Abstract

Background: Digital technologies are increasingly integrated into circular supply chains (CSCs) to enhance resource efficiency and extend product lifecycles. However, the practical adoption of intelligent circular supply chains (iCSCs) remains underexplored. Methods: This study provides a comprehensive review of how digital technologies enable circular practices across industries. It systematically reviews 95 peer-reviewed articles from WoS and Scopus, identifying 107 real-world iCSC cases. The cases are categorized by (1) digital enablers including AI, Big Data, Blockchain, IoT, Digital Twin, Additive Manufacturing, Cloud Platforms, and Cyber-Physical Systems; (2) alignment with Circular Economy (CE); (3) sector-specific circular practices; and (4) mapping implementations to the EU Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP). This study develops a conceptual model illustrating how digital technologies support data-driven decision-making, automation, and circular transitions. Results: The analysis shows IoT, Blockchain, and AI as the most frequently applied technologies, facilitating collaboration, traceability, sustainability, and cost efficiency. “Reduce” and “Recycle” dominate among CE strategies, while circular transition pathways such as sustainable design, waste prevention, and digital platforms link policy to practice. Conclusions: By integrating systematic evidence with a holistic framework, this work provides actionable insights, identifies key implementation gaps, and lays a foundation for advancing iCSCs in research and practice.

1. Introduction

The focus on reducing CO2 emissions and minimizing the environmental impact of manufacturing has received considerable attention in both academic research and industrial practices. This emphasis has been reinforced by a number of initiatives, such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [1], which explores new approaches to support the Circular Economy (CE). Furthermore, the European Union (EU) Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) [2], a cornerstone of the European Green Deal [3], highlights the growing attention of governments at both strategic and operational levels toward the CE.

Resource limitations, increasing energy consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions in manufacturing have intensified the focus on circular supply chains (CSCs) as key enablers of the CE [4]. According to the CE gap report [5], the global economy remains heavily reliant on virgin material extraction, while the share of recycled secondary materials has declined to just 6.9%. This trend is largely driven by the accelerating pace of global material throughput, which surpasses the rate at which secondary materials are recovered and reintegrated into production systems. In response to these pressures, CSCs have gained significant attention for their ability to retain value, regenerate resources, and minimize waste across the entire product lifecycle by enabling circular strategies such as reduce, remanufacture, repair, and reuse. CSCs combine CE with supply chain processes, representing a natural evolution beyond traditional closed-loop supply chains (CLSCs) [6]. While CLSCs primarily emphasize waste recovery, sustainable supply chain management offers an even broader perspective by integrating economic, environmental, and social objectives across all supply chain activities [6].

Real-world evidence further illustrates the urgency of strengthening CSCs. As highlighted in the CEAP [2], the electronics sector remains a critical priority, with less than 40% of end-of-life devices currently recycled in the EU and substantial value lost due to limited reparability, non-replaceable components, unsupported software, and challenges in recovering embedded materials. Similar systemic barriers are evident in the construction sector, which accounts for approximately 50% of global material extraction, over 35% of total waste generated in the EU, and between 5% and 12% of national greenhouse gas emissions. Although improvements in material efficiency could mitigate up to 80% of these emissions, realizing this potential requires greater visibility and coordination across supply chain actors.

Within this expanding landscape, exploring the role of digital technologies in CE strategies, particularly within CSCs, has become a prominent topic [7]. The necessity for such integration is especially pronounced across key value chains, including electronics and Information and Communication Technology (ICT), textiles, packaging, construction, and food systems, where digital tools can support the tracking, tracing, and mapping of material flows needed to operationalize circularity at scale. In this context, Industry 4.0 (I4.0) technologies have emerged as a key enabler of digitalization within CSCs, supporting the development of intelligent Circular Supply Chains (iCSCs) and the broader implementation of CE [8]. Companies are increasingly using these technologies to stay competitive and meet their sustainability objectives [9]. Their applications span a wide range of functions, including sustainable resource allocation and efficiency [10], consumption monitoring [11], production scheduling [12], customer service and maintenance operations [13], quality management [14], and reverse logistics [15,16]. Several reviews [17,18,19] discussed the strategic impact of digital technologies on CE and supply chain operations. While some studies address business models and implementation barriers [20], the practical application of digital tools in real-world CSCs remains underexplored. Despite the growing body of literature on digital integration in CSCs, there is a clear lack of insight into how these technologies are actually being implemented on the ground. Moreover, there is limited understanding of how such implementations align strategic actionable plans for circularity.

Our study addresses this theorical gap by developing an integrative conceptual framework that explains how digital technologies enable CE strategies across CSCs. While prior studies have largely examined individual digital applications in isolation, a coherent theoretical understanding of how digital technologies interact with CE principles and implementation pathways remains underdeveloped. To advance theory, this study conceptualizes digital-enabled circularity across multiple dimensions based on CEAP, including sustainable product design, circular production processes, waste prevention and resource efficiency, digital and data-driven platforms, and circularity beyond production at the city and regional levels. It further theorizes how these dimensions are operationalized within key value chains and how they lead to distinct circular outcomes. In addition, this study systematically extracts and categorizes more than 70 distinct implementation outcomes per technology. In doing so, the study contributes to the literature by synthesizing implementation evidence. To summarize, the main contributions of this research are as follows:

- Presents a comprehensive review of digital technology applications within CSCs, including methodologies, outcomes, and industry-specific cases.

- Maps technological implementations to the 10R CE strategies, strengthening the link between technology and theoretical sustainability frameworks.

- Aligns technological solutions with the EU CEAP, translating concepts into actionable policy-oriented insights.

- Develops a holistic model that demonstrates the relationships between digital enablers, CE strategies, transition pathways, and outcomes, clarifying how technologies drive circularity.

- Identifies gaps and suggests future research directions for advancing intelligent CSC adoption.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background of the study. Section 3 outlines the research design and methodology. Section 4 presents the descriptive and content analysis results. Section 5 introduces the conceptual model. Section 6 discusses the findings, identifies research gaps, and offers recommendations for future studies. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper with key insights.

2. Background

The transition toward the CE has stimulated extensive research across the domains of supply chain management and digital technologies. However, the existing body of literature exhibits considerable variation in terms of research focus, analytical scope, and methodological approaches. To position the present study within this evolving research landscape, this section critically reviews the most relevant scholarly contributions and synthesizes the key themes emerging from prior work. Table 1 provides a detailed overview of existing reviews on the role of digital technologies in CE, with a focus on their applications at the supply stage.

Table 1.

An overview of recently published literature reviews in the domain of iCSC.

An analysis of the studies summarized in Table 1 indicates that most existing reviews focus narrowly on specific technologies or particular industry sector. For instance, reference [23] assessed big data (BD) and fuzzy techniques, while reference [32] explored IoT solutions in CSCs. The authors of [28] emphasized the role of BD and AI in enhancing SC efficiency, and reference [22] examined the use of machine learning (ML) across CSC stages.

On the other side, scholars also see the topic through an industry-specific lens. Reference [26] focused on the construction sector, [33] analyzed green building materials supply chains, [34,35] on the food sector, [36] on textile, and [29] on electrical and electronic equipment. Other reviews addressed particular challenges; for example, reference [30] analyzed the role of digital technologies in fostering collaboration, and [24] highlighted their application in supply chain quality management.

Despite these valuable contributions, existing reviews predominantly remain conceptual or technology-centric, offering limited insight into how digital technologies are practically implemented within real-world CSCs. Accordingly, this study addresses this gap by adopting a practice-oriented perspective, examining how digital technologies are deployed in operational contexts and how such implementations support the translation of CE strategies into actionable supply chain practices.

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Questions (RQs)

With the emergence of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s CE model, a growing body of research has explored the role of technologies within CSCs, addressing a range of objectives. Among these, a subset of studies has focused on the practical dimensions of implementation and the evaluation of outcomes. Building on this foundation, the present paper seeks to address the following RQs within the context of iCSCs:

- RQ1—How have digital technologies been applied in real-world implementations, including detailed methods and objectives of implementation? (Addressed in Section 4.2.1)

- RQ2—Which CE strategies have been prioritized in the practical applications of digital technologies? (Addressed in Section 4.2.2)

- RQ3—What are the main sectors adopting digital technologies in CSCs? (Addressed in Section 4.2.3)

- RQ4—How can implementations of digital technologies in CSCs be mapped to the EU CEAP to assess alignment with policy-driven transition pathways? (Addressed in Section 4.2.4)

- RQ5—What conceptual relationships exist between digital enablers, CE strategies, transition pathways, and resulting outcomes in iCSCs? (Addressed in Section 5)

- RQ6—What are the primary research gaps in the current literature, and what opportunities are suggested for future research? (Addressed in Section 6)

3.2. Research Methodology and Boundaries

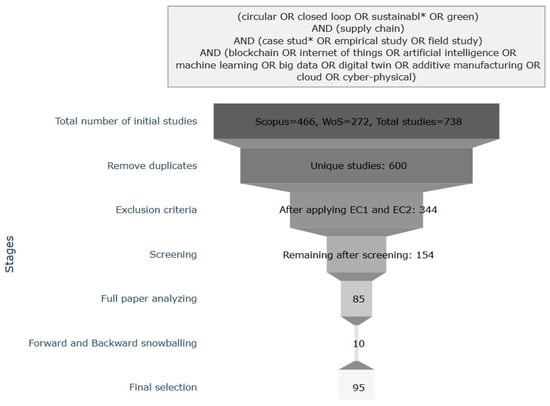

Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases were selected to identify articles related to iCSCs. The search criteria were designed based on four dimensions: (1) circularity, (2) supply chain, (3) I4.0 technologies, and (4) practical aspects. Table 2 outlines these dimensions in detail. To refine the search, filters were constructed by combining terms from each aspect, ensuring comprehensive coverage of relevant literature (see Figure 1).

Table 2.

Main filter search categories.

Figure 1.

Article selection process. The search query includes * to capture variations of keywords (e.g., “sustainabl*” retrieves “sustainable,” “sustainability,” etc.).

The initial search identified 738 articles published up to January 2025. After removing duplicate articles, the count was reduced to 600. The first exclusion criterion (EC1), restricting the language to English, brought the total down to 598 articles. Subsequently, the second exclusion criterion (EC2), which selected only journal articles (excluding conference papers and other study types), narrowed the count to 344 articles.

During the screening phase, papers were assessed according to the relevance of their titles, abstracts, and keywords, focusing specifically on implementation aspects (EC3). This resulted in 154 articles. Following a full review of these articles, a final set of 85 was selected based on the criterion that each paper explicitly addressed the implementation of at least one digital technology within the context of circularity in SC and production systems.

In the snowballing phase, inclusion criterion 1 (IC1), which included forward and backward citation analysis, added 10 articles by identifying related studies through references and citations from the initially selected articles. This process brought the final database to 95 articles.

4. Descriptive and Content Analysis

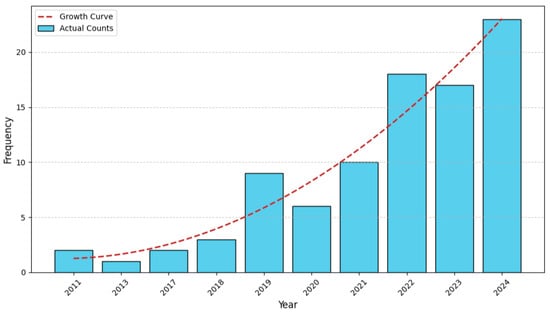

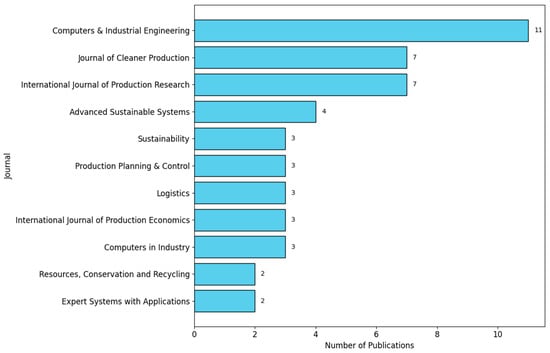

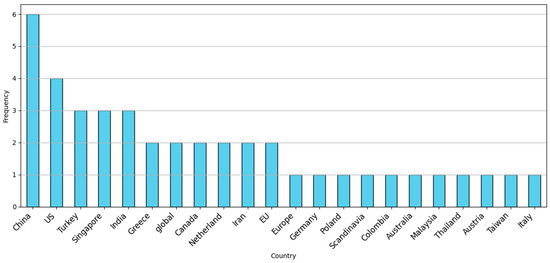

In this section, both descriptive and content analyses are presented. The descriptive analysis covers the number of publications by year (Figure 2), the geographical distribution of the implementation studies (Figure 3), and the journals in which the reviewed articles were published (Figure 4). The content analysis section delves into the details of each digital technology implementation and its corresponding outcomes within the context of CE.

Figure 2.

Number of publications by year.

Figure 3.

Distribution of reviewed articles by journal.

Figure 4.

Distribution of articles by country of implementation.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

As illustrated in Figure 2, the number of articles published in the context of iCSC with a practical perspective has doubled over the past five years. This suggests an emerging focus on the role of technologies within iCSC, shifting towards industry implementation rather than theoretical models.

The articles have been distributed across 44 journals. As shown in Figure 3, the top journals are Computers & Industrial Engineering with 11 articles, Journal of Cleaner Production and International Journal of Production Research with 7 articles, and Advanced Sustainable Systems with 4 articles.

Figure 4 depicts the geographical distribution of the implemented solutions, which differ from the authors’ countries. China, the US, Singapore, Turkey, and India collectively account for approximately 50% of the implemented solutions.

4.2. Content Analysis

This section examines the 95 papers, organized according to the research questions. Section 4.2.1 addresses RQ1 by investigating the application of digital technologies within CSC. Section 4.2.2 analyzes the papers from the CE perspective and answers RQ2. Section 4.2.3 examines the context of the studies within specific sectors, answering RQ3. Finally, Suection 4.2.4 extracts and categorizes the CEAP criteria and maps them to the papers, answering RQ4.

4.2.1. Digital Technologies Adoption in CSC

The applications of digital technologies in the context of CE were systematically categorized into six thematic areas: (1) product monitoring and lifecycle management, (2) logistics optimization, (3) resource efficiency, (4) environmental monitoring, (5) operational efficiency and automation, and (6) strategic analysis and decision support platforms. The classification was based on the primary functional objective of each digital application within the CSC, rather than on the specific technology itself. In particular, product monitoring and lifecycle management were grouped under a single theme, as both focus on enabling continuous visibility, traceability, and data integration across multiple product lifecycle stages, including use, maintenance, recovery, and end-of-life management. From a CE perspective, these functions collectively support lifecycle-oriented decision-making and closed-loop strategies.

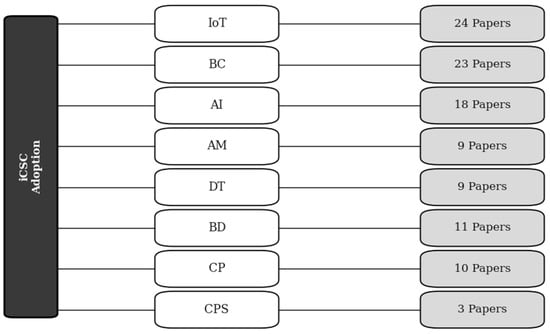

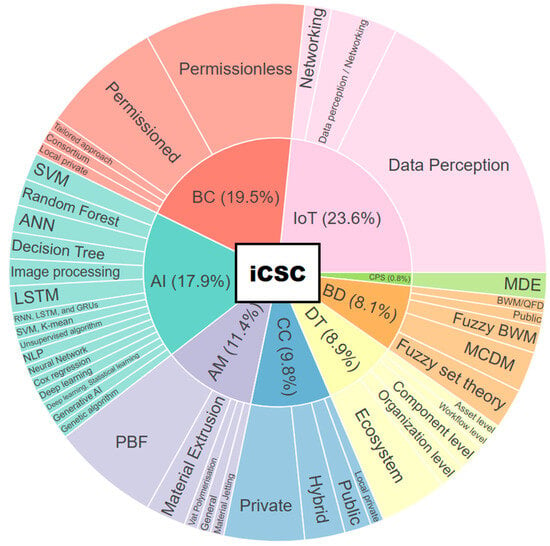

The thematic categories emerged through a structured review process, informed by both the frequency of occurrence in the literature and their conceptual alignment with core CE principles. In cases where an article addressed multiple themes, it was assigned to the category that best reflected its dominant contribution, while secondary themes were acknowledged during the synthesis. Figure 5 illustrates the range of technologies discussed in the papers. Since some articles cover multiple technologies, the total number of technologies examined (107) exceeds the total number of articles (95). Within each technology-focused subsection, the reviewed articles are organized according to the identified thematic categories, and their findings are synthesized to reflect the specific contributions and insights aligned with each theme.

Figure 5.

Distribution of articles by digital technology.

- I.

- Internet of Things (IoT)

IoT can be defined as a network that interconnects humans, computers, and physical objects. It leverages technologies such as RFID, infrared sensors, GPS, and other information-sensing devices to connect items using Internet Protocol (IP). This connectivity facilitates information exchange and connection, thereby enabling intelligent positioning, tracking, monitoring, and management of the connected items.

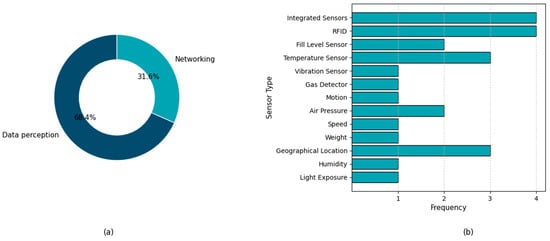

IoT has emerged as a crucial tool in driving sustainable solutions across a wide range of industrial sectors [37]. The continuous data streams generated by IoT devices can be leveraged to facilitate circular resource management, refine value propositions, and improve decision-making efficiency. Research on IoT applications in CSCs can be analytically structured into two interconnected layers: the data perception layer and the networking (communication) layer. The majority of the reviewed studies (68.4%) emphasize the data perception layer, highlighting the central role of sensing technologies in enabling real-time visibility of materials, products, and processes across CSCs. In contrast, 31.6% of the studies focus on networking and data transmission capabilities.

A closer examination of the sensing technologies reported in the literature reveals a strong concentration on integrated sensors and RFID technologies, which are the most frequently cited. Geographical location sensors (e.g., GPS) and temperature sensors also appear prominently, particularly in applications related to logistics optimization, monitoring, and waste reduction in food and pharmaceutical supply chains. Other sensing technologies, such as air pressure, vibration, motion, gas detection, humidity, and light exposure sensors; are less frequently discussed but play a critical role in more specialized circular applications. These sensors enable condition monitoring and predictive maintenance [38], thereby supporting resource efficiency, waste prevention, and extended product lifecycles.

Table 3 presents the applications of IoT across key themes, while Table A1 and Figure A1 in the Appendix A provide detailed examples of IoT applications and the distribution of studies across these layers in CSC.

- II.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI can strengthen CSCs through improved resource management, process optimization, and the mitigation of systemic complexities. By providing data-driven insights, ML can serve as a valuable tool to enhance decision-making and support the overall operations of CSCs [22]. By analyzing large volumes of real-time and historical data, AI supports predictive, prescriptive, and optimization-based decisions across both forward and reverse supply chain processes. In CSC contexts, AI applications include improving product sorting, disassembly, component reproduction, and recycling, as well as optimizing reverse logistics, increasing product turnover, and enabling intelligent inventory management through price and demand forecasting based on real-time and historical data. Furthermore, ML supports sustainable product design and development by enabling data-driven material selection, modular design, and waste management strategies [39,40].

According to the reviewed literature, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and deep learning models have been widely applied to complex tasks, such as cost structure estimation [41,42] and supply chain network optimization [43,44]. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), are particularly effective in forecasting energy production and demand in decentralized and renewable energy systems [45], thereby supporting circular energy management and enhancing resource efficiency.

In logistics and operations, support vector machines (SVMs) [46], decision trees [47], random forests [48], and logistic regression models [46] have been applied to inventory management, warehouse operations, and predictive maintenance, enabling waste reduction, extended asset lifecycles, and improved material utilization. Image processing and computer vision techniques support intelligent waste identification, sorting, and monitoring, reducing energy consumption and operational costs in recycling and waste management systems [49]. At a higher decision-support level, natural language processing (NLP) improves risk assessment and decision accuracy by extracting insights from unstructured data [50], while generative AI enhances operational efficiency [51] through scenario generation and adaptive planning. Collectively, these AI techniques enable CSCs to transition from static, rule-based systems toward adaptive, data-driven, and self-optimizing supply chain configurations, reinforcing CE objectives such as waste prevention, resource efficiency, and value retention.

Table 4 presents the applications of AI across key themes, while Table A2 in the Appendix A provides detailed examples of AI applications in CSC.

- III.

- Blockchain (BC)

BC and smart contracts offer effective solutions to key challenges in the CSC, such as counterfeiting, data security and privacy, high operating costs, and bureaucratic obstacles [52]. By ensuring data transparency in stakeholder communications and enabling the tracking of products throughout their entire lifecycle, BC enhances reliability across various stages of the CSC. This includes critical processes like inventory management, product transfers, and delivery among different actors.

BC networks are generally categorized into public (or permissionless), private (or permissioned), federated, and hybrid. Public BCs, such as the Bitcoin network, are open to anyone with internet access, allowing anyone to join and perform transactions. In contrast, private BCs, often used in business applications like SCs, require permission to join and carry out transactions. These private networks are typically composed of known participants who share a certain level of trust with one another [53]. Moreover, BC-based CSC implementations facilitate decentralized decision-making [54,55,56,57], automated execution through smart contracts [58], and secure information sharing across permissioned and permissionless networks [59]. Such features improve resource utilization [10], reduce energy consumption [60], and support closed-loop activities such as recycling, remanufacturing, and sustainable procurement [61]. Collectively, BC and smart contracts enable CSCs to move beyond linear, siloed systems toward resilient, data-driven, and collaborative ecosystems. Table 5 presents the applications of BC across key themes. Table A3 in the Appendix A shows the details of them.

Table 3.

Classification of IoT applications into key themes.

Table 3.

Classification of IoT applications into key themes.

| Theme | Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| T1. Product Monitoring & Lifecycle Management | Product lifecycle & degradation [62,63] | R1. Increased profitability through waste reduction |

| Predictive maintenance (health monitoring) [48] | R2. Prevented breakdowns, failure prediction and extended product life | |

| T2. Logistics Optimization | Production-delivery model integration [64] | R3. Improved production scheduling |

| Supply chain location analysis [43] | R4. Supported network design | |

| product status tracking [65,66] | R5. Improved distribution efficiency | |

| Reverse logistics tracking [61] | R6. Enhanced product recovery and recycling efficiency | |

| T3. Resource Efficiency | Soil nutrients, temperature, humidity, pH [67] | R7. Optimized agricultural yield, reduced fertilizer and water use |

| Energy and water consumption [11] | R8. Minimized resource use, supports CE “Reduce” strategy | |

| Maximize resources occupancy rates [10] | R9. Optimized trip numbers, minimized costs and greenhouse gas emissions | |

| T4. Environmental Monitoring | Air quality control [68] | R10. Improved workplace & urban circularity |

| T5. Operational Efficiency & Automation | Assembly/disassembly operations [69,70,71] | R11. Improved efficiency in component reuse and remanufacturing |

| Inventory management [72] | R12. Eliminated bottlenecks, automates refills | |

| Automation and improve efficiency [58] | R13. Automated notifications when measurements exceed thresholds and workflow optimization | |

| T6. Strategic Analysis & Decision Support Platforms | Input of decision support systems [73,74] | R14. Enhanced data-driven decision-making for CE strategies |

Table 4.

Classification of AI applications into key themes.

Table 4.

Classification of AI applications into key themes.

| Theme | Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| T1. Product Monitoring & Lifecycle Management | Predict crop harvesting date [75] | R15. Improved harvesting accuracy and efficiency |

| T2. Logistics Optimization | Data analysis to identify optimal sites [44] | R4. Supported network design R5. Improved distribution efficiency |

| Waste collecting [76] | R5. Improved distribution efficiency | |

| Inventory and cash Management [47] | R16. Reduced the cash conversion cycle (CCC) for upstream operations | |

| T3. Resource Efficiency | Waste sorting [49] | R17. Made a separation for conversion and reprocessing |

| Waste Detection [77] | R18. Improved waste management procedures by waste detection | |

| Energy system planning optimization [78] | R19. Smart city development | |

| T4. Environmental Monitoring | Energy generation prediction and consumption patterns [79] | R20. Decentralized energy management and energy efficiency |

| T5. Operational Efficiency & Automation | Defect detection [51] | R21. Operational efficiency |

| Warehouse management [46] | R22. Enhanced resource allocation through automated ticket classification | |

| Remaining Useful Life (RUL) prediction [80] | R23. Maintenance optimization | |

| Predictive maintenance [48] | R2. Prevented breakdowns, failure prediction and extended product life | |

| T6. Strategic Analysis & Decision Support Platforms | Knowledge base development [50] | R24. Improved accuracy of risk assessment |

| Sustainability performance analysis [81] | R25. Decreased total cost R26. Decreased carbon emissions | |

| Demand prediction [82] | R27. Addressed the uncertainties associated with demand and recovery quantities | |

| Cost management [41,42] | R28. Cost structure estimation and collaborative price agreements | |

| Predictive analytics from mainstream [83] | R29. Energy wastage reduction | |

| Power production forecast [45] | R30. Performance improvement |

Table 5.

Classification of BC applications into key themes.

Table 5.

Classification of BC applications into key themes.

| Theme | Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| T1. Product Monitoring & Lifecycle Management | Tracking and tracing platform [84,85,86] | R31. Provided effective traceability and visibility |

| T2. Logistics Optimization | Dynamic optimization of delivery systems [87] | R32. Freshness preservation of products |

| Vehicle transport tracking and monitoring [54,55,56] | R33. Traceability and coordination between stakeholders | |

| T3. Resource Efficiency | Implement a digital token system and identity recognition mechanism [88] | R34. Analyzed defects in waste disposal practices |

| T4. Environmental Monitoring | Authorization of buildings for participation in energy trading [79] | R20. Decentralized energy management and energy efficiency |

| Automatic load response in local energy networks [89] | R35. Reduction in net load fluctuations, reduction in operational costs, improvement in renewable self-consumption | |

| Implementing a load-balancing strategy to optimize data distribution [60] | R36. Reduced energy consumption | |

| T5. Operational Efficiency & Automation | Ethereum smart contracts for information flow and payment transactions [90,91] | R37. Enhanced payment security |

| Facilitate pallet tracking and traceability [92] | R38. Industrial waste reduction | |

| Traceability of social sales [93] | R39. Increased throughput (transactions per second) and reduced latency | |

| Supplier selection [94] | R40. Improved quality control | |

| Develop smart contracts to enhance sustainable SC operations [83] | R29. Energy wastage reduction | |

| T6. Strategic Analysis & Decision Support Platforms | Supply chain stakeholders’ engagement [57] | R41. Increased customer willingness to pay, provide anti-counterfeit measures, and support circular business models |

| Information sharing [53,59,95] | R42. Improved transparency and supply chain processes |

- IV.

- Additive Manufacturing (AM)

AM, commonly referred to as 3D printing, differs from conventional subtractive manufacturing techniques by utilizing additive fabrication methods, in which three-dimensional objects are constructed layer by layer [96]. Case studies on AM within the context of iCSC processes focus on four primary techniques: powder bed fusion (PBF), material jetting, material extrusion, and vat photopolymerization.

Table 6 provides an overview of each process, emphasizing notable characteristics and unique features [97]. The Count row displays the distribution of AM techniques in iCSC studies.

Table 6.

Comparison of four AM techniques.

Table 7 presents the applications of AM across key themes, while Table A4 in the Appendix A provides detailed examples of AM applications in CSC.

Table 7.

Classification of AM applications into key themes.

- V.

- Digital Twin (DT)

DTs serve as virtual representations of physical objects, mirroring real-time behavior through ongoing data acquisition. DTs enable both static prognostic assessments during the design phase and dynamic, real-time synchronization and optimization.

In the context of CSC, DTs and simulation technologies are instrumental in managing complex SCs. They support closed-loop systems, optimize end-of-life disassembly processes, and facilitate the remanufacturing of complex products [107].

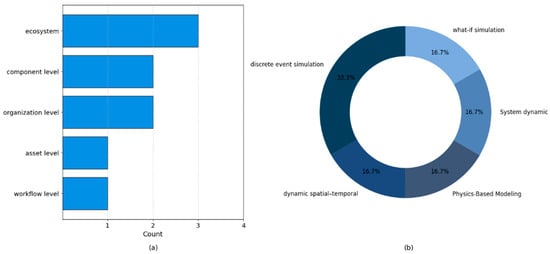

These simulations can be implemented at various levels of modularity, ranging from the component level and asset level to organization and ecosystem levels. The reviewed literature shows a stronger emphasis on higher levels of modularity, particularly at the organizational and ecosystem scales, reflecting a strategic focus on coordination, integration, and performance optimization across interconnected supply chain networks. This indicates that DT applications in CSCs are increasingly used as system-wide decision-support tools rather than isolated asset-level models. In terms of simulation techniques, discrete event simulation is the most frequently adopted approach, highlighting a preference for process-oriented analysis, operational scenario testing, and performance evaluation. Other approaches, including system dynamics, physics-based modeling, dynamic spatial–temporal simulations, and what-if analyses, are also employed, demonstrating the methodological diversity of DT-enabled CSC studies while reinforcing the dominance of process-level and scenario-driven modeling.

Table 8 presents the articles categorized into key themes, while Table A5 and Figure A2 in the Appendix A provide a detailed implementation of DT applications within the context of iCSC.

Table 8.

Classification of DT applications into key themes.

- VI.

- Cloud-based Platforms (CP)

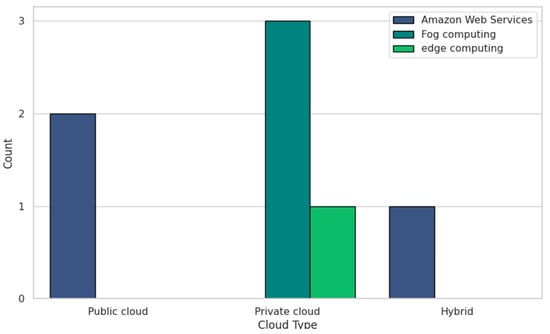

According to Ref. [116], cloud deployment models are classified as follows: Public Cloud provides cloud infrastructure to the public on a pay-per-use basis with dynamic resource allocation. Private Cloud is dedicated to a single organization and managed either internally or by a service provider, offering enhanced security. Hybrid Cloud combines public and private models to balance security and flexibility by linking resources across both. Community Cloud infrastructure is utilized collaboratively by organizations with common interests, such as compliance and security.

The distribution of CP types across the reviewed iCSC studies reveals a preference for centralized cloud infrastructures, particularly private cloud deployments. Most studies adopt private cloud solutions; often implemented using fog or edge computing paradigms; to address requirements related to data security, latency reduction, and localized processing. Public cloud platforms, primarily represented by large-scale providers, are also frequently used due to their scalability and cost-effectiveness, especially in data-intensive CSC applications. Hybrid cloud implementations appear less frequently, reflecting their more complex integration requirements despite their potential to balance flexibility and control.

Overall, these findings indicate that CP selection in iCSC applications is strongly influenced by trade-offs between scalability, security, and computational proximity. Table 9 summarizes the articles by key themes, while Table A6 and Figure A3 in the Appendix A provide a detailed overview of CP applications and the distribution of these cloud implementation types across iCSC applications.

Table 9.

Classification of CP applications into key themes.

- VII.

- Big Data (BD)

BD in SC literature is recognized as a strategic asset, enabling organizations to make informed business decisions. BD involves the use of advanced technologies and algorithms to extract meaningful insights and bridge the gap between people and technology.

By processing vast amounts of data, BD supports decision-making through the application of analytical models [124]. Table 10 presents the article details organized by key themes, whereas Table A7 in the Appendix A elaborates on BD implementation within the iCSC context.

Table 10.

Classification of BD applications into key themes.

- VIII.

- Cyber-Physical System (CPS)

CPS are commonly discussed in the literature in combination with other technologies. In the context of iCSC, CPS is frequently integrated with DT, CP, and the IoT to enhance system efficiency, enable real-time data processing, and optimize decision-making processes.

Table 11 presents the details of CPS articles organized by key themes, while Table A8 in the Appendix A provides details of studies on CPS technology within the iCSC context.

Table 11.

Classification of CPS applications into key themes.

4.2.2. CE Focus in iCSC

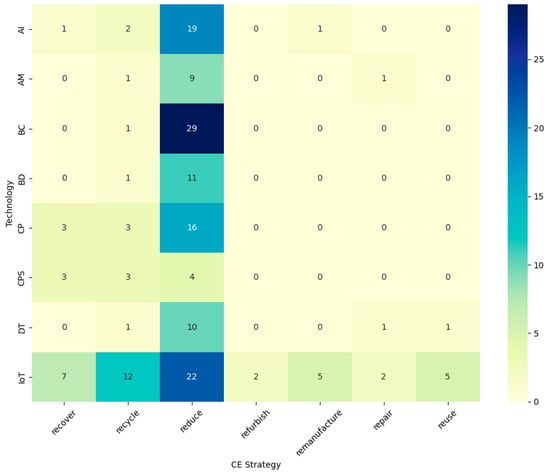

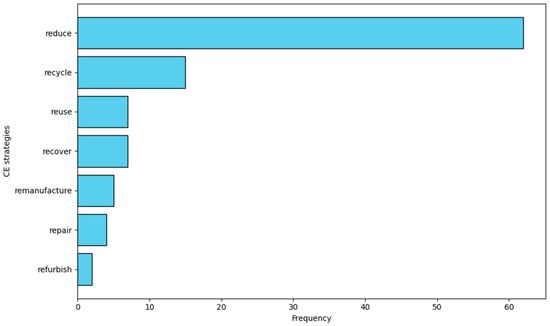

In this study, all implementations of iCSC align with at least one CE strategy. Among reviewed papers, the Reduce strategy is the primary focus, addressing objectives such as minimizing raw material extraction, reducing rework, improving general efficiency, and mitigating negative environmental impacts, including CO2 emissions. The other most frequent strategies are Recycle, followed by Reuse, Remanufacture, Recover, Repair, and Refurbishment.

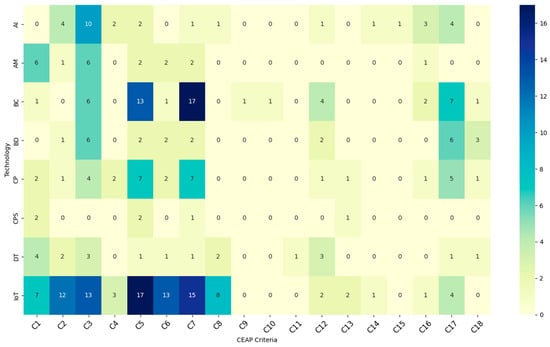

Figure 6 presents a heatmap that illustrates the alignment of CE strategies with a range of digital technologies such as IoT, AI, BC, AM, BD, CP, DT, and CPS. Each cell quantifies the strength of association between a given technology and a specific CE objective. In particular, BC exhibits the highest linkage to the Reduce strategy, highlighting its critical role in enabling transparency, traceability, and resource optimization. In addition, IoT shows broad applicability across multiple strategies, particularly Reduce, Recycle, and Recover, reflecting its utility in real-time monitoring, data acquisition, and operational efficiency within CSCs.

Figure 6.

Mapping of CE strategies across digital technologies.

4.2.3. iCSC Industrial Sector Applications

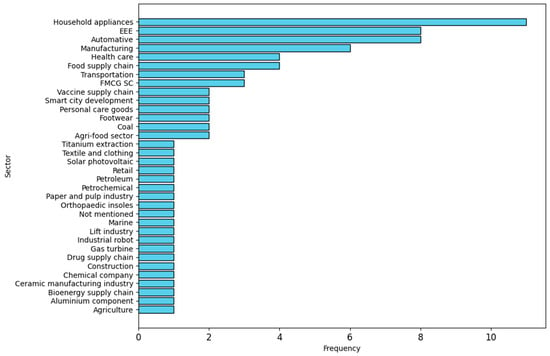

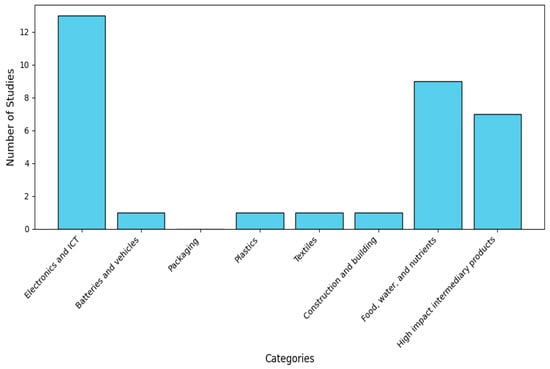

Figure 7 presents the distribution of sectors involved in iCSC applications. Household appliances emerge as a key focus area, reflecting notable progress toward sustainability in this sector. This prominence, enhanced by digital technologies, is attributed to the critical role household appliances play in daily life and their significant environmental impact across various dimensions, including:

Figure 7.

Application distribution in the context of iCSC.

- Circular manufacturing: Automating production processes for household appliances to improve efficiency and sustainability [122], while defining innovative sustainable business models [109].

- Household waste management [118]: Research and development in waste detection, sorting, collection, and pattern recognition to reduce household waste and enhance recycling efficiency.

- Consumption monitoring: Leveraging digital technologies to monitor energy or water usage in household appliances, enabling optimization [11].

According to CEAP, electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) ranks among the fastest-growing waste streams in the EU, with an annual growth rate of 2%. However, less than 40% of electronic waste is currently recycled in the region [2]. The analysis in this paper shows that electronic devices rank as the second most prominent sector within iCSC applications, highlighting companies’ proactive efforts to tackle sustainability challenges across both production and end-of-life (EoL) management processes. The automotive industry shares a position with EEE, focusing on improving the efficiency of manufacturing processes such as cost analysis [42] and efficient scheduling [12].

Following these, Manufacturing, Healthcare, and the Food supply chain emerge as additional important areas for iCSC application.

4.2.4. Alignment of iCSC Applications with the EU Circular Economy Action Plan

This section analyzes the alignment between the current status of iCSC applications and the EU CEAP, a strategic and operational action plan driving the transition towards CE. The analysis focuses on identifying how the implementation of iCSC technologies and practices corresponds with the objectives and initiatives outlined in the CEAP.

- I.

- Supply Chain-Related Criteria Extraction

Table 12 presents the criteria extracted from the CEAP that are relevant to SCs. The section, subsection and description columns provide details on the specific parts of the CEAP from which each criterion was derived, including the relevant section, subsection, and sentences from the CEAP document [2]. The criteria # column is used by the authors to assign unique numbers for mapping purposes, thereby establishing an approach for assessing the alignment of iCSC applications with CEAP objectives.

Table 12.

CSC-related criteria from CEAP.

- II.

- iCSC Application Analysis Based on CEAP Criteria

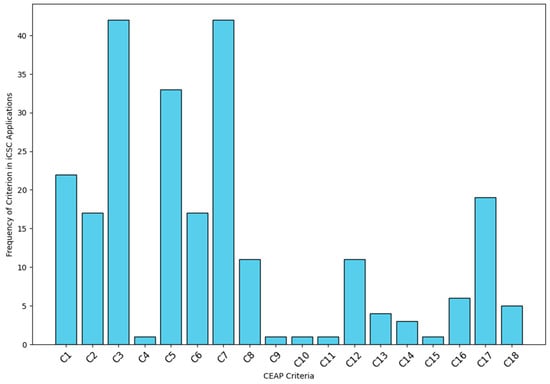

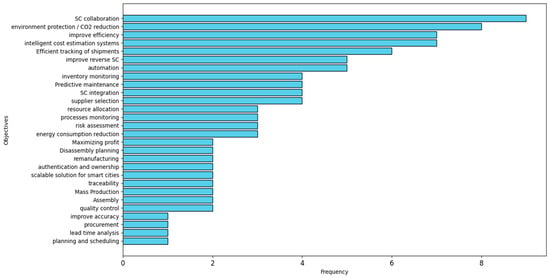

Figure 8 illustrates how the 95 papers are distributed across the 18 criteria. As illustrated in Figure 9, Criteria 3, 5, and 7 have a significantly higher presence in articles discussing implementing digital tools in the CSC. These criteria receive greater attention and focus on the literature, with more than 25 papers addressing each criterion, highlighting key areas critical to advancing CE goals:

Figure 8.

Mapping iCSC applications and CEAP criteria.

Figure 9.

Mapping digital technologies in iCSC application and CEAP criteria.

- Criterion 3 focuses on initiatives aimed at minimizing carbon emissions and reducing the environmental footprint. Technology plays a significant role in addressing pollution emissions, which can arise from various factors such as machine utilization, transportation and logistics. For instance, delays in information transmission across different stages of production, manufacturing, and the SC often exacerbate these emissions [64]. To mitigate this, IoT or AI technologies can be utilized to enable intelligent production scheduling and optimize logistics delivery models, promoting green and sustainable development in intelligent manufacturing. On the other hand, AM has emerged as a key digital technology in improving production efficiency by analyzing potential environmental impacts and enabling the transition to sustainable production processes through redesigned industrial-scale products [100].

- Criterion 5 emphasizes the importance of digitalizing product information and mobilizing digital resources to improve accessibility. I4.0 technologies, such as IoT for data collection and transmission, CP for data storage, and BC as a distributed ledger; enable secure and transparent exchanges among SC stakeholders. Product information is essential in SC management, particularly in sectors like food and pharmaceuticals, where safety is paramount. It ensures compliance with regulatory standards while addressing consumer expectations for product safety and transparency [85].

- Criterion 7 promotes the adoption of digital technologies to enhance the tracking, tracing, and mapping of resources, which is essential for improving transparency and data sharing in the CE. These technologies are vital for monitoring material lifecycles and ensuring that resources are managed sustainably. For example, reference [59] demonstrated how BC facilitates decentralized control, security, traceability, and auditable, time-stamped transactions, all of which are crucial for managing and tracking products throughout the supply chain. This capability enables the effective mapping of materials, ensuring they are sustainably sourced and processed. Additionally, reference [53] proposed a BC-based traceability framework for the textile and clothing supply chain, which enhances transparency across multiple tiers of production. [86] further highlighted BC’s efficiency in shipment tracking, showcasing its ability to optimize logistics and ensure the secure movement of resources.

Criteria 1, 2, 6, 8, and 17 are each addressed by more than 10 papers:

- Criteria C1 and C2 emphasize durability, remanufacturing, and high-quality recycling, particularly during the design stage. Product design plays a pivotal role in determining the feasibility and efficiency of recovery processes. Complex product designs can significantly increase disassembly costs, ultimately raising overall recovery expenses. By incorporating recovery operations into the product design phase, manufacturers can streamline EoL recovery processes, making them more effective and cost-efficient [69].

- Based on the priorities outlined in the CEAP, certain sectors are emphasized, including electronics, ICT, textiles, construction, and high-impact intermediary products such as steel, cement, and chemicals, categorized under Criterion 6. This criterion reflects the focus of articles on these key sectors. For instance, in the textile and clothing sector, [53] developed a framework for supply chain traceability, while in the coal industry, [63] implemented an Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT)-enabled monitoring and maintenance mechanism for fully mechanized mining equipment. Additionally, [73] explored smart coal port development.

- Criterion 17, which focuses on the CE stakeholder platform, highlights its role as a hub for stakeholder collaboration and information exchange. This includes the development of platforms based on BC, data gathering and transmission via IoT, efficient information storage, and the generation of actionable insights. Various decision support systems (DSS) have been developed for diverse objectives using AI and ML methods, demonstrating how advanced technologies are being integrated to advance CE goals.

Other criteria that received less attention can be seen as opportunities for future research. For example, Criterion 4, which focuses on product-as-a-service models or other approaches where producers retain ownership of the product, has potential for further exploration. Additionally, sectors such as plastics, textiles, construction, and food (Criteria 9 to 12) offer significant opportunities for deeper investigation, as these areas are crucial for advancing CE principles but have not been as extensively covered in the literature. Similarly, Criterion 14, which focuses on the development of solutions for high-quality sorting and removing contaminants from waste, Criterion 15, which addresses job creation to accelerate the transition to a circular economy, and Criterion 16, which highlights the intelligent cities, all present valuable areas for further research. Additionally, Criterion 18, which emphasizes the integration of sustainability criteria into business strategies, also represents an important avenue for future exploration.

The criteria that show strong links between the CEAP and iCSC indicate those that are leveraging digital tools and sustainable practices. Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of articles based on digital technologies and the mapping of these digital technologies in the iCSC to the CEAP criteria.

5. Conceptual Model for Practical Insight

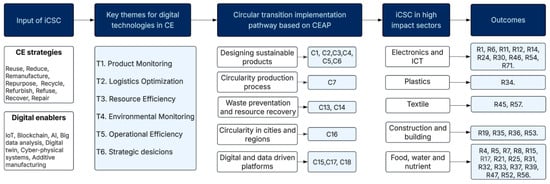

The conceptual model developed in this study provides practical insights by integrating digital enablers and CE strategies into a unified framework. It serves as a bridge between technological capabilities, strategic interventions, and sector-specific outcomes. The model begins with two main categories of inputs: digital enablers such as IoT, BC, AI, BD analytics, DT, CPS, CP, and AM; and CE strategies including reuse, remanufacture, repurpose, reduce, recycle, refurbish, refuse, recover, and repair. These represent the technological and strategic foundations for building intelligent and sustainable SCs. Together, these inputs form the foundational pillars for building intelligent and circular SCs.

Based on a systematic review of the literature, six key themes were identified that link digital enablers with CE strategies in practice: T1. Product Monitoring & Lifecycle Management; T2. Logistics Optimization; T3. Resource Efficiency; T4. Environmental Monitoring; T5. Operational Efficiency & Automation; and T6. Strategic Analysis & Decision Support Platforms. These themes serve as the bridge between system inputs and pathways for implementation.

To operationalize the model, the CEAP is employed. Key pathways from CEAP are extracted and mapped against the 18 evaluation criteria (C1–C18) introduced in Section 4.2.4. These criteria form the evaluative backbone of the model, covering the full spectrum of circular transition priorities; from sustainable product design (C1–C6) and circular production processes (C7), to sector-specific value chain interventions (C8–C12), waste prevention and resource recovery (C13–C14), social and regional enablers (C16), and digital and data driven platforms (C15, C17, C18). Embedding these criteria ensures that each digital-CE interaction is assessed not only in terms of technological capability but also in relation to policy alignment, environmental ambition, and practical feasibility. In this way, C1–C18 function as the structural link between the thematic clusters (T1–T6), the CEAP pathways, and the sector-level outcomes, enabling a coherent and traceable interpretation of how digital enablers operationalize CE strategies across different industrial contexts.

The outputs of the conceptual model comprise more than 70 sectors specific implementation results, each mapped to the priority areas outlined in the CEAP; namely ICT and electronics, plastics, textiles, construction and building, and food, water, and nutrients. The conceptual model brings structure to this large body of evidence by classifying each result according to the CEAP pathways, the 18 evaluation criteria (C1–C18), and the thematic clusters (T1–T6). In doing so, it reveals how digital enablers operationalize CE strategies across diverse industrial contexts. These results demonstrate the practical implications of implementing iCSC in real-world settings, as detailed in the technology overview tables provided in Section 4.2.1. Figure 10 presents the integrated conceptual model and serves as the central visual synthesis of these relationships.

Figure 10.

Conceptual model of the iCSC highlighting practical insights.

As an illustrative example of the conceptual model, reference [75] investigated the use of AI as a digital enabler for improving harvesting efficiency and reducing industrial waste (Reduce strategy). This case is categorized under T1 (Product Monitoring & Lifecycle Management), placed in the CEAP pathway of circularity in the production process, and mapped to criterion C7 (promoting the use of digital technologies for tracking, tracing, and mapping of resources). The corresponding sectoral result falls under food, water, and nutrients, with R15 identified as the outcome of this implementation (improved harvesting accuracy and efficiency). This example illustrates how digital enablers operationalize CE strategies, producing sector-specific outcomes.

6. Findings, Gaps Analysis and Future Opportunities

This section summarizes the findings and answers to the RQs. It also identifies existing gaps and suggests future research opportunities.

6.1. Digital Technologies in the Context of the CSC (RQ1)

Section 4.2.1 examines how digital technologies were applied within CSC and describes the specific subclasses of each technology. Figure 11 provides an overview of the distribution of these technologies across different applications, while Figure 12 highlights the primary objectives addressed in the literature. Despite the growing body of literature on digital integration in CSCs, notable gaps persist. Most studies treat digital technologies in isolation, overlooking the synergistic potential that arises when these technologies are combined. For instance, IoT serves as a critical source of AI and BD generation [135] and is closely connected to BC technology. Based on the findings by [32], combining BC and IoT can accelerate the realization of CE processes. These technologies help overcome procurement challenges in green and sustainable businesses, facilitate the integration of green SC stakeholders, and ensure the validity and authenticity of information. Moreover, the literature indicates that AI driven by BD analytics can enhance SC performance [136].

Figure 11.

Distribution of digital technologies within the context of iCSC.

Figure 12.

Objectives of articles within the context of iCSC.

As illustrated in Figure 12, stakeholder communication and decision-making support processes have garnered significant attention in practical studies. Collaboration mechanisms such as information sharing, joint planning, and decision-making are commonly studied and highlighted in the literature [30]. Although the role of data in facilitating effective communication among SC actors, including suppliers, manufacturers, and customers, has been examined across various stages of the product life cycle [30], significant challenges persist regarding data accessibility, quality, and interoperability [21].

BC, IoT, and cloud-based systems are frequently highlighted as critical enablers of collaboration mechanisms [30]. Additionally, BD and AI analytics can reveal hidden insights and valuable information, such as the connections between lifecycle decisions and process parameters, empowering industrial leaders to make more informed decisions in complex management environments [137]. BC technology, with its characteristics as a distributed digital ledger, ensures transparency, traceability, and security. It has demonstrated immense potential in addressing various challenges associated with global supply chain networks [138]. Similarly, DTs enable disseminating relevant information to the appropriate actors at the right time in a decentralized manner. DTs are expected to play a crucial role in the future, contributing significantly to the successful implementation of CE strategies [21].

Despite significant concerns regarding information and knowledge management [139], as well as stakeholder communication, studies indicate a saturation in the use of decision support systems, including fuzzy logic, expert systems, and multi-criteria methods. However, the literature still lags behind industry practices in leveraging more advanced methods [140]. A notable research opportunity lies in developing generic collaborative decision-making systems that facilitate optimal decisions by incorporating these advanced methodologies.

Similarly, there are still key areas that require further attention and improvement. For example, planning and scheduling, lead time analysis, and procurement present significant opportunities for future research. As noted by [12], the increasing pressure of global competition has forced manufacturers and distributors in the global supply chain to adapt quickly to market demands, shorten order-to-delivery (OTD) times, and reduce inventory. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for enhancing operational efficiency and maintaining competitiveness in the rapidly evolving market landscape. Future research in these areas will contribute to the development of more agile, responsive, and cost-effective supply chain practices.

6.2. CE Strategies in iCSC Applications (RQ2)

Section 4.2.2 explores the integration of digital technology applications with CE strategies. The analysis highlights a strong emphasis on the Reduce, Recycle, and Reuse strategies, while noting that practical implementations of iCSC have yet to adequately address the Refuse, Repurpose, and Rethink strategies.

The Repair and Reuse strategies are anticipated to become more important, especially in response to the EU directive on repairing goods [3]. which supports sustainable consumption by encouraging product repair and reuse, aligning with the goals of the European Green Deal [141]. The Repair strategy is projected to be increasingly driven by digital technologies, such as BD, ML and IoT, notably through initiatives like the European Online Platform for Repair.

According to Article 7 of the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) [142], products must be accompanied by information about durability scores and environmental footprints. ML models can analyze this data to predict product lifespan, environmental impact, and potential failures, aiding in informed product reuse or repair decisions. These parameters are crucial for determining whether a product should be repaired or reused.

6.3. Sectoral Analysis (RQ3)

Section 4.2.3 provides an overview of the sectors in which digital technologies have been integrated within their SC processes. The CEAP highlights several key value chains, as described in Section 4.2.4 [2], including Electronics and ICT, Batteries and Vehicles, Packaging, Plastics, Textiles, Construction and Building, Food, Water and Nutrients, and High Impact Intermediary Products. These sectors are pivotal for identifying obstacles to the growth of circular product markets and devising strategies to overcome them.

Among these sectors, Electronics and ICT emerge as the most prominent application areas for digital technologies in CSCs. This dominance can be attributed to several supply chain characteristics that make these industries particularly suitable for digitalization. These include short innovation cycles, strong regulatory pressure, and the need for precise tracking across production, use, and EoL stages. In addition, EEE represents one of the fastest-growing waste streams in the EU, with an annual growth rate of approximately 2%, while less than 40% of electronic waste is currently recycled [2]. These factors collectively explain the strong research focus on digital solutions for Electronic and ICT within iCSC applications.

In contrast to highly digitalized sectors, plastics and textiles remain comparatively underrepresented in iCSC research, despite their strategic importance within the CEAP. Plastics consumption is projected to double over the next two decades, while challenges such as low recycled content, plastic pollution, and the presence of microplastics persist across product lifecycles [2]. Similarly, the textile sector is among the highest contributors to raw material use, water consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions, yet less than 1% of textiles are recycled into new textile products [2]. These sectors are characterized by fragmented, globally dispersed supply chains, low-margin production structures, and limited traceability of material flows, which collectively hinder the adoption of advanced digital technologies.

The CEAP explicitly highlights the need for improved traceability, recycled content measurement, waste reduction, and lifecycle monitoring in plastics and textiles, alongside stronger support for reuse, repair, and extended producer responsibility schemes. However, the limited integration of digital enablers such as IoT, BC, and data analytics in these sectors suggests a significant research and implementation gap. Addressing this gap through iCSC-oriented digital solutions represents a critical opportunity to enhance transparency, material recovery, and circular value creation in alignment with CEAP objectives.

6.4. Aligning CEAP Criteria with iCSC Applications (RQ4)

Section 4.2.4 investigates how SC criteria relevant to the CEAP are addressed in academic literature and practical applications within iCSC. As illustrated in Figure 8, several criteria, despite their significant importance, remain underrepresented in real-world implementations:

- C4: Emphasizes shifting ownership models from consumers to producers (e.g., leasing or product-as-a-service models). This criterion is crucial for advancing circular practices but has received limited attention in actual supply chain transformations.

- C10 to C13: These criteria highlight the need to focus on key value chains such as plastics, textiles, and construction. However, there is a noticeable gap in research and application concerning these sectors.

- C13 and C14: Concentrate on improving waste management practices, specifically separate waste collection and high-quality sorting processes. Despite their relevance to achieving high recycling rates, these areas have not been widely implemented in practical iCSC scenarios.

- C15: Considers the potential for job creation within CE frameworks. Although job creation is a key benefit of circular transitions, there is insufficient exploration and evidence in existing studies linking CE strategies with employment outcomes.

6.5. An Integrative Conceptual Framework for iCSC Implementation (RQ5)

Section 5 conceptualizes the relationships between digital enablers and CE strategies, forming the inputs of the integrative model. Based on a review of 95 studies, the role of digital technologies in the context of CE synthesized into six key themes including product monitoring, logistics optimization, resource efficiency, environmental monitoring, operational efficiency & automation, strategic analysis and decision support platforms.

The implementation methods are mapped to actionable transition pathways derived from the EU CEAP, which include sustainable product design, circular production processes, waste prevention and resource efficiency, digital and data-driven platforms, and circularity at city and regional levels. The framework further operationalizes these strategies across key value chains; namely electronics and ICT, plastics, textiles, construction, and food; leading to distinct circular outcomes. By categorizing and linking these digital enablers, CE strategies, transition pathways, and resulting outcomes, the framework provides a theoretically grounded explanation of how digital technologies generate circular value in intelligent iCSCs, bridging practical implementation with conceptual understanding.

Although the framework provides a comprehensive overview, there are still several areas for improvement. Since most studies in this field focus on implementation, the availability of results across industries is limited due to confidentiality concerns. Future research could evaluate a broader range of studies to refine the framework and analyze a wider variety of industries. In the current study, the focus has been primarily on key value chains such as ICT, electronics, and the food industry, while sectors like plastics and textiles remain underexplored. Moreover, future work could establish a hierarchy of the obtained outcomes and map them to circular economy strategies more systematically, enhancing the theoretical and practical relevance of the model.

7. Conclusions

This study explores the practical perspectives of iCSC, emphasizing real-world applications and the implementation of digital technologies in industrial scenarios. By systematically analyzing 95 peer-reviewed studies, the paper classifies digital technologies according to their objectives, implementation mechanisms, and sector-specific outcomes. Notably, approximately 60% of the studies have applied IoT, BC, and AI technologies. In the context of CE strategies, particular emphasis has been placed on the Reduce strategy, which focuses on minimizing raw material usage, reducing rework, and enhancing efficiency.

The findings offer actionable insights for managers and practitioners aiming to enhance circularity in supply chains. Key sectors such as household appliances, EEE, automotive, and manufacturing, as well as value chains highlighted in the CEAP (batteries, vehicles, packaging, plastics, textiles, construction), present significant opportunities for digital technology adoption. The conceptual model developed in this study illustrates how digital enablers operationalize CE strategies, linking technological inputs, CE strategies, thematic areas, CEAP pathways, and sector-specific outcomes. This framework supports informed decision-making, sustainable resource management, and prioritization of digital solutions to improve both circularity and operational efficiency.

From a theoretical perspective, this study advances understanding by adopting a practice-oriented approach to digital technology implementation in iCSCs. Unlike previous reviews that were largely conceptual or technology-centric, this research provides insight into real-world applications and their alignment with CE strategies. The mapping of 18 CEAP criteria against the reviewed studies highlights well-covered areas (e.g., carbon emission reduction, digitalization of product information, tracking and tracing of resources) and identifies gaps for further theoretical exploration. This establishes a foundation for future research to deepen the understanding of the relationship between digital technologies and CSC performance.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. The analysis focused on implemented digital technologies in real-world iCSCs, and outcomes were classified based on reported applications; however, many outcomes were not measurable due to data confidentiality or anonymized sectors. Additionally, while the sectoral coverage is broad, it does not fully capture emerging industries or niche applications of digital technologies. Future research could address these gaps by exploring a wider range of sectors, including underrepresented areas such as plastics, textiles, and construction, and by systematically evaluating diverse implementations of digital technologies. There are also opportunities to develop advanced collaborative decision-making systems to optimize planning, scheduling, lead time analysis, and procurement, enhancing operational efficiency and competitiveness. The Repair and Reuse strategies are expected to gain prominence, particularly in light of EU directives promoting sustainable consumption, where digital technologies such as BD, ML, and IoT can support informed repair and reuse decisions. Further research should focus on improving traceability, lifecycle monitoring, and material recovery in key value chains, as well as exploring underrepresented CEAP criteria such as alternative ownership models, waste management, and job creation. Expanding empirical studies, establishing a hierarchy of outcomes, and systematically linking them to CE strategies will refine the conceptual model and strengthen both its theoretical and practical relevance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and P.G.; methodology, M.M. and P.G.; software, M.M.; validation, M.M.; formal analysis, M.M. and P.G.; investigation, M.M.; resources, M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., V.H., N.P., and P.G.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, P.G.; project administration, P.G.; funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union under their competitive HORIZONMSCA-2021-DN-01 (Marie Sklodowska-Curie Doctoral Networks) programme under Grant Agreement No. 101073508.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT by OpenAI (GPT-4 version) for the purpose of improving language clarity and editing the wording. The authors have reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SC | Supply chain |

| iCSC | Intelligent circular supply chain |

| CE | Circular economy |

| I4.0 | Industry 4.0 |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| BC | Blockchain |

| DT | Digital twin |

| IoT | Internet of things |

| CPS | Cyber-physical system |

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| BD | Big data |

| CP | Cloud-based platform |

| CEAP | Circular Economy Action Plan |

Appendix A

In this appendix, the implementations of each technology are presented in detail. For each technology, the type, specific implementation procedures, objectives, applications, and resulting outcomes are provided. This information is intended to offer a comprehensive understanding of the application and effects of each technology.

Table A1.

Details of IoT implementations within the context of iCSC.

Table A1.

Details of IoT implementations within the context of iCSC.

| Ref. | Layer | Objective | Methodology | Application and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | Data Perception: Integrated Sensors | Coordination issues for a CSC consisting of a web-based recommerce platform and an IoT-enabled original equipment manufacturer (OEM) |

|

|

| [67] | Data Perception: sensors measuring soil nutrients (NPK Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium), humidity, temperature, and pH levels | Improve partner communication to enhance decision-making |

|

|

| [72] | Data Perception: RFID | Performance improvement |

|

|

| [43] | Data Perception: GPS, RFID | Sustainable supply chain network |

|

|

| [62] | Data Perception: Integrated Sensors | Maximizing total profit |

|

|

| [63] | Data Perception: Industrial Internet of Things (e.g., RFID, temperature sensor, vibration sensor) | Real-time monitoring and automation of smart mining |

|

|

| [10] | Data Perception: RFID/GPS; Network Layer: WSN | Resource allocation and efficiency |

|

|

| [48] | Data Perception: Various sensors (motion, speed, weight, temperature, electrical current, vacuum, air pressure) | Predictive maintenance |

|

|

| [92] | Data Perception: RFID, QR code | Enhance sustainability and operational effectiveness |

|

|

| [58] | Data Perception: Fill level sensors (infrared and ultrasonic) | Automation of scrap metal monitoring |

|

|

| [73] | Network Layer: WSN | Intelligent operation control system |

|

|

| [11] | Network Layer: WSN | Energy and water consumption monitoring |

|

|

| [64] | Data Perception: Smart sensors | Improve efficiency and integrated production- delivery model |

|

|

| [65,66] | Data Perception: RFID, GIS, 4G de- vices, GPS | Optimize logistics resources |

|

|

| [61] | Data Perception: RFID; Network Layer: Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE)/LoRaWAN | End-to-end solution for reverse supply chain |

|

|

| [69] | Data Perception: RFID | Advanced Remanufacturing-To-Order-Disassembly-To-Order |

|

|

| [70] | Data Perception: RFID | Improve disassembly and recycling processes |

|

|

| [68] | Data Perception: Gas detector, temperature. Network Layer: Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) | Air quality control |

|

|

| [66] | Data Perception: Smart sensors | Data collection and tracing in food supply chains |

|

|

| [73,74] | Data Perception: Embedded sensors | Enhance information exchange in reverse supply chains improving recycling and disassembly |

|

|

| [71] | Data Perception: Sensors and RFID tags | Improve reverse supply chain processes |

|

|

Table A2.

Details of AI implementations within the context of iCSC.

Table A2.

Details of AI implementations within the context of iCSC.

| Ref. | Model | Objective | Methodology | Application and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Sustainable and robust bioethanol supply chain network |

|

|

| [50] | Natural Language Process (NLP) | Improve accuracy of risk assessment |

|

|

| [79] | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | Decentralized energy management |

|

|

| [78] | Genetic Programming (GP) and ANN | Energy system planning optimization |

|

|

| [81] | Unsupervised algorithm | Circular bioenergy supply chain optimization |

|

|

| [75] | Deep learning | Predict crop harvesting date |

|

|

| [51] | Generative AI | Enhance operational efficiency |

|

|

| [49] | Image processing | Reduce energy consumption and network costs |

|

|

| [82] | Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Multi-Community Particle Swarm Optimization (MPSO) | Minimize total costs and reduce carbon emissions |

|

|

| [76] | Modified Gray Wolf Optimization (MGWO) heuristic method | Waste management, environ- mental effects, coverage demand, and delivery time |

|

|

| [47] | Decision Tree Algorithm | Inventory and cash management |

|

|

| [46] | Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, SVM, Neural Network | Warehouse management |

|

|

| [42] | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Cost structure estimation |

|

|

| [77] | Image Identifier | Identify and measure household waste |

|

|

| [83] | Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-mean clustering | Reduce energy wastage and financial transactions |

|

|

| [41] | statistical learning, deep learning, and multi-agent theory | Cost estimation |

|

|

| [80] | Cox regression | Maintenance cost Optimization |

|

|

| [48] | Random Forest | Predictive maintenance |

|

|

| [45] | standard RNNs, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Gated Recur- rent Units (GRUs) | Power production forecasting of photovoltaic (PV) systems |

|

|

Table A3.

Details of BC implementations within the context of iCSC.

Table A3.

Details of BC implementations within the context of iCSC.

| Ref. | Type | Objective | Methodology | Application and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [87] | Permissionless | Improve delivery system, with a focus on maintaining freshness and ensuring greenness |

|

|

| [79] | Permissionless –Ethereum BC | Decentralized energy management |

|

|

| [54] | Permissionless –Ethereum BC | Enhance resilience, transparency, and reliability |

|

|

| [89] | Permissionless | Automatic load response in local energy networks |

|

|

| [60] | Tailored approach | Reduce energy consumption |

|

|

| [57] | Permissionless –NFT | Supply chain stakeholders’ engagement |

|

|

| [93] | Permissioned –Hyperledger Fabric | Traceability of social sales |

|

|

| [88] | Permissionless | Marine plastic debris management |

|

|

| [55] | Permissioned | Enhance transparency, reliability, and cost-efficiency in urban distribution system |

|

|

| [56] | Permissionless –Ethereum BC | Track and trace retail coffee bags |

|

|

| [119] | Permissionless and Permissioned –Ethereum BC, CoAP | Blockchain-empowered decentralized and scalable solution for a sustainable smart-city network |

|

|

| [94] | Permissioned –Hyperledger Fabric | Blockchain-Based Cloud Manufacturing SCM System for Collaborative Enterprise Manufacturing/Supplier selection |

|

|

| [59] | Permissionless –Ethereum BC | Information sharing among stake- holders |

|

|

| [83] | Permissionless | Enhance sustainability in supply chains; reduce energy and hidden costs |

|

|

| [90] | Permissionless –Ethereum BC | Procurement, traceability and advance cash credit payment |

|

|

| [92] | Consortium –Azure BC Service | Enhance sustainability and operational effectiveness |

|

|

| [140] | Permissioned/ Hybrid BC | Promote sustainable food supply chains, support SDGs |

|

|

| [95] | Permissionless –Hyperledger Fabric and Sawtooth | Highly Integrated Supply Chains in Collaborative Manufacturing |

|

|

| [84] | Permissionless –Hyperledger Fabric | Tracking and tracing platform |

|

|

| [53] | Permissioned– Unique ID per partner | Tracing system |

|

|

| [85] | Local private Blockchain -Ethereum BC | Food Traceability Information System |

|

|

| [91] | Permissionless –Bitcoin/Xuper | Blockchain auto supply chain finance |

|

|

| [86] | Permissionless –Ethereum BC | Efficient tracking of shipments |

|

|

Table A4.

Details of AM implementations within the context of iCSC.

Table A4.

Details of AM implementations within the context of iCSC.

| Ref. | Technology | Objective | Methodology | Application and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [100] | FDM | Reducing environmental impact |

|

|

| [103] | SLM | Cost and environmental impact |

|

|

| [105] | SLS+ ElectroOpticalSystems (L-PBF) | Mass production |

|

|

| [98] | EBM, SLS, SLM, SLA, FDM, DMLS | Optimize city manufacturing layouts for AM facilities |

|

|

| [99] | PBF | Sustainable metal powder production for AM with CE practices |

|

|

| [102] | FDM | Cost reduction |

|

|

| [104] | SLM | Cost reduction |

|

|

| [106] | PolyJet, FDM, SLA, SLS | Reduce lead time and total production cost |

|

|

| [100,101] | SLM/Laser Beam Melting (LBM) | Reducing environmental impact |

|

|

Table A5.

Details of DT implementations within the context of iCSC.

Table A5.

Details of DT implementations within the context of iCSC.

| Ref. | Approaches/Modularity Level | Objective | Methodology | Application and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [113] | Approach: Discrete event simulation Modularity level: Ecosystem | Increase SC level of readiness in the face of unexpected and disruptive events |

|

|

| [111] | Approach: What-if simulation Modularity level: Ecosystem | Design, control and transparency |

|

|

| [47] | Approach: Discrete event simulation Modularity level: Ecosystem | Manage inventory and cash during disruptions |

|

|

| [109] | Approach: System dynamic Modularity level: Organization | Innovate the sustainable business model |

|

|

| [110] | Approach: Dynamic spatial temporal knowledge graph Modularity level: Organization | Resource allocation decision-making |

|

|

| [114] | Modularity level: Work-flow | Application of CE principles to the building context |

|

|

| [108] | Modularity level: Asset | Monitor and Optimize asset behavior |

|

|

| [112] | Modularity level: Component/ Organization | Intelligent and automatic decision-making |

|

|

| [115] | Approach: Physics-Based Modelling Modularity level: Component | Accurate RUL estimation for predictive maintenance and planning |

|

|

Table A6.

Details of CP implementations within the context of iCSC.

Table A6.

Details of CP implementations within the context of iCSC.

| Ref. | Type | Objective | Methodology | Application and Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [120] | Public, Private and Hybrid | Improve efficiency and reduce energy consumption |

|

|

| [117] | Private Cloud | Optimize logistics operations |

|

|