Hydraulic Performance of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Amended Bentonite in Vertical Cutoff Walls for Containing Acid Mine Drainage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NaB and Na-CMC

2.2. Synthesis of Na-CMC Amended Bentonite

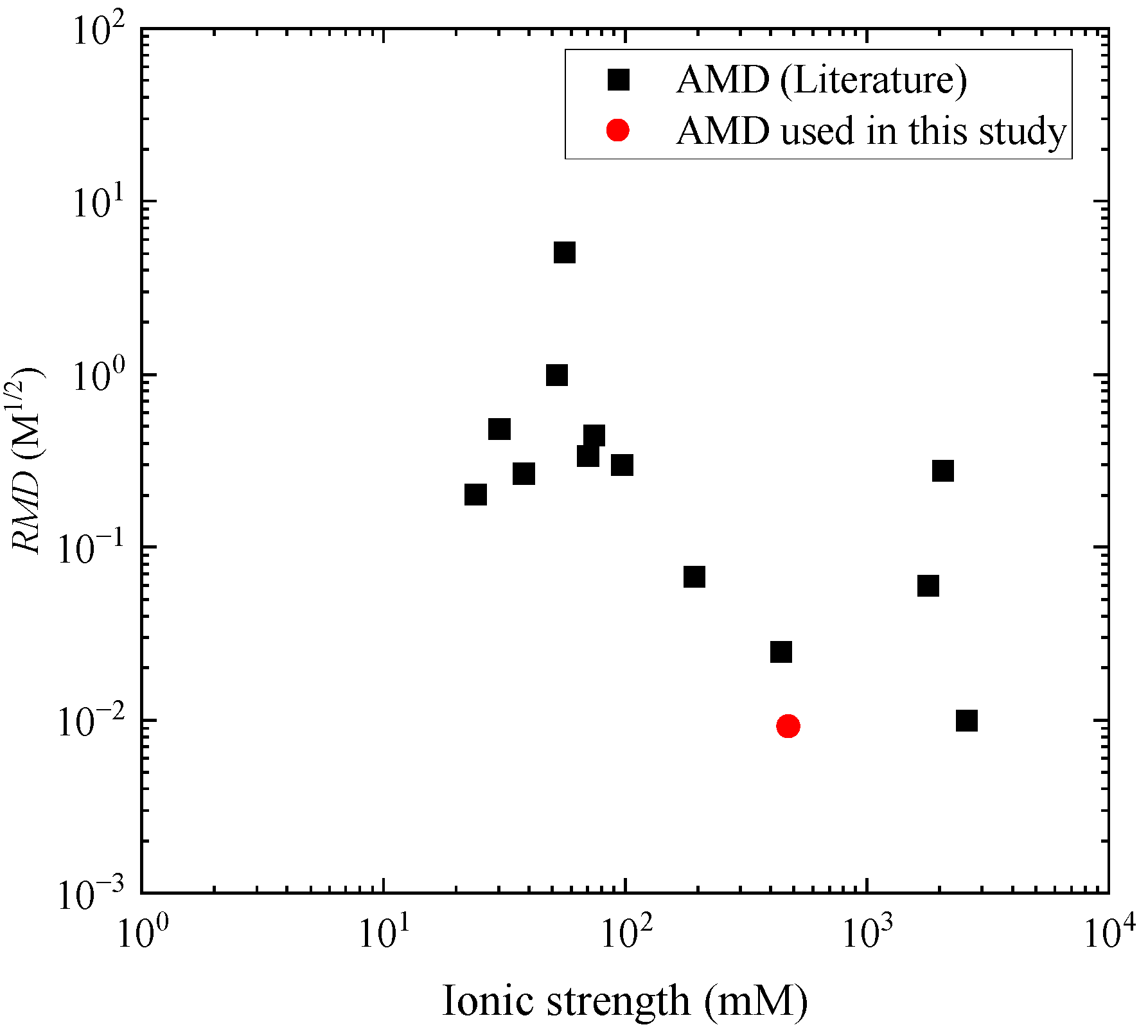

2.3. Acid Mine Drainage

2.4. MFL Test

2.5. Swell Index Test

2.6. Viscosity Test

3. Results

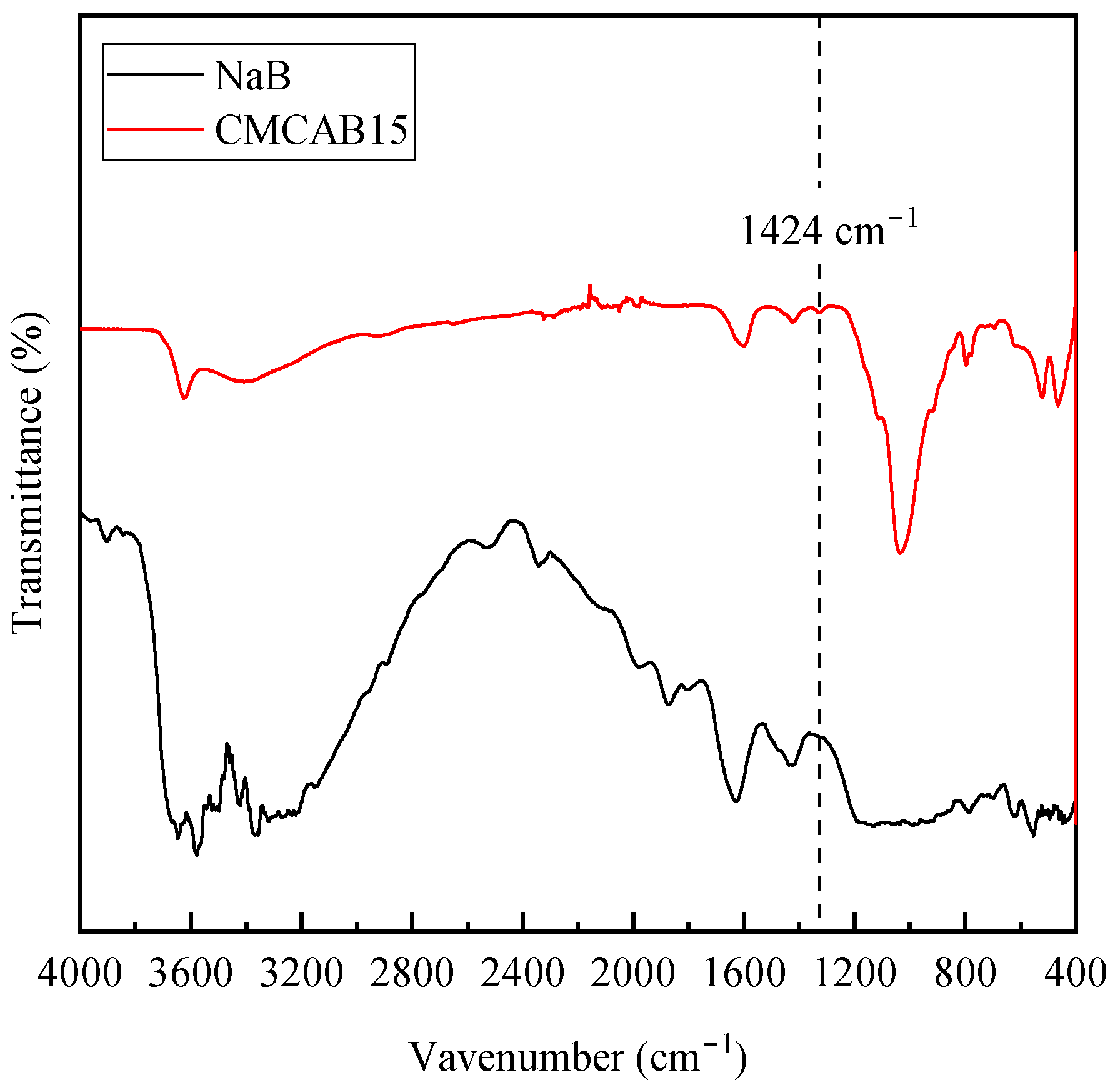

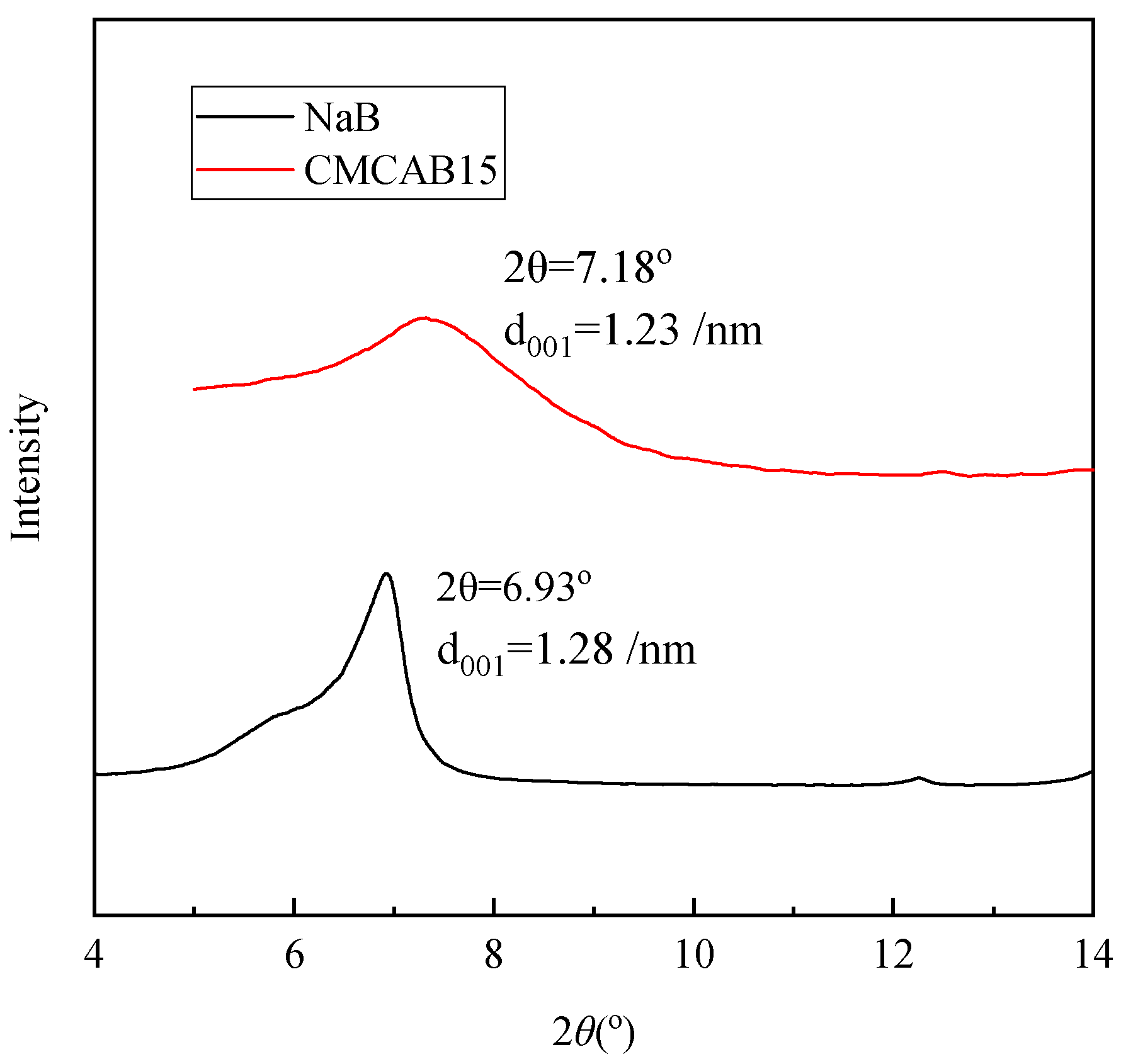

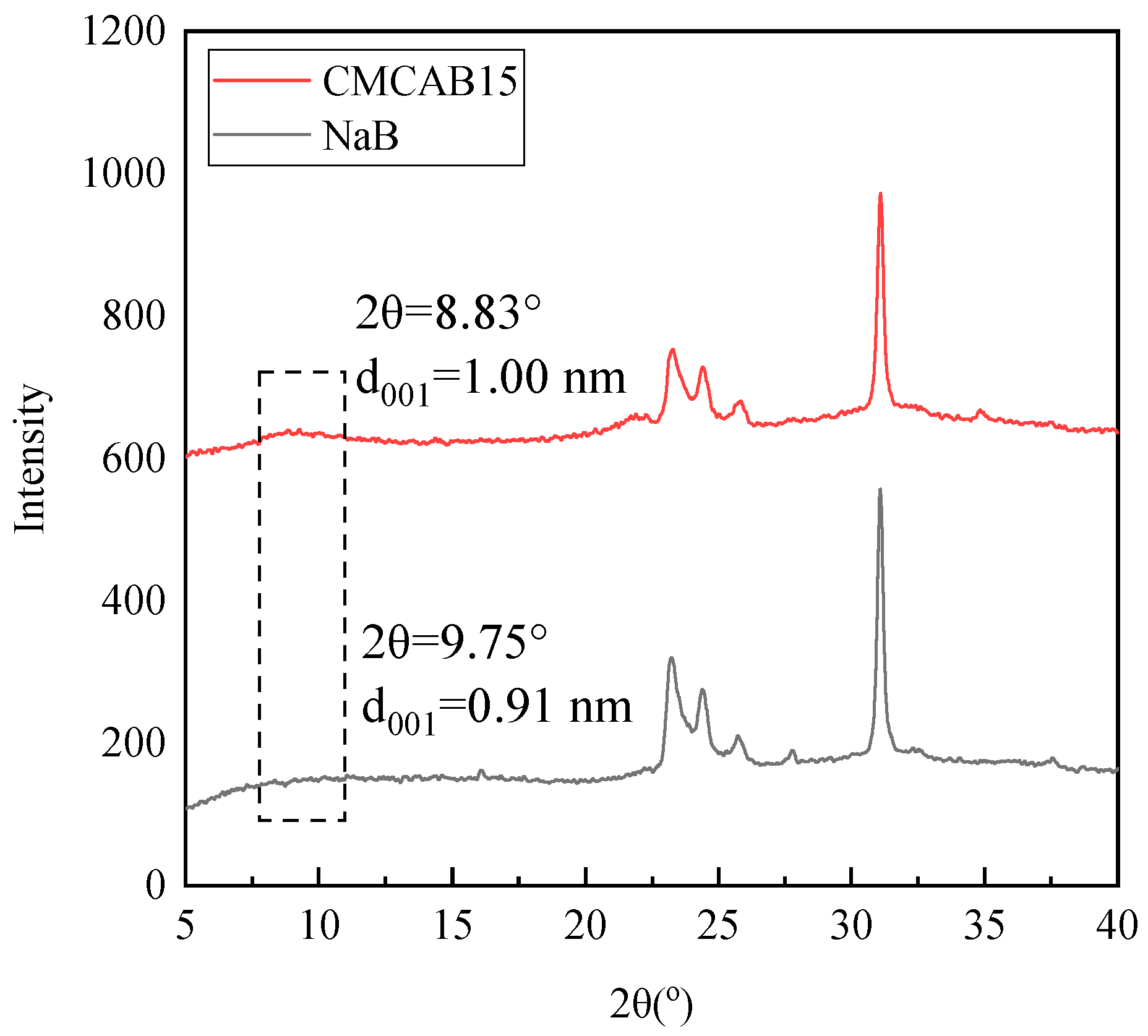

3.1. Characterization of Bentonites

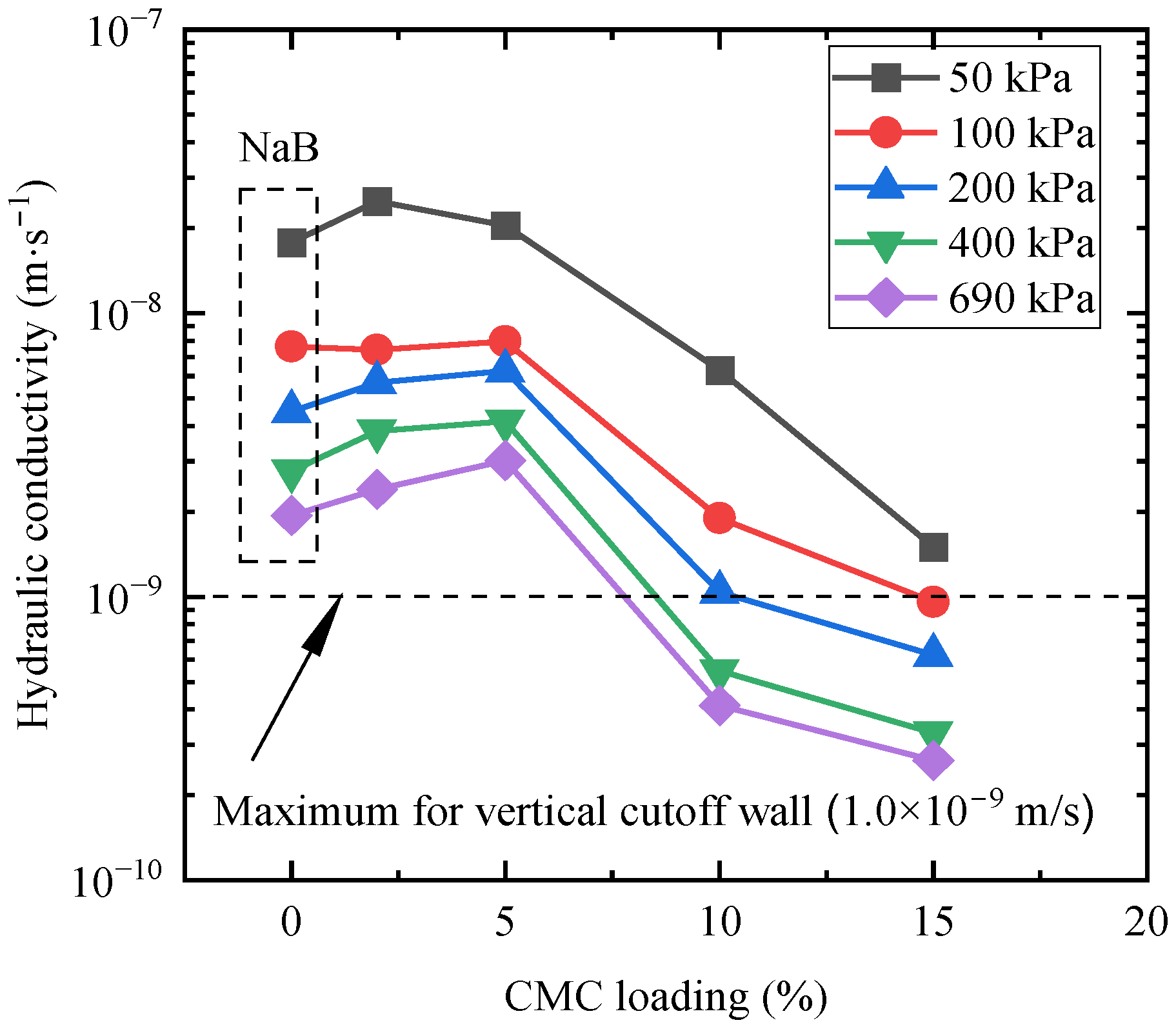

3.2. K Tests

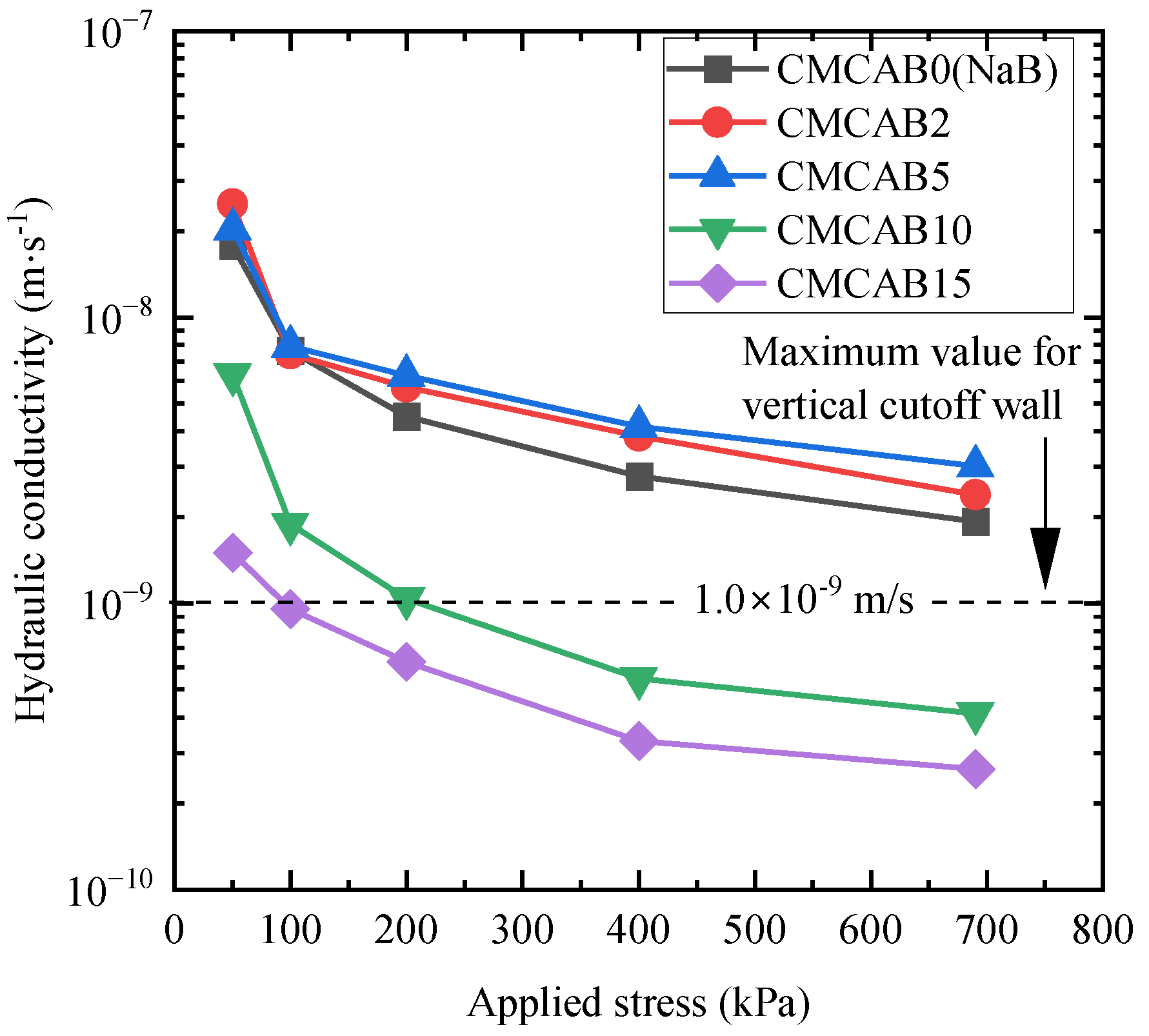

3.2.1. Effect of Na-CMC Mass Loading on k

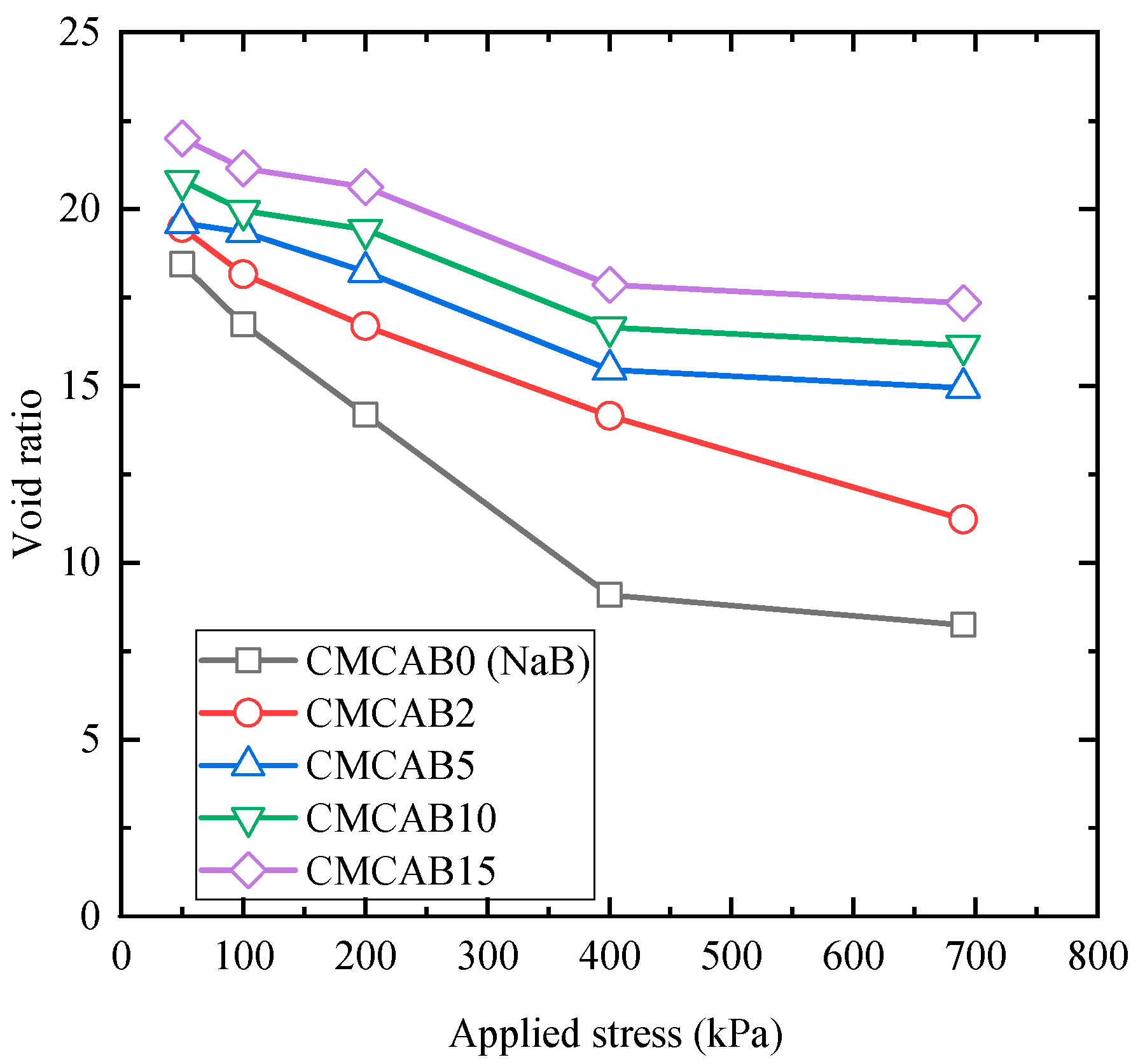

3.2.2. Effect of Applied Stress on the Hydraulic Conductivity

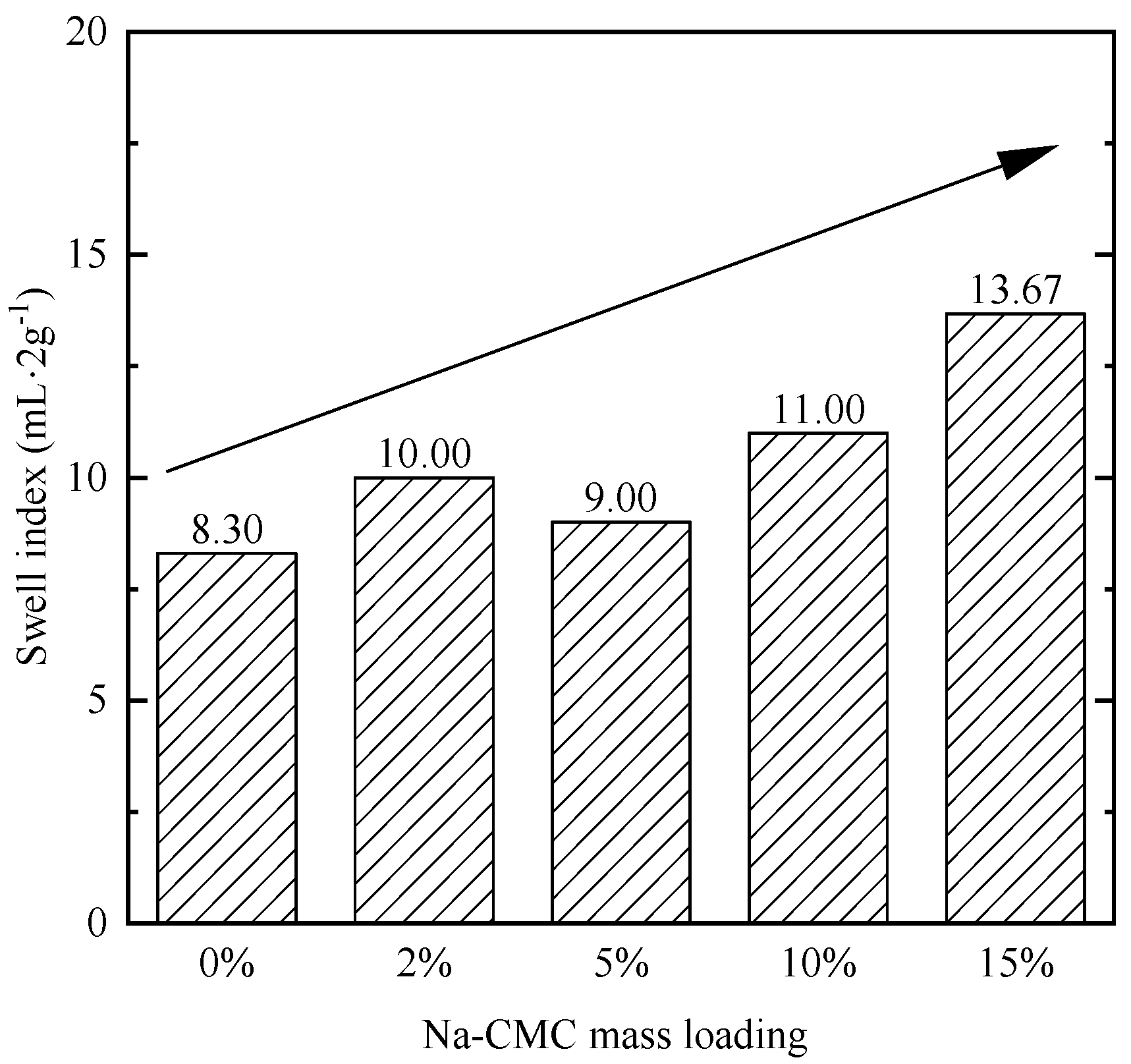

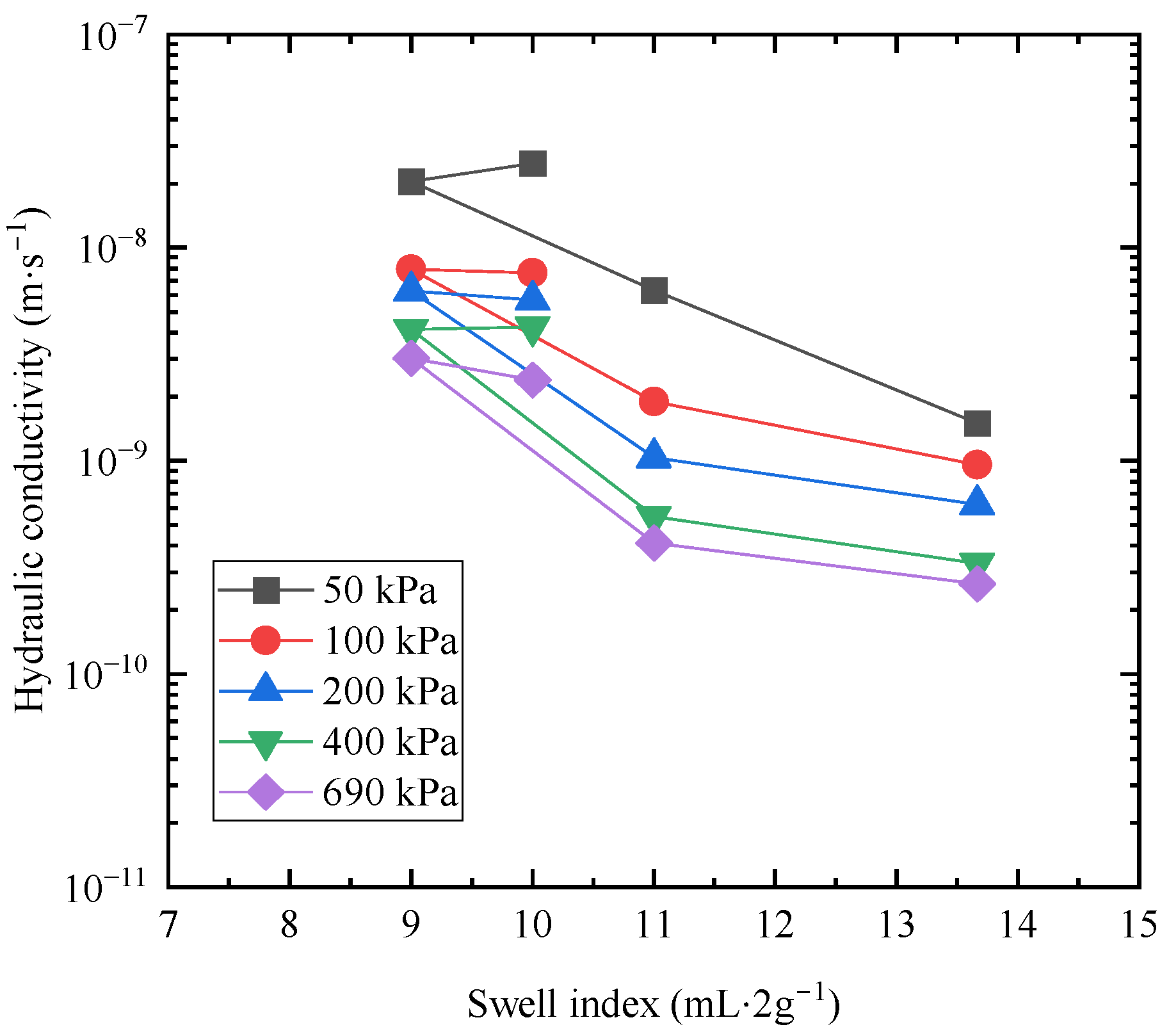

3.3. Swell Indexes of Bentonites

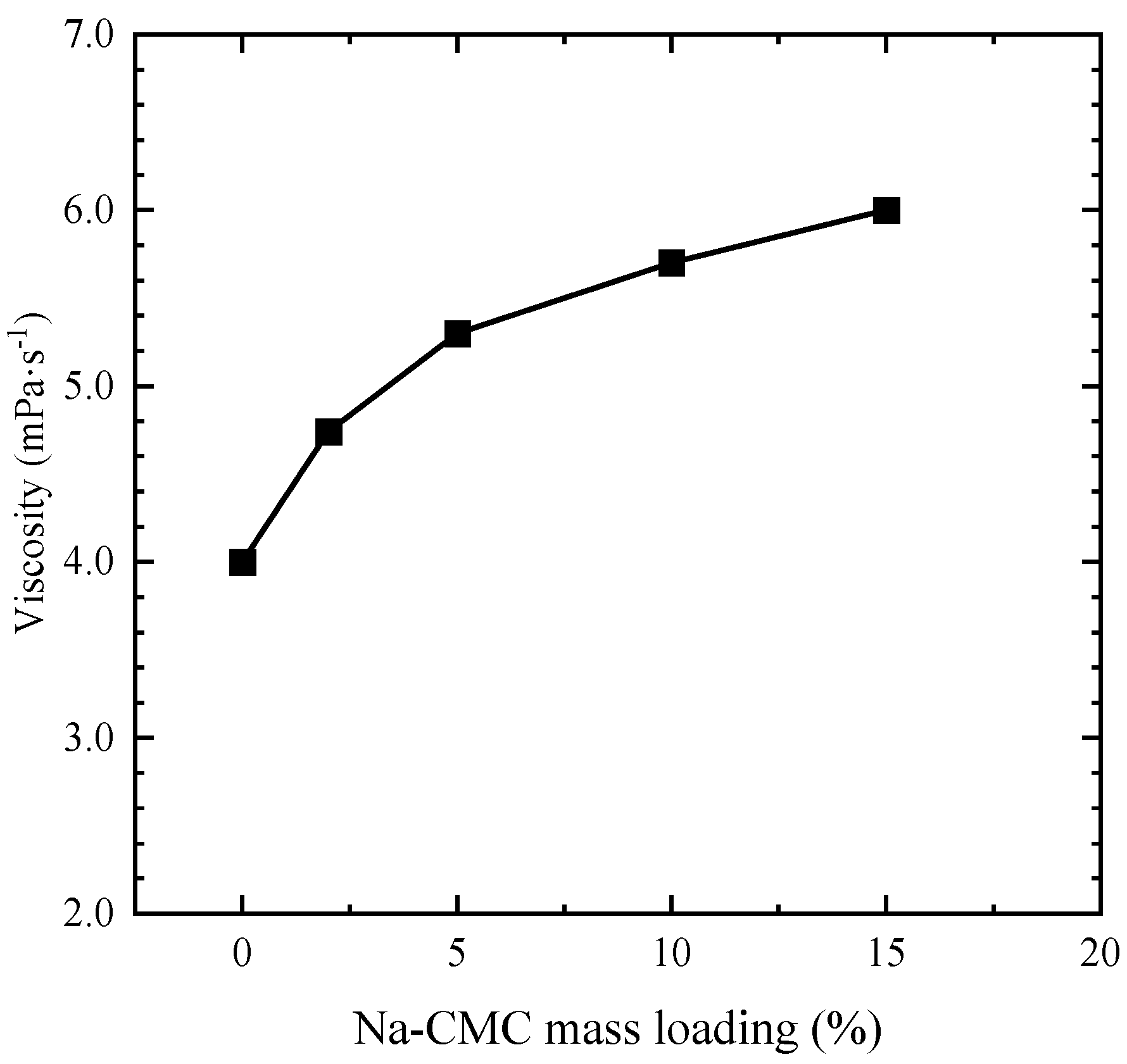

3.4. Viscosity of AMD-Bentonites Slurry

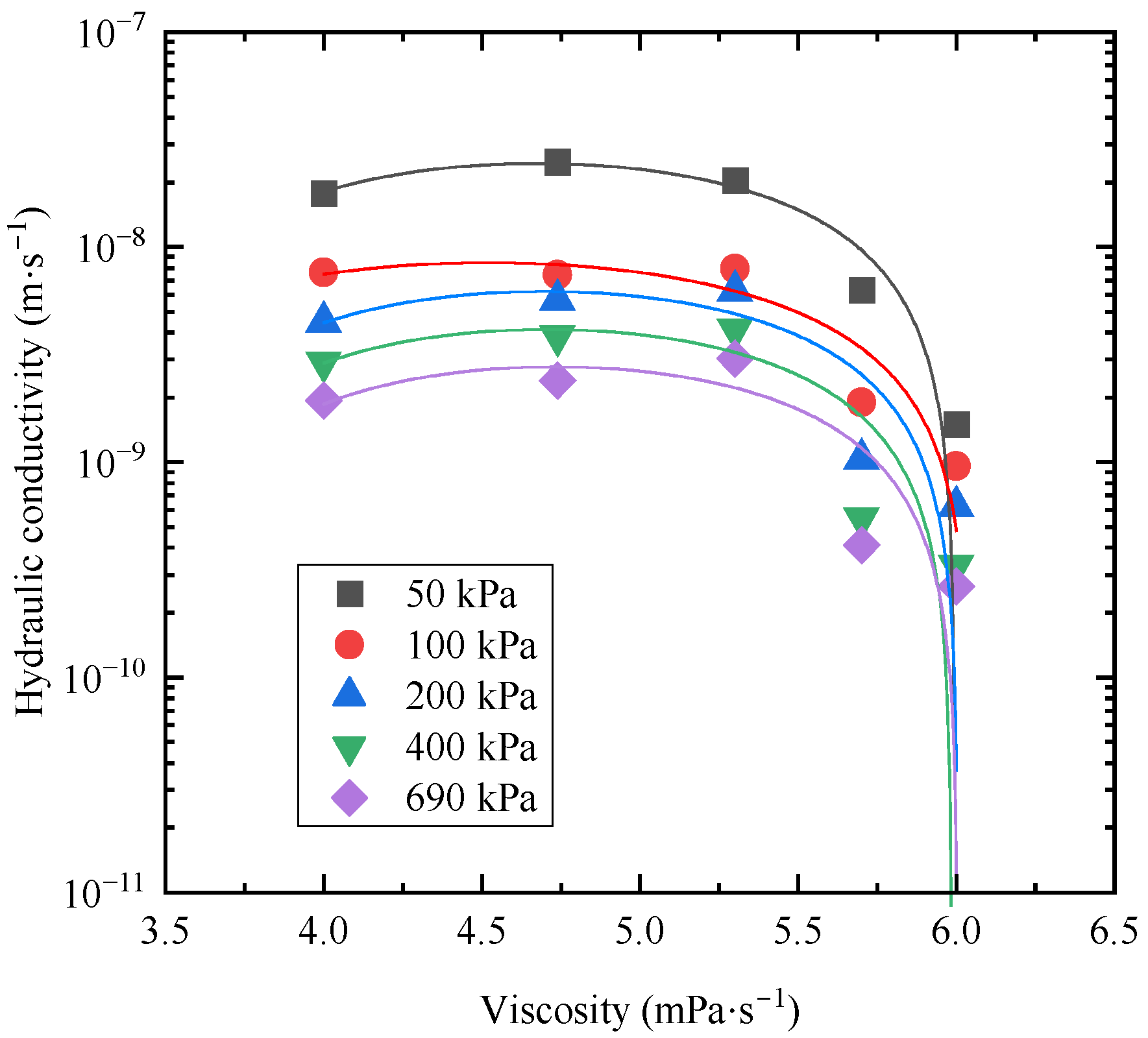

3.5. Prediction of the Hydraulic Conductivity of Amended Bentonites

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mafra, C.; Bouzahzah, H.; Stamenov, L.; Gaydardzhiev, S. An integrated management strategy for acid mine drainage control of sulfidic tailings. Miner. Eng. 2022, 185, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.; Valente, T. Seasonal impact of acid mine drainage on water quality and potential ecological risk in an old sulfide exploitation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 21124–21135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, A.; Tapia, J.C.J.; Lapidus, G.T. Evaluation of acid mine drainage (AMD) from tailings and their valorization by copper recovery. Miner. Eng. 2023, 191, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Reddy, K.R.; Du, Y.J.; Fan, R.D. Short-term hydraulic conductivity and consolidation properties of soil-bentonite backfills exposed to CCR-Impacted groundwater. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Du, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z. Engineering behavior and sedimentation behavior of lead contaminated soil-bentonite vertical cutoff wall backfills. J. Cent. South Univ. 2013, 20, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malusis, M.A.; Barlow, L.C. Comparison of laboratory and field measurements of backfill hydraulic conductivity for a large-scale soil-bentonite cutoff wall. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Fu, X.; Shi, J.; Che, C.; Du, Y. Engineering properties of novel vertical cutoff wall backfills composed of alkali-activated slag, polymer-amended bentonite and sand. Polymers 2023, 15, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Tan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Liu, P. Hydraulic conductivity of air-dried bentonite–sand blocks permeated with synthetic groundwater from radioactive waste repository. Can. Geotech. J. 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, P. Effect of drying cracks on swelling and self-healing of bentonite-sand blocks used as engineered barriers for radioactive waste disposal. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Shamet, R.; Hyun Nam, B.; Pu, H. Predicting the hydraulic conductivity of compacted soil barriers in landfills using machine learning techniques. Waste Manag. 2023, 157, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, F.; He, D.; Zhu, J. Shrinkage property of bentonite-sand mixtures as influenced by sand content and water salinity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.Y.; Katsumi, T.; Benson, C.H.; Edil, T.B. Hydraulic conductivity and swelling of nonprehydrated GCLs permeated with single-species salt solutions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2001, 127, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Chen, B.; Dong, X.; Dou, T. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners to inorganic waste leachate. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 168, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dong, X.; Chen, B.; Dou, T. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners permeated with acid mine drainage. Mine Water Environ. 2019, 38, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, J.; Benson, C.H. Predicting hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners using a neural network algorithm. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2022, Charlotte, NC, USA, 20–23 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, C.H.; Tan, Y.; Youngblood, J.; Bradshaw, S.L. Bentonite-polymer composite geosynthetic clay liners for heap leach liners. In Proceedings of the Heap Leach Mining Solutions 2022, Sparks, NV, USA, 16–18 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, K.; Likos, W.J.; Benson, C.H. Polymer elution and hydraulic conductivity of bentonite-polymer composite geosynthetic clay liners. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, Y.; Chen, J.; Peng, D.; Huang, T.; Meng, C. Hydraulic conductivity and multi-scale pore structure of polymer-enhanced geosynthetic clay liners permeated with bauxite liquors. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, Y.; Copeland, T.; Chen, J.; Peng, D.; Huang, T. Polymer elution and hydraulic conductivity of polymer-bentonite geosynthetic clay liners to bauxite liquors. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 242, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Di Emidio, G.; Flores, R.D.V.; Bezuijen, A. Hydraulic conductivity and swelling pressure of GCLs using polymer treated clays to high concentration CaCl2 solutions. In Geotechnical Engineering for Infrastructure and Development, 1st ed.; Winter, M.G., Smith, D.M., Eldred, P.J.L., Toll, D.G., Eds.; ICE Publishing: London, OH, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 2687–2692. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xia, L.; Yang, Y.; Dina, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhan, L.; Chen, Y.; Bate, B. Polymer-modified bentonites with low hydraulic conductivity and improved chemical compatibility as barriers for Cu2+ containment. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 1629–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, R.; Reddy, K.R.; Yang, Y.; Du, Y. Index properties, hydraulic conductivity and contaminant-compatibility of CMC-treated sodium activated calcium bentonite. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Emidio, G.; Mazzieri, F.; Verastegui-Flores, R.D.; Van Impe, W.; Bezuijen, A. Polymer-treated bentonite clay for chemical-resistant geosynthetic clay liners. Geosynth. Int. 2015, 22, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeren, D.; Senturk, U.; Guden, M. The expansion behavior of slurries containing recycled glass powder carboxymethyl cellulose, lime and aluminum powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.; Scalia, J.; Shackelford, C.D. Mechanisms controlling the hydraulic conductivity of anionic polymer-enhanced GCLs. Geosynth. Int. 2022, 30, 628–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, C.D.; Sevick, G.W.; Eykholt, G.R. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners to tailings impoundment solutions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2010, 28, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazizadeh, S.; Bareither, C.A.; Scalia, J.; Shackelford, C.D. Synthetic mining solutions for laboratory testing of geosynthetic clay liners. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2018, 144, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Shen, S.; Tian, K.; Yang, Y. Effect of polymer amendment on hydraulic conductivity of bentonite in calcium chloride solutions. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04020452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gates, W.P.; Bouazza, A.; Rowe, R.K. Fluid loss as a quick method to evaluate hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners under acidic conditions. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 51, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Daniel, D.E. Modified fluid loss test as an improved measure of hydraulic conductivity for bentonite. Geotech. Test. J. 2008, 31, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; You, X.; Chen, J.; Fu, X.; Du, Y. Hydraulic conductivity of novel geosynthetic clay liner to bauxite liquor from China: Modified fluid loss test evaluation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.; Feng, S.; Zheng, Q.; Peng, C. Hydraulic conductivity and compressibility of polyanionic cellulose-modified sand-calcium bentonite slurry trench cutoff wall materials. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 5503–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Salihoglu, H.; Likos, W.J.; Benson, C.H. Alternative index tests for geosynthetic clay liners containing bentonite-polymer composites. Environ. Geotech.-J. 2022, 11, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Man, R.; Shang, L.; Chen, J. Efficient removal of cadmium from aqueous solution by chitosan grafted pillared bentonite. Colloid Surf. A.-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 696, 134373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Liu, L.; Xue, Q. Comparative assessment of modified bentonites as retardation barrier: Adsorption performance and characterization. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Fu, X.; Reddy, K.R.; Wang, M.; Du, Y. Interlayer and surface characteristics of carboxymethyl cellulose and tetramethylammonium modified bentonite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthana, S.; Arnepalli, D.N. Hydraulic performance of polymer-modified bentonites for development of modern geosynthetic clay liners: A review. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2022, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Pathegama Gamage, R.; Rathnaweera, T.; Kong, L. Review of application of molecular dynamic simulations in geological high-level radioactive waste disposal. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 168, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Singh, G.; Kang, T.S. Colloidal systems of surface active ionic liquids and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose: Physicochemical investigations and preparation of magnetic nano-composites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 18528–18538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Zhuang, H.; Reddy, K.R.; Jiang, N.; Du, Y. Novel composite polymer-amended bentonite for environmental containment: Hydraulic conductivity, chemical compatibility, enhanced rheology and polymer stability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 378, 131200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wireko, C.; Abichou, T.; Tian, K.; Zainab, B.; Zhang, Z. Effect of incineration ash leachates on the hydraulic conductivity of bentonite-polymer composite geosynthetic clay liners. Waste Manag. 2022, 139, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, K.; Benson, C.H.; Likos, W.J. Hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners to low-level radioactive waste leachate. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2016, 142, 040160378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.B.; Shackelford, C.D. Consolidation of a geosynthetic clay liner under isotropic states of stress. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 136, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, R.J.; Rowe, R.K. Geosynthetic clay liner (GCL)-chemical compatibility by hydraulic conductivity testing and factors impacting its performance. Can. Geotech. J. 1997, 34, 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalia, J.; Benson, C.H.; Bohnhoff, G.L.; Edil, T.B.; Shackelford, C.D. Long-term hydraulic conductivity of a bentonite-polymer composite permeated with aggressive inorganic solutions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2014, 140, 04013025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wireko, C.; Abichou, T. Investigating factors influencing polymer elution and the mechanism controlling the chemical compatibility of GCLs containing linear polymers. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 1004–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prongmanee, N.; Chai, J.; Shen, S. Hydraulic properties of polymerized bentonites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 0401824710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumi, T.; Ishimori, H.; Onikata, M.; Fukagawa, R. Long-term barrier performance of modified bentonite materials against sodium and calcium permeant solutions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2008, 26, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shackelford, C.D.; Benson, C.H.; Jo, H.; Edil, T.B. Correlating index properties and hydraulic conductivity of geosynthetic clay liners. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Liquid Limit (%) | Plastic Limit (%) | Swell Index (mL·2 g−1) | Mineral Composition (%) | Cation Exchange Capacity (meq·100 g−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montmorillonite | Quartz | Feldspar | Kaolinite | Potassium Feldspar | ||||

| 314 | 40 | 39 | 70.56 | 18.30 | 5.80 | 2.94 | 2.40 | 91 |

| Properties | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | / | 250,000 |

| Degree of substitution | / | 0.9 |

| Viscosity | mPa·s | 1500–3100 |

| pH | 6.5–8.5 | |

| Melting point | °C | 260 |

| Density | g/cm3 | 1.6 |

| Parameter | Source Compound | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | H2SO4 | 2.5 | − |

| Cd2+ | Cd(NO3)2·4H2O | 5 | mg/L |

| Pb2+ | PbCl2 | 1.2 | mg/L |

| Cu2+ | CuSO4·5H2O | 65 | mg/L |

| Zn2+ | ZnSO4·7H2O | 2400 | mg/L |

| Ni2+ | NiCl2·6H2O | 2 | mg/L |

| Mn2+ | MnCl2·4H2O | 180 | mg/L |

| Fe | FeSO4·7H2O | 450 | mg/L |

| Ca2+ | CaSO4·2H2O | 300 | mg/L |

| Mg2+ | MgSO4·7H2O | 1500 | mg/L |

| Bentonite Filter Cakes | 50 kPa | 100 kPa | 200 kPa | 400 kPa | 690 kPa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k (m/s) | kCMCAB /kNaB | k (m/s) | kCMCAB /kNaB | k (m/s) | kCMCAB /kNaB | k (m/s) | kCMCAB /kNaB | k (m/s) | kCMCAB /kNaB | |

| CMCAB0 (NaB) | 1.78 × 10−8 | 1.00 | 7.63 × 10−9 | 1.00 | 4.51 × 10−9 | 1.00 | 2.78 × 10−9 | 1.00 | 1.93 × 10−9 | 1.00 |

| CMCAB2 | 2.48 × 10−8 | 1.40 | 7.44 × 10−9 | 0.97 | 5.70 × 10−9 | 1.26 | 3.84 × 10−9 | 1.38 | 2.40 × 10−9 | 1.24 |

| CMCAB5 | 2.04 × 10−8 | 1.15 | 7.94 × 10−9 | 1.04 | 6.26 × 10−9 | 1.39 | 4.15 × 10−9 | 1.49 | 3.03 × 10−9 | 1.57 |

| CMCAB10 | 6.30 × 10−9 | 0.35 | 1.89 × 10−9 | 0.25 | 1.04 × 10−9 | 0.23 | 5.47 × 10−10 | 0.20 | 4.13 × 10−10 | 0.21 |

| CMCAB15 | 1.50 × 10−9 | 0.08 | 9.58 × 10−10 | 0.13 | 6.24 × 10−10 | 0.14 | 3.31 × 10−10 | 0.12 | 2.64 × 10−10 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, X.; Wang, B.; Hu, Y. Hydraulic Performance of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Amended Bentonite in Vertical Cutoff Walls for Containing Acid Mine Drainage. Processes 2025, 13, 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123866

Dong X, Wang B, Hu Y. Hydraulic Performance of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Amended Bentonite in Vertical Cutoff Walls for Containing Acid Mine Drainage. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123866

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Xingling, Bao Wang, and Yehao Hu. 2025. "Hydraulic Performance of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Amended Bentonite in Vertical Cutoff Walls for Containing Acid Mine Drainage" Processes 13, no. 12: 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123866

APA StyleDong, X., Wang, B., & Hu, Y. (2025). Hydraulic Performance of Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Amended Bentonite in Vertical Cutoff Walls for Containing Acid Mine Drainage. Processes, 13(12), 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123866