Abstract

Background: The quest for minimally invasive disinfection in endodontics has led to using Erbium:Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet (Er:YAG) lasers. Conventional approaches may leave bacterial reservoirs in complex canal anatomies. Er:YAG’s strong water absorption generates photoacoustic streaming, improving smear layer removal with lower thermal risk than other laser systems. Methods: This systematic review followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Database searches (PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library) identified studies (2015–2025) on Er:YAG laser-assisted root canal disinfection. Fifteen articles met the inclusion criteria: antibacterial efficacy, biofilm disruption, or smear layer removal. Data on laser settings, irrigants, and outcomes were extracted. The risk of bias was assessed using a ten-item checklist, based on guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Results: All studies found Er:YAG laser activation significantly improved root canal disinfection over conventional or ultrasonic methods. Photon-induced photoacoustic streaming (PIPS) and shock wave–enhanced emission photoacoustic streaming (SWEEPS) yielded superior bacterial reduction, especially apically, and enabled lower sodium hypochlorite concentrations without sacrificing efficacy. Some research indicated reduced post-operative discomfort. However, protocols, laser parameters, and outcome measures varied, limiting direct comparisons and emphasizing the need for more standardized, long-term clinical trials. Conclusions: Er:YAG laser-assisted irrigation appears highly effective in biofilm disruption and smear layer removal, supporting deeper irrigant penetration. While findings are promising, further standardized research is needed to solidify guidelines and confirm Er:YAG lasers’ long-term clinical benefits.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

Root canal therapy aims to eradicate microbial infection and prevent reinfection within the intricate canal system [1,2]. Despite advances in endodontic techniques, effective disinfection remains a critical challenge [1,2]. Conventional approaches—such as mechanical instrumentation coupled with chemical irrigants like sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)—often leave behind residual bacteria, debris, and smear layers in complex canal anatomies [3]. These shortcomings can lead to persistent infections, post-operative discomfort, and, ultimately, treatment failure if not adequately addressed [4]. Consequently, the pursuit of more efficient and minimally invasive disinfection methods has garnered significant interest within the endodontic community [5,6]. Eradicating bacteria and removing debris from the intricately shaped root canal system are paramount to ensuring successful endodontic outcomes [7]. Conventional mechanical instrumentation, while essential, often fails to thoroughly clean recesses such as isthmuses, lateral canals, and deep dentinal tubules, leaving residual bacterial colonies that can compromise healing and lead to long-term treatment failures [8]. Traditional chemical irrigants, including sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), play a significant role in dissolving organic tissue and removing smear layers, but their effectiveness is limited by factors such as contact time, canal anatomy, and the capability of the irrigating fluid to penetrate microchannels [9,10,11]. Sodium hypochlorite is toxic, which necessitates careful handling to avoid potential tissue damage and adverse effects [9,10,11]. In pursuit of more efficient and predictable disinfection, laser-based methods have garnered increasing attention [11,12]. Among them, the Erbium: Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet (Er:YAG) laser distinguishes itself by operating at a wavelength (2940 nm) that is highly absorbed by water molecules [13]. This characteristic promotes the generation of strong photoacoustic streaming and cavitation effects when the laser interacts with irrigating solutions inside the root canal system, creating shockwaves powerful enough to penetrate areas not easily reached by standard methods [13,14,15]. Consequently, Er:YAG laser-activated irrigation may bolster bacterial reduction, augment smear layer removal, and improve dentinal tubule penetration [16]. Moreover, Er:YAG lasers typically produce less heat compared to other laser systems (e.g., diode, Nd:YAG) due to their shorter depth of penetration and high water absorption [17]. This reduced thermal effect on the dentin surface lowers the risk of structural damage or compromised mechanical properties, making Er:YAG lasers especially suitable for delicate or thin-walled roots. Initial studies also suggest potential advantages in pediatric endodontics, where preserving tooth structure is vital, and in regenerative or revascularization procedures aimed at stimulating tissue healing within the root canal space [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. However, despite these promising attributes, considerable heterogeneity exists in reported protocols, laser parameters, study designs, and measured outcomes, underscoring the need for a systematic review to establish clearer insights into the clinical utility and optimal application strategies of Er:YAG laser technology in root canal disinfection [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Laser-Activated Irrigation (LAI) using Erbium:Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet (Er:YAG) lasers has emerged as a promising technique for enhancing root canal disinfection through Photon-Induced Photoacoustic Streaming (PIPS) and Shock Wave-Enhanced Emission Photoacoustic Streaming (SWEEPS), both of which improve smear layer removal and biofilm disruption [16,17,18,19,20].

1.2. Objectives

This systematic review aims to consolidate and evaluate the evidence on Er: YAG laser-assisted root canal disinfection by comparing its efficacy in bacterial reduction, biofilm eradication, and smear layer removal to both conventional and other laser-based methods. The study seeks to address the following key research question: Does Er:YAG laser technology provide superior root canal disinfection compared to conventional disinfection methods, and how can it be optimised for clinical application? Moreover, by identifying methodological inconsistencies and gaps in current research, this review provides recommendations for optimizing clinical procedures and refining experimental designs. Finally, it examines whether Er:YAG technology can be feasibly integrated into standard practice.

1.3. Justification

The need for conducting this study is underscored by the persistent challenges in achieving optimal root canal disinfection, a crucial factor in the long-term success of endodontic treatments. Conventional irrigation techniques often fail to fully eliminate bacterial biofilms and debris from complex root canal anatomies, leading to reinfection and treatment failures. The emergence of Er:YAG laser technology presents a promising alternative, offering superior antibacterial effects, enhanced smear layer removal, and improved penetration of irrigants into dentinal tubules. This topic is highly relevant to the field of odontology, particularly in endodontics and periodontics, where bacterial control is paramount. In endodontics, the ability of Er:YAG lasers to enhance disinfection could significantly improve clinical outcomes, reducing the likelihood of post-treatment infections and enhancing the longevity of root canal treatments. In periodontics, Er:YAG lasers have demonstrated potential in minimally invasive periodontal therapy, promoting better healing outcomes by effectively targeting bacterial deposits without causing excessive thermal damage. Given the growing interest in laser-assisted endodontic procedures and the need for evidence-based guidelines, this systematic review will contribute to the field by consolidating existing research, identifying gaps in knowledge, and providing insights into the optimal application of Er:YAG laser technology in clinical practice. The findings of this study could inform future clinical protocols and encourage broader adoption of laser-assisted irrigation techniques, ultimately improving patient outcomes in both endodontic and periodontal treatments.

2. Methods

2.1. Focused Question

A systematic review was conducted following the PICO framework [29], structured as follows: Among patients undergoing root canal therapy (Population), does the use of Er: YAG laser technology (Intervention) result in superior disinfection outcomes compared to conventional disinfection methods (Comparison) in improving the effectiveness of root canal disinfection (Outcome)?

2.2. Search Strategy

This systematic review, registered with PROSPERO under the number CRD42025638319 [30], adhered to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure thorough and transparent reporting [31]. A detailed search strategy was employed across multiple databases, including PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, using a set of predefined keywords [28]. Independent searches were conducted by three researchers, following uniform protocols. The review included English-language studies published between 1 January 2015, and 3 January 2025, based on specific eligibility criteria. Two reviewers independently screened articles at the title, abstract, and full-text levels. Additionally, reference lists of selected studies were reviewed to uncover further relevant publications. The search syntax used to obtain these studies is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search syntax used in the study.

2.3. Selection of Studies

During the selection phase of this systematic review, the four reviewers independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies to maintain impartiality in the inclusion process. Any disagreements regarding a study’s eligibility were resolved through collaborative discussion until a mutual agreement was reached. This meticulous approach, aligned with PRISMA guidelines, ensured the inclusion of only the most relevant and methodologically robust studies, enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of the review [31].

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review focused on studies investigating the use of Er:YAG laser technology in root canal disinfection, encompassing both in vitro experiments and animal research. Studies that explored the combination of Er:YAG laser treatment with other antimicrobial or adjunctive therapies were also eligible for inclusion. Research with control groups comparing Er:YAG laser disinfection to standard mechanical cleaning, alternative non-surgical techniques, or no treatment was included, as well as studies directly comparing the effectiveness of Er:YAG lasers with other non-surgical approaches. Long-term studies evaluating the sustained impact of Er:YAG laser technology on key outcomes, such as bacterial reduction, infection control, and healing of periapical tissues, were prioritized. Only publications meeting predefined quality standards (Table 2) and specifically addressing the effectiveness or role of Er:YAG lasers in improving root canal disinfection were considered for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria for this systematic review encompassed grey and unpublished literature, such as dissertations, conference abstracts, theses, and non-peer-reviewed materials, as well as articles published in languages other than English. Duplicate publications or those with identical ethical approval numbers were excluded. Studies that focused on topics outside the scope of root canal disinfection with Er:YAG laser technology were not included, along with those using alternative laser systems or methods unrelated to Er:YAG. In vitro studies that did not simulate clinically relevant dental conditions or address pertinent microbial strains were excluded. Additionally, non-primary data formats, such as case reports, case series, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, editorials, and books, were omitted, as were studies lacking a control or comparison group. Finally, studies involving non-therapeutic applications of Er:YAG lasers were not considered.

2.4. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies and Quality Assessment

To initiate the study selection process for this systematic review, each reviewer conducted an independent evaluation of the titles and abstracts of articles related to Er:YAG applications in root canal treatment, aiming to minimize bias. Consistency in decision-making was ensured by calculating inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa statistic [32]. Any disagreements regarding a study’s inclusion were addressed through in-depth discussions, ultimately resulting in a unanimous resolution.

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers to ensure reliability and objectivity. The evaluation focused on key aspects of Er:YAG laser disinfection, assigning a score of 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no” responses to the following criteria: (1) Was the study design clearly defined and appropriate for assessing Er:YAG laser disinfection? (2) Were the laser parameters (e.g., wavelength, power output, energy settings, pulse duration, and repetition rate) explicitly stated and justified? (3) Did the study include both positive and negative control groups for comparison? (4) Were root canal samples standardized in size, anatomy, and preparation protocols? (5) Was the laser application protocol clearly described, including duration, delivery method, and number of applications? (6) Were primary and secondary outcome measures (e.g., bacterial reduction, disinfection efficiency) clearly defined and appropriate? (7) Was there complete reporting of outcome data without missing or inconsistent information? (8) Were numerical results accompanied by appropriate statistical analyses? (9) Was the study conducted independently of its funding sources to avoid conflicts of interest? (10) Were participants, investigators, or evaluators blinded to treatment allocations to minimize bias? Based on the total “yes” responses, each study’s risk of bias was categorized as high (0–3 points), moderate (4–6 points), or low (7–10 points), following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [33]. This comprehensive quality assessment ensured that only studies with robust and reliable methodologies were included in the review, enhancing the validity and credibility of its findings.

Table 2 presents a comprehensive assessment of bias risk across the ten studies included in the final analysis. Studies were required to achieve a minimum score of six points based on the predefined evaluation criteria to qualify for inclusion. All studies met the criteria for low bias risk. Notably, no studies fell into the categories of moderate or high bias risk, underscoring the dependability of the systematic review’s conclusions.

Table 2.

The outcomes of the quality evaluation and bias risk assessment for the studies.

Table 2.

The outcomes of the quality evaluation and bias risk assessment for the studies.

| Author and Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afkhami et al. 2021 [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Low |

| Bao et al. 2024 [35] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | Low |

| Deleu et al. 2015 [36] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Low |

| Ozbay et al. 2018 [37] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Low |

| Lei et al. 2022 [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | Low |

| Liu et al. 2023 [39] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Low |

| Mandras et al. 2020 [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Low |

| Murugesh Yavagal et al. 2021 [41] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Low |

| Neelakantan et al. 2015 [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 | Low |

| Rahmati et al. 2022 [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Low |

| Shan et al. 2022 [44] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 | Low |

| Todea et al. 2018 [45] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | Low |

| Yang et al. 2024 [46] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Low |

| Zhao et al. 2024 [47] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Low |

2.5. Data Extraction

After finalizing the selection of relevant studies the two reviewers systematically extracted detailed information from each included article. This process involved recording bibliographic details such as the lead author’s name and the year of publication, the study design, the specific dental conditions addressed, and the types of experimental and control groups employed. They also documented the duration of follow-up periods, measured outcomes related to root canal disinfection effectiveness, and technical specifications of the Er:YAG laser systems used, including wavelength, power settings, pulse duration, and delivery methods. Additionally, the reviewers noted any adjunctive treatments or methodologies incorporated into the studies, such as irrigation solutions or additional antimicrobial protocols. This meticulous and comprehensive data extraction ensured that all relevant variables were thoroughly captured, allowing for a detailed analysis of the efficacy and operational parameters of Er:YAG laser technology in root canal disinfection. This rigorous approach facilitated a deeper understanding of the clinical applications of Er:YAG lasers, thereby enhancing the reliability and scope of the systematic review’s findings.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

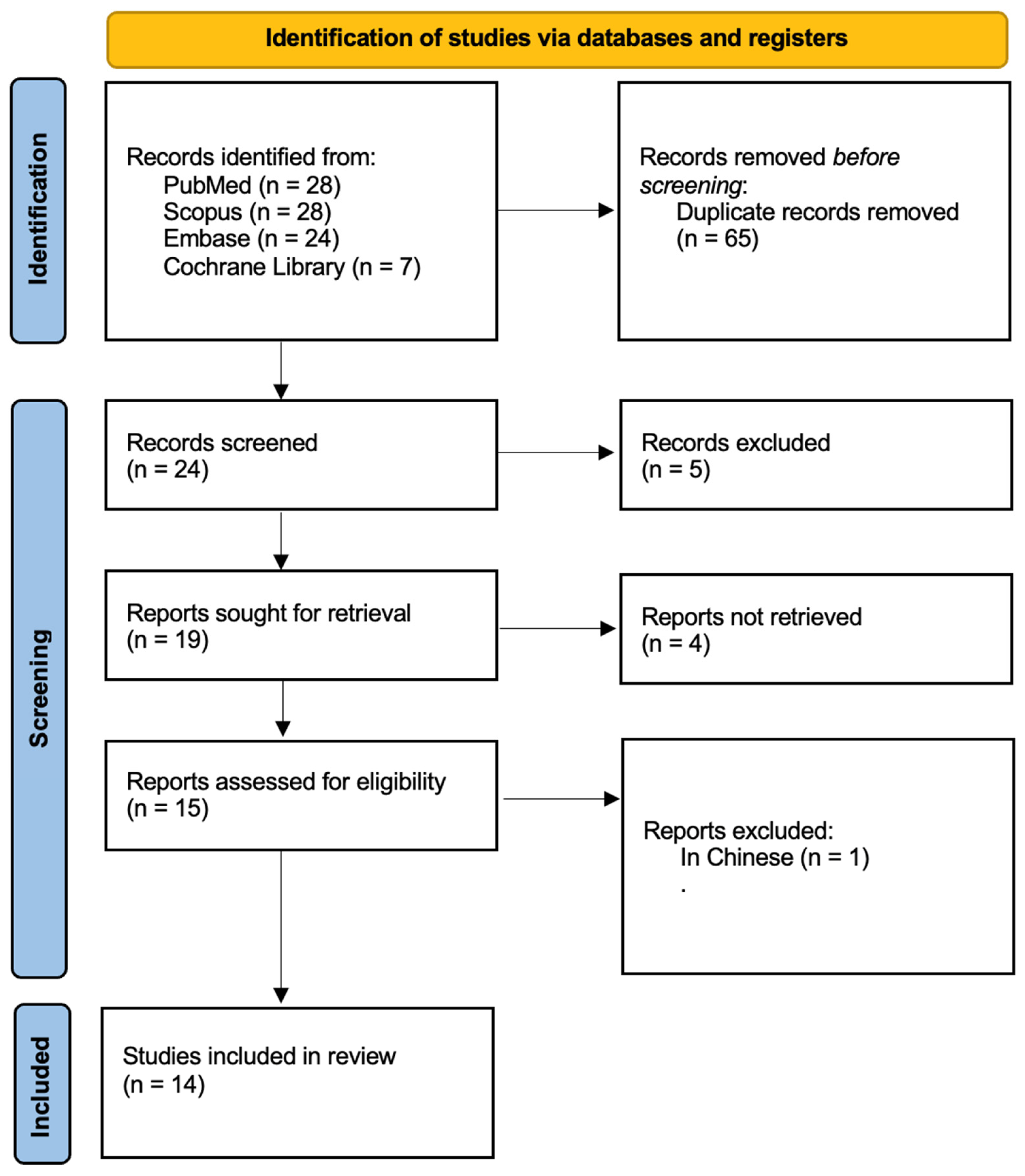

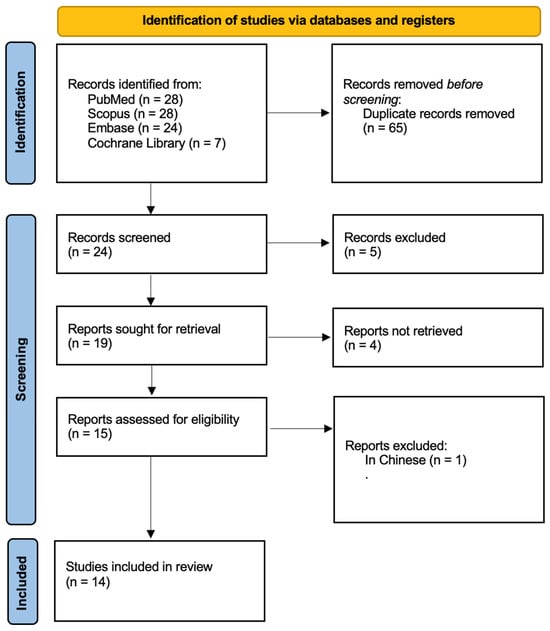

Figure 1 outlines the research workflow, carefully structured in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [31]. The process commenced with an initial literature search, yielding 87 articles. After removing duplicate entries, 24 records were retained. A rigorous evaluation of titles and abstracts narrowed the selection to 15 studies, all of which underwent full-text review. One article was excluded as it did not have an English version. Ultimately, 14 studies published were included in the final analysis. Detailed characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Prisma 2020 flow diagram.

Table 3.

Summary of the Studies.

3.2. Data Presentation

Data from the 15 studies that met the inclusion criteria were meticulously extracted and systematically organised into Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. These tables offer a comprehensive summary of each study, highlighting critical details such as the specifications of the light sources utilised and the properties of riboflavin as a photosensitiser in PDT protocols. This structured format facilitates in-depth comparisons and detailed analyses of Er:YAG laser applications across the included studies, providing a strong foundation for evaluating its effectiveness and methodological approaches in managing dental conditions.

Table 4.

Main outcomes and study groups.

Table 5.

Summary of Er:YAG laser parameters from each study.

3.3. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.4. Main Study Outcomes

Er:YAG laser technology—particularly photon-induced photoacoustic streaming (PIPS) and shock wave-enhanced emission photoacoustic streaming (SWEEPS)—has consistently demonstrated superior root canal disinfection compared to conventional methods, achieving up to 91.03% bacterial reduction and effectively removing biofilms from complex canal regions [34,35]. Studies revealed enhanced debris and smear layer removal [36], with Er:YAG laser activation outperforming Nd:YAG in facilitating sealer penetration [37]. Even at lower concentrations, sodium hypochlorite-maintained disinfection efficacy when activated by SWEEPS [38], and LAI-PIPS surpassed ultrasonic and syringe irrigation by producing stronger shockwave-like effects [39]. PIPS also demonstrated improved antibacterial outcomes with less post-operative discomfort [40] and complete elimination of Enterococcus faecalis in primary teeth [41]. When combined with specific irrigant protocols, the Er:YAG laser effectively disrupted mature biofilms [42], removed the smear layer while sealing dentinal tubules, and enhanced stem cell adhesion, unlike MTAD treatment [43]. Its efficiency remained high regardless of minimally invasive or conventional canal access [44], as it facilitated thorough cleaning across all canal sections without structural damage [45]. Furthermore, pairing the Er:YAG laser with photodynamic therapy led to 99.97% bacterial reduction [46], and PIPS using low-concentration NaOCl surpassed conventional needle irrigation in eliminating bacteria and improving clinical outcomes [47]. Table 4 presents the main outcomes of the included studies. Table 5 shows the parameters of the light sources used in this study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of Other Evidence

Er:YAG laser activation shows remarkable synergy with various irrigants, including silver nanoparticles and sodium hypochlorite, producing powerful photoacoustic shockwaves that increase bacterial reduction in complex canal anatomies [34,45]. It consistently outperforms or closely rivals conventional needle irrigation, passive ultrasonic irrigation, and sonic activation by achieving deeper irrigant penetration and superior biofilm removal, especially in the apical third [35,47]. The generation and implosion of vapor bubbles (cavitation) at the Er:YAG laser tip creates strong fluid dynamics that effectively flush debris from irregular canal walls, surpassing the cleaning capacity of manual-dynamic methods and diode lasers [35]. Activation with Er:YAG lasers also proves more efficient in removing the smear layer and enhancing sealer penetration compared to Nd:YAG laser treatments, particularly in curved root canals [37,42]. By employing Shock Wave Enhanced Emission Photoacoustic Streaming (SWEEPS), practitioners can use lower NaOCl concentrations without sacrificing antimicrobial efficacy, thus reducing the risk of tissue damage [38]. Photon-induced photoacoustic streaming (PIPS), especially when operating at subablative parameters, excels at cleaning beyond fractured instruments and in narrow or complex canal configurations by creating more vigorous bubble collapse and shockwaves [39,45]. In pediatric endodontics, PIPS has demonstrated near-complete bacterial elimination against Enterococcus faecalis in primary teeth, underscoring its potential for minimally invasive yet highly effective [41]. Clinical studies also report reduced post-operative discomfort, including diminished pain and faster symptom resolution, when Er:YAG laser irrigation is used instead of traditional or ultrasonic approaches [40,44]. Combining Er:YAG laser activation with photodynamic therapy (PDT) can yield bactericidal effects comparable or superior to standard NaOCl protocols, achieving up to 99.97% bacterial reduction and minimizing cytotoxic concerns [46]. Finally, Er:YAG laser treatment not only cleans canal walls effectively but also preserves or enhances dentinal surface properties conducive to cell attachment, making it a promising adjunct in regenerative endodontic procedures that require favorable stem cell adhesion and biocompatibility [39].

Other studies have reached similar conclusions regarding the effectiveness of laser-based treatments in dentistry. For instance, Otero (2024) demonstrated that laser-activated irrigation (LAI) using various wavelengths influences root canal smear-layer removal and dentin micromorphology in different ways [48]. Specifically, Er:YAG lasers partially cleaned the smear layer, while CO₂ and diode lasers at certain power settings either cleaned and opened dentinal tubules or melted and sealed them with recrystallized material [48]. In addition to endodontic applications, Er:YAG lasers have proven beneficial in conservative and restorative dentistry [48,49]. Fornaini (2013) showed that Er:YAG lasers can serve as an effective alternative to traditional turbine and micro-motor tools in adhesive procedures. When combined with orthophosphoric acid, Er:YAG laser treatment improved bond strength, reduced microleakage, diminished patient discomfort, and led to higher satisfaction levels [25]. Er:YAG lasers have also been investigated for periodontal applications [25]. Aoki et al. found that Er:YAG laser debridement of root surfaces and bone defects is both safe and effective, delivering results that are comparable or superior to those of conventional mechanical methods [49]. Moreover, their findings highlighted the Er:YAG laser’s utility as a preparatory device in periodontal flap surgery [30]. Similarly, Yaneva et al. showed that Er:YAG laser use in non-surgical periodontal therapy is clinically equivalent to hand instrumentation and can provide enhanced long-term stability [50]. Beyond periodontal treatment, Er:YAG lasers offer advantages in orthodontic care. Al-Jundi et al. concluded that Er:YAG laser application accelerates orthodontic tooth movement while significantly reducing post-treatment pain and discomfort [51]. In implant dentistry, Kriechbaumer et al. demonstrated that Er:YAG lasers enable precise, non-toxic, and highly effective removal of biofilm from metal implants, thereby presenting clear benefits over conventional disinfectants in infection control and implant retention procedures [52]. Further supporting its versatility, Taniguchi et al. revealed that Er:YAG laser-assisted bone regenerative therapy (Er-LBRT) without barrier membranes can achieve favorable ridge preservation (RP) and ridge augmentation (RA). This approach promoted sufficient bone regeneration for implant placement and ensured successful wound healing along with long-term peri-implant stability [53]. Stübinger similarly recognized the Er:YAG laser’s 2.94 μm wavelength—matching the water absorption peak—as an effective alternative to conventional bone ablation methods. Although modern short-pulsed Er:YAG systems address many earlier concerns (e.g., tissue damage, delayed healing, and extended osteotomy times), limitations such as depth control and safe beam guidance still hinder their routine use in oral and implant surgery [54]. Finally, Li et al. reported that Er:YAG lasers can deliver health benefits for peri-implantitis patients, notably by reducing probing depth (PD) and gingival recession (GR). However, they stressed the need for further research to confirm these promising results due to the inherent limitations of the included studies [55,56,57,58]. Collectively, these findings underscore the expanding role of Er:YAG lasers in dentistry—from endodontics to periodontics, orthodontics, and implantology—while also emphasizing the necessity of continued research and technological refinement to optimize clinical outcomes.

4.2. Limitations of the Evidence

Despite the overall positive outcomes reported, several limitations in the existing body of evidence on Er:YAG laser-assisted root canal disinfection preclude drawing definitive conclusions. First, heterogeneity in study designs and protocols—such as variations in laser settings, irrigation regimens, and outcome measurements—makes direct comparisons difficult and complicates attempts at meta-analysis. Second, while in vitro and ex vivo experiments offer mechanistic insights, their clinical applicability may be limited by small sample sizes and the absence of in vivo conditions such as tissue fluid or patient factors. Third, many included clinical studies feature modest participant numbers, short follow-up periods, or no standardized measures of long-term success (e.g., radiographic or histological healing). Fourth, the lack of uniform protocols for bacterial assessment—ranging from colony-forming units to molecular methods—introduces further variability in the reported efficacy. Finally, restricting the review to English-language and peer-reviewed publications, along with potential inconsistencies in blinding and randomization, raises the risk of selection and publication bias.

4.3. Limitations of the Review Process

Despite adhering to PRISMA guidelines and employing a thorough search strategy across multiple databases, the review process itself is subject to several limitations. First, restricting the included studies to those published in English may introduce language bias and potentially exclude relevant research in other languages. Second, the exclusion of grey literature—such as conference proceedings, theses, and unpublished studies—can lead to publication bias, as positive findings are more frequently published than negative or inconclusive results. Third, the substantial heterogeneity in study designs, laser protocols, and outcome measures among the included papers limited the feasibility of conducting a quantitative meta-analysis and necessitated a largely narrative synthesis of findings. Additionally, although dual screening and data extraction were performed to reduce selection bias, subjectivity in interpreting study methodologies and outcomes remains a concern. Finally, the absence of a uniform quality-rating framework, beyond the presented risk-of-bias checklist, further constrains the ability to make broad, definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of Er:YAG laser-assisted root canal disinfection.

4.4. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

Er:YAG laser technology holds considerable promise for elevating clinical outcomes in root canal disinfection, yet its integration into mainstream practice requires further standardization and research. For clinicians, the review findings underscore the potential of Er:YAG lasers to facilitate deeper irrigant penetration, effectively remove smear layers, and minimize bacterial loads—even in complex anatomies—thereby enhancing both immediate disinfection and long-term prognosis. Policy-wise, professional bodies, and regulatory agencies could develop evidence-based guidelines on Er:YAG laser parameters (e.g., energy settings, pulse duration) and optimal adjunctive irrigants, ensuring safe and standardized application in various endodontic scenarios. Future research should prioritize larger-scale, multicenter clinical trials with extended follow-up intervals to capture long-term success and cost-effectiveness, while also exploring specialized areas such as pediatric endodontics or regenerative procedures. Additionally, harmonizing study methodologies—ranging from bacterial assessment techniques to operator training—would enable more robust comparisons across research and lay a more consistent foundation for the clinical deployment of Er:YAG laser-assisted irrigation.

This study adds to the existing body of knowledge by systematically reviewing and comparing the effectiveness of Er:YAG laser-assisted root canal disinfection against conventional and other laser-based methods. While previous studies have explored various laser applications in endodontics, there remains a lack of consensus regarding standardized protocols and optimal laser parameters for effective disinfection. A key novelty of this study is its focus on recent advancements in Er:YAG laser technology, specifically PIPS, and SWEEPS, which have demonstrated enhanced fluid dynamics and deeper irrigant penetration. Unlike diode and Nd:YAG lasers, which primarily rely on thermal effects, the Er:YAG laser’s ability to generate shockwaves without excessive heat reduces the risk of structural damage to dentin while achieving superior bacterial reduction. Additionally, this review highlights the potential for Er:YAG laser technology to enable the use of lower concentrations of sodium hypochlorite without compromising antimicrobial efficacy. This is particularly relevant in minimizing the cytotoxic effects associated with chemical irrigants. Furthermore, by identifying gaps in current research, this study sets the stage for future investigations into long-term clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and potential applications of Er:YAG lasers in regenerative endodontic procedures and pediatric dentistry. Overall, this study advances the field by providing a comprehensive analysis of Er:YAG laser-assisted disinfection, emphasizing its unique advantages over other laser types and proposing recommendations for optimized clinical implementation.

5. Conclusions

Er:YAG laser-assisted irrigation outperforms conventional methods, providing better bacterial reduction, deeper irrigant penetration, and improved smear layer removal. PIPS and SWEEPS further enhance fluid dynamics and biofilm disruption, reducing reliance on high NaOCl concentrations. However, variability in settings and limited long-term data highlight the need for standardized protocols and larger studies. Er:YAG lasers offer superior disinfection with minimal thermal damage, making them valuable in endodontics and periodontics for minimally invasive bacterial decontamination. Their use in pediatric and regenerative endodontics also supports tissue preservation and effective microbial control. Challenges include high costs, specialized training requirements, and parameter inconsistencies, necessitating further research. Despite this, Er:YAG lasers show strong potential for improving root canal disinfection and long-term treatment outcomes, positioning them as a viable alternative to conventional methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-R., Z.G.-L. and K.G.-L., methodology, J.F.-R. and R.W.; software, J.F.-R., Z.G.-L., K.G.-L., A.Z. and R.W.; formal analysis, J.F.-R., Z.G.-L., K.G.-L., A.Z. and R.W.; investigation, J.F.-R., A.Z., M.T. and R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-R., Z.G.-L., K.G.-L., A.Z., M.T. and R.W.; writing—review and editing, J.F.-R., Z.G.-L., K.G.-L., A.Z., M.T. and R.W.; supervision, K.G.-L., A.Z. and R.W.; funding acquisition Z.G.-L., K.G.-L., A.Z. and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wong, J.; Manoil, D.; Näsman, P.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Neelakantan, P. Microbiological Aspects of Root Canal Infections and Disinfection Strategies: An Update Review on the Current Knowledge and Challenges. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 672887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alothman, F.A.; Hakami, L.S.; Alnasser, A.; AlGhamdi, F.M.; Alamri, A.A.; Almutairii, B.M. Recent Advances in Regenerative Endodontics: A Review of Current Techniques and Future Directions. Cureus 2024, 16, e74121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hülsmann, M. Effects of mechanical instrumentation and chemical irrigation on the root canal dentin. Endod. Top. 2013, 29, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Olanrewaju, O.A.; Ansah Owusu, F.; Saleem, A.; Pavani, P.; Tariq, H.; Vasquez Ortiz, B.S.; Ram, R.; Varrassi, G. Challenges and Solutions in Postoperative Complications: A Narrative Review in General Surgery. Cureus 2023, 15, e50942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chan, M.Y.C.; Cheung, V.; Lee, A.H.C.; Zhang, C. A Literature Review of Minimally Invasive Endodontic Access Cavities—Past, Present and Future. Eur. Endod. J. 2022, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rubio, F.; Arnabat-Domínguez, J.; Sans-Serramitjana, E.; Saa, C.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Betancourt, P. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Combined with Photobiomodulation Therapy in Teeth with Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis: A Case Series. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naladkar, K.; Chandak, M.; Sarangi, S.; Agrawal, P.; Jidewar, N.; Suryawanshi, T.; Hirani, P. Breakthrough in the Development of Endodontic Irrigants. Cureus 2024, 16, e66981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Metzger, Z.; Solomonov, M.; Kfir, A. The role of mechanical instrumentation in the cleaning of root canals. Endod. Top. 2013, 29, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.P.F.A.; Aveiro, E.; Kishen, A. Irrigants and irrigation activation systems in Endodontics. Braz. Dent. J. 2023, 34, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jaju, S.; Jaju, P.P. Newer root canal irrigants in horizon: A review. Int. J. Dent. 2011, 2011, 851359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Topbaş, C.; Adıgüzel, Ö. Endodontic irrigation solutions: A review. Int. Dent. Res. 2017, 7, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob Deeb, J.; Smith, J.; Belvin, B.R.; Lewis, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Er:YAG Laser Irradiation Reduces Microbial Viability When Used in Combination with Irrigation with Sodium Hypochlorite, Chlorhexidine, and Hydrogen Peroxide. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jurič, I.B.; Anić, I. The Use of Lasers in Disinfection and Cleanliness of Root Canals: A Review. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2014, 48, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deeb, J.G.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Weaver, C.; Matys, J.; Bencharit, S. Retrieval of Glass Fiber Post Using Er:YAG Laser and Conventional Endodontic Ultrasonic Method: An In Vitro Study. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Matys, J. The Effect of Er:YAG Lasers on the Reduction of Aerosol Formation for Dental Workers. Materials 2021, 14, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Preissig, J.; Hamilton, K.; Markus, R. Current Laser Resurfacing Technologies: A Review that Delves Beneath the Surface. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2012, 26, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Do, Q.L.; Gaudin, A. The Efficiency of the Er: YAG Laser and Photon- Induced Photoacoustic Streaming (PIPS) as an Activation Method in Endodontic Irrigation: A Literature Review. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 11, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Wadhwani, K.K.; Tikku, A.P.; Chandra, A. Effect of laser-activated irrigation on smear layer removal and sealer penetration: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2020, 23, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perhavec, T.; Diaci, J. Comparison of heat deposition of Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers in hard dental tissues. J. Oral Laser Appl. 2008, 8, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nahas, P.; Zeinoun, T.; Namour, M.; Ayach, T.; Nammour, S. Effect of Er:YAG laser energy densities on thermally affected dentin layer: Morphological study. Laser Ther. 2018, 27, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sgolastra, F.; Petrucci, A.; Gatto, R.; Monaco, A. Efficacy of Er:YAG laser in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotundo, R.; Nieri, M.; Cairo, F.; Franceschi, D.; Mervelt, J.; Bonaccini, D.; Esposito, M.; Pini-Prato, G. Lack of adjunctive benefit of Er:YAG laser in non-surgical periodontal treatment: A randomized split-mouth clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepper, K.L.; Chun, Y.P.; Cochran, D.; Chen, S.; McGuff, H.S.; Mealey, B.L. Impact of Er:YAG laser on wound healing following nonsurgical therapy: A pilot study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2019, 5, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, L.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S. Comparison of clinical parameters, microbiological effects and calprotectin counts in gingival crevicular fluid between Er: YAG laser and conventional periodontal therapies: A split-mouth, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2017, 96, e9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fornaini, C. Er:YAG and adhesion in conservative dentistry: Clinical overview. Laser Ther. 2013, 22, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kanazirski, N.; Vladova, D.; Neychev, D.; Raycheva, R.; Kanazirska, P. Effect of Er:YAG Laser Exposure on the Amorphous Smear Layer in the Marginal Zone of the Osteotomy Site for Placement of Dental Screw Implants: A Histomorphological Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Gedrange, T.; Dominiak, M.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Quantitative evaluation of aerosols produced in the dental office during caries treatment: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.S.; Ferreira, L.D.S.; Junior, F.A.V.; Montagner, A.F.; Rosa, W.L.O.D.; Araújo, L.P.; Vieira, C.C. Postoperative pain in primary root canal treatments after Er: YAG laser-activated irrigation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO Framework to Improve Searching PubMed for Clinical Questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Shamseer, L.; Tricco, A.C. Registration of systematic reviews in PROSPERO: 30,000 records and counting. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method Agreement Analysis: A Review of Correct Methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M. Welch Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Afkhami, F.; Ahmadi, P.; Chiniforush, N.; Sooratgar, A. Effect of different activations of silver nanoparticle irrigants on the elimination of Enterococcus faecalis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 3869–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, P.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Xiao, N.; Shen, J.; Deng, J.; Shen, Y. In vitro efficacy of Er:YAG laser-activated irrigation versus passive ultrasonic irrigation and sonic-powered irrigation for treating multispecies biofilms in artificial grooves and dentinal tubules: An SEM and CLSM study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleu, E.; Meire, M.A.; De Moor, R.J.G. Efficacy of laser-based irrigant activation methods in removing debris from simulated root canal irregularities. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, Y.; Erdemir, A. Effect of several laser systems on removal of smear layer with a variety of irrigation solutions. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2018, 81, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, X. Laser activated irrigation with SWEEPS modality reduces concentration of sodium hypochlorite in root canal irrigation. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Watanabe, S.; Mochizuki, S.; Kouno, A.; Okiji, T. Comparison of vapor bubble kinetics and cleaning efficacy of different root canal irrigation techniques in the apical area beyond the fractured instrument. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandras, N.; Pasqualini, D.; Roana, J.; Tullio, V.; Banche, G.; Gianello, E.; Bonino, F.; Cuffini, A.M.; Berutti, E.; Alovisi, M. Influence of Photon-Induced Photoacoustic Streaming (PIPS) on Root Canal Disinfection and Post-Operative Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesh Yavagal, C.M.; Patil, V.C.; Yavagal, P.C.; Kumar, N.K.; Hariharan, M.; Mangalekar, S.B. Efficacy of laser photoacoustic streaming in pediatric root canal disinfection—An ex-vivo study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2021, 12, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, P.; Cheng, C.Q.; Mohanraj, R.; Sriraman, P.; Subbarao, C.; Sharma, S. Antibiofilm activity of three irrigation protocols activated by ultrasonic, diode laser or Er:YAG laser in vitro. Int. Endod. J. 2015, 48, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmati, A.; Karkehabadi, H.; Rostami, G.; Karami, M.; Najafi, R.; Rezaei-Soufi, L. Comparative effects of Er:YAG laser, and EDTA, MTAD, and QMix irrigants on adhesion of stem cells from the apical papilla to dentin: A scanning electron microscopic study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e310–e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, X.Y.; Tian, F.C.; Li, J.; Yang, N.; Wang, Y.Y.; Sun, H.B. Comparison of Er:YAG laser and ultrasonic in root canal disinfection under minimally invasive access cavity. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todea, D.C.M.; Luca, R.E.; Bălăbuc, C.A.; Miron, M.I.; Locovei, C.; Mocuța, D.E. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of the root canal morphology after Er:YAG laser irradiation. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Chen, W. In vitro effects of Er:YAG laser-activated photodynamic therapy on Enterococcus faecalis in root canal treatment. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 45, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Chen, M. Comparison of the effectiveness of conventional needle irrigation and photon-induced photoacoustic streaming with sodium hypochlorite in the treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, C.I. A Laser-Based Endodontic Treatment Concept. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, A.; Mizutani, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Lin, T.; Ohsugi, Y.; Mikami, R.; Katagiri, S.; Meinzer, W.; Iwata, T. Current status of Er:YAG laser in periodontal surgery. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2024, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, B.; Tomov, G.; Karaslavova, E.; Romanos, G.E. Long-Term Stability of Er:YAG Laser Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jundi, A.; Sakka, S.; Riba, H.; Ward, T.; Hanna, R. Efficiency of Er:YAG utilization in accelerating deep bite orthodontic treatment. Laser Ther. 2018, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriechbaumer, L.K.; Happak, W.; Distelmaier, K.; Thalhammer, G.; Kaiser, G.; Kugler, S.; Tan, Y.; Leonhard, M.; Zatorska, B.; Presterl, E.; et al. Disinfection of contaminated metal implants with an Er:YAG laser. J. Orthop. Res. 2020, 38, 2464–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Sawada, K.; Yamada, A.; Mizutani, K.; Meinzer, W.; Iwata, T.; Izumi, Y.; Aoki, A. Er:YAG Laser-Assisted Bone Regenerative Therapy for Implant Placement: A Case Series. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2021, 41, e137–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stübinger, S. Advances in bone surgery: The Er:YAG laser in oral surgery and implant dentistry. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2010, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Deng, J.; Ren, S. The clinical efficacy of Er:YAG lasers in the treatment of peri-implantitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 9002–9014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Kung, J.C.; Yan, D.Y.; Chen, I.H.; Jheng, Y.S.; Lai, C.H.; Wu, Y.M.; Lee, K.T. Efficacy of Er:YAG laser for the peri-implantitis treatment and microbiological changes: A randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3517–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Spirito, F.; Giordano, F.; Di Palo, M.P.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Scognamiglio, B.; Sangiovanni, G.; Caggiano, M.; Gasparro, R. Microbiota of peri-implant healthy tissues, peri-implant mucositis, and peri-implantitis: A comprehensive review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Spirito, F.; Pisano, M.; Di Palo, M.P.; Franci, G.; Rupe, A.; Fiorino, A.; Rengo, C. Peri-implantitis-associated microbiota before and after peri-implantitis treatment: The biofilm “competitive balancing” effect. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).