Abstract

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a devastating complication arising primarily after invasive dentoalveolar procedures in patients treated with antiresorptive, antiangiogenic, or targeted therapies. Although recognized risk factors are established, the distinctive vulnerability of jawbones compared to long bones is not fully understood. This review comprehensively synthesizes recent advances regarding the embryological, anatomical, and physiological disparities that contribute to region-specific susceptibility to MRONJ. Recent evidence suggests that jawbones diverge significantly from long bones in embryonic origin, ossification pathways, vascular architecture, innervation patterns, and regenerative capacities. These differences affect bone metabolism, healing dynamics, response to pharmacologic agents, and local cellular activities, such as enhanced bisphosphonate uptake and specialized microcirculation. Experimental and clinical evidence reveals that mandibular periosteal cells exhibit superior osteogenic and angiogenic potentials, and the jaws respond differently to metabolic challenges, trauma, and medication-induced insults. Furthermore, site-specific pharmacologic and inflammatory interactions, including altered periosteal microcirculation and leukocyte–endothelial interactions, may explain the development of MRONJ, although rare cases of medication-related osteonecrosis have also been reported in long bones. Emerging research demonstrates that immune dysregulation, particularly M1 macrophage polarization with overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13), plays a crucial role in early MRONJ development. Understanding these mechanisms highlights the critical need for region-specific preventive measures and therapeutic strategies targeting the unique biology of jawbones. This comparative perspective offers new translational insights for designing targeted interventions, developing tissue engineering solutions, and improving patient outcomes. Future research should focus on gene expression profiling and cellular responses across skeletal regions to further delineate MRONJ pathogenesis and advance personalized therapies for affected patients.

1. Introduction

Marx RE published the first report on the potential adverse effects of third-generation bisphosphonates (BISs) in 2003 [1]. However, further clinical observation and studies confirmed the role of antiresorptive therapy alone or in combination with immune modulators or antiangiogenic medications in the pathomechanism of this severe disorder, resulting in the change in nomenclature from bisphosphonate- to medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) [2]. Recent studies have expanded the understanding of MRONJ pathogenesis beyond traditional antiresorptive agents, with new evidence linking sclerostin inhibitors like romosozumab to osteonecrosis development [2]. Despite the known drug- or patient-related risk factors potentiating the development of MRONJ (e.g., invasive dentoalveolar procedure, indication and duration of the therapy, or administration route), the exact pathomechanism has not yet been clarified [2]. In general, experimental and clinical research investigated the potential role of local inflammatory or infectious processes, and the cytotoxic or impaired regenerative effects of these drugs [3,4,5,6,7]. Contemporary research has identified immune dysregulation as a central mechanism, with specific focus on altered macrophage polarization and compromised host defense mechanisms in the jawbone environment [8]. Interestingly, special features or skeletal differences explaining the vulnerability of the jawbones, which may also contribute to the development of MRONJ, have not been summarized. This narrative review synthesizes comparative evidence on jawbones and long bones in the context of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (Table 1). The literature search was performed primarily in PubMed/MEDLINE, complemented by manual screening of reference lists. The main search terms included combinations of “jaws”, “mandible”, “maxilla”, “long bones”, “bone regeneration”, “bone metabolism”, “bisphosphonate” (or specific medication), “denosumab”, “antiangiogenic therapy”, “medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw”, “immune dysregulation”, “macrophage polarization”, “periosteum”, and “periosteal microcirculation”, mainly focusing on experimental and clinical studies that directly compared jaws with long bones or provided insight into MRONJ pathogenesis, with a particular emphasis on embryological, anatomical, vascular, neural, cellular, and immunological differences, while case reports and small case series were generally excluded.

Table 1.

Distinctive differences between jawbones and long bones and their relevance to MRONJ susceptibility.

2. Embryological, Anatomical, and Physiological Features of the Jawbones

2.1. Embryological Differences

A crucial difference can be observed between flat and long bones, namely in the process of bone formation. Flat bones, such as craniofacial bones, are characterized by intramembranous ossification. This type of bone formation is typical in bones developing from the neural crest. During intramembranous ossification, the embryonic mesenchyme forms a collagen membrane containing osteochondral progenitor cells. These cells differentiate into osteoblasts, a cell type responsible for bone formation [9]. Osteoblasts form ossification centers, secreting an intercellular matrix creating a scaffold for later occurring mineralization. Calcium is then bound by the matrix, entrapping osteoblasts and leading to their transformation into osteocytes. Osteocytes play an important role in bone remodeling and in mineralization processes locally and systemically [9,10,11]. Hypoxia-induced neovascularization in the central parts contributes to the formation of spongious bone, while externally mesenchymal cells differentiate to periosteal cells [12]. Adjacent cells to this layer are newly forming osteoblasts, which contribute to the development of cortical bone [13]. Recent evidence suggests that intramembranous ossification involves more complex mechanisms than previously understood, with osteochondrogenic progenitors co-expressing Sox9 and Runx2 transcripts within developing intramembranous bones, creating a “chondroid” bone phenotype that combines rapid proliferation with mineralization capacity [14].

Instead, long bones undergo endochondral ossification, a process where embryonic mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into prechondrogenic mesenchymal cells. Through intercellular signaling, cell–cell adhesion is increased, resulting in the formation of condensation. Subsequently, supplying blood vessels regress, creating a hypoxic environment within the central chondrogenic condensate [9]. The hypoxia-induced signaling pathway activates mesenchymal neovascularization [15]. Following the condensation phase, chondrocyte differentiation occurs. Initially, the condensate is surrounded by the perichondrium, which restricts perpendicular growth, allowing only elongation. Later, chondrocytes transition into a hypertrophic state, preparing the bone for the ossification phase [14]. Terminally hypertrophic chondrocytes release signaling molecules, including VEGF, which activates chondroblasts, resulting in channel-like resorptions in the cartilage. Vascularization of these channels occurs, leading to osteoblast activation and the onset of ossification. The perichondrium transforms into periosteum, as osteochondral progenitor cells within the periosteum differentiate into osteoblasts. Blood vessels and osteoblasts of the newly formed periosteum invade the calcified cartilage template [9,16]. Internally, osteoblasts form spongy bone at primary ossification center, while externally, periosteal osteoblasts form compact bone. In summary, load-bearing cartilage is replaced and rebuilt into the bone [17].

It is worth noting that the embryonic origin of the craniofacial skeleton differs from that of the bones of the extremities. While the former originates from the neural crest, the latter are of mesodermal origin. This distinction plays a crucial role in the osteogenic capabilities of the aforementioned bones [14]. Recent lineage tracing studies have revealed that neural crest-derived cells maintain aspects of their pluripotency program through transient reactivation of Oct4 and Nanog, which may contribute to their enhanced regenerative capacity [18]. Osteoblasts derived from the neural crest exhibit higher activation from FGF proliferative signaling compared to those of mesodermal origin [19]. These differences are evident during embryonic stages, resulting in higher osteogenic marker expression, more intense bone mineralization, and larger bone nodule formation in frontal bone-derived osteoblasts. Additionally, these cells may influence nearby cells in a paracrine fashion, promoting cell growth and osteoblast differentiation [20].

2.2. Particular Anatomical Features of the Bones

Bones of the human body are complex, constantly changing structures. The general composition of bones can be divided into an inner collagenous spongious bone and an outer dense, cortical bone, which is covered by the periosteum [21]. The periosteum consists of two different layers, with distinct roles: an outer fibrous layer and an inner more vascular and cellular layer, known as the cambium layer. The outer part of the fibrous layer is a significant contributor to the blood supply of bone and skeletal muscle and contains a rich neural network, while the deeper part of the fibrous layer (fibroelastic layer) is cell-poor, barely vascularized, and responsible for periosteal tendon attachments [13,22]. The inner or cambium layer plays a crucial role in the metabolism of the skeletal structures and new bone formation or growth. This is owing to the high cellularity, which includes mesenchymal progenitor cells, differentiated osteogenic progenitor cells, osteoblasts, and fibroblasts [21,22]. Furthermore, rich peripheral vascular and neural sympathetic networks are presented in the cambium layer. As age advances, the cambium undergoes a progressive decrease in thickness, vessel density, and regenerative potential, eventually becoming indistinguishable from the outer fibrous layer [22,23]. The continuous blood supply of the bones is essential to ensure physiological bone remodeling, metabolism, and regeneration; however, this is one of the most important differences between jawbones and long bones. While the long bones receive their vascular supply from the nutritive arteries, the circulation of the jaws is provided by the mucoperiosteal tissue [24,25,26,27,28]. This fundamental difference in vascular architecture has significant implications for MRONJ pathogenesis, as the jaw’s dependence on mucoperiosteal circulation makes it more vulnerable to the antiangiogenic effects of medications [29]. Moreover, not only the blood supply but also the periosteal innervation and its patterns show certain differences between jawbones and long bones. The mandibular nerve provides the innervation of the lower third of the maxillofacial region, but in a unique way, it contains both afferent and efferent nerve fibers [30]. While neural networks traverse across the surface of the mandible, the tibial periosteum exhibits a longitudinal orientation. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-positive nerve fibers form small networks with individual fine varicose fibers in the mandibular periosteum, whereas larger networks are to be seen at the tibia. These fine fibers are associated with both vascular and nonvascular elements, suggesting specific functions in the mandibular periosteum [31]. During the fetal development, the appearance and density of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-positive nerves (primarily localized to C and Aδ sensory fibers), which play a role in the neurogenic inflammatory processes, also show differences in the mandible compared to the tibia [32]. Moreover, the density of CGRP-positive nerves in the mandible increases toward the mandibular canal, and interestingly, toward the periodontal ligament from periosteum [33]. A comparative in vitro study investigating mandibular and tibial periosteal cells revealed site-specific differences favoring the mandible. Mandibular periosteal cells exhibited superior osteogenic, angiogenic, and endogenous potential, as well as enhanced activation of FGF signaling, compared to tibial periosteal cells, while the calvarial periosteum has lower osteogenic potential than the tibial periosteum [20,34,35,36]. Recent studies have confirmed these findings and demonstrated that jawbone periosteum-derived cells (jb-PDCs) maintain high osteogenic and chondrogenic potential, with enhanced expression of bone regeneration markers compared to long-bone periosteal cells [37].

Cadaver studies also uncovered structural disparities among bony tissues. Specifically, the trabecular structure of the mandible exhibited plate-like formations, whereas a combination of plate- and rod-like structures was evident in the tibia, and only rod-like trabecular structures were presented in the ilium. In addition, significant differences in bone mineral density and bone volume/total volume were observed in the lower jaw compared to the tibia or ilium [38]. These parameters also showed variations among anatomical regions of the mandible or jawbones and are influenced by tooth loss (dentulous or edentulous jaw). In the edentulous mandible, the trabecular structure transitioned from plate-like to rod-like patterns [38,39,40,41,42]. Furthermore, it has been found that the microcirculation of the jaw features a higher number of anastomoses and a greater impact of the centromedullary circulation as opposed to the long bones [43]. This difference in vascular structure may influence how the jaw responds to injuries and treatments, contributing to its unique healing and regenerative properties.

In addition to structural differences, bones exhibit distinct signaling properties and cellular activities depending on their origin [44]. Studies have shown that bone marrow stem cells or osteoblasts of the mandible possess a remarkable capacity to induce bone formation both in vitro and in vivo, as well as a higher angiogenic potential compared to long bones, although the expression of the VEGF gene may alter over time [45,46,47,48]. These characteristics may contribute to a higher degree of healing capacity of the mandible after fracture compared to other anatomical locations [47,49,50,51]. Moreover, cartilage-specific proteins or genes responsible for angiogenesis and ossification process showed site specificity, where angiogenic potential was higher in the mandibular condylar cartilage [46,52].

2.3. Bone Modeling and Remodeling: Cellular and Intercellular Characteristics

Modeling occurs continuously during skeletal development, greatly reducing and ceasing entirely after skeletal maturity, while remodeling takes place throughout life. Modeling leads to changes in bone shape and size, whereas remodeling generally maintains them. These processes involve two major types of bone cells: the osteoclasts and the osteoblasts [53,54]. Their very special communication, known as osteoclast–osteoblast coupling, is responsible for maintaining bone homeostasis, the balance between bone resorption and formation [54,55]. This complex intercellular communication is regulated by various factors, including cytokines, growth factors, hormones, or cell surface receptors [56]. One of the key signaling pathways involved in osteoclast–osteoblast coupling is the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL)-RANK pathway. RANKL, produced by osteoblasts and other bone marrow stromal cells, binds to its receptor RANK on osteoclast precursor cells, leading to their differentiation into mature osteoclasts and their activation for bone resorption [57]. Conversely, osteoblasts secrete osteoprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor for RANKL, which competitively inhibits the binding of RANKL to RANK, thereby suppressing osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. This delicate balance between RANKL and OPG regulates the formation and activity of osteoclasts in response to various physiological and pathological stimuli [58]. Additionally, a mechanism in the opposite direction can be observed, where osteoclast-mediated processes (e.g., TGFβ1 and SMAD3 signaling, or sphingosine-1-phosphate) promote osteoblastogenesis [59]. This cross-talk between osteoclasts and osteoblasts is a fundamental process in bone biology that regulates bone remodeling and maintains skeletal integrity. These fine mechanisms show distinct differences between the jaws and long bones, as the maxillofacial region has unique characteristics such as alveolar bone, tooth eruption, and orthodontic tooth movement. Comprehensive studies investigating the bone marrow of the mandible and long bones, both in vitro and in vivo, have demonstrated a diverse osteoclastogenic and osteogenic capacity in the mandible compared to the long bones [45,60,61]. For instance, certain osteoclast genes (e.g., Nfatc1, Dc-stamp, Ctsk, or Rank) are upregulated in mandibular-derived osteoclast precursors [62]. Additionally, proliferation, alkaline phosphatase activity, and the expression of genes related to bone regeneration, bone growth, extracellular matrix mineralization, and bone remodeling (e.g., osteopontin, Msx) show differences and higher activity in the mandible compared to the long bones [47]. These mechanisms may contribute to shorter bone healing times after fracture or bone augmentation in the mandible compared to the long bones of the extremities [47,63,64].

The role of innervation in bone metabolism is a relatively novel aspect of research. Experimental and clinical studies have revealed the contribution of sensory and sympathetic neuronal systems in bone development, growth, and remodeling [65,66,67]. These nerve fibers, which are primary afferent sensory and sympathetic fibers frequently associated with blood vessels, are present mostly in the periosteum, and less so in bone marrow and mineralized bone [66]. Several neuromediators, such as vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide, pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptides, neuropeptide Y, substance P, noradrenaline, serotonin, and glutamate, are involved in the regulation of bone cell activity, bone development, and regeneration [66,68,69,70]. Generally, CGRP downregulates osteoclastogenesis and osteoclastic activity by blocking the RANK/RANKL pathway, while substance P has the opposite effect. Both proteins, however, upregulate osteoblast activity and new bone formation, thereby accelerating fracture healing [71]. Interestingly, experimental sympathectomy and sensory denervation do not appear to alter normal bone growth but are involved in local remodeling. Sympathectomy significantly increased the number of osteoclasts on the mandibular bone surface, while sensory denervation resulted in the opposite effect [31,72,73,74].

3. Variances in the Skeletal Manifestation of Medical Conditions

Several studies have shown that various diseases, such as osteoporosis and fracture healing, can affect bones differently, with a more rapid onset of osteoradionecrosis often observed in the mandible (Table 1) [75,76,77,78,79]. Factors, such as continuous mechanical loading of the mandible during mastication, unique anatomical and morphological characteristics, and the distinct embryological origin of the jaws and long bones, may contribute to this phenomenon [76,80,81,82]. Dysregulation of osteoclast–osteoblast coupling is implicated in various bone disorders, including osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Paget’s disease. Imbalances in bone resorption and formation disrupt skeletal homeostasis, leading to bone loss, fractures, and compromised bone healing.

3.1. Effects of Nutrition

Malnutrition affects the function and recovery of every organ system, including bones [83]. In animal models, mandibular alveolar bone was found to be less sensitive to protein undernutrition [76]. Regarding low calcium intake, studies are controversial, showing either no effects or inhibiting mandibular growth [84,85,86,87]. Related to calcium homeostasis, the anabolic role of 1,25(OH)2D did not differ in the investigated anatomical regions (alveolar bone of the mandible and long bones). However, parathyroid hormone exerts an anabolic effect predominantly in long bones, contributing to site-specific differences in PTH receptor and IGF1 expression [88]. An experimental study found that diabetes significantly affects bone structure, with the tibia experiencing the most severe bone loss. In contrast, the femur, mandible, and spine showed less immediate bone loss, with significant decreases observed later. By the third month, the femur, mandible, and spine experienced significant reductions in bone volume/trabecular volume [89].

3.2. Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone mineral density and bone mass, or altered structure and strength of bone, leading to an increased risk of skeletal related events, namely bone fractures. Several risk factors may contribute to the development of osteoporosis or increase its likelihood (e.g., sex, age, body size, race, family history, altered hormonal state, diet, co-morbidities, medications, or life-style) [90,91].

Most experimental studies have been conducted using animal models of osteoporosis induced by steroid treatment or estrogen deficiency. The results in this area are somewhat contradictory: some studies have found significant effects of osteoporosis on the mandibular bone features, while others have reported no or negligible differences between the jaws and long bones in certain parameters investigated [76,77,92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. Oral functions, such as mastication, may provide a protective effect against osteoporosis-related skeletal changes in the jaws [99,100]. Although patients with osteoporosis showed radiologically detectable mandibular changes, this process did not correlate with an increased tendency for tooth loss [101,102,103].

The deteriorative effects of osteoporosis on bone healing are well-known, but the literature also contains contradictory results [104]. Some animal models have shown that intramembranous ossification is more sensitive to osteoporosis, while other studies have not demonstrated a significant effect on the osseointegration of titanium implants in the mandible compared to the long bone [105,106,107]. Human studies have not proven a correlation between osteoporosis and mandibular healing or the loss of dental implants [108,109].

3.3. Fracture and Bone Healing

Endochondral and intramembranous fracture healing processes are regulated by a complex interplay of signaling molecules, such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [110]. These factors ensure the proper recruitment, differentiation, and function of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, which are essential for bone formation and remodeling [111]. The role of periosteal integrity in bone physiology is well-established, extending beyond the maintenance of vascular supply to include the active regulation of bone metabolism and regeneration [112]. Successful fracture healing requires the regeneration of both periosteal and endosteal circulations [113]. Periosteal damage can lead to disrupted bone healing, resulting in delayed union or pseudoarthrosis formation [114,115,116]. Clinical and experimental observations indicate that certain long-term medical treatment or medical conditions can impair angiogenesis in the periosteal tissues, leading to further complications [117,118,119].

Endochondral and intramembranous fracture healing are the two primary pathways through which bone repairs itself after an injury. Both processes are crucial for restoring bone integrity, but they differ in their mechanisms and the types of fractures they primarily address [111]. Endochondral fracture healing, typically seen in long bones, involves the formation of a cartilage callus as an intermediary step. When a fracture occurs, an (1) initial inflammatory phase sets in, characterized by the formation of a hematoma at the fracture site. Inflammatory cells release cytokines and growth factors, recruiting mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to the injury site. This is followed by (2) cartilage formation with early endochondral ossification and a periosteal response, during which MSCs differentiate into chondrocytes, forming a soft callus made of cartilage. This soft callus stabilizes the fracture and provides a scaffold for new bone formation. As healing progresses, (3) cartilage resorption and primary bone formation begin, and the cartilage undergoes endochondral ossification, where it is gradually replaced by woven bone. Blood vessels invade the area, bringing osteoprogenitor cells that further aid bone deposition. Finally, (4) secondary bone formation and remodeling occur, where the woven bone is remodeled into lamellar bone, restoring the original structure and strength of the bone [111,120,121].

In contrast, intramembranous fracture healing occurs primarily in flat bones and does not involve a cartilage intermediate [111]. Instead, it begins directly with the formation of bone tissue from mesenchymal cells. After a fracture, the inflammatory response similarly recruits MSCs to the fracture site. However, these cells differentiate directly into osteoblasts. Periosteum-derived stem cells, which are crucial for bone regeneration, show the highest osteogenic potential in the mandible. In contrast, tibial periosteum and bone marrow stem cells are more effective in chondrogenesis [49,51,122]. Osteoblasts begin secreting bone matrix, which mineralizes to form woven bone. Throughout this process, a rich blood supply is maintained, providing the necessary nutrients and cells for bone formation. The woven bone is then remodeled into lamellar bone, ensuring the restored bone is strong and well-structured [111]. Recent evidence demonstrates that jawbone defects can be repaired through endochondral ossification when appropriate conditions are created, with periosteal-derived cell spheroids maintaining chondrogenic potential and contributing to cartilaginous callus formation [123]. The maxillofacial region is unique in that wound and bone healing occur in a somewhat contaminated environment. Despite this, perioperative antibiotic therapy is generally not recommended following tooth extraction, yet gingival and alveolar bone healing still proceed effectively.

3.4. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: Characteristics of the Bone and Medication Interaction

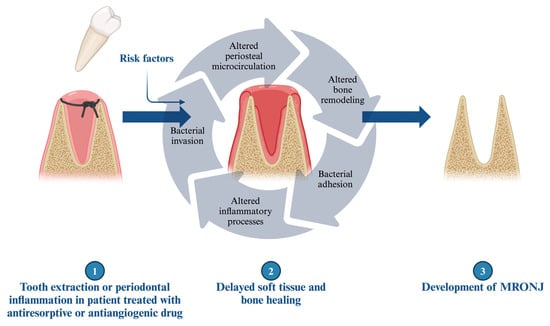

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a severe complication associated with antiresorptive (such as bisphosphonate and denosumab) or antiangiogenic treatment, with an unclear pathomechanism (Figure 1) [1,2]. These reactions do not typically occur in the bones of the appendicular skeleton [124,125]. Various factors may contribute to or increase the risk of the development of MRONJ, including the administration route, the duration and indication of the therapy, co-morbidities, concomitant drug use, and genetic factors [2,126,127,128,129,130]. However, the primary trigger factor for the development of MRONJ, aside from the aforementioned treatment, is the injury to the alveolar bone, particularly during dentoalveolar procedures [131]. MRONJ predominantly occurs in the molar and premolar regions and is more common in the mandible [132]. This severe condition can develop several years after treatment, which may be explained by the long half-lives of bisphosphonates (BISs) [130]. Recent clinical studies have distinguished between osteoporotic and oncologic MRONJ, revealing that oncologic patients exhibit rapid disease onset, fewer purulent signs, larger sequestra, and lower cure rates compared to osteoporotic patients, suggesting distinct pathophysiological mechanisms between these populations [133].

Figure 1.

The underlying mechanism in the development of MRONJ.

As previously described, the effects of BIS treatment vary depending on anatomical localization (Table 1). An experimental study investigated the effects of chronic BIS treatment on morphometric indices related to bone quantity and structure. The analysis revealed that quantity-related indices (bone volume/trabecular volume and trabecular thickness) were more impacted in the mandible, while structure-related indices (trabecular pattern factor and trabecular number) were more significant for the femoral epiphysis and metaphysis [134,135]. Another animal study showed that BIS treatment resulted in significant structural changes in the cortical bone channel network of the tibia, with no differences observed in the mandible [136]. Additionally, BIS treatment caused over-mineralization, deterioration in bone mineral quality, decreased proteoglycan content, and deterioration in collagen structural integrity in newly formed bone in the mandible. Despite these effects, mandibular growth was not affected. These adverse effects were not observed in the long bones [137,138]. Additionally, Vieira et al. demonstrated that alendronate may increase intramembranous ossification in the maxillary bone [139].

The regional uptake of BIS is higher in the mandible compared to other skeletal regions, potentially impairing regenerative processes and contributing to the pathophysiology of MRONJ [140]. This preferential accumulation in jawbones is attributed to the higher bone turnover rates in alveolar regions, where bisphosphonates bind to hydroxyapatite crystals and remain sequestered for extended periods [141]. From a functional perspective, bone regeneration relies not only on the activity of the osteoblasts and osteoclasts, but also on the blood supply and angiogenesis. BISs influence all of these processes by primarily inhibiting osteoclast recruitment to the bone surface and shortening their lifespan, either directly or indirectly through the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK)/receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin pathway [142,143]. BIS decreases RANKL levels in the mandible while having the opposite effect in the tibia [6]. Consequently, it can delay bone healing after maxillofacial fracture and decrease bone formation and vascularity in extraction sockets [144,145,146,147]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the antiangiogenic effects of BISs both in vitro and in vivo [144,148,149]. Zoledronic acid, a potent third-generation bisphosphonate, has been shown to inhibit endothelial cell proliferation with IC50 values of 4.1–6.9 μM for various growth factors and to reduce vessel sprouting in multiple angiogenesis assays [148]. Moreover, zoledronate-treated rats exhibited thicker and less connected blood vessels in the alveolar bone of the mandible after tooth extraction [150]. BISs bound to the bone surface can inhibit the growth and proliferation of stem/osteoprogenitor cells in the periosteum. They also exert toxic effects on various cell types, including fibroblasts, osteoblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells [23,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160]. As mentioned above, osteoblasts exhibit different functional activities at various locations under physiological conditions, which are critically influenced by BIS treatment [161]. These negative effects can be further exacerbated by the critically high concentration of BIS in the mandible [140,155,162]. These findings may explain their contribution to the lower bone turnover in the mandible and to the development of MRONJ [163,164,165]. Contrarily, in a recently published study, the viability of mesenchymal stem cells from the mandibular or tibial periosteum and bone marrow was not influenced by BIS treatment [166]. Sensory denervation, which plays a distinct role in bone formation as mentioned above, via inferior alveolar nerve transection also facilitated the occurrence of MRONJ in a rat model [71]. Recent mechanistic insights have revealed that MRONJ pathogenesis involves complex immune dysregulation. M1 macrophage polarization with overexpression of MMP-13 plays a crucial role in early MRONJ development, leading to collagen network disruption around affected bone areas. This inflammatory cascade is triggered by decreased defense capacities of the jawbone due to antiresorptive-drug-induced immune suppression and osteoclast inhibition [167].

Special BIS-associated inflammatory changes can be observed in the bone and periosteal microcirculation of the head neck region, and were not seen in long bones [3,7,146,168]. Enhanced leukocyte–endothelial interactions require increased expression of adhesion molecules on the cell surface [169]. However, BISs do not appear to influence the expression of the neutrophil-derived adhesion molecule CD11b, which is responsible for leukocyte adherence. This suggests that endothelial changes may be responsible for the enhanced leukocyte–endothelial interaction localized to the mandibular periosteum [7].

Furthermore, BIS treatment has site-specific impacts during the early healing stages of fractures, delaying callus formation, cartilage development, and bone remodeling specifically in the mandible in a dose-dependent manner [75,147]. The functional activity of osteocytes also differs between the mandible and tibia, with the adverse effects of BISs on bone healing being confined to the jaw, although more bone formation was observed in BIS-treated ovariectomized rats [6,170,171]. Even a single systemic dose of BIS leads to site-specific differences in gene regulation related to tissue healing and bone regeneration. In the tibia, BIS treatment increased proinflammatory cytokines, as well as osteogenic and angiogenic gene activity, whereas in the mandible, the expression of genes related to osteogenesis, inflammation, angiogenesis, bone remodeling, and apoptosis was reduced [172]. BIS pretreatment inhibited the osseointegration of allografts, affecting osteogenesis and resulting in a gap between the allograft and bone surface [173]. Atypical femoral fractures related to chronic BIS treatment have also been documented. However, local use of BIS increased callus volume in femoral fracture healing [174,175,176]. Similar beneficial effects were demonstrated in animal models focusing on osseointegration. Regardless of the local or systemic use of BIS, a single-dose injection promoted the osseointegration of titanium implants in long bones in osteoporotic rats [172,177]. Contemporary understanding suggests that MRONJ development follows an “inside–outside” hypothesis, where persistent bone microdamage from chewing combined with suppressed bone remodeling leads to bone death, and an “outside–inside” hypothesis, where medication-induced immune suppression compromises the oral mucosa’s ability to fight pathogens that eventually spread to underlying bone. The jawbones’ thin mucoperiosteal covering provides minimal protection compared to the thick skin and muscle layers protecting other bones [178].

In summary, multiple theories exist regarding the pathomechanism of MRONJ, yet they all converge on a common factor: altered regenerative processes. One of the most plausible approaches involves changes in the periosteal microvasculature. Medications and related inflammatory reactions can alter the periosteal microcirculation, making the jaws more vulnerable and reducing their regenerative potential. BISs enhance bacterial adhesion (e.g., Pseudomonas, Staphylococci) and biofilm formation on bone hydroxyapatite, exacerbating the risk of infection [179]. In this compromised environment, tooth extraction, impaired regeneration, and delayed wound healing promote further bacterial contamination of the extraction socket or alveolar bone through gingival injuries [180,181]. Recent studies emphasized the prominent role of local infection, and a correlation was found between bacterial colonization (e.g., Porphyromonas, Lactobacillus, Tannerella, Prevotella, Actinomyces, Treponema, Streptococcus or Fusobacterium) and the development of MRONJ [182,183]. Emerging therapeutic approaches focus on modulating the immune response, with studies showing that interventions promoting M2 macrophage polarization (such as rosiglitazone treatment) or inhibiting M1 macrophage activation and pyroptosis by blocking the NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β axis can reduce MRONJ burden by reversing the pathological M1/M2 polarization ratio and decreasing both osteonecrosis percentage and bone exposure [184,185]. Furthermore, M1-M2 macrophage polarization status may correlate with the clinical stage of MRONJ [186]. Comprehensively delineating the mechanisms and extent of macrophage involvement in MRONJ pathogenesis will advance our understanding of disease biology and may uncover intrinsic targets for therapeutic intervention.

Regarding skeletal related events, antiresorptive or antiangiogenic treatments have improved the survival rates and the quality of life of the patients. However, despite its low prevalence, MRONJ and aforementioned medications significantly impair the quality of life of the patients by complicating complex dental rehabilitation, including preprosthetic surgeries and dental implantation.

3.5. Future Directions and Conclusions

Comparative studies on gene expression profiles, cellular behaviors, and responses to different stimuli across skeletal regions will further elucidate and enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Recent advances in single-cell sequencing and lineage tracing techniques promise deeper insights into the molecular characteristics of neural crest-derived versus mesoderm-derived bone cells and their differential responses to medications [187].

However, several critical gaps remain. The functional integrity of jaw periosteal microcirculation and neurovascular coupling is another underexplored area. Advanced imaging modalities (e.g., perfusion MRi) could clarify how antiangiogenic and antiresorptive agents compromise periosteal microcirculation and neural regulation, which is key to bone turnover and repair. Similarly, detailed characterization of the immune microenvironment in the jaw during MRONJ onset is still needed. Moreover, the interaction between oral bacteria and drug-altered bone tissue awaits multi-omics characterization. Integrated microbiome, transcriptomics, and metabolomics studies in MRONJ lesions would reveal novel insights into microbial influences driving persistent inflammation and impaired healing.

This accumulated knowledge will support advances in tissue engineering, including biomimetic scaffolds and controlled growth factor delivery systems designed to recapitulate jaw-specific molecular environments. Emerging bio-integrated scaffolds that generate localized hypoxic microenvironments show promise for promoting endochondral ossification and enhanced healing of large bone defects [188]. Understanding the distinct molecular and cellular mechanisms in different skeletal regions can enable personalized medical approaches, optimizing therapeutic strategies based on mandibular or long-bone requirements. Future therapeutic strategies should consider the unique embryonic origins of jawbones by preferentially using neural crest-derived progenitors for mandibular repair over mesoderm-derived cells [189].

Additionally, these insights may contribute to the development of effective preventive and therapeutic approaches for patients with MRONJ. Promising avenues include immune modulation therapies targeting macrophage polarization, exosome-based delivery of bioactive molecules, and combination approaches addressing both the vascular and immune components of MRONJ pathogenesis [190].

Addressing these specific research gaps through focused mechanistic and translational studies will enable region-specific interventions, ultimately improving the clinical management and quality of life of patients at risk of or affected by MRONJ.

Author Contributions

B.P.: literature review, writing the manuscript. J.P.: supervision, finalizing the manuscript. Á.J.: supervision, writing and finalizing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Aghaloo, T.; Carlson, E.R.; Ward, B.B.; Kademani, D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2022 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 920–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senel, F.C.; Kadioglu Duman, M.; Muci, E.; Cankaya, M.; Pampu, A.A.; Ersoz, S.; Gunhan, O. Jaw bone changes in rats after treatment with zoledronate and pamidronate. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 109, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawardi, H.; Giro, G.; Kajiya, M.; Ohta, K.; Almazrooa, S.; Alshwaimi, E.; Woo, S.B.; Nishimura, I.; Kawai, T. A role of oral bacteria in bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Pushalkar, S.; Estilo, C.; Wong, C.; Farooki, A.; Fornier, M.; Bohle, G.; Huryn, J.; Li, Y.; Doty, S.; et al. Molecular profiling of oral microbiota in jawbone samples of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Dis. 2012, 18, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankaya, M.; Cizmeci Senel, F.; Kadioglu Duman, M.; Muci, E.; Dayisoylu, E.H.; Balaban, F. The effects of chronic zoledronate usage on the jaw and long bones evaluated using RANKL and osteoprotegerin levels in an animal model. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 42, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovszky, A.; Szabo, A.; Varga, R.; Garab, D.; Boros, M.; Mester, C.; Beretka, N.; Zombori, T.; Wiesmann, H.P.; Bernhardt, R.; et al. Periosteal microcirculatory reactions in a zoledronate-induced osteonecrosis model of the jaw in rats. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröltzsch, M. Editorial: Immunological processes in maxillofacial bone pathology. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1394835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, A.D.; Olsen, B.R. Bone development. Bone 2015, 80, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffler, M.B.; Kennedy, O.D. Osteocyte signaling in bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2012, 10, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, S.L.; Prideaux, M.; Bonewald, L.F. The osteocyte: An endocrine cell… and more. Endocr. Rev. 2013, 34, 658–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Spiegelaere, W.; Cornillie, P.; Casteleyn, C.; Burvenich, C.; Van den Broeck, W. Detection of hypoxia inducible factors and angiogenic growth factors during foetal endochondral and intramembranous ossification. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2010, 39, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Fennessy, P. The periosteum: A simple tissue with many faces, with special reference to the antler-lineage periostea. Biol. Direct 2021, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, G.L.; Zein, M.R.; Allen, S.; Francis-West, P. Making and shaping endochondral and intramembranous bones. Dev. Dyn. 2021, 250, 414–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Mao, X.; Yu, Q.; Yu, D. Effect of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway on hypoxia-induced proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahney, C.S.; Hu, D.P.; Miclau, T., 3rd; Marcucio, R.S. The multifaceted role of the vasculature in endochondral fracture repair. Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Behonick, D.J.; Werb, Z. Matrix remodeling during endochondral ossification. Trends Cell Biol. 2004, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, P.; Crump, J.G. Reassessing the embryonic origin and potential of craniofacial ectomesenchyme. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 138, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Douarin, N.M.; Creuzet, S.; Couly, G.; Dupin, E. Neural crest cell plasticity and its limits. Development 2004, 131, 4637–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Quarto, N.; Longaker, M.T. Activation of FGF signaling mediates proliferative and osteogenic differences between neural crest derived frontal and mesoderm parietal derived bone. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwalter, J.A.; Cooper, R.R. Bone structure and function. Instr. Course Lect. 1987, 36, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dwek, J.R. The periosteum: What is it, where is it, and what mimics it in its absence? Skelet. Radiol. 2010, 39, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.R.; Hock, J.M.; Burr, D.B. Periosteum: Biology, regulation, and response to osteoporosis therapies. Bone 2004, 35, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, G. Bone as a tissue. In Orthopedics: The Principles and Practice of Musculoskeletal Surgery; Hughes, S.P.F., Benson, M.A., Colton, C.L., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.O.; Soultanis, K.; Soucacos, P.N. Vascular anatomy and microcirculation of skeletal zones vulnerable to osteonecrosis: Vascularization of the femoral head. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 35, 285–291, viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, D.M. Vascular pathology and osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2007, 46, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huelke, D.F.; Castelli, W.A. The blood supply of the rat mandible. Anat. Rec. 1965, 153, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, J.; Shannon, J.; Modelevsky, S.; Grippo, A.A. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 2350–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.P.; Fischer, H.; Aydin, S.; Steffen, C.; Schmidt-Bleek, K.; Rendenbach, C. Uncovering the unique characteristics of the mandible to improve clinical approaches to mandibular regeneration. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1152301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodella, L.F.; Buffoli, B.; Labanca, M.; Rezzani, R. A review of the mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies and their clinical relevance. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.L.; Elde, R. Distribution of CGRP-, VIP-, D beta H-, SP-, and NPY-immunoreactive nerves in the periosteum of the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1991, 264, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Miwa, Y.; Sato, I. Expression of CGRP, vasculogenesis and osteogenesis associated mRNAs in the developing mouse mandible and tibia. Eur. J. Histochem. 2017, 61, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Tanaka, K.; Ambe, K.; Kawaai, H.; Yamazaki, S. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Nerve Distribution in Mandible of Rats. Anesth. Prog. 2019, 66, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhuo, J.; Wang, Q.; Xu, X.; He, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Luo, K.; Chen, Y. Site-specific periosteal cells with distinct osteogenic and angiogenic characteristics. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 7437–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddstromer, L. The osteogenic capacity of tubular and membranous bone periosteum. A qualitative and quantitative experimental study in growing rabbits. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1978, 12, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkay, U.; Tokat, C.; Helvaci, E.; Ozek, C.; Zekioglu, O.; Onat, T.; Songur, E. Osteogenic capacities of tibial and cranial periosteum: A biochemical and histologic study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2008, 19, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Jin, S.; Sun, W.; Ji, W.; Chen, Z. Jawbone periosteum-derived cells with high osteogenic potential controlled by R-spondin 3. Faseb J. 2024, 38, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, E.; Mayahara, M.; Inoue, S.; Miyamoto, M.; Funae, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsuki-Fukushima, M.; Nakamura, M. Trabecular structure and composition analysis of human autogenous bone donor sites using micro-computed tomography. J. Oral Biosci. 2021, 63, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamigaki, Y.; Sato, I.; Yosue, T. Histological and radiographic study of human edentulous and dentulous maxilla. Anat. Sci. Int. 2017, 92, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozoglu, U.; Cakur, B. Evaluation of the morphological changes in the mandible for dentate and totally edentate elderly population using cone-beam computed tomography. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2014, 36, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, D.A.; Arosio, P.; Pagnutti, S.; Vinci, R.; Gherlone, E.F. Distribution of Trabecular Bone Density in the Maxilla and Mandible. Implant. Dent. 2019, 28, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funae, T.; Imamura, E.; Mayahara, M.; Inoue, S.; Nakamura, M. Comparison of mandibular trabecular bone structure and composition between dentulous and edentulous human mandibles. J. Dent. Maxillofac. Res. 2020, 3, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanavaz, M. Anatomy and histophysiology of the periosteum: Quantification of the periosteal blood supply to the adjacent bone with 85Sr and gamma spectrometry. J. Oral Implantol. 1995, 21, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, U.I.; Kawaguchi, H.; Takato, T.; Nakamura, K. Distinct osteogenic mechanisms of bones of distinct origins. J. Orthop. Sci. 2004, 9, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaloo, T.L.; Chaichanasakul, T.; Bezouglaia, O.; Kang, B.; Franco, R.; Dry, S.M.; Atti, E.; Tetradis, S. Osteogenic potential of mandibular vs. long-bone marrow stromal cells. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; He, M.; Luo, K.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X. Osteogenic and angiogenic characterization of mandible and femur osteoblasts. J. Mol. Histol. 2019, 50, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichert, J.C.; Gohlke, J.; Friis, T.E.; Quent, V.M.; Hutmacher, D.W. Mesodermal and neural crest derived ovine tibial and mandibular osteoblasts display distinct molecular differences. Gene 2013, 525, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.; Bertolai, R.; Ambrosini, S.; Sarchielli, E.; Vannelli, G.B.; Sgambati, E. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human fetal skeletal site-specific tissues: Mandible versus femur. Acta. Histochem. 2015, 117, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, E.; Pinholt, E.M.; Talsnes, O.; Larsen, T.B.; Kirkeby, O.J. Bone formation in cranial, mandibular, tibial and iliac bone grafts in rats. J. Craniofac. Surg. 1995, 6, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.L.; Kung, L.; Jones, C.; Casap, N. Induced osteogenesis by periosteal distraction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 60, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, T.; Kagawa, T.; Fukunaga, J.; Mizukawa, N.; Sugahara, T.; Yamamoto, T. Evaluation of osteogenic/chondrogenic cellular proliferation and differentiation in the xenogeneic periosteal graft. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2002, 48, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watahiki, J.; Yamaguchi, T.; Enomoto, A.; Irie, T.; Yoshie, K.; Tachikawa, T.; Maki, K. Identification of differentially expressed genes in mandibular condylar and tibial growth cartilages using laser microdissection and fluorescent differential display: Chondromodulin-I (ChM-1) and tenomodulin (TeM) are differentially expressed in mandibular condylar and other growth cartilages. Bone 2008, 42, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandiraju, D.; Ahmed, I. Human skeletal physiology and factors affecting its modeling and remodeling. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, N.A.; Martin, T.J. Coupling Signals between the Osteoclast and Osteoblast: How are Messages Transmitted between These Temporary Visitors to the Bone Surface? Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Duan, N.; Zhu, G.; Schwarz, E.M.; Xie, C. Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect. Tissue Res. 2018, 59, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daponte, V.; Henke, K.; Drissi, H. Current perspectives on the multiple roles of osteoclasts: Mechanisms of osteoclast-osteoblast communication and potential clinical implications. Elife 2024, 13, e95083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takegahara, N.; Kim, H.; Choi, Y. RANKL biology. Bone 2022, 159, 116353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Shima, N.; Nakagawa, N.; Mochizuki, S.I.; Yano, K.; Fujise, N.; Sato, Y.; Goto, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kuriyama, M.; et al. Identity of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) and osteoprotegerin (OPG): A mechanism by which OPG/OCIF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqeer, A.; Wang, M.; Alam, G.; Padhiar, A.A.; Zheng, D.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, I.S.; Zhou, G.; van den Beucken, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Cleaved SPP1-rich extracellular vesicles from osteoclasts promote bone regeneration via TGFbeta1/SMAD3 signaling. Biomaterials 2023, 303, 122367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Faloni, A.P.; Schoenmaker, T.; Azari, A.; Katchburian, E.; Cerri, P.S.; de Vries, T.J.; Everts, V. Jaw and long bone marrows have a different osteoclastogenic potential. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2011, 88, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichanasakul, T.; Kang, B.; Bezouglaia, O.; Aghaloo, T.L.; Tetradis, S. Diverse osteoclastogenesis of bone marrow from mandible versus long bone. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Park, S.Y.; Bradley, E.W.; Mansky, K.; Tasca, A. Mouse mandibular-derived osteoclast progenitors have differences in intrinsic properties compared with femoral-derived progenitors. JBMR Plus 2024, 8, ziae029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, C.; Protzman, R. Outcomes of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis for metaphyseal distal tibia fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2010, 24, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermund, N.U.; Hillerup, S.; Kofod, T.; Schwartz, O.; Andreasen, J.O. Effect of early or delayed treatment upon healing of mandibular fractures: A systematic literature review. Dent. Traumatol. 2008, 24, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenu, C. Glutamatergic innervation in bone. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002, 58, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenu, C. Role of innervation in the control of bone remodeling. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact. 2004, 4, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Meyers, C.A.; Lee, S.; Qin, Q.; James, A.W. Interaction between the nervous and skeletal systems. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 976736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konttinen, Y.; Imai, S.; Suda, A. Neuropeptides and the puzzle of bone remodeling: State of the art. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1996, 67, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, E.L.; Elde, R.P.; Rysavy, J.A.; Einzig, S.; Gebhard, R.L. Innervation of periosteum and bone by sympathetic vasoactive intestinal peptide-containing nerve fibers. Science 1986, 232, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.; Lee, S.; Patel, N.; Walden, K.; Gomez-Salazar, M.; Levi, B.; James, A.W. Neurovascular coupling in bone regeneration. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hua, Z.; Li, J.; Fu, G.; Wu, Q. Sensory denervation increases potential of bisphosphonates to induce osteonecrosis via disproportionate expression of calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1487, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherruau, M.; Morvan, F.O.; Schirar, A.; Saffar, J.L. Chemical sympathectomy-induced changes in TH-, VIP-, and CGRP-immunoreactive fibers in the rat mandible periosteum: Influence on bone resorption. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 194, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, C.; Mauprivez, C.; Hay, E.; Baroukh, B.; Brun, A.; Chaussain, C.; Marie, P.J.; Saffar, J.L.; Cherruau, M. Different sympathetic pathways control the metabolism of distinct bone envelopes. Bone 2012, 50, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauprivez, C.; Bataille, C.; Baroukh, B.; Llorens, A.; Lesieur, J.; Marie, P.J.; Saffar, J.L.; Biosse Duplan, M.; Cherruau, M. Periosteum Metabolism and Nerve Fiber Positioning Depend on Interactions between Osteoblasts and Peripheral Innervation in Rat Mandible. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Y.; Lieu, S.; Hu, D.; Miclau, T.; Colnot, C. Site specific effects of zoledronic acid during tibial and mandibular fracture repair. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavropoulos, A.; Rizzoli, R.; Ammann, P. Different responsiveness of alveolar and tibial bone to bone loss stimuli. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007, 22, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.L.; Li, C.L.; Lu, W.W.; Cai, W.X.; Zheng, L.W. Skeletal site-specific response to ovariectomy in a rat model: Change in bone density and microarchitecture. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Differential responses of mandibular condyle and femur to oestrogen deficiency in young rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 1998, 43, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damek-Poprawa, M.; Both, S.; Wright, A.C.; Maity, A.; Akintoye, S.O. Onset of mandible and tibia osteoradionecrosis: A comparative pilot study in the rat. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 115, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavropoulos, A.; Ammann, P.; Bresin, A.; Kiliaridis, S. Masticatory demands induce region-specific changes in mandibular bone density in growing rats. Angle Orthod. 2005, 75, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavropoulos, A.; Kiliaridis, S.; Rizzoli, R.; Ammann, P. Normal masticatory function partially protects the rat mandibular bone from estrogen-deficiency induced osteoporosis. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 2666–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Janovszky, A.; Pocs, L.; Boros, M. The periosteal microcirculation in health and disease: An update on clinical significance. Microvasc. Res. 2017, 110, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.; Smith, T. Malnutrition: Causes and consequences. Clin. Med. 2010, 10, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Kito, S.; Morimoto, A.; Haneji, T.; Kimura, M.; Ohba, T. Quantitative radiographic changes in the mandible and the tibia in systemically loaded rats fed a low-calcium diet. Oral Dis. 2000, 6, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Imamura, H.; Uchikanbori, S.; Fujita, Y.; Maki, K. Effects of restricted calcium intake on bone and maxillofacial growth. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globus, R.K.; Bikle, D.D.; Morey-Holton, E. Effects of simulated weightlessness on bone mineral metabolism. Endocrinology 1984, 114, 2264–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, H.; Sato, T.; Oka, M.; Hara, T.; Mori, S. Effect of calcium supplementation on bone dynamics of the maxilla, mandible and proximal tibia in experimental osteoporosis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2002, 29, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, N.; Karaplis, A.; Goltzman, D.; Miao, D. Distinctive anabolic roles of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) and parathyroid hormone in teeth and mandible versus long bones. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 203, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Bi, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Li, Y. Different bone sites-specific response to diabetes rat models: Bone density, histology and microarchitecture. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsey, J.L. Risk factors for osteoporosis and associated fractures. Public Health Rep. 1989, 104, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, J.M.; Russell, L.; Khan, S.N. Osteoporosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000, 372, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pham, S.M.; Crabbe, D.L. Effects of oestrogen deficiency on rat mandibular and tibial microarchitecture. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2003, 32, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, Y.; Ito, K.; Murai, S. Effects of experimental osteoporosis on alveolar bone loss in rats. J. Oral Sci. 1998, 40, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, C.M.; Moraes, R.M.; Gomes, F.C.; Marcondes, M.S.; Lima, G.M.; Anbinder, A.L. Ovariectomy-associated changes in interradicular septum and in tibia metaphysis in different observation periods in rats. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2015, 211, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, J.H.; Han, S.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Jeon, K.J.; Jung, H.I. Site-specific and time-course changes of postmenopausal osteoporosis in rat mandible: Comparative study with femur. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai, Y.; Kawamata, R.; Sakurai, T.; Kanno, M.; Kashima, I. Influence of prednisolone-induced osteoporosis on bone mass and bone quality of the mandible in rats. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2009, 38, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, K.; Yonezu, H.; Kawashima, S.; Honda, K.; Arai, Y.; Shibahara, T. A longitudinal study of the effect of experimental osteoporosis on bone trabecular structure in the rat mandibular condyle. Cranio 2013, 31, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Sato, T.; Oka, M.; Mori, S.; Shirai, H. Effects of ovariectomy and/or dietary calcium deficiency on bone dynamics in the rat hard palate, mandible and proximal tibia. Arch. Oral Biol. 2001, 46, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutel, X.; Delattre, J.; Marchandise, P.; Falgayrac, G.; Behal, H.; Kerckhofs, G.; Penel, G.; Olejnik, C. Mandibular bone is protected against microarchitectural alterations and bone marrow adipose conversion in ovariectomized rats. Bone 2019, 127, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsubeihi, E.S.; Heersche, J.N. Comparison of the effect of ovariectomy on bone mass in dentate and edentulous mandibles of adult rats. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2009, 17, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beattie, A.; Cournane, S.; Finucane, C.; Walsh, J.B.; Stassen, L.F.A. Quantitative Ultrasound of the Mandible as a Novel Screening Approach for Osteoporosis. J. Clin. Densitom. 2018, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemetti, E.; Vainio, P.; Lassila, V.; Alhava, E. Cortical bone mineral density in the mandible and osteoporosis status in postmenopausal women. Scand. J. Dent. Res. 1993, 101, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaidina, A.; Soboleva, U.; Daukste, I.; Zvaigzne, A.; Lejnieks, A. Postmenopausal osteoporosis and tooth loss. Stomatologija 2011, 13, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, W.H.; Miclau, T.; Chow, S.K.; Yang, F.F.; Alt, V. Fracture healing in osteoporotic bone. Injury 2016, 47, S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, T.; Niimi, A.; Sawai, T.; Ueda, M. Effects of steroid-induced osteoporosis on osseointegration of titanium implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 1998, 13, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zheng, C.; Gao, B.; Xu, X.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; et al. Intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification are impaired differently between glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.N.; Zhang, X.H.; Liu, H.H.; Li, K.H.; Wu, Q.H.; Liu, Y.; Luo, E. Osteogenesis Differences Around Titanium Implant and in Bone Defect Between Jaw Bones and Long Bones. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 2193–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.A.; Takayama, L.; Jorgetti, V.; Pereira, R.M. Comparative study of axial and femoral bone mineral density and parameters of mandibular bone quality in patients receiving dental implants. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 1494–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, C.A.A.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Fae, D.S.; Oliveira, H.; Del Rei Daltro Rosa, C.D.; Bento, V.A.A.; Verri, F.R.; Pellizzer, E.P. Do dental implants placed in patients with osteoporosis have higher risks of failure and marginal bone loss compared to those in healthy patients? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Olsen, B.R. The roles of vascular endothelial growth factor in bone repair and regeneration. Bone 2016, 91, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, C.M.; Gabrick, K.S. Biology of Bone Formation, Fracture Healing, and Distraction Osteogenesis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, T.P.; Tiglis, M.; Cocolos, I.; Jecan, C.R. The relationship between periosteum and fracture healing. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2016, 57, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Macnab, I.; De Haas, W.G. The role of periosteal blood supply in the healing of fractures of the tibia. Clin. Orthop Relat. Res. 1974, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utvag, S.E.; Grundnes, O.; Reikeras, O. Effects of lesion between bone, periosteum and muscle on fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1998, 69, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustilo, R.B.; Merkow, R.L.; Templeman, D. The management of open fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1990, 72, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esterhai, J.L., Jr.; Queenan, J. Management of soft tissue wounds associated with type III open fractures. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1991, 22, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrhan, F.; Stockmann, P.; Nkenke, E.; Schlegel, K.A.; Guentsch, A.; Wehrhan, T.; Neukam, F.W.; Amann, K. Differential impairment of vascularization and angiogenesis in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw-related mucoperiosteal tissue. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2011, 112, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, A.D.; MacDonald, D.G. Post-irradiation changes in the blood vessels of the adult human mandible. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1995, 33, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, E.M.; Antoniades, K. Bone-vasculature interactions in the mandible: Is bone an angiogenic tissue? Med. Hypotheses 2012, 79, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai-Aql, Z.S.; Alagl, A.S.; Graves, D.T.; Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Einhorn, T.A. Molecular mechanisms controlling bone formation during fracture healing and distraction osteogenesis. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsell, R.; Einhorn, T.A. The biology of fracture healing. Injury 2011, 42, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Bae, S.-S.; Lee, P.-W.; Lee, W.; Park, Y.-H.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.; Kim, I. Comparison of Stem Cells Derived from Periosteum and Bone Marrow of Jaw Bone and Long Bone in Rabbit Models. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2012, 9, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Jin, S.; Huang, C.; Shi, B.; Chen, Z.; Ji, W. Endochondral Repair of Jawbone Defects Using Periosteal Cell Spheroids. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann, V.A.; Gauthier, O.; Terrier, A.; Bouler, J.M.; Pioletti, D.P. Implants delivering bisphosphonate locally increase periprosthetic bone density in an osteoporotic sheep model. A pilot study. Eur. Cells Mater. 2008, 16, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazsek, J.; Dobo Nagy, C.; Blazsek, I.; Varga, R.; Vecsei, B.; Fejerdy, P.; Varga, G. Aminobisphosphonate stimulates bone regeneration and enforces consolidation of titanium implant into a new rat caudal vertebrae model. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2009, 15, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Cui, W.; Que, L.; Li, C.; Tang, X.; Liu, J. Pharmacogenetics of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandro Pereira da Silva, J.; Pullano, E.; Raje, N.S.; Troulis, M.J.; August, M. Genetic predisposition for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasquete, M.E.; Gonzalez, M.; San Miguel, J.F.; Garcia-Sanz, R. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis: Genetic and acquired risk factors. Oral Dis. 2009, 15, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdzowska, B. Osteonecrosis of the jaw. Endokrynol. Pol. 2011, 62, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski, M.A.; Traina, A.A.; Deboni, M.C.; Marques, M.M.; Naclerio-Homem Mda, G. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2012, 52, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Cheong, S.; Chaichanasakul, T.; Bezouglaia, O.; Atti, E.; Dry, S.M.; Pirih, F.Q.; Aghaloo, T.L.; Tetradis, S. Periapical disease and bisphosphonates induce osteonecrosis of the jaws in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Schreyer, C.; Hafner, S.; Mast, G.; Ehrenfeld, M.; Sturzenbaum, S.; Pautke, C. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws—Characteristics, risk factors, clinical features, localization and impact on oncological treatment. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2012, 40, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.W.; Kim, J.E.; Huh, K.H.; Yi, W.J.; Heo, M.S.; Lee, S.S.; Choi, S.C. Radiological manifestations and clinical findings of patients with oncologic and osteoporotic medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.Q.S.; Van Dessel, J.; Jacobs, R.; Ferreira, G.Z.; da Silva Santos, P.S.; Nicolielo, L.F.P.; Duarte, M.A.H.; Rubira-Bullen, I.R.F. High doses of zoledronic acid induce differential effects on femur and jawbone microstructure. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Z.F.; Xu, K.; Ma, Y.L.; Liu, J.H.; Dai, R.C.; Zhang, Y.H.; Jiang, Y.B.; Liao, E.Y. Zoledronate reverses mandibular bone loss in osteoprotegerin-deficient mice. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabelo, G.D.; Travencolo, B.A.; Oliveira, M.A.; Beletti, M.E.; Gallottini, M.; Silveira, F.R. Changes in cortical bone channels network and osteocyte organization after the use of zoledronic acid. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 59, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Yamachika, E.; Nakanishi, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Nakatsuji, K.; Matsubara, M.; Moritani, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Fujii, T.; Iida, S. Molecular alterations of newly formed mandibular bone caused by zoledronate. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyhanart, S.R.; Escudero, N.D.; Mandalunis, P.M. Effect of alendronate on the mandible and long bones: An experimental study in vivo. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 78, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.S.; Cunha, E.J.; de Souza, J.F.; Sant’Ana, R.D.; Zielak, J.C.; Costa-Casagrande, T.A.; Giovanini, A.F. Alendronate induces postnatal maxillary bone growth by stimulating intramembranous ossification and preventing premature cartilage mineralization in the midpalatal suture of newborn rats. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1494–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Qing, L.; Harrison, G.; Golub, E.; Akintoye, S.O. Anatomic site variability in rat skeletal uptake and desorption of fluorescently labeled bisphosphonate. Oral Dis. 2011, 17, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Tsai, M.C.; Lee, J.X.; Wong, C.; Cheng, Y.N.; Liu, A.C.; Liang, Y.F.; Fang, C.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Lee, I.T. Bisphosphonates and Their Connection to Dental Procedures: Exploring Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. Cancers 2023, 15, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, G.A.; Fleisch, H.A. Bisphosphonates: Mechanisms of action. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruotti, N.; Corrado, A.; Neve, A.; Cantatore, F.P. Bisphosphonates: Effects on osteoblast. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Hiraga, T.; Ueda, A.; Wang, L.; Matsumoto-Nakano, M.; Hata, K.; Yatani, H.; Yoneda, T. Zoledronic acid delays wound healing of the tooth extraction socket, inhibits oral epithelial cell migration, and promotes proliferation and adhesion to hydroxyapatite of oral bacteria, without causing osteonecrosis of the jaw, in mice. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2010, 28, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, J.; Koi, K.; Yang, D.Y.; McCauley, L.K. Effect of zoledronate on oral wound healing in rats. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J.I.; Akhter, M.P.; Kimmel, D.B.; Pingel, J.E.; Williams, A.; Jorgensen, M.; Kesavalu, L.; Wronski, T.J. Oncologic doses of zoledronic acid induce osteonecrosis of the jaw-like lesions in rice rats (Oryzomys palustris) with periodontitis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 2130–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, M.; Dehghan, A.; Amini, P.; Rezaeian, L.; Doulati, S. Evaluation of mandibular fracture healing in rats under zoledronate therapy: A histologic study. Injury 2017, 48, 2683–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.; Bonjean, K.; Ruetz, S.; Bellahcene, A.; Devy, L.; Foidart, J.M.; Castronovo, V.; Green, J.R. Novel antiangiogenic effects of the bisphosphonate compound zoledronic acid. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, A.M.; Ziebart, T.; Ackermann, M.; Konerding, M.A.; Walter, C. Bisphosphonates’ antiangiogenic potency in the development of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws: Influence on microvessel sprouting in an in vivo 3D Matrigel assay. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevarra, C.S.; Borke, J.L.; Stevens, M.R.; Bisch, F.C.; Zakhary, I.; Messer, R.; Gerlach, R.C.; Elsalanty, M.E. Vascular alterations in the sprague-dawley rat mandible during intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. J. Oral Implant. 2015, 41, e24–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornish, J.; Bava, U.; Callon, K.E.; Bai, J.; Naot, D.; Reid, I.R. Bone-bound bisphosphonate inhibits growth of adjacent non-bone cells. Bone 2011, 49, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighton, C.T.; Lorich, D.G.; Kupcha, R.; Reilly, T.M.; Jones, A.R.; Woodbury, R.A., 2nd. The pericyte as a possible osteoblast progenitor cell. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Ming, X.; Wang, Q.; Schwarz, E.M.; Guldberg, R.E.; O’Keefe, R.J.; Zhang, X. COX-2 from the injury milieu is critical for the initiation of periosteal progenitor cell mediated bone healing. Bone 2008, 43, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, V.; Gamer, L.; Cox, K.; Lowery, J.W.; Bosshardt, D.D.; Rosen, V. Periosteal BMP2 activity drives bone graft healing. Bone 2012, 51, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.B. Is bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw caused by soft tissue toxicity? Bone 2007, 41, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, A.; Dechow, P.C.; Spears, R.; Wright, J.M.; Kessler, H.P.; Opperman, L.A. The effects of bisphosphonates on osteoblasts in vitro. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2008, 106, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheper, M.A.; Badros, A.; Chaisuparat, R.; Cullen, K.J.; Meiller, T.F. Effect of zoledronic acid on oral fibroblasts and epithelial cells: A potential mechanism of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 144, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agis, H.; Blei, J.; Watzek, G.; Gruber, R. Is zoledronate toxic to human periodontal fibroblasts? J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acil, Y.; Moller, B.; Niehoff, P.; Rachko, K.; Gassling, V.; Wiltfang, J.; Simon, M.J. The cytotoxic effects of three different bisphosphonates in-vitro on human gingival fibroblasts, osteoblasts and osteogenic sarcoma cells. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2012, 40, e229–e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, F.P.; Wunsch, A.; Merkel, C.; Ziebart, T.; Pabst, A.; Yekta, S.S.; Blessmann, M.; Smeets, R. The influence of bisphosphonates on human osteoblast migration and integrin aVb3/tenascin C gene expression in vitro. Head Face Med. 2011, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marolt, D.; Cozin, M.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Cremers, S.; Landesberg, R. Effects of pamidronate on human alveolar osteoblasts in vitro. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, D.B. Mechanism of action, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, and clinical applications of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, O.; Gerngross, C.; Schwaiger, M.; Hohlweg-Majert, B.; Ristow, M.; Koerdt, S.; Schuster, R.; Otto, S.; Pautke, C. Does regular zoledronic acid change the bone turnover of the jaw in men with metastatic prostate cancer: A possible clue to the pathogenesis of bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaw? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubek, D.J.; Burr, D.B.; Allen, M.R. Ovariectomy stimulates and bisphosphonates inhibit intracortical remodeling in the mouse mandible. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2010, 13, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huja, S.S.; Mason, A.; Fenell, C.E.; Mo, X.; Hueni, S.; D’Atri, A.M.; Fernandez, S.A. Effects of short-term zoledronic acid treatment on bone remodeling and healing at surgical sites in the maxilla and mandible of aged dogs. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.B.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, I.; Lee, W.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, H. Evaluation of the bisphosphonate effect on stem cells derived from jaw bone and long bone rabbit models: A pilot study. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 85, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soundia, A.; Elzakra, N.; Hadaya, D.; Gkouveris, I.; Bezouglaia, O.; Dry, S.; Aghaloo, T.; Tetradis, S. Macrophage Polarization during MRONJ Development in Mice. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]