Abstract

Bamboo-derived biochar (BC) is promising for high-salinity wastewater treatment through photothermal evaporation. This study systematically evaluated BCs synthesized at 400–800 °C with residence times of 40 or 70 min. Pyrolysis temperature proved dominant, with 600 °C representing a critical threshold. Below this temperature, BCs maintained high carbon content and polar functional groups but exhibited limited porosity. Above it, structural reorganization enhanced pore development and aromaticity while reducing polar surface groups. Residence time primarily influenced volatile retention, and prolonged pyrolysis led to pore collapse. The optimal BC—produced at 800 °C for 40 min—combined hierarchical porosity with balanced surface chemistry, achieving an evaporation rate of 1.21 kg/m2·h and a photothermal efficiency of 70.45% under high-salinity conditions. Mechanistic analysis indicates that short, high-temperature pyrolysis preserves structural integrity and interfacial activity with minimal energy input. These results establish a thermal processing approach that reconciles carbon stability with surface functionality, offering practical guidance for scaling efficient and sustainable biochar-based wastewater treatment systems.

1. Introduction

Solar energy is one of the most abundant energy sources on Earth, with an average daily solar radiation of EJ received during Earth’s rotation cycle [1]. With the continuous expansion of industries, the generation of high-salt wastewater is increasing at a rate of 2% per year [2]. Solar surface photothermal evaporation technology is a new type of photothermal evaporation technology, which integrates photothermal material to the surface of a water source for thermal conversion and limits thermal energy to the air/liquid interface to realize liquid low-temperature evaporation [3].

At present, the relevant photothermal evaporation materials mainly include carbon-based, metal-based, semiconductor, and organic polymer materials [4]. Carbon-based materials are characterized by low cost, wide availability, good light absorption, and chemical stability [5]. However, they exhibit poor mechanical properties. Metal-based materials [6] such as gold, silver, and copper are characterized by high photothermal conversion efficiency (PTE), excellent electrical conductivity, and good mechanical properties. Nevertheless, they are costly and may corrode under specific environmental conditions. The costs of semiconductor materials vary [7]. These materials possess unique optoelectronic properties, and their performance can be optimized by adjusting their structures. However, they have a high recombination rate of photogenerated carriers. Organic polymer materials are highly designable and flexible [8], with a wide cost range. However, they suffer from relatively poor thermal and chemical stability.

Among various photothermal materials [4,9,10], charcoal-based photothermal materials have a broader wavelength absorption range, better processability, and are more easily prepared into porous structures to achieve higher photothermal evaporation rates compared to precious metals and semiconductors. Biochar is a highly efficient carbon-based photothermal material due to its natural vertically aligned microporous structure in the growth direction [11], which can promote water transport during photoevaporation [12,13,14], and exhibit high photoevaporation rates in photoevaporation of high-salt wastewater [15].

The hydrophilicity of bamboo charcoal is a key factor in enabling photothermal evaporation, and the factors affecting the hydrophilicity of bamboo charcoal materials include the porous structure and the surface chemical properties. WANG et al. [16] improved the hydrophilicity and antimicrobial properties of bamboo charcoal through chemical modification, such as the introduction of amino oxide groups. ZHANG et al. [12] used bamboo waste-activated carbon as the raw material to study the activation of raw materials and water vaporization. The porous structure of photothermal materials is crucial due to their light absorption, photothermal conversion, and evaporation rates. SHEN et al. [17] showed that surface pore structures enhance solar energy absorption in hydrogel photothermal materials. Lou et al. [18] developed graphene foams with a multiscale pore structure, achieving a PTE of 93.4%. Similarly, Hu et al. [19] fabricated highly porous carbon nanotube/graphene photothermal materials using 3D printing technology. Therefore, the porous structure and porosity of photothermal materials have a great influence on photoevaporation efficiency.

In the photothermal evaporation process of high-salt wastewater, high concentrations of salt ions can block the surface and internal pores of bamboo charcoal (BC), leading to a reduction in specific surface area and pore volume [20,21]. However, the mechanisms by which salt and complex organic matter interact with photothermal materials, and how these interactions affect light absorption, PTE, and photoevaporation rate over extended evaporation periods, remain unclear. Hama [22] focuses on the application of modified biochar for removing organic dyes from wastewater. This research covers aspects like preparation, modification, and underlying mechanisms. However, there is a notable lack of studies dealing with the issues regarding bamboo charcoal as a photothermal evaporation material.

Therefore, it is important to understand how BC, salt, and organic matter interact during photothermal evaporation to maintain a stable light absorption rate, PTE, and photoevaporation rate over time.

In this work, BC was prepared using bamboo as a raw material, and the evaporation rate and PTE under the optimal preparation conditions of BC were explored using BC species (BC-s) and an evaporation solution system (deionized water, NaCl solution, glucose solution, and NaCl/glucose mixture solution) as variables, respectively.

While BC demonstrates significant potential in industrial water treatment and sustainable energy applications—particularly due to its high PTE for hypersaline wastewater purification and solar desalination in sectors like textiles, food processing, and water-scarce coastal regions [23,24,25,26,27,28]—its scalability remains constrained by persistent challenges.

The integration of BC into solar-driven evaporation systems enables energy-efficient freshwater production and supports water recycling initiatives [29], yet prolonged exposure to high-salinity environments accelerates salt crystallization within BC’s porous structure, compromising its long-term stability and evaporation performance [30]. Furthermore, energy-intensive pyrolysis processes required to optimize BC’s carbon content and porosity increase production costs [31], while retrofitting existing infrastructure with BC-based photothermal systems demands substantial capital investments and operational adaptation. Chemical modifications to enhance hydrophilicity (e.g., NaOH treatments) further risk secondary pollution if not meticulously managed.

This work provides a comprehensive investigation that advances the field in three key aspects. First, it systematically decouples and examines the combined effects of two critical pyrolysis parameters—temperature and residence time—on the structure and performance of bamboo-derived biochar, establishing a clear framework. Second, it mechanistically reveals the trade-off between enhanced graphitization and the loss of polar surface groups with increasing temperature, identifying approximately 600 °C as a pivotal threshold for this transition. Third, it rigorously evaluates the application potential in the challenging context of high-salinity wastewater, not only identifying the optimal material (BC 800-40) but also assessing its operational stability under concentrated brine conditions. The findings offer a critically evaluated material candidate and practical guidance for designing efficient and stable solar evaporators for harsh saline environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Sodium hydroxide (NaOH 10M in ) and hydrofluoric acid (HF 48–55% w/w in water) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Glucose (C6H12O6) was purchased from Shanghai Maclean’s Biochemical Science and Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Sodium chloride (NaCl ≥ 99.5% (AT), sodium bromide (KBr AR, 99%), and acetone (), anhydrous ethanol (99.5%), methyl orange (MO, 99%) were purchased from Shanghai Titan Technology Co. (Shanghai, China); and deionized water was used for the test.

2.2. Material Preparation

The bamboo slices were obtained from Anqing, Anhui Province, China, with a cross-sectional area of L(length) × W(width) = 22 mm × 5 mm. Prior to preparation, they were soaked and washed with deionized water, then dried at 70 °C for 24 h to obtain the raw material to produce biochar. The bamboo slices were placed into a square crucible of high-temperature-resistant ceramic and heated to the desired temperature (400–800 °C [20,32]) in a tube furnace at a heating rate of 5 °C/min and a nitrogen N2 flow rate of 3 mL/min. They were then held at the desired temperature for 40–70 min to carry out continuous pyrolysis. Once the pyrolysis process was complete, the bamboo charcoal was cooled to room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere (N2 flow rate of 3 mL/min) and subsequently removed [19]. The resulting bamboo charcoal powder was obtained by grinding and passing through a 200-mesh sieve. The heating temperatures were 400, 600, and 800 °C, and the pyrolysis times were 40 and 70 min. These samples were designated BC 400-40, BC 400-70, BC 600-40, BC 600-70, BC 800-40, and BC 800-70.

2.3. Experiment

The photothermal evaporation performance was evaluated under controlled conditions to benchmark and assess practical applicability. A standard illumination intensity of 1 kW m−2 (1 sun) was adopted to enable direct comparison with prevalent studies in solar-driven evaporation. The saline feed solution was prepared at a high concentration of 2.5 mol L−1 NaCl to simulate the challenging conditions of industrial hypersaline wastewater, thereby probing the material’s potential for real-world applications. The loading of BC in the evaporation layer was fixed at 0.2 g (unless specified otherwise for control experiments), as preliminary tests identified this quantity as the optimal balance between maximizing light absorption, maintaining efficient water transport, and ensuring long-term operational stability.

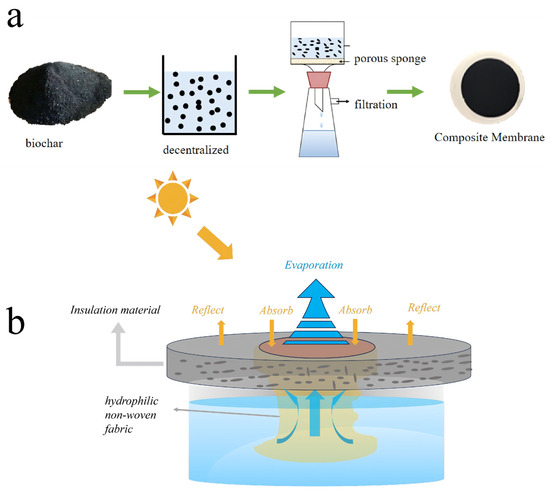

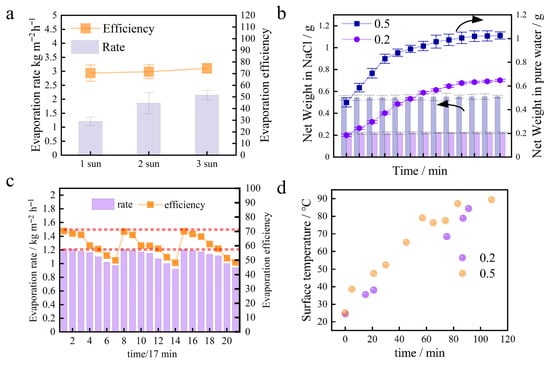

As shown in Figure 1a, the BC powder was first ground by a ball mill, sieved through a 200-mesh sieve, and dispersed in an ethanol solution. A hydrophilic porous sponge (diameter: 4 cm; pore size: 0.05 mm) served as the supporting substrate. The BC dispersion was then deposited onto the sponge via vacuum filtration using a Whatman system equipped with a vacuum pump (Shanghai Lichen Bangxi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China), forming a dense, continuous, and porous evaporation layer.

Figure 1.

(a) Preparation of BC photothermal conversion porous interfacial solar evaporator. (b) Schematic diagram of evaporator.

A hydrophilic non-woven fabric, which exhibits excellent water transport properties due to its fibrous capillary structure, was placed between this evaporation layer and the underlying water reservoir. During evaporation, this fabric continuously wicks the solution upward, effectively wetting the internal pores of the evaporation layer and enabling localized interfacial evaporation without direct contact with the bulk solution. The insulation layer remained tightly adhered to the evaporation layer throughout the experiments. No detachment of carbon particles or their dispersion into the aqueous phase was observed during prolonged evaporation tests, confirming the structural stability of the evaporator.

Finally, the assembled sample was dried to yield the BC-based porous interfacial solar evaporator. As shown in Figure 1b, the evaporator was placed on top of a beaker containing the feed solution. Here, the hydrophilic non-woven fabric acted as a capillary water channel, directing the solution from the reservoir to the evaporation surface for photothermal evaporation. A xenon lamp was used as a simulated solar light source at 1 sun intensity (1 kW/m2). The solar-water vapor evaporation rate and energy conversion efficiency were calculated according to the following equations:

where is the rate of evaporation, ; is the initial mass, ; is the mass after a certain time of light, ; is the area of evaporation, ; and is the time, . Photothermal conversion efficiency [33] is calculated by

is the evaporation rate [34] to reach steady state, ; is the light power ; and is the latent heat of vaporization [35] is calculated by

where is the initial temperature of the evaporator surface before light exposure °C, and is the stabilized temperature of the evaporator surface after light exposure °C [36].

2.4. Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to characterize the surface morphology of BC, which was subjected to a drying process at 70 °C for a duration of 2 h. The BC was cut with a knife in two distinct orientations: one aligned with the direction of bamboo growth and the other perpendicular to it. The resulting surfaces were then observed using a SEM electron microscope with an applied voltage of 5 kV, model: JSM-7900F. The pore structure, porosity, and pore size distribution of BC were analyzed using graphical methods. The BC powder was laid flat on a diffraction stage, and diffraction was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD), model: DX-2700. Compositional analysis of BC powder was carried out using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), model: Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+. Functional group analysis was carried out with Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), model: IRAFFINITY-1. We used a contact angle tester to analyze the hydrophilicity of BC, model: SDC-200S. Size: dimensions were above 800 mm (length) × 190 mm (width) × 640 mm (height).

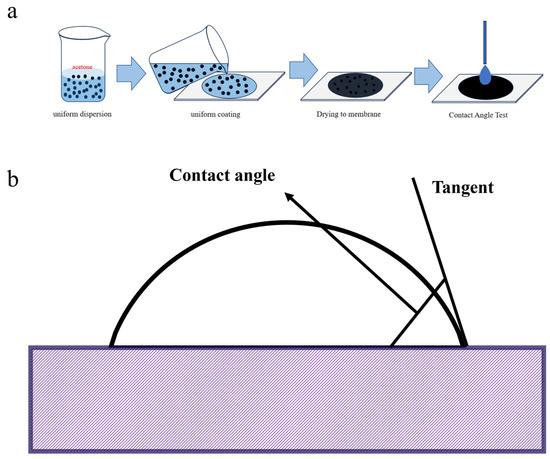

Related reports indicate that BC is hydrophobic at low temperatures and hydrophilic at high temperatures [37]. In the contact angle test, a solid–liquid dispersion system was used, in which 0.5 g of BC powder was uniformly dispersed in 5 mL of acetone, the volatility of which avoids any effect on the hydrophilicity of BC after dispersion. As shown in Figure 2a, the mixed BC/acetone turbid solution was mixed in the LC-600B ultrasonic apparatus for 15 min, and the mixed BC/acetone turbid solution was evenly coated on the glass slice with a flat surface. The contact angle test was carried out after it was dried at room temperature (Figure 2b). The instrument used was a CA100B auto-sampling contact angle tester, the dropping liquid was deionized water, and the shooting parameter was 6 s/300 frames.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of contact angle test. (b) Contact angle test flow.

In testing the fixed carbon content of BC, 5 g of BC was weighed into a powder of 200-mesh-size particles with an MCS-51 electronic balance. The ash content of BC was obtained by dry combustion in a KSL-1400X programmed temperature-controlled muffle furnace at a temperature of 550 ± 10 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and the ash content of BC was obtained when the BC was sufficiently combusted; 5 g of BC was placed into an OTF/GSL-type. The volatile content of BC was obtained by placing 5 g of BC into an OTF/GSL-type tubular atmosphere sintering furnace with nitrogen gas, with a gas flow rate of 3 mL/min and a heating rate of 10 °C/min in an anaerobic environment at 900 ± 10 °C. The volatile content of BC was also obtained by heat treating BC in an anaerobic environment.

2.5. Cycling Stability Test

Photothermal performance across varying solar intensities (1–3 kW·m−2) was systematically evaluated. Using a calibrated solar simulator (PLS-SXE300+, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) with optical filters to adjust intensity, we recorded the evaporation rate and surface temperature in real time at each level to assess the evaporator’s scalability and efficiency under enhanced flux.

To assess the long-term operational stability and reusability of the optimal BC 800-40 evaporator under simulated high-salinity conditions, a cyclic evaporation–regeneration experiment was conducted. Each cycle comprised four sequential stages: evaporation, cooling, washing, and regeneration. The evaporator was first irradiated under standard conditions (1 kW m−2, 2.5 mol L−1 NaCl) for 2 h, after which it was cooled naturally to ambient temperature. The BC-loaded sponge was then carefully detached and immersed in deionized water to dissolve surface salt deposits, followed by ultrasonic cleaning (40 kHz, 15 min) to ensure thorough salt removal. The resulting BC dispersion was subsequently vacuum-filtered to reconstitute the evaporation layer. After drying at 70 °C for 2 h, the regenerated evaporation layer was reassembled into the original testing setup for the next cycle. All key evaporation rate and photothermal conversion efficiency (PTE) measurements reported in this study were performed in triplicate under each condition to ensure reliability. The presented values are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experimental runs. The evaporation rate and PTE were monitored in each cycle to evaluate performance retention.

The surface temperature of the evaporation layer was monitored in real-time to elucidate the relationship between BC loading, evaporation efficiency, and thermal management. Under 1-sun illumination, an infrared thermal camera (FLIR E6, FLIR Systems Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA) was used to record the temperature distribution on the evaporator surface at 1 min intervals. Measurements were performed for both 0.2 g and 0.5 g BC loadings in a 2.5 mol L−1 NaCl solution. The average surface temperature was extracted from the thermal images to analyze the dynamic thermal behavior under high-salinity conditions. To systematically evaluate the photothermal performance under varying solar intensities, evaporation tests were conducted under simulated solar illuminations ranging from 1 to 3 sun (1–3 kW·m−2), following methodologies established in previous studies on solar-driven evaporation materials. The light intensity was adjusted using a calibrated solar simulator (PLS-SXE300+, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) equipped with optical filters. The evaporation rate and surface temperature were recorded in real-time for each illumination level to assess the scalability and efficiency of the BC-based evaporator under enhanced solar flux.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of the BC

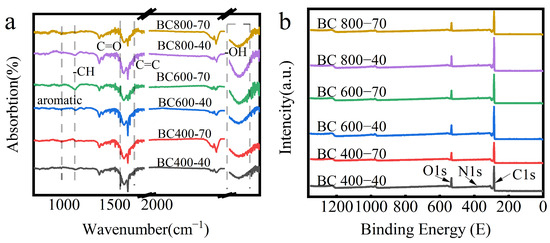

The chemical evolution of BC under different pyrolysis conditions was first characterized. FTIR spectra (Figure 3a) showed a weakening of the absorption peak at 1700 cm−1 with increasing temperature, indicating the decomposition of C=O groups in ketones, amides, and carboxylic acids. Concurrently, the C-H vibration bands on the aryl ring (950 cm−1 and 1100 cm−1) diminished, which is significant as aryl C-H is more hydrophobic than its aliphatic counterpart [38].

Figure 3.

(a) FIRT analysis of BC at different pyrolysis temperatures; (b) XPS maps of BC at different pyrolysis temperatures, (The red line named BC 400-70 represents holding at 400 °C for 70 min); (c) carbon elemental compositional distribution of different BC samples. C1: BC 400-40, c2: BC 400-70, c3: BC 600-40, c4: BC 600-70, c5: BC 800-40, c6: BC 800-70. (d) Different XRD diffraction patterns of BC at different pyrolysis temperatures.

Elemental analysis (Table 1) revealed that the carbon content increased markedly above 400 °C due to the decomposition of biomass components, releasing volatile gases (CO2, CO) [39,40,41]. At 800 °C, the carbon content plateaued, while the relative proportions of oxygen and nitrogen increased, correlating with residual polar functionalities. Prolonged residence time generally reduced carbon content due to extended volatile release.

Table 1.

Elemental contents of C, N, and O in BC at different pyrolysis temperatures.

XPS analysis (Figure 3b,c) provided further insight into the atomic ratios and bonding states. Deconvolution of the C1s peak revealed a systematic evolution: the relative proportion of aromatic C=C/C-C (sp2 carbon) increased markedly, indicating significant formation of an aromatic carbon skeleton. Concurrently, the relative contribution of oxygen-containing functional groups (C–O, C=O) decreased sharply. N species were predominantly present as pyridine- and pyrrole-type nitrogen, while O existed in hydroxyl, ether, and carbonyl groups [42]. This trend is consistent with the attenuation of the C=O band at 1700 cm−1 in FTIR spectra (Figure 3a).

XRD analysis (Figure 3d) corroborated this structural transition. The (002) diffraction peak became distinct at temperatures ≥ 600 °C. Its shift to higher angles corresponded to a decrease in the interlayer spacing (d), confirming a pronounced enhancement in carbon layer stacking order and graphitization beyond the 600 °C threshold, as calculated using Scherrer’s equation [43].

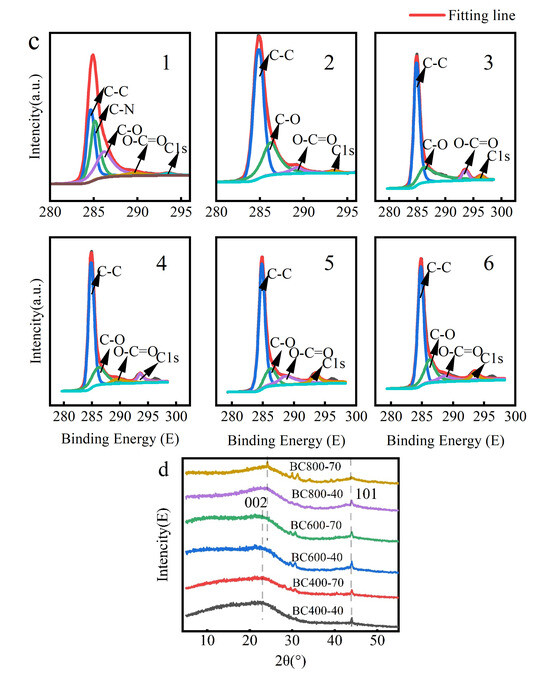

3.2. Structure of the BC

The development of pore structure was primarily observed through microscopy and image analysis. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images revealed that all biochar (BC) samples possessed a dense, fibrous porous structure (Figure 4a,b). Image analysis of the SEM micrographs using ImageJ software (version 1.50d, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Figure 4c indicated a clear trend that higher pyrolysis temperatures were associated with the development of more and larger pores, observable in the two-dimensional cross-sections [44]. Specifically, the analysis suggested that BC pyrolyzed at 800 °C for 40 min (BC 800-40) appeared to possess a larger average pore size and a higher pore density compared to samples prepared at lower temperatures, which is consistent with the more complete decomposition of biomass constituents at elevated temperatures [45].

Figure 4.

(a) BC SEM map/contact angle; (b) SEM map of BC’s aperture; (c) BC’s aperture distribution; (d) first-order derivative of the rate of change in contact angle; (e) average change in contact angle.

The influence of this evolving pore structure on wettability was quantitatively assessed. Contact angle measurements and water droplet penetration tests showed that BC800-40 possessed the highest hydrophilicity among the samples. This was evidenced by its lower static contact angle (Figure 4b) and the faster rate at which the contact angle decreased (dθ/dt, Figure 4d) compared to BCs produced at lower temperatures. The enhanced capillary action provided by the hierarchical pores in BC800-40 facilitated efficient water transport to the evaporation surface [33].

Ultimately, net hydrophilicity is determined by a trade-off between structural and chemical factors. High-temperature pyrolysis maximizes porosity for water conveyance but simultaneously reduces polar surface functional groups and increases graphitic, hydrophobic characteristics. For BC800-40, the advantage conferred by its superior pore structure dominates, leading to optimal performance [46]. In contrast, extending the pyrolysis time at 800 °C (BC 800-70) causes excessive loss of polar groups and greater graphitization, both of which outweigh the benefits of porosity and result in relatively lower hydrophilicity [47]. This balance between pore architecture and surface chemistry is the key mechanism governing BC’s wettability in high-salinity environments (Figure 4e).

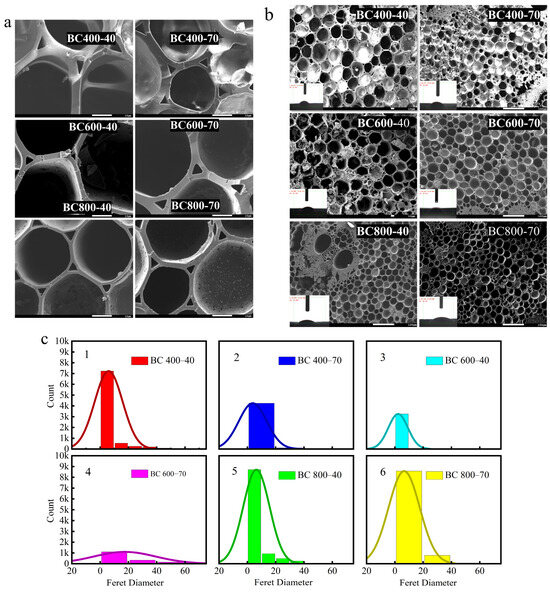

3.3. Photothermal Evaporation of Water

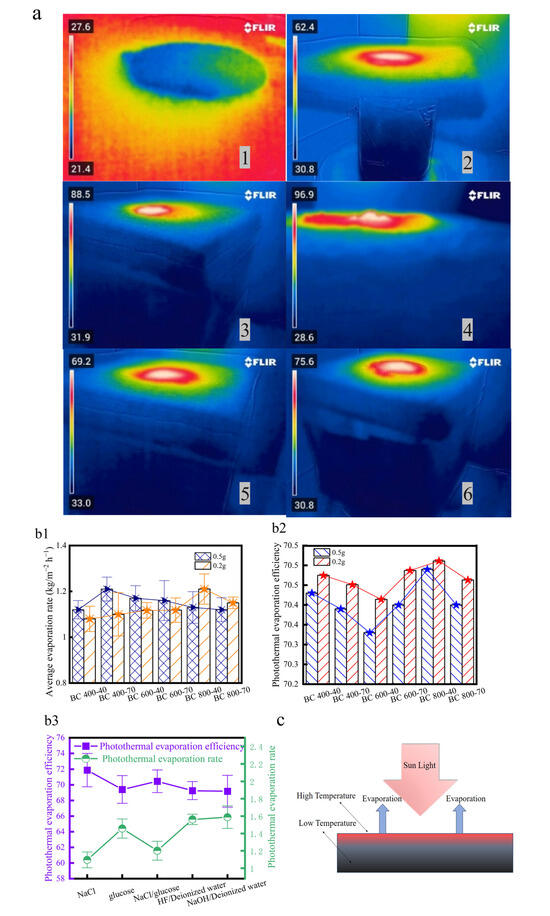

The photothermal evaporation performance of BCs was evaluated using simulated saline wastewater (2.5 mol/L NaCl) under 1 kW/m2 illumination (Figure 5a). Control experiments with different BC additions (0.2 g and 0.5 g) were conducted, as the quantity of BC significantly affects the evaporation rate. With 0.5 g of BC, the sample BC400-40 exhibited the highest evaporation rate among all types (Figure 5b1–b3). However, thermal imaging revealed that high salt concentration led to crystallization on the evaporation layer surface, which can severely clog the porous structure of BC [17,21], and the accumulated BC particles also introduced insulating effects.

Figure 5.

(a) Temperature distributions corresponding to different evaporation systems: (1) Evaporation of deionized water in the absence of light. (2) Photothermal evaporation of deionized water. (3) Photothermal evaporation of NaCl. (4) Late-stage photothermal evaporation of NaCl. (5) Photothermal evaporation of glucose solution. (6) Photothermal evaporation of NaCl/glucose solution. Evaporation rate and efficiency. (b1) Effect of carbon addition on evaporation rate. (b2) Effect of carbon addition on PTE. (b3) Effect of different evaporation systems on evaporation efficiency and PTE under BC 800-40 conditions. (c) Temperature distribution of the photothermal evaporation layer; (d) optimal conditions for BC performance.

When the addition was reduced to 0.2 g, forming a thinner evaporation layer, the overall PTE was higher. In this regime, the performance is governed by a balance between water transport and light absorption. An analysis of the performance under this optimal loading (0.2 g) revealed that the evaporation rate and PTE increased with pyrolysis temperature, but the rate of improvement diminished significantly above 600 °C. This performance inflection aligns closely with the temperature point (~600 °C) identified in structural analysis, where accelerated graphitization and a sharp decrease in the relative proportion of polar surface groups occur. This confirms 600 °C as a critical threshold for optimizing photothermal conversion performance. At higher temperatures, although porosity develops further (Figure 5c), the reduced relative proportion of hydrophilic functional groups partially offsets the structural advantages, leading to diminished returns in performance enhancement.

The photothermal conversion efficiency was calculated according to Equation (4):

BC800-40 demonstrated the best performance here, which correlates with its elemental composition. XPS analysis showed that it had relatively high N and O contents (Table 1), corresponding to abundant polar groups. Nitrogen exists in strongly polar functional groups (e.g., amines, pyridines) that enhance hydrophilicity via hydrogen bonding [48], whereas variations in O content have less impact on wettability. Its high carbon content also contributes to efficient light absorption, which resulted in the evaporation of BC 800-40 at least three times compared to other solar steam generators reported previously (Table 2).

Table 2.

The performance of biochar-based solar steam generators in studies and this work.

Beyond these intrinsic material properties, the stable and reliable operation of the evaporator structure itself is essential for realizing and accurately measuring performance (Figure 1b and Figure 5d). Crucially, the structural design of the evaporator inherently prevents the loss of carbon particles. The evaporation layer, formed by vacuum filtration, is a dense and continuous carbon matrix that is tightly integrated with the underlying hydrophilic non-woven fabric. This fabric serves as the sole capillary water channel, physically isolating the evaporation layer from direct contact with the bulk solution. Consequently, there is no pathway for carbon particles to detach and disperse into the aqueous phase. This inherent stability was maintained throughout all evaporation tests, including prolonged operation with high-salinity brines where salt crystallization occurred on the surface, further attesting to the robustness of the fabricated structure.

With the structural stability of the evaporator confirmed, the decisive role of the material’s surface chemistry was isolated and probed through targeted chemical pretreatment. Alkali (NaOH) treatment of BC800-40 enhanced its photothermal evaporation efficiency by promoting hydrophilicity [52], while acid (HF) treatment reduced efficiency by inhibiting surface hydrophilicity [53] (Figure 5b1–b3). These controlled modifications directly validate the fact that surface functional groups are key modulators of BC’s interfacial water interaction and overall performance.

Therefore, while the evaporation rate and PTE are governed by a complex interplay of factors—including BC loading, pore structure, and salt tolerance—the results underscore that surface chemistry is a pivotal and tunable determinant. The superior hydrophilicity and balanced properties of BC800-40 under optimal loading underscore its favorable application potential in high-salinity water treatment and desalination.

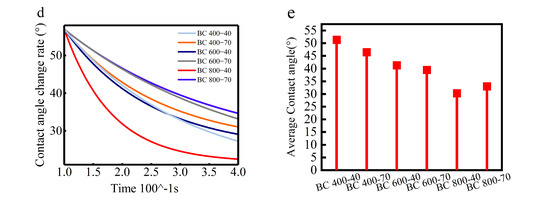

3.4. The Stability of Photothermal Evaporation

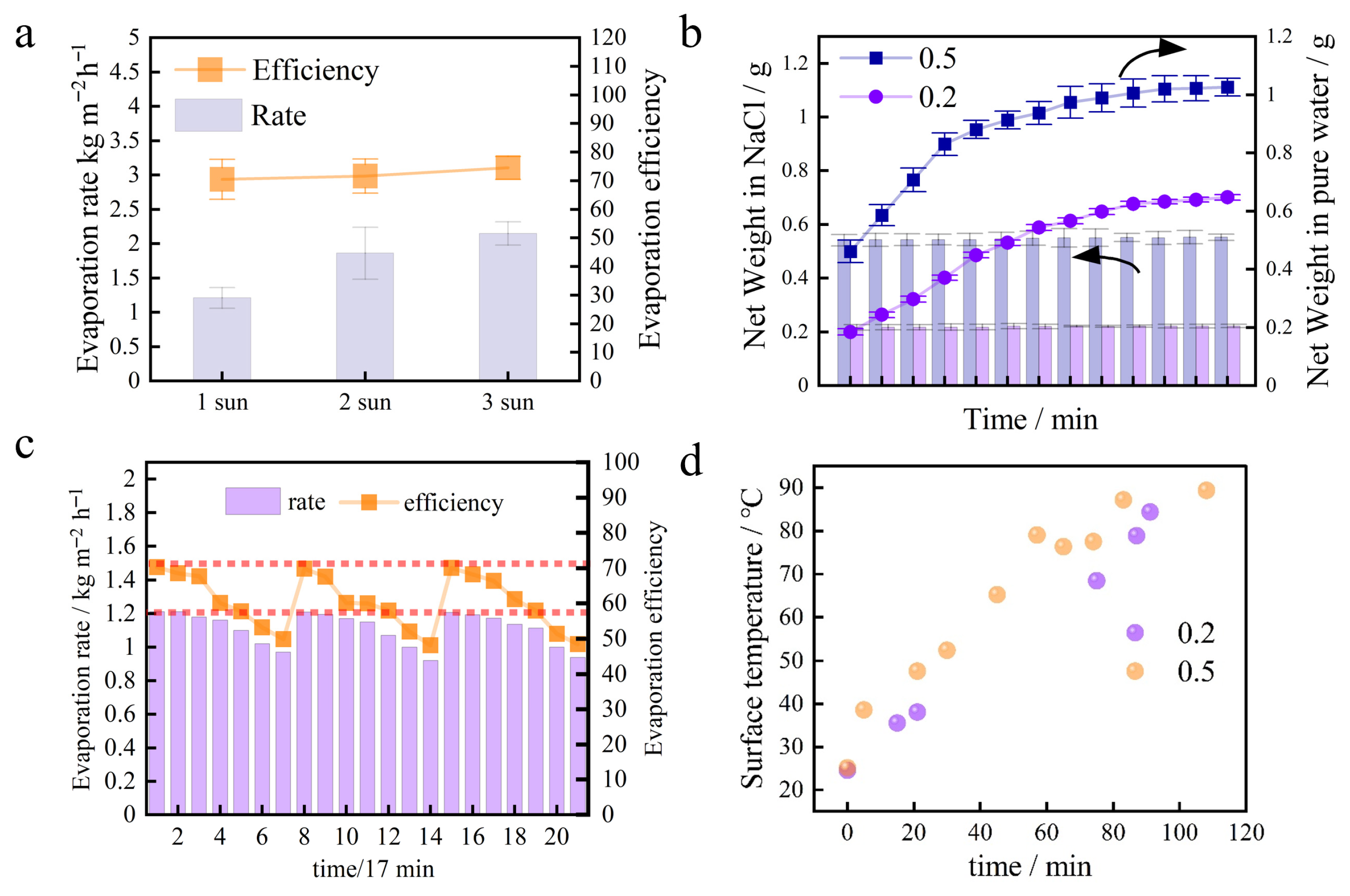

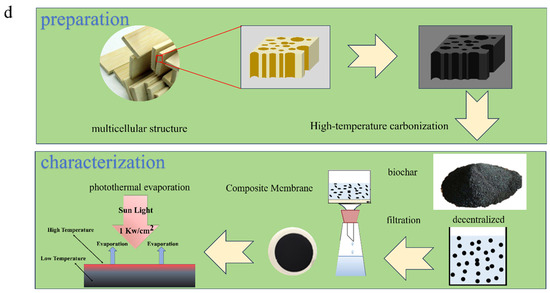

The solar evaporation performance of the optimal sample, BC-800-40, was further evaluated under solar intensities of 1, 2, and 3 sun to assess its scalability and thermal management. As presented in Figure 6a, the evaporation rate increased with solar flux. The PTE, calculated using Equation (2), was sustained at a high level across this range. The maintained efficiency under higher intensities demonstrates effective heat localization at the evaporation interface. This performance is attributed to the material’s inherent low thermal conductivity and its hierarchical porous structure, which facilitates water supply and confines thermal energy. The stable, high efficiency of BC-800-40 was assessed under performance and over time. This supports the higher and more stable efficiency of the 0.2 g BC loading demonstrated in Section 3.3 (Photothermal Evaporation of Water). An optimized, lower BC mass, thus, improves both initial performance and durability in saline water.

Figure 6.

(a) Evaporation rate (ER) of BC 800-40 in seawater under 1 to 3 sun. (b) Temporal variation in the net weight of the BC evaporation layer during photothermal evaporation (bars: net weight in pure water; dotted line: net weight in NaCl). (c) Evaporation rate and photothermal conversion efficiency of the BC 800-40 evaporator over five consecutive evaporation–regeneration cycles under 1 sun illumination and 2.5 mol/L NaCl solution. Each data point is the mean of three replicate tests for that specific cycle, with error bars representing the standard deviation. (d) Surface temperature evolution of BC evaporators with 0.2 g and 0.5 g loadings during photothermal evaporation in 2.5 mol/L NaCl solution under 1 sun illumination.

The cycling stability of the BC 800-40 evaporator, a critical metric for practical applications, was evaluated through repeated evaporation–regeneration cycles under high-salinity conditions (2.5 mol L−1 NaCl, 1 sun). As illustrated in Figure 6c, the mass dynamics of the evaporation layer in saline NaCl solution are determined by the interplay between BC loading and its resulting porous structure. High-temperature pyrolysis, as represented by BC 800-40, leads to increased porosity alongside a reduction in polar oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., C=O) and enhanced graphitization (Figure 4a–c). In saline conditions, salt ions are transported with water to the evaporation surface and internal pores, where they crystallize upon evaporation, contributing to mass gain.

Higher BC loading (0.5 g) forms a denser, more compact layer with a greater surface area, which facilitates rapid salt nucleation and accelerates pore blockage, leading to quick mass saturation. In contrast, the 0.2 g BC layer features a more open and interconnected pore network. This structure moderates water and salt transport, slows down crystallization kinetics, and extends the duration of mass increase, thereby improving long-term stability. In summary, while surface chemistry evolves with pyrolysis, the key factor influencing mass change and salt tolerance is the structural configuration governed by BC loading. Optimizing loading weight rather than focusing solely on chemical modification provides an effective strategy to enhance the durability of BC-based solar evaporators in high-salinity environments.

Surface temperature monitoring provided further insight into the performance advantage of the 0.2 g BC layer. As shown in Figure 6d, during brine evaporation, the surface temperature of the 0.5 g BC layer rose rapidly and stabilized at a higher level (~65 °C). In contrast, the 0.2 g BC layer exhibited a significantly lower and more stable temperature (~55 °C). The lower surface temperature indicates that the 0.2 g BC layer more effectively utilizes absorbed solar energy for water vaporization (latent heat) rather than heating the material itself (sensible heat). This benefits from its optimized porous structure, which ensures a sustained water supply and efficient thermal management. Therefore, a lower and more stable surface temperature directly reflects the higher evaporation efficiency and superior salt tolerance of the 0.2 g BC layer.

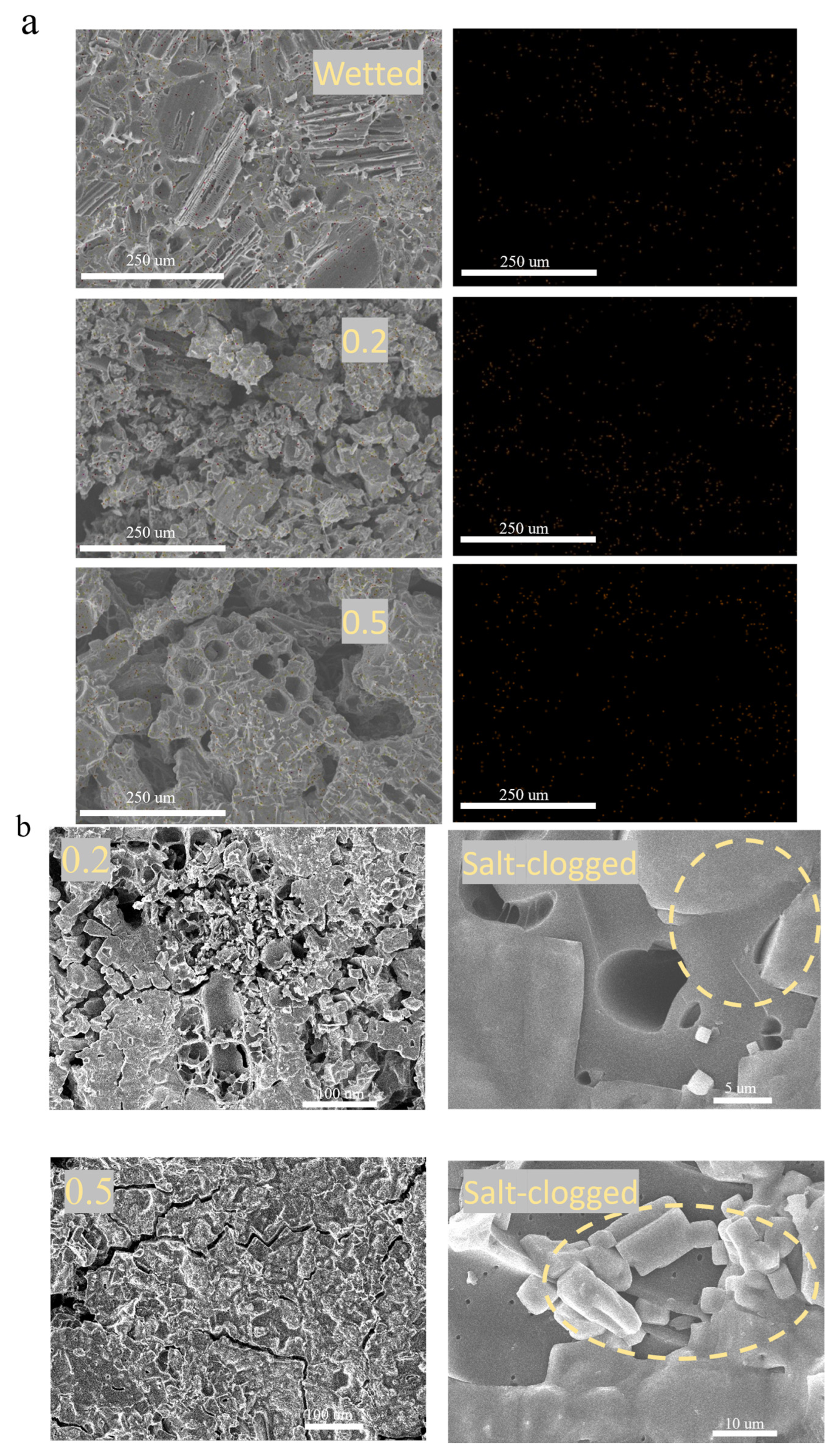

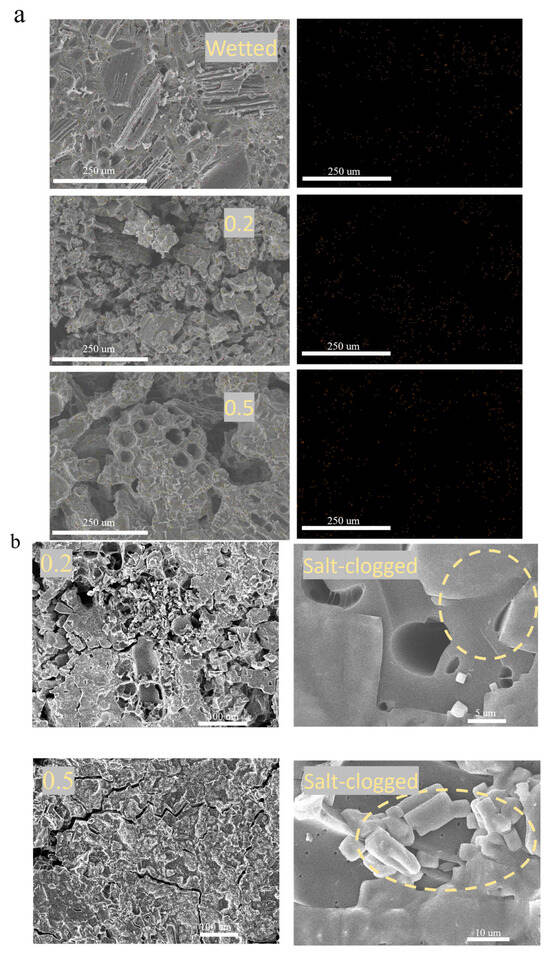

To understand the different salt tolerances of BC 800-40 evaporators at different loadings, evaporation layers were analyzed after durability tests using SEM and EDS.

EDS mapping (Figure 7a) showed clear differences in surface sodium distribution. The control sample, only wetted with the solution, showed sparse Na signals. After evaporation testing, both the 0.2 g and 0.5 g BC layers showed strong sodium accumulation, with the 0.5 g layer exhibiting the highest density. This confirms that the NaCl solution fully penetrates the porous BC 800-40 due to its good wettability, and salt crystals grow inside the pores upon drying. The lower sodium intensity in the 0.2 g layer suggests more uniform salt distribution within the material rather than surface accumulation, consistent with its slower mass gain and lower surface temperature noted earlier.

Figure 7.

(a) EDS elemental mapping of sodium (Na) on the surface of BC 800-40 evaporators after testing. (b) SEM images of BC 800-40 surfaces after cyclic evaporation tests in 2.5 mol/L NaCl solution.

SEM images (Figure 7b) provided direct visual evidence. NaCl crystals were clearly seen on all tested surfaces, confirming salt crystallization within the hydrophilic structure. In the 0.2 g layer, although some small pores were salt-clogged, many larger pores remained open. In contrast, the 0.5 g layer showed severe pore blockage and notably fewer large pores. This dense, superficial salt crust in the 0.5 g layer restricts both water influx and vapor release.

Thus, the better-preserved pore network and less severe surface salt coverage in the 0.2 g BC layer can help maintain efficient water-vapor transport, explaining its higher and more stable evaporation efficiency under high-salinity conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study clarifies the process−structure−property relationships in bamboo-derived BC for solar-driven evaporation. Pyrolysis temperature is the dominant controlling factor, with ~600 °C identified as a critical threshold for structural and chemical transformation. Below this temperature, BC maintains a higher relative proportion of polar surface functional groups (e.g., C–O, C=O), which benefits interfacial hydration, but exhibits limited pore development. Above this threshold, pronounced carbon skeleton graphitization and enhanced pore structure occur alongside a drastic reduction in the relative proportion of polar functional groups, shifting the surface chemistry towards a graphitic carbon-dominated characteristic. The key finding is that pyrolysis temperature and residence time critically control the trade-off between porous structure development and the retention of polar functional groups, which together determine photothermal performance. BC prepared at 800 °C for 40 min (BC 800-40) exhibited an optimal balance, combining hierarchical porosity with adequate surface hydrophilicity, and demonstrated the highest efficiency in this study. Thise study further reveals that BC loading critically governs salt crystallization dynamics within the evaporation layer. A thinner layer (0.2 g BC) exhibits faster and deeper salt intrusion due to a higher evaporation flux, while a thicker layer (0.5 g BC) shows more surface-localized, self-limiting crystallization. Therefore, the optimal BC loading (0.2 g) represents a balance that maximizes evaporation efficiency while moderately mitigating the rate of performance-degrading salt accumulation.

This is a fundamental proof-of-concept study; however, it is imperative to explicitly acknowledge current limitations to properly contextualize the findings and guide future development. The main constraints identified include limited operational stability under sustained high-salinity conditions, with a decline in performance observed after approximately 2 h of continuous evaporation due to progressive salt accumulation. An evaporation efficiency that, while competitive among biochar-based materials, lags behind the highest values reported for state-of-the-art synthetic photothermal systems, indicating significant room for structural or compositional optimization. Scalability challenges also exist primarily stemming from the energy-intensive pyrolysis process required to achieve the optimal porous structure, which raises concerns regarding economic and environmental costs for large-scale production. The unresolved issue of surface salt crystallization, which progressively clogs pores and impairs the water supply, also affects long-term evaporation rates.

Future work should focus on concrete strategies to advance practical application. This includes engineering surface properties or incorporating salt-rejection mechanisms to extend operational stability, enhancing photothermal performance by constructing hybrid structures or fine-tuning the carbon lattice based on the established 600 °C threshold, developing lower-energy synthesis routes like catalytic or microwave-assisted pyrolysis to preserve the porosity–chemistry balance, and implementing effective salt management strategies through structural or operational means. Elucidated process–structure–property relationships provide a clear roadmap for these optimizations. Despite current limitations, this study establishes a fundamental foundation for rationally designing efficient and sustainable BC-based photothermal systems for challenging water treatment. Furthermore, a comprehensive assessment of environmental compatibility, including the long-term stability and potential leaching behavior of any inherent or accumulated substances in complex real-world waters, will be essential for practical deployment.

Author Contributions

W.F.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing an original draft. S.Y.: Software, Validation. J.D., S.Y., J.W. and B.L.: Investigation, Resources, Data curation. Y.W.: Investigation, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financially supported by the Hubei Provincial Department of Education scientific research program youth project (No. Q20231811) and the Guiding Project of the Hubei Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Plan (No. BK202104). The authors acknowledge the support received from The Analytical & Testing Center of the Hubei University of Automotive Technology.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Junyao Dai was employed by the company The Exibei Highway Operation Management Co., Ltd. of Hubei Provincial Communications Investment Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, J.; Dai, K.; Bie, C. Guest Editorial: Solar Energy Utilization. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 7, 2200478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, O.; Moletta, R. Treatment of organic pollution in industrial saline wastewater: A literature review. Water Res. 2006, 40, 3671–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Gao, H.; Cheng, K.; Bai, L.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X. An overview of photothermal materials for solar-driven interfacial evaporation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Tang, M.; Guan, B.; Wang, K.; Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, M.; Shan, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, D.; et al. Hierarchical Graphene Foam for Efficient Omnidirectional Solar–Thermal Energy Conversion. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Du, Q.; Tang, K.; Shen, Y.; Hao, L.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; et al. Carbonized Bamboos as Excellent 3D Solar Vapor-Generation Devices. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1800593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Lee, K.S.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed, M.A. Calculated Absorption and Scattering Properties of Gold Nanoparticles of Different Size, Shape, and Composition: Applications in Biological Imaging and Biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 7238–7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Ho-Baillie, A.; Snaith, H.J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photon 2014, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Gao, H.; Wu, Y. Flexible Electronics Based on Organic Semiconductors: From Patterned Assembly to Integrated Applications. Small 2023, 19, 2206938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, P.; Ni, G.; Song, C.; Shang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, G.; Deng, T. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X.; Dai, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yan, X.; Song, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Plasmonic Wood for High-Efficiency Solar Steam Generation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Yang, P.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S. Scalable Ultralight Wood-Inspired Aerogel with Vertically Aligned Micrometer Channels for Highly Efficient Solar Interfacial Desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 50522–50531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Tan, S.; Lu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, W.; Xu, Z. Orientational Bamboo Veneer Evaporator for Enhanced Interfacial Solar Steam Generation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 3331–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Musso, F. Hygrothermal performance of natural bamboo fiber and bamboo charcoal as local construction infills in building envelope. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 177, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, T.; Ishihara, S.; Yamane, T.; Toba, A.; Yamada, A.; Oikawa, K. Science of Bamboo Charcoal: Study on Carbonizing Temperature of Bamboo Charcoal and Removal Capability of Harmful Gases. J. Health Sci. 2002, 48, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, R.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J. Anti-bacterial and super-hydrophilic bamboo charcoal with amidoxime modified for efficient and selective uranium extraction from seawater. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 598, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, G. Economical Salt-Resistant Superhydrophobic Photothermal Membrane for Highly Efficient and Stable Solar Desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 35142–35151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Song, C.; Wu, J.; Dasgupta, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Tao, P.; et al. Bioinspired Multifunctional Paper-Based rGO Composites for Solar-Driven Clean Water Generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14628–14636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhu, J. Tailoring Aerogels and Related 3D Macroporous Monoliths for Interfacial Solar Vapor Generation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkhoda, A.M.; Ellis, N.; Gyenge, E. Effect of activated biochar porous structure on the capacitive deionization of NaCl and ZnCl2 solutions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 224, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, L.; Bao, F.; Chen, G.; Song, K.; Wang, Z.; Xia, H.; Gao, J.; Song, Y.; Zhu, C.; et al. Carbon materials for enhanced photothermal conversion: Preparation and applications on steam generation. Mater. Rep. Energy 2024, 4, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.H.H.; Fatah, N.M.; Muhammad, K.T. Advancements in application of modified biochar as a green and low-cost adsorbent for wastewater remediation from organic dyes. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 232033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Ansari, S.A.; Sawarkar, R.; Agashe, A.; Singh, L.; Nidheesh, P.V. Bamboo biochar: A multifunctional material for environmental sustainability. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 28821–28845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.J.; Xie, P.F.; Wu, C.; Jiang, L. A high adsorption capacity bamboo biochar for CO2 capture for low temperature heat utilization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 293, 121131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, K.; Singhwane, A.; Dhangar, M.; Mili, M.; Gorhae, N.; Naik, A.; Prashant, N.; Srivastava, A.K.; Verma, S. Bamboo for producing charcoal and biochar for versatile applications. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 15159–15185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Piao, X.; Guo, H.; Xiong, Y.; Cao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, C. A multi-function bamboo-based solar interface evaporator for efficient solar evaporation and sewage treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 200, 116823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.S. Biomass-Based Porous Functional Materials for Photothermal Decontamination of Water. PhD Thesis, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/107752 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Li, Z.; Wei, S.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z. Biomass-based materials for solar-powered seawater evaporation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Sustainable Interfacial Evaporation System Based on Hierarchical MXene/Polydopamine/Magnetic Phase-Change Microcapsule Composites for Solar-Driven Seawater Desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 50966–50981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Yang, H.; Wu, S.; Tian, Y.; Guo, X.; Xu, C.; Kuang, W.; Yan, J.; Cen, K.; Bo, Z.; et al. Multifunctional solar bamboo straw: Multiscale 3D membrane for self-sustained solar-thermal water desalination and purification and thermoelectric waste heat recovery and storage. Carbon 2021, 171, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, Z.; He, W.; Wei, R.; Gao, L. Response Surface Optimization and Adsorption Mechanism of Sheep Manure Charcoal on Nitrogen and Phosphorus Adsorption Conditions. Ecol. Environ. 2023, 32, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Q. Preparation of biochar with high absorbability and its nutrient adsorption–desorption behaviour. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, J. Highly salt-resistant and all-weather solar-driven interfacial evaporators with photothermal and electrothermal effects based on Janus graphene@silicone sponges. Nano Energy 2021, 81, 105682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Peng, L.-M.; Tang, C.-Y.; Pu, J.-H.; Zha, X.-J.; Ke, K.; Bao, R.-Y.; Yang, M.-B.; Yang, W. All-weather-available, continuous steam generation based on the synergistic photo-thermal and electro-thermal conversion by MXene-based aerogels. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Han, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Qi, D.; Liu, D.; Wang, W. A solar-electro-thermal evaporation system with high water-production based on a facile integrated evaporator. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 21771–21779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Li, B. Enhancing efficiency of carbonized wood based solar steam generator for wastewater treatment by optimizing the thickness. Sol. Energy 2019, 193, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, J.; Peng, H.; Leng, S.; Li, H.; Qu, W.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, W.; et al. Effect of biomass type and pyrolysis temperature on nitrogen in biochar, and the comparison with hydrochar. Fuel 2021, 291, 120128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Abraham, M.H.; Zissimos, A.M. Fast Calculation of van der Waals Volume as a Sum of Atomic and Bond Contributions and Its Application to Drug Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7368–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; O’Connor, D.; Zhang, J.; Peng, T.; Shen, Z.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Hou, D. Effect of pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and residence time on rapeseed stem derived biochar. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Ir–C xerogels synthesized by sol–gel method for NO reduction. Catal. Today 2008, 137, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, K.; Huang, C.; Yang, M.; Fan, M.; Wang, A.; Zhang, G.; Li, B.; Jiang, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Investigation on the mechanism of structural reconstruction of biochars derived from lignin and cellulose during graphitization under high temperature. Biochar 2023, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Effects of temperature and particle size on bio-char yield from pyrolysis of agricultural residues. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2004, 72, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, C. Overcoming salt crystallization with ionic hydrogel for accelerating solar evaporation. Desalination 2020, 482, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariyar, P.; Kumari, K.; Jain, M.K.; Jadhao, P.S. Evaluation of change in biochar properties derived from different feedstock and pyrolysis temperature for environmental and agricultural application. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lua, A.C.; Yang, T.; Guo, J. Effects of pyrolysis conditions on the properties of activated carbons prepared from pistachio-nut shells. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2004, 72, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Choghamarani, F.; Moosavi, A.A.; Sepaskhah, A.R. Sugarcane bagasse derived biochar potential to improve soil structure and water availability in texturally different soils. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Johnson, M.G.; Dragila, M.I.; Kleber, M. Water uptake in biochars: The roles of porosity and hydrophobicity. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 61, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Hu, X.; Wan, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, B. Removal of lead, copper, cadmium, zinc, and nickel from aqueous solutions by alkali-modified biochar: Batch and column tests. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 33, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pang, Y.; Huang, W.; Shaw, S.K.; Schiffbauer, J.; Pillers, M.A.; Mu, X.; Luo, S.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Y.; et al. Functionalized Graphene Enables Highly Efficient Solar Thermal Steam Generation. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 5510–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.; Kang, G.; Cho, S.K.; Park, W.; Kim, K.; Padilla, W.J. Flexible thin-film black gold membranes with ultrabroadband plasmonic nanofocusing for efficient solar vapour generation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Yang, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Hitz, E.; Jia, C.; Gong, A.; Jiang, F.; Zhu, J.Y.; et al. Highly Flexible and Efficient Solar Steam Generation Device. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Luo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, M.; Song, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ling, Z. Scalable and flexible biomass-derived photothermal paper for efficient solar-assisted water purification. Cellulose 2023, 30, 7193–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Qiu, R.; Zhang, X. Enhanced removal of aqueous Cd(II) by a biochar derived from salt-sealing pyrolysis coupled with NaOH treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 511, 145619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Lang, Y.-H.; Wang, X.-M. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of pentachlorophenol on reed biochars: pH effect, pyrolysis temperature, hydrochloric acid treatment and isotherms. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 90, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.