Abstract

Introduction: Even though the increasing incidence of VIM-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae has been reported worldwide, studies are still lacking in Palestine. The aim of this study was to screen carbapenem-resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae bacteria in the Gaza Strip, Palestine and further to characterize carbapenemase-producing isolates. Methods: A total of 69 E. coli and 27 K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from three Gaza hospitals and recovered from urine, wound swabs, blood and ear discharge. The screening for metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) was performed by using the imipenem-EDTA disc synergy test. The detection of β-lactamases genes, detection of non-β-lactam genes and the characterization of integrons were performed by PCR and sequencing. The clonal relationship among the isolates was determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Results: Our study showed that 4 E. coli (5.8%) and 5 K. pneumoniae (18.5%) were positive by the imipenem-EDTA disc synergy test. BlaVIM-4 was detected in six isolates and blaVIM-28 was identified in three isolates. The β-lactamases genes in the VIM-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were blaCTX-M-15 (n = 3), blaCTX-M-14 (n = 1), blaSHV-1 (n = 3), blaSHV-12 (n = 1), blaTEM-1 (n = 1) and blaOXA-1 (n = 1). Aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene was confirmed in four E. coli and in two K. pneumoniae isolates. QnrS1 was identified in two K. pneumoniae isolates. The class 1 integron was identified with the different gene cassette; dfrA17-aadA5, dfrA5, dfrA12-orf-aadA2 and dfrA17-aadA5 were identified. Conclusions: Our study indicated for the first time the emergence of multidrug-resistant VIM-containing K. pneumoniae and E. coli isolates of clinical origin in Gaza Strip hospitals.

Introduction

Carbapenems are a β-lactam class of antibiotics used as a last resort treatment for infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria. These drugs are also1 stable in response to AmpC β-lactamases and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) [1]. Resistance to carbapenems has been reported in many regions and the rate of carbapenem resistance is rising [1]. Carbapenems remain the treatment of choice for bacterial infections caused by ESBL-producing organisms in Palestine [2].

In the last decade, two main groups of broad-spectrum β-lactamases have emerged in Gram-negative bacteria: the ESBLs, more commonly demonstrated in the family of Enterobacteriaceae; and the metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), which are most frequently observed in non-fermenting Gram-negatives [1].

Beta-lactamase enzymes that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring in β-lactam group of antibiotics are the primary resistance mechanism. Beta-lactamases are classified into four classes; the active-site serine β-lactamases (classes A, C and D) and metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs; class B), which are zinc-dependent. The enzyme groups involve CTX-M, SHV, TEM and KPC (class A); VIM, IMP and NDM (class B); and class C (CMY and ADC). Class D involves oxacillinase (OXA) [3].

Class B (MBLs) consists of imipenemase (IMP) type, German imipenemase (GIM-1), SPM-1 and VIM types along with the NDM-1. The MBL enzymes can hydrolyze all β-lactams members from all classes except for aztreonam. The activity of MBL enzymes is inhibited by EDTA. MBL genes are often carried by mobile gene cassettes inserted into class 1 integrons [1].

Single reports and outbreaks of MBL enzymes have been detected in several countries. The NDM was reported in Palestine and Saudi Arabia [4,5]. The Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC-2) was documented in K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae isolates in Palestine [6]. VIM-2 and VIM-4 have recently been described in P. aeruginosa for the first time in Palestine [4]. The first report of VIM-4 in K. pneumoniae was presented in a recent study in Tunisia [7]. Interestingly, another recent study reported VIM-4-positive E. coli isolates recovered from patients from Kuwait [8]. VIM-28 was demonstrated in Egypt and Saudi Arabia in P. aeruginosa isolates [9,10].

There is a dearth of information on MBL producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the Middle East area, especially in Palestine. This is the first report of E. coli and K. pneumoniae clinical isolates producing VIM-4 and VIM-28 in Palestine. The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant isolates in hospitals in the Gaza Strip, Palestine and further to characterize these isolates.

Methods

Sample and data collection

This study was conducted for three months (April 2013 to June 2013) at three Palestinian hospitals in Gaza (Balsam Hospital, Dar Al-Shifa Hospital, and AL-Remal Health Center). All E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates from clinical specimens were considered; these isolates were obtained from patients who were already hospitalized in Balsam Hospital and Al-Shifa Hospital but the isolates were collected from AL-Remal Health Center mostly from the outpatient department.

A total of 96 isolates (69 E. coli and 27 K. pneumoniae) were obtained from April to June 2013. The clinical specimens collected were urine, wound swabs, blood and ear discharges. Only one isolate and one specimen per patient were processed. The samples were obtained before the patients had been treated. The isolates were transferred to Laboratoire des Microorganismes et Biomolécules Actives-Tunis for the rest of the work.

The identification of the isolates was performed by API 20E systems (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) to identify bacterial isolates at the species level. The E. coli isolates were confirmed by PCR of the uidA gene (F,5′ATCACCGTGGTGACGCATGTCGC3′; R,5′CACCACGATGCCATGTTCATCTGC-3′) [11]. The confirmation of K. pneumoniae isolates was based on the amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Susceptibility testing to 15 antibiotics was performed for all isolates by the Kirby-Bauer test according to the CLSI recommendations [12], using antibiotic disc panels comprising: cefoxitin, ceftazidime, ampicillin, cefotaxime, amikacin, tobramycin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, gentamicin, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, kanamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline and chloramphenicol. The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of imipenem were tested by the agar dilution method in nine isolates [7].

Phenotypic detection of MBL

The double-disc synergy test of imipenem-EDTA was used to screen for MBL production in all isolates. We used an overnight culture of K. pneumoniae and E. coli, which was inoculated on a plate of Mueller-Hinton agar. After drying, a blank filter paper disk with 10 µL of 0.5 M EDTA solution and a 10 µg imipenem disk were placed 10 mm apart from edge to edge. After overnight incubation, the EDTA-synergy test was positive by the presence of an enlarged zone of inhibition [13].

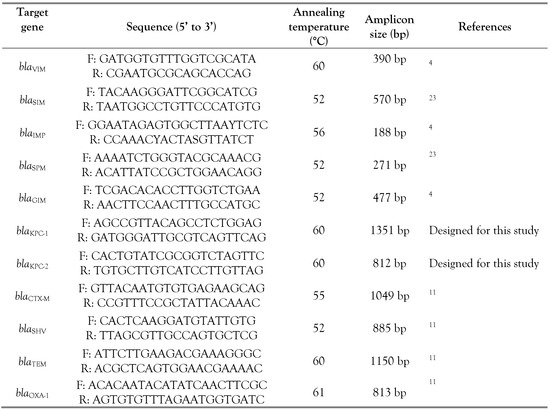

Detection and characterization of β-lactamases

PCR amplification was performed for the detection of MBL-genes (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaSPM, blaSIM and blaGIM) [4], ESBL-genes (blaOXA, blaTEM, blaCTX-M and blaSHV) and blaKPC-1,2. Positive PCR products were sequenced and the sequences were blasted in the database of GenBank to confirm the type of β-lactamase genes (Table 1) [8,11]. The carbapenem-resistance genes were assessed in the Ambedkar Centre for Biomedical Research (ACBR)—India.

Table 1.

PCR primers used for the analysis of the β-lactamase genes.

The bacterial genomic DNA was used as the template, the amplification of PCR was carried out for the searched gene in a final volume of 25 µL reaction. The PCR program consisted of three steps, the denaturation: 94 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 30 s at specific temperature (Table 1) and the extension step at 72 °C for 1 min and the final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products fragments were separated on 1.5% agarose gel by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Detection of antimicrobial resistance to non-β-lactam agents

The presence of antibiotic resistance genes for sulfamethoxazole (sul1, sul3 and sul2), tetracycline [tet(A), tet(B), and tet(C)] and gentamicin [aac(3)-IV, aac(3)-I, and aac(3)-II] was identified by PCR [11]. The resistance genes for quinolones [qnrA, qnrS, qnrB, aac(6′)-1b, and qepA] were also investigated in the isolates by PCR and further sequenced to recognize the variants. The presence of integron 1 was examined by PCR using the primer: (F: 5′GGGTCAAGGATCTGGATTTCG3′; R: 5′ACATGCGTGTAAATCATCGTCG3′). The qacEΔ1-sul1 genes in the 3′-conserved segment of integron were examined in the intI1-positive isolates. The variable region of integron was detected by PCR and sequencing [11].

PFGE analysis

The clonal relationship between MBL-producing isolates was identified by PFGE using the restriction enzyme XbaI as previously described [8]. Band pattern was compared by visual analysis by using GelCompar II program (version 6.5 Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium).

Results

Antibiotic resistance and phenotypic detection of MBL

All 27 K. pneumoniae and 69 E. coli isolates were tested for their susceptibility towards the selected antibiotic agents. We found that 4 E. coli (5.8%) and 5 K. pneumoniae (18.5%) isolates were imipenem-resistant. All isolates were resistant to cefotaxime, ampicillin, imipenem and kanamycin. The resistance rate for ceftazidime, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and tobramycin was quite high, at 88.9%. Resistance to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, cefoxitin and nalidixic acid among our isolates was 77.8%. However, we recorded lower resistance towards amikacin and tetracycline, 55.6%. The K. pneumoniae isolates (K457 and K894) exhibited high MIC values for imipenem (64 µg/mL). The total of nine carbapenem-resistant isolates showed an enhanced inhibition zone around the EDTA-IMP disk, indicating the production of metallo β-lactamases.

Detection of β-lactamase

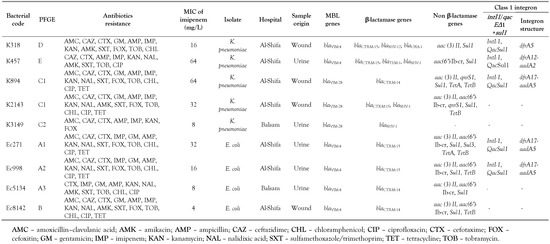

The identification of β-lactamase revealed the presence of the blaVIM-4 gene in four isolates of E. coli and two K. pneumoniae isolates; blaVIM-28 was detected in three K. pneumoniae isolates. We did not find any blaKPC-1 or blaKPC-2 producing isolates. Screening for other β-lactamase genes in the carbapenem-resistant isolates confirmed the presence of the following β-lactamase genes in the K. pneumoniae isolates: blaCTX-M-15 (n = 3), blaCTXM-14 (n = 1), blaSHV-1 (n = 3), blaSHV-12 (n = 1), blaTEM-1 (n = 1) and blaOXA-1 (n = 1). In the E. coli isolates, blaCTX-M-15 was found in three isolates and blaCTX-M-14 in one isolate (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the VIM-producing isolates detected in clinical samples.

Resistance to non-β-lactam agents

Other resistance genes were identified in the VIM-producing isolates: the sul1 gene was detected in eight isolates and aac(3)-II was identified in seven isolates. TetB and tetA were found in 5 isolates and 2 isolates, respectively. We found the aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene in four E. coli isolates and in two K. pneumoniae isolates. QnrS1 was demonstrated in two K. pneumoniae isolates. The class 1 integron was found in two E. coli isolates with the gene cassette: dfrA17-aadA5. Furthermore, intI1 was detected in 3 out of 5 VIM-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. The gene cassettes involved in the resistance to streptomycin (aadA2 and aadA5) and trimethoprim (dfrA5, dfrA12 and dfrA17) were present in different genetic arrangements: dfrA17-aadA5, dfrA12- aadA2 and dfrA5 (Table 2).

Clonal relationship by PFGE

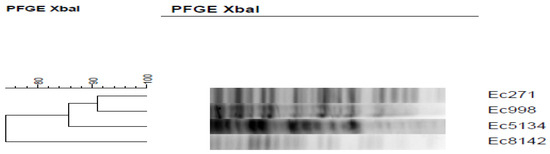

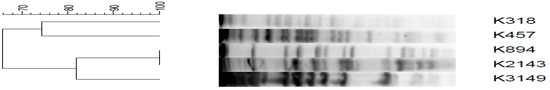

The genetic relatedness of the isolates ranged from 74% to 100%, and four distinct PFGE types were identified (Figure 1). The PFGE analysis demonstrated 3 unrelated pulsotypes among the 5 MBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. In contrast, the two K894 and K2143 isolates showed an indistinguishable PFGE pattern (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) dendrogram rooted from XbaI-digested E. coli strains.

Figure 2.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) dendrogram rooted from XbaI-digested K. pneumoniae strains.

The percentage of 80% is used to consider an isolate as belonging to a clonal group. Therefore, the E. coli isolates were included in two distinct clones A and B, the clone A with three subclones (A1, A2 and A3). The K. pneumoniae isolates were included in three distinct clones (C, D and E) and the clone C with two subclones (C1 n = 2 and C2 n = 1) (Table 2).

Discussion

A total of 96 clinical isolates (69 E. coli and 27 K. pneumoniae) obtained from Palestinian patients in Gaza strip during a three-month period were examined for the presence of β-lactamases encoding genes, associated resistance genes and integrons.

The blaNDM, blaKPC, blaIMP and blaVIM types are more important clinically and have been detected in clinical Gram-negative bacteria particularly in the Mediterranean region and the Far East [14]. The current study showed that 18.5% of K. pneumoniae isolates were MBL producers. Our results are similar to a Saudian study, which showed 21.7% prevalence of MBL in K. pneumoniae isolates [5], lower than that reported in Iraq (35.7%) among Gram-negative bacteria [13].

Our findings revealed that the prevalence of MBL in E. coli isolates was 5.8%. Data collected from different countries showed that the MBL rate was highest among the E. coli strains from Iraq (45.2%) [13]. In Lebanon, the MBL rate was 4% in Acinetobacter spp. [15]. In Egypt, the MBL-producing isolates in 85% of imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa were MBL-producing isolates with 29% of them harboring the blaVIM gene [16]. Therefore, carbapenems can be effective treatment options in E. coli isolates in our hospitals, which is in agreement with the recent report [17]. One of the significant findings of this study is the resistance to carbapenem found in isolates obtained from in-patients in Balsam Hospital and Al-Shifa Hospital.

In the present study, we found blaVIM-4 in the isolates. In a recent study, a first occurrence of blaVIM-2 and blaVIM-4 among P. aeruginosa isolates in Palestine was reported [4]. BlaVIM-4 was detected among K. pneumoniae and E. coli in Kuwait [8]. A VIM-type MBL (blaVIM-4) has recently been described among K. pneumoniae for the first time in Tunisia [7]. In Lebanon, blaVIM-2 was identified in clinical P. aeruginosa [18]. A Jordanian study has proved the presence of blaVIM, blaIMP, and blaNDM-1 in uropathogenic E. coli [19].

The current finding of blaVIM-28 is the first report in Palestine, which was demonstrated the first time in Middle East in Egypt among P. aeruginosa isolates [9]. Recently, this gene was reported in P. aeruginosa isolates in Saudi Arabia [10]. In contrast, among the MBL enzymes described in K. pneumoniae isolates, blaIMP-1 has been detected in Lebanon [20]. The blaGES-23 and blaKPC-2 genes were documented in K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae isolates from rectal samples [6].

Recently, the prevalence of MBL in E. cloacae isolates was 14% among different hospitals in West Bank. They have found blaIMP, blaSPM, blaIMP and blaSIM [21]. In the Gaza strip, the presence of blaOXA-48 was identified for the first time in urine in Proteus mirabilis [22]. The emergence of blaVIM-4 in our hospitals will pose challenges for the treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections.

The simultaneous production of three β-lactamase types (VIM-4, -28, CTX-M-14, -15, and SHV) in K. pneumoniae isolates is remarkable. The existence of two genes, an ESBL and MBL, in the same isolate has been reported in Enterobacteriaceae, with both CTX-M and VIM-1 [23], and VIM-4 and CTX-M-15 [7]. The coexistence of MBLs and ESBLs in the same bacteria shows the important resistance genes; it is worrying since it could predict the spread and generation of MDR strains and the consequent treatment failure that can lead to significant mortality and morbidity.

In our study, class I integron was detected in blaVIM-producing isolates with various arrangements of gene cassettes (aadA2 and aadA5) and (dfrA5, dfrA12 and dfrA17). The presence of the integron could increase the risk of spread and linkage to resistance genes. In Greece, the MBL was documented in an E. coli isolate that carried blaVIM-1 with aacA7, aadA and dhfrI in a class I integron [24].

In this study, all MBL-producing strains exhibited the multidrug resistance pattern along with the resistance to most non-β-lactams and β-lactams and this could be demonstrated by the fact that the β-lactamase isolates often carry an MDR-plasmid, and these carry resistance genes of non-β-lactam and β-lactam antibiotics [8]. These results highlight the alarming finding of MDR isolates producing MBL and ESBL.

The two K894 and K2143 isolates that belonged to the same clonal group and showed an indistinguishable PFGE pattern, were obtained from the same hospital (Al-Shifa), the same ward (Burn Unit) and the same week.

In our isolates, β-lactamases (blaVIM and blaCTX-M) were found with qnrS1 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr, a similar structure has been identified [25].

Our data focus on the emergence of isolates producing both CTX-M-ESBL and VIM-MBL transferable enzymes in Palestine and highlight the importance of detecting the association with other resistance agents and focusing on their MDR patterns. The presence of MBLs with ESBLs in the clinical isolates of

Enterobacteriaceae is a significant and emerging resistance concern due to a potential consequent failure of antibiotic therapy that can lead to significant mortality and morbidity.

Conclusions

This is the first report of E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates producing VIM-4 and VIM28 in Palestine. The occurrence of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant isolates in Palestine is alarming, since it endangers treatment with carbapenems; this class of antibiotics still represents a major therapeutic option for these infections, which are highly prevalent in most Palestinian hospitals. Our study highlighted the possible risk of the dissemination of multi-resistant bacteria and showed a linkage between blaVIM and blaCTX-M in the presence of qnrS1 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr. This data reveals the necessity for a regular screening to detect MBL and ESBL-positive isolates circulating in Gaza hospitals, which can be an effective step in treating the infections.

Author Contributions

GT designed the study, performed the experimental work (the microbiological and molecular tests), collected the data, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. DN helped in performing the experimental part and interpreting the molecular part. RBS, VV and SC helped in performing the experimental part of the manuscript. AB participated in study design. MY supervised the study and contributed to final writing and editing the manuscript. KBS designed the study and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Technology and partly supported by the Centre for Science & Technology of Non-Aligned and Other Developing Countries, New Delhi, India (Ref. No. NAM-05/74/2015). GT is recipient of RTF-DCS fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors—none to declare.

References

- Walsh, T.R.; Toleman, M.A.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Metallo-beta-lactamases: The quiet before the storm? Clin Microbiol Rev 2005, 18, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmanama, A.A.; Laham, N.A.; Tayh, G.A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial isolates from burn units in Gaza. Burns 2013, 39, 1612–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tooke, C.L.; Hinchliffe, P.; Bragginton, E.C.; et al. β-lactamases and β-lactamase inhibitors in the 21st century. J Mol Biol 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjölander, I.; Hansen, F.; Elmanama, A.; et al. Detection of NDM-2-producing Acinetobacter baumannii and VIM-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Palestine. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2014, 2, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibl, A.; Al-Agamy, M.; Memish, Z.; Senok, A.; Khader, S.A.; Assiri, A. The emergence of OXA-48- and NDM-1-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis 2013, 17, e1130–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddawi, R.; Siryani, I.; Ghneim, R.; et al. Emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (blaKPC-2) in members of the Enterobacteriaceae family in Palestine. Int Arabic J Antimicrob Agents 2012, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ktari, S.; Arlet, G.; Mnif, B.; et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing VIM-4 metallo-β-lactamase, CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase, and CMY-4 AmpC β-lactamase in a Tunisian university hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 4198–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, W.; Rotimi, V.O.; Albert, M.J.; Khodakhast, F.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. High prevalence of VIM-4 and NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Med Microbiol 2013, 62, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahdy, T.S. Identification of a novel metallo-β-lactamase VIM-28 located within unusual arrangement of class 1 integron structure in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Egypt. Jpn J Infect Dis 2014, 67, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Agamy, M.H.; Jeannot, K.; El-Mahdy, T.S.; et al. Diversity of molecular mechanisms conferring carbapenem resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Saudi Arabia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2016, 2016, 4379686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouini, A.; Vinué, L.; Slama, K.B.; et al. Characterization of CTX-M and SHV extendedspectrum β-lactamases and associated resistance genes in Escherichia coli strains of food samples in Tunisia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 60, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. Performance Standard of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Fourth International Supplement; CLSI Document M100-S24; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.S.; Ali, F.A. Detection of ESBL, AmpC and metallo beta-lactamase mediated resistance in Gram-negative bacteria isolated from women with genital tract infection. Eur Sci J 2014, 10, 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Emerging carbapenemases in Gram-negative aerobes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2002, 8, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar Soudeiha, M.; Dahdouh, E.; Daoud, Z.; Sarkis, D.K. Phenotypic and genotypic detection of β-lactamases in Acinetobacter spp. isolates recovered from Lebanese patients over a 1-year period. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018, 12, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raouf, M.R.; Sayed, M.; Rizk, H.A.; Hassuna, N.A. High incidence of MBL-mediated imipenem resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa from surgical site infections in Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries 2018, 12, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayh, G.; Al Laham, N.; Elmanama, A.; Slama, K.B. Occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of ESBL among Gram-negative bacteria isolated from burn unit of Al Shifa hospital in Gaza, Palestine. Int Arabic J Antimicrob Agents 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nawfal Dagher, T.; Al-Bayssari, C.; Diene, S.; Azar, E.; Rolain, J.-M. Emergence of plasmid-encoded VIM-2-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from clinical samples in Lebanon. New Microbes New Infect 2019, 29, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairoukh, Y.R.; Mahafzah, A.M.; Irshaid, A.; Shehabi, A.A. Molecular characterization of multidrug resistant uropathogenic E. coli isolates from Jordanian patients. Open Microbiol J 2018, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, Z.; Hobeika, E.; Choucair, A.; Rohban, R. Isolation of the first metallo-B-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Lebanon. Rev Espanola Quimioter 2008, 21, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Adwan, G.; Rabaya Da Adwan, K.; Al-Sheboul, S. Prevalence of β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae in the West Bank-Palestine. Int J Med Res Health Sci 2016, 5, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Al Laham, N.; Chavda, K.D.; et, at. First report of an OXA-48-producing multidrug-resistant Proteus mirabilis strain from Gaza, Palestine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 4305–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoulica, E.V.; Neonakis, I.K.; Gikas, A.I.; Tselentis, Y.J. Spread of blaVIM-1-producing E. coli in a university hospital in Greece. Genetic analysis of the integron carrying the blaVIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase gene. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2004, 48, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miriagou, V.; Tzelepi, E.; Gianneli, D.; Tzouvelekis, L.S. Escherichia coli with a self-transferable, multiresistant plasmid coding for metallo-β-lactamase VIM-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003, 47, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A.; Aschbacher, R.; March, A.; Larcher, C.; Livermore, D.M.; Woodford, N. Complete nucleotide sequence of the IncN plasmid pKOX105 encoding VIM-1, QnrS1 and SHV-12 proteins in Enterobacteriaceae from Bolzano, Italy compared with IncN plasmids encoding KPC enzymes in the USA. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010, 65, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

© GERMS 2025.