Abstract

The ever-increasing needs of the working population have led to the development of various branches of industry, an increase in the number of employees, and a rise in the number of work-related accidents. The welder occupation is one of the most sought after occupations in Europe, according to the EURopean Employment Services (EURES) statistics. Taking into account the work system in which welders conduct their activity (uncomfortable working positions, splashes, high temperatures, mechanical factors, gases and fumes, magnetic fields due to electric current), the paper presents the risk factors identified for the welder occupation, based on the occupational injury and illness risk assessments. Following the analysis of 25 risk assessments, carried out by the assessment team that must include qualified evaluators, process specialists, the workers’ representative, occupational health and safety responsible at various industrial economic agents, a total of 70 main risk factors of occupational accidents and diseases were identified for the welder occupation. Risk factors were classified according to four main work components: worker, workload, work environment, and means of production. To reflect the importance of the identified risk factor, the number of organizations that considered that the risk was likely to occur but also the possibility that the risk was above the acceptable limit, calculated using the National Institute for Research and Development for Labor Protection “Alexandru Darabont” (INCDPM) method, a method often used in Romania, was identified from the analyzed assessments. Finally, a prevention and protection plan was drawn up with regard to the risks identified for the welder occupation, the final aim of which was to respectively reduce the probability of occurrence with the severity of the risks identified.

1. Introduction

The labor market in European Union (EU) countries has maintained its growth despite the problems the economies have been going through, especially in the second part of 2022, problems caused by the armed conflict in Eastern Europe, which has led to massive increases in energy prices, supply chain disruptions, and therefore increases in the cost of living [1]. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth overlapped the total employment growth by 2.0% in the EU and by 2.3% in the Euro area. Thus, in 2022, the number of people employed in the EU was 213.7 million, of which 166.1 million were in the Euro area. The highest increases in persons employed were recorded in Ireland (+6.6%), Malta (+6.3%), and Lithuania (+5.1%), with the lowest in Romania (+0.1%), Poland (+0.4%), Germany, and Bulgaria (+1.3%) [2].

According to the Romanian National Institute of Statistics (RNIS), at the end of 2022, in Romania, there were 8051 million people entitled to work, of which 7.812 million were employed and 239,100 unemployed [3].

Metal fabrication and welding are essential in many industries and sectors of the economy: construction, manufacturing, infrastructure, defense, energy, aerospace, marine, medical, mining, and food processing.

Welding is a fundamental industrial process in the industries above-mentioned, serving as a critical fabrication process in creating durable structures. The welding process involves the fusion of materials, typically metals or thermoplastics, by using high heat to melt the parts together.

The fusion and melting welding process is among the most dangerous activities in metal fabrication. The welding process involves working with high heat, intense light, and different materials, which can pose significant risks to the welder’s health and safety. For this reason, it is important to identify these hazards to ensure the implementation of proper safety protocols [4,5,6].

A welder is a skilled professional who uses various tools and equipment to join metal pieces or parts by heating the surfaces to the point of melting them, and then fusing them together to form a strong permanent bond. A welder’s responsibility can involve a variety of industries including civil and industrial construction, capital repairs and maintenance, heavy industry, automotive, manufacturing, and other industrial sectors. Therefore, a welder must have detailed knowledge of mechanics, physical science, metallurgy, and safety procedures.

Based on the names of the main industrial branches that use welders in production, the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE) and Classification of Activities in the National Economy in Romania (CAEN) codes specific to these branches were identified in the paper. Table 1 presents the classification of the industrial branches of civil and industrial construction, capital repair and maintenance, heavy industry, and automotive manufacturing in the NACE and CAEN codes.

Table 1.

Classification of industrial branches of civil and industrial construction, capital repair and maintenance, heavy industry, and automotive manufacturing in the NACE and CAEN codes.

Within these industrial branches, there is a trend toward the use of welding processes to produce welded joints of materials with improved properties specific to different applications (medical, aerospace, etc.) [7,8,9] as well as toward the use of new manufacturing processes [10,11,12], which imply the possibility of new risks specific to the welding occupation.

European Union occupational safety and health (OSH) legislation is important to ensure the health and safety of EU workers at work. Thus, to achieve safe and healthy workplaces [13] for all workers, an important element related to the workplace is the possibility to protect them against health and safety risks [14]. In the case of OSH, defined as the science of anticipating, identifying, assessing, and controlling hazards occurring in the workplace that could affect the health and safety of workers [15], accidents at work are the most important areas for action in EU social policy.

Occupational accidents generate both direct costs (which can be directly attributed to expenses resulting from the consequences of an accident and recorded in the organization’s accounting system) and indirect costs (which result from the accident but are not allocated and accounted by the employer) [16,17,18,19], costs that are analyzed in terms of the number of working days lost, damage caused, medical, administrative and recruitment costs (to compensate for the production incapacity caused by the lack of manpower as a consequence of the work accident), costs linked to the loss of job welfare, loss of the organization’s reputation, etc.

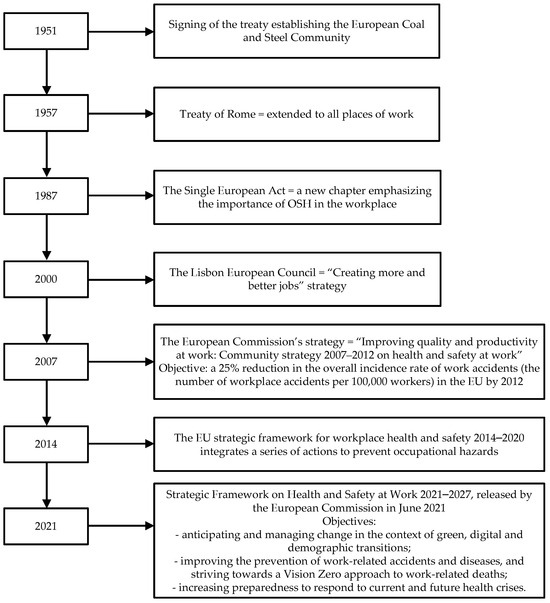

Improving workplace safety policies has been a major concern at the global, European, and later EU level, with a gradual development, as presented in Figure 1 [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Figure 1.

Stages of improving workplace policies in Europe and later in the EU.

A work accident is defined, according to the ESAW methodology, as “a discrete occurrence in the course of work which leads to physical or mental harm (injury to the worker)”. The phrase ‘in the course of work’ means ‘while engaged in an occupational activity or during the time spent at work’. A ‘fatal accident’ means an accident that leads to the death of a victim within one year of the accident. Non-fatal workplace accidents or serious accidents at the workplace involve at least four complete days of absence from work [22,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

The overall costs of occupational accidents and diseases are often much higher than initially perceived at the organizational level. Organizations need to increase their investment in occupational safety and health including safety culture, thereby aiming to reduce both the direct and indirect costs while lowering insurance premiums and absenteeism and improving worker performance, productivity, and morale [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Work accidents are a challenge for economic sectors defined by the NACE code [31,33,37,38,39,42,55,56,57] (e.g., agriculture, forestry, and fishing, manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail trade; transport and storage, etc.). In the EU, the number of non-fatal work accidents in 2021 was 2,886,507, with the most recorded in Germany (810,127 accidents), France (655,024 accidents), and in Spain (457,435 accidents), while Romania ranked 25th with 2779 non-fatal work accidents recorded. In terms of fatal accidents, in the same year, out of a total of 3347 fatal accidents, France ranked first with 674 fatal accidents, Italy second with 601 accidents, and Germany third with 435 accidents, while Romania ranked sixth with 172 fatal accidents [32,43,58,59].

The main objective of this paper was to identify and analyze the risks for the welder occupation in Romania, which can be extended to the EU level. The novelty of the research presented in the paper consists of identifying the risk factors related to the welder occupation in Romanian organizations. Following the identification of the risk factors, a prevention and protection plan was proposed (depending on the national strategy in accordance with the European strategy) to minimize the probability of occurrence as well as the severity of the identified risk factors by taking technical, organizational, hygienic, and sanitary measures. The final part of the paper presents the distribution of the identified risks by each component of the work system.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper was based on a research methodology used to identify the risk factors associated with the welder occupation in Romania that consisted of:

- Identification and consultation of the health and safety national legislation;

- Identification of the national methodology regarding the calculation of the risk levels;

- Identification of the potential risk factors related to the welder occupation;

- Grouping the potential risk factors previously identified;

- Elaboration of a form regarding the potential risk factors related to the welder occupation;

- Organizing face-to-face meetings with representatives of the organizations carrying out welding activities, aiming to establish a risk level for welder occupation;

- Conceiving a database with the answers gathered during the face-to-face meetings;

- Use of the mathematical relations presented in the national methodology, based on the severity and probability classes of events, to establish the risk level;

- Interpretation of the results;

- Elaboration of the protection and prevention plan regarding the risks identified.

The paper contains the results of the research carried out in Romania with the aim:

- To identify the main risk factors specific to the workplace in which the welders carry out their activities, based on the method developed by the National Institute for Research and Development for Labor Protection “Alexandru Darabont” (INCDPM, Bucharest, Romania) which is the most widely used method for risk assessment at workplaces in Romania. The general principles relating to the prevention of occupational risks, the protection of the workers’ health and safety, and the elimination of risk and injury factors are set out in Romania in Law no. 319 of 14 July 2006 on occupational safety and health [60,61,62,63].

According to the stipulations of this law, the employer has the obligation:

- “to assess the risks for workers’ health and safety, including the choice of work equipment, chemical substances or preparations used and the layout of workplaces” (Law 319/2006 art. 7, para. 4, letter a);

- “that, following the [risk] assessment and if necessary, the prevention measures and the working and production methods applied by the employer ensure an improvement in the level of safety and health protection of workers and are integrated into all the activities of the undertaking and/or establishment concerned and at all hierarchical levels” (Law 319/2006 art. 7, para. 4, letter b).

Additionally, according to Law 319/2006 art. 12, para. 1, lit. (a), the employer has the obligation “to carry out and be in possession of an occupational safety and health risk assessment, including for those groups sensitive to specific risks”. Concerning the health and safety conditions at work, the prevention of accidents and occupational diseases, employers are required by Law 319/2006 art. 13, letter b “to draw up a prevention and protection plan consisting of technical, sanitary, organizational and other measures, based on risk assessment, to be applied in accordance with the specific working conditions of the establishment”.

The methodological rules for the application of the provisions of the Law on Safety and Health at Work No. 319/2006 were approved by Government Decision (GD) no. 1425 of 11 October 2006 [61,62,64], which also contains articles on risk assessment:

- The prevention and protection activities carried out in the enterprise and/or establishment are the following: “hazard identification and risk assessment for each component of the work system, i.e., the worker, the workload, the means of production/work equipment and the work environment at the workplace/workstations” (GD 1.425/2006 art. 15, p. 1, point 1);

- “following the risk assessment for each workplace/workstation, prevention and protection measures of a technical, organizational, hygienic-sanitary and other nature necessary to ensure the safety and health of workers shall be established” (GD no. 1425, art. 46, para. 2); the prevention and protection plan shall be revised whenever changes in working conditions occur, when new risks arise, and following the occurrence of an event (GD no. 1425, Article 46(1));

According to Law No. 319/2006 on occupational safety and health, the definitions of the terms for each component of the work system are:

- Work equipment—Any machine, apparatus, tool or installation used in work;

- Performer = The worker who carries out the work task;

- Work task = Totality of actions to be performed by the worker through the means of production to achieve the purpose of the work system;

- Work environment = Component of the work system consisting of the totality of the physical, chemical, biological, and psychosocial conditions in which the worker carries out their activity.

Based on the legal requirements on risk assessment presented above, in Romania, the most widely used method for assessing the risks of occupational injury and illness is the INCDPM method, developed by INCDPM. This method was endorsed by the Ministry of Labor and Social Solidarity in 1993 and has been tested to date in most industries, with continuous improvements [65,66,67,68].

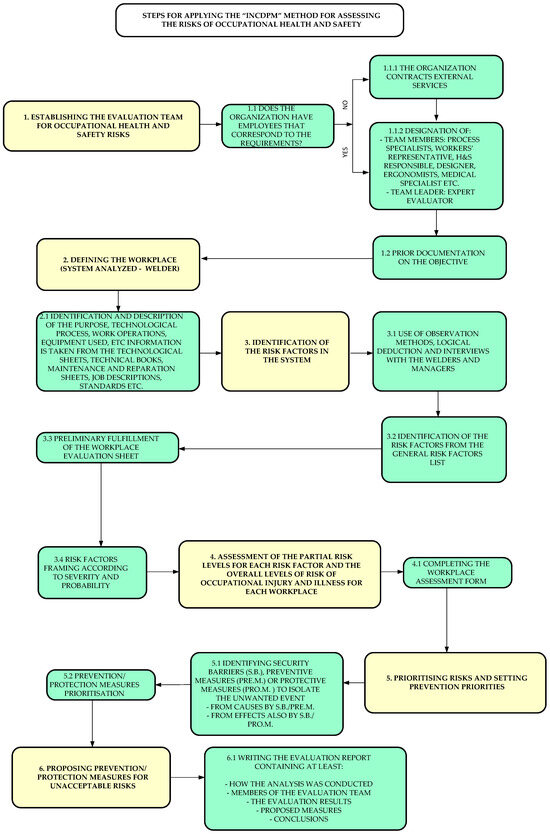

Figure 2 presents the mandatory steps contained in the INCDPM’s risk assessment for occupational injury and illness.

Figure 2.

Mandatory steps of the INCDPM method for assessing the risks of occupational health and safety.

The steps shown in Figure 2 are carried out by an analysis and assessment team that is made up of occupational safety specialists and technologists, knowledgeable about the work processes being analyzed, and coordinated by an authorized risk assessor.

The risk level is a combination of the severity of the consequences and the probability of occurrence, both of which are classified into the following classes:

- Severity:

- ▪

- Class 1: Negligible consequences (work incapacity for less than 3 days);

- ▪

- Class 2: Minor consequences (3 to 45 days of work incapacity—DWI, requiring medical treatment);

- ▪

- Class 3: Medium consequences (45 to 180 days of work incapacity, medical treatment and hospitalization);

- ▪

- Class 4: High consequences (Grade III disability):

- ▪

- Class 5: Serious consequences (Grade II disability);

- ▪

- Class 6: Very serious consequences (Grade I disability);

- ▪

- Class 7: Maximum consequences (death).

- Event probability:

- ▪

- Extremely rare: P < 10−7 /h; probability class 1;

- ▪

- Very rare: 10−7 < P < 10−5 /h; probability class 2;

- ▪

- Rare: 10−5 < P < 10−4 /h; probability class 3;

- ▪

- Uncommon: 10−4 < P < 10−3 /h; probability class 4;

- ▪

- Common: 10−3 < P < 10−2 /h; probability class 5;

- ▪

- Very common: P > 10−2 /h. probability class 6.

By combining the severity (m) and probability classes of events (n), we obtain the matrix (m,n), and the risk level ranging from 1 to 7 ( ), according to Table 2.

), according to Table 2.

), according to Table 2.

), according to Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk level assessment matrix.

Following the assessment of the risks of injury and occupational illness, the members of the assessment team established a level of severity and probability of occurrence for each identified risk, and the combination of these two elements, according to Table 2, resulted in the risk level for that identified risk.

The INCDPM method states that for Romania, the maximum accepted value for the risk level is ➂, according to Table 2.

3. Research on Risk Factors Specific to the Welding Occupation in Romania

Considering the statistics presented above on the number of fatal and non-fatal work accidents in the EU and Romania, to reduce the probability of occurrence and the severity of work accidents, in this paper, the risk factors and their distribution on each component of the work system within the industrial fields for the welder occupation were identified.

Considering the requirements set out in Government Decision 1.425/2006 art. 15, para. 1, para. 1 regarding hazard identification and risk assessment for each component of the work system respectively the worker, the workload, means of production/work equipment and the working environment [68] for the welder occupation, the results of 25 risk assessments carried out in organizations using welders in the work process were analyzed.

Following the analysis of the 25 assessments carried out by the evaluation team that had to include expert evaluators, process specialists, workers’ representative, health and safety responsible at various industrial economic agents, a total of 70 occupational injury and illness risks for welders were identified, whose distribution by each component of the work system is shown in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The main components of a workplace are the worker, the workload, the working environment, and the means of production.

Table 3.

Distribution of risk factors related to the worker.

Table 4.

Distribution of workload-related risk factors.

Table 5.

Distribution of risk factors related to the work environment.

Table 6.

Distribution of risk factors related to the means of production.

Team members had a detailed knowledge of the evaluation method, the tools used, and the working procedures. Prior documentation of the objective was also carried out. The team of evaluators may include, depending on the needs, designers, ergonomists, medical specialists from the unit, etc. The team leader is the expert evaluator qualified according to national legislation.

Based on the INCDPM methodology, as presented in Section 2, each identified risk is assigned a severity level or probability of occurrence from this combination, resulting in the risk level for that identified risk.

From the point of view of the methodology presented, the risks identified above the limit of ➂, the acceptable limit value in Romania, implies an obligation for the organization to identify and implement specific measures to reduce either the severity or the probability of the occurrence of those risks.

Table 3 presents the risk factors related to the executant (welder) analyzing the risks from the point of view of wrong actions or omissions of the executant in the manufacturing process.

From the point of view of the risk factors related to the executant, one can observe that the main risk factor was “ Non-use of the personal protective equipment and other means of protection provided”, a factor that was identified in all of the organizations analyzed and had a risk level above the acceptable limit in more than half of the organizations. Additionally, a high number of risks generated by the wrong actions of the worker [23] was observed, which represents 32.8% of the total number of risks related to the welder occupation.

Another important risk factor was “falling from the same level by tripping, unbalancing, slipping” and the lowest percentage identified was in “poor communication due to noise”. For the two risk factors identified, none of the analyzed organizations considered presented a risk level above the acceptable limit. For the “Use of aprons, gloves, shoe soles, etc. to counteract the fire on the pipe effect” risk factor, this was identified in 8% of the organizations analyzed, and all of them identified it as having a risk level above the acceptable limit.

The workload can cause risk factors to arise during the manufacturing process. Thus, the inadequate or incomplete presentation of the workload or the inadequacy of the workload to the capacity of the worker (welder) can lead to work accidents.

From the workload point of view, the risk factor “Wrong operations, rules, procedures—absence of some operations indispensable for work safety”, although identified in few organizations (28%), represented a risk level above the acceptable limit in 42.8% of these organizations. The risk factor of diseases due to forced working positions or those caused by manual lifting and carrying of various components was a risk identified in most of the cases analyzed.

The working environment is one of the main elements that can influence the occurrence of accidents at work for the welder occupation. Workplace risk factors can be managed by improving the working conditions and creating an environment suitable for the production process.

From the analysis of Table 5, one can observe that, for the welder occupation, the risks of illness caused by ambient temperature, natural disasters. and poisoning have been identified in many organizations (over 76% of those analyzed). Considering the nature of the materials used in welding processes, the risk of fire/explosion is high, being identified with a risk level above the acceptable limit in 30% of the organizations analyzed.

From the point of view of the risk factors related to the means of production, it is necessary that all production equipment is subject to verification, maintenance, or overhaul processes, according to the established planning. If all the means of production operate within the parameters defined by the manufacturer, the risk of accidents at work is greatly reduced.

During welding processes, the use of inappropriate means of production can increase the risk of accidents at work. Thus, electrocution by direct contact with uninsulated cables was a risk factor identified in all of the organizations analyzed, and in 40% of the organizations, this risk was above the acceptable limit.

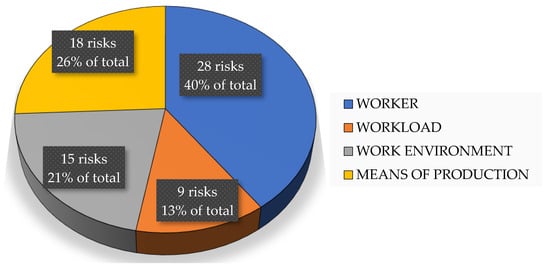

Based on the information presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, Figure 3 presents the distribution of the identified risks by each work system component.

Figure 3.

Distribution of identified risks by work system component.

From Figure 3, one can observe that most of the risks of injury and occupational illness for the welder occupation are those generated by the worker, with 40% of the total number of risks identified.

According to Government Decision No. 1.425 art. 46, para. 2, “following the risk assessment for each workplace/workstation, prevention and protection measures of a technical, organizational, hygienic-sanitary and other nature necessary to ensure the safety and health of workers are established”, a prevention and protection plan must be drawn up, the final aim of which is to reduce the probability of occurrence and the seriousness of the risks identified. To highlight the importance of the measures indicated in the protection and prevention plan, they were also evaluated from the perspective of the hierarchy of controls, according to NIOSH methodology (Table 7), which involves considering the efficiency level, level of action, and action results [69,70].

Table 7.

Hierarchy of controls.

Table 8 shows an extract from the prevention and protection plan, drawn up based on the risks identified following the analysis of the risk assessments.

Table 8.

Prevention and protection plan (extracts).

From the analysis of the information in Table 8, one can observe that providing welders with personal protective equipment and training are the most widely used measures to ensure the safety and health of workers and to reduce the probability of the occurrence and impact of the identified risks.

4. Conclusions

This paper presented the research carried out to identify the main risk factors for the welder occupation in Romania. The results obtained may be used as a starting point in the identification and assessment of risks in organizations where welders carry out their activities.

The analysis of the 70 identified risk factors and their grouping according to the main components of a workplace—the worker (28 factors), the workload (9 factors), the work environment (15 factors), and the means of production (18 factors)—stands as a model to help the representatives of the organizations to reduce or eliminate work accidents involving welders.

The prevention and protection measures presented in this paper can be implemented immediately, without further analysis, in organizations with the aim of ensuring the safety and health of workers.

The measures proposed in the prevention and protection plan were analyzed in terms of effectiveness according to the hierarchy of controls in the NIOSH methodology. Thus, forty-seven were administrative control measures, twelve were measures related to personal protection equipment, eleven were related to engineering controls, two aimed to replace the hazard, and two aimed to physically remove the hazard.

From the point of view of future research, the prevention and protection plan developed will be distributed to each organization participating in the study, with the aim of implementing the recommended measures and performing a new evaluation after 6 months. The results of the new evaluation will provide important information on the effectiveness of the proposed measures, the level of implementation of these measures in each organization, and the implementation approach in each component of the workplace related to the welder occupation.

The limitations in the research are due to the incomplete information reported at the national or EU levels. Another limitation derives from the fact that a portion of work accidents and their causes are not reported in time or are not properly classified, and as a result, the risks are not properly identified either (according to national reports).

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, V.P. and C.R., Methodology, V.P., C.R., D.-T.C. and A.-M.B., Investigation V.P., N.I. and A.B., Writing—review and editing, V.P., C.R., D.-T.C. and A.-M.B., Visualization, A.B. and N.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Prohorovs, A. Russia’s War in Ukraine: Consequences for European Countries’ Businesses and Economies. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2023, European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Directorate F, Manuscript Completed in July 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=26989&langId=en (accessed on 9 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Rădoi, S.; Chicu, A.M. Balanța Forței de Muncă, National Institute of Statistics, 1 Ianuarie 2023. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/balanta_fortei_de_munca_la_1_ianuarie_2023.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Minett, A. What Are the Hazards of Welding? Available online: https://www.chas.co.uk/blog/what-are-the-hazards-of-welding/ (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Martinelli, K. Welding Hazards in the Workplace: Safety Tips & Precautions. Available online: https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/welding-hazards-in-the-workplace/ (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Rontescu, C.; Cicic, D.T.; Amza, C.G.; Chivu, O.R.; Iacobescu, G. Comparative Analysis of the Components Obtained by Additive Manufacturing Used for Prosthetics and Medical Instruments. Rev. Chim. 2017, 68, 2114–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, I.; Geanta, V.; Stefanescu, E.V.; Simion, G.; Scutelnicu, E. Effect of Diffusion on Dissimilar Welded Joint between Al0.8CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy and S235JR Structural Steel. Metals 2022, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontescu, C.; Chivu, O.R.; Cicic, D.T.; Iacobescu, G.; Semenescu, A. Analysis of the surface quality of test samples made of biocompatible titanium alloys by sintering. Rev. Chim. 2016, 67, 1945–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Zapciu, A.; Amza, C.G.; Rontescu, C.; Tasca, G. 3D-Printed, Non-assembly, Pneumatically Actuated Mechanisms from Thermoplastic Materials. Mater. Plast. 2018, 55, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amza, C.G.; Zapciu, A.; Eythorsdottir, A.; Bjornsdottir, A.; Borg, J. Embedding Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene Fibers in 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid (PLA) Parts. Polymers 2019, 11, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laszlo, E.A.; Crăciun, D.; Dorcioman, G.; Crăciun, G.; Geantă, V.; Voiculescu, I.; Cristea, D.; Crăciun, V. Characteristics of Thin High Entropy Alloy Films Grown by Pulsed Laser Deposition. Coatings 2022, 12, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- British Safety Council. Who Is Responsible for Workplace Health and Safety? Available online: https://www.britsafe.org/training-and-learning/informational-resources/who-is-responsible-for-workplace-health-and-safety (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Alli, B.O. Fundamental Principles of Occupational Health and Safety, 2nd ed.; International Labour Office—ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, L.; Simon, L. Costs of construction accidents to employers. J. Occup. Accid. 1987, 8, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, D.; Solomon, G.; Dijmărescu, M.C. Costs calculation of an work accident in a production hall for metallic confections. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 564, 012099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Inventory of Socioeconomic Costs of Work Accidents; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, Belgium, 2002; Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/TE3701623ENS_-_Inventory_of_socioeconomic_costs_of_work_accidents.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Battaglia, M.; Frey, M.; Passetti, E. Accidents at work and costs analysis: A field study in a large Italian company. Ind. Health 2014, 52, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators Database. Labor Force, Total—European Union. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.IN?end=2022&locations=EU&most_recent_year_desc=true&start=1990&view=chart (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- European Commission. Commission Report Finds Labour and Skills Shortages Persist and Looks at Possible Ways to Tackle Them, July 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_3704 (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. EU strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work 2021–2027, Occupational Safety and Health in a Changing World of Work, Brussels. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0323 (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Ivascu, L.; Cioca, L.-I. Occupational Accidents Assessment by Field of Activity and Investigation Model for Prevention and Control. Safety 2019, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament, Treaty of Rome (EEC). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/in-the-past/the-parliament-and-the-treaties/treaty-of-rome (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- European Parliament, Single European Act (SEA). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/in-the-past/the-parliament-and-the-treaties/single-european-act (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- EUR-LEx, Growth and Jobs. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/growth-and-jobs.html (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- EUR-LEx, Community Strategy on Health and Safety at Work (2007–2012). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/community-strategy-on-health-and-safety-at-work-2007-2012.html (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- European Commission. Health and Safety at Work: New EU Strategic Framework 2014–2020—Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_14_400 (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Iavicoli, S. The new EU occupational safety and health strategic framework 2014–2020: Objectives and challenges. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Heal that Work. EU Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work 2021–2027. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/safety-and-health-legislation/eu-strategic-framework-health-and-safety-work-2021-2027 (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Lafuente, E.; Daza, V. Work inspections as a control mechanism for mitigating work accidents in Europe. TEC Empresarial 2020, 14, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambra, L.; Frenda, A. Estimating accidents at work in European Union, electronic journal of applied Statistical Analysis: Decision Support Systems and Services Evaluation. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. Decis. Support Syst. Serv. Eval. 2012, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rađenović, T. Analysis of the accidents at work in the European Union. Facta Univ. Ser. Work. Living Environ. Prot. 2023, 20, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenda, A. A statistical analysis of accidents at work in the international context. Econ. Serv. Soc. Ed. Mulino 2011, 2, 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW)—Summary Methodology; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5926181/KS-RA-12-102-EN.PDF (accessed on 30 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kania, A.; Cesarz-Andraczke, K. Statistical analysis of accidents at work in the selected manufacturing enterprise. Sci. Pap. Sil. Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2023, 176, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K. Serious work accidents and their causes—An analysis of data from Eurostat. Saf. Sci. Monit. 2015, 19, Article-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrevski, V.; Geramitcioski, T.; Mijakovski, V.; Lutovska, M.; Mitrevska, C. Situation regarding accidents at work in the European union and in the Republic of Macedonia. Ann.-J. Eng. 2015, 13, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrevska, C.; Mitrevska, E.; Mitrevski, V. Statistical indicators for accidents at work in construction sector. Ann. Fac. Eng. Hunedoara 2022, 1, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Holla, K.; Ďad’ová, A.; Hudakova, M.; Valla, J.; Cidlinova, A.; Osvaldova, L.M. Causes and circumstances of accidents at work in the European Union, Slovakia and Czech Republic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1118330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inspectia Muncii. Ghid de Evaluare a Riscului. Available online: https://www.inspectiamuncii.ro/documents/66402/260290/Ghid+de+evaluare+a+riscului/ef2d66c3-68a5-42bd-8b8d-ae447daca8c7 (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Jukka, T. Global Estimates of Fatal Occupational Accidents. Epidemiology 1999, 10, 640–646. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, M.; Fargnoli, M.; Parise, G. Risk Profiling from the European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW) Accidents′ Databases: A Case Study in Construction Sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowacki, K. Accident Risk in the Production Sector of EU Countries—Cohort Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, D. Social, Cultural and Working Conditions Determinants of Fatal and Non-Fatal Occupational Accidents in Europe. Sigurnost 2020, 62, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Global Trends on Occupational Accidents and Diseases. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/legacy/english/osh/en/story_content/external_files/fs_st_1-ILO_5_en.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Maharja, R.; Tualeka, A.; Suwandi, T. The analysis of safety culture of welders at shipyard. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodzicka, A. Assessing Risky Behaviors Based on the Indicator Analysis of Statistics on Accidents at Work. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2023, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comberti, L.; Demichela, M.; Baldissone, G.; Fois, G.; Luzzi, R. Large Occupational Accidents Data Analysis with a Coupled Unsupervised Algorithm: The S.O.M. K-Means Method. An Application to the Wood Industry. Safety 2018, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.J. Impact of Construction Safety Culture and Construction Safety Climate on Safety Behavior and Safety Motivation. Safety 2021, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhavilas, P.K.; Koulouriotis, D.E. Risk-Acceptance Criteria in Occupational Health and Safety Risk-Assessment—The State-of-the-Art through a Systematic Literature Review. Safety 2021, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Merchán, M.d.C.; López-Arquillos, A. Influence Variables in Occupational Injuries among Men Teachers. Safety 2022, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miño-Terrancle, J.; León-Rubio, J.M.; León-Pérez, J.M.; Cobos-Sanchiz, D. Leadership and the Promotion of Health and Productivity in a Changing Environment: A Multiple Focus Groups Study. Safety 2023, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoine, E.; Jansz, J.; Barifcani, A.; Shaw-Mills, S.; Harris, M.; Lagat, C. Psychosocial Safety and Health Hazards and Their Impacts on Offshore Oil and Gas Workers. Safety 2023, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margheritti, S.; Negrini, A.; da Silva, S.A. There Is Hope in Safety Promotion! How Can Resources and Demands Impact Workers’ Safety Participation? Safety 2023, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, List of NACE Codes. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/competition/mergers/cases/index/nace_all.html (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Cieslewicz, W.; Araszkiewicz, K.; Sikora, P. Accident Rate as a Measure of Safety Assessment in Polish Civil Engineering. Safety 2019, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Occupational Safety and Health in Europe: State and Trends. 2023. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/occupational-safety-and-health-europe-state-and-trends-2023 (accessed on 18 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW). Non-Fatal Accidents at Work by NACE Rev. 2 Activity and Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hsw_n2_01/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Eurostat European Commission. European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW). Fatal Accidents at Work by NACE Rev. 2 Activity. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hsw_n2_02/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Portal Legislativ. Lege nr. 319 din 14 iulie 2006. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/73772 (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Moraru, R.I.; Băbuţ, G.B.; Matei, I. Ghid Pentru Evaluarea Riscurilor Profesionale; Editura Focus: Petroşani, România, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moraru, R.I.; Băbuţ, G.B. Evaluarea şi Managementul Participativ al Riscurilor: Ghid Practic; Universitas: Petroşani, România, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ungureanu, E.; Mocanu, A.; Soare, A.; Mustatea, G. Health risk assessment of some heavy metals and trace elements in semi-sweet biscuits: A case study of Romanian market. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2022, 8, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Portal Legislativ. Hotărâre nr. 1.425 din 11 Octombrie 2006. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/76337 (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Băbuţ, G.B.; Moraru, R.I. Critical analysis and ways to improve the I.N.C.D.P.M. Bucharest risk assessment method for occupational accidents and diseases. Qual. Access Success 2013, 14, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Darabont, A.; Pece, Ş.; Dăscălescu, A. Managementul Securităţii şi Sănătăţii în Muncă (Vol. I şi II); AGIR: Bucureşti, România, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Darabont, A.; Nisipeanu, S.; Darabont, D. Auditul Securitatii si Sanatatii in Munca; AGIR: Bucureşti, România, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Glevitzky, I.; Sârb, A.; Popa, M. Study Regarding the Improvement of Bottling Process for Spring Waters, through the Implementation of the Occupational Health and Food Safety Requirements. Safety 2019, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Hierarchy of Controls, 10 April 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hierarchy-of-controls/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Identifying Hazard Control Options: The Hierarchy of Controls. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/Hierarchy_of_Controls_02.01.23_form_508_2.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).