Abstract

Background: Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in children is an issue of growing interest in the scientific literature, with various studies focused on the adolescent population published in recent years. Nevertheless, few studies have evaluated the possible influence of the OHRQoL of mothers on that of their adolescent children. The aim of this study was to analyse the correlation between the OHRQoL of mothers and that of their adolescent children at their first oral examination. Methods: This retrospective pilot study was performed at the Dental Clinic of the University of Salamanca (Spain) between 2023 and 2025. The OHRQoL of 130 adolescent patients (from 11 to 14 years old) who visited the dentist for the first time was analysed. The mothers of these children were also interviewed to evaluate their OHRQoL; the adolescent patients completed the Spanish version of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ-Esp11–14) before their first dental consultation, and their mothers completed the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14). Results: The study population consisted of 130 mothers (mean age: 43.0 ± 2.66 years) and their respective adolescent children (mean age: 12.5 ± 1.3 years) (65 boys and 65 girls). Among the adolescent patients, the highest score was obtained for the social well-being dimension of the CPQ-Esp11–14 (25.01 ± 4.10), whereas the lowest was obtained for the oral symptoms dimension (10.88 ± 3.78). A higher score on the physical pain dimension of the OHRQoL for the mothers was related (p < 0.01) to higher scores on the emotional and social well-being dimensions of the CPQ-Esp11–14 for their children. Conclusions: Considering the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that the OHRQoL of mothers has some effect on that of their adolescent children when visiting a dentist for the first time.

1. Introduction

The quality of life (QoL) of a person is defined as the set of conditions that contribute to their social and personal well-being. QoL is important for evaluating people’s physical and mental health, as well as their oral health. The concept of oral health involves the ability to speak, chew, smile and express emotions confidently using facial expressions that do not show signs of pain or discomfort [1,2,3]. The term oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) is used in this context. Among other things, OHRQoL describes a person’s comfort when eating, sleeping or having social encounters, and it also involves an individual’s self-esteem and satisfaction with respect to their oral health [3]. OHRQoL provides information about the impact that oral conditions have on day-to-day activities from a patient’s point of view [4]. Evaluating the OHRQoL of patients can help dentists to identify the concerns described by patients and prioritise different options for dental treatment [5]. The OHRQoL of minors and their parents’/guardians’ perceptions of it can be influenced by different factors, such as age, sex, environmental factors, sociodemographic factors and oral conditions [6,7,8,9,10,11]. OHRQoL also quantifies the impact that facial aesthetics have on young patients [12]. Different questionnaires have been developed to quantify OHRQoL for both adult and paediatric patients. Many questionnaires have been validated in different regions or languages [3,13]. Among these questionnaires are the Child Perception Questionnaire (CPQ), the Child-Oral Impact Daily Performance (Child-OIDP), and the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS) [6,14,15,16].

Numerous studies in the scientific literature have evaluated OHRQoL in paediatric and adolescent patients [1,17,18,19,20]. However, few studies have analysed the correlation between the OHRQoL of parents and its possible influence on that of their adolescent children [21,22,23]. For example, some studies have reported a significant correlation between good OHRQoL among parents and a lower incidence of dental cavities among their children [24,25]. It has been concluded that parents or guardians of paediatric patients play a fundamental role in the prevention and management of oral health problems in their children. According to the World Health Organization, the stages of preadolescence and adolescence are transition periods that influence the health of individuals and their predisposition to disease during adulthood [26]. Previous studies that have evaluated this correlation have not focused on evaluating the OHRQoL of adolescent patients at their first visit to a dentist. Assessing the OHRQoL of patients—in this case, adolescent patients—before their first dental visit is important so that the professional can understand the impact and perception that adolescents have of their oral health, and its implications in their social environment.

The null hypothesis in this study was that mothers’ perceptions of their OHRQoL have no relationship with the OHRQoL reported by their adolescent children.

The primary goal of this study was to analyse the possible influence of the OHRQoL of mothers on that of their adolescent children before their first oral examination. The secondary goal was to quantify the OHRQoL of an adolescent population who had never previously undergone an oral examination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Salamanca (protocol number 1078 dated 27 November 2023). This study followed the directives established by the Helsinki Declaration for research with humans, as well as the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for carrying out observational studies [27]. The participants (both children and their mothers) were informed about the procedures of the study. Before inclusion in the study, informed consent was obtained from both the adolescent patients and their mothers.

2.2. Study Design

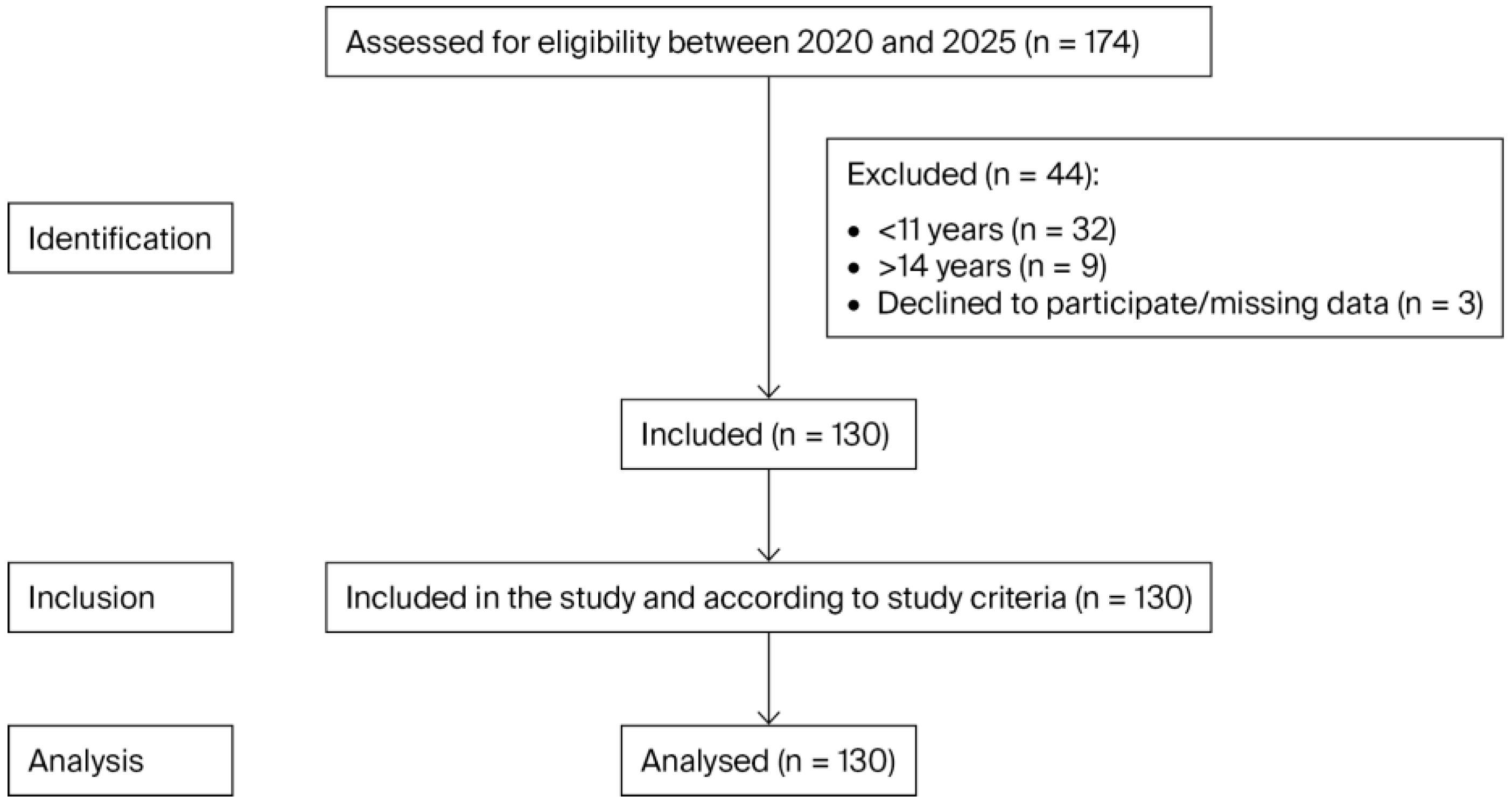

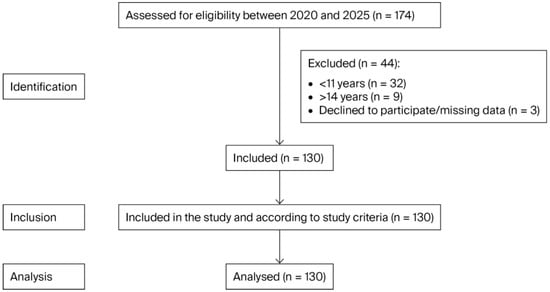

This cross-sectional observational study was carried out at the Dental Clinic of the University of Salamanca between December 2023 and July 2025. This study analysed the OHRQoL of a sample of 130 mothers and their adolescent children (aged between 11 and 14 years). Previous studies have also evaluated the age range of 11 to 14 years, considering this range as adolescent patients [23,28,29]. The total sample consisted of 130 mothers and 130 adolescents who were chosen consecutively from the patients who visited the Dental Clinic (Figure 1). The adolescent patients were patients who had never undergone a dental examination. Because it was a pilot study, only convenience sampling was performed. Moreover, due to the characteristics of this work (adolescent patients who had not previously attended a dental appointment) and the lack of previous studies, it was not considered necessary to calculate the required sample size in advance.

Figure 1.

STROBE flow chart.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for adolescent patients were as follows: (i) patients between the ages of 11 and 14 years; (ii) patients undergoing their first dental examination; (iii) patients who could visit the dentist with their mother. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients with a physical or mental disability; (ii) patients who had received dentofacial orthopaedic or orthodontic treatment; (iii) patients with systemic diseases; (iv) patients under continuous treatment with pharmaceuticals.

2.4. Procedures

The OHRQoL of the participants was analysed using the Spanish version of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire validated for a population between 11 and 14 years old (CPQ-Esp11–14) [30]. The Child Perceptions Questionnaire 11–14 comprises 37 items and encompasses four dimensions of OHRQoL: oral symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being and social well-being. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 points (0: never; 1: once or twice; 2: sometimes; 3: frequently; and 4: every day or almost every day); a higher score is indicative of worse OHRQoL [31].

The OHRQoL of the mothers was quantified using the Spanish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14). The OHIP-14 consists of 14 items that analyse the following seven domains of OHRQoL: functional limitations, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and disability. The items are scored using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = quite often, and 4 = very often) [32,33].

Both questionnaires (CPQ-Esp11–14 and OHIP-14) were given to the patients and their mothers at the same appointment. The OHIP-14 and CPQ-Esp11–14 were provided to study participants once before the adolescents’ oral examination. The questionnaires were provided by a single examiner who was a clinical practitioner of paediatric dentistry (A.C.). The adolescents completed the questionnaire prior to their oral examination and were separated from their mothers at the time. The adolescents and their mothers were given a few minutes to complete the questionnaires and were provided information by the examiner to help them.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28.0) was used to analyse the data. Descriptive analysis (mean, standard deviation median, and range) was performed for CPQ-Esp11–14 and OHIP-14 total scores and individual items. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rho) was used to analyse the correlation between the OHRQoL of mothers and that of their adolescent children. A p value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Participants

Data were collected from 130 adolescent patients aged between 11 and 14 years who were undergoing their first dental examination. Patients aged 13 years were the most common (n = 41; 31.5%), and patients aged 11 years were the least common (n = 28; 21.5%). The sex ratio of the participants was 1:1; in other words, the sample was composed of 50% (n = 65) male participants and 50% (n = 65) female participants. Consequently, no statistically significant differences in relation to age or the participants included in the study were observed. OHRQoL data were also collected from the patients’ mothers. The mothers had a mean age of 43.0 ± 2.66 years, ranging between 39 and 51 years (the median age was 42 years).

3.2. Analysis of the OHRQoL of the Adolescent Patients

The OHRQoL of the adolescent participants was evaluated using the CPQ-Esp11–14, which comprises four OHRQoL dimensions. The highest mean score was observed for the social well-being dimension (25.01 ± 4.10 points), in contrast to the oral symptoms dimension, which had the lowest mean score (10.88 ± 3.78 points) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Exploratory and descriptive analysis of the OHRQoL (CPQ-Esp11–14) of the adolescent patients (n = 130).

Considering the average values (means/medians) of the CPQ-Esp11–14 questionnaire, it can be concluded that the OHRQoL of the adolescent population studied falls within the middle range of the scoring scale.

3.3. Analysis of the OHRQoL of the Participants’ Mothers

When the OHRQoL of the participants’ mothers was analysed, the physical pain dimension of the OHIP-14 had a higher mean score (5.89 ± 1.40 points) than the disability dimension, which had a lower mean score (4.36 ± 1.52 points). With respect to the descriptive values, in practically all the dimensions of the OHIP-14, the means (means and medians) exceeded the central point (value of 4 points) on the scale of possible response values (0–8 points), which may indicate that the OHRQoL of the mothers tended to be more negative than positive. This was also observed for the total OHIP-14 score, where the mean score (38.05 ± 4.47) exceeded the central point (value of 28 points) on the scale of possible response values (0–56 points) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exploratory and descriptive analysis of the OHRQoL (OHIP-14) of the mothers (n = 130).

3.4. Correlation Between the OHRQoL of the Mothers and That of Their Children

Upon analysing the relationship between the OHRQoL of the mothers and that of their adolescent children, in general, no sufficiently intense relationships reached statistical significance. In general, there is not sufficient statistical evidence to confirm a relationship between the OHRQoL of mothers and that of their children on the basis of the sample analysed, except two cases. The physical pain dimension (OHIP-14) score of the mothers was correlated with the emotional well-being (CPQ-Esp11–14) (r = 0.24; p < 0.05) and social well-being (CPQ-Esp11–14) (r = 0.23; p < 0.05) scores of their children. In other words, the higher a mother’s score on the physical pain dimension, the greater the impact on her child’s scores in emotional and social well-being dimensions (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations between the OHRQoL (OHIP-14) of the mothers and that of their children (CPQ-Esp11–14) (n = 260).

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate the relationship between the OHRQoL of mothers and that of their adolescent children. In this study, only a significant relationship between the physical pain dimension score of the mothers (OHIP-14) and the emotional and social well-being dimension scores of the children (CPQ-Esp11–14) was observed. In this case, a higher maternal score on the physical pain dimension was related to a greater impact on the aforementioned OHRQoL dimensions of the children. The possible influence of the OHRQoL of the mothers on that of their adolescent children has still not been explored. Various tools have been developed to evaluate the OHRQoL of children. These questionnaires have been validated for different age ranges. The most commonly used questionnaires are the CPQ, the Child-OIDP, the Child Oral Health Impact Profile (COHIP) and the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS) [14,15,16,34,35]. There are two versions of the CPQ, one for children aged from 8 to 10 years old (CPQ8–10) and one for children aged from 11 to 14 years old (CPQ11–14) [34,35]. Various questionnaires have also been developed for the adult population to analyse OHRQoL, such as the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14), the Oral Health Impact Profile-49 (OHIP-49), the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), and the Oral Impacts on Daily Performance (OIDP) [36,37,38,39,40]. The Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) was used in this study because of its good psychometric properties [38,41]. The original version of the OHIP has 49 questions; because the original version takes longer to complete, in this study, the OHIP-14 was used. This instrument is considered more practical than the OHIP-49 and has also been shown to be a trustworthy tool with good reliability and validity [38,42]. The Spanish version of the CPQ11–14 (CPQ-Esp11–14) was used for the children in this study, and the OHIP-14 was used for the mothers. Both questionnaires have been widely used in previous studies [32,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Oral conditions affect several aspects of OHRQoL in the paediatric population, such as cavities [6,49], dental trauma [9], molar incisor hypomineralization [50,51], the need for orthodontic treatment [7], bruxism [52] and dental anxiety/pain experienced during dental treatment [10]. All the factors described above can impair the OHRQoL of paediatric patients, as can other sociodemographic factors [53]. One important, widely studied factor is the impact of malocclusion on the OHRQoL of the paediatric population. The severity of a malocclusion is associated with a greater negative impact on the OHRQoL of children [54,55,56,57]. In the preschool population, a relationship between the maternal level of dental anxiety and the OHRQoL of children has been confirmed. It has been concluded that high levels of dental anxiety among mothers influence their children and negatively impact their OHRQoL [58,59].

Yang et al. [21] evaluated the influence of different family factors and of parents’ OHRQoL on the OHRQoL of their children (aged between 3 and 5 years old). They concluded that parental age, the family’s income level, and the family’s place of residence were factors influencing the OHRQoL of their children. They also reported that the OHRQoL of parents (who completed the Oral Health Impact Profile-5 (OHIP-5)) was significantly related to the OHRQoL of their children (who completed the ECOHIS) [21].

In 2022, Velasco et al. [22] analysed the effects of different demographic and socioeconomic conditions of parents on the OHRQoL of their children. The study confirmed that the parents’ degree of knowledge about their children’s oral health status was not associated with an increase in the OHRQoL of their preschool-aged children (between 2 and 4 years old). The presence of cavities and a greater number of siblings negatively impacted the OHRQoL of the preschool population studied [22]. Similar results were also obtained by Sun et al. [23] in 2022. The authors concluded that the level of education of mothers positively influences the OHRQoL of their adolescent children (aged between 12 and 15 years old). The author used the CPQ11–14 [23], which was also used in this study. Similar studies, such as that conducted by Costa et al. [60] in 2017, researched the effect of depressive symptoms and anxiety on young mothers (aged 13–19 years old) with respect to the OHRQoL of their children (aged between 2 and 3 years old); this author used the ECOHIS questionnaire. Worse OHRQoL among children was associated with maternal symptoms of anxiety and depression [60].

A recent study by Khattab et al. [61] reported that there is no relationship between oral habits (primarily nail biting) among children (aged between 5 and 7 years old) and their OHRQoL from the point of view of their mothers.

In this study, a meaningful effect of sex on the OHRQoL of the adolescent participants was not observed. A review of the scientific literature revealed that the results of the various published studies are contradictory. The disparity regarding the possible effect on the OHRQoL of paediatric patients may be due to the age ranges of the samples analysed or the sample sizes and the specific inclusion/exclusion criteria of each study [8,62,63,64]. For example, Sun et al. [23], Thiruvenkadam et al. [65] and Kumar et al. [66] reported that boys had worse OHRQoL than girls. Nevertheless, other authors have reported better OHRQoL among boys than girls; this association can be explained by girls’ greater concern for their oral health [11,67,68,69,70]. In contrast to this study, the study by Sun et al. [23] revealed that adolescent males had higher scores on the oral symptoms dimension of the CPQ11–14 than adolescent females.

An analysis of the effect of age on the OHRQoL of the adolescent population revealed that there was a significant relationship (p < 0.05) only in the oral symptoms dimension of the CPQ-Esp11–14. In this dimension, the greater the age, the lower the score; in other words, there was a lower impact on OHRQoL. A significant effect of age was not reported for the remaining CPQ-Esp11–14 dimensions.

Interestingly, in this study, a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.01) was observed between the physical pain dimension score of the mothers and the emotional and social well-being dimension scores of their children. In other words, higher levels of physical pain among mothers were related to better well-being among their adolescent children, even though, a priori, this is contradictory.

A previous study by the authors of this study aimed to analyse the need for orthodontic treatment in adolescent patients with asthma and how their pathology could influence their OHRQoL. It was concluded that sex, as in this study, did not influence the OHRQoL score according to the CPQ-Esp11–14. The greatest score was obtained for the social well-being dimension (15.72 ± 1.91 points), and the lowest for the oral symptoms dimension (7.64 ± 1.39 points). These results are consistent with the results described in the present study. Similar results were also obtained when the relationships between age and the different OHRQoL dimension scores of the adolescents were analysed. In this case, it was observed that, in the oral symptoms and functional limitation dimensions, the greater the age, the lower the score obtained on the OHRQoL questionnaire, the results of which are similar to those obtained in this study [62].

Other studies affirmed that age does not significantly influence the OHRQoL of the paediatric population. It must be specified that this study focused on a very specific age range: the adolescent population aged between 11 and 14 years [8,11,64,71].

As described above, there are very few published studies that have evaluated the correlation between the OHRQoL of parents and that of their adolescent children.

4.1. Strengths of This Study

This study has several strengths that deserve to be highlighted. First, this is one of the first studies to evaluate the OHRQoL of adolescent patients at their first visit to a dentist. Notably, a limited number of studies have analysed the relationship between the OHRQoL of mothers and that of their adolescent children. The population analysed was homogeneous with respect to sex and age. Another strength of this study is that research such as that described here is important for analysing adolescent patients because this population group is in a transition period subject to major changes that can be prolonged into adulthood.

It is important to consider the family, specifically the mother, when planning and implementing interventions to promote and improve the dental health and OHRQoL of adolescent patients.

4.2. Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution because of several limitations. One of the limitations of this study was the sample size. As this was a pilot study, a consecutive sample of patients seeking dental care was analysed. Another limitation was that, in this study, patients from a single centre and health institution were analysed. It is possible that there is some effect of the geographic region in which patients reside on their OHRQoL. Multicentre studies and studies analysing changes in the OHRQoL of adolescent patients before and after dental treatment, including an analysis of dental anxiety in patients who are visiting the dentist for the first time and in their parents, should be performed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides new information about the impact of the first visit to a dentist on an adolescent population and the relationship between the OHRQoL of mothers and that of their underage children. In summary, considering the limitations of this study, the OHRQoL of mothers may be related to that of adolescent children who have not previously visited a dentist. In the population studied, sex did not influence the OHRQoL of adolescent patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., B.E., C.G.-P., K.V.R.-C. and J.F.-F.; methodology, A.C., B.E., C.G.-P., D.G., J.F.-F. and V.F.-V.; formal analysis, A.C., B.E., C.G.-P. and K.V.R.-C.; investigation, A.C., C.G.-P., D.G. and V.F.-V.; data curation, A.C., B.E., C.G.-P., D.G. and J.F.-F.; writing—review and editing, A.C., B.E., C.G.-P., J.F.-F. and V.F.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Bioethics Committee of the University of Salamanca approved this study: ethical approval date: 27 November 2023; protocol number: 1078.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained written informed consent from the patients to publish this paper, and we obtained consent from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Child-OIDP | Child-Oral Impact Daily Performance |

| COHIP | Child Oral Health Impact Profile |

| CPQ | Child Perception Questionnaire |

| ECOHIS | Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale |

| OHIP-14 | Oral Health Impact Profile-14 |

| OHRQoL | Oral health-related quality of life |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Salerno, C.; Campus, G.; Bontà, G.; Vilbi, G.; Conti, G.; Cagetti, M.G. Oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescent with autism spectrum disorders and neurotypical peers: A nested case-control questionnaire survey. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2025, 26, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, S.; Abdulla, A.M.; Andiesta, N.S.; Babar, M.G.; Pau, A. Role of family functioning and health-related quality of life in pre-school children with dental caries: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennadi, D.; Reddy, C.V. Oral health related quality of life. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2013, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, C.; Broder, H.; Wilson-Genderson, M. Assessing the impact of oral health on the life quality of children: Implications for research and practice. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2004, 32, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genderson, M.W.; Sischo, L.; Markowitz, K.; Fine, D.; Broder, H.L. An overview of children’s oral health-related quality of life assessment: From scale development to measuring outcomes. Caries Res. 2013, 47, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, P.P.G.; Jorge, R.C.; Marañón-Vásquez, G.A.; Fidalgo, T.; Maia, L.C.; Soviero, V.M. Impact of clinical consequences of pulp involvement due to caries on oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2025, 59, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridou, M.Z.; Herclides, A.; Lamnisos, D. Need for orthodontic treatment and oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents-a systematic review. Community Dent. Health 2024, 41, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Çarıkçıoğlu, B. Impact of parental dental anxiety on the oral health-related quality of life of preschool children without negative dental experience. Arch. Pediatr. 2022, 29, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.J.; Castilho, T.; Assaf, A.V.; Antunes, L.S.; Antunes, L.A.A. Impact of traumatic dental injury treatment on the oral health-related quality of life of children, adolescents, and their family: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent. Traumatol. 2021, 37, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barasuol, J.C.; Santos, P.S.; Moccelini, B.S.; Magno, M.B.; Bolan, M.; Martins-Júnior, P.A.; Maia, L.C.; Cardoso, M. Association between dental pain and oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovesan, C.; Antunes, J.L.; Guedes, R.S.; Ardenghi, T.M. Impact of socioeconomic and clinical factors on child oral health-related quality of life (COHRQoL). Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odersjö, M.L.; Johansson, L.; Robertson, A.; Sabel, N. Self-reported oral health-related quality of life and orofacial esthetics among young adults with treated dental trauma. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2025, 11, 70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, L.F.; Gilchrist, F.; Broder, H.L.; Clark, E.; Thomson, W.M. A comparison of three child OHRQoL measures. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goursand, D.; Paiva, S.M.; Zarzar, P.M.; Pordeus, I.A.; Grochowski, R.; Allison, P.J. Measuring parental-caregiver perceptions of child oral health-related quality of life: Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the P-CPQ. Braz. Dent. J. 2009, 20, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, G.D.; Reisine, S.T. The child oral health impact profile: Current status and future directions. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherunpong, S.; Tsakos, G.; Sheiham, A. Developing and evaluating an oral health-related quality of life index for children; the CHILD-OIDP. Community Dent. Health 2004, 21, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, L.A.A.; Ribeiro, L.G.; Silva, C.; Lopes, R.C.; Warol, F.; Meyfarth, S.; Antunes, L.S. The impact of traumatic dental injury on sensory perception and oral health-related quality of life of a child/adolescent before and after the treatment with aesthetic prosthesis: Case report. Int. J. Burn. Trauma 2021, 11, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Alade, O.; Ajoloko, E.; Dedeke, A.; Uti, O.; Sofola, O. Self-reported halitosis and oral health related quality of life in adolescent students from a suburban community in Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2020, 20, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, S.; Abacigil, F.; Adana, F. Oral health status and oral health related quality of life in adolescent workers. Clujul Med. 2018, 91, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, L.G.; Lages, E.M.; Abreu, M.H.; Pereira, L.J.; Paiva, S.M. Preadolescent’s oral health-related quality of life during the first month of fixed orthodontic appliance therapy. J. Orthod. 2013, 40, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Lai, G.; Wang, J. Oral health-related quality of life and associated factors among a sample from East China with severe early childhood caries: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, S.R.M.; Moriyama, C.M.; Bonecker, M.; Butini, L.; Abanto, J.; Antunes, J.L.F. Relationship between oral health literacy of caregivers and the oral health-related quality of life of children: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wong, H.M.; McGrath, C.P. Sociodemographic and clinical factors that influence oral health-related quality of life in adolescents: A cohort study. Community Dent. Health 2022, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, G.R.; Bonotto, D.V.; Ferreira, F.M.; Menezes, J.; Fraiz, F.C. Caregiver’s oral health literacy is associated with prevalence of untreated dental caries in preschool children. Cien. Saude. Colet. 2019, 24, 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, R.; Esfahani, E.N.; Kharazifard, M.J. Relationship of oral health literacy with dental caries and oral health behavior of children and their parents. J. Dent. 2018, 15, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.B.; de Carvalho Padilha, P.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C.; Ulloa, N.; Brun, P.; Acevedo-Correa, D.; Arantes Ferreira Peres, W.; Martorell, M.; Aires, M.T.; de Oliveira Cardoso, L.; et al. COVID-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, R.A. Standards of reporting: The CONSORT, QUORUM, and STROBE guidelines. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 1393–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommi, S.; Leinonen, J.; Pussinen, P.; Furuholm, J.; Kolho, K.L.; Viljakainen, H. Burden of oral diseases predicts development of excess weight in early adolescence: A 2-year longitudinal study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 4093–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, É.T.B.; Dutra, L.D.C.; Gomes, M.C.; Paiva, S.M.; de Abreu, M.H.N.G.; Ferreira, F.M.; Granville-Garcia, A.F. The impact of oral health literacy and family cohesion on dental caries in early adolescence. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Díaz, F.D.C.; Page, L.A.F.; Thomson, N.M.; Borges-Yáñez, S.A. Differential item functioning of the Spanish version of the child perceptions questionnaire. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2013, 4, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Martínez, A.M.; Hernández-Elizondo, R.T.; Núñez-Rocha, G.M.; Peña, E.G.R. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the short-form child perceptions questionnaire for 11-14-year-olds for assessing oral health needs of children. J. Public Health Dent. 2014, 74, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andiappan, M.; Gao, W.; Bernabé, E.; Kandala, N.B.; Donaldson, A.N. Malocclusion, orthodontic treatment, and the oral health impact profile (OHIP-14): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Martín, J.; Bravo-Pérez, M.; Albaladejo-Martínez, A.; Hernández-Martín, L.A.; Rosel-Gallardo, E.M. Validation the oral health impact profile (OHIP-14sp) for adults in Spain. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Locker, D.; Jokovic, A.; Tompson, B.; Prakash, P. Is the child perceptions questionnaire for 11–14 year olds sensitive to clinical and self-perceived variations in orthodontic status? Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokovic, A.; Locker, D.; Tompson, B.; Guyatt, G. Questionnaire for measuring oral health-related quality of life in eight- to ten-year-old children. Pediatr. Dent. 2004, 26, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oszlánszky, J.; Gulácsi, L.; Péntek, M.; Hermann, P.; Zrubka, Z. Psychometric properties of general oral health assessment index across ages: COSMIN systematic review. Value Health 2024, 27, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, L.M.; Scalco, G.P.; Abegg, C.; Celeste, R.K. Factor analysis of two versions of the oral impacts on daily performance scale. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 124, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.; López, J.F.; Vicente, M.P.; Galindo, M.P.; Albaladejo, A.; Bravo, M. Comparative validity of the OIDP and OHIP-14 in describing the impact of oral health on quality of life in a cross-sectional study performed in Spanish adults. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2011, 16, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, J.M.; Verrips, G.H.; Hoogstraten, J. Instrument-order effects: Using the oral health impact profile 49 and the short form 12. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D.; Spencer, A.J. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Health 1994, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Izzetti, R.; Carli, E.; Gennai, S.; Graziani, F.; Nisi, M. OHIP-14 scores in patients with sjögren’s syndrome compared to sicca syndrome: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 9277636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locker, D.; Allen, F. What do measures of ‘oral health-related quality of life’ measure? Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.G.; Antunes, L.S.; Küchler, E.C.; Baratto-Filho, F.; Kirschneck, C.; Guimarães, L.S.; Antunes, L.A. Impact of malocclusion treatments on oral health-related quality of life: An overview of systematic reviews. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 907–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, Z.; Alghamdi, A.M.S.; Haydarah, N.K.B.; Balateef, A.A.; Alamoudi, A.A.; Abumismar, M.A.; Shivakumar, S.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. Impact of temporomandibular disorders on oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Seoane, M.; Reichenheim, M.E.; Tsakos, G.; Celeste, R.K. Adult oral health-related quality of life instruments: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2022, 50, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefani, A.; Bruno, G.; Irlandese, G.; Barone, M.; Costa, G.; Gracco, A. Oral health-related quality of life in children using the child perception questionnaire CPQ11-14: A review. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaror, C.; Pardo, Y.; Espinoza-Espinoza, G.; Pont, À.; Muñoz-Millán, P.; Martínez-Zapata, M.J.; Vilagut, G.; Forero, C.G.; Garin, O.; Alonso, J.; et al. Assessing oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review and standardized comparison of available instruments. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wong, H.M.; McGrath, C.P.J. Association between the severity of malocclusion, assessed by occlusal indices, and oral health related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2018, 16, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, Â.D.; Rodrigues, C.D.S.; Rocha, R.D.O.; Soares, F.Z.M.; Braga, M.M.; Lenzi, T.L. Is caries associated with negative impact on oral health-related quality of life of pre-school children? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 40, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.R.; Cortés, L.L.; Rojas, M.J.M.; López, A.L.S.M.; Vera, K.G.R. Effect of molar incisor hypomineralization on oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Rev. Cient. Odontol. 2023, 10, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Jawdekar, A.M.; Kamath, S.; Kale, S.; Mistry, L. Assessment of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in children with molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH)—A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Indian. Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2022, 40, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.A.; Azevedo, C.B.; Chami, V.O.; Solano, M.P.; Lenzi, T.L. Sleep bruxism and oral health-related quality of life in children: A systematic review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 30, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malele-Kolisa, Y.; Yengopal, V.; Igumbor, J.; Nqcobo, C.B.; Ralephenya, T.R.D. Systematic review of factors influencing oral health-related quality of life in children in Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlJameel, A.H.; Almoammar, K.; Alfawaz, N.F.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Alotaibi, G.A.; Albarakati, S.F. Can malocclusion among children impact their oral health-related quality of life? parents’ perspective. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaradoss, J.K.; Geevarghese, A.; Alsaadi, W.; Alemam, H.; Alghaihab, A.; Almutairi, A.S.; Almthen, A. The impact of malocclusion on the oral health related quality of life of 11-14-year-old children. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.C.; Paiva, S.M.; Viegas, C.M.; Scarpelli, A.C.; Ferreira, F.M.; Pordeus, I.A. Impact of malocclusion on oral health-related quality of life among Brazilian preschool children: A population-based study. Braz. Dent. J. 2013, 24, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Benson, P.; O’Brien, C.; Marshman, Z. Agreement between mothers and children with malocclusion in rating children’s oral health-related quality of life. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2010, 137, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esa, R.; Jamaludin, M.; Yusof, Z.Y.M. Impact of maternal and child dental anxiety on oral health-related quality of life of 5-6-year-old preschool children. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettems, M.L.; Ardenghi, T.M.; Romano, A.R.; Demarco, F.F.; Torriani, D.D. Influence of maternal dental anxiety on oral health-related quality of life of preschool children. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.D.S.; Azevedo, M.S.; Ardenghi, T.M.; Pinheiro, R.T.; Demarco, F.F.; Goettems, M.L. Do maternal depression and anxiety influence children’s oral health-related quality of life? Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.M.A.; Abd-Elsabour, M.A.A.; Omar, O.M. Parent-perceived oral habits among a group of school children: Prevalence and predictors. BDJ Open 2024, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, A.; Mihit, F.; Curto, D.; Albaladejo, A. Assessment of orthodontic treatment need and oral health-related quality of life in asthmatic children aged 11 to 14 years old: A cross-sectional study. Children 2023, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asokan, S.; Pr, G.P.; Mathiazhagan, T.; Viswanath, S. Association between intelligence quotient dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in children: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhée, T.; Poncelet, J.; Cheikh-Ali, S.; Bottenberg, P. Prevalence, caries, dental anxiety and quality of life in children with MIH in Brussels, Belgium. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvenkadam, G.; Asokan, S.; John, J.B.; Priya, P.R.G.; Prathiba, J. Oral health-related quality of life of children seeking orthodontic treatment based on child oral health impact profile: A cross-sectional study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2015, 6, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bhargav, P.; Patel, A.; Bhati, M.; Balasubramanyam, G.; Duraiswamy, P.; Kulkarni, S. Does dental anxiety influence oral health-related quality of life? Observations from a cross-sectional study among adults in Udaipur district, India. J. Oral Sci. 2009, 51, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wong, H.M.; McGrath, C.P.J. The factors that influence oral health-related quality of life in young adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, T.S.; Tureli, M.C.; Gavião, M.B. Validity and reliability of the child perceptions questionnaires applied in Brazilian children. BMC Oral Health 2009, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locker, D. Disparities in oral health-related quality of life in a population of Canadian children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, L.F.; Thomson, W.M.; Jokovic, A.; Locker, D. Validation of the child perceptions questionnaire (CPQ 11-14). J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondani, B.; Knorst, J.K.; Ardenghi, T.M.; Mendes, F.M. Pathway analysis between dental caries and oral health-related quality of life in the transition from childhood to adolescence: A 10-year cohort study. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).