Abstract

Objective: To better understand the strategies family caregivers of children with medical complexity (CMC) utilize to deal with the stress and challenges associated with caregiving. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional qualitative study among family caregivers of CMC receiving medical care at a children’s hospital in Western Pennsylvania. Participants completed in-depth, semi-structured interviews focused on how CMC family caregivers approach and manage caregiving-related challenges and stress. Using constant comparative methodology, we inductively analyzed deidentified transcripts for emergent themes. Results: We interviewed 19 participants (89.4% female) with a mean age of 43 years (range 32–54 years). The mean age of the participants’ children was 10.8 years (range 1–20 years). Twelve participants’ children identified as white and four identified as Black. Three central themes regarding CMC caregivers’ stress-coping strategies emerged: (1) maintaining a positive mindset, (2) developing and relying on interpersonal support networks, and (3) making time for self-preservation. All three themes were universally reported (n = 19/19) by our participants. The most common subthemes for each theme, respectively, focused on staying hopeful and celebrating moments of joy; cultivating supportive relationships with family, friends, and fellow CMC family caregivers; and finding pleasure in “little things” (e.g., everyday activities and hobbies). Conclusion: Family caregivers of CMC utilize a multi-faceted approach to cope with the stress and challenges routinely encountered in caring for CMC. This study’s findings could be used to inform future clinical efforts and research directions aiming to improve clinicians’ ability to support CMC caregivers’ well-being.

1. Introduction

Children with medical complexity (CMC) live with chronic health conditions, major functional limitations (e.g., difficulty with feeding and cognition), and health service needs such as home-nursing. CMC also often require medical technologies (e.g., wheelchairs, mechanical ventilation) to sustain life and daily function [1]. The CMC population has roughly doubled over the past decade (1.6% of the US pediatric population [1.2 million US children]) and account for approximately one-third of all pediatric health care expenditures and one-half of inpatient pediatric-related costs [2]. Most CMC live at home, with family caregivers responsible for arranging and carrying out intricate care plans, which include demanding medical tasks, and coordinating communication between providers. CMC caregivers also encounter challenges such as fragmented health care systems, financial adversity, inadequate home-based services, and complicated medical decisions [3,4]. These challenges put CMC caregivers at high-risk for reduced emotional well-being [5]. CMC caregivers have reported reduced overall mental health and health-related quality of life, high levels of emotional distress, and poor sleep-related health [5].

Reduced emotional well-being among CMC family caregivers can hinder their ability to care for and advocate for their children [6,7]. In other parental caregiver populations, emotional distress, sleep loss, family conflict, and economic insecurity have been inversely linked to child health [6]. For example, Goodwin et al. demonstrated that an increased volume of stressors (i.e., family conflict) was associated with more hospitalizations among children with asthma [8]. This has serious public health implications, as CMC caregivers play an essential role in the operational capacities of pediatric health systems [9,10].

In response, experts and national advocacy organizations have specifically called for targeted efforts aiming to improve CMC family caregiver emotional well-being [11,12,13]. Currently, however, few psychosocial interventions have been developed for or evaluated among this caregiver population. A 2019 scoping review examining interventions aiming to improve the well-being of parents of children with special health care needs (a broader pediatric population in which CMC are often categorized) only identified one study that likely included CMC caregivers—a non-experimental pilot trial of dyadic peer support intervention [14,15]. Similarly, Edelstein et al.’s scoping review of approaches targeting CMC caregiver stress noted the overall lack of experimental data and that existing interventions predominately focused on enhanced models of care coordination and service delivery [16]. Consequently, clinicians lack knowledge of and training in evidence-based strategies to better support CMC family caregivers.

One promising approach would be to enhance CMC caregivers’ ability to cope with challenges perceived as stressful. In the broader pediatric caregiving literature, psychosocial interventions targeting family caregivers’ stress coping ability have improved caregiver emotional well-being [17,18]. For example, studies examining the effects of psychosocial interventions on caregivers of children with cancer have demonstrated that enhancing caregivers’ problem-solving skills can significantly decrease caregivers’ negative affectivity and post-traumatic stress symptoms when compared to usual psychosocial care [19,20,21].

However, directly applying existing psychosocial interventions to CMC family caregivers is not appropriate, as their unique experience is characterized by life-long challenges and frequent and demanding interactions with pediatric health systems. To successfully identify and tailor psychosocial interventions for CMC caregivers, a better understanding of the coping strategies (i.e., thoughts, behaviors, and resources) they use to deal with challenges and maintain their emotional well-being is needed. Therefore, to inform future selection and adaptation of existing psychosocial interventions, and to identify supportive practices that CMC clinicians can adopt now, we conducted qualitative interviews exploring CMC caregivers’ perspectives on managing stressful challenges related to their caregiving experiences.

2. Methods

This inductive phenomenological qualitative study was part of a larger study examining the experiences of family caregivers of CMC in coping with caregiving-related stress. We utilized the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines for conducting rigorous qualitative research [22]. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh approved all aspects of this study.

2.1. Participants

The participants (n = 19, Table 1) were family caregivers of CMC receiving medical care at a single quaternary academic pediatric hospital located in Western Pennsylvania. We used our institution’s Complex Care Center’s patient eligibility criteria to define medical complexity: chronic health conditions in 3 or more organ systems requiring subspecialist care and/or utilization of medical technology. Caregivers were eligible if they were able to complete interviews in English, had medical decision-making authority for their child, and were of ages ≥18 years. We excluded family caregivers of CMC who (1) resided in long-term care facilities, as these caregivers were not responsible for providing the majority of their child’s care, and (2) caregivers of children <1 year of age to ensure that participants had significant experience in caring for their child at home. To maximize the breadth of experiences, we enrolled one caregiver per family unit.

Table 1.

Demographics information.

Eligible caregivers were identified through bi-weekly reviews of our hospital’s (1) Complex Care Center’s outpatient schedule, and (2) Palliative and Supportive Care team’s inpatient consult census. To minimize power differentials, we excluded caregivers whose child was receiving direct clinical care from the interviewer (JY) at the time of study enrollment. Prior to approach, caregiver eligibility was confirmed with the relevant team’s providers and permission to approach in-person and provide study details was obtained. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating and were compensated USD 35. Caregivers were purposively sampled to attain diversity in socioeconomic status, children’s medical conditions, and time since initial diagnosis.

2.2. Instruments

The interview guide was developed by a group with expertise in palliative care (JY, YS), pediatric oncology (AR), pediatric rehabilitation medicine (AH), and clinical psychology (RN). The interview guide was refined based on feedback from three pilot interviews with representative CMC family caregivers to improve question clarity and acceptability. We used open-ended, non-leading questions to identify caregivers’ personal experiences and contributors to their stress experience, strategies for and struggles in coping with stressors, and beliefs about the impact of caregiving on their emotional well-being. Private, one-on-one, semi-structured interviews were conducted either in person or via telephone, based on the participant’s preference, by a single investigator (JY) with training in pediatrics, palliative care, and clinical research. Participant information was deidentified and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim with all identifying information removed. The data were only handled by members of the team directly associated with their coding. Interviews were conducted until the research team agreed that thematic saturation (when no new themes emerged from subsequent interviews) was achieved. Interview transcripts were uploaded to ATLAS.ti Web, a cloud-based qualitative analytics platform that facilitated data storage, organization, coding, annotation, and content analysis from our body of unstructured interview data.

2.3. Procedures and Data Analysis

Two study team members (ML and JY) developed a preliminary codebook iteratively and inductively through line-by-line coding and constant comparative methodology on an initial subset of transcripts. The codebook was finalized through multiple rounds of concept and code review and revision with the senior multidisciplinary team (YS, AR, AH, and RN). Four research team members (ML, JY, LM, and SW) then independently applied the final codebook to all transcripts using recursive cycles of coding and face-to-face meetings (during which disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus). To enhance the credibility and clarity of our thematic analysis, we presented our findings to members of a community advisory board of CMC family caregivers. This advisory board provided feedback on which themes resonated and those which required refinement. Lastly, the coded interview data were organized into overarching themes by the entire study team through group discussion, iterative thematic analysis, and feedback from members of a community advisory board of CMC family caregivers. The proportions of participants reporting each theme and subthemes were determined to describe prevalence.

3. Results

We interviewed 19 CMC family caregivers between March 2022 and April 2023 (Table 1). The majority of participants identified as female (n = 17) and reported living with another adult (n = 13) and receiving home nursing services (n = 11) for an average of 42.5 h per week (SD 17.6 h, range 16–80 h). The average age of the caregivers was 43 years old (SD 6.7, range 32–54 years). The average age of the participants’ children was 10.8 years old (SD 6.3, range 1–20 years). Ten of the children were female (52.6%). Twelve (63.2%) identified as white, four (21.1%) identified as Black, and three (15.8%) identified as another race (e.g., Asian, mixed race). Nearly all interviews were conducted via telephone (18 of 19). The average length of the interviews was 49 min (range 37–66 min).

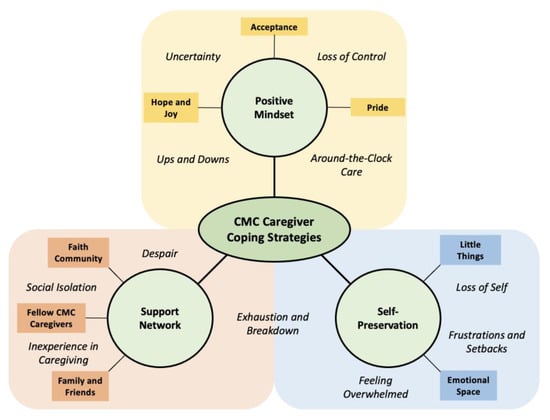

Three overarching themes emerged in participants’ discussions about how they dealt with caregiving-related challenges and maintained their emotional well-being: (1) maintaining a positive mindset, (2) developing and relying on interpersonal support networks, and (3) making time for self-preservation. For each theme, we discuss the subthemes that describe the thoughts, behaviors, and resources which enable CMC caregivers to employ these approaches. Representative quotes for the themes and subthemes are presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. Our conceptual model (Figure 1) illustrates the assortment of coping strategies participants reported using to manage caregiving challenges.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotes for Theme 1 subthemes.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes for Theme 2 subthemes.

Table 4.

Illustrative quotes for Theme 3 subthemes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the coping strategies employed by CMC family caregivers. This figure presents the coping strategies CMC family caregivers use to address the stress and challenges (italicized) they commonly experience.

3.1. Theme 1: Maintain a Positive Mindset

All participants (n = 19/19) described employing multiple ways of deliberate thinking and self-talk strategies to stay positive throughout caregiving’s rollercoaster experience (Table 2). Caregivers repeatedly explained that a positive mindset mitigated the intensity of negative emotions, which was critical for maintaining their long-term ability to endure the ups-and-downs of caregiving and ensuring their child’s health. The following subthemes describe concepts and strategies that participants relied on during times of acute stress and daily routines.

Hope and Joy (n = 18/19): Nearly all participants emphasized the importance of being hopeful about the future and seeking out joy in their lives. Discussions about hope typically centered on their child’s long-term health and/or their family’s overall circumstances. One mother reflected on her goals, “I’m hopeful that with [our son] being more mobile and interactive, and maybe being able to communicate, that the kids can play together. It will be more like a normal family”. Importantly, caregivers added that hope was dynamic, fluctuating in what they were hopeful for and how difficult it could be to hold on to. Multiple participants discussed experiences in which their hope was solely focused on getting through the challenge in front of them (e.g., admission to intensive care) and relying on their child’s history as a source of inspiration.

Intertwined with discussions about hope were caregivers’ concerted efforts to recognize and celebrate moments of joy. Caregivers explained that “small wins” in their child’s health or development were quite meaningful and helped them maintain a positive mindset. As one mother remarked, “I’d say probably the best thing is to admire and appreciate the strength of kids, how determined they can be… We’re excited over stuff that normal parents [couldn’t] care less to even recognize… We’re so lucky to get to see those moments”. Another participant described the impact of her daughter’s new wheelchair, “She will decide she doesn’t want to go certain places… she has more independence to say, ‘Yeah, look. I’m not going there. Just her being herself… she makes my heart smile”.

Acceptance (n = 14/19): Comments regarding hope for the future were often balanced by discussions about the importance of and their path to accepting the implications of their child’s health conditions. Acceptance enhanced caregivers’ ability to reconcile with uncertainty and regulate intense emotions. Central to acceptance was the understanding that, at times, aspects of their child’s care and well-being were out of their control and intentionally not dwelling on issues they could not change. One father summarized:

- It is what it is. Nothing can be done or changed, so I kind of accept it… I just learned to not really stress over stuff that you can’t change, because stressing over something you can’t change doesn’t do anything. It just wears you out. You’ve got to accept it and keep going on.

Pride (n = 12/19): Many participants discussed the sense of pride that stemmed from how their care enabled their children’s flourishing. One mother stated, “The decisions I make always revolve around her, and I always feel like they have her best interest in mind… I feel like I’m good and I’m decent”. Caregivers also experienced deep fulfillment from ensuring their child felt loved. Participants also used this concept as a protective mechanism in the face of acute stress (e.g., child illness) and found solace knowing they were caring for their child as best as possible. One participant summarized the self-talk she uses to deal with setbacks, “Give yourself grace because you are doing the best that you can and giving her absolutely everything… [you don’t need] to feel that tremendous guilt”.

3.2. Theme 2: Developing and Relying on an Interpersonal Support Network

Every participant (n = 19/19) discussed the importance of cultivating a network of support beyond their child’s health care team (Table 3). Caregivers derived emotional support, encouragement, caregiving assistance, and practical advice from these relationships. Participants also discussed how their support network provided a safe place to vent about frustrations and other stressors.

Family and Friends (n = 17/19): Family and friends offered both practical and emotional support, which helped alleviate caregiving-related stress. This included respite and/or an “extra set of hands”, helping problem-solve in the moment (e.g., malfunctioning feeding pump), companionship, and moral support during times of acute stress. Emphasizing the value of emotional support, one participant stated, “I couldn’t imagine going through this alone… if I’m feeling down, he’ll lift me up. It’s almost like we take turns. It’s like a blessing that both of us are in that dark space together at the same time”.

In The Trenches (n = 17/19): Participants highlighted the importance of developing relationships with people who could relate to the challenges of CMC caregiving. Fellow caregivers were a trusted source for practical advice (e.g., wheelchair adjustments) and discussing concerns about their child’s medical care plan. For example, one mother described her relationship with an aunt whose child also lives with neurologic conditions, “She has a daughter that [has] autism and epilepsy, and so I can talk to [her] about seizures, [seizure] meds, developmental delays, and the worries that go along with all those things”. Participants also valued the camaraderie they felt with other CMC caregivers, which helped alleviate feelings of social isolation stemming from the difficulty in relating to parents of children without complex needs who “don’t get it” or “don’t understand”.

Faith Community (n = 6/19): Some participants discussed the role of faith and religion in their lives. Faith communities offered an additional layer of psychosocial support: “I have a group of women that we meet once a month through the church… [Child] is on the prayer list for our group, and people will frequently ask me how she’s doing, and how I’m holding up”. Participants also explained how their faith helped get them through acutely stressful experiences. One caregiver remarked, “You just feel the Bible lift you. It’s just incredible because [God] shows you. He’s there. He’s going to be there. And it helps a lot… You know that you’re not alone”.

3.3. Theme 3: Making Time for Self-Preservation

Lastly, all participants (n = 19/19) described purposefully carving out time for themselves as an essential form of “self-preservation”. Dedicated time for self-care was essential to preventing “breakdown” and maintaining one’s long-term ability to perform in their caregiving role. Participants discussed several strategies allowing them to shift attention inwards.

Little Things (n = 14/19): Multiple caregivers discussed intentionally taking time to find pleasure in everyday activities unrelated to their child’s medical care. One parent commented, “You can’t forget the little things that you still enjoy, like you can still put on your favorite band and listen to [them] with your kid”. Participants also made time for interests that contributed to their self-identity, such as hobbies (e.g., one father raced motocross) or community organization participation. Caregivers acknowledged how difficult finding the time for these endeavors could be due to time constraints, planning requirements, and a lack of child-care options. However, participants emphasized the self-preserving aspects of this strategy. One mother explained, “I am starting to find me again. Because for a long, long time, there wasn’t any me… I don’t care if that means just me for an hour here and there… but you definitely need to make time for yourself”.

Emotional Space (n = 13/19): Most participants also discussed the importance of finding time to feel and process their emotions. Making an effort to relish positive feelings was described as rejuvenating and healing. For example, one mother described her routine when life becomes overwhelming, “[I] just try to take a moment to sit down and hold [child] in the chair and just cuddle him and take a moment to really appreciate how my boys are going. … Those kinds of things are food to my soul”. Central to creating the time and space necessary for emotional processing was developing the ability to be present in any given moment, slowing down, and stopping thinking about the challenges or tasks at hand.

In contrast, caregivers also explained that indulging negative emotions (e.g., anger), albeit temporarily, could be helpful in moving past frustrations and setbacks. Describing her experiences with a palliative care social worker, one participant stated:

- Allowing a person to be where they are at is important, like helping them to understand why they’re feeling that way. [Social worker stating] ‘You’re angry, and this is why you’ve got the right to be’’. … I think it’s important for me to be okay with what I’m feeling at the moment, just making it safe.

4. Discussion

In this qualitative study, family caregivers of CMC described the strategies they used to cope with stress related to their caregiving experience. While participants reported a variety of approaches for dealing with stress and challenges, three overarching themes emerged: (1) maintaining a positive mindset, (2) developing and relying on interpersonal support networks, and (3) making time for self-preservation. This study responds to national calls for a better awareness and understanding of CMC family caregivers’ experiences [13,23]. Our findings can inform the development and implementation of services and structural reforms aiming to better support CMC family caregiver well-being [9,10,24]. More specifically, our results highlight potential future directions for psychosocial, clinical, and communication interventions targeting CMC family caregivers’ ability to cope with stress.

4.1. Maintaining a Positive Mindset

Our first theme, “maintaining positivity”, aligns with prior findings from the caregiver coping literature, which has shown that a positive mindset is associated with enhanced mental and physical health, quality of life, and care quality, as well as a decreased perceived burden [25,26,27]. More specifically, our subthemes of being hopeful and finding joy, accepting clinical realities, and developing a sense of pride are consistent with research describing hope, prognostic awareness, and “good parent” beliefs among parents of children with serious illnesses [28,29,30,31]. Our study adds to this body of work by demonstrating these subthemes’ interconnectedness and how each represents potential strategies for CMC family caregivers to cultivate a positive mindset, which has important clinical and research implications. For example, CMC clinicians could be more intentional in promoting and maintaining mindset positivity by routinely exploring family caregivers’ hopes and/or good parent beliefs, affirming their aspirations, and praising caregivers’ efforts [20,29,32]. Furthermore, clinician leaders could partner with CMC families to examine how their local health system’s structure and team’s services could be better tailored to nurture caregivers’ hopes and good parent ideals [28]. As only a minority of family caregivers report engagement in similar discussions, future research and educational directions include the development and testing of additional communication frameworks that specifically target CMC family caregiver hope, acceptance, and good parent beliefs. Perhaps more importantly, how such communication strategies can be better incorporated into clinician training and translated into clinical practice must be examined [31,33].

4.2. Developing Interpersonal Support Networks

Our participants’ discussions about the importance of robust interpersonal networks and self-preservation are consistent with the existing caregiving literature as well. Social support from a variety of sources (e.g., extended family, clinicians, faith communities) has been repeatedly linked to reduced emotional distress, an enhanced sense of overall well-being and physical health, and a lower perceived burden among multiple caregiver populations [34,35]. Likewise, caregiver engagement in self-care, which refers to practices that promote and maintain one’s health and well-being, are associated with reduced emotional distress and perceived stress, increased satisfaction with the caregiving role, and improved outcomes for care recipients among caregivers of adults with serious illnesses [36,37].

Our findings highlight aspects of these coping strategies which are especially pertinent to family caregivers of CMC. First, almost all participants described how other CMC caregivers served as key pillars in their interpersonal support networks, even if most communication occurred virtually. Fellow caregivers were a source of informational support, such as for practical advice for troubleshooting medical technology or which subspecialists could help with specific issues. They also provided critical forms of emotional support, with caregivers reporting receiving moral support and encouragement during acutely stressful times in our study. Participants also reported that the camaraderie and friendship they felt with fellow CMC caregivers helped mitigate feelings of loneliness and perceived stigma from others. Therefore, CMC clinicians should be knowledgeable about local and national caregiver organizations (e.g., Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s Family-to-Family Health Information Centers) and incorporate this information as part of a child’s comprehensive care plan. This also suggests that the further development and dissemination of programs connecting CMC family caregivers, such as virtual support groups or peer navigator programs, represent high-yield opportunities for investigators and leaders within the complex care field [38,39].

4.3. Making Time for Self-Preservation

In discussing self-preservation, participants emphasized that self-care practices must fit within the time constraints, unpredictable schedules, and demanding responsibilities characterizing most CMC caregivers’ experiences. Therefore, clinicians’ attempts to promote self-care should focus on strategies in which caregivers can be self-taught and are of short duration. Our participants’ discussion of enjoying “little things” and/or creating “emotional space” suggests that psychosocial interventions such as mindfulness meditationand/or meaning-making activities might be particularly suitable for CMC caregivers [40,41]. We also highlight that the external factors limiting our caregivers’ ability to engage in self-care provide additional evidence that structural and policy reforms that bolster home health supports and/or formal respite service opportunities are critically needed [42].

A summary of recommendations and resources for CMC clinicians to enhance their support of CMC family caregiver coping is presented in Table 5 [23,28,29,43].

Table 5.

Clinician recommendations and resources to support CMC family caregiver coping.

5. Limitations

This study was completed at a single institution which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Relatedly, self-selection in choosing to participate may influence the data given the smaller sample size of participants. Although we recruited a racially diverse sample, our participants primarily identified as mothers, which may limit the understanding of the caregiver’s experience from the paternal perspective. Additionally, caregivers who were non-English-speaking were excluded, so the specific coping mechanisms of this population may not be inferred through our study. Lastly, as our study consisted of a one-time interview with caregivers with an average age of 43 years, the feasibility and acceptability of caregivers earlier in their journey utilizing these coping strategies might be low.

6. Conclusions

In summary, family caregivers of CMC utilize a multi-faceted set of coping strategies to deal with the stress and challenges inherent to CMC caregiving. Broadly, these strategies focused on maintaining a positive mindset, developing a network of social support, and practicing self-care. We believe our findings can guide ongoing clinical, research, and system-level efforts aiming to enhance our field’s support of CMC family caregivers.

Author Contributions

M.N.L. assisted with study design, data collection, and analysis and interpretation, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript. A.S.P., J.F.B., S.W. and L.M. assisted with data analysis and interpretation and revising the manuscript. R.B.N., A.H., A.R., J.G.W. and Y.S. assisted with study design, data interpretation, and revising the manuscript. J.A.Y. conceptualized and designed the study, supervised data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

All aspects of this study were supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center’s Kornfeld Scholars Program, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001856), as well as by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine, and the National Institutes of Health Office of Disease Prevention under award number U24HD107562. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study. Schenker was supported by K24AG070285.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board University of Pittsburgh (protocol code STUDY21060036 approved on 15 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dewan, T.; Cohen, E. Children with medical complexity in Canada. Paediatr. Child Health 2013, 18, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.A.; McKernan, G.; Hagerman, T.; Schenker, Y.; Houtrow, A. Most Children with Medical Complexity Do Not Receive Care in Well-Functioning Health Care Systems. Hosp. Pediatr. 2021, 11, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justin, A.Y.; Bayer, N.D.; Beach, S.R.; Kuo, D.Z.; Houtrow, A.J. A National Profile of Families and Caregivers of Children with Disabilities and/or Medical Complexity. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 22, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.; Kuo, D.Z.; Agrawal, R.; Berry, J.G.; Bhagat, S.K.M.; Simon, T.D.; Srivastava, R. Children with Medical Complexity: An Emerging Population for Clinical and Research Initiatives. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A.; Esser, K.; Wright, E.; Netten, K.; Edwards, A.; Rose, J.; Vigod, S.; Cohen, E.; Orkin, J. Caring for the Caregiver (C4C): An Integrated Stepped Care Model for Caregivers of Children with Medical Complexity. Acad. Pediatr. 2023, 23, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, G.; Kuo, D.Z. Psychosocial Factors in Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs and Their Families. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johaningsmeir, S.A.; Colby, H.; Krauthoefer, M.; Simpson, P.; Conceição, S.C.; Gordon, J.B. Impact of caring for children with medical complexity and high resource use on family quality of life. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 8, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, R.D.; Bandiera, F.C.; Steinberg, D.; Ortega, A.N.; Feldman, J.M. Asthma and mental health among youth: Etiology, current knowledge and future directions. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2012, 6, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allshouse, C.; Comeau, M.; Rodgers, R.; Wells, N. Families of Children with Medical Complexity: A View from the Front Lines. Pediatrics 2018, 141, S195–S201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, D.M.; Lihn, S.L.; Boat, T.F.; Lannon, C. A Roadmap to Emotional Health for Children and Families with Chronic Pediatric Conditions. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20191324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, N.; Guttmann, A.; Chiu, A.; Gardecki, M.; Orkin, J.; Hamid, J.S.; Major, N.; Lim, A.; Cohen, E. Family-provider consensus outcomes for children with medical complexity. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnert, E.S.; Coller, R.J.; Nelson, B.B.; Thompson, L.R.; Klitzner, T.S.; Szilagyi, M.; Breck, A.M.; Chung, P.J. A Healthy Life for a Child with Medical Complexity: 10 Domains for Conceptualizing Health. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Administration for Community Living; RAISE Act State Policy Roadmap for Family Caregivers: Direct Care Workforce; National Academy for State Health Policy: Portland, ME, USA. 2022. Available online: https://eadn-wc03-8290287.nxedge.io/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/NASHP_Report_3bV2-1.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Bradshaw, S.; Bem, D.; Shaw, K.; Taylor, B.; Chiswell, C.; Salama, M.; Bassett, E.; Kaur, G.; Cummins, C. Improving health, wellbeing and parenting skills in parents of children with special health care needs and medical complexity—A scoping review. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Otley, A.; Smith, C.; Avolio, J.; Munk, M.; Griffiths, A.M. Challenges and strategies of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A qualitative examination. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, H.; Schippke, J.; Sheffe, S.; Kingsnorth, S. Children with medical complexity: A scoping review of interventions to support caregiver stress. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R. Handbook on Dementia Caregiving: Evidence-Based Interventions in Family Caregiving; Springer Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 13, 330p, ISBN 9780826113122. [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston, C.; Fisher, E.; Law, E.; Bartlett, J.; Palermo, T.M. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, Cd009660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahler, O.J.Z.; Fairclough, D.L.; Phipps, S.; Mulhern, R.K.; Dolgin, M.J.; Noll, R.B.; Katz, E.R.; Varni, J.W.; Copeland, D.R.; Butler, R.W. Using Problem-Solving Skills Training to Reduce Negative Affectivity in Mothers of Children with Newly Diagnosed Cancer: Report of a Multisite Randomized Trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahler, O.J.Z.; Dolgin, M.J.; Phipps, S.; Fairclough, D.L.; Askins, M.A.; Katz, E.R.; Noll, R.B.; Butler, R.W. Specificity of Problem-Solving Skills Training in Mothers of Children Newly Diagnosed with Cancer: Results of a Multisite Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, S.; Fairclough, D.L.; Noll, R.B.; Devine, K.A.; Dolgin, M.J.; Schepers, S.A.; Askins, M.A.; Schneider, N.M.; Ingman, K.; Voll, M.; et al. In-person vs. web-based administration of a problem-solving skills intervention for parents of children with cancer: Report of a randomized noninferiority trial. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 24, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.W.; McLellan, S.E.; Scott, J.A.; Mann, M.Y. Introducing the Blueprint for Change: A National Framework for a System of Services for Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021056150B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankuda, C.K.; Maust, D.T.; Kabeto, M.U.; MA, R.J.M.; Langa, K.M.; Levine, D.A. Association Between Spousal Caregiver Well-Being and Care Recipient Healthcare Expenditures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2220–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, C.A.; Summers, A.; Grote, V.; Jackson, K.; Dowling, G.; Snowberg, K.; Cotten, P.; Cheung, E.; Yang, D.; Addington, E.L.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of a positive emotion regulation intervention to reduce stress in family caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: Protocol and design for the LEAF 2.0 study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, J.T.; Cheung, E.O.; Snowberg, K.E.; Verstaen, A.; Merrilees, J.; Salsman, J.M.; Dowling, G.A. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacio, G.C.; Krikorian, A.; Gómez-Romero, M.J.; Limonero, J.T. Resilience in Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020, 37, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, E.C.; Kiefer, A.; Blazin, L.; Spraker-Perlman, H.; Clark, L.; Baker, J.N. Bereaved Parents, Hope, and Realism. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20192771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; October, T.; Feudtner, C.; Hinds, P.S. “Good-Parent Beliefs”: Research, Concept, and Clinical Practice. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20194018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feudtner, C.; Walter, J.K.; Faerber, J.A.; Hill, D.L.; Carroll, K.W.; Mollen, C.J.; Miller, V.A.; Morrison, W.E.; Munson, D.; Kang, T.I.; et al. Good-Parent Beliefs of Parents of Seriously Ill Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P.S.; Oakes, L.L.; Hicks, J.; Powell, B.; Srivastava, D.K.; Spunt, S.L.; Harper, J.; Baker, J.N.; West, N.K.; Furman, W.L. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5979–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogetz, J.F.; Yu, J.; Oslin, E.; Barton, K.S.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Watson, R.S.; Rosenberg, A.R. Navigating Stress in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Among Parents of Children with Severe Neurological Impairment. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2023, 66, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.L.; Weaver, M.S.; Lord, B.; Wiener, L.; Hinds, P.S. Care Provider Behaviors That Shape Parent Identity as a “Good Parent” to Their Seriously Ill Child. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2021, 2, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Frías-Osuna, A.; Palomino-Moral, P.A.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J. Social support and subjective burden in caregivers of adults and older adults: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Sánchez, B.; Orgeta, V.; López-Martínez, C.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Association between Social Support and Depressive Symptoms in Informal Caregivers of Adult and Older Dependents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Xu, S. Randomized controlled trials on promoting self-care behaviors among informal caregivers of older patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Roij, J.; Brom, L.; Sommeijer, D.; van de Poll-Franse, L.; Raijmakers, N.; eQuiPe Study Group. Self-care, resilience, and caregiver burden in relatives of patients with advanced cancer: Results from the eQuiPe study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7975–7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family-to-Family (F2F) Health Information Centers. 2024. Available online: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/programs/f2f-health-information-centers (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Coleman, C.L.; Morrison, M.; Perkins, S.K.; Brosco, J.P.; Schor, E.L. Quality of Life and Well-Being for Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs and their Families: A Vision for the Future. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021056150G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabo, K.; Chin, E. Self-care needs and practices for the older adult caregiver: An integrative review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogetz, J.F.; Oslin, E.; O’donnell, M.; Barton, K.S.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Watson, R.S.; Rosenberg, A.R. Meaning-Making Among Parents of Children with Severe Neurologic Impairment in the PICU. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023064361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, R.L. Caregiver Respite: An Essential Component of Home- and Community-Based Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogetz, J.F.; Lemmon, M.E. Affirming Perspectives About Quality-of-Life with Caregivers of Children with Severe Neurological Impairment. Pediatr. Neurol. 2023, 144, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).