Abstract

Large outcrops of ophiolites from exposed land surfaces can potentially impact the geochemistry of much greater areas through transport and weathering. Derived soil and sediments contain significant concentrations of heavy metals, including chromium and nickel. In the context of environmental risk analysis, there is a necessity to obtain more information about the distribution of Cr and Ni in serpentine rocks and their derived associated geological matrices, and about how easily Cr could be released and then oxidized in the environment, causing pollution of groundwater. The aim of this study was to evaluate the distribution of Cr and Ni in the geochemical fractions containing Fe and Mn and the role of Fe and Mn oxides (crystalline and non-crystalline) in redox processes leading to the formation of Cr(VI) during serpentine soil weathering. Through the combination of chemical selective sequential extraction (SSE) and X-ray diffraction, solid samples belonging to ophiolitic rocks and their derived soils and sediments in southern Tuscany were investigated. The applied SSE method followed the established extraction scheme commonly used in sequential selective extraction procedures. The extraction was accomplished in seven successive steps, using appropriate reagents to destroy the binding agents between the target metal and the specific soil fraction to release the heavy metals selectively from their structural context. The results indicated significant differences in the availability and mobility of Cr and Ni in soils, with Cr concentrations ranging from 200 to 950 μg/g and Ni from 274 to 665 μg/g in reactive fractions. Cr is tightly bound to well-crystallized Fe-oxides and primary rock-derived phases, whereas Ni is substantially more mobile, being mainly controlled by Mn-oxides and amorphous Fe-oxides. Weakly acidic solutions or systems with high redox potential increase Cr and Ni mobility in the environment due to Fe/Mn hydroxides produced by the weathering of serpentinites. An ORP higher than 1000 mV leads to the formation of Cr(VI) by oxidation of Cr(III), increasing the mobility of Cr in groundwater and the hazard for human health. The analytical activity carried out in this research can be used to identify the potential risk of Cr(VI) release in groundwater from serpentine and derived geomaterials.

1. Introduction

Heavy metal and trace metal contamination of soil and waters is one of the most important environmental concerns. In particular, Cr and Ni are potentially toxic elements and are among the most widespread heavy metals in the environment because of their industrial and commercial uses Consequently, their extensive use has resulted in soil and water contamination worldwide [1,2,3]. Globally, serpentinite rocks are widespread, occurring in regions such as the Alps, California Coast Range, and New Caledonia, covering thousands of square kilometers. In Europe, the median soil values of Cr and Ni are 64 and 21 mg/kg, respectively [4]; while ultramafic parent materials (e.g., serpentinite) are associated with high levels of toxic trace elements, particularly Cr and Ni (1800 and 2000 ppm on average, respectively [5]. Soils developed over serpentinite show the highest Cr and Ni concentrations; these can adversely affect the environment and human health after being mobilized by weathering into soil, water, and dust [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Chromium and nickel speciation and mobility in ultramafic environments remain critical topics in environmental geochemistry due to these metals’ influence on soil and water quality and their potential ecological risks.

Recent research emphasizes the complexity of these processes, particularly the oxidation of Cr(III) to the more toxic Cr(VI) species and its retention within serpentinite matrices [12,13,14,15,16]. Such transformations are driven by interactions with manganese and iron oxides, which act as oxidizing agents under specific geochemical conditions. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for predicting contaminant behavior and informing remediation strategies in areas affected by ultramafic lithologies.

Chromium exists in two main oxidation states in the environment: Cr (III) and Cr (VI). These show different geochemical and biological behaviors, as well as different toxicities for human and aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. In particular, Cr (III) is recognized as an essential trace element in mammals, exhibits low solubility under circumneutral pH conditions, and is efficiently sorbed onto Fe oxides. In comparison, Cr (VI) is highly soluble in water; it is a powerful oxidant and is classified as a mutagen, teratogen, and carcinogen [17]. Most Cr exists as Cr (III) in serpentinites, but redox reactions may lead to oxidation of Cr (III) to Cr (VI), significantly contributing to natural inputs of Cr (VI) in the environment [18,19]. High concentrations of naturally occurring Cr (VI) have been reported in groundwater in close proximity to mafic/ultramafic rocks and soils, indicating that there is potential for redox cycling to occur in Cr(III)-dominated systems [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Most of these studies show that Cr (VI) in groundwater is related to the occurrence of ultramafic rocks and is associated with alkaline and oxidizing conditions in aquifers [27,28].

Nickel is thought to be one of the most mobile heavy metals found in the natural soil environment [29]. Nickel in the soil solid phase appears on exchange sites, specific adsorption sites, adsorbed or occluded into sesquioxides, within the mineral lattice, or bound to organic matter. Ni (II) is the dominant inorganic species throughout the pH and Eh ranges of most natural waters [30]. Approximately 50% of Ni in soils and sediments might be associated with the residual fraction and about 20% is in the Fe-Mn oxide fraction; the remaining part might be associated with the carbonate fraction, and the exchangeable and organic fractions [31,32]. Although considered an essential plant nutrient, elevated levels of Ni can be toxic to all living organisms, causing, among other illnesses, cancer in humans, as well as numerous skin disorders [33,34].

The mobility and potential toxicity of heavy metals in soils depend not only on their concentrations, but also on both their associations and chemical properties, the environmental conditions such as pH, redox potential, biological action of roots, and the formation of chelates [35,36,37,38]. For these reasons it is important to identify and quantify the geochemical form and speciation of metals in soil (easily exchangeable ions, metal carbonates, oxides, sulphides, organometallic compounds, ions in crystal lattices of minerals, etc.) to gain a more precise understanding of the potential and actual impact of heavy metals under natural conditions and transport mechanisms [39,40,41,42,43,44].

Chemical selective sequential extraction (SSE) is a very useful technique [45] that has been frequently employed to determine metal distributions among operationally defined geochemical fractions in soils, sediments, and waste materials [46]. SSE employs progressively stronger and appropriate reagents to destroy the binding agents between the target metal and a specific soil fraction and release heavy metals selectively from their structural context [47]. However, fractions should be interpreted with extreme care. But despite several pitfalls inherent to the application of sequential extraction schemes [48], their value is generally recognized [49]. Numerous sequential extraction methods are used at present for soils and sediments, and they differ according to the type of reagent used, the experimental conditions applied, and the number of steps involved [50,51,52]. The sequential extraction method described by La Force and Fendorf [53] has been followed in the current study. This method is specially adapted to underline the metal contribution from crystalline and non-crystalline Fe-Mn oxides and the effect of different redox conditions, which is fundamental for the mobility of Cr from serpentine [54].

Serpentinite rocks and serpentine soils are relatively common in Italy, where they occur in metamorphic sequences in the Central and Western Alps and in Calabria. They also appear in the core of the Jurassic sedimentary cover in the Northern Apennines, and as blocks in chaotic mélanges in the Northern and Central Apennines. The Tuscany and Cecina basins particularly are characterized by numerous large outcrops of ophiolites, covering approximately 70 km2 [55] of the exposed land surface, that can potentially impact the geochemistry of much greater areas through transport and weathering. Previous works have underlined the presence of a high content of total Cr in soils and Cr (VI) contents in waters related to ultramafic rocks from coastal Tuscany [56,57,58]. These works describe the total content of Cr and Ni in rocks, soils, and sediments, but no information is given about their distribution in the solid materials in relation to their oxidation state. Hence, there is a necessity to obtain more information about the distribution of Cr and Ni in the serpentinite rocks and their associated geological matrices, and about how easily the Cr could be released and then oxidized in the environment, causing pollution of the groundwater.

The objective of this research was to evaluate, using SSE, (a) the distribution of Cr and Ni in the geochemical phases containing Fe and Mn; (b) the role of Fe and Mn oxides (crystalline and non-crystalline) in redox processes that lead to the formation of Cr (VI) during serpentine soil weathering; (c) the definition of a test for identifying the potential risk of release of Cr (VI) into groundwater from serpentine and associated geological matrices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequential Extraction Procedures

The sequential extraction procedures employed in this study follow widely accepted protocols for assessing trace metal partitioning in soils and sediments. These methods have been successfully applied in recent investigations of Cr and Ni mobility in serpentinite-derived soils and lateritic deposits [15,59]. By fractionating metals into operationally defined pools, this approach provides insights into their potential bioavailability and environmental risk. The analytical framework adopted here ensures comparability with contemporary studies and strengthens the reliability of our interpretations.

2.2. Study Area Description

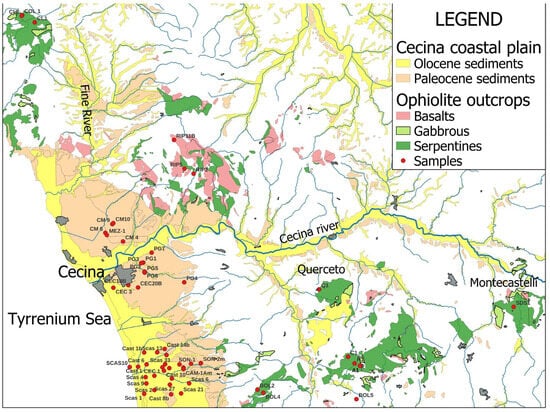

The study sites are located in central-western Tuscany, within two of the most significant ophiolitic outcrops of the region (Figure 1), and are situated far from any potential sources of anthropogenic pollution.

Figure 1.

Geological map of southern Tuscany and location of the study areas. The blue areas represent the main watercourses; the samples analyzed are shown with red dots.

The alluvial sediments are derived from Pleistocene and Olocene deposits of the Cecina coastal plain. The climate in the study area is Mediterranean, with hot and dry summers and mild, wet winters. The average minimum and maximum temperatures are 3 °C (January–February) and 30 °C (August), respectively. The average annual precipitation is about 800 mm.

Geologically, the area is characterized by a tectonic setting where sequences of deep marine clays, marls, and Cretaceous limestone (Ligurian Flysch Units to Eocene age) represent the sedimentary cover of underlying Jurassic ophiolites [60]. Tectonic units derived from the oceanic Ligurian Domain constitute the uppermost nappes of the Apennine orogenic stack, overlying a complex assemblage of Subligurian and Tuscan tectonic units.

In the study area, the Ligurides are represented by a complex stacking sequence, made up by several tectonic units that include ophiolites, sedimentary covers (cherts, limestones, and shales), and turbiditic sediments. The Cecina coastal plain, characterized by the presence of the Cecina and Fine rivers, is mainly made up of marine and continental deposits, middle–upper Pleistocene in age, overlying a thick clay horizon of the Lower Pleistocene [61]. The middle–upper Pleistocene deposits are represented by sands, sandstones, and conglomerates, with alternating thick layers of silt and clay. Reddish paleosols are often exposed at the surface. The Pleistocene sequence was cut relatively deeply (35 and 55 m near the Fine and Cecina river mouths, respectively) during the Wurm III sea-level lowering. The consequent depressions, which run along the river courses, were filled during the subsequent Versilian transgression by clastic deposits, represented by sands, gravels, and clay. These recent alluvial sediments are set in lateral contact with the middle–upper Pleistocene sequence. In this coastal plain, several wells and springwaters have been analyzed for Cr (total) and Cr (VI) concentrations by the regional Agency for Environmental Protection (ARPAT) and in previous works [56,58].

For this work, we selected the main serpentinite outcrops showing springwaters with varying total Cr (total) and Cr(VI) concentrations and hosting serpentinite-derived soils and sediments with different degrees of weathering. The sampled soils have been formed immediately above the ultramafic (serpentinite) parent rocks and are poorly developed. The middle Pleistocene sequence is represented by samples taken from the “Val di Gori Red Sands” formation [62], here formed by thin interlayers of fine-grained conglomerate in medium–coarse sands. In the study area, these sediments are characterized by a strong enrichment of ophiolite-derived fractions.

2.3. Sample Collection and Preparation

Soil samples developed on serpentinites and the topsoil of the plain were collected manually by scoop from the superficial parts at each site after clearing debris and vegetation (about 5 cm). The serpentinites and sediments were collected in exposed profiles and outcrops in the Cecina valley and coastal plain. The lithology attributed to each of them on the basis of the position in the field and a quick petrographic and mineralogical analysis is reported in Table 1. In addition to a chemical analysis, petrographic thin sections of selected serpentinite and sediment samples were investigated using optical microscopy. To prepare the thin sections, each sand sample was mixed with epoxy and allowed to set into a small block. Once the blocks hardened, they were treated as rocks and thin-sectioned. Polished thin sections were used for standard light microscope observation. An accurate description of the petrographic features of the ophiolite-derived sediments in Val di Cecina is reported in Laterza and Franceschini [55]. The samples were stored in polyethylene bags for transportation and storage and were air-dried at room temperature. Then, they were sieved through a 2 mm screen and pulverized in an agata mill. A total of 56 samples were readied for analytical activity. Two samples (PG5 and PG6) and two serpentine soils (QU1B and QU1C) were selected for SSE analysis. For comparison, two samples of unaltered serpentinite (SDS1 and QU2) were also selected for SSE in order to better understand how soils developed by the weathering of serpentinites can release Cr and Ni into the waters. The samples CAM-1Am and Son-2m represent the fine fraction (<2 mm) of the conglomerate samples CAM-1M and Son-2M, respectively.

Table 1.

XRF and aqua regia (ar) chemical data (Cr and Ni) of serpentinitic samples from Val di Cecina outcrops, alluvial sediments, and topsoil from Cecina coastal plain. (n.d. = not determined). Aqua regia digestion does not fully dissolve silicate-bound metals; it provides an estimate of environmentally available fractions rather than total content. This limitation was considered in interpreting results.

2.4. Total and Pseudo-Total Concentrations

An aqua regia pseudo-total digestion coupled to ICP-AES (inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry) was used to determine metal concentrations. The analyses were performed by the ARPAT laboratory. This method is not a total digestion technique for most samples. It is a very strong acid digestion that will dissolve almost all elements that could become “environmentally available”. By design, elements bound in silicate structures are not normally dissolved by this procedure as they are not usually mobile in the environment. Hg analytical determination was performed by cold-vapor atomic absorption (CV-AAS) using the Varian spectrometer CETAC Hg instrument. Aqua regia digestion does not fully dissolve silicate-bound metals; it provides an estimate of environmentally available fractions rather than total content. This limitation was considered in interpreting the results.

The samples were dried at 30 °C for 24 h. About 10 g of sample was pulverized and sieved through a 200 μm mesh. Powdered samples (0.3 g) were digested by a closed-digestion procedure in inverse aqua regia (9 mL of HNO3 (65%) and 3 mL of HCl (37%)). A microwave system was used to accomplish sediment digestion [63,64]. A series of blank samples using the same amounts of reagents was prepared and analyzed. After cooling, the resulting obtained solutions were diluted to 50 mL in volumetric flasks with MilliQ water (18.2 MΩ cm). After acid digestion of the samples, metal concentrations were determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) using the Varian Vista-MPX instrument and following the Apha Awwa WEF Standard Method 3120/2005 [65]. Some samples were analyzed in duplicate. The accuracy of the analytical procedures was checked by analyzing a multi-standard NIST-traceable certificate. Aqua regia digestion does not fully dissolve silicate-bound metals; it provides an estimate of environmentally available fractions rather than total content. This limitation was considered in interpreting the results.

The total concentrations of chromium, nickel, iron, and manganese were obtained by X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF) using a Philips PW 1450 spectrometer at the Earth Science Department of Pisa University. Component concentrations were determined according to Franzini et al. [66]. Soil samples were powdered to 30 μm grain size after air-drying and pulverization. Thereafter, the soils were made into 32 mm-diameter press-powder palettes by applying a pressure of 20 tonnes for 1 min to 1 g of sample against 6 g of pure boric acid powder. The accuracy of the XRF analysis was checked by using adequate international standards for rocks and minerals.

2.5. Selective Sequential Extraction

The use of SSE is based on the premise that chemical reagents can remove elements from specific fractions of the solid phase. Ideally, extractants are designed to selectively dissolve one mineralogical phase of the initial material, thus inducing the solubilization of associated metals.

Elements associated with the silicate matrix of the soil are considered non-labile and are presumed to be bound tightly in the silicate fraction. Primary and secondary minerals containing metals in the crystalline lattice constitute the bulk of the residual fraction. Its destruction is achieved by digestion with strong acids, such as HF, HClO4, HCl, and HNO3.

The SSE applied in this study follows a modified extraction scheme described by La Force and Fendorf [53]. The following operationally defined fractions were determined:

Fraction 1 (soluble): 10 mL of deionized water was added to 1 g (dry weight) of sample in 50 mL polyethylene centrifuge tubes and shaken continuously for 1 h at room temperature.

Fraction 2 (exchangeable): 10 mL of 1 M MgCl2 (pH 7) was added to the residues of step 1 and shaken continuously for 1 h at room temperature.

Fraction 3 (oxidizable): The residue was then exposed to 20 mL of 1 M NaOCl (pH 9.5) and digested for 1 h at 95 °C in an oven, and shaken manually every 15 min. The Eh of the solution was 1200 mV.

Fraction 4 (acid soluble): The resulting solid was then reacted with 20 mL of 1 M NaOAc-HOAc at pH 5.0 for 5 h, shaking continuously.

Fraction 5 (Mn oxides): 25 mL of 0.1 M NH2OH HCl in 0.01 M HNO3 adjusted to pH 2 was added to the solids from step 4 and shaken for 30 min at room temperature.

Fraction 6 (non-crystalline material): The residue was shaken with 20 mL of 0.2 M ammonium oxalate (AOD) at pH 3.0 in the dark for 4 h.

Fraction 7 (crystalline Fe-oxides): 30 mL of 1 M NH2OH HCl solution in 25% (v/v) HOac was added and then heated to 95 °C in an oven for 6 h, and shaken manually every 15 min.

After each extraction step, the supernatant was separated from the solid phases by centrifugation at a speed of 3000 rpm for 5 min, and filtration through a 0.45 μm acetate cellulose membrane. The supernatants were then acidified with HNO3 and analyzed using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) optical emission spectrophotometry (Perkin-Elmer ICP-OES Optima 2000) at the IGG-CNR laboratory in Pisa, with a 5% accuracy range, and quality control-checked every 15 samples. The leftover solids were washed with 5 mL of DI water, centrifuged, and the supernatant was discharged.

The SSE was limited to the heavy metals chromium, nickel, iron, and manganese. Extraction was carried out in triplicate to provide the precision of the measurement, which was found to be lower than 20%. To ensure the reproducibility of the results, the analysis sequence consisted of calibration of standards, blind standard solution analysis as an unknown (quality control solutions), and method blanks. Although the precision was below 20%, this is within acceptable limits for sequential extraction studies and does not compromise reliability.

The sum of the F1, F2, F3, and F4 fractions of the sequential extraction corresponds to the total content related to the potentially reactive fraction, considered to be the most important factor for the assessment of bioavailability and of the potential ecological risk [67,68]. The F1 + F2 fraction contains those weakly bound metals that are readily soluble in water or a slightly acidic medium.

3. Results

3.1. Total and Pseudo-Total Metal Content

The Cr and Ni concentrations for all samples, determined either by XRF analysis or by the aqua regia digestion method, are presented in Table 1.

Aqua regia digestion does not fully dissolve silicate-bound metals; it provides an estimate of environmentally available fractions rather than total content. This limitation was considered in interpreting the results.

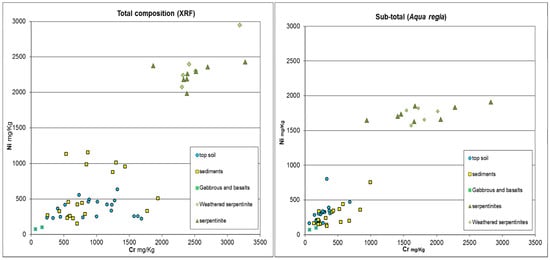

Serpentinites and their derived soil have nickel and chromium concentrations much higher than the deposits of the plain (topsoil and sediments), which are characterized by lower contents. Only sediments particularly rich in serpentinite fragments (conglomerates) have concentrations that are close to those of serpentinites. A comparison between total and sub-total analyses indicates that a substantial proportion of both nickel and chromium remains sequestered within the restitic fraction. This agrees with the mineralogical investigation that shows the presence of disseminated chromite crystals in the sediments of the plain.

The graphs of Figure 2, which report the data of Table 1, show the presence of a gap, especially for nickel, between the areas in the plots with sediments and with serpentinites. The reason for the lack of samples that fall in this range is not clear. It could be due to the lack of representativeness in the samples analyzed of sedimentary deposits close to the outcrops of serpentinite. This gap likely reflects limited sampling of intermediate sediments rather than a systematic bias. The selected samples represent the main lithologies and weathering stages observed in the area.

Figure 2.

Comparison between total (XRF) and sub-total (aqua regia) composition of Cr vs. Ni content in all samples studied. Aqua regia digestion does not fully dissolve silicate-bound metals; it provides an estimate of environmentally available fractions rather than total content. This limitation was considered in interpreting results.

3.2. Metal Speciation in Different Geochemical Fractions

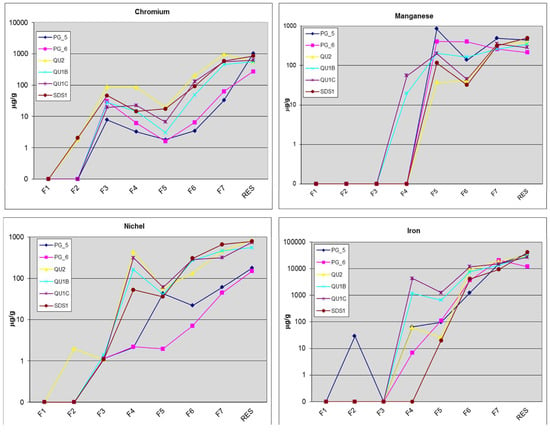

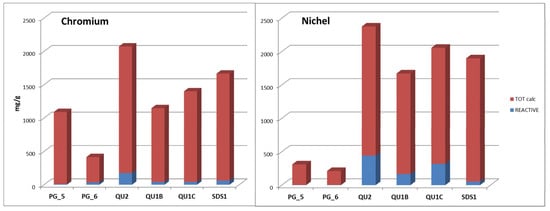

To assess the reactivity of the mineral phases capable of incorporating Cr and Ni, the leachates from each step of the SSE procedure were analyzed, and the corresponding results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Cr, Ni, Mn, and Fe extracted in each step of the sequential extraction procedure. F1 (easily soluble), F2 (exchangeable), F3 (oxidizable), F4 (acid soluble), F5 (Mn-oxides), F6 (non-crystalline), F7 (Fe-oxides), and RES (residual fraction).

The distributions of the average values of Cr, Ni, Fe, and Mn in the various geochemical fractions are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistical parameters derived from the values reported in Table 1 are summarized below.

The soluble and exchangeable fractions (F1 and F2) contain those weakly bound metals that are readily soluble in water or a slightly acidic medium. In general, the concentrations of metals in F1 and F2 are void in all samples except for the unaltered serpentinite QU2 and SDS1, where, however, the values are very low. The oxidizable fraction (F3) contains significant Cr concentrations, especially for non-sedimentary samples, signifying that this fraction holds a large part of this metal. Conversely, the other metals’ concentrations in this fraction are very low.

Similarly, the Cr and Ni concentrations of the carbonate fraction (F4) are relatively high for serpentine samples, with maxima of 86 μg/g and 440 μg/g, respectively, in QU2; whereas Mn associated with this fraction is low, especially for the serpentine soil samples (QU1B, QU1C).

The F5 (Mn-oxides) fraction in general does not contribute significantly to the total Cr and Ni contents, signifying that most of the metals are not associated with Mn-oxides, which are not well detected in these samples [57]. In the F6 fraction, the highest percentage of Fe was extracted in relation to the total Fe content, in particular for QU1C (12,031 μg/g). The Cr extracted in this fraction was 200 μg/g (QU2) and 131 μg/g (QU1C), and the Ni was 307 μg/g (SDS1), 290 μg/g (QU1C), and 274 μg/g (QU1B).

The F7 fraction exhibits markedly high metal concentrations, in particular for Cr in QU2 (950 μg/g) and Ni in SDS1 (665 μg/g), while remaining high in all samples. The residual fraction (F8) accounts for almost 50% of the total contents of Cr, Ni, and Mn for most of the samples studied. In particular, the largest amount of Cr is associated with the residual fraction in the sedimentary samples, followed by serpentine-derived samples.

In the sedimentary samples PG5 and PG6, the highest Cr concentrations are found in the crystalline Fe-oxide fraction (63 μg/g and 32 μg/g, respectively), whereas Cr is not extracted in the soluble, exchangeable, acid-soluble, and Mn-oxide fractions.

The Cr content in the oxidizable fraction is high in PG6, corresponding to 30 μg/g. In the PG5 sample, Ni is confined in Fe- and Mn-oxides, while in PG6 it is extracted in the F7 step only. The proportion of Cr in the residual phase of sample PG6 is the lowest relative to its total chromium content.

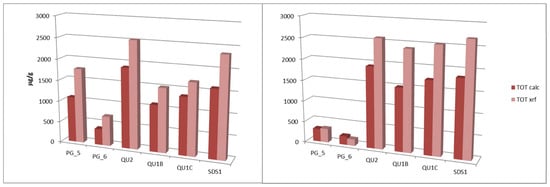

Figure 4 shows the total Cr content determined by XRF and the sum of the Cr extracted in the seven fractions.

Figure 4.

Total Cr content determined by XRF and the sum of the Cr extracted in the 7 fractions.

The total composition in all samples is systematically higher than the extracted fractions. This is because during the different steps in SSE, the leftover solids were washed with 5 mL of DI water, centrifuged, and the supernatant was discharged, in this way losing a fraction of the metals.

In the serpentine samples (residual soil and rocks), a significant fraction of Cr appears to be associated with the oxidizable and acid-soluble phases, which released 173, 42, 42, and 61 μg/g from QU2, QU1B, QU1C, and SDS1, respectively. The highest chromium content was detected in the crystalline Fe-oxide fraction.

In the SDS1 sample, high proportions of Ni were found in the residual fraction (782 μg/g) and in the crystalline Fe-oxide fraction (665 μg/g). The Ni released in the soluble and exchangeable fraction was low. In fact, the nickel release started only in the oxidizable fraction.

The metal contents in the reactive (F1 + F2 + F3 + F4) fraction are reported in Table 3. Cr and Ni the reactive fraction range from 11 and 3 μg/g in PG5 to 36 and 4 μg/g in PG6, respectively. High Cr and Ni reactivity is evident in the QU2 sample (443 μg/g) and it is still significant in the QU1B and QU1C samples (165 and 319 μg/g, respectively). Very high Fe-reactivity is evident in samples QU1B and QU1C (serpentinite-derived soils), with values of 1177 and 4343 μg/g, respectively.

Table 3.

Heavy metal (Cr, Fe, Mn, Ni) concentrations extracted using selective sequential extraction. Total composition is also reported. All values are in μg/g.

Figure 5 shows the total Cr and Ni contents, determined as the sum of the Cr extracted in the seven fractions, together with the Cr and Ni contents in the reactive fraction. The reactive fraction represents the more mobile fraction, which is potentially releasable in the environment under natural conditions. Considering the reactive fraction, relatively high contents of Cr were recovered in serpentine-derived samples. From the sedimentary samples, only PG6 presents a significantly reactive fraction. In all samples, the Ni reactive fraction is always higher than that of Cr.

Figure 5.

Total Cr and Ni contents determined as the sum of the Cr extracted by the 7 fractions, together with the Cr and Ni contents in the reactive fraction (F1 + F2 + F3 + F4).

4. Discussion

The analytical results of this work, and particularly those from the SSE, confirm that in the investigated samples Cr is less mobile than Ni, a well-known feature of serpentinite soils [7,8,11]. However, even though for Cr, and also for Ni, a high percentage of metals still remain in the residual fraction, the aqua regia-leachable metal fractions for QU2 (Cr) and for QU2, QU1B, and QU1C (Ni) will exceed the threshold limits fixed by legislation for non-industrial use in several countries, including Italy (120 and 150 μg/g, respectively). Most threshold limits refer to the aqua regia-extractable metal concentration, so in our case this threshold is exceeded easily in natural conditions, making our site potentially dangerous for Cr (VI) mobility. In particular, the acid-extractable content of Cr for sedimentary samples PG5 and PG6 is much higher (range 8–30 μg/g) than the content reported by Bonifacio et al. [69] for poorly developed alpine serpentinitic soils (range 0.1–0.8 μg/g). Acidic inputs such as acid rain could enhance Cr(VI) formation by increasing metal mobility and altering redox conditions, posing additional environmental risks in serpentinite-rich regions. Future work should quantify the relationships between metal mobility and soil parameters (pH, Eh, mineralogy) through statistical analysis to strengthen risk assessment.

As shown in the diagram of Figure 5, the total contents of Cr and Ni extracted by SSE and the reactive fraction are related to the total contents of the metals in the sample. Also, for all the samples, the Cr and Ni extracted by SSE generally increase with Fe content. Moreover, the reactive Cr and Ni are related to the reactive Fe and Mn. This indicates that these metals are associated with mineral fractions containing non-crystalline Fe/Mn hydroxides. Some authors have also reported that Fe-hydroxides could adsorb and retain labile Cr and Ni released by the weathering of serpentinites [70].

High contents of Cr and Ni are found in the F3 fraction following extraction with NaOCl in alkaline solution.

Generally, the extraction with NaOCl at a pH of 9.5 and 96 °C is considered to be very selective for organic matter, without dissolving Fe-Mn oxides and carbonates [48]. However, during this extraction some metals could be released that can precipitate as hydroxides at high pH and then redissolve during the next steps [71]. Siregar et al. [72] performed an experiment to verify the effect of hypochlorite on inorganic compounds at a pH value of 8 in different soils. They concluded that the hypochlorite dissolved between 12 and 72% of the organic matter, with low release of Fe (<0.03 μg/g), even if a soil (chromic cambisol type) showed significant changes in the specific surface area, interpreted by the authors as a release of Fe from amorphous iron oxide aggregates (e.g., ferrihydrite). Similar results (changes in the surfaces of the minerals) have been reported by others when leaching soils with NaOCl at pH 9.5 [73]. According to Marzadori et al. [74], treatment with NaOCl (7%, pH 9.5, T= 80 °C) not only dissolves organic materials but also poorly crystalline Fe-oxides. The procedure used by Marzadori is close to those used in this work.

It is known that ferrate, FeO4 2−/Fe(OH)3, can be produced by heating an Fe(III)-hydroxide with NaOCl in alkaline solution [75]. In an alkaline environment, the oxidation/reduction potential, ORP, of the couple ClO−/Cl− is 0.84 V/SHE (standard hydrogen electrode), while the couple Fe(VI)O4 2−/Fe(OH)3 has an ORP in an alkaline solution of 0.70 V/SHE. In the same conditions, the couple MnO4−/MnO2 has a potential of 0.59 V/SHE, and the couple CrO42−/Cr(OH)3 of −0.12 V/SHE [76]. Therefore, in these conditions, non-crystalline Fe/Mn-hydroxides can be oxidized to ferrate and permanganate. Ferrihydrite (5Fe2O3·9H2O) is quite common in soils and sediments and is formed by precipitation of Fe by enriched aqueous solutions and/or by bacterial activity [77]. In serpentine soils the ferrihydrite can contain up to 1.13% of Cr and 1.29% of Ni [78]. The oxidation of non-crystalline Fe-hydroxides and oxides rich in Cr and Mn in the presence of hypochlorite at pH 9.5 and a temperature of 90 °C may explain the quantity of Fe, Ni, and Cr extracted during the F3 step of this work. Amorphous Mn-oxides, however, can be oxidized under the Eh conditions of this system. Langone et al. [57] suggested the presence of Fe-bearing layered double hydroxides (Fe-LDHs) in soil samples located in Querceto. Such minerals may also contain Ni and Cr and be subject to oxidative processes at the values of Eh during the F3 step.

The sedimentary samples (PG5, PG6) did not exhibit statistically significant differences to the serpentinite samples after SSE, even if Cr and Ni had slightly lower values. In particular, the highest content of metals (Cr, Ni, Fe, and Mn) was released during the F6 and F7 step, when Fe/Mn oxides were dissolved. Hence, in all samples the Cr and Ni were mainly associated with crystalline Fe-Mn oxides but show comparable release also in less forceful step. The possibility that a part of these metals could be leached partially by chromite during the F7 step cannot be excluded. It has to be noted [58] that the springwaters in Querceto and Montecastelli showed total average Cr concentration of about 50 and 20 μg/L (mostly as Cr (VI)). Most authors [18,24] maintain that occurrence of soluble Cr in groundwater suggests that naturally occurring Cr (III) in soils is undergoing oxidation to Cr(VI). In agreement with Morrison et al. [18], the higher Cr availability in the soils of Querceto (QU2, QU1A, and QU1C) and Montecastelli (SDS1) indicates an increase in the mobility of Cr that is present in the non-crystalline Fe-hydroxides.

The redox potential during the extraction of NaOCl was about 1200 mV, above the redox potential for water dissociation. Hence, in the natural system the oxidation of Cr (III) to Cr (VI) plays a different role. However, the extraction with NaOCl underlined that the presence of an oxidizing agent is not enough to release significant Cr (VI) into the water, but it needs the presence of Cr in the non-crystalline Fe-hydroxides. In the natural environment, a potential oxidizing agent is Mn-oxide. The sedimentary samples from the Cecina coastal plain released Cr in amounts proportional to their total Cr content, suggesting a possible relationship with the occurrence of Cr(VI) in the coastal aquifer. On the basis of Cr and Ni in the mobile fraction, all samples appear to present a similar hazard for leaching of chromium and nickel. This is despite the very different early concentrations in the total samples.

The predominance of Cr in the residual fractions observed in our samples aligns with findings reported by Shi et al. [14], while the Ni mobility under dynamic redox conditions confirms trends highlighted by Shaheen et al.

5. Conclusions

This work underlines that serpentine soils and derived sediments from coastal Tuscany, far from anthropogenic pollution, show high concentrations of Cr and Ni. The mobility of these metals is related to their association with mineral phases that are easily weathered in the environment. In particular, the Fe/Mn hydroxides produced by the weathering of serpentinites could be enriched in Cr and Ni that could be released into the environment by a weakly acid solution or a system with high redox potential. An ORP higher than 1000 mV could lead to the formation of Cr (VI) by oxidation of Cr (III), in this way increasing the mobility of Cr in groundwater and the hazard for human health. Samples with aqua regia-extractable Cr > 120 μg/g and Ni > 150 μg/g (Italian soil quality standards) are considered high-risk for groundwater contamination.

The use of a solution of NaOCl at a pH of 9.5 allows for the differentiation of samples because of the ability to release Cr and Ni. Consequently, a test and a protocol using this solution could be proposed to the authorities (e.g., environmental protection agency, national and regional governments) to identify the potential risk of release of Cr (VI) in groundwater from serpentine soils.

This study contributes to the growing body of research on chromium and nickel behavior in ultramafic systems, reinforcing the need for targeted strategies to manage Cr(VI) risks [12,16]. Our results underscore the stability of Cr in residual phases and the relative mobility of Ni, highlighting the importance of site-specific assessments. Future work should explore the application of biostimulation techniques and advanced remediation technologies to complement conventional monitoring. These integrated approaches could significantly reduce environmental hazards associated with ultramafic-derived soils and sediments.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adriano, D.C. Trace Elements in the Terrestrial Environment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Pendias, H. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Testa, M.S. Overwiev of Cr (VI) in the environment: Background and history. In Chromium Handbook; Guertin, J., Jacobs, J.A., Avakian, C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 23–92. [Google Scholar]

- Caritat, P.; de Reimann, C.; NGSA Project Team; GEMAS Project Team. Comparing results from two continental geochemical surveys to world soil composition and deriving Predicted Empirical Global Soil (PEGS2) reference values. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 319–320, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, H.L. The Use of Plant Indicators in Groundwater Geochemical Exploration; USGS Bulletin 1457-A; U.S. Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; 35p. [Google Scholar]

- Oze, C.; Fendorf, S.; Bird, D.K.; Coleman, R.G. Chromium geochemistry of serpentine soils. Int. Geol. Rev. 2004, 46, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hseu, Z.Y.; Tsai, H.; His, H.C.; Chen, Y.C. Weathering sequences of clay minerals in soils along a serpentinitic toposequence. Clays Clay Miner. 2007, 55, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierczak, J.; Neel, C.; Bril, H.; Puziewicz, J. Effect of mineralogy and pedoclimatic variations on Ni and Cr distribution in serpentine soils under temperate climate. Geoderma 2007, 142, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandeur, D.; Juillot, F.; Morin, G.; Olivi, L.; Cognigni, A.; Webb, S.M.; Ambrosi, J.-P.; Fritsch, E.; Guyot, F.; Brown, G.E., Jr. XANES evidence for exidation of Cr(III) to Cr(VI) by Mn-oxides in a lateritic regolith developed on serpentinized ultramafic rocks of New Caledonia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 7384–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Jien, S.H.; Iizuka, Y.; Tsai, H.; Chang, Y.H.; Hseu, Z.Y. Pedogenic chromium and nickel partitioning in serpentine soils along a toposequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelepertzis, E.; Galanos, E.; Mitsis, I. Origin, mineral speciation and geochemical baseline mapping of Ni and Cr in agricultural topsoils of Thiva valley (central Greece). J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 150, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, A.; Mamais, D.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Anastopoulou, P.; Varouxaki, A. Biotic and abiotic biostimulation for the reduction of hexavalent chromium in contaminated aquifers. Water 2022, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, E.; Papazotos, P.; Dimitrakopoulos, D.; Perraki, M. Hydrogeochemical processes and natural background levels of chromium in an ultramafic environment: The case study of Vermio Mountain, Western Macedonia, Greece. Water 2021, 13, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Wang, J. Distribution characteristics of high-background elements and assessment of ecological element activity in typical profiles of ultramafic rock area. Toxics 2025, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, A.; Sadowski, Z.; Winiarska, K. Chemical and bioreductive leaching of laterites and serpentinite waste with possible reuse of solid residues for CO2 adsorption. Minerals 2025, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrzynska, K. Nanomaterials for removal and speciation of chromium. Materials 2025, 18, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, S.C. Acute and chronic systemic chromium toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 1989, 86, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.M.; Goldhaber, M.B.; Lee, L.; Holloway, J.M.; Wanty, R.B.; Wolf, R.E.; Ranville, J.F. A regional-scale study of chromium and nickel in soils of northern California, USA. Appl. Geochem. 2009, 24, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.T.; Morrison, J.M.; Goldhaber, M.B.; Ellefsen, K.J. Chromium(VI) generation in vadose zone soils and alluvial sediments of the southwestern Sacramento Valley, California: A potential source of geogenic Cr(VI) to groundwater. Appl. Geochem. 2011, 26, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, F.N. Geochemistry of Ground Water in Alluvial Basins of Arizona and Adjacent Parts of Nevada, New Mexico, and California; U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1406-C; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Camacho, J.; Armienta, M.A. Natural chromium contamination of groundwater at Leon Valley, Mexico. J. Geochem. Explor. 2000, 68, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantoni, D.; Brozzo, G.; Canepa, M.; Cipolli, F.; Marini, L.; Ottonello, G.; Vetuschi Zuccolini, M. Natural hexavalent chromium in groundwaters interacting with ophiolitic rocks. Environ. Geol. 2002, 42, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.J. Naturally occurring Cr(VI) in shallow groundwaters of the Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2003, 3, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.; Izbicki, J.A. Occurrence of hexavalent chromium in ground water in the western Mojave Desert, California. Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.R.; Ndung’u, K.; Flegal, A.R. Natural occurrence of hexavalent chromium in the Aromas Red Sands Aquifer, California. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 5505–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izbicki, J.A.; Ball, J.W.; Bullen, T.D.; Sultley, S.J. Chromium, chromium isotopes and selected trace elements, western Mojave Desert, USA. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 1325–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, C.; Webb, S.; Fendorf, S. Natural chromium(VI) generation in ultramafic soils: A field and laboratory assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- McClain, C.N.; Fendorf, S.; Johnson, S.T.; Menendez, A.; Maher, K. Lithologic and redox controls on hexavalent chromium in vadose zone sediments of California’s Central Valley. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019, 265, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.H.; Lehmann, N.; Jackson, T.; Holm, P.E. Cadmium and nickel distribution coefficients for sandy aquifer materials. J. Contam. Hydrol. 1996, 24, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookins, D.G. Eh-pH Diagrams for Geochemistry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Pacifico, R.; Adamo, P.; Cremisini, C.; Spaziani, F.; Ferrara, L. A geochemical analytical approach for the evaluation of heavy metal distribution in lagoon sediments. J. Soils Sediments 2007, 7, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.M.; Montero, M.A.; Pina, S.; Garcia-Sanchez, E. Mineralogy and distribution of Cd, Ni, Cr, an Pb in amended soils from Castellon Province (NE, Spain). Soil Sci. 2009, 174, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytak, S.; Turker, R.A. Determination of lead and nickel in environmental samples by flame atomic absorption spectrometry after column solid-phase extraction on ambersorb-572 with EDTA. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 129, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cempel, M.; Nikel, G. Nickel: A Review of its sources and environmental toxicology. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2006, 15, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, L.M.; Frederick, R.R. Soils and Fertility; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA; Ed. Reverte: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Mukherjee, A.B. Trace Elements from Soil to Human; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; p. 867. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, S.M.; Henriques, B.; Ferreira da Silva, E.; Pereira, M.E.; Duarte, A.C.; Romkens, P.F.A.M. Evaluation of an approach for the characterization of reactive and available pools of twenty potentially toxic elements in soils: Part I—The role of key soil properties in the variation of contaminants’ reactivity. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yu, S.; Li, X. The mobility, bioavailability and human bioaccessibility of trace metals in urban soils of Hong Kong. Appl. Geochem. 2012, 27, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.C.; Tsai, L.J.; Chen, S.H.; Ho, S.T. Correlation analyses on binding behaviour of heavy metals with sediment matrices. Water Res. 2001, 35, 2417–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, S.K.; Banerjee, D.K. Speciation of metals in sewage sludge and sludge amended soils. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2004, 152, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, J.; Quantin, C.; Guimaraes, E.; Garg, V.K.; Martins, E.S. Understanding the genesis of ultramafic soils and catena dynamics in Niquelandia, Brazil. Geoderma 2009, 151, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, M.T.; Delgado, J.; Albanese, S.; Nieto, J.M.; Lima, A.; De Vivo, B. Heavy metals fractionation and multivariate statistical techniques to evaluate the environmental risk in soils of Huelva Township (SW Iberian Peninsula). J. Geochem. Explor. 2012, 119–120, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng-Ping, H.; Zeng-Yei, H.; Yoshiyuki, I.; Shih-Hao, J. Chromium Speciation Associated with Iron and Manganese Oxides in Serpentine Mine Tailings. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2013, 30, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios, R.; Fernandez-Martinez, R.; Rucandio, M. Chemical speciation of trace metals in soils and sediments: A critical assessment. Appl. Geochem. 2013, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gleyzes, C.; Tellier, S.; Astruc, M. Fractionation studies of trace elements in contaminated soils and sediments: A review of sequential extraction procedures. Trends Anal. Chem. 2002, 21, 6–7, 451-467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramel, O.; Michalke, B.; Kettrup, B. Study of the copper distribution in contaminated soils of hop fields by single and sequential extraction procedures. Sci. Total Environ. 2000, 263, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśniewska, B.; Gontarska, M.; Godlewsk, B. Selective Separation of Chromium Species from Soils by Single-Step Extraction Methods: A Critical Appraisal. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, A.V.; Lavilla, I.; Bendicho, C. Chemical sequential extraction for metal partitioning in environmental solid samples. J. Environ. Monit. 2002, 4, 823–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, F.M.; Verloo, M.G. Chemical Speciation and Fractionation in Soil and Sediment Heavy Metal Analysis: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1995, 59, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Campbell, P.G.; Bisson, M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal. Chem. 1979, 51, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.J.; Farmer, J.G. Multi-step sequential chemical extraction of heavy metals from urban soils. Env. Pollut. Ser. B Chem. Phys. 1986, 11, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dold, B. Speciation of the most soluble phases in a sequential extraction procedure adapted for geochemical studies of copper sulfide mine waste. J. Geochem. Explor. 2003, 80, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Force, M.J.; Fendorf, S. Solid-Phase Iron Characterization During Common Selective Sequential Extractions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becquer, T.; Quantin, C.; Sciot, M.; Boudot, J.P. Chromium availability in ultramafic soils from New Caledonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 301, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laterza, V.; Franceschini, F. Influence of ophiolitic rocks on the spatial distribution of chromium and nickel in stream sediments of the Cecina river basin (Tuscany, Italy). Ofioliti 2013, 38, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, S. Origine del Cromo Esavalente in Val di Cecina e Valutazione Integrata degli Effetti Ambientali e Sanitari Indotti dalla Sua Presenza—Rapporto Conclusivo della Prima Fase del Progetto IGG-CNR, ISE-CNR, ARPAT; Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione Ambientale della Toscana: Florence, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Langone, A.; Baneschi, I.; Boschi, C.; Dini, A.; Guidi, M.; Cavallo, A. Serpentinite-water interaction and chromium (VI) release in spring waters: Examples from Tuscan Ophiolites. Ofioliti 2013, 38, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lelli, M.; Grassi, S.; Amadori, M.; Franceschini, F. Natural Cr(VI) contamination of groundwater in the Cecina coastal area and its inner sectors (Tuscany, Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 3907–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, M.; Li, L.; Feng, K. Feasibility exploration of the efficient recovery of chromium from a lateritic nickel deposit. Minerals 2025, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirta, G.; Pandeli, E.; Principi, G.; Bertini, G.; Cipriani, N. The Ligurian units of Southern Tuscany. In Results of the CROP18 Project, Special Volume, Bollettino Societa Geologica Italiana; Societa Geologica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoletti, E.; Mazzanti, R.; Squarci, P. Idrogeologia del territorio del Comune di Rosignano Marittimo. In La Scienza della Terra: Nuovo Strumento per la Lettura e Pianificazione del Territorio di Rosignano Marittimo; Quaderni del Museo di Storia Naturale di Livorno 6; Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Provincia di Livorno e Comune di Rosignano Marittimo: Livorno, Italy, 1985; pp. 247–283. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Antonia, B.; Bossio, A.; Mazzanti, R. The Lower-Middle Pleistocene succession of the Coastal Tuscany (Central Italy): New stratigraphic and palaeoecological data based on the ostracod fauna. Rev. Micropaléontologie 2005, 48, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, Soils, and Oils. In Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste, Physical/Chemical Methods, 3rd ed.; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandroni, V.; Smith, C.M.M.; Donovan, A. Microwave digestion of sediment, soil and urban particulate matter for trace metal analysis. Talanta 2003, 60, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; APHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Method 3120. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini, M.; Leoni, L.; Saitta, M. Enhancement effects in X-ray fluorescence analysis of rocks. X-Ray Spectrom. 1976, 5, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, F.; Biasioli, M.; Ajmone Marsan, F. Metals in urban soils of large European cities. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 152, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A.L.; Anderson, K.A. DGT estimates of bioavailable Ni and Cu in freshwaters. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 622, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacio, E.; Falsone, G.; Piazza, S. Linking Ni and Cr concentrations to soil mineralogy: Does it help to assess metal contamination when the natural background is high? J. Soils Sediments 2010, 10, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.L.; Chen, S.-B.; Lin, C.-F. Adsorption behavior of chromium and nickel on iron oxyhydroxides in serpentine soils. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, T.; Xiao-quan, S.; Zhe-ming, N. Evaluation of a sequential extraction procedure for the fractionaction of amorphous iron and manganese oxides and organic matter in soils. Sci. Total Environ. 1994, 151, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, A.; Kleber, M.; Mikutta, R.; Jahn, R. Sodium hypochlorite oxidation reduces soil organic matter concentrations without affecting inorganic soil constituents. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2005, 56, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L.M. Extent of coverage of mineral surfaces by organic matter in marine sediments. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzadori, C.; Antisari, L.V.; Ciavatta, C.; Sequi, P. Soil organic matter influences on adsorption and desorption of boron. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1991, 55, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulfsberg, G. Principles of Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 1991; p. 453. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V. Oxidation of inorganic contaminants by ferrates (VI, V, and IV)-kinetics and mechanisms: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, D.; Langley, S. Formation and occurrence of biogenic iron-rich minerals. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2005, 72, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, W.; Hunerlach, M.P.; Hering, J.G. Distribution of trace metals in ferrihydrite-rich soils developed on ultramafic rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 104, 26–45. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.