Abstract

Coagulation–flocculation, historically reliant on simple inorganic salts, has evolved into a technically sophisticated process that is central to the removal of turbidity, suspended solids, organic matter, and an expanding array of micropollutants from complex wastewaters. This review synthesizes six decades of research, charting the transition from classical aluminum and iron salts to high-performance polymeric, biosourced, and hybrid coagulants, and examines their comparative efficiency across multiple performance indicators—turbidity removal (>95%), COD/BOD reduction (up to 90%), and heavy metal abatement (>90%). Emphasis is placed on recent innovations, including magnetic composites, bio–mineral hybrids, and functionalized nanostructures, which integrate multiple mechanisms—charge neutralization, sweep flocculation, polymer bridging, and targeted adsorption—within a single formulation. Beyond performance, the review highlights persistent scientific gaps: incomplete understanding of molecular-scale interactions between coagulants and emerging contaminants such as microplastics, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and engineered nanoparticles; limited real-time analysis of flocculation kinetics and floc structural evolution; and the absence of predictive, mechanistically grounded models linking influent chemistry, coagulant properties, and operational parameters. Addressing these knowledge gaps is essential for transitioning from empirical dosing strategies to fully optimized, data-driven control. The integration of advanced coagulation into modular treatment trains, coupled with IoT-enabled sensors, zeta potential monitoring, and AI-based control algorithms, offers the potential to create “Coagulation 4.0” systems—adaptive, efficient, and embedded within circular economy frameworks. In this paradigm, treatment objectives extend beyond regulatory compliance to include resource recovery from coagulation sludge (nutrients, rare metals, construction materials) and substantial reductions in chemical and energy footprints. By uniting advances in material science, process engineering, and real-time control, coagulation–flocculation can retain its central role in water treatment while redefining its contribution to sustainability. In the systems envisioned here, every floc becomes both a vehicle for contaminant removal and a functional carrier in the broader water–energy–resource nexus.

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context: Challenges Linked to Wastewater Pollution

Wastewater management has become one of the critical knots in the fabric of global environmental sustainability. Far from being a simple by-product of domestic, industrial, or agricultural activities, wastewater represents a dynamic interface between human development and ecological integrity. When mismanaged, it acts as a vector of instability—disrupting biogeochemical cycles, threatening public health, and undermining the hydrological resilience of ecosystems and communities [1].

Today, demographic expansion, urban densification, the growth of extractive industries, and the mounting pressure of climate change on hydrological regimes converge to create heightened exposure to multifaceted water pollution [2]. This global convergence reinforces a well-established reality: conventional sanitation infrastructures, often under-dimensioned, are no longer able to keep pace with the growing complexity of wastewater effluents [3].

At the planetary scale, wastewater now contains several thousand anthropogenic compounds, most of which escape conventional treatment. These span entire pollutant classes—reactive nutrients, trace metals, pharmaceutical residues, microplastics, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and multi-resistant biological agents [4]. Their persistence in aquatic matrices profoundly alters ecosystem functions, compromises public health security, and introduces new analytical and regulatory challenges. The limitations of current management approaches are not only technological; they are also rooted in the very architecture of water policies, which remain predominantly linear. The historical separation between the “upstream” phase (production) and the “downstream” phase (treatment) has fostered fragmented, reactive management, ill-suited to address contaminants with long environmental lifespans or diffuse impacts [5].

In an era of mounting water stress, what is needed is a systemic approach that treats wastewater as part of a closed-loop cycle. In this perspective, wastewater valorization is no longer a marginal option but a strategic imperative. The integration of advanced treatment processes, the development of reuse pathways (agricultural, industrial, urban), and the deployment of intelligent sensors for adaptive process control are emerging as essential pillars of 21st-century water engineering [6].

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Wastewater Treatment Technologies

For decades, conventional wastewater treatment technologies—such as primary sedimentation, aerobic biological processes like activated sludge, and chemical coagulation—formed the backbone of municipal and industrial sanitation systems. These approaches remain relevant for reducing overall organic loads and suspended solids [7]. However, they now face structural, technical, and environmental limitations in the face of increasingly complex effluent compositions [8,9,10].

From a technological perspective, their removal efficiency is insufficient for many emerging pollutants. Persistent organic micropollutants, pharmaceutical residues, microplastics, and trace metals often pass through untreated, as documented in numerous studies [11,12,13]. For example, in hospital wastewater treated with conventional methods, significant concentrations of active compounds such as ciprofloxacin, hormones, and disinfectants remain detectable, exerting proven ecotoxicological effects on aquatic communities [14]. Compounding the problem, these systems were designed for relatively stable pollution profiles, whereas today’s effluents fluctuate greatly in both flow rate and composition.

Energy and operational costs are another major constraint. Aerobic biological treatments require substantial oxygen injection, leading to significant energy consumption—typically estimated between 0.3 and 0.6 kWh/m3—which challenges their viability in an energy transition context [15]. Additionally, they generate large volumes of secondary sludge, whose management—dewatering, transport, incineration—remains both an environmental and economic burden, especially in densely populated urban areas.

Resilience is also a limiting factor. Studies on municipal plants have shown that variable hydraulic loads, common during extreme events such as heavy rainfall or industrial discharges, can trigger system failures: drops in treatment efficiency, nutrient release, and clogging of biological reactors [16,17,18]. This operational instability calls into question the adaptability of these technologies to contemporary urban contexts characterized by intermittent flows and diverse pollutant profiles. Furthermore, conventional systems typically operate within a linear “treat-and-discharge” paradigm, with minimal recovery of valuable resources from wastewater—such as nitrogen, phosphorus, or thermal energy. Evaluations from the European AquaFit4Use program revealed that over 60% of dissolved nutrients in municipal and industrial discharges are not recovered, primarily due to the absence of recovery modules or hybrid treatment configurations [19].

In certain industrial sectors—such as pesticide manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, and textiles—the chemical complexity of effluents exceeds the treatment capabilities of traditional systems. For instance, wastewater from a pesticide plant was found to contain chlorinated compounds that conventional biological treatments could not remove, necessitating the addition of advanced processes such as electrocoagulation or advanced oxidation to meet discharge standards [20]. In this light, while conventional technologies remain robust and well-established, they no longer meet contemporary requirements for versatility, sustainability, adaptability, and resource recovery. Their modernization—or integration with advanced treatment processes—has become a strategic priority in the development of smarter, more sustainable, and more efficient wastewater treatment systems.

1.3. The Role of Coagulants in Wastewater Treatment Chains

In modern wastewater treatment systems, coagulation–flocculation stands as a pivotal stage in both primary and tertiary treatment. Historically dominated by metal salts such as aluminum and iron, the process has evolved to meet new demands for performance, environmental safety, regenerability, and versatility in handling increasingly complex effluents. The coagulant is no longer merely a clarification aid; it has become a strategic lever for targeted treatment, cost reduction, and optimization of water circularity [21,22].

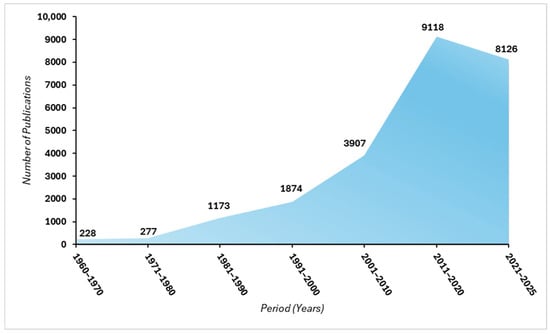

Against a backdrop of technological innovation and diversification of approaches, Figure 1 illustrates the evolution in the number of scientific publications on coagulants for wastewater treatment, compiled from Scopus and Springer databases using the keywords “coagulant” and “water” from 1960 to 2025. The trend over six decades is nearly exponential: only a few dozen articles appeared between 1960 and 1980, followed by moderate growth in the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting a growing but still limited interest. A major turning point occurred in the early 2000s with the introduction of advanced polymeric coagulants, hybrid formulations, and increasingly stringent environmental regulations. This period saw a fourfold increase in publications between 2000–2010 compared to 1990–2000. The decade 2010–2020 reached a historic peak with nearly 9000 articles, driven by concerns over sustainability, micropollutant removal, and sludge valorization. Although the volume from 2020–2025 is slightly lower, it remains high, confirming the field’s position as a priority research area. This trajectory reflects not only the scientific and technological evolution of the field but also the environmental urgency that has accelerated the search for innovative and sustainable coagulation–flocculation solutions.

Figure 1.

Trend in the number of publications on coagulants used in wastewater treatment (1960–2025), in ten-year increments (based on a bibliographic search on Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar).

Recent research highlights that hybrid coagulants—combining organic and inorganic agents—outperform conventional formulations in multi-pollutant removal. Literature reviews indicate that certain hybrid coagulants (inorganic–inorganic or inorganic–biopolymer) achieve turbidity removal rates up to 98.5%, COD reduction up to 73.3%, and heavy metal removal up to 99.2% while also minimizing the need for pH adjustment—an important factor when treating complex industrial effluents [23].

In parallel, natural coagulants, often derived from plant-based materials such as starch, seeds (e.g., Moringa oleifera, Dolichos lablab), or even marine shells, are regaining interest. These agents offer higher biodegradability, lower toxicity, and comparable—or even superior—performance to chemical coagulants in removing suspended solids and phosphorus. Pilot-scale trials in Finland using starch-based coagulants achieved turbidity reductions exceeding 90%, with improved sludge quality and optimal compatibility with nutrient recovery processes [24].

From a more technological standpoint, electrocoagulation (EC) processes are emerging as innovative alternatives to traditional chemical coagulants [25,26]. EC uses metal electrodes as an in situ source of coagulants, eliminating the need for external chemical addition. These systems reduce sludge generation, show high efficiency in removing organic micropollutants, and lower the overall carbon footprint. Reviews indicate that electrocoagulation is particularly effective for heavily loaded industrial effluents, such as those from textile and petroleum industries [25,27].

The shift toward sustainable coagulants also responds to the environmental impact of sludge contaminated with aluminum or metal chlorides. A study in Current Pollution Reports demonstrated that natural coagulants provide comparable purification performance to chemical agents while reducing residual toxicity and facilitating by-product recovery [28]. Furthermore, emerging approaches involve multifunctional coagulants—such as grafted polymers or magnetic coagulants—designed to combine pollutant removal with resource recovery (e.g., phosphorus, nitrogen). These innovations align with the transition toward more circular, autonomous, and intelligent treatment systems, adapted to the pressures of urbanization, water scarcity, and industrial sustainability [29].

In sum, the role of the coagulant has expanded far beyond simple colloidal neutralization. It is now a central component of targeted, environmentally responsible, and adaptable treatment strategies—playing an active role in transforming conventional treatment chains into intelligent processing platforms.

1.4. Objective of the Review

Against the backdrop of tightening regulatory frameworks, mounting environmental pressures, and the increasing complexity of urban and industrial effluents, coagulation–flocculation processes are undergoing a significant technological renewal. The purpose of this review is to critically examine recent advances in the field, highlighting innovative, sustainable, and intelligent approaches that are reshaping the traditional paradigms of wastewater treatment.

Specifically, this review aims to:

- Identify recent progress in the development of multifunctional, hybrid, or composite coagulants capable of broadening the range of pollutants removed while minimizing environmental impact-such as magnetic or bio-functional coagulants;

- Assess emerging technological potentials, including assisted electrocoagulation, high-turbulence processes optimized through Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), and real-time adaptive dosing systems;

- Highlight sustainability criteria, including treatment efficiency, reduced coagulant toxicity, ease of sludge valorization, and compatibility with biological or membrane processes.

- Explore the integration of intelligent systems, notably coupling coagulation with automated technologies, IoT-enabled monitoring, and artificial intelligence to dynamically adjust treatment parameters according to load variability;

- Compare findings from applied studies on representative effluents—such as textile, agro-industrial, and petrochemical wastewater—to provide a rigorous synthesis of the optimal conditions for next-generation coagulation–flocculation technologies;

The overarching ambition of this review is to provide a structured, comparative, and forward-looking framework to guide future research and industrial practice toward treatment solutions that are more efficient, environmentally responsible, and intelligent-adapted to the water challenges of the 21st century.

2. Evolution of Coagulant Technologies for Wastewater Treatment

2.1. Traditional Mineral Coagulants (Before the 1960s)

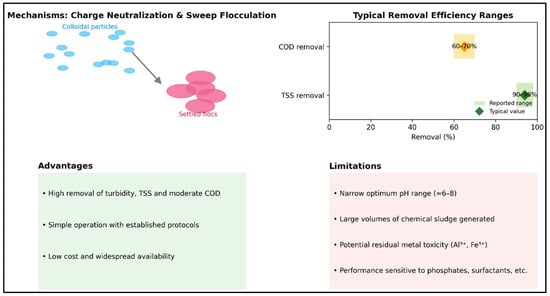

Before the advent of polymeric and composite coagulants, wastewater treatment relied almost exclusively on simple inorganic salts such as aluminum sulfate (alum), ferric chloride (FeCl3), and ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3) [30,31]. These agents primarily act through charge neutralization and sweep flocculation mechanisms, whereby unstable colloidal particles aggregate into larger, settleable flocs [30,31]. While they demonstrated proven effectiveness in reducing turbidity, chemical oxygen demand (COD), and total suspended solids (TSSs), these coagulants exhibited several critical limitations.

First, their performance is highly dependent on pH, with optimal ranges typically narrow (generally between 6 and 8). Second, they generate substantial amounts of chemical sludge, creating significant management and disposal costs. Third, the potential toxicity of residual metals (Al3+, Fe3+) in treated water raised environmental and public health concerns—notably the suspected link between aluminum salts and neurodegenerative diseases [32]. Comparative studies have shown that alum and ferric chloride, either alone or in combination with polymeric flocculants, can achieve TSS removal rates of 90–98% and COD reductions of 60–70%, depending on operational conditions [33]. However, their efficiency can be adversely affected by interactions with other constituents such as phosphates and surfactants, particularly in complex effluents from slaughterhouses or textile industries [34].

Figure 2 provides a visual synthesis of the mechanisms, performance ranges, and advantages/limitations of traditional mineral coagulants. The left panel illustrates the charge neutralization and sweep flocculation principle: small colloidal particles (blue) are aggregated by metallic salts into denser flocs (red) that settle more readily. The horizontal diagram summarizes typical performance ranges: TSS removal often exceeds 80% and can reach 90–95% under optimal conditions, while COD reduction is typically more modest, around 60–70%. These ranges are supported by recent studies. For example, using alum with 1 mg/L of polyelectrolyte, Solmaz et al. reported that COD removal increased from about 50% to 69% when the alum dose was raised to 4.05 mg/L, while turbidity and TSS removal exceeded 80% [35]. With ferric chloride, COD abatement reached approximately 70% at 1.29 mg/L and pH 5, with consistently high removal of turbidity, color, and TSS. Conversely, in studies on semi-aerobic landfill leachate, TSS removal exceeded 95%, but COD reduction was only 43%, highlighting the dependence of performance on effluent characteristics [36].

Figure 2.

Traditional mineral coagulants: mechanisms, ranges of efficacy and summary of advantages/limitations.

The lower panels of the figure (cf. Figure 2) summarize key points: these coagulants are valued for their efficiency, operational simplicity, and low cost but face major drawbacks—narrow optimal pH ranges, large volumes of sludge, risks from residual metal toxicity, and susceptibility to interference from other wastewater constituents. Thus, while traditional mineral coagulants can deliver high clarification performance, their results vary significantly with pH, dosage, and wastewater composition, as consistently shown in the literature.

In addition to sludge-related concerns, studies have found that residual aluminum in treated water can exceed regulatory thresholds when dosing is poorly controlled, necessitating careful monitoring of coagulant dosage and water quality [37]. Although these coagulants remain widely used for their simplicity and low relative cost, their gradual replacement is being driven by stricter environmental standards and the pursuit of more sustainable solutions with lower toxic residue generation.

2.2. Emergence of Synthetic Organic Coagulants and Improved Mineral Formulations (1960–1990)

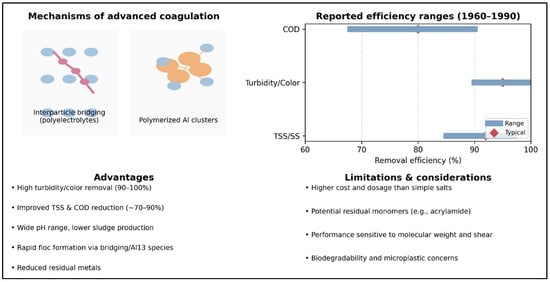

From the 1960s onward, the limitations of traditional mineral coagulants led to the progressive introduction of synthetic organic coagulants and polymerized metallic salts. Two major classes defined this transition: organic polyelectrolytes (notably polyacrylamides, polyamines, and polyDADMACs) and polymerized aluminum chlorides (PACs). Together, they represented a major step forward in performance, stability, and operational safety [38].

Synthetic organic polymers were initially developed as flocculants, but their ability to form interparticle bridges and stabilize flocs allowed them to function effectively as coagulants as well. High-molecular-weight, strongly cationic polyacrylamides proved particularly efficient at removing colloidal matter and organic loads in both industrial and municipal wastewaters [39].

In parallel, polymerized aluminum coagulants such as polyaluminum chloride (PAC) were introduced to overcome the weaknesses of simple salts. PAC contains polymeric species such as Al13, which has a high charge density and enables rapid, efficient colloid neutralization, even at low dosages and across a broad pH range [40]. Optimized dosing and pH adjustments have been shown to achieve 90–100% removal of turbidity and organic dyes from textile effluents [41]. Improvements in PAC formulations—including enrichment in Al13 and the addition of specific anions such as sulfates or silicates—led to variants like polyaluminum silicate chloride (PASiC), offering better coagulation efficiency, reduced sludge generation, and improved stability [42,43,44].

Figure 3 summarizes the major advances observed between 1960 and 1990, when two new families emerged beyond simple metallic salts: high-molecular-weight organic polyelectrolytes and polymerized mineral coagulants such as PAC and its variants. The left-hand vignette illustrates two distinct mechanisms: interparticle bridging by polymer chains, typical of polyacrylamides, polyamines, and polyDADMACs; and the rapid particle aggregation induced by high-charge-density Al13 clusters in PAC and composite coagulants. The horizontal diagram outlines typical ranges reported in the literature: advanced coagulants generally achieve >90% suspended solids removal, up to 95% turbidity and color reduction, and COD decreases between 68% and 90%, depending on effluent type and optimal dosing. For example, in chemically enhanced primary treatment (CEPT) using PAC, suspended solid removal reached 95% and COD 68% at pH 7, while another study reported 97.34% TSS and 75.76% COD removal at pH 7.5 [45]. At 10 mg/L PAC, removals of ~90% TSS and 72% COD were achieved, and coupling PAC with a biological filter increased COD abatement to 96%. Cationic polyacrylamides were capable of removing nearly all turbidity in a simulated water sample (≈99.5%), although their efficiency dropped to ~50% for complex petrochemical effluents [46]. Coagulation assisted by ferrate and PAC has yielded COD reductions of 83–93% with near-complete turbidity removal [47]. Conversely, hybrid polyamide/PAC systems applied with dissolved air flotation achieved ~90% turbidity removal but only 15% COD reduction [30], underscoring how performance varies with effluent composition and coagulant formulation.

Figure 3.

Advanced Coagulants (1960–1990): Mechanisms, Efficiency Ranges, and Practical Considerations.

The lower panel of Figure 3 emphasizes key findings: these advanced coagulants deliver decisive advantages—very high turbidity and color removal, greater reductions in COD and suspended solids, effectiveness over a wider pH range, faster formation of denser flocs, and reduced levels of residual metals. However, limitations remain: higher costs and dosage requirements, potential residual monomers (e.g., acrylamide), sensitivity to molecular weight and shear, and ongoing concerns regarding biodegradability and microplastic generation. Collectively, these developments show that the 1960–1990 period marked a turning point toward more efficient and adaptable coagulation processes, setting the stage for the sustainable innovations that emerged in the following decades.

In industrial applications, these advanced coagulants proved effective in reducing COD, turbidity, and color loads in various effluents, notably in the paper [48] and textile industries. Their advantages also include greater solubility, faster reaction rates, and reduced formation of toxic by-products such as free metal ions [49]. As such, this period represents a clear shift toward more controlled, versatile, and efficient coagulation—laying the foundation for the sustainable and intelligent treatment approaches developed after the 2000s.

2.3. Revival of Natural and Bio-Based Coagulants (1990–2010)

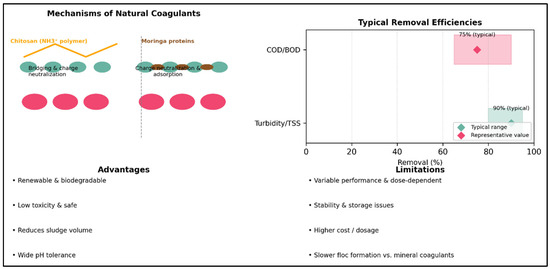

From the 1990s onward, growing environmental concerns, the rising costs of managing chemical sludge, and the potential toxicity of conventional coagulants spurred renewed interest in natural coagulants, particularly those derived from plant and marine sources. This revival aligned with a broader shift toward sustainability and the valorization of local, renewable resources [50,51,52]. Among the most extensively studied natural coagulants are chitosan—derived from chitin in crustacean exoskeletons—and plant-based extracts such as Moringa oleifera, condensed tannins, and modified starches. These biopolymers function through mechanisms of charge neutralization, molecular bridging, and surface adsorption.

Figure 4 illustrates the principle of interparticle aggregation: biopolymers such as chitosan and cationic proteins from Moringa oleifera neutralize colloidal charges and form molecular bridges between particles, leading to their agglomeration. The panel on “Typical Removal Efficiencies” highlights ranges reported in the literature: natural coagulants generally achieve 80–95% removal of turbidity and suspended solids, and 65–90% removal of COD/BOD.

Figure 4.

Natural Bio-Sourced Coagulants (1990–2010)—Mechanisms, Efficiencies, and Summary of Advantages and Limitations.

Chitosan quickly emerged as an effective alternative to synthetic coagulants for treating diverse effluents, including municipal, aquaculture, and agro-industrial wastewaters. It consistently delivers high removal rates for turbidity, phosphorus, and COD while generating smaller volumes of biodegradable sludge [53]. For instance, one study reported that chitosan achieved 84% turbidity reduction at an optimized pH of 6 [54]. Moringa oleifera, rich in cationic proteins, operates primarily through charge neutralization and has demonstrated COD/BOD reductions of up to 90% in certain industrial effluents [54]. Although its performance is sometimes lower than that of chitosan, its low cost and minimal toxicity make it an attractive option in rural regions and developing countries [55]. Beyond these, tannins (plant-derived polyphenols) and modified starches have also shown strong performance in removing phosphorus, suspended solids, and organic matter, while enabling sludge reuse in agricultural applications [56]. Some tannins have even been reported to outperform starches in reducing pollutant loads at low concentrations [53].

Despite their promise, bio-based coagulants are not without limitations. Their efficiency varies with raw material source; they can be unstable in aqueous solutions, and their performance is highly dosage-dependent. Current research is therefore focusing on stabilizing these biopolymers through mild chemical modifications (e.g., grafting, cross-linking) and on combining them with mineral or synthetic coagulants in hybrid formulations [57]. In summary, the period from 1990 to 2010 established a new generation of coagulants firmly embedded within the framework of the circular bioeconomy—agents that combine effectiveness with public health safety and environmental compatibility.

2.4. Recent Innovative and Hybrid Technologies (2010–2025)

Since the early 2010s, coagulation engineering has undergone profound transformation, driven by the emergence of hybrid and composite coagulants designed to meet the increasing complexity of industrial and municipal wastewaters [29,58,59]. Unlike traditional single-component coagulants, these new materials are based on intentional synergies between inorganic agents, natural polymers, and functional nanomaterials. The goal is to simultaneously enhance treatment efficiency, pollutant selectivity, and environmental sustainability [23,60,61].

One of the most widely studied hybrids is the PAC–chitosan composite, which combines the strong charge neutralization of polyaluminum chloride with the biodegradable flocculation properties of chitosan. Studies have demonstrated that such composites not only reduce PAC dosage requirements by up to 30% but also improve performance in turbidity removal (>95%), COD reduction (>85%), and phosphate removal (>70%) [62]. Similarly, a FeCl3-modified starch system—comparable to cationic/amphoteric starches tested by Chen et al.—achieved >98% turbidity reduction and showed strong potential for heavy metal removal at neutral pH [63].

Beyond biopolymers, nanostructured materials are increasingly incorporated into coagulant formulations. Metal oxide nanoparticles (e.g., Fe3O4, ZnO), clay–polymer nanocomposites, and functionalized silica-based structures play active roles in capturing organic and inorganic micropollutants. Zeng et al. reported that a magnetic activated carbon composite (AC@MNPs) combined with PACl achieved 74.02% UV254 reduction and 76.53% TOC removal, compared to only 33.4% and 36.2%, respectively, for PACl alone [64]. Another promising approach involves functionalized bio-based coagulants derived from renewable resources or agro-industrial waste. Activated biochar, produced from sewage sludge or nutshells, has proven to be an excellent support for complexing chitosan or clays, providing both rapid flocculation and extensive adsorption. For example, Mian and Liu demonstrated that a TiO2/Fe3O4/biochar composite derived from sludge achieved a lead adsorption capacity of 216 mg/g, with magnetic recovery in under five minutes [65].

In the context of dye and textile effluents, composites such as PAC–alginate, chitosan–montmorillonite, and nanocellulose–tannin have achieved >95% color removal, >90% COD reduction, and complete sedimentation in under 15 min [66,67]. Parallel advances include integrating these composites into coupled treatment systems—such as coagulation–flocculation followed by ultrafiltration or advanced oxidation (AOP). For instance, Alibeigi-Beni et al. showed that a PAC–iron nanoparticle hybrid system combined with membranes achieved 97% turbidity and 91% COD removal, with significantly reduced membrane fouling [68].

A particularly dynamic area is the development of intelligent multifunctional coagulants, designed with self-adjusting pH responsiveness or endowed with magnetic, thermosensitive, or even bioactive properties. Future perspectives include 3D-printable coagulants, nanoencapsulation of reagents, and the integration of embedded chemical sensors for real-time adaptive dosing. The drive toward next-generation low-carbon materials is equally critical, supported by approaches that combine mechanical performance, durability, and drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Many of these materials are designed to promote circular economy practices by leveraging renewable resources, minimizing waste, and enhancing recycling [69]. Recent advances include bio-inspired construction materials produced at low temperatures using natural binders, which provide cement-comparable strength while reducing carbon footprints by an order of magnitude [70,71]. Similarly, biomass-derived functional carbons are being developed for high-performance applications in energy storage, batteries, and supercapacitors, bridging treatment efficiency with long-term sustainability [72].

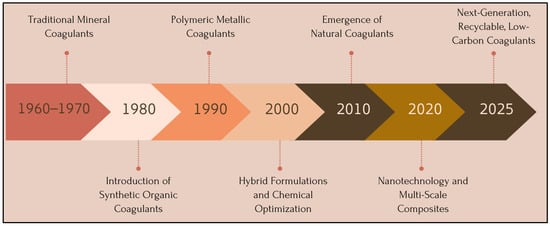

In summary, the evolution of coagulants from the 1960s through 2025 reveals a clear trajectory toward materials that are more reactive, selective, recyclable, and compatible with increasingly stringent discharge standards. This progression is driven by advances in materials science, nanotechnology, and green chemistry. A chronological timeline (cf. Figure 5) can visually illustrate this trajectory—from traditional mineral salts to next-generation multi-scale composites with low-carbon footprints.

Figure 5.

Timeline of Technological Advancements in Coagulants—From Traditional Mineral Salts to Next-Generation Low-Carbon Materials (1960–2025).

3. Coagulation/Flocculation Mechanisms and Performance Criteria

3.1. Fundamentals of Coagulation/Flocculation Mechanisms

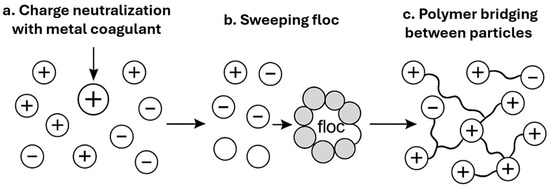

Wastewater treatment through coagulation and flocculation relies on destabilizing colloidal particles, which are naturally present in suspension. These submicron particles typically carry a negative surface charge (with zeta potentials often below −25 mV), preventing spontaneous aggregation due to strong electrostatic repulsion [73]. The addition of a coagulant interrupts this colloidal stability and promotes the aggregation of particles into larger, settleable flocs. This process involves four fundamental physico-chemical mechanisms, often interconnected and highly dependent on operating conditions. These mechanisms are schematically illustrated in Figure 6

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of destabilization mechanisms: (a) charge neutralization by a metal salt, (b) sweep flocculation, (c) polymer bridging between particles.

The first and most critical mechanism is charge neutralization. When a trivalent metal coagulant such as Al3+ or Fe3+ is added, it compresses the electrical double layer surrounding the colloidal particles and partially or completely neutralizes their negative charge. Once the charge is neutralized, attractive Van der Waals forces dominate, allowing aggregation to occur. This mechanism is particularly effective at low coagulant doses and under slightly acidic conditions. Duan and Gregory demonstrated that aluminum-based coagulants achieve optimal performance at pH values between 5.5 and 7 [74].

At higher dosages, a second mechanism—known as sweep flocculation or enmeshment—becomes dominant. Here, amorphous metal hydroxide precipitates (Al(OH)3, Fe(OH)3) form in situ and physically entrap colloidal particles within their settling matrix. This mechanism tends to prevail when coagulants are added in excess under slightly alkaline conditions. According to Ghernaout and Ghernaout, this “sweeping” type of flocculation ensures greater efficiency on highly turbid waters, while offering flexibility in the face of variations in organic load [75].

In parallel, when polymeric coagulants are applied—whether synthetic (e.g., polyacrylamide, PAM) or natural (e.g., chitosan)—interparticle bridging can occur. In this mechanism, long macromolecular chains partially adsorb onto several particles at once, creating physical bridges that bind them together. This produces large, voluminous flocs that are easier to separate. Zhang et al. reported that the addition of an anionic polymer in combination with ferric coagulants increased average floc size by more than 50%, resulting in a 96% turbidity reduction [76].

Finally, specific adsorption and affinity-based interactions can also play an important role. This mechanism is characteristic of some biopolymers (e.g., chitosan, tannins, alginate) or functionalized materials (e.g., biochar, modified clays), which contain active groups capable of selectively binding metal ions, hydrophobic organics, or micropollutants. For instance, Ramlee et al. demonstrated that carboxyl groups in cactus powder interacted with metallic ions in industrial effluents, achieving removal efficiencies above 80% for cadmium and chromium [77].

It is essential to emphasize that the efficiency of these mechanisms depends heavily on the physico-chemical environment, especially pH, which influences both colloid charge and the speciation of metallic coagulants. Ersoy et al. showed that turbidity removal is maximized for aluminum-based coagulants when pH is maintained between 6 and 8 [78]. Other parameters, such as alkalinity, temperature, the intensity of rapid mixing (which ensures proper coagulant dispersion), and the duration of slow mixing (crucial for floc growth), are equally important. Finally, determining the optimal coagulant dose is critical. Underdosing leaves residual colloids in suspension, while overdosing can lead to charge reversal and restabilization of the suspension. For this reason, experimental optimization—most often through laboratory jar tests—remains indispensable for each specific wastewater matrix.

These three fundamental mechanisms—charge neutralization, polymer bridging, and sweep flocculation—serve as the physicochemical basis for most coagulant formulations and are further discussed in application-specific contexts in the following sections.

3.2. Comparative Performance of Different Categories of Coagulants

The performance of coagulants used in wastewater treatment varies widely depending on their chemical nature, structural properties, and dominant mechanisms of action [28,79,80]. It is therefore essential to comparatively evaluate the main classes of coagulants—mineral, synthetic polymers, natural, and hybrid—in order to guide technological choices.

Mineral coagulants such as aluminum sulfate and ferric chloride remain the most widely applied due to their efficiency in removing turbidity and suspended solids. Their action is mainly based on charge neutralization and the formation of insoluble metal hydroxides, which sweep colloidal particles during sedimentation. For example, ferric sulfate has been shown to remove up to 98% of turbidity and 97% of color in textile wastewater [81], while composite aluminum–zinc–iron coagulants (PAZF) achieved 99.4% turbidity removal and 77% COD reduction [82]. However, these coagulants produce significant volumes of chemical sludge, and their efficiency is highly dependent on pH, with narrow optimal ranges near neutrality [83,84,85].

Synthetic organic polymers, such as polyacrylamide and its cationic or anionic copolymers, offer greater application flexibility. Their dominant mechanism is interparticle bridging, which produces large, dense flocs. Several studies have shown that PAM-based polymers can reduce turbidity by more than 90% at very low dosages (<10 mg/L) while maintaining efficiency over a broad pH range [86,87,88]. Nevertheless, concerns remain regarding potential toxicity from residual acrylamide monomers, poor biodegradability, and higher operational costs compared to mineral salts.

Natural coagulants, derived from plant or animal sources such as chitosan, Moringa proteins, or modified biochars, have emerged as more sustainable alternatives. Their advantages include biodegradability, renewability, and non-toxicity. For instance, chitosan has been shown to remove up to 90% of turbidity and 80% of bacterial loads in wastewater [89,90]. However, their performance can be limited in heavily loaded effluents or those containing dissolved pollutants. Standardization and long-term stability also remain challenges for large-scale deployment [91,92,93].

Hybrid and composite coagulants combine inorganic agents (e.g., PAC, FeCl3) with natural or synthetic polymers, leveraging synergies between charge neutralization and polymer bridging. These systems often demonstrate superior performance compared to their individual components. For example, PAFC–CPAM hybrids have achieved 98.5% turbidity reduction, 99.2% heavy metal removal, and 73.3% COD reduction [87,94,95,96]. Some advanced materials—such as PAZF or nanostructured composites—also enable magnetic recovery or selective adsorption, making them multifunctional. However, questions remain regarding their cost-effectiveness and scalability for full industrial implementation.

A comparative summary (cf. Table 1) synthesizes these findings across key criteria, including coagulant type, typical efficiency (%), optimal dosage, effective pH range, advantages, limitations, and application domains. Such a framework is critical to visualizing trade-offs between cost, performance, and sustainability, and to inform rational technological choices in wastewater treatment.

Table 1.

Comparison of coagulant families by performance.

3.3. Criteria for Selecting a Coagulant (Efficiency, Cost, Sustainability, Toxicity, Etc.)

The optimal choice of a coagulant for wastewater treatment requires more than just assessing its removal efficiency. While technical performance, such as turbidity or pollutant removal, remains essential, decision-makers must now balance this with economic feasibility, environmental sustainability, operational constraints, and regulatory compliance. Recent research emphasizes that efficient coagulants must also minimize sludge production, reduce environmental toxicity, and be compatible with existing treatment infrastructure [52]. Furthermore, durability of performance and resilience to variations in wastewater composition are crucial for long-term sustainability [115]. Decision frameworks like the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) have been used to weigh trade-offs between cost, sludge production, sensitivity to pH, and health impacts of coagulants [116]. Additionally, natural and hybrid coagulants are gaining attention as eco-friendly and safer alternatives to conventional chemical options, aligning with green chemistry principles and global sustainability goals [117].

The first determinant is treatment efficiency against the specific pollutants present. For highly turbid waters dominated by mineral particulates, conventional metallic salts such as aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3) or ferric chloride remain highly effective. A year-long monitoring campaign showed significant reductions in turbidity and associated physico-chemical parameters after alum treatment [101]. However, when treating waters rich in color or dissolved organic matter (DOC, COD), cationic polymers or mixed formulations (e.g., PAC combined with a polymer) generally outperform simple mineral coagulants. Their superior interaction with negatively charged humic substances allows for greater organic matter removal [118,119].

Cost considerations are equally decisive. Traditional coagulants such as alum and ferric chloride remain inexpensive (≈0.02–0.05 €/m3 treated) and are globally available, making them attractive for large-scale industrial plants [115]. In contrast, synthetic polymers, purified bio-based coagulants, or advanced hybrid formulations (e.g., magnetic or grafted coagulants) can be five to ten times more expensive per unit dose. Nonetheless, their higher efficiency often allows for reduced dosing requirements, partially offsetting the upfront costs [117].

From a sustainability perspective, bio-based coagulants (e.g., Moringa seeds, chitosan, starch derivatives) offer significant advantages: biodegradability, lower greenhouse gas emissions during production, reduced sludge volumes, and potential reuse of sludge in agriculture [24,120]. However, their large-scale deployment is constrained by challenges such as variability in raw material quality, limited shelf-life, and difficulties in standardization and mass production.

Toxicity concerns are central, particularly in drinking water applications. Aluminum salts have been scrutinized for their potential neurotoxic effects, though evidence remains debated. Synthetic cationic polymers may contain residual monomers such as acrylamide, a compound with recognized carcinogenic potential, necessitating strict monitoring. By contrast, natural coagulants are generally regarded as non-toxic—some being derived from edible plants—making them intrinsically safer [121].

Finally, regulatory frameworks strongly influence coagulant selection. For example, the maximum permissible concentration of residual aluminum in drinking water (typically 0.2 mg/L, as recommended by WHO) has prompted the adoption of PAC or natural alternatives in certain contexts. At the same time, crude natural coagulants may themselves carry risks, such as trace heavy metals or microbial contamination, requiring purification and quality control prior to use [118,119].

Although numerous studies report impressive pollutant removal efficiencies for both conventional and emerging coagulants, these data are often obtained under non-comparable experimental conditions. Variations in influent type, pH, initial turbidity, mixing regime, and coagulant dosage make direct comparisons difficult and may lead to overestimating performance differences. To address this issue, a comparative summary of representative studies was compiled (cf. Table 2) to contextualize reported removal efficiencies under normalized operational parameters. The analysis reveals that, while traditional mineral coagulants (e.g., alum, FeCl3) maintain consistent turbidity reductions above 90%, their performance rapidly declines at neutral or high pH values or in the presence of organic colloids. In contrast, hybrid and biosourced coagulants achieve comparable or superior removal rates at lower dosages, though their performance is strongly matrix-dependent and varies with extraction method and molecular weight. These discrepancies highlight the urgent need for standardized benchmarking protocols and meta-analytical frameworks that normalize results per unit dosage or per charge equivalent, ensuring fair evaluation across coagulant classes and environmental contexts.

Table 2.

Comparative performance of selected coagulant types under normalized conditions.

In summary, the choice of a coagulant cannot be universalized. It requires a holistic evaluation that weighs removal efficiency, economic viability, environmental sustainability, toxicity risks, and compliance with evolving regulations. Such a systemic approach is critical to enabling the transition toward smarter, more sustainable treatment strategies—an agenda explored in the following sections.

4. Scientific Gaps, Technological Limits and Current Challenges

4.1. Scientific Gaps in the Understanding of Coagulation/Flocculation Mechanisms

Despite the widespread application of coagulation–flocculation in wastewater treatment, significant blind spots remain in our understanding of the underlying physico-chemical mechanisms. A critical examination of recent literature reveals several major gaps, spanning both fundamental science and practical implementation.

Recent studies have identified a significant knowledge gap in the treatment of emerging pollutants—most notably microplastics, metallic nanoparticles, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)—using coagulation processes. Traditional coagulants, while effective for conventional contaminants, often fail to adequately remove these newer classes of pollutants due to the absence of robust predictive models that account for critical physicochemical parameters such as particle morphology, size distribution, and surface properties. As highlighted by Khan et al., the lack of such models hinders the development and optimization of coagulant formulations specifically adapted to the diverse and complex characteristics of these emerging contaminants [133].

For instance, the coagulation–flocculation–sedimentation (CFS) process has been shown to be largely ineffective in removing micro- and nanoplastics, with removal efficiencies often below 2%, particularly for smaller particle sizes [134]. Nevertheless, the presence of biofilms on plastic surfaces has been found to enhance aggregation and sedimentation, suggesting that biological interactions can influence removal outcomes.

In response to these challenges, several studies have explored the use of advanced and alternative coagulants. Poly-aluminum chloride (PACl), for example, has demonstrated improved performance in the simultaneous removal of dissolved organic matter, microplastics, and silver nanoparticles, especially when used at optimized dosages [135]. Additionally, electrocoagulation has emerged as a highly effective method, achieving over 95% removal efficiency of nanoplastics under controlled conditions, with the added benefit of enabling physical separation of contaminants via a foam-like floc layer [136].

In complex industrial effluents, multiple pollutants (organic, mineral, particulate) coexist and may interact during coagulation, but these interactions are little studied. For example, recent research is examining the simultaneous removal of composite pollutants—such as microplastics in the presence of organic pollutants (dyes, pharmaceuticals)—to understand how the presence of one contaminant can influence the capture of the other in flocs [137]. Khan et al. recommend further study of chemical interactions between microplastics and flocs, as the forces involved (surface bonds, floc density, buoyancy vs. Brownian forces) strongly determine the sedimentation efficiency of these unconventional particles [137].

Regarding PFAS, removal efficiency has been shown to depend strongly on molecular structure. Longer-chain compounds are more effectively removed via coagulation, particularly when using specialized agents such as Perfluor Ad® or composite coagulants containing activated carbon or cationic polymers. However, shorter-chain PFAS remain recalcitrant under standard treatment conditions [138]. In parallel, there is growing interest in natural and bio-based coagulants such as chitosan and sodium alginate, which have shown potential as sustainable alternatives when combined with conventional agents, particularly in enhancing floc formation and reducing chemical dosage requirements [139].

A second major area of uncertainty in the field of coagulation-based water treatment pertains to the use of natural coagulants. While their potential for sustainable and low-cost water treatment has been widely recognized, the underlying molecular mechanisms that drive their coagulating activity remain poorly characterized. Plant-derived polysaccharides, such as those extracted from Moringa oleifera seeds or Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes, have demonstrated significant removal efficiencies for turbidity, chemical oxygen demand (COD), and even some heavy metals. However, the chemical basis for these effects—particularly the role of active functional groups like carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amino moieties—has not been systematically investigated in most studies.

As noted by Ref. [81] the majority of publications focus on performance metrics (e.g., percentage removal of turbidity or COD) without exploring the molecular-level interactions between coagulant molecules and target pollutants. This lack of mechanistic insight significantly limits the ability to predict performance across different water matrices or to rationally optimize coagulant formulations [29]. These authors highlight the need for further investigations to isolate and understand the main active agents in natural extracts and their modes of action, technological limitations and application constraints [29]. Similarly, for recently developed biological or magnetic coagulants, the mechanisms of action are not fully elucidated, which limits optimization of their efficacy. Moreover, advanced analytical techniques capable of elucidating structure-function relationships—such as Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), and even X-ray diffraction (XRD)—are underutilized in the characterization of natural coagulants. When employed, FTIR often identifies broad functional group regions, but rarely is this data correlated with coagulation performance or pollutant-binding capacity. NMR, which could provide precise structural insights, is almost entirely absent from the literature on natural coagulants.

Furthermore, variability in extraction methods, plant maturity, storage conditions, and even geographic origin can lead to significant heterogeneity in coagulant composition—yet these factors are rarely standardized or reported in detail. As a result, reproducibility and scalability of natural coagulants remain major barriers to their widespread implementation in municipal or industrial water treatment systems.

A third limitation involves the structure and dynamics of flocs. Zaki et al. emphasize the scarcity of studies combining electron microscopy, zeta potential measurements, and numerical modeling to capture floc architecture in terms of porosity, density, and fractal dimension [140]. This knowledge gap is particularly problematic for integrated processes, such as coagulation coupled with membrane filtration, where floc morphology directly affects fouling and separation efficiency.

A fourth challenge lies in the kinetics of floc formation and breakage. As Mohamed Noor and Ngadi point out, few studies propose universal kinetic models describing floc growth, sedimentation velocity, and pollutant concentration profiles over time [141]. Most experimental work remains focused on end-point measurements, neglecting the dynamic evolution of the process.

In the absence of robust predictive models, determining the optimum dose of coagulant/flocculant is still largely based on empirical trials (JAR tests). Indeed, the chemistry of coagulation is complex and depends on numerous parameters (pH, turbidity, conductivity, nature of pollutants, etc.), making it difficult to predict the dose and effectiveness of treatment theoretically [142]. For example, Fang et al. note that the complexity of physico-chemical interactions in a coagulation basin makes it difficult to accurately control the dose using conventional methods, motivating the development of intelligent algorithms to overcome this shortcoming.

Finally, there is a lack of studies that bridge experimental and multi-scale modeling approaches. Al-Jadabi et al. highlight the importance of integrating advanced physico-chemical analysis, CFD modulizations, and real-time monitoring tools (e.g., turbidity, zeta potential sensors) to develop adaptive dosing strategies for heterogeneous effluents [143].

Taken together, these gaps point toward four priority research directions:

- Advanced molecular characterization of natural and hybrid coagulants;

- Multi-scale analysis of floc structures using microscopy, spectroscopy, and modeling;

- Development of robust kinetic models, experimentally validated across different effluent types;

- Integration of experiments, online sensing, and simulation to enable real-time process optimization.

4.2. Technological Limitations and Application Constraints

While the scientific gaps outlined earlier underscore the need to strengthen fundamental knowledge of coagulation–flocculation mechanisms, it is equally crucial to examine the technological and operational barriers that currently limit the efficiency and widespread adoption of these processes in both municipal and industrial contexts. These challenges stem not only from the intrinsic performance of coagulants but also from their practical integration into complex treatment chains. Addressing these obstacles is indispensable to ensuring both the effectiveness and long-term sustainability of real-scale systems.

A first major issue concerns the management of by-products, particularly the sludge generated during coagulation–flocculation. Although these processes are well established for reducing turbidity, organic matter, and heavy metals, the large sludge volumes produced remain a serious environmental and economic burden. For instance, Turna and Yıldız reported that, in the treatment of vegetable oil industry effluents, optimal doses of aluminum salts (up to 800 mg/L) achieved COD removals above 90% yet simultaneously produced substantial amounts of non-recoverable sludge, generating significant logistical and secondary treatment costs [144]. Similarly, Teh et al. identified excessive sludge generation as one of the main limitations of coagulation, highlighting the lack of scalable, sustainable valorization strategies [145]. The problem becomes more complex when the sludge contains residual metals or refractory organics, which compromise its agricultural or energy recovery potential.

A second key limitation lies in the adaptability of coagulation to complex effluents. Numerous studies show that textile, hospital, or agro-industrial wastewaters contain heterogeneous pollutant matrices for which coagulation alone is insufficient. Silva et al. demonstrated that, while pre-coagulation significantly improved turbidity and suspended solids removal in textile effluents, hydrosoluble dyes and persistent organics required additional downstream processes in a combined coagulation/flocculation–direct contact membrane distillation (CF-DCMD) system [146]. Marques et al. similarly reported that coupling coagulation with hydrodynamic cavitation and ozonation enabled COD removals above 90% while reducing sludge production compared to coagulation alone [147]. However, as Tzoupous & Zouboulis noted, such hybrid approaches involve higher capital costs, greater technical expertise, and increased energy demands—factors that restrict their deployment in resource-limited settings, especially in the Global South [148].

Economic constraints represent a transversal challenge. According to Mohamed Noor and Ngadi, coagulants account for 20–35% of total operating costs in wastewater treatment plants, a proportion particularly burdensome in lower-income countries where most coagulants are imported [141]. This financial pressure often leads operators to underdose coagulants or to use lower-quality products, ultimately compromising treatment efficiency. Although local production of bio-based coagulants is sometimes proposed as a cost-effective alternative, their extraction and purification remain energy- and resource-intensive. Owodunni et al., for instance, showed that isolating active compounds from Moringa oleifera or Opuntia ficus-indica requires significant energy and processing inputs, reducing competitiveness compared to conventional mineral coagulants [149]. Moreover, some natural formulations exhibit poor shelf stability, requiring additives or stabilization processes to extend their usability.

Beyond cost and technical factors, environmental and health concerns further complicate adoption. Matesun et al., demonstrated that certain synthetic polymers, while effective at low doses, can release non-biodegradable fragments prone to accumulation and chronic toxicity in aquatic environments [12]. Even natural coagulants are not exempt from scrutiny: Mohamed Noor and Ngadi reported contradictory results regarding phytotoxicity and cytotoxicity, emphasizing the need for long-term toxicological assessments [141]. Such uncertainties not only hinder regulatory approval but also slow the market acceptance of bio-sourced alternatives.

On the other hand, operational challenges remain critical, particularly regarding process control. Parameters such as pH and optimal coagulant dose strongly influence removal efficiency and floc morphology. Conventional inorganic coagulants are often sensitive to pH and dosage. The effectiveness of the process can drop outside an optimal pH range, requiring the pH of the effluent to be adjusted (by adding acid or base) before coagulation. For example, the Fenton process (coagulation/oxidation with Fe2+/H2O2) only works at a pH of ~3, which is a major limitation for its large-scale application [22]. Similarly, overdosing with coagulant can generate a positive residual charge and restabilize particles or lead to chemical waste, while underdosing leaves high residual turbidity. Continuous dose control remains difficult in practice, and plants often operate at a fixed or overcompensated dose to ensure safety, at the expense of economic optimization.

In cosmetic wastewater treatment, Zhang et al. showed that polyaluminum chloride (PAC) performance depended heavily on maintaining a narrow pH window (6–7.5), which is difficult to achieve under real conditions without advanced automation. Oktaviani & Adachi further highlighted that even minor deviations in mixing intensity or flocculation time can destabilize microflocs, impair sedimentation, and compromise overall process efficiency [150]. These findings underline the need for precise control systems, which remain a challenge in small-scale or batch-operated treatment facilities.

Finally, it should be noted that the coagulation–flocculation process itself remains relatively energy-efficient. In fact, energy requirements are mainly limited to the mechanical agitation required for the rapid mixing (coagulation) and slow mixing (flocculation) phases, without the need for heat sources or complex equipment. However, if we broaden our thinking to include the entire treatment chain, indirect energy consumption items appear: pumping the water to be treated, activating the mixing systems, and downstream operations related to sludge management, such as dewatering, transport, or final disposal, can represent a significant portion of the system’s overall energy footprint.

Furthermore, the role of coagulation–flocculation is particularly important in hybrid configurations where it is integrated upstream of so-called “advanced” treatments, such as ozonation, UV irradiation, or membrane filtration. In these contexts, its main objective is not only to clarify the water but above all to reduce the organic or colloidal load, so as to limit energy consumption in subsequent, more resource-intensive stages. Lucas et al. illustrate this point by showing that pre-coagulation of heavily loaded industrial effluents significantly reduces the energy required for residual carbon oxidation during advanced treatment by oxidation processes [22]. Thus, far from being a simple pretreatment step, coagulation–flocculation plays a strategic role in the overall energy optimization of modern treatment processes. In this regard, Vadasarukkai and Gagnon demonstrated that the rapid mixing intensity applied in treatment plants is often higher than necessary and that a strategic reduction in this energy would make it possible to maintain equivalent water quality while reducing energy requirements [151].

Recent literature reviews agree that only an integrated approach (combining chemical, biological, and/or advanced methods) and multi-criteria optimization (performance, cost, environment) will enable these challenges to be met [12,22].

Taken together, the current limitations of coagulation–flocculation can be grouped into four main categories: (i) sludge management and valorization, (ii) adaptability to complex effluents via hybrid processes, (iii) economic optimization of coagulant sourcing and use, and (iv) rigorous control of environmental and health impacts. Addressing these interconnected challenges requires a systemic shift in treatment practices, driven by technological innovation, diversification of coagulant sources, and intelligent integration into multi-barrier treatment chains—a transition explored in the following section.

The table below (cf. Table 3) summarizes the main scientific gaps, technological limitations, and current challenges concerning the coagulation–flocculation process in industrial water treatment, as identified in recent literature.

Table 3.

Summary of Scientific Gaps, Technological Limitations, and Current Challenges in Coagulation–Flocculation for Industrial Wastewater Treatment.

4.3. Current Challenges and Open Questions

Building on the previously identified scientific gaps and technological constraints, it becomes clear that the future of coagulation–flocculation will depend on how effectively the research community addresses a series of unresolved questions. These challenges are not confined to laboratory optimization; they touch upon the broader imperatives of environmental sustainability, economic feasibility, operational resilience, and regulatory legitimacy.

One of the most pressing issues is the design of coagulants that reconcile high efficiency with environmental safety and affordability. Traditional metallic salts are effective but carry a heavy ecological burden, from their energy-intensive production to the accumulation of residual metals in sludge. Research is therefore shifting toward multifunctional bio-based and hybrid coagulants, which aim to combine the biodegradability and low toxicity of natural polymers with the robustness of inorganic agents [141]. Studies such as Zaharia et al. confirm that hybrids derived from natural extracts can achieve high color and COD removal, but the scalability and reproducibility of these formulations remain uncertain [152]. Beyond performance, a crucial open question is how to ensure consistent quality and shelf stability of bio-derived coagulants, especially when sourced from variable agricultural or marine biomass.

Another challenge relates to the operational optimization and digitalization of coagulation–flocculation. Laboratory-scale work has already demonstrated the potential of statistical tools like RSM to fine-tune parameters, achieving removal efficiencies above 90% [153]. However, the real breakthrough will come from the integration of smart sensors, real-time monitoring, and machine learning algorithms to dynamically adjust coagulant dosing under fluctuating water qualities. This perspective aligns with the broader paradigm of Industry 4.0 for water treatment, where coagulation is no longer a static process but part of a self-adaptive treatment train. Yet, the cost of advanced instrumentation and the lack of skilled personnel to manage such systems present barriers that cannot be overlooked.

Equally important is the integration of coagulation with complementary advanced technologies. Alone, coagulation cannot fully address persistent organic pollutants, pharmaceuticals, or PFAS. Recent successes with cavitation, ozonation, or direct membrane distillation underscore the potential of hybrid approaches to tackle these contaminants more comprehensively [147,154]. Beyond pollutant removal, such integration also promises reduced sludge volumes and enhanced energy efficiency when processes are designed synergistically. Nevertheless, hybrid systems must be carefully engineered to avoid simply shifting the burden—for example, from sludge management to higher energy demands. This raises an open question: can next-generation hybrid systems achieve true resource recovery (e.g., recovery of nutrients, reuse of treated water, valorization of sludge) rather than just pollution removal?

A further dimension concerns the holistic assessment of coagulation–flocculation systems. While bench-scale studies frequently highlight impressive removal efficiencies, few consider the full life cycle costs and impacts, from raw material sourcing to end-of-life sludge disposal. Zaki et al. argue that, without robust life cycle assessments (LCA) and techno-economic evaluations, many “green” coagulants risk being unsustainable at scale [155]. A more comprehensive framework must include not only greenhouse gas emissions and energy use but also social and economic indicators such as affordability for low-income communities and resilience against supply chain disruptions.

Beyond environmental performance, the large-scale viability of novel coagulants is ultimately determined by their techno-economic balance between synthesis complexity, operational efficiency, and cost competitiveness. While laboratory-scale studies frequently report remarkable removal efficiencies, the translation of these results to industrial practice remains hindered by the high cost of reagents, process energy, and limited regeneration capacity. Recent techno-economic evaluations have demonstrated that optimized electrocoagulation systems can achieve treatment costs as low as 1.5 USD m−3 when operated under energy-efficient regimes, offering a competitive alternative to conventional alum- or ferric-based treatments [156]. Similar assessments on hybrid processes coupling coagulation with thermochemical valorization pathways—such as pyrolysis or hydrothermal carbonization—suggest that the integrated recovery of coagulant metals and energy carriers could reduce the overall life-cycle cost by 20–30% while closing material loops [157]. Nevertheless, the synthesis and stabilization of advanced nanostructured or functionalized coagulants often rely on costly precursors, and their economic feasibility depends on developing scalable, solvent-free, and modular production methods. Standardized cost models and techno-economic metrics are therefore required to harmonize future assessments and to identify thresholds beyond which hybrid or biosourced coagulants can become not only environmentally but also economically sustainable.

Finally, the regulatory landscape remains a decisive factor shaping adoption. Many natural and hybrid coagulants still lack approval for use in potable water treatment, partly due to uncertainties around toxicological safety, microbiological risks, and by-product formation. Aragaw and Bogale highlight the urgent need for harmonized international standards that could accelerate market access for bio-based coagulants while maintaining public health safeguards [31]. Beyond compliance, there is also the question of public perception and acceptance: how willing are communities to embrace coagulants derived from agricultural waste, marine biomass, or nanomaterials? Addressing this socio-regulatory dimension is as crucial as solving technical inefficiencies.

In essence, the coagulation–flocculation field now stands at a crossroads. Progress will depend on its ability to move beyond narrow efficiency metrics toward a multidimensional approach that integrates green chemistry, digital process control, hybrid system design, life cycle sustainability, and adaptive regulation. Only by tackling these open questions in concert can the next generation of coagulants deliver truly sustainable solutions for complex wastewater treatment.

5. Recommendations and Future Perspectives

In light of the challenges identified around mechanistic understanding, coagulant design, and sustainable industrial deployment, a strategic synthesis is warranted. The following distinguishes near-term, operational recommendations from medium- to long-term, disruptive perspectives.

5.1. Immediate and Practical Recommendations

5.1.1. Research Directions

A priority is the fine-scale exploration of interactions between coagulants and pollutants, especially at the molecular level. Recent molecular modelling work has, for example, examined five plant-derived coagulant proteins (Moringa oleifera, Arachis hypogaea, Bertholletia excelsa, Brassica napus, Helianthus annuus) and highlighted the decisive role of specific amino-acid residues in coagulation. Hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions dominate aggregation mechanisms, and proteins from Brassica napus and Helianthus annuus can outperform the well-known Moringa oleifera protein depending on treatment conditions [158,159]. These results confirm the need to characterize, at molecular resolution, adsorption and charge-neutralization phenomena.

Building on this, advanced structural analytics are essential to elucidate functional interactions at the surface of natural coagulants. Techniques such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Raman spectroscopy provide insight into the structure and active groups of biopolymer coagulants. For example, combining FTIR, SEM and dynamic light scattering (DLS) enabled detailed characterization of a seed gum extracted from Cassia fistula. At pilot scale (30 L reactor), this natural coagulant achieved pollutant removals up to ~93.8% at an optimized dose of 1.17 mg L−1 [160]. Such studies show that in-depth physicochemical characterization (morphology, molecular weight, functional sites) helps target dominant action mechanisms (H-bonding, bridging, etc.) and improve the performance of bio-based coagulants.

To enable reliable comparison of alternative versus conventional mineral coagulants, standardized experimental protocols are critical. Methodologies combining zeta-potential measurements with statistical design of experiments have proven effective for optimizing coagulation conditions. A case study showed that, by finely tuning the dose of a cationic polymer (polydadmac), one can reach near-complete removal of turbidity and suspended solids at precisely defined dosages—i.e., once optimal charge neutralization is achieved, floc formation maximizes clarification [161]. Extending these methodological efforts—e.g., through inter-laboratory standardized tests—will close fundamental gaps and make results more comparable and transferable.

Beyond classical views, some authors propose broadening coagulation mechanistic concepts by introducing co-adsorption [162]. This integrates coagulation, adsorption, and agglomeration effects to reflect the multifactor complexity of heterogeneous systems. A specific co-adsorption indicator has been suggested to quantify and predict coagulant efficiency against given pollutant classes. This holistic (yet emergent) approach deserves further study, as it could sharpen predictive models and support dose setting under complex conditions.

Development of Innovative Coagulants

Innovation in coagulants is a major lever for more effective, sustainable, and environmentally safe water treatment. A near-term strategic avenue is controlled chemical modification of natural biopolymers such as chitosan, tannins, or plant proteins. Such modifications have already produced higher-performance hybrid materials: for instance, carboxymethyl grafting onto cellulosic matrices stabilizes Ag and CuO nanoparticles while imparting long-lasting antimicrobial action [163]. Likewise, functionalizing chitosan—a polysaccharide from crustacean waste—with inorganic nanoparticles markedly improves its thermal stability and charge-dispersion capacity. Hybrid membranes combining chitosan with modified nano-silica display enhanced thermal stability and optimized charge dispersion, particularly around ~3 wt% nano-silica [164]. Leveraging such organo-mineral hybrid coagulants is promising because it exploits synergies among adsorption, ionic complexation, and floc formation to target a broad pollutant spectrum.

Nanotechnology also opens new avenues for “smart” coagulation systems. Embedding magnetic nanoparticles within microspheres functionalized with coagulant proteins (e.g., from Moringa oleifera) optimizes capture of colloids and enables floc recovery by applying an external magnetic field [165]. Researchers have engineered superparamagnetic microspheres grafted with Moringa proteins that act as coagulants and can be extracted post-use with a magnet. This recoverability and reusability, along with low reagent demand, are major assets for reducing OPEX and environmental impacts.

Finally, stimuli-responsive composite materials open the way to adaptive coagulants. By combining natural biopolymers with inorganic fillers that respond to external stimuli (pH, temperature, magnetic field), one can devise “smart” coagulants that adjust conformation and reactivity to the medium. For example, pH-responsive particles may reversibly shift solubility or charge. These multifunctional systems—still at research stage—could offer unprecedented control over coagulation by modulating efficiency in real time as influent composition varies.

Integration into Industrial Treatment Trains

In industry, overall performance hinges on coherently orchestrating multiple technologies. It is therefore judicious to embed coagulation as a key step within larger treatment trains rather than treating it in isolation. Many studies show that coupling coagulation–flocculation with membrane processes (UF/MF/NF) significantly reduces fouling, extends equipment lifetime, and improves product water quality [166]. Dosing a coagulant upstream of UF limits pore blocking and cake resistance by precipitating colloids, easing cleaning and maintaining flux. This benefit is especially marked for industrial effluents rich in persistent organics or colloids (e.g., food & beverage, fine chemicals).

Similarly, combining coagulation with advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) is promising for refractory pollutants. Sequences such as coagulation + ozonation or coagulation + UV/H2O2 achieve higher removals of difficult compounds (e.g., dyes, pesticides) than either step alone, by (i) removing a large fraction of COD and solids first and (ii) oxidizing the remaining dissolved organics more efficiently—often with lower overall sludge generation due to synergy.

To enable broader adoption of such hybrid systems, comprehensive technical guides should be made available to operators. These should specify optimal operating windows for each combined technology (coagulant dose, contact times, filtration/oxidation settings), outline automation strategies, define compatible control systems (SCADA, PLCs), and list real-time KPIs (turbidity, UV254, etc.). Near-term dissemination of such operational know-how can remove adoption barriers for alternative coagulants and hybrid trains across sectors facing increasingly strict discharge limits.

5.2. Long-Term Perspectives

5.2.1. Toward Intelligent Coagulation

Progress toward intelligent treatment systems is among the most promising axes for simultaneously boosting effectiveness and sustainability. With online sensors and AI algorithms, automated, adaptive, and predictive coagulant dosing is now feasible. In practice, systems continuously measure influent quality (turbidity, organics, pH, etc.) and adjust dose in real time, anticipating variations rather than reacting late. Full-scale trials in Norway illustrate this potential: implementing multi-parameter predictive control stabilized plant performance despite influent variability while reducing coagulant consumption by up to ~30%—a dual economic and environmental gain via lower reagent use and less sludge production [167].

In parallel, cloud/IoT architectures are transforming infrastructure. Connected supervisory platforms embed predictive models within industrial control (e.g., SCADA). A recent platform leverages deep-learning models (deep belief networks) tied to an IoT sensor network to optimize WWTP operation continuously [168]. IoT–SCADA integration enables proactive control: early detection of drifts (organic surges, overflow risk) triggers automatic adjustments (dose increases, flow regime shifts) before effluent quality degrades—and reduces downtime through predictive maintenance.

A notable advance is the emergence of soft sensors (virtual sensors). These model-based or ML estimators instantly infer quality parameters (e.g., clarifier effluent turbidity) before sedimentation completes. One such soft sensor predicted settled-water turbidity from inlet conditions and unit hydrodynamics [169]. Validated on site, it achieved ~86% accuracy and, crucially, provided an early estimate—allowing dose adjustments without waiting for hours-long settling. This responsiveness stabilizes operations and reduces prolonged under- or over-dosing.