Abstract

To address the stringent insulation safety requirements of modern high-voltage transformers, accurately characterizing the transient electric field is critical. However, a significant problem remains: current engineering models typically rely on static capacitive distributions, failing to capture the dynamic electric field distortion induced by rapid space charge injection under lightning impulses. Therefore, a non-contact spatial electric field measurement method based on the optical Kerr effect was employed to analyze the influence of electrode material, voltage amplitude, and wavefront time. Unlike traditional simulation models that often assume constant mobility and focus solely on the shielding effect, this study reveals a non-monotonic electric field evolution driven by a ‘Static-Dynamic’ mode transition. The proposed model highlights two critical breakthroughs: (1) Mechanism Innovation: It experimentally verifies that charge injection is governed by the ion charge-to-mass ratio rather than just the work function, leading to a newly identified field enhancement phase during the wavefront that overcomes the limitations of capacitive models that underestimate transient stress. (2) Parameter Quantification: Precise spatiotemporal thresholds are established—negative charges traverse the gap within ~200 ns, while positive charges require ~10 μs to reach equilibrium. These findings provide experimentally calibrated time constants for simulation correction and offer new criteria for optimizing electrode materials in UHV transformers to mitigate transient field distortion.

1. Introduction

With the extensive development of Ultra-High Voltage (UHV) hybrid AC/DC power grids, power transformers, serving as pivotal energy hubs, face increasingly complex operating conditions, thereby imposing stricter requirements on the safety barriers of the power grid [1,2]. Particularly within the transformer, the oil–paper composite insulation system is required not only to maintain exceptionally high dielectric strength but also to ensure the stability of the electric field distribution when subjected to transient overvoltages, such as lightning or switching impulses. If this stability is compromised by space charge accumulation, the resulting non-uniform field distortion can lead to two critical failures: (1) local electric field overshoot exceeding the breakdown strength of the oil gap during the wavefront; (2) persistent high-field stress at the oil–paper interface during the wavetail, inducing interface flashover. this requirement has thus emerged as a critical boundary condition for the insulation research and development of modern large-scale transformers [3]. During the design of transformer insulation, the electric field distribution and insulation characteristics under impulse voltage serve as critical design criteria. Space charge accumulation can induce electric field distortion and compromise the dielectric properties of liquid dielectrics [4]; therefore, it is essential to indirectly analyze space charge distribution by investigating the charge transport process, thereby elucidating its impact on the spatial electric field. However, existing research on charge distribution characteristics in oil–paper insulation systems under impulse voltage predominantly relies on simulation calculations [5,6,7]; these typically analyze the electric field via capacitive field models and determine design values using safety margins based on permissible field strengths [8]. However, existing studies fail to explain the competition between the voltage rise rate and the charge injection rate and typically treat charge distribution as a quasistatic function of voltage amplitude, failing to account for the ‘time window effect’ induced by wavefront steepness. It remains unclear whether a critical time threshold exists under varying impulse degrees of steepness that governs the transition from interface polarization-dominated electric field enhancement to injection-dominated electric field shielding. The lack of clarity on this charge-electric field synergistic response mechanism makes it difficult to accurately predict the insulation safety margin under lightning impulses with distinct wavefront characteristics. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct experimental research on the electric field distribution of typical oil–paper insulation structures subjected to impulse voltage.

Currently, space charge measurement methods have matured significantly, primarily encompassing the Pulsed Electro-Acoustic (PEA) method [9], Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) method [10], Laser-Induced Pressure Pulse (LIPP) method [11], the probe method [12], and the Kerr electro-optic measurement method. The first three techniques are typically employed for measuring space charge within solid polymers; however, due to the rapid variation in space charge in liquid dielectrics under impulse voltage and the inherent amorphous nature of liquids, these methods designed for solid materials are unsuitable for accurately acquiring the electric field and space charge distribution within liquids. The probe method, based on the principle of electrostatic induction, allows for the calculation of space charge by differentiating the measured electric field distribution; however, the insertion of a probe physically perturbs the electric field under investigation, resulting in significant measurement errors. In contrast, measurement techniques based on the Kerr electro-optic effect offer significant advantages, including rapid response speed, high precision, and non-intrusiveness to the electric field. Consequently, this method is widely adopted for measuring electric field and space charge distributions in liquid media.

In the field of Kerr electro-optic diagnostics, early research predominantly focused on equivalent dielectrics possessing extremely high Kerr constants, such as propylene carbonate. Professor Zahn’s team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) pioneered the application of the optical compensation method to capture the carrier evolution dynamics within these highly polar fluids under varying voltage polarities [13], revealing the decisive influence of electrode materials on charge injection characteristics [14]. However, while such equivalent experiments validated the feasibility of optical measurements, the charge transport mechanisms within these media differ fundamentally from those in low-polarity hydrocarbons, such as transformer oil. Addressing the oil–paper insulation structures encountered in practical engineering, domestic researchers have employed AC modulation techniques to deeply analyze the distribution mechanisms of steady-state electric fields. The research team at North China Electric Power University, through dynamic monitoring of interfacial charges under combined AC-DC electric fields, identified that heterocharge accumulation induced by the DC component is the primary cause of asymmetrical distortion in the spatial electric field [15,16]. The study identified charge accumulation at the oil–paper interface as the primary cause of this DC field asymmetry. Building upon Zahn’s research, Professor Yang Qing and colleagues from Chongqing University simulated the injection and transport processes of space charge in liquids, comparing their results with experimental data on spatial electric field and charge distribution in propylene carbonate obtained via a Kerr electro-optic system [17]. Furthermore, extending the research on propylene carbonate, they utilized linear array photodetectors to investigate the characteristics of space charge distribution in transformer oil [18,19], as well as in nano-modified transformer oil [20,21].

A review of the existing literature reveals that while charge behaviors in polar fluids or at oil–paper interfaces under quasi-steady states (AC/DC) have been extensively reported, there remains a lack of systematic experimental evidence regarding the transient synergistic response between rapid carrier injection from electrodes and oil–paper interface polarization under impulse overvoltage conditions with microsecond-scale wavefront times. In particular, the spatiotemporal thresholds governing the transition of charges from surface accumulation to bulk diffusion under impulse excitation remain undefined.

Based on a self-constructed spatial electric field measurement setup for oil–paper insulation under impulse voltage, this study systematically investigates the influence of electrode material, voltage amplitude, wavefront time, and wavetail time on the electric field characteristics within transformer oil. Building upon these findings and incorporating empirical data, a charge transport model for oil–paper insulation systems under impulse voltage is established. This work aims to provide experimental evidence and theoretical references for the optimization of power transformer insulation structures.

2. Measurement Principle and Apparatus for Spatial Electric Field in Oil–Paper Insulation Under Impulse Voltage

2.1. Kerr Effect

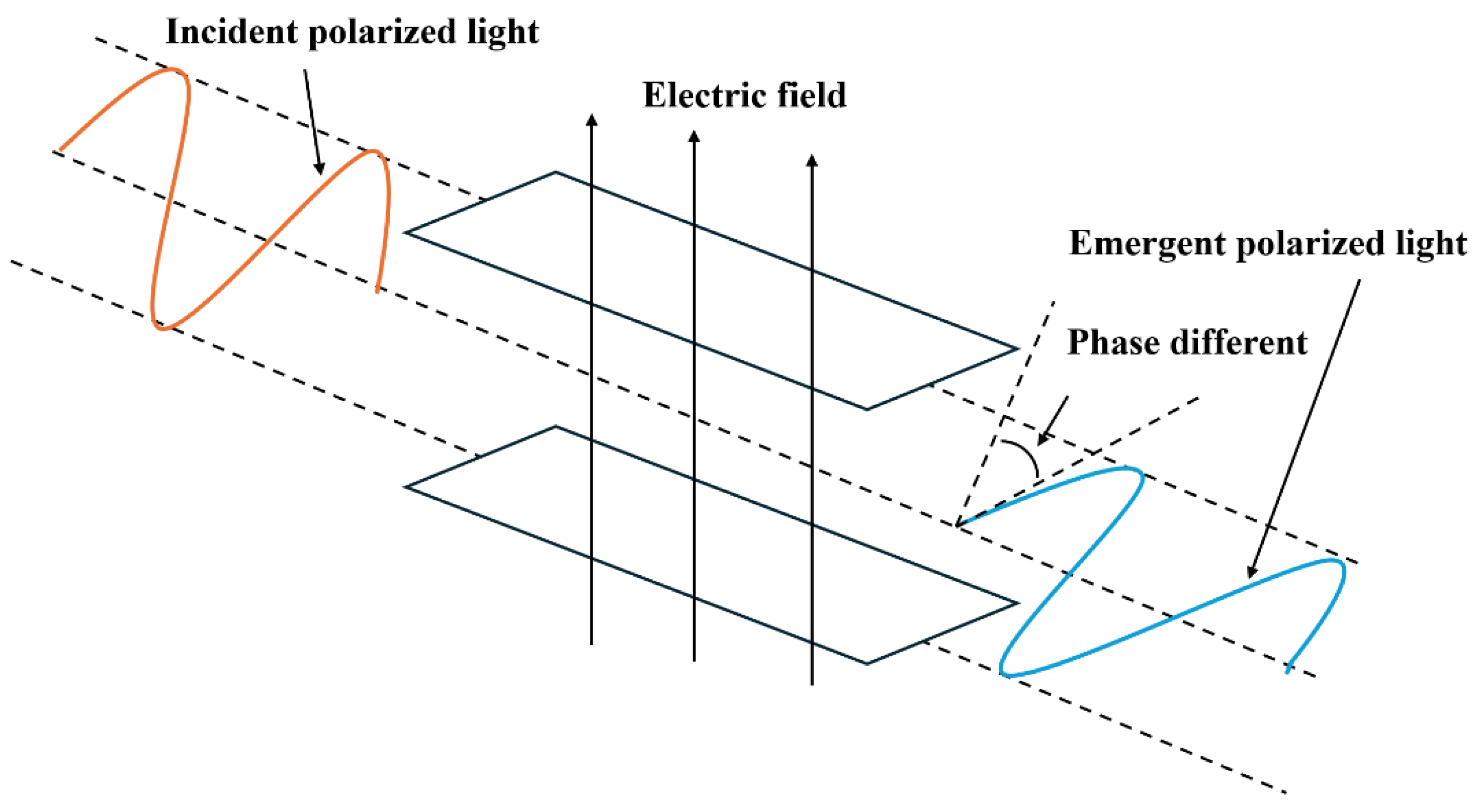

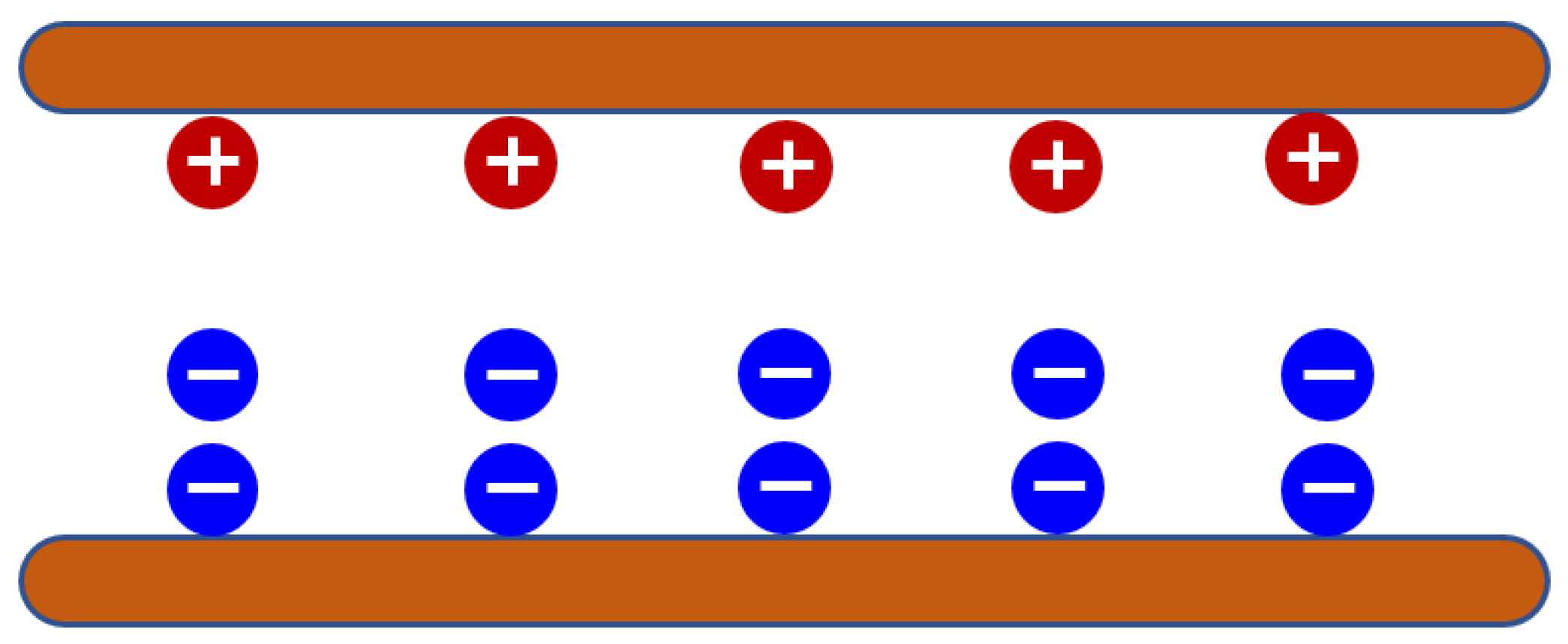

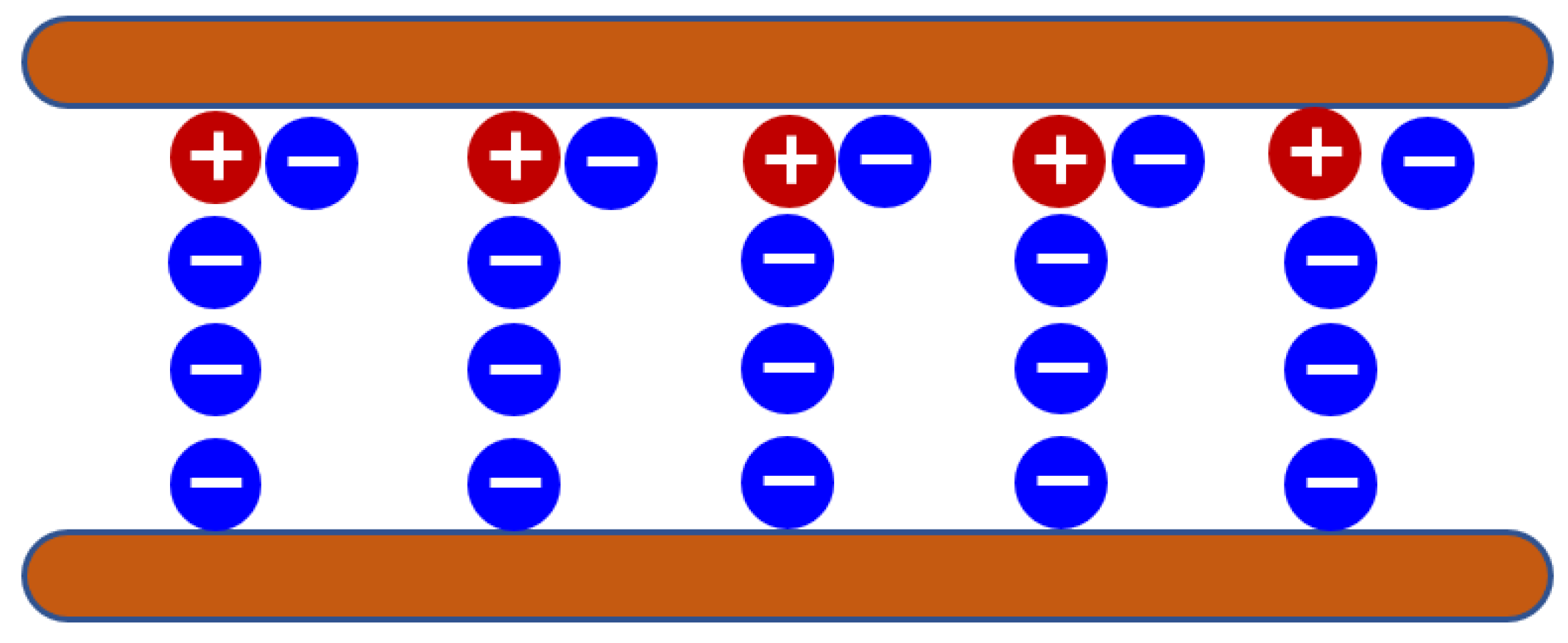

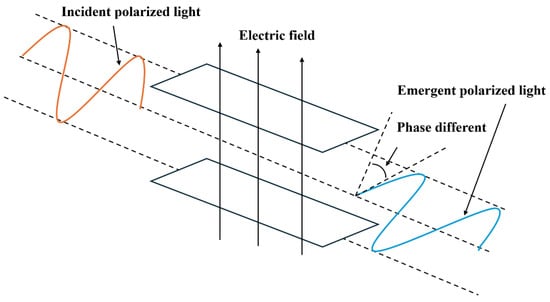

Under the influence of an applied electric field, transformer oil exhibits birefringence, resulting in different refractive indices for light components polarized parallel and perpendicular to the electric field direction. This induces a phase difference between the two components that is proportional to the square of the applied electric field magnitude E, a phenomenon known as the Kerr effect. The optical path diagram is illustrated in Figure 1. By utilizing Jones calculus for vector transformation to derive the relative light intensity, the relationship between the output light intensity and the input light intensity is obtained, as presented in Equation (1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Kerr Effect Optical Path.

In Equation (1), Ii denotes the input light intensity, and Io represents the output light intensity. Em signifies the electric field strength at which the light intensity reaches its first maximum, also referred to as the half-wave field strength; this value depends solely on the Kerr constant and the effective length of the electric field region, as calculated by Equation (2).

where B represents the Kerr constant of the dielectric liquid, and L denotes the effective length of the optical path through the electric field. Em serves as a reference value when the output light intensity varies with the increasing electric field. The light intensity achieves its maximum values when the electric field magnitude reaches √1, √3, √5……√n times Em, where n is an odd integer. For non-extreme points, the electric field strength is inversely calculated from the light intensity as follows: when the light intensity increases from a minimum to a maximum, the relationship is described by Equation (3); conversely, when the light intensity decreases from a maximum to a minimum, the relationship follows Equation (4).

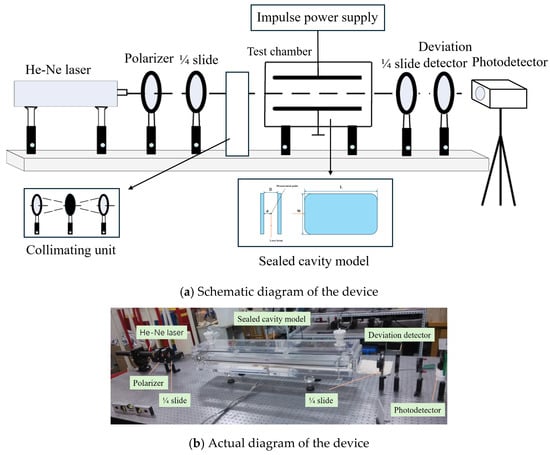

2.2. Measurement Platform

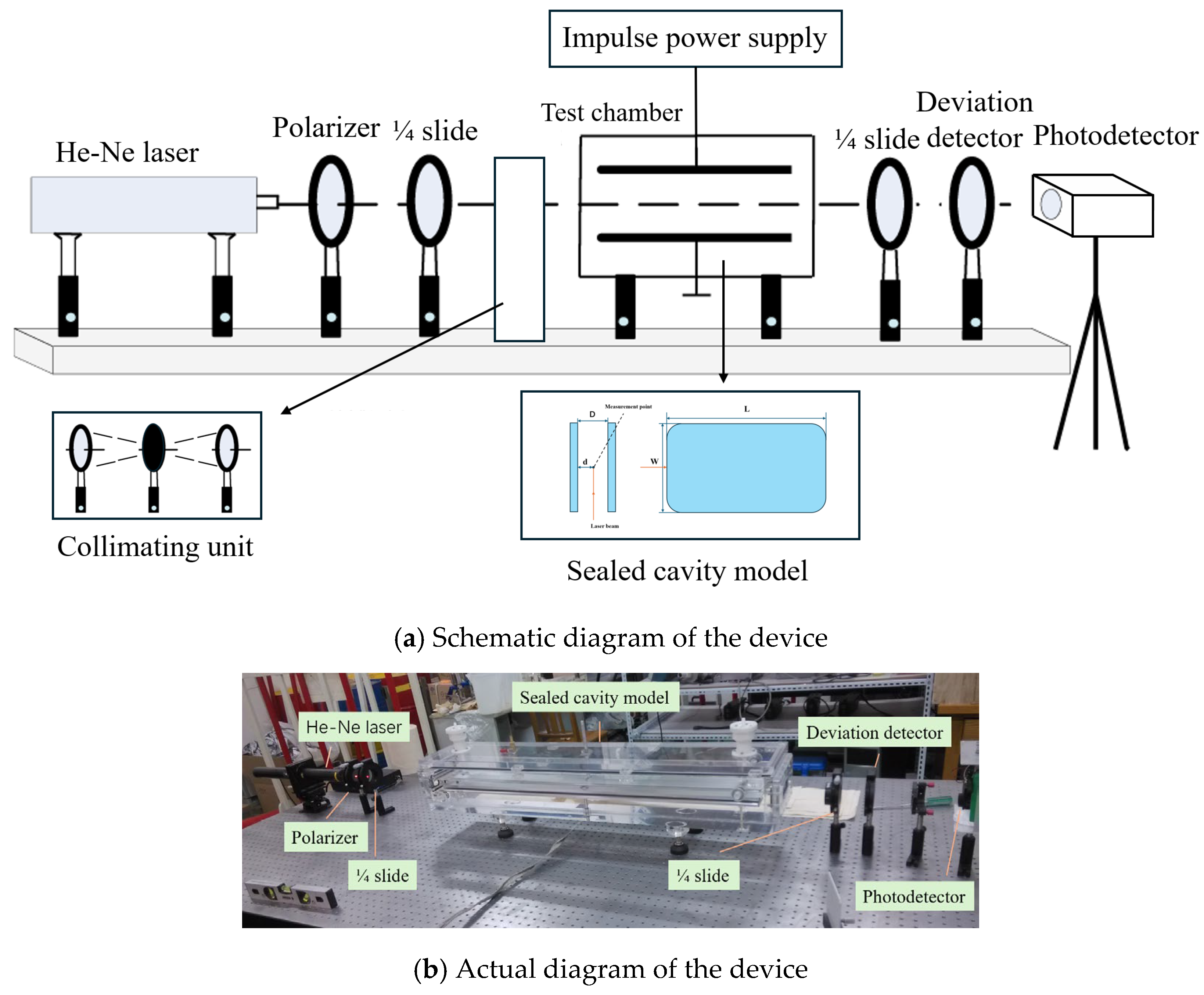

The rapid measurement system for impulse electric fields is illustrated in Figure 2, comprising an optical system, a photoelectric conversion device, and a sealed chamber. The core component of the experimental setup consists of a highly sealed oil chamber equipped with precision-machined parallel plate electrodes. To ensure the uniformity of the electric field distribution and suppress localized tip discharges, the electrodes are fabricated from brass, stainless steel, or aluminum alloy with a length of 1 m and a width of 80 mm, featuring rounded edges. To ensure electric field uniformity within the Kerr effect observation region and mitigate measurement errors induced by local field distortions from surface defects, the electrode surface roughness was strictly controlled to 1.6 μm in accordance with established standards [22].

Figure 2.

Schematic of the High-speed Impulse Electric Field Measurement Setup.

There is a dried insulating fiber paper layer between the parallel plates. To eliminate the interference of moisture on interface polarization, strict quality control measures were implemented: (1) The pressboard was vacuum-dried at 85 °C for 48 h [23]; (2) the dried paper was impregnated with degassed transformer oil under vacuum conditions for 48 h; (3) the sample transfer and electrode assembly were completed within 5 min in a humidity-controlled environment to minimize moisture reabsorption before sealing the test chamber. The measurement point is positioned at the central axis of the electrodes, where the gap spacing is precisely adjustable within a range of 0 to 10 mm via an adjustable mechanism [2].

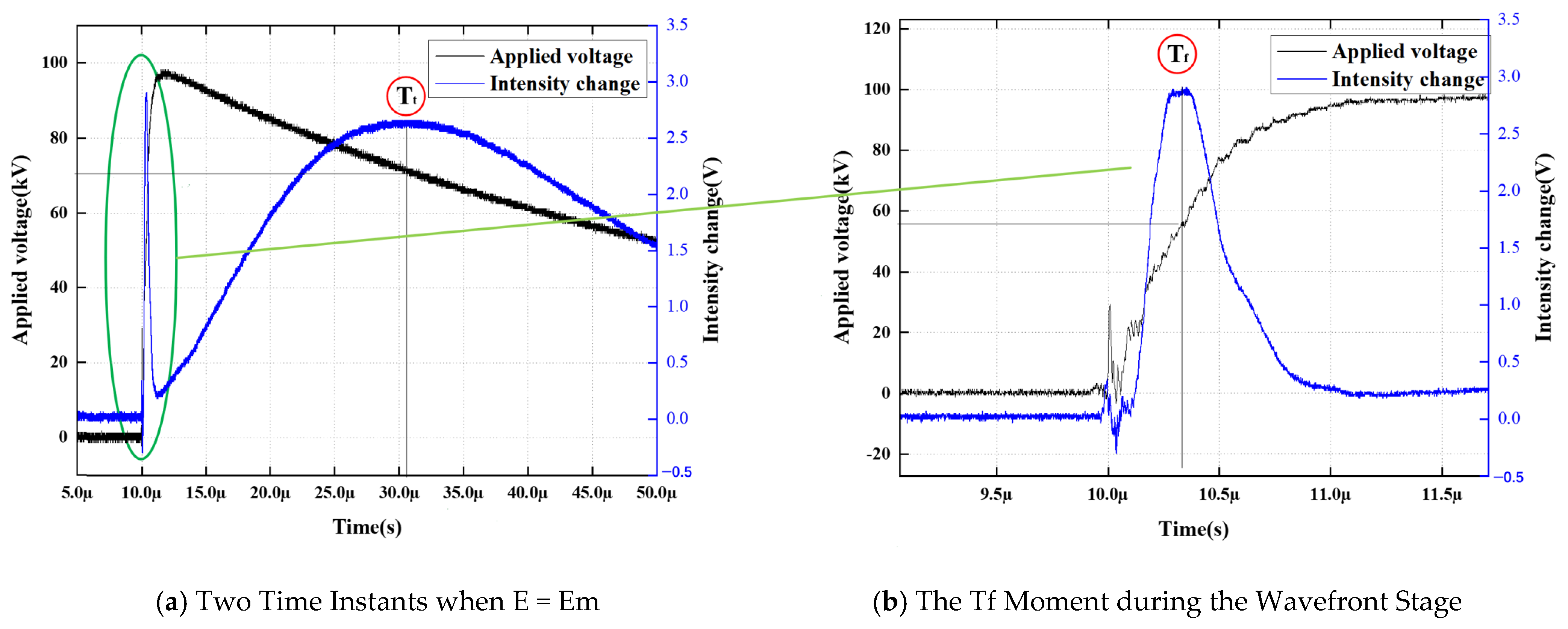

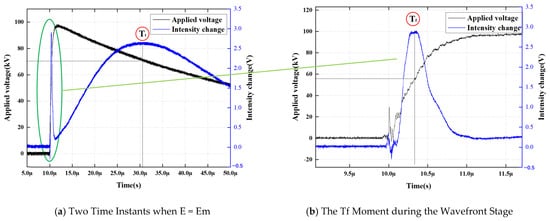

2.3. Experimental Methods

As indicated by Equation (2), the half-wave field strength Em depends exclusively on the Kerr constant and the length of the electric field region traversed by the laser. In the experimental setup employed in this study, the liquid dielectric is No. 25 transformer oil, characterized by a Kerr constant B = 3 × 10−15 m/V2 and an electrode length L = 1 m. According to the theory of electro-optic modulation, the critical electric field strength corresponding to the first complete phase reversal of the system (i.e., where the light intensity reaches its first maximum) is calibrated as Em = 12.9 kV/mm this value serves as the benchmark reference for the subsequent back-calculation of charge injection intensity. The light intensity achieves its maximum values when the magnitude of the composite electric field E successively reaches √1Em, √3Em, √5Em, ……, √nEm, where n is an odd integer. The composite electric field E is the superposition of the applied electric field E1 and the electric field E2 induced by space charges within the oil–paper insulation system, where E2 comprises contributions from positive charges (E2+) and negative charges (E2−). Consequently, the instants at which light intensity maxima occur correspond to the condition where E = Em. To record these transient variations, the modulated laser beam is captured by a linear photodetector, converting optical signals into electrical waveforms. This output is connected to Channel 1 of a digital storage oscilloscope, while the applied impulse voltage, measured via a capacitive divider, is connected to Channel 2. The two signals are synchronously triggered and digitized to ensure strict temporal alignment. Subsequently, the recorded optical intensity data is converted into electric field strength E(t) using the inversion calculation described in Equations (3) and (4). This study focuses on monitoring two critical dynamic time points: the Wavefront Response Peak and the Wavetail Recovery Peak, at which the composite electric field E equals Em. For quantitative characterization, the instant when the electric field strength first reaches the calibrated value Em during the wavefront phase (the wavefront response peak) is defined as the “Tf moment”; correspondingly, the instant when the electric field intersects Em again during the wavetail decay phase (the wavetail recovery peak) is defined as the “Tt moment”. Through time-alignment techniques, the actual applied voltage component E1 corresponding to these characteristic moments is extracted. In the context of oil–paper interface polarization, if the measured voltage E1 is lower than the calibrated field strength Em, it indicates a positive superposition effect of space charge on the macroscopic electric field (field enhancement); conversely, if E1 is higher, it suggests that the accumulation of homocharges induces a shielding attenuation effect. The results are illustrated in Figure 3. Unlike experiments conducted with pure oil gaps, this study introduces a dried insulating fiber paper layer between the parallel plates. This configuration necessitates that charges undergo an interface trapping process before migrating to the center of the oil gap, thereby altering the lag time associated with the appearance of characteristic peaks. Throughout the experimental process, the analysis focuses on the non-linear coupling mechanism between the applied electric field E1, generated by the impulse waveform, and the induced field E2, resulting from charge accumulation at the oil–paper interface.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Moment when the Resultant Field Equals Em (The lines indicate that (b) is a magnified view of the circled area in (a)).

3. Space Charge Characteristics in Transformer Oil Under Impulse Voltage

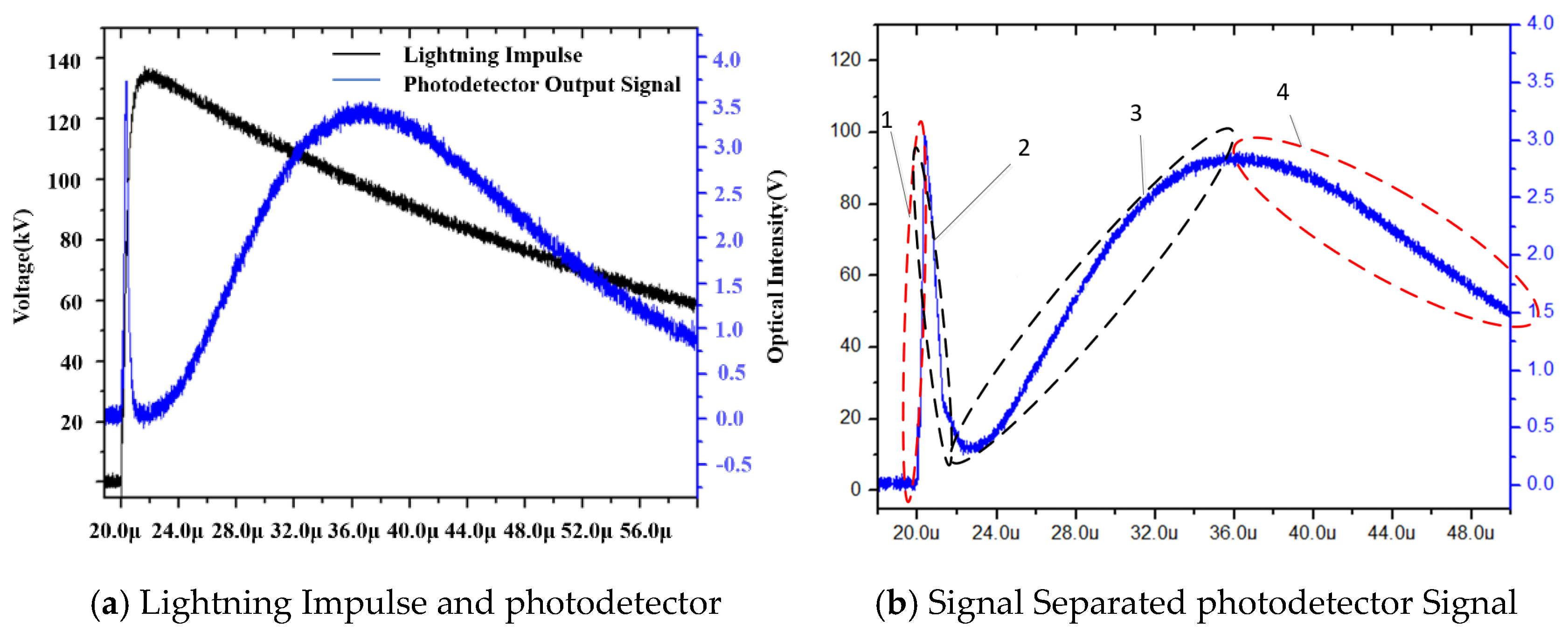

3.1. Electric Field Characteristics Within the Oil Gap Under Impulse Voltage

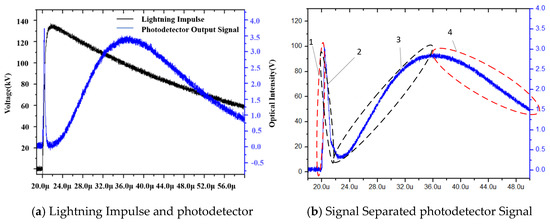

To extract transient electric field characteristics from the modulated photodetector output, time-domain demodulation was performed on the photoelectric response curve based on the calibrated half-wave field strength Em (12.9 kV/mm). According to the periodic variation in the Kerr signal under impulse excitation, the evolution of the electric field intensity can be categorized into four distinct physical stages based on the phase reversal nodes of the light intensity, as illustrated in Figure 4: Stage I (Initial Polarization phase): The electric field ratio E/Em increases from zero to the first modulation limit point; Stage II (Over-modulation Transition phase): As the excitation intensifies, the light intensity signal passes the first peak and recedes, while the corresponding electric field strength further approaches its peak value; Stage III (Inversion Recovery phase): During the wavetail decay stage, the electric field strength decreases from the peak, and the light intensity signal reaches the extreme point once again; Stage IV (Residual Decay phase): The electric field intensity finally falls below the unit ratio (E/Em < 1) and decays toward zero. Based on the identification of these physical stages, the spatial distribution of the electric field within the oil gap was reconstructed using an inversion algorithm, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the photoelectric Signal Principle (different stages are indicated by Arabic numerals, distinct colors, and dashed lines).

Figure 5.

Waveform of the Back-calculated Electric Field.

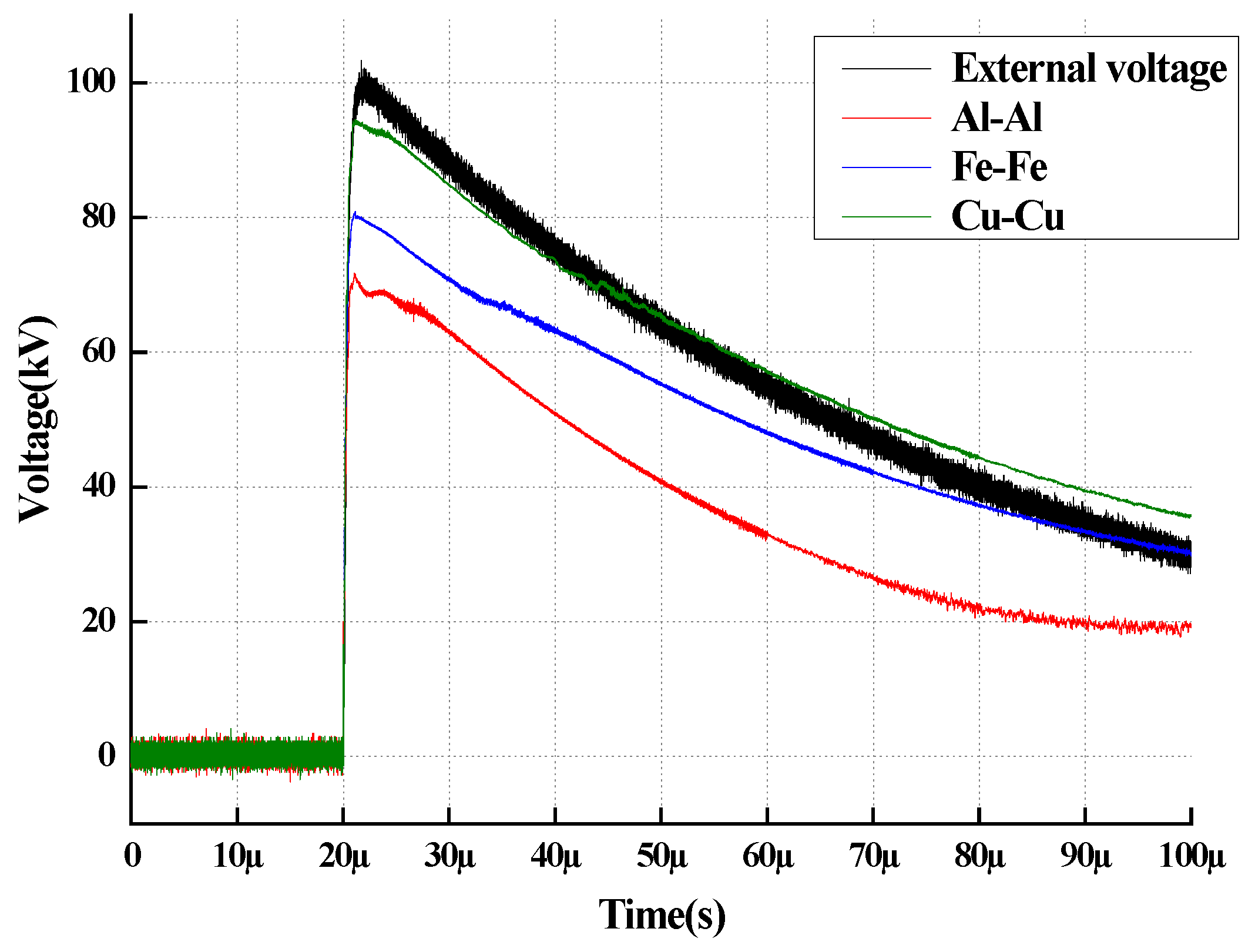

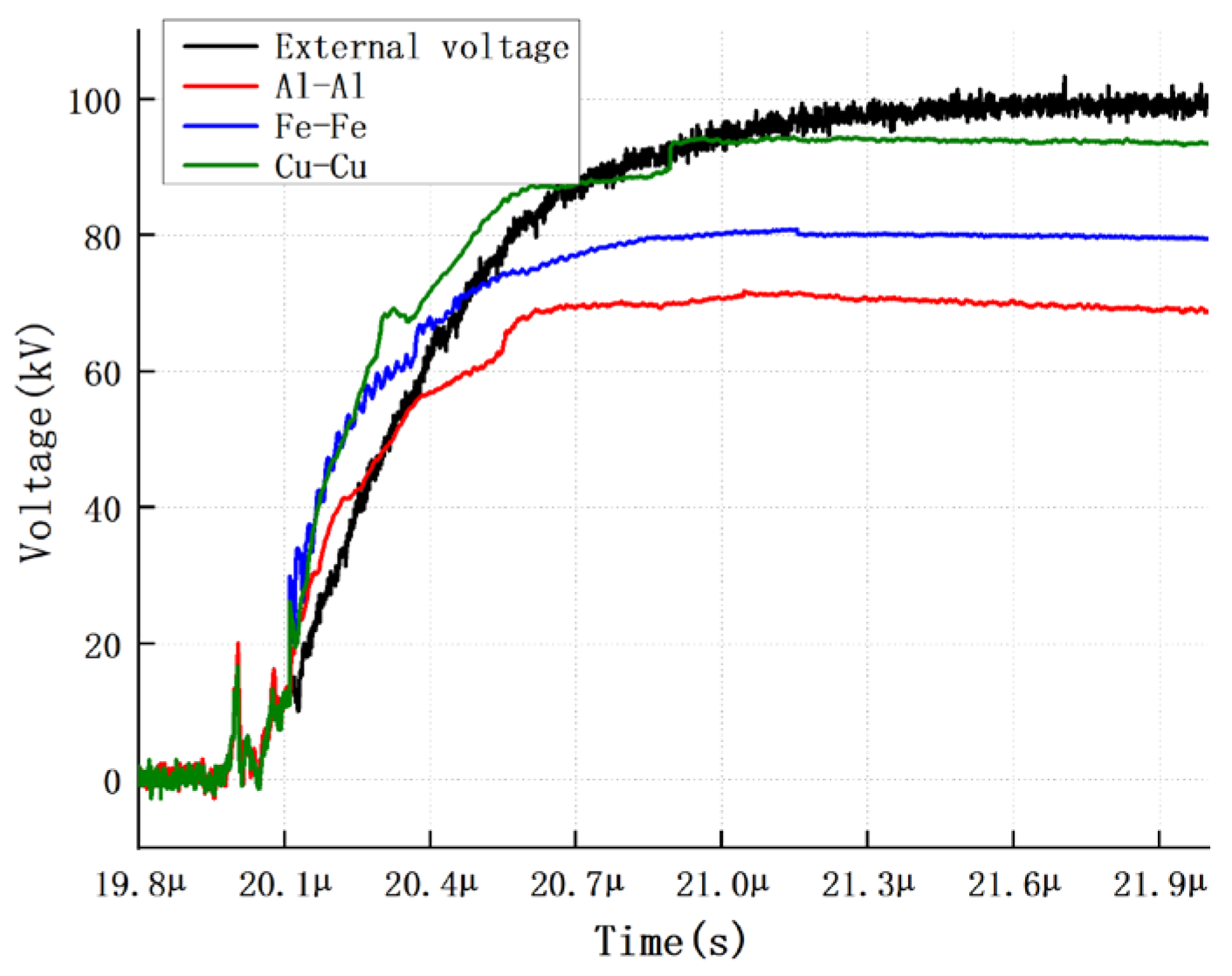

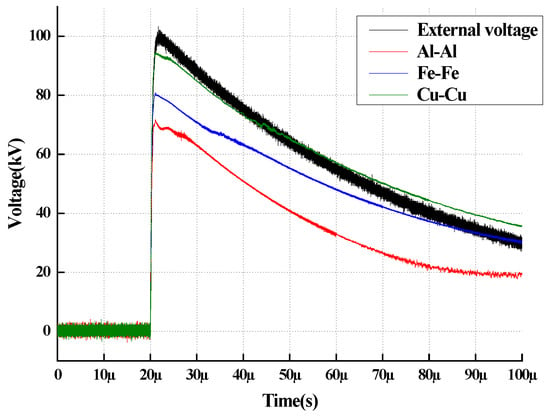

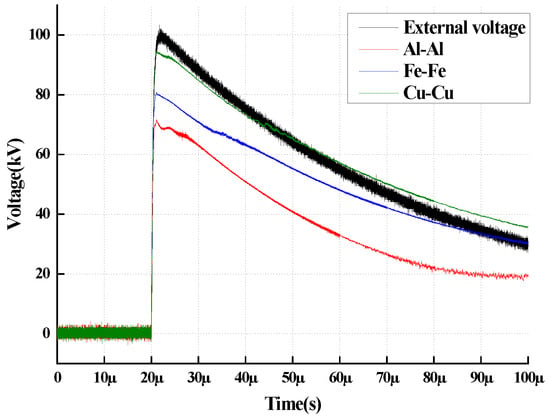

3.1.1. Comparative Analysis of Electric Field Characteristics Within the Oil Gap Under Identical Voltage for Different Metal Electrode Combinations

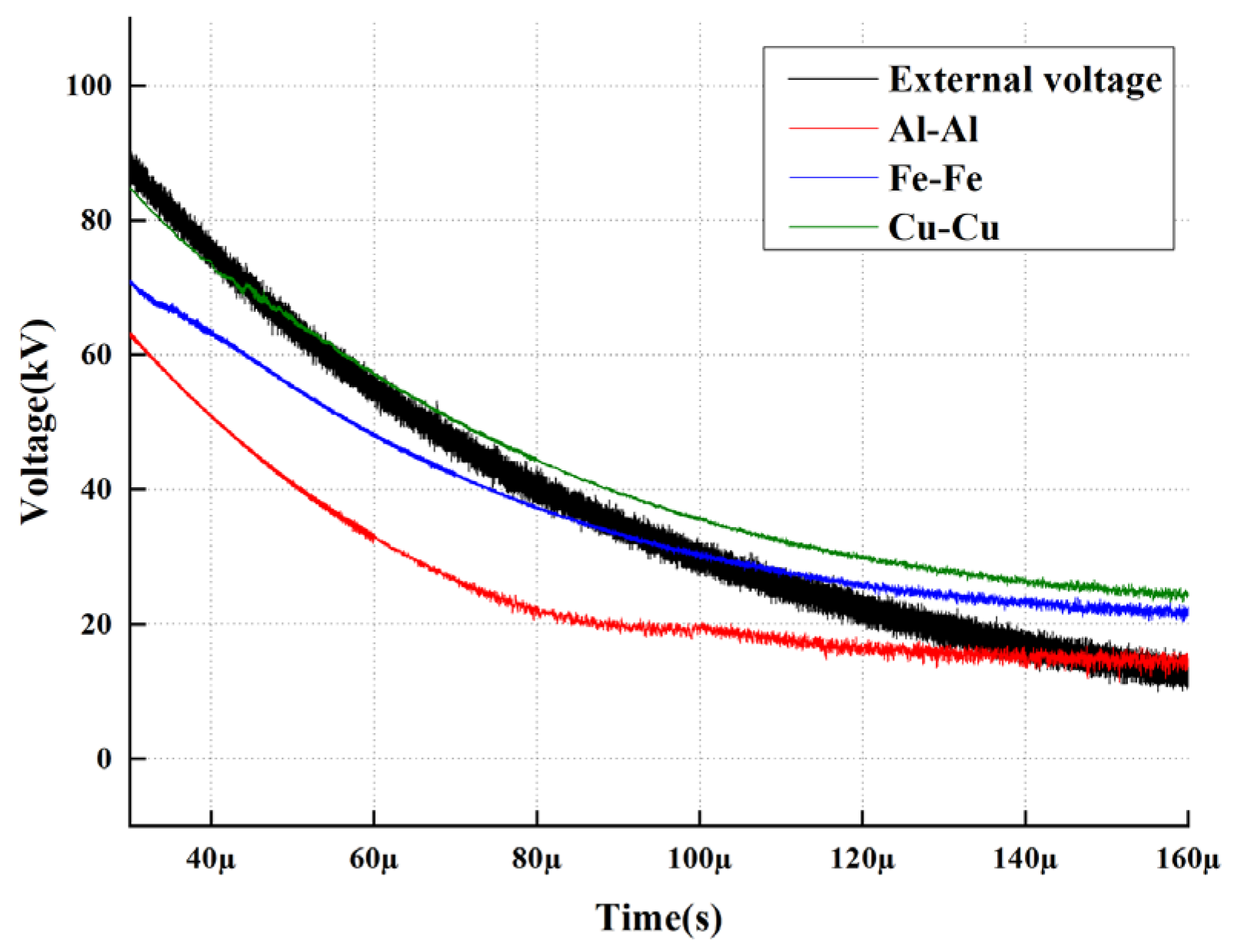

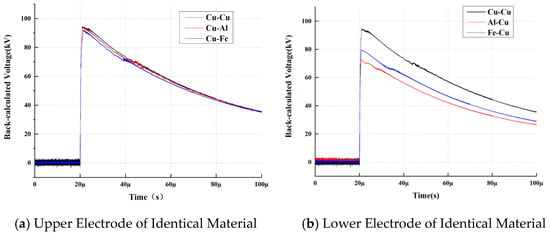

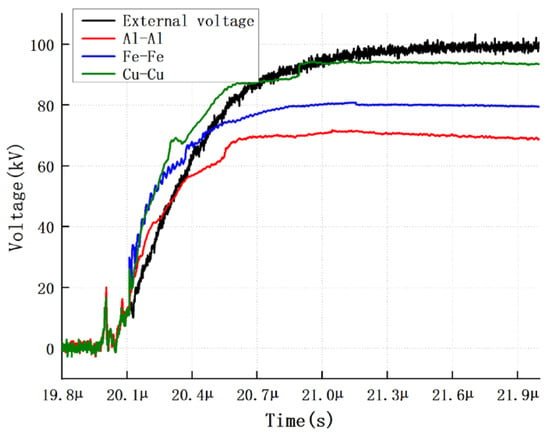

The electrode configurations employed consist of Brass–Brass, Aluminum–Aluminum, and Stainless Steel–Stainless Steel pairs, where both the upper and lower electrodes are of identical material. For the sake of brevity, these combinations are denoted herein by the symbols of their primary constituent elements: Cu-Cu, Al-Al, and Fe-Fe, respectively. To evaluate the impact of electrode materials on electric field distortion, we selected the Laplacian electric field, represented by the applied voltage waveform (black line) measured by a standard voltage divider, as the theoretical benchmark. The electrode gap was adjusted to 5 mm, and impulse tests were conducted on the three electrode groups by applying an impulse voltage with a peak of 100 kV and a waveform of 2/25 μs. The resulting back-calculated electric field distributions are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Back-calculated Electric Field for Identical Metal Electrode Pairs (Conditions: 100 kV Peak, 2/25 μs Impulse, 5 mm Gap).

As illustrated in Figure 6, the black curve represents the theoretical applied voltage, while the colored curves represent the back-calculated voltage affected by space charge.

Visual Characteristic 1 (Deviation): Starting from t ≈ 20 μs, all measured curves begin to deviate downwards from the applied voltage trajectory, indicating the onset of the shielding effect. Visual Characteristic 2 (Divergence): The red curve (Al-Al) exhibits the steepest descent, detaching from the reference voltage earliest and reaching the lowest peak value (~70 kV), which corresponds to the strongest field distortion. Visual Characteristic 3 (Stability): In contrast, the green curve (Cu-Cu) closely tracks the black reference line throughout the wavefront, confirming its high fidelity in maintaining the electric field distribution.

Comparative analysis reveals that the physical properties of electrode materials exert a significant modulation effect on the electric field strength within the oil gap. During the impulse process, the aluminum electrode induces the most substantial charge injection, resulting in the strongest electric field shielding effect at the central position and the most severe deviation of the back-calculated electric field from the applied voltage waveform. In contrast, the copper electrode exhibits a superior capability to maintain the fidelity of the original electric field, with its measurement results aligning most closely with the theoretical distribution derived from capacitive voltage division. In summary, the degree to which different metal materials contribute to electric field distortion within the fluid dielectric follows the descending order of Al > Fe > Cu; this is primarily attributed to the higher migration dynamic response of aluminum ions under strong electric fields.

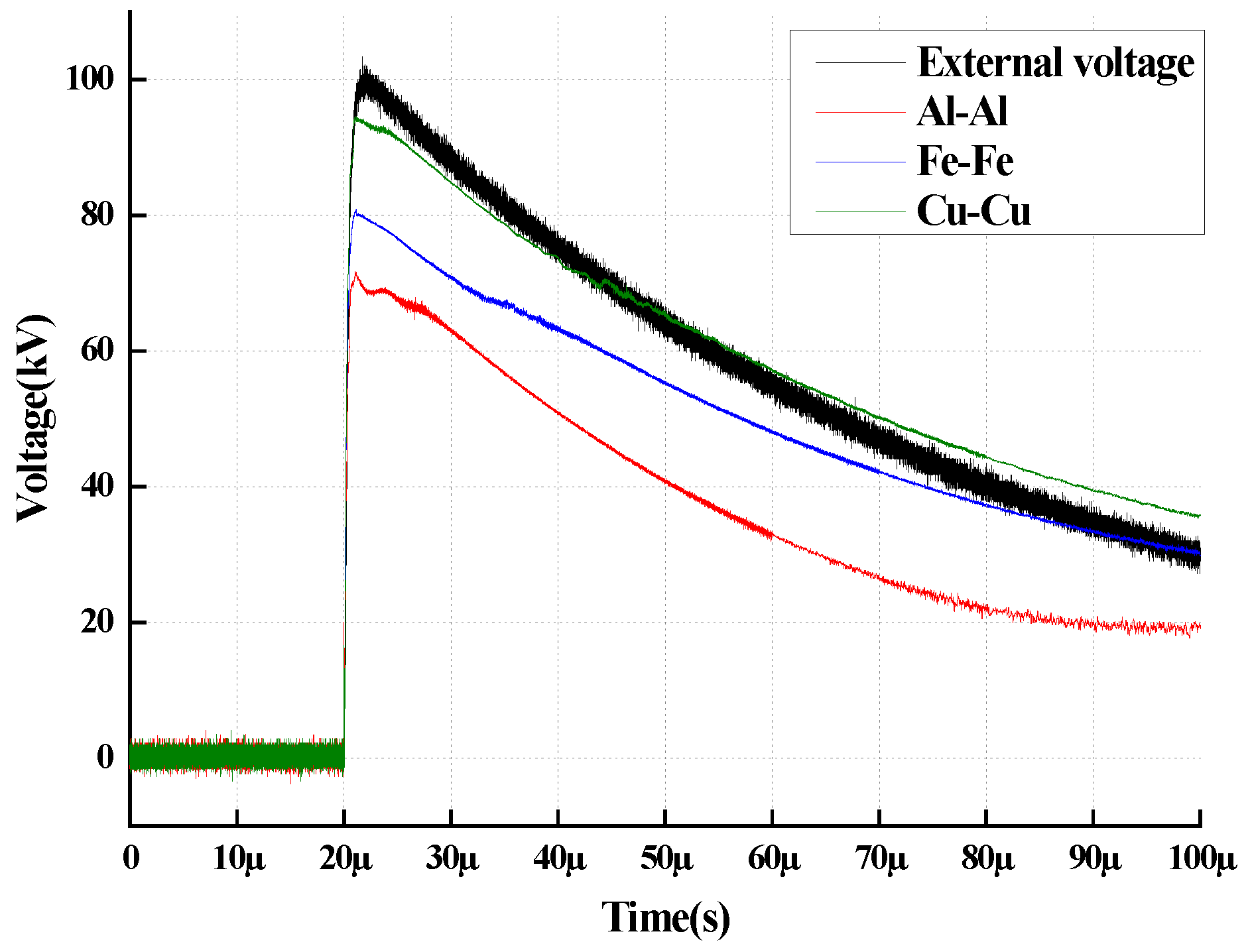

To further investigate the influence of charge on the electric field within the transformer oil, cross-combination electrode tests were conducted under identical experimental conditions. Specifically, these included the Cu-X series (featuring a fixed upper Copper electrode with varying lower electrodes: Cu, Fe, or Al) and the X-Cu series (featuring a fixed lower Copper electrode with varying upper electrodes: Cu, Fe, or Al).

As illustrated in Figure 7, to isolate the spatial contribution of space charge injection sources, this study implemented a sequence of asymmetric electrode configurations. An analysis of the cross-comparison results between the Cu-X and X-Cu groups reveals that the electric field evolution mode of the oil–paper system exhibits distinct unilateral interface dominance. When the material of the high-voltage injection electrode is fixed, variations in the ground-side material exert an influence on the electric field strength at the center of the oil gap that remains essentially within the range of measurement error; conversely, once the material of the high-voltage electrode is altered, the degree of electric field distortion undergoes a reshaping that spans orders of magnitude. This result confirms that under microsecond-scale impulse pulses, the critical factor determining the polarity of electric field distortion is predominantly governed by the ion emission intensity at the high-voltage injection interface.

Figure 7.

Back-calculated Electric Field for Crossed Metal Electrode Combinations (Conditions: 100 kV Peak, 2/25 μs Impulse, 5 mm Gap).

3.1.2. Comparative Analysis of Electric Field Characteristics Within the Oil Gap Under Varying Voltage Amplitudes for Identical Metal Electrode Combinations

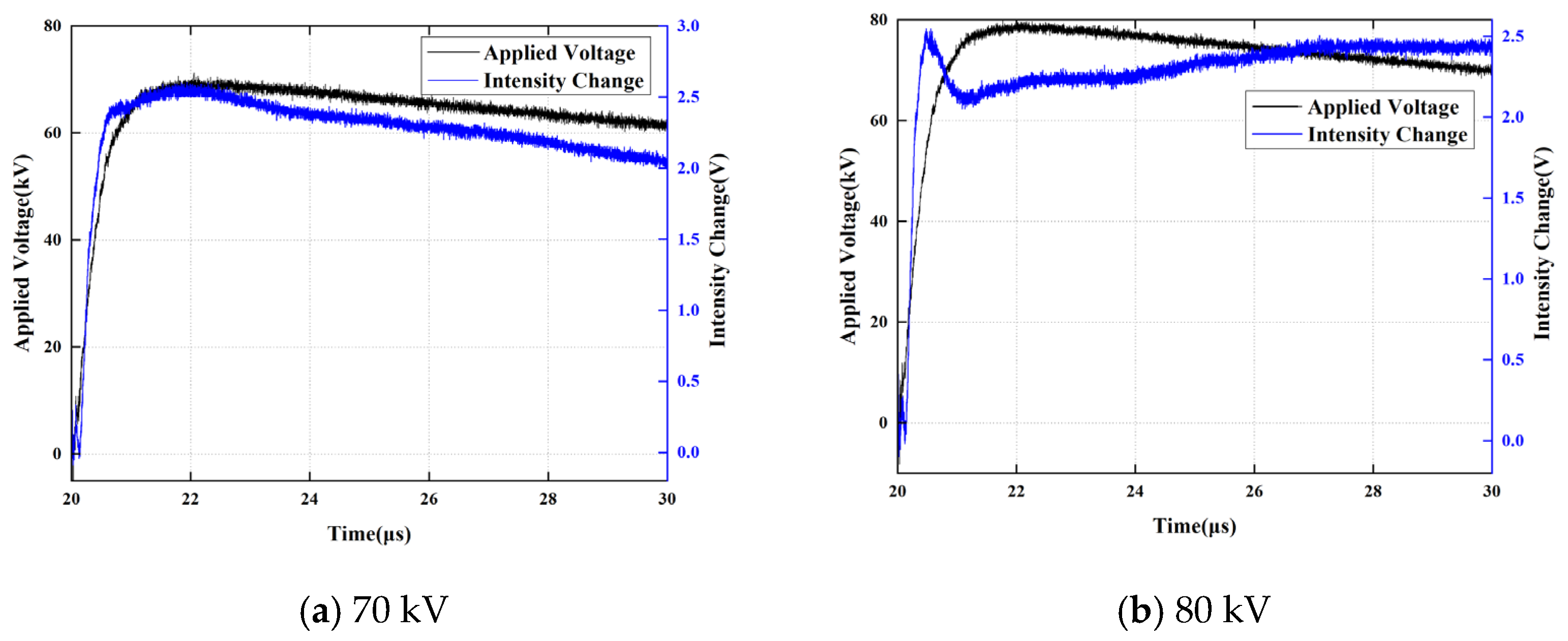

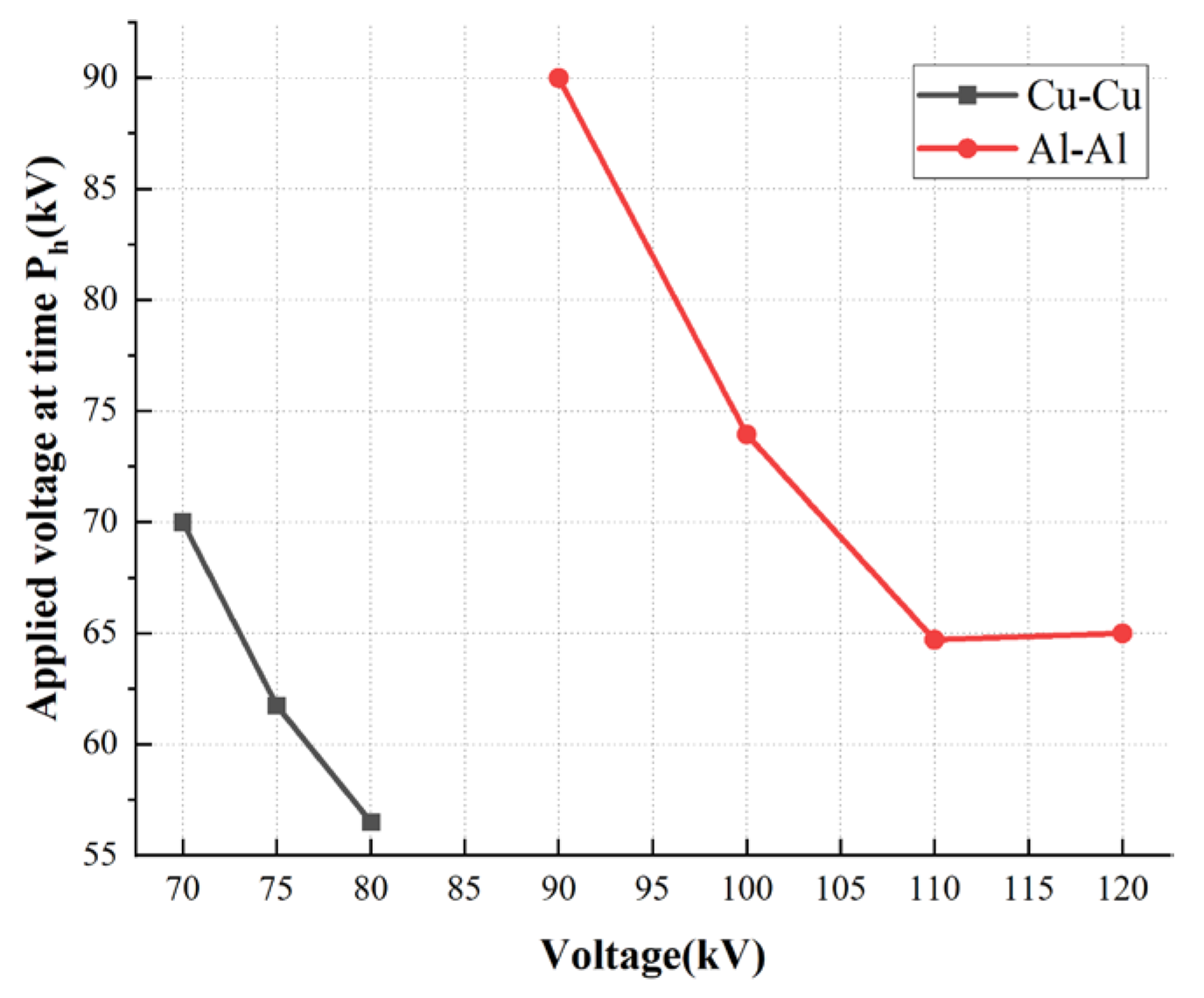

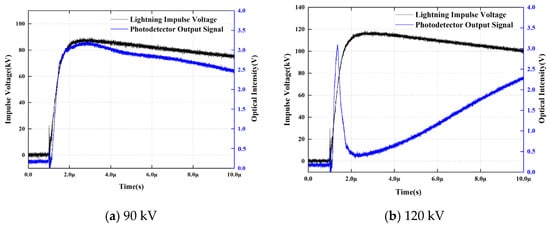

The preceding analysis indicates that the back-calculated electric field is minimized when the upper electrode is Aluminum, whereas it is maximized when the upper electrode is Copper. Consequently, the following section presents a comparative analysis of the applied voltages corresponding to the condition where the composite electric field E within the oil gap equals Em (specifically at the “Tf moment”) under a 2/25 μs impulse voltage, focusing on the Al-Al and Cu-Cu electrode configurations.

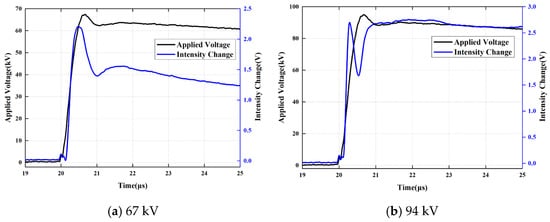

As illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9, with the progressive increase in the applied voltage amplitude, the modulation pattern of space charge on the original electric field undergoes a modal transition from enhancement via potential superposition to shielding via interfacial charges. Under extremely high voltage excitation, the homocharge carriers accumulated at the Tf moment significantly attenuate the equivalent electric field strength at the center of the oil gap, rendering the back-calculated value substantially lower than the nominal level derived from capacitive voltage division. This trend is particularly pronounced in the Al-Al electrode configuration, corroborating the dramatic amplification effect of interfacial injection flux within high-field environments.

Figure 8.

Photoelectric Signals at Various Voltages for Al-Al Electrodes.

Figure 9.

Photoelectric Signals at Various Voltages for Cu-Cu Electrodes.

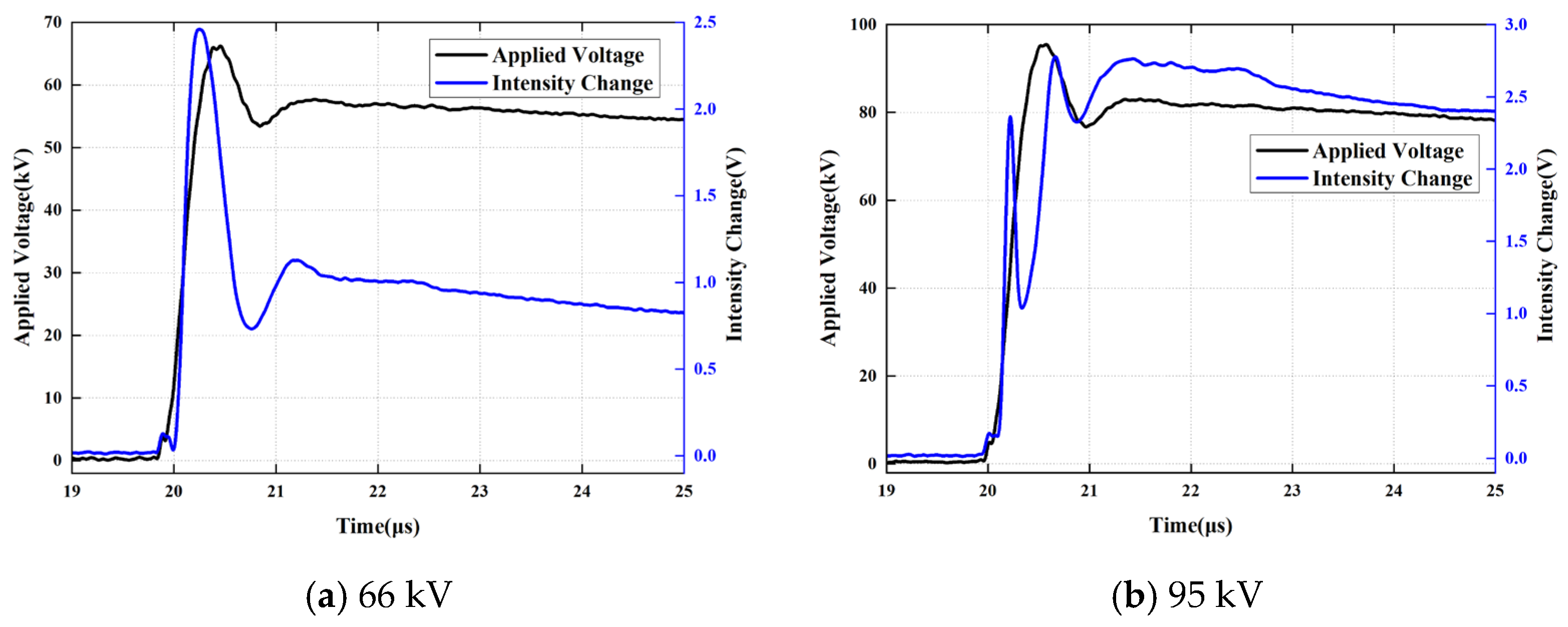

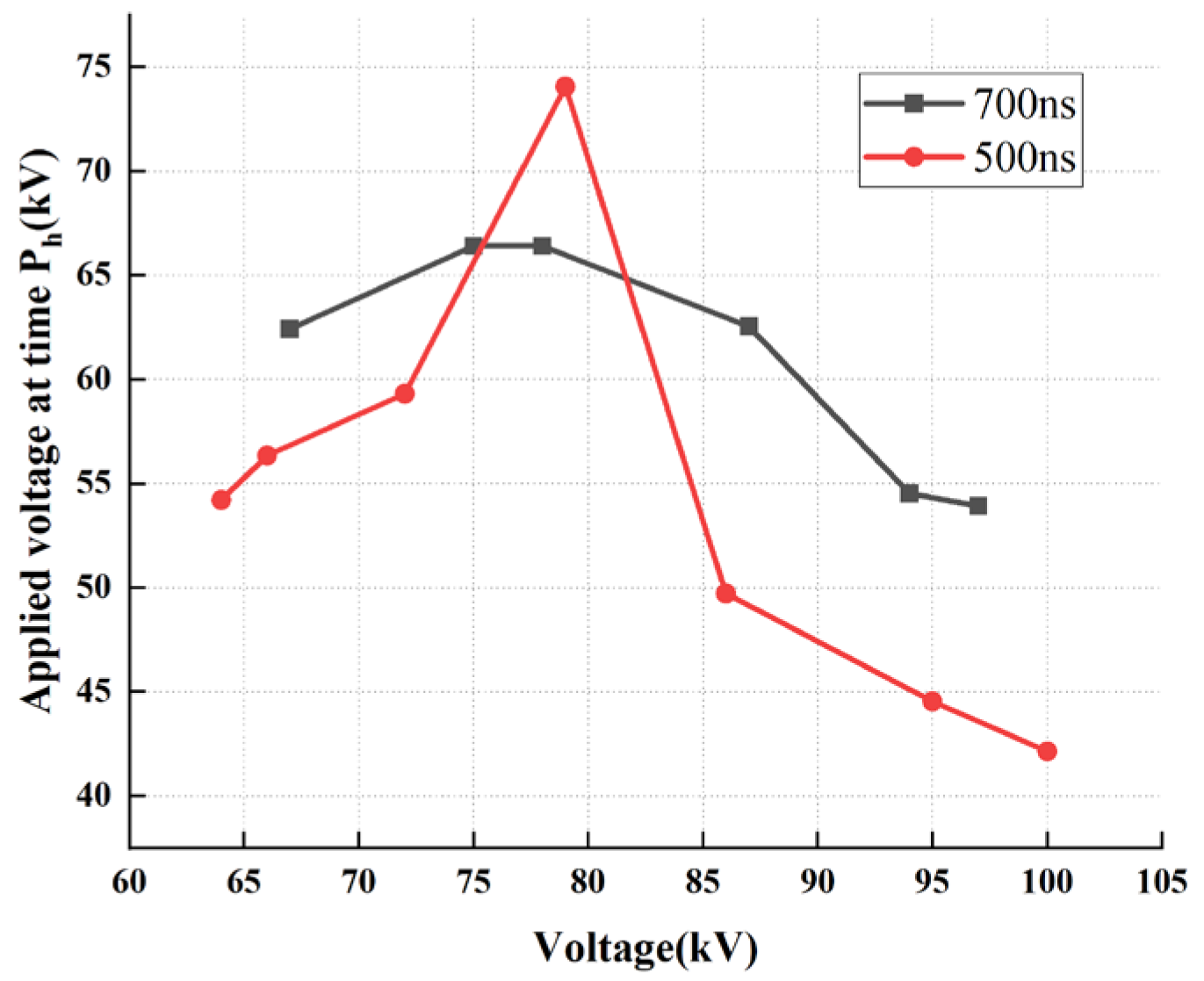

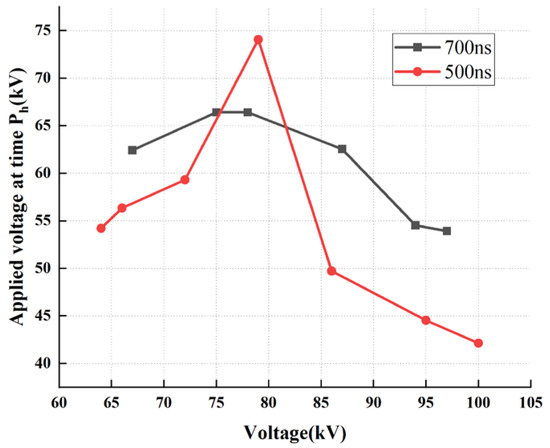

Distinct from the behavior observed under the 2/25 μs impulse voltage, the scenarios involving 0.5/25 μs and 0.7/25 μs impulses exhibit a different trend: as the peak applied voltage increases, the amplitude of the applied voltage at the “Tf moment” initially increases and subsequently decreases, as illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Photoelectric Signals at Different Amplitudes under the 0.5/25 μs Impulse.

Figure 11.

Photoelectric Signals at Different Amplitudes under the 0.7/25 μs Impulse.

Experimental observations reveal that the measured voltage U, corresponding to characteristic moments, exhibits significant non-monotonic evolutionary characteristics in response to the excitation amplitude. Under conditions characterized by high wavefront steepness (e.g., 0.5/25 μs), as the excitation peak increases, the trajectory of $U$ exhibits a distinct peak extremum rather than a linear monotonic response. This phenomenon reflects a kinetic mismatch between the establishment rate of the polarization current and the rate of electric field rise (dV/dt): in the low-amplitude stage, charge migration remains capable of locally tracking the variations in the electric field; however, once the excitation field strength surpasses a critical threshold, the explosive injection of interfacial charges rapidly forms a shielding cloud, which subsequently dominates the attenuation process of the electric field.

3.2. Dynamic Characteristics of Space Charge in Transformer Oil Under Impulse Voltage

Experimental observations indicate that the resultant electric field strength within the oil gap does not linearly track the applied voltage waveform; instead, it exhibits complex dynamic deviation characteristics. Throughout the entire impulse duration, the back-calculated electric field, relative to the theoretical applied field, manifests a sequence of distinct behaviors: an initial “field enhancement effect,” a subsequent “shielding attenuation effect” induced by charge injection, and a final “secondary enhancement effect” triggered by residual charges during the wavetail. This phenomenon of non-monotonic electric field modulation confirms that the transport dynamics of space charge exhibit significant chronological heterogeneity within extremely short time scales. Analyzing the discrepancy between the back-calculated electric field and the applied quasi-static electric field reveals that the system enters a “field overshoot interval” during both the wavefront rise and wavetail decay phases; specifically, the resultant electric field strength exceeds the nominal applied field strength within these specific temporal windows. This observation challenges the traditional assumption that space charge acts solely to shield the electric field, thereby unveiling the enhancement mechanism imposed by polarization charges on the original field distribution during the initial and final stages of impulse excitation.

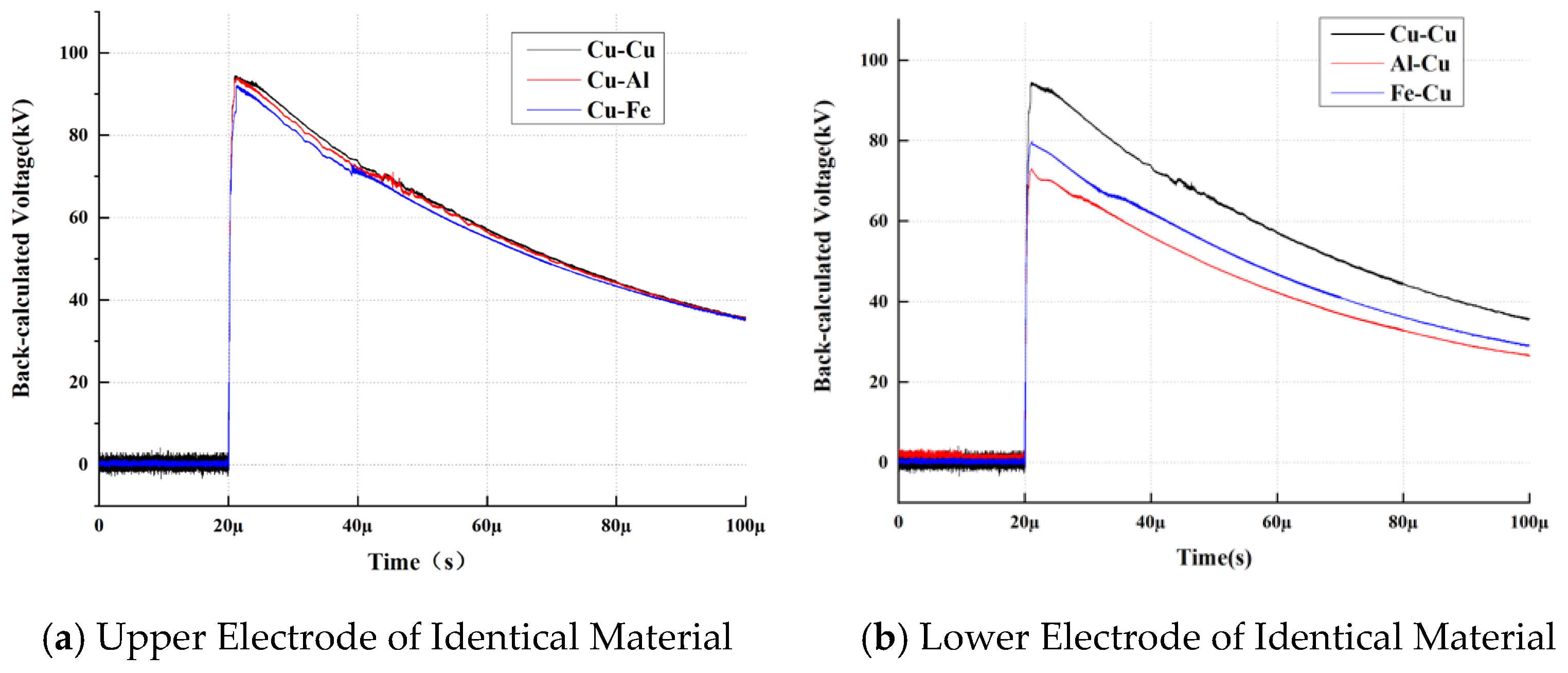

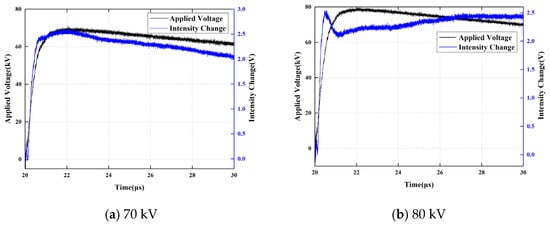

3.2.1. Analysis of Back-Calculated Voltage During the Wavefront Phase for Different Metal Electrode Combinations

With the electrode gap adjusted to 5 mm, impulse tests were conducted by applying a 2/25 μs impulse voltage with a peak amplitude of 100 kV. This section analyzes the relationship between the back-calculated electric field and the applied electric field specifically during the wavefront phase.

As indicated by the data in Figure 12, the experimental waveforms reveal distinct time-domain differences among various materials during the initial phase polarization establishment. The Al-Al electrode exhibits an exceptionally rapid injection response; the “overshoot” duration, during which the resultant electric field exceeds the applied field, lasts only approximately 300 ns before rapidly transitioning into a steady-state regime dominated by charge shielding. In contrast, this transition period is significantly prolonged for the Fe-Fe and Cu-Cu configurations, extending to 500 ns and 700 ns, respectively. This gradient in time delay directly reflects the varying degrees of difficulty with which different metal electrodes release charge carriers under impulse excitation. Within the quasi-equilibrium state established during the wavefront phase, the shielding intensity exerted by each material on the electric field exhibits a distinct stepwise distribution. The Al-Al configuration, characterized by the highest charge injection density, suppresses the internal electric field to 71.9% of the nominal value, demonstrating the most potent electric field attenuation effect. The Fe-Fe configuration follows, with a field strength maintenance ratio of approximately 80.2%. Conversely, the electric field distribution under the Cu-Cu configuration most closely approximates the ideal distribution, maintaining a steady-state amplitude as high as 96.2% of the applied voltage, thereby exhibiting optimal dielectric stability. This evolutionary pattern of “fast response and strong shielding” is intimately correlated with the charge-to-mass ratio of the metal ions. Leveraging their smaller ionic mass and exceptionally high injection flux, Aluminum ions facilitate the establishment of a space charge shielding layer within the shortest timeframe, resulting in the earliest transition to the steady state and the lowest field strength maintenance ratio.

Figure 12.

Back-calculated Electric Field during the Wavefront.

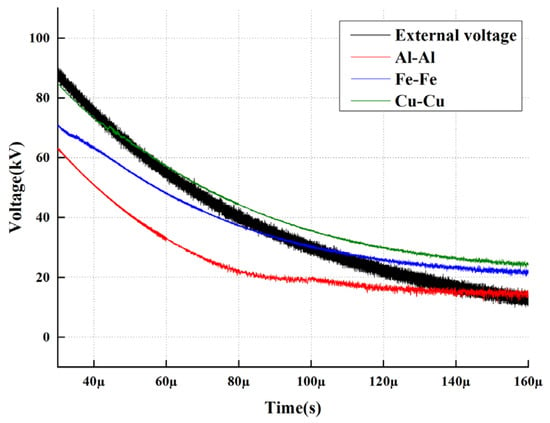

3.2.2. Analysis of Back-Calculated Voltage During the Wavetail Phase for Different Metal Electrode Combinations

With the electrode gap adjusted to 5 mm, impulse tests were conducted by applying a 2/25 μs impulse voltage with a peak amplitude of 100 kV. This section analyzes the relationship between the back-calculated electric field and the applied electric field specifically during the wavetail phase.

As indicated in Figure 13, during the wavetail decay phase of the impulse voltage, the maintenance characteristics of the electric field intensity within the oil gap exhibit significant differentiation based on the electrode material. Experimental results confirm that the internal electric field under the Cu-Cu configuration demonstrates the strongest “quasi-static stability,” with its back-calculated field strength consistently maintaining a higher magnitude; in contrast, the Al-Al and Fe-Fe configurations, due to substantial charge injection during the earlier stages, exhibit more pronounced electric field decay characteristics during the wavetail phase. This phenomenon reveals the profound modulation effect of metal materials on the dissipation rate of polarization charges. As the external voltage decays rapidly, the internal electric field exhibits a distinct “secondary enhancement,” characterized by the back-calculated electric field once again surpassing the trajectory of the applied voltage. This crossover moment exhibits a distinct gradient in the time domain: the chemically stable copper electrode is the first to transition into the overshoot state at 50 μs; conversely, for the iron and aluminum electrodes, due to more substantial initial charge accumulation, the field recovery points are delayed to 100 μs and 150 μs, respectively. This sequence of delays further corroborates that materials with high injection activity possess a more persistent shielding inertia regarding electric field distribution. By extracting the voltage magnitudes at the intersection points, it is evident that the critical level at which the system establishes field equilibrium is strongly influenced by the electrode material. The Cu-Cu configuration corresponds to the highest equilibrium threshold voltage, reaching 68.02 kV; whereas for the Al-Al system, which exhibits the strongest injection activity, the field strength does not achieve crossover until it decays to a low level of 15.01 kV. These differentiated data quantitatively reveal the degradation boundaries of the charge shielding effect at different electrode interfaces.

Figure 13.

Back-calculated Electric Field during the Wavetail.

To statistically analyze the impact of electrode materials on the electric field evolution stages, three characteristic parameters were extracted from the experimental waveforms: the Field Enhancement Duration (∆tenh) during the wavefront, the Field Retention Ratio (ηshield) during the shielding phase, and the Recovery Time Point (trec) during the wavetail.

As shown in Table 1, a strict trade-off relationship exists between the response speed and the field stability.

Table 1.

Characteristic Parameters of Field Evolution for Different Electrodes.

Wavefront Phase: The Aluminum electrode exhibits the most rapid response, with ∆tenh being only 42% of that of Copper. This confirms that light ions (Al3+) accelerate the transition from the “static” enhancement mode to the “dynamic” shielding mode.

Shielding Phase: The Al-Al configuration experiences the most severe field attenuation, retaining only 71.9% of the nominal voltage, whereas the Cu-Cu configuration behaves nearly as an ideal capacitor (η = 96.2%).

Wavetail Phase: The recovery time trec for Aluminum is delayed by 100 μs compared to Copper, indicating that the high-density space charge cloud formed by Al injection requires a significantly longer duration to dissipate or be trapped by the interface.

4. Spatial Electric Field Characteristics and Charge Injection Mechanisms

4.1. Spatial Electric Field Characteristics and Static/Dynamic Charge Distributions

The experimental waveforms reflect the non-linear response of the internal electric field within the oil–paper insulation system to external excitation, characterized by the alternating dominance of “field enhancement” and “charge shielding.” Throughout the entire sampling period, the back-calculated electric field at the center of the oil gap undergoes a progression from initial polarization enhancement to intermediate charge shielding attenuation, followed by a reconstruction of field gain during the residual wavetail phase. This phenomenon provides quantitative evidence of the spatiotemporal evolution of space charge distribution, transitioning from high localization at the interface to dispersion throughout the bulk phase. The study delineates two distinct physical response modes: Interface Bound State (Static Model): At lower excitation levels, charges are primarily constrained by the potential barrier at the electrode surface, manifesting as a surface charge layer adhering to the electrodes, thereby inducing a positive gain in the electric field within the central region. Bulk Diffusion State (Dynamic Model): As the excitation amplitude surpasses a critical injection threshold, the initial interfacial equilibrium is disrupted; a massive influx of carriers injects into the bulk of the oil–paper gap, forming a charge cloud that generates a significant shielding effect, resulting in a drastic decline in the macroscopic electric field strength. This modal transition from static to dynamic essentially reveals the dynamic shift in the injection current from the linear Ohmic regime to the Space Charge Limited Current (SCLC) regime.

To clarify the governing mechanism of the electric field evolution, a dynamic response model based on the carrier transit time (τtransit) is proposed. The model divides the impulse response into two distinct regimes:

- (1)

- The Transient Static Regime:

During the steep wavefront of the lightning impulse, the massive metal ions (e.g., Al3+) possess significant inertia. When the voltage rise time is shorter than the transit time (t < τtransit ≈ 300 ns), the injection flux is insufficient to modify the bulk potential. Consequently, the system behaves as a lossless capacitor, and the electric field strictly follows the external voltage, leading to the initial field overshoot (Transient Response).

- (2)

- The Quasi-Steady Dynamic Regime:

As the time scale extends beyond the transit threshold t > τtransit, carriers traverse the oil gap and accumulate at the interface. The system transitions into a conductive dielectric state, where the internal electric field is reshaped by the space charge. This leads to the saturation and shielding effect (Steady-State Response), where the local field strength is significantly attenuated compared to the applied voltage.

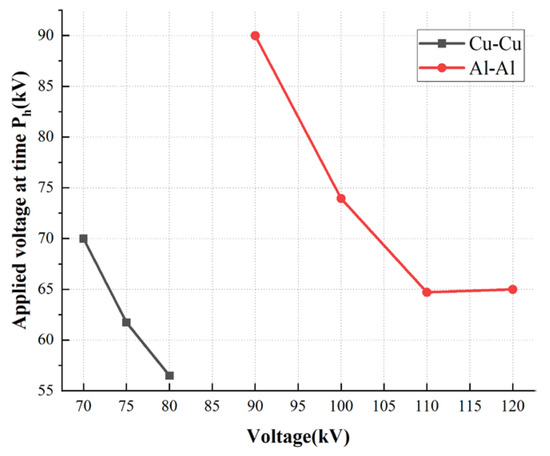

To quantify the boundary between the ‘Interface Bound State’ and the ‘Bulk Diffusion State,’ we introduce the Critical Reversal Field Strength Ecr based on the characteristic curves in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Amplitude of the Applied Voltage at the Tf moment (Conditions: 100 kV, 2/25 μs, 5 mm gap, t = 40 μs).

The determination criterion is defined as the inflection point where the derivative of the internal field with respect to the applied voltage transitions from positive to negative.

For the Al-Al configuration: As shown in the red curve of Figure 14, the back-calculated voltage reaches a peak extremum at an applied voltage of 90 kV. Therefore, the critical threshold is determined to be Ecr ≈ 18 kV/mm. When the local field exceeds this value, the injection mode shifts dominance from linear polarization to explosive space charge injection. For the Cu-Cu configuration, the characteristic curve maintains a monotonic linearity within the measured range, implying that its critical threshold is significantly higher than 18 kV/mm. This quantitative threshold Ecr serves as a practical design limit for transformer insulation: to maintain field stability and avoid unpredictable distortion, the design stress near aluminum components should be restricted below 18 kV/mm under impulse conditions.

Notably, the presence of the insulating paper layer significantly alters the time constant governing the system’s reversion to the “static” state. During the wavetail voltage decay phase, the trap effect of the paper fibers exerts a strong capture influence on residual bulk charges, enabling the system to reshape the interfacial charge distribution with greater rapidity, thereby exhibiting a “secondary enhancement” characteristic that is more pronounced than that observed in pure oil systems.

4.2. Charge Transport Processes

4.2.1. Analysis of Positive Charge Transport Processes

By synthesizing the horizontal comparisons (different metal electrode combinations under identical voltage) and vertical comparisons (identical metal configurations under varying voltages), the results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 14. Specifically, these data include the back-calculated voltages at t = 40 μs for various metal combinations under a 100 kV peak 2/25 μs impulse voltage with a 5 mm gap, as well as the applied voltages corresponding to the Tf moment for Cu-Cu and Al-Al configurations under varying applied voltages.

Table 2.

Back-calculated Voltage at 40 μs.

As indicated in Table 2, when the lower electrode is fixed and the upper electrode is varied, the back-calculated voltage exhibits significant variation. Conversely, when the upper electrode is fixed and the lower electrode is varied, the back-calculated voltages remain nearly identical. This observation suggests that under impulse voltage, charge injection into the oil gap originates primarily from the upper electrode. Furthermore, Figure 14 reveals that the back-calculated electric field is lower than the applied electric field, indicating that the charges within the oil gap are of the same polarity as the applied field (homocharge), thereby attenuating the spatial electric field. Among the three metals tested, Aluminum injects the greatest quantity of charge into the oil gap, while Copper injects the least. As the voltage increases, the applied voltage corresponding to the “Tf moment” gradually decreases, implying that the quantity of charge injected into the oil gap increases with rising voltage. Electrons within the electrode plate are bound by the attractive force of atomic nuclei.

From the perspective of energy conservation, electrons within the electrode must overcome the potential barrier imposed by atomic nuclei to achieve emission. Although the macroscopic electric field may not reach the classical emission threshold, microscopic field distortion at the oil–paper interface, combined with the quantum tunneling effect, enables the activation of trans-boundary electron emission at lower field strengths. This process establishes a positive ion emission source at the electrode surface, thereby facilitating a continuous supply of charge into the oil–paper insulation gap. The rising steepness (dV/dt) of the applied pulse determines the temporal window for interfacial injection. At lower excitation amplitudes, the rate of field growth after surpassing the emission threshold is relatively moderate; this provides a more extended temporal window for ion escape from the electrode surface, resulting in the accumulation of a higher density of equivalent charge within the gap. This “time window effect” causes the macroscopic electric field distortion rate under low-voltage conditions to potentially exceed that observed under high-voltage conditions, reflecting the time-domain sensitivity of the injection process.

It can be inferred that during the time interval ∆t = t2 − t1, the charges have already migrated to the spatial location probed by the laser. When the impulse generator discharges onto the electrode plate, electrons within the plate are withdrawn by the power source. Consequently, a positive ion emission source is formed on the metal surface, continuously injecting charges into the transformer oil.

Based on the classical mechanics formula for acceleration α = qE/m, the charge-to-mass ratios for the metals can be expressed as α(Al3+): α(Fe3+): α(Fe2+): α(Cu2+) = 3/27: 3/56: 2/56: 2/65. Due to the Aluminum ion’s lower mass and higher charge magnitude, it possesses a higher charge-to-mass ratio and is thus more readily injected into the transformer oil. Conversely, the Copper ion, possessing the lowest charge-to-mass ratio, exhibits the highest resistance to injection compared to Aluminum and Iron.

To rigorous quantify the relationship between electrode material properties and charge injection intensity, we derive a transport model based on microscopic ion dynamics. Under the transient high-field impulse, the motion of injected ions is governed by the ballistic drift approximation. The instantaneous drift velocity vd is given by Equation (5):

where q is the ion charge, m is the ion mass, and is the mean free time dependent on the fluid viscosity. The resulting injection current density J can be expressed as

Equation (6) reveals that the injection capability is proportional to the factor . Comparing the experimental materials, it can be worked out that, for Aluminum (Al3+), , and for copper (Cu2+), .

The theoretical ratio indicates that Aluminum electrodes are theoretically capable of generating an injection flux over five times stronger than Copper under identical conditions. This theoretical prediction aligns perfectly with the experimental observations in Figure 12, where the Al-Al configuration exhibits the most rapid and severe field distortion due to massive space charge accumulation, whereas the Cu-Cu configuration maintains high field fidelity.

Note on Model Scope: It should be explicitly noted that the “Static–Dynamic” transition model proposed herein is primarily intended as a conceptual physical framework to interpret the spatiotemporal evolution of the electric field. Although a semi-quantitative derivation linking the injection intensity to the ion charge-to-mass ratio is provided to explain the material-dependent differences, the overall framework does not currently serve as a fully quantitative predictive model involving explicit drift-diffusion differential equations or Space Charge Limited Current (SCLC) formulations. Future work will focus on incorporating numerical simulations to further mathematize this framework.

However, it is important to note that the observed space charge evolution represents an effective charge transport process. While the charge-to-mass ratio α of metal ions explains the difference in injection intensity between Aluminum and Copper, the extremely fast response observed at the wavefront (<300 ns) suggests the involvement of fast electronic carriers (e.g., free electrons or solvated electrons). The physical picture is a coupled mechanism: high-field ionization at the electrode interface generates both metal cations and electrons (M = Mn+ + ne−). The fast electrons rapidly propagate into the bulk, initiating the wavefront distortion, while the massive cations (governed by α) constitute the dense space charge cloud that sustains the field distortion in the longer timescale. Thus, the measured Kerr signal reflects the superposition of these electronic and ionic contributions.

Comparison with High-Polarity Fluid Studies: Early classic works by Zahn’s team at MIT utilized propylene carbonate (PC) as the dielectric. Due to the high permittivity and high Kerr constant of PC, charge injection typically follows a bipolar homocharge pattern with extremely fast relaxation times, resulting in rapid field shielding. In contrast, this study uses transformer oil. The lower ion mobility in oil creates a significant “time lag” between voltage application and charge accumulation. This allows for the observation of the “Initial Field Enhancement” phase before shielding takes effect, a transient phenomenon that is often negligible in high-polarity fluid studies.

4.2.2. Analysis of Negative Charge Transport Processes

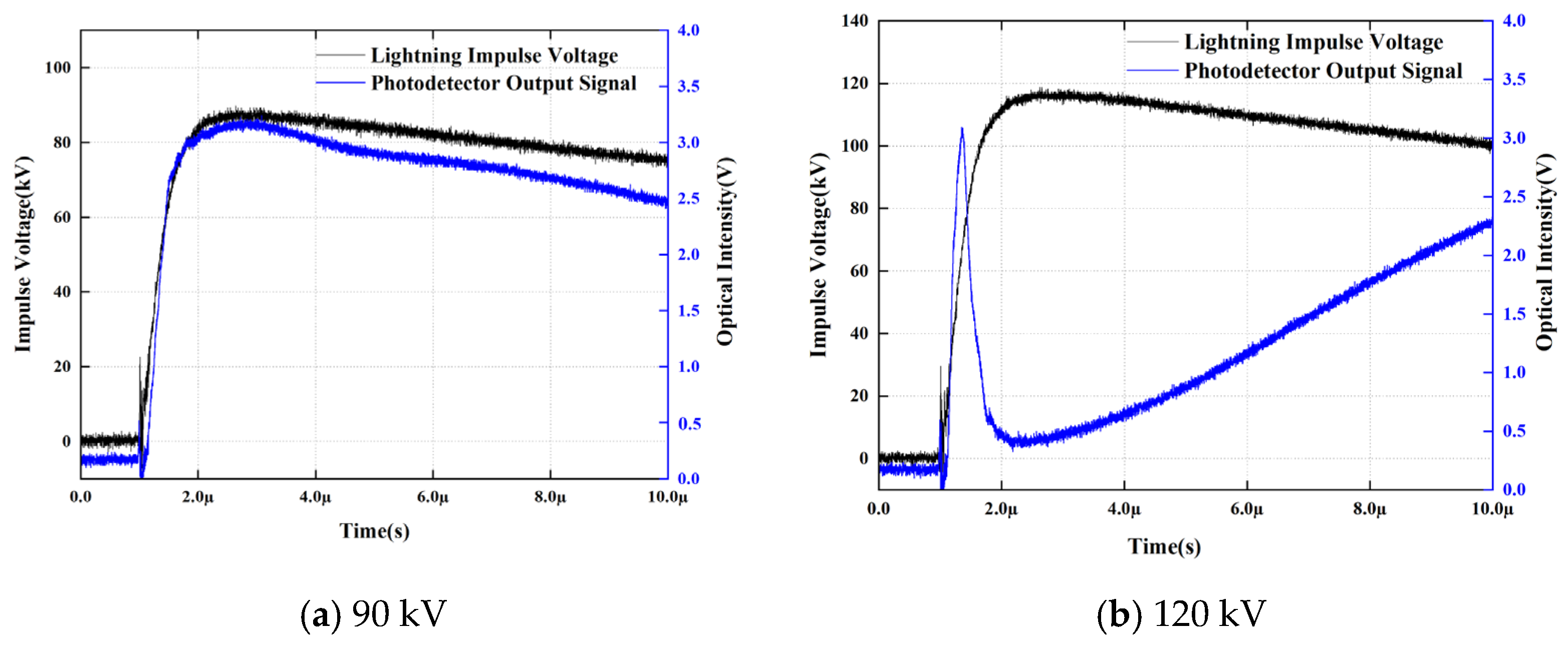

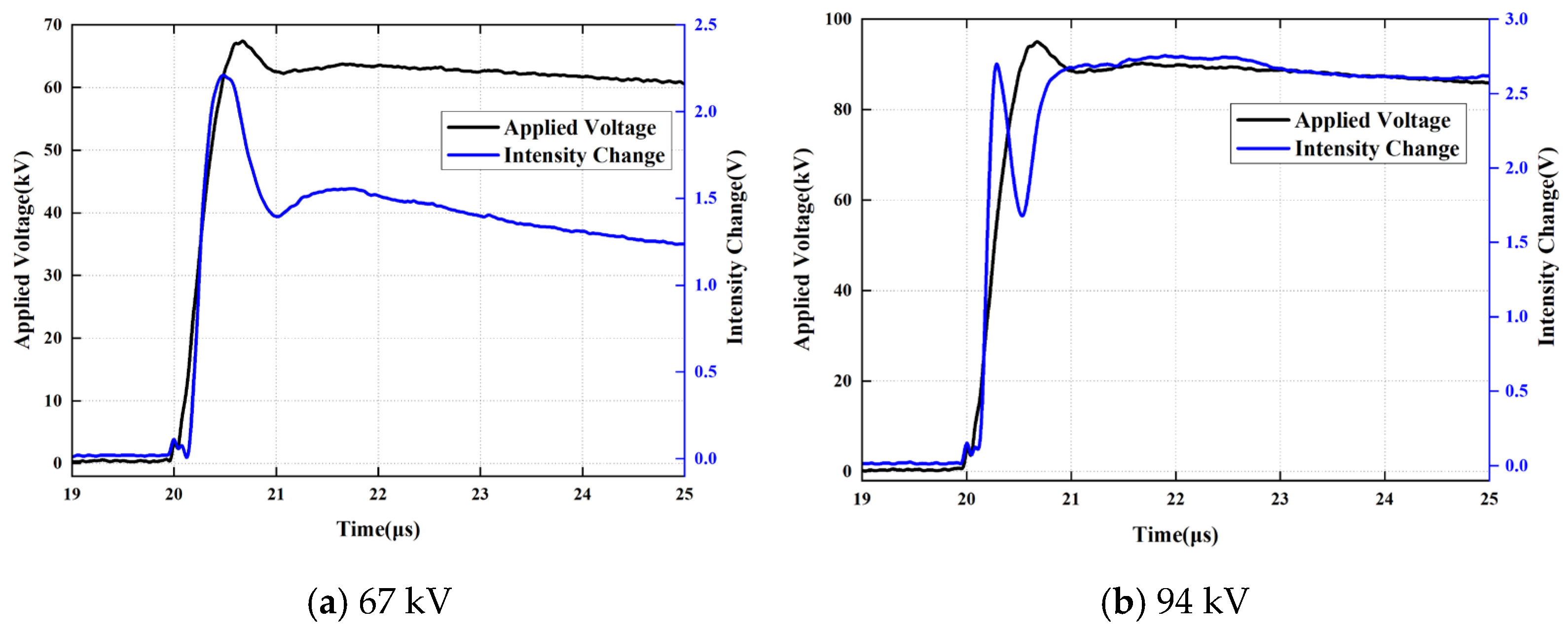

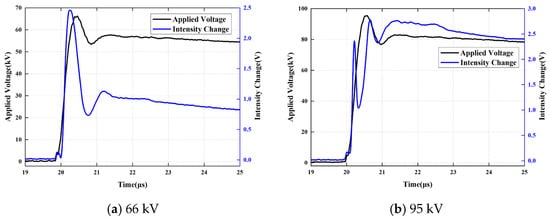

A comparative analysis of the impulses with wavefront times of 0.5/25 μs and 0.7/25 μs reveals that as the peak applied voltage increases, the amplitude of the applied voltage at the “Tf moment” exhibits a trend of initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease. Furthermore, it is established that for a constant wavefront time, an increase in the peak voltage magnitude inherently results in a greater rate of voltage rise (dV/dt), as illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Amplitude of the Applied Voltage at the Tf moment (Comparative analysis of 0.5/25 μs and 0.7/25 μs waveforms).

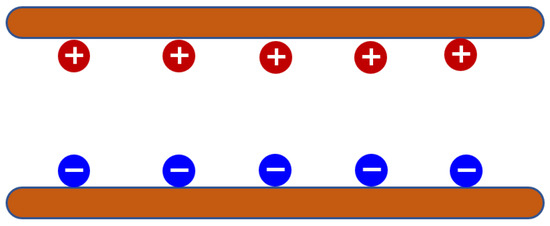

Regarding the phenomenon where the applied voltage corresponding to the first peak observed by the photodetector exhibits an initial increase followed by a decrease, it is hypothesized that this behavior is primarily driven by the transport of negative charges (predominantly electrons). Initially, the accumulation of positive charges near the upper electrode and negative charges near the lower electrode acts simultaneously to enhance the electric field within the oil gap. The reasoning and analytical process is detailed as follows:

- (1)

- The rate of increase of the applied electric field E1, generated by the high peak voltage (Figure 16), exceeds the migration speed of the negative charges. Consequently, by the time the resultant electric field E reaches the magnitude Em, the negative charges have not yet migrated to the specific region of the oil gap traversed by the optical path. In this scenario, both the positive space charge field E2+ and the negative space charge field E2− act to enhance the field within the measurement volume. Specifically, relative to the optical path, the vectors of E2+ and E2− are aligned in the same direction as E1.

Figure 16. Space Charge Distribution at the Tf moment under High Peak Voltage (+: positive charges; −: negative charges).

Figure 16. Space Charge Distribution at the Tf moment under High Peak Voltage (+: positive charges; −: negative charges). - (2)

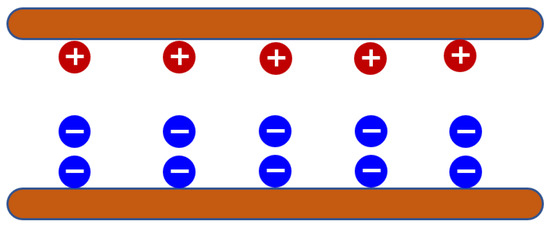

- Under conditions of medium peak voltage (Figure 17), the rate of increase of the generated electric field E1 is comparable to the migration speed of the negative charges. Consequently, at the moment when the resultant electric field E reaches the magnitude Em, the negative charges have just arrived at the spatial region of the oil gap traversed by the optical path. In this scenario, the positive space charge field E2+ acts to enhance the field within the measurement space, whereas the negative space charge field E2− acts to attenuate it. Specifically, relative to the optical path, the vector of E2+ is aligned in the same direction as E1, while the vector of E2− is oriented in the opposite direction.

Figure 17. Space Charge Distribution at the Tf moment under Medium Peak Voltage (+: positive charges; −: negative charges).

Figure 17. Space Charge Distribution at the Tf moment under Medium Peak Voltage (+: positive charges; −: negative charges). - (3)

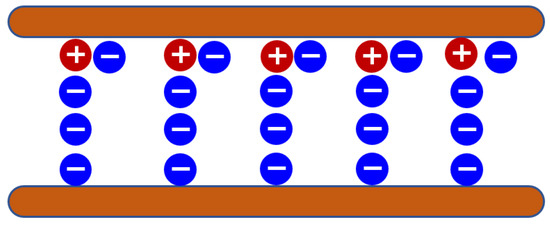

- Under conditions of low peak voltage (Figure 18), the rate of increase of the generated electric field E1 is lower than the migration speed of the negative charges. Consequently, by the time the resultant electric field E reaches Em, the negative charges have already migrated to the upper electrode and have been neutralized by the positive charges residing there. In this scenario, the positive space charge field E2+ acts to enhance the field within the measurement space, whereas the negative space charge field E2− acts to attenuate it. Relative to the optical path, the vector of E2+ remains aligned with E1, while the vector of E2− is oriented in the opposite direction; however, the absolute magnitude of E2− is notably reduced.

Figure 18. Space Charge Distribution at the Tf moment under Low Peak Voltage (+: positive charges; −: negative charges).

Figure 18. Space Charge Distribution at the Tf moment under Low Peak Voltage (+: positive charges; −: negative charges).

The time required for the 5 mm oil gap to be filled with negative charges is given by Equation (7).

The parameters used for the calculation are defined as follows: t0: The wavefront time. E//: The applied voltage at the “Tf moment” under the condition where positive charges near the upper electrode and negative charges near the lower electrode maximally enhance the electric field within the oil gap. Ep: The peak applied voltage corresponding to the condition of maximal field enhancement (E// scenario). E/: The applied voltage at the “Tf moment” under the condition where the direction of E2− opposes E1, yet the resultant field (E1 + E2+ − E2−) reaches its maximum. En: The peak applied voltage corresponding to the condition described for E/.

Based on an estimation using a wavefront time of t0 = 500 ns, the following values are obtained: For a peak voltage scenario of 79 kV, E// = 74.0609 kV and Ep = 79 kV. For a peak voltage scenario of 95 kV, E/ = 44.5347 kV and En = 95 kV. Substituting these values into the formula, ∆t = 234.347 ns, the time required for negative charges to completely fill the oil gap is calculated to be approximately 200 ns. It can be deduced that the transit time for electrons migrating from the lower electrode to the upper electrode is less than 200 ns.

To verify the reliability of the calculated 200 ns transit time, the average migration velocity v of the negative charges was derived: v = d/∆t = 5 mm/200 ns = 25 km/s.

This calculated velocity is significantly higher than the mobility-controlled drift velocity of ions, indicating that the transport process is dominated by electronic mechanisms or streamer precursors under high electric fields.

According to classic studies on pre-breakdown phenomena in dielectric liquids, the propagation velocity of negative streamers in transformer oil typically ranges from 1 km/s to 100 km/s depending on the voltage amplitude [24,25]. The calculated value of 25 km/s in this study aligns perfectly with these literature values. This consistency validates that the Kerr-effect-based inversion algorithm accurately captures the fast transient dynamics of negative charge carriers.

Comparison with Pure Oil Gap Studies: Prof. Yang Qing’s team has extensively investigated space charge in transformer oil, primarily focusing on pure oil gaps or nanofluids under step voltages. Their results typically show a monotonic decay of the electric field due to bulk injection. By introducing the cellulose insulating paper, our study reveals Wavetail Secondary Enhancement. This phenomenon is attributed to the effect of the paper interface, which prevents the rapid dissipation of charges observed in pure oil gaps.

4.2.3. Comprehensive Analysis of Positive and Negative Charge Transport Processes

With the peak voltage fixed at 94 kV and the wavetail duration held constant at 25 μs, the wavefront time was varied. It is observed that as the wavefront time gradually increases, the quantity of equivalent space charge accumulated at the “Tf moment” within the region probed by the laser increases significantly. Consequently, the effect of the space charge transitions from enhancing the electric field at the measurement location to attenuating it. Once the wavefront time reaches 10 μs, the influence of the space charge on the electric field achieves a steady state. In this regime, the “Tt moment” consistently corresponds to this stable condition, as presented in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Applied Voltages at Tt/Tf Moments (94 kV Peak, Different Wavefronts, Identical Wavetails).

Table 4.

Equivalent Space Charge at Tt/Tf Moments (94 kV Peak, Different Wavefronts, Identical Wavetails).

Under the experimental condition of a 25 μs wavefront, the equivalent space charge at the “Tf moment” within the region probed by the laser is equal to that observed at the “Tt moment”. This equality indicates that the charge distribution within the oil gap has attained an “equilibrium state” within the duration of the wavefront. Furthermore, for a constant wavetail duration, the equivalent space charge at the “Tt moment” remains constant regardless of variations in wavefront time or voltage levels. Consequently, the equivalent space charge at the “Tt moment” is defined as the “equilibrium value.” It is important to note that this equilibrium value varies depending on the specific metal electrodes and external experimental conditions. Chronologically, the process can be delineated as follows: following the conclusion of the “0–2 μs step phase,” the space charge within the oil gap enters a “2–10 μs near-saturation phase,” and subsequently establishes the “equilibrium state” thereafter.

Based on the analysis, the following core conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- The “step phase,” characterized by a significant rate of space charge growth and the complete filling of the oil gap by positive charges, has a duration of 2 μs.

- (2)

- During the wavetail phase of high-voltage impulses, the space charge within the oil gap attains an “equilibrium state.” Notably, this equilibrium state is independent of both the applied voltage amplitude (provided the magnitude is sufficiently high) and the wavefront time.

- (3)

- The total duration required for the charges to establish this equilibrium state is approximately 10 μs.

5. Conclusions

This study utilized Kerr electro-optic telemetry to reveal the transient electric field evolution in oil–paper insulation under lightning impulses. The core findings are as follows:

- (1)

- Mechanism of Mode Transition: A “Static–Dynamic” transition mechanism is confirmed. The electric field initially follows a capacitive distribution (Static Mode) before shifting to a space-charge-dominated distribution (Dynamic Mode), driven by the synergy between electrode injection and interface trapping.

- (2)

- Dominance of Charge-to-Mass Ratio: The injection intensity is governed by the ion charge-to-mass ratio (α). Aluminum electrodes (α≈0.11) exhibit severe field distortion (shielding factor ~71.9%), whereas Copper electrodes (α ≈ 0.03) maintain high field fidelity (>96%).

- (3)

- Quantified Time Constants: The negative charge transport across a 5 mm gap completes within ~200 ns, while positive charge accumulation requires ~10 μs to reach equilibrium.

- (4)

- Engineering Implications: To mitigate transient field distortion, it is recommended to avoid bare aluminum alloys in high-stress regions (using copper or shielding instead) and ensure the insulation spacing design accounts for the transit-time threshold (d > v × trise) to prevent dynamic injection during the wavefront.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. (Xiaolin Zhao) and C.G.; methodology, H.Z. and B.Q.; validation, X.Z. (Xiang Zhao); formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, X.Z. (Xiaolin Zhao); resources, S.Z.; data curation, H.Z., Y.Z. and X.Z. (Xiang Zhao); writing—original draft preparation, X.Z. (Xiaolin Zhao) and H.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.Z. and C.G.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, X.Z. (Xiaolin Zhao), C.G., B.Q. and S.Z.; project administration, B.Q. and S.Z.; funding acquisition, B.Q. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the headquarters technology project of State Grid Corporation of China (Project Code: 52100125003C-272-XN).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to kiddgcj@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from State Grid Corporation of China. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- He, D.; Guo, H.; Gong, W.; Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Xie, S. Dynamic behavior and residence characteristics of space charge in oil-paper insulation under polarity–reversal electric field. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2023, 30, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Gao, C.; Han, H.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, C. Electric field distribution characteristics and space charge motion process in transformer oil under impulse voltage. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 103781–103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Wu, Y.; Song, H.; Xing, Z.; Huang, M.; Liu, B.; Lv, Y.; Li, C. Research on DC Breakdown Performance of Nanofluid-impregnated Pressboard Based on TiO2 Nanoparticles. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Dielectrics (ICD), Valencia, Spain, 5–31 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, X. Insulation structure of UHV power transformer. High Volt. Eng. 2010, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Gao, C.; Zhao, L.; Sun, X. Oil-pressboard interface charges under combined AC/DC electric field: Their characteristics and influence on surface flashover voltage. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC), Seattle, WA, USA, 7–10 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Lv, Z.; Wu, K. Comparison of charge mobility in insulating oil and oil-immersed paper. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP), Denver, CO, USA, 30 October–2 November 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imburgia, A.; Romano, P.; Ala, G.; Albertini, M.; De Rai, L.; Bononi, S.F.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Rizzo, G.; Siripurapu, S.; Viola, F. Effect of polarity reversal on the partial discharge phenomena. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP), Virtual, 18–30 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, M.; Takada, T. High voltage electric field and space-charge distributions in highly purified water. J. Appl. Phys. 1983, 54, 4762–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C. Studies on the DC Space Charge Characteristics of Oil-Paper Insulation Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faruque, H.S.; Lacabanne, C. Study of multiple relaxations in PEBAX, polyether block amide (PA12 2135 block PTMG 2032), copolymer using the thermally stimulated current method. Polymer 1986, 27, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Takada, T. Progress in space charge measurement of solid insulating materials in Japan. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 1994, 10, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, Z. Space charges in dielectrics. Prog. Dielectr. 1965, 6, 103–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, E.C.; Hebner, R.E.; Zahn, M.; Sojka, R.J. Kerr-effect studies of an insulating liquid under varied high-voltage conditions. IEEE Trans. Electr. Insul. 1974, EI-9, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, A.; Zahn, M. Kerr electro-optic measurements of space charge effects in HV pulsed propylene carbonate. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2002, 9, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Bo, Q.; Chengrong, L. Methods to Decrease the Measuring Errors of DC Electric Field Measurement. High Volt. Eng. 2013, 39, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Qi, B.; Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, L.; Lu, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Y. The measurement of AC-DC composite field for oil-paper insulation system based on the Kerr electro-optic effect. Diangong Jishu Xuebao 2013, 28, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, W. Space charge injection and transport in propylene carbonate under switching impulse voltage. Proc. CSEE 2014, 34, 6568–6577. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, W.; Guo, H.; Yang, Q.; Song, H.; Yang, M.; Yu, F. Electric field and space charge distribution measurement in transformer oil struck by impulsive high voltage. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 082905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, W.; Song, H.; Yang, Q.; Guo, H.; Zahn, M.; Yang, M. Time-continuous Kerr electro-optic field mapping measurement under impulse voltage using array photodetector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 082901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, F.; Sima, W.; Zahn, M. Space charge inhibition effect of nano-Fe3O4 on improvement of impulse breakdown voltage of transformer oil based on improved Kerr optic measurements. AIP Adv. 2015, 5, 097207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, F.; Sima, W.; Yuan, T.; Jin, Y.; Song, H. Inhibition effect of space charge transportation on impulse breakdown performance of propylene carbonate with Al2O3 nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 063104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffel, J.; Kuffel, P. High Voltage Engineering Fundamentals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Gao, C.; Xie, Z.; Ge, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, X.; Pan, Z.; Qi, B. Electric Field Features and Charge Behavior in Oil-Pressboard Composite Insulation Under Impulse Voltage. Energies 2024, 17, 4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgaard, L.; Linhjell, D.; Berg, G.; Sigmond, S. Positive and negative streamers in oil gaps with and without pressboard interfaces. In Proceedings of the ICDL’96—12th International Conference on Conduction and Breakdown in Dielectric Liquids, Rome, Italy, 15–19 July 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhjell, D.; Lundgaard, L.; Berg, G. Streamer propagation under impulse voltage in long point-plane oil gaps. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 1994, 1, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.