Abstract

Background/Objectives: Caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental and chronic health conditions require health literacy (HL) skills for the long-term management of these conditions. The aim of this rapid review was to investigate the efficacy of HL interventions for these caregivers. Methods: Five databases (Cochrane Central, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO) were searched. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported the efficacy of any intervention aimed at improving the HL of caregivers of individuals with a neurodevelopmental disorder or chronic condition and assessed caregiver HL. All original intervention study designs were eligible, as were systematic reviews. Studies had to be published in English since 2000; grey literature was excluded. The review was registered before commencement with PROSPERO (CRD42023471833). Results: There were 3389 unique records, of which 28 papers (reporting 26 studies) were included. In these studies, 2232 caregivers received interventions through a wide range of media (online, group, written materials, one-to-one, video, phone, and text messages). Research designs were classified as Levels I (n = 8), II (n = 5), III (n = 2), and IV (n = 11), and the quality of evidence ranged from high to very low. Half (n = 7) of the trials with moderate to high evidence levels reported significant between-group differences in caregiver HL outcomes and/or individuals’ health-related outcomes. Effective interventions occurred across a wide range of conditions, ages, and carer education levels and using a diversity of intervention media. Conclusions: HL interventions for caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental and chronic conditions can improve health-related outcomes and caregivers’ HL. Longer and more intensive HL programs may be more likely to be effective, but attention must be paid to participant retention.

1. Introduction

Neurodevelopmental conditions are “multifaceted conditions characterized by impairments in cognition, communication, behaviour and/or motor skills resulting from abnormal brain development” [1]. They are usually evident in very early childhood and include global developmental delay, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as well learning, communication, and motor disorders [2]. A chronic condition is one expected to last at least 6 months, with poor prognosis, having consequences affecting quality of life, with a pattern of recurrence or deterioration [3]. Children with chronic health conditions (e.g., asthma, chronic otitis media, and epilepsy) are developmentally vulnerable in social, emotional, language, cognitive, and physical domains [4].

Children with neurodevelopmental and chronic health conditions are disproportionately high users of healthcare [5,6]. Their conditions usually persist many years and may affect multiple body systems [7]. Their caregivers often have very complex roles, including monitoring adherence to treatments, responding to flare-ups, navigating services, and communicating with healthcare professionals [8,9,10]. These tasks require many skills, including health literacy (HL).

The European Health Literacy Consortium defined HL as entailing “people’s knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life” [11] (p. 3). Responsibility for accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information does not rest solely with the individual with a chronic condition but is “distributed” among family members, friends, colleagues, and also community support groups [12]. Therefore, attempts to support these individuals through their healthcare journeys need to target their caregivers as well as themselves. Improving caregiver HL is one way to do this. For the purpose of this review, caregivers are defined as those who provide informal, unpaid support or care in the community (e.g., parents, other family members/relatives, and friends) [13]. Low caregiver HL is sometimes associated with poorer health outcomes, poorer quality of life for the individual and family, and difficulty navigating and communicating with healthcare services [14,15,16,17,18].

The good news is that HL is potentially modifiable: some HL interventions have improved HL, including knowledge and health-related behaviours [16,19]. Based on a systematic review of interventions for caregivers of adults with disabilities and chronic conditions, Yuen et al. suggested tentatively (as evidence is limited) that interventions may be more effective if they tailor information, used mixed modalities, engage a health provider, and use multiple sessions [20]. However, Yuen and colleagues excluded interventions for caregivers of children and adolescents. The present review included interventions for caregivers of individuals of all ages. Its aim was to investigate how HL interventions for caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental and chronic conditions affect the caregivers’ HL and the individuals’ health-related outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This was a rapid review, namely, “a type of knowledge synthesis in which systematic review methods are streamlined and processes are accelerated to complete the review more quickly” [21], following Cochrane Rapid Review Guidelines [21]. Reporting is in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews [22]. The review was registered before commencement (12 October 2023) with PROSPERO (CRD42023471833) and amended after data extraction (29 February 2024). The amendment did not necessitate another search.

2.2. Search Strategy

Cochrane Central, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were searched. Reference lists of selected articles were also scanned. Two authors (T.N. and J.K.) developed search terms, which all authors reviewed. Search terms relating to HL were from prior systematic reviews [23,24,25] and the European Health Literacy Consortium’s definition of HL [11]. A chronic condition was defined as one expected to last at least 6 months, with poor prognosis, having consequences affecting quality of life, with a pattern of recurrence or deterioration [3]. The search terms relating to chronic conditions were from this definition and search terms in prior reviews. The full search terms are in online Supplemental Table S1. The search was conducted 12 October 2023 (Table S1).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies meeting the following criteria were included:

- The sample included caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental or chronic conditions.

- The study reported the efficacy of any intervention aimed at improving the HL of these caregivers. HL included accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information [11]. Interventions could be delivered in any setting, including clinical, community, educational, or home-based settings or online.

- There was any or no comparison.

- The primary outcome was HL. Secondary outcomes included individuals’ health indicators, healthcare service use, economic costs of healthcare, and health-related adverse events.

- Study designs included systematic reviews, randomized or non-randomized controlled trials, or any other intervention study design. Data could be quantitative, qualitative, or mixed.

- Studies were published in English since 2000, and the full text was available. Grey literature was excluded, including books, dissertations, reports, conference papers, media (e.g., newspaper), letters to editors, editorials, blogs, podcasts, and newsletters.

2.4. Study Selection

Articles were imported into EndNote (version x9, Clarivate Analytics. Philadelphia PA) and duplicates removed using the “find duplicates” function and review by authors. Articles were imported into Rayyan (a collaboration platform designed for systematic reviews [26]) for screening and further de-duplication.

An abstract review form was developed, based on the selection criteria and piloted with 40 abstracts by five reviewers (S.H., R.S., J.K., O.L., and A.M.B.). Two reviewers (T.N. and J.K.) independently screened 30% of the titles and abstracts. Irreconcilable differences were resolved by a third reviewer (A.M.B). One reviewer (T.N.) screened the remaining titles and abstracts and a second reviewer (A.M.B) reviewed those excluded. One reviewer (T.N.) screened all full-text articles and a second reviewer (A.M.B) reviewed excluded articles.

2.5. Data Extraction

A data extraction form was adapted from the Cochrane data extraction template, and two reviewers (T.N. and A.M.B.) independently pilot-tested it on three studies. The final form included the following fields: reference, country, participants (number, characteristics, diagnoses), study design, level of evidence (based on the AACPDM classification [27]), setting, intervention, comparison, outcomes (measures and time points), aspects of HL assessed (access, understanding, appraisal, use of information), result for each outcome, adverse events, and comments. One reviewer (T.N.) extracted data for the remaining studies and a second (A.M.B.) checked data for correctness and completeness. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The corresponding author of one study was asked for further information, but none was received.

2.6. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

One reviewer (T.N.) assessed each paper using the quantitative randomized controlled and non-randomized scales of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 [28], with full verification by a second reviewer (A.M.B.), any differences being resolved by discussion. Each scale has seven quality assessment criteria assessed using three response options (yes, no, and cannot tell).

2.7. Data Synthesis

Findings from included papers were synthesized in tables and descriptive narrative summaries. No meta-analysis was carried out, because studies had different interventions and outcome measures. HL outcomes were classified (following the definition [11]) as accessing, understanding, appraising, and/or applying health information by two raters (T.N. and A.M.B). Recommendations for practice were based on the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) system [29] and the evidence alert traffic light system [30]. In accordance with the evidence-informed recommendations for rapid reviews [21], two stakeholders (parents of children with neurodevelopmental conditions) were included in the team (SH, RS).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

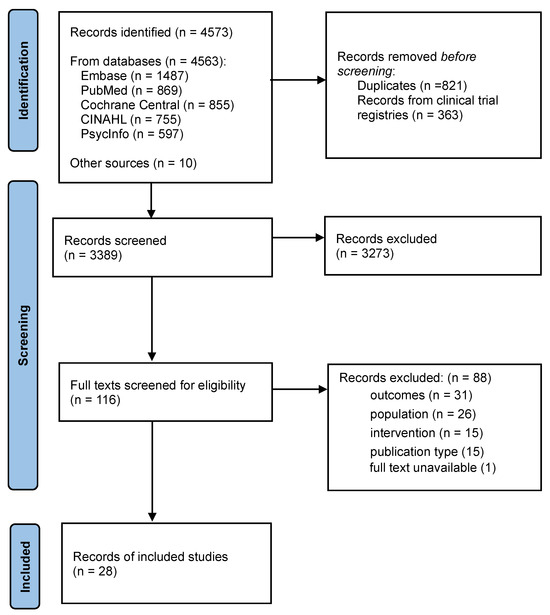

There were 3389 unique records, of which 116 full texts were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). Included in the review were 28 papers, reporting 26 studies (2 studies appearing in 2 papers each [31,32,33,34]).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of literature searches and study selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Of the 26 studies, 11 were from the USA, 2 each from Australia, China, the Netherlands, and Spain, and 1 each from Aotearoa New Zealand, Canada, Germany, Iran, Italy, Türkiye, and the UK (Table 1). There were 13 randomized controlled trials (8 at Level I [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], 5 at Level II [31,32,42,43,44,45]), 2 non-randomized controlled trials (Level III) [46,47,48], and 11 Level IV studies (10 one-group pretest–post-test designs [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] and one case study [59]).

A total of 2979 participants commenced and 2232 completed the study interventions and assessments (ranging across studies: 3–306 who commenced, 3–253 who completed). Four studies targeted caregivers of adults (aged > 21 years) [37,38,49,51]; the remainder (n = 22) targeted caregivers of children and adolescents. Two studies targeted caregivers with only primary or secondary school education [38,42]; in three studies, most caregivers had tertiary education [54,57,58]; and eight studies included caregivers with education levels ranging from primary school to university [35,36,37,40,41,43,50,56]. The remaining 13 studies did not describe caregivers’ education levels.

In five studies, individuals had neurodevelopmental conditions: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [56,57], Duchenne muscular dystrophy [59], moderate to severe disability (including autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and cerebral palsy) [41], and developmental concerns [42]. In 18 studies, they had chronic conditions: asthma [31,32,33,34,40,43], food allergies [52,55,58], eczema [35,44], cancers [37,49], epilepsy [45], hypertension [38], kidney disease [36], mood and anxiety disorders [48], obesity [39], oesophageal atresia [46,47], and type I diabetes [53]. The remaining five studies had mixed samples, probably including some with neurodevelopmental conditions: children needing nutritional support [50], adults with complex care needs [51], and children with nonspecific medical conditions or disabilities [54]. As it was impossible to separate individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions from those with chronic health conditions, they were pooled. Only three studies [42,48,50] targeted caregivers of recently diagnosed individuals; the other studies targeted caregivers of individuals, all or most of whom had been diagnosed months or years earlier.

The interventions used various media: online (n = 9) [35,36,45,46,47,49,52,53,56,57], group sessions (n = 8) [33,34,38,39,46,47,48,54,55,58], written materials (n = 6) [31,32,33,34,40,41,50,51], one-to-one sessions (n = 4) [31,32,35,51,59], video (n = 2) [42,43], phone calls (n = 2) [37,51], and text messages (n = 2) [42,44]. Five studies used multiple media [31,32,35,42,46,47,51], and one offered the intervention in two alternative media [33,34]. Caregivers helped develop at least eight of the interventions [40,42,49,52,53,54,55,57].

In the 15 studies with a control group, the comparison was no intervention or usual care (n = 8) [31,32,35,36,41,42,44,45,46,47] or an alternative intervention (n = 7) [33,34,37,38,39,40,43,48].

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Study, Country | Level of Evidence, Research Design | Participant and Child Characteristics and n Who Completed | Medium of Intervention | Intervention | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials (Levels I-II) | |||||

| Horner 2004, 2006 [31,32] USA | II Cluster RCT 3 | 60 commenced; 44 completed. Parent–child (7–11 y) dyads with asthma. | Booklet + in-person home visits | 9 classes for chn over 1 m + booklet for parents on asthma mgt, pathophysiology, meds, qs for physician, and asthma mgt plan + home visits. | No intervention |

| Macy et al., 2011 [43] USA | II RCT | 126 commenced; 86 completed (I gp: n = 42; C gp: n = 44). Parents of chn (4–12 y) presenting to ED with prior asthma Dx or Hx of wheeze. Educ level: <2° school to college. | Video | 20 min video shown to parents in ED, incl asthma facts, meds, and pt skills. | Written educ materials with same content as video |

| Kintner et al., 2015a 2015b [33,34] USA | I RCT | 205 caregiver–child (9–12 y) dyads (I gp: n = 117; C gp: n = 88) with asthma commenced; 136 completed all Ax at 24 m f-u. | In-person gp presentation or booklet | 10 × 50 min asthma educ lessons for chn on asthma + for caregivers either 1 × 90 min info-sharing session or booklet. | 6 × 50 min lessons for chn + bullet-pointed handouts for caregivers |

| Yin et al., 2017 [40] USA | I RCT | 217 parents of chn (2-12 y) with asthma (I gp: n = 109, C gp: n = 108). Educ level: < high school grad (24%) to ≥college (59%). | Action plan | Low-literacy, plain language, pictogram-, and photograph-based asthma action plan. | Standard action plan |

| Jimenez et al., 2017 [42] USA | II RCT | 64 parent–child (>3 y) dyads, (I gp: n = 31; C gp: n = 33) referred to EI for dev concerns. Max parent educ level: high school (85%). | Video + SMS | 3 min video on child dev and EI pgm + 1 SMS sent 7–14 days later. | Standard care + publicly available handout on EI |

| Singer et al., 2018 [44] USA | II RCT | 41 commenced; 30 completed. Parents of chn (0–3 y) with eczema (I gp: n = 14, C gp: n = 16). | SMS | Text messages with info on eczema sent daily for 42 d or until f-u appointment. | Usual care |

| Geense et al., 2018 [36] Netherlands | I RCT | 146 commenced; 51 completed. Parents of chn with chronic kidney disease (I gp: n = 68; C gp: n = 65); 50% with high educ level. | Online | 6 m access to 1) website with info/videos about kidney diseases, treatment, diet, and finance + chat room to message other parents and health care professionals; 2) web-based training platform (4 modules). | Usual care |

| Heckel et al., 2018 [37] Australia | I RCT | 216 cancer pt–caregiver dyads commenced (n=108 per gp); 158 completed (I gp: n = 81; C gp: n = 77). Pts’ mean age 59 y; 88% solid cancers; receiving chemo (38%), radiotherapy (33%), or combination (29%); caregivers mean age 56 y; usually spouse (79%); educ level: 1° school to uni. | Phone | 3 phone calls over 4 months from specialist oncology nurses, to discuss: psychological distress, health literacy, physical health, family support, financial burden, and practical difficulties. | 3 phone calls from research personnel, supplying info line number to self-initiate contact. |

| Zhou et al., 2020 [41] China | I RCT | 306 parent–child (2–6 y) dyads (I gp, n = 156, C gp, n = 150) with mod–severe disability (ASD, dev delay, CP). Educ levels: <9 y (14%) to ≥14 y (57%). N = 253 completed, but ITT analysis on n = 306. | Educ materials | Structured package of oral health educ materials on brushing, tooth-friendly eating, and dental visits for parents + social stories for chn. | Standard leaflets issued by the Health Department. |

| Tutar Güven et al., 2020 [41] Türkiye | II RCT | 70 child–parent dyads commenced; 69 completed (I gp: n = 35; C gp: n = 34). Chn (9–18 y) with epilepsy and no disability or other chronic disease. | Online | 12 w access to web-based epilepsy educ pgm with info about epilepsy, Tx, and 1st aid. | Usual care |

| Cheng et al., 2021 [35] China | I RCT | 136 parent–child dyads (n = 68 per gp). Chn (3–12 y) with mod or severe eczema. 133 completed. ITT analysis. Educ level: 56% post-secondary. | 1-to-1 in-person educ session + online group | Parental eczema educ incl 30 min nurse-delivered sessions + 3 m online group sharing + standard eczema treatments. | Standard eczema treatments |

| Noroozi et al., 2022 [38] Iran | I Cluster RCT | 200 pts (M = 61 y; 77% F; 77% homemakers) with hypertension + mother (food preparers) of family (100 per gp). Pt educ level: 95% 1° school. (N of mothers not specified; unclear how many pts were also mothers.) | In-person gp | 2 d info workshop on hypertension and diet + ongoing routine educ from healthcare wkrs. | 2 d info workshop on parenting styles + ongoing routine educ from healthcare wkrs. |

| Te’o et al., 2022 [39] Aotearoa New Zealand | I RCT | Parent–child (4–16 y) dyads with overweight/obese chn. 161 commenced; 145 at 12 m; 120 at 24 m; 80 at 60 m. | In-person family gp sessions | 12-month multidisciplinary pgm of weekly physical activity or nutrition sessions + 6-monthly home-based Ax and advice. | 6-monthly home-based Ax and advice. |

| Non-randomized controlled trials (Level III) | |||||

| Sapru et al., 2016 [48] Canada | III Non-RCT | 19 commenced; 16 completed. Caregivers of chn (6–12 y, M = 8 y) referred with mood and anxiety disorders (in-person: n = 10; online gp: n = 6). | In-person gp sessions | 3 × PPT presentations with same content as in-person sessions, emailed to family over 3 w | 3 × 1 h in-person gp sessions over 3w about Tx options, interpersonal and communication skills, and problem-solving and reflect + gp social interactions |

| Dingemann et al., 2017 [46,47] Germany | III Non-RCT | 29 adolescent pts (14–21 y) with oesophageal atresia (I gp: n = 10; C gp: n = 19) + 25 parents (I gp: n = 7; C gp: n = 18). F-u data for 22–23 adolescents and 9–23 parents (n varying across subscales). | In-person group workshops + online support. | 2 d pgm incl 12 × 45 min modules with info on changes on turning 18; changing doctor; healthcare system; career; social networks; medical issues; coping + parent-specific component: social legislation + medical and psychological issues. | Usual care |

| One-group and case series designs (Level IV) | |||||

| LeBovidge et al., 2008 [58] USA | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 59 parents of 61 chn (5–7 y) with food allergies commenced. Educ level: 87% college or graduate degree. 48 completed f-u. | In-person group | 3.5 h workshop to promote parents’ coping and reduce stress and burdens in food allergy mgt. | None |

| Arikian et al., 2010 [59] USA | IV Case series | Families of 3 non-ambulatory obese boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, aged 8, 13, 13 y. | 1-to-1 in-person meetings | 20 × sessions and written materials on childhood obesity, weight loss, and prevention, over 6 months. | None |

| Ossebaard et al., 2010 [57] Netherlands | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 12 parents of chn (M = 8 y) with ADHD (0.2% of 7500 who visited site and completed q’aires before and after using site). Educ level: most > average. | Online | Web-based decision aid on ADHD | None |

| Ryan et al., 2015 [56] UK | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 91 caregivers of chn (4–18 y, M = 10 y) with ADHD or suspected ADHD (172 commenced and 158 completed, but only 91 accessed website). Caregiver educ levels: <2° school to postgraduate. | Online | Info-based website on ADHD mgt | None |

| Contreras-Porta et al., 2016 [55] Spain | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 184 commenced; 174 completed. Parents of chn (M = 4.9 y) with food allergy. | In-person group workshops | 2 × 2 h workshops on food allergies delivered by physicians and expert parents, incl 7 educ videos. (In-person version of intervention reported below [52].) | None |

| Armstrong-Heimsoth et al., 2017 [54] USA | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 30 mothers and staff-parent advocates of individuals with nonspecific medical conditions or disabilities. Complete data from 24–28 (n varying across subscales). Educ level: some college. | In-person group workshop | 1 × 60 min session about how and where to look for reliable health information online, how to form a searchable question, how to share their findings with their healthcare providers, and how to use information delivery shortcuts such as email alerts. | None |

| Holtz et al., 2018 [53] USA | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 50 commenced; 46 completed. Parents of chn (5–18 y) with T1D. | Online | 8 w access to website with info on navigating life events, dev milestones with T1D, links to websites/resources + closed Facebook parent gp. | None |

| Ruiz-Baqués et al., 2018 [52] Spain | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 207 commenced; 130 completed. Caregivers of chn (M = 5 y) with food allergies. | Online | 2 w access to a 5 h online educ pgm on food allergy mgt. (Online version of intervention reported above [55].) | None |

| Guida et al., 2019 [51] Italy | IV One-group pretest–post-test | 47 caregivers (sons, spouses, siblings, parents, 83% F, aged 30 to 80) of adults with complex care needs. | 1-to-1 in-person + phone + booklet | 2 motivational sessions in 1 m + handbook incl managing info and communication, navigating healthcare settings and personal wellbeing. | None |

| Buchhorn-White et al., 2020 [50] Australia | IV One-group post-test only | 30 commenced, 18 completed. Parents of chn needing nutritional support (most [78%] enteral nutrition or NG tube) during hospital stay (excl ICU). Educ level: Y10 to university degree. | Decision aid booklet | During their children’s hospital stay, parents read decision aid booklet on the risks and benefits of oral nutrition support, nasogastric and gastrostomy tube feeding and total parenteral nutrition. | None |

| Merz et al., 2022 [49] USA | IV One-group pretest–post-test for caregivers; (II RCT for pts) | 10 caregivers + 50 pts commenced; 8 caregivers + 45 pts completed. Pts (50–64 y) with solid cancers, stages 3 and 4. Pts randomized to I and C gps, but all caregivers in I gp. (Only caregivers are considered in this review.) | Mobile app | 12 w access to app with supportive care services and resource info | None for caregivers |

Abbreviations: 1°, primary; 2°, secondary; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; Ax, assessment; C gp, control group; chn, children; CP, cerebral palsy; d, day; dev, developmental; Dx, diagnosis; ED, emergency department; educ, education; EI, early intervention; excl, excluding; F, female; f-u, follow-up; gp, group; h, hour; Hx, history; I gp, intervention group; incl, including; info, information; ITT, intention to treat; M, mean; max, maximum; meds, medications; mgt, management; min, minutes; m, month; mod, moderate; n, number; pgm, program; pt, patient; q’aire, questionnaire; qs, questions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; T1D, Type 1 diabetes; Tx, treatment; w, week; wkrs, workers; y, years.

3.3. Risk of Bias Within Studies

Using the MMAT for quantitative randomized controlled trials (Level I–II studies), one study [31,32] did not meet the screening criteria (due to insufficient reporting of inclusion criteria, intervention, group sizes, standard deviations, and significance levels). The remaining 12 studies ranged in quality from 20% to 100% (Table 2). Nearly all these 12 studies’ groups were comparable at baseline (n = 11), and participants adhered to the intervention (n = 10). About half performed randomization appropriately (n = 6) and had complete outcome data (n = 7) and blinded assessors (n = 6).

Table 2.

Quality of studies according to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Using the MMAT for quantitative non-randomized trials (Level III–IV studies), one study [57] did not meet the screening criteria (due to lack of an explicit research question and lack of data from 99% people who visited the website). The remaining 12 studies ranged in quality from 20% to 80%. Most of these 12 studies had complete outcome data (n = 9) and administered the intervention as intended (n = 10), with half using appropriate measures (n = 6); however, confounders were generally not accounted for (n = 1), and in none of the studies were participants shown to be representative of the population (n = 0).

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

Table 3 shows the studies’ outcomes. Caregiver-related outcomes included knowledge [38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,52,53,55,56,57] (n = 15), management of the condition [31,32,33,34,35,36,38,40,41,45,51,57,59] (n = 11), self-efficacy or self-perceived understanding, competence, or control [35,36,37,43,50,51,53,54,58] (n = 9), HL [37,45,52] (n = 3), use of services [42,49] (n = 2), attitudes [38,42] (n = 2), and communication with healthcare professionals [36,52] (n = 2). Secondary outcomes related to the individual with the health condition; these were health indicators [35,38,41,43,44,59] (n = 6) and the quality of life or health-related quality of life of the person with a chronic condition [36,46,47,59] (n = 3). HL outcomes were classified, according to the definition of HL [11], into accessing (n =7), understanding (n = 22), appraising (n = 2), or using (n = 18) information.

Table 3.

Results of individual studies.

Seven of the 13 randomized controlled trials reported significant between-group effects. The conclusions from these trials are summarized in Table 4. Of the remaining six randomized controlled trials, two studies reported between-group differences on only two items in purpose-designed questionnaires, with no significant effects for any other items [33,34,42]. No other trials reported significant between-group effects.

Table 4.

HL interventions with moderate-to-high strength of evidence of between-group effects.

Two non-randomized controlled trials reported no significant group differences [46,47,48].

Of the 13 evidence level IV studies, 7 one-group pretest–post-test designs reported significant improvements in caregiver knowledge and self-efficacy after intervention, but the quality of evidence was low (Evidence level IV, 20–40% on MMAT) [50,52,53,54,55,56,58]. A level IV case series with three children (60% on MMAT) also reported improvements in caregiver management and child quality of life following intervention [59].

3.5. Grading of Evidence and Recommendations

Using the GRADE system for rating strength of evidence [29], 11 studies were graded as high [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,45], 3 as moderate [43,46,47,48], 9 as low [31,32,49,51,53,54,55,56,58,59], and 3 as very low [50,52,57]. No studies reported adverse effects from interventions, though only one study mentioned monitoring for them [33,34]. Recommendations were “probably do it” for the six interventions arising from studies with moderate and high strength of evidence for significant between-group effects (online Supplemental Table S2).

Using the traffic light rating system [30], there was insufficient evidence to recommend any of the interventions unreservedly (“Green: go”), as there were not multiple controlled studies supporting any intervention; nor were there reasons (e.g., adverse effects) to recommend avoiding any interventions (“Red: stop”). All interventions were rated as “Yellow: measure”, meaning that the effect is uncertain, and outcomes should be measured when interventions are used.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

This rapid review shows that HL interventions for caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental and chronic conditions can improve caregivers’ HL and the individuals’ health-related outcomes across diverse conditions, ages, and carer education levels and using diverse intervention media (Table 4).

The studies included over 2000 individuals of all ages from 12 countries with over 17 different health conditions. Only a third of studies stated that they consulted target populations when developing the intervention, so future HL interventions may be strengthened through co-design with target populations [60].

The HL interventions used seven media (e.g., online, workshop, and print) and ranged in length from a single contact to a 12-month program. The interventions with moderate-to-strong evidence of effectiveness appeared to be more intensive than the ineffective interventions. Effective interventions lasted for 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months; one was a 2-day workshop with follow-up, and two used written materials. On the other hand, ineffective interventions from studies with moderate-to-strong evidence consisted of single videos, one 90 min group session, and three phone calls over 4 months. Only one unsuccessful intervention was intensive (6-month access to website), but that study had a high (65%) attrition rate [36]. Longer, intensive HL programs may, therefore, be more successful, but attention must be paid participant retention.

As Yuen et al. [20] observed, some aspects of HL are targeted more than others; most studies assessed caregiver understanding of the health condition (knowledge) and application of that knowledge (management of the condition). Very few studies assessed caregivers’ access or appraisal of health information; although, these are also key components of HL. Appraisal may involve advanced skills; one study that targeted appraisal used a university health sciences librarian to deliver training to caregivers with college education [54]. Nevertheless, this review found that at least some HL outcomes can be achieved with caregivers from all educational levels, including primary school only [38]. Service utilization, which has had mixed results in previous studies [14,60], was not enhanced by HL interventions in the only two studies that investigated it [42,49].

The strength of evidence across studies ranged from high to very low. The evidence for each of the effective interventions came from only one study of moderate-to-high strength of evidence, and so only weak recommendations could be made; traffic light ratings were yellow for all studies. Nevertheless, there is enough moderate to high level evidence to make six “probably do it” recommendations (online Supplemental Table S2). Even interventions without this level of evidence could be used in practice (as there were no reported adverse effects) if the outcomes are monitored.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

This was a rapid review, so some steps of a systematic review were curtailed, following the evidence-informed recommendations for rapid reviews [21]. These included avoiding grey literature, limiting articles to English, and having most screening and all data extraction, risk of bias, and strength of evidence assessments carried out by a single author and verified by a second. There was no information specialist. The studies in this area are sparse and published across a range of disciplines, and so wide-ranging search terms had to be used to capture relevant papers. However, this meant that only 28 out of 3389 papers met the inclusion criteria, so there may be some subjectivity in their selection. Caregiver outcomes important for a holistic view of caregivers’ roles (e.g., advocacy skills) were not considered, nor were interventions that may have influenced caregiver HL without targeting it. Feasibility and acceptability of the interventions were not reported in this review; usability was assessed in only five studies [36,40,45,50,54], where it was found adequate or better.

4.3. Implications for Policy, Practice, and Research

HL interventions for caregivers of children and adults with neurodevelopmental and chronic conditions can improve caregiver HL and health outcomes. Intensive interventions (e.g., ≥3 months) may be required, but attention must be paid to retaining participants and delivering training in a digestible form. More attention should be given to caregivers’ access and appraisal of information. As HL intervention research is still sparse [20], there is abundant scope for research developing and assessing HL interventions, especially for caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions.

5. Conclusions

Caregivers of individuals with neurodevelopmental and chronic health conditions have long-term daily responsibilities in managing health conditions, for which they require HL skills. This review found that HL interventions for caregivers of these individuals can sometimes improve caregiver HL and individuals’ health outcomes, but not always. Effective interventions appear to be more intensive but are otherwise diverse in their target populations and types of interventions. Future research is required to develop and assess HL interventions for these and similar populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children12010009/s1, Table S1: Search Strategy; Table S2: Grading of evidence and recommendations using GRADE and the traffic light system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N., J.K. and J.D.; methodology, T.N., J.K., S.H., R.S., O.L., J.D. and A.M.B.; data curation, T.N., J.K., S.H., R.S., O.L. and A.M.B.; formal analysis, T.N. and A.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N. and A.M.B.; writing—review and editing, T.N., J.K., S.H., R.S., O.L., J.D. and A.M.B.; supervision, A.M.B.; project administration, J.D.; funding acquisition, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (GTN2015902). J.D. was supported by a Fellowship from the Stan Perron Charitable Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

Data extracted from included studies and used for analyses are provided in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mullin, A.P.; Gokhale, A.; Moreno-De-Luca, A.; Sanyal, S.; Waddington, J.L.; Faundez, V. Neurodevelopmental disorders: Mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J.; Miller, G.C.; Britt, H. What are chronic conditions that contribute to multimorbidity? Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.F.; Bayliss, D.M.; Glauert, R.; Harrison, A.; Ohan, J.L. Chronic Illness and Developmental Vulnerability at School Entry. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.D.; Berry, J.; Feudtner, C.; Stone, B.L.; Sheng, X.; Bratton, S.L.; Dean, J.M.; Srivastava, R. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horridge, K.A.; Bretnall, G.; Fraser, L.K. Hospital admissions of school-age children with an intellectual disability: A population-based survey. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2023, 65, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieve, L.A.; Gonzalez, V.; Boulet, S.L.; Visser, S.N.; Rice, C.E.; Van Naarden Braun, K.; Boyle, C.A. Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2010. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Feinberg, I.; Spratling, R. The Relationship of Parental Health Literacy to Health Outcomes of Children with Medical Complexity. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 60, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maine, A.; Brown, M.; Dickson, A.; Truesdale, M. The experience of type 2 diabetes self-management in adults with intellectual disabilities and their caregivers: A review of the literature using meta-aggregative synthesis and an appraisal of rigor. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 24, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, E.Y.; Dodson, S.; Batterham, R.W.; Knight, T.; Chirgwin, J.; Livingston, P.M. Development of a conceptual model of cancer caregiver health literacy. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.; Wood, F.; Davies, M.; Edwards, A. Distributed health literacy’: Longitudinal qualitative analysis of the roles of health literacy mediators and social networks of people living with a long-term health condition. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, D.L.; Fredman, L.; Haley, W.E. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keim-Malpass, J.; Letzkus, L.C.; Kennedy, C. Parent/caregiver health literacy among children with special health care needs: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, E.Y.N.; Knight, T.; Ricciardelli, L.A.; Burney, S. Health literacy of caregivers of adult care recipients: A systematic scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, e191–e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWalt, D.A.; Hink, A. Health literacy and child health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics 2009, 124 (Suppl. 3), S265–S274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindly, O.; Crossman, M.; Eaves, M.; Philpotts, L.; Kuhlthau, K. Health Literacy and Health Outcomes Among Children With Developmental Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 125, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, B.; Rodakowski, J.; James, A.E.; Beach, S. Caregiver health literacy predicting healthcare communication and system navigation difficulty. Fam. Syst. Health 2018, 36, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, R.; Leslie, S.J.; Polson, R.; Cusack, T.; Gorely, T. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.; Wilson, C.; Adams, J.; Kangutkar, T.; Livingston, P.M.; White, V.M.; Ockerby, C.; Hutchinson, A. Health literacy interventions for informal caregivers: Systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, H.; Dark, L.; Carnemolla, P.; Skinner, I.; Hemsley, B. A systematic review of the health literacy of adults with lifelong communication disability: Looking beyond accessing and understanding information. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 106, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Bruland, D.; Schlupp, S.; Bollweg, T.M.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; Bond, E.; Sørensen, K.; Bitzer, E.M.; et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörelius, E.; Robinson, S.; Arabiat, D.; Whitehead, L. Digital Interventions to Improve Health Literacy Among Parents of Children Aged 0 to 12 Years With a Health Condition: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e31665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darrah, J.; Hickman, R.; O’Donnell, M.; Vogtle, L.; Wiart, L. AACPDM Methodology to Develop Systematic Reviews of Treatment Interventions (Revision 1.2); American Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine: Rosemont, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018: User Guide; Report No. 1356–1294; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, D.; Best, D.; Briss, P.A.; Eccles, M.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Flottorp, S.; Guyatt, G.H.; Harbour, R.T.; Haugh, M.C.; Henry, D.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004, 328, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; McIntyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Campbell, L.; Dark, L.; Morton, N.; Stumbles, E.; Wilson, S.A.; Goldsmith, S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2013, 55, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, S.D. Effect of education on school-age children’s and parents’ asthma management. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2004, 9, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, S.D. Home visiting for intervention delivery to improve rural family asthma management. J. Community Health Nurs. 2006, 23, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kintner, E.K.; Cook, G.; Marti, C.N.; Allen, A.; Stoddard, D.; Harmon, P.; Gomes, M.; Meeder, L.; Van Egeren, L.A. Effectiveness of a school- and community-based academic asthma health education program on use of effective asthma self-care behaviors in older school-age students. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 20, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintner, E.K.; Cook, G.; Marti, C.N.; Gomes, M.; Meeder, L.; Van Egeren, L.A. Effectiveness of a school-based academic asthma health education and counseling program on fostering acceptance of asthma in older school-age students with asthma. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 20, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, N.S.; Chau, J.P.C.; Lo, S.H.S.; Choi, K.C.; Hon, K.L.E.; Lam, P.H.; Leung, T.F. Effects of a self-efficacy theory-based parental education program on eczema control and parental outcomes. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geense, W.W.; van Gaal, B.G.; Knoll, J.L.; Maas, N.M.; Kok, G.; Cornelissen, E.A.; der Sanden, M.W.N.-V. Effect and Process Evaluation of e-Powered Parents, a Web-Based Support Program for Parents of Children With a Chronic Kidney Disease: Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckel, L.; Fennell, K.M.; Reynolds, J.; Boltong, A.; Botti, M.; Osborne, R.H.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Chirgwin, J.; Williams, M.; Gaskin, C.J.; et al. Efficacy of a telephone outcall program to reduce caregiver burden among caregivers of cancer patients [PROTECT]: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noroozi, F.; Fararouei, M.; Kojuri, J.; Ghahremani, L.; Ghodrati, K. Salt Consumption and Blood Pressure in Rural Hypertensive Participants: A Community Filed Trial. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 2908811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te’o, D.T.; Wild, C.E.K.; Willing, E.J.; Wynter, L.E.; O’Sullivan, N.A.; Hofman, P.L.; Maessen, S.E.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Anderson, Y.C. The Impact of a Family-Based Assessment and Intervention Healthy Lifestyle Programme on Health Knowledge and Beliefs of Children with Obesity and Their Families. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.S.; Gupta, R.S.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Dreyer, B.; van Schaick, L.; Brown, C.R.; Encalada, K.; Sanchez, D.C.; Warren, C.M.; Tomopoulos, S. Use of a low-literacy written action plan to improve parent understanding of pediatric asthma management: A randomized controlled study. J. Asthma 2017, 54, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Wong, H.M.; McGrath, C. Social story-based oral health promotion for preschool children with special healthcare needs: A 24-month randomized controlled trial. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, M.E.; DuRivage, N.E.; Bezpalko, O.; Suh, A.; Wade, R.; Blum, N.J.; Fiks, A.G. A Pilot Randomized Trial of a Video Patient Decision Aid to Facilitate Early Intervention Referrals From Primary Care. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 56, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, M.L.; Davis, M.M.; Clark, S.J.; Stanley, R.M. Parental health literacy and asthma education delivery during a visit to a community-based pediatric emergency department: A pilot study. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2011, 27, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, H.M.; Levin, L.E.; Morel, K.D.; Garzon, M.C.; Stockwell, M.S.; Lauren, C.T. Texting atopic dermatitis patients to optimize learning and eczema area and severity index scores: A pilot randomized control trial. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutar Güven, Ş.; İşler Dalgiç, A.; Duman, Ö. Evaluation of the efficiency of the web-based epilepsy education program (WEEP) for youth with epilepsy and parents: A randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 111, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemann, J.; Szczepanski, R.; Ernst, G.; Thyen, U.; Ure, B.; Goll, M.; Menrath, I. Transition of Patients with Esophageal Atresia to Adult Care: Results of a Transition-Specific Education Program. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 27, 61–67, Erratum in Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 27, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapru, I.; Khalid-Khan, S.; Choi, E.; Alavi, N.; Patel, A.; Sutton, C.; Odejayi, G.; Calancie, O.G. Effectiveness of online versus live multi-family psychoeducation group therapy for children and adolescents with mood or anxiety disorders: A pilot study. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2016, 30, 20160069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, A.; Mohamed, A.; Corbett, C.; Herring, K.; Hildenbrand, J.; Locke, S.C.; Patierno, S.; Troy, J.; Wolf, S.; Zafar, S.Y.; et al. A single-site pilot feasibility randomized trial of a supportive care mobile application intervention for patients with advanced cancer and caregivers. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7853–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchhorn-White, J.; Robertson, E.G.; Wakefield, C.E.; Cohen, J. A Decision Aid for Nutrition Support is Acceptable in the Pediatric Hospital Setting. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 55, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, E.; Barello, S.; Corsaro, A.; Galizi, M.C.; Giuffrida, F.; Graffigna, G.; Damiani, G. An Italian pilot study of a psycho-social intervention to support family caregivers’ engagement in taking care of patients with complex care needs: The Engage-in-Caring project. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Baqués, A.; Contreras-Porta, J.; Marques-Mejías, M.; Cárdenas Rebollo, J.M.; Capel Torres, F.; Ariño Pla, M.N.; Zorrozua Santisteban, A.; Chivato, T. Evaluation of an Online Educational Program for Parents and Caregivers of Children With Food Allergies. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 28, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, B.; Murray, K.; Hershey, D.; Nuttall, A.K.; Cotten, S.; Park, T.; Dunneback, J.K.; Wood, M.A. The Development and Testing of MyT1DHope—A Website for Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2018, 67 (Suppl. 1), 2237-PUB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Heimsoth, A.; Johnson, M.L.; McCulley, A.; Basinger, M.; Maki, K.; Davison, D. Good Googling: A Consumer Health Literacy Program Empowering Parents to Find Quality Health Information Online. J. Consum. Health Internet 2017, 21, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Porta, J.; Ruiz-Baqués, A.; Gabarron Hortal, E.; Capel Torres, F.; Ariño Pla, M.N.; Zorrozua Santisteban, A.; Sáinz de la Maza, E. Evaluation of an educational programme with workshops for families of children with food allergies. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2016, 44, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.S.; Haroon, M.; Melvin, G. Evaluation of an educational website for parents of children with ADHD. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 84, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossebaard, H.C.; van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.; Sorbi, M.J.; Seydel, E.R. A study of a Dutch online decision aid for parents of children with ADHD. J. Telemed. Telecare 2010, 16, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBovidge, J.S.; Timmons, K.; Rich, C.; Rosenstock, A.; Fowler, K.; Strauch, H.; Kalish, L.A.; Schneider, L.C. Evaluation of a group intervention for children with food allergy and their parents. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008, 101, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikian, A.; Boutelle, K.; Peterson, C.B.; Dalton, J.; Day, J.W.; Crow, S.J. Targeting parents for the treatment of pediatric obesity in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A case series. Eat. Weight Disord. 2010, 15, e161–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, A.; Batterham, R.W.; Dodson, S.; Astbury, B.; Elsworth, G.R.; McPhee, C.; Jacobson, J.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Systematic development and implementation of interventions to OPtimise Health Literacy and Access (Ophelia). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidman, E.A.; Scott, K.M.; Hahn, D.; Bennett, P.; Caldwell, P.H. Impact of parental health literacy on the health outcomes of children with chronic disease globally: A systematic review. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2023, 59, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).