Abstract

The depletion of the mineral resource base is inevitable. Therefore, it is necessary to adapt and expand the resource base by incorporating non-traditional copper sources in production. Slag samples from the Balkhash Copper Smelting Plant (Kazakhstan) were analyzed for phase composition, microstructure, and metal distribution using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and chemical and granulometric methods. The slags are characterized by a fayalite structure with a high content of FeO (35–45%) and SiO2 (25–35%). Sample composition was determined as 0.7–0.8% Cu, 0.39–0.43% Pb, 2.53% Zn, 0.075 g/t Au, and 2.6 g/t Ag. Mineralogical and granulometric analysis revealed a uniform distribution of iron and slag-forming components (SiO2, Al2O3, etc.) across the fractions. In contrast, non-ferrous and precious metals concentrated in the fine classes. Laboratory tests confirmed that the fine dissemination of valuable components led to low efficiency in magnetic and gravity separation, necessitating specific preliminary slag preparation to improve recovery. Flotation tests showed improved recovery, yielding copper concentrates with 4.57% copper content when the material was crushed to 80–90% of the −0.074 mm class. The research creates a basis for the development of environmentally safe and resource-saving technologies and provides initial data for future recovery technologies.

1. Introduction

Copper is one of the key non-ferrous metals in modern industry. In recent decades, there has been a stable trend towards a decline in the copper content in mined ores and a reduction in the number of newly explored deposits. In the 19th century, the average copper content in ores reached 8–10%. By the early 20th century, it was about 4%, which decreased further to 1–1.2% by the 1980s. By the beginning of the 21st century, the average content was 0.6–0.8%. According to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG), the weighted average copper content in global mining in 2022 was only 0.52% [1]. Simultaneously, global demand for copper has continued to grow due to the development of high-tech industries and the transition to low-carbon energy. According to forecasts from the International Energy Agency (IEA), a copper deficit of up to 30% is expected by 2035, driven by the decline in the quality of mined ores and the insufficient pace of new deposit discoveries [2].

Against the backdrop of this global trend, analogous processes are observed in Kazakhstan. Copper production occupies a leading position in the structure of non-ferrous metallurgy in Kazakhstan, accounting for extensive copper reserves (more than 35 million tons in the region), which represents 4.7% of world reserves and places Kazakhstan at sixth globally after Chile, Australia, Peru, Mexico, and the USA. The main deposits are concentrated in Central and Eastern Kazakhstan, and are predominantly of the copper-porphyry type with low metal content in the ore [3].

The decline in the quality of the mineral resource base means that it is now necessary to process increasingly large volumes of rock mass to obtain a comparable amount of copper. This is accompanied by changes in technological parameters of smelting, flux composition, and the ratio of raw components. Consequently, the chemical and mineralogical composition of slags and the distribution of valuable elements within them change, requiring regular updating of data on the metal content in smelting products. Changes in the composition of the initial raw materials and technological regimes often lead to the accumulation of magnetite in the slag, impaired matte separation, and increased copper losses. The study in [4] proved that when the copper content in the charge decreases by half, the quantity of waste slags increases 1.5–2 times, thereby increasing copper losses with the slag.

Long-term consequences of these processes include increased energy intensity of production, increased volumes of waste and slags, and enhanced anthropogenic impact on the environment. In addition to the negative environmental impact, prolonged storage of slag in open conditions contributes to the leaching of valuable components and the formation of an oxide film on its surface, even leading to the loss of chemically stable elements such as gold. Under these conditions, the comprehensive utilization of mineral and technogenic resources, including the processing of metallurgical slags as an alternative source of secondary raw materials, becomes a strategic direction. A literature review [5] of known methods for processing copper smelting slags showed that, despite a number of technologies implemented in the practice of copper smelters, the problem of utilizing huge reserves of slags, both domestically and abroad, remains unresolved from an economic and environmental efficiency standpoint.

In recent years, interest in studying copper smelting slags as a source of secondary metals and an object of resource conservation has been growing both in Kazakhstan and worldwide [6,7,8,9,10,11]. A number of domestic studies confirm the possibility of effective extraction of copper and zinc from slags using various hydrometallurgical approaches. For example, the work in [12] showed that recovery reaches 60–70% Cu during ammonia leaching of copper slags. Meanwhile, another technology [13] demonstrated the efficiency of sulfuric acid leaching in aqueous and aqueous-alcoholic environments with recovery up to 90% Zn. Finally, the authors in [14] investigated the use of sulfuric acid combined with optimization of leaching parameters for industrial slags from the Balkhash Copper Smelting Plant, achieving recovery up to 76% Cu, 94% Zn, and 92% Fe in the form of oxides.

The reviewed hydrometallurgical methods exhibit both significant advantages and inherent limitations. Ammonia leaching is characterized by high selectivity toward copper-bearing phases and relatively low dissolution of iron, which simplifies downstream solution purification and reduces reagent consumption. This approach is particularly effective for slags containing copper in oxidized or easily complexed forms. However, its main limitations include moderate overall copper recovery (typically not exceeding 60–70%), sensitivity to the mineralogical form of copper, and the need for strict control of solution chemistry, including ammonia concentration and pH, to prevent reagent losses and volatilization.

Sulfuric acid leaching demonstrates higher extraction efficiencies for zinc and, in some cases, copper, especially when aggressive leaching conditions are applied. Its advantages include wide industrial applicability, relatively low reagent cost, and the ability to process large volumes of material. At the same time, sulfuric acid leaching is often accompanied by non-selective dissolution of iron and other gangue elements, leading to increased acid consumption and more complex purification of pregnant leach solutions. In addition, the formation of silica gel during leaching of silicate-rich slags can hinder solid–liquid separation and negatively affect process operability.

The combined or optimized approaches reported in the literature—such as parameter optimization, staged leaching, or preliminary beneficiation—allow for partial mitigation of these drawbacks. Nevertheless, the cited studies indicate that no single hydrometallurgical method provides both high selectivity and high recovery across all slag types, highlighting the need for integrated processing routes tailored to the specific physicochemical properties of the slags.

These results confirm the feasibility of further study of the composition and properties of Kazakhstan slags for developing effective processing technologies. Copper smelting slags are complex polymineral systems, consisting mainly of fayalite, magnetite, iron silicates, and a glassy phase, and also containing dispersed inclusions of sulfide and metallic phases of copper, zinc, lead, nickel, and other elements. It is estimated that the residual copper content in the dump slags of domestic enterprises can reach at least 0.8–1.0%. Consequently, slags represent not only an environmental problem but also significant potential for the secondary recovery of metals that remain in them.

This work investigates the possibility of processing copper smelting slags generated at the Balkhash Copper Smelting Plant in Kazakhstan. The Balkhash Mining and Metallurgical Combine has been operating since 1938 and uses autogenous smelting in Vanyukov furnaces. Currently, the processing of slags is carried out by flotation at concentration plants, independently, without mixing with ore. However, such methods do not solve the problem of slag utilization: significant volumes of artificial raw materials containing elevated concentrations of valuable components remain unrecycled and accumulate in dumps.

Thus, in the context of declining ore quality, rising production costs, and environmental restrictions, a comprehensive study of the chemical and mineralogical composition of copper smelting slags is a relevant task. This will allow for the optimization of existing processing technologies and the development of new methods for the effective recovery of valuable components, contributing to improved resource efficiency and environmental safety of metallurgical production. The implementation of processing technologies represents a complex and laborious task. This work constitutes the first stage of a comprehensive research project aimed at developing a new electrochemical technology [15] for extracting valuable components from copper smelting slag. The main focus is on studying the physicochemical and mineralogical characteristics of copper smelting slags in Kazakhstan and assessing their potential for preliminary concentration. The data obtained will be used in subsequent experiments on electrochlorination and for comparative analysis of the effectiveness of valuable component recovery methods. The results of this study create a scientific basis for developing new methods for processing technogenic waste from non-ferrous metallurgy, optimizing hydrometallurgical technologies, and increasing the efficiency of valuable component recovery from copper smelting slags.

2. Materials and Methods

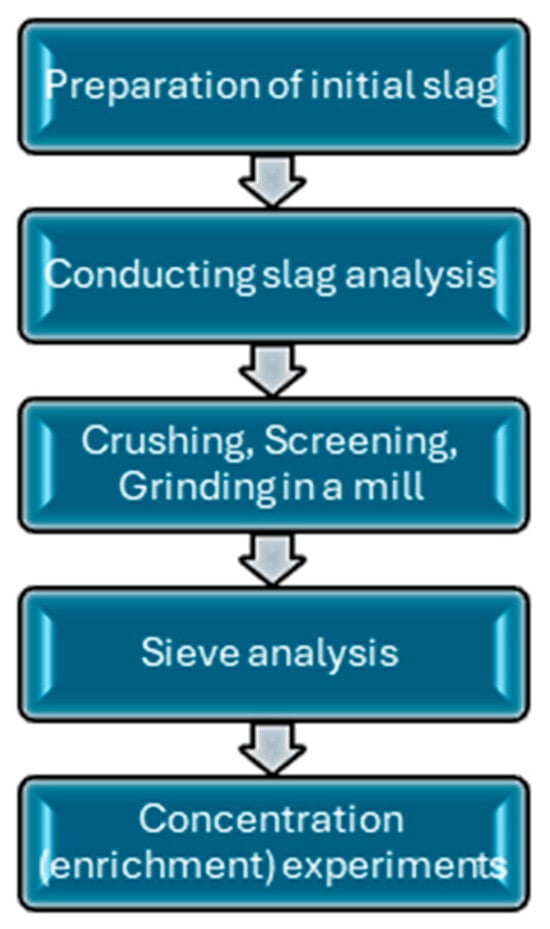

Samples of copper smelting slags taken at the Balkhash Copper Smelting Plant of Kazakhmys Smelting LLP in Kazakhstan were used as research objects. Sampling included both fresh slags supplied directly from the smelting units and materials from slag dumps of various storage durations. Average samples, obtained after quartering and subsequent grinding to a fraction smaller than 0.1 mm, were used for analysis. The studies and experiments were carried out at the laboratories of the Eastern Scientific Research Mining and Metallurgical Institute of Non-ferrous Metals “VNIItsvetmet”, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan. The results of the conducted studies were evaluated based on the residual content of valuable components in the tails. The principal scheme of the experiments is shown in Figure 1. The reliability of the experimental data was ensured through repeated tests conducted under identical operating conditions. Each experiment was performed in duplicate or triplicate, and the reported grade and recovery values represent the arithmetic mean of the obtained results. The relative deviation between parallel tests did not exceed 3%.

Figure 1.

Principle scheme of research.

2.1. Mineralogical Analysis

The phase composition of the slags was studied via X-ray phase analysis (XRD) using a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). X-ray diffraction data were processed using the universal DIFFRAC.EVA V7 software package. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on an OLYMPUS BX 51 Pol. (OLYMPUS Co., Tokyo, Japan) microscope, utilizing a SIMAGIS 2P-2C video camera (SIAMS, Yekaterinburg, Russia) and Mineral C-7 analyzer (SIAMS, Yekaterinburg, Russia), was used to study the microstructure and morphology. Phase identification was based primarily on XRD and SEM observations provide supporting microstructural evidence. The obtained spectra allowed for the determination of elemental distribution across phases and the assessment of the degree of dissemination of sulfide and metallic inclusions.

Phase and physicochemical analysis of the slags was performed using sequential selective dissolution, the choice of reagents for which was determined by the results of preliminary microscopic examination. Crushed samples were boiled in an acetic acid solution to destroy the silicate matrix and dissolve the available forms of copper. After filtration, the solid residue was treated with a thiocarbamide solution in the presence of hydrochloric acid to dissolve the sulfide phases. The final stage involved treatment with a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid to oxidize and dissolve poorly soluble compounds. After each stage, filtration was performed to separate the liquid and solid phases for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Chemical and Granulometric Analysis

Granulometric (sieve) analysis of the slag samples was carried out to determine the particle size distribution. The analysis was performed by dry sieving using a standard set of sieves. The chemical composition of the studied samples was determined using a combination of instrumental analytical methods. Elemental concentrations were measured via mass spectrometric and atomic absorption techniques using PinAAcle 500 and AAnalyst 400 spectrometers (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), as well as via atomic emission spectrometry with the DFS-8-3 system equipped with a MAES analyzer (AVISMA, Berezniki, Russia). Carbon and sulfur contents were determined using an ELEMENTRAC CS-i analyzer (ELTRA, Haan, Germany). Each fraction was subjected to separate chemical analysis to determine the content of the main components.

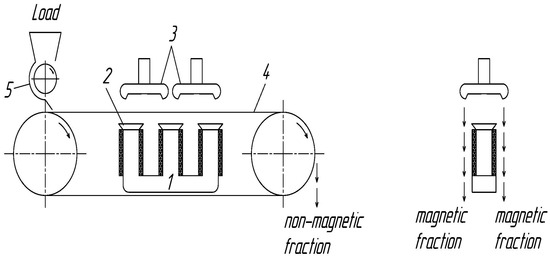

2.3. Magnetic Concentration

Magnetic separation tests were conducted using a Rapid 120-T electromagnetic dry belt–disk separator (Rapid Magnetting Machine Co. Ltd., Birmingham, UK). The general view of the experimental apparatus is depicted in Figure 2. The separator disks, with a diameter greater than the width of the conveyor belt, are provided with sharpened teeth to enhance the magnetic field intensity above the belt. The distance between the disks and the conveyor belt, as well as the inclination angle of the disks, can be adjusted.

Figure 2.

Electromagnetic tape disk separator comprises an electromagnetic system (1) equipped with three poles (2), two iron disks (3), an endless rubber belt (4), and a material feeding unit (5).

Separation was performed sequentially by increasing the magnetic field intensity from 500 Oe to 800 Oe, 1000 Oe, and higher values. When no magnetic product was recovered at a given magnetic field intensity, the corresponding fraction was not reported. The separator was operated at a belt rotation speed of 2 rpm, with a 5 mm adjustable gap between the belt and the magnetic disks. The throughput under the selected operating conditions ranged 7 kg h−1.

2.4. Gravity Concentration

Technological tests on concentration in suspensions were carried out using a device for fractionating ore in heavy suspensions. For tests under static conditions, the suspension was prepared from granular ferrosilicon. Ferrosilicon-grade FS15G produced by the Aktobe Ferroalloys Plant (Aktobe, Kazakhstan), containing 15% silicon, is widely used for suspension preparation and possesses the necessary rheological parameters.

The technology for preparing the working suspension is similar in all cases. When separating coarse ores in heavy suspensions under static conditions, the highest technological indicators are obtained when using granular ferrosilicon of the −0.044 mm class, since with a coarser weighting agent, the suspension quickly stratifies at usual densities for removing gangue (2.6–2.7 g/cm3).

The variation in suspension viscosity as a function of density is presented in Table 1. If no material was recovered at a given suspension density, the corresponding data are not included in the table.

Table 1.

Viscosity of ferrosilicon suspension.

To verify the reliability of the heavy suspension concentration results, tests were carried out on slag stratification in heavy liquids. The heavy liquid used was GPS-V, a ready-to-use aqueous solution of sodium (magnesium) heteropolyoxotungstate, with the formula Mg(5−x)Nax[Si(B)W18Oy]-nH2O and an actual liquid density of 3.00 g/cm3.

2.5. Jigging

Jigging was conducted using a bed made of the heavy fraction of the investigated slag of −5 + 3 mm particle size, with a bed thickness of 15 mm, screen with 3.2 mm holes, water consumption: 163.2 L/h in the 1st chamber and 97.2 L/h in the 2nd chamber, amplitude 3 mm at a frequency of 780 rpm, and capacity of 13.5 kg/h based on initial material.

2.6. Concentration on a Concentrating Table

A series of experiments was conducted on the concentration of initial slag samples on a concentrating table when ground to different sizes—up to 40%, 60%, and 80% content of the −0.074 mm class. Key parameters were a deck inclination angle of 2.5°, deck stroke length of 5 mm, oscillation frequency of 600 rpm, and water consumption of 102 L/h. Gravity concentration tests were performed using a laboratory concentration table SKL-2 (Geopribor Experimental Plant, Moscow, Russia).

2.7. Flotation

Flotation tests began with the preparation of the slags, grinding them to different sizes, and flotation under the same conditions to determine the optimal grinding size.

Technological tests were carried out to determine the relative grindability of the slags relative to a reference ore. A ball mill with a rotating axis measuring 250 × 150 mm was used for this, with a Solid/Liquid/Ball (S:L:B) ratio of 1:0.7 L:12 kg. The weight of the sample was 1 kg dry weight, and it had a pulp density of 62% solids in the operating mill. The working volume of the mill was 8 L. Determination of relative grindability was reduced to grinding the compared materials under identical conditions for different grinding times, with determination of the sieve characteristic each time, up to the required yield of the −0.074 mm class: 62.0%, 71.0%, 80.0%, and 90.0%. Flotation experiments were conducted using standard laboratory flotation machines (models 237FL-A and 240FL-A, Dnepropetrovsk Mining Machinery Plant, Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine).

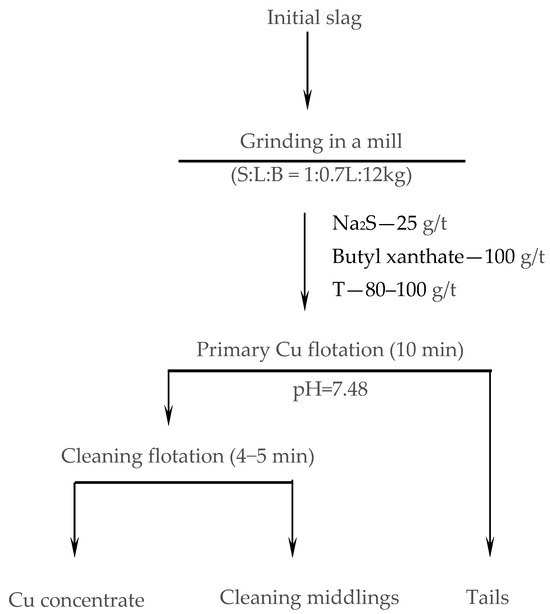

Flotation tests were carried out on the ground materials according to the scheme and parameters shown in Figure 3 and Table 2, using butyl xanthate as the collector, Na2S as the activator, and T-80 as the frother. Special open test experiments were conducted to assess the effect of slag particle size on flotation performance.

Figure 3.

Scheme and operating conditions of flotation tests.

Table 2.

Flotation conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Mineralogical Analysis

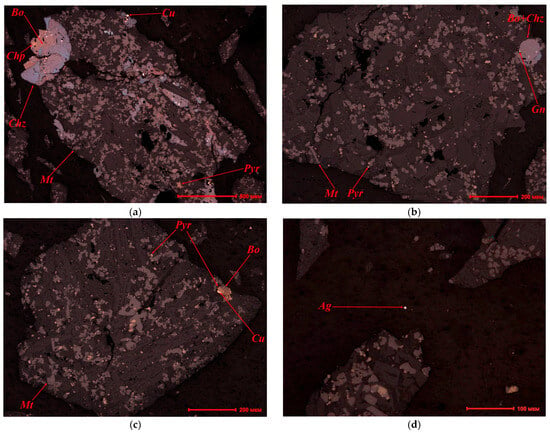

Mineralogical analysis revealed that the granulated slag consists of aggregates of sulfide phases, including solid solutions of chalcopyrite with secondary copper minerals (bornite and chalcocite). Pyrrhotite was also detected in the composition, and the magnetite content reached 25% (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

SEM microphotograph of slag: (a) Bornite (Bo) grains contain complex solid solution structures composed of chalcopyrite (Chp). Bornite (Bo) in turn is partially replaced by chalcocite (Chz). Grains of pyrrhotite (Pyr) and magnetite (Mt), and veins and beads of metallic copper. (b) Unevenly disseminated structure of magnetite (Mt) with inclusions of pyrrhotite (Pyr). Rare beads of copper sulfide solid solution, galena (Gn) and chalcocite (Chz). (c) Pyrrhotite (Pyr) beads in slag and magnetite (Mt) crystals. Pyrrhotite (Pyr) intergrown with bornite (Bo) and metallic copper (Cu). (d) Metallic silver (Ag).

Sulfide droplets contain inclusions of metallic copper in the form of beads measuring 0.005–0.025 mm. Veins of metallic copper measuring 0.003–0.005–0.025 mm were also observed. Furthermore, inclusions of native silver measuring up to 0.006 mm (Figure 4d) were detected.

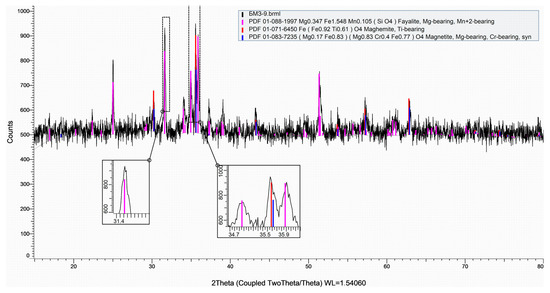

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern indicates that the investigated copper smelting slag is dominated by fayalitic and iron oxide phases, which is characteristic of fayalite-type copper slags. The main crystalline phases identified include fayalite (Fe2SiO4) with partial substitution by Mg and Mn, as well as magnetite (Fe3O4) with minor Ti- and Cr-bearing solid solutions. The diffractogram of the slag samples is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diffractogram of slag samples.

The most intense reflections observed in the range of approximately 30–36° 2θ correspond to overlapping peaks of fayalite and magnetite, reflecting their coexistence and close structural relationship. Enlarged insets in this angular region highlight the peak overlap and confirm the presence of multiple crystalline contributions rather than a single phase. Minor peak shifts and peak broadening are attributed to isomorphic substitutions (Mg2+, Mn2+, Ti4+, Cr3+) within the crystal lattices, which is typical for industrial copper smelting slags.

In addition to the sharp diffraction peaks, the pattern exhibits a broad diffuse background over the low-angle region, indicating the presence of a glassy or amorphous silicate component. This amorphous fraction is commonly formed during rapid cooling of the slag and does not produce distinct diffraction peaks. Its presence complicates extraction, as valuable metal-containing inclusions are often encapsulated in a glassy–fayalite matrix.

The results of the chemical phase analysis of copper slag are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of chemical phase analysis of slag.

3.2. Chemical and Granulometric Analysis

Table 4 presents the results of fractional analysis of initial copper smelting slag samples by size classes from −2 + 1 mm to −0.044 mm. The total sample weight was 10,264.4 g. The most abundant classes are medium-grained classes (−2 + 1 mm—57.9%, −1 + 0.5 mm—26.8%), jointly constituting over 84% of the entire sample mass. Fine-grained classes (−0.1 mm and finer) account for less than 5%, which indicates a relatively coarse-grained structure of the slag and the necessity of grinding for the complete liberation of sulfide phases.

Table 4.

Composition and distribution of valuable components in initial slag samples (major elements expressed in wt.% and trace/precious metals in g/t).

The copper content gradually increases from 0.72% in the coarse fraction (−2 + 1 mm) to 0.89% in the finest (−0.044 mm). A trend is observed: copper is higher in the fine fractions. This is typical for slags with finely dispersed inclusions of sulfides and metallic copper encased in a silicate matrix. Thus, decreasing the particle size promotes the liberation of copper-containing phases, confirming the necessity of fine grinding before processing. Lead (Pb) fluctuates insignificantly (0.39–0.43%), without a pronounced dependence on particle size. Zinc (Zn) slightly decreases from 2.53% (−0.5 mm) to 2.30% (−0.044 mm), which may be associated with the presence of zinc in more stable silicate phases (willemite Zn2SiO4), which react poorly to grinding. Iron (Fe) is stable at about 40%, consistent with the predominance of fayalite and magnetite in the slag composition. Silica (SiO2) varies between 25.6 and 27.5%, confirming the homogeneity of the silicate matrix. Total sulfur (Stotal) slightly decreases with particle size. Gold (Au) and silver (Ag) show a tendency towards enrichment in the fine fractions: Au increases from 0.05 to 0.22 g/t, and Ag—from 2.5 to 4.2 g/t. This suggests the concomitant migration of precious metals with copper-containing phases and their finer distribution. The data obtained confirm that the efficiency of copper extraction from slags directly depends on the degree of grinding and the liberation of inclusions.

3.3. Magnetic Concentration

From the results of magnetic separation of slag samples presented in Table 5, it follows that the concentration efficiency is very low (as there is no tailing product) and magnetic separation cannot be recommended for the pre-concentration of slags. This was also confirmed in an earlier study [16], where magnetic separation was attempted to extract iron from copper slag flotation tails. Unfortunately, the iron content in the magnetic products and the iron recovery by magnetic separation are relatively low, only 52.21% and 38.09%, respectively, because iron is mainly present in the form of fayalite (Fe2SiO4). Only with a specific preliminary preparation of copper slags before magnetic separation, as in [17], was a total recovery of iron and copper of 90.49% and 79.53%, respectively, achieved.

Table 5.

Results of dry magnetic separation.

3.4. Gravity Concentration

As demonstrated by the data in Table 6, the fractionation of slag in heavy suspensions, even under favorable laboratory conditions, does not provide a noticeable increase in concentration efficiency. The content of elements in the heavy fraction remains at the level of the initial material, which suggests the impracticality of applying this method for slag processing. To assess the reliability of the obtained results, supplementary studies were conducted regarding the stratification/separation of slags in heavy liquids. The results of technological tests on the copper smelting slag, presented in Table 7, confirm the conclusions drawn from the use of heavy suspensions (Table 6). The yield of the light fraction at a density of 3.0 g/cm3 was extremely low, consisting mainly of coke fines. Consequently, the test results confirm the low efficiency of slag concentration methods utilizing heavy suspensions and liquids.

Table 6.

Results of enrichment in heavy suspensions.

Table 7.

Results of enrichment in heavy liquid.

3.5. Jigging and Concentration Table Enrichment

In current industrial operations processing copper smelting slag at the Balkhash Concentrating Plant, the copper content in the flotation tails is 0.26%. In the conducted experimental studies, after material separation on the concentration table, the copper content reached 0.77–0.78% (Table 8), which is approximately three times higher than the industrial indicator. This indicates the ineffectiveness of using shaking tables under these technological conditions. Even less satisfactory results were obtained during jigging: the copper content in the tails increased to 0.91% (Table 9).

Table 8.

Results of concentration table enrichment.

Table 9.

Results of enrichment by jigging.

This observed pattern is due to the specific distribution of valuable components during the crushing and grinding of slags. Non-ferrous and noble metals primarily transition into the fine size fractions, while iron, along with components present in higher concentrations (SiO2, Al2O3, etc.), remain more uniformly distributed or concentrate in the coarse size fractions. Consequently, a component redistribution unfavorable for gravity and magnetic methods is observed: the content of non-ferrous and noble metals increases in the fine size fractions, whereas iron and slag-forming minerals dominate the coarse fractions. This reduces the efficiency of gravity and magnetic concentration methods but creates more favorable conditions for flotation. The additional effect of flotation reagents also contributes to increased recovery of fine non-ferrous metal particles (see Table 10 regarding copper distribution by size fraction during grinding).

Table 10.

Content of valuable components in slag depending on grinding time.

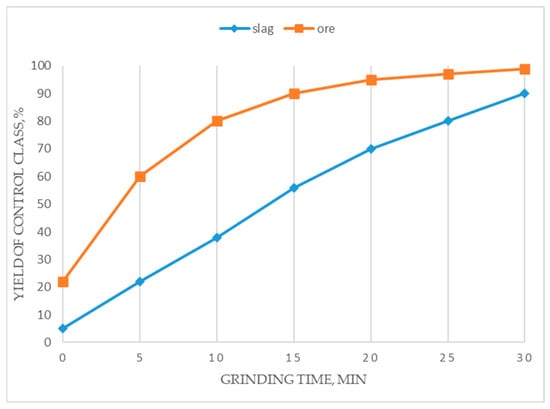

From the data in Figure 6, it is evident that, to achieve a fineness of 80% passing the −0.074 mm class, the required grinding duration for the reference ore is 10 min, whereas for copper smelting slags, it is approximately 25 min, i.e., 2.5 times longer. This points to the higher mechanical strength and resistance to grinding of the slags compared to the ore, which is attributed to their glassy structure and the presence of robust minerals within the slag aggregate. This must be taken into account when designing technological flowsheets and evaluating economic factors.

Figure 6.

The grindability of slag sample compared to ore.

3.6. Flotation

According to Table 11, the optimum copper content (4.57% Cu) was achieved in Experiment 3 (80.0% of the −0.074 mm class). Further grinding (Experiment 4, 90.0% fineness) improved the concentrate yield but decreased the quality to 3.50% Cu. Conversely, copper losses in the tailings consistently dropped with increased fineness, reaching a minimum of 0.40% Cu in Experiment 4, indicating enhanced mineral liberation.

Table 11.

Results of flotation experiments.

The concentrations of gold (0.670 g/t) and silver (15.30 g/t) also peaked in Experiment 3, correlating with copper recovery. The high iron content in the tailings (39.8–40.1%) remained constant across all tests, which is typical for copper slag flotation. Overall, a grinding time of 24 min (Experiment 3) provides the best concentrate quality for Cu, Au, and Ag, while extended grinding (30 min) maximizes copper recovery but compromises concentrate grade.

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Limiting the Efficiency of Physical Beneficiation of Copper Smelting Slags

The limited efficiency of magnetic and gravitational separation observed in this study can be explained by a combination of unfavorable physical and mineralogical factors inherent to copper smelting slags, including density contrast, magnetic susceptibility, and the degree of liberation.

First, gravitational separation is constrained by an insufficient density contrast between copper-bearing phases and the dominant silicate matrix. Mineralogical analysis shows that copper is mainly present as finely disseminated sulfide inclusions encapsulated within fayalitic and glassy silicate phases. Consequently, the effective density of composite particles approaches that of the slag-forming minerals, reducing the settling velocity differences required for efficient gravity separation. Fayalite (Fe2SiO4) is a thermodynamically stable main phase of copper smelting slags in the FeO–SiO2 system under pyrometallurgical smelting conditions. In the presence of Cu2O and a limited amount of sulfur, copper does not form its own stable silicate phase, but is predominantly distributed among sulfide inclusions, metallic copper, and oxide forms localized in the glassy or crystalline fayalite matrix. In the FeO–SiO2–Cu2O system, copper is characterized by low solubility in fayalite, leading to the formation of finely dispersed copper-bearing inclusions and interphase aggregates that persist during slag cooling. The high thermodynamic and structural stability of the fayalite matrix determines its low susceptibility to mechanical degradation, significantly limiting the effectiveness of physical separation methods.

Second, the performance of magnetic separation is limited by the low magnetic susceptibility of iron-bearing silicates compared to strongly magnetic phases such as magnetite. In the investigated slags, iron predominantly occurs in fayalite and complex silicate solid solutions exhibiting weak paramagnetic behavior, resulting in poor response to moderate magnetic field intensities and limited separation selectivity.

Third, the degree of liberation plays a decisive role and was explicitly examined in this study through experiments conducted at different levels of grinding fineness. Although increased comminution enhances copper exposure, the results indicate that, even at finer particle sizes, a significant portion of copper remains locked within composite silicate particles. Moreover, under industrial conditions, further size reduction beyond the tested fineness is either technically impractical or associated with disproportionately high energy consumption and operating costs. Therefore, ultra-fine grinding was not considered a viable option within the scope of this study.

The obtained results showed that the high stability of fayalite in the FeO–SiO2–Cu2O system and the finely dispersed nature of copper-containing inclusions significantly reduce the efficiency of physical separation, which confirms the need to move to more selective chemical or electrochemical processing methods based on the phase and thermodynamic specifics of the slag.

4.2. Recommended Processing Routes for the Recovery of Valuable Metals in the Slag

Flotation remains the most widely applied physical method for recovering copper from smelting slags and is currently employed at several industrial operations worldwide. The efficiency of flotation is primarily controlled by the degree of liberation of copper-bearing phases, which in turn depends on slag structure and cooling history. The optimum grinding fineness identified in this study (80.0% −0.074 mm) is consistent with results reported for fayalitic copper smelting slags worldwide. Several studies indicate that effective flotation is typically achieved at grinding finenesses in the range of 70–90% passing 0.074 mm, representing a compromise between sufficient phase liberation and the onset of overgrinding effects [7,18,19]. Similar grinding targets (up to 90% −0.074 mm) have been applied in laboratory and semi-industrial investigations, particularly for slags with finely disseminated copper inclusions embedded in a fayalitic or partially glassy matrix [18,20]. At the same time, more refractory or rapidly cooled slags often require finer or multi-stage grinding, albeit at the expense of increased energy consumption and slime generation [7,21].

Zinc and a significant fraction of lead in copper smelting slags are predominantly present in highly stable and chemically resistant phases dispersed within the fayalitic matrix. This mineralogical form renders zinc recovery via physical beneficiation ineffective, regardless of grinding intensity. Consequently, zinc and lead recovery requires chemical or thermochemical processing routes, such as reduction with solid carbon followed by fuming at temperatures exceeding the slag melting point [22], or high-temperature roasting with additives including ferric sulfate, pyrite, or calcium chloride [23,24,25].

Alternatively, hydrometallurgical approaches have been shown to be effective. Ammonium chloride leaching demonstrates high recovery of zinc, copper, and iron into solution [26], while alkaline leaching systems have also been successfully applied [27]. Alkaline leaching offers the additional advantages of minimizing iron dissolution and preventing silica gel formation, which commonly occur in acidic leaching environments.

Based on the mineralogical characteristics and experimental data obtained in this study, a differentiated processing strategy for copper smelting slags is recommended. For slags exhibiting sufficient liberation potential of copper-bearing phases, copper recovery should be carried out through controlled grinding followed by flotation. At the same time, for the comprehensive recovery of valuable components from slags characterized by a high degree of phase intergrowth, the application of chemical or electrochemical methods capable of effectively disrupting the fayalitic silicate matrix is recommended. Such an integrated approach provides an optimal balance between metallurgical efficiency, economic feasibility, and environmental considerations, enabling the rational utilization of copper smelting slags as secondary raw materials.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides a comprehensive evaluation of copper smelting slag processing based on detailed mineralogical characterization and experimental beneficiation tests. The experimental results confirm a key conclusion widely reported in the literature: conventional physical separation methods are inherently limited in their ability to liberate and recover valuable metals from refractory slag matrices. Flotation remains the only physical method capable of producing a copper-enriched concentrate and is widely applied in industrial practice; however, its efficiency is strongly constrained by the degree of phase liberation and slag texture.

An effective particle size distribution for achieving optimum copper recovery was identified, corresponding to approximately 80.0% of the material in the −0.074 mm size fraction. The results demonstrate that controlled grinding should be optimized based on mineral liberation rather than indiscriminate particle size reduction. Further grinding beyond this optimum does not result in proportional improvements in copper recovery but instead leads to increased energy consumption and the generation of fine slimes, which negatively affect both flotation performance and the efficiency of subsequent hydrometallurgical leaching.

The development of processing technologies must therefore be guided by mineralogical considerations. At the pre-treatment stage, priority should be given to improving phase liberation efficiency rather than simply reducing particle size.

Prior to hydrometallurgical extraction, pre-treatment methods aimed at disrupting the slag matrix are required. These include thermochemical pre-treatments, such as reduction roasting with Na2SO4 or carbon and partial chlorination, as well as chemical conditioning techniques (e.g., sulfidization and surface activation), which enhance flotation selectivity and may improve the liberation of target phases prior to leaching.

The transition toward combined processing routes is supported by numerous recent studies and is recommended for the development of slag processing technologies.

Such approaches are considered a promising direction for the development of environmentally safe and resource-saving technologies to enable comprehensive utilization of copper smelting slags.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K.; investigation, D.K.; formal analysis, D.K. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K.; visualization, D.K.; supervision, D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP25796667).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Eastern Mining and Metallurgical Research Institute for Non-ferrous Metals “VNIItsvetmet”, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan, for their valuable assistance and technical support provided during the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Icsg Copper Bulletin. Available online: https://icsg.org/publications-list/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- IEA. Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025. IEA, Paris. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2025 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Non-Ferrous Metals in Kazakhstan: Current State and Prospects. Available online: https://geoportal-kz.org/non-ferrous-metals/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Kenzhaliyev, B.; Kvyatkovskiy, S.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Sokolovskaya, L.V.; Semenova, A.S. Deparation of dump slags at the Balkhash copper smelting plant. Kompleks. Ispolz. Miner. Syra Complex Use Miner. Resour. 2018, 306, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmangaliyev, D.; Abdulina, S.; Mamyachenkov, S. Promising methods for hydrometallurgical processing of copper slag. Kompleks. Ispolz. Miner. Syra Complex Use Miner. Resour. 2022, 323, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Tan, K.; Zhao, B.; Xie, S. Recovery of Cu-Fe Alloy from Copper Smelting Slag. Metals 2023, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, L.; Tapia, J.; Pavez, O.; Santander, M.; Rivera, V.; Gonzalez, M. Recovery of Copper from Slags Through Flotation at the Hernán Videla Lira Smelter. Minerals 2024, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinomwa, G.; Mapani, B.; Nghipulile, T.; Maweja, K.; Kurasha, J.T.; Amwaama, M.; Chigayo, K. Mineralogical Characterization of Historic Copper Slag to Guide the Recovery of Valuable Metals: A Namibian Case Study. Materials 2023, 16, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, T.C.; Singh, P.; Nikoloski, A.N. Mineralogical Characterisation of Copper Slag and Phase Transformation after Carbocatalytic Reduction for Hydrometallurgical Extraction of Copper and Cobalt. Metals 2024, 14, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, S.M.; Bafti, B.S.; Yarahmadi, M.R.; Maymand, M.M.; Khorasani, J.K. Mineralogical Properties of the Copper Slags from the SarCheshmeh Smelter Plant, Iran, in View of Value Recovery. Minerals 2022, 12, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayitov, S.S.; Tsoi, V.D.; Rasulov, S.H.M.; Pechersky, R.D.; Rasulova, A.V.; Abduvaitov, A.K.; Asrorov, A.A. Material composition of copper slag of the Almalyk copper-smelting plant (Uzbekistan). Bull. Tomsk. Polytech. Univ. Geo Assets Eng. 2024, 335, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadirov, R.K.; Turan, M.D.; Karamyrzayev, G.A. Copper Ammonia Leaching from Smelter Slag. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 12, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M.D.; Karamyrzayev, G.; Nadirov, R. Recovery of zinc from copper smelter slag by sulfuric acid leaching in an aqueous and alcoholic environment. Chem. Bull. Kazakh Natl. Univ. 2021, 103, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimbetov, B.S.; Moldabayeva, G.Z.; Taimassova, A.N.; Kunilova, I.V. Processing of copper smelting slag using sulfuric acid leaching: Technological aspects and solutions. Rudomet J. 2025, 1, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmangaliyev, D.B.; Abdulina, S.A.; Krykpaeva, A.A.; Mamyachenkov, S.V. A Method for Extracting Valuable Components from Copper Smelter Slag. Bull. D. Serikbayev EKTU 2023, 3, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiao, K. The research on using dispersant agent to lron recovery in copper slag. Nonferr. Met. Sci. Eng. 2011, 6, 71–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.L.; Zhu, D.Q.; Pan, J.; Wu, T.J. Utilization of waste copper slag to produce directly reduced iron for weathering resistant steel. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Han, B.; Ren, S.P.; Yang, B. Recovery of Copper from Copper Smelter Slag by Flotation. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 496–500, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Kang, D.; Chen, J.H. Flotation Behavior of Smelting Abandoned Copper Slags. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 734–737, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štirbanović, Z.; Urošević, D.; Đorđević, M.; Sokolović, J.; Aksić, N.; Živadinović, N.; Milutinović, S. Application of Thionocarbamates in Copper Slag Flotation. Metals 2022, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, Z.; Pan, J.; Zhu, D.; Dong, T.; Lu, S. Stepwise Utilization Process to Recover Valuable Components from Copper Slag. Minerals 2021, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.G.; Prabhu, V.L.; Mantha, D. Zinc Fuming from Lead Blast Furnace Slag. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2002, 21, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altundoǧan, H.S.; Tümen, F. Metal recovery from copper converter slag by roasting with ferric sulphate. Hydrometallurgy 1997, 44, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümen, F.; Bailey, N.T. Recovery of metal values from copper smelter slags by roasting with pyrite. Hydrometallurgy 1990, 25, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Tian, Q. Recovery of Zinc and Lead from Copper Smelting Slags by Chlorination Roasting. JOM 2021, 73, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadirov, R.K.; Syzdykova, L.I.; Zhussupova, A.K.; Usserbaev, M.T. Recovery of value metals from copper smelter slag by ammonium chloride treatment. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2013, 124, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwamba, M.; Ito, M.; Hiroyoshi, N.; Tabelin, C.B.; Hashizume, R.; Fukushima, T.; Park, I.; Jeon, S.; Igarashi, T.; Sato, T.; et al. Alkaline Leaching and Concurrent Cementation of Dissolved Pb and Zn from Zinc Plant Leach Residues. Minerals 2022, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.