Abstract

This systematic review aims to assess the impact of high (>30 Hz) and low (≤30 Hz) frequency vibrations on orthodontic tooth movement (OTM). Several articles were collected through a systematic search in the databases MEDLINE and SCOPUS, following PRISMA methodology and using a PICO question. Relevant information on selected articles was extracted, and the quality of each study was assessed by the quality assessment tools EPHPP, ROBINS-1 and STAIR. Out of 350 articles, 30 were chosen. Low-frequency vibrations did not seem to accelerate OTM with aligners or fixed appliances, despite some positive outcomes in certain studies. Conversely, high-frequency vibrations were linked to increased aligner change, tooth movement, and space closure with fixed appliances. In vivo studies reported favourable results with high-frequency vibrations (60 Hz to 120 Hz), which stimulate bone biomarkers, facilitating alveolar bone remodelling. The results suggest that high-frequency vibration effectively speeds up orthodontic tooth movement, showing promise in both in vivo and clinical studies. Larger-scale research is needed to strengthen its potential in orthodontics.

1. Introduction

The so-called “perfect” smile is a result that can be obtained by combining several dental disciplines such as orthodontics, surgery, and prosthetics. Before reaching this famous smile, it is necessary, in most cases, to manage one of the most common problems: malocclusion. This deviation of the closure is, in more than a quarter of teenagers, the cause of aesthetic and functional problems that can have an impact on the quality of life. Therefore, it is important to correct this malocclusion with fixed or removable orthodontic treatment [1]. The duration of an orthodontic treatment is approximately 24 months, varying according to each clinical case [2]. An excessively long treatment will have a negative impact on the patient since it requires control of meals, particular attention to hygiene, regular appointments, and cost. Also, it will have a negative impact on the environment of the tooth, which may cause periodontal diseases or root resorptions [2,3].

Over the years, reducing the duration of orthodontic treatment has become a very important requirement, not only for the patient but also for the orthodontist. In fact, reducing the treatment time can decrease the risk of adverse effects, exposure to associated risks, and cost, and, most importantly, increase patient satisfaction [2,3].

The rate of orthodontic tooth movement (OTM) is the primary factor in reducing treatment time. To shorten treatment time, it is necessary to accelerate OTM and to act on the environment of the teeth, especially the alveolar bone and the periodontal ligament (PDL), which are two structures that ensure stability [2]. Remodelling the alveolar bone and PDL, due to an inflammatory process in response to orthodontic force, promotes cellular and molecular changes. This characterizes the biological process referred to as OTM [4]. Bone cells, namely osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, are the main targets of non-surgical interventions to accelerate OTM [1].

Tooth movement results from the resorption and formation of alveolar bone in response to tension and compression caused by orthodontic forces from braces or aligners. These forces induce pressure on the PDL, triggering vascular changes that release pro-inflammatory molecules, such as interleukin (IL)-1ß, enhancing osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation, and accelerating tooth movement [5,6]. The use of vibration may accelerate OTM by increasing the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANKL) expression in the periodontal ligament, without additional harm to periodontal tissues, such as root resorption [7]. Direct measurement of RANKL and osteoprotegerin (OPG) levels can provide valuable insights into the osteoclastogenic response to vibration [8]. Vibration could enhance prostaglandin E2 and RANKL effects on human periodontal ligament cells, likely mediated by the cyclooxygenase pathway [9]. It also synergistically boosts osteoclastogenesis and activity via nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation, leading to alveolar bone resorption and accelerated tooth movement, particularly under continuous static force [10]. Additionally, it could promote differentiation of human PDL cells by increasing type I collagen, runt-related transcription factor 2, and Osterix growth factors [9].

Over the decades, there have been great advances in techniques developed to accelerate the rate of orthodontic tooth movement, both surgical and non-surgical [11,12,13,14].

Vibratory stimuli are an example of a non-surgical method and are most often preferred by patients. There are commercially available devices, such as the AcceleDent® device introduced by MAO in 2006, the aim of which is to accelerate OTM by enhancing bone remodelling through pulsed forces with low-frequency mechanical vibration (LFMV) at 30 Hz, 20 min per day [15]. Another commercial device, but with high-frequency mechanical vibration (HFMV), is the VPro5® device at 120 Hz, 5 min per day [16]. These appliances are easy to use, portable, and can be used in conjunction with fixed appliances and aligners.

Recently, many studies have investigated the effects of vibration. Nevertheless, the methodological heterogeneity and the mostly inconclusive results may cause difficulties in the final positioning of this method, which is still under discussion [3].

Indeed, a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of vibration in accelerating orthodontic tooth movement in both animals and humans is warranted. Animal studies offer better control over the stimulation level, allowing researchers to establish the efficacy of vibration treatment more conclusively. In contrast, clinical studies face challenges in controlling the level of stimulation on individual teeth, potentially leading to inconsistent outcomes.

Therefore, this work aims to assess the exposure of high (>30 Hz) and low (≦30 Hz) frequency vibration stimuli on orthodontic movement acceleration in patients and animals with an orthodontic force.

2. Materials and Methods

To carry out this systematic review, the PRISMA methodology (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) 2015 checklist was used [17]. This study was submitted and accepted in the PROSPERO database (CRD42024535048).

The “PICO” methodology was used to answer the research question. This methodology is suggested to be more precise and specific in the research.

The PICO framework for this study is outlined as follows:

- P (Population): Orthodontic patients/animals with an orthodontic force.

- I (Intervention or Exposure): Exposure to high (>30 Hz) or low (≦30 Hz) frequency vibration.

- C (Comparison): Patients/animals who underwent orthodontic treatment with and without vibration stimuli.

- O (Outcomes): OTM by measuring the distance at several points over time intervals.

2.1. Research Strategy and Selection Process

The search strategy for this systematic review was conducted using the following MeSH Terms: ((orthodontics OR “orthodontic tooth movement” OR “tooth movement”) AND (vibration OR “high frequency vibration” OR “low frequency vibration”))

The research on MEDLINE and SCOPUS was conducted in April 2024.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were as follows.

Inclusion criteria:

- Clinical studies and in vivo studies.

- Vibration combined with orthodontic treatment / orthodontic force.

- Orthodontic treatment with aligners and fixed appliance.

Exclusion criteria:

- Review or meta-analysis, case studies and conference proceedings.

- In vitro studies.

- Articles not in English.

- Combination of vibration with surgical techniques or other stimulation method.

- Numerical simulation studies.

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction

The data extraction process was conducted by two researchers (S.P. and S.O.) who independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of relevant studies. The studies that did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were removed. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The full texts of the remaining studies were assessed, and their eligibility criteria were judged. The studies that met the eligibility criteria were included in this systematic review. Data from the selected articles were extracted, and the accuracy of the extraction was verified. The information gathered includes authors’ names, publication year, study type, population, study groups, orthodontic appliances used, location of teeth and desired movement, vibration protocols, results, and conclusions.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality assessment of selected studies was carried out. For clinical studies, the tool Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) [18] was applied for randomized controlled trials, while the tool Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) [19] was employed for non-randomized trials. For in vivo studies, the Stroke Therapy Academy Industry Roundtable (STAIR) recommendations [20] were used.

3. Results

3.1. Search Strategy

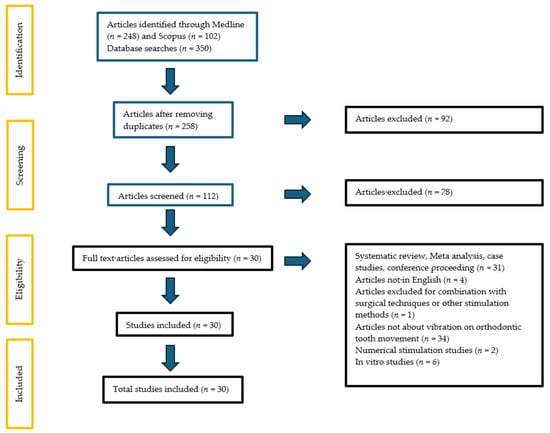

As a result of this research, 350 articles were retrieved, and 92 duplicate records were removed. After reading the titles and abstracts of the remaining 258 studies, 112 relevant articles were selected for full-text reading. After full reading, 78 studies were excluded according to the exclusion criteria. There were 30 studies included in this systematic review. Of the included studies, 25 studies were clinical studies and five were in vivo studies. The PRISMA flow diagram is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Quality Assessment

Table 1.

Quality assessment data for animal studies, using the STAIR preclinical recommendations [20].

Table 2.

Quality assessment data for clinical trials, using the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool [18].

Table 3.

Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) [19].

Concerning the STAIR quality assessment, regarding sample size, 60% of the studies had a moderate final decision and 40% had a weak final decision. Regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria and allocation concealment, 100% of the studies had a weak final decision. Regarding randomization, 60% of the studies had a weak final decision and 40% had a strong final decision. Regarding the reporting of animals excluded for analysis, only one study was concerned and had a moderate final decision. Regarding blind assessment of outcome, 60% of studies had a weak final decision, 20% a moderate final decision, and 20% a strong final decision. Regarding reporting of potential conflicts of interest and study funding, 80% of studies had a moderate final decision and 20% had a strong final decision.

Among the 18 randomized clinical trials, the quality of 14 studies was classified as “strong” (78%), while four studies presented a moderate quality assessment (22%).

The quality of seven non-randomized clinical trials was assessed with the ROBINS-I tool. Three studies (43%) were considered to have an overall methodological quality score of “Low”, two studies (29%) presented “some concerns”, and another two studies (29%) were scored as “high”.

3.3. In Vivo Studies

The characteristics of the included in vivo studies are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Table of results of selected in vivo studies [19].

The applications of vibration with orthodontic treatment to accelerate tooth movement have been evaluated through animal studies with no positive outcomes, except one study [24] that reported that vibration can be used to improve the rate of tooth movement during the catabolic phase of treatment.

Levels of stimulation with frequency vibration up to 30 Hz [21,22,24] did not show a significant increase in the rate of OTM. On the other hand, frequencies of 60 Hz, 70 Hz, and 120 Hz had more positive effects, improved OTM [7,23,24], and increased biomarkers of the bone [7,23]. Vibration stimulation was applied between 3 min to 30 min.

Only two studies [7,23] have reported the impact of vibration on root resorption. These studies showed that high-frequency vibration did not affect root resorption.

Out of five animal studies, three were conducted on rats: two [22,23] Wistar (50%) and two [21,24] Sprague Dowley (33%) and one [22] CD1 rats (17%).

The effect of vibration on root resorption was only analyzed in two studies. Both studies evaluated root condition with fixed appliances: one study [38] with HFMV and the other study [40] with LFMV. Both studies reported that root condition was not affected after vibration application.

All studies evaluated maxillary first molar movement to study the acceleration of OTM.

3.4. Clinical Studies

The characteristics of the included clinical studies are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Table of results of selected clinical studies [19].

Out of 25 human studies, 18 [5,8,25,26,27,28,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,47] were randomized controlled trials and seven [16,41,42,43,44,45,46] were non-randomized clinical trials. Six [5,25,28,30,39,41] were split-mouth studies.

This study comprised 1053 patients who needed orthodontic treatment.

Nineteen [5,8,25,26,27,28,30,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,47] used fixed appliance as orthodontic appliance, five [16,31,35,45,46] used aligners, and only one [43] used both.

Fourteen [26,31,32,34,35,36,37,39,40,42,43,44,46,47] studies used AcceleDent® as an intervention tool, two [16,45] studies used VPro5®, four [5,8,25,30] used an electric toothbrush, and five [27,28,33,38,41] used a customized device. All included daily application. Studies that reported low vibration [8,26,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,42,43,44,46,47] used a frequency of 30 Hz, 20/min day; high-frequency vibration [5,8,16,25,27,30,38,41,45] ranged between 50 and 125 Hz. Only one [8] study explored both types of frequency vibration.

Thirteen [5,8,25,28,30,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41] studies observed the rate of teeth retraction, four [27,42,44,47] studies observed anterior alignment, three [16,32,43] studies treatment time, four [31,35,45,46] studies aligner replacement; four [5,8,16,26] studies also included biomarkers of bone remodeling, and six [27,31,37,38,40,46] studies also evaluated pain. Seventeen [8,25,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,46,47] out of twenty-five human studies found no significant differences regarding the acceleration of tooth movement with vibration.

Only three studies [42,43,44] with LFMV showed positive results regarding OTM, with increased movement and tooth alignment.

In nine [5,8,16,25,27,30,38,41,45] articles that used HFMV, four [8,25,27,41] did not find significant results regarding OTM acceleration. Two studies [16,45] with a frequency vibration at 120 Hz related a decrease regarding aligners exchange with a decrease in the number of aligners to complete treatment. Regarding the amount of total space closure and canine distalization, one study [30] with vibration frequency at 50 Hz and another [38] at 102 Hz showed increased results.

4. Discussion

The professional’s role is to support patients by combining aesthetics with effective orthodontic treatment, and the duration of treatment is becoming increasingly important. As such, in recent years, non-surgical techniques that can be applied at home by the patient with professional recommendations have emerged, such as high or low mechanical vibrations [47]. This alternative technique based on mechanical vibrations is used to increase the rate of orthodontic movement by accelerating periodontal and alveolar bone remodeling [5].

4.1. Effects of Supplemental Low-Frequency Vibration on Dental Movement in Humans

Regarding our selected studies, only three reported orthodontic treatment with aligners. Katchooi et al. (2018) [31] and Lombardo et al. (2019) [35] both used the AcceleDent® device with the application according to the manufacturer’s instructions; both concluded that there are no significant effects on the aligner’s regimen times with vibration. However, Bilello et al. (2022) [46], in a similar study did not understand if the acceleration of treatment time could be attributed to the use of AcceleDent® or the change regimen of the aligners.

Regarding fixed appliances, there is no benefit of vibration in the rate of mandibular space closure, in the duration of treatment and the result [33,36].

Some studies found no statistically significant differences between the groups in the rate of retraction of the maxillary canines [8,28,37,39,40]. In agreement with these results, Telatar et al. (2021) [34] observed in their study in the experimental group (vibration with fixed appliance), the average rate of tooth movement for the lower canines was 1.09 mm per month and 1.24 mm per month for the upper canines, and in the control group (only fixed appliance), the average rate of tooth movement for the lower canines was 1.06 mm per month and 1.06 mm per month for the upper canines; they concluded that canine retraction rates were not different between groups.

Orton-Gibbs (2015) [43] and Bowman (2016) [44] concluded that orthodontic tooth movement and treatment time increased with fixed appliances and AcceleDent®. Bowman (2014) [42] found that combining fixed appliances with LFMV from devices like AcceleDent® resulted in a 30% faster treatment duration compared to fixed appliances alone, and another similar study [44] with low frequencies detected a decrease in the number of days to achieve a molar Class I. Orton-Gibbs (2015) [43] reported similar findings, suggesting a significant reduction in treatment duration when using AcceleDent®. However, Miles (2018) [32] found no significant difference in treatment duration between the AcceleDent® group and the control group. The existing commercial intraoral vibration device comes with a standard mouthpiece, delivering vibration to teeth primarily through their contact with it. Analysis [48] using finite element methods on this device, under optimal occlusion conditions, reveals an uneven distribution of force over the teeth, with anterior teeth experiencing more stimulation than posterior ones. This force distribution also varies depending on the stiffness of the mouthpiece and individual contact conditions, as each patient’s teeth profile differs in terms of height and angulation. Moreover, if the mouthpiece is not perfectly aligned, some teeth may not receive any stimulation at all. Insufficient dosage and inconsistently targeted delivery can hinder desired biological responses, contributing to the inconsistency in clinical outcomes observed.

ElMotaleb et al. (2024) [40], Taha et al. (2020) [37], and Katchooi et al. (2018) [31] reported pain during orthodontic treatment with low vibration and did not find significant effects on pain reduction.

From a biological point of view, Siriphan et al. (2019) [8] concluded that additional vibratory forces did not improve the rate of tooth movement or the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Analysis of saliva biomarkers during orthodontic treatment with vibratory stimuli revealed an increase in certain biomarkers like IL-11 and MMP-9 in the control group but not in the group using AcceleDent®, suggesting a potential dampening effect on inflammatory response and tooth movement inhibition [26]. Overall, while supplemental vibratory forces show promise in accelerating orthodontic treatment in some studies, others suggest that their effectiveness may vary, depending on factors such as initial tooth irregularity and individual biological responses.

Low-frequency vibration (≦30 Hz) does not appear to accelerate OTM, even though in some studies, it had beneficial effects.

4.2. Effects of Supplemental High-Frequency Vibration on Dental Movement in Human Patients

Few studies [16,45] showed that high-frequency vibration increased orthodontic tooth movement acceleration with aligners. Shipley et al. (2019) [16] observed an increase in aligner change and tooth movement with VPro5® and, consistent with these results, in another study, Shipley (2018) [45], with the same device, observed an increase of 66% in aligner exchanges and an increased number of aligners to complete treatment.

Some studies [5,30,38] showed that high-frequency vibration increased orthodontic tooth movement acceleration with fixed appliances. Studies by Liao et al. (2017) [30] and Mayama et al. (2022) [38], at 59 Hz and 102 Hz, respectively, demonstrated that the use of supplemental HFMV with fixed appliances led to increased total space closure and canine distalization, indicating that localized high-frequency vibrations can accelerate tooth movement. Nevertheless, it is important to consider the time taken to reach the working wire, as the decision of when to place the next archwire and not waiting for it to be completely passive. In contradiction to these findings, Azeem et al. (2019) [25], Siriphan et al. (2019) [8], and Akbar et al. (2022) [41] did not find statistically significant differences in the amount of canine retraction with fixed appliances. In these studies, toothbrushes were used and the application was only at one point; it may be possible that the direction of vibration application could be an important factor. Another important factor in the application of vibration with fixed appliances is the fact that the arch passes through all the teeth, and if the vibration is applied at a single point, more of the effect is distributed through all the other teeth. As opposed to the treatment with aligners, the vibration is applied without any orthodontic appliance in the mouth, which limits the vibration to only one location without dissipation; the dissipation with fixed appliances also depends on the type of brackets used and the characteristics of the arch.

Two [27,38] studies reported pain during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances in conjunction with high vibration and did not find significant effects on pain reduction.

Regarding the biological perspective, Leethanakul et al. (2016) [5] studied gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) to assess the response of the tissue to HFMV stimuli from an electric toothbrush. The concentration of the various components of GCF can increase when subjected to vibratory stimuli such as an electric toothbrush. Indeed, the levels of IL-1ß, one of the components of GCF, increase with the additional application of vibratory stimuli during orthodontic treatment. IL-1ß is directly involved in bone resorption since it induces the expression of RANKL in osteoblasts and PDL cells and stimulates osteoclastic precursor differentiation. In this study, IL-1ß levels would be three times higher with additional vibratory force compared to ortho forces alone. This confirms that there is a biological response to the addition of a vibratory stimulus during orthodontic treatment. Therefore, vibration plus orthodontic force increased levels of IL-1ß in the GCF, as well as bone resorption, accelerating the orthodontic movement.

High-frequency vibration consistently appeared to accelerate OTM, although the studies included in this review had a small sample size.

4.3. Effects of Supplemental Vibration on Dental Movement in In Vivo Studies

Animal studies demonstrate greater consistency compared to clinical studies due to the ability to exert better control over vibrational force. In these studies, vibrational forces are directly administered to the tooth with adjustable intensity, ensuring a more precise and uniform application of force.

Nishimura et al. (2008) [7] conducted a study applying various resonant frequencies, averaging around 61 Hz, to rats. They observed an average displacement of the first molars at about 0.0014 mm with a velocity of approximately 0.27 mm/second. The study found that tooth movement scale was about 15% higher in the experimental group compared to the control group. Biologically, the experimental group exhibited more multinuclear osteoclasts in the alveolar bone, suggesting a potential link between the number of osteoclasts and the speed of tooth movement. Vibrations stimulated monocyte/macrophage differentiation and increased RANKL expression in PDL osteoclasts and fibroblasts, potentially activating osteoclasts and promoting alveolar bone remodeling.

Takano-Yamamoto et al. (2017) [23] also concluded that vibration resonance had a stimulatory effect on tooth movement speed without negatively impacting tissue. Their study showed that HFMV during dental movement increased the activation of the NF-K B cell signaling pathway in osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. This activation, in turn, enhanced osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast function, leading to accelerated tooth movement through alveolar bone resorption.

Alikhani et al. (2018) [24] investigated the effects of anti-inflammatory drugs on high-frequency acceleration and the role of PDL in orthodontic movement. They found that high-frequency acceleration increased the rate of tooth movement during the catabolic phase and facilitated retention during the anabolic phase of remodeling at the end of treatment. The release of inflammatory mediators in the ligament seemed to play a crucial role in accelerating orthodontic movements.

These studies [7,23,24] showed good results with high-frequency vibration, ranging from 60 Hz to 120 Hz.

In contrast, studies such as Kalajzic et al. (2014) [21] and Yadav et al. (2015) [22] showed differing results regarding the efficacy of LFMV on tooth movement. Kalajzic et al. (2014) [21] noted a smaller distance between molars in the group with fixed appliances with vibration, suggesting that LFMV might inhibit dental movement. Yadav et al. (2015) [22] found that LFMV had no effect on increasing molar displacement in rats and did not increase the number of osteoclasts in teeth not subjected to mechanical forces. They proposed that the alignment of PDL fibers on the tension side during tooth movement might be impaired in rats, affecting osteoclast activation and tooth movement completion. Both studies used low-frequency vibration ranging between 30 Hz and 5 Hz.

4.4. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

Some limitations of our study should be highlighted. Not all studies had the same number of patients evaluated, which may distort the results and comparisons between each study. In addition, not all studies used the same vibration device, and, consequently, the same stimulation parameters, which may introduce variability in the results, and, consequently, there is insufficient evidence to support these conclusions. Clinical studies are based on trust between the practitioner and the patient. In fact, the vibratory forces are transmitted to the patient by the patient, which can be problematic as it is influenced by the seriousness of the patient. Only one [26] study reported on patient compliance to the use of the vibration device, concluding that the average compliance rate was 53% and that adherence time decreased throughout treatment. The number of in vivo studies conducted was limited, which weakened the strength of the evidence obtained. Additionally, studies with a high frequency of occurrence included small sample sizes.

Regardless of these limitations, our findings can be used to shape future studies on vibration application in the orthodontic field. This systematic review includes not only animal studies but also clinical studies, providing a broader perspective on the effects of vibration in the OTM, which can aid researchers and clinicians in increasing the clinical performance of this adjunctive therapy. Since vibration is commonly applied at low or high frequency, we have analyzed both modalities, showing that HFMV may be preferred to LFMV in accelerating OTM.

5. Conclusions

Vibration is a non-invasive technique that has been gaining attention in recent years. Whether below 30 Hz (LFMV) or above (HFMV), vibration frequencies are applicable in combination with fixed braces but also with aligners, which makes them practical and modern. Our findings showed that in both in vivo and clinical studies, high-frequency mechanical vibration showed promising evidence in accelerating orthodontic tooth movement and may be preferred to low-frequency mechanical vibration. Since studies have shown conflicting results, further research is required in this field, with more precise and rigorous stimulation parameters and larger sample sizes, to better understand the mechanisms of vibration frequencies and their role in OTM. In addition, future studies in the field must investigate optimal vibration protocols (in terms of, e.g., dose, time, the application technique) to address specific types of movement and teeth. The development of customized and programmable stimulation devices designed in a way to specifically stimulate the required direction of movement could also constitute an optimized solution to achieve an effective OTM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., S.O., M.A., Ó.C. and T.P.; methodology, S.P. and S.O.; validation, J.P., Ó.C. and T.P.; formal analysis, S.P. and S.O.; data curation, S.P., S.O., M.A. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, S.P., S.O. and T.P.; supervision, T.P. Final revision, S.P., S.O. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable to a systematic review. The review protocol was registered with the Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with registration number CRD42024535048.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this review can be found within this article, as the authors used published data sets.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- El-Angbawi, A.; McIntyre, G.T.; Fleming, P.S.; Bearn, D.R. Non-surgical Adjunctive Interventions for Accelerating Tooth Movement in Patients Undergoing Fixed Orthodontic Treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2016, CD010887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacprzak, A.; Strzecki, A. Methods of Accelerating Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Review of Contemporary Literature. Dent. Med. Probl. 2018, 55, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, D.; Xiao, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z. The Effectiveness of Vibrational Stimulus to Accelerate Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, I.; dos Santos Sousa, A.B.; da Silva, G.G. New Therapeutic Modalities to Modulate Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2014, 19, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leethanakul, C.; Suamphan, S.; Jitpukdeebodintra, S.; Thongudomporn, U.; Charoemratrote, C. Vibratory Stimulation Increases Interleukin-1 Beta Secretion during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoal, S.; Gonçalves, A.; Brandão, A.; Rocha, D.; Oliveira, S.; Monteiro, F.; Carvalho, Ó.; Coimbra, S.; Pinho, T. Human Interleukin-1β Profile and Self-Reported Pain Monitoring Using Clear Aligners with or without Acceleration Techniques: A Case Report and Investigational Study. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 8252696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, M.; Chiba, M.; Ohashi, T.; Sato, M.; Shimizu, Y.; Igarashi, K.; Mitani, H. Periodontal Tissue Activation by Vibration: Intermittent Stimulation by Resonance Vibration Accelerates Experimental Tooth Movement in Rats. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriphan, N.; Leethanakul, C.; Thongudomporn, U. Effects of Two Frequencies of Vibration on the Maxillary Canine Distalization Rate and RANKL and OPG Secretion: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2019, 22, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjakul, S.; Leethanakul, C.; Jitpukdeebodintra, S. Low Magnitude High Frequency Vibration Induces RANKL via Cyclooxygenase Pathway in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells in Vitro. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2019, 9, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhani, M.; Lopez, J.A.; Alabdullah, H.; Vongthongleur, T.; Sangsuwon, C.; Alikhani, M.; Alansari, S.; Oliveira, S.M.; Nervina, J.M.; Teixeira, C.C. High-Frequency Acceleration. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, S.; Oliveira, S.; Monteiro, F.; Padrão, J.; Costa, R.; Zille, A.; Catarino, S.O.; Silva, F.S.; Pinho, T.; Carvalho, Ó. Influence of Ultrasound Stimulation on the Viability, Proliferation and Protein Expression of Osteoblasts and Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.; Monteiro, F.; Oliveira, S.; Costa, I.; Catarino, S.O.; Carvalho, Ó.; Padrão, J.; Zille, A.; Pinho, T.; Silva, F.S. Optimization of a Photobiomodulation Protocol to Improve the Cell Viability, Proliferation and Protein Expression in Osteoblasts and Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts for Accelerated Orthodontic Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordente, C.M.; Oliveira, D.D.; Palomo, J.M.; Cardoso, P.A.; Assis, M.A.L.; Zenóbio, E.G.; Souki, B.Q.; Soares, R.V. The Effect of Micro-Osteoperforations on the Rate of Maxillary Incisors’ Retraction in Orthodontic Space Closure: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Prog. Orthod. 2024, 25, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, F.; Padala, S.; Allareddy, V.; Nanda, R. Patients’, Parents’, and Orthodontists’ Perceptions of the Need for and Costs of Additional Procedures to Reduce Treatment Time. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 145, S65–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani-Hani, M.; Karami, M.A. Piezoelectric Tooth Aligner for Accelerated Orthodontic Tooth Movement. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 4265–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, T.; Farouk, K.; El-Bialy, T. Effect of High-Frequency Vibration on Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Bone Density. J. Orthod. Sci. 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, N.; Waters, E. Criteria for the Systematic Review of Health Promotion and Public Health Interventions. Health Promot. Int. 2005, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.; Feuerstein, G.; Howells, D.W.; Hurn, P.D.; Kent, T.A.; Savitz, S.I.; Lo, E.H. Update of the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable Preclinical Recommendations. Stroke 2009, 40, 2244–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalajzic, Z.; Peluso, E.B.; Utreja, A.; Dyment, N.; Nihara, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, J.; Uribe, F.; Wadhwa, S. Effect of Cyclical Forces on the Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone Remodeling during Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Angle Orthod. 2014, 84, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Dobie, T.; Assefnia, A.; Gupta, H.; Kalajzic, Z.; Nanda, R. Effect of Low-Frequency Mechanical Vibration on Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano-Yamamoto, T.; Sasaki, K.; Fatemeh, G.; Fukunaga, T.; Seiryu, M.; Daimaruya, T.; Takeshita, N.; Kamioka, H.; Adachi, T.; Ida, H.; et al. Synergistic Acceleration of Experimental Tooth Movement by Supplementary High-Frequency Vibration Applied with a Static Force in Rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alikhani, M.; Alansari, S.; Hamidaddin, M.A.; Sangsuwon, C.; Alyami, B.; Thirumoorthy, S.N.; Oliveira, S.M.; Nervina, J.M.; Teixeira, C.C. Vibration Paradox in Orthodontics: Anabolic and Catabolic Effects. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeem, M.; Afzal, A.; Jawa, S.A.; Haq, A.U.; Khan, M.; Akram, H. Effectiveness of Electric Toothbrush as Vibration Method on Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Split-Mouth Study. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2019, 24, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, S.; Chouinard, M.C.; Landa, D.F.; Nanda, R.; Chandhoke, T.; Sobue, T.; Allareddy, V.; Kuo, C.-L.; Mu, J.; Uribe, F. Biomarkers of Orthodontic Tooth Movement with Fixed Appliances and Vibration Appliance Therapy: A Pilot Study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2020, 42, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, P.; Smith, H.; Weyant, R.; Rinchuse, D.J. The Effects of a Vibrational Appliance on Tooth Movement and Patient Discomfort: A Prospective Randomised Clinical Trial. Aust. Orthod. J. 2012, 28, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, A.K.; Raghav, P.; Mehra, V.; Wadhawan, A.; Gupta, N.; Phull, T.S. Effect of Customized Vibratory Device on Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Prospective Randomized Control Trial. J. Orthod. Sci. 2022, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, N.R.; DiBiase, A.T.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Johnson, N.; Slipper, C.; Grant, J.; Alsaleh, M.; Cobourne, M.T. Supplemental Vibrational Force Does Not Reduce Pain Experience during Initial Alignment with Fixed Orthodontic Appliances: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Elekdag-Turk, S.; Turk, T.; Grove, J.; Dalci, O.; Chen, J.; Zheng, K.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Swain, M.; Li, Q. Computational and Clinical Investigation on the Role of Mechanical Vibration on Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J. Biomech. 2017, 60, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katchooi, M.; Cohanim, B.; Tai, S.; Bayirli, B.; Spiekerman, C.; Huang, G. Effect of Supplemental Vibration on Orthodontic Treatment with Aligners: A Randomized Trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, P. Does Microvibration Accelerate Leveling and Alignment? A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Orthod. 2018, 52, 342–345. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Batra, P.; Sharma, K.; Raghavan, S.; Srivastava, A. Comparative Assessment of the Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Adolescent Patients Undergoing Treatment by First Bicuspid Extraction and En Mass Retraction, Associated with Low-Frequency Mechanical Vibrations in Passive Self-Ligating and Conventional Brackets: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. Orthod. 2020, 18, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telatar, B.C.; Gungor, A.Y. Effectiveness of Vibrational Forces on Orthodontic Treatment. J. Orofac. Orthop. Fortschritte Kieferorthopädie 2021, 82, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, L.; Arreghini, A.; Ghislanzoni, L.T.H.; Siciliani, G. Does Low-Frequency Vibration Have an Effect on Aligner Treatment? A Single-Centre, Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiBiase, A.T.; Woodhouse, N.R.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Johnson, N.; Slipper, C.; Grant, J.; Alsaleh, M.; Khaja, Y.; Cobourne, M.T. Effects of Supplemental Vibrational Force on Space Closure, Treatment Duration, and Occlusal Outcome: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, K.; Conley, R.S.; Arany, P.; Warunek, S.; Al-Jewair, T. Effects of Mechanical Vibrations on Maxillary Canine Retraction and Perceived Pain: A Pilot, Single-Center, Randomized-Controlled Clinical Trial. Odontology 2020, 108, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayama, A.; Seiryu, M.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Effect of Vibration on Orthodontic Tooth Movement in a Double Blind Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, O.; Yagci, A.; Hashimli, N. Effect of Applying Intermittent Force with and without Vibration on Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J. Orofac. Orthop. Fortschritte Kieferorthopädie 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElMotaleb, M.A.A.; El-Beialy, A.R.; El-Sharaby, F.A.; ElDakroury, A.E.; Eid, A.A. Effectiveness of Low Frequency Vibration on the Rate of Canine Retraction: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Fatima, M. Effects of Vibrations Induced by Electric Tooth Brush on Amount of Canine Retraction: A Cross Sectional Study Done at University of Lahore. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.J. The Effect of Vibration on the Rate of Leveling and Alignment. J. Clin. Orthod. 2014, 48, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orton-Gibbs, S.; Kim, N.Y. Clinical Experience with the Use of Pulsatile Forces to Accelerate Treatment. J. Clin. Orthod. 2015, 49, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowman, S.J. The Effect of Vibration on Molar Distalization. J. Clin. Orthod. 2016, 50, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shipley, T.S. Effects of High Frequency Acceleration Device on Aligner Treatment—A Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2018, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilello, G.; Fazio, M.; Currò, G.; Scardina, G.A.; Pizzo, G. The Effects of Low-Frequency Vibration on Aligner Treatment Duration: A Clinical Trial. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, N.R.; DiBiase, A.T.; Johnson, N.; Slipper, C.; Grant, J.; Alsaleh, M.; Donaldson, A.N.A.; Cobourne, M.T. Supplemental Vibrational Force during Orthodontic Alignment: A Randomized Trial. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.; Wang, D.; Chen, J. Peak Loads on Teeth from a Generic Mouthpiece of a Vibration Device for Accelerating Tooth Movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).