Abstract

Groundwater contamination in chemical industrial parks (CIPs) is a significant threat to global water security due to spills, leaks, and discharges, as well as the complexity of concealing a diverse range of industrial pollutants. In this article, we collected 30 groundwater samples from zones of presumed influence across a CIP, including upstream background, within-park, periphery, and downstream, located in Luxian County, Sichuan, China. We employed excitation–emission matrix (EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy with parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC) coupled with comprehensive hydrochemical analysis to deconvolve the dissolved organic matter (DOM) signature and statistically link its fluorescent components to specific hydrogeochemical processes and anthropogenic sources. Results revealed that industrial activities have transformed the groundwater to Ca-HCO3·Cl and Ca·Na-HCO3·Cl types from the hydrochemical facies comprising Ca-HCO3 and Ca·Mg-HCO3 types. Hydrogeology and groundwater chemistry depend primarily on weathering and atmospheric precipitation, but industrial effluents and evaporation concentration also significantly affect them. EEM-PARAFAC identified three dominant fluorescent components: fulvic-like (C1), humic-like (C2), and tryptophan-like (C3), with the latter serving as a sensitive indicator of recent anthropogenic inputs. The spatial distribution of these components, particularly the enrichment of C3, is primarily governed by anthropogenic inputs (e.g., sewage leakage), modulated by local hydrological conditions. This work demonstrates the integration of optical spectroscopy with conventional hydrochemistry for source apportionment in complex industrial settings. It provides a mechanistic understanding of pollution propagation and a practical, rapid diagnostic tool for targeted groundwater protection in CIPs.

1. Introduction

Groundwater constitutes a foundational freshwater asset that supports societal welfare and economic progress, ecosystem health, and water resource sustainability [1]. However, urbanization, industrialization, and other human activities have led to deterioration in groundwater quality in many areas [2], posing a serious threat to ecological integrity, sustainable development, and human health. Due to the hidden and complex nature of subsurface contamination, its traceability remains a challenge, especially for groundwater contamination in chemical industrial parks (CIPs) [3,4]. The chemicals used, and the resultant waste generated in chemical production processes, have the potential to enter the groundwater systems through seepage, leakage, or discharge [5], causing the groundwater in regions with CIPs contaminated with complex and varied amounts of organic and inorganic residues, dangerous chemical substances and various types of pollutants [6,7]. Therefore, it is imperative to implement rapid and accurate tracer techniques to identify pollution sources from multiple perspectives, aiming to establish a scientific foundation for the sustainable stewardship of groundwater resources, encompassing the preservation of environmental quality and safety, as well as the development of strategies for pollution containment and remediation [8]. Given the need for more targeted protection and treatment of groundwater in CIPs, it is imperative to conduct a cost-effective, efficient, and convenient traceability study of organic pollution in groundwater.

As a dynamic constituent of aquatic organic carbon, dissolved organic matter (DOM) serves as an effective proxy for tracing hydrological and geochemical pathways in groundwater systems. Its concentration, composition, and spectral characteristics provide more comprehensive environmental information than conventional parameters. Analyzing the components and relative contents of the DOM is an important indicator for identifying the sources, migration pathways, and transformation processes of water pollutants. It serves as an energy source for microorganisms, and as a crucial complexing group, DOM significantly affects the morphological distribution and activation migration of organic pollutants in the water environment. Since the 1990s, fluorescence spectroscopy has been a standard analytical technique for characterizing the composition and properties of DOM, and researchers have successively proposed a series of spectral parameters with significant diagnostic value.

The existing methods for tracing groundwater pollution include geophysical exploration, geochemical methods [9], stable isotope analysis [10], numerical receptor models [11,12], and Excitation-Emission matrix spectroscopy combined with parallel factor analysis (EEM-PARAFAC) [13,14,15,16]. EEM-PARAFAC is an emerging technique for traceability of organic pollutants, with multiple advantages: fast, non-destructive, highly sensitive, easy to handle, low-cost, and suitable for monitoring. This process minimises environmental risk by employing inherently benign reagents and avoiding hazardous chemicals [5,17,18]. However, this method has a limitation as it cannot visually assess the effects of anthropogenic–hydro–rock interactions. Water chemical analysis technologies can visually reflect information on hydro–rock interactions and human activities by analyzing changes in groundwater chemical components [19], primarily through graphical methods, ionic proportion relationships, and correlation analysis [20]. Therefore, the degree of influence of external activities on DOM in groundwater is assessed using EEM-PARAFAC to identify the factors that affect DOM. Secondly, it is linked to water chemical analysis to accurately determine the source of groundwater pollution, thereby ensuring that analysis results are more intuitive, realistic, and reliable. Several studies have examined DOM and the hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater [21,22]. However, the complex contamination patterns of organic and inorganic pollutants in CIPs, and the integration of EEM-PARAFAC and hydrogeochemical analysis for tracing groundwater pollution, remain limited.

This study focuses on a CIP located on the upper banks of the Yangtze River and characterized by the presence of pharmaceutical intermediates, benzene, and other organic chemicals. The deterioration of groundwater quality in this area poses a serious risk to the ecological integrity and long-term sustainability of the Yangtze River ecosystem. An investigation was conducted into the fate and behavior of DOM during subsurface migration, as well as the traceability of groundwater pollution, using EEM-PARAFAC, hydrochemical ion ratio analysis, principal component analysis, and other methods. This study aims to (i) map spatial patterns of groundwater hydrochemistry and DOM across the CIP, (ii) determine DOM spectroscopic features, sources, and transport pathways, and (iii) track groundwater pollution using PCA and EEM–PARAFAC coupled with hydrochemical evolution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

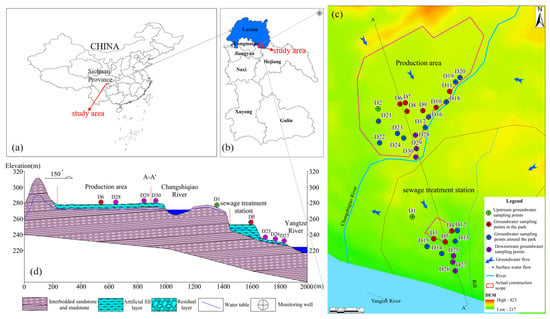

The studied chemical industry park (CIP) is located in the southeastern sector of Luxian County, Sichuan Province, on the north bank of the Yangtze River (105°37′17″–105°37′55″ E, 28°56′45″–28°56′49″ N). The landscape is predominantly a shallow, hilly, stripped terrain with relatively flat topography, increasing in the north and descending in the south. The main surface water bodies surrounding the park include the Changshiqiao River and the Yangtze River. The Changshiqiao River is the park’s sewage-receiving water body, traversing the park along a north–south longitudinal axis, with its ultimate effluent destination being the Yangtze River. Based on the park’s current construction status, it is primarily divided into two sections: the production area and the wastewater treatment plant area. The production zone is dedicated to pharmaceutical manufacturing, and the associated industrial wastewater is treated at the wastewater treatment plant. The outcrops of the park primarily consist of the Quaternary Holocene artificial filling layer (Q4ml), Quaternary Holocene residual layer (Q4el), and sandstone and sandy mudstone from the Middle Jurassic Upper Shaximiao Formation (J2s2). The groundwater runoff field in the park is primarily influenced by topography. The southern area, near the Yangtze and Changshiqiao Rivers, predominantly features loose rock pore water, whereas weathered fissure water is extensively distributed across the entire study area.

2.2. Sample Collection

Groundwater was sampled at 30 sites, with sampling locations presented in Figure 1c. The groundwater samples were categorized into four groups, designated Group 1 (two samples from the upstream), Group 2 (nine samples from within the park), Group 3 (thirteen samples from the park’s periphery), and Group 4 (six samples from the downstream). Prior to sampling, each well was purged for 20 min to remove stagnant water, after which groundwater was withdrawn. Sampling containers were preconditioned by triple-rinsing with site water. The collected water was then filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane and aliquoted for different analyses: anions and isotopes were stored in 50 mL polyethylene bottles; cation samples were preserved in 50 mL polyethylene bottles by adding HNO3 (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to maintain pH < 2 and were immediately capped for storage. Samples intended for DOM characterization were transferred to 40 mL amber (brown) glass vials. Escherichia coli was collected in 150 mL sterilized glass bottles. All groundwater samples collected were stored at 4 °C until analysis.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the study area in China; (b) Location of the study area in Luxian County; (c) Groundwater sampling sites in study area; (d) Geologic section of A-A′.

2.3. Analysis Method

The pH value was determined in situ with a portable multi-parameter instrument (DZB-712, INASE Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Chemical oxygen demand using permanganate (CODMn) and total hardness (TH) was determined by titration. Concurrently, total dissolved solids (TDS) were assessed gravimetrically. Concentrations of SO42− and Cl− were analyzed using ion chromatography (ICS-883, Metrohm China Limited, Hong Kong, China). Major cations (K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+) were quantified by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Optima 5100, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Bicarbonate (HCO3−) was determined separately by alkalinity titration [23]. E. coli was quantified using an incubation-based method with a biochemical incubator (SPX-250B-ZII, Shanghai Boxun Medical Biological Instrument Corp, Shanghai, China). Sterile containers and aseptic handling were used during collection and processing. Method blanks and duplicate measurements were included to verify the absence of contamination and to assess analytical reproducibility.

2.4. EEM and PARAFAC

EEM fluorescence spectra were measured using a Hitachi F-4600 spectrofluorometer (Tokyo, Japan; 150 W xenon lamp). Excitation wavelengths ranged from 200–500 nm, and emission wavelengths ranged from 250–600 nm, with 5 nm increments. The slit width was 2.5 nm, and the scan speed was 12,000 nm min−1. Raw EEMs were pre-processed by subtracting blanks, correcting inner-filter effects, and removing Rayleigh/Raman scattering. PARAFAC was applied to decompose EEM datasets into independent fluorescent components, allowing quantification of component abundance using maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax) and facilitating interpretation of DOM composition and sources [24]. To characterize DOM properties, fluorescence indices were calculated from EEMs, including FI, HIX, BIX, and freshness index (β:α), following established definitions [25,26,27].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

PARAFAC modeling of the EEM dataset (30 groundwater samples) was conducted in MATLAB R2024 (MathWorks. Inc., Natick, MA, USA) using the PARAFAC toolbox. The optimal solution resolved three fluorescent components, supported by split-half validation and residual diagnostics. The abundance of each PARAFAC-resolved component was quantified by its maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax). Subsequent data analysis, including principal component analysis (PCA) and Spearman rank correlation, was conducted using Origin 2024 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics

Descriptive statistics of key groundwater indices were used to obtain an initial overview of hydrochemical conditions in the study area [28,29]. The measured hydrochemical variables are summarized in Figure S1 and Table S1.

From Figure S1 and Table S1, it can be observed that the groundwater of CPI from upstream, around the park, and downstream was neutral freshwater with high hardness in general, in which the mean pH was 6.95, 6.98, and 7.10, respectively, the mean TH values were 326.2, 309.3, and 344.7 mg/L, and the mean TDS values were 468.5, 430.5, and 415.0 mg/L, respectively. The primary cations present were Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+ and K+. The mean of Ca2+ was 100.3, 84.68, and 98.97 mg/L, respectively. The average Mg2+ concentrations were 16.64, 21.62, and 22.72 mg/L, respectively. The means of Na+ were 36.81, 26.91, and 16.22 mg/L, respectively. The mean values of K+ were 2.48, 2.16, and 1.89 mg/L, respectively. The primary anions in the groundwater were SO42−, HCO3−, and Cl−. The mean HCO3− concentrations were 392.9, 318.9, and 276.3 mg/L, respectively. The means of SO42− were 49.65, 63.01, and 38.38 mg/L, respectively. The means of Cl− were 35.60, 40.45, and 81.52 mg/L, respectively. These results are similar to those from the investigation of the hydrochemical characteristics from the upper reaches of the Yangtze River by Li et al. [30].

It is worth noting that the TH, TDS, SO42−, Cl−, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and CODMn within the CPI exhibited significant variability compared to surrounding areas. This pattern is supported by the relatively large coefficients of variation (CVs), suggesting that industrial operations have substantially influenced groundwater within the CIP. While most samples showed SO42− < 90 mg/L, Cl− < 200 mg/L, K+ < 10 mg/L, Ca2+ < 100 mg/L, Mg2+ < 40 mg/L, TH < 500 mg/L, and TDS < 650 mg/L, isolated outliers were detected for each parameter. Notably, median TH and TDS within the park were 6 and 4 times higher than upstream, respectively, exceeding the Class IV limits (GB/T 14848-2017) [31]. TH reached 1.78 times the standard (650 mg/L), and TDS slightly surpassed its limit (2000 mg/L). Similarly, the CODMn within the park increased significantly, with the highest value being 7.8 times that of upstream, and the highest CODMn exceeded the standard by 2.25 times (the IV standard is 10 mg/L), indicating the degree of pollution from organic matter and some reducing substances in groundwater. Excessive CODMn content demonstrated that the groundwater within the CPI contains a substantial amount of oxygen-consuming organic matter, consistent with the situation where a considerable amount of organic matter is involved in the production processes of the CPI, further highlighting that the groundwater within the CPI was affected by the production activities. These observations are consistent with those from another similar industrial park in the southeastern part of Zhejiang Province, where the groundwater exceeds the IV standard [32].

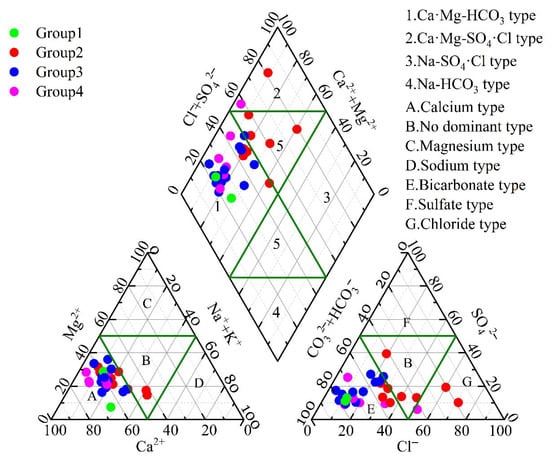

The types of groundwater hydrochemistry were determined by calculating the milliequivalents of the primary anions and cations in the samples [33]. The resulting chemical classifications of the groundwater are displayed in Figure 2. The dominant hydrochemical types in the study area included Ca-HCO3 and Ca·Mg-HCO3. However, a few samples demonstrated groundwater types such as Ca-HCO3·Cl, Ca·Na-HCO3·Cl, and Ca·Mg-HCO3·Cl. These different groundwater types are predominantly located within the park and in the downstream areas.

Figure 2.

Piper trilinear diagram of groundwater samples.

3.2. Recharge of Groundwater

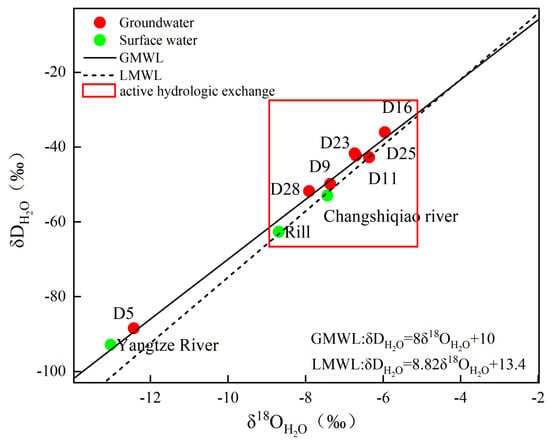

Variations in groundwater δ2H and δ18O provide robust constraints on recharge origins and hydraulic connectivity among interacting water bodies [34]. Reliable interpretation of these isotopes requires an appropriate precipitation baseline, commonly described by the local meteoric water line (LMWL) and the isotopic signature of atmospheric precipitation for the region of interest. In this study, precipitation isotope information from Zunyi was used as a regional reference for Luxian, because the two locations are geographically close (160 km apart) and share comparable physiographic and climatic settings (Both sites lie within the transitional belt between the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and the Sichuan Basin, characterized by a subtropical monsoon climate). Consequently, the Zunyi precipitation end-member and LMWL are expected to reasonably represent meteoric inputs relevant to Luxian for evaluating groundwater recharge and surface water–groundwater interactions. Therefore, the atmospheric precipitation line (LMWL) will adopt the hydrogen and oxygen isotope composition of precipitation in Zunyi [35]:

δD = 8.82δ18O + 13.4

Figure 3 shows that most groundwater samples cluster near both the GMWL (global meteoric water line) and the LMWL, suggesting that meteoric precipitation dominates groundwater recharge. In addition, δ18O and δD values show only limited variability among most groundwater samples, suggesting strong hydraulic connectivity among water bodies. By contrast, both surface water and groundwater deviate from the LMWL and plot above it, implying that evaporation exerts a dominant control on the enrichment of hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes. The isotopic composition (δD and δ18O) of groundwater largely overlaps with that of the Changshiqiao River and rill water, suggesting active hydrologic exchange between these compartments. However, the delta D and delta 18O values of the Yangtze River are distinctly more negative than those of the groundwater, indicating that the hydraulic connectivity between the Yangtze River and the groundwater system is relatively weak.

Figure 3.

A plot depicting the δ2H and δ18O signatures of water samples.

3.3. Factors of Chemical Control of Groundwater

Hydrochemical characteristics and anthropogenic controls on groundwater quality can also be analyzed by studying the process of groundwater chemical evolution. In the present study, the Gibbs diagram was used as a methodological tool to evaluate the mechanisms governing the hydrochemical formation of groundwater (Figure S2). As indicated in Figure S2, the preponderance of groundwater samples was clustered in the mid-left section of the diagram, signifying that the ionic composition was predominantly derived from rock weathering processes. However, distinct evaporation and concentration effects were evident in groundwater from sites D4, D7, and D9 within the park, as well as site D25 downstream.

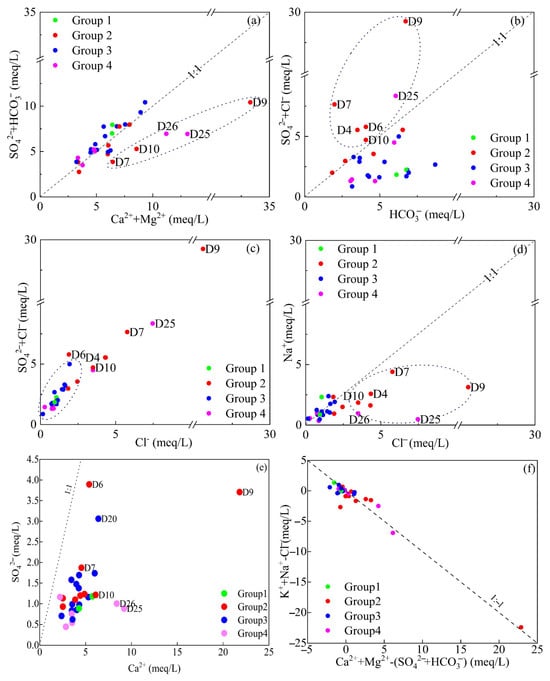

The ratio of SO42− + HCO3−/Ca2+ + Mg2+ was <1 at most sample points (Figure 4a), suggesting that the weathering and dissolution processes of the carbonate mainly control groundwater in the study area. However, several points within the park area (D7, D9 and D10) and downstream (D25 and D26) were found to be below the contour line, indicating excess Ca2+ and Mg2+ at these locations. This imbalance indicated the need for additional anions to maintain charge balance in the groundwater at these sites. The ratio of SO42− + Cl−/HCO3− was >1 (Figure 4b), revealing that the sample points within the park (D4, D6, D7, D9 and D10) and downstream (D25), contained dominant high levels of SO42− + Cl−, breaking away from the control of carbonate weathering. These sites are significantly influenced by one or more processes such as evaporation concentration, sulfate rock dissolution, or human activity pollution. The Cl−/(SO42− + Cl−) ratio (Figure 4c) shows that the sample points within the park (D4, D6, D7, D9 and D10) as well as those downstream (D25) are far from the starting points, indicating that these locations have been significantly affected by evaporation concentration or pollution from human activities or agriculture.

Figure 4.

Bivariate plots of SO42− + HCO3−/Ca2+ + Mg2+ (a), SO42− + Cl−/HCO3− (b), SO42− + Cl−/Cl− (c), Na+/Cl− (d), SO42−/Ca2+ (e), Ca2+ + Mg2+ − SO42− − HCO3−/K+ + Na+ − Cl− (f).

The Na+/Cl− ratio was <1 (Figure 4d) at the outlier sites (D4, D7, D9, D10 and D25), suggesting that these locations were influenced by external chlorinated wastewater sources, including domestic sewage and industrial effluents. The presence of Cl−, a key pollutant in the chemical park, further supports the hypothesis that these sites were affected by activities within the park. Moreover, chlorine is primarily used as a tracer to identify groundwater contamination from domestic sewage [36]. Hydrochemical analysis indicated that the anomalies were primarily located within the park area. The Ca2+/SO42− were <1 (Figure 4e), indicating that the groundwater is less affected by the dissolution of gypsum and other sulfate rocks. The relationship between (Ca2+ + Mg2+ − SO42− − HCO3−) and (K+ + Na+ − Cl−) (Figure 4f) shows a clear trend consistent with cation exchange, providing additional evidence that ion-exchange reactions occur within the groundwater system.

3.4. Fluorescence Characteristics and Composition of DOM

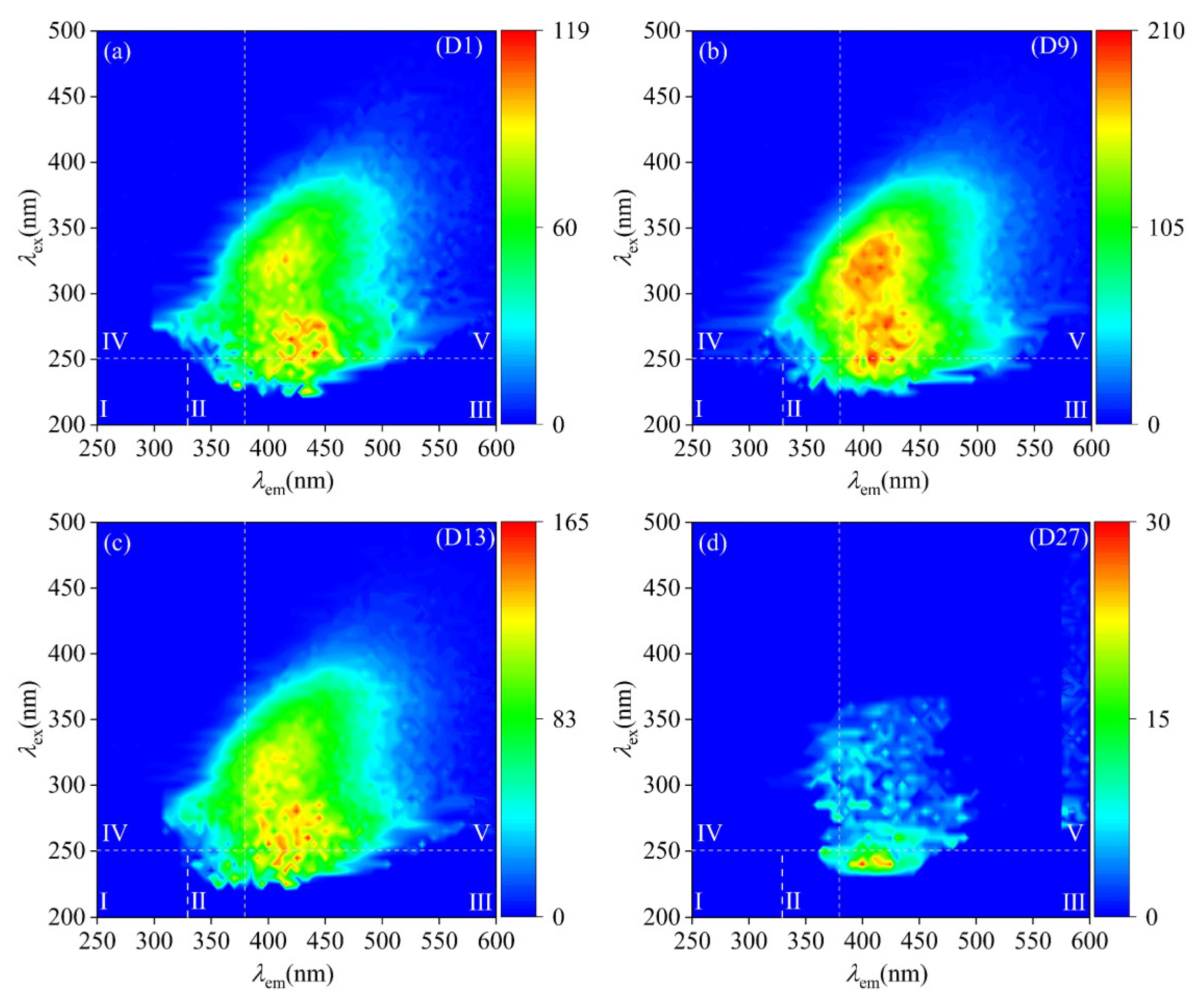

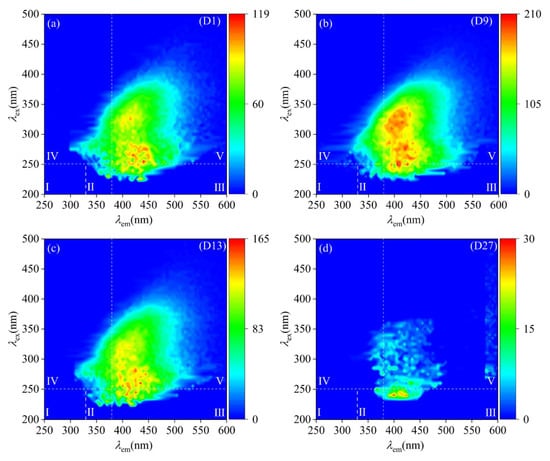

The characteristics of DOM in groundwater are influenced by external factors, resulting in subsequent changes in its composition [37]. The comparison of the EEM fluorescence spectra of groundwater samples from various spatial locations within the study area (Figure 5) indicated that the DOM of groundwater upstream and around the park area exhibited similar spectral characteristics, as evidenced by two prominent fluorescence peaks in zone V, the location is specified as being at Ex/Em = 270/425 nm and 330/420 nm. The natural DOM within the study area was predominantly composed of humic-like substances. In contrast, the DOM in the groundwater within the park exhibited EEMs spectral characteristics that differed from those of natural DOM. The fluorescence intensity of the groundwater increased, with a distinct peak observed in region IV at Ex/Em = 260/365 nm.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence spectra of groundwater samples from various spatial locations (a) from the upstream; (b) within the park; (c) from the park’s periphery; and (d) from the downstream.

The composition of DOM of groundwater was investigated by three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy combined with PARAFAC, as shown in Figure S4. Component C1 was identified as a fulvic-like fluorescent component [38], demonstrating two excitation peaks: peak a (Ex/Em = 245/410 nm) and peak b (Ex/Em = 325/410 nm), corresponding to the A peak and M peak of fluorescent substances, respectively. Furthermore, C1 can be identified as a mixture of traditional A and M peaks. Such a component is generally characterized by a relatively low degree of humification, reduced molecular structure aggregation, and weaker chemical stability. It is predominantly derived from terrestrial sources or microbial processes. Component C2 was determined as a humic-like fluorescent component [39], demonstrating two excitation peaks, including peak c (Ex/Em = 265/460 nm) and peak d (Ex/Em = 360/460 nm), corresponding to the A peak and C peak, respectively. Component C2 can be identified as a mixture of the traditional A and C peaks. This component is typically more humified, with a higher molecular mass, and originates from diverse sources, including streams, agriculture, rivers, wastewater, soil exudates, and plant and animal residues. Component C3 (Ex/Em = 275/375 nm) was identified as a protein-like substance, specifically a tryptophan-like substance [40], which is commonly found in landfill leachate and is also affected by microorganisms carried by domestic sewage inputs.

3.5. Sources of DOM in Groundwater

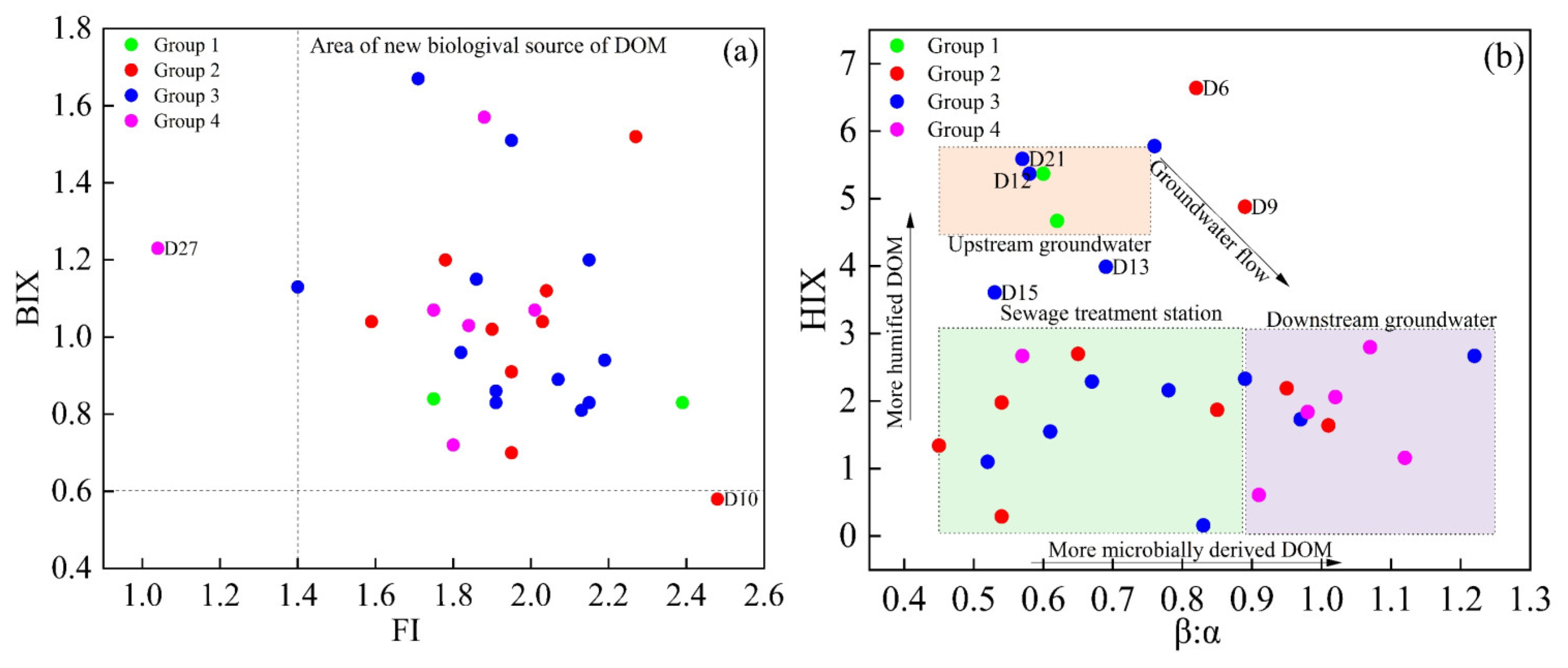

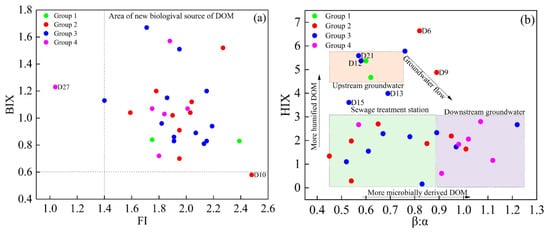

The fluorescence parameters, including FI, BIX, HIX, and the β:α ratio, were used to analyze biogeochemical processes of DOM in groundwater and elucidate its sources [26]. An FI value less than 1.4 suggested that terrestrial inputs were the primary contributors, whereas an FI value greater than 1.9 indicated a predominance of microbial sources. A BIX value below 0.6 indicated that DOM primarily originates from terrestrial sources, while a BIX value above 0.8 signified a higher proportion of autochthonous DOM [41].

As shown in Figure 6a, 93.3% of the groundwater samples in the study area exhibited FI values above 1.4 and BIX values exceeding 0.6, indicating that microbial sources dominated the DOM, with a significant contribution from autochthonous processes. However, the BIX of D10 was less than 0.6, but FI was greater than 1.9, suggesting that the DOM at this location was primarily derived from external sources. Moreover, the FI value of D27 was below 1.4, and BIX was less than 1.0, indicating that the DOM at this point principally originated from terrestrial origin. As shown in Figure 6b, HIX generally decreased, whereas β:α showed an increasing trend in the direction of groundwater flow. These findings suggest a reduction in the humification of groundwater DOM. However, the data derived from points D6 and D9 within the park, as well as D12 and D21 around the park, deviated from this pattern.

Figure 6.

Relationship among BIX and FI (a), HIX and β:α (b) of DOM in groundwater.

Mechanistically, this spatial trend can be explained by two coupled processes during subsurface transport: (1) selective attenuation of humic-like via adsorption/co-precipitation onto aquifer minerals, which preferentially removes aromatic, high-molecular-weight fractions and lowers HIX; and (2) an increase in labile, protein-like organic matter driven by microbial activity and inputs of DOM from external wastewater sources, resulting in higher β:α values and a reduced degree of humification in the groundwater.

3.6. Characteristics of Migration and Transformation of DOM in Groundwater

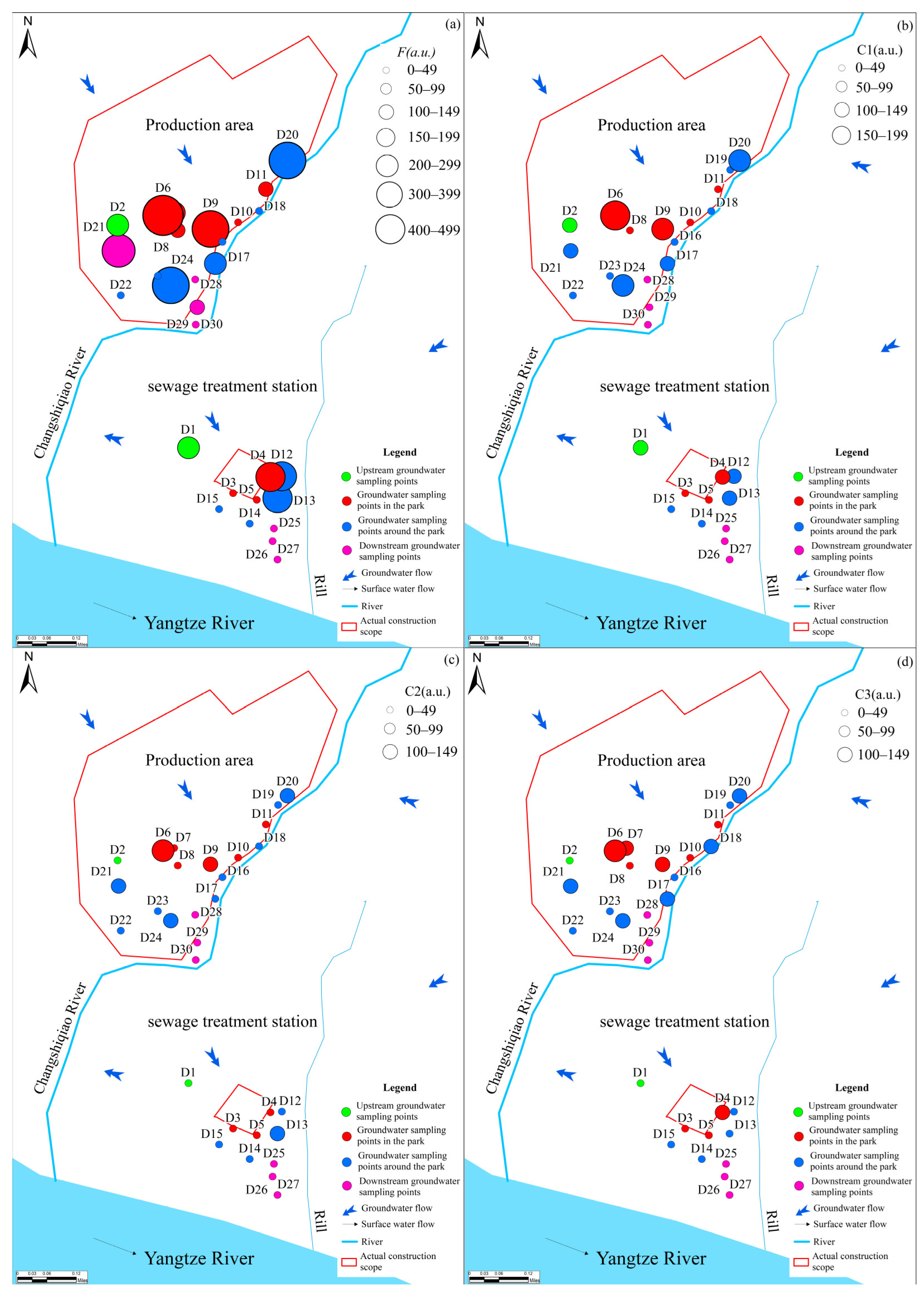

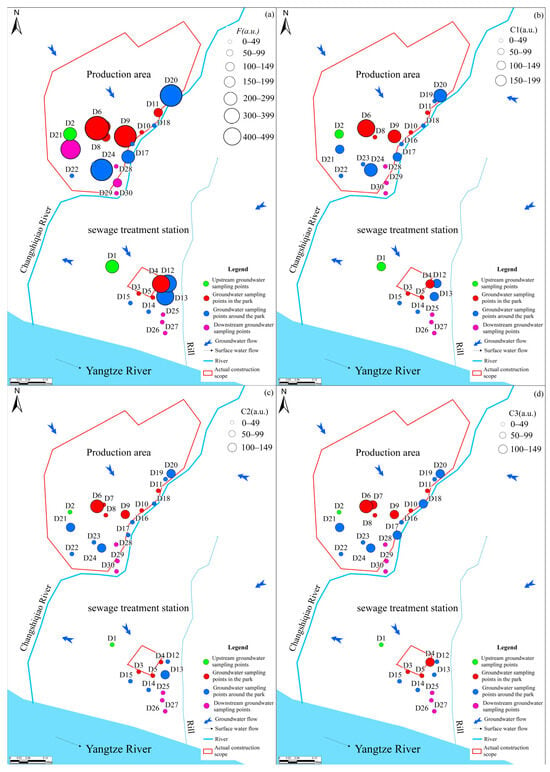

A considerable number of studies have demonstrated that the marked variability in DOM fluorescence intensity across spatial locations reflects pollution of groundwater by external activities [42]. Fluorescence intensity for the three fluorescent components across different spatial locations in the park (Figure 7a) shows that the proportion of sampling points with increased fluorescence intensity within the park is 33.3%, and the proportion of sampling points with decreased fluorescence intensity is 44.4% compared to upstream groundwater points. Around the park, the proportions of sampling points with increased and decreased fluorescence intensity were 30.8% and 46.1%, respectively. In the downstream area, the proportion of sampling points with decreased fluorescence intensity was 83.3%.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence intensity at different sites of DOM (a), C1 (b), C2 (c) and C3 (d).

Analysis of the percentages of the three identified components revealed minimal relative changes across the C1 and C2 components in the upstream, within the park, and around the park (Figure 7b,c). The observed results were primarily associated with the fact that C1 and C2 are small-molecule organic substances that are more resistant to degradation. However, a substantial increase in the C1 component, accompanied by a decrease in the C2 component, was observed in the downstream area. Moreover, the C3 component showed substantial variation across the study area (Figure 7d). 55.6% of sampling points within the park showed an increase in C3 content, while 22.2% showed a decrease. Around the park, the proportions of the increased and decreased sampling points are 61.5% and 30.8%, respectively. In the downstream area, the proportions of sampling points where the C3 component increased and decreased were 16.7% and 66.7%, respectively. Prior studies have shown that increased intensity and relative contribution of tryptophan-like fluorescence are often associated with heightened contamination potential [43]. Consistent with this interpretation, the observed DOM levels and fluorescence signatures indicate that groundwater has likely been influenced by anthropogenic activity. The analyses showed significant differences in the direction of organic matter in groundwater along the flow direction.

The analysis revealed significant variations in organic matter along the trajectory of the groundwater flow path. The described variations were associated with upstream groundwater primarily recharged by atmospheric rainfall. The DOM from the soil enters the surface air inclusion zone through water erosion, where it is used and absorbed by microorganisms and is eventually released into groundwater as endogenous organic matter. The groundwater within the park was located in the sand and pebble layer, which typically had large pores and other water-retaining spaces that facilitate microbial activity. Combined with wastewater leakage from the park, such an environment accelerates the production of organic matter in the groundwater. The groundwater around the park also supports microbial activity, as it lies within sand and pebble layers. However, the percentage of the C3 component was slightly lower compared to the park area, probably due to the absence of wastewater.

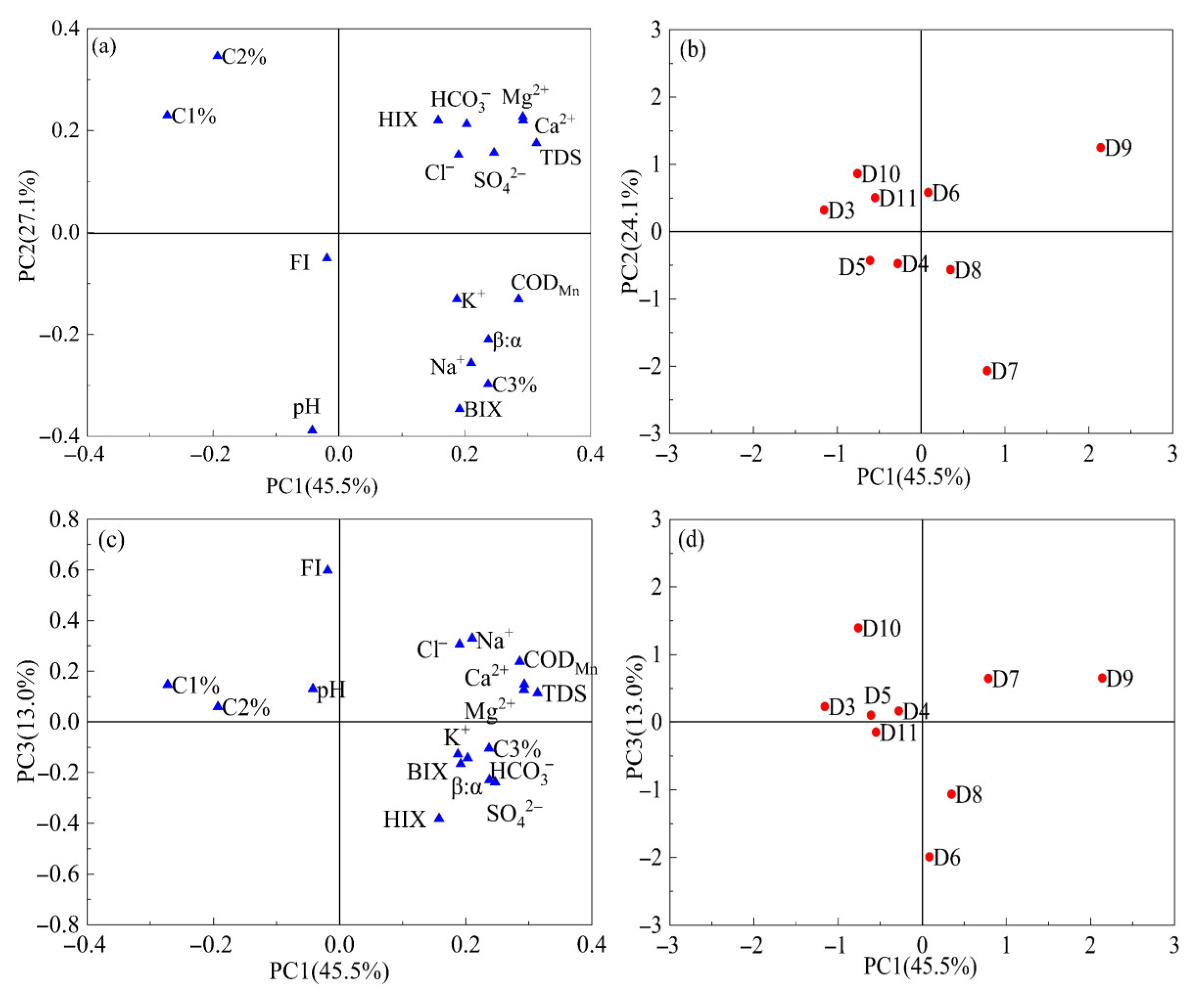

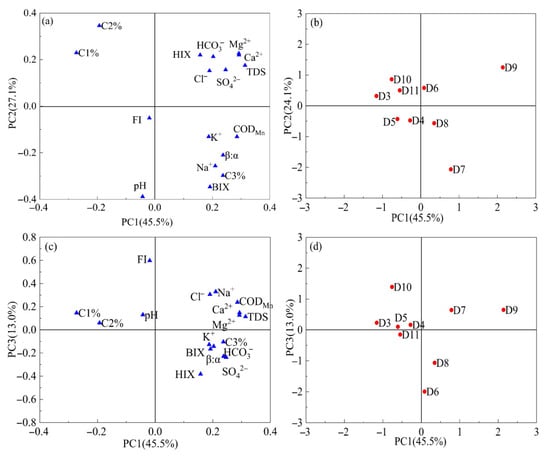

3.7. Traceability of Groundwater Pollution

We used PCA to summarize multivariate variability of DOM indicators (FI, HIX, BIX, β:α, C1%, C2%, and C3%) and hydrogeochemical parameters (Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and CODMn) for the park area sites to investigate the factors influencing changes in DOM in groundwater within the park area. The loadings of each variable on the three principal component axes are shown in Figure 8. The initial three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) accounted for 45.5%, 27.1%, and 13.0% of the observable variance, respectively, collectively explaining over 85.6% of the total variance.

Figure 8.

Loadings (variables) (a,c) and scores (samples) (b,d) diagram of PCA for optical indices and fluorescence components of DOM and hydrogeochemical parameters (Cl−, Na+, SO42−, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, HCO3−, CODMn and TDS) within the park of groundwater.

As shown in Figure 8a, variables C3% and BIX were identified on the positive side of PC1, indicating that PC1 was correlated with protein-like substances. Furthermore, SO42− and Cl− were identified on the positive side of PC1, suggesting that DOM was primarily affected by microbial activity and domestic sewage, with chloride reflecting external wastewater inputs. In contrast, higher BIX and C3% indicate that microbial activity increases the abundance of labile (biodegradable) DOM in groundwater. In contrast, the loading directions of C1% and C2% are opposite to PC1, suggesting that humic-like components are negatively correlated with the sewage/microbial signature, implying that wastewater inputs and enhanced microbial activity reduce the relative contribution of humic-like fractions in groundwater.

The variables C1%, C2%, and HIX were identified as positively associated with PC2, indicating that PC2 was associated with humic substances. PC2 shows high loadings of HIX together with Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3−, and TDS (Figure 8a), indicating that water-rock interactions and longer residence times promote higher ionic strength while favoring the formation of more humified DOM. This is consistent with previously reported links between water-rock interactions and DOM humification by Yi et al. [44]. Therefore, PC2 can be interpreted as a “water-rock interaction/humification” factor. PC3 is mainly associated with CODMn and major ions (particularly Cl− and Na+) in the positive PC3 direction (Figure 8c), separating samples with high oxidizable organic matter and elevated salinity from those dominated by higher HIX and sulfate/bicarbonate signatures. This pattern suggests that PC3 captures an additional high-organic-load wastewater (industrial/urban) input, a factor that is partly independent of the microbial/biological freshness gradient represented by PC1.

The score plots further corroborate these factor interpretations. As shown in Figure 8b, groundwater samples D7, D8, and D9 were identified on the affirmative side of PC1, suggesting that the DOM in these samples was primarily affected by domestic sewage from the surrounding industrial areas. The described finding was further supported by field observations, which identified septic tanks near site D8. Moreover, E. coli levels in the groundwater of D7, D8, and D9 were higher than those in the upstream groundwater (Table S2). It indicates that groundwater pollution in D7, D8, and D9 is linked to septic tank leaks. Samples D3, D6, and D11 were located on the positive side of PC2, indicating that hydro-rock interactions also influenced the DOM at these sites. Furthermore, samples D4, D5, and D10 were located on the positive side of PC3 in Figure 8d, indicating that DOM at these points was significantly affected by industrial wastewater infiltration.

3.8. Challenges and Limitations of the Current Study

This study conducted a comprehensive assessment of the hydrogeochemical characteristics and DOM properties of groundwater within and around the CIP. However, it must be acknowledged that there are some inherent challenges and limitations. Firstly, the chemicals present in groundwater and the characteristics of dissolved organic substances are dynamic and can fluctuate significantly due to seasonal precipitation, changes in industrial emissions, and variations in hydrological conditions. Due to the lack of seasonal or high-frequency time data, it is impossible to assess the persistence of pollution, the dilution effect during the rainy season, or the long-term evolution of the pollution zone. Secondly, although the combination of multivariate statistics (principal component analysis) and fluorescence spectroscopy is very effective for identifying potential pollution sources and the composition of dissolved organic substances, it cannot provide clear evidence of specific pollution sources or transformation mechanisms. Finally, the range of considered anthropogenic factors may not be comprehensive. In conclusion, these limitations highlight the complexity of the groundwater system in industrial areas. The study’s findings offer a robust preliminary diagnosis of the pollution problem. Future work is recommended to incorporate long-term monitoring, detailed hydrogeological models, and advanced organic geochemical tools to transition from qualitative source allocation analysis to quantitative risk assessment and to support more targeted remediation strategies.

In a chemically complex environment such as the CIP, source apportionment based on a single technique may involve substantial uncertainty. Hydrochemistry constrains water-rock interactions and geochemical evolution, but it may not differentiate sources with similar inorganic signatures. EEM-PARAFAC provides sensitive fingerprints of fluorescent DOM; however, fluorescence signals are not source-specific and can be altered during transport by biodegradation, sorption, and dilution. Dual water-isotope ratios (δ2H and δ18O) provide independent constraints on hydrological processes by distinguishing recharge sources and evaporation or mixing effects. Yet, they do not directly resolve organic composition or specific anthropogenic inputs. Therefore, integrating EEM-PARAFAC with hydrochemical evolution and δ2H/δ18O evidence helps reduce equifinality: isotopes constrain water sources and mixing pathways, hydrochemistry captures inorganic reactions and plume evolution, and fluorescence characterizes DOM composition associated with potential contamination. This integrated approach yields a more internally consistent interpretation of pollution sources and migration pathways than any single method alone.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes a practical framework for rapidly identifying, tracking, and evaluating groundwater contamination associated with a chemical industrial park (CIP) by integrating EEM-PARAFAC with hydrochemical parameters and stable isotopes. This approach is cost-effective and sensitive to changes in DOM signatures and water chemistry. The primary conclusions can be summarized as follows:

(1) The main types of groundwater chemistry are Ca-HCO3 and Ca·Mg-HCO3. Due to human activities, the types of groundwater chemistry have changed to Ca-HCO3·Cl and Ca·Na-HCO3·Cl. (2) Ion ratios and δ2H-δ18O indicate that water-rock interaction predominantly controls groundwater chemistry. However, sites within and downstream of the CIP deviate from natural weathering, showing evaporation-driven concentration and anthropogenic signatures, particularly Cl−-rich wastewater inputs. Isotopes further suggest precipitation-dominated recharge and strong hydraulic connectivity across the area. (3) EEM-PARAFAC resolved three dominant fluorescent components, namely fulvic-like (C1), humic-like (C2), and tryptophan-like (C3). Groundwater samples collected within the CIP exhibited markedly elevated total fluorescence and clear compositional shifts, particularly an enrichment of the protein-like C3 component. These patterns suggest an increased contribution of microbially derived and locally produced DOM. Fluorescence index values indicate that DOM in the CIP groundwater is strongly influenced by wastewater inputs and associated microbial activity linked to sewage leakage. (4) By integrating multiple techniques, we demonstrate that the C3 component and Cl− serve as robust co-tracers for sewage leakage, and that the proposed framework provides a rapid screening tool to prioritize zones for detailed investigation and monitoring in CIPs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14030568/s1: Figure S1: Statistical analysis of chemical parameters in groundwater samples. Figure S2: Gibbs diagram of groundwater samples in the Chemical Industrial park; Figure S3: Excitation-emission fluorescence spectra of groundwater samples; Figure S4: The excitation-emission matrix spectra of fluorescence components, including component 1 (C1, fulvic-like substance), component 2 (C2, humic-like substance) and component 3 (C3, tryptophan-like substances), identified by PARARAC model; Figure S5: The correlation between the proportion of C3 component and Escherichia coli and the concentrations of Cl−; Table S1: A statistical summary of groundwater chemical composition; Table S2: Statistical table of E. coli in Groundwater.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L. (Guo Liu); methodology, G.L. (Guo Liu) and G.L. (Guoming Liu) and Y.Z.; software, G.L. (Guo Liu); validation, G.L. (Guo Liu), Y.Z. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, G.L. (Guo Liu); investigation, G.L. (Guo Liu) and Y.Z.; resources, G.L. (Guo Liu); data curation, G.L. (Guo Liu) and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L. (Guo Liu) and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.L. (Guo Liu) and G.L. (Guoming Liu); visualization, G.L. (Guo Liu); supervision, G.L. (Guo Liu) and G.L. (Guoming Liu); project administration, G.L. (Guo Liu); funding acquisition, G.L. (Guo Liu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2023YFC3207300).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Guo Liu was employed by the State Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention and Geoenvironment Protection, and Author Guoming Liu was employed by the State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture, Institute of Soil Science. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Gleeson, T.; Cuthbert, M.; Ferguson, G.; Perrone, D. Global Groundwater Sustainability, Resources, and Systems in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 431–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapworth, D.J.; Boving, T.B.; Kreamer, D.K.; Kebede, S.; Smedley, P.L. Groundwater quality: Global threats, opportunities and realising the potential of groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.J.; Xin, C.L.; Du, W.Y.; Yu, S. Health risk assessment of heavy metals based on source analysis and Monte Carlo in the Lijiang River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 176, 113620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.H.; Wei, S.Y.; Chen, Y.D.; Ning, Q.; Hu, Z.; Guo, Z.Z.; Xie, H.J.; Wu, H.M.; Zhang, J. Fluorescence spectroscopic characterization of dissolved organic matter in the wastewater treatment plant and hybrid constructed wetlands coupling system in winter: A case study in eastern China. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, Q.L.; Ding, J.; Li, L.L.; Wang, K.; Zhou, H.M.; Jiang, M.; Wei, J. Sources, characteristics, and in situ degradation of dissolved organic matters: A case study of a drinking water reservoir located in a cold-temperate forest. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.B.; Qiao, B.T.; Yao, Y.M.; Zhao, L.C.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.Y.; Sun, H.W. Target and nontarget analysis of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in surface water, groundwater and sediments of three typical fluorochemical industrial parks in China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Xing, W.L.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Wang, S.K.; Jiang, K.X.; Tang, W.W. Highly efficient antibiotic decontamination and biotoxicity elimination with activity-stability considerations via encapsulated catalyst induced peroxymonosulfate activation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 396, 128078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, B.L.; Liu, Z.S.; Yan, X.L.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Liang, T. Utilizing machine learning algorithm for finely three-dimensional delineation of soil-groundwater contamination in a typical industrial park, North China: Importance of multisource auxiliary data. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 911, 168598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, X.W.; Sun, Y.Q.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Qi, J.Y.; Zhang, W.L.; Li, N.; Yin, M.L.; Wang, J.; Lippold, H.; et al. Thallium pollution in China and removal technologies for waters: A review. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.J.; Xiao, J.; Toor, G.S.; Li, Z. Nitrate-nitrogen transport in streamwater and groundwater in a loess covered region: Sources, drivers, and spatiotemporal variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Li, Q.Q.; Liu, D.P.; Hao, Y.; Gao, H.J.; Yu, H.B. Identifying DOM sources of a closed lake basin in arid and semi-arid regions using Bayesian model and grey influence analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 278, 121499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.X.; Zuo, R.; Ni, P.C.; Xue, Z.K.; Xu, D.H.; Wang, J.S.; Zhang, D. Application of a genetic algorithm to groundwater pollution source identification. J. Hydrol. 2020, 589, 125343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Z.Z.; Li, M.; Wu, H.M. Distributions and interactions of dissolved organic matter and heavy metals in shallow groundwater in Guanzhong basin of China. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.L.; Huang, S.H.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zhou, Y.C. The source apportionment of N and P pollution in the surface waters of lowland urban area based on EEM-PARAFAC and PCA-APCS-MLR. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.Z.; Bu, F.Y.; Li, X.D.; Liu, W.X.; Sun, Z.Q.; Shen, J.L.; Ma, F.J.; Gu, Q.B. Unravelling structure evolution of dissolved organic matter during oxidation by persulfate: Insights from aromaticity and fluorescence analysis. Environ. Res. 2024, 259, 119518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Guo, T.T.; Gao, S.L.; Lu, Y.; Meng, Y.L.; Huo, M.X. Evolution of dissolved organic matter during artificial groundwater recharge with effluent from underutilized WWTP and the resulting facilitated transport effect. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ma, R.; Nghiem, A.; Xu, J.; Tang, L.S.; Wei, W.H.; Prommer, H.; Gan, Y.Q. Sources of ammonium enriched in groundwater in the central Yangtze River Basin: Anthropogenic or geogenic? Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.F.; Qi, Y.L.; Zhong, J.; Yi, Y.B.; Nai, H.; He, D.; He, C.; Shi, Q.; Li, S.L. Deciphering dissolved organic matter characteristics and its fate in a glacier-fed desert river—The Tarim river, China. Environ. Res. 2024, 257, 119251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Wang, X.H.; Wan, X.; Jia, S.Q.; Mao, B.Y. Evolution origin analysis and health risk assessment of groundwater environment in a typical mining area: Insights from water-rock interaction and anthropogenic activities. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkari, E.D.; Abu, M.; Zango, M.S. Geochemical evolution and tracing of groundwater salinization using different ionic ratios, multivariate statistical and geochemical modeling approaches in a typical semi-arid basin. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2021, 236, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.P.; Zhang, R.S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, B.; Chen, D.; Kersten, M.; Guo, H.M. Groundwater irrigation induced variations in DOM fluorescence and arsenic mobility. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.J.; Li, P.Y.; Gong, M.Y. Hydrogeochemical characterization of groundwater quality in the Weining Plain, northwest China. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 140, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.T.; Chen, J.J.; He, C.L.; Ren, S.; Liu, G. Multi-method characterization of groundwater nitrate and sulfate contamination by karst mines in southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Andrade, J.A.; Diaz, E.; Vega, D.I.; Hain, E.; Rose, M.R.; Blaney, L. Spatiotemporal analysis of fluorescent dissolved organic matter to identify the impacts of failing sewer infrastructure in urban streams. Water Res. 2023, 229, 119521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sururi, M.R.; Dirgawati, M.; Notodarmojo, S.; Roosmini, D.; Putra, P.S.; Rahman, A.D.; Wiguna, C.C. Chromophoric dissolved organic compounds in urban watershed and conventional water treatment process: Evidence from fluorescence spectroscopy and PARAFAC. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 37248–37262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Feng, S.B.; Qiu, H.S.; Liu, J.Y. Interaction between the hydrochemical environment, dissolved organic matter, and microbial communities in groundwater: A case study of a vegetable cultivation area in Huaibei Plain, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 165166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Yin, Y.G.; Yang, P.J.; Yao, C.; Tian, S.Y.; Lei, P.; Jiang, T.; Wang, D.Y. Using the end-member mixing model to evaluate biogeochemical reactivities of dissolved organic matter (DOM): Autochthonous versus allochthonous origins. Water Res. 2023, 232, 119644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.N.; He, J.T.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, J.C.; Peng, C.; Bi, E.P. Coupling of multi-hydrochemical and statistical methods for identifying apparent background levels of major components and anthropogenic anomalous activities in shallow groundwater of the Liujiang Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Liu, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Yuan, Q.W.; Chen, Q.Z.; Mei, S.L.; Wu, Z.H. Analysis of Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Tunnel Groundwater Based on Multivariate Statistical Technology. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 4867942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; Liu, Z.W.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.C. Exploratory analysis on spatio-seasonal variation patterns of hydro-chemistry in the upper Yangtze River basin. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 126217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14848-2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality. Standards Press of China (SPC): Beijing, China, 2017.

- Xiang, Z.J.; Wu, S.J.; Zhu, L.Z.; Yang, K.; Lin, D.H. Pollution characteristics and source apportionment of heavy metal(loid)s in soil and groundwater of a retired industrial park. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 143, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, B.B.; Yang, Y.; Cai, X.T.; Gong, X.Y.; Xiang, X.; Wu, T.L. Hydrochemical analysis and quality comprehensive assessment of groundwater in the densely populated coastal industrial city. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.A.; Zhou, P.P.; Wang, G.C.; Zhang, B.A.; Shi, Z.M.; Liao, F.; Li, B.; Chen, X.L.; Guo, L.; Dang, X.Y.; et al. Hydrochemical and isotopic interpretation of interactions between surface water and groundwater in Delingha, Northwest China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, B.; Zhu, M.T.; Wang, X.M.; Liu, G.; Deng, Y.E. Multi-isotope identification of key hydrogeochemical processes and pollution pathways of groundwater in abandoned mining areas in Southwest China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 78198–78215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.H.; Zhang, D.D.; Kong, H.; Zhang, G.T.; Shen, F.; Huang, Z.P. Effects of Salinity Accumulation on Physical, Chemical, and Microbial Properties of Soil under Rural Domestic Sewage Irrigation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.W.; Schneidewind, U.; Krause, S.; Jin, M.G.; Liang, X.; Zhan, H.B. Ammonium enrichment, nitrate attenuation and nitrous oxide production along groundwater flow paths: Carbon isotopic and DOM optical evidence. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.X.; He, W.; Li, B.H.; Hur, J.; Guo, H.M.; Li, X.M. Refractory Humic-like Substances: Tracking Environmental Impacts of Anthropogenic Groundwater Recharge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 15778–15788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, M.J.M.; Hooper, J.; Mullins, G.A.; Bell, K.Y. Development of a fluorescence EEM-PARAFAC model for potable water reuse monitoring: Implications for inter-component protein-fulvic- humic interactions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Xi, B.D.; Li, W.T.; Xu, Y.Q.; Zhao, H.Z.; Chen, Z.Q.; He, X.S.; Xing, B.S. Molecular structure and evolution characteristics of dissolved organic matter in groundwater near landfill: Implications of the identification of leachate leakage. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.Y.; Wang, Y.K.; Li, Z.X.; Gao, S.; Zou, H.; Li, L. Traceability of gushing water in the MiddleRoute of the South-to-North Water Diversion (Beijing section) through the river area. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, M.; Roccaro, P.; Korshin, G.V.; Vagliasindi, F.G.A. Monitoring the Behavior of Emerging Contaminants in Wastewater-Impacted Rivers Based on the Use of Fluorescence Excitation Emission Matrixes (EEM). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4306–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, J.P.R.; Carr, A.F.; Nayebare, J.; Diongue, D.M.L.; Pouye, A.; Roffo, R.; Gwengweya, G.; Ward, J.S.T.; Kanoti, J.; Okotto-Okotto, J.; et al. Tryptophan-like and humic-like fluorophores are extracellular in groundwater: Implications as real-time faecal indicators. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 72258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, B.; Liu, J.T.; He, W.; Lü, X.L.; Cao, X.; Chen, X.R.; Zeng, X.J.; Zhang, Y.X. Optical variations of dissolved organic matter due to surface water-groundwater interaction in alpine and arid Datonghe watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.