Abstract

Secondary research is a cornerstone of health sciences, with substantial implications for clinical practice and health policy. Within the systematic review process, a key step is assessing study quality and risk of bias. Among the tools available for evaluating observational studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) holds a prominent position and is widely applied in medical research. However, ambiguities and excessive subjectivity have been noted in its application. In this commentary, we discuss the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale guidelines, providing illustrative examples and practical recommendations for completing its items. Improving the accuracy of risk-of-bias assessment is crucial for enhancing the reliability of data synthesis and interpretation in the health sciences.

1. Introduction

Scientific research can be broadly classified into two main modalities: primary research and secondary research. Primary research generates new knowledge through original data collection. Secondary research, in contrast, reanalyzes existing data, often through systematic reviews, which can provide more precise answers to specific medical questions by integrating multiple primary studies and applying robust statistical methods. In particular, meta-analysis—described as “the analysis of analyses” (Glass, 1976)—aggregates and quantitatively evaluates data from prior studies.

A prerequisite for ensuring the reliability of secondary research is the rigorous assessment of the study quality and risk of bias of the individual studies included (Burns et al., 2011; Luchini et al., 2021). Even when a meta-analysis is not possible due to heterogeneity in study designs (e.g., different interventions) or population characteristics (e.g., different age groups), evaluating risk of bias remains essential for interpreting findings and assessing between-study variability (Viswanathan et al., 2017). When performed rigorously, secondary research can substantially influence health sciences, public health, clinical practice, and health policy, while fostering collaboration among evidence synthesizers, researchers, clinicians, health promoters, and policymakers (Siemens et al., 2023; Norheim et al., 2021; Whitty, 2015).

Bias refers to any systematic deviation that distorts results away from the true state of reality. Risk-of-bias assessment entails identifying potential sources of such distortions (Delavari et al., 2023), while study quality refers to judgments regarding the overall strength of the body of evidence (Viswanathan et al., 2017). Inadequate or inappropriate assessments may lead to misleading conclusions (NHMRC, 2019), result in wasted resources, and yield ineffective interventions (Gebrye et al., 2023). Accordingly, methodological tools must be carefully chosen to match the type of study—whether clinical or preclinical (Gebrye et al., 2023; Zeng et al., 2015).

Several instruments are available for this purpose. Ma et al. (2020) compared widely used tools and guided their applicability based on study design (e.g., interventional or observational). For observational studies, the Cochrane Collaboration recommends the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS; Wells et al., 2000, 2003; Lo et al., 2014), which is considered as a valid and reliable method for assessing study quality and risk of bias (Wells et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2024; Li et al., 2008; Deeks et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2021), though it has also been criticised for its subjectivity and lack of clarity (Luchini et al., 2021; Stang, 2010).

Recognising the importance of high-quality research studies in health sciences, this commentary will focus on the version of the NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies (Wells et al., 2000; Hillen et al., 2017). Specifically, we aim to examine its quality assessment criteria, identify sources of subjectivity, and suggest strategies to mitigate them—such as quantifying parameters where feasible—to make the tool more user-friendly, transparent, and effective.

2. Quality Assessment by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

Following PRISMA recommendations (Page et al., 2021), we advise that at least two reviewers independently assess each included study using the NOS.

The maximum attainable score in the NOS depends on the version used, ranging from 9 to 16 points, the latter applying to the extended version for cross-sectional studies (among others: Hillen et al., 2017; Sanderson et al., 2007; Nayebirad et al., 2023; Kien et al., 2022). In this adapted version (Wells et al., 2000; Hillen et al., 2017), 16 points denote the lowest risk of bias and highest methodological quality, while 0 points indicate the highest risk of bias and lowest quality. Following Hillen et al. (2017), studies scoring >75% of the maximum (13–16 points) are considered high quality, those scoring >50% (9–12 points) moderate quality, and those scoring ≤50% (≤8 points) low quality (Gualdi-Russo et al., 2022a; Gualdi-Russo & Zaccagni, 2024; Zaccagni & Gualdi-Russo, 2025).

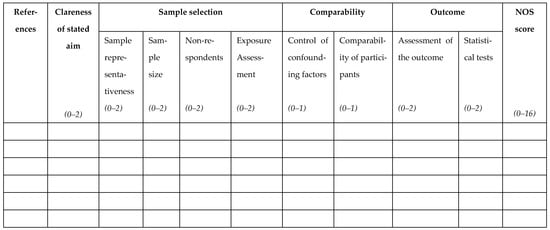

The full methodological evaluation form is provided in the Appendix A (Figure A1). The items contributing to the total score are grouped into four domains: Clearness of the aim (maximum 2 points); Sample selection (maximum 8 points); Comparability (maximum 2 points); Outcome (maximum 4 points). In addition to the detailed descriptions of each domain and subdomain below, together with clarifications and proposed adjustments to the original version, a table of NOS is presented in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

2.1. Clearness of the Aim

This domain assesses the relevance and specificity of the research question. Because this requires personal judgment, we propose reducing subjectivity by setting conventional thresholds for background adequacy, as already applied (Zaccagni & Gualdi-Russo, 2025). Two points are awarded if the Introduction cites ≥10 relevant references, supporting a robust and comprehensive background; 1 point if the background is incomplete (<10 citations); and 0 if any background does not support the research question. The cited literature should range from foundational studies directly relevant to the topic to broader contextual references (Shaheen et al., 2023; Aksnes et al., 2019). By setting a threshold of at least ten references, we have adopted a practical approach to ensure that there is sufficient bibliographic substance for meaningful discussion of the research in progress.

2.2. Sample Selection

This domain includes four subdomains: ‘Representativeness’, ‘Sample size’, ‘Non-response rate’, and ‘Exposure assessment’.

2.2.1. Representativeness

This subdomain represents how well the study sample reflects the target population, as specified in the study aims. The “target population” denotes the entire group sharing a common condition (e.g., eating disorder) or characteristic (e.g., weight loss) of interest. Representativeness can be achieved both when the study includes all individuals or a random sample from a general population (e.g., a national survey on obesity prevalence) and when it includes a targeted sample from a single community, hospital, or department, provided this is consistent with the study’s stated objectives (e.g., assessing weight status in an immigrant community). Two points are given for representative samples obtained through probability sampling methods (Ahmed, 2024).

2.2.2. Sample Size

Sample size adequacy is a critical determinant of study validity. While some authors have suggested conventional thresholds (e.g., ≥100 participants according to Nayebirad et al., 2023), the preferred approach is to justify the sample size through a priori power analysis, which is considered a methodological gold standard in medical research (Winkler et al., 2024). Two points are awarded when the sample size is both justified and adequate; scores of 1 or 0 are assigned if justification is absent or the size is insufficient.

2.2.3. Non-Response Rate

This subdomain assesses the proportion of non-respondents or missing data (e.g., unanswered survey questions). Only if these aspects have been evaluated, the lack is contained to less than 30% of the potential sample according to Hillen et al. (2017) (<10% according to Nayebirad et al., 2023), the characteristics of the respondents (participants) are similar to those of the non-respondents (non-participants) (e.g., healthy people belonging to the same age groups and sex), 2 points are awarded. In summary, to avoid oversimplification based solely on the non-response threshold, it is necessary to consider the comparability between respondents and non-respondents (a key indicator of potential bias), as well as the explicit reporting of non-response analysis (which is necessary for reproducibility and critical appraisal).

Unlike Hillen et al. (2017), who assign 1 point regardless of how many criteria are met, we apply a gradual system: 2 points if three conditions are met (<30% non-response, comparability of respondents and non-respondents, and explicit reporting); 1 point if two conditions are met; 0 otherwise, consistent with prior reviews (Hillen et al., 2017; Nayebirad et al., 2023; Voelker et al., 2017; Bassett-Gunter et al., 2017; Zaccagni & Gualdi-Russo, 2023).

2.2.4. Exposure Assessment

This subdomain evaluates the validity and reliability of the measurement instrument used to assess exposure. Two points are awarded for validated tools (e.g., validated questionnaires, direct measurements) or official records (e.g., national vaccination registries, implant registries, routinely collected health-system databases), which are considered equivalent due to their standardized procedures, documented accuracy, and low risk of misclassification. One point is assigned when the tool is described in detail but not validated; 0 points when it is insufficiently described or lacks validity. As exposure measures can differ between reviews (e.g., vaccination registries, implant registries, direct anthropometric measurements), the tool used should always be clearly described.

2.3. Comparability

This domain includes two subdomains: ‘Control of confounding factors’ and ‘Comparability of groups’.

2.3.1. Control of Confounding Factors

It assesses whether the study accounted for potential confounding variables that might bias the results. Appropriate statistical adjustments—such as multiple regression or ANCOVA—allow examination of one independent variable while controlling for others (e.g., adjusting for age and sex). A score of 1 is awarded if confounding control is present; otherwise, 0 points are assigned.

2.3.2. Comparability of Groups

This subdomain evaluates whether the groups being compared are similar in composition to avoid bias toward overrepresented subgroups. For example, when comparing pre-COVID and COVID-19 body image perceptions, comparability would not be assured if one group were predominantly female and the other predominantly male, given established sex differences in body dissatisfaction and related concerns (Porras-Garcia et al., 2020; Gualdi-Russo et al., 2022b). Comparability is ensured—and 1 point awarded—when the distribution of sex (or age if relevant) is balanced (50% males and 50% females) or differs by no more than 10% (Zaccagni & Gualdi-Russo, 2025); otherwise, the score is 0.

2.4. Outcome

This domain comprises two subdomains: ‘Assessment of the outcome’ and ‘Statistics’.

2.4.1. Assessment of the Outcome

It evaluates the objectivity and reliability of the measurement tools used. A maximum of 2 points is awarded for independent or blinded assessments (e.g., radiographs, medical databases); 1 point for self-reported data; 0 if measurement is not described. It should be emphasised that the review must define the outcome under investigation (e.g., dental caries) and specify which measurement tools are considered independent or blinded (e.g., dental X-rays).

2.4.2. Statistics

This subdomain refers to the appropriateness and transparency of the statistical analyses employed. A score of 2 is awarded if analyses are described in sufficient detail to allow replication (including the statistical tests used, model specifications, assumptions checked, and any data transformations performed), the methods are appropriate, and measures of association (e.g., using odds ratios, correlation coefficients) are reported. One point if two of these conditions are fulfilled (e.g., the statistical test chosen is inappropriate); 0 if only one or none are met.

To improve usability, three illustrative case studies have been included in Table 1. For ease of calculation, we replaced the original ‘star system’ (Wells et al., 2000; Hillen et al., 2017) with a numerical scoring system, as shown in Table 1 and as used in other recent studies (Samal et al., 2024; Wydra et al., 2024; Muhamed et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Example of application of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies on three studies (indicated by A, B, C). Total score: 13–16 points (high quality and low risk of bias), 9–12 points (moderate quality and moderate risk of bias); <9 points (low quality and high risk of bias).

In case of borderline cases, we recommend reducing residual subjectivity as follows: (a) prioritizing explicit operational criteria over subjective judgment; (b) defaulting to the more conservative rating when evidence is ambiguous; and (c) pre-specifying decision rules and consensus procedures in the review protocol. These tips can ensure a more consistent and transparent approach to borderline cases.

3. Discussion

This commentary focused on refinements and practical recommendations for reducing ambiguity and improving inter-observer reliability in the NOS, one of the most widely used tools for evaluating the quality and risk of bias in observational studies (Ma et al., 2020). By clarifying key domains and offering operational guidance, we aim to support more consistent and transparent application of this tool in future research. These suggestions are intended as practical best-practice guidance rather than a formal or prescriptive update of the NOS, providing minor refinements to enhance usability and reliability while leaving room for future empirical evaluation.

One of NOS’s strengths is its compilation speed. A comparison of the NOS tool with ROBINS-I (Sterne et al., 2016) demonstrated that they both appear to offer similar reliability. However, the NOS tool was found to be less time-consuming and less complex (Zhang et al., 2021). In particular, the overall interrater reliability of ROBINS-I is lower than that of NOS. The time taken to assess a single article using ROBINS-I ranges from 7 h initially to 3 h once the researcher is more familiar with the tool, while the assessment time by NOS is on average 30 min (Zhang et al., 2021). Furthermore, Zhang et al. (2021) highlighted that the overly complicated features of ROBINS-I may limit its use. Another significant advantage of the NOS is its adaptability to different research topics. However, this versatility also means that there is much room for interpretation.

In essence, although there are more than 40 other instruments for appraisal of included studies (Lunny et al., 2018, 2024), the NOS is valued for striking a balance between speed, accuracy, and adaptability. Despite its value, its limitations, particularly the subjectivity in scoring of certain items, necessitate clearer guidance. Consistent with best practice, evaluations should be conducted independently by at least two reviewers, with a third resolving disagreements.

Subsequent studies are encouraged to undertake empirical investigation of the operationalisation of the NOS instrument in applied contexts, whilst concomitantly reporting inter-rater agreement metrics to further assess its utility. Refining the NOS items, reducing ambiguity, and providing explicit interpretive guidance are crucial for enhancing the accuracy of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, thereby increasing the reliability of evidence used in clinical decision-making, health promotion, and policy development. Transparent and standardized assessments not only enhance methodological rigor but also preserve NOS as the preferred instrument for meta-research in the health sciences.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/publications14010004/s1, Table S1: Suggestions and explanatory notes for assessing the quality of observational studies in systematic reviews using the adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for evaluating observational studies (Wells et al., 2000; Hillen et al., 2017).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.-R. and L.Z.; methodology, E.G.-R.; resources, E.G.-R. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.-R.; writing—review and editing, E.G.-R. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa scale |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| X-ray | Röntgen radiation |

| COVID-19 | COronaVIrus Disease of 2019 |

| ROBINS-I | Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale collection sheet.

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2024). How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncology Reports, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksnes, D. W., Langfeldt, L., & Wouters, P. (2019). Citations, citation indicators, and research quality: An overview of basic concepts and theories. Sage Open, 9(1), 2158244019829575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett-Gunter, R., McEwan, D., & Kamarhie, A. (2017). Physical activity and body image among men and boys: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 22, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, P. B., Rohrich, R. J., & Chung, K. C. (2011). The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 128(1), 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J. J., Dinnes, J., D’Amico, R., Sowden, A. J., Sakarovitch, C., Song, F., Petticrew, M., & Altman, D. G. (2003). International stroke trial collaborative group; European carotid surgery trial collaborative group. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment, 7(27), 1–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, S., Pourahmadi, M., & Barzkar, F. (2023). What quality assessment tool should I use? A practical guide for systematic reviews authors. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 48(3), 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrye, T., Fatoye, F., Mbada, C., & Hakimi, Z. (2023). A scoping review on quality assessment tools used in systematic reviews and meta-analysis of real-world studies. Rheumatology International, 43(9), 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, G. V. (1976). Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educational Researcher, 5(10), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-Russo, E., Rinaldo, N., Masotti, S., Bramanti, B., & Zaccagni, L. (2022b). Sex differences in body image perception and ideals: Analysis of possible determinants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-Russo, E., Rinaldo, N., & Zaccagni, L. (2022a). Physical activity and body image perception in adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualdi-Russo, E., & Zaccagni, L. (2024). COVID-19 vaccination and predictive factors in immigrants to Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines, 12(4), 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillen, M. A., Medendorp, N. M., Daams, J. G., & Smets, E. M. A. (2017). Patient-driven second opinions in oncology: A systematic review. Oncologist, 22(10), 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kien, N. T., Duc, T. Q., Chi, V. T. Q., Quang, P. N., Tuyen, B. T. T., & Hoa, D. T. P. (2022). Declining trend in anemia prevalence among non-pregnant women of reproductive age in Vietnam over two decades: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. Health Promotion Perspectives, 12(3), 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J., Kim, D. H., & Kwak, S. G. (2024). Comprehensive guidelines for appropriate statistical analysis methods in research. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 77(5), 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Ma, D., Liu, M., Liu, H., Feng, S., Hao, Z., Wu, B., & Zhang, S. (2008). Association between metabolic syndrome and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 25(6), 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K., Mertz, D., & Loeb, M. (2014). Newcastle-Ottawa scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, C., Veronese, N., Nottegar, A., Shin, J. I., Gentile, G., Granziol, U., Soysal, P., Alexinschi, O., Smith, L., & Solmi, M. (2021). Assessing the quality of studies in meta-research: Review/guidelines on the most important quality assessment tools. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 20(1), 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunny, C., Brennan, S. E., McDonald, S., & McKenzie, J. E. (2018). Toward a comprehensive evidence map of overview of systematic review methods: Paper 2-risk of bias assessment; synthesis, presentation and summary of the findings; and assessment of the certainty of the evidence. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunny, C., Kanji, S., Thabet, P., Haidich, A. B., Bougioukas, K. I., & Pieper, D. (2024). Assessing the methodological quality and risk of bias of systematic reviews: Primer for authors of overviews of systematic reviews. BMJ Medicine, 3(1), e000604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. L., Wang, Y. Y., Yang, Z. H., Huang, D., Weng, H., & Zeng, X. T. (2020). Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Military Medical Research, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamed, A. N., Chekole, B., Tafesse, F. E., Dessie, G., Bantie, B., Habtu, B. F., & Shemsu, A. M. (2023). Quality of life among Ethiopian cancer patients: A systematic review of literatures. SAGE Open Nursing, 9, 23779608231202691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayebirad, S., Mohamadi, A., Yousefi-Koma, H., Javadi, M., Farahmand, K., Atef-Yekta, R., Tamartash, Z., Jameie, M., Mohammadzadegan, A. M., & Kavosi, H. (2023). Association of anti-Ro52 autoantibody with interstitial lung disease in autoimmune diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respiratory Research, 10(1), e002076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council). (2019). Guidelines for guidelines: Assessing risk of bias. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/develop/assessing-risk-bias (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Norheim, O. F., Abi-Rached, J. M., Bright, L. K., Bærøe, K., Ferraz, O. L. M., Gloppen, S., & Voorhoeve, A. (2021). Difficult trade-offs in response to COVID-19: The case for open and inclusive decision making. Nature Medicine, 27(1), 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras-Garcia, B., Exposito-Sanz, E., Ferrer-Garcia, M., Castillero-Mimenza, O., & Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J. (2020). Body-related attentional bias among men with high and low muscularity dissatisfaction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, A., Menon, I., Jha, K., Kumar, G., & Singh, A. (2024). Oral health inequalities among geriatric population: A systematic review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 13(10), 4135–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S., Tatt, I. D., & Higgins, J. P. (2007). Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: A systematic review and annotated bibliography. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(3), 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N., Shaheen, A., Ramadan, A., Hefnawy, M. T., Ramadan, A., Ibrahim, I. A., Hassanein, M. E., Ashour, M. E., & Flouty, O. (2023). Appraising systematic reviews: A comprehensive guide to ensuring validity and reliability. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 8, 1268045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, W., Bantle, G., Ebner, C., Blümle, A., Becker, G., Schwarzer, G., & Meerpohl, J. J. (2023). Evaluation of ‘implications for research’ statements in systematic reviews of interventions in advanced cancer patients—A meta-research study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 23(1), 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. (2010). Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology, 25(9), 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A. W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, M., Patnode, C. D., Berkman, N. D., Bass, E. B., Chang, S., Hartling, L., Murad, M. H., Treadwell, J. R., & Kane, R. L. (2017). Assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health care interventions. In Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) 2008. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519366/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Voelker, D. K., Trent, A. P., Reel, J. J., & Gould, D. (2017). Frequency and psychosocial correlates of eating disorder symptomatology in male figure skaters. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. A., Brodsky, L., O’Connell, D., Shea, B., Henry, D., Mayank, S., & Tugwell, P. (2003, October 26–31). An evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS): An assessment tool for evaluating the quality of non-randomized studies. XI Cochrane Colloquium: Evidence, Health Care and Culture, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, G. A., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2000). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp#:~:text=It%20was%20developed%20to%20assess%20the%20quality%20of,quality%20assessments%20in%20the%20interpretation%20of%20meta-analytic%20results (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Whitty, C. J. (2015). What makes an academic paper useful for health policy? BMC Medicine, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, P. W., Horvath, A., & Senorski, E. H. (2024). Calculation of statistical power and sample size. In J. Espregueira-Mendes, J. Karlsson, V. Musahl, & O. R. Ayeni (Eds.), Orthopaedic sports medicine (pp. 1–15). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydra, J., Szlendak-Sauer, K., Zgliczyńska, M., Żeber-Lubecka, N., & Ciebiera, M. (2024). Gut microbiota and oral contraceptive use in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review. Nutrients, 16(19), 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccagni, L., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2023). The impact of sports involvement on body image perception and ideals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccagni, L., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2025). Reduced physical activity and increased weight status in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Children, 12(2), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., Zhang, Y., Kwong, J. S., Zhang, C., Li, S., Sun, F., & Du, L. (2015). The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: A systematic review. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 8(1), 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Huang, L., Wang, D., Ren, P., Hong, Q., & Kang, D. (2021). The ROBINS-I and the NOS had similar reliability but differed in applicability: A random sampling observational studies of systematic reviews/meta-analysis. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 14(2), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.