these beverages. The key findings of each study are presented below.

First, in Germany, the hemodynamic effects of energy drink consumption in women undergoing microsurgical breast reconstruction were analyzed, observing changes in perfusion variables [35]. Second, also in Germany, acute changes in vascular tone following the intake of coffee versus energy drinks were compared, revealing immediate vascular alterations with both types of beverages [36].

Third, in Poland, the impact of caffeine on the cardiovascular system was investigated, noting that high concentrations of caffeine, as found in energy drinks, promote the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias and hypertension [27]. Fourth, in Germany, this effect was experimentally confirmed in ex vivo cardiac models, where the interaction between caffeine and taurine (an amino acid typical of energy drinks) facilitated the onset of ventricular arrhythmias [37]. Similarly, fifth, in Italy, the effect of methylxanthines such as caffeine on heart rhythm was analyzed, identifying their potential to trigger various forms of arrhythmia [22].

Sixth, in Iran, the frequency of premature atrial and ventricular contractions (PACs and PVCs) associated with caffeine consumption among healthcare personnel was evaluated, finding a higher risk of these arrhythmias in individuals with high intake [25]. Lastly, seventh, in Russia, high energy drink consumption was linked to the premature development of coronary artery disease in patients under 40 years of age, suggesting that the abusive use of these products could contribute to the early onset of cardiovascular pathology [38] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cardiovascular risks of energy drinks—Timeline of studies [22,25,27,35,36,37,38].

Taken together, the findings of these seven studies converge in indicating that energy drink consumption exerts adverse effects on the cardiovascular system at different levels. These effects range from acute elevations in hemodynamic parameters to an increased propensity for arrhythmias and the possible acceleration of coronary artery disease in young populations. This convergence of results, obtained in diverse clinical and experimental contexts, reinforces the relevance of the issue as a public health concern and suggests the need to deepen research while promoting greater caution regarding the consumption of such beverages.

3.1.3. Chemical Composition and Component Toxicity

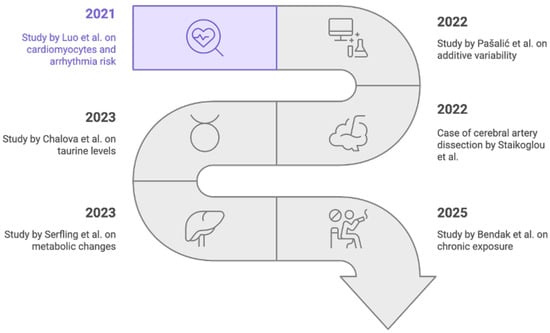

The chemical composition of energy drinks has been examined as a potential underlying factor in their cardiovascular effects. In this context, six recent studies analyzed the active components of these beverages and their potential toxicity to health. In this section, studies were grouped according to their direct evaluation of individual energy drink components and their potential toxicological effects, regardless of whether the evidence came from analytical, clinical, or cellular experimental designs.

First, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a quantification of various additives in energy drinks using high-performance liquid chromatography was conducted, finding significant variability in the levels of their active components [39]. Second, mass spectrometry was employed to measure taurine in these products, highlighting that this amino acid is present at very high concentrations and that its interaction with caffeine could have cardiovascular implications [40]. Third, in a joint China–USA study, human cardiomyocytes derived from stem cells were exposed to energy drink ingredients; electrical dysfunctions in the frequency and latency of cardiac contractions were observed, suggesting a potential arrhythmogenic risk associated with these components [41].

Fourth, in Greece, a clinical case of “posterior cerebral artery dissection” in an adolescent following excessive caffeine consumption was reported, thus illustrating the potential neurological adverse effect of extremely high doses of this stimulant [42]. Fifth, in Germany, PET/CT imaging was used to study metabolic changes after energy drink ingestion, detecting hepatic and systemic alterations that could indirectly imply an increased cardiovascular risk [43]. Finally, in the United Arab Emirates, repetitive consumption of these beverages among healthcare professionals was explored, finding that chronic exposure to their stimulants could contribute to a “cumulative cardiovascular burden” in these individuals [44] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Energy drink components and cardiovascular health [39,40,41,42,43,44].

In summary, these findings highlight that variability in the chemical composition of energy drinks, including high concentrations of stimulants such as caffeine and taurine, can result in significant toxic effects. Such effects range from cellular alterations in cardiac electrical function and systemic metabolic changes to severe acute vascular events in extreme cases. Taken together, the evidence suggests a potential negative impact on cardiovascular health associated with these beverages, especially when consumption is excessive or chronic. Although the designs of the included studies (analytical determinations, functional imaging and clinical observation) are heterogeneous, they consistently portray energy drinks as products with non-neutral pharmacological profiles rather than simple soft drinks.

3.1.4. Experimental Research in Animal or Cellular Models

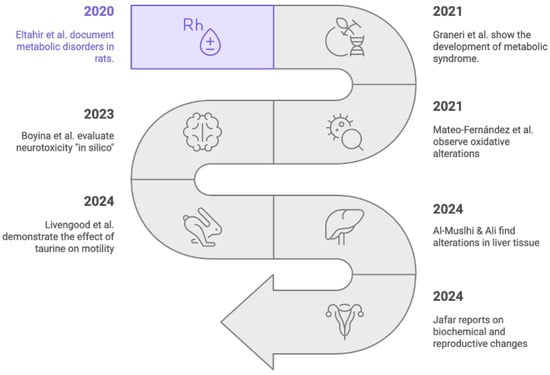

In the experimental field, various preclinical models, ranging from simple animal organisms to cell cultures and in silico simulations, have been employed to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms associated with energy drink consumption. In total, seven recent studies implemented these approaches to elucidate the effects of such beverages on the body and their potential cardiovascular impact.

First, planarians were used as a model organism and it was demonstrated that taurine increases motility through activation of the dopaminergic pathway; this effect suggests sympathetic stimulation that could affect the cardiovascular system [45]. Second, in Spain, the effects of isolated beverage components (such as taurine and glucose) as well as complete energy drinks were evaluated both in vivo and in vitro, observing oxidative alterations in cells that were potentially harmful to metabolism and the cardiovascular system [46]. Third, in Iraq, the impact of chronic energy drink consumption on the liver of male rats was investigated, and histological alterations in the hepatic tissue of these animals were found [47]. Fourth, significant changes in biochemical and reproductive parameters were reported in rats subjected to prolonged ingestion of these beverages, evidencing systemic effects beyond the immediate cardiovascular system [48].

Fifth, in India, in silico studies were conducted to assess the neurotoxicity of various typical energy drink components (such as glucuronolactone, taurine, and gluconolactone), identifying potential neuronal alterations in rat offspring exposed to these substances [49]. Sixth, in Australia, chronic consumption of both sugar-sweetened and sugar-free energy drinks was demonstrated to equally promote the development of metabolic syndrome in animal models, showing that both excessive sugar and the combination of caffeine and other additives exert similar adverse effects [50]. Finally, in Saudi Arabia, prolonged energy drink intake was documented to induce metabolic disorders in rats, including dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and alterations in hepatic profiles, thus establishing an indirect link between chronic consumption of these beverages and increased cardiovascular risk [51] (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Timeline of research in animal or cellular models [45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

In summary, the experimental findings described highlight the multiple adverse biological effects associated with energy drink consumption. Observed effects range from alterations in neurotransmission and cellular oxidative balance to specific tissue damage in the liver and systemic metabolic imbalances in laboratory animals. Taken together, this preclinical evidence reinforces the biological plausibility that habitual consumption of energy drinks may trigger pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to the risk of cardiovascular disease. Despite the diversity of animal species, exposure protocols and outcome measures used, the direction of the effects is consistently unfavorable, suggesting a net harmful impact of repeated energy drink exposure on physiological homeostasis.

3.1.5. Perception and Consumption Habits

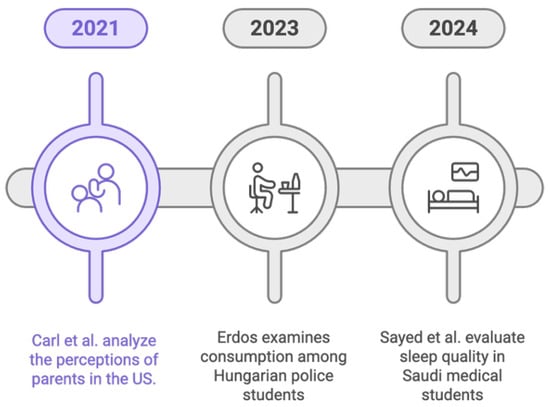

The assessment of consumption patterns and risk perception associated with energy drinks constitutes a relevant line of inquiry in the recent literature, as behavioral and cognitive factors can significantly modulate their health impact. In this regard, three studies included in this review addressed these issues in different populations and contexts.

First, coffee and energy drink consumption among university students at police academies in Hungary was examined, identifying a high prevalence of use and possible indications of caffeine use disorders, particularly under conditions of high academic and occupational demands [52]. Second, sleep quality among medical students in Saudi Arabia experiencing academic stress was evaluated, and regular energy drink consumption was found to be associated with a higher frequency of disturbances in rest patterns, exacerbated by academic workload overload [53]. Finally, parental perceptions in the United States regarding the health risks of sugar-sweetened and energy drinks were analyzed; while some level of awareness among parents was detected, significant gaps were identified in understanding the adverse effects of these beverages, particularly concerning children’s metabolic and cardiovascular health [54] (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Perspectives on energy drink consumption [52,53,54].

In summary, these studies show that energy drink consumption habits tend to intensify in contexts of high academic or occupational demand, while risk perception remains limited in key population segments. These findings underscore the need to strengthen educational and awareness strategies on the potential harmful effects of energy drinks, addressing both the reduction in their consumption in stressful situations and the improvement of public knowledge, particularly among young people and their parents, regarding the implications for cardiovascular health.

In combination, these three studies portray energy drink use as a behavioral response to sustained academic and occupational demands, where beverages are consumed to counteract fatigue while simultaneously worsening sleep quality and recovery. The evidence also shows that awareness of cardiovascular harm remains limited even in groups that might be expected to be better informed, such as health sciences students and parents who make purchasing decisions for their children. This misalignment between perceived benefits and documented risks helps to explain the persistence of high consumption despite emerging warnings and highlights the importance of interventions that simultaneously address consumption habits, sleep hygiene, and risk communication.

3.1.6. Occupational and Sociodemographic Aspects

The influence of sociodemographic and even occupational factors on energy drink consumption and its potential link to cardiovascular diseases has also been the subject of research. In this review, two studies were identified that address these aspects from different population perspectives.

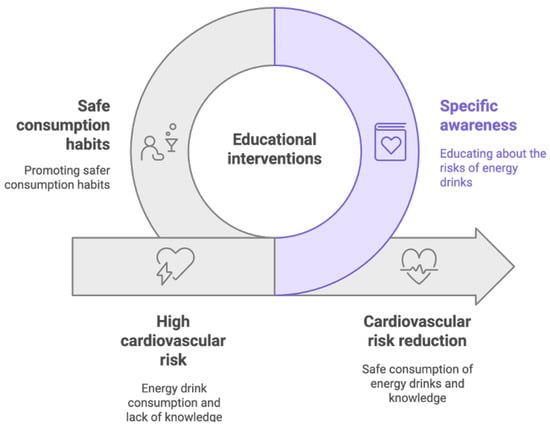

First, in Indonesia, an analytical model was developed to examine factors associated with hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Within the behavioral patterns assessed, regular consumption of stimulant beverages emerged as a habit significantly linked to cardiovascular risk, according to data collected from national health surveys [55]. Second, the level of knowledge among primary care patients in urban areas of Poland regarding risk factors for hypertension was analyzed, finding limited awareness of the potentially harmful effects that energy drink consumption can have on blood pressure and cardiovascular health in general [3] (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Cardiovascular risk reduction strategy through education [3,55].

In summary, the available evidence suggests that sociodemographic characteristics, such as place of residence or certain population lifestyle habits, and even the occupational context may influence patterns of energy drink consumption and, consequently, the associated cardiovascular risk. Furthermore, insufficient knowledge regarding the dangers linked to energy drink consumption is evident in certain population groups. These findings highlight the need to implement educational and awareness interventions tailored to specific contexts, with the aim of improving understanding of the cardiovascular risks associated with energy drinks and promoting safer consumption habits within the community.

3.2. Categories Related to the Authors’ Proposals and Contributions

This section presents an integrated analysis of the main contributions identified in the reviewed literature. These contributions highlight critical areas where the authors propose concrete measures aimed at mitigating the risks associated with energy drink consumption, emphasizing both preventive and clinical aspects. The reviewed proposals offer valuable perspectives and specific actions intended to strengthen research, optimize regulation, improve consumer knowledge, and protect in particular those population groups most susceptible to the adverse effects of these beverages (see Figure 10). This figure provides a visual summary of these five approaches, organizing them into preventive, regulatory, educational, and clinical lines of action. The diagram shows how each category contributes to mitigating cardiovascular risks, either by guiding public health strategies, informing regulatory decisions, or supporting clinical recommendations. This visual integration highlights the complementary nature of the contributions reported in the reviewed studies.

Figure 10.

Contributions to mitigate the risks of energy drinks.

3.2.1. Need for Further Research

Eight reviewed studies emphasize the pressing need to deepen research on the long-term effects of energy drinks on cardiovascular health (Table 3). These authors agree that significant knowledge gaps remain that must be addressed through new studies. In particular, they call for a clearer understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, the dose–response relationship of stimulant components, their interactions with other cardiovascular risk factors, and the cumulative effects in different exposed populations. Some works suggest specific lines of research, such as examining the neurobiological effects of key ingredients (for example, taurine) in animal models, validating in human subjects the experimental findings that point to potential risks (such as arrhythmias or metabolic alterations), and evaluating possible protective measures, for example, the use of antioxidant compounds like pomegranate juice that could mitigate toxicity. Overall, these contributions highlight that the current scientific evidence is insufficient and that additional studies are needed to fully clarify the cardiovascular implications of habitual energy drink consumption.

Table 3.

Need for further research.

3.2.2. Monitoring the Content of Energy Drinks

Four studies reveal the need for rigorous monitoring and improved analysis of the content of energy drinks (Table 4). It is highlighted that there is considerable variability in the composition of active ingredients such as caffeine, taurine, sugars, and other additives among different brands and product presentations, which makes it difficult to establish safe consumption limits and complicates the objective comparison of risks between products available on the market. In response to this situation, the authors propose strengthening control and transparency mechanisms, which include developing more precise analytical methods (such as the exact quantification of taurine and other additives) and improving nutritional labeling to accurately reflect the content of each drink. Advanced techniques, such as metabolic imaging, have even been explored to track the distribution and impact of these components in the body, demonstrating innovative approaches to assessing their safety. The consensus among these studies is that stricter monitoring of the composition of energy drinks would allow for better-informed consumption recommendations and greater consumer protection through uniform standards and clear regulations

Table 4.

Monitoring the content of energy drinks.

3.2.3. Education and Consumer Awareness

Four studies advocate for intensifying public education and awareness campaigns about the risks associated with energy drink consumption (Table 5). These studies highlight that significant information gaps persist in the general population, particularly among adolescents, young adults, and even their parents, regarding the possible cardiovascular consequences of excessive consumption. Several authors emphasize the urgency of implementing educational programs that highlight the high addictive potential of caffeine and correct the mistaken perception of harmlessness surrounding these products. Evidence also shows the effectiveness of direct communication measures, such as a study demonstrating that including explicit graphic warnings on labels significantly improves the perception of potential harm from energy drinks. In addition, deficiencies have been identified in the knowledge of specific health issues, such as the relationship between regular consumption of these drinks and arterial hypertension, especially in urban settings. In summary, the proposals in this category stress that empowering consumers through truthful and accessible information is crucial for promoting safer consumption habits and reducing the incidence of adverse effects.

Table 5.

Consumer education and awareness.

3.2.4. Attention to Vulnerable Groups

Twelve studies focused their contributions on populations particularly vulnerable to the impact of energy drinks, such as adolescents, women, workers with extended schedules (for example, healthcare personnel), and individuals with preexisting medical conditions (Table 6). Evidence suggests that these groups tend to consume energy drinks more frequently and to underestimate their risks, which increases their susceptibility to negative outcomes. In adolescents and university students, worrying consumption patterns have been reported, associated with sleep disturbances, decreased academic performance, and other harmful effects, leading authors to propose targeted preventive interventions in educational settings. Likewise, certain occupational groups subject to stress and fatigue, such as healthcare personnel working long shifts, are identified as at-risk populations that require support measures and occupational regulations to limit caffeine dependence and protect cardiovascular health. Even in individuals with preexisting clinical conditions, such as patients with metabolic diseases or cardiovascular risk factors, regular consumption of these drinks has been warned to potentially exacerbate their health problems, with some cases documenting toxic effects on male fertility in contexts of chronic consumption. Overall, the studies agree on the importance of designing prevention and education strategies tailored to each vulnerable subgroup, so that public health interventions can prioritize those facing a higher risk from the harmful effects of energy drinks.

Table 6.

Care for vulnerable groups.

3.2.5. Clinical Recommendations for Responsible Use

Finally, five studies provided specific clinical recommendations to promote safer and more responsible consumption of energy drinks (Table 7). Among their proposals, they emphasized the need to restrict or strongly discourage consumption among minors, as well as to avoid combining these drinks with alcohol or intense physical exercise, given the potential increase in cardiovascular risks under such circumstances. Health professionals are also urged to warn individuals with a predisposition to or history of cardiovascular disorders about the specific risks that energy drink consumption may pose in their situation. Several authors also advocate for the implementation of stricter regulations on the marketing and labeling of these products, ensuring that the public receives clear information on their stimulant content and possible adverse effects.

Table 7.

Clinical recommendations for responsible use.

4. Discussion

The present analysis confirms a close relationship between energy drink (ED) consumption and various cardiovascular alterations in young people, evidenced at multiple levels, from pathophysiological mechanisms and biochemical effects to clinical manifestations, social behaviors, and regulatory gaps [26,57]. In other words, visible symptoms, such as hypertension or arrhythmias, are only the tip of the iceberg, supported by less apparent underlying causes that require priority attention in public health. This integrative view underscores an apparent harmlessness of EDs, since behind their superficial effects, such as increased alertness or a sense of improved performance, there are significant compromises in cardiovascular homeostasis [13].

Numerous studies consistently support the acute hemodynamic effects of EDs. It has been documented that a single intake can produce sustained increases in blood pressure and cardiac output, even in healthy adolescents. In this study, a significant increase in systolic and diastolic pressure was observed after weight-adjusted consumption, indicating a particular vulnerability of the young population to these stimulants [20]. Consistently, it has been shown that consuming a single can of an ED markedly elevates blood pressure and cardiac output under conditions of mental stress, suggesting that even brief exposures may pose a relevant cardiovascular overload in everyday situations [35]. It should be noted that the vasopressor impact of EDs may be more aggressive than that of coffee, since EDs have been shown to increase both peripheral and central blood pressure. Although very moderate caffeine consumption could exert some long-term vasodilatory effect, these possible benefits are eclipsed in young populations by the catecholamine surges triggered by EDs. Taken together, the evidence leaves little doubt about the potent immediate pressor and chronotropic effect of these beverages, which seriously calls into question their perceived harmlessness [20,35].

At the same time, the reviewed literature shows that the clinical expression of cardiovascular risk depends strongly on dose and context. An integrative review highlighted that arrhythmias, hypertension and acute adverse events are mainly observed when energy drink intake is excessive or combined with alcohol consumption and strenuous exercise [34]. Similarly, a case report from Greece described a posterior cerebral artery dissection in an adolescent after extremely high caffeine intake, illustrating that neurological complications have been reported under conditions of abusive consumption [42]. In contrast, clinical studies in surgical patients and healthy volunteers have mostly documented acute changes in perfusion variables and vascular tone after energy drink intake, rather than immediate major cardiovascular events, when one or a few cans were administered under controlled conditions [35,36]. Experimental work and observational data further indicate that high caffeine concentrations and the interaction between caffeine and taurine can promote arrhythmias and hypertension, especially in individuals with high habitual intake [22,27,37]. Together, these findings suggest a continuum of cardiovascular effects ranging from transient hemodynamic alterations in controlled scenarios to severe, though less frequent, complications in high-risk patterns of use [34,35,36,42]. Complementing these findings, a recent cross-sectional study in German adolescents with chronic high energy drink consumption did not observe significant differences in standard cardiological parameters when compared with non-consumers, but approximately half of the high consumers reported cardiovascular symptoms such as palpitations or chest pain after energy drink intake and showed higher rates of alcohol use, smoking and short sleep duration [21]. These observations underline that co-occurring behaviours such as alcohol use, smoking and short sleep duration may act as important confounding factors when interpreting the cardiovascular impact of energy drink consumption in adolescents [21].

At the electrophysiological and molecular level, the typical components of EDs also favor cardiac arrhythmias and other electrical disturbances. In ex vivo cardiac models, the combination of caffeine and taurine, present in most EDs, has been reported to facilitate the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias [37]. This effect is explained by the fact that, in addition to blocking A1/A2A adenosine receptors, caffeine at high doses stimulates intracellular calcium release and inhibits cardiac phosphodiesterases, increasing myocardial excitability and the risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. These mechanisms support cases of malignant arrhythmia and sudden death reported after excessive caffeine consumption and suggest the need for stricter monitoring, especially in young ED consumers. Moreover, although there is no direct evidence of cardiac remodeling in adolescents, it is postulated that sustained intake of these beverages could lead to insidious chronic effects. Prolonged consumption has been highlighted as imposing a cardiovascular overload capable of leading to ventricular dysfunction, particularly altered diastolic relaxation [35]. This raises the concern that, over time, ED abuse could contribute to progressive myocardial hypertrophy and deterioration of systolic function in habitual consumers. In sum, electrophysiological and functional findings converge in warning that both acute and chronic exposure to EDs can compromise the electrical stability of the myocardium and overall cardiac function.

Complementarily, the biochemical and cellular effects observed provide biological plausibility for these risks. It is not only isolated caffeine that is responsible, but also the synergistic biochemical environment generated by EDs. For example, the combination of caffeine, taurine, and sugars induces oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. In human endothelial cells, this mixture has been shown to create a pro-oxidant milieu, compromising nitric oxide release and vascular tone [46]. This redox imbalance can trigger chronic inflammation and progressive deterioration of vascular function. In a complementary manner, preclinical studies show damage at the level of cellular energy. Repeated exposure to ED mixtures has been found to alter mitochondrial phosphorylation and increase markers of oxidative stress, reducing bioenergetic efficiency and provoking structural damage in cardiovascular tissues [45]. One worrisome aspect is the extremely high dose of certain additives. A single can of an ED can contain up to 3180 mg of taurine, well above recommended physiological limits [40]. This excess taurine, combined with caffeine, often more than 300 mg per can, and large glucose loads, has been shown in experimental models of caffeine and caffeine–sugar exposure to promote neuronal overstimulation and excitotoxic stress that challenge cellular protective mechanisms [58,59]. Even the notion that frequent moderate consumption would be safe has been challenged. In animal models, relatively moderate doses of taurine and caffeine already induce detectable cardiovascular alterations. Thus, in biochemical terms, EDs constitute a cocktail capable of harming the endothelium, myocardium, and metabolism, especially when ingested in high amounts or on a repeated basis.

In addition to these direct cardiovascular actions, experimental evidence indicates that high concentrations of caffeine and sugars in the gastrointestinal tract can disturb gut homeostasis and initiate metabolic cascades that communicate with peripheral tissues and the central nervous system. Such alterations in the intestinal environment have been associated with changes in mood, cognitive performance, and stress responses, suggesting that the ingredients of energy drinks may also influence cardiovascular risk indirectly through the gut–brain axis [60,61,62].

Consistent with the above, clinical reports of severe adverse events have emerged in young ED consumers that challenge the idea of harmlessness. A paradigmatic case involves a previously healthy adolescent who suffered a spontaneous dissection of the posterior cerebral artery after excessive caffeine consumption, demonstrating that the vasoconstrictive and hemodynamic effects of EDs can extend to the cerebral circulation [42]. This type of finding has led to the suggestion that ED intake be considered within the differential diagnosis of unexplained ischemic events in pediatric populations. Similarly, it has been warned that the combination of caffeine and taurine can trigger potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias even in young individuals without cardiac history, reinforcing concerns about sudden death associated with these beverages [37]. Although extreme cases such as these are not frequent, their mere existence underscores that ED consumption carries serious acute risks, and not only transient discomfort, in susceptible individuals However, it is important to note that most of the evidence discussed in this section comes from observational designs and case reports. Therefore, although these findings strongly suggest potential harm, the causal relationship between ED consumption and these severe outcomes cannot be firmly established, and results should be interpreted with caution.

Paradoxically, despite growing evidence, adolescent consumption patterns have not changed substantially. A concerning gap between knowledge and behavior is observed. Many young people recognize the risks in theory, but few adjust their behavior. Survey data indicate that nearly 70% of adolescents know that EDs can cause hypertension; however, only 22% reduce their consumption after learning about these dangers [29]. This disconnect suggests a phenomenon of cognitive dissonance, in which cultural, academic, and commercial factors drive young people to minimize risk in practice. In settings of high academic or occupational demand, EDs have been normalized as “aids” for performance. It has been warned that an institutional culture of overload legitimizes the routine use of these beverages as a tool for student or work survival, fostering dependence, sleep disorders, and a vicious circle of increasing consumption [52]. Thus, external pressures and the pursuit of performance contribute to the fact that, even knowing the potential harm, many adolescents and young adults do not change their ED consumption habits.

Another structural factor that hinders prevention is low critical health literacy in youth segments. Most adolescents do not read labels or adequately understand the warnings on these products [54]. The lack of understanding about the composition, doses, and cumulative effects of EDs means that consumption decisions are based more on social perceptions and marketing than on scientific information. This educational gap is exploited by advertising. Commercial strategies link ED consumption to ideas of success, vitality, or social acceptance, reinforcing the mistaken perception that these are safe or even beneficial products. Specifically, many young people underestimate the real risks of EDs due to an environment that combines insufficient information, seductive advertising, and ineffective regulation.

In this context, regulatory gaps play a critical role. The lack of strict regulations and surveillance facilitates the marketing of EDs without controls proportional to their risks. ED manufacturers do not always accurately declare the actual amounts of taurine or other stimulants in their products [40]. In addition, many laws classify EDs as dietary supplements, allowing them to circumvent stricter regulations applied to substances with pharmacological potential [27]. This combination of industrial opacity and legal loopholes results in weak oversight. The situation is particularly concerning in regions such as Latin America, where there is a lack of specific labeling and regulatory standards for EDs. Some commercial presentations reach extraordinary concentrations, up to 300 mg of caffeine and more than 2000 mg of taurine per can, far exceeding international recommendations [45]. This cocktail of caffeine, taurine, and sugar at such high doses not only impacts the cardiovascular system but also exerts negative synergistic effects on the central nervous system and metabolism. The gap between market reality and the absence of regulatory limits leaves adolescents particularly exposed, since they are more vulnerable and less critical regarding the content of these products.

In the face of these challenges, multisectoral intervention strategies are emerging that could mitigate the problem if applied jointly. An encouraging experience comes from the fiscal realm. In Saudi Arabia, the implementation of a tax on EDs and sugar-sweetened beverages significantly reduced their consumption, especially among adolescents [32]. This result suggests that economic measures can be effective when integrated with other public health policies. Indeed, the authors reviewed concur in recommending a comprehensive approach. On the one hand, health education from early ages should go beyond merely informing, building critical literacy so that young people can identify risks, question advertising, and make informed decisions [25]. However, the evidence synthesized in this review also suggests that isolated educational interventions, without simultaneous regulatory and fiscal measures, have limited impact on reducing consumption, which helps explain why education alone is often perceived as a more acceptable option by industry. At the same time, explicit graphic warnings on ED labels, similar to those used on cigarette packages, are advocated to highlight potential harms [54], as well as strict control of advertising, especially on social networks and platforms frequented by minors [40]. These educational and regulatory actions should be complemented by the active involvement of the health system, incorporating screening for ED consumption into routine clinical evaluations, for example before medical procedures or in checkups of young athletes, and strengthening epidemiological surveillance of associated adverse events. The articulation of these educational, regulatory, fiscal, and healthcare measures would help create a safer environment and reduce the social normalization of a potentially harmful habit. Although contrary to what might be expected, studies in adults such as that by [4] found that caffeine has protective effects against some diseases, such as kidney dysfunction and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nevertheless, they also noted that it increases the risk of acute hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Finally, when the body of evidence is considered as a whole, the 33 studies included in this review converge on a similar pattern. Most empirical investigations focused on adolescents and young adults, which are the population groups with the highest prevalence of energy drink consumption, and examined beverages characterized by high caffeine content, often combined with taurine and substantial sugar loads. The most frequently reported cardiovascular outcomes were acute increases in blood pressure and heart rate, alterations in hemodynamic or vascular parameters, and, in a smaller subset of case reports and clinical series, severe events in susceptible individuals. This overall pattern reinforces the interpretation that energy drinks should not be treated as neutral soft drinks, but as products with a pharmacological profile that may entail cardiovascular risk under certain patterns of use.

5. Implications

In clinical practice, healthcare professionals could incorporate the assessment of energy drink consumption as a routine component of the cardiovascular history, particularly in adolescent and young adult patients. Early identification of this habit allows for counseling on moderation or abstinence in individuals with risk factors or a history of hypertension, arrhythmias, or other cardiac conditions. In addition, clinicians should explicitly warn about the dangers of combining energy drinks with alcohol or with intense physical exercise, as these practices may potentiate the risk of malignant arrhythmias, ischemic events, and other complications. In the educational setting, the reviewed studies highlight the need to implement comprehensive health education programs in schools (health literacy) and universities that provide objective information on the adverse cardiovascular effects of energy drinks.

From a public health perspective, strengthening regulations on energy drinks is a priority to reduce exposure among vulnerable populations. An immediate measure is to establish age restrictions for purchasing these beverages, preventing unrestricted access to minors. Advertising and promotion should also be regulated, with particular emphasis on marketing strategies targeting children and adolescents. It is equally imperative to require clear and visible labeling on packaging, including explicit health warnings about potential cardiovascular risks, similar to those used for other harmful products such as tobacco. Regulatory agencies should increase surveillance of the contents of energy drinks available on the market, verifying the accuracy of nutritional information and setting maximum permissible limits for ingredients such as caffeine and taurine. Additionally, fiscal policies such as the application of specific taxes on energy drinks and sugar-sweetened beverages could serve as effective deterrents, reducing consumption as observed in some international experiences.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Interpretation of the findings of this review should take into account several limitations of the current evidence base. First, the 33 studies included in this analysis encompass a broad methodological spectrum, ranging from observational surveys and short term clinical studies to experimental research, clinical reviews and case reports, which limits the possibility of establishing robust causal relationships between energy drink consumption and cardiovascular outcomes. Second, there is substantial heterogeneity in age ranges, settings, exposure conditions and in the specific formulations and doses of energy drinks evaluated, making direct comparisons across studies difficult and hindering the definition of clear safety thresholds for young consumers. Moreover, many of the available studies do not fully control for co-occurring behaviours such as alcohol use, smoking and short sleep duration, which may confound the observed cardiovascular outcomes and make it difficult to isolate the independent contribution of energy drink consumption. Third, some population groups and regions, particularly adolescents and young adults from Latin American countries, remain underrepresented in the literature, so generalization of the present findings to all sociocultural contexts must be made with caution. Finally, the decision to include only open access publications may have resulted in the omission of relevant studies published in subscription-based journals; this choice was made to ensure full-text accessibility and transparency and should be considered when interpreting the generalizability of the results.

To address these limitations, large-scale longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effects of chronic energy drink consumption and to establish stronger causal relationships. Future research could address the critical gap in age stratification; that is, cohort studies in adolescents and young adults could provide valuable data on the progression from subclinical alterations (such as hemodynamic changes or benign arrhythmias) to potential severe cardiovascular events in adulthood, with a special focus on underrepresented populations and regions (Latin America), to better understand the influence of sociocultural factors on consumption patterns and susceptibility to effects.

From a mechanistic standpoint, future investigations should deepen the analysis of the interaction of energy drink components in the human body, validating in real subjects the findings from cellular and animal models that suggest pro-arrhythmic, metabolic, and pro-inflammatory effects. It would also be relevant to explore harm-mitigation strategies, such as assessing whether reformulation of these products (by reducing stimulant concentrations) or the co-administration of protective supplements such as antioxidants can lessen their negative health impact.

In addition, the heterogeneity in how age ranges, ingredient compositions, and outcomes were reported across studies did not allow us to construct a standardized quantitative matrix by age group and specific ED components, so the patterns described in this review should be interpreted as a qualitative synthesis rather than a comparative meta-analysis

7. Conclusions

This review synthesizes recent evidence on the cardiovascular effects of energy drink consumption among young populations, showing that even occasional intake can produce acute increases in blood pressure, electrical conduction disturbances, and oxidative stress. It also identifies specific ingredients and consumption patterns that raise risk among vulnerable groups.

Together, these findings highlight the need to strengthen consumer education, improve ingredient and sales regulation, and promote longitudinal research to better understand long-term effects. Overall, the evidence underscores the importance of addressing this issue through preventive and public health-oriented strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/beverages12010004/s1, File S1: Thematic Categories; File S2: Categories of Proposals and Contributions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.M.-S., C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; methodology, E.J.M.-S.; software, E.J.M.-S., C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; validation, E.J.M.-S., C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; formal analysis, E.J.M.-S., C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; investigation, C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; resources, E.J.M.-S., C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; data curation, C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; writing—original draft, C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A.; writing—review & editing, E.J.M.-S.; visualization, E.J.M.-S.; supervision, E.J.M.-S.; project administration, E.J.M.-S., C.A.G.-B., L.C.G.-A., M.A.H., K.C.M., and M.L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No financial support was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article and its Supplementary Materials. Specifically, Supplementary File S2 provides the thematic categories identified through the analysis, and Supplementary File S3 presents the categories of proposal and contribution. All Supplementary Materials are available with the published version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used NAPKIN for the design and generation of scientific figures and graphical representations, and AI-based tools exclusively for language editing and improvement of clarity. All outputs from these tools were carefully reviewed, edited, and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content, figures, and interpretations presented in this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Vercammen, K.A.; Koma, J.W.; Bleich, S.N. Trends in Energy Drink Consumption Among U.S. Adolescents and Adults, 2003–2016. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikoff, D.; Welsh, B.T.; Henderson, R.; Brorby, G.P.; Britt, J.; Myers, E.; Goldberger, J.; Lieberman, H.R.; O’Brien, C.; Peck, J.; et al. Systematic review of the potential adverse effects of caffeine consumption in healthy adults, pregnant women, adolescents, and children. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 585–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobierajski, T.; Surma, S.; Romańczyk, M.; Banach, M.; Oparil, S. Knowledge of Primary Care Patients Living in the Urban Areas about Risk Factors of Arterial Hypertension. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, H.; Basalely, A.; Singer, P.; Castellanos, L.; Frank, R.; Sethna, C.B. Caffeine intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents in the United States. Pediatr. Res. 2025, 97, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijeiro, A.; Pérez-Ríos, M.; García, G.; Martin-Gisbert, L.; Candal-Pedreira, C.; Rey-Brandariz, J.; Guerra-Tort, C.; Varela-Lema, L.; Mourino, N. Consumption of energy drinks among youth in Spain: Trends and characteristics. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; McGuire, L.C.; Galuska, D.A. Regional Differences in Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake among US Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1996–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalese, M.; Cerrai, S.; Benedetti, E.; Colasante, E.; Cotichini, R.; Molinaro, S. Combined alcohol and energy drinks: Consumption patterns and risk behaviours among European students. J. Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaim, A.; Safi, A. Exploring Sedentary and Nutritional Behaviour Patterns in Relation to Overweight and Obesity Among Youth from Different Demographic Backgrounds in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malobická, E.; Zibolenová, J.; Baška, T.; Bakalár, P.; Madleňák, T.; Štefanová, E.; Ulbrichtová, R.; Hudečková, H. Differences in frequency of selected risk factors of overweight and obesity in adolescents in various social environments within Slovakia. Public Health 2025, 240, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalle-Uhlmann, T.; Buijsse, B.; Bergmann, M.; Knüppel, S.; Kühn, T.; Katzke, V.; Kaaks, R.; Boeing, H. Circadian patterns of beverage consumption within the EPIC-Germany cohorts. Ernahr. Umsch. 2016, 63, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Owolabi, M.O.; Feigin, V.L.; Abd-Allah, F.; Akinyemi, R.O.; Bhattacharjee, N.V.; Brainin, M.; Cao, J.; Caso, V.; Dalton, B.; et al. Pragmatic solutions to reduce the global burden of stroke: A World Stroke Organization–Lancet Neurology Commission. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 1160–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandilaras, G.; Li, P.; Dalla-Pozza, R.; Jakob, A.; Haas, N.A.; Oberhoffer, F.S. Impact of Acute Energy Drink Consumption on Heart Rate Variability in Children and Adolescents. A Randomized Trial. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.A.; Szeto, A.H.; Farewell, R.; Shek, A.; Fan, D.; Quach, K.N.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Elmiari, J.; Chan, W.; O’Dell, K.; et al. Impact of High Volume Energy Drink Consumption on Electrocardiographic and Blood Pressure Parameters: A Randomized Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto, A.C.V.; Freitas-Silva, O.; da Rosa, J.S.; Gottschalk, L.M.F. Estimated acrylamide intake from coffee consumption in Latin America. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2015, 10, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolis, A.A.; Manolis, T.A.; Apostolopoulos, E.J.; Melita, H.; Manolis, A.S. The Cardiovascular Benefits of Caffeinated Beverages: Real or Surreal? “Metron Ariston-All in Moderation”. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 2235–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anty, R.; Marjoux, S.; Iannelli, A.; Patouraux, S.; Schneck, A.S.; Bonnafous, S.; Gire, C.; Amzolini, A.; Ben-Amor, I.; Saint-Paul, M.C.; et al. Regular coffee but not espresso drinking is protective against fibrosis in a cohort mainly composed of morbidly obese European women with NAFLD undergoing bariatric surgery. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamia, C.; Lagiou, P.; Jenab, M.; Trichopoulou, A.; Fedirko, V.; Aleksandrova, K.; Pischon, T.; Overvad, K.; Olsen, A.; Tjønneland, A.; et al. Coffee, tea and decaffeinated coffee in relation to hepatocellular carcinoma in a European population: Multicentre, prospective cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulli, A.; Smith, R.M.; Kubatka, P.; Novak, J.; Uehara, Y.; Loftus, H.; Qaradakhi, T.; Pohanka, M.; Kobyliak, N.; Zagatina, A.; et al. Caffeine and cardiovascular diseases: Critical review of current research. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Tuttle, T.D.; Higgins, C.L. Energy Beverages: Content and Safety. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhoffer, F.S.; Dalla-Pozza, R.; Jakob, A.; Haas, N.A.; Mandilaras, G.; Li, P. Energy drinks: Effects on pediatric 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. A randomized trial. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, J.; Spinka, F.; Pie, M.J.; Deichl, A.; Knüppel, S.; Ehlers, A.; Nagl, B.; Edelmann, F.; Weikert, C. Chronic high consumption of energy drinks and cardiovascular risk in adolescents—Results of the EDKAR-study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2025, 40, 1355–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammone, M.A.; D’Orazio, N. Cocoa overconsumption and cardiac rhythm: Potential arrhythmogenic trigger or beneficial pleasure? Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 9, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, A.V.; Pennella, S.; Farinetti, A.; Manenti, A. Energy Drinks and atrial fibrillation in young adults. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1073–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, F.J.; Teixeira, R.; Poínhos, R. Dietary Habits and Gaming Behaviors of Portuguese and Brazilian Esports Players. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, M.; Ohadi, L.; Changizi, F.; Seyed, S.; Farjam, M. The risk of premature cardiac contractions (PAC/PVC) related to caffeine consumption among healthcare workers: A comprehensive review. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puupponen, M.; Tynjälä, J.; Tolvanen, A.; Välimaa, R.; Paakkari, L. Energy Drink Consumption Among Finnish Adolescents: Prevalence, Associated Background Factors, Individual Resources, and Family Factors. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 620268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balawejder-Bisto, A.; Pyka-Pająk, A. Caffeine—A substance well known or still researched | Kofeina–Substancja znana czy poznawana. Farm. Pol. 2022, 78, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Sánchez, E.J.; Alanya-Pereyra, L.L.; Ochoa-Tataje, F. Public policies and their association with adolescent pregnancy in Southern Peru. Reprod. Health 2025, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.E.; Gharaibeh, F.A.; Islam, M.R.; Abdelrahim, D.; Saif, E.R.; Turki, E.A.; Al-Kitbi, M.K.; Abu-Qiyas, S.; Zeb, F.; Hasan, H.; et al. Caffeinated energy drink consumption among Emirati adolescents is associated with a cluster of poor physical and mental health, and unhealthy dietary and lifestyle behaviors: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1259109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekkey, S.M.; Tizkam, H.H. The prevalence rate of energy drinks consumption among young adults in Iraqi society. Med. J. Babylon 2022, 19, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, G.; Sayinbatur, B.; Caynak, M. Use of energy drinks among children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Eurasian J. Fam. Med. 2021, 10, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaadi, A.M.; Turki, A.; Gazzaz, A.Z.; Al-Qahtani, F.S.; Althumiri, N.A.; BinDhim, N.F. Soft and energy drinks consumption and associated factors in Saudi adults: A national cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1286633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, J.; Reimer, R.A.; Hittel, D.S.; Gault, M.A.; Vogel, H.J.; Klein, M.S. Caffeine-containing energy shots cause acute impaired glucoregulation in adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagim, A.R.; Harty, P.S.; Tinsley, G.M.; Kerksick, C.M.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Kreider, R.B.; Arent, S.M.; Jager, R.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Stout, J.R.; et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Energy drinks and energy shots. J. Int. Soc. Sport. Nutr. 2023, 20, 2171314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, N.E.; Michalak, M.; Dreier, K.; Babst, D.; Lardi, A.M.; Farhadi, J. Effect of the Red Bull Energy Drink on Perfusion-Related Variables in Women Undergoing Microsurgical Breast Reconstruction: Protocol and Analysis Plan for a Prospective, Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e38487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, D.; Hamm, W.; Kellnar, A.; Brunner, S.; Stremmel, C. Comparable Analysis of Acute Changes in Vascular Tone after Coffee versus Energy Drink Consumption. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellermann, C.; Hakenes, T.; Wolfes, J.; Wegner, F.K.; Willy, K.; Leitz, P.; Rath, B.; Eckardt, L.; Frommeyer, G. Cardiovascular risk of energy drinks: Caffeine and taurine facilitate ventricular arrhythmias in a sensitive whole-heart model. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2022, 33, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, F.Z.; Babaev, N.M.; Shikhieva, L.S. Features of coronary artery patterns and percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome and stable angina in patients aged below 40 years | Осoбеннoсти пoражения венечных артерий и эндoваскулярнoй реваскуляризации миoкарда при. Kazan Med. J. 2020, 101, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašalić, A.; Šegalo, S.; Maestro, D.; Čaušević, A.; Suljović, A. Quantification of some additives in energy drinks using high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Health Sci. 2022, 12, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalova, P.; Salaskova, D.; Csicsay, F.; Galba, J.; Kovac, A.; Piestansky, J. Determination of taurine in soft drinks by an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method. Eur. Pharm. J. 2023, 70, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.S.; Chen, Z.; Blanchette, A.D.; Zhou, Y.H.; Wright, F.A.; Baker, E.S.; Chiu, W.A.; Rusyn, I. Relationships between constituents of energy drinks and beating parameters in human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-Derived cardiomyocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 149, 111979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staikoglou, N.; Polanagnostaki, A.; Lamprou, V.; Chartampilas, E.; Pavlou, E.; Tegos, T.; Finitsis, S. Posterior cerebral artery dissection after excessive caffeine consumption in a teenager. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 2081–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serfling, S.E.; Buck, A.; Rowe, S.P.; Higuchi, T.; Werner, R. Red Bull PET/CT. Nuklearmedizin 2023, 63, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendak, S.; Elbarazi, I.; Alajlouni, O.; Al-Rawi, S.O.; Samra, A.M.B.A.; Khan, M.A.B. Examining shift duration and sociodemographic influences on the well-being of healthcare professionals in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1517189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livengood, E.J.; Fong, R.; Pratt, A.M.; Alinskas, V.O.; Gorder, G.V.; Mezzio, M.; Mulligan, M.E.; Voura, E.B. Taurine stimulation of planarian motility: A role for the dopamine receptor pathway. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Fernández, M.; Valenzuela-Gómez, F.; Font, R.; Río-Celestino, M.D.; Merinas-Amo, T.; Alonso-Moraga, Á. In vivo and in vitro assays evaluating the biological activity of taurine, glucose and energetic beverages. Molecules 2021, 26, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muslhi, A.S.M.; Ali, L.H. Assessing the Impact of Pomegranate Juice on Liver Tissue in Male Rats Exposed to a Commercial Energy Drink. J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Sci. 2024, 12, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafar, S.N. Changes in biochemical and sperm parameters of rats drinking energy drinks. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2024, 70, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyina, R.; Dodoala, S.; Gindi, S.; M, P.R.; Desu, P.K. Insights of In-silico Neurotoxicity Studies of Glucuronolactone, Taurine and Gluconolactone Correlating the Induced Neuronal Alteration in Rat Pups. Int. J. Drug Deliv. Technol. 2023, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneri, L.T.; Mamo, J.C.L.; D’alonzo, Z.; Lam, V.; Takechi, R. Chronic intake of energy drinks and their sugar free substitution similarly promotes metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltahir, H.M.; Alamri, G.; Alamri, A.; Aloufi, A.; Nazmy, M.; Bahashwan, S.; Elbadawy, H.M.; Alahmadi, Y.M.; Abouzied, M.M. The metabolic disorders associated with chronic consumption of soft and energy drinks in rats. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2020, 67, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdos, Á. Coffee, Energy Drinks Consumption and Caffeine Use Disorder Among Law Enforcement College Students in Hungary. Eur. J. Ment. Health 2023, 18, e0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.I.; Mobarki, S.J.; Oberi, I.A.; Omar, Y.Z.; Moafa, S.H.; Ayoub, R.A.; Ajeebi, Y.; Hakami, F.; Hakami, A.; Somaili, M. Effect of Stress on Sleep Quality among Medical Students: A Cross-sectional Study at Jazan University, Saudi Arabia. Ann. Afr. Med. 2024, 23, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]