Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Prenatal chromosomal testing (karyotype, MLPA, and chromosome sequencing) may fail to detect monogenic causes of fetal central nervous system anomalies, even in the presence of ventriculomegaly.

- Trio-based whole-exome sequencing enabled the definitive postnatal diagnosis of a DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder caused by a de novo pathogenic missense variant.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Earlier selective implementation of prenatal exome sequencing in fetuses with complex or non-isolated CNS anomalies could significantly improve diagnostic yield and prognostic counseling.

- Integration of clinical genetics into multidisciplinary prenatal care pathways is essential to optimize decision-making, perinatal planning, and family counseling.

Abstract

Background: Prenatal detection of fetal structural anomalies often prompts chromosomal analysis; however, chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) has limited diagnostic yield for monogenic disorders. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying single-gene etiologies, particularly in cases with complex neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Case Presentation: We report a female infant presenting with prenatally detected ventriculomegaly and inconclusive chromosomal testing. Prenatal investigations, including karyotyping and genome-wide chromosomal sequencing, identified several copy number variants classified as variants of uncertain significance but failed to establish a definitive diagnosis. Postnatally, the patient developed progressive neurological abnormalities, including microcephaly, facial dysmorphism, dystonic movements, and severe global developmental delay. Trio-based whole-exome sequencing identified a heterozygous de novo pathogenic missense variant in the DDX3X gene (c.976C>T; p.Arg326Cys), establishing the diagnosis of DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Conclusions: This case highlights the diagnostic limitations of standard prenatal chromosomal testing in detecting monogenic neurodevelopmental disorders and underscores the critical role of timely genetic counseling and exome sequencing. Earlier selective implementation of WES during pregnancy could have enabled an earlier diagnosis, improved prognostic counseling, and optimized clinical decision-making.

1. Background and Clinical Significance:

Congenital anomalies are a leading cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality, with a substantial proportion attributable to pathogenic single-gene variants that remain undetectable by conventional cytogenetic methods. In pregnancies complicated by fetal structural anomalies, chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) or chromosomal sequencing, performed by medium-coverage whole genome sequencing is widely recommended as a first-tier diagnostic test due to its ability to detect genome-wide copy number variants (CNVs) at high resolution [1,2,3,4,5]. However, CMA is inherently limited in its capacity to identify balanced rearrangements and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) underlying monogenic disorders, and its diagnostic yield in fetuses with structural anomalies typically ranges from 4% to 20%, depending on the indication and analytical platform used [2,6].

Recent advances in next-generation sequencing have established whole-exome sequencing (WES) as a powerful approach for detecting sequence-level variants responsible for monogenic disease. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the American Academy of Pediatrics now recommend exome or genome sequencing as a first-tier diagnostic test for children with global developmental delay, intellectual disability, or congenital anomalies, citing improved diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness when implemented early in the diagnostic pathway [1,7]. In the prenatal setting, WES provides an incremental diagnostic yield of approximately 10–40% in fetuses with structural anomalies and previously negative standard genetic testing, with the highest yields reported in central nervous system anomalies and multisystem involvement [6,8,9,10,11].

International professional societies, including the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis and the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists, support the use of genome-wide sequencing in pregnancies complicated by multiple or severe fetal anomalies, emphasizing the critical role of detailed phenotyping and multidisciplinary genetic counseling [3,12].

Within this clinical and diagnostic framework, DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder exemplifies the limitations of conventional prenatal testing strategies. The DDX3X gene is located on chromosome Xp11.4 and encodes a 662–amino acid DEAD-box RNA helicase that plays a central role in RNA metabolism, including transcriptional and translational regulation, pre-mRNA splicing, RNA stability, cell cycle control, and cellular stress responses [13]. The protein contains two highly conserved functional domains—the helicase ATP-binding domain and the helicase C-terminal domain—both essential for enzymatic activity and enriched for pathogenic missense variants. DDX3X is also a component of RNA–protein granules, including neuronal transport granules and cytoplasmic stress granules, underscoring its importance for neuronal homeostasis and brain development [13].

DDX3X is ubiquitously expressed across human tissues but plays a particularly critical role during embryogenesis and neurodevelopment. During fetal cortical development, DDX3X regulates neural progenitor proliferation, neuronal differentiation, and cortical lamination. Importantly, DDX3X exhibits sex-specific expression patterns [14]. The gene partially escapes X-chromosome inactivation in a context-dependent manner, resulting in higher overall DDX3X expression in females. Males possess a Y-linked paralog, DDX3Y, which shares high sequence similarity and partial functional redundancy with DDX3X but demonstrates more restricted and variable expression, with particularly limited expression in large regions of the central nervous system, contributing to sex-specific vulnerability to DDX3X loss [15].

Pathogenic variants in DDX3X cause DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder (DDX3X-NDD; OMIM #300958). This condition represents one of the more frequent monogenic causes of neurodevelopmental impairment in females. To date, more than 200 affected individuals have been reported, with the largest published clinical cohort including over 100 patients [16]. While the postnatal phenotype of DDX3X-NDD is well characterized, prenatal imaging findings are less systematically documented; nevertheless, ventriculomegaly, corpus callosum abnormalities, and other central nervous system structural anomalies have been reported as presenting prenatal features [14].

The clinical phenotype is broad, typically including global developmental delay or intellectual disability, speech and language impairment, hypotonia, motor delay, movement disorders, and structural brain abnormalities such as ventriculomegaly, corpus callosum hypoplasia or dysgenesis, reduced white matter volume, and polymicrogyria [16]. Additional features may include microcephaly, epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and multisystem involvement [16]. Genotype–phenotype correlations show that approximately half of pathogenic variants are missense mutations, often clustering in the helicase domains and associated with more severe neurological phenotypes, especially polymicrogyria [17]. Truncating variants support haploinsufficiency, while severe missense mutations may exert dominant-negative effects by disrupting RNA–protein granule formation and translation in neural progenitors [17]. DDX3X-NDD exhibits a striking female predominance, with most affected females harboring de novo pathogenic variants and low recurrence risk. Nevertheless, de novo pathogenic variants in males have also been reported [16].

In fetuses with ventriculomegaly and negative chromosomal testing, prenatal whole-exome sequencing has been shown to identify pathogenic single-gene variants in up to 48.5% of cases [18]. More broadly, meta-analyses of fetal central nervous system anomalies report pooled incremental diagnostic yields of approximately 38% for CNS anomalies overall and up to 46% for non-isolated CNS anomalies, representing the highest diagnostic yield among all fetal structural anomaly categories [9]. These data highlight the substantial diagnostic gap that remains when relying solely on conventional chromosomal testing strategies.

The diagnostic limitations of conventional prenatal testing are exemplified by DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder, in which pathogenic de novo single-nucleotide variants are not detectable by karyotype or chromosomal microarray analysis but can be readily identified through trio-based whole-exome sequencing.

Early implementation of exome sequencing in pregnancies with complex neurodevelopmental phenotypes enables timely molecular diagnosis and informed prognostic counseling. When delivered within a multidisciplinary prenatal care team involving maternal–fetal medicine specialists, pediatric neurologists, radiologists, and clinical geneticists, this approach supports accurate interpretation of genomic findings and appropriate family counseling. This underscores the need for integrated prenatal care models that combine advanced genomic technologies with expert phenotyping and coordinated multidisciplinary evaluation. This case report does not aim to expand the phenotypic spectrum of DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder, but rather to illustrate a diagnostic gap in prenatal genetic evaluation and the clinical consequences of delayed molecular diagnosis in the setting of fetal CNS anomalies.

2. Case Presentation

The patient is a female infant born from a third pregnancy to a 36-year-old mother (one healthy child and one previous spontaneous miscarriage). The pregnancy was initially uncomplicated. At the second-trimester detailed prenatal ultrasound anomaly scan (22 + 4 weeks of gestation), mild bilateral ventriculomegaly with visualization of the third ventricle was detected. No additional structural anomalies or indirect sonographic markers suggestive of chromosomal aneuploidy were identified. Maternal serological testing for Toxoplasma gondii, Epstein–Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus was negative.

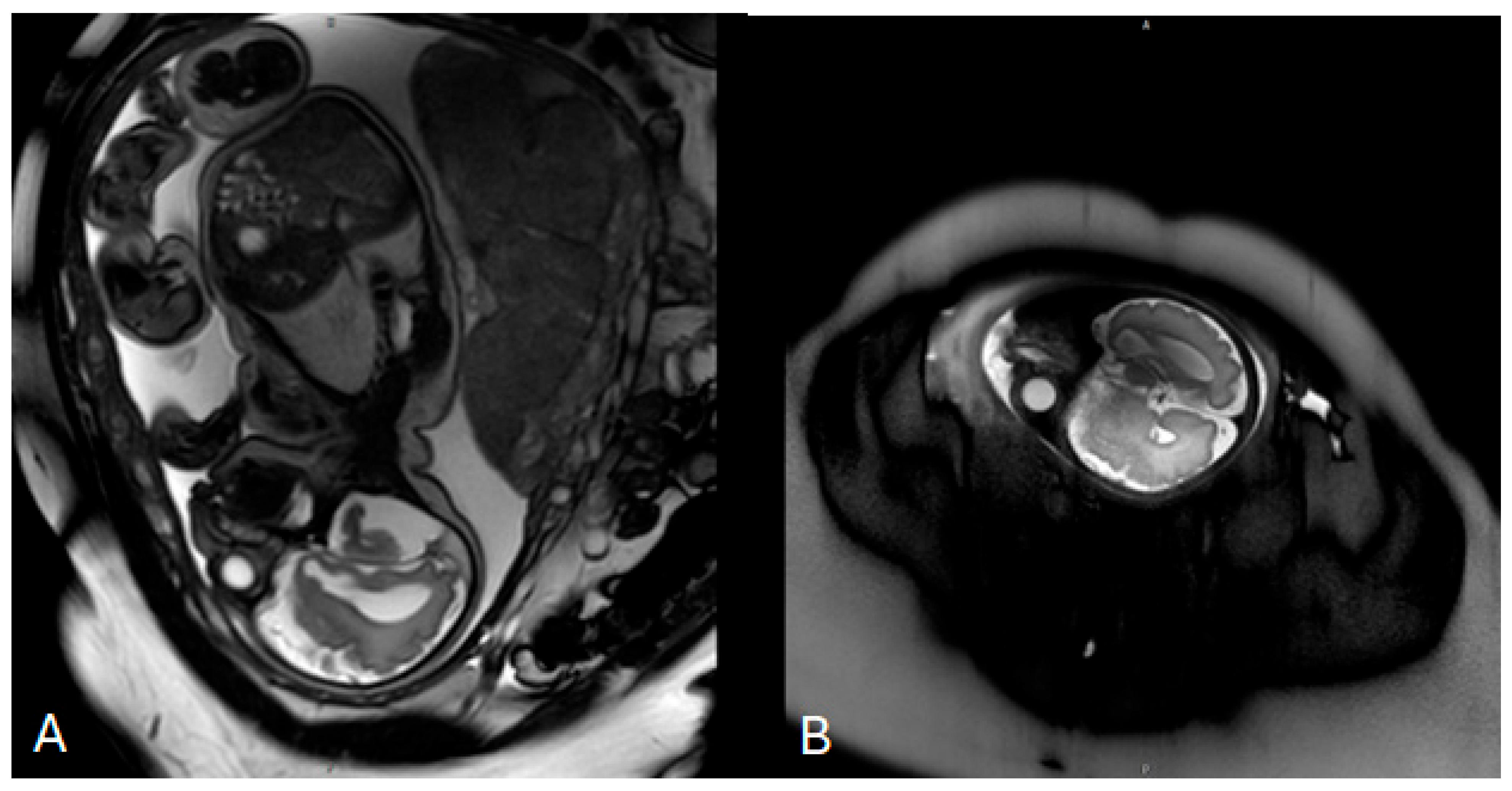

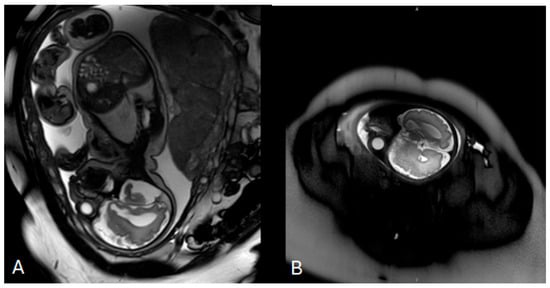

Invasive prenatal genetic testing was performed via amniocentesis. Conventional cytogenetic analysis revealed a normal female karyotype (46,XX). Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) for microdeletion and microduplication screening yielded negative results. This was followed by genome-wide chromosome sequencing (ChromoSeq, BGI VISTA™), which identified four copy number variants, all classified as variants of uncertain significance. No pathogenic chromosomal aneuploidies or clinically relevant microdeletions or microduplications were detected. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at 33 weeks of gestation demonstrated mild ventriculomegaly without evidence of neural tube defects (Figure 1). No further genomic testing was pursued during pregnancy, and prenatal consultation with a clinical geneticist was not documented.

Figure 1.

Prenatal fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at 33 weeks of gestation. (A) Axial T2-weighted image of the fetal brain demonstrating mild bilateral ventriculomegaly with visualization of the lateral ventricles. (B) Sagittal T2-weighted image confirming ventricular enlargement without additional major structural brain malformations at the time of examination.

The infant was delivered at 39 weeks of gestation by vaginal delivery following a prolonged labor complicated by a nuchal cord. Apgar scores were 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. Birth parameters were within the normal range for gestational age, with a birth weight of 3180 g, length of 52 cm, and head circumference of 33 cm. The neonatal course was notable for delayed postnatal adaptation and feeding difficulties, as the infant did not latch effectively in the immediate postnatal period and required oxygen support for approximately 48 h. The patient was discharged on day four of life.

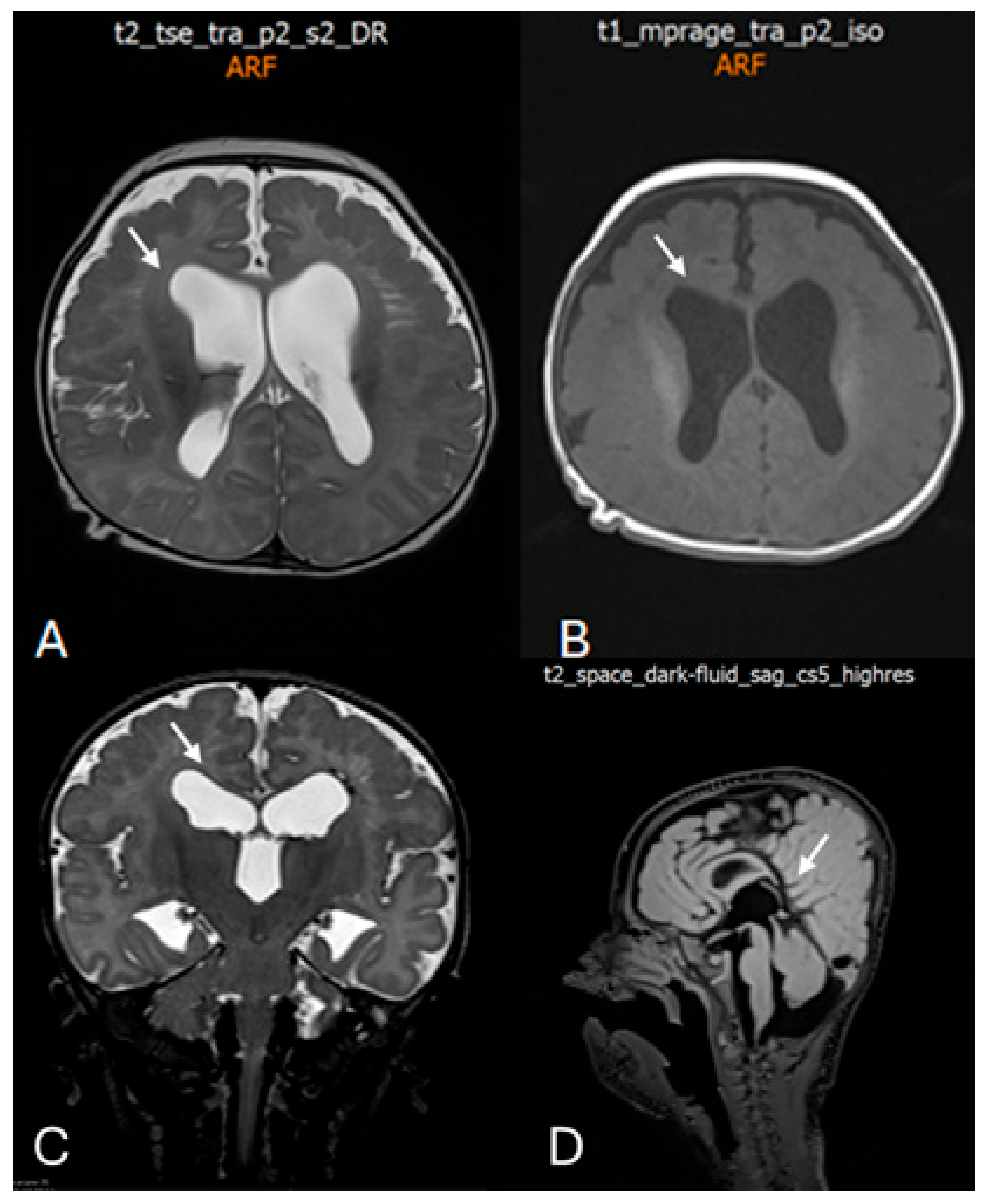

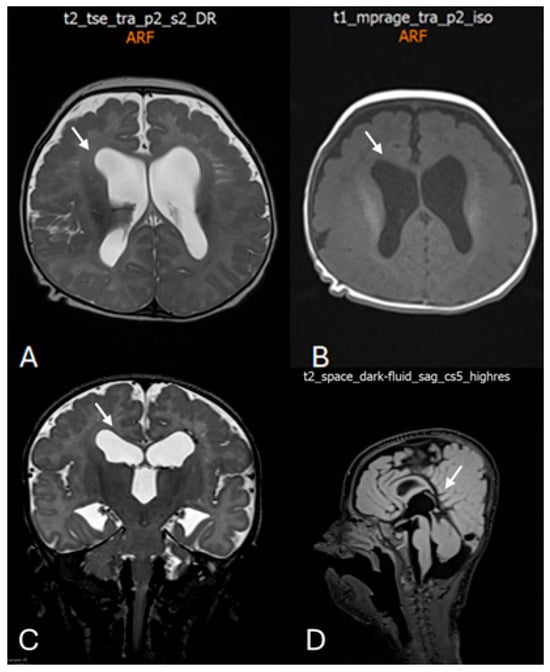

At the age of 2 months and 20 days, the infant was evaluated for irritability and episodic opisthotonic posturing. Transfontanelle ultrasonography revealed ventriculomegaly with enlargement of the lateral and third ventricles. At 4 months of age, neurological examination demonstrated plagiocephaly, facial dysmorphism (Figure 2), and signs of a pyramidal syndrome affecting all four limbs. Brain MRI confirmed ventriculomegaly and additionally revealed chronic changes in the left periventricular region consistent with prior germinal matrix hemorrhage, as well as diffuse polymicrogyria predominantly involving the frontal lobes (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Clinical photograph of the patient in early infancy demonstrating facial dysmorphism, including relatively prominent eyes, full cheeks, an apparently shortened philtrum, a small mouth with full lips, and mildly low-set ears with subtle posterior rotation and simplified auricular morphology. The eyes are masked to protect patient privacy. These facial features are consistent with previously reported mild craniofacial dysmorphism in individuals with DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder, including low-set or posteriorly rotated ears and subtle midline facial anomalies.

Figure 3.

Postnatal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at 4 months of age. (A) Axial T2-weighted image demonstrating marked bilateral ventriculomegaly with symmetric dilatation of the lateral ventricles and reduced surrounding white matter volume. White arrow indicates enlargement of the lateral ventricles. (B) Axial T1-weighted image confirming ventriculomegaly and altered ventricular configuration (white arrow). (C) Coronal T2-weighted image showing symmetric enlargement of the lateral ventricles and dilatation of the third ventricle (white arrow). (D) Midline sagittal T2-weighted image illustrating the ventricular axis and involvement of the third ventricle (white arrow), providing additional characterization of the ventricular system.

Over subsequent follow-up, the phenotype evolved toward severe neurodevelopmental impairment, characterized by progressive microcephaly, emerging dysmorphic facial features (relatively prominent eyes, full cheeks, an apparently shortened philtrum, a small mouth with full lips, and mildly low-set ears with subtle posterior rotation and simplified auricular morphology), and increasing motor abnormalities. Neurological examination demonstrated poor head control, axial hypotonia with evolving increased tone in the limbs, hyperreflexia with expanded reflexogenic zones, distal spasticity, and frequent hyperkinetic/dystonic movements, resulting in a cerebral palsy–like clinical presentation. Developmentally, the patient showed profound delay across all domains, with markedly delayed motor milestones and limited visual engagement.

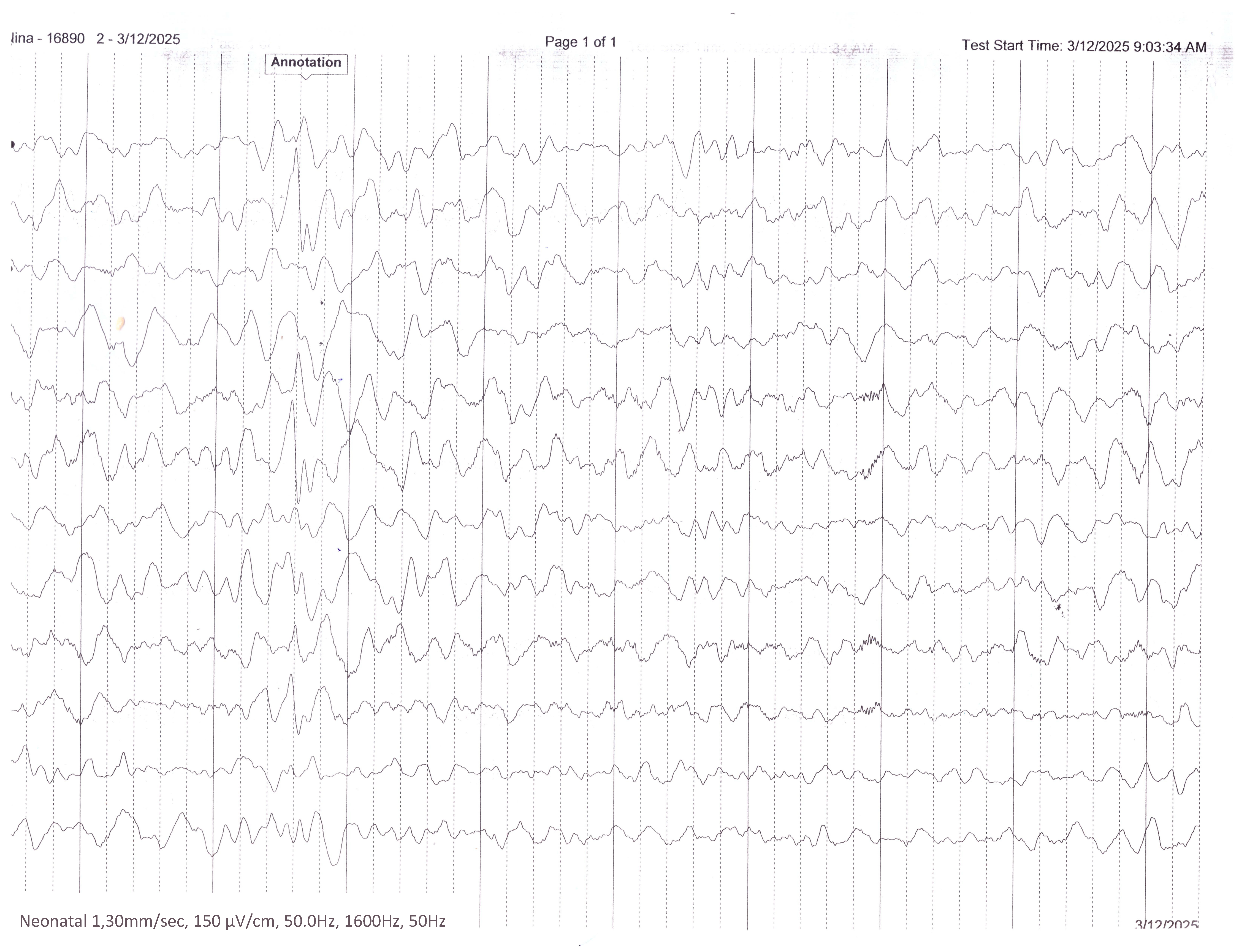

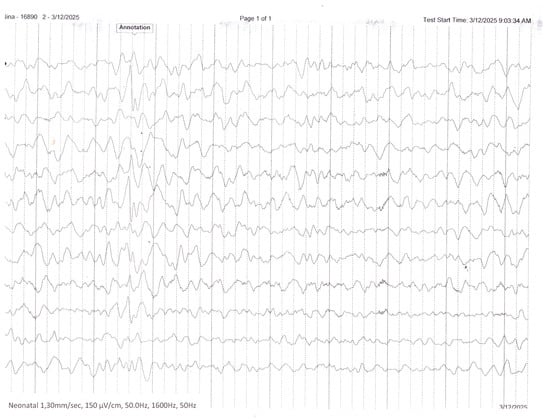

At 7 months of age, the patient was admitted to a pediatric neurology unit for comprehensive evaluation. Clinical assessment confirmed progressive microcephaly, failure to thrive, and quadriparetic cerebral palsy with frequent hyperkinetic movements and dystonic episodes. Severe global developmental delay was evident, including absence of auditory fixation and profound impairment of both motor and cognitive milestones. Electroencephalography (EEG) (Figure 4) revealed abnormal background activity with intermittent focal slowing and suspicious epileptiform discharges; however, no unequivocal electroclinical seizures were recorded. In the absence of clear epileptic semiology and given the non-conclusive EEG findings, antiseizure therapy was deferred, with recommendations for video documentation of paroxysmal events and repeat EEG if episodes recurred. Abdominal ultrasound, echocardiography, and visual evoked potentials were normal. Given the complex neurodevelopmental phenotype and inconclusive prenatal genetic investigations, trio-based whole-exome sequencing was performed postnatally. Analysis using the Blueprint Genetics Whole-Exome Family Plus approach identified a heterozygous de novo missense variant in the DDX3X gene: c.976C>T (p.Arg326Cys), thereby establishing the molecular diagnosis of DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder (OMIM #300958).

Figure 4.

Interictal EEG recording performed during infancy demonstrates a disorganized background activity with multifocal epileptiform discharges.

3. Genetic Findings

Trio-based whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed on the patient and both parents using the Blueprint Genetics Whole-Exome Family Plus approach. Sequencing and variant analysis focused on genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and congenital brain malformations, using a phenotype-driven approach. Variant interpretation was conducted according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines.

A heterozygous missense variant was identified in the DDX3X gene: c.976C>T, resulting in the amino acid substitution p.Arg326Cys. The variant was confirmed to have arisen de novo, as it was absent in both parents. It is not present in population reference databases, including gnomAD, supporting its rarity.

The affected residue is highly conserved and located within the helicase ATP-binding domain of the DDX3X protein, a region critical for RNA metabolism and neurodevelopmental processes. In silico prediction tools consistently supported a deleterious effect on protein function. Notably, the same variant has been previously reported in multiple unrelated female individuals with DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder, and another missense substitution affecting the same codon has also been associated with a similar phenotype, indicating functional importance of this amino acid position.

Based on ACMG/AMP criteria, the variant was classified as pathogenic, supported by strong evidence of de novo occurrence (PS2), absence from controls (PM2), multiple independent reports in affected individuals (PS4), and consistent computational and functional domain-based evidence (PP3).

The molecular findings established the diagnosis of DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder, explaining the patient’s complex neurological phenotype, including ventriculomegaly, cortical malformations, progressive microcephaly, severe global developmental delay, and movement disorder.

4. Discussion

The novelty of this case lies not in the identification of a novel variant or an unusual phenotype, but in demonstrating how the timing of genomic testing directly influenced prenatal counseling and clinical decision-making.

This case further highlights the diagnostic limitations of conventional prenatal genetic testing in pregnancies complicated by fetal central nervous system (CNS) anomalies and underscores the clinical value of timely genome-wide sequencing. Despite early sonographic detection of ventriculomegaly and the application of standard invasive investigations, including karyotyping, MLPA-based microdeletion screening, and genome-wide chromosome sequencing, a definitive molecular diagnosis was not achieved during pregnancy.

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that chromosomal testing approaches, while essential first-tier investigations, have limited diagnostic utility for monogenic neurodevelopmental disorders. In contrast, prenatal whole-exome sequencing (WES) provides a substantially higher diagnostic yield in fetuses with CNS anomalies following negative karyotype and chromosomal microarray analysis, with reported yields ranging from approximately 26.5% to 46% [6,9,13,19]. Notably, ventriculomegaly represents one of the prenatal phenotypes with the highest diagnostic yield, with recent studies identifying pathogenic single-gene variants in up to 48.5% of copy number–negative cases, particularly when ventriculomegaly is non-isolated or associated with complex brain malformations [6,9,13,19]. Diagnostic yields are consistently higher for CNS anomalies compared with other fetal structural abnormalities, with isolated CNS anomalies yielding approximately 22%, CNS-only multiple anomalies 33%, and non-isolated CNS anomalies up to 46% [9,13,19].

DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder exemplifies the limitations of copy number-based approaches in this clinical context. Pathogenic variants in DDX3X are predominantly de novo single-nucleotide variants, most often missense or truncating, and therefore remain undetectable by karyotype or copy number-focused approaches. Prenatal and postnatal neuroimaging studies have demonstrated a characteristic spectrum of brain malformations associated with DDX3X variants, including ventriculomegaly, corpus callosum hypoplasia or dysgenesis, polymicrogyria, reduced white matter volume, and abnormalities of the brainstem and cerebellum [14,20,21]. Missense variants affecting the helicase domains, particularly recurrent dominant mutations, are strongly associated with polymicrogyria and severe neurological impairment, consistent with the severe phenotype observed in the present patient [14,20,21].

Beyond establishing a molecular diagnosis, prenatal genomic testing has broad implications for long-term clinical management and family-centered care. Prenatal implementation of WES enables earlier molecular diagnosis, facilitating accurate prognostic assessment, recurrence risk counseling, and informed pregnancy management decisions [22,23,24]. In cases of severe or complex CNS anomalies, some experts now advocate for exome sequencing as a first-tier test, given its ability to detect both pathogenic sequence variants and copy number variants within the time constraints of an ongoing pregnancy [22,23,24]. Early genomic diagnosis further enables anticipatory perinatal care planning, targeted postnatal surveillance, cascade testing of family members, and informed reproductive decision-making for both current and subsequent pregnancies. Previous studies have demonstrated that genomic diagnoses could be established years earlier if sequencing were implemented at the onset of clinical suspicion, thereby avoiding prolonged diagnostic odysseys and their associated psychosocial burden [12,22,23,25,26]. Moreover, a significant proportion of prenatally diagnosed cases harbor inherited pathogenic variants, emphasizing the importance of timely diagnosis for accurate recurrence risk assessment in future pregnancies [23,24].

This case further underscores the critical importance of multidisciplinary prenatal care and early involvement of a clinical geneticist in the diagnostic pathway. In the present patient, the absence of documented prenatal genetic counseling and delayed implementation of genome-wide sequencing contributed to a postponed molecular diagnosis. A structured multidisciplinary approach, guided by detailed fetal phenotyping and comprehensive pre- and post-test counseling, is essential to ensure accurate interpretation of genomic findings and to maximize both clinical and personal utility for affected families [12,26].

From a clinical practice perspective, amniocentesis with chromosomal microarray analysis or chromosomal sequencing should remain the initial diagnostic step when ventriculomegaly is detected. However, clinicians must explicitly counsel families regarding the limitations of CMA in detecting monogenic disorders. For fetuses with CNS anomalies and non-diagnostic standard testing, trio-based WES should be strongly considered, particularly in cases with multiple CNS findings, complex phenotypes, or recurrent adverse pregnancy outcomes. Recent systematic reviews and professional society recommendations support the integration of WES into prenatal diagnostic algorithms for fetal CNS anomalies to enable accurate prognostic counseling and informed decision-making [9,12,24,25,26,27].

In the present case, earlier implementation of prenatal WES in the setting of fetal ventriculomegaly could have enabled prenatal diagnosis of DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder. This would have facilitated comprehensive counseling regarding prognosis, recurrence risk, and pregnancy management options. Collectively, these findings reinforce the need for early involvement of clinical genetics specialists and systematic integration of advanced genomic technologies into prenatal diagnostic pathways for fetal CNS anomalies.

Earlier prenatal molecular diagnosis in this case would not have altered postnatal treatment options, but it would have enabled comprehensive prognostic counseling and informed reproductive decision-making, including pregnancy management options in accordance with parental values and local legal regulations.

5. Conclusions

This case demonstrates that conventional prenatal genetic testing, while essential, may be insufficient for establishing a molecular diagnosis in fetuses with complex central nervous system anomalies. DDX3X-related neurodevelopmental disorder exemplifies a class of monogenic conditions in which pathogenic single-nucleotide variants are not detectable by karyotype, MLPA-based screening, or copy number-focused approaches, yet can be readily identified by whole-exome sequencing.

Accumulating evidence indicates that in selected high-risk scenarios—particularly fetuses with ventriculomegaly, cortical malformations, or non-isolated CNS anomalies—prenatal exome sequencing provides a superior diagnostic yield compared with stepwise chromosomal testing strategies. In such contexts, early implementation of trio-based WES may represent the most efficient diagnostic approach, enabling timely molecular diagnosis, accurate prognostic counseling, and informed pregnancy and perinatal management.

The present case supports earlier integration of exome sequencing into the prenatal evaluation of fetal CNS anomalies, provided that testing is performed within a multidisciplinary clinical framework and accompanied by expert genetic counseling. Early involvement of a clinical geneticist and coordinated multidisciplinary care are critical to maximizing both the clinical and personal utility of genomic findings. Early implementation of exome sequencing in pregnancies complicated by complex neurodevelopmental phenotypes enables timely molecular diagnosis, informed prognostic counseling, and optimized clinical decision-making when delivered within a multidisciplinary prenatal care framework involving maternal–fetal medicine specialists, pediatric neurologists, radiologists, and clinical geneticists. This approach ensures accurate interpretation of genomic findings and appropriate counseling of affected families, underscoring the need for integrated prenatal care models that combine advanced genomic technologies with expert phenotyping and coordinated multidisciplinary evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.I. and M.P.; clinical evaluation and investigation, M.P. and I.S.-I.; genetic analysis and interpretation, H.I.; methodology, H.I.; formal analysis, H.I.; data curation, M.P. and I.S.-I.; writing—original draft preparation, H.I.; writing—review and editing, H.I. and I.S.-I.; visualization, H.I.; supervision, M.P. and H.I.; project administration, H.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by programme “Research, Innovation and Digitalisation for Smart Transformation” 2021-2027, funded by the European Union, Project BG16RFPR002-1.014-0007 Center for Competence “PERIMED-2”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient’s legal guardians to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to programme “Research, Innovation and Digitalisation for Smart Transformation” 2021-2027, funded by the European Union, Project BG16RFPR002-1.014-0007 “Center for Competence “PERIMED-2” for supporting this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| AMP | Association for Molecular Pathology |

| aCGH | Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization |

| BGI | Beijing Genomics Institute |

| CMA | Chromosomal Microarray Analysis |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CNV | Copy Number Variant |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ES | Exome Sequencing |

| gnomAD | Genome Aggregation Database |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| MLPA | Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SNV | Single-Nucleotide Variant |

| VUS | Variant of Uncertain Significance |

| WES | Whole-Exome Sequencing |

References

- Rodan, L.H.; Stoler, J.; Chen, E.; Geleske, T. Genetic Evaluation of the Child with Intellectual Disability or Global Developmental Delay: Clinical Report. Pediatrics 2025, 156, e2025072219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, M.H.K.; Choy, K.W. The Role of Chromosomal Microarray and Exome Sequencing in Prenatal Diagnosis. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 33, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.; Wapner, R. Prenatal Diagnosis by Chromosomal Microarray Analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugoff, L.; Norton, M.E.; Kuller, J.A. The Use of Chromosomal Microarray for Prenatal Diagnosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, B2–B9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, J.; Wu, Q.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J. Chromosomal Abnormalities Detected by Chromosomal Microarray Analysis and Pregnancy Outcomes of 4211 Fetuses with High-Risk Prenatal Indications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, L.; Aktuna, S.; Ünsal, E. Diagnostic Performance of Chromosomal Microarray and Whole Exome Sequencing in Fetal Structural Anomalies: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mantilla, P.J.; Hu, Y.; Myers, S.M.; Finucane, B.M.; Ledbetter, D.H.; Martin, C.L.; Moreno-De-Luca, A. Diagnostic Yield of Exome Sequencing in Cerebral Palsy and Implications for Genetic Testing Guidelines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Xu, B.; Xiang, Q.; Hu, T.; Liu, S. Evaluating the Clinical Utility and Strategy of Whole-Exome Sequencing Testing for Fetuses with Increased Nuchal Translucency. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 233, 483.e1–483.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionni, E.; Guadagnolo, D.; Mastromoro, G.; Pizzuti, A. Prenatal Genome-Wide Sequencing Analysis (Exome or Genome) in Detecting Pathogenic Single Nucleotide Variants in Fetal Central Nervous System Anomalies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellis, R.; Oprych, K.; Scotchman, E.; Hill, M.; Chitty, L.S. Diagnostic Yield of Exome Sequencing for Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Structural Anomalies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prenat. Diagn. 2022, 42, 662–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Veyver, I.B.; Chandler, N.; Wilkins-Haug, L.E.; Wapner, R.J.; Chitty, L.S. International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis Updated Position Statement on the Use of Genome-Wide Sequencing for Prenatal Diagnosis. Prenat. Diagn. 2022, 42, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazier, J.; Hartley, T.; Brock, J.A.; Caluseriu, O.; Chitayat, D.; Laberge, A.-M.; Langlois, S.; Lauzon, J.; Nelson, T.N.; Parboosingh, J.; et al. Clinical Application of Fetal Genome-Wide Sequencing during Pregnancy: Position Statement of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists. J. Med. Genet. 2022, 59, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mueffling, A.; Garcia-Forn, M.; De Rubeis, S. DDX3X syndrome: From clinical phenotypes to biological insights. J. Neurochem. 2024, 168, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lennox, A.L.; Hoye, M.L.; Jiang, R.; Johnson-Kerner, B.L.; Suit, L.A.; Venkataramanan, S.; Sheehan, C.J.; Alsina, F.C.; Fregeau, B.; Aldinger, K.A.; et al. Pathogenic DDX3X Mutations Impair RNA Metabolism and Neurogenesis during Fetal Cortical Development. Neuron 2020, 106, 404–420.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mossa, A.; Dierdorff, L.; Lukin, J.; Garcia-Forn, M.; Wang, W.; Mamashli, F.; Park, Y.; Fiorenzani, C.; Akpinar, Z.; Kamps, J.; et al. Sex-specific perturbations of neuronal development caused by mutations in the autism risk gene DDX3X. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levy, T.; Siper, P.M.; Lerman, B.; Halpern, D.; Zweifach, J.; Belani, P.; Thurm, A.; Kleefstra, T.; Berry-Kravis, E.; Buxbaum, J.D.; et al. DDX3X Syndrome: Summary of Findings and Recommendations for Evaluation and Care. Pediatr. Neurol. 2023, 138, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosti, F.; Hoye, M.L.; Escobar-Tomlienovich, C.F.; Silver, D.L. Multi-modal investigation reveals pathogenic features of diverse DDX3X missense mutations. PLoS Genet. 2025, 21, e1011555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, H.; Gao, J.; Guo, M.; Yue, H.; Guo, R.; Gao, G.; Sun, X.; Wu, J. Genetic Etiology of Ventriculomegaly in 73 Fetuses Identified by High-Throughput Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, B.; Ariaei, A.; Heidari-Foroozan, M.; Banihashemian, M.; Ghorani, H.; Rashidi-Nezhad, A.; Kazemi, M.A.; Taheri, M.S. Diagnostic Yield of Prenatal Exome Sequencing in the Genetic Screening of Fetuses with Brain Anomalies Detected by MRI and Ultrasonography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 131, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhong, L.; Zhong, R.; Liang, M.; Ma, L.; Zhang, V.W.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; et al. Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Structural Anomalies Using Medium-Coverage Whole Genome Sequencing (CMA-Seq): A Large-Scale Comparative Study with CMA in 3973 Pregnancies. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, M.; Torella, A.; Severino, M.; Morana, G.; Castello, R.; Accogli, A.; Verrico, A.; Vari, M.S.; Cappuccio, G.; Pinelli, M.; et al. Three De Novo DDX3X Variants Associated with Distinctive Brain Developmental Abnormalities and Brain Tumor in Intellectually Disabled Females. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, J.; McMullan, D.J.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Rinck, G.; Hamilton, S.J.; Quinlan-Jones, E.; Prigmore, E.; Keelagher, R.; Best, S.K.; Carey, G.K.; et al. Prenatal Exome Sequencing Analysis in Fetal Structural Anomalies Detected by Ultrasonography (PAGE): A Cohort Study. Lancet 2019, 393, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, S.; Aggarwal, V.; Giordano, J.L.; Stosic, M.; Wou, K.; Bier, L.; Spiegel, E.; Brennan, K.; Stong, N.; Jobanputra, V.; et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing in the Evaluation of Fetal Structural Anomalies: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet 2019, 393, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaron, Y.; Ofen Glassner, V.; Mory, A.; Henig, N.Z.; Kurolap, A.; Bar Shira, A.; Goldstein, D.B.; Marom, D.; Ben Sira, L.; Feldman, H.B.; et al. Exome Sequencing as First-Tier Test for Fetuses with Severe Central Nervous System Structural Anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mone, F.; McMullan, D.J.; Williams, D.; Chitty, L.S.; Maher, E.R.; Kilby, M.D.; Fetal Genomics Steering Group of the British Society for Genetic Medicine; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Evidence to Support the Clinical Utility of Prenatal Exome Sequencing in Evaluation of the Fetus with Congenital Anomalies: Scientific Impact Paper No. 64. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, e39–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soden, S.E.; Saunders, C.J.; Willig, L.K.; Farrow, E.G.; Smith, L.D.; Petrikin, J.E.; Lepichon, J.-B.; Miller, N.A.; Thiffault, I.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; et al. Effectiveness of Exome and Genome Sequencing Guided by Acuity of Illness for Diagnosis of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 265ra168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesson, A.; Cohen, J.S. Genetic Counseling in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a036533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.