Abstract

As a cutting-edge technology in the field of cement-based materials, early carbonation curing enables industrial carbon sequestration and functional modification, and the optimization of process parameters is the key to advancing the development of this technology. This paper reviews the mechanism of action and influencing factors of early carbonation curing (including moisture content, carbon dioxide concentration, pre-hydration degree, etc.), its effects on the mechanical properties and durability of materials, as well as the resulting changes in microstructure. Meanwhile, this review also covers content such as the hydration–carbonation coupling mechanism, mentions the relevant conditions of carbonation products and microstructure, analyzes the performance enhancement of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), and provides relevant support for the low-carbon development of cement-based materials by combining the application practice of prefabricated components and the comparison of technical routes. Although early carbonation can significantly improve material properties and optimize microstructure, current research still has shortcomings: the exploration of mineral carbonation–hydration activity, microstructure evolution law, and product combination mechanism is relatively insufficient, and the understanding of carbonation–hydration coupling kinetics is still not in-depth enough, all of which are areas requiring further research in the future.

1. Introduction

A series of issues caused by global warming have led to extensive research in the construction industry on energy conservation, emissions reduction, and sustainable concrete materials [1,2]. During the material production phase, carbon emissions are reduced through methods such as carbon capture, reuse, and sequestration or landfill disposal [3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, technological limitations have resulted in significant disparities in emission reduction achievements across many countries, with high costs and low utilization rates remaining prevalent challenges. Consequently, large-scale, low-cost artificial sequestration for effective CO2 capture holds immense application value [9].

Calcium, magnesium, and other alkali metal oxides, hydroxides, and silicates can thermodynamically react with CO2 to form corresponding carbonates while releasing substantial heat. This reaction is commonly termed “carbonation” in engineering practice. However, the descriptor “carbonation” appears chemically misleading when considering the reaction products (carbonate formation). For clarity and convention, this terminology has been widely adopted in the civil engineering industry to denote the reaction process [10,11]. Early-age carbonation curing (carbonation hardening) fundamentally differs from natural carbonation [11]. Natural carbonation of concrete typically adversely affects structural integrity, often leading to steel reinforcement corrosion, expansion-induced cracking, and compromised structural stability [12]. In early-age carbonation hardening, CO2 reacts with unhydrated calcium-bearing minerals through a multi-stage mechanism, forming carbonates and cementitious hydrates that enhance material densification and performance [13,14]. By contrast, natural carbonation is a slow, long-term process occurring spontaneously over time, whereas early-age carbonation hardening is applied immediately after concrete pouring or demolding. This approach significantly overcomes the limitations of traditional cement-based materials in harsh and extreme conditions [15].

With increasing demands on the durability and mechanical properties of construction materials in service environments, researchers worldwide have extensively investigated the feasibility of early-age carbonation curing for concrete. Hu [16] utilized CO2 carbonation curing to refine the pore structure of solid-waste lightweight concrete, increasing the solid volume within the cementitious matrix by 11.4% and enhancing strength by 33%. Sharma and Goyal [17] demonstrated that early-age carbonation hardening of cement-based materials also exhibits significant carbon sequestration effects, with carbonation efficiency correlating with CaO content. Furthermore, carbonation curing has been applied to prefabricated plain concrete and prestressed reinforced concrete elements. The energy consumption for early carbonation curing of standard concrete blocks is approximately 500 kJ per unit—merely 20% of that required for autoclave curing [18]. Rapid industrial development and technological advancements provide essential foundations for achieving carbon neutrality and peak carbon emissions.

Despite exponential growth in “carbonation” and “carbon curing” research over the past decade, along with various technological implementations, early-age carbonation hardening remains a complex reaction process [19]. The underlying mechanisms governing efficiency limitations—such as high costs and low utilization rates—remain inadequately explored, with these persistent challenges yet unresolved [20]. Concurrently, the long-term impact of early-age carbonation curing (carbonation hardening) on cement-based materials’ durability, particularly its mechanistic effects on steel corrosion, remains unclear, posing significant obstacles to large-scale adoption. This paper introduces the fundamental principles of early-age carbonation curing technology, systematically analyzing influencing factors including moisture content, CO2 concentration, temperature, pressure, curing duration, and pre-hydration time. It further examines carbonation curing’s effects on durability enhancement, mechanical property improvement, and microstructural evolution in cementitious systems. Finally, we summarize existing limitations and provide insights to guide future research and development in early-age carbonation hardening.

2. Principles of Early-Age Carbonation Curing

2.1. Reaction Mechanism of CO2 Carbonation

In fresh concrete, accelerated carbonation is simulated by exposing the material to CO2 concentrations hundreds of times higher than ambient levels. Under these conditions, CO2 dissolves into the aqueous phase of the cementitious system and reacts with water according to Equation (1) to form carbonic acid solution [21]. This carbonic acid solution subsequently undergoes hydrolysis and dissociation, decomposing via Equations (2) and (3)—a process influenced by external factors such as gas pressure and temperature, with Equation (2) predominating:

2.2. Carbonation Reaction Process

Researchers have observed that carbonation accelerates the hydration reaction of cement clinker phases in fresh concrete [22]. It is hypothesized that the accelerated carbonation process rapidly consumes hydration products, thereby promoting further hydration. Carbonation constitutes a physicochemical reaction between cement and gaseous CO2 under aqueous conditions. Specifically, it involves the carbonation of calcium silicates and their hydration products. In the initial stage, calcium silicates primarily in the form of tricalcium silicate (3CaO·SiO2, C3S) and dicalcium silicate (2CaO·SiO2, C2S) react with CO2 in the presence of water to form calcium silicate hydrate (xCaO·SiO2·yH2O, C-S-H) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3). This reaction is predominantly controlled by CO2 diffusion rates, which depend on CO2 concentration and pressure during carbonation [23]. The exothermic reactions are represented by Equations (4) and (5) [24,25]. Studies indicate that calcium silicates (C3S, β-C2S, γ-C2S) do not fully react, with the final products being C-S-H (or low-calcium-modified silica gel) and CaCO3. The resulting calcium carbonate transforms from amorphous nanoparticles into crystalline forms, accumulating as lamellar stacks on calcium silicate surfaces to refine pore structures [26,27].

Current research primarily focuses on carbonation of hydratable phases (C3S, β-C2S) in Portland cement, while studies on non-hydraulic minerals like γ-C2S, C3S2, and CS under ambient conditions remain limited [28,29]. Hydration products (e.g., calcium hydroxide, C-S-H, ettringite) also participate in carbonation, forming calcium carbonate, gypsum, and aluminum hydrates. The nomenclature for amorphous silica gel—a carbonation product—remains debated, with terms including C-S-H gel [30,31], amorphous calcium silicate hydrocarbonate [32], polymerized silicate [33], and Ca-modified silica gel [34]. Despite terminological variations, its amorphous cementitious nature is widely accepted.

Regarding implementation methods of carbonation processes, researchers have proposed various approaches including direct carbonation [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], carbonate solution carbonation [46,47], and microbial-carbonation synergistic treatment [48]. Direct carbonation involves injecting CO2 directly into cementitious materials to react with alkaline components (e.g., calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or hydration products (e.g., calcium silicate hydrate, C-S-H), forming stable calcium carbonate (CaCO3) precipitates. For instance, pre-carbonation introduces CO2 during concrete mixing. While enhancing compressive strength, this method exhibits limited carbon sequestration capacity due to low CO2 dosage and short injection duration [35,36,37]. Accelerated carbonation technology controls environmental conditions (CO2 purity, temperature, humidity, duration, and pressure), significantly improving carbonation rates while enhancing concrete’s mechanical properties and durability [16,38,41]. One common method places concrete specimens in controlled chambers with specific CO2 concentrations and optimized relative humidity to accelerate carbonation; this typically requires weeks or months to achieve millimeter-scale carbonation depth depending on CO2 concentration. Alternatively, high-pressure gradient methods achieve complete carbonation within hours or minutes, though potentially causing specimen damage through microcracks and heat generation (exothermic reactions) [38,39,40,45]. Carbonate solution carbonation bypasses atmospheric CO2 capture by introducing solutions (e.g., NaHCO3) into cementitious materials, promoting reactions between CO2 and alkaline ions to form CaCO3 precipitates. This milder approach requires no complex equipment or extreme conditions, making it suitable for long-term carbonation scenarios [41]. Studies indicate concrete exposed to high-concentration carbonate solutions carbonates faster than in ambient air, with increasing acceleration at higher concentrations due to reduced rate-limiting effects of CO2 dissolution [42]. Microbial-carbonation synergistic treatment utilizes microbially derived carbonic anhydrase to catalyze reactions between CO2 and alkaline components, accelerating carbonate precipitation. For example, in steel slag modification studies [43], microbial activity promotes CaCO3 crystal formation, which serve as nucleation sites for silicate growth, significantly enhancing early hydration capacity of cementitious materials. This approach also improves dissolution and phase transformation of expansive components in steel slag, further enhancing mechanical properties. While increasing carbonation efficiency with lower energy consumption and environmental impact, high costs limit large-scale application.

2.3. Carbonation Products

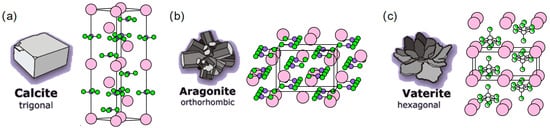

The formation of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) is a key factor contributing to the early-age strength development of cementitious materials. Its precipitation and accumulation patterns significantly refine pore structures and enhance the impermeability of cement paste [44]. During the early carbonation curing process, the first substance typically formed is hydrated amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC). Subsequently, it may dehydrate to form anhydrous calcium carbonate, which exists in three crystal forms: calcite, aragonite, and vaterite [46,47]. Their crystalline structures are illustrated in Figure 1. Calcite constitutes the stable phase, decomposing between 820 °C and 1000 °C. The other two metastable polymorphs decompose at 550–820 °C, undergoing phase transformation to stable calcite under elevated temperatures or prolonged durations [19,49]. It generally follows the phase transformation path of ACC → vaterite → aragonite → calcite.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of calcium carbonate [19,46,48]: (a) calcite; (b) aragonite; (c) vaterite (ball aragonite).

In early carbonation curing, calcite dominates due to high calcium ion concentrations favoring its formation. The prevalence of other polymorphs depends on aragonite–vaterite conversion rates, which can be modulated by CO2 concentration, reaction time, and temperature to meet specific objectives [50,51]. Liu et al. [52] demonstrated that ACC remains relatively stable during initial carbonation, but after 24 h of carbonation curing, increased formation of aragonite and vaterite reduces the proportion of ACC. Xue et al. [53] observed that prolonged hydration time elevates calcium carbonate content while concurrently increasing calcium hydroxide concentration. Lu et al. [54] and Lai et al. [55] established that calcium carbonate crystallization patterns correlate with CO2 concentration and curing pressure, noting that high-pressure CO2 conditions promote rapid formation of polyhedral elongated calcite crystals. Industrial production achieves carbon sequestration while mass-producing precast components through controlled carbonation processes. However, current applications remain largely limited to precast elements due to technical challenges in achieving sufficient carbonation depth in large-scale structural members [12,19]. Maturation of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies, coupled with optimized industrial chains, has reduced production costs, facilitating global scalability to advance energy conservation and emission reduction goals [26,47].

Early-stage carbonation products exert a dual impact on material performance. ACC initially enhances densification by pore filling, yet its low mechanical strength and tendency to transform into crystalline phases at ambient temperatures compromise long-term stability, potentially causing performance degradation [54,56,57,58]. However, ACC’s cluster-like morphology imparts superior plasticity and crack resistance, potentially improving material toughness. Conversely, crystalline phases like calcite significantly elevate compressive strength and stiffness. For instance, β-C2S carbonated under 99.9% CO2 for 6 h achieved 85.7 MPa strength, primarily attributed to calcite formation. Excessive calcite, however, may cause microstructural loosening and strength reduction [59]. Additionally, calcite formation often accompanies decalcification and dissolution of hydration products (e.g., C-S-H gel), further affecting mechanical properties. Strategic modulation of early carbonation product types and quantities is therefore critical for performance optimization.

3. Early-Age Carbonation Curing Process and Influencing Factors

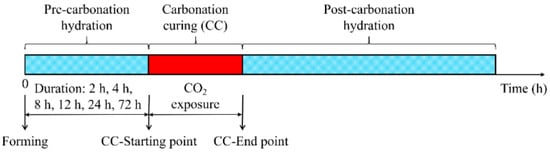

Carbonation curing typically comprises three stages: pre-curing (hydration curing), carbonation curing (hardening curing), and post-curing (Figure 2) [60]. Pre-curing occurs between specimen casting and CO2 exposure, controlling initial water content and pore structure, which critically influences subsequent carbonation. Some studies implement post-demolding air-blowing at 1 m/s to ensure uniform moisture dispersion loss and enhance CO2 penetration pathways [61]. The second stage involves placing specimens in carbonation chambers under high-concentration CO2 at optimized conditions. Post-curing replenishes moisture to sustain hydration reactions in the cement system [59,62]. Key influencing factors include initial water content (IWC), carbonation duration, CO2 concentration, temperature, and pressure.

Figure 2.

Early-age carbonation curing regime of specimen [60].

3.1. Moisture Content

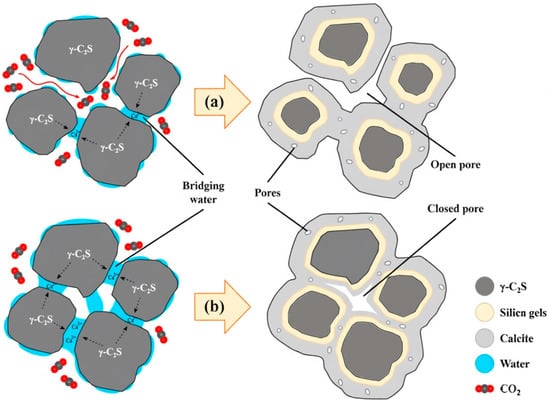

Water is an essential medium for carbonation reactions during early-age curing. Insufficient moisture impedes carbonation progress, while excessive water obstructs CO2 diffusion pathways. As a critical reaction medium for dissolving hydration products and carbonate crystallization, optimal moisture sustains ionic activity in alkaline pore solutions to accelerate carbonation. Water also enhances CO2 adsorption and diffusion through water-bridge formation, promoting carbonation reactions [63] (Figure 3). When moisture content exceeds the critical saturation threshold, excess free water molecules block pore networks and gas transport channels while reducing Ca2+ ion mobility in the liquid phase, thereby suppressing carbonation rates through coupled mechanisms of mass transfer resistance and ion diffusion inhibition.

Figure 3.

Carbonation cementation mechanism of steel slag particles with (a) <7% water content; (b) >7% water content [63].

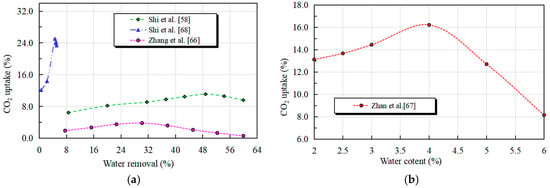

During pre-curing, free water removal from pores is achieved by adjusting curing temperature and enhancing convective air dehydration [64], regulating specimen moisture content to accelerate gas diffusion during carbonation. Higher dehydration rates promote CO2 absorption until water loss reaches ~40%, where absorption plateaus [65]. Zhang and Shao [66], Zhan et al. [67], and Shi et al. [68] determined optimal moisture content as ~4.5% at 0.5 water-to-binder ratio, and optimal dehydration rate as 40% at 0.3–0.4 water-to-binder ratio (Figure 4). Optimal values vary with concrete type (fresh/recycled) and aggregate characteristics due to their influence on cement matrix porosity and CO2 diffusion kinetics [67].

Figure 4.

Relationship between dehydration rate and water content and CO2 absorption rate [58,66,67,68]: (a) relationship between dehydration rate and CO2 absorption rate; (b) relationship between water content and CO2 absorption rate.

Humidity affects the moisture content within concrete, leading to variations in the concentration of dissolved CO2 in the pore solution. Studies indicate that carbonation is most active at relative humidity levels between 50% and 70%, as moisture in the pores is neither excessive nor insufficient. In higher humidity environments (e.g., above 90%), concrete pores become saturated with water, hindering CO2 penetration and significantly reducing the carbonation rate [69]. Additionally, moisture differences influence carbonation-induced shrinkage and microstructural changes. Suda et al. [70] evaluating carbonation in cement paste at 20 °C under 11%, 43%, 66%, and 85% relative humidity demonstrated that humidity profoundly impacts carbonation shrinkage and microstructure: at 43% RH, shrinkage strain increases during early carbonation; at 66% RH, calcium silicate phases predominantly form, with minimal residual carbonated calcium hydroxide; and lower RH enhances C-S-H carbonation, while higher RH suppresses calcium hydroxide carbonation.

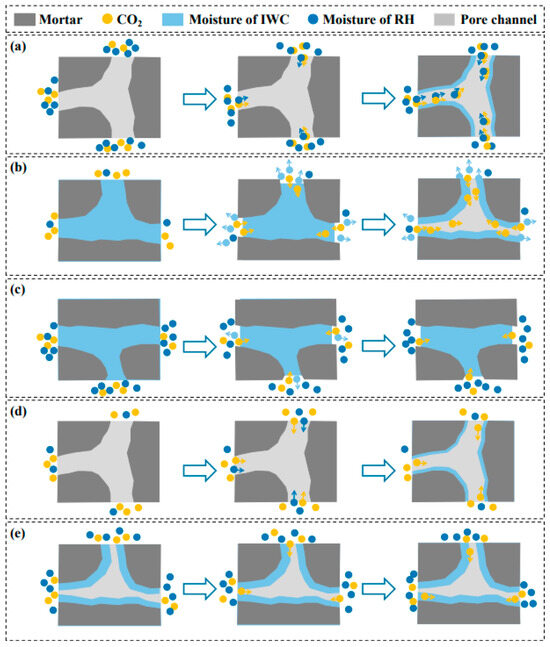

Regarding the synergistic effect of environmental humidity and material moisture content on carbonation, Wu et al. [71] found that under high RH with low initial moisture or low RH with high initial moisture, CO2 exhibits excellent penetration and diffusion capabilities. Under these conditions, carbonation significantly enhances the performance of recycled aggregate concrete, as illustrated in Figure 5. During subsequent curing stages, concrete is typically maintained at 90–95% relative humidity. This phase primarily aims to promote ongoing hydration reactions and further improve concrete strength and durability.

Figure 5.

Different moisture conditions in carbonation process of RCA [71]: (a) high RH with low IWC; (b) low RH with high IWC; (c) high RH with high IWC; (d) low RH with low IWC; (e) RH and IWC in relative equilibrium.

3.2. Carbon Dioxide Concentration and Gas Pressure

Increasing CO2 concentration can significantly enhance carbonation depth. However, when concentration exceeds a certain threshold, changes in the concrete’s surface and internal structure limit further carbonation, weakening the positive impact of higher concentrations. The degree of carbonation can be measured by carbon uptake—higher values indicate superior carbon capture performance and more complete carbonation reactions. A study by Zuo et al. [72] on accelerated carbonation (12 h curing after 72 h pre-curing) found that at CO2 concentrations of 20%, 40%, 60%, and 95%, the carbon uptake per kilogram of recycled aggregate concrete was 8.87 g, 12.28 g, 14.68 g, 16.64 g, and 17.95 g, respectively. However, diminishing returns were observed as follows: at 95% concentration, uptake increased by only 8.01% compared to 60%, whereas the increase from 40% to 60% concentration reached 35%. Analysis indicates that at lower concentrations, CO2 reacts on both the surface and interior of concrete, but limited concentration prevents optimal reaction efficiency. As concentration rises, carbonation intensifies, rapidly increasing carbon uptake. However, when concentration exceeds 60%, although reaction intensity remains high, surface densification obstructs further CO2 penetration, thereby restricting internal carbonation.

Generally, curing under higher pressure facilitates the dissolution of CO2 into pore water. However, the enhancement in CO2 absorption rate is marginal. Chang et al. [73] found that when CO2 gas pressure increased from 0.13 MPa to 1 MPa, carbon dioxide absorption increased by only approximately 10–20%. Furthermore, the degree of carbonation does not exhibit a proportional relationship with partial pressure; its growth rate diminishes as pressure increases [73]. Research by Shi et al. [23] demonstrated that when CO2 pressure exceeds 0.2 MPa, the curing effect no longer improves.

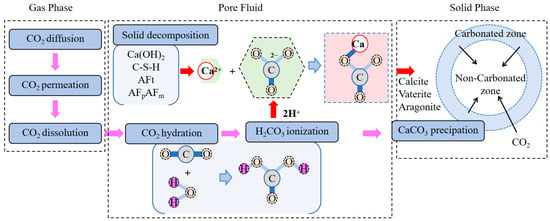

3.3. Pre-Hydration and Curing Duration

The mechanistic influence of pre-hydration duration on strength and microstructure remains insufficiently studied or contentious. Generally, within an appropriate range, longer pre-hydration time facilitates early-stage carbonation curing and strength enhancement in cementitious matrices. However, extended pretreatment consumes free water within specimens through hydration reactions, leading to insufficient moisture for promoting carbonation—a key mechanism illustrated in Figure 6. Zhang et al. [66] and Bukowski and Berger [74] demonstrated that shorter pre-hydration elevates CO2 uptake to 9.6%, with specimens achieving a 7.9 MPa strength increase after 71 h pre-hydration. Hu et al. [75] reported higher CO2 uptake following 2 h pre-hydration, attributing this to rapid heat release during curing that generates hydrates enhancing early-stage “carbon uptake and sequestration.” Conversely, Kottititum et al. [57] observed no correlation between 28-day compressive strength and pre-hydration time (potentially stage-dependent), though cement matrices pre-hydrated for 6 h with early carbonation curing developed denser pore structures. For cement clinker containing slowly hydrating β-C2S, optimal pre-hydration duration (18 h) exceeds that of C3S, achieving a maximum carbonation degree of 32.33% [13,66,67].

Figure 6.

Carbonation reaction mechanism of concrete matrix.

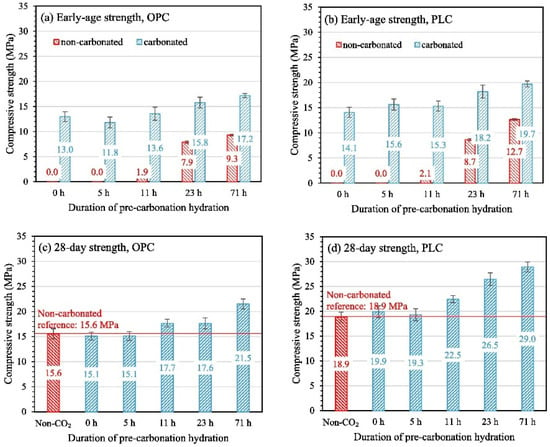

Curing time significantly impacts early carbonation efficiency and product content. Multiple studies [68,76] indicate that prolonged curing extends carbonation progression and increases calcium carbonate content, resulting in denser gel structures within the cementitious matrix that enhance concrete’s compressive strength and impermeability. However, excessive curing impedes mid-to-late-stage CO2 diffusion and strength development rates, highlighting the importance of appropriate curing duration for optimal performance. Zhan et al. [77] observed that cement’s compressive strength increases with extended curing time within 24 h, particularly showing significant growth within the first 2 h; as curing duration further increases, the strength gain gradually diminishes and eventually stabilizes. This occurs because prolonged curing allows more mineral and hydration phases to react with CO2 in the cement paste. Once all carbonatable materials have reacted, additional curing provides no further strength improvement. Compared to non-carbonated control groups (Figure 7), early carbonation more significantly enhances compressive strength in ordinary concrete than later stages, while lightweight aggregate concrete exhibits greater overall improvement [78]. Calcium sulfoaluminate cement paste achieved 70 MPa compressive strength after 24 h carbonation curing—exceeding its 28-day standard-cured strength—with the maximum strength increase occurring at 8 h curing [60]. Additionally, calcium carbonate fills pores while acting as nucleation sites for C-S-H [19,33,67], providing a theoretical basis for early strength development. Notably, γ-C2S mortar compacted at low water-to-solid ratio achieved 40 MPa within just 10 min of carbonation [74,79].

Figure 7.

Effect of curing time on different types of concrete [60].

Controlling pre-curing time and carbonation curing duration enhances the early strength of cement mortar, but this positive effect gradually diminishes with prolonged curing age. Chen and Gao’s study [80] demonstrated that cement mortar subjected to different pre-curing durations (2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 16 h, and 24 h) and carbonation curing periods (2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 16 h, and 24 h) showed the following compressive strength trends: with extended carbonation time, the 3-day and 7-day compressive strength initially increased then decreased, while the 28-day strength was minimally affected by carbonation duration. Compared to standard-cured specimens, the maximum strength enhancements after carbonation curing reached 30.1%, 16.9%, and 4.9% at 3, 7, and 28 days, respectively. The optimal pre-curing duration varied with carbonation curing time—for early compressive strength, shorter pre-curing was required as carbonation duration increased. This phenomenon is attributed to moisture loss during pre-curing and carbonation processes: both hydration and carbonation require water as reactants. When carbonation exceeded 4 h, prolonged pre-curing could deplete moisture reserves, interrupting subsequent reactions [81].

In summary, material moisture content, CO2 concentration, gas pressure, pre-hydration duration, and curing time all significantly influence early-stage carbonation curing, necessitating comprehensive consideration of these characteristics in carbonation reaction processes. While current research has partially elucidated the composition and structure of carbonation products, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding (1) formation, distribution, and evolution patterns of microstructures; (2) interconnection mechanisms between adjacent carbonated calcium silicate particles; and (3) dissolution–precipitation processes and reaction kinetics during calcium silicate carbonation—all representing urgent research priorities for advancing carbonation curing technology. To summarize the effects of the above key parameters more clearly, Table 1 compiles the recommended ranges of pressure, temperature, and time parameters for early carbonation curing, aimed at achieving optimal mechanical properties.

Table 1.

Summary of recommended ranges for key parameters in early-age carbonation curing.

3.4. Other Key Influencing Factors

In addition to moisture content, CO2 parameters, and curing time, the chemical composition of steel slag, the specific surface area of cementitious components, the types of admixtures and supplementary cementitious materials, and the water-to-binder ratio are also key factors affecting the effect of carbonation curing. The table below systematically summarizes the key parameters, influence laws, and research bases of each factor, providing a reference for process optimization.

The mechanism of action of the chemical composition of steel slag is mainly reflected in three aspects: (1) Free CaO and Ca(OH)2, as highly reactive calcium sources, can directly react with CO2 to form CaCO3. (2) C3S has a fast hydration rate and can continuously provide Ca(OH)2 to participate in the carbonation reaction; C2S, on the other hand, can directly react with CO2 to generate CaCO3 and amorphous SiO2. (3) The ferroaluminate phase has relatively low activity. Therefore, steel slag with higher contents of free CaO and C2S usually has a faster carbonation rate.

The influence of these components on the carbonation effect is mainly manifested in increasing the carbonation depth and carbon sequestration capacity. Regulating the composition is conducive to optimizing the carbonation efficiency. Wei et al. [83] pointed out that when the content of free CaO increases from 3% to 8%, the carbon sequestration rate after 72 h of carbonation increases from 12.3% to 21.7%, and the mortar strength increases by more than 40%. A study by Cheng et al. [84] showed that the 3-day compressive strength of SSC (Steel Slag Cement) is affected by the C3S/C2S ratio and C3S content, and the strength is optimal when the C3S content is 0.45 wt%. C3S hydrates rapidly, which is beneficial to the development of early strength; however, an excessively high content may lead to uneven distribution of hydration products, which is instead unfavorable for strength improvement.

The specific surface area and particle fineness regulate carbonation kinetics by changing the reaction contact area. Increasing the specific surface area can usually significantly enhance the degree of carbonation, thereby improving the carbonation depth and mechanical properties. Sakamoto et al. [85] pointed out that the suitable BET specific surface area of sodium ferrite powder is 2–7 m2/g. If it is lower than 2 m2/g, effective contact with CO2 is difficult, which affects the absorption performance; if it is higher than 7 m2/g, industrial preparation becomes relatively difficult. The preferred ranges are 2.1–6.5 m2/g, 2.6–6.0 m2/g, and 3.0–6.0 m2/g in sequence.

Admixtures and supplementary cementitious materials (such as slag, fly ash, setting accelerators, fibers, etc.) can adjust the pore structure and ion migration behavior of the system, and promote the formation of carbonation products. Their role is mainly reflected in improving the microstructure, thereby enhancing the durability and mechanical strength of the composite material. A study by Ukwattage et al. [86] showed that an appropriate amount of slag helps to improve the compressive strength after carbonation; Song et al. [87] found that adding 15% CaO can make the maximum carbon sequestration rate reach 7.86% under a mineralization curing pressure of 0.7 MPa.

The mechanism of influence of the water-to-binder ratio (w/cm) is as follows: a lower water-to-binder ratio is conducive to the formation of a dense matrix and promotes CO2 diffusion, but sufficient moisture must be ensured to maintain the carbonation reaction. Appropriately reducing the water-to-binder ratio can usually improve the strength and impermeability after carbonation, while excessive moisture will hinder CO2 transmission. Forsdyke and Lees [88] pointed out that the carbonation depth is proportional to the square root of time (d = k√t), where the proportional constant k is the carbonation coefficient, and its value is significantly affected by the water-to-binder ratio. Generally, the higher the water-to-binder ratio, the larger the porosity of concrete, and the corresponding carbonation coefficient also increases.

The early carbonation curing process comprises three stages: pre-curing, carbonation curing, and post-curing. Pre-curing adjusts the initial moisture content and pore structure of test specimens; carbonation curing demands the control of environmental parameters in a high-concentration CO2 environment; and post-curing supplements moisture to facilitate hydration. Its core influencing factors are multifaceted, as follows: the moisture content of specimens and environmental humidity must stay within a suitable range (e.g., 50–70% relative humidity), as excessively high or low levels will inhibit carbonation; increasing CO2 concentration can boost carbon sequestration, yet when it exceeds 60%, the surface densification effect weakens, and the impact of pressure is relatively insignificant; pre-hydration and curing time need to be properly matched—either too long or too short is unfavorable for strength enhancement, with a notable increase in curing strength observed within 24 h. Additionally, the chemical composition of steel slag (high free CaO and C2S are more ideal), the specific surface area of cementitious components (2–7 m2/g is suitable), admixtures, and the water–binder ratio all influence carbonation efficiency by regulating reaction activity, contact area, and pore structure, and the comprehensive optimization of these factors is key to improving the process.

4. Impact of Early Carbonation Curing on Cementitious Materials

4.1. Mechanical Properties

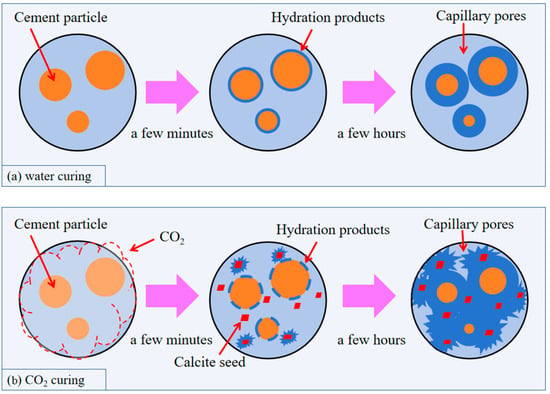

It is reported that early carbonation curing achieves over 90% of the 28-day compressive strength within just one day, as carbonation products encapsulate and bond adjacent particles to function as primary strength contributors similar to cementitious binders—with calcium carbonate delivering particularly significant strength enhancement [19,66]. Zhan et al. [77], Zhang and Shao [89] and Yang et al. [90]. demonstrated through comparative studies of cement clinker under identical conditions that early carbonation curing yields superior strengthening effects compared to conventional hydration. The key mechanism (Figure 8) reveals that in normally hydrated cement paste, hydration products begin depositing on cement particles within minutes of water exposure; within hours, unreacted particles become enveloped by these layers, slowing reactions and forming coarser, more porous microstructures. The critical distinction in CO2 curing lies in the presence of CO32− within pore solution, where Ca2+ ions preferentially interact with CO32− to form calcite crystals. These crystals act as natural seed particles, providing abundant nucleation sites for C-S-H gel growth, resulting in reduced early-stage coating of cement particles by hydration products. Consequently, calcium and silicate dissolution is enhanced, substantially increasing the overall reaction degree within hours while yielding significantly lower porosity in CO2-cured cement paste compared to water-cured counterparts [77].

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of microstructural evolution of cement paste when subjected to water curing and CO2 curing.

Comparative phase quantification by Bukowski and Berger [74] and Zhang et al. [91] revealed that γ-C2S exhibits superior carbonation reactivity and mechanical performance over CS and ordinary Portland cement. However, inconsistent carbonation conditions and calculation methods across studies currently hinder quantitative comparisons of carbon sequestration efficiency versus mechanical properties. What remains established is that early carbonation curing densifies the cementitious matrix and enhances deformation resistance.

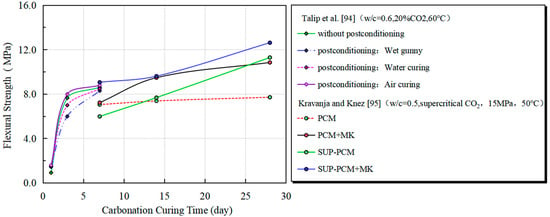

Carbonation curing not only elevates compressive strength but also substantially improves deformability. Bukowski and Berger [74] and Duo et al. [92] observed in engineered cementitious composites (ECCs) that carbonated specimens demonstrated saturated multiple-cracking behavior—achieving 28.8% higher flexural strength versus non-carbonated counterparts—despite limited carbonation depth (5–10 mm). This suggests carbonation can enhance load-bearing capacity in large-scale panels, potentially reducing cement usage in structural elements—a strategy meriting further investigation. Hu et al. [93] confirmed through displacement-controlled four-point bending tests that carbonation-cured ECCs exhibited 32% greater flexural strength and 69% increased deformation capacity compared to air-cured specimens. This enhanced deformability likely stems from microstructural improvements via carbonation-generated C-S-H and calcium carbonate, which effectively control crack propagation and boost fiber-bridging capacity. Studies by Talip et al. [94] and Kravanja and Knez [95] have shown that early carbonation curing can significantly enhance the early flexural strength of engineered cementitious composites (ECCs) materials, and this strength performance is superior to that of specimens under conventional curing at the same age (Figure 9). However, after 7 days of accelerated carbon dioxide curing, the strength growth of all curing groups enters a plateau stage, and the subsequent hydration has no longer a significant effect on improving the material strength.

Figure 9.

Effect of early carbonation curing on the flexural strength of cement-based materials.

4.2. Influence on Durability

The durability of cementitious matrices is primarily manifested in chloride penetration resistance, freeze–thaw resistance, and sulfate resistance, which directly determines the service life of reinforced concrete structures. The pore structure characteristics of cementitious matrices correlate with ion penetration rates. Chen et al.’s study [96] demonstrated that carbonation curing can significantly reduce the porosity and average pore diameter of the cement matrix, optimize the pore size distribution (by decreasing the proportion of macropores), thus refining the pore structure and potentially reducing the ion penetration rate. Specimens subjected to early carbonation curing demonstrate significantly enhanced performance: chloride diffusion coefficient and electrical flux are reduced by 27–85% and 14–36%, respectively, compared to normally hydrated specimens, while total chloride and free chloride content decrease by more than 50% [55,96,97,98]. The early carbonation curing process significantly affects the microstructure and durability indicators of cement-based materials by regulating CO2 pressure, temperature, and time. In the rapid chloride permeation test (RCPT), increasing the CO2 pressure (atmospheric to 0.1–0.5 MPa) can promote the formation of a denser calcium carbonate layer, reducing the electric flux by 14–36% and the chloride diffusion coefficient by 27–85% [99]. Meanwhile, the resistivity (ER) increases as the ionic concentration of the pore solution decreases, reflecting the densification of the pore structure. The water permeability first decreases and then increases with the increase in carbonization degree: moderate carbonization (≤16 h) fills the capillary pores, and the permeability coefficient decreases; however, too long a time or a relatively high temperature (>50 °C) will cause decalcification of the C-S-H gel and coarsening of the micro-pores, which will instead increase the permeability [100].

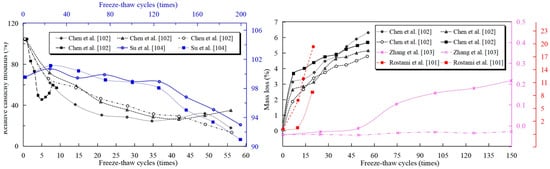

It is well established that freeze–thaw damage in cold regions significantly reduces concrete service life. Early carbonation curing mitigates this by consuming pore solution in the paste, thereby reducing ice formation pressure in concrete pores—effectively suppressing volumetric expansion and microcrack propagation. Rostami et al. [101] demonstrated after 20 freeze–thaw cycles that carbonation-cured concrete exhibited minimal mass loss (≈8.6 ± 0.2%), contrasting sharply with untreated specimens’ 19.2 ± 5.9% loss. With increasing cycles, carbonated samples not only maintained reduced mass loss but also showed enhanced relative dynamic elastic modulus and compressive strength [102] (Figure 10). Nevertheless, studies indicate potential adverse effects: free calcium carbonate may react with chloride ions, impeding hydration reactions. Consequently, further investigation is warranted regarding carbonation curing’s possible negative impacts on freeze–thaw resistance.

Figure 10.

Effect of early carbonation curing on freeze–thaw performance [101,102,103,104].

Sulfate attack on concrete primarily occurs through reactions with calcium hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide, forming expansive compounds like gypsum and calcium sulfoaluminate. This process simultaneously degrades the C-S-H gel structure, ultimately causing concrete expansion, cracking, and spalling [103]. Studies have demonstrated that the dense microstructure formed by early carbonation curing effectively blocks ingress of deleterious ions, thus enhancing sulfate resistance. Accelerated erosion tests confirm significantly reduced corrosion products in carbonation-cured specimens [104].

The durability of cementitious materials may also be compromised by carbonic acid water, such as in karst terrain where groundwater absorbs substantial CO2 to form carbonic acid [105]. Carbonic acid corrosion reduces pore solution pH, increases material porosity, and induces shrinkage cracking—ultimately diminishing strength and impermeability [106,107,108]. Yang et al. [109] demonstrated that carbonation curing followed by water curing reduces corrosion depth in cement mortar by up to 60%, attributed to a protective dense calcium carbonate layer formed during carbonation. However, extended carbonation curing progressively increases corrosion depth, potentially due to C-S-H gel shrinkage and pore coarsening from excessive carbonation, which weakens carbonic acid resistance [110,111,112].

Calcium ions in cementitious materials primarily originate from C-S-H gel and portlandite (Ca(OH)2), components that dissolve in aqueous environments leading to increased porosity, reduced mechanical performance, and compromised durability. While accelerated carbonation curing is generally believed to enhance calcium leaching resistance and improve longevity [113,114,115]—through consumption of CH, C2S, and C3S to suppress calcium dissolution, coupled with formation of a dense surface CaCO3 layer that impedes calcium diffusion [116,117]—contrary evidence reveals adverse effects: Chen et al. [114] and Xu et al. [118] demonstrated that 8–16 h carbonation mitigated compressive strength loss from leaching, yet extended carbonation intensified late-stage strength degradation, with cubic specimens exhibiting comparable or higher calcium silicate decalcification than powdered samples. Here, CaCO3 provides critical hardness and calcium sequestration (potentially forming protective films), while silica gel acts as filler-binder; nevertheless, excessive carbonation should be avoided in aqueous environments due to accelerated degradation risks during long-term calcium leaching.

5. Microstructural Analysis

Early carbonation curing significantly alters the microstructure of cementitious materials through reactions between CO2 and cement hydration products, generating mineral phases such as calcium carbonate. Compared to conventional hydration, short-term carbonation yields a microstructure enriched with reinforcing solid precipitates. Rostami et al. [99] demonstrated that 2 h carbonation produced 20 h compressive strength (50.0 MPa), substantially exceeding conventionally hydrated specimens (35.8 MPa), attributing this to calcium carbonate formation and amorphous calcium silicate–carbonate binding phases. Similarly, Wang et al. [60] and Kim et al. [119] observed accelerated hardening in calcium sulfoaluminate cement via early carbonation curing, markedly enhancing early-age strength. This improvement primarily stems from amorphous calcium carbonate and aluminum hydroxide gel generated during carbonation, which densify the cementitious microstructure.

Carbonation products of C3S and C2S exhibit volumetric expansions of approximately 108.7% and 92.5%, respectively. Considering the influence characteristics of the water–binder ratio, effectively controlling the carbonation process can optimize pore size and volume distribution, thereby improving the pore structure of cementitious materials [61,120]. Liu et al. [121] observed significantly reduced critical pore diameters in early carbonation-cured specimens, whereas prolonged carbonation increased the population of small pores. Studies indicate carbonation curing primarily reduces macro-pores and meso-pores, whereas natural hydration decreases macro-pores while increasing meso-pores [52,77]. Some researchers note that short-term carbonation minimally affects pore structure characteristics, which may relate to water–binder ratios and initial pore configurations [77].

Microhardness testing effectively evaluates early carbonation curing effects and micromechanical properties in cementitious matrices. Li et al. [61] demonstrated approximately 40% increased microhardness and enhanced abrasion resistance in early carbonation-cured specimens. For modified cementitious systems, incorporating mineral admixtures during early carbonation curing further elevates matrix microhardness, with surface microhardness exceeding internal values by over twofold—correlating directly with carbonation degree [121,122,123].

In summary, early carbonation curing effectively refines cementitious matrices by filling pores, optimizing pore size/volume distribution, and densifying microstructure—significantly enhancing microhardness and micromechanical properties. To clarify the mechanism by which carbonation enhances the performance of cement-based materials, microscopic testing methods such as XRD, TGA/DTA, and FTIR are widely employed, leading to the following consistent findings: XRD Analysis: After carbonation, the intensity of the characteristic peaks of portlandite (Ca(OH)2) in the hardened cement paste decreases significantly or even disappears. Meanwhile, the characteristic peaks of calcium carbonate crystalline phases (e.g., calcite and vaterite) are notably strengthened. This indicates that CO2 reacts with hydration products to form calcium carbonate, which serves as the material basis for structural reinforcement and pore refinement [124]. TGA/DTA Analysis: For carbonated samples, the weight loss rate at 400–500 °C (corresponding to the decomposition of Ca(OH)2) is greatly reduced, while the weight loss rate at 600–800 °C (corresponding to the decomposition of CaCO3) increases significantly. The calcium carbonate content calculated based on weight loss shows a positive correlation with mechanical properties such as compressive strength and microhardness, providing a quantitative basis for the performance improvement [41]. FTIR Analysis: The characteristic absorption peaks of CO32− appearing at ~870 cm−1, ~1420 cm−1, and ~713 cm−1 directly confirm the formation of carbonates. Some studies have also observed changes in the vibration peaks of siloxane bonds in C-S-H gels, suggesting that carbonation may cause structural changes in C-S-H, which contributes to the improvement of micromechanical properties [125]. These analyses also reveal differences caused by factors such as water-to-binder ratio and curing regime. For instance, under conditions of high water-to-binder ratio or insufficient curing, XRD and FTIR results show that the crystallinity of calcium carbonate is low or its distribution is uneven—this is consistent with the phenomenon of insignificant performance improvement under such conditions.

However, substantial microstructural research deficiencies persist: interfacial mechanisms between carbonation products (e.g., calcite and vaterite) and hydration products (e.g., C-S-H gel) remain systematically unelucidated; chemical kinetics and microstructural reorganization during hydration–carbonation dynamic coupling are poorly understood; quantitative characterization of spatial distribution, crystallinity, and densification of carbonation products in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) is lacking, hindering microstructure–macroperformance correlation; concurrently, in situ monitoring of microstructural evolution during carbonation and long-term stability data are critically deficient—particularly in complex systems containing slag, fly ash, or other admixtures—where carbonation pathways and product distribution patterns remain inadequately explored. Nevertheless, existing studies have accumulated quantitative data regarding the improvement effect of early-age carbonation on the ITZ of concrete, which provides important references for addressing the aforementioned research gaps. Research has shown that early-age carbonation can significantly strengthen this traditionally weak link by generating calcium carbonate to fill pores and optimizing the C-S-H structure, resulting in a 10% to over twofold increase in the microhardness of the ITZ, a 3–5 percentage point decrease in porosity, and an approximately 30% reduction in the thickness of the ITZ. Specific quantitative data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects of early-age carbonation on concrete interfacial transition zone (ITZ) properties.

Early carbonation curing significantly enhances the mechanical properties and durability of cement-based materials—with 1-day compressive strength reaching over 90% of the 28-day standard curing level (γ-C2S showing the optimal carbonation reactivity), ECC’s flexural strength and deformation capacity increasing by up to 32% and 69%, respectively (improving crack control), chloride diffusion coefficient reducing by 27–85%, mass loss after 20 freeze–thaw cycles being only ~8.6%, and the dense microstructure enhancing resistance to sulfate and carbonated water corrosion—but excessive carbonation (e.g., curing time > 16 h or temperature > 50 °C) may cause C-S-H decalcification, micro-pore enlargement (reducing impermeability), and potential reactions between free calcium carbonate and chloride ions, highlighting the importance of rational regulation of carbonation parameters to maximize its advantages.

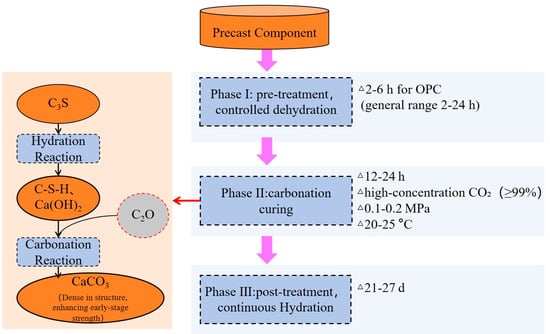

6. Practical Application: Large-Scale Carbonation Curing Scheme in Prefabricated Component Production

The early-stage carbonation curing technology can enhance the early strength of prefabricated components and shorten the demolding time, thereby significantly improving production efficiency. It is one of the key approaches for the prefabricated component industry to achieve energy conservation and carbon reduction. The complete industrial carbonation production process for prefabricated components, as defined in Figure 11, consists of three sequential stages: namely, pre-treatment, carbonation curing, and post-treatment [21].

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the industrial process flow and the hydration–carbonation coupling mechanism in early-age carbonation curing.

In the pre-treatment stage, after demolding, the components need to undergo pre-curing in a specific environment (such as a ventilated area or a space with controlled temperature and humidity). This process aims to adjust the internal moisture content of the components, as excessively high or low humidity will inhibit the diffusion and reaction of CO2. According to the experimental data [97], the preprocessing time typically ranges from 2 to 6 h, but the specific duration needs to be dynamically adjusted based on the component size, mix proportion, and environmental conditions. The precise control of this link is the foundation for the subsequent carbonation efficiency. For instance, in its precast component production adaptation scheme, CarbonCure monitors the moisture content of components in real time through sensors to ensure that the humidity is within the optimal range of 10–20% when entering the carbonation stage, thereby creating conditions for the in situ mineralization of carbon dioxide [130].

In the carbonation curing and post-treatment stages, the components are transferred to a sealed carbonation curing chamber (also referred to as a carbonation autoclave). The carbonation chamber is the core equipment, essentially a pressure vessel with precisely controllable environmental conditions. Its size needs to be customized according to the type of prefabricated components and production capacity requirements, ranging from small test chambers of a few cubic meters to large industrial reaction chambers exceeding 70 cubic meters. The system injects CO2 gas into the chamber and maintains it at a specific concentration, pressure, and temperature—this process usually takes 12 to 24 h to ensure that CO2 can fully penetrate into the interior of the components and complete the reaction [131].

For maximum efficiency in industrial production, high-concentration CO2 or even pure CO2 (≥99%) is usually preferred to maximize the reaction rate and carbon sequestration efficiency. The pressure range in industrial applications is relatively wide, and good results can typically be achieved between 0.1 MPa (atmospheric pressure) and 0.2 MPa [73,82]. Although higher pressure (e.g., 1–5 bar) can further improve efficiency, it will significantly increase equipment costs and safety requirements, requiring a cost–benefit trade-off [132].

The carbonation reaction can proceed efficiently at room temperature (20–25 °C) [64,70]. Excessively high temperatures (e.g., above 60 °C) will instead reduce the solubility of CO2, which may be detrimental to the reaction [133]. Components that have completed carbonization typically need to be moved out of the curing room. Depending on requirements, they should undergo curing measures such as sprinkling water, spraying mist, or be kept under standard curing conditions for several days, even up to 21 to 27 days. This process ensures that the performance of the components meets the design requirements.

For the quality control of carbonized precast components, the key indicators include CO2 sequestration capacity, carbonation depth, and compressive strength improvement rate. Typically, the carbon sequestration potential of precast concrete can reach 14.83–23.73 kg CO2/m3 [134]. Regarding the measurement of CO2 sequestration capacity, two main methods are commonly used as follows: (1) Heat the sample and employ Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to measure its mass loss. This allows for the accurate calculation of calcium carbonate content, and further derivation of CO2 sequestration capacity. (2) Use X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to analyze the phase composition of the sample, thereby determining the yield of calcium carbonate in a quantitative or semi-quantitative manner. For carbonation depth measurement, the phenolphthalein indicator method is the most commonly used and intuitive approach. The specific steps are as follows: cut the component open, and spray phenolphthalein solution on the cross-section. The uncarbonized area (with high alkalinity) will turn red, while the carbonized area (neutral) remains colorless. The carbonation depth is then determined by measuring the depth of the colorless area.

In the field of prefabricated component production, the large-scale application of carbonation curing technology has a commercial foundation and practical cases, with numerous industry cooperation and technology promotion achievements fully proving its feasibility and broad market prospects—such as the in-depth collaboration between Elematic and Carbonaide, and the global promotion of CarbonCure’s carbonation technology, which all strongly support its commercial implementation; currently, from the perspective of technical pathways for industrial large-scale application, carbonation curing solutions in prefabricated component production are mainly divided into two directions: “raw material substitution carbonation” (typically represented by Blue Planet, achieving carbon sequestration by replacing aggregates) and “in-situ carbonation during production” (typically represented by CarbonCure, achieving carbon sequestration by injecting CO2 during the mixing process), both of which have been verified in practice with clear industrial data and commercial cases; although the initial investment in this technology is relatively high, from the perspective of full-life-cycle cost control and long-term strategic development, prefabricated component enterprises that take the lead in deploying and applying carbonation curing technology on a large scale will gain significant first-mover advantages in the context of low-carbon transition policies and market competition.

7. Conclusions and Prospects

- (1)

- Calcium carbonate exhibits superior thermal stability and erosion resistance compared to C-S-H gel in cementitious materials, with its composition and properties being more readily tunable. As a primary contributor to early-age strength, its performance warrants greater research focus on how mineral carbonation hydration activity influences resultant products—an area currently underexplored.

- (2)

- The formation and accumulation patterns of carbonation products substantially refine pore structures while enhancing cement paste impermeability and mechanical strength. Regulating temperature and CO2 concentration enables controlled transformation of calcium carbonate polymorphs to optimize target phase formation. Although industrial carbon sequestration primarily targets precast elements, precise carbonation process control effectively achieves carbon capture objectives in manufacturing settings.

- (3)

- Optimizing moisture content, curing duration, and pre-hydration time enhances carbon sequestration efficiency. Key parameters include ≈4.5% moisture content at 0.5 water–binder ratio and ≈40% dehydration rate at 0.3–0.4 ratios (varying by aggregate/concrete type). CO2 concentrations > 60% or pressure > 0.2 MPa inhibit carbonation kinetics, while excessive curing impairs mid-late hydration. Pre-hydration predominantly affects early-strength development, with clinker composition dictating requirements: slow-hydrating β-C2S necessitates 18 h pre-hydration (achieving 32.33% carbonation) versus shorter durations for C3S.

- (4)

- Early carbonation curing significantly improves chloride resistance, freeze–thaw durability, and sulfate attack resistance. By refining pores and densifying the matrix, it creates effective barriers against deleterious ion ingress, thereby extending structural service life. The process also elevates microhardness by ≈40%, with surface hardness exceeding internal values by >2× in modified cementitious systems.

- (5)

- Currently, the rules for the formation, distribution, and evolution of microstructures during concrete carbonation remain unclear. This is especially true for the interface interaction mechanism between carbonation products (e.g., calcite) and hydration products (e.g., C-S-H), the hydration–carbonation coupling process, the distribution of products in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), and their long-term evolution behavior—these have not been systematically established, and research in admixture systems is even more limited. Going forward, priority should be given to advancing in situ monitoring technologies like Raman spectroscopy and XRD mapping to track the carbonation process in real time, while combining micromechanical tests to clarify interface behaviors. In testing, standardized accelerated carbonation experimental methods need to be developed, key parameter thresholds defined, and comparable data provided for industrial use. For long-term performance research, the limitations of short-term experiments must be addressed as follows: durability tracking should be conducted under the combined effects of natural carbonation and the environment to accurately assess concrete’s service life. In terms of materials and processes, efforts should be made to integrate carbonation technology with low-carbon materials such as recycled aggregates, geopolymers, and industrial waste residues, explore carbonation strengthening paths for non-traditional systems, and optimize the synergy between early carbonation and late hydration using kinetic models. Additionally, continuous, large-scale carbonation curing equipment should be developed, full-life-cycle assessments enhanced, and carbon emission reductions and economic benefits quantified to promote the application of this technology in practical engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and J.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, L.T.; validation, J.C., J.Y. and K.W.; formal analysis, L.T.; investigation, L.T.; resources, K.W.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, J.Y.; supervision, K.W.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi, grant number “2025GXNSFBA069565, 2024GXNSFGA010002” and “The APC was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52178194”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study (Review). Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi (2025GXNSFBA069565; 2024GXNSFGA010002), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52178194).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lei Tang is employed by Guangxi Airport Management Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kweku, D.W.; Bismark, O.; Maxwell, A.; Desmond, K.A.; Danso, K.B.; Oti-Mensah, E.A.; Quachie, A.T.; Adormaa, B.B. Greenhouse Effect: Greenhouse Gases and Their Impact on Global Warming. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Su, B.; Ma, Z.; Cui, K.; Chen, W.; Shen, P.; Zhao, Q.; Poon, C.S. Damage characterization of carbonated cement pastes with a gradient structure. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 157, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Su, B.; Ma, Z.; Sun, R.; Zheng, Y.; Cui, K.; Shen, P.; Poon, C.S. Characterization of the inhomogeneity of mineralized steel slag compacts (MSSCs) and its effect on mechanical properties and damage. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 162, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, H.; Kelishadi, M.; Bahmani, H.; Wu, C.; Ghiassi, B. Development of sustainable HPC using rubber powder and waste wire: Carbon footprint analysis, mechanical and microstructural properties. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2024, 29, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lyu, G.; Fang, K. Carbon emissions assessment of concrete and quantitative calculation of CO2 reduction benefits of SCMs: A case study of C30-C80 ready-mixed concrete in China. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Nelson, J.P.; Gupta, V.; Mobley, P.D. Life-cycle assessment of concrete production with carbon capture and carbon upcycling process. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.B.; Silvestre, J.D.; Bohne, R.A. Embodied GHG emissions of reinforced concrete and timber structures: Relevance, driving factors and target values. Build. Environ. 2025, 275, 112753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasailam, F.; Purnell, P.; Black, L. Factors affecting the carbon footprint of reinforced concrete structures. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Su, B.; Ma, Z.; Sun, R.; Shen, P.; Li, J.; Poon, C.S. Investigation of mechanical properties and damage characterization of cement pastes prepared by coupled carbonation-hydration curing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 160, 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Ye, Z.; Chang, J. Early Hydration Activity of Composite with Carbonated Steel Slag. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 40, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Beushausen, H. Durability, service life prediction, and modelling for reinforced concrete structures—Review and critique. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tu, J. Carbonation performance of loaded portland cement, fly ash, and ground granulated blast furnace slag concretes. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2023, 44, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Li, V.C.; Ellis, B.R. Optimal Pre-hydration Age for CO2 Sequestration through Portland Cement Carbonation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 15976–15981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, N.A.M.; de Medeiros-Junior, R.A.; Dias, R.L.; Witzke, F.B. Preliminary study of the effect of carbonation curing on geopolymers. Rev. IBRACON Estrut. Mater. 2024, 17, e17110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Gao, Y.; Li, S. Hydration Properties of Circulating Fluidized Bed Fly Ash under Carbonation Condition. J. Build. Mater. 2024, 27, 837–845. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. Study on Mineral Carbonation Curing of SolidWaste Lightweight Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Goyal, S. Accelerated carbonation curing of cement mortars containing cement kiln dust: An effective way of CO2 sequestration and carbon footprint reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Tu, Z.; Guo, M.-Z.; Wang, D. Accelerated carbonation as a fast curing technology for concrete blocks. In Sustainable and Nonconventional Construction Materials Using Inorganic Bonded Fiber Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, R.; Seo, J.; Park, S.; Amr, I.T.; Lee, H.K. CO2 Uptake and Physicochemical Properties of Carbonation-Cured Ternary Blend Portland Cement–Metakaolin–Limestone Pastes. Materials 2020, 13, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Hao, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Poon, C.S. The development of sustainable cement pastes enhanced by the synergistic effects of glass powder and carbonation curing. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 4138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Fan, P.; Bao, W.; Chang, L.; Wang, J. Study on the impact of using decarbonized gasification slag for CO2 mineralization andstorage to prepare calcium carbonate. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2024, 52, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Gong, K.; Luo, X.; Gu, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, F. Synergistic carbonation reaction mechanism of steel slag-magnesium slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 498, 144015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Liu, M.; He, P.; Ou, Z. Factors affecting kinetics of CO2curing of concrete. J. Sustain. Cem. Mater. 2012, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.; Klemm, W. Accelerated curing of cementitious systems by carbon dioxide. Cem. Concr. Res. 1972, 2, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.F.; Berger, R.L.; Breese, J. Accelerated Curing of Compacted Calcium Silicate Mortars on Exposure to CO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1974, 57, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Hu, S.; Liu, C. Effect of Extended Carbonation Curing on the Properties of γ-C2S Compacts and Its Implications on the Multi-Step Reaction Mechanism. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 6673–6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chang, J. Comparison on accelerated carbonation of β-C2S, Ca(OH)2, and C4AF: Reaction degree, multi-properties, and products. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, L.; Zhi, X.; Liu, L.; Ren, X.; Ye, J. Development on Hydration Activity, Properties of Low-Calcium Minerals and Its Clinkers. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 51, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Liu, L.; Ye, J.; Qian, J. Effect of Liquid Environment on Hydration Activity of Ternesite-Dicalcium Silicate Composite Minerals. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 50, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodbrake, C.J.; Young, J.F.; Berger, R.L. Reaction of Hydraulic Calcium Silicates with Carbon Dioxide and Water. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1979, 62, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Fang, Y.; Shang, X. The role of β-C2S and γ-C2S in carbon capture and strength development. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 4417–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersisa, A.; Moon, K.-Y.; Kim, G.; Cho, J.-S.; Park, S. Internal carbonation of calcium silicate cement incorporated with Na2CO3 and NaHCO3. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 462, 139732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtepenko, O.; Hills, C.; Brough, A.; Thomas, M. The effect of carbon dioxide on β-dicalcium silicate and Portland cement. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 118, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W.; Olek, J. Carbonation behavior of hydraulic and non-hydraulic calcium silicates: Potential of utilizing low-lime calcium silicates in cement-based materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 6173–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkman, S.; MacDonald, M.; Hooton, R.D.; Sandberg, P. Properties and durability of concrete produced using CO2 as an accelerating admixture. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 74, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkman, S.; MacDonald, M. Carbon dioxide upcycling into industrially produced concrete blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, N.A.; Borçato, A.G.; Sakata, R.D.; Medeiros-Junior, R.A. Effect of carbonation curing and Na2O concentration of metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete on efflorescence formation. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 114, 114376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntzinger, D.N.; Gierke, J.S.; Kawatra, S.K.; Eisele, T.C.; Sutter, L.L. Carbon Dioxide Sequestration in Cement Kiln Dust through Mineral Carbonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendek, E.; Ducom, G.; Germain, P. Carbon dioxide sequestration in municipal solid waste incinerator (MSWI) bottom ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 128, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venhuis, M.A.; Reardon, E.J. Carbonation of cementitious wasteforms under supercritical and high pressure subcritical conditions. Environ. Technol. 2003, 24, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xu, R.; Ning, F.; Chen, Z. Experimental study on early mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete after NaHCO3 carbonation. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2025, 42, 3352–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselbach, L.M.; Thomle, J.N. An alternative mechanism for accelerated carbon sequestration in concrete. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 12, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhai, J.; Lai, H.; Lu, F.; Zong, Y.; Xiong, R.; Guan, B.; Chang, M. Research progress of microorgan-ism-carbonization modified steel slag and its effect on hydration characteristics of cement. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2025, 42, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Shi, C.; Farzadnia, N.; Hu, X.; Zheng, J. Properties and microstructure of CO2 surface treated cement mortars with subsequent lime-saturated water curing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 99, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B.; Qureshi, T.; Adak, D. Cement-based solidification of nuclear waste: Mechanisms, formulations and regulatory considerations. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teir, S.; Eloneva, S.; Zevenhoven, R. Production of precipitated calcium carbonate from calcium silicates and carbon dioxide. Energy Convers. Manag. 2005, 46, 2954–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.W.; Arvidson, R.S.; Lüttge, A. Calcium Carbonate Formation and Dissolution. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 342–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Choi, D.; Kim, M.H.; Park, Y. Tuning Crystal Polymorphisms and Structural Investigation of Precipitated Calcium Carbonates for CO2 Mineralization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 5, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X. Parameters of Accelerated Carbonation of Steel Slag-Based Cementitious Materials and Its High Temperature Performance. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Yio, M.; Wong, H.; Buenfeld, N. Real-time monitoring of carbonation of hardened cement pastes using Raman microscopy. J. Microsc. 2022, 286, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Mechanism Research on CO2 Mineralcarbonation Curing of Building Materials Basedon Non-Hydraulic Cementitious Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Hong, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, D.; Dong, B. Compositions and microstructures of hardened cement paste with carbonation curing and further water curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 121724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wan, C.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Effect of pre-hydration age on phase assemblage, microstructure and compressive strength of CO2 cured cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ruan, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Zeng, Q.; Yan, D. Morphological characteristics of calcium carbonate crystallization in CO2 pre-cured aerated concrete. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 14610–14620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Wei, J.; Shi, C. Corrosion Resistance of Cement-based Materials by Carbonation Curing to Carbonic Acid Solution. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 51, 2890–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, S.; Hu, M.; Geng, Y.; Meng, S.; Jin, L.; Hu, Q.; Han, S. Early age accelerated carbonation of cementitious materials surface in low CO2 concentration condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottititum, B.; Phung, Q.T.; Maes, N.; Prakaypan, W.; Srinophakun, T. Early Age Carbonation of Fiber-Cement Composites under Real Processing Conditions: A Parametric Investigation. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; He, P.; Tu, Z. Effect of preconditioning on process and microstructure of carbon dioxide cured concrete. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 42, 996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Drissi, S.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Shi, C. Investigation on the influential mechanism of FA and GGBS on the properties of CO2-cured cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 142, 105186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wei, X.; Cai, X.; Deng, H.; Li, B. Mechanical and Microstructural Characteristics of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Exposed to Early-Age Carbonation Curing. Materials 2021, 14, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, Z.; Chen, X. The Performance of Carbonation-Cured Concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimi, W.O.; Adekunle, S.K.; Ahmad, S.; Amao, A.O. Carbon dioxide sequestration characteristics of concrete mixtures incorporating high-volume cement kiln dust. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chen, P.; Xiang, W.; Hu, C.; Li, F.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y. Exploring the Effect of Moisture on CO2 Diffusion and Particle Cementation in Carbonated Steel Slag. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Shi, C.; Hu, X.; Ouyang, K.; Ding, Y.; Ke, G. Effect of early CO2 curing on the chloride transport and binding behaviors of fly ash-blended Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 288, 123113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshed, A.Z.; Shao, Y. Influence of moisture content on CO2 uptake in lightweight concrete subject to early carbonation. J. Sustain. Cem. Mater. 2013, 2, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shao, Y. Early age carbonation curing for precast reinforced concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, B.J.; Poon, C.S.; Shi, C.J. Materials characteristics affecting CO2 curing of concrete blocks containing recycled aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 67, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; He, F.; Wu, Y. Effect of pre-conditioning on CO2 curing of lightweight concrete blocks mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 26, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šavija, B.; Luković, M. Carbonation of cement paste: Understanding, challenges, and opportunities. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 117, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, Y.; Tomiyama, J.; Saito, T.; Saeki, T. Effect of relative humidity on carbonation shrinkage and hydration product of cement paste. Cem. Sci. Concr. Technol. 2020, 73, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Ju, X.; Guan, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, S. Synergistic Effects of Environmental Relative Humidity and Initial Water Content of Recycled Concrete Aggregate on the Improvement in Properties via Carbonation Reactions. Materials 2023, 16, 5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Zhao, X.; Luo, J.; He, Z.; Zhao, J. Investigating the impact of carbonation curing concentrations on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Fang, Y.; Shang, X.; Wang, J. Effect of Accelerated Carbonation on Microstructure of Calcium Silicate Hydrate. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 43, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, J.; Berger, R. Reactivity and strength development of CO2 activated non-hydraulic calcium silicates. Cem. Concr. Res. 1979, 9, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yao, Y.; Sun, J.; Xie, Q.; Yang, H. An insight of carbonation-hydration kinetics and microstructure characterization of cement paste under accelerated carbonation at early age. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejdoub, R.; Hammi, H.; Khitouni, M.; Suñol, J.J.; M’Nif, A. The effect of prolonged mechanical activation duration on the reactivity of Portland cement: Effect of particle size and crystallinity changes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, B.J.; Xuan, D.X.; Poon, C.S.; Shi, C.J. Mechanism for rapid hardening of cement pastes under coupled CO2-water curing regime. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cai, X.; Jaworska, B. Effect of pre-carbonation hydration on long-term hydration of carbonation-cured cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndzila, J.S.; Yang, Z. Carbonation properties of ion-doped non-hydraulic calcium silicate binders: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Gao, X. Effect of carbonation curing regime on strength and microstructure of Portland cement paste. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, V.G.; Vayenas, C.G.; Fardis, M.N. A reaction engineering approach to the problem of concrete carbonation. AIChE J. 1989, 35, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Fu, Y.; Si, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, Q. The characterization and mechanism of carbonated steel slag and its products under low CO2 pressure. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ni, W.; Wang, X.; Li, K. Current Research of the Carbonization Technology of Steel Slag. Conserv. Util. Miner. Resour. 2019, 39, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]