Abstract

Introduction: This case highlights a rare and significant complication of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: optic neuritis (ON). Acute Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in children typically presents with respiratory tract symptoms and may occasionally lead to complications or sequelae. ON is a condition most commonly associated with viral infections or other demyelinating diseases. Case report: The patient, a 10-year-old girl, initially presented with the typical systemic symptoms of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection, including fever, chills, and headache, in addition to an atypical symptom—chromatic deficit, or visual disturbances. This prompted further investigation into potential neurological complications, ultimately leading to a diagnosis of ON. The case underscores the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic workup, including serological testing (IgM ELISA) and PCR analysis of nasopharyngeal specimens, to confirm the underlying infection. Additionally, imaging studies (CT, MRI) and consultations with specialists in neurology and ophthalmology were critical for excluding other potential causes and assessing the extent of complications. The rapid and favorable response to treatment highlights the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate management. Conclusions: Although ON is a rare complication of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection, it should be considered in pediatric patients with unexplained visual symptoms, particularly when the clinical course does not improve or worsens despite treatment for the primary infection. This case further emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in managing complex cases and the need for vigilant monitoring of potential neurological complications in children with respiratory infections.

Introduction

Optic neuritis (ON) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the optic nerve, which may be complicated by reversible loss of vision. It can occur as a complication of autoimmune diseases or systemic inflammatory diseases (sarcoidosis, disseminated lupus erythematosus, erythema nodosum) as well as in demyelinating diseases (multiple sclerosis, optic neuromyelitis, Shidler’s disease) [1,2]. Cases of post-vaccination ON have also been described [2].

Infectious diseases are an important category of conditions that can be complicated by ON. Of these, viral infections (adenovirus, coxsackie, rubeola, rubeola, varicella-zoster viruses) and, less frequently, bacterial infections (streptococcal infections, brucellosis, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, syphilis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, neuroborreliosis, Whipple's disease) are most frequently involved in the etiology of ON [3,4,5]. Parasitic diseases are also an important category of etiological agents involved in the development of ON (Toxoplasma, Toxocara) [5].

Chlamydia pneumoniae is an intracellular gram-negative bacterium responsible for numerous acute and chronic infections in both children and adults. Although this microorganism is most commonly responsible for respiratory tract disease, cases of disseminated infections have been reported with localization mainly in the central nervous system (vasculitis, encephalitis, encephalomyelitis) [6]. Acute infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae can rarely be complicated by ON, with very few cases reported. A correlation between Chlamydia pneumonia infection and the development of multiple sclerosis has also been suggested, but there has not been sufficient clinical evidence to support this theory [7,8].

In children, ON has a lower risk of recurrence and progression to multiple sclerosis compared to adult optic neuritis [9].

This case presentation draws physicians’ attention to a rare etiology of ON: acute infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. Although the infectious etiology of ON in children is uncommon, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Case Report

We present a 10-year-old female, who was admitted to our hospital with a high fever accompanied by shivering, as well as headache and chromatic deficit. The onset of her current symptoms occurred 24 hours prior to her presentation at our clinic. On the day of admission, she initially presented to her family doctor, who, after clinical evaluation, suspected acute meningitis and referred the child to our clinic.

Clinical examination upon admission revealed a child, conscious, cooperative, and temporo-spatially oriented, with a pale complexion. She exhibited left paravertebral contracture, diarrheic stools, and decreased appetite, but no signs of meningeal irritation. She complained of pain and limited movement with both active and passive head flexion and reported perceiving only the color pink in various shades.

Initial laboratory investigations revealed mild lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, as well as inflammatory syndrome (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dynamic laboratory investigations.

Given the sudden onset of chromatic deficiency, we requested an ophthalmological consultation on the first day of hospitalization. The consultation revealed clear pupils, normal caliber arteries and veins, no macula lesions, and normal motility, but confirmed the presence of a red-green axis chromatic deficit. Following the consultation, the ophthalmologist suspected retrobulbar ON and recommended completing the investigations with a brain MRI and optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Since the initial suspicion was meningitis, we also requested a neurological consultation, which ruled out encephalitis or meningitis. The neurological examination was within normal limits, except for a painful paravertebral contracture during anterior flexion of the head and visual disturbances.

Based on the epidemiological (brother diagnosed with influenza type A), clinical (fever, chills, diarrhea, visual disturbances), paraclinical, and interdisciplinary consultations, the diagnosis of ON, likely of viral etiology, was established.

We conducted investigations using serological tests for viral infections (adenovirus, coxsackievirus, rubella, and varicella-zoster), bacterial infections (streptococcal infections, brucellosis, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, syphilis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Borrelia infection), and parasitic infections (toxoplasmosis and toxocariasis). The tests for viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections were negative, but IgM antibodies for Chlamydia pneumoniae were positive. This was later confirmed with a positive upper respiratory tract RT-PCR the following day. Rapid tests and later RT-PCR also ruled out influenza etiology.

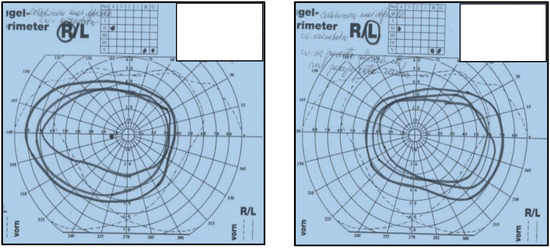

On the second day of hospitalization, imaging investigations were also performed, including an MRI and an OCT scan, and visual field assessment, which revealed red-green dyschromatopsia, typical of optic neuritis. The Goldmann visual field examination revealed a more pronounced constriction in the left eye compared to the right eye. In the right eye, the visual field was narrowed in the superior and inferior nasal regions, while in the left eye, constriction was observed throughout the entire visual field. Visual field images are found in Figure 1 (A and B).

Figure 1.

The image represents a visual field examination, illustrating red-green dyschromatopsia, a characteristic finding in cases of optic neuritis; (A) Right eye; (B) B Left eye.

OCT revealed a normal peripapillary optic nerve fiber layer, a normal anterior pole in both eyes, and good ocular motility in all directions.

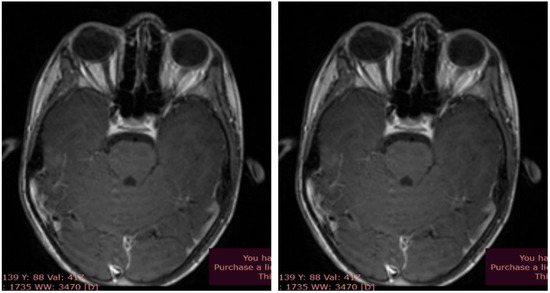

Cervical neck and brain MRI showed dimensional asymmetry at the level of the optic nerves (II), with a retro-ocular transverse diameter of 4.5 mm on the right side and 4 mm on the left side, but symmetric prechiasmatic areas, without native or post-contrast signal abnormalities. The imaging also revealed the existence of a retrovermian arachnoid cyst, paramedian on the left side with a diameter of 9/10 mm, and a minimal C5-C6 posterior disc bulge with discrete dural sac indentation, without discoradicular conflicts (Figure 2, A and B).

Figure 2.

Brain MRI - optic nerves; (A) T2 sequence, native axial; (B) T1 sequence, axial contrast.

Based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging data, the diagnosis of retrobulbar optic neuritis due to acute Chlamydia pneumoniae infection was established.

We initiated etiological, pathogenic, and symptomatic treatment for a period of 7 days, which coincided with the duration of hospitalization: clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day, dexamethasone 0.5 mg/kg/day, and paracetamol 30 mg/kg/day (used as an analgesic).

The patient’s progress was favorable: she did not experience any fever from the second day of hospitalization, and the recovery of the chromatic deficit was gradual. She was able to perceive most colors after 2 days of treatment, with normal vision restored after 4 days.

After 7 days of etiological, pathogenic, and symptomatic treatment, the clinical outcome was favorable. The clinical examination at discharge was within normal limits, with the resolution of dyschromia and no subjective or objective complaints.

We recommended continuing antibiotic therapy at home for an additional 7 days and administering optic nerve trophic treatment (vitamin B complex). The child was reassessed after the completion of the treatment (14 days after the hospitalization).

The follow-up examination did not reveal any pathological changes in the clinical examination or laboratory investigations. Serology for Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM was negative, and IgG was positive. The ophthalmological consultation was within normal limits.

Discussion

The diagnosis of optic neuritis in this case was established based on clinical data (visual disturbances, including dyschromatopsia - abnormal color vision, notably red color desaturation), laboratory findings (positive IgM serology and PCR for Chlamydia pneumoniae), and confirmed by the MRI appearance.

Although MRI is not necessary in most cases for diagnosing ON in children, it can reveal focal abnormalities of the anterior visual pathway [10]. Typical changes on MRI in studies dedicated to the orbit include thickening of the optic nerves on T1-weighted imaging and bright T2 signal along the optic nerve, which were also identified in our case.

Other causes of infectious ON were ruled out through negative serologies and PCR (Mycoplasma, hepatitis, HIV, herpes, syphilis, mumps, measles, chickenpox, sinusitis, tuberculosis).

The possible bacterial etiology of neuritis was ruled out by negative IgM serologies for Bartonella, Borrelia, and Coxiella. Other possible infections were considered, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis (excluded by a negative QuantiFERON test) and Treponema pallidum (negative TPHA and VDRL tests). Parasitic infections were ruled out by negative serologies (Toxoplasma, Toxocara).

Autoimmune etiology (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, polyarteritis nodosa) was not considered because inflammatory markers and specific tests were negative. Other possible etiologies of optic neuritis in children (lead and arsenic poisoning, diabetes mellitus, Graves' disease, head trauma, or insect bites) were also excluded.

Tests for autoimmune diseases were also performed which showed no pathological changes, thus excluding it as a cause of the ON.

Anamnestically, toxic or drug use was ruled out, and brain imaging ruled out demyelinating diseases.

Rare neurological diseases (neuromyelitis optical - Devic's disease, anti-MOG-associated encephalomyelitis (MOGAD), and Schilder's disease) that can trigger optic neuritis were ruled out through neurological consultation. The treatment administered consisted of corticosteroids, resulting in a favorable outcome, along with medications to support the optic nerve (B vitamins) and symptomatic treatment (analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gastric protectors, and rehydration infusions).

Very few cases are described in the literature with an etiology of atypical microorganisms, with Mycoplasma pneumoniae being more frequently associated with optic neuritis [4]. This case is particular both due to its symptomatology (visual disturbances – dyschromatic) and its rare etiology: Chlamydia pneumoniae. This etiology is reported in the literature for demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system, with optic neuritis being associated in this context [8,9].

Under classical treatment (corticosteroids), the outcome was favorable, with the disappearance of the dyschromatic visual disturbances. Paracetamol was also administered for pain and fever.

According to the medical literature, the treatment of optic neuritis with corticosteroids has an average duration of five days, with extremes ranging from three to fourteen days [10].

Another distinctive feature of this case is the patient's age; optic neuritis is rarer in children, regardless of etiology. Most pediatric optic neuritis cases are associated with autoimmune diseases and demyelinating disorders [9,10].

The described case represents a moderate form of optic neuritis in a child without comorbidities, with a favorable progression under the instituted treatment, resulting in no sequelae or recurrences. However, optic neuritis in children has a significant potential for progression to demyelinating disease, which is why the child must remain under long-term neurological medical observation.

Conclusions

The case presented demonstrates that acute Chlamydia pneumoniae infection can be complicated by central nervous system demyelination and optic nerve damage, clinically manifested by dyschromia. Although a rare complication of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in children, optic neuritis should be considered by the clinician as it can evolve severely with irreversible sequelae in the absence of appropriate treatment.

The peculiarity of the case lies in the fact that the onset of the condition occurred suddenly in a child with a family history of influenza (brother), which could have led to an incorrect epidemiological diagnosis. However, complex and thorough investigations led to the correct and rapid establishment of the etiological diagnosis of optic neuritis, followed by the administration of the appropriate treatment. As a result, the disease course was rapidly favorable, with complete recovery and no sequelae or complications.

Another particularity of this case is that, from an etiological perspective, Chlamydia pneumoniae is rarely implicated in the etiology of optic neuritis in children, with only a few cases reported in the specialized literature.

The potential evolutionary risk of pediatric optic neuritis with Chlamydia pneumoniae towards demyelinating diseases represents a serious reason for neurological monitoring of the child.

A pediatrician confronted with optic neuritis in a child must consider, in addition to the most common etiologies, a possible infectious cause: Chlamydia pneumoniae infection.

Author Contributions

BB wrote the manuscript, GJ and MMM critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, GJ and BB participated in patient evaluation and treatment, GJ and MMM interpreted the required diagnostic test and provided valuable images, MMM prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained the Ethical Committee of the National Institute of Infectious Disease “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș” Bucharest.

Informed Consent Statement

The authors obtained written informed consent from the patient’s parents for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- Chang, M.Y.; Pineles, S.L. Pediatric Optic Neuritis. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2017, 24, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.L.; Costello, F.; Chen, J.J.; et al. Optic neuritis and autoimmune optic neuropathies: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagelskjaer, L.H.; Hansen, N.J. Neurologiske komplikationer ved Mycoplasma pneumoniae infektioner [Neurological complications of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1993, 155, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kraker, J.A.; Chen, J.J. An update on optic neuritis. J Neurol. 2023, 270, 5113–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.P.; Zhang, X.J. [To improve understanding of etiology of optic neuritis in China]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2009, 45, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammerschlag, M.R.; Kohlhoff, S.A.; Gaydos, C.A. 184 - Chlamydia pneumoniae. In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases; Bennett, J.E., Bolin, R., Blaser, M.J., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 2174–2182.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, S.; Stratton, C.W.; Yao, S.; Tharp, A.; Ding, L.; Bannan, J.D.; Mitchell, W.M. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection of the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1999, 46, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiz, A.; Marcos, M.A.; Graus, F.; Vidal, J.; Jimenez de Anta, M.T. No evidence of CNS infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2001, 248, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, D.; Rostasy, K.; Gieffers, J.; Maass, M.; Hanefeld, F. Recurrent optic neuritis associated with Chlamydia pneumoniae infection of the central nervous system. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 770–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, E.A.; Graves, J.S.; Benson, L.A.; Wassmer, E.; Waldman, A. Pediatric optic neuritis. Neurology. 2016, 87 (Suppl 2), S53–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2025.