Abstract

The rapid advancement of large language models like ChatGPT has significantly impacted natural language processing, expanding its applications across various fields, including healthcare. However, there remains a significant gap in understanding the consistency and reliability of ChatGPT’s performance across different medical domains. We conducted this systematic review according to an LLM-assisted PRISMA setup. The high-recall search term “ChatGPT” yielded 1101 articles from 2023 onwards. Through a dual-phase screening process, initially automated via ChatGPT and subsequently manually by human reviewers, 128 studies were included. The studies covered a range of medical specialties, focusing on diagnosis, disease management, and patient education. The assessment metrics varied, but most studies compared ChatGPT’s accuracy against evaluations by clinicians or reliable references. In several areas, ChatGPT demonstrated high accuracy, underscoring its effectiveness. However, performance varied, and some contexts revealed lower accuracy. The mixed outcomes across different medical domains emphasize the challenges and opportunities of integrating AI like ChatGPT into healthcare. The high accuracy in certain areas suggests that ChatGPT has substantial utility, yet the inconsistent performance across all applications indicates a need for ongoing evaluation and refinement. This review highlights ChatGPT’s potential to improve healthcare delivery alongside the necessity for continued research to ensure its reliability.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the emergence of large language models [1,2,3,4] has revolutionized the landscape of artificial intelligence (AI) for natural language processing (NLP) tasks among others [5]. These models, fueled by advancements in deep learning techniques and access to vast amounts of data, have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in understanding and generating human-like text [6]. Among these models, ChatGPT [1,2] has emerged as a prominent example, capturing widespread attention and adoption due to its ability to engage in coherent and contextually relevant conversations. ChatGPT was released to the public by OpenAI, an artificial intelligence research laboratory, in late 2022. It is based on a variant of the GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) model, specifically fine-tuned to be capable of generating human-like responses given a prompt or query. The release of ChatGPT marked a significant milestone in the development of conversational AI, providing a powerful tool for natural language understanding and generation [7]. Since its launch, ChatGPT has gained immense popularity, becoming one of the fastest-growing consumer internet apps to date. Within just two months, it attracted an estimated 100 million monthly users, showcasing its widespread adoption. Currently, over 2 million developers are actively utilizing the company’s API, including the majority of Fortune 500 companies, highlighting its significance across various industries.

In healthcare, ChatGPT offers a wide range of opportunities, including patient education, academic research, triage, diagnosis, decision-making, clinical documentation, and trial enrollment [8,9,10].

However, there are significant concerns surrounding its potential misuse, hallucination, data privacy, and authenticity of the information it generates [11]. Particularly given the delicate and highly regulated nature of healthcare, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the information it delivers is a primary concern among healthcare workers [12]. Inaccurate or misleading information in healthcare can have severe consequences, including misdiagnoses, improper treatments, and potential harm to patients’ well-being and safety.

Although prior research has explored ChatGPT’s potential applications and associated concerns in specific healthcare problems, there remains a notable gap in the literature concerning its actual performance in addressing broader healthcare-related inquiries. This gap underscores the need for further investigation to comprehensively evaluate ChatGPT’s effectiveness in this domain. Therefore, this study aimed to delve deeper into the literature to provide insights into the strengths, limitations, and future directions of leveraging ChatGPT in healthcare contexts.

By systematically synthesizing existing literature, this review addresses the following research questions:

- What is the overall accuracy and reliability of ChatGPT in providing health-related information across various medical fields?

- How does the context of inquiries impact the performance of ChatGPT?

- What is the perception of researchers about the use of ChatGPT in healthcare?

Ultimately, such a review holds the potential to inform stakeholders, including healthcare practitioners, researchers, policymakers, and technology developers, about the opportunities and challenges associated with integrating ChatGPT into the healthcare ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13]. The PRISMA framework provided a structured approach to ensure transparency, rigor, and reproducibility throughout the review process.

2.1. Search Strategy

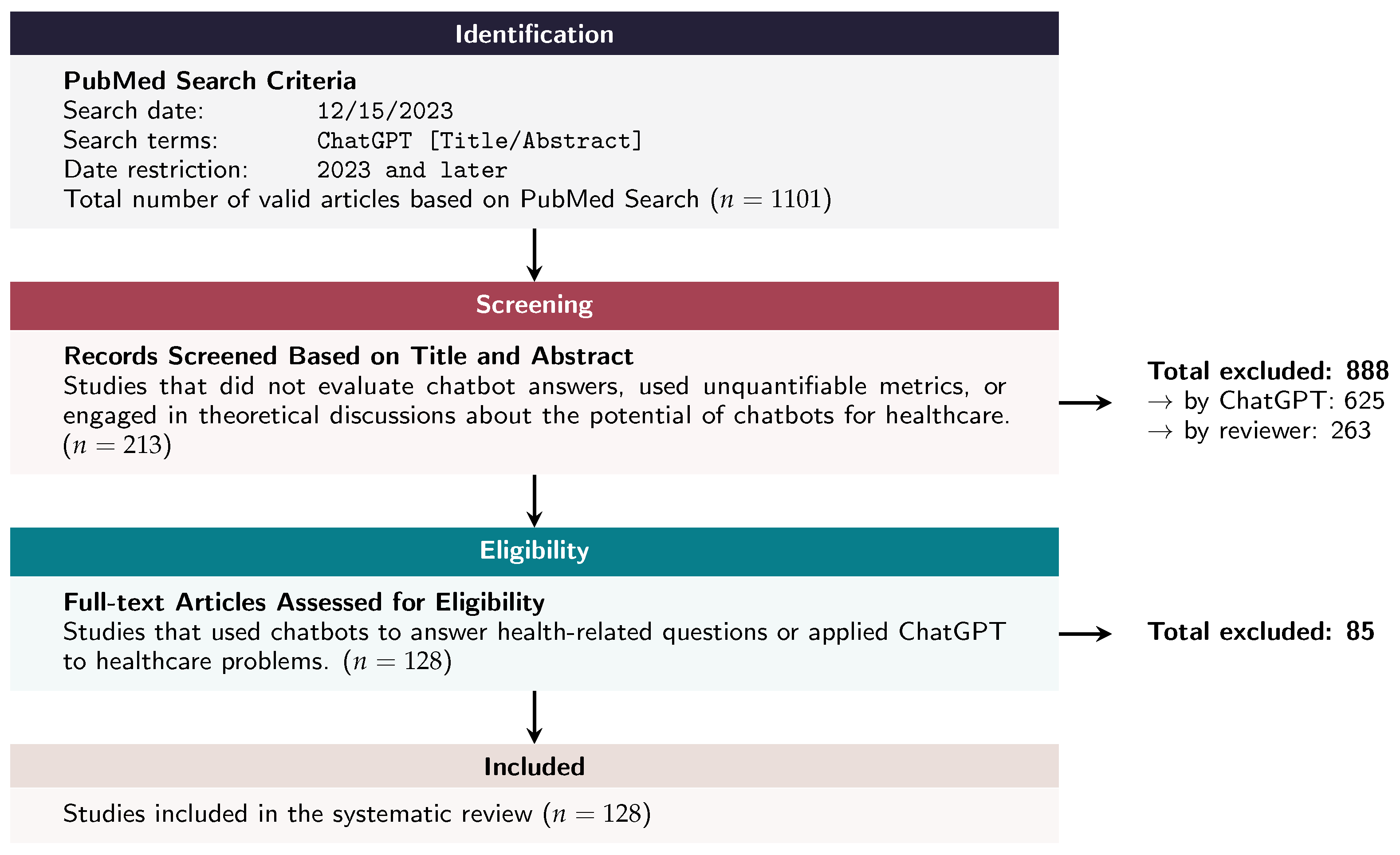

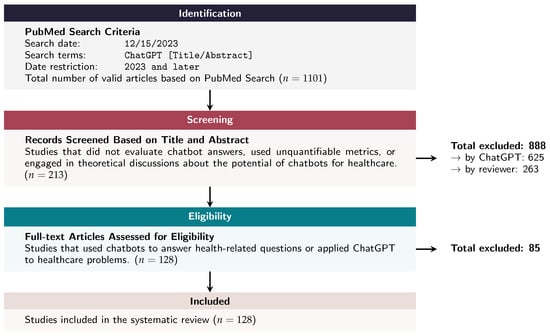

We utilized PubMed as the sole database for identifying relevant publications. Given the focus of our systematic review on the healthcare applications of ChatGPT, we prioritized a database that would most likely include studies of high relevance to our topic. We used only the term “ChatGPT” to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased search without applying any additional search restrictions. The search, conducted on 15 December 2023, targeted publications from 2023 onwards with “ChatGPT” in the title or abstract, resulting in 1940 articles. Out of these articles, we excluded 839 papers with missing abstracts, resulting in a total of 1101. These articles underwent a rigorous screening process based on their titles and abstracts, aimed at excluding studies that did not evaluate ChatGPT answers, used unquantifiable metrics, or engaged only in theoretical discussions about the potential of chatbots for healthcare. The PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the overall process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing the stages from initial search to final inclusion, starting with 1101 articles identified on PubMed and concluding with 128 studies included in the review after detailed screening and eligibility checks.

2.2. Study Selection and Screening

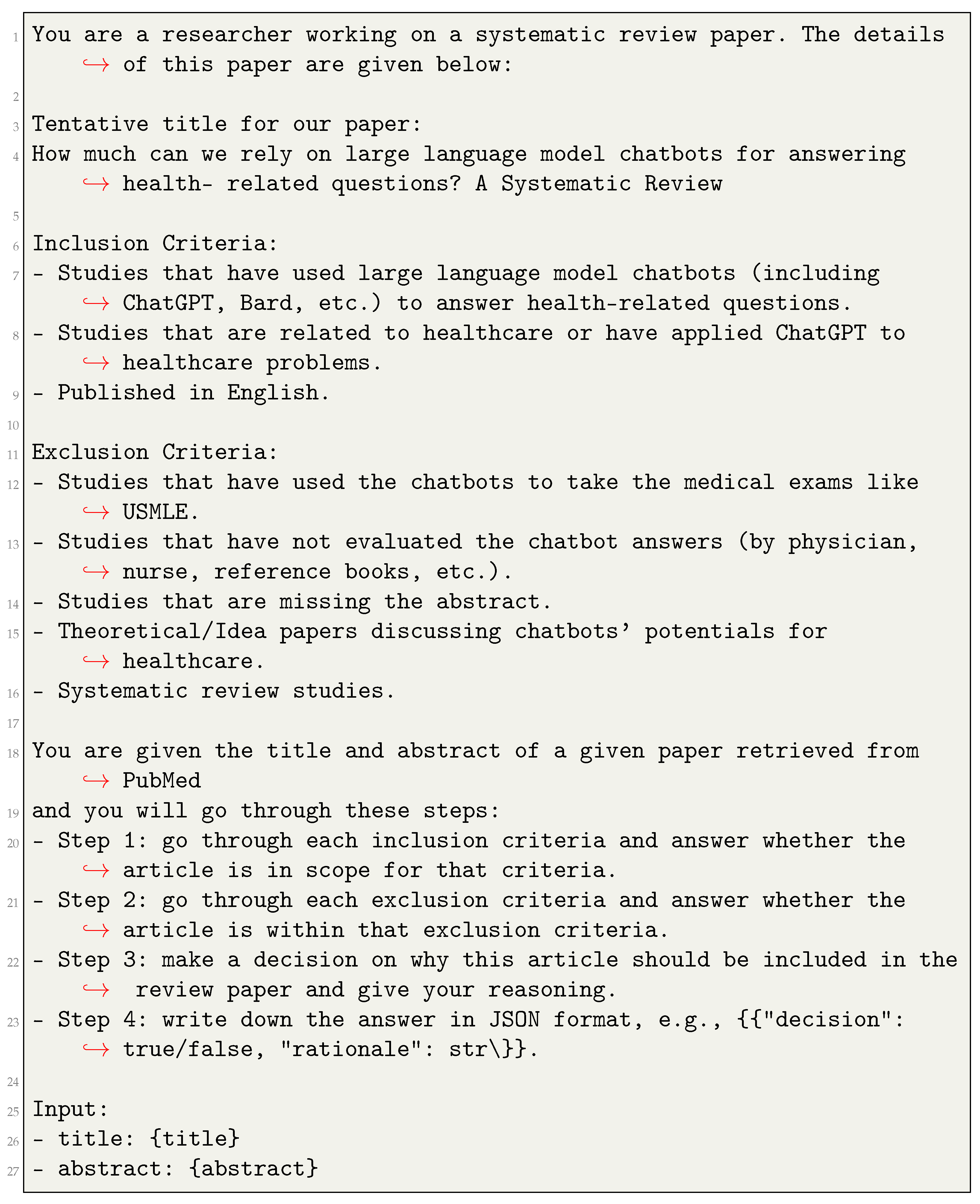

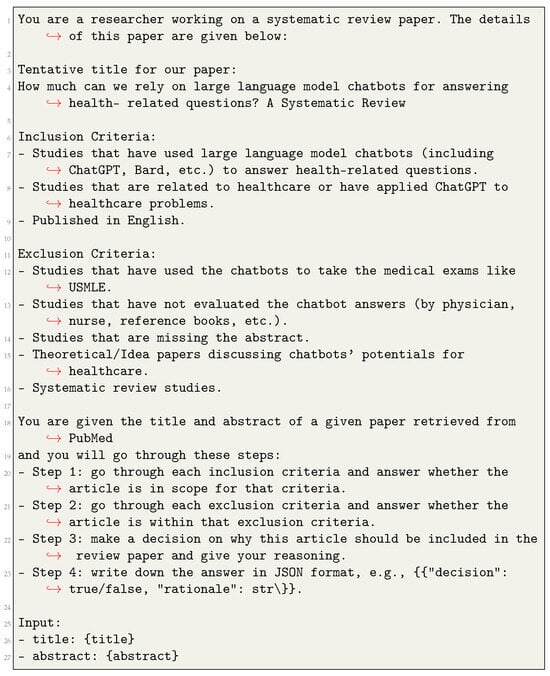

The study selection process began with an initial screening of titles and abstracts using an innovative methodology that leveraged ChatGPT. A specific prompt was engineered to guide ChatGPT in identifying studies relevant to healthcare applications of ChatGPT, ensuring comprehensive coverage without missing any relevant studies (Figure 2). This innovative method emphasized achieving 100% recall, ensuring comprehensive coverage without falsely excluding any relevant studies. To validate this, two reviewers independently assessed a random sample of 100 papers confirming the recall/sensitivity of ChatGPT’s selections and ensuring that all relevant studies were accurately identified. This automated screening (part-A) excluded 625 articles, leaving 476 for further evaluation.

Figure 2.

Prompt used to utilize ChatGPT for reviewing the titles and abstracts of studies retrieved from PubMed. This prompt was carefully engineered to maximize the inclusion of eligible studies, even those with a low likelihood of relevance, while minimizing the risk of false exclusion. It included detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with step-by-step instructions, to guide ChatGPT through the screening process, ensuring a thorough and consistent review of the studies.

Next, eight human reviewers conducted a secondary screening of the remaining articles (part-B). The articles were systematically divided among four pairs of reviewers, with each pair independently reviewing their assigned articles. This process involved a detailed assessment of titles and abstracts and, where necessary, a review of the full texts. Standardized assessment forms were employed to evaluate each study, and inter-rater reliability checks were performed to ensure consistency between reviewers. Discrepancies within each pair were resolved through discussion and consensus, providing a robust and unbiased selection process. This screening resulted in the exclusion of 263 articles, leaving 213 for further evaluation.

2.2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria ensured that only empirical and validated studies were included, maintaining the scientific rigor of the review. Refer to Table 1 for a detailed breakdown of the criteria.

Table 1.

A complete breakdown of inclusion and exclusion criteria used to screen papers related to the study research topic.

Out of the 213 articles assessed for eligibility, 85 were excluded, leaving 128 studies for inclusion in the systematic review. These studies were then analyzed to evaluate how ChatGPT was queried and assessed. The analysis included a thematic synthesis to identify common themes and patterns, as well as statistical methods to quantitatively summarize the findings where applicable. This comprehensive approach aimed to offer a nuanced understanding of the current landscape and potential future directions for ChatGPT’s use in healthcare.

2.2.2. Data Extraction

Data extraction was conducted independently by eight reviewers, with the included studies divided among them. Due to the large number of studies, data extraction was not performed in pairs but was instead individually assigned to each reviewer using a pre-designed data extraction form to ensure consistency and accuracy. The following data were extracted from each included study:

- Authors: The names of the authors of the study.

- Publication Year: The year in which the study was published.

- Medical Domain: The specific health/medical areas that the study inquires about or investigates.

- Type of Inquiries: The type of data used in the study to make the inquiry (e.g., questions, case scenarios/vignette).

- Number of Entries: The total number of inquiries asked from ChatGPT to evaluate its accuracy.

- Context of Inquiries: The context in which the questions were asked (e.g., diagnosis, education).

- Authors’ Perception: The authors’ perspective or perception about their evaluation results.

- ChatGPT Version: The version of ChatGPT that was used or evaluated in the study.

- Benchmark Reference: The benchmark or standard against which the ChatGPT-generated answers were compared (e.g., clinicians, guidelines).

- Evaluation Metrics: The metrics used to quantify the performance of ChatGPT in answering the inquiries (e.g., precision, recall).

Most studies used Likert-like scales to measure the accuracy of ChatGPT responses. However, the scales varied significantly—some used three-point, four-point, or five-point scales, among others, with starting points being either 0 or 1. Other studies utilized standard performance metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, and specificity. This variability influenced the significance of each Likert point, making direct comparisons across the studies challenging. To address this issue, we introduced a new measure that we named adjusted accuracy, which normalizes all evaluation metrics to a uniform 0–100% scale. This adjustment accounts for differences in scale range and starting points, enabling a meaningful synthesis of results across diverse evaluation strategies. Adjusted accuracy is defined in Equation (1).

where L is the reported average Likert value associated with accuracy by a given study, and and are the minimum and maximum possible scores on the Likert scale. For studies that used traditional accuracy metrics, we simply took the accuracy percentage reported. To avoid bias, we considered 0 as the minimum value during standardization, as some studies used scales starting from 1, which would not equate to 0% accuracy when standardized.

Due to the division of studies among reviewers, any discrepancies within a reviewer’s extracted data were addressed individually, and additional reviewers were consulted if needed.

2.3. Synthesis of Data

Given the significant heterogeneity in the data, we decided not to perform a meta-analysis. Some categories had sparse data—with only one or two entries—and pooling such data could lead to biased or misleading results. Instead, we opted for a boxplot-based approach to provide a transparent and descriptive synthesis of the data. This method allowed us to visualize central tendencies and variability across categories while respecting the dataset’s limitations. It effectively highlights trends without imposing assumptions that might not hold under these conditions. Additionally, boxplots serve as an excellent exploratory tool for analyzing heterogeneous data and identifying outliers or patterns.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

In the initial PubMed search, a total of 1101 articles met the inclusion criteria based on their titles. Following the screening process described in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1), 625 articles were excluded through automated screening using ChatGPT. These were identified as irrelevant, unquantifiable in their metrics, or solely theoretical in nature.

Subsequently, the remaining 476 articles underwent a secondary screening by human reviewers. This rigorous process, involving detailed assessments of titles, abstracts, and, where necessary, full texts, led to the exclusion of 263 additional articles. The most common reasons for exclusion at this stage were the lack of empirical data and failure to validate ChatGPT’s responses against a recognized standard. Thus, 213 articles were assessed for full-text eligibility, and 83 of these were further excluded based on the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Ultimately, 128 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the final systematic review.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 128 studies was included in this systematic review, covering a wide range of medical specialties and inquiry types. The studies were published between 2023 and 2024 and focused on evaluating ChatGPT’s performance in healthcare-related tasks. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the included studies, detailing the year, medical domain, type of inquiries, number of entries, context of inquiries, authors’ perception of ChatGPT’s performance, version of ChatGPT used, and the comparison benchmarks.

Table 2.

A summary of the 128 studies included in the systematic review. It shows the authors, publication year, medical field, type of inquiries addressed by ChatGPT, the number of entries analyzed, context of the questions, authors’ perception of ChatGPT’s performance, version of ChatGPT used, and the comparison benchmark for the answers provided.

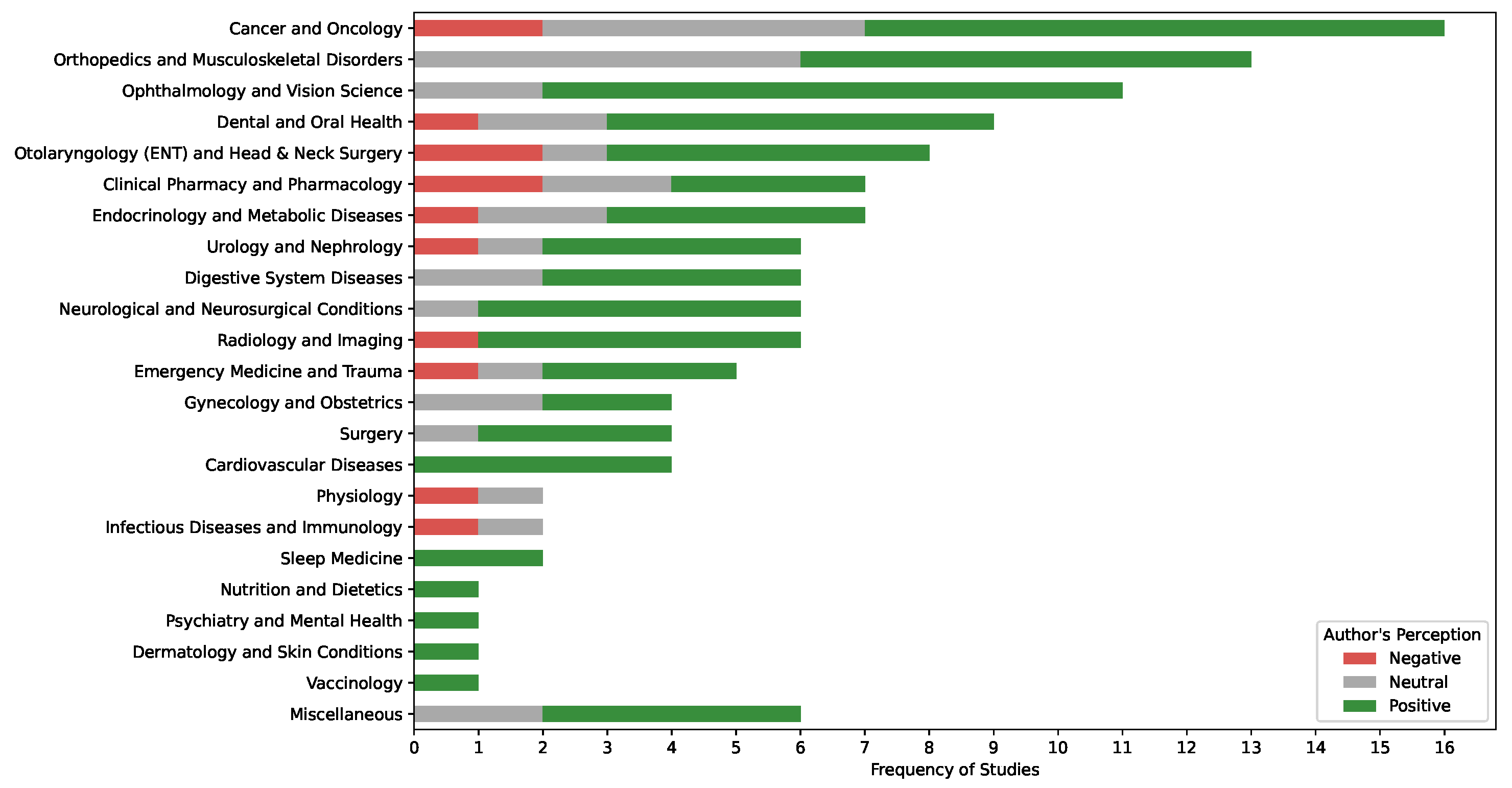

3.3. Thematic Synthesis and Authors’ Perceptions

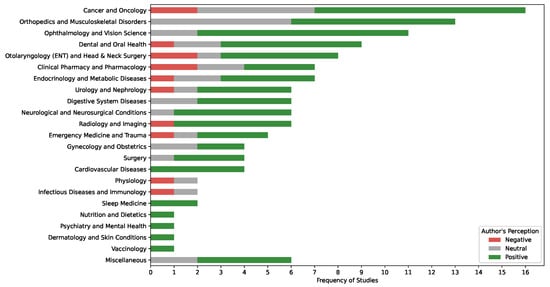

The thematic synthesis of the studies shows that the highest frequency of research was conducted in the fields of cancer and oncology [14,26,47], orthopedics and musculoskeletal disorders [31,113], and ophthalmology and vision science [75,87,118,121] (Figure 3). In these fields, the majority of authors had a positive perception of ChatGPT’s performance. Other medical fields, such as nutrition and dietetics [38], psychiatry and mental health [34], dermatology and skin conditions [80], and vaccinology [110], were studied less frequently, with all reported studies indicating positive perceptions.

Figure 3.

A stacked bar chart showing the frequency of studies across medical fields and authors’ perceptions of ChatGPT’s performance.

In contrast, fields such as otolaryngology (ENT) and head and neck surgery [15,21,27,30,43,56,77,85], clinical pharmacy and pharmacology [44,45,48,65,98,109], and emergency medicine and trauma [20,40,81,140] displayed a more varied range of author perceptions, with studies reporting positive, neutral, and negative outcomes (Figure 3). Overall, the data suggest a general trend of positive author perceptions across a wide range of medical specialties, though the extent of research and perception varies by field.

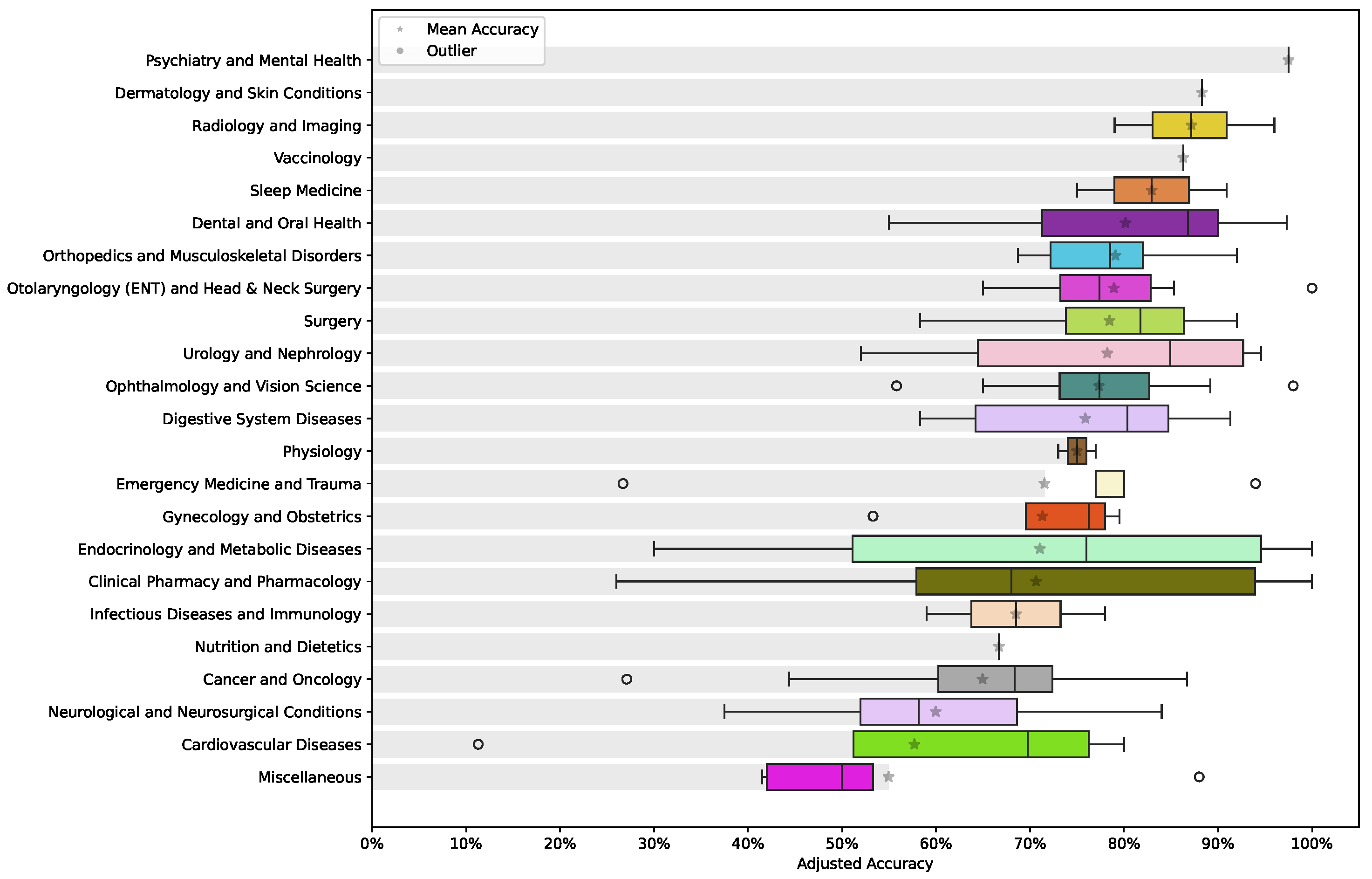

3.4. Performance Across Medical Domains

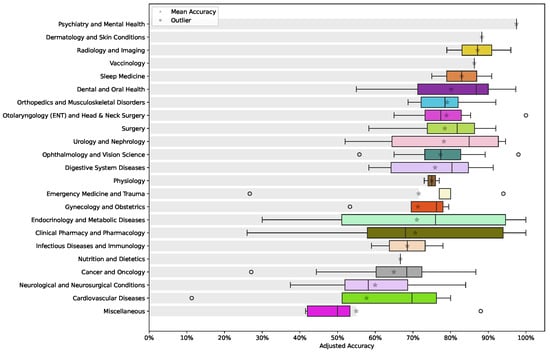

ChatGPT’s performance across different medical domains was evaluated using the adjusted accuracy metric (Equation (1)). The overall mean accuracy of ChatGPT was 73.4%, with a 95% confidence interval ranging between 70.3% and 76.5%. The results, depicted in Figure 4, reveal a wide variation in performance depending on the medical specialty. Psychiatry and mental health [34], along with dermatology and skin conditions [80], emerge as the areas where ChatGPT exhibits the highest accuracy, with relatively consistent results and minimal outliers.

Figure 4.

A boxplot showing the adjusted accuracy of ChatGPT responses across various medical domains. In addition to the median, the mean is highlighted using a star for each medical domain box.

In contrast, specialties such as cardiovascular diseases [63,68,86,101], neurological and neurosurgical conditions [59,89,102,106], and cancer and oncology [18,33,95,115,139] present more variability in accuracy. These fields display a broader range of performance, with several outliers indicating instances where ChatGPT’s responses are less reliable. This suggests that, while ChatGPT can perform effectively in some medical domains, its accuracy is less consistent in more complex or specialized fields, reflecting the challenges in achieving uniform performance across diverse medical topics.

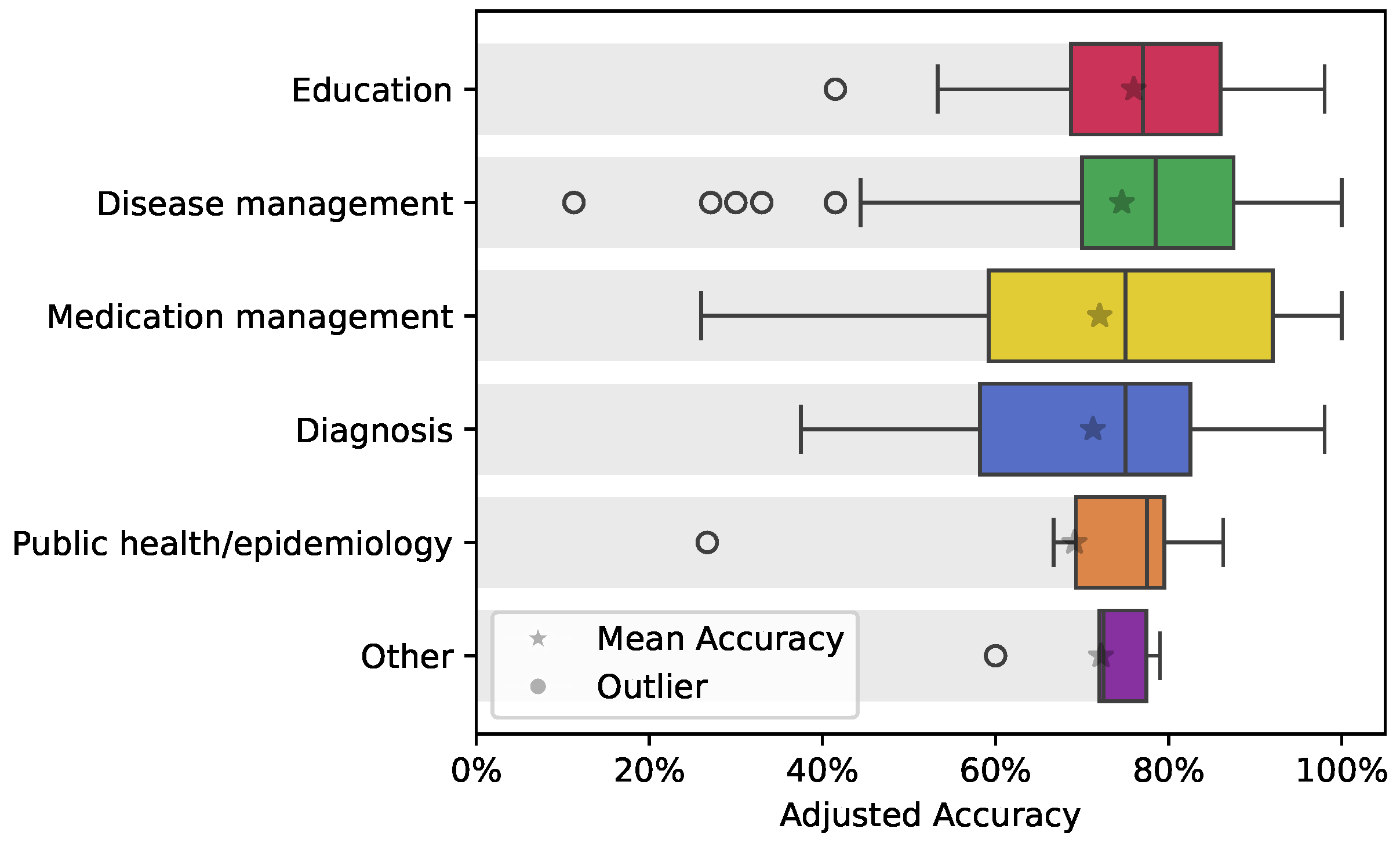

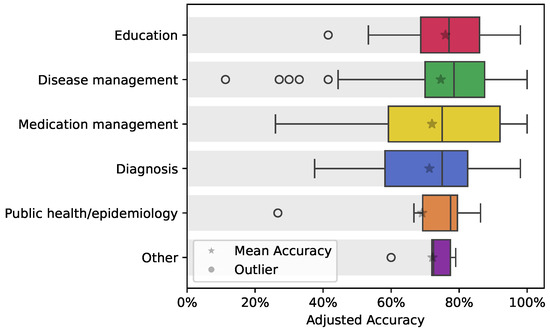

3.5. Performance Across Inquiry Contexts

ChatGPT’s performance was further analyzed across different contexts of inquiries, such as diagnosis, disease management, education, and medication management. The boxplot in Figure 5 illustrates the adjusted accuracy of ChatGPT responses across these contexts. Educational inquiries show relatively higher accuracy compared to more complex contexts like disease management and diagnosis. Specific outliers are observed in contexts such as diagnosis and public health/epidemiology, indicating areas where ChatGPT’s performance is less consistent. This variability highlights the need for the continued refinement of large language models to address the challenges in more intricate medical fields.

Figure 5.

Adjusted accuracy of ChatGPT responses across various inquiry contexts, with the mean highlighted using a star for each context box.

3.6. Performance Across ChatGPT Versions

The analysis of ChatGPT versions revealed a relatively balanced representation, with version 3.5 being utilized in 40.63% of the cases, while version 4.0 was employed in 38.28% of the studies, and 21.09% of the cases did not report the version used. To determine whether there was a significant difference in performance between these versions, we conducted a Mann–Whitney U test on the evaluated accuracy scores. The test yielded a p-value of 0.96, indicating no statistically significant difference in performance between the two versions overall.

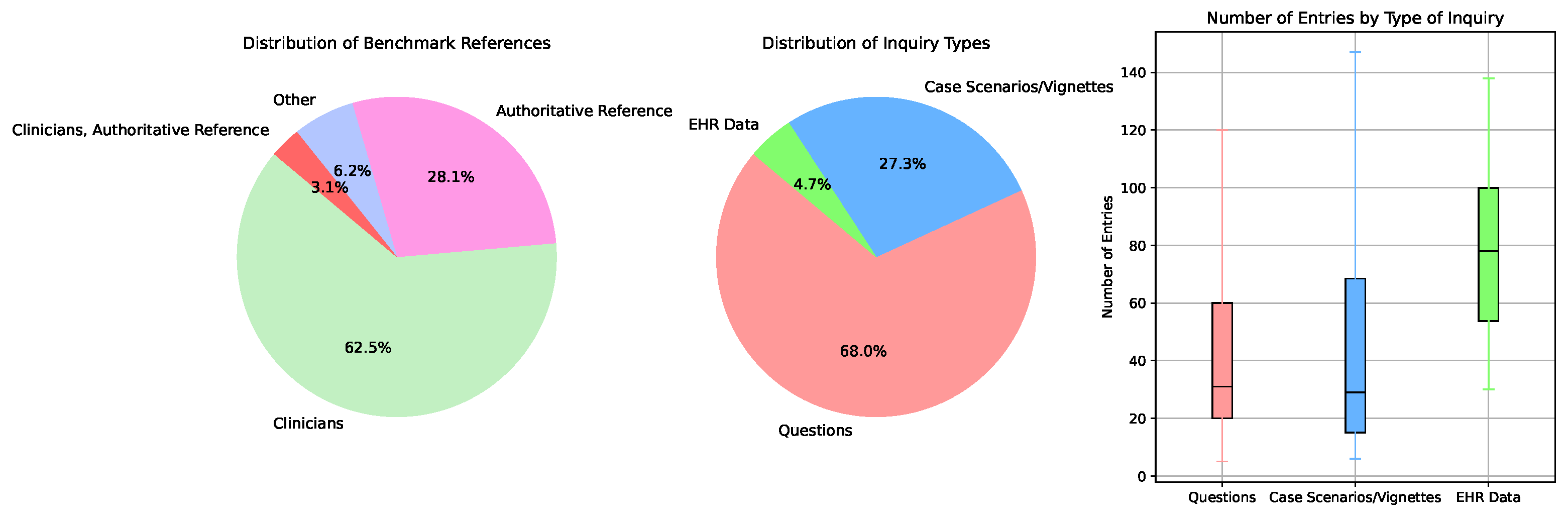

3.7. Benchmark References and Inquiry Types

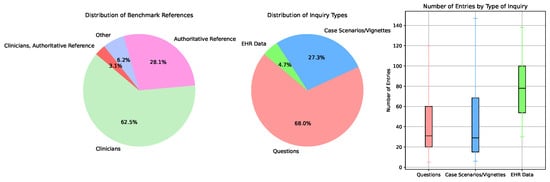

The studies used various benchmarks to evaluate ChatGPT’s performance, with clinicians serving as the primary reference in 62.5% of cases (Figure 6). Authoritative references were used in 28.1% of the studies, while other references accounted for 6.2%. The types of inquiries posed to ChatGPT predominantly consisted of direct questions (68.0%), followed by case scenarios/vignettes (27.3%), and electronic health record (EHR) data (4.7%).

Figure 6.

Distribution of benchmark references and inquiry types used in performance evaluation of ChatGPT. Note that outliers in the boxplot have been hidden to better show the distribution differences.

The boxplot on the right side of (Figure 6) provides further insight into the distribution of the number of entries by each type of inquiry. This plot reveals significant variability across different inquiry types. Questions exhibit the widest range, with most studies containing between 50 and 100 entries. Case scenarios/vignettes display a slightly narrower range, with the majority of studies containing between 40 and 80 entries. The number of entries for EHR data inquiries is generally more consistent, clustering between 60 and 100 entries, indicating less variability in the volume of these inquiries.

The larger number of entries associated with direct questions suggests a broader application of this inquiry type, while the more focused range for case scenarios/vignettes and EHR data may reflect the specialized and often more detailed nature of these inquiries. These distributions highlight the diverse methods employed to assess ChatGPT’s effectiveness and its practical application in healthcare.

4. Discussion

This systematic review included a total of 128 studies that evaluated the performance of ChatGPT in various healthcare-related tasks across various medical domains. Through a detailed analysis of these studies, we aimed to assess the current effectiveness of ChatGPT in healthcare and identify areas that require further improvement.

One of the most notable observations is the generally positive perceptions among authors across a wide range of medical specialties. This suggests a growing confidence in the utility of ChatGPT for specific healthcare-related tasks. However, the variability in perceptions across different fields, particularly in more complex specialties such as diagnosis, underscores the need for cautious optimism. These differences highlight that, while ChatGPT has shown promise, its performance is not uniformly reliable across all medical domains. The performance analysis of ChatGPT further supports this nuanced view. The overall mean accuracy of 73.4% is encouraging, yet the variability in accuracy across specialties points to significant room for improvement. For instance, the high accuracy observed in psychiatry and dermatology contrasts sharply with the more variable results in endocrinology and metabolic diseases, and clinical pharmacy and pharmacology. This disparity likely reflects the inherent complexity and specialized knowledge required in different medical fields, indicating that ChatGPT may be better suited for certain types of inquiries than others.

The context in which inquiries are made also plays a crucial role in determining ChatGPT’s effectiveness. Educational inquiries, which tend to be more straightforward and less nuanced, showed higher accuracy compared to more complex tasks like diagnosis and disease management. This finding suggests that, while ChatGPT can be a useful tool for education and patient engagement, its application in more critical and complex medical decisions should be approached with caution. The presence of outliers in contexts such as diagnosis further emphasizes the need for ongoing refinement of the model to enhance its consistency and reliability.

Interestingly, the analysis of two versions of ChatGPT (3.5 vs. 4.0) did not reveal any significant differences in performance overall. In contrast to our findings, individual studies have reported significant improvements with GPT-4.0 over version 3.5 in specific domains [16,75,133]. For example, in ophthalmology, Jiao et al. [133] reported that GPT-4.0 significantly outperformed GPT-3.5, with an accuracy rate of 75% compared to 46% for GPT-3.5 in answering multiple-choice ophthalmic case challenges [133]. This suggests that the improvements observed in GPT-4.0 might be context-dependent, indicating that its enhanced performance may be more pronounced in certain specialized applications than in others.

The diversity in the performance metrics employed to evaluate the accuracy of ChatGPT’s responses poses a significant challenge in drawing consistent and comparable conclusions across the studies. The wide range of metrics used, from basic accuracy to more detailed measures, makes it difficult to assess the model’s performance uniformly. This lack of standardization complicates the synthesis of findings and limits the ability to benchmark ChatGPT’s reliably. Moreover, only six studies (Supplementary Table S1) reported specific metrics such as precision, recall, and specificity, which are crucial for a detailed understanding of the model’s performance. These metrics provide deeper insights into the model’s ability to correctly identify relevant responses (precision), capture all relevant instances (recall), and accurately distinguish between different classes or conditions (specificity). The absence of these critical metrics in the majority of studies highlights a significant gap in the current evaluation framework, suggesting that the reported performance may not fully capture the nuances of ChatGPT’s capabilities. To advance the field, future research should prioritize the use of comprehensive and standardized performance metrics to enable more accurate and meaningful comparisons.

4.1. Study Limitations

Despite these promising applications, our review identified several challenges and limitations that must be addressed while discussing our results. First, the search strategy was limited to a single database, PubMed, due to the focus on studies utilizing ChatGPT in healthcare settings. Although this approach ensured the inclusion of studies relevant to the objective, it may have excluded pertinent research published in non-PubMed-indexed journals or other databases. While acknowledging that including additional databases may yield a broader range of results, we believe our focus on PubMed allowed us to maintain scientific rigor while effectively addressing our research questions.

In addition, an innovative approach was adopted to automate the title and abstract screening process using ChatGPT, with a prompt specifically engineered to ensure the inclusion of all eligible studies. Although this method was validated with a sample of 100 studies, achieving 100% recall, there remains a slight possibility of error. Furthermore, the data extraction process encountered several challenges. Given the large number of included studies, data extraction was not performed in pairs. Nevertheless, efforts were made to ensure accuracy by openly communicating any uncertainties during the extraction process and reaching a consensus when needed. Additionally, the heterogeneity of the included studies posed significant challenges in data synthesis. The studies varied widely in the medical fields they covered and in the performance metrics used to evaluate ChatGPT. As a result, this variability required the development of an adjusted accuracy metric to effectively synthesize the data. While this approach was necessary to manage these differences, it may not fully capture the specific nuances of each study’s findings, thereby limiting the interpretability and comparability of the synthesized results.

Another important consideration is the risk of bias among the included studies, which stems from the variability in how ChatGPT’s performance was assessed. Each study used a different set of inquiries, and performance evaluations were often based on the subjective opinions of judges. Although many studies employed clinicians or authoritative references for these evaluations, the inherent subjectivity of human judgment introduces a risk of bias that could affect the validity of the findings.

Finally, the generalizability of the findings is limited by the specific contexts in which the included studies were conducted. The results may not be fully applicable to other populations, settings, or contexts, particularly given the diversity of medical fields and evaluation methods represented in the reviewed studies. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extending these findings to broader applications of ChatGPT in healthcare.

4.2. Future Directions

The findings of this systematic review underscore several key areas for future research and development in the application of ChatGPT in healthcare. Firstly, there is a clear need for further exploration of the model’s performance across a broader range of medical specialties, particularly those that involve complex diagnostic and treatment decisions. Future studies should aim to evaluate ChatGPT’s capabilities in more nuanced and specialized contexts, where the accuracy and reliability of the model are critical.

Secondly, a crucial area for future research is the standardization of performance metrics. The review highlighted a significant lack of uniformity in the evaluation frameworks across the studies, underscoring the necessity for a consistent set of metrics that can accurately assess ChatGPT’s capabilities. Metrics such as precision, recall, and specificity, among others, should be universally adopted to provide a comprehensive understanding of the model’s performance. Establishing standardized benchmarks will not only facilitate more meaningful comparisons across different studies but also enable a more precise and reliable assessment of the model’s strengths and weaknesses, ultimately advancing the field of AI in healthcare.

Additionally, the potential of GPT-4.0 and future iterations of the model warrants further investigation, particularly in specialized applications where preliminary findings suggest significant improvements over earlier versions. Research should continue to explore the context-dependent nature of these improvements to better understand where and how new versions of ChatGPT can be most effectively utilized in healthcare.

Finally, large language models like ChatGPT are highly sensitive to the prompts they receive, which can significantly influence their output. This sensitivity necessitates further research into prompt engineering—a process that involves crafting prompts in ways that optimize the model’s performance. Future work should focus on developing and utilizing standardized methodologies, such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), to construct better prompts and improve accuracy. By enhancing the way prompts are designed and interpreted, researchers can help ensure that ChatGPT provides more reliable and contextually appropriate responses, thereby increasing its utility in clinical settings.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the potential and limitations of ChatGPT in healthcare, based on the analysis of 128 studies across various medical domains. The findings indicate a generally positive perception of ChatGPT’s utility, particularly in simpler tasks such as educational inquiries. However, significant variability in performance was observed across different specialties, with higher accuracy in fields like psychiatry and dermatology, and more inconsistent results in complex domains such as endocrinology, clinical pharmacy, and pharmacology. This suggests that, while ChatGPT shows promise, its accuracy is not uniform across all medical applications, necessitating cautious implementation in critical healthcare decisions. The comparison between ChatGPT versions 3.5 and 4.0 revealed that, while there may be domain-specific improvements in ChatGPT 4.0, overall performance differences were not statistically significant. This indicates that advancements in AI models might be context-dependent, further emphasizing the need for tailored application and continuous refinement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/informatics12010009/s1, Supplementary Table S1: The 6 out of the 128 studies which reported specific measures such as precision, recall, and specificity.

Author Contributions

M.B. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. I.E.T. contributed to the design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. K.A. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. M.A. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript; data acquisition and interpretation of the data; and critically revised the manuscript. O.B.O. contributed to the design, data acquisition, and analysis of the data and critically revised the manuscript. H.T. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript; interpretation of the data; and critically revised the manuscript. N.A. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript; interpretation of the data; and critically revised the manuscript. S.A.B. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript; data acquisition and interpretation of the data; and critically revised the manuscript. G.J.S. provided funding and critically revised the manuscript. B.M.D. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the manuscript; managed and led the research project; was involved in data acquisition and interpretation of the data and drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not collect informed consent because it was determined to fall under Exemption 4 of the NIH Human Subjects Research Exemptions.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L.; Chiriatti, M. GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds Mach. 2020, 30, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Toubal, I.E.; Avinash, A.; Alldrin, N.G.; Dlabal, J.; Zhou, W.; Luo, E.; Stretcu, O.; Xiong, H.; Lu, C.T.; Zhou, H.; et al. Modeling Collaborator: Enabling Subjective Vision Classification with Minimal Human Effort via LLM Tool-Use. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 17553–17563. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Introducing ChatGPT. 2020. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Garg, R.K.; Urs, V.L.; Agarwal, A.A.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Paliwal, V.; Kar, S.K. Exploring the role of ChatGPT in patient care (diagnosis and treatment) and medical research: A systematic review. Health Promot. Perspect. 2023, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dada, A.; Puladi, B.; Kleesiek, J.; Egger, J. ChatGPT in healthcare: A taxonomy and systematic review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 245, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fui-Hoon Nah, F.; Zheng, R.; Cai, J.; Siau, K.; Chen, L. Generative AI and ChatGPT: Applications, challenges, and AI-human collaboration. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2023, 25, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsah, M.H.; Aljamaan, F.; Malki, K.H.; Alhasan, K.; Altamimi, I.; Aljarbou, R.; Bazuhair, F.; Alsubaihin, A.; Abdulmajeed, N.; Alshahrani, F.S.; et al. ChatGPT and the Future of Digital Health: A Study on Healthcare Workers’ Perceptions and Expectations. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.H.; Samaan, J.S.; Ng, W.H.; Ting, P.S.; Trivedi, H.; Vipani, A.; Ayoub, W.; Yang, J.D.; Liran, O.; Spiegel, B.; et al. Assessing the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions regarding cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moise, A.; Centomo-Bozzo, A.; Orishchak, O.; Alnoury, M.K.; Daniel, S.J. Can ChatGPT guide parents on tympanostomy tube insertion? Children 2023, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, A.; Trachsel, T.; Weiger, R.; Eggmann, F. ChatGPT’s performance in dentistry and allergyimmunology assessments: A comparative study. Swiss Dent. J. SSO-Sci. Clin. Top. 2024, 134, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, C. Analyzing the performance of ChatGPT about osteoporosis. Cureus 2023, 15, e45890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geetha, S.D.; Khan, A.; Khan, A.; Kannadath, B.S.; Vitkovski, T. Evaluation of ChatGPT pathology knowledge using board-style questions. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 161, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlas, T.; Altinova, A.E.; Akturk, M.; Toruner, F.B. Credibility of ChatGPT in the assessment of obesity in type 2 diabetes according to the guidelines. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, R.K.; Uddin, H.; Gan, A.Z.; Yew, Y.Y.; González, P.A. ChatGPT’s performance before and after teaching in mass casualty incident triage. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Georgescu, B.M.; Hans, S.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M. ChatGPT performance in laryngology and head and neck surgery: A clinical case-series. Eur. Arch.-Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2024, 281, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barash, Y.; Klang, E.; Konen, E.; Sorin, V. ChatGPT-4 assistance in optimizing emergency department radiology referrals and imaging selection. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, A.; Díaz-Flores García, V.; Algar, J.; Gómez Sánchez, M.; Llorente de Pedro, M.; Freire, Y. Unveiling the ChatGPT phenomenon: Evaluating the consistency and accuracy of endodontic question answers. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mago, J.; Sharma, M. The potential usefulness of ChatGPT in oral and maxillofacial radiology. Cureus 2023, 15, e42133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antaki, F.; Touma, S.; Milad, D.; El-Khoury, J.; Duval, R. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in ophthalmology: An analysis of its successes and shortcomings. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 3, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, B. Capacity of ChatGPT to identify guideline-based treatments for advanced solid tumors. Cureus 2023, 15, e37938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellinger, J.R.; De La Chapa, J.S.; Kwak, M.W.; Ramos, G.A.; Morrison, D.; Kesser, B.W. BPPV information on google versus AI (ChatGPT). Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2024, 170, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z. Evaluation of ChatGPT’s capabilities in medical report generation. Cureus 2023, 15, e37589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogasch, J.M.; Metzger, G.; Preisler, M.; Galler, M.; Thiele, F.; Brenner, W.; Feldhaus, F.; Wetz, C.; Amthauer, H.; Furth, C.; et al. ChatGPT: Can you prepare my patients for [18F] FDG PET/CT and explain my reports? J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 1876–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, C.R.; Smith, H.; Huppertz, T.; Bahr-Hamm, K.; Matthias, C.; Blaikie, A.; Kelsey, T.; Kuhn, S.; Eckrich, J. ChatGPT versus consultants: Blinded evaluation on answering otorhinolaryngology case–based questions. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e49183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duey, A.H.; Nietsch, K.S.; Zaidat, B.; Ren, R.; Ndjonko, L.C.M.; Shrestha, N.; Rajjoub, R.; Ahmed, W.; Hoang, T.; Saturno, M.P.; et al. Thromboembolic prophylaxis in spine surgery: An analysis of ChatGPT recommendations. Spine J. 2023, 23, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, I.; Al-Abdallat, H.; Alnajjar, Z.; Ismail, L.; Abukhashabeh, R.; Bitar, L.; Shanap, M.A. Using ChatGPT to predict cancer predisposition genes: A promising tool for pediatric oncologists. Cureus 2023, 15, e47594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, K.; Fritz, C.; Rajasekaran, K. Answering head and neck cancer questions: An assessment of ChatGPT responses. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.F.; Amanullah, S.; Mathew, M.; Surapaneni, K.M. Appraising the performance of ChatGPT in psychiatry using 100 clinical case vignettes. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 89, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, H.J.; Chien, T.W.; Wang, W.C.; Chou, W.; Chow, J.C. Assessing ChatGPT’s capacity for clinical decision support in pediatrics: A comparative study with pediatricians using KIDMAP of Rasch analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e34068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, R.; Alan, B.M. Utilizing ChatGPT-4 for providing information on periodontal disease to patients: A DISCERN quality analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e46213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, H.; Dash, I.; Mondal, S.; Behera, J.K. ChatGPT in answering queries related to lifestyle-related diseases and disorders. Cureus 2023, 15, e48296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D.; van Eijnatten, E.; Camps, G. Comparison of answers between ChatGPT and human dieticians to common nutrition questions. J. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 2023, 5548684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köroğlu, E.Y.; Fakı, S.; Beştepe, N.; Tam, A.A.; Seyrek, N.Ç.; Topaloglu, O.; Ersoy, R.; Cakir, B. A novel approach: Evaluating ChatGPT’s utility for the management of thyroid nodules. Cureus 2023, 15, e47576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M.; Ballout, A.A.; Zayek, R.A.; Ayoub, N.F. Mind+ Machine: ChatGPT as a Basic Clinical Decisions Support Tool. Cureus 2023, 15, e43690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosawa, T.; Harada, Y.; Yokose, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Kawamura, R.; Shimizu, T. Diagnostic accuracy of differential-diagnosis lists generated by generative pretrained transformer 3 chatbot for clinical vignettes with common chief complaints: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakir, H.; Caglar, U.; Yildiz, O.; Meric, A.; Ayranci, A.; Ozgor, F. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions related to urolithiasis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2024, 56, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R.W.; Qureshi, U.; Petersen, G.; Lee, S.C. Diagnostic and management applications of ChatGPT in structured otolaryngology clinical scenarios. OTO Open 2023, 7, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dujaili, Z.; Omari, S.; Pillai, J.; Al Faraj, A. Assessing the accuracy and consistency of ChatGPT in clinical pharmacy management: A preliminary analysis with clinical pharmacy experts worldwide. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 1590–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.Y.; Hsu, K.C.; Hou, S.Y.; Wu, C.L.; Hsieh, Y.W.; Cheng, Y.D. Examining real-world medication consultations and drug-herb interactions: ChatGPT performance evaluation. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e48433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarre, J.; Feldt, R.; Keeling, L.E.; Dadoo, S.; Zsidai, B.; Hughes, J.D.; Samuelsson, K.; Musahl, V. Exploring the potential of ChatGPT as a supplementary tool for providing orthopaedic information. Knee Surg. Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 5190–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, J.M.; Ryu, H.S.; Kim, J.S.; Cheong, J.Y.; Baek, S.J.; Kwak, J.M.; Kim, J. Conversational artificial intelligence (chatGPT™) in the management of complex colorectal cancer patients: Early experience. ANZ J. Surg. 2024, 94, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosan, D.; Padua, P.; Khan, R.; Khan, H.; Verzosa, C.; Wu, Y. Effectiveness of ChatGPT in clinical pharmacy and the role of artificial intelligence in medication therapy management. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2024, 64, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sütcüoğlu, B.M.; Güler, M. Appropriateness of premature ovarian insufficiency recommendations provided by ChatGPT. Menopause 2023, 30, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocci, A.; Pezzoli, M.; Lo Re, M.; Russo, G.I.; Asmundo, M.G.; Fode, M.; Cacciamani, G.; Cimino, S.; Minervini, A.; Durukan, E. Quality of information and appropriateness of ChatGPT outputs for urology patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024, 27, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, M.W.; Ertl-Wagner, B.B. Accuracy of information and references using ChatGPT-3 for retrieval of clinical radiological information. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2024, 75, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, M.; Koa, J.; Boufadel, P.; Singh, J.; Fares, M.Y.; Abboud, J.A. Breaking barriers: Can ChatGPT compete with a shoulder and elbow specialist in diagnosis and management? JSES Int. 2023, 7, 2534–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Gao, K.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, W.; Guo, C. Potential and limitations of ChatGPT 3.5 and 4.0 as a source of COVID-19 information: Comprehensive comparative analysis of generative and authoritative information. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e49771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbay, İ.; Berikol, G.B.; Özturan, İ.U. Performance of emergency triage prediction of an open access natural language processing based chatbot application (ChatGPT): A preliminary, scenario-based cross-sectional study. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.I.; Yu, C.Y.; Woo, A. The impacts of visual street environments on obesity: The mediating role of walking behaviors. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 109, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høj, S.; Thomsen, S.F.; Meteran, H.; Sigsgaard, T.; Meteran, H. Artificial intelligence and allergic rhinitis: Does ChatGPT increase or impair the knowledge? J. Public Health 2024, 46, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, S.; Saban, M. Evaluating the reliability of ChatGPT as a tool for imaging test referral: A comparative study with a clinical decision support system. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 2826–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, J.; Cai, X.; Wu, D.; Yin, C. A descriptive study based on the comparison of ChatGPT and evidence-based neurosurgeons. Iscience 2023, 26, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Begley, S.L.; Chen, A.; Rob, M.; Pelcher, I.; Ward, M.; Schulder, M. Exploring the intersection of artificial intelligence and neurosurgery: Let us be cautious with ChatGPT. Neurosurgery 2022, 93, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Logan, N.S.; Davies, L.N.; Sheppard, A.L.; Wolffsohn, J.S. Assessing the utility of ChatGPT as an artificial intelligence-based large language model for information to answer questions on myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2023, 43, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Ruan, S.; Li, M.; Yin, C. Are different versions of ChatGPT’s ability comparable to the clinical diagnosis presented in case reports? A descriptive study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 3825–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.L.; Ghani, S.; Kuemmerli, C.; Nebiker, C.A.; Müller, B.P.; Raptis, D.A.; Staubli, S.M. Reliability of medical information provided by ChatGPT: Assessment against clinical guidelines and patient information quality instrument. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.; Sadiq, T. The use of AI in diagnosing diseases and providing management plans: A consultation on cardiovascular disorders with ChatGPT. Cureus 2023, 15, e43106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.; Shafik, L.; Alanbuki, A.; Larner, T. The utility of the ChatGPT artificial intelligence tool for patient education and enquiry in robotic radical prostatectomy. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 2717–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Estau, D.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Qin, J.; Li, Z. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in clinical pharmacy: A comparative study of ChatGPT and clinical pharmacists. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Y.; Alessandri Bonetti, M.; De Lorenzi, F.; Gimbel, M.L.; Nguyen, V.T.; Egro, F.M. Consulting the digital doctor: Google versus ChatGPT as sources of information on breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma and breast implant illness. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanvijay, A.K.D.; Pinjar, M.J.; Dhokane, N.; Sorte, S.R.; Kumari, A.; Mondal, H. Performance of large language models (ChatGPT, Bing Search, and Google Bard) in solving case vignettes in physiology. Cureus 2023, 15, e42972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusunose, K.; Kashima, S.; Sata, M. Evaluation of the accuracy of ChatGPT in answering clinical questions on the Japanese society of hypertension guidelines. Circ. J. 2023, 87, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krusche, M.; Callhoff, J.; Knitza, J.; Ruffer, N. Diagnostic accuracy of a large language model in rheumatology: Comparison of physician and ChatGPT-4. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babayiğit, O.; Eroglu, Z.T.; Sen, D.O.; Yarkac, F.U. Potential use of ChatGPT for Patient Information in Periodontology: A descriptive pilot study. Cureus 2023, 15, e48518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cankurtaran, R.E.; Polat, Y.H.; Aydemir, N.G.; Umay, E.; Yurekli, O.T. Reliability and usefulness of ChatGPT for inflammatory bowel diseases: An analysis for patients and healthcare professionals. Cureus 2023, 15, e46736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri-Bonetti, M.; Liu, H.Y.; Palmesano, M.; Nguyen, V.T.; Egro, F.M. Online patient education in body contouring: A comparison between Google and ChatGPT. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2023, 87, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janopaul-Naylor, J.R.; Koo, A.; Qian, D.C.; McCall, N.S.; Liu, Y.; Patel, S.A. Physician assessment of ChatGPT and bing answers to American cancer society’s questions to ask about your cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 47, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ashwal, F.Y.; Zawiah, M.; Gharaibeh, L.; Abu-Farha, R.; Bitar, A.N. Evaluating the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Bing AI, and Bard against conventional drug-drug interactions clinical tools. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2023, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.W.; Pushpanathan, K.; Yew, S.M.E.; Lai, Y.; Sun, C.H.; Lam, J.S.H.; Chen, D.Z.; Goh, J.H.L.; Tan, M.C.J.; Sheng, B.; et al. Benchmarking large language models’ performances for myopia care: A comparative analysis of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4.0, and Google Bard. EBioMedicine 2023, 95, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, K.S.; You, J.Y.; Coleman, M.J.; Mathews, P.M.; Ray, V.L.; Riaz, K.M.; De Rojas, J.O.; Wang, A.S.; Watson, S.H.; Koo, E.H.; et al. Quality and agreement with scientific consensus of ChatGPT information regarding corneal transplantation and Fuchs dystrophy. Cornea 2022, 43, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durairaj, K.K.; Baker, O.; Bertossi, D.; Dayan, S.; Karimi, K.; Kim, R.; Most, S.; Robotti, E.; Rosengaus, F. Artificial Intelligence Versus Expert Plastic Surgeon: Comparative Study Shows ChatGPT “Wins” Rhinoplasty Consultations: Should We Be Worried? Facial Plast. Surg. Aesthetic Med. 2024, 26, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levartovsky, A.; Ben-Horin, S.; Kopylov, U.; Klang, E.; Barash, Y. Towards AI-Augmented Clinical Decision Making: An Examination of ChatGPT’s Utility in Acute Ulcerative Colitis Presentations. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2023, 118, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Q.; Tan, J.; Zapadka, M.E.; Ponnatapura, J.; Niu, C.; Myers, K.J.; Wang, G.; Whitlow, C.T. Translating radiology reports into plain language using ChatGPT and GPT-4 with prompt learning: Results, limitations, and potential. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2023, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hagan, R.; Kim, R.H.; Abittan, B.J.; Caldas, S.; Ungar, J.; Ungar, B. Trends in accuracy and appropriateness of alopecia areata information obtained from a popular online large language model, ChatGPT. Dermatology 2023, 239, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushuven, S.; Bentele, M.; Bentele, S.; Gerber, B.; Bansbach, J.; Ganter, J.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Ranisch, R. “ChatGPT, can you help me save my child’s life?”—Diagnostic Accuracy and Supportive Capabilities to lay rescuers by ChatGPT in prehospital Basic Life Support and Paediatric Advanced Life Support cases–an in-silico analysis. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, C.E.; Patel, J.M.; Boyd, L.; Growdon, W.B.; Aviki, E.; Stasenko, M. Let’s chat about cervical cancer: Assessing the accuracy of ChatGPT responses to cervical cancer questions. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 179, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebrael, G.; Sahu, K.K.; Chigarira, B.; Tripathi, N.; Mathew Thomas, V.; Sayegh, N.; Maughan, B.L.; Agarwal, N.; Swami, U.; Li, H. Enhancing triage efficiency and accuracy in emergency rooms for patients with metastatic prostate cancer: A retrospective analysis of artificial intelligence-assisted triage using ChatGPT 4.0. Cancers 2023, 15, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, R.C.T.; Unadkat, S.; Mcneillis, V.; Williamson, A.; Joseph, J.; Randhawa, P.; Andrews, P.; Paleri, V. Artificial intelligence chatbots as sources of patient education material for obstructive sleep apnoea: ChatGPT versus Google Bard. Eur. Arch.-Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2024, 281, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallari, V.; Sacchetto, A.; Saetti, R.; Calabrese, L.; Vittadello, F.; Gazzini, L. Is artificial intelligence ready to replace specialist doctors entirely? ENT specialists vs. ChatGPT: 1-0, ball at the center. Eur. Arch.-Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2024, 281, 995–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athavale, A.; Baier, J.; Ross, E.; Fukaya, E. The potential of chatbots in chronic venous disease patient management. JVS-Vasc. Insights 2023, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikdel, M.; Ghadimi, H.; Tavakoli, M.; Suh, D.W. Assessment of the Responses of the Artificial Intelligence–based Chatbot ChatGPT-4 to Frequently Asked Questions About Amblyopia and Childhood Myopia. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2024, 61, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, E.; Walsh, C.; Hibberd, L. Can artificial intelligence replace biochemists? A study comparing interpretation of thyroid function test results by ChatGPT and Google Bard to practising biochemists. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2024, 61, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazario-Johnson, L.; Zaki, H.A.; Tung, G.A. Use of large language models to predict neuroimaging. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorelik, Y.; Ghersin, I.; Maza, I.; Klein, A. Harnessing language models for streamlined postcolonoscopy patient management: A novel approach. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, M.; Morris, M.T.; Goldfarb, C.A.; Dy, C.J. Appropriateness and reliability of an online artificial intelligence platform’s responses to common questions regarding distal radius fractures. J. Hand Surg. 2024, 49, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Seth, I.; Rozen, W.M.; Hunter-Smith, D.J. Evaluation of the artificial intelligence chatbot on breast reconstruction and its efficacy in surgical research: A case study. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 2360–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.J.; Estephan, L.E.; Sina, E.M.; Mastrolonardo, E.V.; Alapati, R.; Amin, D.R.; Cottrill, E.E. Evaluating ChatGPT responses on thyroid nodules for patient education. Thyroid 2024, 34, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiles, B.B.; Bird, V.G.; Canales, B.K.; DiBianco, J.M.; Terry, R.S. Caution! AI bot has entered the patient chat: ChatGPT has limitations in providing accurate urologic healthcare advice. Urology 2023, 180, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahsepar, A.A.; Tavakoli, N.; Kim, G.H.J.; Hassani, C.; Abtin, F.; Bedayat, A. How AI responds to common lung cancer questions: ChatGPT versus Google Bard. Radiology 2023, 307, e230922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Klang, E.; Sklair-Levy, M.; Cohen, I.; Zippel, D.B.; Balint Lahat, N.; Konen, E.; Barash, Y. Large language model (ChatGPT) as a support tool for breast tumor board. NPJ Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, F.A.; Favier, V.; dos Santos Sobreira Nunes, H.; de Castro, J.V.; Carsuzaa, F.; Meccariello, G.; Vicini, C.; De Vito, A.; Lechien, J.R.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.; et al. Chat GPT for the management of obstructive sleep apnea: Do we have a polar star? Eur. Arch.-Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2024, 281, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morath, B.; Chiriac, U.; Jaszkowski, E.; Deiß, C.; Nürnberg, H.; Hörth, K.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Green, K. Performance and risks of ChatGPT used in drug information: An exploratory real-world analysis. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2023, 31, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balel, Y. Can ChatGPT be used in oral and maxillofacial surgery? J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 124, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasio, A.T.; Mills, F.B., IV; Karavan, M.P., Jr.; Adams, S.B., Jr. Evaluating the quality and usability of artificial intelligence–generated responses to common patient questions in foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023, 8, 24730114231209919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scquizzato, T.; Semeraro, F.; Swindell, P.; Simpson, R.; Angelini, M.; Gazzato, A.; Sajjad, U.; Bignami, E.G.; Landoni, G.; Keeble, T.R.; et al. Testing ChatGPT ability to answer laypeople questions about cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2024, 194, 110077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, D.; Tatekawa, H.; Shimono, T.; Walston, S.L.; Takita, H.; Matsushita, S.; Oura, T.; Mitsuyama, Y.; Miki, Y.; Ueda, D. Accuracy of ChatGPT generated diagnosis from patient’s medical history and imaging findings in neuroradiology cases. Neuroradiology 2024, 66, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, E.T.; Crook, B.S.; Lorentz, S.G.; Danilkowicz, R.M.; Lau, B.C.; Taylor, D.C.; Dickens, J.F.; Anakwenze, O.; Klifto, C.S. Evaluation high-quality of information from ChatGPT (artificial intelligence—large language model) artificial intelligence on shoulder stabilization surgery. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2024, 40, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potapenko, I.; Malmqvist, L.; Subhi, Y.; Hamann, S. Artificial intelligence-based ChatGPT responses for patient questions on optic disc drusen. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 3109–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi-Rafeh, J.; Hanna, S.; Bassiri-Tehrani, B.; Kazan, R.; Nahai, F. Complications following facelift and neck lift: Implementation and assessment of large language model and artificial intelligence (ChatGPT) performance across 16 simulated patient presentations. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suthar, P.P.; Kounsal, A.; Chhetri, L.; Saini, D.; Dua, S.G. Artificial intelligence (AI) in radiology: A deep dive into ChatGPT 4.0’s accuracy with the American Journal of Neuroradiology’s (AJNR) “Case of the Month”. Cureus 2023, 15, e43958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Rafeh, J.; Xu, H.H.; Kazan, R.; Tevlin, R.; Furnas, H. Large language models and artificial intelligence: A primer for plastic surgeons on the demonstrated and potential applications, promises, and limitations of ChatGPT. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2024, 44, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.A.; Gonzalez, A.E.V.; Polianovskaia, A.; Sanchez, R.A.; Arce, V.M.; Mustafa, A.; Vypritskaya, E.; Gutierrez, O.P.; Bashir, M.; Sedeh, A.E. The future of patient education: AI-driven guide for type 2 diabetes. Cureus 2023, 15, e48919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhi, A.; Pipil, N.; Santra, S.; Mondal, S.; Behera, J.K.; Mondal, H. The capability of ChatGPT in predicting and explaining common drug-drug interactions. Cureus 2023, 15, e36272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deiana, G.; Dettori, M.; Arghittu, A.; Azara, A.; Gabutti, G.; Castiglia, P. Artificial intelligence and public health: Evaluating ChatGPT responses to vaccination myths and misconceptions. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland-Halperin, L.R.; O’Brien, L.; Copeland, M. Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence–generated Responses to Common Plastic Surgery Questions. Plast. Reconstr.-Surg.-Glob. Open 2023, 11, e5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, E.M.; Juhasz-Böss, I.; Solomayer, E.F.; Truhn, D.; Keller, C.; Heinrich, V.; Braun, B.J. Will I soon be out of my job? Quality and guideline conformity of ChatGPT therapy suggestions to patient inquiries with gynecologic symptoms in a palliative setting. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 1543–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, S.; Holzapfel, S.; Kappenschneider, T.; Meyer, M.; Maderbacher, G.; Grifka, J.; Holzapfel, D.E. Arthrosis diagnosis and treatment recommendations in clinical practice: An exploratory investigation with the generative AI model GPT-4. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2023, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caglar, U.; Yildiz, O.; Meric, A.; Ayranci, A.; Gelmis, M.; Sarilar, O.; Ozgor, F. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions related to pediatric urology. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2024, 20, 26.e1–26.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, B.; Ocakoglu, G.; Yetemen, M.; Kaygisiz, O. Can ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence language model, provide accurate and high-quality patient information on prostate cancer? Urology 2023, 180, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Q.; Chen, G.; Xia, B.; Zeng, D.; Chen, G.; Guo, C. AI’s deep dive into complex pediatric inguinal hernia issues: A challenge to traditional guidelines? Hernia 2023, 27, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.y.; Li, H.; Liu, X.l.; Li, C.; Yang, L.q.; Zhang, Y.j.; Luo, J.; Zhao, J. Appropriateness and comprehensiveness of using ChatGPT for perioperative patient education in thoracic surgery in different language contexts: Survey study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2023, 12, e46900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpanathan, K.; Lim, Z.W.; Yew, S.M.E.; Chen, D.Z.; Lin, H.A.H.; Goh, J.H.L.; Wong, W.M.; Wang, X.; Tan, M.C.J.; Koh, V.T.C.; et al. Popular large language model chatbots’ accuracy, comprehensiveness, and self-awareness in answering ocular symptom queries. Iscience 2023, 26, 108163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroiwa, T.; Sarcon, A.; Ibara, T.; Yamada, E.; Yamamoto, A.; Tsukamoto, K.; Fujita, K. The potential of ChatGPT as a self-diagnostic tool in common orthopedic diseases: Exploratory study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, E.B.; Towbin, A.J.; Wingrove, P.; Shafique, U.; Haas, B.; Kitts, A.B.; Feldman, J.; Furlan, A. Enhancing patient communication with Chat-GPT in radiology: Evaluating the efficacy and readability of answers to common imaging-related questions. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2024, 21, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.J.; Arepalli, S.R.; Fromal, O.; Choi, J.D.; Jain, N. Artificial intelligence chatbot performance in triage of ophthalmic conditions. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 59, e301–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haemmerli, J.; Sveikata, L.; Nouri, A.; May, A.; Egervari, K.; Freyschlag, C.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Migliorini, D.; Momjian, S.; Sanda, N.; et al. ChatGPT in glioma adjuvant therapy decision making: Ready to assume the role of a doctor in the tumour board? BMJ Health Care Inform. 2023, 30, e100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazi, A.H.D.; Mahjoubi, M.; Shahabi, S.; Alqahtani, A.R.; Haddad, A.; Pazouki, A.; Prasad, A.; Safadi, B.Y.; Chiappetta, S.; Taskin, H.E.; et al. Bariatric evaluation through AI: A survey of expert opinions versus ChatGPT-4 (BETA-SEOV). Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, G.Z.; Zúñiga, D.; Vindel, C.L.; Yoong, A.M.; Hincapie, S.; Zúñiga, A.B.; Zúñiga, P.; Salazar, E.; Zúñiga, B. Efficacy of AI Chats to determine an emergency: A comparison between OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing AI Chat. Cureus 2023, 15, e45473. [Google Scholar]

- Vaira, L.A.; Lechien, J.R.; Abbate, V.; Allevi, F.; Audino, G.; Beltramini, G.A.; Bergonzani, M.; Bolzoni, A.; Committeri, U.; Crimi, S.; et al. Accuracy of ChatGPT-generated information on head and neck and oromaxillofacial surgery: A multicenter collaborative analysis. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2024, 170, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro Desideri, L.; Roth, J.; Zinkernagel, M.; Anguita, R. Application and accuracy of artificial intelligence-derived large language models in patients with age related macular degeneration. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2023, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, O.M.; Gasparello, G.G.; Hartmann, G.C.; Casagrande, F.A.; Pithon, M.M. Assessing the reliability of ChatGPT: A content analysis of self-generated and self-answered questions on clear aligners, TADs and digital imaging. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2023, 28, e2323183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balas, M.; Janic, A.; Daigle, P.; Nijhawan, N.; Hussain, A.; Gill, H.; Lahaie, G.L.; Belliveau, M.J.; Crawford, S.A.; Arjmand, P.; et al. Evaluating ChatGPT on orbital and oculofacial disorders: Accuracy and readability insights. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 40, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, B.S.; Park, C.N.; Hurley, E.T.; Richard, M.J.; Pidgeon, T.S. Evaluation of online artificial intelligence-generated information on common hand procedures. J. Hand Surg. 2023, 48, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Ahmad, A.; Bhalla, P.; Goyal, K. Assessing the efficacy of ChatGPT in solving questions based on the core concepts in physiology. Cureus 2023, 15, e43314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, N.; Wong, V.W.S.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Sebastiani, G.; Castera, L.; Hassan, C.; Manousou, P.; Miele, L.; Peck, R.; et al. Accuracy, reliability, and comprehensibility of chatgpt-generated medical responses for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Eppler, M.; Ayo-Ajibola, O.; Loh-Doyle, J.C.; Nabhani, J.; Samplaski, M.; Gill, I.; Cacciamani, G.E. Evaluating the effectiveness of artificial intelligence–powered large language models application in disseminating appropriate and readable health information in urology. J. Urol. 2023, 210, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, C.; Edupuganti, N.R.; Patel, P.A.; Bui, T.; Sheth, V. Evaluating the artificial intelligence performance growth in ophthalmic knowledge. Cureus 2023, 15, e45700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draschl, A.; Hauer, G.; Fischerauer, S.F.; Kogler, A.; Leitner, L.; Andreou, D.; Leithner, A.; Sadoghi, P. Are ChatGPT’s Free-Text Responses on Periprosthetic Joint Infections of the Hip and Knee Reliable and Useful? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.J.; Ayo-Ajibola, O.; Lin, M.E.; Swanson, M.S.; Chambers, T.N.; Kwon, D.I.; Kokot, N.C. Evaluation of oropharyngeal cancer information from revolutionary artificial intelligence chatbot. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 2252–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, I.A.; Zhang, Y.V.; Govil, D.; Majid, I.; Chang, R.T.; Sun, Y.; Shue, A.; Chou, J.C.; Schehlein, E.; Christopher, K.L.; et al. Comparison of ophthalmologist and large language model chatbot responses to online patient eye care questions. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2330320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benary, M.; Wang, X.D.; Schmidt, M.; Soll, D.; Hilfenhaus, G.; Nassir, M.; Sigler, C.; Knödler, M.; Keller, U.; Beule, D.; et al. Leveraging large language models for decision support in personalized oncology. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2343689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, T.I.; Roos, J.; Kaczmarczyk, R. Large language models for therapy recommendations across 3 clinical specialties: Comparative study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e49324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Musheyev, D.; Bockelman, D.; Loeb, S.; Kabarriti, A.E. Assessment of artificial intelligence chatbot responses to top searched queries about cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, R.K.; Ogbodo, J.C.; Wee, Y.Z.; Gan, A.Z.; González, P.A. Performance of Google bard and ChatGPT in mass casualty incidents triage. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 75, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).