Abstract

Solar advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) utilising parabolic trough concentrators (PTCs) present a promising approach for the sustainable removal of recalcitrant contaminants from wastewater. This mini-review critically evaluates 25 peer-reviewed studies employing PTC-AOP systems for the degradation of chemical pollutants and microbial pathogens. Reported applications include photolysis, photo-Fenton and photocatalysis for the treatment of synthetic dyes, contaminants of emerging concern, industrial effluents, heavy metals and pathogenic microorganisms. A performance-oriented comparison based on normalised indicators is introduced. The time required for one order-of-magnitude reduction (corresponding to 90% removal; τ90) reveals a significant mineralisation setback, where parent-compound degradation outpaces total organic carbon removal. The PTC concentration ratio and photon utilisation metrics highlight substantial variability in reactor design (geometry, materials, optical performance), which directly influences the treatment kinetics. Overall, PTC-AOP systems demonstrate strong potential as a polishing step within hybrid wastewater treatment. Future research should prioritise the standardisation of performance metrics, the catalyst design suited for high-photon and -temperature operation, and the integration into scalable and climate-resilient solar wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

The Anthropocene clearly represents socio-economic growth driven by technological progress but also unprecedented pressure on the Earth’s systems, particularly the global water cycle [1]. Human-caused climate change is the main driver of weather extremes (heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts, floods), which destabilise freshwater availability [2]. Also, pollution and ecosystem degradation have a harmful impact on both the quality and quantity of accessible water resources [3]. While the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim for universal access to clean water (SGD6 goal), current data indicates that out of 187 billion m3 wastewater (WW) generated annually, only 56% of domestic WW is safely treated [4]. A critical scientific problem remains: conventional secondary treatment processes are frequently unable to remove recalcitrant organic pollutants, emerging contaminants and pathogens. Their persistence presents a barrier to achieving the high-quality reclaimed water needed for industrial circularity and unrestricted irrigation.

To address this, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are required as tertiary or quaternary treatment [5,6]. Unlike state-of-the-art technologies such as membrane filtration [7], where pollutants are transferred to the concentrated waste stream, AOPs utilise hydroxyl radicals (•OH) to mineralise toxic pollutants to inorganic species [8,9]. However, their practical implementation is often hindered by high energy consumption and the associated operational and maintenance costs of artificial UV irradiance [9,10].

Integration of solar energy through Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) systems offers a sustainable solution for these constraints. Recent studies highlight the potential of solar-assisted AOPs to enhance treatment efficiency while reducing energy demand [6,8,11,12,13,14,15,16]. As shown in Table 1, various reactor designs, like the Raceway Pond Reactor (RPR), Inclined Plate Collector (IPC) and Compound Parabolic Collector (CPC), are utilised [5,8,12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. However, the Parabolic Trough Collector (PTC) stands out for its superior optical performance in concentrated photochemical applications. While CPCs are limited by low concentration ratios (CR), PTC systems utilise parabolic mirrors to concentrate direct solar radiation onto a receiver tube, achieving a higher photon concentration per volume unit. Quantitatively, this feature facilitates faster •OH radical production rates and reaction kinetics, making PTCs more efficient for treating concentrated or highly toxic industrial streams compared to non-concentrating or stationary collectors.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of CSP systems for AOP wastewater treatment.

Selecting between PTC and CPC designs involves additional critical performance trade-offs [22,24]:

- Turbidity tolerance—CPCs are often more robust when treating turbid wastewaters or operating on cloudy days, since they capture both direct and diffuse irradiation. In contrast, PTC efficiency depends on direct irradiation, which makes them sensitive to cloud cover and water turbidity, which scatters photons.

- Mass transfer and fluid dynamics—While both systems aim for high optical efficiency, the intense energy concentration in PTC allows for a more compact reactor footprint. Furthermore, PTCs typically maintain turbulent flow within the receiver tube, ensuring mass transfer and efficient mixing of the WW, catalyst and oxidant.

- Operational complexity and cost—PTC requires precise (automated) solar tracking systems to keep the aperture perpendicular to solar rays, which increases the initial capital investment and maintenance requirements. In contrast, the stationary design of the CPC reduces mechanical complexity and costs, though it requires a larger land area to achieve comparable treatment volumes.

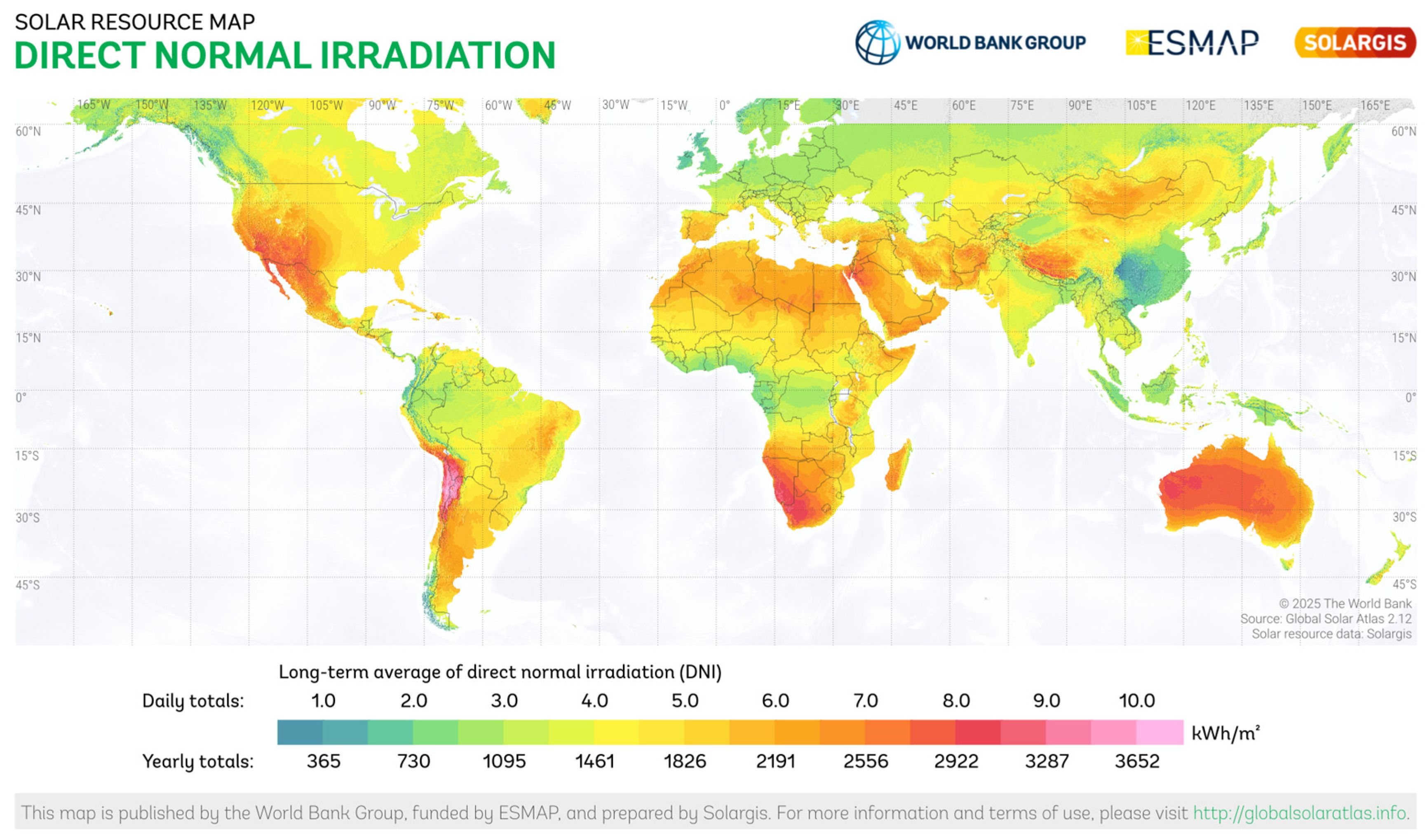

The feasibility of CSP systems, especially PTCs, is inherently tied to the availability of Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) [20,25,26]. An analytical mapping of global DNI (Figure 1) shows that regions with the highest solar potential are simultaneously recognised as climate-change hotspots experiencing severe water depletion and drought, such as the Mediterranean and Balkan basins [27]. In these contexts, the integration of PTC-driven AOPs represents not only an engineering option, but a strategic approach to enhance water resilience through safe, low-energy wastewater treatment and reuse.

Figure 1.

World map of direct normal irradiation (map obtained from the “Global Solar Atlas 2.12”, a free, web-based application developed and operated by the company Solargis s.r.o. on behalf of the World Bank Group, utilising Solargis data, with funding provided by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP). For additional information: https://globalsolaratlas.info (accessed on 17 November 2025).

Despite the scientific progress in CSP-assisted treatments, existing knowledge on PTC-AOPs remains scattered across diverse experimental setups and geographical contexts. There is a lack of standardised performance metrics, which hinders direct comparison of treatment efficiencies and reactor designs. To address this research gap, the aim of this paper is to provide a structured, performance-oriented assessment of PTC-driven solar AOPs. This review introduces and applies normalised evaluation criteria, such as the time required for a one-order-of-magnitude reduction (τ90) and the photon utilisation ratio (PU), to assess current research and identify future directions for scalable and climate-resilient solar wastewater treatment.

2. Methodology

A systematic search was conducted in the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases to identify peer-reviewed research papers published between 2000 and 2025. The search strategy employed specific field tags in Scopus (article title, abstracts and keywords) and WoS (Topic) to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature. The exact search strings (with Boolean operators) and the search results were as presented:

- “wastewater treatment” AND “advanced oxidation process”—this search resulted in highest number of publications, with 8306 in Scopus and 7981 in WoS;

- “wastewater treatment” AND “advanced oxidation process” AND “parabolic trough collector/concentrator”—resulted in 0 publications in Scopus and 84 in WoS;

- “wastewater treatment” AND “parabolic trough collector/concentrator”—resulted in 27 publications in Scopus and 24 in WoS.

Following the initial identification of search results, duplicates were removed, and a screening process was applied. To satisfy the requirement for explicit selection criteria, the following parameters were used during title, abstract and full-text evaluations (Table 2). After full-text evaluation, 25 studies that employed a PTC system for wastewater treatment processes were included for final review. Key variables, such as PTC configuration, AOP type, treated pollutants and process efficiencies, were extracted and further evaluated. All collected data are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Calculations for Performance Review

Due to incomplete data in several studies, additional variables were calculated where sufficient information was provided. The following equations were used [28,29,30]:

- PTC receiver volume (or irradiated volume; Virr (L)), assuming cylindrical geometry, where dr is receiver diameter (inner or outer, depending on availability; cm) and lr is receiver length (cm):

- Recirculation number (RN), defined as the ratio between the total treated WW volume (Vtotal; L) and irradiated volume (Virr; L):

- Residence time (tres) represents the time that WW remains under irradiation in the PTC-AOP system, where Q represents flow rate (L/min):

- PTC concentration ratio (CR) was approximated using the PTC parabola width (wp; cm) and receiver’s outer diameter (dr; cm):

- PTC aperture area (A; m2), where lp is parabola length and wp is parabola width:

- Photon utilisation ratio (PU; m2/L) indicates the extent of concentrated solar irradiation (A; m2) applied to the WW in the PTC receiver (Virr; L):

- The pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant (kFO) was calculated, where process efficiency (eff) or mineralisation (min) and reaction time (t; min) were reported:

- Finally, the time required to reduce the pollutant concentration by one order of magnitude (90%; τ90) was determined based on the calculated kFO for process efficiency or mineralisation:

3. Overview of PTC-Driven AOPs for WW Treatment

The successful application of PTCs in advanced WW treatment requires a holistic evaluation of engineering design, process parameters, the complexity of the water matrix, and the economic and environmental feasibility of scaling up the technology. The following sections provide a detailed insight into these aspects, strictly based on the selected 25 studies.

3.1. Wastewater Treatment in PTC-AOP System

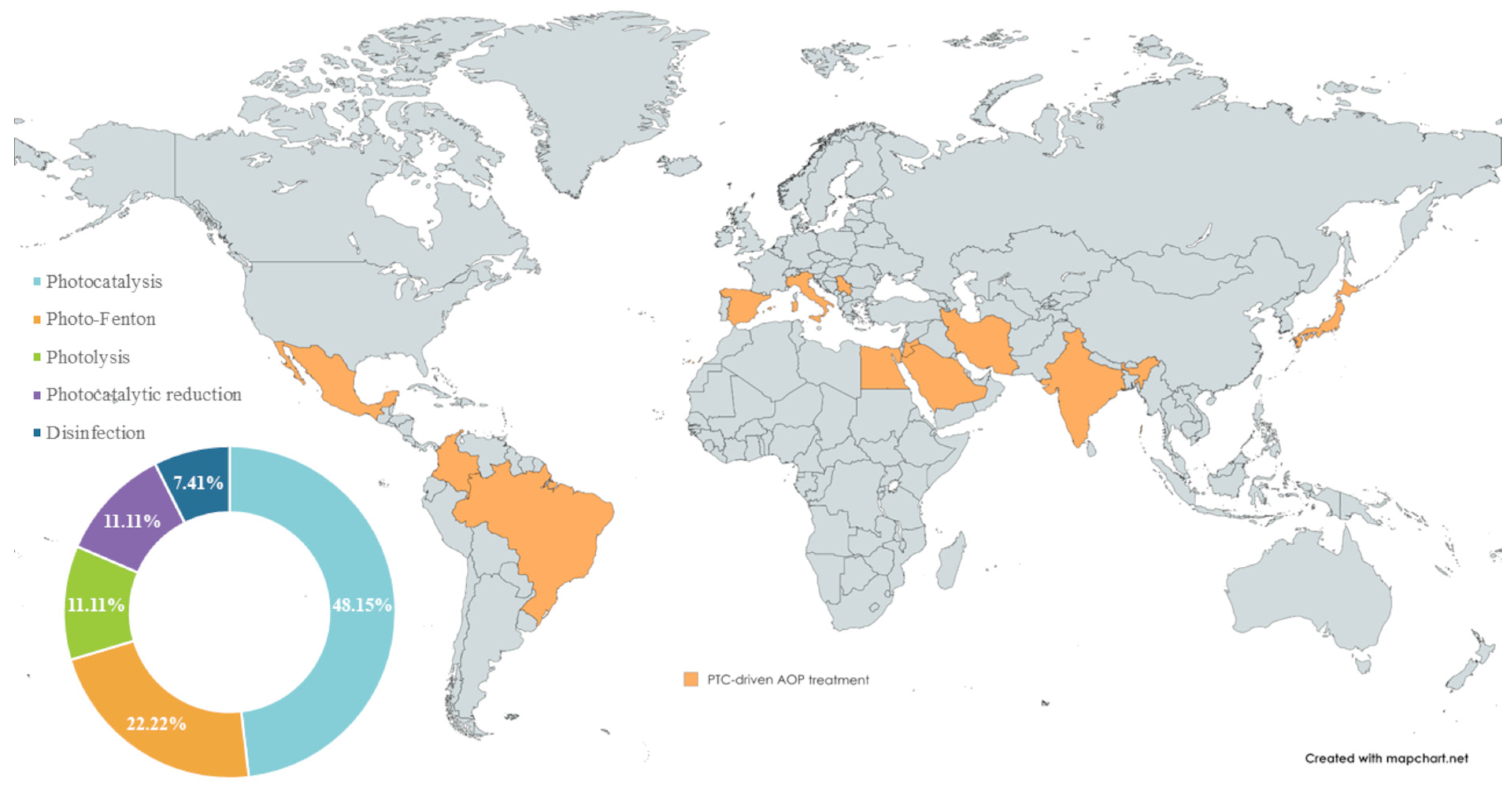

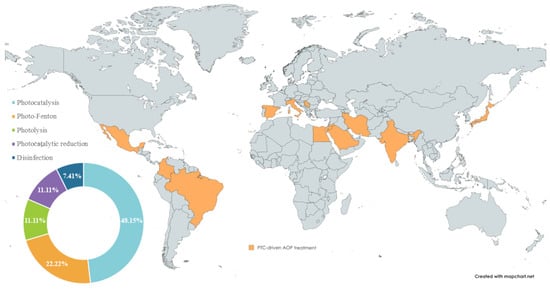

The reviewed studies demonstrate the utilisation of solar radiation for treating various pollutants, employing PTC as a prominent photochemical reactor. The benefit of the high-energy photon transfer has been exploited in photocatalysis, photo-Fenton, photolysis, and UV disinfection, across regions with high and moderate DNI. Figure 2 presents the global distribution of PTC-based applications, with the highest number of studies originating from India (8), Brazil and Egypt (3), Serbia and Iran (2), and Italy, Spain, Colombia, Japan, Mexico, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia (1).

Figure 2.

Global coverage of PTC-driven solar WW treatment research and the distribution of applied processes.

The same figure also illustrates the distribution of AOP implementation across selected papers. The detailed overview of pollutants and microbial pathogens treated in PTC-AOP systems (Table 3) highlights the versatility of this technology. The reported treatment outcomes include removal efficiency and/or mineralisation, and it is important to distinguish the difference between these two metrics. For dye molecules, decolourisation represents the initial step of colour removal, where chromophore functional groups are broken. Similarly, for other pollutants, process efficiency describes a decrease from the initial concentration, whereas mineralisation is a slower process involving the (complete) conversion of intermediate byproducts into inorganic species (H2O, CO2, inorganic ions) [31,32,33,34].

The simplest process mechanism belongs to the photolysis, which involves either the direct or indirect (oxidant-assisted •OH radical production) breakdown of contaminants by UV light. Direct photolysis achieved up to 80% mineralisation of organic content in real textile effluent [35], while promising dye degradation was also reported for H2O2-induced photolysis [17,31]. Nevertheless, the considerable differences in initial dye concentrations across studies remain an important factor. Real textile effluents contain high loads of organic and inorganic matter, where unfixed dyes may reach concentrations of up to 300 mg/L [36]. Future pilot-scale applications of PTC-AOP systems should examine treatment of concentrated textile WW streams.

When the target contaminants of photolysis are microbial pathogens, photolysis is described as disinfection due to the reaction pathway—microorganism inactivation by damage to genetic material. The UV disinfection of surface [29] and diluted real WW [37] in PTC systems has been applied to diverse resistant and pathogenic organisms (E. coli, total coliforms, faecal coliforms, etc.). UV irradiation, together with elevated water temperatures, can induce microbial inactivation and even pasteurisation (temperatures > 60 °C). For instance, LFR coupled with PTC enabled water heating up to 92 °C, resulting in the inactivation of highly resistant Acanthamoeba cysts and Bacillus subtilis spores [38].

Table 3.

Summary of water pollutants treated in PTC-driven WW treatment.

Table 3.

Summary of water pollutants treated in PTC-driven WW treatment.

| Pollutant | Concentration | Medium 1 | Process 2 | Ref. | Pollutant | Concentration | Medium 1 | Process 2 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dye | Tetracycline | 10 mg/L | S | PC | [30] | ||||

| Dyes | - | RE | P | [35] | Amoxicillin | 100 mg/L | S | PC | [39] |

| Remazol Brilliant Blue | 60 mg/L | S | P | [17] | Industrial effluents | ||||

| Reactive Red 120 | 100 mg/L | S | P | [31] | Simulated WW | 7500 mg COD/L | S | PC | [40] |

| PF | Olive oil WW | - | S | PF | [41] | ||||

| Methylene Blue | 10 mg/L | S | PC | [33] | Municipal WW | 440 mg COD/L | S | PC | [42] |

| Rhodamine B | 15 mg/L | S | PC | Paper mill WW | 490 mg COD/L | RE | PC | [43] | |

| 2 mg/L | S | PC | [30] | Dairy processing WW | 569 mg COD/L | RE | PC | ||

| Methylene Blue | 5 mg/L | S | PC | Oil-field WW | 80 mg DOC/L | RE | PF | [25] | |

| Methyl Orange | 5 mg/L | S | PC | Tannery WW | 1428 mg COD/L | RE | PC | [44] | |

| Magenta dye | 100 mg/L | RE | PC | [45] | Gold mine WW | 2948 mg CN−/L | RE | PC | [46] |

| Aminosilicone | 50 mg CN−/L | S | PC | ||||||

| Silicone emulsion | 653 mg COD/L | S | PF | [25] | Metal | ||||

| Phenol | Cr | 6.88 mg Cr/L | RE | PCR | [44] | ||||

| Phenol | 100 mg DOC/L | S | PF | Cr(VI) | 20 mg/L | S | PCR | [47] | |

| 550 mg DOC/L | S | PF | Pb | 20 mg/L | S | PCR | [48] | ||

| 100 mg TOC/L | S | PF | [49] | Cu | 20 mg/L | S | PCR | ||

| Natural organic matter | Ni | 20 mg/L | S | PCR | |||||

| Humic acid | 50 mg/L | S | PF | [50] | Zn | 20 mg/L | S | PCR | |

| Organic acid | Microbial | ||||||||

| Oxalic acid | 900 mg/L | S | PC | [51] | E. coli log | 7.55 × 102 MPN/100 mL | RSW | D | [29] |

| Organic alcohol | E. coli | 1 × 106 CFU/mL | S | PC | [52] | ||||

| Methanol | 3204 mg/L | S | PC | [20] | E. coli | 1.2 × 105 CFU/mL | S | PC | [30] |

| Pesticide | Total coliforms log | 2.94 × 103 MPN/100 mL | RSW | D | [29] | ||||

| Clomazone | 97 mg DOC/L | S | PF | [25] | Total coliform | 70,000 MPN/100 mL | DRE | D | [37] |

| Thiophanate-methyl | 1369 mg/L | S | PF | [32] | Total heterotrophic | 1.034 × 104 CFU/mL | RE | D | [29] |

| Isoproturon | 25 mg/L | S | PC | [53] | bacterial count log | ||||

| Pharmaceutical | Total bacterial counts | 300,000 MPN/100 mL | DRE | D | [37] | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 10 mg/L | S | P | [17] | Sporeformer | 100,000 MPN/100 mL | DRE | D | |

1 Medium abbreviations: RE—real effluent; S—synthetic matrix; RSW—real surface water; DRE—diluted real effluent. 2 Process abbreviations: D—disinfection; P—photolysis; PC—photocatalysis; PF—photo-Fenton; PCR—photocatalytic reduction.

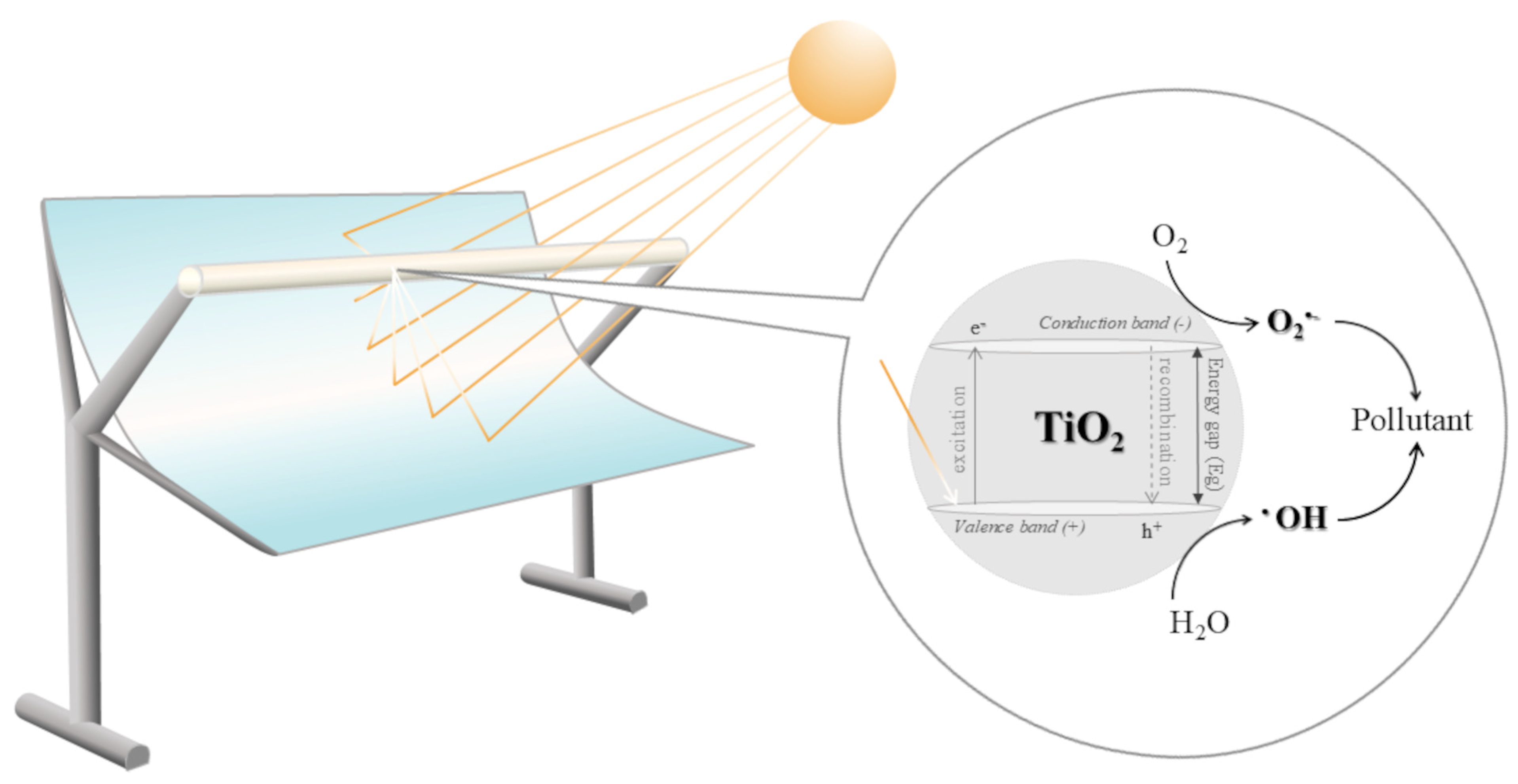

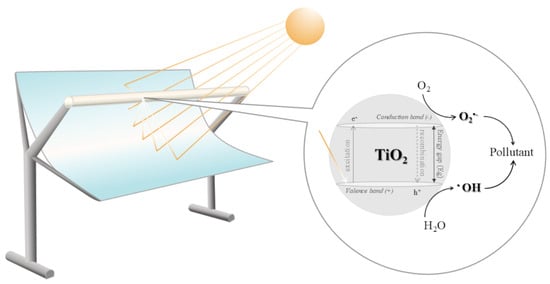

Solar photocatalysis is by far the most widely applied process, accounting for 48% of studies. TiO2 was used as the semiconductor catalyst, either in slurry or supported within the PTC receiver tube. Fixed-bed catalysts used in photocatalysis were TiO2 immobilised cement beads [53], TiO2-coated cement balls [39] and TiO2-coated silica gel beads [30]. The general reaction mechanism starts with photon excitation—TiO2 absorbs energy to promote an electron (e−) from the valence band to the conduction band, leaving a positive hole (h+). These charge carriers react in a way to produce •OH and superoxide O2•− radicals [19,34,42,54,55,56,57]. A schematic representation of solar irradiation concentration within the PTC system, together with the TiO2 photocatalytic reaction mechanism, is presented in Figure 3. Solar photo-Fenton is second-in-line (22%). In general, the combination of Fenton’s reagent, either homogeneous (FeSO4/H2O2) or heterogeneous (Fe ions supported on various materials/H2O2), with concentrated solar UV-vis light rapidly increases the •OH radicals’ production [25,31,32,34,41,49,50].

Figure 3.

Scheme of PTC-driven solar radiation concentration and TiO2 photocatalytic reaction mechanism.

Both processes were implemented to treat contaminants of emerging concern (CECs). Although pharmaceuticals and pesticides were effectively removed in selected PTC-AOP systems, it is important to note that all matrices were synthetic. Reported CEC concentrations in surface waters typically range from ng/L to µg/L globally [58]. In contrast, Table 3 shows significantly higher initial concentrations used in PTC experiments, from 10 mg/L [17,30] to over 1000 mg/L [32]. Photocatalysis and photo-Fenton demonstrated strong potential for mineralising antibiotics and pesticides [25,32,39,53]. Interestingly, H2O2-photolysis of the Ciprofloxacin achieved 88% degradation but only 8% mineralisation. This discrepancy is likely related to structural changes that eliminate UV-vis absorption peaks, suggesting molecular transformation and inactivation rather than complete mineralisation [17]. In the reviewed studies, photo-Fenton systems generally operated under acidic conditions (around pH 3), whereas TiO2-photocatalysis was performed between pH 5 and 10, implying the need for an additional neutralisation step.

Photocatalytic reduction was examined in three studies. Typically, an organic additive such as citric acid is added as a hole (h+) scavenger to facilitate the reductive pathway [47,48]. Treating mixed WW streams using simultaneous oxidative–reductive photocatalysis represents an innovative approach in which organic pollutants act as hole scavengers (being oxidised), while metals are reduced by photogenerated electrons [44]. However, metal deposition onto the catalyst surface remains a major limitation, making regeneration necessary to improve catalyst reusability.

In summary, this section presented the broad application base of PTC-AOP systems for diverse WW challenges. However, the initial pollutant concentration remains a critical factor governing reaction kinetics. High pollutant loads can saturate catalyst active sites and absorb photons, thus limiting catalyst activation. In such cases, adding an oxidant can help maintain radical generation and process efficiency. Catalyst dosage and configuration also play important roles. Immobilised catalysts eliminate the need for post-treatment filtration, although they usually require longer reaction times compared with slurry systems. WW pH is another crucial process parameter. The following section provides insights into how PTC configuration influences overall treatment performance.

3.2. PTC Design and Optical Performance

The engineering design of PTC systems reported in the selected 25 studies shows considerable variability, with 20 PTC configurations identified. Four of these reactors were presented in more than one publication, while the remaining designs were unique. Several adaptations were observed: (1) collectors connected in series to increase the effective irradiated volume [25,32,33,35,46,49], (2) integrated supplementary UV light sources to enhance photochemical activation under low-irradiance conditions [20,30], (3) hybrid configurations such as a sunlight-adjustable parabola [30] and rotary PTC [46], and (4) PTC-coupled systems with pretreatment filters [43] and a moving-bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) [42]. Diversity among PTC systems reflects ongoing efforts to optimise operational and technological objectives for various water matrices.

3.2.1. PTC Receiver Design

Receiver tubes are a critical component influencing optical performance, thermal stability and overall treatment efficiency. Their characteristics (materials, dimensions and volume) are summarised in Table 4. Among the twenty PTC systems, borosilicate (seven reactors) and ordinary glass tubes (six reactors) were the most employed receiver materials, due to their optical transparency, chemical resistance and relative affordability. Quartz receivers were used less frequently due to their high cost, despite offering superior UV transmittance. Pyrex glass tubes were used in a limited number of systems, and one study employed PET bottles as an extremely low-cost alternative [50]. Two PTC systems were equipped with multiple receivers [30,42], enabling larger irradiated volumes without enlarging the parabola aperture area and overall footprint. Reported tube diameters generally ranged from 2 to 6 cm, thus allowing efficient photon absorption while minimising “dark zones”, especially for slurry photocatalysis, where turbidity can restrict light transmission. Receiver length varied substantially (38–380 cm), which, together with diameter, contributed to the relatively low irradiated volumes (0.11–4.50 L). PTC systems with irradiated volumes below 1 L can be regarded as laboratory-scale, while those above are closer to pilot-scale operation.

Table 4.

PTC system characteristics—receiver.

To ensure optimal mass transfer in heterogeneous treatment systems, the flow rate is a decisive operational parameter that dictates the fluid regime inside the receiver tube. Generally, increasing the flow rate raises the Reynolds number (turbulence), which enhances the mixing between the WW, catalyst and/or oxidant, while eliminating possible sedimentation [35,46]. Also, higher flow rates can help moderate the temperature rise generated by the concentrating effect of PTC. On the other hand, excessive flow rates may influence low absorption of solar irradiance by the catalyst, resulting in insufficient generation of •OH radicals [39]. Additionally, to explore the optical behaviour and hydrodynamics of PTC systems, the recirculation number (defined as the ratio of the total treated volume to irradiated volume) was determined. This parameter illustrates how many times the WW must pass through the irradiated zone. Most PTC systems treated relatively small influent volumes (<5 L), resulting in moderate recirculation. In contrast, PTC system 10 [37], required notably higher recirculation due to its much larger treated volume (100 L). The presented differences highlight the receiver design and system scale on mass transfer, photon distribution and consequently treatment efficiency.

3.2.2. PTC Parabola Design

The second essential component of the PTC system is the parabola, which defines the energy intensity and determines the system’s ability to operate under varying solar conditions (Table 5). Aluminium variants (polished or anodised) were the predominant reflective materials used across the reviewed studies, offering a good compromise between high reflectivity and resistance to oxidation [59]. Also, they are low-weight and cost-effective. Several studies employed steel sheets or galvanised steel (PTC systems 3, 5, 11 and 17), which provide a cheaper and more structurally robust alternative to high-grade aluminium. Newly applied glass mirrors [43] and flexible mirrors [30] highlight the attempts to reduce manufacturing costs and maximise reflectivity.

Table 5.

PTC system characteristics—parabola.

Where available, parabola dimensions (aperture length and width) were extracted to calculate PTC aperture area and concentration ratio. These parameters are essential for optical performance evaluation. Once again, great variability is detected across PTC systems. The CR varies from 1.1 (PTC 3) to nearly 20 (PTC 5 and 11). When compared to non-concentrating systems, PTC with CR < 5 can capture more irradiance without high temperature generation, while systems with CR > 10 focus intense energy onto the receiver, which may be beneficial for thermal-synergistic processes (like microbial pathogens pasteurisation), but the risk of overheating must be managed [59]. To further complement reported data, photon utilisation (PU) was calculated based on the ratio of aperture area and irradiated volume of WW. In contrast, the commonly used accumulated UV dose (QUV), applied mainly in stationary systems such as CPC reactors, does not account for the CR and, therefore, neglects the effect of optical concentration. Consequently, PU represents a normalised metric that reflects the efficiency of solar-irradiance delivery to the reaction medium. PTC system 11 [31,45] showed the highest value (8.37), indicating a very large parabola aperture area for a small irradiated volume. This set-up can likely ensure rapid (single-pass) treatment, but with low throughput, or it may be particularly beneficial in regions with lower DNI.

Reported solar intensities significantly vary across the studies, probably due to inconsistencies in reporting standards rather than regional differences. Most PTC systems operated under standard DNI values between 600 and 1000 W/m2. One study reported a notably lower value (55 W/m2), which likely corresponds to UV irradiance rather than DNI [46], while another reports 2600 W/m2 [50], possibly representing concentrated UV flux that reaches the receiver. Although high radiation intensity creates a significant photon supply for radical formation, highly concentrated flux may elevate the temperature and negatively influence structural changes in the oxidant and catalyst. In this context, the recently developed sunlight-adjustable parabola [30] may offer a good solution for regions with variable DNI. To ensure effective application, a tracking mechanism is a necessary part of the PTC system. Almost half of the PTC systems employed automatic tracking, with one or two axes, whereas a significant number still rely on manual tracking or no tracking at all. The absence of a sun-tracking mechanism can greatly reduce manufacturing and operational costs, but it limits the use of PTCs to a narrow operational window (hours with the highest irradiation).

3.3. PTC-AOP System Performance

In this section, more focus is given to AOP (normalised) performance in the degradation of various contaminants. The collected data on process efficiency and mineralisation are summarised in Table 6 and grouped according to the applied treatment process (photolysis, photo-Fenton and photocatalysis). Reaction kinetics were reported in several studies, and, where possible, pseudo-first-order rate constants were calculated. While kFO provides a convenient metric for pollutant degradation, it often fails to capture the spatial non-uniformity of the radiation field within concentrating reactors. Consequently, relying solely on these values can lead to misleading comparisons across different pollutants and water matrices unless they are complemented by energy-normalised indicators. To enable comparison across different treatment processes and PTC configurations, the time required for a one-order-of-magnitude reduction (τ90) was determined. This parameter is useful for engineering design and residence time calculations. For example, electrical energy per order (EEO), which is the industry standard for artificial UV systems, is not well-suited to solar-driven AOPs, as electrical energy consumption is limited to pumping and is therefore negligible. This makes EEO an ineffective metric for evaluating PTC efficiency.

Table 6.

Performance of PTC-AOP systems applied in photolysis, photo-Fenton and photocatalysis.

Photolysis was found to be the least efficient treatment option. High τ90 values indicate slow reaction kinetics. The case of Ciprofloxacin [17] mineralisation clearly shows a significant presence of the inevitable intermediates, whose degradation is mandatory due to possible negative effects on the environment. This critical secondary effect indicates that, although optically powerful, PTC systems are more feasible in hybrid set-ups, where WW undergoes pretreatment (such as a series of filters [43] or biological treatment [42]).

When comparing the degradation of synthetic dyes, the influence of the PTC concentration ratio becomes evident (Table 5). PTC system 11 exhibited a substantially higher CR (19.3) than PTC system 1 (6.00), enabling faster •OH radical generation and improved decolourisation efficacy. Nevertheless, promising results were obtained for the real WW matrix, the textile dying effluent, where direct photolysis provided a low-cost but time-consuming option for both decolourisation and mineralisation [35]. To enhance overall photolysis efficiency, it can be suitable to implement PTC systems with high photon utilisation, such as PTC 11. Additional suitable enhancements are the optimisation of the WW matrix pH, since it may lead to oxidant scavenging reactions [60], and flow rate, to enhance WW turbulence in the PTC receiver [35].

Both heterogeneous and homogeneous photo-Fenton processes were further examined. The influence of metal active sites on •OH radical production supported faster mineralisation kinetics when compared to photolysis. Among investigated PTC-AOP systems, PTC 11 exhibited the highest CR (19.3) and photon utilisation (8.37 m2/L), but the applied clay-based catalysts showed relatively slow reaction kinetics for both dye decolourisation and mineralisation [31]. With a high CR comes the generation of heat, which may influence the self-decomposition of H2O2 into molecular O2 and H2O (>50 °C) [61], leading to lower process efficiency. Also, it is possible that the presented catalysts block some of the focused solar irradiance, leading to a longer reaction time [60]. In this case, the flow rate was the lowest among all systems (0.05 L/min; Table 2); thus, a low mass transfer rate can also be a detrimental factor for heterogeneous Fenton reaction performance. Since this PTC-AOP system has the highest photon utilisation per irradiated WW volume, its implementation in photolytic treatment (as a polishing step) could be more profitable.

Further, most photo-Fenton applications relied on homogeneous Fenton reagents (FeSO4 and H2O2) under acidic conditions (pH 3). The fastest mineralisation among the analysed studies was achieved for humic acid (~18 min) [50]. Phenol degradation was investigated in PTC system 4 [25,49], where higher pollutant loads required significantly prolonged reaction time and further optimisation of Fenton reagent ratios. Comparison between real and synthetic oil–WW matrices [25,41] indicates the need for increased oxidant dosages to effectively decompose high organic loads. Overall, τ90 values provide valuable insight into treatment performance in PTC-AOP systems and highlight the need for further optimisation of operating parameters to achieve rapid and extensive mineralisation. The (necessary) final stage of Fenton treatment is neutralisation, a step where pH is increased, residual Fe ions are precipitated, and Fe-sludge is removed. Accordingly, optimisation and neutralisation are particularly important for sustaining pilot-scale applications for treating WW volumes of 100 L or more.

Photocatalytic processes were investigated using various TiO2-based catalysts. Immobilised-TiO2-coated silica gel beads (TiO2-SGB; [30]) within PTC receiver and S-scheme graphitic carbon nitride/TiO2 composite (g-C3N4/TiO2; [33]) in slurry mode were applied for the decolourisation of Methylene Blue and Rhodamine B. Initial dye concentrations were significantly lower than those used in photolysis, the photo-Fenton process, and real textile effluents [36], resulting in lower τ90 values. From an industrial-scale perspective, it is crucial to consider competitive adsorption and reaction pathways when dye molecules are present in excess, as they compete for catalyst active sites [34]. An imbalanced ratio between pollutants, catalysts and oxidants can significantly reduce process performance.

In contrast, immobilised photocatalysts used for the degradation of CECs [30,39,53] generally exhibit slower kinetics, possibly due to mass transfer limitations. Slurry systems, on the other hand, often operate under turbulent conditions [40,53], leading to lower τ90 values, while ensuring effective pollutant–catalyst and catalyst–photon contact (highly concentrated near receiver wall). When TiO2-based photocatalysis was applied to complex WW matrices, faster reaction kinetics were observed for green-synthetised TiO2 [44] and when TiO2 was combined with H2O2 [40]. Smaller catalyst particle sizes provide a higher density of active sites, leading to improved process performance.

Although not shown in the table, PTC-driven WW disinfection can be supported by PTC-AOP systems with high potential in heat generation (CR > 10). The synergistic effect of solar irradiation and water temperature can lead to solar pasteurisation of highly resistant microorganisms [38]. This optical–thermal synergy enables chemical-free disinfection, highlighting a critical functional advantage of PTCs over CPC-based systems.

4. Future Perspectives

The transition of PTC-driven AOPs from laboratory-scale to industrial and/or municipal applications requires addressing several critical technical and economic barriers. Future research should prioritise the following, in order to strengthen the viability of CSP technologies:

- Sludge management (homogeneous Fenton process) and catalyst recovery (heterogeneous Fenton process and photocatalysis)—The generation of Fe-rich sludge after Fenton reactions remains a significant operational challenge. Future studies should incorporate sludge management strategies, such as the development of heterogeneous catalysts to minimise secondary-waste generation. Also, greater attention should be given to catalyst recovery, reusability and regeneration.

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA)—Currently, both LCA and TEA are underrepresented in the PTC-AOP literature. The feasibility of PTC systems depends on balancing the high initial capital cost (precision sun-tracking mechanisms and reflective parabola materials) and land footprint requirements with long-term reductions in operational cost through renewable solar energy incorporation. These assessments should quantify the environmental trade-offs between chemical savings and the energy-intensive manufacturing of concentrator components.

- Scaling up of PTC-AOP technology—Most of the existing literature relies on laboratory or pilot conditions; thus, future work should address industrial-scale implementation. Hybrid configurations, where PTC can excel in polishing of recalcitrant pollutants and serve as a tertiary/quaternary stage, could be integrated into existing infrastructure (municipal WW treatment plants) or developed as standalone systems with automated control systems (adjustment of incident angle, flow rate, catalyst/oxidant dosage) to ensure consistent effluent treatment in real time.

5. Conclusions

This mini-review synthesised the performance of PTC-driven AOPs for WW treatment, leading to the following key findings:

- Superior optical performance—PTC systems demonstrate a clear advantage over stationary and non-concentrating reactors for the treatment of toxic and persistent pollutants and concentrated effluents. The high concentration ratio can facilitate improved and accelerated reaction kinetics with rapid •OH radical production, leading to a shorter treatment time.

- Necessity of standardised metrics—The systematic analysis revealed that the use of normalised performance indicators, like the time required for a one-order-of-magnitude reduction (τ90; min) and photon utilisation (PU; m2/L), is necessary for assessing treatment efficiency across diverse geographical locations and reactor designs.

- Climate and water resilience—Analytical mapping confirms that PTC-driven technologies are most viable in DNI hotspots. As climate change expands areas affected by severe water scarcity and elevated solar potential, like the Mediterranean and Balkan regions, PTC-AOPs may present a solution for safe WW treatment and reuse, contributing to the circularity and SDG6 targets.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14030510/s1. An Excel file compiling all extracted experimental data and derived parameters used for the comparative analysis in this study is available.

Author Contributions

A.K.M. Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing—original draft; G.P.M. Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing—original draft; M.B.-T. Supervision, Writing—review and editing; A.L.M. Writing—review and editing; N.S. Data curation, Writing—review and editing; N.D. Data curation, Writing—review and editing; Đ.K. Funding acquisition; Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme, Horizon Europe—Work Programme 2021–2022 Widening participation and strengthening the European Research Area, HORIZON-WIDERA-2021-ACCESS-02, under grant agreement No [101060110], SmartWaterTwin.

Data Availability Statement

All analysed data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kitzmann, N.H.; Caesar, L.; Sakschewski, B.; Rockström, J. Planetary Health Check 2025; Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK): Potsdam, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Arias, P., Bustamante, M., Elgizouli, I., Flato, G., Howden, M., Méndez-Vallejo, C., Pereira, J.J., Pichs-Madruga, R., Rose, S.K., Saheb, Y., et al., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2025—Mountains and Glaciers: Water Towers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2025; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat; WHO. Progress on the Proportion of Domestic and Industrial Wastewater Flows Safely Treated—Mid-Term Status of SDG Indicator 6.3.1 and Acceleration Needs, with a Special Focus on Climate Change, Wastewater Reuse and Health; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Arzate, S.; Pfister, S.; Oberschelp, C.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.A. Environmental Impacts of an Advanced Oxidation Process as Tertiary Treatment in a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Cardenas, J.A.; Esteban-García, B.; Agüera, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Wastewater Treatment by Advanced Oxidation Process and Their Worldwide Research Trends. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, A.K.; Ayele, D.W.; Teshager, M.A.; Omar, M.; Yerkrang, P.P.; Elgaddafi, R.; Alemu, M.A. Recent Advances in Wastewater Treatment Technologies: Innovations and New Insights. Energy Rev. 2025, 4, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Ruotolo, L.A.M. Critical Review of Fenton and Photo-Fenton Wastewater Treatment Processes over the Last Two Decades. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 13995–14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyam, S.; Patra, S. The Evolving Landscape of Advanced Oxidation Processes in Wastewater Treatment: Challenges and Recent Innovations. Processes 2025, 13, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervolino, G.; Zammit, I.; Vaiano, V.; Rizzo, L. Limitations and Prospects for Wastewater Treatment by UV and Visible-Light-Active Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: A Critical Review. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020, 378, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Mata, A.G.; Velazquez-Martínez, S.; Álvarez-Gallegos, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Hernández-Pérez, J.A.; Ghanbari, F.; Silva-Martínez, S. Recent Overview of Solar Photocatalysis and Solar Photo-Fenton Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Photoenergy 2017, 2017, 8528063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaim, M.A.; Alwasiti, A.A.; Shnain, Z.Y. The Photocatalytic Process in the Treatment of Polluted Water. Chem. Pap. 2023, 77, 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahtasham Iqbal, M.; Akram, S.; Khalid, S.; Lal, B.; Hassan, S.U.; Ashraf, R.; Kezembayeva, G.; Mushtaq, M.; Chinibayeva, N.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Advanced Photocatalysis as a Viable and Sustainable Wastewater Treatment Process: A Comprehensive Review. Environ. Res. 2024, 253, 118947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, E.; Domingues, E.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M.; Leitão, A.; Martins, R.C. Solar Photo-Fenton and Persulphate-Based Processes for Landfill Leachate Treatment: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, N.; An, G. Review of Concentrated Solar Power Technology Applications in Photocatalytic Water Purification and Energy Conversion: Overview, Challenges and Future Directions. Energies 2024, 17, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Xu, J.; Shen, B. A Mini-Review of Recent Progress in Zeolite-Based Catalysts for Photocatalytic or Photothermal Environmental Pollutant Treatment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Golli, A.; Fendrich, M.; Bajpai, O.P.; Bettonte, M.; Edebali, S.; Orlandi, M.; Miotello, A. Parabolic Trough Concentrator Design, Characterization, and Application: Solar Wastewater Purification Targeting Textile Industry Dyes and Pharmaceuticals—Techno-Economic Study. EuroMediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato, S.; Blanco, J.; Alarcón, D.C.; Maldonado, M.I.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Gernjak, W. Photocatalytic Decontamination and Disinfection of Water with Solar Collectors. Catal. Today 2007, 122, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sivakumar, M.; Yang, S.; Enever, K.; Ramezanianpour, M. Application of Solar Energy in Water Treatment Processes: A Review. Desalination 2018, 428, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sómer, M.; Moreno-SanSegundo, J.; Álvarez-Fernández, C.; van Grieken, R.; Marugán, J. High-Performance Low-Cost Solar Collectors for Water Treatment Fabricated with Recycled Materials, Open-Source Hardware and 3d-Printing Technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira Andrade Queiroz, B.; Sabara, G.; Alvim, B.; Queiroz, A.; Leão, D.; Maria, M.; Amorim, C.; Teixeira Andrade Queiroz, M.; Godoy Sabara, M.; Barbosa Alvim, L.; et al. A Brief Review on the Importance Use of Solar Energy in the Treatment of Recalcitrant Effluents Applying Advanced Oxidation Processes. Ciência Nat. 2015, 37, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendrich, M.A.; Quaranta, A.; Orlandi, M.; Bettonte, M.; Miotello, A. Solar Concentration for Wastewaters Remediation: A Review of Materials and Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, S.; López, M.I.P.; Spuhler, D.; Pérez, J.A.S.; Ibáñez, P.F.; Pulgarin, C. Solar Disinfection Is an Augmentable, in Situ-Generated Photo-Fenton Reaction-Part 2: A Review of the Applications for Drinking Water and Wastewater Disinfection. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 198, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliyal, P.S.; Mondal, S. Parabolic Solar Collectors for Sustainable Water Treatment: A Review of Applications, Advancements and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 49, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.A.O.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Guardani, R.; Quina, F.H.; Chiavone-Filho, O.; Braun, A.M. Industrial Wastewater Treatment by Photochemical Processes Based on Solar Energy. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 2007, 129, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESMAP. Global Solar Atlas 2.0 Technical Report. 170-14/2019; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- C3S; WMO. European State of the Climate 2024; World Meteorological Organization (WMO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, J.R.; Bircher, K.G.; Tumas, W.; Tolman, C.A. Figures-of-Merit for the Technical Development and Application of Advanced Oxidation Technologies for both Electric-and Solar-Driven Systems † (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhrieh, A.H.; Alamir, A.I.; Hindiyeh, M.Y. Water Disinfection Using CSP Technology. 2016. Volume 11. Available online: https://www.ripublication.com/Volume/ijaerv11n15.htm (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Zhang, C.; An, G.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, G.; Yang, Y. Development of a Sunlight Adjustable Parabolic Trough Reactor for 24-Hour Efficient Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucar Milidrag, G.; Prica, M.; Kerkez, D.; Dalmacija, B.; Kulic, A.; Tomasevic Pilipovic, D.; Becelic Tomin, M. A Comparative Study of the Decolorization Capacity of the Solar-Assisted Fenton Process Using Ferrioxalate and Al, Fe-Bentonite Catalysts in a Parabolic Trough Reactor. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 93, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Borges, T.; Chiavone-Filho, O.; Carlos Silva Costa Teixeira, A.; Luiz Foletto, E.; Luiz Dotto, G.; Augusto Oller do Nascimento, C. Degradation of Thiophanate-Methyl Fungicide by Photo-Fenton Process Using Lab-Scale Annular and Solar Tubular Reactors. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2019, 22, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, M.H.; Sabzehmeidani, M.M.; Ghaedi, M.; Avargani, V.M.; Moradi, Z.; Roy, V.A.L.; Heidari, H. S-Scheme Heterojunction g-C3N4/TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity for Degradation of a Binary Mixture of Cationic Dyes Using Solar Parabolic Trough Reactor. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 174, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic Dye Degradation from Textile Wastewater: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21751–21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majhi, P.K.; Azam, R.; Kothari, R.; Arora, N.K.; Tyagi, V.V. Impact of Flow Rate in Integration with Solar Radiation on Color and COD Removal in Dye Contaminated Textile Industry Wastewater: Optimization Study. Energy Eng. 2022, 119, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, A.M.S.; Athira, K.K.; Alves, M.B.; Gardas, R.L.; Pereira, J.F.B. Textile Dyes Effluents: A Current Scenario and the Use of Aqueous Biphasic Systems for the Recovery of Dyes. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 55, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Dayem, A.M.; El-Ghetany, H.H.; El-Taweel, G.E.; Kamel, M.M. Thermal Performance and Biological Evaluation of Solar Water Disinfection Systems Using Parabolic Trough Collectors. Desalin. Water Treat. 2011, 36, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaúque, B.J.M.; Jankoski, P.R.; Doyle, R.L.; Da Motta, A.S.; Benetti, A.D.; Rott, M.B. Pilot Scale Continuous-Flow Solar Water Disinfection System by Heating and Ultraviolet Radiation Inactivating Acanthamoeba Cysts and Bacillus Spores. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, S.; Bansal, P. Assessment of Solar Photocatalytic Degradation and Mineralization of Amoxicillin Trihydrate (AMT) Using Slurry and Fixed-Bed Batch Reactor: Efficacy of Parabolic Trough Collector. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 36109–36117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Chaudhary, R.; Gandhi, K. Preliminary Study on Optimization of PH, Oxidant and Catalyst Dose for High COD Content: Solar Parabolic Trough Collector. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2013, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M.A.; Tayeb, A.M. Pre-Treatment of Olive Oil Mill Wastewaters Based on Solar Management Techniques: An Integrated Rational Approach. Eng. Res. J. 2015, 38, 65–71. Available online: https://journals.ekb.eg/article_66778_45166c33b716a0ab2050e5f5493cbd58.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Barwal, A.; Chaudhary, R. Feasibility Study for the Treatment of Municipal Wastewater by Using a Hybrid Bio-Solar Process. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 177, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Awady, M.H.; El-Ghetany, H. Experimental Investigation of An Industrial Wastewater Treatment Unit Using Multi Filter Hybrid with Parabolic Trough Solar Concentrator. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, S.P.; Saxena, G.; Singh, V.; Yadav, A.K.; Bharagava, R.N.; Thapa, K.B. Green Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles Using Leaf Extract of Jatropha curcas L. for Photocatalytic Degradation of Tannery Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 336, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucar Milidrag, G.; Nikić, J.; Gvoić, V.; Kulić Mandić, A.; Agbaba, J.; Bečelić-Tomin, M.; Kerkez, D. Photocatalytic Degradation of Magenta Effluent Using Magnetite Doped TiO2 in Solar Parabolic Trough Concentrator. Catalysts 2022, 12, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Munõz, O.; Tirado-Ballestas, I.; Lopez, A.L.B.; Colina-Marquez, J. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Pilot Plant for Cyanide Decontamination: A Novel Solar Rotary Photoreactor. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 2022, 144, 051005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, K.; Chaudhary, R.; Sawhney, R.L. Photocatalytic Reduction of Cr(VI) in Aqueous Titania Suspensions Exposed to Concentrated Solar Radiation. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2007, 26, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, K.; Chaudhary, R.; Sawhney, R.L. Effect of PH on Solar Photocatalytic Reduction and Deposition of Cu(II), Ni(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II): Speciation Modeling and Reaction Kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, I.B.S.; Moraes, J.E.F.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Guardani, R.; Nascimento, C.A.O. Photo-Fenton Degradation of Wastewater Containing Organic Compounds in Solar Reactors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2004, 34, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, S.A.; Afsharnia, M.; Azrah, K.; Javan, N.S.; Biglari, H. Humic Acid Degradation via Solar Photo-Fenton Process in Aqueous Environment. Iran. J. Health 2015, 2, 304–312. Available online: http://www.ijhse.ir/index.php/IJHSE/article/download/88/pdf_38 (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Bandala, E.R.; Arancibia-Bulnes, C.A.; Orozco, S.L.; Estrada, C.A. Solar Photoreactors Comparison Based on Oxalic Acid Photocatalytic Degradation. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Gondal, M.A.; Sheikh, A.K. Comparative Study of Different Solar-Based Photo Catalytic Reactors for Disinfection of Contaminated Water. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Tejo Prakash, N.; Toor, A.P.; Bansal, P.; Sangal, V.K.; Kumar, A. Concentrating and Nonconcentrating Slurry and Fixed-Bed Solar Reactors for the Degradation of Herbicide Isoproturon. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 2018, 140, 021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, Z.; Mirghaffari, N.; Alemrajabi, A.A.; Davar, F.; Soleimani, M. Adsorption and Photocatalytic Removal of SO2 Using Natural and Synthetic Zeolites-Supported TiO2 in a Solar Parabolic Trough Collector. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.F.; Ebrahim, M.; Nafi, O.; Hussain, L.; Maneual, N.; Sameer, A. Designing and Operating a Pilot Plant for Purification of Industrial Wastewater from Toxic Organic Compounds by Utilizing Solar Energy. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 31, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaruma-Arias, P.E.; Núñez-Núñez, C.M.; González-Burciaga, L.A.; Proal-Nájera, J.B. Solar Heterogenous Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylthionine Chloride on a Flat Plate Reactor: Effect of PH and H2O2 Addition. Catalysts 2022, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chen, J.; Ateia, M.; Cates, E.L.; Johnson, M.S. Do Gas Nanobubbles Enhance Aqueous Photocatalysis? Experiment and Analysis of Mechanism. Catalysts 2021, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Deng, Y.; Yang, F.; Miao, Q.; Ngien, S.K. Systematic Review of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs): Distribution, Risks, and Implications for Water Quality and Health. Water 2023, 15, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagle-Salazar, P.D.; Nigam, K.D.P.; Rivera-Solorio, C.I. Parabolic Trough Solar Collectors: A General Overview of Technology, Industrial Applications, Energy Market, Modeling, and Standards. Green Process. Synth. 2020, 9, 595–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisuzzaman, S.M.; Joseph, C.G.; Pang, C.K.; Affandi, N.A.; Maruja, S.N.; Vijayan, V. Current Trends in the Utilization of Photolysis and Photocatalysis Treatment Processes for the Remediation of Dye Wastewater: A Short Review. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouaissa, Y.A.; Madi, N.E.H.; Chabani, M.; Bouafia-Chergui, S. Solar Advanced Oxidation Processes for Refinery Wastewater Treatment: Comparative Efficiencies, Modeling, and Feasibility for Cooling Tower Reuse. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.