1. Introduction—First Lines of Code

In 2003, as a young lecturer, I saw research as a craft to be learned, not a tally to be scored. Each experiment felt like a line of code added to a program whose full output I could not yet see. Only later did I realize how deeply the culture of “publish or perish” runs (Parchomovsky, 2000). That pressure can push us forward, but it can also leave us feeling lost at sea.

In my first years, I waited nervously for reviewers’ comments and allowed rejections to shape my sense of worth. Over time, in 2023, as a senior academic with full professorship, critical reflection on my own journey helped me to reframe this experience (Cano & Đokić, 2025; Daudelin, 1996). In a later note on passion and mentorship, I described how basic ecological projects became “where the flame endures,” sustaining curiosity even when external metrics did not reward them (Yap, 2025e). In another reflection on writing systems, I explained how steady, clock-based routines allowed me to work on manuscripts without becoming paralyzed by perfectionism (Chandran, 2024; Farrelly, 2025).

They are also grounded in my series of reflection articles on mentors, students and the enduring importance of basic biology (Yap, 2025c); on mussels and planetary health (Yap, 2025b; Pfister et al., 2018); and on “still water” after storms (Yap, 2025a). These pieces gradually shifted my perspective: publishing became less about survival and more about conversation, meaning-making, compassionate feelings being a living being, mentorship and self-education.

Drawing on these personal experiences, or autoethnography, as well as on the wider literature about reflective practice and retirement (Yap, 2025a; Jasper, 2005; Alt et al., 2022; Lyon & Inamdar, 2025; Woodford et al., 2023; Fitchett, 2024), this paper sets out five principles that have emerged from my academic journey.

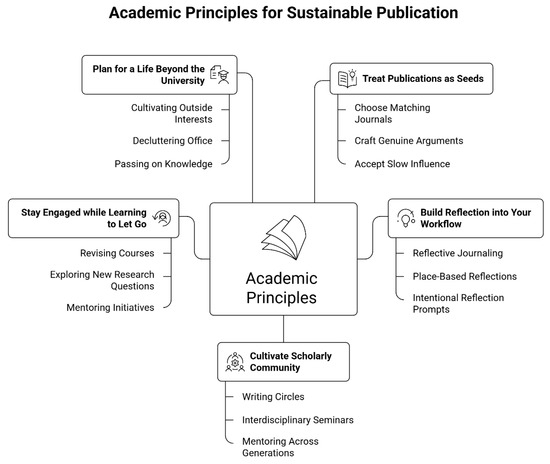

2. Mapping the Five Principles of a Sustainable Publishing Life

Figure 1 presents a conceptual mind map summarizing five inter-related principles that support a sustainable publication journey. There is “Academic Principles” at the center, surrounded by nodes that highlight treating publications as seeds, building reflection into daily workflow, cultivating scholarly community, staying engaged while learning to let go and planning for a life beyond the university. Each principle is illustrated with key practices, including choosing the right journals and crafting authentic arguments, using reflective journaling and place-based reflections, joining writing circles and interdisciplinary seminars, revising courses and mentoring and cultivating outside interests while decluttering and passing on knowledge. Together, these elements depict how intentional habits in research, teaching, mentorship, and life planning can help academics to maintain meaningful, ethical and resilient publication practices from early in the career through to retirement.

Figure 1.

Academic principles for sustainable publication across the course of academic life.

2.1. Principle 1: Consider Publications as Seeds, Not Trophies

First, consider publications to be seeds, not trophies. Early in my career, I looked at each paper as a tiny program whose objective was just to “run” without crashing. Pressure to publish fast and frequently is real; indeed, the “publish or perish” maxim seems to suggest that we have to submit our research or lose our jobs. Of course, this attitude has its downside: this tendency often ends up leading to the publishing of shallow or repetitive contributions.

Seeing publications as seeds shifts the logic. A seed must be planted in appropriate soil, nurtured and given time. In publishing terms, this means choosing journals that match the scope and audience of a study, crafting arguments that genuinely add to ongoing conversations and accepting that influence may emerge slowly. In my reflection on basic biology as a lifelong foundation, I argued that deceptively simple projects, such as observing plants colonizing a cracked badminton court after heavy rain, can carry deep lessons for resilience and long-term thinking (Yap, 2025a). Similarly, in “The basic is still basic,” I suggested that foundational biological questions often pursued in modest settings provide the root system for later, more visible achievements (Yap, 2025c). A similar logic underpinned our long-range review in environmental psychology, which grew out of many small studies into a single integrative narrative that maps trends and future directions.

This metaphor of the seed also made its way into my coastal musings. In “Mussels, memory, and the recorders of the coast,” I called Perna viridis and other bivalves living archives of heavy metals and pollution histories, the quiet recorders of environmental change over time (Yap, 2025b). These mussel-based narratives show how a long sequence of papers, student projects and field campaigns can be read as a single extended planting: each study is a seed contributing to the larger forest of understanding about coastal pollution and planetary health.

Treating publications as seeds also resists the temptation to convert them into trophies for display. In a reflection on passion and mentorship rooted in basic ecological research, I emphasized that what matters in the long run is not the acclaim of individual outputs but the cumulative impact on students, ecosystems and public understanding (Yap, 2025e). Over a long career, producing a diverse and healthy range of publications, rooted in genuine questions, matters more than creating a monoculture of superficially impressive outputs. Some seeds germinate quickly; others lie dormant and are rediscovered when new environmental, psychological or educational challenges arise (Yap, 2025c; Stokols, 1995; Tam, 2025; Urai et al., 2025).

2.2. Principle 2: Build Reflection into Your Workflow

The second principle is to build reflection into your normal workflow rather than treat it as an optional extra. Dewey (1933/1997) described reflective thought as the “active, persistent, and careful consideration” of beliefs and knowledge claims. Contemporary studies show that reflective journal writing enables learners to critically review their behaviors, connect new information to prior knowledge and develop deeper understanding (Alt et al., 2022; Hughes et al., 2019). Similar in tone, my review of environmental psychology also built on the ways in which people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviors are formed through ongoing reflection upon the physical and social environments that they inhabit (Stokols, 1995).

In my own practice, the reflective journals started as a private survival strategy. Following each project, I noted methodological difficulties, emotional reactions to reviews and questions that were not resolved. Over time, these notebooks developed into raw material for published reflections. “Where the flame endures” showed how basic ecological research, when reflected upon with care, can keep scientific curiosity alive amid administrative pressures (Yap, 2025e). My personal essays about changes in the skyline, clouds and towers further illustrate the way in which everyday scenes may be used as triggers for deeper reflection upon resilience, hope and the passage of time (Fitchett, 2024; Stokols, 1995).

It has also occurred in place. In “Air termenung (still water) after the storm,” still rainwater pooling on a cracked court became a metaphor for pausing, observing and integrating lessons after turbulence (Yap, 2025a). A more intimate form of reflection appears in my narrative about email exchanges with Professor Piotr Szefer, where careful re-reading of his messages revealed layers of mentorship, trust and scholarly expectations that continue to shape how I supervise students (Yap, 2025a). These place- and relationship-based reflections remind me that thinking about research cannot be separated from environments—mountain paths, coasts, cityscapes, inboxes, urban courts—where ideas and emotions are tested and retested (Cano & Đokić, 2025; Stokols, 1995; Tam, 2025; Urai et al., 2025; Yap, 2025d).

Lyon and Inamdar (2025) provided a useful framework for intentional reflection in academic careers, suggesting prompts such as “What did I learn about myself?” and “Which skills did I use?” after key experiences. Adapting their questions, after each article or reflection, I began to ask “What did this project reveal about my assumptions, my time management and my collaborations?” In the laboratory and classroom, I encouraged students to add short reflective notes to their reports, connecting data with feelings of confusion, curiosity or frustration. Research indicates that such practices support self-regulation and lifelong learning (Alt et al., 2022; Stokols, 1995; Yap, 2025d).

Embedding reflection into daily academic work is, therefore, not a luxury but a core part of programming a sustainable publication trajectory. It allows errors to be caught early, successes to be understood and patterns to be recognized across projects and years—whether those projects concern mussels and metals, environmental psychology, skyscrapers and clouds or emails exchanged across continents (Stokols, 1995; Tam, 2025; Urai et al., 2025; Yap, 2025d).

2.3. Principle 3: Cultivate Scholarly Community

The third principle is to cultivate scholarly community. Writing may feel solitary, but sustainable publication is rarely an individual achievement. Studies of problem-based learning show that collaborative reflection helps participants to review group processes, apply strategies to new problems and assess their own progress (Li et al., 2023). Kruger (2022) similarly demonstrated how collaborative spaces foster critical reflection in pre-service teachers, enabling them to challenge their assumptions and refine practice.

My own reflections often trace how community forms around science. In “Mussels, memory, and the recorders of the coast,” I emphasized how long-term mussel monitoring depended on networks of students, technicians and collaborators who shared sampling trips, laboratory benches and data interpretation (Yap, 2025b; Pfister et al., 2018). My comprehensive review of environmental psychology also emerged from engagement with a wide scholarly community across six decades of research, mapping shared themes and debates regarding how humans relate to their environments (Stokols, 1995). These essays show that even highly technical or synthetic papers sit within a web of relationships.

Community also appears in more intimate settings. “What These Emails Taught Me” goes even deeper into one mentoring relationship, showing how years of email exchanges with Professor Piotr Szefer shaped my scientific identity and my own responsibilities as a mentor (Yap, 2025d). Together, these pieces illustrate how digital communication might deepen loneliness or sustain scholarly relationships, depending on how we use it.

Within the department, writing circles and informal discussion groups have enabled the creation of practical infrastructure for community. Regular meetings in which drafts are shared, rejections analyzed and ideas tested closely align with evidence suggesting that collaborative reflection enhances self-assessment and problem-solving (Li et al., 2023; Kruger, 2022). Scenes from my field and laboratory reflections—students at intertidal mudflats, at cracked courts, under changing city skylines, on mountain trails, etc.—capture how collective experiences feed into both empirical and reflective publications (Cano & Đokić, 2025; Daudelin, 1996; Yap, 2025b; Pfister et al., 2018; Yap, 2025a).

The implication, then, is that cultivating scholarly community means more than being socially friendly. This is about intentional practices such as joining or initiating writing groups, participating in interdisciplinary seminars (as I did to bridge ecotoxicology and environmental psychology), mentoring across generations and recognizing the invisible labor of peer reviewers and editors. Community is both a support system and responsibility; how we participate in it shapes the conditions under which others can publish.

2.4. Principle 4: Stay Engaged While Learning to Let Go

The fourth principle is to stay engaged while learning to let go. Mid- and late-career academics inhabit a tension between deep institutional experience and the risk of stagnation. Shaw (2023) encouraged senior faculty to revise courses, experiment with new approaches and remain intellectually alive rather than drifting toward disengaged retirement. Remaining engaged—in curriculum redesign, new research questions and mentoring initiatives—has kept my own teaching and research fresh and generated new empirical and reflective research.

Reflections such as “Where the flame endures” and “The basic is still basic” emphasize that engagement does not always mean chasing new trends; it can mean returning to foundational topics with a renewed perspective (Yap, 2025c, 2025e). In those pieces, I argued that revisiting basic ecology and fundamental biology, especially with new cohorts of students, keeps both teacher and curriculum alive. At the same time, I acknowledged the danger of becoming overly attached to methods, positions or skylines simply because they are familiar.

Shaw (2023) also warned against the temptation to control everything. This also means that senior academics should refrain from taking up all committee positions or talking in every discussion. Knowing how to say no to a position and to amplify other people, especially the leadership of younger colleagues, is already an act of responsible engagement. In my writings reflecting on writing routines and mentorship, I frame this often as a move from being the “main author” of a program to a supportive debugger of others (Yap, 2025d, 2025e). The job gradually becomes less about proving oneself and more about creating conditions in which others can thrive, much as Professor Szefer’s emails modeled generous guidance without micromanagement (Yap, 2025d).

Letting go also involves loosening attachment to conventional markers of prestige. Staying engaged means continuing to teach, write and mentor with energy; learning to let go means making peace with the fact that institutions and skylines will evolve without us and that my role is to facilitate that evolution rather than to resist it.

2.5. Principle 5: Plan for a Life Beyond the University

The fifth principle is to plan for a life beyond the university. Retirement is inevitable; thinking about it early can guide how you build your career. Research into academic retirement presents this transition as paradoxical because, although it offers freedom, it disrupts identity and social networks. Woodford et al. (2023) illustrated how most academics identify university life as more than a job, using the description of Stebbins (2019) of academia as “occupational heaven,” but also warn that an unplanned exit from this position is deeply lonely and disorienting. Porter et al. (2025) stated that, quite frequently, retired scholars still contribute intellectually; however, these roles require renegotiation and clear expectations.

My own musings increasingly dwell on continuity and life after formal positions. Together with coastal reflections that look outward from mussels to planetary health (Yap, 2025b; Pfister et al., 2018) and with the long-range synthesis in environmental psychology (Stokols, 1995), these pieces sketch a vision of post-retirement life that remains intellectually and ethically engaged even if formal titles change.

Shaw (2023) offered practical suggestions: leave while colleagues still want you to stay, cultivate interests outside academia and declutter your office as both a symbolic and practical act. Passing annotated books to students feels like planting intellectual cuttings into new soil; sharing field photographs, skyline reflections or mentorship stories with younger colleagues is another way of handing over narrative threads (Yap, 2025c, 2025d; Tam, 2025; Urai et al., 2025). In my writing on basic biology and on passion and mentorship, I argued that the true measure of an academic career lies not in titles but in the independence and integrity of former students and collaborators (Yap, 2025c, 2025d, 2025e). Planning for life beyond the university, therefore, means trusting that these students and colleagues will carry forward the research in their own ways in laboratories, classrooms, city streets and new institutions.

For younger scholars, this principle does not imply early detachment. Rather, it suggests building a career whose core motivations—curiosity, care for ecosystems, commitment to students, joy in writing and sensitivity to place—can survive changes in institutional affiliation (Cano & Đokić, 2025; Yap, 2025a, 2025b, 2025c; Pfister et al., 2018). Hobbies, friendships and community commitments outside academia are not distractions; they are additional lines of code that will keep running even when the main institutional program is closed.

3. Concluding Remarks: Logging Out

Looking back, my publications read like a changelog. Some entries mark major breakthroughs; others document minor bug fixes. Together they form the program of my academic life. As retirement approaches, I do not see an end to learning; I see a transition to a different function call. Research on retirement from academia reminds us that leaving the university can be both liberating and disorienting, as scholars renegotiate meaning, contribution and community. The five principles discussed here—treating publications as seeds rather than trophies, building reflection into workflow, cultivating community, staying engaged while learning to let go and planning for life beyond the university—have emerged gradually from decades of empirical research and from the reflection articles that accompanied that journey in different environments, such as mountains, coasts, courts and the classroom. Simple metaphors from programming and ecology—seeds, loops, debugging, release candidates, still water after storms—can make complex academic processes clearer. My hope is that these principles help younger scholars to approach publication not as a frantic race but as a thoughtful craft. When the time comes to log out, may you leave behind a well-documented codebase for others to build upon and a life beyond the terminal window that continues to compile meaning.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alt, D., Raichel, N., & Naamati-Schneider, L. (2022). Higher education students’ reflective journal writing and lifelong learning skills: Insights from an exploratory sequential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 707168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, C., & Đokić, J. (2025). Empirical psychology, evolution, and environmental aesthetics. In G. Parsons, N. Hettinger, & S. Shapshay (Eds.), Routledge handbook of nature and environmental aesthetics (pp. 160–173). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S. (2024). Writing from my heart. Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, 24(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Daudelin, M. W. (1996). Learning from experience through reflection. Organizational Dynamics, 24(3), 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1997). How we think. Dover. (Original work published 1933). [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly, D. (2025). Turning the internet green: A call for environmental psychology to go online. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 107, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, A. (2024). The transition to retirement from academia. South African Journal of Science, 120(7–8), 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J. A., Hay, J., & Woolley, T. (2019). A comprehensive reflective journal-writing framework for nurse practitioners. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 83(2), 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, M. A. (2005). Using reflective writing within research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 10(3), 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, C. G. (2022). Collaborative learning to foster critical reflection by pre-service teachers. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 33(3), 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A., Chan, S., & Hwang, N. (2023). Measuring group function in problem-based learning: Development of a reflection tool. BMC Medical Education, 23, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, L., & Inamdar, A. (2025, May 12). The power of reflection and intentionality. Inside Higher Ed. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/career-advice/carpe-careers/2025/05/12/power-reflection-career-planning-opinion (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Parchomovsky, G. (2000). Publish or perish. Michigan Law Review, 98(4), 926–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, L., Thielen, F., Deloule, E., Valle, N., Lentzen, E., Grave, C., Beisel, J.-N., & McDonnell, J. J. (2018). Freshwater pearl mussels as a stream water stable isotope recorder. Ecohydrology, 11(7), e2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. M., Anderson, L., & Bell, S. (2025). Experiences of senior scholars and professors emeriti: Continuing academic contributions in retirement. Tertiary Education and Management, 31(2), 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S. M. (2023, February 8). Retirement planning for professors. Inside Higher Ed. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/career-advice/2023/02/08/14-recommendations-professors-approaching-retirement-opinion (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Stebbins, R. A. (2019). Community social involvement in academic retirement: Finding sociological meaning in free time. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 2(4), 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. (1995). The paradox of environmental psychology. American Psychologist, 50(10), 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K. P. (2025). Recognizing climate change as global: Implications for environmental psychology research. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 108, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, A. E., Dablander, F., & Bolderdijk, J. W. (2025). Impactful environmental psychology needs formal theories. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 66, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, K., Hutchinson, S. L., & Ausman, C. (2023). Retiring from “university life”: Critical reflections on a retirement lifestyle planning program. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 6(1), 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C. K. (2025a). Air termenung (still water) after the storm: A cracked court, resilient plants, and lessons for life. International Journal of Hydrology, 9(4), 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C. K. (2025b). Mussels, memory, and the recorders of the coast: A reflective note on heavy metals, coastal pollution, and planetary health. Journal of Life Science Systems and Technology, 1(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, C. K. (2025c). The basic is still basic: A biology professor’s philosophy and personal reflection. i TECH MAG, 7, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, C. K. (2025d). What these emails taught me: A personal reflection on mentorship from Professor Piotr Szefer. i TECH MAG, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, C. K. (2025e). Where the flame endures: Passion, mentorship, and writing rooted in basic ecological research. MOJ Biology and Medicine, 10(2), 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.