Abstract

This study presents the development and evaluation of a novel solid–gas reactor designed to enhance the hydrogen reduction kinetics of tellurium oxide (TeO2) under atmospheric pressure. Such gas–solid reactions can be processed in several types of reactors, including but not limited to fixed-bed reactors, moving-bed reactors, and fluidised-bed reactors. A combination of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and experimental validation was employed to design and optimise a reactor’s geometry and gas-flow distribution. Single-phase CFD simulations were performed using the k–ω SST turbulence model to examine gas-flow behaviour, temperature uniformity, and gas-flow dead zones for two lance designs. The modified lance produced a stable swirling flow that improved gas distribution and eliminated stagnation regions. Experimental trials confirmed the simulation outcome in optimised gas-flow: the redesigned reactor achieved up to 65% conversion after 1 h and 70% after 2 h, a marked improvement over the rotary kiln, which required 5–6 h to reach similar levels. However, excessive gas flow led to cooling effects that reduced conversion efficiency. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of integrated CFD-guided reactor design for accelerating hydrogen-based oxide reduction and advancing sustainable metallurgical processes.

1. Introduction

The advancement of metal extraction is accompanied by increasing demands and challenges in furnace technologies, especially in improving the yield efficiency while minimising energy consumption and CO2 emissions without sacrificing economic cost. Computational simulations during the design phase of furnaces are now a very well-established industrial practice, as they help identify risks such as hotspots, thermal stresses, and structural deformation before failure [1,2]. Virtual testing also reduces development cost by enabling rapid evaluation of design modifications. At the laboratory scale, simplified simulations can similarly support experimental development by guiding design choices and providing a means to evaluate or validate hypotheses. Although extensive research has focused on complex multiphase or multi-physics models for furnace optimisation, comparatively few studies investigate the utility of simple single-phase models as early-stage screening tools. Such models are fast, accessible, and easy to interpret, making them particularly valuable when resources are limited.

This study supports part of the RecycleTEAM project [3], funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, which investigates the recycling of Bi2Te3 for establishing the circularity of Tellurium (Te). A key step in this process is the reduction in TeO2 to metallic Te. Achieving a high conversion is critical because an incomplete conversion leads to a Te–TeO2 mixture that cannot be further purified in subsequent metallurgical steps. Although the reduction in TeO2 is currently a pure research-stage issue, improving its efficiency is a necessary prerequisite for enabling recovery routes for Te.

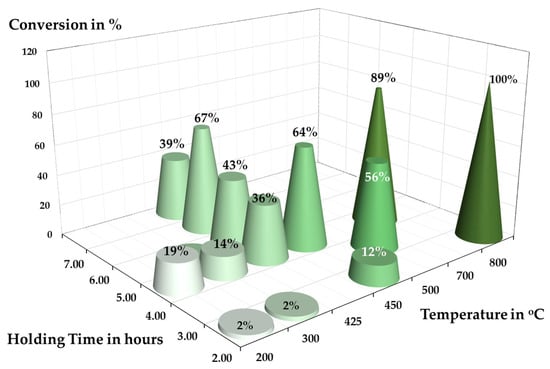

In a previous study of Chung et al. [4], the effectiveness of TeO2 reduction using hydrogen was examined using a rotary kiln tube furnace. In a solid–gas reaction system, the highest conversion from TeO2 to metallic Te recorded was 67.67%, conducted at 425 °C with a 6 h holding time. When transitioning into a solid–liquid–gas system, where liquid products were formed, the conversion increase to 89%, conducted at 700 °C. Although thermochemistry calculations show that the reduction is feasible even at low temperatures, the experimental results highlight that the practical conversion is strongly controlled by kinetic limitations, an inherent constraint of rotary kilns, which typically exhibit slow gas–solid reaction kinetics.

This raises the question of whether higher conversion rates of TeO2 can be achieved using a reactor with faster reaction kinetics without increasing the operational demands, such as pressure, temperature, or equipment complexity. To address this gap at the laboratory scale, a novel solid–gas reactor designed to accelerate kinetic conditions under atmospheric pressure is presented in this paper. The geometry of the reaction chamber and gas inflow parameters were first analysed using ANSYS Fluent (Ansys, Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA), and the findings were subsequently verified through experimental trials. The objective of this study is to design and validate a simple, versatile solid–gas reactor that enhances kinetic conditions for TeO2 reduction under atmospheric pressure. Specifically, this work (i) develops a reactor geometry guided by CFD modelling and (ii) validates the design through experimental trials. By combining computational and experimental findings, this study aims to demonstrate an improved process pathway for the possible Te recovery.

2. Study Background

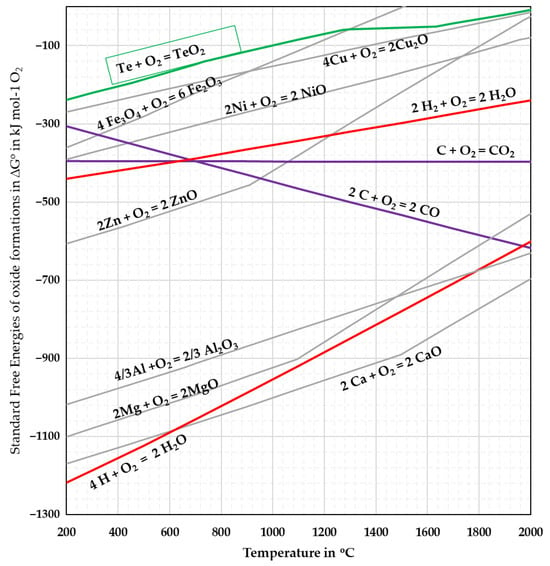

TeO2 is typically produced through targeted hydrometallurgical processing of anode sludge [5] and finds its application primarily in acousto-optic material [6]. In the primary production route, TeO2 is not intended as a precursor for metallic Te; however, in the treatment of Bi2Te3 waste, several authors [7,8,9] have mentioned the possibility of precipitating Te as TeO2 during hydrometallurgical treatments. For circularity and recovery purposes, the reduction in secondary TeO2 to Te using hydrogen was previously reported by Chung et al. [4]. The experimental reduction results obtained in a rotary kiln are summarised in Figure 1. According to the Richardson–Ellingham diagram in Figure 2, the reduction in TeO2 with hydrogen is thermodynamically feasible; with hydrogen exhibiting a stronger affinity to oxygen. Although calculations indicate feasibility even at room temperature, DTA–TGA measurements showed that the reaction initiates only around 300 °C. This discrepancy highlights that the process is kinetically, rather than thermodynamically, limited.

Figure 1.

Conversion of TeO2 was conducted in a rotary kiln adapted from [4].

Figure 2.

Richardson–Ellingham diagram adapted from [4].

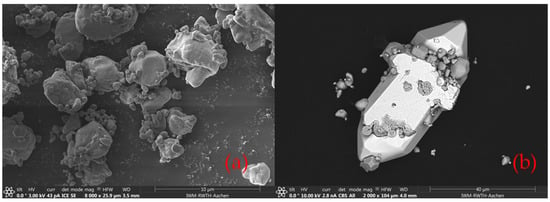

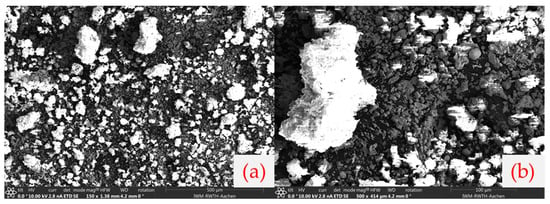

The kinetic constraints arise primarily from the morphology of the TeO2 powder. SEM images (Figure 3a) show that the particle exhibits a dense, non-porous morphology with no observable internal pore network or microstructural pathways that would enable significant gas penetration. Under these conditions, H2 must access oxygen exclusively at the external particle surface, meaning that the reduction process is highly sensitive to gas–solid contact and to the renewal of fresh H2 at the reaction interface. This is further supported by the proposed mechanism, reported by the authors to resemble a typical gas–solid reaction that involves adsorption, surface reaction, and desorption of by-products and eventually the transformation of oxide into metal [4]. Generally, the reaction may be limited by the slow external gas-film transfer, the slow surface reaction, or the diffusion through a product layer.

Figure 3.

SEM images showing morphology of (a) TeO2 powders, (b) Te crystal, and entrapped unreacted TeO2 [4].

These kinetic limitations were reflected in the previous rotary-kiln trials, which proceeded slowly despite long holding time up to 6 h, because the gas–solid contact efficiency was inherently limited by the reactor configuration. Rotary kilns rely on bulk rotation and indirect mixing, which leads to insufficient local gas renewal, suppressing reaction kinetics in systems where the gas–solid interaction must be rapid and continuous. The observed onset temperature near 300 °C and the incomplete conversion achieved at 425 °C reflect these kinetic barriers.

The evolving morphology of the reacting solid further influences the achievable conversion. SEM observations from the previous study showed that during long holding times, metallic Te does not form a uniform product shell around individual TeO2 particles. Instead, Te nucleates and develops into large, faceted crystals that grow outward and adhere to neighbouring particles. Because the reduction progresses slowly, due to the dense, non-porous nature of TeO2 and the inherently limited gas–solid kinetics, these Te crystals can physically enclose or ‘trap’ pockets of unreacted TeO2 (Figure 3b). Once encased within metallic Te, the remaining oxide becomes inaccessible to H2, causing the reaction to gradually slow down through diffusion resistance or total blockage. This morphology-driven entrapment effect, rather than a classical diffusion-controlled product-layer mechanism, explains why extended holding times fail to achieve full conversion. In a reactor system where the gas–solid reaction is already slow, this crystallisation becomes a secondary barrier that prematurely halts the reaction. No further publication had specified the reaction pathway and rate-limiting step to characterise the kinetics of this reaction.

In addition to gas–solid contact limitations, the results suggest that temperature also plays a decisive role in controlling the overall conversion. Although the reduction is thermodynamically feasible at low temperature, the kinetics accelerate strongly as the temperature increases, consistent with typical solid–gas reduction behaviour. In experimental trials, a strong increase in conversion was observed from 500 °C onwards, which coincides with the melting point of the reaction product, elemental Te (Tm = 449.5 °C). Once Te begins to liquefy, the system transition from a solid–gas to a solid–gas–liquid regime. The presence of a liquid product improves local mass transfer and facilitates the detachment of the reacted interface, thereby reducing kinetic resistance and enabling higher conversion. Despite this benefit, processing the reduction in a liquid–gas regime is unfavourable due to the volatilisation of Te that happens even below its boiling temperature.

Overall, three combined kinetic limitations emerge as follows: (1) poor mass-transport and insufficient H2 gas renewal at powder surface, (2) inherently slow gas–solid interaction on a dense, non-porous oxide, and (3) tendency for Te crystals growth and trapping unreacted TeO2 during long treatments. These limitations make clear that a different reactor approach other than the rotary kiln is needed. Designing this new system requires understanding how established solid–gas reactor types manage gas delivery and mixing, and which principles can be adapted to overcome the limitations.

2.1. Solid–Gas Reactors

Solid–gas reactors are used extensively in metallurgical and chemical processes, where a solid phase reacts with a gaseous reagent. Their performance depends strongly on temperature control, mass transfer, pressure drop, and residence-time distribution [10]. The most common reactor configurations are fixed-bed, moving-bed, and fluidised-bed reactors, each of which offers distinct advantages and limitations that are relevant for selecting an appropriate design for laboratory-scale TeO2 reduction.

Fixed-bed reactors consist of a stationary packed bed through which the gas flows. They are simple to operate and provide good thermal control, particularly in non-adiabatic or multi-tubular configurations [11,12]. Despite their advantages, fixed-bed reactors face challenges such as non-uniform heat transfer, high-pressure drop, and flow misdistribution. These characteristics are important for the present study because high controllability of fixed-bed systems is desirable for laboratory-scale TeO2 reduction, yet their mass-transfer limitations may restrict reaction rates.

Moving-bed reactors (MBRs) contain continuously flowing granular solids in contact with a counter-current or co-current gas phase [13]. This configuration was used in previous TeO2 reduction trials. MBRs are common in metallurgical processes such as ironmaking, lead-zinc production, and zinc recovery via the Waelz Process [14,15,16,17]. While they enable continuous throughput with lower pressure-drop than fixed-beds, MBRs typically show broad residence-time distributions, particle attrition, agglomeration, and uneven temperature profiles. These issues were also observed in earlier TeO2 trials in [4], which required long holding times to achieve high conversion due to slow effective kinetics (compare Figure 1).

Fluidised-bed reactors (FBRs) suspend fine particles in an upward-flowing gas stream [18]. Their excellent heat and mass transfer make them attractive for large-scale operations such as the CircoredTM process of H2 iron ore reduction [19] and sulphide roasting [20]. Despite these advantages, FBRs require narrow particle-size distributions, exhibit particle attrition, and demand careful velocity control. The TeO2 precursor used in this study may not fluidise uniformly according to Geldart’s classification of fluid-particle [21], and would be prone to entrainment loss, making FBRs unsuitable at the gram scale.

The previous study on TeO2 reduction has primarily relied on a moving-bed type system, i.e., rotary kiln, which, while versatile, is constrained by slower kinetics and relatively low efficiency in gas–solid contact. Fixed-bed systems offer controllability but limit gas–solid interaction, while full fluidisation introduces unnecessary complexity for small-scale research. Taken together, none of the conventional reactor configurations provides both the kinetic efficiency and the operational simplicity required for laboratory-scale TeO2 reduction under atmospheric pressure.

To address this gap, the work introduces a solid–gas reactor concept that combines the operational simplicity and stability of a fixed-bed configuration with features of fluidised operation to enhance gas–solid interaction. The novelty of the present system is the development of a hybrid solid–gas reactor that does not conform to classical fixed-bed, moving-bed, or fluidised-bed designs. The objective is to establish a laboratory-scale system capable of increasing TeO2 conversion, while remaining experimentally accessible and adaptable for further process development. The performance of this new reactor will be experimentally benchmarked against the conversion rates achieved in the previous work using a rotary kiln, under a selected temperature condition, to isolate the effects of the improved gas-flow dynamics. As part of this development, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is employed to characterise gas-flow behaviour within the chamber.

2.2. Simulation with Computational Fluid Dynamics

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a numerical method for simulating fluid flow and heat transfer parameters by solving systems of equations using computer systems [1]. It provides insight into flow behaviour and physical phenomena that are difficult to measure experimentally, and enables visual prototyping and design optimisation before building physical systems, reducing development time and cost [22,23].

Most CFD models treat fluids as continuous media and can represent steady or transient flow, laminar or turbulent regimes, and, when needed, multiphase or reactive systems. Analytical solutions are limited to simple geometries, while empirical correlations offer quick estimates but apply only to conditions similar to those under which they were developed [22,23,24]. CFD therefore provides a more general and predictive approach for complex or unconventional designs.

A typical CFD workflow consists of three stages: pre-processing (geometry, meshing, and boundary conditions), solving (numeric calculation of mass, momentum, and energy conversion), and post-processing (visualisation and analysis) [25]. In the present work, a single-phase, non-reactive, stationary model was employed. While this simplification does not describe the particle motion, reaction kinetics, or phase transformation, it offers a fast, computationally efficient method to isolate and only analyse the fundamental gas-flow patterns. This specific focus aligns with the primary objective of this study, which is to design a system to improve the TeO2 reduction process’s conversion as compared to the rotary kiln system. Although CFD is a powerful and flexible method, its results are not exact because they rely on mathematical models that approximate real-world physics. For this reason, simulations are most effective when combined with experimental validation.

In the field of metallurgy and gas–solid reactor design, CFD has become an important tool for optimising thermal efficiency, gas distribution, and mixing. For instance, prior studies have employed single-phase CFD to design hydrodynamic cavitation [26], flotation column [27,28], and a flow reactor [29,30]. The results from these studies demonstrate that such simplified models provide sufficiently accurate guidance for geometry screening and identification of key flow properties before introducing multiphase complexity. This modelling strategy is well practised in early-stage reactor development, where it is used to characterise core features, in this case, the gas flow, because it predominantly governs the performance of gas–solid systems.

Mathematical Model

The flow behaviour within a designed reaction chamber can be analysed using CFD in ANSYS Fluent (version 2024 R2). The governing equations that are applied in the simulations are based on fundamental principles of fluid mechanics and heat transfer. Among them, the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) formulation was applied, with the governing equations based on conservation of mass (Equation (1)), momentum (Equation (2)), and energy (Equation (3)).

In the RANS formulation, additional terms arise from velocity fluctuations, requiring a turbulence model to close the system of equations. Among available models, the k − ω shear stress transport (SST) turbulence model was selected, as it reliably predicts flow separation and performs well under adverse pressure gradients. The k − ω SST model combines the strengths of the k − ϵ and k − ω models, which complement each other. The SST model combines both approaches through a blending function, which applies the k − ω model near walls and transitions to the k − ϵ model farther away in the free stream [27].

Both the k − ϵ and k − ω models belong to the two-equation RANS family, in which transport equations for turbulent kinetic energy, k (Equation (4)), and a second variable ε (Equation (5)) are solved, capturing the temporal and spatial changes in turbulence, including processes such as convection and diffusion. The key distinction between them lies in their second transported variable [27].

2.3. Standard Model

Transport equation for turbulent kinetic energy :

The blending function F1 (Equation (6)) seamlessly combines the and turbulence models. F1 approaches zero in the free stream and unity near walls. The turbulent viscosity is calculated with a limiter to avoid over-prediction (Equation (7))

In short summary, the SST model was selected because the chamber design involves strong boundary layer interactions, recirculation, and potential flow separation, conditions where SST offers proven reliability.

The flow field was solved under the assumption of steady-state conditions. A steady-state solution refers to a condition where variables such as velocity, flow, and pressure, as well as temperature, no longer change with time. This is performed by implementing the SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations) algorithm, which is widely used for pressure-velocity coupling in CFD [31]. The method is computationally efficient and avoids the cost of transient simulations while maintaining mass and momentum conservation. The cycle is repeated in an iterative loop until convergence is reached, meaning that the changes in flow variables from one iteration to the next become negligibly small. Through this iterative approach, a stable steady-state solution of the reacting flow inside the chamber was obtained.

3. Design of Solid–Gas Reactor

A laboratory-scale reaction chamber was designed to address the kinetic limitations identified in the previous section. The requirements, in addition to remaining simple and inexpensive to fabricate, are to maintain continuous renewal of hydrogen at the powder interface and to avoid stagnant gas zones where the reaction becomes transport-limited. Furthermore, excessive holding time is to be avoided to prevent Te crystal growth.

To fulfil these objectives, the design requirements included: (1) the ability to sustain atmospheric-pressure operation up to ~450 °C for solid–gas reactions, (2) sufficient gas residence time for surface reaction, (3) minimising stagnant regions inside the chamber, and (4) handling high gas-flow rates without excessive entrainment of fine powders. A powder-trap section was therefore incorporated into the outlet pathway to mitigate particle loss. The conceptual basis of the chamber draws inspiration from fixed-bed, moving-bed, and fluidised bed operation. While the solid remains in a fixed position, the inflowing gas induces partial fluidisation and stronger mixing, enabling enhanced mass transfer without the complexity of a fully fluidised system.

The key novelty of this non-standard reactor geometry lies in the way the gas is introduced, through a top-to-bottom injection rather than the conventional bottom-to-top configuration used in fluidized beds. This orientation ensures that the highest gas momentum directly impacts the powder bed, improving turbulent mixing and renewing hydrogen at the reaction interface. The directed high-velocity jet also suppresses early Te nucleation and crystal growth by keeping the particles in constant turbulent motion. This avoids the formation of large, rigid Te crystals that would otherwise encapsulate unreacted TeO2 and restrict further reduction. The dual effect, enhanced mass transfer and suppression of obstructive crystallisation, is essential for sustaining the reduction reaction to achieve higher conversion.

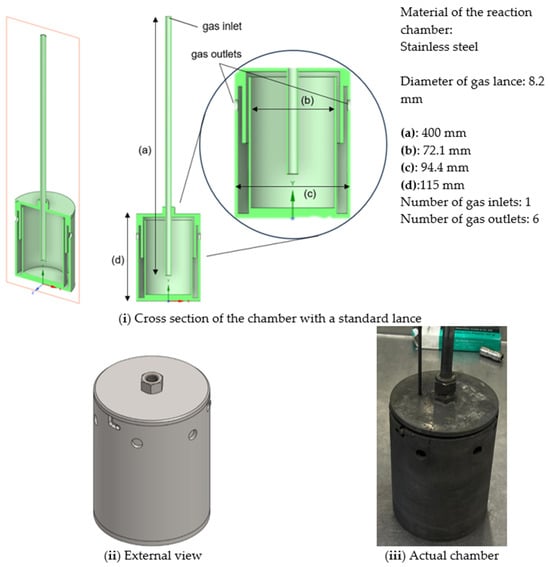

The reactor body is constructed from stainless steel for thermal resistance, chemical compatibility with TeO2, and ease of fabrication. The geometry consists of a cylindrical, double-walled chamber with a vertical gas-injection lance positioned at the centre (Figure 4). Gas enters through the lance, flows downward to the chamber bottom, then rises along the inner wall and exits into a trap zone before leaving through lateral outlet holes. A thermocouple port is integrated into the chamber lid to allow in situ temperature monitoring during operation.

Figure 4.

Schematic design of the chamber.

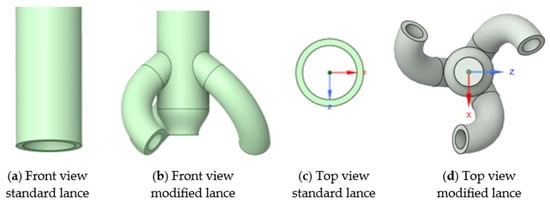

Although a mechanical mixer would provide ideal solid–gas mixing and maximise heat and mass transfer, space limitations and design constraints prevent its installation. Instead, the modified gas-lance design was developed to replicate the mixing effect by generating a controlled swirling motion of the inflowing gas (Figure 5), promoting turbulence without mechanical parts.

Figure 5.

Design of lances used for the solid–gas reactor.

While temperature is a confirmed driver of the reduction reaction kinetics (as seen in prior rotary kiln studies from Figure 1), the hypothesis here is that the engineered flow field of the new chamber, particularly with the modified lance, fundamentally enhances gas–solid contact and reactant delivery, leading to superior conversion even at shorter holding time and similar operating temperature.

The design process was supported by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis, which was used to evaluate flow distribution and potential powder entrainment. By combining simulation with practical construction considerations, the final design balances experimental accessibility, cost efficiency, and improved kinetic performance for laboratory-scale TeO2 reduction studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. CFD Simulation

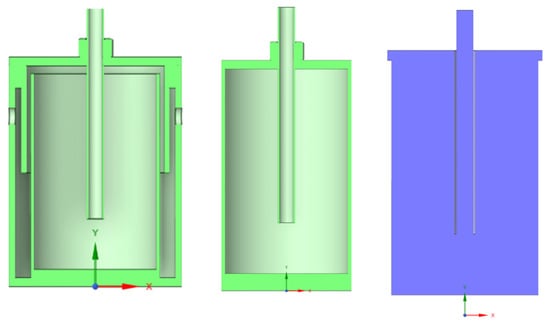

To evaluate the flow behaviour within the designed chamber and to identify the optimal gas injection configuration for the reduction in TeO2 with hydrogen, a single-phase CFD simulation was conducted in ANSYS Fluent (version 2024 R2). Only the gas phase was modelled, and the movement of the solid particles was inferred indirectly from the gas-flow patterns by considering the movement path lines of the gas. The computational domain corresponds to the internal volume of the reaction chamber, excluding external walls and structural components that are irrelevant for flow dynamics. Figure 6 illustrates the fluid domain used for simulation, including the chamber interior and the reduced lance length.

Figure 6.

From left to right: cross-section of reaction chamber, inner chamber, and reduced lance length, volume of interest (fluid domain) for simulation.

A mesh size of 0.5 mm was selected for both the standard lance and the modified lance after mesh sensitivity analysis (compare Appendix A). This resolution was found to provide sufficient accuracy while maintaining manageable computational requirements. Using this mesh size, gas was introduced through the respective lance inlet at different volumetric flow rates of 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24 l/min. These rates provide sufficient gas velocity to promote vigorous mixing and enhance gas–solid interaction, while remaining safely below the threshold at which powders are carried out of the chamber by the gas stream (powder entrainment).

Simulations were performed using the k − ω SST turbulence model and a pressure-based solver with the SIMPLE algorithm for pressure–velocity coupling. The simulation is run until the set residual value is reached, indicating convergence. The number of solver iterations is set at 5000 to ensure the simulation has enough iterations to fully converge. In addition to gas path lines, the simulations also calculated the temperature distribution profile for those flow rates where experimental trials were conducted. This allowed assessment of how gas velocity influences heat transfer behaviour and thermodynamic conditions inside the chamber.

The domain was initialised using Fluent’s standard initialisation with values relative to the specified cell zone. Gauge pressure was set to 1.164 × 10−10 Pa (effectively zero-gauge pressure). The initial velocity field in the x-, y-, and z-directions was prescribed as UX = UZ = 0 ms−1, while UY was set according to the inlet flow rate (compare Table 1). The negative value represents the initial bulk flow direction used for the relative reference frame. Turbulence quantities were initialised with a turbulent kinetic energy k = 0.05387 m2s−2 and a specific dissipation rate ω = 52.4437 s−1. These conditions were used to start the iterative solution.

Table 1.

Conversion of gas-flow rate into gas-flow velocity.

The boundary condition at the inlet was prescribed as a velocity inlet with a velocity magnitude according to Table 1, specifying normal to the boundary in the reference frame. Turbulence at the inlet was defined using the intensity-viscosity-ratio method with a turbulent intensity of 5% and a turbulent viscosity ratio of 10 (default settings). The outlet was set as a pressure outlet with a gauge pressure of 0 Pa. Backflow conditions, applied only if reverse flow occurred, were defined using a normal direction specification and the same turbulence settings as the inlet. All solid surfaces were modelled as stationary, no-slip walls with standard roughness modelling. Wall roughness was assigned with a roughness height of 0 m and a roughness constant of 0.5, following the sand-grain roughness formulation.

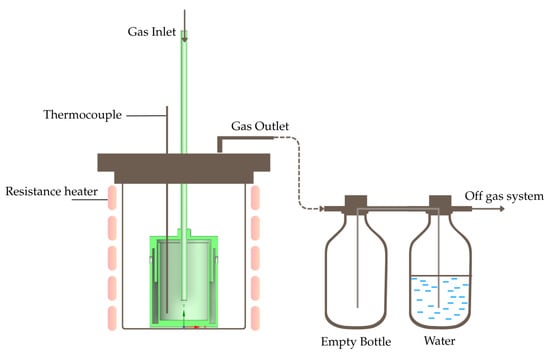

4.2. Experimental Validation

The identical starting material as the previous study, tellurium oxide powder (99.99 wt.% TeO2, d90 = 15 μm) obtained from Wuhan Tuocai Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China, was used in this study for comparability purposes. The reduction was conducted in the designed chamber on both separate lances, placed inside a resistance-heated furnace (Thermostar, Aachen, Germany), as shown in Figure 7. An additional thermocouple probe was used to monitor the actual temperature within the materials. The procedure began by adding the powders at 20, 60, and 100 g. The reactor was then heated at 300 K/min until 425 °C, and a gas mixture of 8 l/min hydrogen with 7 l/min or 16 l/min of nitrogen was introduced to initiate the reduction process. Nitrogen was used not only to shield the system but also to support the desired flow conditions due to the high overall gas volume. Two bottles were placed connected to the furnace’s gas outlet; the empty bottle is to keep any solid particles trapped, while the watered bottle is to cool down the gas before going into the off-gas system. After a holding time of 1 or 2 h, the hydrogen supply was stopped, while keeping nitrogen flow to flush out any remaining hydrogen and aid in cooling the reactants. The reactor was then left to cool down to room temperature by simply switching off the furnace; during this time, no reactions take place within the chamber. Once the reactor had cooled, the total weight loss was recorded with uncertainties of ±0.005 g, and the conversion of the TeO2 was computed with the following equation:

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of experimental setup.

Twenty-four experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of gas-flow rate and holding time on the hydrogen reduction in TeO2. These included 12 experiments for each gas lance design with 1 and 2 h of holding time. The parameters for each experiment, including gas-flow rate and holding time, are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental Parameters.

5. Results and Discussion

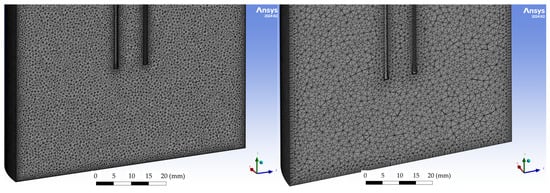

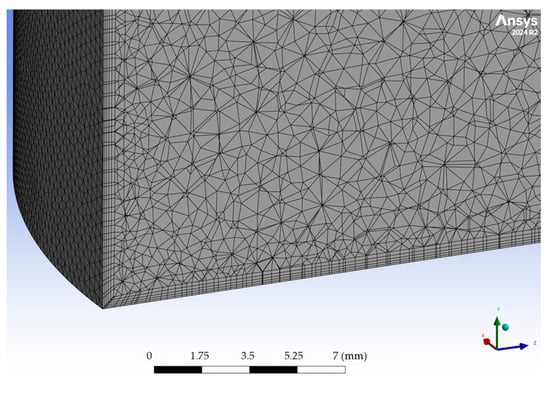

5.1. Mesh Generation and Quality Assessment

The domain was discretised using an unstructured tetrahedral mesh, resulting in 8.2 million cells, 17.7 million faces, and 2.1 million nodes. Mesh quality was evaluated using the standard ANSYS Fluent diagnostics. The minimum orthogonal quality was 0.0569, and the maximum aspect ratio was 86.28, both within the acceptable limits for RNAS turbulence modelling of internal flows. The smallest cell volume was 6.27 × 10 −13 m3, and the maximum cell volume was 2.97 × 10 −10 m3, with face areas ranging from 5.80 × 10−9 m2 to 9.42 × 10−7 m2. No negative volumes or non-manifold elements were detected during mesh check.

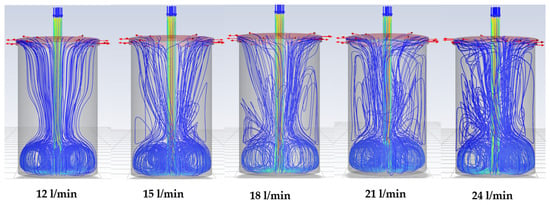

5.2. Simulation Results

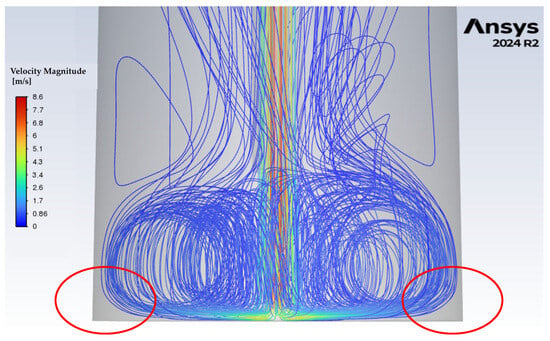

The single-phase simulations of gas-flow path lines with the standard lance are shown in Figure 8. The results reveal intense turbulence in the lower half of the chamber, where the powders are located. This turbulence is then expected to cause intense mixing in the powder materials, suggesting that gas–solid interaction in this setup is already far stronger than in the rotary kiln (Figure 9). However, the simulations also expose a consistent issue across all tested flow rates, stagnant regions at the base of the chamber where no gas flow occurs (Figure 10). In practice, these zones likely correspond to TeO2 powder becoming trapped along the chamber edges. Such stagnant regions, referred to as reaction dead zones, are expected to limit the overall reduction efficiency. Even at higher flow rates, the perpendicular chamber walls and flat base hinder the turbulent stream from fully circulating and dislodging the powder in these areas, leaving portions of the material with limited exposure to the reducing gas.

Figure 8.

Gas-flow path lines (arrows) in the standard lance model with increasing flow rate.

Figure 9.

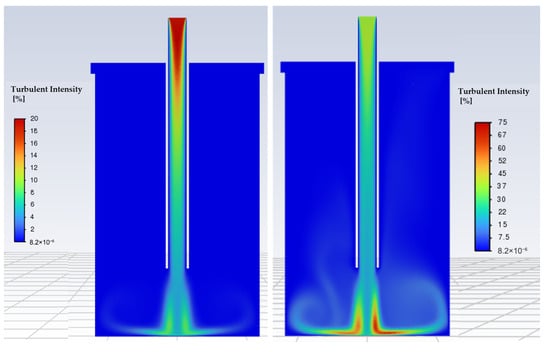

Turbulence intensity profiles in the reaction chamber, (Left)15 l/min, (Right) 24 l/min.

Figure 10.

Zoomed-in view of gas-flow path lines at 15 l/min flow rate, highlighting reaction dead zones within the chamber (red markings).

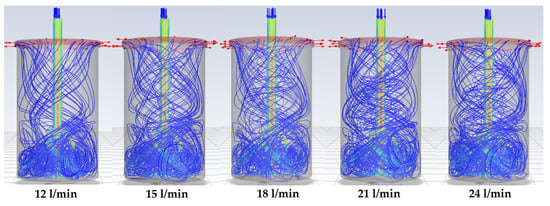

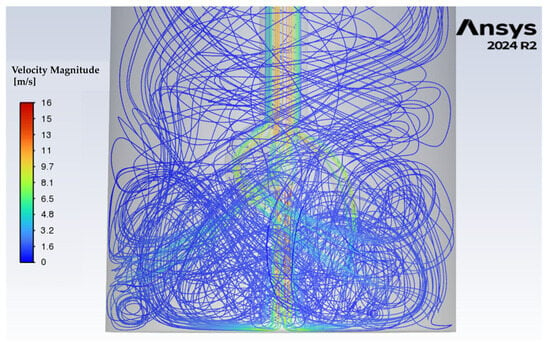

To address this limitation, a modified lance (see Figure 5) is developed to alter the flow dynamics inside the chamber. Simulations with the modified lance (Figure 11) show a pronounced swirling motion of the gas throughout the chamber, persisting until the gas exits. Importantly, the tangential sweeping motion generated by the angled nozzle outlets (Figure 12) minimises or eliminates dead zones. This design feature is expected to prevent TeO2 powder from accumulating along the chamber walls, thereby ensuring more uniform contact between the gas phase and the solid particles.

Figure 11.

Gas-flow path lines (arrows) in the modified lance model with increasing flow rate.

Figure 12.

Zoomed-in view of gas-flow path lines at 15 l/min, illustrating minimal to no reaction dead zones within the chamber.

The simulation results revealed clear differences between the standard and modified lance, closely matching the expectations formulated during the chamber design phase. The modified lance proved particularly effective in minimising the formation of reaction dead zones by redirecting the gas flow at the point of entry and generating a sustained swirling motion within the chamber. This improved gas distribution enhances the likelihood of uniform contact between hydrogen and TeO2 particles, thereby increasing their participation in the reduction reaction. Together, these findings confirm that the modified lance design directly mitigates reaction dead zones and improves reactant delivery to the solid catalyst bed. This enhancement in mass transfer provides the mechanistic basis for the superior kinetic performance of the current chamber over the rotary kiln, which is quantitatively demonstrated in the following section by a direct benchmark comparison under controlled temperature conditions for gas–solid reactions.

5.3. Experimental Results

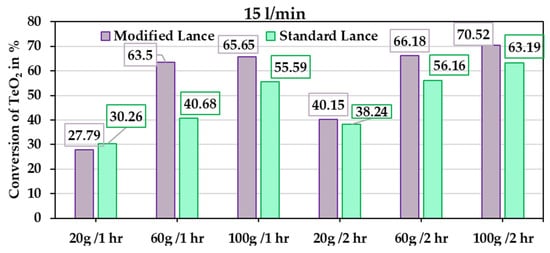

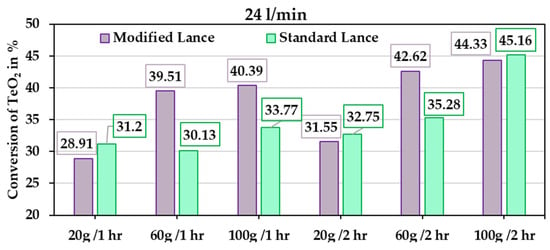

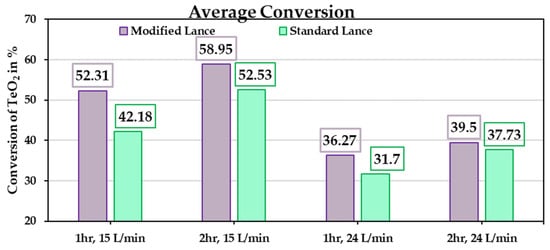

The primary objective of this experimental study is to benchmark the performance of the new chamber design against the conventional rotary kiln. The conversion results from the experimental trials (Table 2) are shown in Figure 13. Figure 14 presents the extent of reduction for different TeO2 powder masses at holding times of 1 and 2 h, under gas-flow rates of 15 l/min and 24 l/min, respectively. In general, the modified lance outperforms the standard lance, which aligns with the simulation results showing that the modified lance enhances gas-flow dynamics. Although complete conversion of TeO2 was not achieved in any trial, the results represent a significant improvement compared to the rotary kiln, especially considering the much shorter holding times applied here. The average conversion is shown in Figure 15, with the lowest value at 31.7% for a holding time of 1 h. For comparison, a similar result in the rotary kiln requires approximately 4 h of holding, yielding 36.8% conversion. This demonstrates that the current chamber design accelerates the reaction kinetics.

Figure 13.

Reduction extent for different powder masses at various holding times with a gas-flow rate of 15 l/min.

Figure 14.

Reduction extent for different powder masses at various holding times with a gas-flow rate of 24 l/min.

Figure 15.

Average conversion of TeO2 from the 24 experimental trials.

To demonstrate this kinetic acceleration quantitatively, a direct performance benchmark is provided in Table 3. At a comparable temperature of 425 °C, the new chamber achieves >50% conversion in just 1–2 h. In contrast, the rotary kiln requires 6 h to reach >50%, and its conversion at the 2 h mark is only ~12% despite having a higher temperature of 450 °C. This improvement at a comparable temperature provides strong evidence that the enhanced flow dynamics of the new design are the primary factor for the increased reaction rate. These results address the two key limitations mentioned in the study background: (1) mass transport is enhanced by the engineered gas-flow that minimises dead zones and prevents stationary regions, and (2) metal growth and crystallisation are mitigated by maintaining shorter process times and keeping the powder bed in constant motion.

Table 3.

Comparison of conversion between the current chamber and previously published results in the rotary kiln.

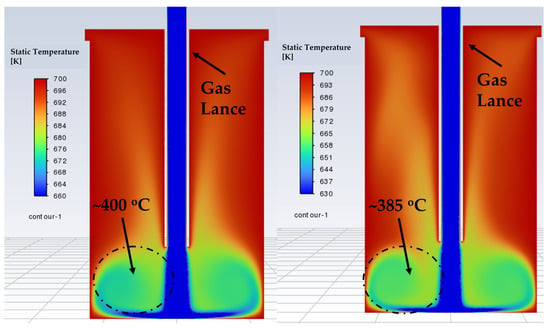

During the design phase, it was hypothesised that higher gas-flow rates would enhance particle agitation, promote greater gas–solid interfacial contact, and thereby increase conversion. However, the experiments showed the opposite trend, where conversion decreased at a higher flow rate. This effect is explained by the significant drop in reactor temperature during the experiments. At 24 l/min, the chamber temperature fell from the preheated 425 °C to about 375 °C, a decrease of ~50 °C. The temperature drop arises from the large difference between the preheated chamber and the incoming room-temperature gas. This reduction in effective reactor temperature alters the thermodynamic driving force of the reaction and slows down the reduction process, despite improved gas mixing. A similar trend was observed in both the standard and modified lance. At 15 l/min, the drop was less severe, with the chamber stabilising near 400 °C.

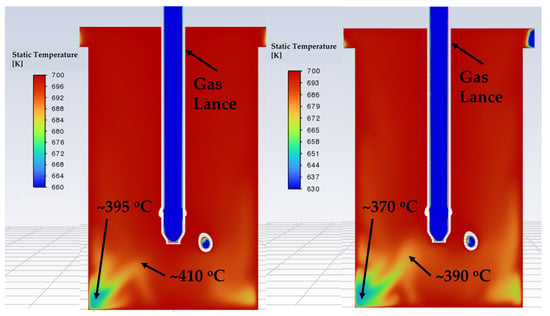

The temperature distribution in the reactor under flowing gas was later investigated through simulation. The results confirmed that higher flow rates cause greater cooling in both the standard and modified lance designs. The cross-sectional temperature profiles are illustrated in Figure 16 and Figure 17. These ranges were selected locally to clearly show the differences inside the reactor. At 15 l/min, the simulated effective reactor temperature (~400 °C) matched well with the actual measured value (~400 °C) for both the standard lance and the modified lance. At 24 l/min, the simulated temperature was slightly higher (~385 °C) than the actual measured value (~375 °C). In Figure 16, the standard lance produces a broad temperature gradient extending from the reactor centre to the chamber walls, which likely influences the thermochemistry and contributes to lower conversions. In contrast, the modified lance (Figure 17) produces a narrower gradient confined mainly to the outer regions, with temperature gradually increasing toward the centre. Importantly, the effective reactor temperatures are comparable between the two lance designs at each tested flow rate, i.e., standard lance at 15 l/min vs. 24 l/min and modified lance at 15 l/min vs. 24 l/min. This similarity isolates the influence of the gas-flow pattern, indicating that the observed performance differences are driven by the resultant improved kinetic conditions (e.g., turbulence and mixing) rather than by a systematic temperature offset.

Figure 16.

Cross-sectional temperature profile of the standard lance model. (Left) 15 l/min, (Right) 24 l/min.

Figure 17.

Cross-sectional temperature profile of the modified chamber model. (Left) 15/min, (Right) 24 l/min.

When comparing powder masses, the lowest performance occurred at 20 g. In contrast, reduction extents for 60 g and 100 g were nearly identical. The lower conversion obtained with the 20 g trials is likely related to differences in powder bed structure and gas–solid contacting. At 20 g, the powder forms a relatively shallow bed with low flow resistance. Under these conditions, the incoming mixed gas passes through the bed more rapidly, leading to likely channelling or partial gas bypassing. This reduces the effective residence time and decreases the gas–solid contact efficiency.

In contrast, the 60 g and 100 g powder beds are taller and more densely packed, which increases the flow resistance and distributes the gas more uniformly across the bed compared to the 20 g. This leads to higher pressure drop and increases residence times, hence improving the conversion. This behaviour is consistent with established gas–solid reaction principles such as the Ergun relationship for packed beds, which predicts lower velocities and improved contact in deeper beds. Although direct measurements of pressure drop or bed permeability were not obtained, the observed trend in the conversion aligns well with expected flow behaviour for the different input masses.

Even after 2 h of reduction, complete conversion was not achieved. The highest extent, approximately 70%, was obtained with the modified lance. At 60 g and 100 g of input materials, small clumps of the reduced Te–TeO2 mixture were observed in both chamber configurations, which led to both positive and negative outcomes. These agglomerates are expected to have two counteracting effects as follows: (1) they can hinder bulk mixing and increase local flow resistance, diverting gas to unreacted zones, and (2) they can restrict gas penetration into the agglomerates themselves, potentially slowing reactions in particle interiors. This physical hindrance to reagent access presents a primary challenge for achieving complete conversion in this system and may require strategies to improve bed fluidity or disrupt agglomeration more effectively. While the results are consistent with a process influenced by solid-state diffusion, the operative mechanism can only be confirmed through a full kinetic analysis, which is beyond the scope of this work.

To visually examine the microstructure of the reduced product, SEM imaging was performed on samples from selected trials (100 g, 1 h, 15 l/min, and standard lance). This sample was selected as it contains roughly 50% of unreacted TeO2, suitable to demonstrate any entrapment. Figure 18 shows the resulting Te–TeO2 mixture, where the bright contrast in certain regions is attributed to local charging effects, consistent with the mixed conductive (Te) and insulating (TeO2) nature of the reduced product. Metallic Te crystals (grey particles) are visible alongside agglomerated regions containing unreacted oxide (white bright particles). Importantly, no clear encapsulation of unreacted TeO2 within large Te crystals was observed, suggesting that the gas flow in this reactor effectively suppressed the crystal growth and entrapment mechanism reported in prior rotary kiln studies.

Figure 18.

SEM images of reaction products (a) 150×, (b) 500× magnification.

5.4. Discussion

While no prior studies have examined optimisation of TeO2 reduction reactors specifically, several gas–solid reactor design principles are well established. The present study demonstrates that a single-phase CFD approach, when combined with targeted experimentation, can effectively guide the design of a novel solid–gas reactor that combines different principles of reactors. The results confirm that deliberate modifications to gas-injection geometry, specifically the implementation of a modified gas lance with an angled, outward and downward nozzle, substantially improve gas–solid contact and accelerate reaction kinetics under atmospheric pressure by ensuring a swirling (rotational) gas flow within the chamber. Beyond validating the design, several process-level insights inform both the applicability of his reactor and directions for further development.

The improved conversion achieved with the modified lance aligns not only with enhanced gas distribution but also with the suppression of Te crystal growth. In prior rotary kiln trials, extended holding times allowed Te crystals to grow and encapsulate unreacted TeO2, physically blocking further reduction. The swirling, top-down gas injection in the present design maintains particle motion, likely limiting the available time for crystal nucleation and growth. While it remains unclear whether shear forces actively disrupt crystal formation, the observed increase in conversion at shorter holding times suggests that flow-induced particle agitation effectively delays encapsulation-related kinetic limitations. This presents a promising, non-mechanical strategy to overcome one of the key morphological limitations in TeO2 reduction.

One limitation highlighted in this work is that increased gas-flow rates, while enhancing turbulent mixing and reducing dead zones, also introduced significant cooling of the powder bed, which is an effect that ultimately dominated and reduced overall conversion at 24 L/min. This underscores a critical process trade-off between hydrodynamic optimisation and thermal stability in gas–solid reactors. For scaling or industrial translation, this implies that reactor performance cannot be maximised by flow rate alone; instead, an optimal flow window must be identified that balances gas-renewal efficiency with minimal thermal disruption. Practically, this could involve (i) compensating for cooling by elevating system set-point temperatures proportionally, or (ii) employing preheated reactant gas (i.e., preheated H2). Both strategies would require further investigation to define the operating window that truly maintains high conversion without excessive energetic drawbacks.

The design principles and optimisation methodology demonstrated here are broadly applicable to other solid–gas reduction systems. The reactor can accommodate a solid–gas system classified as cohesive or aeratable under Geldart’s classification, such as the combination of TeO2 and H2 in this study. This extends its potential use to oxides of Sn, Cu, Fe, and others, where hydrogen or other reducing gases are employed. Moreover, the absence of moving parts and the ability to operate at atmospheric pressure enhance its adaptability for exploratory and small-scale process development across metallurgical and chemical engineering contexts.

Despite the improved kinetics, complete conversion was not achieved, particularly at higher powder masses (60–100 g), where agglomeration was observed. This could be attributed primarily to inherent material cohesion, a characteristic of fine Te and TeO2, rather than a fundamental design flaw. The cylindrical geometry may further promote cohesive clustering along the chamber wall, since the inflow gas is expected to move the powders in circular motion. To overcome this, process modifications such as pulsed gas flow could be integrated to periodically disrupt agglomerates without mechanical intervention. Future iterations might also explore slight geometry adjustments (e.g., conical base or baffles) to reduce powder holdup.

The simulation conducted in this study employed a single-phase gas model, which only captured the gas-flow behaviour and did not account for gas–solid interactions. This simplification neglects the complex physics of multiphase systems, where the motion of TeO2 particles may significantly affect reaction dynamics. A more comprehensive approach would involve multiphase modelling, potentially offering insights that differ from the conclusions drawn here. Furthermore, systematic variation in the H2:H2O ratio could provide deeper insights into the role of partial pressures in controlling kinetics. Although some kinetic behaviour of the hydrogen reduction in TeO2 was briefly reported elsewhere, the precise kinetic mechanism governing this process remains an open question for further investigations. Future work should aim to determine key kinetic parameters, such as activation energy and reaction rate constants, through carefully designed experiments to track particle-size evolution, compositional gradients via high-resolution mapping, and time-resolved phase transformations.

All together, these next steps would build on the promising foundation demonstrated here, that a simple and versatile solid–gas reactor, informed by CFD and validated by experiment, could significantly improve reduction kinetics of TeO2.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to design and experimentally validate a novel gas-flow-optimised solid–gas reactor to enhance the H2 reduction in TeO2 under atmospheric pressure, addressing low conversion rates and kinetic limitations inherent in rotary kiln systems, where a previous study was conducted.

By combining single-phase CFD simulations with laboratory trials, the developed reactor is able to generate a stable swirling flow that eliminates reaction dead zones, improves local gas–solid renewal and contact, and mitigates the encapsulation of unreacted TeO2 by metallic crystal Te. The optimised reactor achieved up to 65% conversion in 1 h and 70% in 2 h at 425 °C, a marked improvement over the rotary kiln system, which required 5–6 h to reach similar conversion levels. This represents a three- to four-fold acceleration in reaction kinetics under comparable temperature conditions.

The novelty of the reactor lies in its hybrid design, which merges the operational simplicity of a fixed-bed system with the enhanced mixing of a fluidised-bed, achieved through top-down gas injection without moving parts. The configuration addresses the two key limitations identified in earlier studies: poor gas–solid contact and undesirable Te crystal growth.

Overall, this work confirms that single-phase modelling approaches can provide meaningful guidance for reactor design and process improvement, such that relatively modest modifications can significantly affect the outcome. In this case, the solid–gas reaction kinetics under atmospheric pressure have been accelerated, leading to very optimistic results for the hydrogen reduction in TeO2. These findings not only support the goals of Te recycling processes but also illustrate how accessible CFD-experiment workflows can contribute to the development of more efficient technologies in a laboratory-scale setup. Beyond this specific case, such an approach may help inspire the design of more efficient and sustainable furnace setups for metallurgical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C.; methodology, H.C. and Y.H.S.; software, Y.H.S. and M.E.; validation, H.C. and M.E.; formal analysis, H.C. and Y.H.S.; investigation, H.C.; resources, M.E., S.F. and B.F.; data curation, H.C. and Y.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, H.C. and M.E.; visualization, H.C. and Y.H.S.; supervision, M.E., S.F. and B.F.; project administration, S.F.; funding acquisition, S.F. and B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action of Germany (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz), grant number 03EN2056C.

Data Availability Statement

The exact dimensions of the modified lance in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

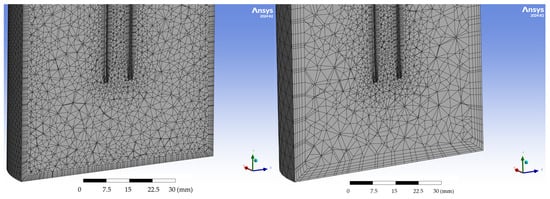

Appendix A

Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

The reaction chamber geometry was meshed using unstructured tetrahedral elements with thin boundary-layer inflation applied at walls and near the lance to better resolve near-wall velocity gradients. Four global target element sizes were tested: 5.0 mm, 2.0 mm, 1.0 mm, and 0.5 mm (compare Figure A1 and Figure A2). All meshes used identical boundary conditions, turbulence models, physical models, and solver settings to isolate the effect of grid refinement.

Figure A1.

(left): 0.5 mm mesh size; (right): 1 mm mesh size.

Figure A2.

(left): 2 mm mesh size; (right): 5 mm mesh size.

Simulations were run to steady state, and the solver convergence criterion was the ANSYS Fluent default scaled residual threshold, with additional monitoring of physically relevant probes to ensure solution stability. Thin inflation layers (Figure A3) are retained across all mesh levels to preserve consistent near-wall resolution.

Figure A3.

Inflation layers at the boundaries of the reaction chamber.

Mesh dependency was assessed by comparing flow fields, velocity contours in the reactor cross-section, and maximum velocity immediately downstream of the lance. Qualitatively, the 5 mm mesh produced a smooth, more diffused jet pattern with noticeably different jet spread and lower peak velocity than finer meshes. The 2 mm mesh improved the resolution of the jet but still showed a diffused pattern. The 1 mm and 0.5 mm meshes produced very similar flow patterns and velocity magnitudes, with only minor sharpening of gradients apparent when moving from 1 mm to 0.5 mm. Based on this consistency between the two finest meshes, the solution is considered mesh-independent within the practical accuracy required for the present design study. Consequently, the 0.5 mm mesh was chosen for the final reported simulations because it best resolved the jet impingement region while remaining feasible in terms of computational. Further refinement below 0.5 mm produced no visible changes in the flow field structure, and the residual convergence behaviour remained unchanged, indicating that the selected grid adequately resolved the relevant flow gradients.

References

- Nastac, L.; Pericleous, K.; Sabau, A.S.; Zhang, L.; Thomas, B.G. (Eds.) CFD Modeling and Simulation in Materials Processing 2018. In The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Peng, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, N. Simulation and Optimization of Furnaces and Kilns for Nonferrous Metallurgical Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraunhofer IWKS. Recycling and Long-Term Stability of Thermoelectric and Magnetocaloric Systems (RecycleTEAM). Available online: https://www.recycleteam.de/en.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Chung, H.; Friedrich, S.; Qu, M.; Friedrich, B. Hydrogen Reduction of Tellurium Oxide in a Rotary Kiln, Initial Approaches for a Sustainable Process. Crystals 2025, 15, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Friedrich, S.; Becker, J.; Friedrich, B. Purification principles and methodologies to produce high-purity tellurium. Can. Met. Q. 2024, 63, 1626–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, B.; Acikgoz, A.; Yilmaz, D.; Yalcin, S.; Dogru, K.; Yorulmaz, N. The role of TeO2 insertion on the radiation shielding, structural and physical properties of borosilicate glasses. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 563, 153619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, D.; Tian, Q.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Z. Recovery of tellurium from high tellurium-bearing materials by alkaline sulfide leaching followed by sodium sulfite precipitation. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 171, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhu, W.; Ou, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Pan, J.; Wang, R. Efficient Separation and Purification Method for Recovering Valuable Elements from Bismuth Telluride Refrigeration Chip Waste. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 39222–39232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisshion, R.J.; Patino, C. Process for the Recovery of Tellurium from Minerals and/or Acidic Solution. U.S. Patent US 2010/0326840A1, 30 December 2010. Available online: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/0e/69/f8/5688fe1a4dac75/US20100326840A1.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kur, A.; Darkwa, J.; Calautit, J.; Boukhanouf, R.; Worall, M. Solid–Gas Thermochemical Energy Storage Materials and Reactors for Low to High-Temperature Applications: A Concise Review. Energies 2023, 16, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manenti, F.; Bozzano, G. Optimal Control of Methanol Synthesis Fixed-Bed Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 13079–13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenberger, G.; Ruppel, W. Catalytic Fixed-Bed Reactors, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad, M.; Karimi, M.; Silva, J.A.C.; Rodrigues, A.E. Moving Bed Reactors: Challenges and Progress of Experimental and Theoretical Studies in a Century of Research. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 9179–9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisner, N.C.; Linder, M. A Moving Bed Reactor for Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Metal Oxides. Energies 2020, 13, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, E. Blast Furnace Definition, Temperature, Diagrams, & Facts. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/blast-furnace (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Metolina, P.; Da Silva, A.L.N.; Dixon, A.G.; Guardani, R. Multiscale modeling of non-catalytic gas-solid reactions applied to the hydrogen direct reduction of iron ore in moving-bed reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 62, 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEMENTL. Zinc Oxide EAF Steel Dust Waelz Kiln Recovery Plant. Available online: https://www.cementl.com/solution/zinc-oxide-eaf-steel-dust-waelz-kiln-recovery-plant/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- He, L.; Fan, Y.; Bellettre, J.; Yue, J.; Luo, L. A review on catalytic methane combustion at low temperatures: Catalysts, mechanisms, reaction conditions and reactor designs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metso. CircoredTM Hydrogen-Based Reduction. Available online: https://www.metso.com/portfolio/circored-hydrogen-based-reduction/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Mukherjee, S. Fluidized Bed Roasting of Zinc Sulfide Concentrate: Role of Particle Size. In Springer Proceedings in Physics, Proceedings of the International Conference on Fundamental and Industrial Research on Materials, Ropar, India, 11–14 December 2023; Tiwari, A., Ray, P.K., Sardana, N., Kumar, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; Volume 308, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldart, D. Types of gas fluidization. Powder Technol. 1973, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B.; Stewart, W.E.; Lightfoot, E.N. Transport Phenomena, 2nd ed.; Wiley International: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ferziger, J.H.; Perić, M.; Street, R.L. Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigra, Y.B.; Ghadi, A.; Bouhorma, M. A Survey of Optimization Techniques for Routing Protocols in Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. In Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation, Proceedings of NICE2020 International Conference, Heidelberg, Germany, 17–20 March 2020; Ahmed, M.B., Mellouli, S., Braganca, L., Abdelhakim, B.A., Bernadetta, K.A., Eds.; Emerging Trends in ICT for Sustainable Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastane, G.G.; Thakkar, H.; Shah, R.; Perala, S.; Raut, J.; Pandit, A.B. Single and multiphase CFD simulations for designing cavitating venturi. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 149, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L. A single-phase turbulent flow numerical simulation of a cyclonic-static micro bubble flotation column. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2012, 22, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, M.; Miskovic, S. CFD simulation of single-phase flow in flotation cells: Effect of impeller blade shape, clearance, and Reynolds number. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Remacha, M.J.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Jensen, K.F. OpenFOAM Computational Fluid Dynamic Simulations of Single-Phase Flows in an Advanced-Flow Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 7543–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M.A.; Fuentes, R.; Walsh, F.C.; Nava, J.L.; De León, C.P. Computational fluid dynamics simulations of single-phase flow in a filter-press flow reactor having a stack of three cells. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 216, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, S.V.; Spalding, D.B. A calculation procedure for heat, mass and momentum transfer in three-dimensional parabolic flows. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1972, 15, 1787–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.